Abstract

OBJECTIVES

The aims of this study were to examine variation in the use of conscious sedation (CS) for transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) across hospitals and over time and to evaluate outcomes of CS compared with general anesthesia (GA) using instrumental variable analysis, a quasi-experimental method to control for unmeasured confounding.

BACKGROUND

Despite increasing use of CS for TAVR, contemporary data on utilization patterns are lacking, and existing studies evaluating the impact of sedation choice on outcomes may suffer from unmeasured confounding.

METHODS

Among 120,080 patients in the TVT (Transcatheter Valve Therapy) Registry who underwent transfemoral TAVR between January 2016 and March 2019, the relationship between anesthesia choice and TAVR outcomes was evaluated using hospital proportional use of CS as an instrumental variable.

RESULTS

Over the study period, the proportion of TAVR performed using CS increased from 33% to 64%, and CS was used in a median of 0% and 91% of cases in the lowest and highest quartiles of hospital CS use, respectively. On the basis of instrumental variable analysis, CS was associated with decreases in in-hospital mortality (adjusted risk difference: 0.2%; p = 0.010) and 30-day mortality (adjusted risk difference: 0.5%; p < 0.001), shorter length of hospital stay (adjusted difference: 0.8 days; p < 0.001), and more frequent discharge to home (adjusted risk difference: 2.8%; p < 0.001) compared with GA. The magnitude of benefit for most endpoints was less than in a traditional propensity score-based approach, however.

CONCLUSIONS

In contemporary U.S. practice, the use of CS for TAVR continues to increase, although there remains wide variation across hospitals. The use of CS for TAVR is associated with improved outcomes (including reduced mortality) compared with GA, although the magnitude of benefit appears to be less than in previous studies.

Keywords: anesthesia, aortic stenosis, outcomes, TAVR, variation

Transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) was initially developed as a less invasive alternative to surgical aortic valve replacement for high-risk or inoperable patients (1). Subsequent innovations in device design and deployment have made TAVR even less invasive and have enabled the development of the minimalist approach (2). An integral component of minimalist TAVR is the use of conscious sedation instead of general anesthesia with endotracheal intubation. Whereas the early pivotal TAVR trials used general anesthesia exclusively, the use of conscious sedation has increased in recent years (3,4). However, robust data on the current use of conscious sedation for TAVR and its impact on clinical outcomes are lacking.

With the exception of one small randomized trial (5), most data on the safety and effectiveness of conscious sedation for TAVR have been derived from observational studies. In particular, several large propensity score-based observational studies have shown that conscious sedation was associated with lower in-hospital mortality and shorter hospital or intensive care unit lengths of stay (3,4,6). Given the observational nature of these studies, however, there exists significant potential for residual confounding due to treatment selection bias. As such, the need for alternative analytic approaches to investigate the safety and efficacy of different anesthesia strategies during TAVR is warranted.

In this study, we leveraged data from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons/American College of Cardiology TVT (Transcatheter Valve Therapy) Registry to accomplish two aims. First, we examined variation in use of conscious sedation for TAVR across hospitals and over time. Second, we evaluated the safety and effectiveness of conscious sedation compared with general anesthesia using instrumental variable (IV) analysis, a quasi-experimental method that controls for both measured and unmeasured confounding and thus allows one to draw causal inferences using observational data (7).

METHODS

STUDY POPULATION.

We included all consecutive adults (>18 years of age) who underwent percutaneous transfemoral TAVR between January 2016 and March 2019 and were included in the TVT Registry. The TVT Registry is a collaborative clinical registry program that collects data on patient demographics, comorbidities, and outcomes using standardized definitions on nearly all TAVR procedures performed in the United States outside of clinical trials; details of data collected and definitions have been described elsewhere (8). This study was a retrospective analysis of deidentified patient data in the TVT Registry, which has been granted a waiver of the requirement to obtain written informed consent and authorization by Advarra. We excluded all patients with emergent or salvage procedures, valve-in-valve procedures, or epidural or missing anesthesia type and from sites that performed <20 TAVR procedures during the study period.

OUTCOMES.

The primary outcome was in-hospital death. Secondary outcomes included 30-day mortality, procedural success, length of hospital stay, use of inotropic drugs, and discharge home. Procedural success was defined according to the Valve Academic Research Consortium guidelines (9). Length of hospital stay was censored at 25 days to limit the effect of outliers on estimates. We also examined a pre-specified falsification endpoint of in-hospital major or minor vascular access site complications to assess for residual confounding. We believed that this was a valid falsification endpoint, as access-site complications would be unlikely to differ as a consequence of the selected anesthesia strategy; as such, a significant difference in vascular access complications between strategies would thus likely suggest residual confounding.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS.

The key exposure of interest was sedation type (conscious sedation vs. general anesthesia). For patients with conscious sedation, no interventions are required to maintain a patent airway, and spontaneous ventilation is adequate. Patients who were recorded as receiving a combination of anesthesia types likely experienced conversion from conscious sedation to general anesthesia and were included in the conscious sedation category on an intention-to-treat basis.

For the first aim, we examined overall trends in the proportion of TAVR sites using any conscious sedation and the proportion of TAVR procedures performed under conscious sedation over time. We then examined variation in the proportion of TAVR procedures performed under conscious sedation across hospitals over the entire study period and during the final 12 months of the study period.

For the second aim, we used IV analysis to evaluate the association between sedation choice and outcomes. IV analysis is a technique that was developed in economics and has been widely applied in medical research (10–12). In traditional observational studies, unobserved factors affecting both exposure and outcomes can confound relationships between these variables. The use of IVs can overcome this problem by taking advantage of natural experiments that more closely approximate randomization (7).

Site-level preference for the use of conscious sedation (defined as the hospital’s proportion of the use of conscious sedation for all qualifying procedures during the study period) was used as the IV. In this case, the heterogeneity of practice patterns in conscious sedation use creates a “marginal population” of patients who would likely receive conscious sedation when treated at a hospital that has a high preference for conscious sedation but would be unlikely to receive conscious sedation if randomly assigned to a hospital that has a low preference for conscious sedation. When the proper assumptions are met, the IV categorizes patients into treatment groups independent of patient characteristics (13). The IV analysis then evaluates outcomes according to the likelihood of receiving the treatment of interest (i.e., conscious sedation) rather than the actual treatment received.

