Abstract

Objectives

This study aims to ascertain whether the differences of prevalence and severity of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) are true or whether children are perceived and rated differently by parent and teacher informant assessments (INFAs) according to gender, age, and co‐occurring disorders, even at equal levels of latent ADHD traits.

Methods

Use of latent trait models (for binary responses) to evaluate measurement invariance in children with ADHD and their siblings from the International Multicenter ADHD Gene data.

Results

Substantial measurement noninvariance between parent and teacher INFAs was detected for seven out of nine inattention (IA) and six out of nine hyperactivity/impulsivity (HI) items; the correlations between parent and teacher INFAs for six IA and four HI items were not significantly different from zero, which suggests that parent and teacher INFAs are essentially rating different kinds of behaviours expressed in different settings, instead of measurement bias. However, age and gender did not affect substantially the endorsement probability of either IA or HI symptom criteria, regardless of INFA. For co‐occurring disorders, teacher INFA ratings were largely unaffected by co‐morbidity; conversely, parental endorsement of HI symptoms is substantially influenced by co‐occurring oppositional defiant disorder.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest general robustness of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders ADHD diagnostic items in relation to age and gender. Further research on classroom presentations is needed.

Keywords: ADHD, co‐occurring disorder, item factor analysis, measurement invariance, PACS

1. INTRODUCTION

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) 5 stipulates an age‐related threshold in the number of inattention (IA) and/or hyperactivity/impulsivity (HI) symptoms for an attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) diagnosis (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). The DSM5 symptom criteria remain largely unchanged from those of DSM‐IV. There is, however, no guidance or operationalised algorithm to steer clinicians' judgement on “developmental appropriateness” for a given age and gender. To establish a reliable clinical diagnosis of ADHD, it is recommended to gather information across settings. However, this introduces the issue of how best to integrate information from multiple settings, in particular, if co‐occurring conditions can further blur or affect the thresholds of diagnosis. Two common systems for diagnosis are used (Valo & Tannock, 2010): The ‘and‐rule' requires the item's endorsement by both parents and teachers, whereas the 'or‐rule' requires only the one or the other. The extent to which the above factors would influence the measurement of the traits—yielded by the “and” versus “or” rules—is not yet sufficiently known.

The effects of age, gender, informant assessment (INFA), and co‐occurring conditions on both the endorsement and severity rating of ADHD have been evaluated in a substantial body of studies. The majority of research examined the extent to which the total number of symptoms can vary according to these factors, with the ensuing effects on diagnostic prevalence. The detected differences across demographic groups in the total number of symptoms (score differences) have prompted some authors to propose adjusting the criteria threshold with respect to age (Biederman, Mick, & Faraone, 2000; Ramtekkar, Reiersen, Todorov, & Todd, 2010, among others) and gender (Amador, Forns, Guàrdia Olmos, & Peró, 2006; Monuteaux, Mick, Faraone, & Biederman, 2010; Rucklidge, 2010). Newcorn et al. (2001) identified significant differences in symptomatology according to co‐morbidity and gender.

The differences in the total scores (total number of symptoms) due to these factors are well documented in the literature. However, for an unbiased comparison of the total number of IA or HI symptoms across groups (for instance, gender or age groups) or conditions (for instance, type of INFA), we need first to establish that the probability of endorsing each symptom depends solely on the levels of IA or HI and that any group membership or condition does not bias the measurement. In psychometrics, this assessment is referred to as measurement invariance (MI) testing, within the framework of factor analysis (for instance, see Millsap, 2012), or as differential item functioning (for instance, Osterlind & Everson, 2009) within the item response theory context.

For instance, to compare boys' and girls' weights, one would first ensure that the same or an identical weighting scale is employed to measure both groups. Once the scale's MI across groups is established, then one can proceed with comparing the measurement scores. Only then, we expect that the same value (measurement) will occur on the weighting scale for two individuals with the same weight, regardless of their gender. In a similar manner, in this study, we seek to establish the invariance of the symptom criteria ratings in the measurement of the latent traits IA and HI across gender, age, INFA, and the algorithms to combine INFA's scores (i.e., “and” vs. “or” rules). If the measurement is invariant (unbiased), then two individuals with the same IA (or HI) levels should both have equal probabilities of endorsing the symptoms—regardless of their age, gender, co‐occurring diagnoses, and/or INFA. One can then proceed with testing the factor's effect on the total score, in a manner similar to that of a researcher who has first to ensure that the same weighting scale can be used for boys and girls and can then proceed with comparing the mean weight across genders. Therefore, there are two questions to be asked with respect to measurement. The first one refers to the objectivity of the measuring instrument (measurement invariance, MI), and the second refers to the differences in the scores (in psychometrics, differences in the scores of the traits referred to are termed the structural invariance).

Researchers in the field have previously used different assessment tools, statistical methods, and target populations, in their exploration of MI due to age and/or gender (Burns, Walsh, Gomez, & Hafetz, 2006; Caci, Morin, & Tran, 2016; Cogo‐Moreira et al., 2017; de Zeeuw, van Beijsterveldt, Lubke, Glasner, & Boomsma, 2015; Derks, Dolan, Hudziak, Neale, & Boomsma, 2007; Fumeaux et al., 2017; Geiser, Burns, & Servera, 2014; Gomez, 2012, 2013, 2016; Gomez & Vance, 2008; Morin, Tran, & Caci, 2016; Wiesner, Windle, Kanouse, Elliott, & Schuster, 2015) and invariance due to the informant (for instance, Burns, Desmul, Walsh, Silpakit, & Ussahawanitchakit, 2009; Gomez, 2007; King et al., 2016; Makransky & Bilenberg, 2014). Overall, the results of MI studies so far suggest that informant, age, gender, and culture have only small effects on ratings of ADHD symptoms. Nevertheless, it is of interest that a quantitative genetic twin study identified that parents and teachers report different psychopathological phenomena (Arnett, Pennington, Willcutt, DeFries, & Olson, 2015). Whether the discrepancies are real or arising from methodological differences across these studies remains untested.

To our knowledge, this work is novel in terms of assessing all these factors together, in the same sample, examining individual symptoms as well as the combination of information using the “and” versus “or” rules.

The objectives of this study are as follows:

Is the probability of endorsing a symptom dependent on parent or teacher assessment results? Do the different INFAs describe the same phenomena/behaviour?

Are some symptoms more likely to be endorsed due to a child's age, gender, and/or effects of co‐occurring diagnoses?

How is potential measurement noninvariance (MNI) reflected in combined‐information items, using “and” versus “or” rules?

2. METHODS

In 2003, the International Multicenter ADHD Gene (IMAGE) project funded by National Institute of Mental Health was launched in Europe. The IMAGE project is an international collaborative study that aims to identify genes that increase the risk for ADHD using Quantitative Trait Locus (QTL) linkage and association strategies. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from ethical review boards within each country, and informed consent was obtained for the use of the samples for analyses relating to the genetic investigation of ADHD. More details can be found in Chen et al. (2008), Müller et al. (2011a, 2011b), and Rosales et al. (2015).

