Abstract

Objectives

Rural communities in the United States are increasingly becoming epicenters of substance use and related harms. However, best practices for recruiting rural people who use drugs (PWUD) for epidemiologic research are unknown, because such strategies were developed in cities. This study explores the feasibility of web- and community-based strategies to recruit rural, young adult PWUD into epidemiologic research.

Materials and Methods

We recruited PWUD from rural Kentucky to participate in a web-based survey about opioid use using web-based peer referral and community-based strategies, including cookouts, flyers, street outreach, and invitations to PWUD enrolled in a concurrent substance use study. Staff members labeled recruitment materials with unique codes to enable tracking. We assessed eligibility and fraud through online eligibility screening and a fraud detection algorithm, respectively. Eligibility criteria included being aged 18-35, recently using opioids to get high, and residing in the study area.

Results

Recruitment yielded 410 complete screening entries, of which 234 were eligible and 151 provided complete, nonfraudulent surveys (ie, surveys that passed a fraud-detection algorithm designed to identify duplicate, nonlocal, and/or bot-generated entries). Cookouts and subsequent web-based peer referrals accounted for the highest proportion of screening entries (37.1%, n = 152), but only 29.6% (n = 45) of entries from cookouts and subsequent web-based peer referrals resulted in eligible, nonfraudulent surveys. Recruitment and subsequent web-based peer referral from the concurrent study yielded the second most screening entries (27.8%, n = 114), 77.2% (n = 88) of which resulted in valid surveys. Other recruitment strategies combined to yield 35.1% (n = 144) of screening entries and 11.9% (n = 18) of valid surveys.

Conclusions

Web-based methods need to be complemented by context-tailored, street-outreach activities to recruit rural PWUD.

Keywords: substance use, injection drug use, rural, recruitment, opioids, web-based survey

Rural communities in the United States, particularly communities in Appalachia, are increasingly recognized as epicenters of substance use and drug-related harms, fueled by opioid injection, syringe sharing, and a historically weak harm-reduction infrastructure.1,2 Although communities across the rural–urban continuum have been affected by opioid use and related harms, nonmedical prescription opioid use and heroin use have increased dramatically among young adults in rural areas, particularly in Central Appalachia and Kentucky.3-8 In a ranking of US counties’ vulnerability to outbreaks of HIV and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection among people who inject drugs, 43 of the 54 counties that comprise Appalachian Kentucky ranked in the top 5%.9 The incidence of newly diagnosed HCV infection is now higher among young adults in rural areas than in any other US population.10-12

Despite decades of evidence indicating the need for more research on substance use in rural settings, epidemiologic research and methods development have struggled to keep pace. Although innovative methods have been developed and implemented to recruit people who use drugs (PWUD), most methods were created for and implemented in cities and may not succeed in rural areas.13-16 For example, targeted sampling, respondent-driven sampling (RDS), and other methods used to recruit PWUD are most effective when population densities are high, applicable service providers are readily present, and public transportation is accessible.13-16 Small population size, challenges with transportation, fear of stigma, lack of anonymity, and complex cultural dynamics can create barriers in identifying, recruiting, and collecting data from active, not-in-treatment PWUD living in rural areas.17-19

Novel methods for recruitment, particularly among rural young adults, warrant exploration. For example, RDS has been used successfully to recruit samples of rural PWUD by leveraging peer relationships20-22; however, these studies did not focus explicitly on young adults, a population with a high prevalence of opioid-related harms in rural areas. RDS is a sampling technique involving the recruitment of index participants (ie, “seeds”) who are given a limited number of printed coupons to refer their peers, who are in turn asked to refer their peers, and so on until the target sample size is reached.14 However, this traditional form of RDS can be logistically complex and expensive and requires printed recruitment coupons, administrative support for coupon tracking, and local study offices.

Alternatively, web-based RDS (WebRDS) is an effective, low-cost method to recruit hard-to-reach populations in cities.23-29 WebRDS is identical to traditional RDS, except it uses e-coupons via text, email, or social media instead of paper coupons distributed in person.25,28 Studies show that web-based methods can be used to recruit hidden populations, including men who have sex with men, people who have tested positive for sexually transmitted infections, people who use marijuana, and young adults.23-29 Web-based methods, including WebRDS, have the potential to eliminate logistical barriers in rural areas that present challenges with other strategies. However, web-based recruitment and data collection have not been tested among rural PWUD.