To assess the strength of the instrument, we used the Wald F test, which examines whether the inclusion of the instrument in the first-stage regression model is relevant. An F statistic >10 has been suggested as a general rule to classify an instrument as relevant (13). To assess the exogeneity of the instrument (i.e., the ability of the instrument to predict treatment irrespective of patient characteristics), we divided hospitals into quartiles on the basis of the proportion of TAVR procedures performed under conscious sedation and examined baseline characteristics by hospital quartile of conscious sedation use. Quartiles had equal numbers of hospitals but could have different numbers of TAVR procedures because hospital TAVR volumes differed across quartiles. We calculated standardized differences between the highest and lowest quartiles of conscious sedation use, with a threshold of at least 0.1% used to define a meaningful difference (14). In addition, we compared endpoints across quartiles using Pearson chi-square tests for each variable, with the exception of length of hospital stay, for which a Kruskal-Wallis test was performed.

To perform IV analysis, we used standard 2-stage least squares regression with each individual patient as an observation. In the first stage, patient sedation type was modeled as a function of hospital proportion of conscious sedation use (the IV) and each of the variables in the previously validated TVT Registry in-hospital mortality model as well as additional patient-level and hospital covariates, such as annualized hospital TAVR volume (Supplemental Table 1) (15). In the second stage, endpoints were modeled as a function of predicted values of patient sedation type (from the first-stage model) and the aforementioned covariates. Absolute risk estimates were calculated on the basis of the average patient in the entire cohort regardless of sedation type, with bootstrap resampling (1,000 samples) used to calculate the mean absolute risk differences (RDs) and the associated 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

To compare our results with those of prior studies, we performed a secondary propensity score-based analysis using inverse probability of treatment weighting, thus replicating the approach used in previous observational comparisons of anesthesia type (4). A propensity score model using all of the covariates listed in Supplemental Table 1 was created to predict the likelihood of a patient receiving conscious sedation, and each patient was then weighted by the inverse probability of receiving conscious sedation in the outcome models. We used logistic regression with generalized estimating equations to account for clustering in hospitals to assess the relationship between sedation type and binary endpoints, adjusted for all factors used in the propensity score analysis and incorporating the inverse probability of treatment weights. For length of hospital stay, we used Poisson regression with generalized estimating equations to account for clustering in hospitals. Finally, to allow direct comparison of these results with the IV results, we calculated absolute risk estimates on the basis of the mean predicted probability of an event when all patients received conscious sedation or when all patients received general anesthesia; similar to the IV analysis, CIs were based on bootstrap replication (1,000 samples).

As a sensitivity analysis, all analyses were repeated using only hospitals from the highest and lowest quartiles of conscious sedation use. We also performed subgroup analyses on the basis of Society of Thoracic Surgeons risk score and body mass index categories. Multiple imputations were used to address missing data in baseline characteristics. A 2-sided p value < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance without adjustment for multiple comparisons. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina).

RESULTS

Between January 2016 and March 2019, a total of 150,301 patients underwent TAVR and were included in the TVT Registry. After excluding patients with ≤18 years of age (n = 14), patients undergoing non-transfemoral access or transfemoral access via surgical cutdown (n = 20,561), emergency procedures (n = 455), patients undergoing valve-in-valve TAVR (n = 8566), patients receiving epidural anesthesia or missing anesthesia type (n = 325), and patients treated at sites reporting <20 TAVRs (n = 310), our final analytic sample included 120,080 patients from 559 sites (Supplemental Figure 1).

TEMPORAL AND SITE-LEVEL TRENDS IN THE USE OF CONSCIOUS SEDATION.

