Abstract

Patient: Male, 51-year-old

Final Diagnosis: COVID-19

Symptoms: Anosmia • dysgeusia • nocturnal diaphoresis

Medication: —

Clinical Procedure: —

Specialty: Infectious Diseases

Objective:

Rare co-existance of disease or pathology

Background:

Coinfection with severe acute respiratory syndrome-associated coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MBT) has been reported, albeit rarely, in various parts of the world and has received attention from health systems because up to one-third of the world’s population has been infected with SARS-CoV-2. Mexico was not included in the first-ever report on a global cohort of patients with this coinfection. We report on a case of SARS-CoV-2/MBT coinfection in a 51-year-old taxi driver from Mexico City that underscores the importance of rapid and accurate laboratory testing, diagnosis, and treatment.

Case Report:

We present the case of a man in the sixth decade of life who was admitted to the National Institute of Respiratory Diseases (INER) with a diagnosis of COVID-19 pneumonia, which was confirmed by nasopharyngeal exudate using real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) for the identification of SARS-CoV-2. Findings from imaging studies suggested that the patient might be coinfected with MBT. That suspicion was confirmed with light microscopy of a sputum sample after Ziehl-Neelsen staining and when a Cepheid Xpert MTB/RIF assay, an automated semi-quantitative RT-PCR assay, failed to detect rifampicin resistance. The patient was discharged from the hospital 10 days later.

Conclusions:

The present report underscores the importance of using validated molecular diagnostic tests to identify coin-fections in areas where there is a high prevalence of other causes of pneumonia, such as MBT, as a way to improve clinical outcomes in patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. While it is imperative to control the COVID-19 pandemic, the medical community must not forget about the other pandemics to which populations are still prey, and tuberculosis is one of them. We must remain alert to any clinical subtleties so as to ensure timely and accurate diagnosis and stay one step ahead of COVID-19.

MeSH Keywords: Coinfection, COVID-19, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Coronavirus Infections, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome, SARS Virus, Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction

Background

The coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19) pandemic has resulted in incalculable damage, from economic devastation to the collapse of health services in countries around the world. Included in the fractured health systems are programs that address other health emergencies, such as tuberculosis (TB) and HIV infection.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), as of August 31, 2020, there were 25 118 689 confirmed COVID-19 cases and just over 840 000 deaths due to the disease. More than half of all the confirmed cases have occurred in North and South America [1]. Besides being whipped by this pandemic, the Americas (especially Latin America and Mexico) have also been targets of TB, which caused 1.8 million deaths in 2015 according to the WHO [2].

Although it is rare, coinfection with severe acute respiratory syndrome-associated coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MBT) has been reported in various parts of the world. It has received much attention from health systems because up to one-third of the world’s population world is infected with MBT [2]. The first-ever global cohort of 49 cases of COVID-19/TB coinfection from 8 countries did not include Mexico because it had no such cases to report [3].

During the SARS outbreak in Singapore in 2004, Low et al. reported on 2 cases of SARS/pulmonary TB coinfection. As in the case described here, 1 patient was a man in the sixth decade of life, who was diagnosed with TB days after being discharged because of a persistent cough. In the case from Low and the 1 presented here, smoking was an important factor in the patients’ medical history and none had a history of TB. The authors of the report from Singapore theorized that their patients developed active pulmonary TB after acquiring SARS, probably as a result of SARS-induced temporary suppression of cellular immunity, which further predisposed the men to an aggravated reactivation or new infection with TB, as occurs in other viral infections, such as measles and HIV [4].

In China in 2006, 3 cases of SARS and 2 cases of TB were identified. In all 3 SARS cases, levels of CD4 -and CD8-positive cells were low, compromising the production of antibodies against SARS and delaying viral clearance [5].

Clinically, the similarities in signs and symptoms of SARS and TB, such as cough and dyspnea, may affect the diagnosis [4]. Timely diagnosis may be more likely now, given the current health emergency and presentation of patients with acute cases of COVID-19. Individuals with COVID-19 may exhibit characteristic symptoms of TB, such as hemoptysis, weight loss, and anorexia, as reported in a 19-year-old patient in the United States [4,6].

