Abstract

Background

SARS-CoV-2 is a novel viral illness originating out of Wuhan China in late 2019. This global pandemic has infected nearly 3 million people and accounted for 200 000 deaths worldwide, with those numbers still climbing.

Case summary

We present a 54-year-old patient who developed respiratory failure requiring endotracheal intubation from her infection with SARS-CoV-2. This patient was subsequently found to have a right ventricular thrombus and bilateral pulmonary emboli, likely contributing to her respiratory status. On the 14th day of hospitalization, the patient was successfully extubated, and 5 days later was discharged to the rehabilitation unit.

Discussion

SARS-CoV-2 presents primarily with pulmonary symptoms; however, many patients, particularly those who are severely ill, exhibit adverse events related to hypercoagulability. The exact mechanism explaining this hypercoagulable state has yet to be elucidated, but these thrombotic events have been linked to the increased inflammation caused by SARS-CoV-2. This novel viral illness is still largely misunderstood, but the hypercoagulable state, seen in severely ill patients, appears to play a major role in disease progression and prognosis.

Keywords: COVID-19, Pulmonary embolism, Right ventricular thrombus, Case report

Learning points

To understand the clinical features of the hypercoagulable state seen in SARS-CoV-2.

To illustrate potential treatment strategies for patients who present with SARS-CoV-2.

Introduction

SARS-CoV-2, an enveloped RNA virus, originated out of Wuhan, Hubei Provence, China in December 2019, and escalated to a global pandemic in early 2020.1 Severe cases of this viral illness have been known to cause ARDS, respiratory failure, and other organ dysfunction. The pathophysiology is largely unknown and the treatment strategy is constantly evolving to deal with this novel illness. Many patients have been found to be in a hypercoagulable state and thrombosis has been theorized to contribute to severity of the disease, and to the subsequent organ damage.2 We present a severe case of SARS-CoV-2 presenting with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), respiratory failure with bilateral pulmonary emboli, and a right ventricular thrombus.

Timeline

| Description | |

|---|---|

| Day 0 | Patient recalls fevers, cough, and progressive shortness of breath. |

| Admission Day 0 | Patient admission to the Emergency Department where she is intubated. CT angiogram shows bilateral pulmonary emboli, and probable diagnosis of respiratory failure secondary to SARS-CoV-2 is made. Patient admitted to the ICU where she continued to be hypoxic on 10 L non-rebreather despite increased oxygen supplementation. Patient subsequently intubated. |

| Admission Day 1 | Transthoracic echocardiogram reveals a right ventricular thrombus. |

| Admission Day 4 | Patient confirmed to be positive for SARS-CoV-2 by PCR. |

| Admission Days 2–14 | Patient remains intubated in the ICU using volume control, without the ARDS protocol. |

| Admission Day 14 | Patient extubated and transferred to the step-down unit on 6 L nasal cannula |

| Admission Day 17 | Patient transferred to the general medical floors on 5 L nasal cannula. |

| Admission Day 19 | Patient discharged to the inpatient rehabilitation unit on room air. |

Case presentation

A 54-year-old African-American woman with a past medical history of a deep vein thrombosis and remote provoked pulmonary embolism presented to the Emergency Department with complaints of fevers, progressive shortness of breath, and cough of >2 weeks duration. She had a history of provoked pulmonary embolism after a long aeroplane ride in 2012, and was anticoagulated with warfarin for 3 months afterwards. On initial presentation to the Emergency Department, the patient’s oxygen saturation was 99% on room air, blood pressure was 100/70 mmHg, with a heart rate of 75 b.p.m. The patient’s respiratory rate was measured at 30 breaths/min. Lab work was notable for an elevated D-dimer at 2.86 mg/L (0.00–0.056 mg/L), ferritin at 683.2 ng/mL (10.0–291.0 ng/mL), lactate dehydrogenase at 929 U/L (81–234 U/L), aspartate aminotransferase (AST) at 190 U/L (15–37 U/L), and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) at 131 U/L (14–59 U/L) with a decreased platelet count of 98 (150–450), white blood cell count of 3.9 (4.8–10.8), and absolute lymphocyte count of 0.59 (1.15–4.75). The patient’s initial labs were also notable for an elevated probrain natriuretic petide (BNP) of 2016 pg/mL (0–125 pg/mL) and an initial troponin elevation of 0.100 ng/mL (0.000–0.056 ng/mL), which trended down. Electrocardiogram (ECG) showed evidence of right ventricular strain, and bedside transthoracic echocardiogram (echo) assessment revealed a dilated right ventricle with McConnell’s sign (Figure 1). The patient was subsequently sent for a computed tomography angiography of the chest, revealing a large pulmonary embolism in the right main pulmonary artery extending into the interlobar artery, right middle lobar, segmental, and subsegmental arteries. Additional smaller pulmonary emboli were noted in the left upper and lower lobe segmental and subsegmental pulmonary arteries (Figure 2). The computed tomography of the chest also demonstrated evidence of right heart strain, as well as multiple scattered ground-glass opacities with a rounded morphology present extending along the fissures and periphery of the lungs bilaterally (Figure 3).

