Abstract

Background

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has caused a recent outbreak of coronavirus disease (COVID-19). In Cuba, the first case of COVID-19 was reported on March 11, 2020. Elderly individuals with multiple comorbidities are particularly susceptible to adverse clinical outcomes in the course of SARS-CoV-2 infection. During the outbreak, a local transmission event took place in a nursing home in Villa Clara province, Cuba, in which 19 elderly residents tested positive for SARS-CoV-2.

Methods

Based on the increased susceptibility to cytokine release syndrome, inducing respiratory and systemic complications in this population, 19 patients were included in an expanded access clinical trial to receive itolizumab, an anti-CD6 monoclonal antibody.

Results

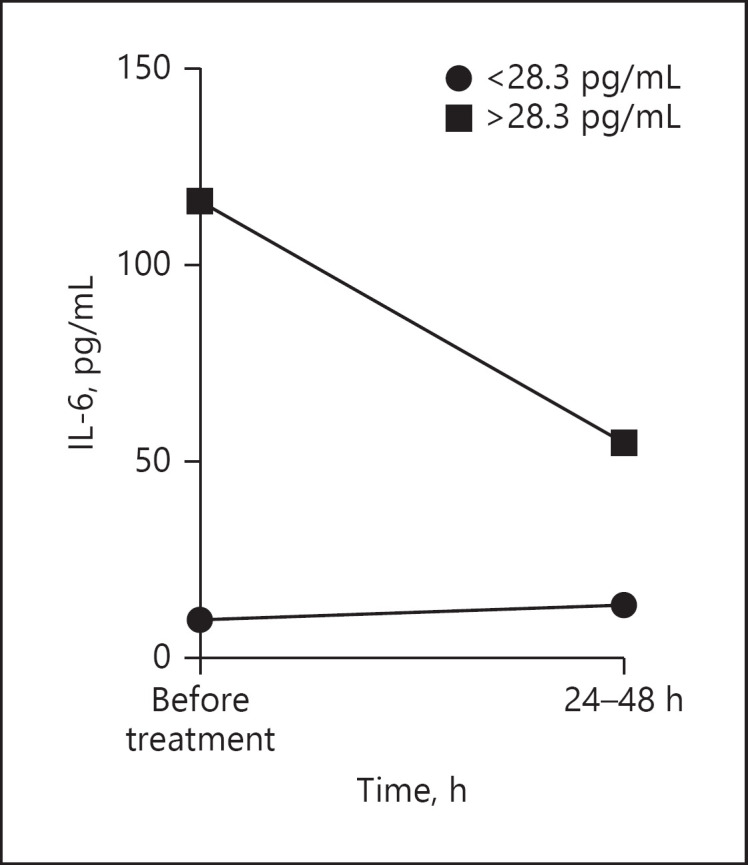

All patients had underlying medical conditions. The product was well tolerated. After the first dose, the course of the disease was favorable, and 18 of the 19 patients (94.7%) were discharged clinically recovered with negative real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction test results at 13 days. After one dose of itolizumab, circulating IL-6 decreased within the first 24–48 h in patients with high baseline values, whereas in patients with low levels, this concentration remained over low values. To preliminarily assess the effect of itolizumab, a control group was selected among the Cuban COVID-19 patients that did not receive immunomodulatory therapy. The control subjects were well matched regarding age, comorbidities, and severity of the disease. The percentage of itolizumab-treated, moderately ill patients who needed to be admitted to the intensive care unit was only one-third of that of the control group not treated with itolizumab. Additionally, treatment with itolizumab reduced the risk of death 10 times as compared with the control group.

Conclusion

This study corroborates that the timely use of itolizumab in combination with other antivirals reduces COVID-19 disease worsening and mortality. The humanized antibody itolizumab emerges as a therapeutic alternative for patients with COVID-19. Our results suggest the possible use of itolizumab in patients with cytokine release syndrome from other pathologies.

Keywords: Itolizumab, Elderly, COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, Immunomodulatory drugs

Introduction

From December 2019, the first cases of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pneumonia began to be registered in the Chinese city of Wuhan. A month later, the World Health Organization (WHO) confirmed that the cause of this pneumonia was severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). To date (June 23, 2020), 185 countries have reported cases of COVID-19, reaching a total of 9,063,264 confirmed cases, 471,681 deaths, and a lethality rate of 5.20%. In the Americas, 4,512,775 confirmed cases have been reported (49.79% of the total reported cases in the world) with a lethality rate of 5.02%. The first positive case in Cuba was informed on March 11, 2020, and to date, 2,319 positive cases have accumulated, with 85 deaths (June 25, 2020) [1].