2.1. Instruments

2.1.1. Parental Account of Clinical Symptoms

Parental Account of Clinical Symptoms (PACS; Chen & Taylor, 2006) has been used as the research diagnostic instrument for the probands and affected siblings. PACS is a standardised investigator‐based research diagnostic interview, designed to capture accurately and systematically the clinical phenotypes relating to hyperactivity, especially ADHD and hyperkinetic disorder along with other related childhood psychiatric disorders. The philosophy of PACS is very much similar to that of the Autism Diagnostic Interview, in which the interviewer endeavours to obtain an objective “fly on the wall” description of behaviour from the parents and establishes the ratings of severity and frequency. An algorithm was used to translate PACS ratings into DSM‐IV criteria (Curran, Newman, Taylor, & Asherson, 2000). In the inattentive behaviour section, all the DSM‐IV criteria exploring IA are reviewed. In the HI section of PACS, behaviour is rated in different day‐to‐day situation using behavioural counts. The structure and administration techniques of PACS have been designed to minimise opportunities for introducing responders' and raters' bias. Inter‐rater reliability has been reported as adequate in several samples, and reliability checks were maintained during the project.

2.1.2. Conners Teacher Rating Scale: Revised‐Long

This is a validated and widely used questionnaire in the field of ADHD (Collett, Ohan, & Myers, 2003) based on DSM‐IV, with an important research base. It is also commonly used in routine clinical practice.

2.1.3. Informant Assessment

Parents and teachers report on the presence or absence of a symptom, using PACS and Conners, respectively. National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines regard a detailed parental interview and a teacher rating as the key measures; PACS is a standardised and quantified parent interview; Conners scales are widely used and can be seen as the field standard. Therefore, our invariance evaluation incorporates not only any rater differences but also the scale (assessment medium) differences. Hence, our invariance evaluation does not separate between the variability due to the informant and the INFA tool employed. Therefore, our focus is not at the properties of a certain assessment tool but on the measurement outcome itself. That is, with the cost of not being able to separate the effect of the role (parent/teacher) from the effect of the corresponding technical tool, we achieve measuring potential bias at the final “symptom present/symptom absent” judgements made by each type of informant using the best tool available in each case. All other types of invariance have been conducted twice (per informant and therefore per assessment tool), and therefore, there are separate reports for PACS and Conners and inevitably separate reports for parents and teachers. This is also consistent with the ADHD diagnostic algorithm used in the IMAGE project where items from PACS completed by parents and teacher Conners information are combined.

2.1.4. Hypescheme

The Hypescheme (Curran et al., 2000) was used to yield a categorical diagnosis of ADHD and co‐morbid disorders. The Hypescheme is an operational criteria checklist and minimum dataset for the research diagnoses of ADHD. The full algorithm is available on request; it follows the criteria and instructions of (American Psychiatric Association, 2000).

2.2. Participants

All children (probands and siblings) were aged 5 to 17 years, had an IQ ≥ 70, and were of European Caucasian descent. Probands were recruited when referred for psychiatric evaluation aged 5 to 17, had at least one sibling, received an expert clinician's diagnosis of ADHD, and met Hypescheme criteria. There was access to at least one biological parent for DNA collection. Exclusion criteria for probands and siblings include IQ below 70, of non‐European Caucasian descent, free of other brain disorders, and any genetic or medical disorder associated with externalising behaviours that might mimic ADHD.

2.3. Statistical analyses

2.3.1. Item factor analysis model

Factor analysis is the statistical tool that allows the identification and measurement of one or more latent traits (symptom dimensions and factors) from a set of observed variables (indicators, symptoms, and items). In the current work, the indicators are binary (presence/absence of a symptom), and therefore, we used the item factor analysis (IFA) model for categorical data (Mislevy, 1986; Muthén, 1989a; Wirth & Edwards, 2007). The IFA model is summarised as follows:

| (1) |

where Φ −1 stands for the probit linki function, Pr(Y i = 1 | θ) is the probability of the symptom i to be present conditional on the latent trait θ (here, either IA or HI), and τ i, λ i are the threshold and the loading of the item Y i, respectively.

The threshold parameter corresponds to the severity of a symptom (location or difficulty parameter). The smaller the threshold parameter, the more easily a symptom is endorsed (less difficult, less severe); the loading parameter parallels the change in the probability of a positive response (symptom endorsement) as the level of the trait changes (slope or discrimination parameter). The larger the loading parameter, the more related to the latent continuum a symptom is (the more discriminative). The model (1) suggests that the item probability depends both on the items' characteristics (τ i, λi) and on the distribution of the individuals' latent trait (θ). Note that the threshold of the item analysis model equals minus the difficulty (−τ i = a i) parameter of the analogue item response theory, and in the special case of binary data, there is a one‐to‐one correspondence between the IFA model used here and the two parameter logistic item response theory models.

2.3.2. MI definitions

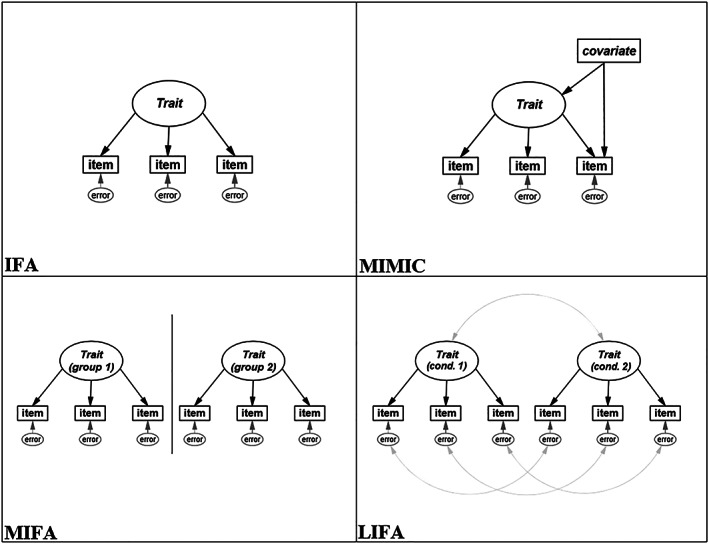

MNI refers to differences in the parameters (loadings and thresholds) of the IFA model. Such differences may occur (a) between several groups assessed synchronously, (b) at the same group assessed in different conditions, and/or (c) due to the effect of a covariate (age, for instance) and raise concerns of bias in the measurement. To be able to compare the scores (here, number of symptoms endorsed) across groups or conditions, full or at least partial MI needs to be established. Assuming that the same model applies in all groups or conditions (i.e., the model under consideration fits well in the data for each group or condition—i.e., configural invariance), MI requires both equal loadings (metric invariance) and equal thresholds (scalar invariance), across groups or conditions. That is, to establish MI, we first tested if the loadings of the items on the latent traits are invariant across groups or conditions (weak, metric, or loadings invariance). If the loadings were equal, then we proceeded with testing the equality of the thresholds (scalar or strong invariance). The items with both equal loadings and thresholds across groups and conditions are hereafter referred to as measurement invariant (MI items). If all items were invariant, then full MI was assumed (MI for all items). Frequently, not all items satisfied both the metric and the scalar invariance steps. In this case, we established partial rather than full MI. For example, if the loading of one item differed significantly across groups or conditions, then the procedure ended for this item. The procedure however continued for the rest of the items, to test for scalar invariance because metric invariance could be established. The items with either unequal loadings or unequal thresholds across groups and conditions are referred to hereafter as measurement noninvariant (MNI items). Depending upon the potential source of noninvariance considered, different statistical models were used. Figure 1 depicts the three different model settings (based on the basic IFA model) used here, namely, (a) the multiple group IFA (MIFA) model (Muthen & Christoffersson, 1981), (b) the longitudinal IFA (LIFA) model (Muthen, 1996), and (c) the multiple indicators multiple causes (MIMIC) model (Muthén, 1979, 1989b).

Figure 1.