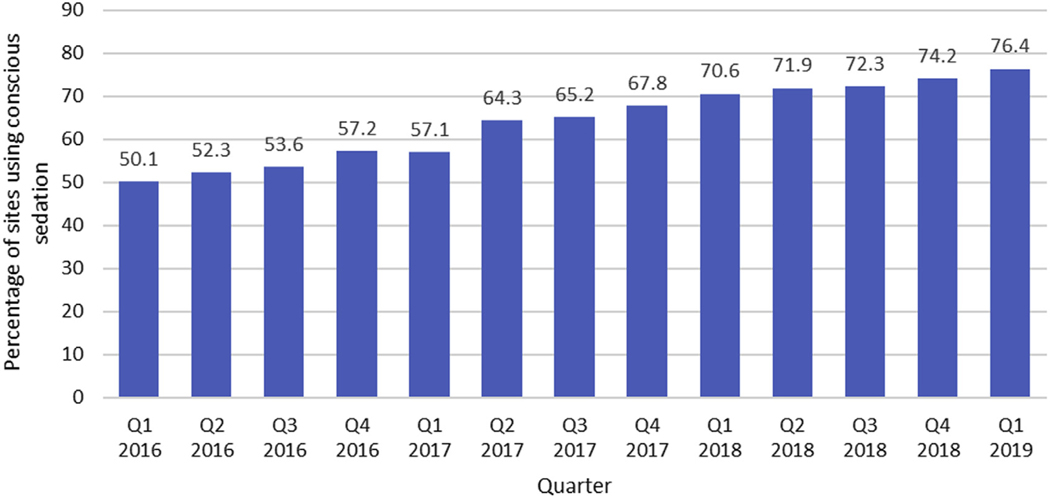

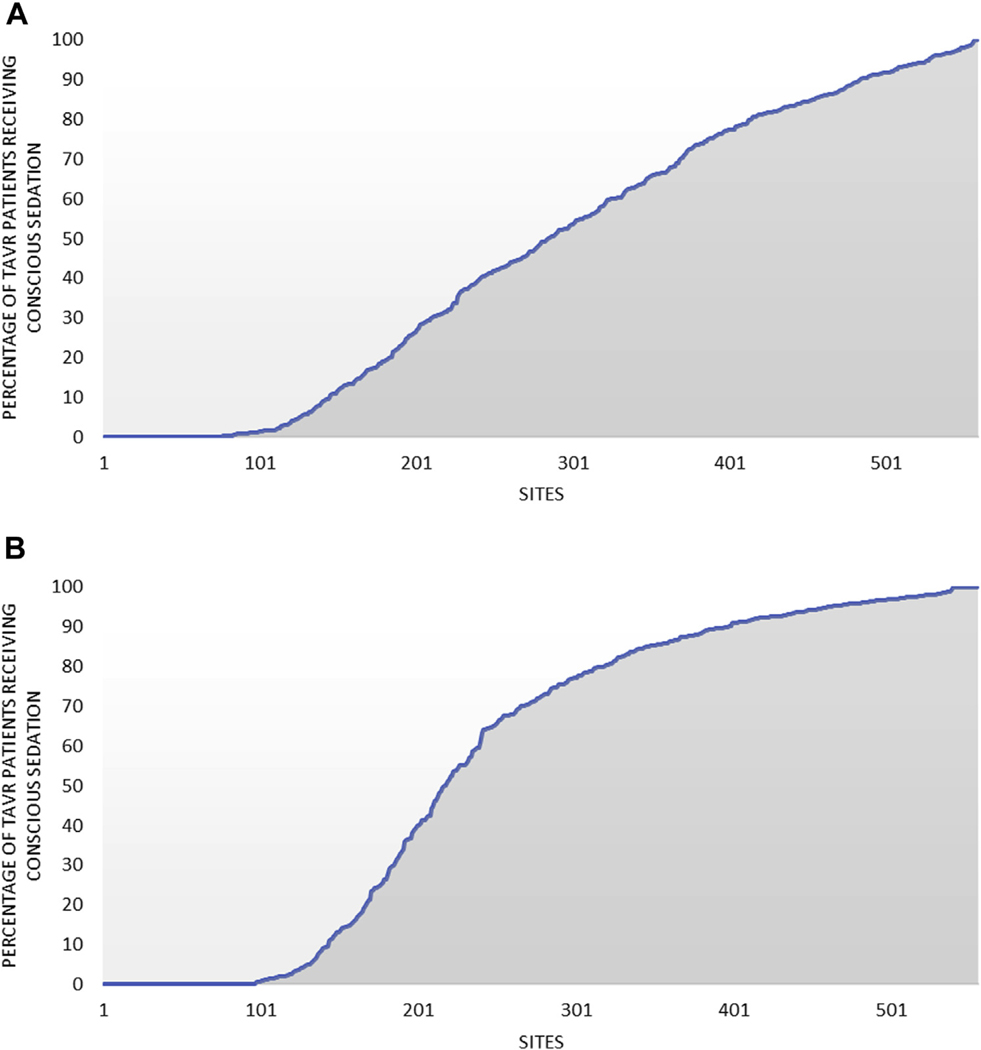

The proportion of sites using any conscious sedation during TAVR increased from 50% to 76% during the study period (Figure 1). The proportion of all TAVR procedures performed using conscious sedation increased from 33% to 63% between January 2016 and September 2018 but plateaued at 64% in the final 2 quarters of the study period (Central Illustration). In addition to temporal variation, there was wide variation in use of conscious sedation across hospitals during the study period, with 26% of sites performing >80% of TAVR procedures with conscious sedation and 13% performing no cases with conscious sedation (Figure 2A). The wide variation across sites persisted in the final 12 months of the study period, with 43% of sites performing >80% of TAVR procedures with conscious sedation and 17% performing no cases with conscious sedation (Figure 2B).

FIGURE 1. Percentage of Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement Sites Using Conscious Sedation During Valve Implantation by Calendar Quarter.

Over the study period, the proportion of sites performing at least one transcatheter aortic valve replacement procedure using conscious sedation increased gradually from 50.1% to 76.4%.

CENTRAL ILLUSTRATION. Percentage of Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement Patients Receiving Conscious Sedation During Valve Implantation by Calendar Quarter.

Between January 1, 2016 and March 31, 2019, the proportion of patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement using conscious sedation increased from 33.4% to 64.1%.

FIGURE 2. Variation in the Use of Conscious Sedation Across Hospitals in Patients Undergoing Percutaneous Transfemoral TAVR.

(A) Variation in the use of conscious sedation over the entire study period. (B) Variation in the use of conscious sedation between April 2018 and March 2019. TAVR ¼ transcatheter aortic valve replacement.

EVALUATION OF THE IV.

Over the full study period, median use of conscious sedation was 0% in the first quartile of hospitals, 30.2% in the second quartile, 65.7% in the third quartile, and 90.7% in the fourth quartile. Patient and hospital characteristics across quartiles of the IV are summarized in Table 1. Despite wide variation in hospital use of conscious sedation across quartiles, baseline demographic, clinical, echocardiographic, and procedural characteristics were nearly identical across hospital quartile of conscious sedation use. There was, however, a slightly higher prevalence of baseline conduction defects and peripheral arterial disease in the highest quartile of conscious sedation use relative to the lowest quartile. Moreover, hospital annualized TAVR volumes were higher in the highest quartile of conscious sedation use relative to the lowest quartile. The use of a combination of sedation techniques, indicating conversion from conscious sedation to general anesthesia, was less frequent in highest quartile of conscious sedation use compared with the lowest quartile of conscious sedation use (5.2% vs. 0.6%) (Supplemental Table 2). The stage 1 F statistic for evaluating the strength of the IV was 109,824, suggesting that hospital proportion of conscious sedation use was a strong instrument for anesthetic selection.

TABLE 1.

Baseline Characteristics by Quartile of Hospital Conscious Sedation Use

| Quartile 1 (n = 21,997) | Quartile 2 (n = 24,906) | Quartile 3 (n = 32,897) | Quartile 4 (n = 40,280) | Standardized Difference* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital characteristics | |||||

| Hospital % of cases under conscious sedation | 0.0 (0.0–8.7) | 30.2 (9.1–48.7) | 65.7 (49.1–81.1) | 90.7 (81.1–100.0) | NA |

| Annualized TAVR volume | 43.9 (30.1–65.8) | 48.8 (34.7–74.9) | 63.4 (44.3–95.0) | 77.7 (53.8–120.0) | 0.689 |

| Demographics | |||||

| Age (yrs) | 82.0 (76.0–86.0) | 81.0 (75.0–86.0) | 82.0 (76.0–87.0) | 82.0 (76.0–87.0) | 0.024 |

| Female | 10,125 (46.0) | 11,470 (46.1) | 15,128 (46.0) | 18,597 (46.2) | 0.003 |

| Caucasian | 20,642 (93.8) | 23,311 (93.6) | 30,382 (92.4) | 37,125 (92.2) | <0.001 |

