Abstract

Objective

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC’s) recommendation for blood lead level (BLL) screening of refugee children is to test new arrivals aged 6 months to 16 years. No such recommendations exist for testing immigrant children. Our objective was to provide evidence in support of creating lower age-specific guidelines for BLL screening for newly arrived immigrant populations to reduce the burden of unnecessary BLL testing.

Methods

We conducted a 3-year (2013-2016) retrospective analysis of BLLs of 1349 newly arrived immigrant children, adolescents, and young adults aged 3-19 who visited the University of Miami Pediatric Mobile Clinic in Miami, Florida. We obtained capillary samples and confirmed values >5 μg/dL via venous sample. The primary outcome was BLL in μg/dL. The main predictor variable was age. We further adjusted regression models by poverty level, sex, and ethnicity.

Results

Of 15 patients with a BLL that warranted further workup and a lead level of concern, 9 were aged 3-5 and 6 were aged 6-11. None of the adolescent and young adult patients aged 12-19 had a lead level of concern. Nearly half of the patients (n = 658, 48.8%) lived in zip codes of middle to high levels of poverty.

Conclusion

This study provides evidence to support the creation of lower age-specific guidelines for BLL screening among newly arrived immigrant children and adolescents. Future studies should elucidate appropriate age ranges for BLL testing based on epidemiologic evidence, such as age and country of origin.

Keywords: Florida, lead, immigrant, refugee, pediatric, Miami-Dade

Lead exposure has dire health consequences for children, such as anemia, behavioral challenges, neurological deficits, and, at extremely high levels, even death.1 Despite established effects of lead exposure, uncertainty remains regarding the blood lead level (BLL) at which such effects can be seen. In 2005, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) established that cognitive, intellectual, and behavioral effects occur in children at levels even <10 μg/dL; however, recent studies show that such effects occur at levels <5 μg/dL.2 Despite the absence of an established threshold at which symptoms arise, the AAP recommends lead exposure risk assessments for children at well-child visits starting at 6 months through 3 years of age. The standard of care for lead screening supports testing for BLL at the 12- and 24-month well-child visits and is required in many states under Medicaid guidelines.3

Refugee and newly arrived immigrant children in the United States may face additional lead exposure risks both in their native countries (eg, lead-containing gasoline combustion and industrial emissions, burning of fossil fuels and waste) and on arrival to the United States (eg, exposure presumably through old housing units). For these reasons, guidelines for BLL testing among refugee children differ from guidelines for US-born children.4 The recommendations apply to children who have entered the United States and are classified as refugees. These children are subject to specific entry requirements and medical evaluation, including lead screening and follow-up. These protocols are mandated by law and funded by the US Refugee Admissions Program. However, BLL guidelines for newly arrived immigrant children do not exist. Typically, these children are seen by community providers, often sporadically, and providers are not required to follow the same lead screening standards that exist for refugee populations.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends BLL screening among all refugee children up to age 16, both on arrival to the United States and at 3 and 6 months after the initial testing for children aged 6 months to 6 years.4 CDC compiled these guidelines in 2005 after the death of a Sudanese refugee child and as a result of evidence of elevated BLLs among refugee populations in New Hampshire.5 Many refugee children are exposed to lead after their resettlement to the United States, presumably because of poor housing conditions and environmental factors (eg, contaminated soil, air, dust).4,6 Based on reports from Massachusetts, the rate of increase of BLLs among retested refugee children was 5.9%, compared with 4.4% among US-born children. The average increase was 4.9 μg/dL.7 In a New Hampshire study in 2005, 29.3% of refugee children did not have an elevated BLL on arrival to the United States, but BLLs were higher at retesting.8 These data support and validate the CDC guideline of retesting after initial determination of BLL on entry to the United States.

The relationship between BLL and age among newly arrived immigrant children is unclear. Among US-born children, the correlation between age and BLLs is clear. Lead exposure risk among children aged 6-36 months (3 years) increases because of milestones such as teething, crawling, and walking.2 After 3 years of age, this risk diminishes. However, among immigrant children, the correlation between elevated BLL and age is unknown.

