Abstract

Background

Ecological Momentary Assessments (EMA) offer an approach to understand the daily risk factors of suicide and self-harm of individuals through the use of self-monitoring techniques using mobile technologies.

Objectives

This systematic review aimed to examine the results of studies on suicidality risk factors and self-harm that used Ecological Momentary Assessments.

Methods

Pubmed and PsycINFO databases were searched up to April 2020. Bibliographies of eligible studies were hand-searched, and 744 abstracts were screened and double-coded for inclusion.

Results

The 49 studies using EMA included in the review found associations between daily affect, rumination and interpersonal interactions and daily non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI). Studies also found associations between daily negative affect and positive affect, social support, sleep, and emotions and a person’s history of suicide and self-harm. Associations between daily suicide thoughts and self-harm, and psychopathology factors measured at baseline were also observed.

Conclusions

Research using EMA has the potential to offer clinicians the ability to understand the daily predictors, or risk factors, of suicide and self-harm. However, there are no clear reporting standards for EMA studies on risk factors for suicide. Further research should utilise longitudinal study designs, harmonise datasets and use machine learning techniques to identify patterns of proximal risk factors for suicide behaviours.

Keywords: Ecological momentary assessment, self-injurious behaviour, suicide, telemedicine, systematic review

Background

Suicide is one of the leading causes of death worldwide. According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), over 800,000 lives are lost annually through suicide.1 Despite decades of suicide research, epidemiological studies to date have been limited in the investigation of various psychological and behavioural risk factors for suicidal behaviours,2,3 among which a past suicide attempt remains as the strongest risk factor at present.1 Risk factors for suicide include sociodemographic factors (such as age and gender), education, history of suicide, social support, childhood and family adversity, and psychiatric disorders related to suicidal ideation.4–6 Most studies have been established to empirically investigate lifetime, or long-term, risk factors for suicidal behaviours.7,8 These risk factors are often examined using traditional assessments that measure risk factors at a single time point in a specific setting.7 However, warning signs that can indicate an immediate risk of suicide are less explored in the current literature. Mobile technologies like smartphones and wearables offer an opportunity to investigate daily, or short-term, risk factors for suicidal behaviours in real-time.9

Ecological Momentary Assessments (EMA) can be a useful approach to examining the short-term predictors of suicidal behaviour and self-harm. EMA is an approach that frequently monitors the psychological and behavioural aspects of people in real-time for a specific time period.10 It reduces retrospective recall biases by frequently monitoring people in their natural environment using repeated measurements on their mobile devices.11 Self-report assessments are deployed on mobile devices at fixed or random times of the day, or triggered at an event during the day. Recent studies using EMA often leverage smartphone and sensor technologies to collect momentary data.12 Repeated assessment within a relatively short period is an important aspect of EMA because it can provide mental health clinicians or services with timely information of people who may be at immediate risk of suicide.9,13 In particular, EMA can be well-suited to monitoring behaviours of individuals who are at high risk of suicide due to current suicidal ideation or current treatment for a mental disorder, such as a mood disorder or borderline personality disorder, because the intensity of suicidal ideation or mood can change dramatically within a short period.14

Previous literature reviews have examined the feasibility of EMA for suicide research and the multiple risk factors of suicidality. Rodríguez-Blanco, Carballo 15 reviewed studies using EMA that investigated non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI). They reviewed studies focusing on short-term periods of affect dynamics and emotion-regulation function in NSSI. Davidson, Anestis 16 showed how EMA could also be used to investigate suicidology, including the potential safety considerations of participants in EMA studies, but found a lack of studies using EMA to examine self-directed violence. Further, Kleiman and Nock 17 suggest the increased availability of smartphones makes this methodology more feasible, as automated messages can be sent to researchers or clinicians when a person reaches a threshold on a suicide-related measurement. This monitoring can play an important role in research on depression and suicidal behaviours, with considerable potential for implementation into clinical or community settings.18 Other literature reviews have found that daily changes in affective state are associated with suicide ideation and non-suicide self-injury.19,20

This systematic review aimed to review the results of studies that employed EMA to examine risk factors for suicide and self-harm. While the reviews by Rodríguez-Blanco, Carballo,15 Kleiman and Nock,17 and Davidson, Anestis 16 are relatively recent, there has been considerable new research conducted since these reviews were completed. Furthermore, no review has combined findings from EMA studies on suicide and NSSI to identify commonalities and differences. Another important gap in the EMA literature is a comprehensive systematic classification of the risk and protective factors for suicidality and self-harm, and a classification of the methods used in this area of research. Accordingly, this study summarises the emerging large number of EMA studies by topics and methods to understand the heterogeneity of the key findings.

Objectives

This systematic review aims to examine the results of studies on suicidality risk factors and self-harm that used EMA, including a summary of the methods used in different studies.

Methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

Pubmed and PsycINFO databases were searched up to 18th April 2020 using the search terms for the combination of the following three main concepts: “ecological momentary assessments”, and “suicide” (a list of specific search terms is available in Supplementary File 1, and a completed PRISMA checklist is available in Supplementary File 2). MeSH and Subject Heading keywords from relevant databases were included. Additional studies were identified by manually searching the reference lists of identified studies, to find additional research not identified in the database search.

Studies were included if they: 1) were published in English in a peer-reviewed journal; 2) examined suicide ideation, suicide behaviours, or self-harm behaviours; and, 3) employed an Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA) methodology.

Studies were excluded from consideration if they: 1) only examined psychological, behavioural, or psychological factors of an individual; 2) did not examine suicide ideation, suicide behaviours, or self-harm behaviours; 3) did not undertake repeated measurements in real-time to improve ecological validity of study findings (i.e., did not use EMA or measure only one repeated assessment per day).

Data extraction and synthesis

Three authors BLG, JH, and HB independently coded each of the 49 papers using a pre-formulated rating sheet. Any disagreements regarding coded papers were resolved following consensus discussions. Relevant information was extracted, which included the following: sample characteristics, demographic information, the description of the EMA methodological details, including the sampling strategy and the results. EMA sampling strategies include three protocol types: interval, signal or event. The interval-based sampling strategy is a protocol that permits a set number of momentary assessments at fixed times throughout the day. The signal-based sampling strategy is a protocol that permits a number of momentary assessments at random times throughout the day. The event-based sampling strategy is a protocol that gives individuals momentary assessments based on an event or trigger which may occur throughout the day.

Sample characteristics and the EMA methodological details were summarised using descriptive statistics. The heterogeneity of the populations and EMA methodology of the studies included in the synthesis ruled out the possibility of conducting a meta-analysis. Hence, a narrative synthesis of the study findings was summarised into several topics based on the measurements of the studies (as described below). Two authors independently assessed the quality of included studies, using a checklist based on the criteria developed by Trull and Ebner-Priemer.21 Discrepancies were resolved through discussion. The checklist assessed adequate reporting of sampling approach, study measurements, data quality, and study analysis.

Results

Search results

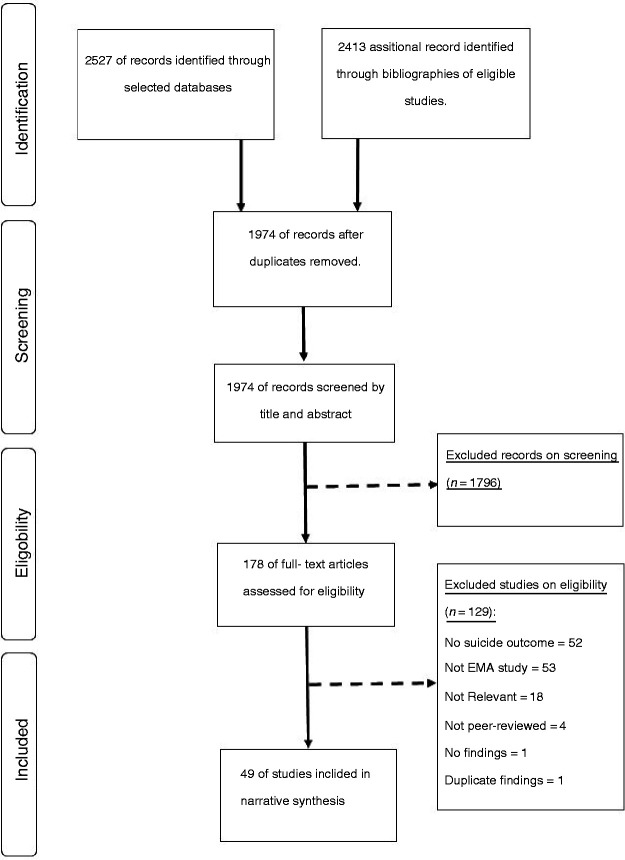

As shown in Figure 1, a total of 2527 records were retrieved from the database search. One additional record was retrieved from the hand-search of the bibliographies of eligible studies. A total of 876 records were duplicate abstracts, leaving 1974 unique records. Of these, the records of the titles and abstracts were screened, of which 1796 records were excluded. From these, the full-text of 178 records was assessed to determine eligibility, which yielded a total of 49 relevant papers that met all eligibility criteria.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the systematic review.