| Clinical characteristics | |||||

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 27.9 (24.4–32.5) | 28.0 (24.4–32.6) | 27.8 (24.4–32.4) | 27.8 (24.2–32.3) | <0.001 |

| Current smoking | 1,063 (4.8) | 1,291 (5.2) | 1,745 (5.3) | 2,016 (5.0) | 0.008 |

| Diabetes | 8,439 (38.4) | 9,747 (39.1) | 12,702 (38.6) | 15,075 (37.4) | <0.001 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dl) | 12.2 (10.9–13.4) | 12.1 (10.8–13.4) | 12.2 (10.9–13.4) | 12.2 (10.9–13.4) | <0.001 |

| Platelets (per 100,000) | 198 (160–243) | 199 (160–245) | 198 (160–244) | 199 (160–245) | 0.014 |

| Currently on dialysis | 838 (3.8) | 944 (3.8) | 1,228 (3.7) | 1,507 (3.7) | <0.001 |

| Glomerular filtration rate (ml/min)† | 59.5 (46.2–74.9) | 60.2 (46.6–76.1) | 59.8 (46.2–75.2) | 59.7 (46.2–74.6) | <0.001 |

| New York Heart Association functional class IV | 2,428 (11.0) | 2,724 (10.9) | 3,474 (10.6) | 4,982 (12.4) | 0.042 |

| Atrial fibrillation/flutter | 7,963 (36.2) | 9,379 (37.7) | 12,356 (37.6) | 15,417 (38.3) | 0.043 |

| Conduction defect | 7,373 (33.5) | 9,149 (36.7) | 12,214 (37.1) | 15,714 (39.0) | 0.115 |

| Severe chronic lung disease | 1,948 (8.9) | 2,576 (10.3) | 3,144 (9.6) | 3,764 (9.3) | 0.017 |

| Home oxygen | 1,804 (8.2) | 2,026 (8.1) | 2,805 (8.5) | 3,303 (8.2) | <0.001 |

| Left main stenosis ≥50% | 1,597 (7.3) | 1,930 (7.7) | 2,438 (7.4) | 3,226 (8.0) | 0.029 |

| Proximal left anterior descending coronary artery stenosis ≥70% | 3,536 (16.1) | 4,020 (16.1) | 5,010 (15.2) | 6,627 (16.5) | 0.011 |

| Any carotid stenosis | 3,970 (18.0) | 4,658 (18.7) | 5,718 (17.4) | 7,198 (17.9) | 0.079 |

| Hostile chest | 1,050 (4.8) | 1,539 (6.2) | 2,066 (6.3) | 2,171 (5.4) | 0.028 |

| Porcelain aorta | 531 (2.4) | 955 (3.8) | 918 (2.8) | 892 (2.2) | <0.001 |

| Medical history | |||||

| Prior myocardial infarction | 4,447 (20.2) | 5,271 (21.2) | 6,798 (20.7) | 8,661 (21.5) | 0.032 |

| Prior stroke/transient ischemic attack | 3,529 (16.0) | 4,521 (18.2) | 5,721 (17.4) | 6,932 (17.2) | 0.031 |

| Prior peripheral arterial disease | 4,484 (20.4) | 5,854 (23.5) | 7,943 (24.1) | 10,130 (25.1) | 0.114 |

| Prior pacemaker | 2,901 (13.2) | 3,318 (13.3) | 4,297 (13.1) | 5,115 (12.7) | <0.001 |

| Prior implantable cardioverter-defibrillator | 753 (3.4) | 889 (3.6) | 1,023 (3.1) | 1,306 (3.2) | <0.001 |

| Prior percutaneous coronary intervention | 7,326 (33.3) | 8,086 (32.5) | 10,960 (33.3) | 13,143 (32.6) | <0.001 |

| Prior coronary artery bypass grafting | 4,355 (19.8) | 4,721 (19.0) | 6,290 (19.1) | 7,488 (18.6) | <0.001 |

| Prior cardiac surgery | 4,689 (21.3) | 5,053 (20.2) | 6,893 (21.0) | 7,959 (19.7) | 0.039 |

| Prior aortic valve procedure | 733 (3.3) | 1,060 (4.3) | 1,956 (5.9) | 1,930 (4.8) | 0.074 |

| Prior nonaortic valve procedure | 365 (1.7) | 397 (1.6) | 524 (1.6) | 831 (2.1) | 0.030 |

| Echocardiographic characteristics | |||||

| Left ventricular ejection fraction (%) | 60.0 (50.0–60.0) | 58.0 (50.0–60.0) | 58.0 (50.0–60.0) | 60.0 (50.0–60.0) | 0.003 |

| Degenerative aortic valve disease etiology | 20,717 (94.2) | 23,922 (96.0) | 31,509 (95.8) | 38,694 (96.1) | 0.091 |

| Tricuspid aortic valve morphology | 19,089 (86.8) | 22,112 (88.8) | 29,180 (88.7) | 35,572 (88.3) | 0.047 |

| Moderate or severe aortic insufficiency | 3,794 (17.2) | 3,853 (15.5) | 4,858 (14.8) | 5,871 (14.6) | <0.001 |

| Moderate or severe mitral insufficiency | 5,036 (22.9) | 5,616 (22.5) | 7,007 (21.3) | 9,117 (22.6) | <0.001 |

| Moderate or severe tricuspid insufficiency | 4,224 (19.2) | 4,827 (19.4) | 5,969 (18.1) | 7,867 (19.5) | 0.008 |

| Aortic valve area (cm2) | 0.7 (0.6–0.8) | 0.7 (0.6–0.8) | 0.7 (0.6–0.8) | 0.7 (0.6–0.8) | <0.001 |

| Aortic valve annular size (mm) | 24.0 (22.0–26.0) | 24.0 (22.0–26.0) | 24.0 (22.0–26.0) | 24.0 (22.0–26.0) | <0.001 |

| Aortic valve mean gradient (mm Hg) | 41.0 (34.0–49.0) | 42.0 (34.0–50.0) | 42.0 (35.0–50.0) | 41.0 (33.0–49.0) | 0.017 |

| Right ventricular systolic pressure (mm Hg) | 41.0 (33.0–51.0) | 42.0 (33.0–52.3) | 41.0 (33.0–52.0) | 41.0 (33.0–52.0) | 0.044 |