COVID-19 can range from an asymptomatic to a critical disease. Many patients, mostly younger individuals, are asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic. Elderly people with pre-existing comorbidities are at higher risk of severe disease and fatal outcome [2]. Changes occurring in the immune system with increasing age, termed immunosenescence, as well as the state of chronic, low-grade inflammation known as inflammaging, characterize the immune system of the elderly. Both processes together are suggested as the origin of most of the comorbidities of older adults and their susceptibility to cancer, chronic inflammatory diseases, and new infections [3].

SARS-CoV-2 infection triggers a proinflammatory response characterized by high levels of cytokines including IL-6, as well as overexpression of other growth factors such as fibroblast growth factor, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, tumor necrosis factor-α, and vascular endothelial growth factor, among others. In some vulnerable patients, the disease might worsen up to admission to the intensive care unit (ICU) if no appropriate therapy is provided. Patients at this stage show high levels of proinflammatory cytokines. Particularly, many authors have found that IL-6 levels are directly correlated with increased mortality and lower lymphocyte count. Based on these findings, it has been suggested that the cytokine release syndrome may hinder the adaptive immune response against SARS-CoV-2 infection [4, 5].

High numbers of COVID-19-associated deaths have been seen in the nursing home sector. It is suggested that elderly patients residing in long-term care facilities could be more vulnerable to SARS-CoV-2 infection. This aged patient population has a higher risk of COVID-19-associated morbidity and mortality [6].

The Center of Molecular Immunology, Havana, Cuba, developed the humanized monoclonal antibody (MAb) itolizumab (CIMA-REG) capable of binding a region in the distal membrane domain of human CD6 (domain 1) [7]. The in vitro characterization of its mechanism of action revealed that it reduces the expression of intracellular proteins involved in the activation and proliferation of T cells. The effect is associated with the reduction of the production of proinflammatory cytokines (interferon [IFN]-γ, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor-α) [8]. Studies in blood and tissue samples from patients with severe psoriasis treated with this MAb showed that itolizumab reduced the proliferation capacity of T cells and the number of T cells producing IFN-γ. In addition, a reduction in serum IL-6 and IFN-γ levels was observed [9, 10].

In April 2020, a local transmission event was verified in a nursing home in Villa Clara, Cuba, in which 47 patients tested positive for SARS-CoV-2. Nineteen of these patients were admitted to a local hospital at a moderate stage of the disease. All patients were older than 64 years, and the majority of them were affected by hypertension and/or other comorbidities, which are risk factors associated with COVID-19 severity and fatal outcome. Based on the immunoregulatory action of itolizumab and the safety profile verified in previous severe COVID-19 patients, the use of itolizumab was proposed for treatment of the moderately ill elderly patients from the nursing home.

In this study we characterize the clinical features and outcomes of these 19 elderly patients treated with itolizumab combined with antiviral therapies.

Subjects and Methods

Patients

Nineteen patients confirmed as SARS-CoV-2 positive by real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and admitted from nursing home No. 3 in Santa Clara, Villa Clara, Cuba, were enrolled in an open, multicenter, expanded access clinical trial (RPCEC00000311 [VICTORIA]) with the humanized MAb itolizumab. All patients met the inclusion criteria described in the protocol (http://rpcec.sld.cu/trials/RPCEC00000311-En).

Treatment

The patients received the standard treatment (lopinavir/ritonavir [Kaletra], chloroquine, prophylactic antibiotics, INF-α2B, and low-molecular-weight heparin [LMWH]) included in the Cuban national protocol approved by the Ministry of Public Health for COVID-19 [11]. In addition, the patients received a first intravenous dose of 200 mg of itolizumab (8 vials). Some patients received a second dose (200 mg), considering their clinical evolution and the physician's criteria. Itolizumab-associated adverse events (AEs) were reported. Their classification was performed according to the NIH-CTC toxicity criteria, version 5.0.

Laboratory Examination

Laboratory results included routine blood testing, leukocyte subsets, and blood biochemical parameters. The level of inflammatory cytokines was measured using human Quantikine ELISA Kits from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA; Human IL-6 Quantikine ELISA Kit, Cat# S6050).

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables are expressed as means and standard deviation or medians and interquartile range (depending on the distribution of each variable). Wilcoxon rank-sum tests were applied to continuous variables, and the χ2 test or Fisher's exact test was used for categorical variables. Type I error α = 0.05 was used.

To preliminarily assess the effect of itolizumab, a control group was selected among the Cuban COVID-19 patients that did not receive immunomodulatory therapy. All patients with information in the COVID-19 national database on their recovery or death by June 30, 2020, were considered. Controls were defined as all subjects older than 64 years with at least one comorbidity considered to pose a serious risk for the disease (hypertension, ischemic heart disease, diabetes mellitus, cancer, chronic kidney disease, obesity, malnutrition, or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD]). The controls were treated with lopinavir/ritonavir, chloroquine, IFN-α2B, and LMWH. They were well matched regarding age, comorbidities, and severity of the disease.