Overview of EMA studies

Sample characteristics and EMA methodology for each study are presented in Table 1. The majority of studies were conducted in the United States (n = 30 studies), with the remainder conducted in United Kingdom (n = 5), Germany (n = 5), Canada (n = 3), Australia (n = 2), Belgium (n = 2), China (n = 1), and Ireland (n = 1). Across the selected studies, the mean age of participants ranged from 12.0 to 53.7 years.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics and EMA methodological details.

| References, Country | Subgroup, setting (i.e., community, clinic, etc.) | N | Mean age (SD) | Female (%) | Diagnosis | EMA methodological details |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ammerman, Olino,39 United States | Subgroup: Adults in an urban environment.Setting: Clinic | 51 | 28.82 (9.8) | 74.5 | DD & BPD (DSM-IV) | Length of observation: 7 daysSample strategy (Frequency): Interval (4 per day) EMA tool: Mobile phoneEMA measures: • PA • NA • NSSI• Impulsive & aggressive feelingsCompliance: 78% completed |

| Andrewes, Hulbert,40 Australia | Subgroup: Young people Setting: Clinic | 132 | 18.1 (2.7) | 83.2 | BPD (DSM-IV) | Length of observation: 6 daysSample strategy (Frequency): Signal (6 per day) EMA tool: Mobile phoneEMA measures: • PA• NA• SIT• NSSICompliance: 51.56% completed |

| Andrewes, Hulbert,44 Australia | Subgroup: Young people with BPDSetting: Clinic | 107 | 18.1 (2.7) | 83.2 | Psychopathology (DSM-IV) | Length of observation: 6 daysSample strategy (Frequency): Signal (6 per day) EMA tool: Mobile phoneEMA measures: • PA• NA• NSSICompliance: 51.56% completed |

| Anestis, Silva,33 United States | Subgroup: Adults with BNSetting: Clinic and community | 127 | 25.34 (7.71) | 100 | Psychopathology (DSM-IV) | Length of observation: 14 daysSample Strategy (Frequency): SignalEMA tool: N/AEMA measures: • PA• NA (only negative subscale) Compliance: N/A |

| Armey, Crowther,31 United States | Subgroup: College studentsSetting: Community | 36 | 18.70 (0.79) | 75 | N/A | Length of observation: 7 daysSample strategy (Frequency): Signal (6 per day) and EventEMA tool: PDAEMA measures: • PA• NA• NSSI (behaviours, time spent, and severity of episode) Compliance: 89% completed |

| Coifman, Berenson,41 United States | Subgroup: Adults with BPDSetting: Clinic and community | 126 | 33 (12.2) | 77.80 | BPD (DSM-IV) | Length of observation: 21 daysSample Strategy (Frequency): Signal (5 per day) EMA tool: PDAEMA measures: • PA• NA• Perceived interpersonal stress• NSSI (impulsive behaviour) Compliance: 71% completed |

| Crowe, Daly,54 Ireland | Subgroup: Adults with MDDSetting: Clinic and community | 64 | S1: 44.4 (12.1) S2: 41.2 (14.4) | S1: 42 S2: 70 | MDD (DSM-IV) | Length of observation: 10 daysSample strategy (Frequency): Signal (6 per day) EMA tool: P&PEMA measures: • Affect• Self-esteem• SuicidalityCompliance: N/A |

| Depp, Moore,26 United States | Subgroup: Adults with/without suicidal ideationSetting: Clinic and community | 93 | 44.98 (10.5) | 56.60 | Schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder (DSM-IV) | Length of observation: 7 daysSample strategy (Frequency): Signal (10 per day) EMA tool: PDAEMA measures: • Time spent alone• Interpersonal interaction• Anticipating being aloneCompliance: 61.40% completed |

| Depp, Moore,28 United States | Subgroup: Outpatient with bipolar (suicide risk) Setting: Clinic and community | 41 | 46.90 (11.8) | 53.70 | Bipolar I or II (DSM) | Length of observation: 77 daysSample strategy (Frequency): Signal (2 per day) EMA tool: SmartphoneEMA measures: • Impulsivity• Affective rating• Daily life activities• Location• Social contextCompliance: 65.1% completed |

| Fitzpatrick, Kranzler,56 United States | Subgroup: People engaged in NSSISetting: Community | 47 | 19.07 (1.77) | 68.10 | N/A | Length of observation: 14 daysSample strategy (Frequency): Interval (5 per day) EMA tool: SmartphoneEMA measures: • NSSI thoughts• SSI behavioursCompliance: 80% completed |

| Hadzic, Spangenberg,51 Germany | Subgroup: Psychiatric inpatients Setting: Clinic | 74 | 37.61 (14.33) | 71.6 | Unipolar depressive disorder (DSM-IV) and Suicide Ideation (SBQ-R) | Length of observation: 6 daysSample strategy (Frequency): Signal (6 per day) EMA tool: N/AEMA measures: • Suicide ideationCompliance: N/A |

| Hallensleben, Glaesmer,55 Germany | Subgroup: Adults with passive and active suicidal ideationSetting: Clinic | 74 | 37.6 (14.3) | 72 | Unipolar affective depression (DSM-IV) | Length of observation: 10 daysSample strategy (Frequency): Signal (6 days) EMA tool: SmartphoneEMA measures: • Passive suicide ideation• Active suicide ideation• Depression• Hopelessness• Thwarted Belongingness• Perceived BurdensomenessCompliance: 89.7% completed |

| Hallensleben, Spangenberg,48 Germany | Subgroup: Psychiatric inpatientsSetting: Clinic | 20 | 35.9 (9.3) | 80 | Unipolar affective disorder (DSM-IV) | Length of observation: 6 daysSample Strategy (Frequency): Signal (10 per day) EMA tool: SmartphoneEMA measures: • Passive suicide intent• Active suicide intentCompliance: N/A |

| Hochard, Ashcroft,66 United Kingdom | Subgroup: University students who self-harmSetting: Community | 72 | 21.04 (3.4) | 88.89 | N/A | Length of observation: 5 daysSample strategy (Frequency): Interval (2 per day) EMA tool: P&PEMA measures: • Self-harm thoughts• Self-harm acts• NightmaresCompliance: 91.11% completed |

| Hochard, Heym,67 United Kingdom | Subgroup: University studentsSetting: Community | 72 | 21.04 (3.4) | 88.89 | N/A | Length of observation: 5 daysSample strategy (Frequency): Interval (2 per day) EMA tool: P&PEMA measures: PA• NA• Self-harm thoughts• Self-harm acts• NightmaresCompliance: 91.11% completed |

| Houben, Claes,42 Belgium | Subgroup: Psychiatric inpatientsSetting: Clinic | 30 | 29.03 (8.76) | 87 | BPD (DSM-IV) | Length of observation: 8 daysSample strategy (Frequency): Signal (10 per day) EMA tool: Palmtop computerEMA measures: • PA• NA• NSSI (act/behaviours) Compliance: 65.80% completed |

| Hughes, King,86 United States | Subgroup: Young adults who self-injuredSetting: Clinic and Community | 47 | 19.1 (1.77) | 68 | N/A | Length of observation: 14 daysSample strategy (Frequency): Signal (5 per day) and EventEMA tool: SmartphoneEMA measures: • Affect• NSSI thoughts and behaviours• Repeated Negative Thinking (RNT) Compliance: 80% completed |

| Humber, Emsley,57 United Kingdom | Subgroup: Adult from a penitentiary facilitySetting: Community | 21 | 36 | 0 | N/A | Length of observation: 6 daysSample strategy (Frequency): Signal (6 per day) and EventEMA tool: P&PEMA measures: • Anger• Psychological distress• Suicidal ideation• Universal eventsCompliance: 69% completed |

| Kleiman, Turner,62 United States | Subgroup: People from an online community and psychiatric inpatients that attempted suicide or with suicidal ideationSetting: Clinic and community | S1:54 S2:36 | S1: 23.24 (5.26) S2: 47.74 (13.06) | S1: 79.6 S2: 44.1 | N/A | Length of observation: 28 daysSample strategy (Frequency): Signal (4 per day) and EventEMA tool: SmartphoneEMA measures: • Suicidal ideation (S1 & S2) • Risk factors – hopeless, burdensome, and loneliness (S2) Compliance: • S1: 62.75% completed• S2: 62% completed |

| Kranzler, Fehling,62 United States | Subgroup: Young people engaged in NSSISetting: Clinic and Community | 47 | 19.07 (1.77) | 68 | BPD (DSM-IV) | Length of observation: 14 daysSample Strategy (Frequency): Signal (5 per day) and EventEMA tool: SmartphoneEMA measures: • Negative emotions• Positive emotions• NSSI (thoughts) • NSSI (behaviours) Compliance: 85.12% completed |

| Lavender, De Young,34 United States | Subgroup: People with EDSetting: Clinic and community | 118 | 25.3 (8.4) | 100 | AN (DSM-IV) |

|

| Lavender, Wonderlich,35 United States | Subgroup: People with EDSetting: Clinic and community | 116 | 25.3 (8.4) | 100 | AN (DSM-IV) | Length of Observation: 14 daysSample Strategy (Frequency): Signal (6 per day) and EventEMA tool: Palmtop computerEMA measures: • PA• NA• Self-discrepancy• Eating behavioursCompliance: 87-89% completed |

| Law, Furr,47 United States | Subgroup: People with/without BPDSetting: Clinic and community | 282 | 43.9 (11.2) | 67 | BPD (DSM-IV) | Length of observation: 14 daysSample strategy (Frequency): Interval (1–5 per day) EMA tool: Palmtop computerEMA measures: • BPD symptoms• Suicide attempt• Suicidal ideation• Self-harmCompliance: 65% completed |