| Procedural characteristics | |||||

| Procedural acuity | 0.035 | ||||

| Cardiac arrest within 24 h of procedure | 38 (0.2) | 58 (0.2) | 71 (0.2) | 92 (0.2) | |

| Shock/inotrope/device-assisted procedure | 457 (2.1) | 629 (2.5) | 801 (2.4) | 925 (2.3) | |

| Urgent procedure | 1,393 (6.3) | 1,702 (6.8) | 2,283 (6.9) | 2,832 (7.0) | |

| Elective procedure | 20,109 (91.4) | 22,517 (90.4) | 29,742 (90.4) | 36,431 (90.4) | |

| Valve type | <0.001 | ||||

| Balloon-expandable valve | 15,764 (71.7) | 17,632 (70.8) | 25,911 (78.8) | 29,182 (72.4) | |

| Self-expanding valve | 6,137 (27.9) | 7,174 (28.8) | 6,861 (20.9) | 10,925 (27.1) | |

| Inoperable/extreme risk | 2,242 (10.2) | 2,446 (9.8) | 3,156 (9.6) | 3,724 (9.2) | <0.001 |

| Patient predicted mortality, Society of Thoracic Surgery 2007 | 4.8 (3.2–7.6) | 5.0 (3.2–7.9) | 4.9 (3.2–7.7) | 5.0 (3.3–7.9) | 0.059 |

Values are median (interquartile range) or n (%) unless otherwise indicated.

Standardized differences were calculated between top and bottom quartiles of conscious sedation use. A standardized difference >0.10 was considered significant.

Among patients not on dialysis.

NA = not applicable; TAVR = transcatheter aortic valve replacement.

UNADJUSTED OUTCOMES.

In unadjusted analyses, there were significant differences in the rates of in-hospital death, 30-day mortality, device success, use of inotropic drugs, and discharge home as well as length of hospital stay across quartiles of conscious sedation use (p < 0.001 for all) (Table 2). There was no significant difference in the rate of the falsification endpoint of in-hospital vascular complications across quartiles of conscious sedation use, however.

TABLE 2.

Unadjusted Post-TAVR Outcomes by Quartile of Hospital Conscious Sedation Use

| Overall (N = 120,080) | Quartile 1 (n = 21,997) | Quartile 2 (n = 24,906) | Quartile 3 (n = 32,897) | Quartile 4 (n = 40,280) | p Value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary endpoint | ||||||

| In-hospital death | 1,406 (1.2) | 306 (1.4) | 275 (1.1) | 421 (1.3) | 404 (1.0) | <0.001 |

| Secondary endpoints | ||||||

| 30-day death† | 2,466 (2.1) | 523 (2.4) | 528 (2.1) | 681 (2.1) | 734 (1.8) | <0.001 |

| Device success | 116,156 (96.7) | 21,363 (97.1) | 23,937 (96.1) | 31,871 (96.9) | 38,985 (96.8) | <0.001 |

| Length of hospital stay‡ | <0.001 | |||||

| Mean ± SD | 4.0 ± 6.8 | 4.3 ± 7.3 | 4.3 ± 7.2 | 3.9 ± 5.6 | 3.8 ± 7.1 | |

| Median (interquartile range) | 2.0 (2.0–4.0) | 2.0 (2.0–4.0) | 2.0 (2.0–4.0) | 2.0 (1.0–4.0) | 2.0 (1.0–4.0) | |

| Use of inotropic drugs | 34,712 (28.9) | 6,373 (29.0) | 7,804 (31.3) | 8,780 (26.7) | 11,755 (29.2) | <0.001 |

| Discharge home§ | 104,119 (87.7) | 18,691 (86.2) | 21,483 (87.2) | 28,653 (88.2) | 35,292 (88.5) | <0.001 |

| Falsification endpoint | ||||||

| In-hospital access site vascular complication | 3,690 (3.1) | 672 (3.1) | 746 (3.0) | 1,016 (3.1) | 1,256 (3.1) | 0.842 |

Values are n (%) unless otherwise indicated.

The p values represent results of Pearson chi-square tests performed across quartiles for each variable with the exception of hospital length of stay, for which a Kruskal-Wallis test was performed.

The percentage of patients with missing 30-day mortality data was 6.8% (6.9% in quartile 1, 7.1% in quartile 2, 8.1% in quartile 3, and 5.4% in quartile 4).

Fewer than 1% (0.95%) of patients were censored for length of stay >25 days.

Among patients discharged alive.

TAVR = transcatheter aortic valve replacement.

ADJUSTED OUTCOMES.

In IV analyses, the use of conscious sedation was associated with a modest decrease in in-hospital mortality compared with general anesthesia (1.1% vs. 1.3%; adjusted RD: −0.2%; 95% CI: −0.4% to 0.0%; p = 0.010) (Table 3). For secondary outcomes, compared with general anesthesia, conscious sedation was associated with slightly lower 30-day mortality (adjusted RD: −0.5%; 95% CI: −0.7% to −0.1%; p < 0.001), less use of inotropic drugs (adjusted RD: −4.2%; 95% CI: −5.1% to −3.5%; p < 0.001), shorter length of hospital stay (adjusted difference: −0.7 days; 95% CI: −0.8 to −0.7 days; p < 0.001), and more frequent discharge home (adjusted RD: 2.8%; 95% CI: 2.3% to 3.4%; p < 0.001). In the IV analysis, there were no significant differences in procedural success or the rate of the falsification endpoint (vascular complications) between conscious sedation and general anesthesia.

TABLE 3.