High rates of internet use among rural adults30 indicate that web-based methods may be feasible, but the feasibility of WebRDS among rural PWUD is unknown. The objectives of our study were to examine the following: (1) which web- and community-based recruitment methods are most successful in enrolling rural, young adult PWUD into an online survey about substance use and sexual risk behavior, considering 2 dimensions of research method success: number screened and efficiency (ie, number eligible among those screened), and (2) to what extent rural, young adult PWUD will use web-based referral to recruit peers to participate.

Methods

The study team recruited young people who use opioids to get high from August 27, 2017, to August 3, 2018, from 5 rural counties in Appalachian Kentucky to participate in a web-based survey about their sexual and drug-related risk behaviors. Three of the 5 counties rank in the top 5% nationally in vulnerability to an outbreak of HIV and hepatitis C infection among people who inject drugs.9 According to the 2013 Rural–Urban Continuum Codes31 and 2010 US Census,32 all 5 counties were classified as nonmetropolitan and/or rural.

Participant eligibility criteria included being aged 18-35, living in the study area, and having used opioids to get high in the past 30 days. The study focused on opioids in response to the increase in opioid-related overdose deaths in Kentucky. People who were deemed eligible via the online eligibility screening tool (described in detail elsewhere33) were directed to an online survey programmed in Surveygizmo (surveygizmo.com) after completing an online consent form. The survey queried drug use, sexual behavior, drug-related harms, and access to substance use treatment and harm-reduction services. Participants received $30 for participation.

Recruitment Methods for WebRDS Seeds

Recruitment of index participants (ie, seeds) for the WebRDS strategy occurred through several outreach strategies (Table), including distribution of flyers by staff members during project cookouts and walks through neighborhoods (ie, street outreach), postings in community venues, postings by staff members at a field office used for a concurrent substance use study (CARE2HOPE), and postings by community coalition members (eg, local stakeholders). Staff members labeled all recruitment materials with a unique code; people were required to enter this code into online eligibility screening surveys to initiate the screener, allowing staff members to track how participants were recruited. We attempted to use Facebook, Craigslist, and local newspaper advertisements during a previous phase of the study involving qualitative data collection, but efforts were unsuccessful in yielding participants and were therefore not used in the online survey phase. Furthermore, we were concerned that online advertisements would increase the vulnerability to fraud (ie, people from outside the study area attempting to participate).

Table.

Recruitment strategies for seeds to initiate web-based peer referral in a study of young adults aged 18-35 who use opioids in rural Appalachia, 2017-2018

| Recruitment method | Description | Locations | Timing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cookouts | Staff members held 6 cookouts in public locations, offered free food and drinks, passed out flyers, and described the study to passersby and store patrons. Cookouts were held on weekends and weekdays in mid-morning and afternoon and lasted 2-5 h. Cookouts were held under a pop-up tent, and a large banner announced the study. | Parking lots of gas stations and grocery stores in neighborhoods identified by local partners as having high rates of drug-related harms (eg, overdoses) | August 2017–April 2018 |

| Neighborhood walks | Staff members wearing university clothing walked through neighborhoods and talked with people about the study or left flyers at residences. | Mobile home parks and apartment complexes identified by local partners as having high rates of drug-related harms (eg, overdoses) | August 2017–April 2018 |

| Flyers | Staff members posted flyers at community venues that local stakeholders suggested were frequented by young people who use drugs. Staff members restocked flyers monthly, bimonthly, or quarterly, depending on traffic at venue. | 134 venues, including health departments, substance use disorder treatment centers, social service agencies, and business venues (eg, gas stations, laundromats, cash advance stores, pawn shops, vapor and tobacco shops, hair salons, restaurants) | August 2017–July 2018 |

| Field office | Participants aged 18-35 who had enrolled in a different local study of people who use drugs recruited through traditional respondent-driven sampling and who had consented to be contacted for future research were invited to participate in the online survey after their appointment in the local field office. | Local storefront field office in center of largest town in the study catchment area, along a public bus route and near the health department | February 2018–July 2018 |

| Community coalitions | Approximately 15 coalition members were provided with flyers to distribute and/or to post in their venues. | Not applicable | Approximately March 2018–July 2018 |

Cookouts

We held cookouts as low-threshold (ie, easily accessible, not intimidating) events in which community members, including but not limited to PWUD, could join study staff members for a meal, so that the principal investigators and staff members could build relationships with community members on their own terms and learn about the project. In an area where research was relatively new, cookouts allowed community members to choose whether to engage with the project team. Staff members spoke with passersby and store patrons, offered them free food and drinks, passed out flyers, and described the study. All visitors, whether eligible or not, were welcome to eat and speak with staff members. Staff members established a rapport with community members through casual conversation during cookouts, and community members who attended the cookout often informed others about the project. Typically, within a few hours, eligible community members (ie, young adults who use opioids to get high) would visit the cookout and complete the online survey on study-provided tablets or telephones.