The odds ratio for disease progression and mortality was estimated for itolizumab versus control. The number of patients needed to treat (NNT) to prevent an additional poor outcome and the absolute risk reduction were also calculated. The analysis was performed using SPSS 25.0 software.

Results

Baseline Characteristics of the Elderly COVID-19 Patients

The median age was 79 years (64–100); 63.2% were female and 68.4% were white-skinned. All patients had chronic underlying health conditions. The most frequent associated comorbidities were hypertension (73.7%), dementia (57.9%), malnutrition (52.6%), cardiac disease (42.1%), diabetes mellitus (31.6%), and COPD (26.3%). The majority of the patients suffered from more than one comorbidity (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the elderly COVID-19 patients, treatments, and outcomes

| Case No. | Age, years | Sex | Skin color | Comorbidities | Treatments | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 | 95 | F | White | Hypertension, ischemic heart disease, malnutrition, dementia | Itolizumab (2 doses), IFN-α2B, Kaletra, chloroquine, LMWH, parenteral vitamins | Alive |

| 13 | 83 | M | White | Hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, dementia | Itolizumab (2 doses), IFN-α2B, Kaletra, chloroquine, LMWH, parenteral vitamins | Alive |

| 14 | 78 | F | White | Malnutrition, dementia | Itolizumab (2 doses), IFN-α2B, Kaletra, chloroquine, LMWH, parenteral vitamins | Alive |

| 15 | 85 | F | Black | Hypertension, diabetes mellitus, malnutrition, dementia | Itolizumab (2 doses), Kaletra, chloroquine, LMWH, parenteral vitamins, antibiotics | Alive |

| 16 | 75 | F | White | Hypertension, diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, malnutrition | Itolizumab (2 doses), IFN-α2B, Kaletra, chloroquine, LMWH, parenteral vitamins | Alive |

| 17 | 68 | M | White | Hypertension, diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, dementia, smoking, hypertensive heart disease | Itolizumab (2 doses), IFN-α2B, Kaletra, chloroquine, LMWH, parenteral vitamins | Alive |

| 18 | 78 | F | NA | Dementia, anemia | Itolizumab (2 doses), IFN-α2B, Kaletra, chloroquine, LMWH, antibiotics | Alive |

| 19 | 88 | F | White | Hypertension, diabetes mellitus, ischemic heart disease, malnutrition | Itolizumab (2 doses), Kaletra, chloroquine, LMWH, antibiotics | Alive |

| 20 | 89 | F | White | Hypertension, ischemic heart disease, heart disease | Itolizumab (2 doses), IFN-α2B, Kaletra, chloroquine, heparin, antibiotics | Alive |

| 21 | 64 | M | White | Hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | Itolizumab (2 doses), IFN-α2B, Kaletra, chloroquine, heparin, vitamins | Alive |

| 22 | 80 | F | White | Hypertension, diabetes mellitus, ischemic heart disease, dementia | Itolizumab (2 doses), Kaletra, chloroquine, LMWH, parenteral vitamins | Alive |

| 24 | 79 | F | White | Hypertension, ischemic heart disease, malnutrition, dementia | Itolizumab (2 doses), Kaletra, chloroquine, LMWH, parenteral vitamins | Alive |

| 25 | 64 | M | White | Hypertension, diabetes mellitus, malnutrition, dementia, lower limbs amputated | Itolizumab (2 doses), IFN-α2B, Kaletra, chloroquine, LMWH, parenteral vitamins | Alive |

| 26 | 70 | F | Black | Hypertension, ischemic heart disease, malnutrition, dementia | Itolizumab (2 doses), IFN-α2B, Kaletra, chloroquine, LMWH, parenteral vitamins | Dead |

| 27 | 100 | F | Black | Hypertension, ischemic heart disease, malnutrition, dementia | Itolizumab (2 doses), Kaletra, chloroquine, LMWH, parenteral vitamins | Alive |

| 32 | 81 | F | NA | Hypertension, ischemic heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, malnutrition | Itolizumab (2 doses), IFN-α2B, Kaletra | Alive |

| 40 | 86 | M | White | None | Itolizumab (1 dose), IFN-α2B, Kaletra, chloroquine, heparin, erythropoietin | Alive |

| 43 | 67 | M | Brown | Obesity, smoking, alcoholism, posttraumatic paraplegia | Itolizumab (2 doses), Kaletra, chloroquine, heparin, erythropoietin | Alive |

| 44 | 71 | M | White | None | Itolizumab (1 dose), IFN-α2B, Kaletra, chloroquine, antibiotics, erythropoietin, steroids, omeprazole | Alive |

IFN-α2B, interferon alpha 2B; LMWH, low-molecular-weight heparin; NA, not available.

Upon admission, 42.1% of these elderly patients required oxygen therapy due to respiratory functional worsening. In addition, 52.6% had a fever, 47.3% had a cough, and 42.1% showed signs and symptoms of dehydration. Other symptoms included dyspnea (36.8%) and diarrhea (26.3%). Regarding the severity of the disease, the patients were classified as moderately ill.