Adjusted Effect of Sedation Type on Post-TAVR Outcomes Using Instrumental Variable Analysis and Propensity Scores

| Outcome of Interest | Instrumental Variable Analysis Model |

Propensity Score-Based Model |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conscious Sedation | General Anesthesia | Absolute Risk Difference | p Value | Conscious Sedation | General Anesthesia | Absolute Risk Difference | p Value | |

| Primary endpoint | ||||||||

| In-hospital death (%) | 1.1 | 1.3 | −0.2 (−0.4 to −0.0) | 0.010 | 0.9 | 1.5 | −0.7 (−0.8 to −0.5) | <0.001 |

| Secondary endpoints | ||||||||

| 30-day death (%)* | 2.0 | 2.5 | −0.5 (−0.7 to −0.1) | <0.001 | 1.8 | 2.7 | −0.9 (−1.1 to −0.7) | <0.001 |

| Device success (%) | 97.3 | 97.3 | −0.0 (−0.2 to 0.3) | 0.947 | 97.5 | 97.3 | 0.3 (0.1 to 0.5) | <0.001 |

| Length of hospital stay (days)† | 3.5 | 4.3 | −0.7 (−0.8 to −0.7) | <0.001 | 3.5 | 4.2 | −0.7 (−0.7 to −0.7) | <0.001 |

| Use of inotropic drugs (%) | 27.0 | 31.3 | −4.2 (−5.1 to −3.5) | <0.001 | 26.2 | 32.9 | −6.7 (−7.2 to −6.1) | <0.001 |

| Discharge to home (%) | 88.9 | 86.1 | 2.8 (2.3 to 3.4) | <0.001 | 89.4 | 85.9 | 3.4 (3.1 to 3.9) | <0.001 |

| Falsification endpoint | ||||||||

| In-hospital access site vascular complication (%) | 3.0 | 3.1 | −0.1 (0.4 to 0.2) | 0.516 | 2.8 | 3.4 | −0.6 (−0.8 to −0.4) | <0.001 |

For the instrumental variables model, predicted event rates were calculated on the basis of the average patient in the entire cohort receiving conscious sedation (conscious sedation column) or general anesthesia (general anesthesia column). For the propensity score-based model, predicted event rates were calculated on the basis of the average predicted probability when all patients receive conscious sedation (conscious sedation column) and general anesthesia (general anesthesia column). Absolute risk differences and p values are provided with 1,000 samples used to calculate bootstrap confidence intervals.

The percentage of patients with missing 30-day mortality data was 6.8%.

Fewer than 1% (0.95%) of patients were censored for length of stay >25 days.

TAVR = transcatheter aortic valve replacement.

In the alternative propensity score-based analysis, conscious sedation was also associated with lower in-hospital mortality than general anesthesia (adjusted RD: −0.7%; 95% CI: −0.8% to −0.5%; p < 0.001). Similar to the IV analysis, the propensity score-based analysis also demonstrated that conscious sedation was associated with lower 30-day mortality (adjusted RD: −0.9%; p < 0.001), shorter length of hospital stay (adjusted difference: −0.7 days; p < 0.001), less use of inotropic drugs (adjusted RD: −6.7%; p < 0.001), and more frequent discharge to home (adjusted RD: 3.4%; p < 0.001). Although the absolute differences were generally larger in the propensity score-based analysis, 95% CIs for propensity score-based estimates overlapped with those with the IV analysis for several of these outcomes. In contrast to the IV analysis, however, the propensity score-based analysis demonstrated that conscious sedation was associated with a higher rate of device success (adjusted RD: 0.3%; p < 0.001) and a significant difference in the falsification endpoint of vascular complications (adjusted RD: −0.6%; p < 0.001), suggesting the possible influence of residual confounding.

In a sensitivity analysis restricted to patients in the lowest and highest quartiles of the IV, results were generally similar to the primary IV analysis (Supplemental Table 3). Results of the IV analysis for in-hospital mortality were also consistent when stratified according to body mass index and Society of Thoracic Surgeons risk score (Supplemental Table 4).

DISCUSSION

In this study of contemporary data from the TVT Registry, we found that among patients undergoing transfemoral TAVR between 2016 and 2019, there was substantial growth in the use of conscious sedation. Nonetheless, 35% of patients continue to receive general anesthesia for transfemoral TAVR, and 17% of U.S. centers continue to exclusively use general anesthesia for TAVR procedures. Using IV methodology to account for both measured and unmeasured confounding, we found that the use of conscious sedation was associated with lower in-hospital and 30-day mortality, less use of inotropic drugs, shorter length of hospital stay, and more frequent discharge home compared with general anesthesia. Notably, the magnitude of the effect of conscious sedation on these outcomes was generally smaller than those derived from traditional propensity score-based methods. These results have important implications for best practices in TAVR as well as for future studies seeking to evaluate advances in the treatment of structural heart disease using large registries.

COMPARISON WITH PREVIOUS STUDIES.

Several previous studies have examined patterns of use of conscious sedation for TAVR. A previous study based on the TVT Registry showed an increase in the use of conscious sedation from 11% in mid-2014 to 20% in mid-2015 (4). A second study restricted to patients receiving self-expanding valves demonstrated growth in the use of conscious sedation from 8.7% in early 2014 to 37.3% in mid-2016 (3). Our study demonstrates a continuation of these trends, with continued growth in the use of conscious sedation from 33% to 63% between January 2016 and September 2018. However, the proportion of patients receiving conscious sedation remained stable during the last 6 months of the study period, suggesting a plateau in the uptake of conscious sedation for TAVR. Although to some extent, this plateau may reflect the existence of a fixed proportion of patients who are not appropriate for conscious sedation (e.g., morbid obesity, obstructive sleep apnea, severe lung disease), patient suitability alone is unlikely to explain the observed trend, as the top quartile of hospitals used conscious sedation for 91% of all TAVR procedures. It is also possible that increased volume at newer TAVR centers primarily using general anesthesia could account for some of this plateau.

We also found that despite the overall trend, there is still substantial variation across centers, with nearly one-fifth of centers not using any conscious sedation in the final year of the study. Although growth of new TAVR centers that may use general anesthesia preferentially in their initial cases could account for some of this variation, it is worth noting that annual procedural volume ranged from 13 to 247 across the 114 centers that did not use conscious sedation in the last 6 months of our study, and only 6 of these centers had <1 year of TAVR experience. Understanding the factors driving the variability in adoption of conscious sedation for TAVR is a rich area for further inquiry.

The results of this study also advance our understanding of the safety and effectiveness of conscious sedation for TAVR. To date, the best evidence regarding choice of sedation for TAVR comes from the SOLVE-TAVI (Second-Generation Self-Expandable Versus Balloon-Expandable Valves and General Versus Local Anesthesia in TAVI) trial, which randomized 447 patients undergoing transfemoral TAVR to conscious sedation versus general anesthesia and found no differences in a multifaceted composite primary endpoint including all-cause mortality, stroke, myocardial infarction, infection requiring antibiotic treatment, and acute kidney injury at 30 days (5). However, that study was underpowered to evaluate individual endpoints and had virtually no power to detect a relative reduction in mortality of 15%, as was seen in our study. In contrast, several large propensity score-based observational studies involving more than 10,000 patients each have found that conscious sedation is associated with lower in-hospital mortality and shorter length of hospital or intensive care unit stay (3,4,6). Given the observational nature of these studies, however, there is significant potential for residual confounding. In particular, the decision to use conscious sedation or general anesthesia may be driven by subjective assessment of patient risk, which can also influence outcomes.

