Abstract

Objective: Many older adults who are cognitively intact experience financial exploitation (FE), and the reasons for this are poorly understood. Methods: Data were gathered from 37 older adults (M age = 69.51, M education = 15.89, 62% female) from the Finance, Cognition, and Health in Elders Study (FINCHES). Twenty-four older adults who self-reported FE were demographically-matched according to age, education, race, and MoCA performance to thirteen older adults who denied experiencing FE. Participants completed the Tilburg Frailty Inventory. Results: FE participants reported greater total frailty (t = 2.06, p = .04) when compared to non-FE participants. Post-hoc analyses revealed that FE participants endorsed greater physical frailty (U = 89, p = .03), specifically poorer sensory functioning (hearing and vision). Discussion: Findings suggest frailty is associated with FE in old age and may represent a target for intervention programs for the financial wellbeing of older adults.

Keywords: Abuse/neglect, cognition, frailty

Introduction

Financial exploitation (FE) is the most common form of elder abuse and is estimated to cost older adults up to 36 billion dollars (True Link Financial, 2015) annually. Since the number of adults over the age of 65 is expected to double between 2012 and 2050 (Ortman et al., 2014), FE of older adults poses a tremendous public health concern. Previous investigations have suggested that cognitive impairment is one the most common factors associated with FE in old age (Han et al., 2016). However, older adults without apparent cognitive impairment are financially exploited, and the underlying mechanisms for FE in older adults without significant cognitive impairment remain poorly understood.

One such factor that may be associated with FE in old age is frailty. Frailty is a multidimensional construct characterized by a state of vulnerability and an age-related reduction in resistance to stressors (Rodriguez-Manas et al., 2013). Frailty is described in physical terms, or in reference to the accumulation of health-related deficits and disorders, and has been associated with negative health outcomes such as hospitalization, falls, lower quality of life, disability, and premature death (Gobbens et al., 2017). One study previously associated frailty with elder abuse in a group of community-dwelling older adults in Mexico City, though links to financial abuse were nonsignificant after accounting for confounders (Torres-Castro et al., 2018). There have been few, if any, studies focused specifically on frailty and FE. Here, we build upon previous findings from our Finance, Cognition, and Health in Elders Study (FINCHES) and examine the hypothesis that older non-demented adults who endorsed a past experience of FE would report higher rates of frailty than demographically-matched older adults.

Methods

Participants

Thirty-seven older adults aged 50 or older were recruited in the greater Los Angeles area and were screened at two time points for eligibility: prior to study enrollment via phone screen, and on the day of their evaluation using the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA). Participants were excluded if they endorsed known signs of cognitive impairment/diagnosis of dementia, neurological or psychiatric illness, or current problems with drugs and alcohol. Those who scored 23 or below on the MoCA were excused from further participation. All study procedures were approved by the University of Southern California Institutional Review Board (IRB; HS-16-00902). Consent to participate was documented following IRB guidelines.

To determine group assignment, participants were asked: (1) “Do you feel you have been taken advantage of financially?” and (2) “Does someone you know feel that you have been taken advantage of financially?” If a participant endorsed either question, they were included in the perceived FE group. Participants who denied both questions were placed in the perceived non-financially exploited (non-FE) group. These questions were designed to allow for the capture of a wide range of perceived FE experiences in regards to perpetrators involved, methods employed, and amounts lost. This approach, therefore, allowed for the capture of instances that qualify under the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s definitions for financial exploitation and also those that go beyond those definitions. We have applied this approach in previously published work (Weissberger et al., 2019).

Frailty Measure

Frailty was assessed with the Tilburg Frailty Indicator (TFI; Gobbens et al., 2017). The self-report questionnaire yields physical, psychological, and social frailty subscale scores, along with a total frailty score based on the composite (Gobbens et al., 2017). The physical subscale includes questions regarding feeling physically healthy, losing weight, difficulty in walking or balance, poor hearing or vision, lack of strength in hands, and physical tiredness. The psychological subscale asks about problems with memory, feeling down, nervous, or anxious during the previous month, and ability to cope with problems. Finally, the social frailty subscale asks if the respondent lives alone, misses having people around them, and whether they receive enough support from other people.

Statistical Analyses

Perceived FE older adults were compared to non-FE older adults on the TFI. Continuous variables were assessed for normality and outliers. Independent t-tests or Mann-Whitney tests for non-normally distributed variables were run to examine group differences across demographic variables, TFI total frailty scores, and TFI subscale scores. We ran exploratory post-hoc analyses to examine differences between groups across the individual items within the TFI using Fisher’s Exact Tests.