Figure 1.

12-Lead electrocardiogram demonstrating the right ventricular strain pattern with T wave inversions involving the right precordial leads and inferior leads. Right ventricular dilatation is displayed with a dominant R wave in lead V1.

Figure 2.

Computed tomography angiography (CTA) of the chest coronal cross-section representing a large filling defect along the posterior and inferior wall of the right main pulmonary artery due to extensive pulmonary emboli.

Figure 3.

Computed tomography angiography (CTA) of the chest axial cross-section demonstrating bilateral interstitial infiltrates, as well as evidence of right heart strain illustrated by right ventricular dilation with a right ventricle to left ventricle ratio of >0.9.

In the Emergency Department, the patient’s oxygen saturation was 99%; however, on arrival to the intensive care unit (ICU) this was 84% on 4.5 L nasal cannula. On the initial physical exam in the ICU, the patient’s cardiovascular exam was normal with no cardiac thrill, a normal rate, regular rhythm, and no murmurs, gallops, or rubs auscultated. The patient’s lungs were clear to auscultation bilaterally but appeared to be in mild respiratory distress with accessory muscle use. The remainder of the physical exam was unremarkable. Supplemental oxygen demands increased, requiring 10 L on a non-rebreather ventilation mask, but the patient still remained hypoxic. This prompted a discussion with the patient who consented to endotracheal intubation, which was performed without any complications. The patient was intubated for 14 days, managed by using volume control without the ARDS protocol. She oxygenated well with low positive end-expiratory pressure and minimal fraction of inspired oxygen, both of which varied throughout her time spent on the ventilator. The patient intermittently required norepinephrine to augment blood pressure during her intubation.

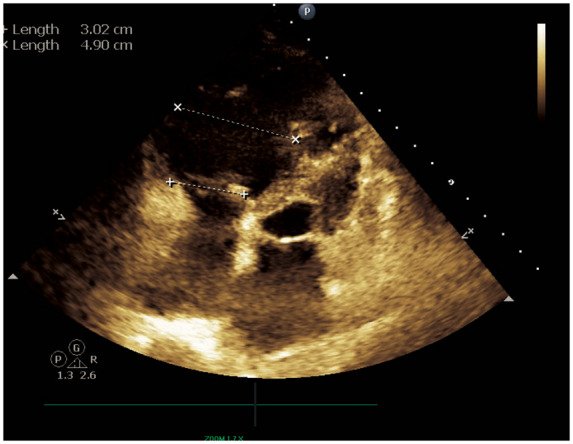

Transthoracic echocardiogram obtained in the ICU confirmed severe right ventricular dilatation with moderate pulmonary hypertension (Figure 4). Thrombus measuring 1.3 cm × 1.3 cm was appreciated in the right ventricle (Figure 5), with an echodensity present on the anterior tricuspid leaflet which was felt to represent thrombus (Supplementary material online, Video S1). Additionally, a thrombus measuring 1.4 cm × 1.9 cm was visualized in the dilated inferior vena cava (2.50 cm) (Figure 6). On day 4 of admission, the patient tested positive for the COVID-19 virus via nasopharyngeal swab polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

Figure 4.

Apical four-chamber echocardiographic view with right ventricular linear measurements displayed. Qualitatively, a severely dilated right ventricle is represented. Quantitatively, right ventricular size is increased by linear measurement of the chamber’s mid cavity (4.90 cm).

Figure 5.

Parasternal long-axis right ventricular inflow echocardiographic view. Thrombus measuring 1.30 cm × 1.29 cm is visualized in the right ventricular cavity.

Figure 6.

Subcostal long-axis window of the inferior vena cava displays an echodensity measuring 1.36 cm × 1.59 cm in the dilated inferior vena cava (measuring 2.50 cm).