To make the diagnosis, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the WHO have approved the use of the Xpert MTB/RIF Assay, which returns results in 2 hours and has a sensitivity of 89% and a specificity of 99% [7–9]. It is an automated in vitro diagnostic test that uses nested real-time PCR (RT-PCR) for qualitative detection of the MTB complex and resistance gene to rifampicin in tissue or sputum samples. The assay can be performed with the GeneXpert instrument system, which is the tool recommended for diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 and MBT.

Motta et al., in an analysis of 2 previously described cohorts of 49 and 20 patients, determined that the mortality rate for SARS-CoV-2/MBT coinfection was up to 11.6%, and concluded that the decisive factors in the deaths were old age and comorbidities [10].

Up to one-third of the 49 patients described by Tadolini and her working group who had MBT/COVID-19 coinfection were diagnosed with COVID-19 as the first infection [11]. In 53% of the cases, coinfection with MBT was present prior to the SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis, in 18% the diagnoses were made simultaneously, and 85.7% had active MBT. The mean age of the patients was 45.5 years. Of them, 14.3% had recovered from MBT, on average 8.2 years before, and some sequelae were documented; 8 of them had some type of resistance to antituberculosis drugs. The mortality rate reported in the study was 12.3% [3]. The symptoms described by Tadolini et al. in the series were dry cough, chest tightness, shortness of breath, diarrhea, and fever. On blood tests, lymphopenia was the most characteristic finding. These authors also theorized that drugs used to treat COVID-19 leave patients “vulnerable” to development of other infections, such as MBT [11].

Chen et al. proposed that MTB infection status might be a specific risk factor for SARS-CoV-2 infection rather than for pneumonia in general. Their findings suggest the following: MTB infection is associated with more rapid development of symptoms, as well as development of more severe COVID-19 symptoms, and MTB infection could be a more important risk factor than other comorbidities commonly reported, such as diabetes and hypertension [12].

Case Report

We present the case of a 51-year-old-man from Mexico City who worked as a taxi driver. He denied having been in caves, mines or prisons, taking recent trips, or being in contact with patients confirmed to have COVID-19 or MBT. His medical history was significant for a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes mellitus 10 years previously. Since then, he had been taking metformin, but his adherence to the medication was poor.

On June 20, 2020, the man began experiencing anosmia, dysgeusia, and nocturnal diaphoresis. Two days later, he went to a health center for SARS-CoV-2 screening, and the results were positive. Three days after that, the patient went to a hospital, where he was admitted because of glycemic dysregulation; he was discharged on June 30, 2020. On July 4, 2020, the patient presented with complaints of bouts of intense coughing and shortness of breath and was evaluated at the National Institute of Respiratory Diseases. He could not recall what treatment he had received while hospitalized.

In the Emergency Department, the patient’s peripheral oxygen saturation was 75% on room air and recovered up to 92% with nasal cannulation at 5 liters per min. Physical examination revealed bilateral subscapular crackles but no other symptoms, so the man was admitted for diagnostic testing.

The results of initial arterial blood gas testing suggested a mixed acid-base disorder with metabolic acidosis and respiratory alkalosis. The only other significant finding on blood testing was thrombocytosis (512,000 cells/μL). Testing of a nasopharyngeal exudate sample with RT-PCR using the FDA-approved COVID-19 Plus RealAmp Kit was positive.

Regarding data from imaging, on inspiratory high-resolution computed tomography (CT), subpleural and bilateral ground-glass patchy opacities were visible, some of which had a tendency to consolidate, and an air bronchogram was suggestive of COVID-19. Likewise, a cavitary lesion was observed in the left pulmonary apex (Figures 1, 2) and adenopathy <1 cm was seen in the mediastinal window (Figures 3, 4). These findings may have been a result of the proinflammatory state caused by SARS-CoV-2.

