Abstract

Introduction

Assistive technology (AT) is important for the achievement of the sustainable development goals (SDGs) for persons with disabilities (PWD). Increasingly, studies suggest a significant gap between the need for and demand for and provisions of AT for PWD in low-income and middle-income settings. Evidence from high income countries highlights the importance of robust AT policies to the achievement of the recommendations of the World Health Assembly on AT. In Malawi, there is no standalone AT policy. The objectives of the Assistive Product List Implementation Creating Enablement of inclusive SDGs (APPLICABLE) project, are to propose and facilitate the development of a framework for creating effective national AT policy and specify a system capable of implementing such policies in low-income countries such as Malawi.

Method and analysis

We propose an action research process with stakeholders in AT in Malawi. APPLICABLE will adopt an action research paradigm, through developing a shared research agenda with stakeholders and including users of AT. This involves the formation of an Action Research Group that will specify the priorities for practice—and policy-based evidence, in order to facilitate the development of contextually realistic and achievable policy aspirations on AT in Malawi and provide system strengthening recommendations that will ensure that the policy is implementable for their realisation. We will undertake an evaluation of this policy by measuring supply and support for specific AT prior to, and following the implementation of the policy recommendations.

Ethics and dissemination

The study protocol was approved by Maynooth University Research Ethics Committee (SRESC-2019-2378566) and University of Malawi Research Ethics Committee (P.01/20/10). Findings from the study will be disseminated by publication in peer-reviewed journals, presentations to stakeholders in Malawi, Ireland and international audiences at international conferences.

Keywords: rehabilitation medicine, public health, social medicine, health policy

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study will be the first in Africa to explore the development of a national assistive technology (AT) policy and Assistive Product List in response to the recommendations of the WHO.

The framework developed from this study, will lead to strengthening of the AT ecosystem in Malawi and may be relevant in other countries with similar interest.

Using an emergent and action learning approach strengthens both the methods and reflexivity of the research process and ensures active participation of all stakeholders.

The use of a flexible research methodology may lead to researcher bias and deviation from the initial objectives may occur on account of the reliance on the contribution from multiple stakeholders.

The proposed principle of collective leadership may be a hard sell to the stakeholders in government who are used to the traditional single ministry lead in policy development.

Introduction

Persons with disabilities (PWD) often experience overt and covert barriers to participation in society and exercise of their rights.1 These experiences of deprivation have dire implications for PWD, depending on their location and type of impairment. This realisation has led to various efforts at both national and international level to ensure the reduction and elimination of the deprivation experience by PWD.1 2 The United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and the sustainable development goals (SDGs) emphasise the importance of inclusion for PWD.3 4 The SDGs highlight the importance of social inclusion through the slogan—‘leave no one behind’.

Assistive technology (AT) is pivotal to achieving this mandate of inclusion of PWD.4 5 AT is a subset of health technology systems and refers to ‘the development and application of organised knowledge, skills, procedures and policies relevant to the provision, use and assessment of assistive products’.6 While an assistive product is ‘any product (including devices, equipment, instruments and software), either specially designed and produced or generally available, whose primary purpose is to maintain or improve an individual’s functioning and independence and thereby promote their well-being’.6 Common examples of assistive products in different impairment domains include wheelchairs, white canes, hearing aids, communication boards and calendar pill boxes. In 2014, the WHO established the Global Cooperation on Assistive Technology (GATE) in order to address the global need for AT.7 One of the first tasks for GATE was to establish a priority Assistive Product List (APL)8 which called for countries to develop their own context specific national APL, similar to the WHO essential medicines list.9 The APL is not restrictive but a guide provided by GATE for countries to use in identifying national AT needs and priorities.8