Neighborhood walks

Staff members walked through neighborhoods that local partners suggested as having high rates of drug-related harms (eg, overdoses). Most neighborhoods were mobile home parks varying in size from approximately 5 homes to more than 50 homes; some neighborhoods were small apartment complexes housing 20-100 residents. Research staff members called landlords to request permission to distribute flyers.

Community venues

The study team posted flyers in 134 venues (Table). Flyers posted in venues had pull-tabs with study contact information; at the suggestion of local partners, staff members removed a few pull tabs when they hung flyers to help normalize it. Staff members attempted to recruit participants for the qualitative phase of the study that preceded the online survey phase by installing small yard signs, but yard signs were removed frequently by roadside mowing crews; therefore, we did not use them for survey recruitment.

Field office

The CARE2HOPE field office was staffed by community-based personnel who conduct interviewer-administered surveys among adults aged ≥18 who had used opioids and/or injected any drug to get high in the past 30 days. CARE2HOPE participants are recruited from the same 5 counties included in the present study using traditional RDS. Staff members invited CARE2HOPE participants who consented to be contacted for future research to participate when they visited the office.

Community coalitions

The CARE2HOPE study convened community–academic partnership groups composed primarily of local stakeholders from health agencies, substance use disorder treatment agencies, and social service agencies; leaders from faith-based organizations; and people in recovery from substance use disorder. The study team provided coalition members with flyers to distribute or post in their venues and/or give to clients who may be interested.

Web-Based Peer Referral

The online survey asked, “Would you like to help us recruit new people to take part in the study? Recruiters receive $10 for each person they recruit who is eligible and completes the survey, and you can recruit up to 3 participants into the study.” The survey gave participants who said yes instructions on how and who to recruit and asked whether they wanted to receive their e-coupon via text message and/or email. E-coupons included an invitation to participate, a unique referral code, a URL for the screener, and study contact information.

Peers entered the unique coupon codes at the beginning of the screening; staff members used the codes to link participants and their recruits. Participants could refer an unlimited number of peers but were only reimbursed for up to 3 referrals.

Analysis

Fraud detection

Fraud is a well-established threat to validity in web-based research34 and, therefore, staff members evaluated entries both during and after data collection. During data collection, 49 surveys were completed within two 24-hour periods, and all of these entries requested incentives be mailed to the same address. Once staff members verified that the address was not capable of housing that many people, staff members flagged data as possibly fraudulent (ie, the same person[s] attempting to complete the survey multiple times) and contacted participants who were using that address for verification. Initially, staff members did not withhold compensation from fraudulent entries because the consent form did not describe that possibility. However, the study team made changes to the consent form after the initial uptick in fraud to allow payment to be withheld. Thereafter, staff members contacted participants suspected of fraud to inform them that their entry was flagged and to request they contact staff members to verify their entry to receive compensation, although none did. Staff members identified an additional 18 entries as fraudulent using strategies (described elsewhere35) that were informed by a fraud-detection algorithm used previously in online research.36 Staff members identified these entries after data collection had ended; as such, these participants were not contacted. Demographic and behavioral characteristics of the final valid sample (n = 151) are described elsewhere.35

Recruitment method yield and peer referral

We used SPSS version 25 (IBM Corp) to calculate descriptive statistics of the numbers of online screening survey entries, eligible entries, and complete and nonfraudulent eligible surveys for each recruitment method. We used UCINET version 6.664 (Analytic Technologies) and Netdraw version 2.166 (Analytic Technologies) to construct and visualize the web-based peer-referral chains.

The Emory University Institutional Review Board approved all study procedures, and data were protected by a Federal Certificate of Confidentiality.