| Links, Eynan,27 Canada | Subgroup: Psychiatric outpatient with BPDSetting: Clinic | 82 | 33.5 (10.3) | 83 | BPD (DSM-IV) | Length of observation: 21 daysSample strategy (Frequency): Signal (6 per day) EMA tool: P&PEMA measures: • Mood• SituationCompliance: 58.10% completed |

| Littlewood, Kyle,69 United Kingdom | Subgroup: People with suicide ideationSetting: Community and clinic | 51 | 35.47 (12.81) | 67 | MDD (DSM-IV) | Length of observation: 7 daysSample Strategy (Frequency): Mixed (6 per day) EMA tool: ActigraphyEMA measures: • Subjective sleep quality• Suicide ideation• EntrapmentCompliance: 84-94% completed |

| Muehlenkamp, Engel,36 United States | Subgroup: People with BN and with/without NSSISetting: Community | 131 | 25.3 (7.6) | 100 | BN (DSM-IV) | Length of observation: 14 daysSample strategy (Frequency): Interval (6 per day) EMA tool: Palmtop computerEMA measures: • PA• NA• NSSICompliance: N/A |

| Nisenbaum, Links,87 Canada | Subgroup: Psychiatric outpatient with BPDSetting: Clinic | 82 | 33.5 (10.3) | 83 | BPD (DSM-IV) | Length of observation: 21 daysSample strategy (Frequency): Signal (6 per day) EMA tool: P&PEMA measures: • MoodCompliance: 85% completed |

| Nock, Prinstein,29 United States | Subgroup: People with Suicidal and NSSI thoughtsSetting: Community | 30 | 17.3 (1.9) | 87 | N/A | Length of observation: 14 daysSample strategy (Frequency): Interval (2 per day) and EventEMA tool: PDAEMA measures: • Self-destructive thoughts• Self-destructive behaviours (suicide attempt or NSSI) • Intensity, duration, and context of thoughtsCompliance: 83% completed |

| Oppenheimer, Silk,59 United States | Subgroup: People with anxietySetting: Community | 36 | 13.56 (1.50) | 53 | Anxiety disorders (DSM-IV) | Length of observation: 14 daysSample strategy (Frequency): Signal (14 across 5 days) EMA tool: Mobile phoneEMA measures: • Negative social experienceCompliance: N/A |

| Palmier-Claus, Taylor,50 United Kingdom | Subgroup: Participants from RCT on early detection servicesSetting: Clinic | 27 | 22.6 (4.4) | 51 | Ultra-High Risk Psychosis | Length of observation: 6 daysSample strategy (Frequency): Signal (10 per day) EMA tool: P&PEMA measures: • PA• NACompliance: N/A |

| Pearson, Pisetsky,49 United States | Subgroup: People with BNSetting: Clinic and Community | 133 | 25.3 (7.6) | 100 | BN (DSM-IV) | Length of observation: 14 daysSample strategy (Frequency): Signal (7 per day) EMA tool: PDAEMA measures: • Binge eating and purging• Risky behaviours: self-harm, substance misuse, and reckless behavioursCompliance: N/A |

| Rizk, Choo,52 United States | Subgroup: People with BPDSetting: Community | 38 | 28.6 (9.5) | 100 | N/A | Length of Observation: 7 daysSample Strategy (Frequency): Signal (6 per day) EMA tool: PDAEMA measures: • Suicide ideation• Self-harm urgesCompliance: N/A |

| Santangelo, Koenig,60 Germany | Subgroup: Adolescent with BPD and who engaged with/without NSSISetting: Clinic and community | 46 | 15.9 (1.25) | 100 | BPD (DSM-IV) | Length of observation: 4 daysSample strategy (Frequency): Signal (12 per day) EMA tool: SmartphoneEMA measures: • Mood• Interpersonal stateCompliance: 82% completed |

| Selby, Franklin,23 United States | Subgroup: People who or who not experience NSSISetting: University and community | 47 | N/A | 66 | Psychopathology (DSM-IV) | Length of observation: 14 daysSample strategy (frequency): Signal (5 per day) EMA tool: PDAEMA measures: • PA• NA• Rumination• NSSICompliance: 90% completed |

| Selby and Joiner,24 United States | Subgroup: People diagnosed with or without BPDSetting: University and Community | 47 | N/A | 66 | BPD (DSM-IV) | Length of observation: 14 daysSample strategy (Frequency): Signal (5 per day) EMA tool: PDAEMA measures: • PA• NA• Rumination• Dysregulated behaviours (include NSSI)Compliance: 90% completed |

| Selby, Nock,64 United States | Subgroup: People who or who do not experience APRSetting: Clinic | 30 | 17.3 (1.9) | 87 | N/A | Length of observation: 14 daysSample strategy (Frequency): Interval (2 per day) and EventEMA tool: PDAEMA measures: • NSSI (behaviour and thoughts) • Dysregulated behavioursCompliance: 83% completed |

| Selby, Kranzler,30 United States | Subgroup: Adolescent who NSSISetting: Community | 47 | 19.7 (1.77) | 68.1 | N/A | Length of observation: 14 daysSample strategy (Frequency): Signal (5 per day) and EventEMA tool: SmartphoneEMA measures: • NSSI• Physical pain• Negative emotionsCompliance: 80% completed |

| Snir, Rafaeli,46 United States | Subgroup: People diagnosed with or without BPD and APDSetting: Community | 152 | N/A | N/A | BPD (DSM-IV) and APD | Length of observation: 21 daysSample strategy (Frequency): Signal (5 per day) EMA tool: N/AEMA measures: • NSSI (episodes) • NSSI (urges) • Affect • Cognition• Behaviours that inferred motivesCompliance: N/A |

| Spangenberg, Glaesmer,63 Germany | Subgroup: People diagnosed with depressionSetting: Clinical | 74 | 37.6 (14.3) | 72 | Unipolar depressive disorder (DSM-IV) | Length of observation: 6 daysSample strategy (Frequency): Signal (10 per day) EMA tool: SmartphoneEMA measures: • Suicidal ideation (passive) • Suicidal ideation (active) • Capability of SuicideCompliance: 89.7–95.4% completed |

| Tian, Yang,25 China | Subgroup: Full-time workersSetting: Community | 231 | 27.63 (3.73) | 100 | N/A | Length of observation: Used DRMSample strategy (Frequency): EventEMA tool: N/AEMA measures: • PACompliance: N/A |

| Turner, Yiu,38 Canada | Subgroup: People with NSSI and EDSetting: Community | 60 | 23.12 (3.81) | 92 | Psychiatric Disorders (DSM-IV) | Length of observation: 14 daysSample strategy (Frequency): Interval (3 per day) EMA tool: N/AEMA measures: • NSSI (behaviours) • Binge eating• Purging • MoodCompliance: N/A |

| Turner, Cobb,37 United States | Subgroup: People with NSSISetting: Community | 60 | 23.25 (4.25) | 85 | Psychiatric Disorders (DSM-IV) | Length of observation: 14 daysSample strategy (Frequency): Interval (3 per day) EMA tool: N/AEMA measures: • NSSI (behaviour) • NSSI (urges) • Perceived social support• Interpersonal conflict• NACompliance: N/A |

| Turner, Wakefield,22 United States | Subgroup: Students who engaged in or did not engage in NSSISetting: Clinic and Community | 116 | 23.50 (4.66) | 78 | Psychiatric Disorders (DSM-IV) and NSSI | Length of observation: 14 daysSample Strategy (Frequency): IntervalEMA tool: N/AEMA measures: • Interpersonal contact• Social support• Negative interpersonal interactions• NA• Coping strategiesCompliance: 86.2% completed |

| Vansteelandt, Houben,45 Belgium | Subgroup: Patients with and without NSSISetting: Clinic | 32 | 28 (9) | 84 | BPD (DSM-IV) | Length of observation: 8 daysSample strategy (Frequency): Signal (10 per day) EMA tool: PDAEMA measures: • Affect• NSSI actsCompliance: 63% completed |

| Victor, Scott,43 United States | Subgroup: Young adult women with internalising and externalising NASetting: Community | 62 | 22.0 (1.55) | 100 | BPD (DSM-IV) | Length of observation: 21 daysSample strategy (Frequency): Interval (6 per day) EMA tool: Mobile PhoneEMA measures: • Affect• Interpersonal Experience• Self-Injurious urgesCompliance: 85-50% completed |

| Vine, Victor,53 United States | Subgroup: Adolescent with BPD and history of suicidalitySetting: Clinic | 162 | 12.03 (0.92) | 47 | BPD (DSM-IV) and suicide ideation and attempts | Length of observation: 4 daysSample strategy (Frequency): Interval (10 per day) EMA tool: SmartphoneEMA measures: • Dissociations• Suicide thoughts• Daily thoughtsCompliance: 88.8 – 90.1% completed |

| Woosley, Lichstein,68 United States | Subgroup: People with insomniaSetting: Community | 786 | 53.73 (19.84) | 51 | N/A | Length of observation: 14 daysSample Strategy (Frequency): Interval (2 per day) EMA tool: P&PEMA measures: • Sleep behaviourCompliance: N/A |

| Wright, Hallquist,58 United States | Subgroup: Psychiatric inpatients with BPDSetting: Clinic | 5 | 20–30 | 80 | BPD | Length of observation: 21 daysSample strategy (Frequency): Interval and EventEMA tool: SmartphoneEMA measures: • PA• NA• Interpersonal interactions• Aggression• Substance useCompliance: N/A |

| Zaki, Coifman,65 United States | Subgroup: People with BPDSetting: Clinic and community | 38 | 29.89 (10.6) | 84 | BPD (DSM-IV) | Length of observation: 21 daysSample strategy (Frequency): Signal (5 per day) EMA tool: PDAEMA measures: • Negative emotions• Positive emotions• NSSI acts • NSSI urgesCompliance: N/A |