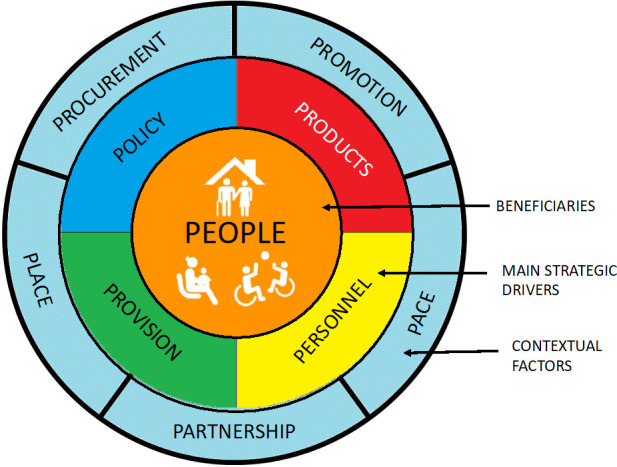

In a bid to improve access to AT, GATE recommended five priority (5Ps) themes, namely people, policy, products, provision and personnel.8 That schema put people, or users of AT, at the centre and policy, products, provision and personnel, as strategic points of action to improve access to AT around the world. In a series of position papers from the Global Research, Innovation and Education on Assistive Technology summit organised by GATE, people were identified as important drivers in AT access;10 context sensitive products were considered relevant for AT accessibility;11 the development of an international standard for provision of AT was seen as important for service user safety,12 and the certification of competency for AT personnel as important for staff training,13 along with an inclusive development of national AT policies, all to improve access to AT.14 Along with these papers, an additional 5Ps—specifically referring to the context of AT services were also identified as emergent from the discussions at the summit (see figure 1). The additional 5Ps include procurement, place, pace, promotion and partnership; and are key situational factors for systems in diverse context. These situate the previous 5Ps in national and local contexts that determine access to AT. For instance, to ensure that procurement or purchasing AT products occur at national level in line with national and contextual factors that take into account place or differences in local settings; at a pace that is feasible and can be absorbed within the systems’ capacity, using context sensitive methods to promote positive images of AT users and with cross cutting partnerships.15

Figure 1.

The 10Ps of systems thinking for assistive technology. Adapted from MacLachlan and Scherer15 (with permission).

Sterman suggests that it is not a lack of resources, technical knowledge or commitment that prevents us from making improvements in public health services but rather, ‘what thwarts us is our lack of meaningful systems thinking capability’.16 Specifically in relation to AT, MacLachlan and Scherer argue that ‘a systems thinking approach allows for a meaningful linking of components and processes, a more realistic understanding of why and where initiatives might fail or succeed, and a more satisfying way of placing the user of assistive technology at the centre of ideas, activities and outcomes’.15

Malawi context

Increasingly, studies suggest low demand and provision of AT for PWD in low-income and middle-income settings.17 Malawi is a Southern African country with a population of about 18 million. The economy is largely agrarian, and the government depends on foreign aid. Malawi ranks 172 out 189 countries based on the United Nations Human Development Index.18 In Malawi, there are several policies and strategies at the national level which are relevant to the experiences of PWD, each which should have relevance to AT. Notably, the National Policy on the Equalization of Opportunities for PWD19 and National Disability Mainstreaming Strategy and Implementation Plan;20 yet there are no clear direction guidelines on how AT should be provided in the country.20 It is pertinent to state that the National Policy on the Equalization of Opportunities for Persons with Disabilities was adopted in 2006; and processes are underway to develop a successor plan on account of its expiration. In Malawi, there is a huge gap between the need and access to services PWD.21 Although about 69% of PWD need assistive devices in Malawi, only 5% have access to them.22 Evidence from high-income countries highlights the importance of robust AT policies for the achievement of the recommendations of the World Health Assembly (WHA) on AT.23 In Malawi, there is no standalone AT policy.24

The objectives of the Assistive Product List Implementation Creating Enablement of inclusive SDGs (APPLICABLE) project are (i) to propose and facilitate the development of a framework for creating effective national AT policy and (ii) specify a system capable of implementing that policy in Malawi.

Methods and analysis

Approach

The study will adopt an action research approach25 and shared research agenda in collaboration with AT stakeholders in Malawi to achieve the study objectives. Hence, this research protocol is based on a proposed research plan by the research teams at Maynooth University and the University of Malawi and the discussions held during the project launch and formation of an Action Research Group (ARG) in Malawi.