Model specifications (trait: here, inattention or hyperactivity/impulsivity; item: here, symptom criterion; error: residual variances; group: here, gender; covariate: here, age or co‐occurring diagnoses; Cond. 1 and Cond. 2: here, informants. Black arrows denote loadings, and grey curved arrows denote correlations).

2.3.3. Multiple group IFA

MIFA was used to assess the gender differences in the IFA models, for the IA and HI traits separately. In categorical items, some authors suggest that the loadings and the thresholds of the indicators should be freed or relaxed in tandem, because together, they form the item characteristic curve (Muthén & Muthén, 1998), meaning that the metric invariance stage is omitted. Other authors disagree (Millsap, 2012). We present both steps for completeness and to match the differential item functioning definitions under the item response theory framework (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Successive models and constraints implemented in the evaluation of invariance across groups or conditions

| M1 (configural) | M2 (metric) | M3 (scalar) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group (or condition) a | A | B | A | B | A | B |

| Loadings | Freely estimated | Freely estimated | Constrained b to be equal | Constrained b to be equal | ||

| Thresholds | Freely estimated | Freely estimated | Freely estimated | Freely estimated | Constrained b to be equal | |

| Residual variances | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Factor means | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Freely estimated |

| Factor variance | 1 | 1 | 1 | Freely estimated | 1 | Freely estimated |

In multiple group item factor analysis, A: males, B: females. In longitudinal item factor analysis, A: parents, B: teachers. B is the reference group.

In the case of partial rather than full measurement invariance, the constraints for the measurement noninvariance items were relaxed.

A series of three models were fitted, from the least restricted (configural invariance) to the most restricted model (threshold invariance), and are summarised in Table 1. Specifically, in M1, all loadings and thresholds were freely estimated. In M2, the loadings are restricted to be equal across genders, for the metric invariance evaluation. In M3, in addition to the loadings, the thresholds were also restricted to be equal across genders, for the scalar invariance evaluation. For the identification of the model, additional constraints are required. To set the metric of the scale, either the latent factor is assumed to follow a standard normal distribution (mean zero and variance one) or, alternatively, one item per factor needs to be constrained. Depending upon the model tested in each case and its constraints, we adjusted our choices of model identification constraints accordingly (see Table 1). The residual (error) variances were also constrained to unity, to have a unique solution for the model parameters (identified model).

2.3.4. Longitudinal IFA

The dependencies introduced in the model by rating the same sample twice can be accounted for by the LIFA model (for instance, see Liu et al., 2017). Parent and teacher INFA ratings refer to the exact same children (dependent samples), as opposed to the independent samples studied in MIFA (e.g., boys vs. girls responses). Thus, MIFA should not be used in this comparison as it fails to take under consideration these dependencies of the observations. In the LIFA model, the latent trait (IA or HI) was formed twice within the same model (dual factors), once derived from parent INFA and the other from teacher INFA. The steps described for the MIFA model and summarised in Table 1 were repeated for the LIFA model. To reflect the dependencies in the responses, the pairs of indicators that corresponded to the same symptom and the dual factors (parent INFA–teacher INFA) were set to covary (all covariances are denoted by double‐headed, curved arrows in Figure 1).

A limitation of the method is that homogeneity is assumed within teacher and parent groups. That is, it is assumed that the informant‐related variability is due to the type of the informant (between parents and teachers) rather than due to individual differences (within parents' and teachers' groups). To be able to account for the variability within each informant group, the number of children of each parent should run into several tens if not hundreds (depending upon the magnitude of the effect as in any statistical test), which is not feasible here. This limitation was therefore considered acceptable within the scope of this work.

2.3.5. MIMIC model

The MIMIC model is essentially an IFA model with covariates. Similarly to regression, the MIMIC model considers the effect of a covariate (gender, age, or co‐morbidity) onto the latent trait (indirect effect) and the additional effect (direct effect) the covariate(s) might have on the selected item(s). If the direct effect of a covariate on an item (symptom) is significant, then MNI due to the covariate is evident for that item.

The MIMIC model is most often implemented to test invariance in the case of a numerical covariate or in the presence of multiple covariates. Here, it was used to evaluate MI due to age, as well as due to co‐morbidity, adjusted at the same time for age and gender. In all cases, the direct effects were constrained initially to zero, and, based on the improvement of the model fit, the equality constraints were relaxed gradually. The model that included only significant direct effects was considered as the final model, in all cases. The limitation of the MIMIC model is that it evaluates directly the scalar invariance but, unlike MIFA, it can be used for continuous covariates.

All analyses were conducted in Mplus (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2012) using the theta parametrisation (Muthén & Asparouhov, 2002, for details). The estimator that used the analysis was the robust weighted least squares estimator (Muthén, du Toit, & Spisic, 1997).

Goodness of fit

MIFA and LIFA invariance testing were conducted by fitting a series of nested models (with and without equality/invariance constraints) and evaluating the difference in their fit via a chi‐square test (often referred to as the DIFTEST, Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2012). For the model fit assessment, we used the relative chi‐square (relative χ 2; values close to 2 indicate close fit; Hoelter, 1983), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA; values less than 0.8 are required for an adequate fit; Browne & Cudeck, 1993), the Taylor–Lewis index (TLI; values higher than 0.9 are required for close fit; Bentler & Bonett, 1980), and the comparative fit index (CFI; values higher than 0.9 are required for close fit; Bentler, 1990).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Demographic characteristics

The initial sample consisted of 3,229 participants, of whom 1,788 had complete ADHD ratings by parents and teachers. Among those, 1,383 children were randomly selected for this study ensuring at the same time that only one child per family would be included (siblings have been prioritised). In the final sample, there were 247 females (17.9%) and 1,136 males, aged from 4 to 19 years (mean = 10.9, SD = 2.9 years). According to the t test, the genders did not differ with respect to age (t = 1.125, df = 1,358, p = .261).

3.2. MI across informants (LIFA)

3.2.1. Inattention

In the case of the IA items, the fit of the (LIFA dual) model was satisfactory (relative χ 2 = 3.8, CFI = 0.97, TLI = 0.96, RMSEA = 0.046). Partial metric invariance held for the symptoms listens, instructions, disorganised, unmotivated, and distracted (χ 2 = 8.5, df = 4, p = .075), indicating that the symptoms were related to IA equivalently for parents and teachers. Partial scalar invariance however held only for the disorganised and unmotivated items (χ 2 = 2.7, df = 1, p = .100).

Our results suggest that for the same absolute levels of IA, the two types of INFAs had the same expected response (probability of endorsing) in the cases of two criteria only: disorganised and unmotivated (Table 2). The parents were more likely than teachers to endorse careless, listens, loses, distracted, and forgetful (smaller threshold parameter). The teachers were more likely than parents to endorse attention and distracted. In summary, MNI was evident in seven out of nine IA symptom criteria.

Table 2.