Concerning hematological and biochemical parameters, 16.7% of the patients had leukocyte levels below the normal range. Lymphocytes were below the normal range in 29.4% of the patients, and 5.6% had low platelet counts. Aspartate aminotransferase was above normal values in 13.3% and D-dimer was increased in 84.6% of the patients.

Treatment with the Anti-CD6 MAb Itolizumab

The patients received treatment according to the established protocol in Cuba, upon confirmation of the presence of SARS-CoV-2. All subjects received lopinavir/ritonavir (Kaletra), 94.7% received chloroquine, 68.4% received IFN-α2B, and 89.5% received LMWH. Additionally, 63.2% received vitamins and 31.6% antibiotics. Three patients (15.8%) were treated with recombinant human erythropoietin at a cytoprotective dose (Table 1).

All individuals received one dose of the antibody, while 89.5% received two doses. The median time between the onset of symptoms and itolizumab administration was 1 day. The time between doses ranged from 1 to 7 days, with an overall median of 2 days. In this study, 94.7% of the patients were discharged after a median hospital stay of 13 days, ranging from 3 to 40 days. All of them were negative for SARS-CoV-2 at the time of discharge. The median time to RT-PCR negativity was 13 days. According the national protocol [1], the second sample was obtained 13 days after symptom onset. Earlier negativity was exceptionally evaluated in patients with rapid clinical recovery.

Only 1 event of death occurred (a 70-year-old woman). Her medical history included hypertension, coronary artery disease, dementia, and malnutrition. Daily electrocardiograms showed a left bundle branch block without sings of acute ischemia. The physicians declared that the direct cause of death was pulmonary thromboembolism.

Only 1 AE related to the administration of itolizumab was reported. The AE consisted of chills and occurred immediately after the first administration, lasting minutes. The AE was of mild intensity and did not imply changes in the administration of the antibody.

Vital signs were evaluated after itolizumab administration during the hospital stay. After 7 days of itolizumab treatment, only 2 patients required oxygen therapy (10.5%), and this reduction was statistically significant compared to baseline requirements (42.1 vs. 10.5%, p = 0.031, χ2 [McNemar test]).

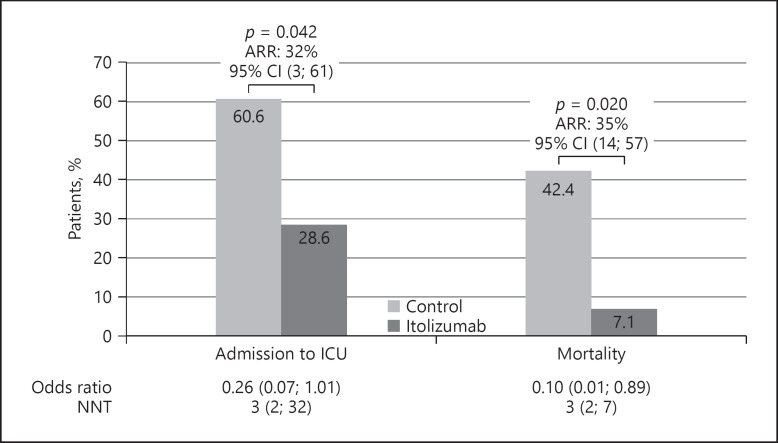

IL-6 serum levels were measured before and 24–48 h after treatment in 12 elderly patients. The median pretreatment concentration was 23.9 pg/mL, and the median IL-6 level 48 h after treatment was 25.9 pg/mL. Therefore, no significant changes were detected. In a previous work, a receiver operating characteristic curve was applied to select an IL-6 cut-off of 28.3 pg/mL to establish an association between baseline IL-6 concentration and severity of illness (unpublished data).

When analyzing the IL-6 serum values of our elderly patients regarding the selected cut-off, 5 patients had baseline levels above 28.3 pg/mL. Four of these 5 patients had reduced cytokine concentrations 24–48 h after itolizumab administration. In 1 patient, the IL-6 levels remained similar (Fig. 1). Among the 7 patients with baseline levels below the selected cut-off, in 6 patients circulating IL-6 levels did not increase to over 28.3 pg/mL. In a single individual, the IL-6 concentration increased (Fig. 1). In the patients with concentrations above the cut-off, the IL-6 reduction corresponded to 48.6 pg/mL. The median change in IL-6 concentration among the patients with baseline levels below 28.3 pg/mL was 2.2 pg/mL.

Fig. 1.

Median IL-6 concentration in the serum of COVID-19 patients before and 24–48 h after itolizumab treatment. The patients were divided according to the pre-established cut-off for IL-6 levels (28.3 pg/mL).