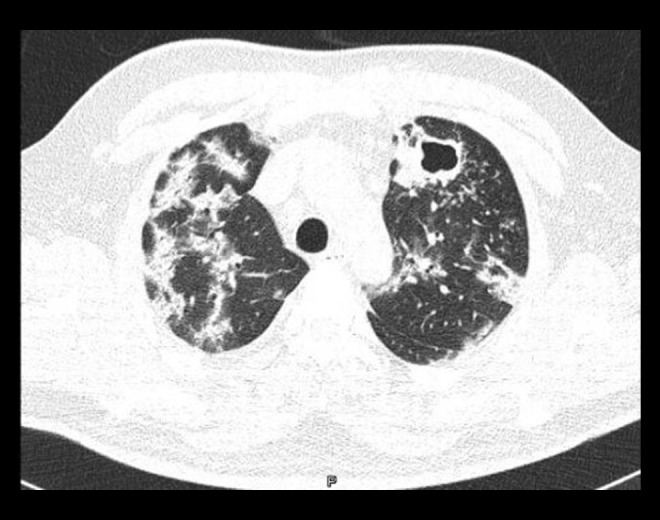

Figure 1.

Chest computed tomography scan with lung window. The low attenuation in the left upper lobe and walls >4 mm surrounded by multiple centrilobular micronodules are consistent with a cavitation. In the rest of the parenchyma, subpleural and peri-bronchovascular pulmonary consolidations are visible. The patient was coinfected with COVID-19 and tuberculosis.

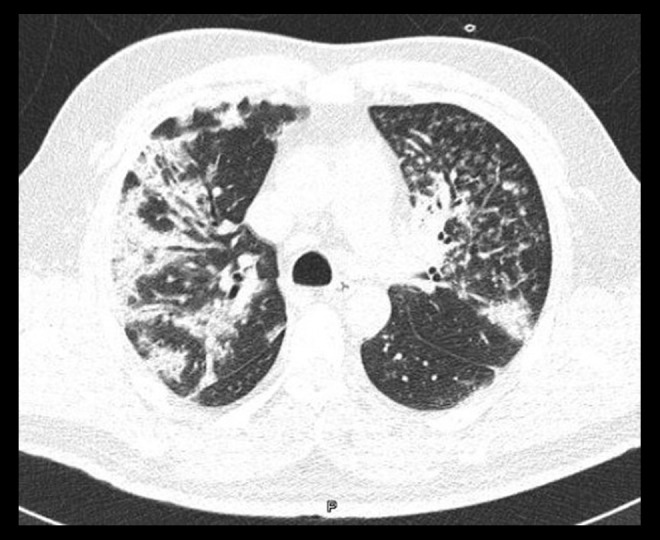

Figure 2.

Chest computed tomography scan with lung window. The high attenuation in the images is consistent with centrilobular nodules and micronodules, as is the tree-in-bud pattern in the left upper lobe.

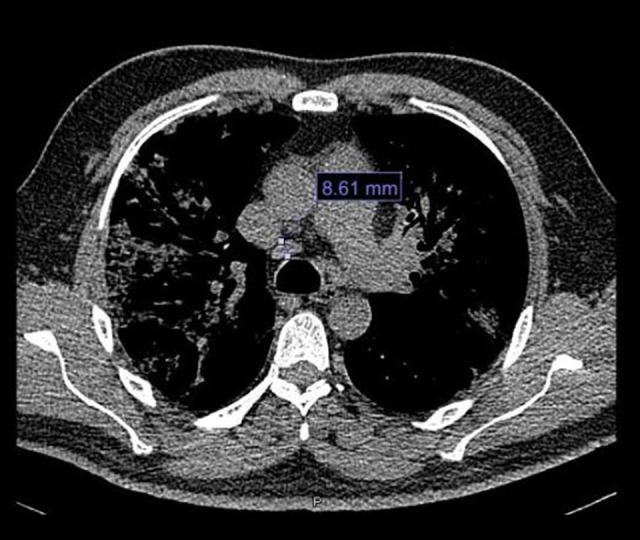

Figure 3.

Chest computed tomography scan with mediastinal window. Mediastinal nodes measuring 8.61 mm are seen in the image of station 4R.

Figure 4.

Chest computed tomography scan with mediastinal window, which shows 10.6-mm mediastinal nodes in the image of station 2R.