Results

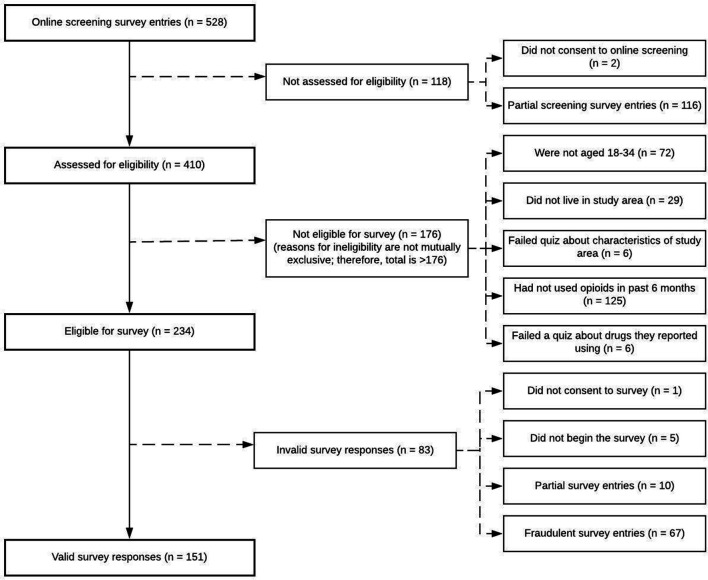

Recruitment efforts yielded 410 complete online eligibility screening entries, 234 of which were deemed eligible. Of 234 entries that were eligible, 83 entries were invalid (67 were fraudulent and 16 were only partially complete), leaving 151 (64.5%) valid entries (ie, complete and nonfraudulent; Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Eligibility of screening entries among young adults aged 18-35 who use opioids to get high for an online survey about substance use, rural Appalachia, 2017-2018.

Yield of Recruitment Strategies

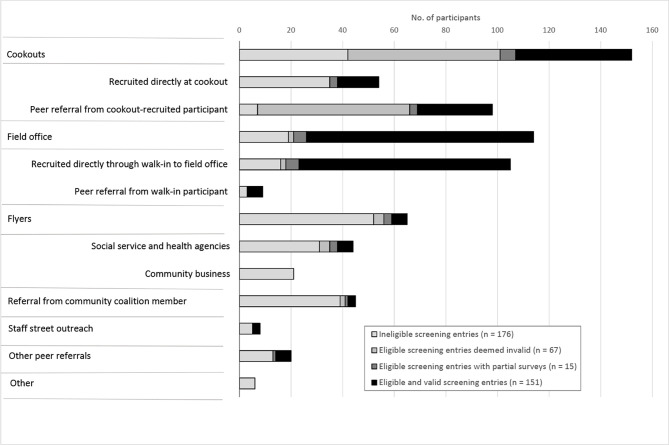

Project cookouts were the most effective strategy in generating entries into the screening process (Figure 2). A total of 54 people, or an average of 9 people per cookout, completed the eligibility screening survey at the event (range, 3-23). People recruited from cookouts generated 98 additional screening entries through peer referral. In total, of the 410 completed online screening entries, 152 (37.1%) were attributable to cookouts or referrals from people recruited at cookouts. However, staff members determined that 65 (42.8%) of the 152 entries from people recruited via cookouts or their peer referrals were fraudulent. The efficiency (ie, percentage of screening entries that met eligibility criteria) of direct recruitment at cookouts was low (35.2%; 19 of 54 people recruited directly at cookouts were eligible), but few (3 of 19) eligible participants were fraudulent. The efficiency of peer referrals from cookout participants was high (92.9%; 91 of 98 peer referrals were eligible); however, 62 of 91 (68.1%) eligible participants were deemed fraudulent. In total, 45 of 151 (29.8%) entries from the final sample were directly or indirectly attributable to the 6 recruitment cookouts (ie, an average yield of approximately 7.5 valid and eligible survey entries per cookout).

Figure 2.

Strategies used to recruit young adults aged 18-35 who use opioids to get high for an online survey about substance use, rural Appalachia, 2017-2018. Social service and health agencies include health departments, substance use disorder treatment centers, social service organizations, medical clinics, and a criminal justice facility. Community businesses include gas stations, laundromats, cash advance stores, pawn shops, vape and tobacco shops, hair salons, department store community bulletin boards, and restaurants. Other peer referrals include referred by peers who were recruited through community coalition members or flyers distributed by staff members at medical clinics. Other includes religious organizations, residential areas (apartment complexes), community events (July 4 event), and contacted staff members via email address posted on study website.

Recruitment from the CARE2HOPE field office and subsequent peer referrals combined to be the second most effective method in generating entries into the online screening process and yielding eligible entries, accounting for 114 (27.8%) of 410 total screening entries and 95 of 234 (40.6%) eligible entries, most (92.6%, n = 88) of which were complete and nonfraudulent. Thus, most (58.3%; 88 of 151) of the final, valid sample was directly or indirectly attributable to recruitment from the CARE2HOPE study.