Clinical Outcomes of the Itolizumab-Treated Patients

A comparison of clinical evolution between the cohort from the nursing home (n = 19) and a group of Cuban COVID-19 patients with similar baseline conditions (control group) was performed. The control patients were defined as COVID-19-confirmed patients reported by the Cuban Ministry of Public Health. Among them, patients with similar baseline conditions to our cohort − i.e., those with at least one comorbidity (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, cardiac disease, cancer, chronic kidney disease, obesity, malnutrition, or COPD) and aged 64 years or older who were not included in other COVID-19 clinical trials − were selected (n = 53 patients). The control patients received the rest of the Cuban protocol drugs described above. The groups were homogeneous in terms of demographic characteristics and significant comorbidities, except for malnutrition, which occurred only in the itolizumab-treated group (p = 0.000, χ2 test).

Analyzing control and itolizumab-treated patients with two or more comorbidities, a significant dependence between itolizumab use and admission to the ICU or mortality was detected. Among every 3 moderately ill patients treated with itolizumab, 1 admission to the ICU was prevented (p = 0.042, χ2 test; NNT 3.12). Additionally, treatment with itolizumab reduced the risk of death 10 times as compared with the control group (1/0.10 = 10). Overall, 14 patients and 1 patient died in the control and the experimental group, respectively (Table 2). Among every 3 moderately ill patients treated with the MAb, 1 death was prevented (p = 0.020, χ2 test; NNT 2.93) (Fig. 2).

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of the patients treated with itolizumab versus the control patients not receiving immunomodulatory agents

| Control (n = 53) |

Itolizumab (n = 19) |

Total (N = 72) |

p (χ2) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | % | frequency | % | frequency | % | ||

| Sex | |||||||

| Female | 31 | 58.5 | 11 | 57.9 | 42 | 58.3 | 0.964 |

| Male | 22 | 8.0 | 8 | 42.1 | 30 | 41.7 | |

| Age, years | |||||||

| Mean (SD) | 79.0 (10.2) | 77.3 (10.2) | 77.9 (8.6) | 0.396 | |||

| Min.; max. | 64; 100 | 65; 101 | 64; 101 | ||||

| Number of comorbidities | |||||||

| 0–1 | 20 | 37.7 | 5 | 26.3 | 25 | 34.7 | 0.362 |

| 2 or more | 33 | 62.3 | 14 | 73.7 | 47 | 65.3 | |

| Arterial hypertension | 39 | 73.6 | 14 | 73.7 | 53 | 73.6 | 0.993 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 24 | 45.3 | 6 | 31.6 | 30 | 41.7 | 0.293 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 20 | 37.7 | 8 | 42.1 | 28 | 38.9 | 0.738 |

| COPD | 7 | 13.2 | 5 | 26.3 | 12 | 16.7 | 0.280 |

| Asthma | 3 | 5.7 | 1 | 5.3 | 4 | 5.6 | 1.000 |

| Cancer | 5 | 9.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 5 | 6.9 | 0.316 |

| Obesity | 2 | 3.8 | 1 | 5.3 | 3 | 4.2 | 1.000 |

| Malnutrition | 0 | 0.0 | 10 | 52.6 | 10 | 13.9 | 0.000 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 8 | 15.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 8 | 11.1 | 0.100 |

Bold type denotes significance. COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Fig. 2.

Clinical outcomes of itolizumab-treated and control patients: frequency of patient admissions to the ICU and mortality. The odds ratio for disease progression and mortality, the NNT to prevent an additional poor outcome (admission to the ICU or death), and the ARR were calculated for the itolizumab and control patients. Differences were considered significant at p < 0.05. ARR, absolute risk reduction; CI, confidence interval; ICU, intensive care unit; NNT, number needed to treat.

Discussion

Elderly patients are particularly susceptible to adverse clinical outcomes in the course of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Older adults with age-related diseases are more susceptible to a virus-induced cytokine storm resulting in respiratory failure, multisystemic damage, and fatal outcome [12]. The international scientific and medical community is searching intensively for adequate therapies that would reduce the damage and mortality associated with COVID-19 [12].

In April 2020, an episode of massive SARS-CoV-2 transmission occurred in nursing home No. 3 of Santa Clara in the province of Villa Clara, Cuba. Nineteen residents were infected by a visitor, who turned out to be positive for SARS-CoV-2 three days after visiting the facility. Residents of long-term care facilities are at high risk of COVID-19 transmission and are particularly prone to severe outcomes because they predominantly are aged and commonly have underlying medical conditions [6]. After the appearance of COVID-19-related symptoms, all patients were admitted to Manuel Fajardo Hospital. They immediately received the treatment protocol established in the country for this disease [11].