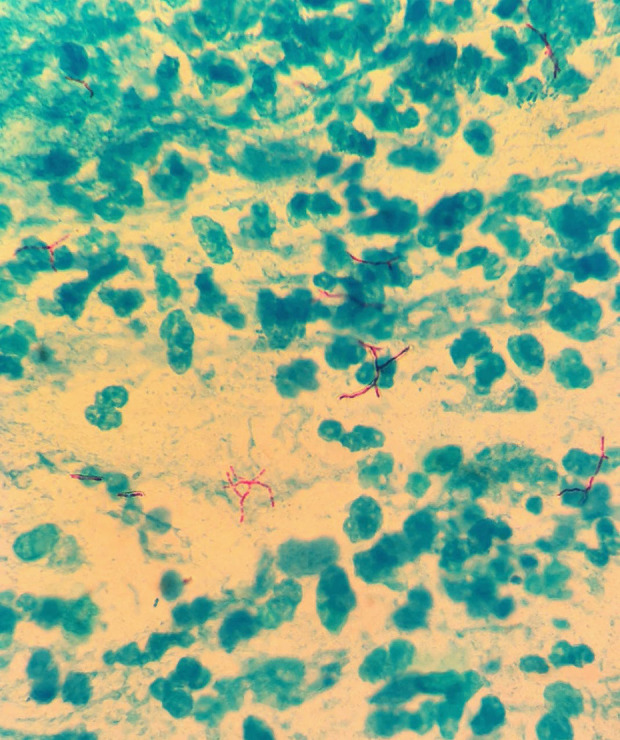

Because of the CT findings, bacilloscopy was performed, with positive results. Ziehl-Neelsen staining was performed on a smear taken from the direct expectoration sample (Figure 5). A GeneXpert MTR/RIF test also was performed, and returned positive for MBT sensitive to rifampicin.

Figure 5.

High-power photomicrograph taken with light microscopy which shows Ziehl-Neelsen staining (purple) of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in a sputum sample from a 51-year-old taxi driver from Mexico City. Magnification ×400.

The patient was started on a standard antituberculosis regimen (rifampicin, pyrazinamide, isoniazid, and ethambutol). No invasive mechanical ventilation was required His condition improved and he was discharged 10 days after admission and continued taking antituberculosis treatment for 9 months. Because the patient’s clinical presentation was not severe, he responded to conservative measures, and there is no safe or effective treatment for SAR-CoV-2, he received only supportive care for it and the treatment for TB.

Discussion

Incidence of COVID-19/MBT coinfection in countries like Africa and Mexico may be increased by a third, equally serious disease: HIV. Patients with it may be predisposed to COVID-19 or MBT because of immune system vulnerability [13].

On July 6, The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) reported that 14 countries had achieved the 90–90–90 HIV treatment goals (90% of people living with HIV know their HIV status, of whom 90% are on antiretroviral treatment, and of whom 90% are virally suppressed). However, with the advent of the COVID-19 pandemic, this progress may be undermined in the coming years. The number of deaths from and cases of HIV infection may increase, leading to a secondary increase in the number of cases of TB [14].

As noted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in a study in Taiwan in 2003, the screening model that was used during the SARS epidemic helped to identify cases of TB in an area in which the disease was endemic. Such was the case in Mexico, which underscores the importance of performing diagnostic testing to start treatment promptly, and thus, improve clinical outcomes in patients with this coinfection [15].

Zumla and his colleagues have estimated that in the next 5 years, the annual number of cases and deaths from TB may increase as attention is diverted away from TB treatment and prevention programs by the new COVID-19 pandemic [16,17].

According to an Italian study, lymphocytopenia and thrombocytopenia are commonly reported on laboratory testing of individuals with COVID-19/MBT coinfection. Of such patients evaluated in their institution, 95% presented with high levels of D-dimer and 63% of patients tested negative for SARSCoV-2 14 days after the first diagnosis. None of these patients were admitted to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) or required mechanical ventilation [18].