The patient had a known history of unprovoked pulmonary embolism with hypoxic respiratory failure, giving us a high pre-test probability for pulmonary embolism. However, due to her recent history of fevers and shortness of breath, as well as being a local resident of a high exposure area, the suspicion of SARS-CoV-2 viral pneumonia was high. Therefore, COVID-19 PCR was sent via nasopharyngeal swab.

The patient was initially started on azithromycin 500 mg, on day 0 for 1 day, for possible pneumonia and for involvement of a possible COVID-19 viral pneumonia. After consulting with the infectious disease specialist, the patient was transitioned to doxycycline on day 1 and started on hydroxychloroquine due to fear of QT prolongation with the combination of hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin. Hydroxychloroquine was given for 5 days, with the initial day administering a 400 mg twice a day loading dose followed by four subsequent days of a 200 mg twice a day regimen. Doxycycline 100 mg twice a day was also administered for 5 days.

The patient’s pulmonary emboli and right ventricular thrombus were treated with intravenous heparin, started on day 1 and transitioned to enoxaparin 80 mg twice a day following extubation on day 14 of hospitalization. Intervention with catheter-directed thrombolysis was discussed with the interventional cardiologist; however, intravenous anticoagulation was not pursued due to the risks of the COVID-19 outweighing the benefits of the procedure.

Following extubation, the patient remained in the ICU step-down unit for 3 days for increased oxygen demand. She was screened for thrombosis using Doppler imaging which revealed a right popliteal deep vein thrombosis. The patient was then weaned down to room air on the general medical floors and evaluated by physical medicine and rehabilitation for inpatient rehabilitation therapy. Following extubation and prior to discharge, the patient had no new complaints, other than a hoarse voice which improved daily. On the date of discharge, her D-dimer remained elevated at 2.35 mg/L (0.00–0.056 mg/L). She was discharged on the therapeutic dose of enoxaparin, due to high insurance cost of novel oral anticoagulants and the patient’s refusal of coumadin, due to a history of vaginal bleeding with coumadin. The patient was deemed an excellent candidate for inpatient rehabilitation and tolerated the therapy well without complications. Following rehabilitation, the patient was instructed to report to her primary care physician and primary cardiologist as an outpatient, but has not followed up to date.

Discussion

Anecdotal reports of patients with SARS-CoV-2 have shown that patients may be susceptible to a hypercoagulable state. Several mechanisms have been proposed, including the viral infection leading to sepsis-like syndrome releasing inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-6, IL-8, tumour necrosis factor α (TNF-α), etc.3 It is well known that inflammatory cytokines activate the coagulation cascade which results in thrombosis. Another study showed that SARS-CoV-2 induces lymphocytopenia which allows the diminished T cells to be more susceptible to SARS-CoV-2, and this abnormal T-cell expression, and associated mRNA, have been shown to lead to venous thrombo-embolism.4 Additionally, due to the preventative efforts to quell the spread of SARS-CoV-2, many communities have been quarantined, leading to increased sedentary lifestyles, further increasing the risk of thrombotic events.

A recent retrospective analysis of 81 severe novel coronavirus pneumonia patients, as defined from the Fifth Revised Trial Version of the Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia Diagnosis and Treatment Guidance, in the ICU of Union Hospital in Wuhan China, showed that the incidence of venous thrombo-embolism was 25%. The same study highlighted a D-dimer value of 1.5 μg/mL as 85% sensitive, 88.5% specific, with the negative predictive value of 94.7% in predicting venous thrombo-embolisms.4 This elevated D-dimer mirrored another study from Wuhan, China, which showed that the non-survivors of coronavirus had a significantly higher D-dimer and fibrin degradation product (FDP) compared with the survivors. It is possible that these patients had micro- and macrovascular thrombosis, as seen in our patient. The study also showed a high prevalence of disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) in the non-survivors.5 A further study examining critically ill patients in Wuhan with SARS-CoV-2 found that they exhibited high rates of organ damage, with ARDS accounting for the most prevalent organ dysfunction (67%) and acute kidney injury (23%) disease, cardiac injury (29%), and liver dysfunction (2%).6 One explanation that has been hypothesized to elucidate the multiorgan damage seen in SARS-Cov-2 cases is injury through microvascular thrombi, which has been seen in MERS-CoV, another RNA virus.7

Although the majority of patients with this viral illness appear to recover, patients who develop a severe manifestation of the illness are at risk for ARDS, ICU admission, and possible respiratory failure. Current recommendations advise the routine monitoring of coagulation and inflammatory markers to accurately diagnose and treat patients with this viral illness.8 A recent study also suggests that critically ill patients with sepsis-induced coagulopathy or D-dimer greater than six-fold of normal have a decreased mortality rate with anticoagulation.9 Further studies need to be performed regarding the benefits of anticoagulation in critically ill SARS-CoV-2 patients, but clinicians should be aware of the potential for macrovascular and probably microvascular clot formation, especially in patients with previous history of deep vein thrombosis/pulmonary embolism.