Although the global burden of disease caused by lead exposure is substantial, and the recommendations pertain to refugee populations, testing every newly arrived immigrant child and adolescent through age 16 on arrival to the United States is costly for clinicians, patients, and patients’ families. In general, health care providers tend to follow the CDC guidelines for lead screening of refugees for all newly arrived immigrant children and adolescents who are seen for the first time on arrival to the United States, regardless of their legal status or classification (eg, refugee, migrant, immigrant). However, newly arrived immigrant children may not have the same resources or access to initial or follow-up care as refugee children do. For clinics that provide medical care to immigrant populations, who are typically uninsured and have limited resources, the point-of-care (POC) tests are inexpensive. Yet, if a clinic does not provide POC testing, patients are often required to travel to a laboratory to obtain a more costly venous blood test for BLL. Patients and their parents are then required to return twice, for 3- and 6-month follow-up. However, for such follow-up, transportation is not always accessible, children may miss school, and parents often miss work, which may result in lost wages.

Our study is a retrospective analysis of BLL testing among patients at a pediatric mobile clinic program that cares exclusively for immigrant children, none of whom are considered refugees. The objective of our study was to determine the incidence of elevated BLLs and the relationship between elevated BLLs and age among newly arrived immigrant children. The overall objective was to provide evidence in support of creating age-specific guidelines for BLL screening for newly arrived immigrant children to reduce the occurrence of unnecessary BLL testing.

Methods

Study Design

The study design was a retrospective medical record review of patients seen for well-child visits who received POC lead screening according to AAP/CDC guidelines. We examined the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision diagnosis codes associated with patients’ visits for a diagnosis related to lead exposure or anemia. Results were recorded in the patient’s electronic health record along with information on demographic characteristics. We used multivariable regression models to assess the association between BLLs and age at visit (years) and BLLs and age group variables, adjusting for sex, ethnicity, and poverty level.

Data Collection

We obtained study data from 2 sources: the University of Miami’s electronic health record (EHR) system (UChart) and the 2012-2016 American Community Survey (ACS), which is a detailed socioeconomic questionnaire, conducted annually, in addition to the US Census data survey.9 We reviewed EHR data for patients newly arrived to the United States who visited the Pediatric Mobile Clinic (PMC) from January 1, 2013, through December 31, 2016. We then linked the patient’s residency based on zip code included in UChart to the neighborhood poverty threshold data collected from the ACS. The University of Miami Institutional Review Board reviewed and approved this study.

Study Sample

Newly arrived immigrant children, adolescents, and young adults who visited the PMC during 2013-2016 for a well-child visit and were aged 3-19 fit the eligibility criteria for analysis. Because of CDC BLL testing recommendations for children aged 1 or 2, when the patients were seen we excluded data on children aged ≤2 from the analysis (n = 271). The inclusion criterion was arrival in the United States <3 months before the visit. We also excluded data from 1 patient record that was missing a BLL value and 2 patient records that were missing zip code information. The final sample included 1349 children, adolescents, and young adults aged 3-19.

Study Outcome

Our primary outcome was BLL in μg/dL. These data were collected on a continuous scale and then later categorized by level of concern, which followed CDC-suggested recommendations: not a level of concern (<5 μg/dL); slight level of concern, nutritional counseling recommended (5-9 μg/dL); and level of concern, further work warranted (>9 μg/dL).10

Predictor Variables

Our predictor variables included age (in years) at visit, poverty level (lowest, middle-low, middle-high, highest), sex (female, male), and ethnicity (Hispanic, non-Hispanic, unknown). We assessed poverty level by matching the patient’s residency zip codes to the percentage-under-poverty thresholds provided by the 2012-2016 ACS and then further categorized by the quartiles found in our sample: <13.2% (lowest [ie, least resource limited]), 13.2%-16.1% (middle-low), 16.2%-28.1% (middle-high), and >28.1% (highest [ie, most resource limited]). The lowest poverty level category means that <13.2% of the population in that zip code were living under the poverty threshold. We analyzed age at visit, our main predictor variable, both continuously and in age groups: early childhood (3-5 years), middle childhood (6-11 years), and adolescence and young adulthood (12-19 years), similarly to age groups used for pediatric trials.11