Results

Participant Demographics

Twenty-four of the 37 (64.8%) participants responded “Yes” to at least one of the two FE questions and were included in the perceived FE group. All of the 24 perceived FE older participants responded “Yes” to question 1, with 15 also responding “Yes” to question 2. Thirteen participants answered “No” to both questions and were included in the non-FE group. Participant characteristics and questionnaire scores are presented in Table 1. Participants did not significantly differ with regard to age, education, race/ethnicity, or total MoCA score, (all ps ≥ .75). Sex trended towards significance (p = .06). In regard to race and ethnicity, 17 perceived FE and nine non-FE identified as non-Hispanic White, one perceived FE and one non-FE identified as African American, four perceived FE and one non-FE identified as Asian, and one perceived FE chose not to identify race but identified as Costa Rican. One perceived FE and one non-FE chose not to indicate race or ethnicity. Participant characteristics and scores on the TFI are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant Demographic Characteristics and Response to TFI.

| Perceived FE (n = 24) |

Non-FE (n = 13) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | |

| Age | 69.04 | 11.78 | 70.38 | 13.45 |

| Education | 15.83 | 2.54 | 16.00 | 2.73 |

| Sex (%F) | 75% | – | 38% | – |

| Race/Ethnicity (% Non-Hispanic White)1 | 70% | – | 69% | – |

| MoCA | 27.83 | 1.40 | 27.77 | 2.04 |

| TFI Total Frailty* | 4.45 | 2.91 | 2.5 | 2.22 |

| Physical subscale* | 2.12 | 1.96 | 0.76 | 1.09 |

| Psychological subscale | 1.25 | 1.18 | 0.69 | 0.85 |

| Social subscale | 1.08 | .82 | 1.07 | 0.75 |

Note. TFI = Tilburg Frailty Inventory; Perceived FE = financially exploited; Non-FE = non-financially exploited; MoCA = Montreal Cognitive Assessment.

n = 1 perceived FE and one non-FE participant chose not to respond to race and ethnicity.

Statistically significant difference between groups (p < .05); independent t-test was used for Total Frailty; Mann-Whitney test was used for all subscales.

Frailty Subscales

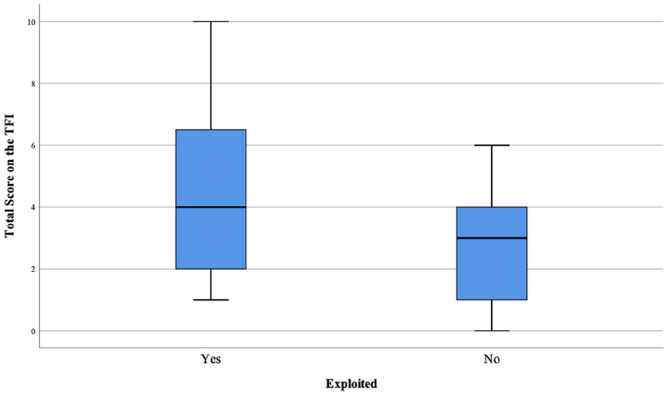

Older adults who endorsed FE reported significantly greater total frailty on the TFI (t[35] = 2.06, p = .046) and significantly greater physical frailty (Mann-Whitney test U = 89, p = .033) (Figure 1). There were no significant differences between perceived FE and non-FE participants on the psychological or social frailty subscales (all ps ≥ .20).

Figure 1.

Boxplot display of total scores on the 15-item Tilburg Frailty Inventory (TFI) for perceived financially exploited (n = 24) and non-exploited (n = 13) older adults.

Exploratory Analyses

Within the physical subscale, perceived FE participants more frequently endorsed item 5 (“poor hearing”; Fisher’s Exact Test p = .02; nine FE participants vs. none of the non-FE participants) and marginally more frequently on item 6 (“poor vision”; Fisher’s Exact Test p = .05; eleven FE participants vs. one non-FE participant). Amongst the FE older adults, ten participants denied both items, while six endorsed both poor hearing and poor vision, three uniquely endorsed poor hearing, and five endorsed only poor vision. Further exploration on an item related to depression within the psychological subscale of the TFI revealed that perceived FE participants reported more elevated symptoms of depression than the non FE participants. This pattern of findings is consistent with preliminary results from FINCHES exploring physical and mental health correlates of perceived FE (Weissberger et al., 2019).

Discussion

Individuals who self-reported a history of FE were compared to demographically matched individuals who denied a history of FE on responses to a measure examining physical, psychological, and social frailty. We found that older adults with perceived FE self-reported significantly greater total frailty than non-FE adults. In post-hoc analyses, FE participants endorsed greater physical frailty, and specifically, significantly poorer sensory functioning related to hearing, and marginally poorer vision.

Due to the cross-sectional nature of the present study, the directionality of the association between frailty and FE remains unclear. One possibility is that FE results in fewer financial resources to invest in hearing aids and/or glasses, thus resulting in poorer hearing and vision. A more likely possibility is that reduced sensory functioning may have contributed to a more vulnerable state of these persons compared to their peers. Individuals with reduced hearing/vision may miss critical details during interactions that might lead others with intact sensory functioning to question the veracity of a financial exchange. For example, the American Association of Retired Persons (AARP) cautions older adults against the “Grandparent Scam” wherein a distraught caller “who sort of sounds like your grand[child]” calls requesting financial assistance (Colino, 2018). The older adult is placed in a stressful circumstance requiring quick decision making, which would be all the more difficult if the individual has poor hearing and is already vulnerable to determining if it was indeed their grandchild. Similarly, older adults with vision loss may miss subtle visual cues that warn of potential fraud, for example being more likely to pick up a call from an unknown but familiar looking number, or responding to emails, letters, or text messages without picking up on salient visual cues that these could potentially be fraudulent.