Conclusion

SARS-CoV-2 is a novel infection still in its infancy in terms of understanding its effects. While the respiratory failure component is being extensively studied, the hypercoagulable state of these patients appears also to play a major role in the prognosis and disease progression. The medical community must be aware of the various complications that may be caused by this virus. Further research and analysis will need to be done to fully understand this viral illness.

Lead author biography

Jason G. Kaplan is a third-year internal medicine resident at McLaren Oakland in Pontiac Michigan. He graduated from Towson University with a Bachelor of Science in Biology. He went on to the University of Medicine and Health Sciences in St. Kitts where he obtained his medical degree. Jason will be applying to cardiology fellowships in 2020. His interests are in heart failure, echocardiographic imaging. and cardiac intervention.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at European Heart Journal – Case Reports.

Slide sets: A fully edited slide set detailing this case and suitable for local presentation is available online as Supplementary data.

Consent: the authors confirm that written consent for submission and publication of this case report including images and associated text has been obtained from the patient in line with COPE guidance.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Jason G Kaplan, McLaren Oakland/Michigan State Internal Medicine Residency Program, Pontiac, MI, USA.

Arjun Kanwal, Medstar Health Internal Medicine Residency Program, Baltimore, MD, USA.

Ryan Malek, McLaren Macomb Cardiology Fellowship, Mt. Clemens, MI, USA.

John Q Dickey, McLaren Macomb Cardiology Fellowship, Mt. Clemens, MI, USA.

Richard Keirn, McLaren Oakland/Michigan State Internal Medicine Residency Program, Pontiac, MI, USA.

Bryan Zweig, Henry Ford Hospital Department of Cardiology, Detroit, MI, USA.

David Minter, McLaren Oakland/Michigan State Internal Medicine Residency Program, Pontiac, MI, USA.

References

- 1. Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, Li X, Yang B, Song J, Zhao X, Huang B, Shi W, Lu R, Niu P, Zhan F, Ma X, Wang D, Xu W, Wu G, Gao GF, Tan W; China Novel Coronavirus Investigating and Research Team. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med 2020;382:727–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Janus SE, Hajjari J, Cunningham MJ, Hoit BD.. COVID19: a case report of thrombus in transit. Eur Heart J Case Rep 2020; doi.org/10.1093/ehjcr/ytaa189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Qin C, Zhou L, Hu Z, Zhang S, Yang S, Tao Y, Xie C, Ma K, Shang K, Wang W, Tian DS.. Dysregulation of immune response in patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. Clin Infect Dis 2020;doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cui S, Chen S, Li X, Liu S, Wang F.. Prevalence of venous thromboembolism in patients with severe novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost 2020;18:1421–1424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tang N, Li D, Wang X, Sun Z.. Abnormal coagulation parameters are associated with poor prognosis in patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost 2020;18:844–847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yang X, Yu Y, Xu J, Shu H, Xia J, Liu H, Wu Y, Zhang L, Yu Z, Fang M, Yu T, Wang Y, Pan S, Zou X, Yuan S, Shang Y.. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Resp Med 2020;8:47–481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Li K, Wohlford-Lenane C, Perlman S, Zhao J, Jewell AK, Reznikov LR, Gibson-Corley KN, Meyerholz DK, McCray PB Jr.. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus causes multiple organ damage and lethal disease and mice transgenic for human dipeptidyl peptidase 4. J Infect Dis 2016;213:712–722. 10.1093/infdis/jiv499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Han H, Yang L, Liu R, Liu F, Wu KL, Li J, Liu XH, Zhu CL.. Prominent changes in blood coagulation of patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Clin Chem Lab Med 2020;58:1116–1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tang N, Bai H, Chen X, Gong J, Li D, Sun Z.. Anticoagulant treatment is associated with decreased mortality in severe coronavirus disease 2019 patients with coagulopathy. J Thromb Haemost 2020;18:1094–1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.