To overcome these limitations, we used IV analysis to complement traditional methods of risk adjustment. The IV accounts for both measured and unmeasured confounding by exploiting the quasi-random assignment of treatment site, which appears to be unrelated to patient characteristics. Using this statistical technique, we found that use of conscious sedation was associated with improved outcomes compared with general anesthesia, but the magnitude of benefit was substantially less than in our secondary propensity score-based estimates. Although our IV analysis demonstrated a reduction in in-hospital mortality that was substantially smaller than in a previous propensity score-based analysis of TVT Registry data (absolute risk reduction 0.2% vs. 0.9%; relative risk reduction 15% vs. 38%) (4), it is unclear whether these differences stem from better adjustment for unmeasured confounders in our IV approach or temporal changes in patient characteristics and other aspects of care between the two studies. Importantly, the propensity score-based approach in our study found a significant difference for our falsification endpoint, in-hospital access site–related vascular complications, which was not present in the IV analysis. This finding suggests that the propensity score-based approach may have been biased by the selection of healthier patients to receive conscious sedation in our study.

CLINICAL AND METHODOLOGIC IMPLICATIONS.

When interpreting the results of our study, it is important to keep in mind the type of estimates generated from IV analysis. In particular and in contrast to a randomized clinical trial, the results of IV analysis apply only to the marginal patients: those patients for whom treatment would be expected to differ according to the IV (i.e., site-level preference for conscious sedation). Given the wide variability in conscious sedation use across treatment sites, however, >90% of the TAVR population would be included in this marginal patient group. In contrast, our results would not apply to those patients who always receive general anesthesia, even at centers with high conscious sedation use (e.g., patients with severe lung disease on oxygen or significant right ventricular dysfunction). Nevertheless, our study suggests that conscious sedation should be considered the preferred mode of anesthesia for the vast majority of patients undergoing TAVR, unless there is a strong clinical justification for general anesthesia in a particular patient.

On the basis of the results of our study, one can project that if all U.S. centers used conscious sedation at a rate similar to the hospitals in the highest quartile of conscious sedation use (91% of cases), there would be 36 (95% CI: 7 to 63) fewer in-hospital deaths, 76 (95% CI: 22 to 117) fewer deaths at 30 days, and 464 (95% CI: 373 to 563) more patients discharged home each year on the basis of our absolute RD estimates. In addition, patients would spend about 12,300 fewer days (95% CI: 11,300 to 13,200 days) in the hospital each year after TAVR. At a cost of about $2,000 per hospital day (16), this would lead to cost savings of about $25 million/year. Our findings thus support the continued growth in the use of conscious sedation for TAVR and suggest that more effort is needed to encourage its use more broadly.

This study also has implications for the choice of analytic approaches to evaluate comparative effectiveness in large cardiovascular registries such as the TVT Registry. We used two different analytic methods to examine the impact of type of sedation on TAVR outcomes: a traditional propensity score-based approach and an IV approach. The results of the two analyses were qualitatively similar, and the 95% CIs of our estimates overlapped for some of our outcomes. However, the fact that the falsification analysis was positive in the propensity score-based analysis but not in the IV analysis provides evidence that the propensity score-based approach suffered from residual confounding, which the IV approach was able to overcome. Although several studies have demonstrated the utility of IV analysis for addressing important questions in coronary revascularization (17–19), this is the first study to use IV regression in the field of structural heart disease. Our findings suggest that future comparative effectiveness studies based on the TVT Registry and in large cardiovascular registries more broadly should consider the use of IV analysis as well as falsification endpoints to ensure the robustness of findings, particularly if there is a potential for substantial confounding by indication.

STUDY LIMITATIONS.

First, despite the use of IV analysis, the possibility of residual confounding still exists because of the observational nature of our study. In particular, it is possible that hospitals that use more conscious sedation provide higher quality care in ways that are not accounted for in our model. We attempted to limit this effect by controlling for hospital TAVR volume, which has been associated with improved outcomes (20) and may capture unmeasured dimensions of TAVR quality. The fact that the falsification endpoint was negative in our IV analysis also suggests that any impact of residual confounding may be negligible.

Second, fast-track pathways that emphasize avoidance of the intensive care unit, urinary catheters, central lines, and early ambulation may be implemented in concert with conscious sedation and may also have contributed to the effect of conscious sedation on length of stay seen in this study. However, many of these interventions are also enabled by the use of conscious sedation and thus may be mediators of its effect on outcomes. Moreover, it seems unlikely that processes aimed primarily at improving hospital efficiency would have a meaningful impact on mortality.

Third, our study focused primarily on short-term outcomes, because we believed that they would most closely reflect the effect of anesthesia choice. As such, the impact of sedation choice on outcomes beyond 30 days is unclear.

Fourth, the TVT Registry does not currently distinguish between lighter conscious sedation (as would be administered by catheterization laboratory personnel) and monitored anesthesia care (administered by an anesthesiologist and allowing deeper levels of sedation without intubation).

Finally, our results may not extend to patients with significant comorbidities that may make conscious sedation prohibitively challenging, for whom general anesthesia use may be considered a preferred option. Given the extremely high rate of conscious sedation at the highest quartile centers, it is unlikely that this proportion should exceed 10% to 15% in contemporary practice.

CONCLUSIONS

On the basis of contemporary data from the TVT Registry, there has been continued growth in the use of conscious sedation for TAVR, although there remains substantial hospital-level variation. Although the magnitude of absolute and relative benefit appears to be less than suggested by previous studies, we found that the use of conscious sedation for TAVR is associated with improved outcomes compared with general anesthesia. As such, conscious sedation should be considered the preferred approach to anesthesia for the vast majority of (but not all) patients undergoing TAVR.

Supplementary Material

PERSPECTIVES.

WHAT IS KNOWN?

Contemporary data on the use of conscious sedation for TAVR are lacking, and existing studies evaluating the impact of sedation choice on clinical outcomes may suffer from unmeasured confounding.

WHAT IS NEW?