Other recruitment strategies including flyers posted in traditional and nontraditional community venues and referrals from community partners yielded a small proportion (18 of 151, 11.9%) of the final sample, including peer referrals. Most screening entries from these strategies were ineligible.

Web-Based Peer Referral

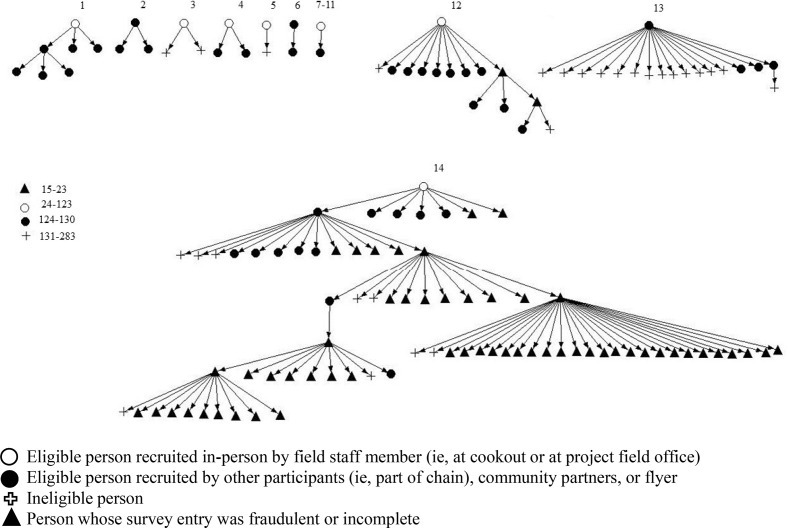

Of 120 participants who agreed to help recruit peers, 107 (89.2%) reported knowing at least 1 young adult who used opioids in the target area, but only 24 (20.0%) referred a peer to the study. Of 119 seeds, only 14 started a peer-referral chain (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Web-based peer referral chains involved in recruiting young adults aged 18-35 who use opioids to get high for an online survey about substance use, rural Appalachia, 2017-2018. The figure includes unique identification numbers next to each “seed” participant who began a chain and those who are isolates (ie, who did not begin a chain and were not referred by others) to allow for enumeration of chain and isolate types.

Ten participants referred ≥3 people, 4 referred 2 people, and 10 referred 1 person. Of the 83 participants whose surveys were fraudulent or incomplete, 49 (59.0%) used a referral code from someone who also was classified as having a fraudulent or incomplete survey. We found 5 instances in which participants with fraudulent or incomplete surveys referred people into the study who completed valid surveys.

Demographic and Behavioral Characteristics of Sample

In the final sample (n = 151), the average age of participants was 29, most (n = 93, 61.6%) were male, 146 (96.7%) were white, 149 (98.7%) were non-Hispanic, and 102 (67.5%) had completed high school or a general educational development. Most (n = 107, 70.9%) participants lacked transportation (ie, were unable to do something that they needed to because they did not have a way to get there), and 68 (45.0%) had been homeless (ie, living on the street or in a car, park, abandoned building, or shelter) in the past 6 months. Most (n = 114, 75.5%) reported accessing the internet daily, 24 (15.9%) weekly, and 8 (5.3%) at least once in the past 6 months. Only 2 participants reported not accessing the internet at all in the past 6 months.

The most frequently reported opioids used to get high in the past 6 months were heroin (n = 109, 72.2%), followed by buprenorphine or methadone (n = 92, 60.9%), and prescription pain pills (n = 78, 51.7%). In addition, 89 (58.9%) reported methamphetamine use. Most participants (n = 115, 76.2%) reported that they had injected drugs to get high in their lifetime, and 100 (66.2%) had injected drugs in the past 6 months.

Discussion

Best practices for recruiting PWUD in rural areas for epidemiologic research, particularly online research, are not known. This study explored the feasibility of using various outreach and web-based peer-referral strategies to recruit young adults who use opioids in rural Central Appalachia. Although web-based recruitment methods have been used successfully to recruit hard-to-reach urban populations, our study found that web-based methods need to be complemented by a local field office and/or by context-specific, street-outreach activities to recruit people in rural areas who use opioids.