PA: positive affect; NA: negative affect; NSSI: non-suicidal Self Injury; SIT: self-injurious thoughts; APR: automatic positive reinforcement; DD: depressive disorder; BPD: borderline personality disorder; BN: bulimia nervosa; AN: anorexia nervosa; ED: eating disorder; MDD: major depressive disorder; APD: avoidant personality disorder; PDA: portable device assistant; P&P: pen and paper; S1: Study 1; S2: Study 2; RCT: randomised controlled Trial; DRM: day reconstruction method (prompts participants based on sequences of events from previous day)

Included studies examined individuals diagnosed with Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) (n = 13), bipolar or unipolar affective disorder and/or Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) (n = 7), multiple psychiatric disorders (n = 5), psychopathology (n = 3), Bulimia Nervosa (BN) (n = 2), Anorexia Nervosa (AN) (n = 2), schizophrenia and psychosis (n = 2), and anxiety disorders (n = 1). Only one study examined individuals diagnosed with psychiatric disorders and a history of NSSI.22 Thirteen studies did not examine individuals with diagnosed mental disorders. Included articles also recruited participants in a community setting (n = 16 studies), and in clinical settings (n = 15). Furthermore, studies recruited participants in both clinic and community settings (n = 16), whereas only two studies recruited participants in university and community settings.23,24 On average, 75.7% (SD = 19.6) of participants across all of the samples identified as female. The average number of days of observation was 13 (range = 4 to 77).

Various sampling strategies were used in the included studies, including signal-based sampling strategies (n = 23), and interval-based sampling strategies (n = 12). Only one study used event-based sampling strategies.25 Thirteen studies used mixed-based sampling strategies using event-based and signal-based or interval-based sampling strategies. Across all studies, the average number of EMA assessments per day was six (range 2 to 14). Further, the average number of completed EMA assessments across all studies was 77% (SD = 13.8). Included studies used mobile phones or smartphones to collect EMA data (n = 17), Portable Device Assistants (PDA) (n = 11), pen and paper (n = 8), palmtop computers (n = 5) and actigraphy (n = 1). Lastly, seven studies did not report on the tool used to collect EMA data.

Table 2 provides a summary of the daily measurements used in all studies. Nearly half of the studies measured day-to-day levels of affect, mood, and mental health, including Positive Affect (PA) and Negative Affect (PA). Several studies measured daily self-harm, including Non-suicidal Self Injury (NSSI), Self-injurious Thoughts (SIT), suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and suicide risk behaviours. A variety of other daily measurements were utilised in each study, including social factors, psychological factors, risk behaviours, and other behaviours such as eating behaviours, sleep behaviours, nightmares, and cognition.

Table 2.

Summary of daily measurements used in EMA studies.

| Daily measurements | Studies (n) |

|---|---|

| Affect mood and mental health (48 studies) | |

| Positive affect | 15 |

| Negative affect | 16 |

| Affective states | 6 |

| Mood | 4 |

| Mental disorder symptoms | 2 |

| Emotions | 3 |

| Psychological distress and anxiety | 2 |

| Suicide-related predictors (39 studies) | |

| Non-suicidal Self Injury (NSSI) | 20 |

| Suicidal Ideation and Self-Injurious Thoughts (SIT) | 10 |

| Self-harm (direct) | 4 |

| Suicide attempt | 2 |

| Risky and dysregulated behaviours | 3 |

| Social factors (17 studies) | |

| Interpersonal interaction | 9 |

| Events and activities | 2 |

| Location and situation | 3 |

| Social support | 2 |

| Being alone | 1 |

| Psychological factors (9 studies) | |

| Impulsive and aggressive feelings | 4 |

| Coping strategies | 1 |

| Self-discrepancy | 1 |

| Behaviours that inferred motives | 1 |

| Self-esteem | 1 |

| Negative thinking | 1 |

| Other daily measurements (15 studies) | |

| Eating behaviours | 4 |

| Rumination | 2 |

| Nightmares | 2 |

| Sleep behaviours | 2 |

| Substance use | 1 |

| Cognition | 1 |

| Entrapment | 1 |

| Physical pain | 1 |

| Dissociation | 1 |

Quality of EMA studies

Table 3 presents the methodology quality for each of the included articles using a checklist based on existing criteria.21 Most of the EMA studies were absent or partial of adequate reporting in data quality and study analysis.

Table 3.

Quality of EMA studies assessed by a checklist based on the criteria by Trull and Ebner-Priemer.21

| Articles | Adequate reporting of sampling approacha | Adequate reporting of measurementsb | Adequate reporting of data qualityc | Adequate reporting of study analysisd |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ammerman, Olino39 | Partial | Partial | Partial | Complete |

| Andrewes, Hulbert40 | Partial | Complete | Complete | Complete |

| Andrewes, Hulbert44 | Partial | Complete | Complete | Complete |

| Anestis, Silva33 | Partial | Partial | Absent | Partial |

| Armey, Crowther31 | Complete | Complete | Complete | Complete |

| Coifman, Berenson41 | Complete | Complete | Complete | Complete |

| Crowe, Daly54 | Complete | Complete | Absent | Complete |

| Depp, Moore26 | Complete | Complete | Partial | Complete |

| Depp, Moore28 | Partial | Partial | Partial | Complete |

| Fitzpatrick, Kranzler56 | Complete | Partial | Partial | Partial |

| Hadzic, Spangenberg51 | Partial | Complete | Partial | Absent |

| Hallensleben, Glaesmer55 | Partial | Partial | Complete | Partial |

| Hallensleben, Spangenberg48 | Complete | Complete | Partial | Partial |

| Hochard, Ashcroft66 | Partial | Complete | Partial | Partial |

| Hochard, Heym67 | Complete | Complete | Partial | Complete |

| Houben, Claes42 | Complete | Complete | Partial | Absent |

| Hughes, King86 | Complete | Complete | Complete | Complete |

| Humber, Emsley57 | Partial | Partial | Partial | Complete |

| Kleiman, Turner62 | Partial | Complete | Complete | Complete |

| Kranzler, Fehling62 | Complete | Complete | Complete | Complete |

| Lavender, De Young34 | Complete | Complete | Complete | Complete |

| Lavender, Wonderlich35 | Complete | Complete | Complete | Complete |

| Law, Furr47 | Partial | Partial | Partial | Complete |

| Links, Eynan27 | Complete | Complete | Complete | Partial |

| Littlewood, Kyle69 | Complete | Partial | Complete | Complete |

| Muehlenkamp, Engel36 | Partial | Complete | Absent | Partial |

| Nisenbaum, Links87 | Complete | Partial | Partial | Complete |

| Nock, Prinstein29 | Partial | Complete | Complete | Complete |

| Oppenheimer, Silk59 | Complete | Complete | Complete | Partial |

| Palmier-Claus, Taylor50 | Complete | Complete | Partial | Complete |

| Pearson, Pisetsky49 | Complete | Complete | Partial | Partial |

| Santangelo, Koenig60 | Complete | Partial | Partial | Partial |

| Selby, Franklin23 | Complete | Complete | Complete | Complete |

| Selby and Joiner24 | Complete | Complete | Complete | Complete |

| Selby, Nock64 | Complete | Complete | Complete | Partial |

| Snir, Rafaeli46 | Complete | Complete | Partial | Complete |

| Spangenberg, Glaesmer63 | Complete | Complete | Partial | Complete |

| Tian, Yang25 | Partial | Complete | Absent | Complete |

| Turner, Yiu38 | Complete | Complete | Absent | Complete |

| Turner, Cobb37 | Complete | Complete | Partial | Partial |

| Turner, Wakefield22 | Complete | Partial | Complete | Absent |

| Vansteelandt, Houben45 | Complete | Partial | Partial | Partial |

| Victor, Scott43 | Complete | Complete | Partial | Partial |

| Woosley, Lichstein68 | Partial | Partial | Partial | Complete |

| Wright, Hallquist58 | Partial | Complete | Absent | Partial |

| Zaki, Coifman65 | Complete | Complete | Absent | Absent |

| Rizk, Choo52 | Complete | Complete | Absent | Partial |

| Selby, Kranzler30 | Complete | Partial | Complete | Complete |

| Vine, Victor53 | Complete | Partial | Absent | Complete |

| Did not/partially meet criteria, studies (%) | 16 (33%) | 15 (31%) | 30 (61%) | 20 (41%) |

a: explain rationale for the sampling design (e.g., random, event-based), explain rationale for sampling density (e.g., assessments per day) and scheduling (i.e., when the assessments are scheduled), and justify sample size; b: report full text of items, rating time frames (e.g., justify why sampling only certain hours of the day or night is appropriate), and report psychometric properties of items in the current EMA study (between- and within-subject), as well as the origin of the items; c: define valid and missing data (for participants broadly, and specific to individual EMA reports) report descriptive analyses regarding valid data (e.g., mean per person, range, % participants above and below 80% threshold), and describe the procedures used to enhance compliance and participation (e.g., remuneration schedule, participant training); d: Describe levels of analysis (momentary, day, person) explain how time is taken into account in analyses; specify and justify choices of random versus fixed effects in models; describe analytic modeling used as well as statistical software used. Describe the final data set: number of reports (total; person average; group average), days in study and retention rates, and rates of delayed or suspended responding (if applicable).