In contrast to the literature, in our reported case, the patient presented with thrombocytosis instead of thrombocytopenia. In keeping with published reports, our patient did not require invasive mechanical ventilation or ICU admission. He was given only antituberculosis therapy and no treatment for COVID-19.

In a study by He et al., 3 patients with SARS-CoV-2/MBT coinfection were identified, 2 of whom had histories of infection with MBT. The patient in our case, however, had not previously been diagnosed with TB [19].

In the few published reports of SARS-CoV-2/MBT coinfection, the TB diagnosis was made with a tuberculin test. Akbar et al. reported negative results of an acid-fast bacillus smear and culture and of an QuantiFERON-TB Gold test in the patient they described [6]. In our case, the diagnosis was made with bacilloscopy and the GeneXpert MTB/RIF test.

On imaging studies of patients with COVID-19, ground-glass opacities, consolidations with identifiable air bronchogram, and sequelae of previous cavitating lesions have been reported [19]. On CT, enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes and pulmonary nodules have been identified in these individuals [6]. COVID-19 also can manifest on chest CT as a crazy paving pattern or in airway changes or a reverse halo sign. Ye at al. noted bilateral distribution of ground-glass opacities with or without consolidation in the posterior and periphery of lungs as the cardinal hallmark of the disease [20].

In regard to treatment for SARS-CoV-2/MBT coinfection, standard antituberculosis therapy (pyrazinamide, rifampicin, isoniazid, and ethambutol) and hydroxychloroquine have been used and been well tolerated by most patients [18]. For early-stage infection, short-term glucocorticoid therapy, together with a standard anti-TB regimen, was the specific treatment adopted by He et al. That group identified a previous history of TB infection and longevity as risk factors for a poor prognosis and a longer recovery period in people infected with SARS-CoV-2 [19].

In the present case, we intentionally looked for presence of acute kidney injury, given the patient’s comorbidities and our group’s previous experience, but found no evidence of it [21].

Despite the few reported cases of MBT/COVID-19 coinfection, the medical and scientific community would do well to consider previous exposure to MBT in patients with milder presentations of SARS-CoV-2 infection. It has been hypothesized that Bacille Calmette-Guérin vaccination provides protection against respiratory infections through the molecular mimicry of the vaccine proteins and some viral structures, and the population of B and T lymphocytes derived from vaccination [22]. Tadolini et al. studied a cohort of 69 patients and identified a group of coinfected young migrant patients who developed mild symptoms of COVID-19 [3], which was probably due to previous MBT infection. However, evidence on COVID-19/MBT coinfection remains limited and the number of reported cases is minimal. Prospective studies with larger populations are required to elucidate the relationship between the 2 diseases.

With regard to mitigating the COVID-19 pandemic, as with TB, testing is recommended in any individual who has respiratory symptoms to prevent the spread of the 2 diseases, in both community and nosocomial settings [9]. It is even more important in patients who have symptoms that are non-acute, have become exacerbated, or are chronic.

Conclusions

The social, epidemiological, and public health situation in which we currently find ourselves unequivocally dictates that SARS-Cov-2 testing be performed on anyone who presents with respiratory and non-respiratory symptoms that have been documented to be associated with this infection. However, we should not lose sight of the possibility of coinfection with another microorganism in these individuals.

The present case report about SARS-CoV-2/MBT coinfection in a 51-year-old taxi driver from Mexico City underscores that, during the COVID-19 pandemic, in areas with a high prevalence of other causes of pneumonia, rapid and accurate assessment with validated molecular diagnostic tests can improve outcomes, even in patients with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Despite the urgent need to control the COVID-19 pandemic, the medical and scientific community should not forget the other pandemics, such as TB, to which populations are prey. We must remain alert to any clinical subtlety in order ensure that diagnosis is complete and accurate, and to keep one step ahead of SARS-CoV-2.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Santillán Segura Francisco Javier and Dr. Ramírez Estrada Edgar Ricardo for their support in reviewing this manuscript.

Footnotes

Department and Institution where work was done

National Institute of Respiratory Diseases, Mexico City, Mexico.

Conflict of interest

None.