The relevance of action research for solving persistent problems has been extensively reported.25 Boger et al recommend collaborative transdisciplinary approach for solving persistent problems in AT.26 In adopting this method, we aim to ensure that the process of AT policy development is participatory, collaborative and undertaken through a transparent and reflexive process with relevant stakeholders in Malawi. Equally essential is the relevance of the action research paradigm to the systems-thinking and mission-oriented approach which are central to the objectives of APPLICABLE. A systems thinking approach will ensure APPLICABLE focuses on the range of Ps (described earlier) to bridge the AT systems gap in Malawi.15 27 ‘Collective leadership’28 29 will be a guiding principle for the research, whereby all the participating ministries and other major stakeholders, take active leadership in the project in order to engender collective impact which is supported by research. Collective leadership refers to a group of people working together to achieve a set goal.28 29 In this case, we envision coconstruction of leadership and shared responsibility by different stakeholders involved in AT in Malawi.30 According to De Brún et al, collective leadership was associated with improved communication and role clarity, greater willingness to adopt leadership roles and ‘give and take’ by leaders, who became more willing to share leadership responsibilities.28 Also, Michaud‐Létourneau et al suggest that the approach is useful for changing policy where many stakeholders exist.29 We will strive to minimise power imbalances and the pitfalls of collective leadership by continuous learning and knowledge sharing to coconstruct what works for everyone through reflective dialogues.31

The specific research methods described later are tactical and will be decided with the ARG in an iterative process through a series of five phases, each comprised action research cycles. The content for each of those action research cycles will be decided with key stakeholders in AT in Malawi through the formation of an ARG.

Formative research

Prior to the project launch, a series of steps were undertaken as part of the formative research process. Initial meetings were held with the Ministries of Gender, Children, Disability and Social Welfare, Health, Education, and Labour, Disabled People’s Organisations, other civil society, service providers, donors, industry and United Nation agencies. Presentation and discussions on establishing a AT policy and implementation systems in Malawi were discussed and the stakeholders expressed interest in the 36 months (January 2019–December 2021) project.

The project launch was held on 6 December 2019 with over 40 stakeholders drawn from five broad stakeholder groups namely:

Government stakeholders (eg, Ministries of Health, Education, Gender and Persons with Disabilities and the Elderly).

Non-governmental non-profit stakeholders (eg, Federation of Disability Organisation in Malawi, Beit Cure International Hospital, Malawi Council for the Handicapped).

Non-governmental for-profit stakeholders (pharmacist, physiotherapist).

Academic institutions.

United Nation agencies (eg, UNICEF, WHO, United Nations Development Programme).

It is pertinent to state that PWD and users AT products are not restricted to only group two but are also in the other groups. They are involved in all the research processes and as part of the ARG.

The formative research stage describes activities undertaken prior to the project launch. The following sections describe the proposed research phases developed following the project launch.

Research phases

The study will be conducted in five phases. The details of each phase will be collaboratively decided during the action research project, but these phases will guide the work throughout the project.

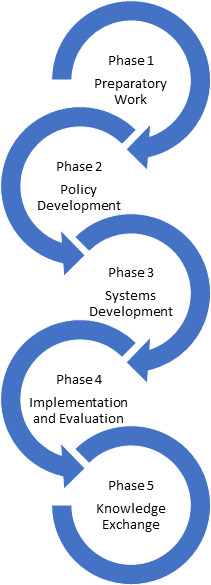

The five phases of the research are preparatory work, policy development, systems development, implementation and evaluation, and knowledge exchange (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Assistive Product List Implementation Creating Enablement of inclusive sustainable development goals research phases.

Phase I: preparatory work

This stage starts with the project launch and formation of the ARG. Following the project launch, 15 persons were invited from the stakeholders present to join the ARG. Members of the ARG have been purposively selected to work on the policy development and implementation.