Key findings

Studies on suicide and self-harm were summarised into five sections. Table 4 provides a summary of all study findings. The sections were based on the measurements of each study which are presented in the next sections. We generated each section to distinguish the studies based on the types of factors measured by the EMA or any of the baseline assessments and target population.

Table 4.

Predictors of daily suicide and self-harm, and daily psychological and behavioural correlates of daily suicide and self-harm.

| References | Comparison groups | Study findings |

|---|---|---|

| Ammerman, Olino39 | No group | - Daily ‘urges to hurt oneself’, ‘urges of being impulsive’, and ‘distress tolerance level’ were predictors of the occurrence of daily NSSI in people with depressive disorder and borderline personality disorder. - Daily PA and ‘aggressive urges’ were not predictors of the occurrence of daily NSSI in people with depressive disorder and borderline personality disorder. |

| Andrewes, Hulbert40 | G1: NSSI G2: Self-injurious thoughts G2: Neither NSSI or self-injurious thoughts |

- Higher daily ‘distress levels’ and ‘negative complex emotions’ were significantly associated with young people diagnosed with borderline personality disorder and who engaged in daily NSSI and SIT than young people diagnosed with borderline personality disorder and who did not engage in daily NSSI and SIT. - Higher daily ‘conflicting emotions’ were not significantly associated with young people diagnosed with borderline personality disorder and who engaged with daily NSSI and SIT than young people diagnosed with borderline personality disorder and who did not engage in daily NSSI and SIT. - Lower ‘acceptance of negative emotions’ was significantly associated with increases in ‘negative complex emotions’ from the time prior to the occurrence of SIT and NSSI during the day. |

| Andrewes, Hulbert44 | G1: NSSI G2: No NSSI |

- Daily PA and NA were significantly associated with young people with borderline personality disorder and who engaged in daily NSSI than young people with borderline personality disorder and who did not engage in daily NSSI. - Changes in daily PA and NA were significantly associated with the thoughts of the timing of daily NSSI. |

| Anestis, Silva33 | No groups | - Daily levels of ‘affective liability’ and ‘previous suicide attempts’ were significantly associated with NSSI episodes in people with bulimia nervosa. |

| Armey, Crowther31 | G1: NSSI G2: No NSSI |

- Daily NA (guilt, anger, and loathing) were significantly associated with college students experiencing daily NSSI episodes than college students who did not experience daily NSSI episodes. - Daily NA increases prior to NSSI episodes, peaked during NSSI episode, and then faded after an NSSI episode in college students who engaged in daily NSSI behaviours. |

| Coifman, Berenson41 | G1: borderline personality disorder G2: healthy control |

- Daily ‘relational experiences’ were significantly associated with daily NSSI (impulsive behaviours) during high stress in people with borderline personality disorder than people without borderline personality disorder (healthy control). - Daily ‘affective experiences’ were significantly associated with daily NSSI (impulsive behaviours) during low stress in people with borderline personality disorder than people without borderline personality disorder (healthy control). - The heightened polarity of daily ‘affective and relational experiences’ were significantly associated with daily NSSI (impulsive behaviours) in people with borderline personality disorder than people without borderline personality disorder (healthy control). |

| Crowe, Daly54 | G1: major depression disorder G2: healthy control |

- People with MDD showed increases in daily ‘affect’ and ‘suicidality’ than people without MDD (healthy control) - People with MDD showed higher fluctuations in daily ‘suicidality’ than people without MDD (healthy control) |

| Depp, Moore26 | G1: Suicidal ideation G2: No or minimal suicidal ideation |

- Daily ‘time spent alone’ were significantly associated with people with suicidal ideation. - Daily ‘social interactions’ and ‘being with others’ were significantly associated with greater ‘happiness’ and less NA in people with or without suicidal ideation. - Daily ‘time spent alone’, and greater NA and lower PA were significantly associated with people with suicidal ideation. No significant difference in ‘time spent alone’ in a day between people with suicidal ideation and people without suicidal ideation. - Daily ‘social behaviour on affect’ were not significantly associated with people with suicidal ideation. - Daily ‘social interactions’ were not significantly associated with people with suicidal ideation. |

| Depp, Moore28 | No groups | - Higher daily ‘impulsivity’ were significantly associated with more ‘severe manic symptoms’ and elevated ‘suicide risk’ at baseline in outpatients with bipolar. - Daily ‘impulsivity’ were significantly associated with worse ‘cognitive function’, greater ‘manic symptoms’, and greater ‘suicide risk’ at baseline in outpatients with bipolar. - Daily ‘happiness’ was not significantly associated with ‘suicide risk’ at baseline. |

| Fitzpatrick, Kranzler56 | G1: NSSI duration G2: NSSI intensity/frequency |

- Greater daily ‘NSSI intensity’ were predictors of greater daily ‘NSSI engagement’ in people who engaged in NSSI. - Greater daily ‘NSSI intensity’ were predictors of greater daily ‘NSSI frequency’ in people who experience a longer duration of ‘NSSI thoughts’ than people who experience a shorter duration of ‘NSSI thoughts’. - Greater daily ‘NSSI intensity’ were predictors of greater daily number of ‘NSSI methods’ in people who experience a longer duration of ‘NSSI thoughts’. - Greater daily ‘NSSI intensity’ were predictors of greater likelihood of ‘engaging in cutting’ in people who experience a longer duration of ‘NSSI thoughts’. - The presence of ‘NSSI thoughts’ were predictors of greater daily ‘NSSI frequency’; however, the presence of ‘NSSI thoughts’ were not predictors of ‘NSSI duration’, ‘engagement of cutting’, and ‘engagement of punching’ in people who engaged in NSSI. - Alternative behaviours to NSSI include People mostly engagement with activities such as listening to music, talking to someone, doing homework, and sleeping. People mostly did not engage with activities such as using internet support groups, relaxation, changing NSSI thoughts, and going out. |

| Hadzic, Spangenberg51 | No groups | - Daily ‘suicide ideation’ were not significantly associated with ‘trait impulsivity’, ‘thwarted belongingness’ and ‘perceived burdensomeness’ at baseline in psychiatric patients with unipolar depressive disorder and suicide ideation. - Daily ‘passive suicide ideation’ were significantly associated with ‘trait impulsivity’ at baseline in psychiatry patients with unipolar depressive disorder and suicide ideation. - Daily ‘passive suicide ideation’ were not significantly associated with daily ‘active suicide ideation’ or daily ‘suicide intention’ in psychiatry patients with unipolar depressive disorder and suicide ideation. - Daily ‘suicide intention’ was not significantly associated with ‘trait impulsivity (attention and non-planning)’ at baseline in psychiatry patients with unipolar depressive disorder and suicide ideation. - Daily ‘suicide ideation’ were significantly associated with ‘trait impulsivity’ at baseline, but not daily ‘active suicide ideation’. - Daily ‘suicide ideation’ were significantly associated with ‘trait impulsivity (motor aspect)’ at baseline, not daily ‘active suicide ideation’. |

| Hallensleben, Spangenberg48 | No groups | - Daily ‘suicide intent’ were not significantly associated with the severity of ‘depression’ at baseline in inpatients with unipolar affective disorder. - Daily ‘suicide intent’ were not significantly associated with the number of ‘depressive episodes’ at baseline in inpatients with unipolar affective disorder. - Daily ‘suicide intent’ were not significantly associated with different aspects of ‘suicidality’ at baseline in inpatients with unipolar affective disorder. |

| Hallensleben, Glaesmer55 | G1: passive suicidal ideation G2: active suicidal ideation |