Unstandardised item parametersa and correlations between same symptom indicators, for the most constraint models (invariant coefficients are denoted with bold)—Longitudinal item factor analysis model

| Inattention | Hyperactivity/impulsivity | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | Loading | Threshold | Correlation | Item | Loading | Threshold | Correlation |

| Careless | 2.63 (0.69) | −3.72 (−1.14) | .11b | Fidgets | 1.41 | −1.56 | .28 |

| Attention | 0.34 (0.80) | 0.28 (−1.39) | .00b | Seat | 1.20 | −0.78 | −.04b |

| Listens | 0.52 | −0.73 (−0.53) | −.04b | Runs/climbs | 1.69 (1.50) | −1.71 (−0.48) | .34 |

| Instructions | 0.64 | −0.34 (−0.49) | −.17 | Quiet | 1.04 (0.99) | 0.01 (−0.56) | −.07b |

| Disorganised | 0.89 | −1.34 | .23 | Motor | 1.62 (1.71) | −0.62 (−1.65) | −.21b |

| Unmotivated | 0.74 | −0.95 | .14b | Talks | 1.10 | −1.03 | .19 |

| Loses | 1.14 (0.56) | −0.44 (−0.26) | .18 | Blurts | 0.58 (1.36) | −0.29 (−1.19) | .19 |

| Distracted | 0.84 | −2.41 (−1.86) | .15b | Wait | 0.86 (1.90) | −0.66 (−1.94) | .27 |

| Forgetful | 1.01 (0.45) | −0.44 (0.03b) | −.10b | Interrupts | 0.92 (1.64) | −2.06 (−1.61) | −.02b |

Negative thresholds indicate that the 50% chance of endorsing is located below the average trait (0). Positive thresholds indicate that the 50% chance of endorsing is located above the average trait (0).

In the presence of noninvariance, the parents' coefficients are presented with teachers' coefficients within brackets.

Not significantly different than zero.

3.2.2. Hyperactivity

With respect to the HI, the fit of the (LIFA dual) model was also satisfactory (relative χ 2 = 3.8, CFI = 0.97, TLI = 0.96, RMSEA = 0.046). Partial metric invariance held for the symptoms fidgets, seat, and talks (χ 2 = 5.297, df = 2, p = .071). Partial scalar invariance also held for these three symptoms only (χ 2 = 2.274, df = 2, p = .321).

Both INFA ratings concur with the same probability of endorsing the symptoms fidgets, seat, and talks (Table 2), indexing the same absolute levels of HI. However, teachers were more likely than parents to endorse quiet, motor, blurts, and wait as present. Parents were more likely than teachers to endorse the symptoms forgetful and listens. In summary, MNI was evident in six out of nine HI symptom criteria.

Table 2 presents the estimated item parameters and the (tetrachoric) correlations between the same symptom indicators for the final models. It is striking that MI could not be established for both loadings and thresholds for most of the ADHD symptom criteria. If both INFAs essentially measured the same underlying concept, we would expect to find more concurrence with regard to thresholds and loadings across the 18 items. This result provides evidence that parent and teacher INFAs essentially do not measure the same underlying concept. Moreover, the correlations were strikingly low and nonsignificant, which further confirms the conceptual discrepancies between INFAs.

3.3. MI across genders (MIFA)

Do boys and girls with the same absolute levels of the traits (IA or HI) have the same probability of symptom endorsement, according to (a) parental assessment, (b) teacher assessment, (c) combining ratings using the ‘and‐rule,' and (d) combining ratings using the ‘or‐rule' ? Detailed results are presented in Table 3.

-

a

Parental assessment

Table 3.

Gender noninvariant items and difference in the model fit (DIFFTEST), per trait and per type of items—Multiple group item factor analysis model

| Invariance | Inattention | Hyperactivity/impulsivity | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rating | Type | MNI itema | χ 2 | df | p | MNI itema | χ 2 | df | p |

| Parents | Metric | — | 10.73 | 8 | .218 | — | 7.92 | 8 | .441 |

| Scalar | Unmotivated and loses | 9.97 | 7 | .126 | Talks | 11.74 | 7 | .110 | |

| Teachers | Metric | — | 5.76 | 8 | .674 | — | 3.75 | 8 | .879 |

| Scalar | Forgetful | 5.23 | 7 | .631 | Talks | 13.75 | 7 | .056 | |

| And‐rule | Metric | — | 14.14 | 8 | .078 | — | 2.73 | 8 | .950 |

| Scalar | — | 8.80 | 8 | .360 | Talks | 12.25 | 7 | .093 | |

| Or‐rule | Metric | — | 12.83 | 8 | .118 | — | 6.86 | 8 | .552 |

| Scalar | Loses and forgetful | 11.79 | 6 | .067 | Talks | 12.05 | 7 | .099 | |

Abbreviation: MNI, measurement noninvariance.

Indicates measurement noninvariant symptom criteria ratings.

[Correction added on 1 August 2019, after first online publication: Missing data on Table 3 has been inserted in this version.]

IA: Metric invariance was present for all symptom criteria, indicating that all symptoms were equally related to IA across genders. Scalar invariance was established for all symptoms apart from unmotivated and loses. The parents endorsed unmotivated more easily in boys compared with girls (unstandardised thresholds: −0.8 for boys and −0.6 for girls). The opposite occurred for loses (unstandardised thresholds: 0 vs. −0.4, for boys and girls, respectively).

HI: Metric invariance held for all symptom criteria, and scalar invariance was established for all symptoms apart from talks. The parents endorsed talks more easily in boys compared with girls (unstandardised thresholds: −1 for boys and −0.6 for girls).

In summary, MI was evident in the parent INFA ratings in seven out of nine symptoms of IA and in eight out of nine of HI. That is, parent INFA ratings were invariant with respect to gender in more than 80% of the ADHD symptoms, and we conclude that the child's gender did not bias notably the parent INFA ratings.

-

b

Teacher assessment

IA: Full metric invariance was present, and scalar invariance was evident for all symptoms apart from forgetful. The teachers endorsed forgetful more easily in girls than in boys (unstandardised thresholds: 0.8 for boys and 0.4 for girls).

HI: Full metric invariance was also present, and scalar invariance was evident for all symptoms apart from talks, as in the case of parents' ratings. Like the parents, the teachers endorsed talks more easily in girls than in boys (unstandardised thresholds: 0.5 for boys and 0.9 for girls).

In summary, teacher INFA ratings were invariant (nonbiased) with respect to gender in 90% of the ADHD symptoms, and we conclude that the child's gender did not bias notably the teacher INFAs ratings.

-

c

Combining ratings using the ‘and‐rule'

When the ‘and‐rule' was used to combine the information from parent and teacher INFAs in IA, full MI was established (full metric and scalar invariances for all symptom criteria). In HI, full metric invariance also held, but scalar invariance was evident in all items apart from talks. When the ‘and‐rule' is employed, the probability of symptom talks endorsement was higher in girls than in boys (unstandardised thresholds: 0.8 for boys and 1.2 for girls).

In summary, ‘and‐rule' combined‐information ratings were invariant with respect to gender in 17 out of the 18 ADHD symptoms, and we conclude that the child's gender did not bias these ratings.

-

d

Combining ratings using the ‘or‐rule'

Full metric invariance was established in the case of the ‘or‐rule' combined‐information items for both IA and HI. With respect to scalar invariance, partial invariance was established for all symptoms apart from the forgetful and loses criteria for IA and talks for HI. The endorsement probability for both symptoms forgetful and loses was higher in girls than in boys (unstandardised thresholds: forgetful: −0.8 for boys and −0.4 for girls; loses: −0.8 for boys and −0.4 for girls). The probability of symptom talks endorsement was higher in girls than in boys (unstandardised thresholds: −1.4 for boys and −0.9 for girls).

In summary, the ‘or‐rule' combined‐information ratings were invariant with respect to gender in 15 out of the 18 ADHD symptoms, and we conclude that the child's gender did not bias notably these ratings.

3.4. Age invariance

When a significant direct effect is positive, the symptom is expected to be endorsed more often for each unit of age increase and for the same absolute levels of the trait. Conversely, if the effect is negative, this probability decreases. Significant direct age effects are reported in Table 4.

Table 4.