Cookouts, field office recruitment, and related peer referrals accounted for 88% of the final sample. This study provides evidence that internet access and use, which were prevalent in this sample, are necessary but potentially insufficient in isolation to support web-based research among young adults in rural areas who use opioids. Similarly, flyer-based advertisements in community venues yielded few eligible participants despite a large investment of personnel time and travel resources required to post and restock flyers. In this rural setting, participants’ personal or peer contact with study staff members through cookouts and in field offices were critical to successful recruitment. Anecdotal evidence and feedback from field staff members suggest that personal contact with participants increased rapport, trust, and perceptions of study legitimacy and could have contributed to recruitment success. However, further qualitative research is needed to fully understand reasons for the success of cookouts and field office–based recruitment strategies.

Cookouts yielded the most online screening entries, and although many respondents’ entries were ineligible, participant entries that were eligible led to the successful recruitment of many eligible people through peer referral. Although research has highlighted the centrality of cookouts to rural culture, particularly among low-income families,37 few studies cite the use of cookouts in research in rural areas. Cookouts have been used in research in rural settings to show appreciation or offer social gatherings for participants38,39 and have been suggested by participants in rural areas as a potentially useful recruitment strategy.40 However, they are underused as a recruitment method in rural research. Of note, cookouts seemed to have additional, unanticipated, positive effects. Community members who were not using drugs and who would therefore rarely have an opportunity to interact with staff members become acquainted with staff members and shared valuable insights about the community context. Community partners who staffed the local syringe services program also attended portions of the cookouts, which gave community members an opportunity to learn about the program. Finally, the cookouts seemed to contribute to team-building among staff members, to boost morale when they heard community members express appreciation for the team’s desire to improve health in their community, and to increase staff member comfort in interacting with participants and community members in community settings.

Peer referrals from people who attended cookouts yielded a high number of eligible entries, but a few entries led to peer-referral chains that were later identified as cul-de-sacs of fraud (ie, fraudulent participants attempting to refer ineligible people into the study or to reenroll themselves into the study by sending themselves the peer referral code but at a different email address to avoid detection by staff members). Although these referrals appeared to result in referral chains of fraud in which fraudulent people referred many other fraudulent people, the data should be interpreted with caution because chains may be a product of fraudulent participants attempting to refer themselves into the study (ie, sending themselves the referral code but at a different email address to avoid detection by staff members). In total, the fraud detection algorithm detected 67 cases of fraud, accounting for 28.6% of entries that screened eligible. However, 80% of these cases were attributable to an individual or to a small group of people residing in 1 location who repeatedly tried to reenroll themselves or refer friends. Without this isolated pocket of fraud, the prevalence of fraud in this online sample among people who screened eligible would have been 7.6%, which is substantially lower than that found in a study of young men who have sex with men in nearby Central Kentucky (28.7%).36

Limitations

This study had several limitations. First, the recruitment of index participants via street outreach and convenience sampling was a departure from the recommended strategy for seed selection in traditional RDS. In traditional RDS, seeds should be people who are highly central to the social network from which the sample is obtained, so that if other assumptions are met, population-level estimates can be obtained.14 Obtaining population estimates was not an objective of this study; therefore, the criteria for seed recruitment were relaxed. Second, because we conducted this study exclusively in a rural population, we could not determine the extent to which face-to-face contact with staff members varies in its importance to recruitment activities according to where a person resides along the rural–urban continuum.

Conclusion

Recruitment strategies for enrolling community-based samples of PWUD have primarily been developed for and tested in population-dense, urban settings; evidence on the feasibility of these strategies in rural settings is lacking. This study revealed that a combination of street outreach via community cookouts, advertisements in a local field office, and web-based peer referral were successful strategies in recruiting young PWUD in rural areas. Recruitment strategies that involved a personal connection via participants’ or their peers’ contact with study staff members through cookouts and in brick-and-mortar field offices were critical to successful recruitment. More research is needed to more fully understand reasons for the success of cookouts and field office–based recruitment strategies and to understand how this success varies across the rural–urban continuum and demographic groups. Although research involving administrative data and recruitment of treatment- and justice-involved PWUD plays an important role in understanding substance use in rural settings, research involving recruitment of community-based samples of PWUD who are not in treatment is essential to fully understand their health and risk behaviors and access to care.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the study participants for their input, community researchers (Mary Beth Lawson, Travis Green, and Cindy Jolly) for assistance with survey administration and logistics, Nicole Luisi and Danielle Lambert for technical support with survey programming, and Nadya Prood and Paige Higginson-Rollins for study support. The authors also thank Paige Higginson-Rollins for designing the study logo and leading the dissemination of flyers at the beginning of the study and José Bauermeister for his consultation in the study design.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: This study was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R21 DA042727; principal investigators: Cooper and Young). The CARE2HOPE study was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), and the Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC) (UG3 DA044798; principal investigators: Young and Cooper). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health, CDC, SAMHSA, or ARC. The Emory Center for AIDS Research (P30 AI050409; principal investigators: del Rio, Curran, Hunter) provided technical support with survey programming.