- Daily ‘depression’, ‘hopelessness’, ‘perceived burdensomeness’, and ‘thwarted belongingness’ was significantly associated with daily ‘passive suicidal ideations’ in people with unipolar depression. - Earlier daily ‘hopelessness’, ‘perceived burdensomeness’ and ‘passive suicidal ideation’ were predictors of later daily ‘passive suicidal ideations’ in people with unipolar depression. - Daily ‘depression’, ‘hopelessness’, ‘perceived burdensomeness’, and ‘thwarted belongingness’ was significantly associated with ‘active suicidal ideation’ in people with unipolar depression. - Daily ‘thwarted belongingness’ did not predict ‘active suicidal ideation’ in people with unipolar depression. |

| Hochard, Ashcroft66 | G1: Self-harm G2: Healthy control |

- Daily ‘powerlessness to change behaviour’ (nightmare) was significantly associated with an increased likelihood of ‘lifetime self-harm engagement’ at baseline in university students who engaged in self-harm than university students who did not engage in self-harm. - Daily ‘financial hardship’ (nightmare) was significantly associated with a reduced likelihood of ‘lifetime self-harm engagement’ at baseline in university students who engaged in self-harm than university students who did not engage in self-harm. - Daily ‘powerlessness to change behaviour’ (nightmare) was significantly associated with an increased likelihood of a ‘history of self-harm’ at baseline in university students who engaged in self-harm than university students who did not engage in self-harm. - Daily ‘financial hardship’ (nightmare) was significantly associated with a reduced likelihood of a ‘history of self-harm’ at baseline in university students who engaged in self-harm than university students who did not engage in self-harm. - Triggering of a self-harm phenomenon following the nightmare indicated that no themes were significantly associated with a self-harm phenomenon on the morning following a nightmare. |

| Hochard, Heym67 | No groups | - Daily ‘nightmares’ were predictors of post-sleep ‘self-harm behaviours and thoughts’, ‘beyond depressive’ symptoms, pre-sleep NA, and post-sleep NA in university students. - Daily ‘nightmares’ significantly increase the risks of experiencing post-sleep ‘self-harm behaviours and thoughts’ in university students. - Pre-sleep ‘self-harm behaviours and thoughts’ were not predictors of the occurrences of post-sleep ‘self-harm behaviours and thoughts’, ‘beyond depressive’ symptoms, pre-sleep NA, and post-sleep NA in university students. - Pre-sleep ‘self-harm behaviours and thoughts’ were not predictors of daily ‘nightmares’, ‘beyond depressive’ symptoms, and pre-sleep NA in university students. - Daily ‘nightmares’ were significantly associated with increased post-sleep NA in university students. Specifically, post-sleep NA was significantly associated with increased risks of post-test self-harm. |

| Houben, Claes42 | No groups | - High daily ‘negative emotions’ were predictors of a high likelihood of daily NSSI in inpatients with borderline personality disorder. - High occurrence of daily NSSI in a certain period were predictors of an increase in daily ‘negative emotions’ and a decrease in daily ‘positive emotions’ in the same period in inpatients with borderline personality disorder. - A prolonged positive effect of daily NSSI followed by daily ‘negative emotions’ in inpatients with borderline personality disorder. |

| Hughes, King86 | No groups | - High daily ‘anxiety’ and ‘feeling overwhelmed’ were predictors of daily NSSI when daily Repeated Negative Thinking (RNT) was elevated in young people who self-injured. - Daily ‘negative affect, anxiety, and RNT’ were predictors of daily ‘NSSI thoughts intensity’ and ‘NSSI behaviour frequency.’ |

| Humber, Emsley57 | No groups | - Daily ‘anger’ was significantly associated with daily suicidal ideation and daily ‘psychological distress’ in adults from a penitentiary facility. - High daily ‘externalised anger’ were predictors of daily suicidal ideation in adults from a penitentiary facility. - High daily ‘internalised anger’ was significantly associated with daily ‘psychological distress’ in adults from a penitentiary facility. - Daily ‘anger’ were predictors of daily ‘externalised anger’ and ‘ social psychological distress’ in adults from a penitentiary facility. - There was no significant association between suicidal ideation and ‘psychological distress’ in adults from a penitentiary facility from one-time point to the next time point. - High daily ‘internalised anger’ was significantly associated with daily ‘thoughts of wanting to live’ in adults from a penitentiary facility from one-time point to the next time point. |

| Kleiman, Turner62 | No groups | - Risk factors, such as hopelessness, burdensome, and loneliness, were significantly associated with daily suicidal ideation in both studies on people who attempted suicide or have experienced suicidal ideation. - Changes in ‘hopelessness’ and ‘burdensomeness’ were significantly associated with daily suicidal ideation in people who were part of an online community, and who attempted suicide or have experienced suicidal ideation. - Changes in ‘hopelessness’ were significantly associated with daily suicidal ideations in inpatients who attempted suicide or have experienced suicidal ideation. |

| Kranzler, Fehling62 | No groups | - Daily levels of ‘negative emotions’ and ‘positive emotions’ were predictors of daily NSSI thoughts in young people with NSSI thoughts. - Daily levels of ‘negative emotions’ and ‘positive emotions’ were predictors of daily NSSI behaviours in young people who engaged in NSSI behaviours. - Decreases of daily ‘negative emotions’ (reduced high-arousal of negative emotions) were significantly associated with increases of daily ‘positive emotions’ (increased low-arousal of positive emotions) in young people with NSSI thoughts and who engaged in NSSI behaviours. |

| Law, Furr47 | G1: Intensive suicide assessment G2: Control assessment group |

- There were no significant differences of daily ‘suicide attempt’, ‘suicidal ideation’, and ‘self-harm’ between people who received borderline personality disorder momentary assessments and people who received borderline personality disorder and momentary assessments that monitored suicide. |

| Lavender, De Young34 | No groups | - Stable and high daily ‘anxiety’ was positively associated with self-harm (including ‘personality traits’) at baseline in people with eating disorders. - Stable and low daily ‘anxiety’ was negatively associated with self-harm (including ‘personality traits’) at baseline in people with eating disorders. |

| Lavender, Wonderlich35 | No groups | - Daily ‘unregulated subtype of AN’ was significantly associated with self-harm at baseline in people with eating disorders. |

| Links, Eynan27 | No groups | - The intensity of daily ‘mood’ was significantly associated with suicidal ideation and self-harm behaviours in outpatients with BPD. - Reactivity of daily ‘mood’ was significantly associated with suicidal ideation in outpatients with BPD. - The intensity of daily ‘negative mood’ was significantly associated with suicidal behaviours in the past year in outpatients with BPD. |

| Littlewood, Kyle69 | No groups | - Daily ‘subjective sleep time’ and ‘sleep quality’ significantly predicted daily ‘suicidal ideation’ the following day in people with suicide ideation. - Less daily ‘subjective and objective sleep time’ and poor ‘sleep quality’ were significantly associated with higher daily levels of ‘next-day suicide ideation’ in people with suicide ideation. - Daily ‘subjective and objective sleep efficiency’ were not significantly associated with daily ‘next-day suicide ideation’ in people with suicide ideation. - Daily ‘day-time suicide ideation’ were not significantly associated with daily ‘objective sleep activity’ in people with suicide ideation. - Daily poor ‘sleep quality’, and higher ‘pre-sleep entrapment’ were significantly associated with increased ‘awakening suicidal ideation’ in people with suicide ideation. - Daily ‘subjective and objective sleep time, efficiency, and sleep onset latency’ did not significantly associated with daily ‘pre-sleep entrapment’ and ‘awakening suicide ideation’ in people with suicide ideation. |

| Muehlenkamp, Engel36 | G1: NSSI G2: Non-NSSI |

- Daily NA significantly increased prior to a bulimia nervosa patient’s NSSI behaviour or act. - Daily PA significantly decreased prior to a bulimia nervosa patient’s NSSI behaviour or act. - Daily NA reached no significant change following after a bulimia nervosa patient’s NSSI behaviour or act. - Daily PA significantly increased following after a bulimia nervosa patient’s NSSI behaviour or act. |

| Nock, Prinstein29 | No groups | - Greater intensity of daily NSSI thoughts were predictors of daily NSSI behaviours in people with suicidal and NSSI thoughts. - Daily NSSI behaviours were significantly associated with shorter durations of daily NSSI thoughts in people with suicidal and NSSI thoughts. - Daily activities were not predictors of people’s suicidal and NSSI thoughts. - Daily experiences of ‘loneliness’ or ‘being alone’ were significate predictors of NSSI engagement in people with suicidal and NSSI thoughts. - Daily NSSI thoughts occurred in the context of feeling sad/worthless, overwhelmed, or scared/anxious. |

| Nisenbaum, Links87 | No groups | - Participants reporting moderate to severe sexual abuse and elevated suicide ideation at baseline were characterised by worsening moods from early morning up through the evening, with little or no relief. - Participants reporting mild sexual abuse and low suicide ideation reported improved mood throughout the day. |

| Oppenheimer, Silk59 | No groups | - Daily ‘negative social experience’ were significantly associated with ‘right insula brain activation’ and ‘suicide ideation’ at baseline in people with anxiety. - Daily ‘negative social experience’ was not significantly associated with ‘left insula brain activation’ and ‘suicide ideation’ at baseline in people with anxiety. - Daily ‘negative social experience’ was not significantly associated with ‘dorsal anterior cingulate cortex’ and ‘suicide ideation’ at baseline in people with anxiety. |

| Palmier-Claus, Taylor50 | No groups | - Daily NA were predictors of ‘suicidal severity’ and ‘suicidal frequency’ at baseline in people with ultra-high risk psychosis. - Daily PA were predictors of ‘suicidal frequency’ in people at baseline with ultra-high risk psychosis. - Daily PA were not predictors of ‘suicidal severity’ in people at baseline with ultra-high risk psychosis. |

| Pearson, Pisetsky49 | No groups | - Daily self-harm was not significantly associated with personality psychopathology outcomes (trait-level variables) for people diagnosed with bulimia nervosa. |

| Rizk, Choo52 | No groups | - Daily ‘suicide ideation (variability)’ were predictors of ‘affective lability’ at baseline; however, daily ‘suicide ideation (severity)’ were not predictors of ‘affective lability’ at baseline in people with borderline personality disorder. - Daily ‘suicide ideation (severity)’ were predictors of ‘affective lability’ at baseline in people with borderline personality disorder. This association was driven by ‘depressive severity’ and ‘impulsiveness’ at baseline. |