Significant direct effects of age, per trait and per type of items— MIMIC model

| Inattention | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parents | Teachers | And‐rule | Or‐rule | |||||

| Effect | p value | Effect | p value | Effect | p value | Effect | p value | |

| Careless | ||||||||

| Attention | ||||||||

| Listen | −0.03 | .026 | ||||||

| Instructions | ||||||||

| Disorganised | ||||||||

| Unmotivated | 0.06 | <.001 | 0.06 | .001 | ||||

| Loses | ||||||||

| Distracted | −0.04 | .020 | ||||||

| Forgetful | 0.03 | .036 | ||||||

| Hyperactivity/impulsivity | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parents | Teachers | And‐rule | Or‐rule | |||||

| Effect | p value | Effect | p value | Effect | p value | Effect | p value | |

| Fidgets | ||||||||

| Seat | −0.04 | .019 | ||||||

| Runs/climbs | −0.11 | <.001 | −0.05 | .003 | −0.08 | <.001 | ||

| Quiet | ||||||||

| Motor | 0.25 | <.001 | 0.07 | <.001 | 0.12 | <.001 | ||

| Talks | 0.06 | <.001 | ||||||

| Blurts | 0.04 | .002 | 0.06 | .001 | 0.04 | .006 | 0.04 | .013 |

| Wait | 0.05 | .013 | ||||||

| Interrupts | 0.04 | .021 | −0.07 | .032 | ||||

IA: The probability of endorsing unmotivated increased with age, both in the parent ratings and in the ‘and‐rule' combined‐information ratings. Age affected positively the endorsement of forgetful for teachers (higher probability of endorsing the symptom as age increases, for the same absolute values of IA). Negative effects were present when the ‘or‐rule' combined‐information ratings were considered in the endorsement of listens and distracted (lower probability of endorsing the symptoms as age increases, for the same absolute values of IA). All direct effects were however very low in magnitude (<0.1 in absolute value), indicating that age does not notably bias the IA ratings.

HI: A larger number of significant direct effects emerged, compared with IA. The older the child, the less likely it was for parents to endorse runs/climbs. On the contrary, the older the child, the more likely it was for parents to endorse motor and blurts. The same effects were evidenced when the combined‐information ratings were considered. Additionally, significant positive direct effects were present in the teachers' INFA ratings for talks, waits, blurts, and interrupts, and significant negative effects were present in the ‘or‐rule' combined ratings for seat.

Among those significant direct effects, only the positive effect of age on the parent INFAs endorsement of motor was of low to moderate magnitude (0.25). All direct effects were very low in magnitude (<0.1 in absolute value), indicating that age does not notably bias the HI ratings.

3.5. Co‐occurring diagnoses invariance

In this section, we investigate whether the probability of endorsing a symptom is affected (biased) by co‐occurring diagnoses, adjusted for age and gender, and IA or HI. Significant direct effects are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Significant direct effects for each co‐occurring diagnosis, separately per trait and per type of rating (p‐values are within parentheses)—MIMIC models are adjusted for age and gender

| Inattention | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety disorder | Conduct disorder | Oppositional defiant disorder | ||||

| Parents | Teachers | Parents | Teachers | Parents | Teachers | |

| Careless | ||||||

| Attention | 0.18 (.020) | 0.47 (<.001) | 0.27 (.001) | |||

| Listen | ||||||

| Instructions | ||||||

| Disorganised | ||||||

| Unmotivated | 0.23 (.022) | 0.55 (<.001) | 0.39 (<.001) | |||

| Loses | 0.34 (.020) | |||||

| Distracted | ||||||

| Forgetful | ||||||

| ‘And‐rule' | ‘Or‐rule' | ‘And‐rule' | ‘Or‐rule' | ‘And‐rule' | ‘Or‐rule' | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Careless | ||||||

| Attention | 0.34 (<.001) | 0.21 (.011) | ||||

| Listen | ||||||

| Instructions | ||||||

| Disorganised | ||||||

| Unmotivated | 0.23 (.013) | 0.29 (.024) | ||||

| Loses | 0.24 (.018) | 0.20 (.026) | ||||

| Distracted | ||||||

| Forgetful |

| Hyperactivity/impulsivity | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety disorder | Conduct disorder | Oppositional defiant disorder | ||||

| Parents | Teachers | Parents | Teachers | Parents | Teachers | |

| Fidgets | −0.30 (.019) | |||||

| Seat | −0.23 (.045) | −0.36 (.001) | ||||

| Runs/climbs | −0.24 (.025) | |||||

| Quiet | ||||||

| Motor | ||||||

| Talks | −0.41 (.002) | |||||

| Blurts | −0.21 (.036) | |||||

| Wait | 0.18 (.039) | |||||

| Interrupts | 0.28 (.016) | 0.39 (.015) | ||||

| ‘And‐rule' | ‘Or‐rule' | ‘And‐rule' | ‘Or‐rule' | ‘And‐rule' | ‘Or‐rule' | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fidgets | ||||||

| Seat | ||||||

| Runs/climbs | −0.49 (.005) | −0.34 (.001) | 0.46 (.001) | |||

| Quiet | 0.25 (.008) | |||||

| Motor | 0.28 (.019) | |||||

| Talks | −0.34 (.018) | |||||

| Blurts | −0.24 (.010) | |||||

| Wait | ||||||

| Interrupts |

3.5.1. Co‐occurring anxiety disorder

IA: Co‐occurring anxiety disorder (AD) increased the probability of endorsement of attention and unmotivated in the parents' ratings. There was no effect on the teacher INFA or the combined‐information ratings.

HI: Co‐occurring AD had no effect on either the parents' or the teachers' ratings. When the ratings were combined, co‐occurring AD decreased the probability of endorsement for runs/climbs in the ‘and‐rule' ratings and the probability of endorsement of blurts in the ‘or‐rule' ratings. We will only report positive or negative significant effects, for conciseness.

Based on our results, co‐occurring AD does not notably bias the symptom criteria endorsement of ADHD.

3.5.2. Co‐occurring conduct disorder

IA: Co‐occurring conduct disorder (CD) increased the probability of endorsement of attention, unmotivated, and loses in the parent INFAs ratings. Similarly, co‐occurring CD increased the probability of endorsement of attention and loses in the ‘and‐rule' combined‐information ratings.

HI: Co‐occurring CD decreased the probability of endorsement of talks and blurts in the parent INFAs ratings. Similarly, co‐occurring CD decreased the probability of endorsement of seat on the teachers' ratings but increased the probability of endorsing interrupts. In the combined‐information ratings, co‐occurring CD decreased the probability of endorsing talks on the ‘or‐rule' ratings but increased the probability of endorsing motor on the ‘and‐rule' ratings.

In summary, co‐occurring CD only affected the probability of endorsement of the IA criteria in parent INFA ratings. Also, co‐occurring CD affected the probability of endorsement to some of the HI symptom criteria, which were different depending on INFA.

3.5.3. Co‐occurring oppositional defiant disorder

IA: Co‐occurring oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) increased the probability of endorsement of attention and unmotivated in the parents' ratings. With respect to the combined‐information ratings, co‐occurring ODD also increased the probability of endorsing unmotivated in both combined ratings. Additionally, co‐occurring ODD also increased the probability of endorsing attention and loses in the ‘and‐rule' items.

HI: Co‐occurring ODD influenced four symptom criteria, in relation to parent INFAs ratings. Specifically, when ODD was present, the probability of the parents endorsing fidgets and seat was increased, whereas the probability of endorsing wait and interrupts was increased. In the ‘and‐rule' ratings, the endorsement probability of quiet was increased, and runs/climbs was decreased; in contrast, runs/climbs was increased in the ‘or‐rule' ratings. With respect to teachers' ratings, when ODD was present, only the probability of endorsing runs/climbs was decreased. The probability of endorsing runs/climbs was also increased with the presence of ODD in the ‘or‐rule' combined‐information ratings but decreased when the ‘and‐rule' was used. Finally, the probability of endorsing quiet was increased with the presence of ODD when the ‘and‐rule' was used.