ORCID iD

April M. Young, PhD, MPH https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3969-3249

References

- 1. Palombi LC., St Hill CA., Lipsky MS., Swanoski MT., Lutfiyya MN. A scoping review of opioid misuse in the rural United States. Ann Epidemiol. 2018;28(9):641-652. 10.1016/j.annepidem.2018.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schalkoff CA., Lancaster KE., Gaynes BN. et al. The opioid and related drug epidemics in rural Appalachia: a systematic review of populations affected, risk factors, and infectious diseases. Subst Abus. 2020;41(1):35-69. 10.1080/08897077.2019.1635555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Havens JR., Oser CB., Leukefeld CG. Increasing prevalence of prescription opiate misuse over time among rural probationers. J Opioid Manag. 2007;3(2):107-111. 10.5055/jom.2007.0047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Havens JR., Oser CB., Leukefeld CG. et al. Differences in prevalence of prescription opiate misuse among rural and urban probationers. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2007;33(2):309-317. 10.1080/00952990601175078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Havens JR., Walker R., Leukefeld CG. Prevalence of opioid analgesic injection among rural nonmedical opioid analgesic users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;87(1):98-102. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality Behavioral Health Trends in the United States: Results From the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. HHS Pub No SMA 15-4927. US Department of Health and Human Services; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Subramaniam GA., Stitzer MA. Clinical characteristics of treatment-seeking prescription opioid vs. heroin-using adolescents with opioid use disorder. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;101(1-2):13-19. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.10.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Paulozzi LJ., Xi Y. Recent changes in drug poisoning mortality in the United States by urban–rural status and by drug type. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2008;17(10):997-1005. 10.1002/pds.1626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Van Handel MM., Rose CE., Hallisey EJ. et al. County-level vulnerability assessment for rapid dissemination of HIV or HCV infections among persons who inject drugs, United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;73(3):323-331. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Valdiserri R., Khalsa J., Dan C. et al. Confronting the emerging epidemic of HCV infection among young injection drug users. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(5):816-821. 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zibbell JE., Hart-Malloy R., Barry J., Fan L., Flanigan C. Risk factors for HCV infection among young adults in rural New York who inject prescription opioid analgesics. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(11):2226-2232. 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zibbell JE., Iqbal K., Patel RC. et al. Increases in hepatitis C virus infection related to injection drug use among persons aged ≤30 years—Kentucky, Tennessee, Virginia, and West Virginia, 2006-2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(17):453-458. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Heckathorn DD., Semaan S., Broadhead RS., Hughes JJ. Extensions of respondent-driven sampling: a new approach to the study of injection drug users aged 18-25. AIDS Behav. 2002;6(1):55-67. 10.1023/A:1014528612685 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Heckathorn DD. Respondent-driven sampling: a new approach to the study of hidden populations. Soc Probl. 1997;44(2):174-199. 10.2307/3096941 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Watters JK., Biernacki P. Targeted sampling: options for the study of hidden populations. Soc Probl. 1989;36(4):416-430. 10.2307/800824 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Muhib FB., Lin LS., Stueve A. et al. A venue-based method for sampling hard-to-reach populations. Public Health Rep. 2001;116(suppl 1):216-222. 10.1093/phr/116.S1.216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Draus P., Carlson RG. Down on main street: drugs and the small-town vortex. Health Place. 2009;15(1):247-254. 10.1016/j.healthplace.2008.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Draus PJ., Siegal HA., Carlson RG., Falck RS., Wang J. Cracking the cornfields: recruiting illicit stimulant drug users in rural Ohio. Sociol Q. 2005;46(1):165-189. 10.1111/j.1533-8525.2005.00008.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rudolph AE., Young AM., Havens JR. A rural/urban comparison of privacy and confidentiality concerns associated with providing sensitive location information in epidemiologic research involving persons who use drugs. Addict Behav. 2017;74:106-111. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.06.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wang J., Falck RS., Li L., Rahman A., Carlson RG. Respondent-driven sampling in the recruitment of illicit stimulant drug users in a rural setting: findings and technical issues. Addict Behav. 2007;32(5):924-937. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.06.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Young AM., Rudolph AE., Havens JR. Network-based research on rural opioid use: an overview of methods and lessons learned. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2018;15(2):113-119. 10.1007/s11904-018-0391-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Young AM., Rudolph AE., Quillen D., Havens JR. Spatial, temporal and relational patterns in respondent-driven sampling: evidence from a social network study of rural drug users. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2014;68(8):792-798. 10.1136/jech-2014-203935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Strömdahl S., Lu X., Bengtsson L., Liljeros F., Thorson A. Implementation of web-based respondent driven sampling among men who have sex with men in Sweden. PLoS One. 2015;10(10):e0138599. 10.1371/journal.pone.0138599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Theunissen K., Hoebe C., Kok G. et al. A web-based respondent driven sampling pilot targeting young people at risk for Chlamydia trachomatis in social and sexual networks with testing: a use evaluation. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;12(8):9889-9906. 10.3390/ijerph120809889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wejnert C., Heckathorn DD. Web-based network sampling: efficiency and efficacy of respondent-driven sampling for online research. Sociol Methods Res. 2008;37(1):105-134. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Crawford S. Revisiting the outsiders: innovative recruitment of a marijuana user network via web-based respondent driven sampling. Soc Netw. 2014;3(1):19-31. 10.4236/sn.2014.31003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bengtsson L., Lu X., Nguyen QC. et al. Implementation of web-based respondent-driven sampling among men who have sex with men in Vietnam. PLoS One. 2012;7(11):e49417. 10.1371/journal.pone.0049417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bauermeister JA., Zimmerman MA., Johns MM., Glowacki P., Stoddard S., Volz E. Innovative recruitment using online networks: lessons learned from an online study of alcohol and other drug use utilizing a web-based, respondent-driven sampling (webRDS) strategy. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2012;73(5):834-838. 10.15288/jsad.2012.73.834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sanchez T., Smith A., Denson D., Dinenno E., Lansky A. Internet-based methods may reach higher-risk men who have sex with men not reached through venue-based sampling. Open AIDS J. 2012;6(1):83-89. 10.2174/1874613601206010083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Anderson M. About a quarter of rural Americans say access to high-speed internet is a major problem. Pew Research Center. September 10, 2018. Accessed June 16, 2020 https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/09/10/about-a-quarter-of-rural-americans-say-access-to-high-speed-internet-is-a-major-problem/