Statistical Analysis

We calculated frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and means and SDs for continuous variables to explore the distribution of a selected number of sociodemographic factors and BLLs. We fit univariate and multivariable regression models for continuous BLL to identify the differences in sociodemographic characteristics (age at visit, sex, ethnicity, poverty level) in our patient sample. We calculated unadjusted and adjusted estimated regression coefficients (β) along with 95% CIs for all predictors. We considered P < .05 significant. We performed data management and statistical analyses by using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc).

Results

Of our final sample of 1349 patients aged 3-19, most were aged 6-11 (n = 662, 49.1%) or 3-5 (n = 523, 38.8%; Table 1). A total of 421 (31.2%) patients resided in zip codes with the lowest poverty level (ie, least resource limited), and 333 (24.7%) patients resided in zip codes with the highest poverty level (ie, most resource limited). Most patients were Hispanic (n = 1082, 80.2%). The mean age (SD) at visit was 7.2 (3.5) years. About half (n = 673, 49.9%) of patients were female.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of recently arrived immigrant children, adolescents, and young adults aged 3-19 (N = 1349) who visited the University of Miami Pediatric Mobile Clinic, Florida, January 2, 2013, through December 31, 2016

| Variable | No. (%) (N = 1349) |

|---|---|

| Age group, y | |

| 3-5 | 523 (38.8) |

| 6-11 | 662 (49.1) |

| 12-19 | 164 (12.2) |

| Age at visit, y | |

| Mean (SD)a | 7.2 (3.5) |

| Median (25th%-75th%) | 6.0 (4.0-9.0) |

| Range | 3.0-19.0 |

| Sex | |

| Female | 673 (49.9) |

| Male | 676 (50.1) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic | 1082 (80.2) |

| Non-Hispanic | 239 (17.7) |

| Unknown | 28 (2.1) |

| Poverty levela | |

| Lowest | 421 (31.2) |

| Middle-low | 270 (20.0) |

| Middle-high | 325 (24.1) |

| Highest | 333 (24.7) |

| Lead or anemia diagnosis | |

| No | 1337 (99.1) |

| Yes | 12 (0.9) |

| Blood lead level of concernb | |

| Not a level of concern | 1296 (96.1) |

| Slight level of concern, nutritional counseling recommended | 38 (2.8) |

| Level of concern, further work warranted | 15 (1.1) |

| Blood lead level, μg/dL | |

| Mean (SD) | 3.3 (1.4) |

| Median (25th%-75th%) | 3.0 (3.0-3.0) |

| Range | 3.0-31.0 |

aPoverty level is based on quartiles found in the sample: least resource limited/lowest percentage of population living below the federal poverty threshold (<13.2%), middle-low (13.2%-16.1%), middle-high (16.2%-28.1%), and most resource limited/highest percentage of population living below the federal poverty threshold (>28.1%).9

bLess than 5 μg/dL, not a level of concern; 5-9 μg/dL, slight level of concern, nutritional counseling recommended; >9 μg/dL, level of concern, further work warranted.10