Based on our results, co‐occurring ODD does not notably bias the symptom criteria endorsement of ADHD. In summary, co‐occurring ODD affected the probability of endorsement of ADHD symptom criteria in parent INFA.

4. DISCUSSION

In this work, we examined the potential influence (measurement bias) introduced in the ratings of the ADHD symptom criteria due to INFAs, gender, age, co‐occurring diagnoses (AD, CD, and ODD in particular), and the rule to combine INFA ratings. Our results indicate substantial MNI between parents' and teachers' ratings (i.e., seven out of nine IA and six out of nine HI items), implicating that they capture different aspects of children's behaviour. Second, within informant, age and gender did not markedly affect symptom endorsement probabilities. Third, with respect to co‐occurring diagnoses, teacher INFA ratings were essentially uninfluenced by the presence of AD, CD, and ODD. On the other hand, the parents' endorsement probabilities were mildly influenced by AD and more notably influenced by ODD. Fourth, 17 out of 18 items were invariant using the “and” rule to combine INFA ratings; 15 of 18 items were invariant using the “or” rule. Our findings suggest a general robustness of DSM ADHD diagnostic items in relation to the potential influences of the factors examined. Parents and teachers appear to capture different patterns of behaviours, which may reflect different expressions of a trait or different underlying traits; the “or” rule may capture a richer picture of a child's ADHD phenomenology.

The differences between INFAs can be partially attributed to the differences between the children's behaviours at school and at home. A quantitative genetic twin study identified that the information provided by parents and teachers is different and that they report different psychopathological phenomena (Arnett et al., 2015). Furthermore, Hartman, Rhee, Willcutt, and Pennington (2007) found in their twin modelling study that the best fit model of their data includes unique genetic contributions from parents and teachers. Parent and teacher INFAs may validly describe different aspects of behaviour. They should be seen as different sources of information to be combined by the expert clinician, in the context of a holistic biopsychosocial psychiatric assessment.

MI in relation to gender was evident. The symptoms related to the trait in a similar manner for both genders; there is no evidence for the same behaviours are being assessed differently across genders. Thresholds differed for only four items. Standard methods can therefore be used to assess the differences in the total number of symptoms between genders. This is consistent with the literature reviewed in this paper.

Similarly, age affected the endorsement only of unmotivated (parents) and forgetful (teachers). Even for HI symptoms, the effect sizes of the estimates were very low and unlikely to have any notable impact in clinical settings.

None of the co‐occurring diagnoses influenced the teachers' probability of endorsing the IA items. With respect to HI, AD did not affect the teacher INFAs probability of endorsing any of the symptoms; ODD reduced the probability of endorsing only in one symptom (runs/climbs); and CD affected the teacher INFA probability of endorsing in two symptoms (negatively seat and positively interrupts). On the basis of these results, we conclude that the teachers' ratings are not markedly biased in the presence of co‐occurring diagnosis.

For parent INFAs IA ratings, attention and unmotivated endorsements were positively affected in all cases (ODD, CD, and AD) and loses only in the case of co‐occurring CD. With respect to HI, AD did not affect the parent INFAs probability of endorsing any of the symptoms; CD reduced the probability of endorsing two symptoms (talks and blurts); and ODD reduced the probability of endorsing two symptoms (seat and fidgets) and increased the probability of endorsement in two more (wait and interrupts). On the basis of these results, we conclude that parents' ratings are influenced by the presence of ODD, in particular, the measurement of the HI items.

In addition to age, gender, and co‐morbidity effects on informant ratings, we also evaluated the invariance when the ratings are combined by using the “or” and the “and” rules. The “and” rule captures pervasiveness of symptomatology and potentially severity. As recognised in DMS‐5, “manifestations of the disorder have to be present in more than one setting.” The combined‐information items reflect invariances present on INFA's ratings or cancel those invariances out. Interestingly, there were fewer MNI symptoms using the ‘and‐rule' than when using the ‘or‐rule,' in terms of gender (Table 3) and age (Table 4; apart from the direct effects of age in IA). That is, the ‘and‐rule' was less prone to invariance due to gender and age. The reverse held with respect to co‐occurring diagnosis (Table 5); there were more measurement invariant symptoms using the ‘and‐rule' than when using the ‘or‐rule.' Overall, there is no substantial difference between the two methods in terms of invariance.

Our study further develops the idea of “situational/informant specificity” of certain ADHD symptoms: This means that the rating differences between parents and teachers may also be influenced by age and gender. Rucklidge (2010) suggested that the reported male preponderance might be attributable to referral bias leading to underidentification of ADHD in young females. Genetic model fitting of population twin samples have also identified differences between parent and teacher ratings. Nikolas and Burt (2009) reviewed the pattern of genetic and environmental influences on ADHD symptom dimensions and found that the genetic contribution to mothers' ratings included as dominant genetic factors for inattentiveness (25%); in contrast, 77% of the variance in ADHD as defined by teacher ratings was attributable to additive genetic factors for both hyperactivity and inattentiveness with no significant contributions from dominant genetic factors (0%).

Sex‐specific genetic dominant genetic influences in boys have been suggested (Nikolas & Burt, 2009). Those findings are consistent with the idea posited by Rucklidge (2010) that symptom thresholds should be adjusted for gender and that separate standards of measurement should be used according to gender. Overall, our findings do not support gender specificity like those of Monuteaux et al. (2010), Gomez and Hafetz (2011), and Gomez (2012, 2016). Clinicians might note a few gender‐specific items (unmotivated and talks for boys and loses for girls, as rated by parents; forgetful in boys and talks for girl, as rated by teachers).

HI items are associated with age, as rated by teacher INFAs. Parent INFAs appear to rate certain items differently in the presence of co‐morbidity, whereas teachers seem less susceptible. It may also be that teacher INFAs are better at differentiating one co‐morbid disorder from another thus avoiding the potential conflation, as expressed as cross‐loading.

Our study is novel in four aspects. To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate MI within the same data regarding ADHD symptoms (a) in relation to age, gender, and co‐occurring diagnosis using naturalistic parent and teacher assessments in keeping with NICE guidance and routine clinical practice and (b) between INFAs. It is also novel in assessing MI and its implication in combining parent and teacher INFAs using the “and” and “or” rules. If our findings were replicated by future studies, the findings could potentially have significant implications on the diagnostic criteria adopted by future classification systems, with regard to the item calibration, gender specificity, and the source of information (i.e., parent or teacher INFAs). Clinicians' understanding of problems of impulsiveness and attention in classrooms might need some further conceptual development in terms of the impact of ADHD features in the classroom.

Our sample consisted of participants recruited from different centres located in different European countries; Müller et al. (2011a) have demonstrated the multilevel nature of our data with potential factors influencing symptom levels as well as age and gender effects across centres and countries inherent in most multicentre studies. Our focus is not on the properties of certain assessment tools but on the measurement outcome itself, in a naturalistic setting, in keeping with the NICE Guidance for ADHD (2018). Given the cross‐sectional design of the IMAGE study, the effects of developmental trajectories could not be modelled. The IMAGE data were collected based on DSM‐IV criteria. The key changes in DSM5 include “threshold criteria relating to age,” “pervasiveness,” and the combination of dimensionality with category. As there is no substantial change in the wording of the ADHD criteria between DSM‐IV and DSM5, our findings would at large be relevant to clinical practice and research using the DSM5 system. However, our findings must therefore be considered as preliminary and should be interpreted with caution pending further investigations.