References:

- 1.United Nations: World Health Organization (WHO) Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Situation report. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200731-covid-19-sitrep-193.pdf?sfvrsn=42a0221d_4.

- 2.United Nations: World Health Organization (WHO) 10 facts on tuberculosis. https://www.who.int/news-room/facts-in-pictures/detail/tuberculosis.

- 3.Tadolini M, Ruffo L, García-García JM, et al. Active tuberculosis, sequelae and COVID-19 co-infection: First cohort of 49 cases. Eur Respir J. 2020;56(1):2001398. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01398-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Low JGH, Lee CC, Leo YS. Severe acute respiratory syndrome and pulmonary tuberculosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38:e123–25. doi: 10.1086/421396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu W, Fontanet A, Zhang PH, et al. Pulmonary tuberculosis and SARS, China. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12(4):707–9. doi: 10.3201/eid1204.050264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akbar H, Kahloon R, Akbar S, Kahloon A. severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection mimicking as pulmonary tuberculosis in an inmate. Cureus. 2020;12(6):e8464. doi: 10.7759/cureus.8464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 7.World Health Organization (WHO) Use of laboratory methods for SARS diagnosis. 2020. https://www.who.int/csr/sars/labmethods/en/

- 8.Division of Microbiology Devices FDA/CDC: Revised device labeling for the Cepheid Xpert MTB/RIF assay for detecting Mycobacterium tuberculosis. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:193. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ndjeka N, Conradie F, Meintjes G, et al. Responding to SARS-CoV-2 in South Africa: What can we learn from drug-resistant tuberculosis? Eur Respir J. 2020;56(1):2001369. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01369-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Motta I, Centis R, D’Ambrosio L, et al. Tuberculosis, COVID-19 and migrants: Preliminary analysis of deaths occurring in 69 patients from two cohorts. Pulmonology. 2020;26(4):233–40. doi: 10.1016/j.pulmoe.2020.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tadolini M, García-García JM, Blanc FX, et al. On tuberculosis and COVID-19 co-infection. Eur Respir J. 2020;56(2):2002328. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02328-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen Y, Wang Y, Fleming J, et al. Active or latent tuberculosis increases susceptibility to COVID-19 and disease severity. MedRxiv. 2020;2020:20033795. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adepoju P. Tuberculosis and HIV responses threatened by COVID-19. Lancet HIV. 2020;(5):e319–20. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(20)30109-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.UNAIDS UNAIDS report on the global AIDS epidemic shows that 2020 targets will not be met because of deeply unequal success. Press Release. https://www.unaids.org/es/resources/presscentre.

- 15.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Nosocomial transmission of Mycobacterium tuberculosis found through screening for severe acute respiratory syndrome – Taipei, Taiwan, 2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004;53:321–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zumla A, Marais BJ, McHugh TD, et al. COVID-19 and tuberculosis-threats and opportunities. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2020;24(8):757–60. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.20.0387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Visca D, Tiberi S, Pontali E, et al. Tuberculosis in the time of COVID-19: Quality of life and digital innovation. Eur Respir J. 2020;56(2):2001998. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01998-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stochino C, Villa S, Zucchi P, et al. Clinical characteristics of COVID-19 and active tuberculosis co-infection in an Italian reference hospital. Eur Respir J. 2020;56(1):2001708. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01708-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.He G, Wu J, Shi J, et al. COVID-19 in tuberculosis patients: A report of three cases. J Med Virol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jmv.25943. [Online ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ye Z, Zhang Y, Wang Y, et al. Chest CT manifestations of new coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): A pictorial review. Eur Radiol. 2020;30(8):1–9. doi: 10.1007/s00330-020-06801-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sánchez A, González E, Martínez JA, et al. A 65-year-old woman with a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus and hypertension and a 15-day history of dry cough and fever who presented with acute renal failure due to infection with SARS-Cov-2. Am J Case Rep. 2020;21:e926737. doi: 10.12659/AJCR.926737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Redelman-Sidi G. Could BCG be used to protect against COVID-19? Nat Rev Urol. 2020;17(6):316–17. doi: 10.1038/s41585-020-0325-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]