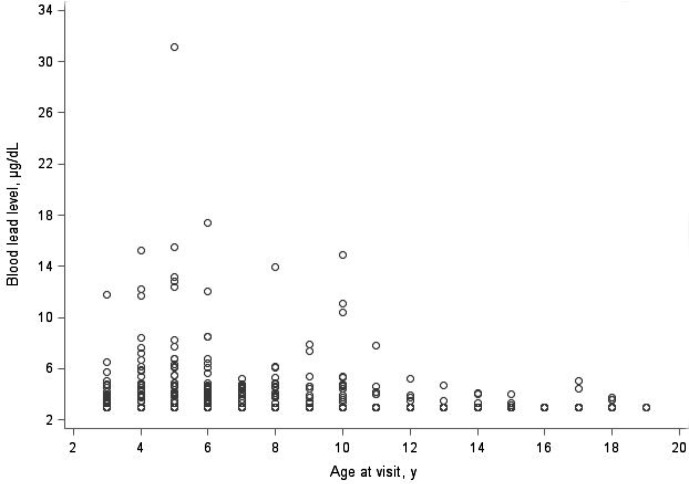

After an examination of diagnosis codes associated with the patients’ visits, most patients (n = 1337, 99.1%) did not have a diagnosis related to lead exposure or anemia (Table 1). Most patients (n = 1296, 96.1%) had a mean BLL that was no level of concern, 38 (2.8%) patients had a mean BLL of slight concern, and 15 (1.1%) patients had a mean BLL that warranted further work. The mean BLL was slightly higher among male patients (3.4 μg/dL) than among female patients (3.3 μg/dL; Figure; Table 2). Nine of the 15 patients with a BLL that warranted further work were aged 3-5, and 6 were aged 6-11 (Table 3). None of the adolescent and young adult patients aged 12-19 had a lead level of concern.

Figure.

Blood lead level of newly arrived immigrant children, adolescents, and young adults aged 3-19 (N = 1349) who visited the University of Miami Pediatric Mobile Clinic, by age at visit, Florida, January 1, 2013, through December 31, 2016.

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of newly arrived immigrant children, adolescents, and young adults aged 3-19 (N = 1349) who visited the University of Miami Pediatric Mobile Clinic, by age group and sex, Florida, January 1, 2013, through December 31, 2016a

| Demographic characteristic | All, no. (%) | Age group, y | Sex | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3-5 | 6-11 | 12-19 | Female | Male | ||

| Total | 1349 (100.0) | 523 (38.8) | 662 (49.1) | 164 (12.2) | 673 (49.9) | 676 (50.1) |

| Age group at visit, y | ||||||

| 3-5 | 523 (38.8) | 523 (100.0) | — | — | 261 (38.8) | 262 (38.8) |

| 6-11 | 662 (49.1) | — | 662 (100.0) | — | 320 (47.5) | 342 (50.6) |

| 12-19 | 164 (12.2) | — | — | 164 (100.0) | 92 (13.7) | 72 (10.7) |

| Age at visit, y | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 7.2 (3.5) | 4.1 (0.8) | 8.0 (1.6) | 14.3 (2.0) | 7.3 (3.6) | 7.1 (3.4) |

| Median (25th%-75th%) | 6.0 (4.0-9.0) | 6.0 (3.0-5.0) | 8.0 (6.0-9.0) | 14.0 (12.5-15.5) | 6.0 (4.0-9.0) | 6.0 (5.0-9.0) |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 673 (49.9) | 261 (49.9) | 320 (48.3) | 92 (56.1) | 673 (100.0) | — |

| Male | 676 (50.1) | 262 (50.1) | 342 (51.7) | 72 (43.9) | — | 676 (100.0) |

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| Hispanic | 1082 (80.2) | 408 (78.0) | 544 (82.2) | 130 (79.3) | 550 (81.7) | 532 (78.7) |

| Non-Hispanic | 239 (17.7) | 104 (19.9) | 108 (16.3) | 27 (16.5) | 109 (16.2) | 130 (19.2) |

| Unknown | 28 (2.1) | 11 (2.1) | 10 (1.5) | 7 (4.3) | 14 (2.1) | 14 (2.1) |

| Poverty levelb | ||||||

| Lowest | 421 (31.2) | 167 (31.9) | 214 (32.3) | 40 (24.4) | 211 (31.4) | 210 (31.1) |

| Middle-low | 270 (20.0) | 115 (22.0) | 131 (19.8) | 24 (14.6) | 133 (19.8) | 137 (20.3) |

| Middle-high | 325 (24.1) | 113 (21.6) | 161 (24.3) | 51 (31.1) | 155 (23.0) | 170 (25.1) |

| Highest | 333 (24.7) | 128 (24.5) | 156 (23.6) | 49 (29.9) | 174 (25.9) | 159 (23.5) |