DECLARATION OF INTEREST STATEMENT

E. S. B.: Speaker fees, consultancy, research funding and conference support from Shire Pharma and Janssen Cilag. Consultancy from Neurotech Solns, Aarhus University, Copenhagen University and Berhanderling, Skolerne, Copenhagen, and KU Leuven. Book royalties from OUP and Jessica Kinglsey. Royalties from the New Forest Parenting Package.

T. B. served in an advisory or consultancy role for Actelion, Hexal Pharma, Lilly, Lundbeck, Medice, Novartis, and Shire, received conference support or speaker's fee by Lilly, Medice, Novartis, and Shire, has been involved in clinical trials conducted by Shire and Viforpharma, and received royalties from Hogrefe, Kohlhammer, CIP Medien, and Oxford University Press.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The International Multisite ADHD Genetics (IMAGE) project is a multisite, international effort. Funding support for the IMAGE project was provided by NIH Grants R01MH62873 and R01MH081803 to S. V. Faraone. The IMAGE site principal investigators are Philip Asherson, Tobias Banaschewski, Jan Buitelaar, Richard P. Ebstein, Stephen V. Faraone, Michael Gill, Ana Miranda, Fernando Mulas, Robert D. Oades, Herbert Roeyers, Aribert Rothenberger, Joseph Sergeant, Edmund Sonuga‐Barke, and Hans‐Christoph Steinhausen. Chief investigators at each site are Rafaela Marco, Nanda Rommelse, Wai Chen, Henrik Uebel, Hanna Christiansen, Ueli C. Mueller, Cathelijne Buschgens, Barbara Franke, and Lamprini Psychogiou. We thank all. Silia Vitoratou was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King's College London. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, or the Department of Health. The authors are grateful to Professor Andrew Pickles for advice and support and the Alicia Koplowitz Foundation, which sponsored Dr Alexandra Garcia‐Rosales. We also thank the children and families participating in the IMAGE project.

Vitoratou S, Garcia‐Rosales A, Banaschewski T, et al. Is the endorsement of the attention deficit hyperactivity disorder symptom criteria ratings influenced by informant assessment, gender, age, and co‐occurring disorders? A measurement invariance study. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2019;28:e1794 10.1002/mpr.1794

Silia Vitoratou and Alexandra Garcia‐Rosales are joint first authors.

Footnotes

A fourth step is to test if the variability of the symptom endorsement not accounted for by the latent trait (specificity) is equal across groups or conditions. This is the residual invariance, and it is established if the residual variances (i.e., variability not explained by the latent trait) of a given item in (1) are equal across groups or conditions. However, in binary items, the residuals are required to be equal across genders and conditions for the identification of the model, and thus, this type of invariance was not examined.

The probit function Φ is the inverse of the cumulative distribution function of the standard normal distribution.

REFERENCES

- Amador, J. A. , Forns, M. , Guàrdia Olmos, J. , & Peró, M. (2006). Estructura factorial y datos normativos del Perfil de atención y del Cuestionario TDAH para niños en edad escolar. Psicothema, 18(4), 696–703. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM‐IV‐TR. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett, A. B. , Pennington, B. F. , Willcutt, E. G. , DeFries, J. C. , & Olson, R. K. (2015). Sex differences in ADHD symptom severity. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 56(6), 632–639. 10.1111/jcpp.12337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler, P. M. (1990). Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin, 107(2), 238–246. 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler, P. M. , & Bonett, D. G. (1980). Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychological Bulletin, 88(3), 588–606. 10.1037/0033-2909.88.3.588 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Biederman, J. , Mick, E. , & Faraone, S. V. (2000). Age‐dependent decline of symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: Impact of remission definition and symptom type. American Journal of Psychiatry, 157(5), 816–818. 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.5.816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne, M. W. , & Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sage focus editions, 154, 136–136. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, G. L. , Desmul, C. , Walsh, J. A. , Silpakit, C. , & Ussahawanitchakit, P. (2009). A multitrait (ADHD–IN, ADHD–HI, ODD toward adults, academic and social competence) by multisource (mothers and fathers) evaluation of the invariance and convergent/discriminant validity of the Child and Adolescent Disruptive Behavior Inventory with Thai adolescents. Psychological Assessment, 21(4), 635–641. 10.1037/a0016953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns, G. L. , Walsh, J. A. , Gomez, R. , & Hafetz, N. (2006). Measurement and structural invariance of parent ratings of ADHD and ODD symptoms across gender for American and Malaysian children. Psychological Assessment, 18(4), 452–457. 10.1037/1040-3590.18.4.452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caci, H. M. , Morin, A. J. , & Tran, A. (2016). Teacher ratings of the ADHD‐RS IV in a community sample: Results from the ChiP‐ARD study. Journal of Attention Disorders, 20(5), 434–444. 10.1177/1087054712473834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W. , & Taylor, E. (2006). Parental account of children's symptoms (PACS), ADHD phenotypes and its application to molecular genetic studies. Attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder and the hyperkinetic syndrome: Current ideas and ways forward, 11788, 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W. , Zhou, K. , Sham, P. , Franke, B. , Kuntsi, J. , Campbell, D. , et al. (2008). DSM‐IV combined type ADHD shows familial association with sibling trait scores: A sampling strategy for QTL linkage. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part B: Neuropsychiatric Genetics, 147(8), 1450–1460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cogo‐Moreira, H. , Lúcio, P. S. , Swardfager, W. , Gadelha, A. , Mari, J. D. J. , Miguel, E. C. , … Salum, G. A. (2017). Comparability of an ADHD latent trait between groups: Disentangling true between‐group differences from measurement problems. Journal of Attention Disorders, 1087054717707047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collett, B. R. , Ohan, J. L. , & Myers, K. M. (2003). Ten‐year review of rating scales. V: Scales assessing attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 42(9), 1015–1037. 10.1097/01.CHI.0000070245.24125.B6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran, S. , Newman, S. , Taylor, E. , & Asherson, P. (2000). Hypescheme: An operational criteria checklist and minimum data set for molecular genetic studies of attention deficit and hyperactivity disorders. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part a, 96(3), 244–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derks, E. M. , Dolan, C. V. , Hudziak, J. J. , Neale, M. C. , & Boomsma, D. I. (2007). Assessment and etiology of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and oppositional defiant disorder in boys and girls. Behavior Genetics, 37(4), 559–566. 10.1007/s10519-007-9153-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fumeaux, P. , Roche, S. , Mercier, C. , Iwaz, J. , Bader, M. , Stéphan, P. , … Revol, O. (2017). Validation of the French version of Conners' Parent Rating Scale–revised, short version (CPRS‐R: S) scale measurement invariance by sex and age. Journal of Attention Disorders, 1087054717696767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiser, C. , Burns, G. L. , & Servera, M. (2014). Testing for measurement invariance and latent mean differences across methods: Interesting incremental information from multitrait‐multimethod studies. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 1216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez, R. (2007). Australian parent and teacher ratings of the DSM‐IV ADHD symptoms: Differential symptom functioning and parent‐teacher agreement and differences. Journal of Attention Disorders, 11(1), 17–27. 10.1177/1087054706295665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez, R. (2012). Parent ratings of ADHD symptoms: Generalized partial credit model analysis of differential item functioning across gender. Journal of Attention Disorders, 16(4), 276–283. 10.1177/1087054710383378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez, R. (2013). DSM‐IV ADHD symptoms self‐ratings by adolescents: Test of invariance across gender. Journal of Attention Disorders, 17(1), 3–10. 10.1177/1087054711403715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez, R. (2016). ADHD and hyperkinetic disorder symptoms in Australian adults: Descriptive scores, incidence rates, factor structure, and gender invariance. Journal of Attention Disorders, 20(4), 325–334. 10.1177/1087054713485206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez, R. , & Hafetz, N. (2011). DSM‐IV ADHD: Prevalence based on parent and teacher ratings of Malaysian primary school children. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 4(1), 41–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez, R. , & Vance, A. (2008). Parent ratings of ADHD symptoms: Differential symptom functioning across Malaysian Malay and Chinese children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 36(6), 955–967. 10.1007/s10802-008-9226-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartman, C. A. , Rhee, S. H. , Willcutt, E. G. , & Pennington, B. F. (2007). Modeling rater disagreement for ADHD: Are parents or teachers biased?. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 35(4), 536–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoelter, J. W. (1983). The analysis of covariance structures: Goodness‐of‐fit indices. Sociological Methods & Research, 11(3), 325–344. 10.1177/0049124183011003003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- King, K. M. , Luk, J. W. , Witkiewitz, K. , Racz, S. , McMahon, R. J. , Wu, J. , & Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group (2016). Externalizing behavior across childhood as reported by parents and teachers: A partial measurement invariance model. Assessment, 1073191116660381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y. , Millsap, R. E. , West, S. G. , Tein, J. Y. , Tanaka, R. , & Grimm, K. J. (2017). Testing measurement invariance in longitudinal data with ordered‐categorical measures. Psychological Methods, 22(3), 486–506. 10.1037/met0000075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makransky, G. , & Bilenberg, N. (2014). Psychometric properties of the parent and teacher ADHD Rating Scale (ADHD‐RS) measurement invariance across gender, age, and informant. Assessment, 21(6), 694–705. 10.1177/1073191114535242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millsap, R. E. (2012). Statistical approaches to measurement invariance. Routledge; New York, US, Abingdon, United Kingdom: 10.4324/9780203821961 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mislevy, R. J. (1986). Recent developments in the factor analysis of categorical data. Journal of Educational Statistics, 11, 3–31. 10.3102/10769986011001003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Monuteaux, M. C. , Mick, E. , Faraone, S. V. , & Biederman, J. (2010). The influence of sex on the course and psychiatric correlates of ADHD from childhood to adolescence: A longitudinal study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 51(3), 233–241. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02152.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin, A. J. , Tran, A. , & Caci, H. (2016). Factorial validity of the ADHD adult symptom rating scale in a French community sample: Results from the ChiP‐ARD study. Journal of Attention Disorders, 20(6), 530–541. 10.1177/1087054713488825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller, U. C. , Asherson, P. , Banaschewski, T. , Buitelaar, J. K. , Ebstein, R. P. , Eisenberg, J. , … Roeyers, H. (2011a). The impact of study design and diagnostic approach in a large multi‐centre ADHD study. Part 1: ADHD symptom patterns. BMC Psychiatry, 11(1), 54 10.1186/1471-244X-11-54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller, U. C. , Asherson, P. , Banaschewski, T. , Buitelaar, J. K. , Ebstein, R. P. , Eisenberg, J. , … Roeyers, H. (2011b). The impact of study design and diagnostic approach in a large multi‐centre ADHD study: Part 2: Dimensional measures of psychopathology and intelligence. BMC Psychiatry, 11(1), 55 10.1186/1471-244X-11-55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén, B. (1979). A structural probit model with latent variables. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 74(368), 807–811. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén, B. , & Asparouhov, T. (2002). Latent variable analysis with categorical outcomes: Multiple‐group and growth modeling in Mplus. Mplus Web Notes, 4(5), 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Muthen, B. , & Christoffersson, A. (1981). Simultaneous factor analysis of dichotomous variables in several groups. Psychometrika, 46(4), 407–419. 10.1007/BF02293798 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén, B. , du Toit, S.H.C. & Spisic, D. (1997). Robust inference using weighted least squares and quadratic estimating equations in latent variable modeling with categorical and continuous outcomes. Unpublished technical report.