All patients in our cohort had other medical conditions. The most frequent were hypertension, dementia, malnutrition, cardiac disease, diabetes mellitus, and COPD. The median age was 79 years. People of any age with certain comorbidities such as hypertension, COPD, serious heart conditions, diabetes mellitus, and an immunocompromised state, but especially the elderly, are at an increased risk of severe illness from COVID-19 [13]. Fever, cough, dyspnea, signs of dehydration, and diarrhea were the most frequent symptoms on admission. The patients were classified as moderately ill. Treatment is challenging for elderly patients diagnosed with COVID-19. An individualized approach should be offered to older adults, properly analyzing the beneficial effects and risks of therapeutic decisions [12].

Based on the increased susceptibility to cytokine storm-associated respiratory and systemic complications [12], 19 patients were included in an expanded access clinical trial of itolizumab. This is a first-in-class antagonistic MAb that selectively targets the CD6-ALCAM pathway, reducing the activation, proliferation, and differentiation of T cells into pathogenic effector T cells and leading to a decrease in proinflammatory cytokine production [8].

The product was well tolerated, since only 1 mild adverse reaction was reported after the first infusion in 1 subject. In general, after the first dose, the course of the disease was favorable; only 2 patients required oxygen therapy after the treatment, and 94.7% of the patients were discharged with negative RT-PCR results at 14 days. This outcome suggests that although itolizumab is an immunomodulatory drug, it did not interfere with clearance of SARS-CoV-2.

Inflammation arises as a critical process in SARS-CoV-2-infected patients. While a strong immune response may contain the infection, previous studies have reported worse outcomes related to the presence of an excessive number of cytokines and inflammatory soluble factors [14]. Itolizumab decreased or stabilized IL-6 levels in our cohort of elderly patients within the first 24–48 h after administration. In 4 of the 5 patients with IL-6 baseline concentrations above the pre-established cut-off for severity (28.3 pg/mL; unpublished data), the levels decreased. In 1 patient, the IL-6 levels remained similar. Regarding those patients with IL-6 baseline levels below 28.3 pg/mL, only 1 subject had increased IL-6 values; the rest remained under this cut-off 24–48 h after administration.

Therefore, our findings suggest that the reduction in serum IL-6 levels in patients with high baseline concentrations, and their stabilization over low values, is a direct effect of this MAb. According to Robak et al. [15], the median IL-6 level in normal subjects is 5.3 pg/mL (0.5–16.6). Maurel et al. [16] evaluated IL-6 concentrations in a similar geriatric population from long-term care facilities (184 females and 65 males). At baseline, IL-6 was quantifiable (≥3 pg/mL) in only 35% of the evaluated subjects. The mean IL-6 concentration was 5.99 and 9.9 pg/mL for the men and the women, respectively. In that study, IL-6 levels of at least 3 pg/mL in men and 5.6 pg/mL in women were associated with a significantly higher risk of death [16]. In our series, all COVID-19 patients but one had IL-6 levels higher than 5 pg/mL. On the other hand, in a large meta-analysis of 52 papers, Elshazli et al. [17] found that the IL-6 level associated with COVID-19 severity was 22.9 pg/mL. The median concentration of IL-6 among our elderly patients was above this cut-off, highlighting their poor prognosis. We postulate that itolizumab inhibited T-cell activation and reduced IL-6 in subjects with elevated concentrations while preventing its further increase in individuals with lower levels at treatment.

Modulation of the severe inflammatory state in patients with COVID-19 consists in a relevant strategy for limiting the severity of pulmonary and systemic complications. This approach could successfully reduce the need for intensive care support and mechanical ventilation, and eventually decrease mortality [18]. When comparing our cohort of itolizumab-treated COVID-19 patients with a control group of Cuban COVID-19 patients with similar characteristics (age, comorbidities, and treatment except for itolizumab or another immunomodulatory agent), there emerged an effect of itolizumab in preventing severe disease. Apart from the controls, more than 50% of the itolizumab-treated patients had malnutrition. It is well established that a nutritional deficit is associated with a decrease in lymphocyte count, mainly of T cells. Furthermore, poor nutrition might provoke atrophy of the primary and secondary lymphoid organs, affecting adaptive immunity [19]. Undernutrition may also increase the replication and pathogenicity of a virus [19]. In spite of the malnutritional imbalance, itolizumab significantly decreased the risk of ICU admission, and reduced the risk of death 10 times.

Other anti-inflammatory drugs are under evaluation for treatment of the cytokine release syndrome associated with COVID-19. Tocilizumab, an IL-6R antibody, has been used mostly in patients with severe and critical COVID-19 disease. However, there are some reports of treatment of moderately ill patients. Toniati et al. [20] treated 57 patients in the conventional ward of a hospital in Brescia. Of these 57 patients, 13 (23%) worsened: 10 died and 3 were admitted to the ICU. Among 100 patients, 3 cases presented severe AEs including septic shock and gastric perforation.