The ARG adopted the proposed process and agreed that:

A realistic AT policy and delivery system is needed in Malawi.

That ownership of the policy will be further discussed and that initially it will be coled by members of the ARG.

Data will be stored at the Centre for Social Research, Malawi.

The launch was organised in collaboration with Clinton Health Access Initiative (CHAI) who previously conducted a baseline survey on AT in Malawi. They presented the results on their survey, after which APPLICABLE was introduced by the principal investigators from Malawi and Ireland. This was followed by reactions from stakeholders and selection of the ARG from the stakeholders’ present. The discussions with the ARG, informed the proposed research phases (table 1).

Table 1.

Planned and anticipated research methodology

| Research phase | Methodology |

| Phase I—preparatory work: understanding the assistive technology context in Malawi | 1. Literature review: assistive technology service delivery and policy review using academic and grey literature |

| 2. Data review: secondary data analysis of existing datasets (ie, Census, SINTEF dataset) and interviews | |

| 3. Country capacity assessment: in collaboration with AT2030 and the Clinton Health Access Initiative | |

| 4. EquiPP: review of existing policies for inclusive policy development processes | |

| Phase II—policy development: identifying key change agents and contexts | 5. EquiPP: inclusive policy development process |

| 6. Theory of change: development of theory of change for APL development | |

| 7. Field analysis: force field analysis and Bourdesian analysis to understand political economy and power relationships | |

| Phase III—systems development: engagement in collective leadership to achieve the SDGs | 8. SDG matrix: linking ministries to SDG achievement and role of AT |

| 9. Network analysis: strength and nature of existing networks between key stakeholders in AT in Malawi | |

| Phase IV—implementation and evaluation: delivering a policy or strategy in context | 10. Systems coherence development: addressing gaps in existing network to strengthen coherence for GATE 10Ps |

| 11. Market shaping analysis: smart thinking matrix | |

| 12. Piloting: implementation of strategy in key areas with review of process and outcomes | |

| Phase V—knowledge exchange: applying knowledge to the global context | 13. Policy framework: identification of key concepts for broader applicability to other contexts |

| 14. Systems implementation framework: specification of implementation system to be applied to other contexts |

APL, Assistive Product List; AT, Assistive Technology; EquiPP, Equity and Inclusion in Policy Processes; GATE, Global Cooperation on Assistive Technology; SDG, Sustainable Development Goal.

The nature of action research is that the methodology of the group is decided on by the group and is likely to change and evolve as they address different issues.25 Following an action research approach, the group will thus plan what to do—take clear and specific action—observe and collect data on the consequences of this action—and as a group reflect on the implications for designing policy to and systems to promote access to AT. In order to conduct preparatory work, we will conduct a literature review of academic and grey literature in AT in Malawi and review data available from existing datasets. In addition, we will conduct interviews with users and providers of AT guided by the data from a Country Capacity assessment by the CHAI in partnership with the AT2030 project. The research team will also assess inclusivity of the process of policy development and implementation in existing policies using the EquIPP (Equity and Inclusion in Policy Processes) tool.32 The EquIPP32 tool was developed with the United Nations Partnership on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and measures, evaluates and makes recommendations for improvement in regard to inclusive policy development and evaluation. It consists of 17 key actions that provide guidance on how to ensure an equitable and inclusive policy development process.

Phase II: policy development

Phase II will focus on the development of a draft policy, guided by the EquiPP framework for inclusive policy development. A theory of change33 will be undertaken to guide the APL development while force field analysis34 to explore the political economy and power relationships on AT in Malawi will be conducted. Force field analysis34 is a qualitative research method that conceptualises how forces for and against change are poised and thus helps in the systematic analysis of possible change processes. Bourdesian analysis35 applies the idea of the social space being composed of fields of identify and power relations which are likely to influence change process.