- Muthén, B. O. (1989a). Dichotomous factor analysis of symptom data. Sociological Methods & Research, 18(1), 19–65. 10.1177/0049124189018001002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén, B. O. (1989b). Latent variable modeling in heterogeneous populations. Psychometrika, 54(4), 557–585. 10.1007/BF02296397 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén, L. K. , & Muthén, B. O. (1998. –2012). Mplus user's guide (Sixth ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Muthen, B. O. (1996). Growth modeling with binary responses In von Eye l. A., & Clogg C. C. (Eds.), Categorical variables in developmental research: Methods of analysis (pp. 37–54). San Diego ,CA, London. 10.1016/B978-012724965-0/50005-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence . (2018). Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: diagnosis and management. (Clinical guideline 87) https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng87 [PubMed]

- Newcorn, J. H. , Halperin, J. M. , Jensen, P. S. , Abikoff, H. B. , Arnold, L. E. , Cantwell, D. P. , … Hechtman, L. (2001). Symptom profiles in children with ADHD: Effects of comorbidity and gender. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 40(2), 137–146. 10.1097/00004583-200102000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikolas, M. A. , & Burt, S. A. (2009). Genetic and environmental influences on ADHD symptom dimensions of inattention and hyperactivity: A meta‐analysis. Behavior Genetics, 39(6), 671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osterlind, S. J. , & Everson, H. T. (2009). Differential item functioning (Vol. 161). Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA, New Delhi, India, London, UK, Singapore: 10.4135/9781412993913 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ramtekkar, U. P. , Reiersen, A. M. , Todorov, A. A. , & Todd, R. D. (2010). Sex and age differences in attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms and diagnoses: Implications for DSM‐V and ICD‐11. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 49(3), 217–228. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosales, A. G. , Vitoratou, S. , Banaschewski, T. , Asherson, P. , Buitelaar, J. , Oades, R. D. , … Chen, W. (2015). Are all the 18 DSM‐IV and DSM‐5 criteria equally useful for diagnosing ADHD and predicting comorbid conduct problems. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 24(11), 1325–1337. 10.1007/s00787-015-0683-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rucklidge, J. J. (2010). Gender differences in attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Psychiatric Clinics, 33(2), 357–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valo, S. , & Tannock, R. (2010). Diagnostic instability of DSM–IV ADHD subtypes: Effects of informant source, instrumentation, and methods for combining symptom reports. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 39(6), 749–760. 10.1080/15374416.2010.517172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiesner, M. , Windle, M. , Kanouse, D. E. , Elliott, M. N. , & Schuster, M. A. (2015). DISC Predictive Scales (DPS): Factor structure and uniform differential item functioning across gender and three racial/ethnic groups for ADHD, conduct disorder, and oppositional defiant disorder symptoms. Psychological Assessment, 27(4), 1324–1336. 10.1037/pas0000101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wirth, R. J. , & Edwards, M. C. (2007). Item factor analysis: Current approaches and future directions. Psychological Methods, 12(1), 58–79. 10.1037/1082-989X.12.1.58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Zeeuw, E. L. , van Beijsterveldt, C. E. , Lubke, G. H. , Glasner, T. J. , & Boomsma, D. I. (2015). Childhood ODD and ADHD behavior: The effect of classroom sharing, gender, teacher gender and their interactions. Behavior Genetics, 45(4), 394–408. 10.1007/s10519-015-9712-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]