Potere et al. [21] administered a low tocilizumab dose to 10 moderately ill patients on top of standard of care. The low-dose subcutaneous tocilizumab was well tolerated, and none of the patients progressed, suggesting that IL-6 receptor blockade may prevent COVID-19 progression when tocilizumab is administered early in the course of disease.

On the other hand, the RECOVERY trial showed that dexamethasone resulted in lower 28-day mortality only among those patients on invasive mechanical ventilation or oxygen but not among those not receiving respiratory support [22], suggesting its limited use for patients with moderate disease. In a separate study, 28-day mortality was not different between 194 moderately ill patients treated with methylprednisolone and 199 individuals receiving a placebo [23].

This study has some limitations, including the lack of a concurrent control group, the short kinetics of IL-6 levels, and the limited follow-up of the patients (their long-term outcomes are unknown). A longer evaluation of IL-6 kinetics in treated and control patients will be conducted as part of forthcoming itolizumab studies. Nevertheless, this study showed an effect of itolizumab in decreasing and controlling IL-6 serum levels. Moreover, itolizumab-treated patients had a favorable clinical outcome, considering their poor prognosis associated with old age and comorbidities, including nutritional deficits [24].

In conclusion, this study confirms that timely use of itolizumab, in combination with other antiviral and anticoagulant therapies, reduces COVID-19 disease worsening and mortality. The humanized antibody itolizumab emerges as a therapeutic alternative for patients with COVID-19 [24]. Our results suggest the possible use of itolizumab for patients with cytokine release syndrome from other pathologies.

Statement of Ethics

The clinical trial was approved by the Ethics Committee for Clinical Research of Manuel Fajardo Hospital in Villa Clara, Cuba. The Cuban Regulatory Agency (CECMED) also approved the trial. The study complied with the Good Clinical Practices and the precepts established in the World Medical Association Declaration of the Helsinki. All patients signed the informed consent form. A legal representative provided consent for patients with dementia. The reference number for the statement of ethics for the institutional study approval is CEI-IPK 48-20, available on the following website: http://rpcec.sld.cu/trials/RPCEC00000311-En.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

This study did not receive any financial support.

Author Contributions

T.C. and M.R.-S. designed the clinical trial, informed consent, and CRFs of the expanded access trial; Y.D., Y.M., N.A.C., W.S., O.V., Y.L.O., J.P.A.O., Y.P., A.C., and C.J.H. administered the experimental drug plus SOC and followed up the 19 COVID-19 patients at the hospital wards; G.L., M.C., and D.E. did the primary data collection, monitoring, and experimental drug control; Z.M. and D.S. determined IL-6 concentrations; P.L.-L. and C.V. made the statistical analysis; M.R.-S., D.S., Z.M., K.L., A.C., Y.D., T.C., and C.J.H. analyzed and interpreted the clinical and laboratory data; M.R.-S. and D.S. drafted the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors are extremely thankful to our patients and their relatives and to the research teams of Manuel Fajardo Hospital and the Center of Molecular Immunology.