The ARG will design a draft AT policy, supported by the research team, drawing on the literature reviewed previously and taking into account the Malawian context. It is anticipated that the resultant draft may also be assessed for the degree to which it promotes inclusivity (eg, service users, gender, rurality, poverty, etc) using the EquiFrame tool.36 EquiFrame36 which is a tool for Evaluating and Promoting the Inclusion of Vulnerable Groups and Core Concepts of Human Rights in Health Policy Documents. It consists of 21 core concepts that covers issues relating to universal, equitable and accessible healthcare.

Phase III: system development

This phase involves the development of system strengthening recommendations based on knowledge and information generated from the policy development process. The ARG will also address what implications there are at the systems level for delivering on the draft AT policy; and to recommend how these can be addressed in the Malawian context. Data will be used to demonstrate the link between the different government ministries and stakeholders to the SDG matrix; and thus, highlight the relevance of AT to achievement of the SDGs.4 The SDG matrix will be used to demonstrate the concept that that assistive products have a direct impact on the achievement of the SGDs. Tebbutt and colleagues suggest that assistive products can be both mediators and moderators of SDG achievement.5 A network analysis37 38 will be undertaken to explore the strength and nature of relationship between stakeholders on AT in Malawi. The collective leadership approach will be very useful in this phase to ensure collective impact and system development.39

Phase IV: implementation and evaluation

This phase marks the beginning of the implementation and evaluation of the AT policy developed. Over an agreed period, the participating government ministries and stakeholders will identify a suitable service provider to trial the implementation of the draft AT policy, with the support of the identified ministry and the research team. While the ARG will be in a continuing process of evaluation and feedback themselves, stakeholders who attended the project launch will be asked to attend a project review meeting where the ARG and research team will present findings. The ARG will also identify AT service users to present their experiences during this workshop. The SMART (Systems-Market for Assistive and Related Technologies) Thinking Matrix framework will be used during the implementation and evaluation.40 The SMART Thinking Matrix is a framework for conceptualising intersections between systems levels and market shaping for AT and was derived form a systematic review of the interface between these two literatures.40

Phase V: knowledge exchange

This phase entails ensuring knowledge exchange impact of the research process. The ARG and the research team will use results from previous phases to identify key features that might be relevant for a generic national framework for AT, that will be generalised to other countries and contexts. In keeping with action research methodology, expert advisers (all of whom we have worked with before) who will be available to provide support to the ARG shall provide feedback on the research process. This support could be provided either virtually or through attendance at project meeting in Malawi; as determined by the needs of the ARG and the available budget of the project.

Action research methodology

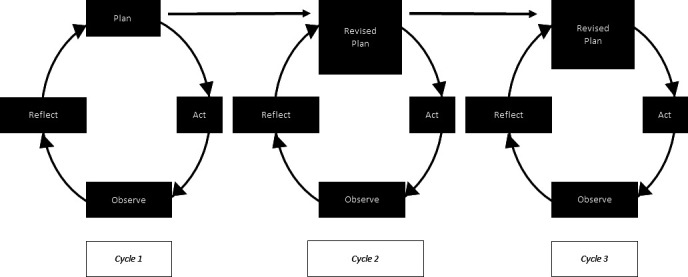

Throughout the five phases described previously, we will use an action research methodology25 informed by the needs of the ARG. This will take the form of action research cycles each consisting of four components: plan, act, observe and reflect (figure 3), to answer the research questions which are posed by the ARG, and contribute to the development of each phase.

Figure 3.

Action research process.

Throughout these cycles, we will use multiple study methods to address the questions posed by the ARG (table 1). For each research methodology, specific study procedures (table 1) to produce requested content for use in the action research cycle will be decided with the ARG.

Data collection and management

All data including the transcripts will be stored according to the provisions of the Centre for Social Research, University of Malawi Research Practice and Procedures. Hence, all primary data will be held permanently following its acquisition and used in publication for the purpose of this study and recommendations of the ARG. All data will be anonymised, and informed consent will be obtained from all study participants and stakeholders at every stage of the research process. Study participants entail all who are recruited or invited to participate in the study and may include stakeholders who are users or providers of AT. A data dictionary will be kept and maintained for both quantitative and qualitative data to ensure that all authorised individuals are able to reuse the data. Secondary data will be obtained from National the Statistics Office and National Survey on living conditions of PWD (SINTEF).