| Lead or anemia diagnosis | ||||||

| No | 1337 (99.1) | 516 (98.7) | 658 (99.4) | 163 (99.4) | 670 (99.6) | 667 (98.7) |

| Yes | 12 (0.9) | 7 (1.3) | 4 (0.6) | 1 (0.6) | 3 (0.4) | 9 (1.3) |

| Blood lead level of concernc | ||||||

| Not a level of concern | 1296 (96.1) | 494 (94.5) | 640 (96.7) | 162 (98.8) | 651 (96.7) | 645 (95.4) |

| Slight level of concern, nutritional counseling recommended | 38 (2.8) | 20 (3.8) | 16 (2.4) | 2 (1.2) | 18 (2.7) | 20 (3.0) |

| Level of concern, further work warranted | 15 (1.1) | 9 (1.7) | 6 (0.9) | 0 | 4 (0.6) | 11 (1.6) |

| Blood lead level, μg/dL | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 3.3 (1.4) | 3.5 (1.9) | 3.3 (1.2) | 3.1 (0.3) | 3.3 (1.0) | 3.4 (1.8) |

| Median (25th%-75th%) | 3.0 (3.0-3.0) | 3.0 (3.0-3.0) | 3.0 (3.0-3.0) | 3.0 (3.0-3.0) | 3.0 (3.0-3.0) | 3.0 (3.0-3.0) |

| Range | 3.0-31.1 | 3.0-31.1 | 3.0-17.4 | 3.0-5.2 | 3.0-13.9 | 3.0-31.1 |

aAll values are no. (%) unless otherwise indicated.

bPoverty level is based on quartiles found in the sample: least resource limited/lowest percentage of population living below the federal poverty threshold (<13.2%), middle-low (13.2%-16.1%), middle-high (16.2%-28.1%), and most resource limited/highest percentage of population living below the federal poverty threshold (>28.1%).9

cLess than 5 μg/dL = not a level of concern; 5-9 μg/dL = slight level of concern, nutritional counseling recommended; >9 μg/dL = level of concern, further work warranted.10

Table 3.

Demographic characteristics of newly arrived immigrant children, adolescents, and young adults aged 3-19 (N = 1349) who visited the University of Miami Pediatric Mobile Clinic, by blood lead level of concern, Florida, January 1, 2013, through December 31, 2016a

| Demographic variable | All | Blood lead level of concernb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not a level of concern |

Slight level of concern, nutritional counseling recommended |

Level of concern, further work warranted |

||

| All | 1349 (100.0) | 1296 (96.1) | 38 (2.8) | 15 (1.1) |

| Age group at visit, y | ||||

| 3-5 | 523 (38.8) | 494 (38.1) | 20 (52.6) | 9 (60.0) |

| 6-11 | 662 (49.1) | 640 (49.4) | 16 (42.1) | 6 (40.0) |

| 12-19 | 164 (12.2) | 162 (12.5) | 2 (5.3) | 0 |

| Age at visit, y | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 7.2 (3.5) | 7.3 (3.5) | 6.3 (2.9) | 6.0 (2.4) |

| Median (25%-75%) | 6.0 (4.0-9.0) | 6.0 (4.5-9.0) | 5.0 (4.0-8.0) | 5.0 (4.0-8.0) |

| Range | 3.0-19.0 | 3.0-19.0 | 3.0-17.0 | 3.0-10.0 |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 673 (49.9) | 651 (50.2) | 18 (47.4) | 4 (26.7) |

| Male | 676 (50.1) | 645 (49.8) | 20 (52.6) | 11 (73.3) |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Hispanic | 1082 (80.2) | 1053 (81.3) | 20 (52.6) | 9 (60.0) |