References

- 1.Ministerio de Salud Pública [Internet] Cuba: Parte de cierre del día 25 de junio a las 12 de la noche. Available from: https://salud.msp.gob.cu/parte-de-cierre-del-dia-25-de-junio-a-las-12-de-la-noche/ [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and Important Lessons From the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Outbreak in China: Summary of a Report of 72 314 Cases From the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020 Apr;323((13)):1239–42. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fulop T, Larbi A, Dupuis G, Le Page A, Frost EH, Cohen AA, et al. Immunosenescence and Inflamm-Aging As Two Sides of the Same Coin: friends or Foes? Front Immunol. 2018 Jan;8:1960. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li G, Fan Y, Lai Y, Han T, Li Z, Zhou P, et al. Coronavirus infections and immune responses. J Med Virol. 2020 Apr;92((4)):424–32. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yao X, Ye F, Zhang M, Cui C, Huang B, Niu P, et al. In Vitro Antiviral Activity and Projection of Optimized Dosing Design of Hydroxychloroquine for the Treatment of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Clin Infect Dis. 2020 Jul;71((15)):732–9. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McMichael TM, Currie DW, Clark S, Pogosjans S, Kay M, Schwartz NG, et al. Public Health–Seattle and King County, EvergreenHealth, and CDC COVID-19 Investigation Team Epidemiology of Covid-19 in a Long-Term Care Facility in King County, Washington. N Engl J Med. 2020 May;382((21)):2005–11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2005412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alonso R, Huerta V, de Leon J, Piedra P, Puchades Y, Guirola O, et al. Towards the definition of a chimpanzee and human conserved CD6 domain 1 epitope recognized by T1 monoclonal antibody. Hybridoma (Larchmt) 2008 Aug;27((4)):291–301. doi: 10.1089/hyb.2008.0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nair P, Melarkode R, Rajkumar D, Montero E. CD6 synergistic co-stimulation promoting proinflammatory response is modulated without interfering with the activated leucocyte cell adhesion molecule interaction. Clin Exp Immunol. 2010 Oct;162((1)):116–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2010.04235.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rodriguez PC, Torres-Moya R, Reyes G, Molinero C, Prada D, Lopez AM, et al. A clinical exploratory study with itolizumab, an anti-CD6 monoclonal antibody, in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Results Immunol. 2012 Nov;2:204–11. doi: 10.1016/j.rinim.2012.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krupashankar DS, Dogra S, Kura M, Saraswat A, Budamakuntla L, Sumathy TK, et al. Efficacy and safety of itolizumab, a novel anti-CD6 monoclonal antibody, in patients with moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis: results of a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, phase-III study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014 Sep;71((3)):484–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.01.897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ministerio de Salud Pública [Internet] Cuba: Protocolo de Actuación Nacional para la COVID-19. Available from: https://files.sld.cu/editorhome/files/2020/05/MINSAP_Protocolo-de-Actuaci%C3%B3n-Nacional-para-la-COVID-19_versi%C3%B3n-1.4_mayo-2020.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perrotta F, Corbi G, Mazzeo G, Boccia M, Aronne L, D'Agnano V, et al. COVID-19 and the elderly: insights into pathogenesis and clinical decision-making. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2020 Jun;32((8)):1599–608. doi: 10.1007/s40520-020-01631-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang X, Yu Y, Xu J, Shu H, Xia J, Liu H, et al. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Respir Med. 2020 May;8((5)):475–81. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30079-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, Fan G, Liu Y, Liu Z, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020 Mar 28;395(10229):1054-62. Robak, T., Gladalska, A., Stepień, H., & Robak, E. Serum levels of interleukin-6 type cytokines and soluble interleukin-6 receptor in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Mediators Inflamm. 1998;•••:7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robak T, Gladalska A, Stepień H, Robak E. Serum levels of interleukin-6 type cytokines and soluble interleukin-6 receptor in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Mediators Inflamm. 1998;7((5)):347–53. doi: 10.1080/09629359890875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maurel S, Hamon B, Taillandier J, Rudant E, Bonhomme-Faivre L, Trivalle C. Prognostic value of serum interleukin-6 (IL-6) levels in long term care. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2007 Jul-Aug;45((1)):65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elshazli RM, Toraih EA, Elgaml A, El-Mowafy M, El-Mesery M, Amin MN, et al. Diagnostic and prognostic value of hematological and immunological markers in COVID-19 infection: A meta-analysis of 6320 patients. PLoS One. 2020 Aug;15((8)):e0238160. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0238160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arnaldez FI, O'Day SJ, Drake CG, Fox BA, Fu B, Urba WJ, et al. The Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer perspective on regulation of interleukin-6 signaling in COVID-19-related systemic inflammatory response. J Immunother Cancer. 2020 May;8((1)):e000930. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2020-000930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Silverio R., Gonçalves D. C., Andrade M. F., Seelaender M., Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) and Nutritional Status: The Missing Link? Advances in Nutrition. 2020 Sep 25; doi: 10.1093/advances/nmaa125. nmaa125. doi: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Toniati P., Piva S., Cattalini M., Garrafa E., Regola F., Castelli F, et al. Tocilizumab for the treatment of severe COVID-19 pneumonia with hyperinflammatory syndrome and acute respiratory failure: A single center study of 100 patients in Brescia, Italy. Autoimmunity reviews, 2020 Jul;19((7)):102568. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2020.102568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Potere N, Di Nisio M, Rizzo G, La Vella M, Polilli E, Agostinone A, et al. Low-Dose Subcutaneous Tocilizumab to Prevent Disease Progression in Patients with Moderate COVID-19 Pneumonia and Hyperinflammation. Int J Infect Dis. 2020 Aug;((Aug)) doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.07.078. S1201-9712(20)30616-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Horby P, Lim WS, Emberson JR, Mafham M, Bell JL, Linsell L, et al. RECOVERY Collaborative Group Dexamethasone in Hospitalized Patients with Covid-19 - Preliminary Report. N Engl J Med. 2020 Jul;•••:NEJMoa2021436. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jeronimo CM, Farias ME, Val FF, Sampaio VS, Alexandre MA, Melo GC, et al. for the Metcovid Team Methylprednisolone as Adjunctive Therapy for Patients Hospitalized With COVID-19 (Metcovid): A Randomised, Double-Blind, Phase IIb, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2020 Aug;••• doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1177. ciaa1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramos-Suzarte M, Diaz Y, Martin Y, Calderon NA, Santiago W, Vinet O, et al. Use of a humanized anti-CD6 monoclonal antibody (itolizumab) in elderly patients with moderate COVID-19. medRxiv. doi: 10.1159/000512210. 2020.07.24.20153833 [Preprint]; doi: https://doi.org/. Available from https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.07.24.20153833v1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]