Data analysis

The data analysis method adopted will be dependent on the data type from the different phases of the study. Quantitative data will be reported according to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines while qualitative data will be reported using the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research.41 Analytic review methods will be used for literature and document review in phases I and V.42 For qualitative data (from phases I–V), content and framework analysis will be used. Both deductive and inductive methods will be adopted by the research team to code available data, depending on the nature of data and question posed by the ARG. Data coding will be conducted by independent members of the research team and assessed for congruence, with differences resolved by the research team. A process of thematic analysis will be subsequently used to identify main and sub themes relevant for the study. For quantitative data (phase I, II and III), descriptive statistics and regression analysis will be undertaken to understand factors relevant for improved access to AT and creation of a nation AT policy in Malawi.42

The EquIPP and EquiFrame tools32 36 will also be used to analyse existing policy on disability and the proposed AT policy. Quantitative data will be analysed using the SPSS V.23 while qualitative data will be analysed via Atlas.ti V.7.5.18. All data will be anonymised and not contain any personal identifiers.

Patient and public involvement

Stakeholders that include users or providers of AT were involved in the formative research process. These stakeholders who are also part of the ARG will be involved in all stages of the research including the dissemination of the results from the study.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval was obtained from the Maynooth University Social Research Ethics Committee (SRESC-2019-2378566) and University of Malawi Research Ethics Committee (UNIMAREC) (P.01/20/10).

The results from the study will be disseminated through presentations at conferences both within Malawi and abroad with stakeholders in and at international conferences; and publishing in peer-reviewed journals and on the websites of Maynooth and University of Malawi.

Discussion

The aim of APPLICABLE is to develop a national AT policy for Malawi and to contribute to the development of a framework in the process that may be relevant in other countries. Also, it is anticipated that the process will evolve a framework that will lead to strengthening of the AT ecosystem through collaborative action and partnership with all stakeholders.

These objectives informed the adoption of the action research approach that sets out on a research path without specific research agenda but entrusts the direction of the research to local and informed actors on AT in Malawi, to ensure a shared research agenda and development of context useful knowledge. This approach is in line with the ethos of the mission oriented approach for AT proposed by Albala and colleagues.27 It also avoids the common pitfall of most implementation research, where research is done for rather than with local stakeholders. Also, the action research approach ensures the development of context specific approaches for the development of APL for Malawi. Low-income settings like Malawi have particular AT challenges that must take into consideration the local realities rather than adopting recommendations from high-income settings with different socioeconomic milieu. According to Gélinas-Bronsard and colleagues, accessing AT is a matter of resources.30 While it is obvious that factors outside finance play a role in the access and utilisation of AT, its pivotal role in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where healthcare insurance and social welfare packages are absent, is a key issue that the action research approach must explicitly address.

The collective leadership approach will help to ensure all stakeholders engaged in the action research approach feel a sense of ownership and promote buy-in at all levels in the implementation phase. Historically, in Malawi and in other countries, a single ministry maintains responsibility for the development and implementation of policy—considered the policy holder. In this case, either the Ministry of Health or Gender and Disability or Education may desire to claim ownership on account of perceived ‘proximity’ of AT to their ministry. However, AT is more than just a health issue, or disability problem as shown by data from our SDG matrix. It cuts across various sectors such as education, sports and therefore require collaborative approach. As shown by Tebbut and colleagues, AT is relevant for the achievement of each of the 17 SDGs;5 hence, requires cross cutting collaboration between all players in Malawi. Interestingly, the collective leadership approach is noted to be useful for changing policy where many stakeholders exist and led to relevant policy changes in infant and young child feeding policies in seven countries in Southeast Asia.29 Similarly, a systematic review by De Brún and colleagues showed that collectivistic leadership was associated with positive outcomes in healthcare settings in Europe and North America.28 It is pertinent to note that in order to solve social problems and achieve collective impact, commitment of all relevant actors is crucial.39 This integration between systems thinking and market shaping approach presents as a practical and viable option to increase access to AT.40