| Santangelo, Koenig60 | G1: NSSI G2: Healthy Control |

- Adolescents diagnosed with borderline personality disorder and who engaged with NSSI measured at baseline, significantly experienced less daily PA, and lower levels of ‘attachment to the mother and best friends’, than adolescents diagnosed with borderline personality disorder and who did not engage with NSSI measured at baseline. - Adolescents diagnosed with borderline personality disorder and who engaged with NSSI measured at baseline, significantly experienced greater daily ‘affective instability’, greater daily ‘interpersonal instability with mothers’, and greater daily ‘interpersonal instability with best friends’, than adolescents diagnosed with borderline personality disorder and who did not engage with NSSI measured at baseline. - Daily ‘affective instability’ and daily ‘interpersonal instability with best friends’ were positively correlated with BPD criteria measured at baseline in adolescents diagnosed with borderline personality disorder and who engaged with NSSI. |

| Selby, Franklin23 | G1: NSSI G2: Dysregulated non-NSSI |

- Daily ‘rumination instability’ was significantly associated with daily NSSI in people diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder, and a history of NSSI. - Daily ‘stable rumination’ were not predictors of daily NSSI in people in people diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder, and a history of NSSI. - Past ‘rumination instability’ were positive predictors of daily NSSI. However, future ‘rumination instability’ were not predictors of daily NSSI in people diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder, and a history of NSSI. |

| Selby and Joiner24 | G1: borderline personality disorder G2: no borderline personality disorder |

- Daily ‘lag-rumination’ were predictors of daily ‘dysregulated behaviours’ (NSSI and other behaviours), whereas low levels of daily ‘lag-negative emotions’ were not predictors of daily ‘dysregulated behaviours’ (NSSI and other behaviours). - Daily ‘lag-rumination’ and daily ‘lag-negative emotions’ were predictors of daily ‘dysregulated behaviours’ (NSSI and other behaviours). - People diagnosed with borderline personality disorder significantly reported more severity of daily ‘dysregulated behaviours’ (NSSI and other behaviours) than people who were not diagnosed with borderline personality disorder. |

| Selby, Nock64 | G1: Automatic positive reinforcement G2: No automatic positive reinforcement |

- People who experience automatic positive reinforcement significantly reported more daily NSSI behaviours than people who do not experience automatic positive reinforcement. - People who experience automatic positive reinforcement significantly reported more daily NSSI thoughts than people who do not experience automatic positive reinforcement. - There were no significant differences in the average intensity of NSSI thoughts or frequency of ‘suicidal thoughts’ between people who experience automatic positive reinforcement and people who do not experience automatic positive reinforcement. - People attempting to feel ‘pain and stimulation’ significantly experience elevated levels of daily NSSI behaviours than people who did not attempt to feel ‘pain and stimulation’. - People attempting to feel ‘satisfied during NSSI’ significantly reported less daily NSSI behaviours than people who did not attempt to feel ‘satisfied during NSSI’. |

| Selby, Kranzler30 | No groups | - Adolescents who experience NSSI were likely to report more daily ‘NSSI episodes’ when they reported no daily ‘physical pain’ during at least one ‘NSSI episode’. - Daily ‘physical pain’ onset during at least one ‘NSSI episode’ were not predictors of daily ‘NSSI episodes’ and were not predictors of daily ‘physical pain’ offset during at least one ‘NSSI episode’ in Adolescents who experience NSSI. - Adolescents who experience NSSI reported greater daily ‘negative emotions’ at the start of daily ‘NSSI episodes’; however, they reported less daily ‘physical pain’ onset during ‘NSSI episodes’. |

| Snir, Rafaeli46 | G1: Borderline personality disorder G2: Avoidant personality disorder G3: Healthy control |

- People diagnosed with borderline personality disorder measured at baseline significantly showed more frequent daily ‘NSSI episodes’ than people in the healthy control group. - There was no significant difference in daily ‘NSSI episodes’ between people diagnosed with avoidant personality disorder measured at baseline, and people diagnosed with borderline personality disorder measured at baseline and people in the healthy control group. - People diagnosed with borderline personality disorder measured at baseline reported significantly higher levels of daily ‘NSSI urges ‘than people in the healthy control group. - There were no significant differences in daily ‘NSSI urges’ between people diagnosed with avoidant personality disorder measured at baseline, and people diagnosed with borderline personality disorder measured at baseline and people in the healthy control group. |

| Spangenberg, Glaesmer63 | No groups | - People with a history of suicide attempt reported lower ‘pain tolerance’ and similar levels of ‘fearlessness about death’ and ‘perceived capacity for suicide’ than people without a history of suicide attempts. - Daily ‘active suicidal ideation’ were significantly associated with higher daily ‘perceived capacity for suicide’ in people diagnosed with depression. - Daily ‘active suicidal ideation’ were not significantly associated with ‘fearlessness about death’ or ‘pain tolerance’. |

| Tian, Yang25 | G1: Suicide ideation G2: Non-suicide ideation |

- Full-time workers with ‘suicidal ideation’ measured at baseline reported significantly lower intensity of daily PA than full-time workers without ‘suicidal ideation’. - Full-time workers with ‘suicidal ideation’ measured at baseline reported significantly lower trends of greater daily ‘affective instability’ (happiness, warmth/friendliness, and relaxation/calmness). |

| Turner, Yiu38 | No groups | - People with NSSI and eating disorder reported more ‘negative emotions’ prior to NSSI than fasting, binge eating, or purging behaviours prior to NSSI. - People with NSSI and eating disorder were more likely to act on ‘NSSI thoughts’ when preceded by ‘arguments or conflict with others’, and were less likely to act on ‘NSSI thoughts’ when preceded by ‘financial problems’. - People with NSSI and eating disorder were more likely to act on ‘NSSI thoughts’ when ‘felt rejected’ or ‘hurt immediately before NSSI thought’. - People with NSSI and eating disorder who are ‘fasting’ on days with NSSI were significantly associated with less ‘negative mood intensity’, less ‘agitation’, and less ‘fatigue’ in the evening. - People with NSSI and eating disorder reported greater ‘fatigue’ in the morning were significantly associated with daily ‘binge eating’ and ‘purging’. |

| Turner, Cobb37 | No groups | - Daily ‘interpersonal conflict’ were predictors of same-day NSSI urges, and were likely to engage in NSSI. - Daily ‘NSSI behaviours revealed to others’ were followed by an increase ‘ perceived social support’ the following day, but not reduced conflict. - Daily ‘perceived social support’ followed by ‘NSSI behaviour’ were positively associated with ‘NSSI urges’ in the next day. - Daily ‘perceived social support’ followed by ‘NSSI behaviour’ was associated with a greater likelihood of ‘NSSI behaviour’ the following day. |

| Turner, Wakefield22 | G1: NSSI G2: No NSSI |

- People with NSSI reported less frequent ‘contact with family members and friends’ in the day than people without NSSI, however people with NSSI reported more frequent contact with ‘romantic partners’ in the day. - People with NSSI reported less ‘perceived social support’ following and during ‘interactions with friends’ in the day than people without NSSI. - People with NSSI were less likely to seek support to cope with distress in the day, regardless of the level of daily NA. - There was a significant difference in daily contact with ‘family members’ and ‘romantic partners’ between people with NSSI and people without NSSI. |

| Vansteelandt, Houben45 | No groups | - Greater daily NA were significantly associated with people with borderline personality disorder and who participate in NSSI acts than people with borderline personality disorder and who did not participate in NSSI acts (between-individual analysis). - Greater variability of daily affect was significantly associated with people with borderline personality disorder and who participated in NSSI acts than people with borderline personality disorder and who did not participate in NSSI acts (within-individual analysis). - People with borderline personality disorder and who engaged in NSSI acts showed significantly more daily NA than people with borderline personality disorder and who did not engage in NSSI acts (between-individual and within-individual analysis). |

| Vine, Victor53 | No groups | - Daily ‘dissociations’ were significantly associated with ‘suicide risk’ at baseline in adolescents with borderline personality and disorder and a history of suicide ideation and attempt. - Daily ‘negative and positive affect’ and ‘co-occurring borderline personality symptoms’ at baseline in adolescents with borderline personality and disorder and a history of suicide ideation and attempt. - Daily ‘dissociations’ were significantly associated with ‘suicide risk’ at baseline only in adolescents girls (not adolescents boys) with borderline personality disorder and a history of suicide ideation and attempt. |

| Woosley, Lichstein68 | No groups | - People ‘insomnia complaints’ and daily ‘insomnia sleep patterns’ were predictors of ‘suicidal ideation’ measured at baseline. - People daily ‘insomnia sleep patterns’ was not significantly associated with ‘suicidal ideation’ measured at baseline. - People combined ‘insomnia complaints’ and daily ‘insomnia sleep pattern’ were predictors of ‘suicidal ideation’ measured at baseline. - People who complained about sleep (good or bad) were two times more likely to report ‘suicidal ideation’ than people who did not complain about sleep. - People who complained about poor sleep were no likely to endorse ‘suicidal ideation’ than people who did not complain about good sleep. |

| Wright, Hallquist58 | No groups | - Daily interpersonal positivity was negatively associated with self-harm, and violence towards others for one participant diagnosed with borderline personality disorder. - Daily NA was significantly associated with self-harm and violence towards others for one participant diagnosed with borderline personality disorder. - Self-harm was significantly associated with daily NA, daily low agreeableness, and low daily PA for one participant diagnosed with borderline personality disorder. |