| Non-Hispanic | 239 (17.7) | 215 (16.6) | 18 (47.4) | 6 (40.0) |

| Unknown | 28 (2.1) | 28 (2.2) | 0 | 0 |

| Poverty levelc | ||||

| Lowest | 421 (31.2) | 411 (31.7) | 9 (23.7) | 1 (6.7) |

| Middle-low | 270 (20.0) | 268 (20.7) | 0 | 2 (13.3) |

| Middle-high | 325 (24.1) | 312 (24.1) | 10 (26.3) | 3 (20.0) |

| Highest | 333 (24.7) | 305 (23.5) | 19 (50.0) | 9 (60.0) |

| Lead or anemia diagnosis | ||||

| No | 1337 (99.1) | 1287 (99.3) | 36 (94.7) | 14 (93.3) |

| Yes | 12 (0.9) | 9 (0.7) | 2 (5.3) | 1 (6.7) |

| Blood lead level, μg/dLb | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 3.3 (1.4) | 3.1 (0.4) | 6.4 (1.1) | 14.4 (5.0) |

| Median (25%-75%) | 3.0 (3.0-3.0) | 3.0 (3.0-3.0) | 6.2 (5.5-7.2) | 12.8 (11.8-15.2) |

| Range | 3.0-31.1 | 3.0-4.9 | 5.0-8.5 | 10.4-31.1 |

aAll values are no. (%) unless otherwise indicated.

bLess than 5 μg/dL = not a level of concern; 5-9 μg/dL = slight level of concern, nutritional counseling recommended; >9 μg/dL = level of concern, further work warranted.10

cPoverty level is based on quartiles found in the sample: least resource limited/lowest percentage of population living below the federal poverty threshold (<13.2%), middle-low (13.2%-16.1%), middle-high (16.2%-28.1%), and most resource limited/highest percentage of population living below the federal poverty threshold (>28.1%).9

Regression Models

The univariate regression model found a significant relationship between BLLs and age at visit (β = –0.026; 95% CI, –0.048 to –0.004; P = .02; Table 4). We found a significant negative association between age group and BLLs when we compared adolescents and young adults aged 12-19 with children aged 3-5 (β = –0.355; 95% CI, –0.608 to –0.102; P = .01). We found a significant negative association between age at visit (years) and BLLs that continued after adjusting for the previously mentioned variables (β = –0.028; 95% CI, –0.050 to –0.006; P = .01). We also found a significant association between BLL and age group among children living in the highest poverty level compared with children living in the lowest poverty level (β = 0.507; 95% CI, 0.296 to 0.719; P < .001).

Table 4.

Univariate and multivariable linear regression models for blood lead levels (μg/dL) of newly arrived immigrant children, adolescents, and young adults aged 3-19 (N = 1349) who visited the University of Miami Pediatric Mobile Clinic, Florida, January 1, 2013, through December 31, 2016a

| Model/variable | βb (95% CI) [P valuec] |

|---|---|

| Model 1 | |

| Age at visit, y | –0.023 (–0.049 to –0.004) [.02] |

| Model 2 | |

| Age group at visit, y | |

| 3-5 | 1 [Reference] |

| 6-11 | –0.150 (–0.315 to 0.016) [.08] |

| 12-19 | –0.355 (–0.608 to –0.102) [.01] |

| Model 3 | |

| Age at visit, y | –0.028 (–0.050 to –0.006) [.01] |

| Sex | |

| Male | 1 [Reference] |

| Female | –0.135 (–0.287 to 0.017) [.08] |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic | 1 [Reference] |

| Non-Hispanic | 0.322 (0.111 to 0.533) [.003] |

| Unknown | –0.167 (–0.731 to 0.397) [.56] |

| Poverty leveld | |

| Lowest | 1 [Reference] |

| Middle-low | –0.009 (–0.226 to 0.208) [.94] |

| Middle-high | 0.106 (–0.110 to 0.321) [.34] |

| Highest | 0.508 (0.297 to 0.720) [<.001] |

| Model 4 | |

| Age group at visit, y | |

| 3-5 | 1 [Reference] |

| 6-11 | –0.141 (–0.304 to 0.022) [.09] |

| 12-19 | –0.373 (–0.624 to –0.121) [.004] |

| Sex | |

| Male | 1 [Reference] |

| Female | –0.132 (–0.284 to 0.020) [.09] |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic | 1 [Reference] |