The strength of this study lies in its reliance on the action research method which ensures active participation of all stakeholders. Yet, the task of managing the interest of the ‘many’ and ensuring that every opinion ‘counts’ may be the big challenge of the research process. We hope to address these through action learning and transdisciplinary approaches recommended for use in AT projects.26

Gaps between research and practice or policy and practice gaps are some of the persistent problems in disability studies. In adopting an action research process, we intend to avoid these gaps to evolve a participatory and innovative process leading to development of an implementable AT policy in Malawi. The benefits of an AT policy in Malawi are numerous. However, a realistic and implementable policy would overcome the limitations of past policies on disability in Malawi that failed to address the health and social challenges of PWD. APPLICABLE presents as an opportunity to demonstrate an innovative and participatory way of policy development that may be adapted for use in other settings.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the members of APPLICABLE action research group and all stakeholders involved in the formative research process.

Footnotes

Presented at: The abstract was accepted for presentation at the 6th African Network for Evidence-to-Action in Disability (AfriNEAD) Conference that will held in South Africa in December 2020.

Contributors: IDE and MM conceptualised the protocol with significant contributions from EMS and AM. IDE wrote the initial draft which was reviewed by EMS, JK, MZJ, AM and MM. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by funding from the Irish Research Council (IRC) grant number-COALESCE/2019/114.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.World Health Organization World report on disability. 2011 world disability report, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bright T, Wallace S, Kuper H. A systematic review of access to rehabilitation for people with disabilities in low- and middle-income countries. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018;15:2165. 10.3390/ijerph15102165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities (CRPD) [online], 2006. Available: https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities.html [Accessed Feb 2020].

- 4.Sustainable development goals [online], 2020. Available: http://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/sustainable-development-goals.html [Accessed Feb 2020].

- 5.Tebbutt E, Brodmann R, Borg J, et al. Assistive products and the sustainable development goals (SDGs). Global Health 2016;12:79. 10.1186/s12992-016-0220-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khasnabis C, Mirza Z, MacLachlan M. Opening the GATE to inclusion for people with disabilities. Lancet 2015;386:2229–30. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01093-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.WHO Global cooperation on assistive technology (GATE). Geneva: World Health Organization, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 8.WHO Priority assistive products list (APL). Geneva: World Health Organization, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 9.WHO WHO model list of essential medicines: 17th list, March 2011. World Health Organization, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Desmond D, Layton N, Bentley J, et al. Assistive technology and people: a position paper from the first global research, innovation and education on assistive technology (GREAT) Summit. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol 2018;13:437–44. 10.1080/17483107.2018.1471169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith RO, Scherer MJ, Cooper R, et al. Assistive technology products: a position paper from the first global research, innovation, and education on assistive technology (GREAT) Summit. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol 2018;13:473–85. 10.1080/17483107.2018.1473895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Witte L, Steel E, Gupta S, et al. Assistive technology provision: towards an international framework for assuring availability and accessibility of affordable high-quality assistive technology. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol 2018;13:467–72. 10.1080/17483107.2018.1470264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith EM, Gowran RJ, Mannan H, et al. Enabling appropriate personnel skill-mix for progressive realization of equitable access to assistive technology. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol 2018;13:445–53. 10.1080/17483107.2018.1470683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.MacLachlan M, Banes D, Bell D, et al. Assistive technology policy: a position paper from the first global research, innovation, and education on assistive technology (GREAT) Summit. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol 2018;13:454–66. 10.1080/17483107.2018.1468496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.MacLachlan M, Scherer MJ. Systems thinking for assistive technology: a commentary on the GREAT Summit. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol 2018;13:492–6. 10.1080/17483107.2018.1472306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sterman JD. Learning from evidence in a complex world. Am J Public Health 2006;96:505–14. 10.2105/AJPH.2005.066043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holloway C, Austin V, Barbareschi G, et al. Scoping research report on assistive technology: On the road for universal assistive technology coverage Prepared by the GDI Hub & partners for the UK department for international development global disability innvoation hub, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 18.United Nations Malawi, 2020. Available: http://mw.one.un.org/country-profile/