The use of conscious sedation for TAVR increased from 33% to 64% of all TAVR cases between 2016 and 2019, although there remains wide variation across hospitals. The use of conscious sedation for TAVR was associated with improved outcomes (including reduced mortality and shorter length of stay) compared with general anesthesia.

WHAT IS NEXT?

Understanding drivers of hospital variation in use of conscious sedation and whether this variation will continue to persist in the future is be a rich area of further inquiry.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Butala is funded by the John S. LaDue Memorial Fellowship at Harvard Medical School; and has received consulting fees and has ownership interest in HiLabs, outside the submitted work. Dr. Marquis-Gravel has received honoraria and/or speaking fees from Servier and Novartis (unrelated to study content). Dr. Secemsky has received grants from AstraZeneca, BD Bard, Boston Scientific, Cook Medical, Cardiovascular Systems, Inc., Medtronic, Philips, and the University of California, San Francisco; is a consultant for Cardiovascular Systems, Inc., Medtronic, and Philips; and is on the Speakers Bureau of BD Bard, Cook Medical, and Medtronic. Dr. Yeh has received additional grant support from Abiomed, AstraZeneca, and Boston Scientific; and has received consulting fees from Abbott, Boston Scientific, Medtronic, and Teleflex, outside the submitted work. Dr. Vemulapalli has received grants and contracts from the National Institutes of Health, the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (NEST), the American College of Cardiology, the Society of Thoracic Surgeons, Abbott Vascular, and Boston Scientific; and is a consultant or advisory board member for Boston Scientific, HeartFlow, Baylabs (Caption Health), and Janssen. Dr. Cohen has received institutional grant support from Edwards Lifesciences, Medtronic, Boston Scientific, and Abbott; and has received consulting fees from Edwards Lifesciences, Medtronic, Boston Scientific, and Abbott.

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

- CI

confidence interval

- IV

instrumental variable

- RD

risk difference

- TAVR

transcatheter aortic valve replacement

Footnotes

All other authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose. The authors attest they are in compliance with human studies committees and animal welfare regulations of the authors’ institutions and Food and Drug Administration guidelines, including patient consent where appropriate. For more information, visit the JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions author instructions page.

APPENDIX For supplemental tables and a figure, please see the online version of this paper.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cribier A, Eltchaninoff H, Bash A, et al. Percutaneous transcatheter implantation of an aortic valve prosthesis for calcific aortic stenosis: first human case description. Circulation 2002;106: 3006–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wood DA, Lauck SB, Cairns JA, et al. The Vancouver 3M (Multidisciplinary, Multimodality, but Minimalist) clinical pathway facilitates safe next-day discharge home at low-, medium-, and high-volume transfemoral transcatheter aortic valve replacement centers: the 3M TAVR study. J Am Coll Cardiol Intv 2019;12:459–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Attizzani GF, Patel SM, Dangas GD, et al. Comparison of local versus general anesthesia following transfemoral transcatheter self-expanding aortic valve implantation (from the Transcatheter Valve Therapeutics Registry). Am J Cardiol 2019;123:419–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hyman MC, Vemulapalli S, Szeto WY, et al. Conscious sedation versus general anesthesia for transcatheter aortic valve replacement: insights from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry Society of Thoracic Surgeons/American College of Cardiology Transcatheter Valve Therapy Registry. Circulation 2017;136:2132–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thiele H. A 2×2 randomized trial of self-expandable vs balloon-expandable valves and general vs local anesthesia in patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Presented at: Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics; 2018; San Diego, CA. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Husser O, Fujita B, Hengstenberg C, et al. Conscious sedation versus general anesthesia in transcatheter aortic valve replacement: the German Aortic Valve Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol Intv 2018;11:567–78. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cameron AC, Trivedi PK. Microeconometrics: Methods and Applications. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carroll JD, Edwards FH, Marinac-Dabic D, et al. The STS-ACC Transcatheter Valve Therapy national registry: a new partnership and infrastructure for the introduction and surveillance of medical devices and therapies. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;62:1026–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leon MB, Piazza N, Nikolsky E, et al. Standardized endpoint definitions for transcatheter aortic valve implantation clinical trials: a consensus report from the Valve Academic Research Consortium. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;57: 253–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McClellan M, McNeil BJ, Newhouse JP. Does more intensive treatment of acute myocardial infarction in the elderly reduce mortality? Analysis using instrumental variables. JAMA 1994;272: 859–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stukel TA, Fisher ES, Wennberg DE, Alter DA, Gottlieb DJ, Vermeulen MJ. Analysis of observational studies in the presence of treatment selection bias: effects of invasive cardiac management on AMI survival using propensity score and instrumental variable methods. JAMA 2007;297: 278–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schneeweiss S, Seeger JD, Landon J, Walker AM. Aprotinin during coronary-artery bypass grafting and risk of death. N Engl J Med 2008;358:771–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Staiger DO, Stock JH. Instrumental variables regression with weak instruments. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Austin PC. Using the standardized difference to compare the prevalence of a binary variable between two groups in observational research. Commun Stat Sim Comput 2009;38: 1228–34. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Edwards FH, Cohen DJ, O’Brien SM, et al. Development and validation of a risk prediction model for in-hospital mortality after transcatheter aortic valve replacement. JAMA Cardiol 2016;1: 46–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baron SJ, Wang K, House JA, et al. Cost-effectiveness of transcatheter versus surgical aortic valve replacement in patients with severe aortic stenosis at intermediate risk. Circulation 2019;139:877–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wimmer NJ, Secemsky EA, Mauri L, et al. Effectiveness of arterial closure devices for preventing complications with percutaneous coronary intervention: an instrumental variable analysis. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2016;9: e003464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Secemsky EA, Kirtane A, Bangalore S, et al. Use and effectiveness of bivalirudin versus unfractionated heparin for percutaneous coronary intervention among patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction in the United States. J Am Coll Cardiol Intv 2016;9: 2376–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Secemsky EA, Ferro EG, Rao SV, et al. Association of physician variation in use of manual aspiration thrombectomy with outcomes following primary percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-elevation myocardial infarction: the National Cardiovascular Data Registry CathPCI Registry. JAMA Cardiol 2019;4:110–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vemulapalli S, Carroll JD, Mack MJ, et al. Procedural volume and outcomes for transcatheter aortic-valve replacement. N Engl J Med 2019;380:2541–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.