| Non-Hispanic | 0.318 (0.106 to 0.529) [.003] |

| Unknown | –0.148 (–0.712 to 0.417) [.61] |

| Poverty leveld | |

| Lowest | 1 [Reference] |

| Middle-low | –0.010 (–0.227 to 0.207) [.93] |

| Middle-high | 0.113 (–0.102 to 0.329) [.30] |

| Highest | 0.507 (0.296 to 0.719) [<.001] |

aEach row is a separate regression model. Model 1: Univariate regression model with age at visit as a continuous predictor of blood lead level (BLL). Model 2: Univariate regression model with categorized age at visit predictor. Model 3: Multivariable regression model with age at visit (continuous), sex, ethnicity, and poverty level as predictors on BLL. Model 4: Multivariable regression model with age at visit (categorical), sex, ethnicity, and poverty level as predictors of BLL.

bUnstandardized estimated regression coefficient for the corresponding variable in the row.

cUsing 2-tailed tests of significance, with P < .05 considered significant.

dPoverty level is based on quartiles found in the sample: least resource limited/lowest percentage of population living below the federal poverty threshold (<13.2%), middle-low (13.2%-16.1%), middle-high (16.2%-28.1%), and most resource limited/highest percentage of population living below the federal poverty threshold (>28.1%).9

This retrospective study aimed to identify a relationship between age and BLL among newly arrived immigrant children to the United States. Although CDC recommends screening refugee children for elevated BLLs through age 16, no guidelines exist for newly arrived immigrant children. Understanding the relationship between age and BLL is particularly relevant because lead testing for children and adolescents can be costly for newly arrived immigrant families, who typically do not have financial resources or health insurance. Furthermore, the current CDC recommendations are for refugees, who, by definition, are people who have been approved to enter the United States and are connected to funded medical services upon entry. No CDC guidelines for lead screening exist for newly arrived immigrant children with unknown legal status. The patients in our study population, by definition, were immigrants rather than refugees. Although these 2 terms are often used interchangeably, they are different.

Our retrospective analysis revealed that no children, adolescents, or young adults aged 12-19 were in the highest category of concern for lead toxicity. Most children with the highest level of concern for elevated BLLs were aged 3-5. This evidence does not support the current CDC recommendations of testing all newly arrived refugee nor immigrant children up to age 16. Furthermore, we found a significant relationship between BLLs and age at visit, and this relationship persisted even when adjusting for poverty level, ethnicity, and sex.

Testing every newly arrived immigrant child and adolescent through 16 years of age can be burdensome, from both a financial and time perspective, for clinicians, patients, and patients’ families. For practices caring for uninsured patients, absorbing the expense of these tests can be cost prohibitive, especially when the yield of a positive test is low for adolescent patients. Furthermore, if a clinic does not provide testing on site, patients have to pay for the venous blood test and would be required to travel to a laboratory to obtain the test. In addition, children may miss school and parents may miss work, resulting in lost wages, which is particularly troublesome for immigrant families. According to a 2010-2011 report, approximately 47.2% of immigrants and their families in the United States were living in or near poverty.12 This percentage matched our study population because nearly half lived in zip codes of middle to highest levels of poverty. Nationally, on average, immigrant families made approximately $7000 less per-person median household income than US-born families.12 Also, transportation is often limited for these families; therefore, traveling to an outside laboratory could be a barrier to testing.

Limitations

Our study had several limitations. It was geographically limited to Miami-Dade County, which was problematic for 2 reasons. One, the immigrant population in Miami-Dade County may be exposed to both pre-entry and postarrival risks that differ from other geographic areas in the United States. Most of our sample identified as Hispanic, and most patients at PMC originated from Venezuela, Nicaragua, and Honduras. However, other counties in Florida have a higher number of non-Hispanic immigrants from countries such as Afghanistan, Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Iraq, and the risk factors for lead exposure in these countries could be different from lead exposure in South American countries.13

Two, it is likely that the risks of developing an elevated BLL while residing in Miami-Dade County are different—either higher or lower—than other regions in the United States. For example, research based on studies in Massachusetts and New Hampshire suggests that many refugee children are exposed to lead after their resettlement to the United States, presumably because of poor housing conditions and environmental factors; however, this exposure risk might not be the case for every city, county, or state.6,8 Also, most of our study patients did not have refugee status; therefore, this immigrant population may have unique circumstances that warrant a different approach to lead screening, such as taking into consideration country of origin and age of arrival to the United States.