| Zaki, Coifman65 | G1: Borderline personality disorders G2: Healthy control |

- High daily ‘rumination’ and high ‘differentiation of negative emotions’ were significantly associated with decrease ‘frequency of NSSI’ in people with borderline personality disorder. - High daily ‘rumination’ and low ‘differentiation of negative emotions’ were significantly associated with increase ‘frequency of NSSI’ in people with borderline personality disorder. - Daily ‘rumination’ and ‘frequency of NSSI’ were significantly associated with moderate ‘differentiation of negative emotions’ in people with borderline personality disorder. |

| Victor, Scott43 | G1: Internalising NA G2: Externalising NA |

- Daily ‘internalising NA’ was significantly associated with subsequent daily ‘NSSI urges’ and ‘suicide urges’ in young women with borderline personality disorder. - Daily ‘externalising NA’ was significantly associated with later daily ‘NSSI urges’ and ‘suicide urges’ in young women with borderline personality disorder. - Daily ‘rejection’ nor ‘criticism’ did not significantly predict ‘suicide urges’ in young women with borderline personality disorder. - Daily ‘rejection’ significantly predicted daily ‘NSSI urges’, however daily ‘criticism’ did not significantly predict ‘NSSI urges’ in young women with borderline personality disorder. - There were significant indirect effects of within-person increases in daily ‘rejection’ and ‘criticism’ on daily ‘NSSI urges’ and ‘suicide urges’ through changes in ‘internalising NA’. - There was a significant direct effect of daily ‘rejection’ on later daily ‘NSSI urges’. |

NSSI: non-suicidal self injury; SIT: self-injurious thoughts; UHR: ultra-high risk; NA: negative affect; PA: positive affect.

Daily affect and mood

Daily affect was assessed on people with a history of NSSI or suicide ideation. Several studies examined daily changes of NA and PA in relation to an individual’s history of suicide ideation or NSSI.25,26 They found greater daily NA and lower daily PA in people with a history of suicide ideation compared to those without a history of suicide ideation.25,26 In particular, the study by Depp, Moore 26 found greater NA and lower PA were linked to reports of time spent alone in people with suicide intention than people without suicide, whereas daily reports of being with others and social interactions were related to greater PA and lower NA in people with or without a history of suicide intention. Daily mood and emotions were also considered as specific measures when monitoring the daily affective experiences of individuals.

A range of emotions was found to be related to NSSI or suicidality, including impulsivity, anger, guilt, loneliness, worthlessness and anxiety. The study by Links, Eynan 27 found daily intensity and reactivity of mood was related to suicidal ideation in outpatients with BPD. Additionally, the association between more specific emotions, such as impulsivity, was linked to elevated suicide risk measured at baseline in a study on outpatients with bipolar disorder.28 However, neither study included a healthy control or comparison group. Moreover, specific populations were examined in some studies, such as young people and people with mental health problems.

Daily mood and emotions of young people were observed using EMA. Two studies found young people reported the occurrence of daily NSSI episodes in the context of feeling physical pain, sad/worthless, overwhelmed, or scared/anxious.29,30 Further, they also found NSSI thoughts were proximal predictors of NSSI behaviours. Only a few studies examining young people and college students found reports of daily negative and positive emotions predicted NSSI thoughts and behaviours.31,32 In particular, Armey, Crowther 31 found that NA was higher among those young people and college students who engaged with NSSI than those who did not.

People with mental health problems, such as eating disorders, were investigated in three EMA studies which found varied results on daily emotions and NSSI behaviours. All three studies did not include a comparison or a healthy control group. Daily affective lability and previous suicide attempts were linked to people with a diagnosis of bulimia nervosa and a history of NSSI episodes.33 Furthermore, people with eating disorders found daily reports of high anxiety was positively associated with self-harm, low anxiety was negatively associated with self-harm, and unregulated personality-based subtypes of anorexia nervosa was related to self-harm measured at baseline.34,35 Other mental disorders were also found. Those studies specifically examined daily affect and NSSI.

Daily mental health factors

The majority of studies examining participants with a concurrent, diagnosed mental disorder yielded mixed findings on reports of daily NSSI behaviours. One of two studies on eating disorders found individuals reported increased PA and decreased NA prior to NSSI behaviours on a concurrent day, while PA increased following after an individual’s NSSI act.36,37 Turner, Yiu 38 examined individuals diagnosed with disordered eating, and a history of NSSI found individuals reported more daily negative emotions prior to NSSI behaviour than fasting, binge eating or purging. They also found individuals diagnosed with disordered eating and a history of NSSI were more likely to act on NSSI thoughts on the same day when preceded by arguments with others, feeling rejected, or feeling hurt by others; however, they were less likely to act on NSSI thoughts when preceded by financial problems. Additionally, Ammerman, Olino 39 found daily urges to hurt oneself, urges of being impulsive, and low distress tolerance was predictive of daily NSSI occurrence reported by individuals with a diagnosis of BPD and depressive disorder.

Studies using EMA examining Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) found that on average individuals reported heightened day-to-day stress, negative complex emotions, and affective experiences in relation to increasing reports of daily NSSI behaviours.40–42 Furthermore, associations between daily internalising and externalising NA and daily NSSI and suicide urges were reported by women with BPD.43 When compared to a healthy control group, Coifman, Berenson 41 found individuals diagnosed with BPD reported greater polarity of day-to-day affective and relational experiences (e.g. daily stress) which predicted increased reports of NSSI behaviours. Moreover, a couple of studies found greater NA and lower PA reported by individuals with BPD and who participated in NSSI acts than individuals who did not participate in NSSI behaviours.44,45

Certain psychopathology predictors were considered in several studies using EMA. Majority of the studies examining psychiatric patients focused on psychopathology factors as predictors of daily suicide and self-harm. For instance, people diagnosed with BPD at baseline reported more frequent daily NSSI episodes and NSSI urges than healthy control; however, there were no differences between people diagnosed with Avoidant Personality Disorder (APD), people with BPD or healthy controls.46 It was also found people who received daily assessments of suicidality and BPD did not have more frequent daily reports of suicide attempt, suicide ideation, and self-harm than people who only received BPD assessments.47 Furthermore, a couple of studies examining people with major depressive disorder or bulimia nervosa found psychopathology outcomes were not associated with daily reports of suicide intention or self-harm.48,49

Suicide-related predictors

Distinct suicide-related factors were observed in studies using EMA that investigated populations with concurrent mental disorders. In several studies on individuals diagnosed with mental disorders, daily NA and PA were associated with severity and frequency of suicidality measured at baseline in people with psychosis. Among individuals diagnosed with major depression and bipolar, daily NA was associated with suicidal ideation measured at baseline.50 Furthermore, people diagnosed with unipolar depression and suicide ideation reported links between daily suicide ideation and trait impulsivity.51 Similarly, daily suicide ideation predicted affective lability at baseline in individuals with BPD,52 and associations between daily dissociations and suicide risks measured at baseline in adolescent girls with BPD.53 Crowe, Daly 54 was one study that found people with MDD reported greater increases of daily affect and higher fluctuations in suicidality than people without MDD. Similarly, the study by Hallensleben, Glaesmer 55 found daily depressive symptoms, hopelessness, and perceived burdensomeness were significantly associated with passive and active suicidal ideation in people diagnosed with unipolar depression. Further, earlier daily hopelessness, perceived burdensomeness, and passive suicidal ideation were associated with active suicidal ideation.

Daily NSSI intensity, frequency, and engagement were observed within individuals who engaged in self-injury behaviours. Fitzpatrick, Kranzler 56 recently found greater daily NSSI intensity predicted greater daily NSSI engagement. Furthermore, higher reports of daily NSSI intensity predicted greater daily NSSI frequency, and more reports of NSSI methods among people who experience a longer duration of NSSI thoughts. The presence of NSSI thoughts during the day predicted greater daily NSSI frequency; however, it did not predict NSSI methods, such as cutting and punching. The study also found people engaged with alternative behaviours to NSSI, including listening music, doing homework, sleep, and talking to others, which may suggest that individuals who engage in self-injury will attempt to seek and talk to others as alternatives to performing self-harm.

Daily social factors

A range of daily interpersonal interactions and violence and suicidal ideation were investigated in EMA studies on suicidal thoughts and behaviours. Studies examining reports of daily NSSI behaviours and thoughts found interpersonal interaction variables, including interpersonal conflict, were predictive of concurrent reports of NSSI thoughts and NSSI engagement.29,38 Specifically, there was a focus on daily suicidal thoughts and negative interpersonal conflicts, such as interpersonal violence, anger, and aggression. One study found an association between daily reports of anger and daily reports of suicidal ideation and psychological distress in adults in a penitentiary facility.57 A case study by Wright, Hallquist 58 found links between the occurrence of self-harm and increased reports of daily interpersonal violence, and low agreeableness, among individual participants diagnosed with BPD. Lastly, Victor, Scott 43 found daily experiences of interpersonal rejection and criticism did not significantly predict subsequent suicide urges; however, there were significant within-person indirect effects through changes in ‘internalising NA’. Additionally, interpersonal rejection independently predicted other NSSI urges. Comparable findings were found in people diagnosed with anxiety, specifically relating to daily negative social interactions and suicide ideation measured at baseline.59