- 31. US Department of Agriculture Rural–urban continuum codes. 2013. Accessed March 6, 2020 https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-continuum-codes.aspx

- 32. US Census Bureau Decennial census datasets: 2010 Census. 2010. Accessed June 5, 2020 https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/decennial-census/data/datasets.2010.html

- 33. Ballard AM., Cooper HLF., Young AM. Web-based eligibility quizzes to verify opioid use and county residence among rural young adults: eligibility screening results from a feasibility study. JMIR Res Protoc. 2019;8(6):e12984. 10.2196/12984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bowen AM., Daniel CM., Williams ML., Baird GL. Identifying multiple submissions in internet research: preserving data integrity. AIDS Behav. 2008;12(6):964-973. 10.1007/s10461-007-9352-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cooper HLF., Crawford ND., Haardörfer R. et al. Using web-based pin-drop maps to capture activity spaces among young adults who use drugs in rural areas: cross-sectional survey. JMIR Pub Health Surveill. 2019;5(4):e13593. 10.2196/13593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ballard AM., Cardwell T., Young AM. Fraud detection protocol for web-based research among men who have sex with men: protocol development and descriptive evaluation. JMIR Pub Health Surveill. 2019;5(1):e12344. 10.2196/12344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Churchill SL., Clark VLP., Prochaska-Cue K., Creswell JW., Ontai-Grzebik L. How rural low-income families have fun: a grounded theory study. J Leis Res. 2007;39(2):271-294. 10.1080/00222216.2007.11950108 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bories TL., Buwick A. A rural, noncompetitive youth running program that aims to make a difference. Child Obes. 2013;9(1):67-70. 10.1089/chi.2012.0093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Barry AE., Sutherland MS., Harris GJ. Faith-based prevention model: a rural African-American case study : Natarajan M., Drug Abuse: Prevention and Treatment. Vol 3. Routledge; 2010:147-156. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Coker-Appiah DS., Akers AY., Banks B. et al. In their own voices: rural African American youth speak out about community-based HIV prevention interventions. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2009;3(4):301-312. 10.1353/cpr.0.0093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]