Findings from the present study build upon the limited knowledgebase of factors that may contribute to FE. In contrast to findings from Torres-Castro et al. (2018), results from this demographically-matched FE and non-FE sample suggest that there is a relationship between physical frailty and FE. Possible reasons for the difference in findings could include different measures utilized in each study (TFI in the present study vs. the Frailty Phenotype used in Torres-Castro et al., 2018), and different study cohorts (Greater Los Angeles vs. Mexico City). Moreover, age-related hearing impairment (ARHI) and visual impairment, characteristics of physical frailty, are associated with cognitive decline and incident dementia (Uchida et al., 2019), which are established risk factors for FE. Interestingly, despite the absence of cognitive impairment in our population, we found that frailty was a distinguishing factor between FE and non-FE groups.

According to the Global Burden of Disease, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study (GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators, 2015), the second and third leading impairments by number of individuals affected were hearing loss and vision loss, respectively. The GBD estimated that over 90% of hearing loss was classified as age-related and, as people get older they’re at greater risk for age-related visual decline/ocular disease. Attention to changes in hearing and vision over time by family, friends, and medical providers, and implementation of compensatory strategies (e.g., hearing aids, vision correction) once called for may be critical in reducing an older adult’s susceptibility to FE.

There are several limitations to acknowledge. There is potential for self-selection bias that limits generalizability of our findings to a larger population as all participants were volunteers and were highly educated. Additionally, our perceived FE and non-FE group sample sizes are relatively small, thereby reducing our ability to generalize findings to a larger sample. Another notable limitation is that we utilized self-report for FE, which may result in inaccurate classification. Therefore, these findings may not be generalizable when attempting to replicate findings in a sample with confirmed FE. We also did not allow for elaboration on the severity, frequency, or potential for polyvictimization, all of which may result in differential relationships with frailty. Finally, participants were not asked if they wore hearing aids or used correction for their vision. Thus, the degree to which compensatory mechanisms might mediate sensory impairment and FE in this population cannot be determined.

The present study also has several notable strengths to acknowledge. We employed a well-established measure of frailty, and our research approach provided the opportunity to explore this relationship in a demographically-matched sample of cognitively healthy and racially-diverse older adults. Present findings suggest that poorer sensory functioning in hearing, and marginally in vision, is associated with perceived FE, and may represent a target for intervention programs aimed at protecting the financial wellbeing of older adults.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Caroline Nguyen for her help with data collection and management.

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: This study was approved by the institutional review board at the University of Southern California, approval number HS-16-00902. Written informed consent was obtained for all study participants.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Elder Justice Foundation and the Cathay Bank Foundation awarded to SDH, National Institute on Aging at the National Institutes of Health Grant T 32 AG 000037 to GHW, as well as the Department of Family Medicine of the University of Southern California.

ORCID iD: Jenna Axelrod  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4617-7939

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4617-7939

References

- Colino S. (2018, April 18). Beware of grandparent scam. https://www.aarp.org/money/scams-fraud/info-2018/grandparent-scam-scenarios.html

- GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 210 diseases and injuries, 1990-2015: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. The Lancet, 388(10053), 1545–1602. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobbens R., Schols J., van Assen M. (2017). Exploring the efficiency of the tilburg frailty indicator: A review. Clinical Interventions in Aging, 12, 1739–1752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han S. D., Boyle P. A., James B. D., Yu L., Bennett D. A. (2015). Mild cognitive impairment and susceptibility to scams in old age. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 49(3), 845–851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortman J. M., Velkoff V. A., Hogan H. (2014). An aging nation: The older population in the United States. United States Census Bureau. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Manas L., Féart C., Mann G., Viña J., Chattergi S., Chodzko-Zajko W., Harmand. M. C. C., Bergman H., Carcaillon L., Nicholson C., Scuteri A., Sinclair A., Pelaez M., Van der Cammen T., Beland F., Bickenbach J., Delamarche P., Ferrucci L., Fried L. P., Vega E. (2013). Searching for an operational definition of frailty: A Delphi method based consensus statement: the frailty operative definition-concensus conference project. The Journals of Gerontology, Series A, 68(1), 62–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Castro S., Szleif C., Parra-Rodríguesz L., Rosas-Carrasco O. (2018). Association between frailty and elder abuse in community-dwelling older adults in Mexico City. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 66(9), 1773–1778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- True Link Financial. (2015). The true link report on elder financial abuse. https://www.truelinkfinan-cial.com/research

- Uchida Y., Sugiura S., Nishita Y., Saji N., Sone M., Ueda H. (2019). Age-related hearing loss and cognitive decline – the potential mechanisms linking the two. Auris Nasus Larynx, 46(1), 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissberger G. H., Mosqueda L., Nguyen A. L., Samek A., Boyle P. A., Nguyen C. P., Han S. D. (2020). Physical and mental health correlates of perceived financial exploitation in older adults: Preliminary findings from the Finance, Cognition, and Health in Elders Study (FINCHES). Aging and Mental Health, 24(5), 740–746. 10.1080/13607863.2019.1571020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]