Conclusions

This retrospective analysis provides evidence that BLL testing up to age 16 may not be an appropriate age recommendation for universal lead screening guidelines for newly arrived immigrant children, as is the case for refugee children. In our study, BLLs among adolescents and young adults aged >11 were either of slight concern or of no concern. Our results provide a foundation for future studies, which should elucidate appropriate age ranges based on epidemiologic evidence of the occurrence of lead toxicity for populations of children, adolescents, and young adults. Given limitations related to country of origin or resettlement location, as well as circumstances surrounding immigrant vs refugee children in access to appropriate medical care, future studies could expand to other counties in Florida or nationwide while controlling for country of origin. Future studies should include and focus on compiling data to create a list for countries of origin with a high risk for pre-entry elevated BLL and the regions in the United States that have recorded an increased risk of BLL. This information may affect future recommendations for pediatric lead testing for all types of immigrants through 16 years of age.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The Pediatric Mobile Clinic received financial support from The Children’s Health Fund.

ORCID iD

Lisa Gwynn, DO, MBA https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2857-376X

References

- 1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health Lead: information for workers. Published April 2017. Accessed January 7, 2020 https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/lead/health.html#4

- 2. Council on Environmental Health Prevention of childhood lead toxicity. Pediatrics. 2016;138(1):pii:e20161493. 10.1542/peds.2016-1493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. American Academy of Pediatrics Detection of lead poisoning. Published 2016. Accessed January 7, 2020 https://www.aap.org/en-us/advocacy-and-policy/aap-health-initiatives/lead-exposure/Pages/Detection-of-Lead-Poisoning.aspx

- 4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Immigrant and Refugee Health Screening for lead during the domestic medical examination for newly arrived refugees. Published October 2013. Accessed January 7, 2020 https://www.cdc.gov/immigrantrefugeehealth/guidelines/lead-guidelines.html

- 5. Zabel EW., Smith ME., O’Fallon A. Implementation of CDC refugee blood lead testing guidelines in Minnesota. Public Health Rep. 2008;123(2):111-116. 10.1177/003335490812300203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Lead poisoning prevention in newly arrived refugee children: tool kit. Published 2016. Accessed January 7, 2020 https://www.cdc.gov/nceh/lead/publications/refugeetoolkit/refugee_tool_kit.htm

- 7. Geltman PL., Brown MJ., Cochran J. Lead poisoning among refugee children resettled in Massachusetts, 1995 to 1999. Pediatrics. 2001;108(1):158-162. 10.1542/peds.108.1.158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kellenberg J., DiPentima R., Maruyama M. et al. Elevated blood lead levels in refugee children—New Hampshire, 2003-2004 [published correction appears in MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2005;54(3):76]. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2005;54(2):42-46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. US Census Bureau American Community Survey. Accessed January 7, 2020 https://www.census.gov/history/www/programs/demographic/american_community_survey.html

- 10. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Lead. Published March 26, 2018. Accessed January 7, 2020 https://www.cdc.gov/nceh/lead/data/blood-lead-reference-value.htm

- 11. Williams K., Thomson D., Seto I. et al. Standard 6: age groups for pediatric trials. Pediatrics. 2012;129(suppl 3):S153-S160. 10.1542/peds.2012-0055I [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Camarota SA. Immigrants in the United States: a profile of America’s foreign-born population. Published August 8, 2012. Accessed April 29, 2020 https://cis.org/Report/Immigrants-United-States-2010

- 13. Department of Children and Families. Refugee Services Program State of Florida: top origins by county, federal fiscal year 2018, October 1, 2017–September 30, 2018. Published February 4, 2019. Accessed January 7, 2020 https://www.myflfamilies.com/service-programs/refugee-services/reports/2018/Pdf/2018Pop4AllCountiesbyTopOrigins.pdf