- 19.Malawi Government National policy on equalisation of opportunities for persons with disabilities, 2006. Available: http://www.motpwh.gov.mw/images/Publications/policy/Malawi%20National%20Policy%20on%20Equalisation%20of%20Opportunities%20for%20Persons%20with%20Disabilities.pdf

- 20.Malawi Government National disability mainstreaming strategy and implementation plan 2018-2023. Lilongwe, Malawi, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Loeb M, Eide AH. Living conditions among people with activity limitations in Malawi. A national representative study. SINTEF Report 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Munthali AC. A situation analysis of persons with disabilities in Malawi, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 23.WHO Global perspectives on assistive technology: proceedings of the great consultation 2019 (22–23 August 2019). Vol. 1 Geneva: World Health Organization, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ngomwa PMG. Discourse on intellectual disability and improved access to assistive technologies in Malawi. Front Public Health 2018;6:377. 10.3389/fpubh.2018.00377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coghlan D, Brydon-Miller M. The SAGE encyclopedia of action research. Sage, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boger J, Jackson P, Mulvenna M, et al. Principles for fostering the transdisciplinary development of assistive technologies. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol 2017;12:480–90. 10.3109/17483107.2016.1151953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Albala S, Holloway C, MacLachlan M. Capturing and creating value in the assistive technologies landscape through a Mission-Oriented approach: a new research and policy agenda: AT2030 working paper series, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Brún A, O’Donovan R, McAuliffe E. Interventions to develop collectivistic leadership in healthcare settings: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res 2019;19:72. 10.1186/s12913-019-3883-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Michaud-Létourneau I, Gayard M, Mathisen R, et al. Enhancing governance and strengthening advocacy for policy change of large collective impact initiatives. Matern Child Nutr 2019;15:e12728. 10.1111/mcn.12728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gélinas-Bronsard D, Mortenson WB, Ahmed S, et al. Co-construction of an Internet-based intervention for older assistive technology users and their family caregivers: stakeholders’ perceptions. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol 2019;14:602–11. 10.1080/17483107.2018.1499138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Raelin JA. What are you afraid of: collective leadership and its learning implications. Manag Learn 2018;49:59–66. 10.1177/1350507617729974 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huss T, MacLachlan M. Equity and Inclusion in Policy Processes (EquIPP): a framework to support equity & inclusion in the process of policy development implementation and evaluation. Global Health Press, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mason P, Barnes M. Constructing theories of change: methods and sources. Evaluation 2007;13:151–70. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harrington HJ. Force field analysis. The innovation tools Handbook, volume 2: evolutionary and improvement tools that every Innovator must know, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bourdieu P. The social space and the genesis of groups theory and society, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Amin M, MacLachlan M, Mannan H, et al. EquiFrame: a framework for analysis of the inclusion of human rights and vulnerable groups in health policies. Health Hum Rights 2011;13:1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Loitz CC, Stearns JA, Fraser SN, et al. Network analysis of inter-organizational relationships and policy use among active living organizations in Alberta, Canada. BMC Public Health 2017;17:649. 10.1186/s12889-017-4661-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ryan D, Emond M, Lamontagne M-E. Social network analysis as a metric for the development of an interdisciplinary, inter-organizational research team. J Interprof Care 2014;28:28–33. 10.3109/13561820.2013.823385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kania J, Kramer M. Collective impact: FSG, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 40.MacLachlan M, McVeigh J, Cooke M, et al. Intersections between systems thinking and market shaping for assistive technology: the smart (Systems-Market for assistive and related technologies) thinking matrix. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018;15:2627. 10.3390/ijerph15122627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Equator Network Enhancing the quality and transparency of health research. Available: https://www.equator-network.org/ [Accessed 10 Feb 2020].

- 42.Gray DE. Doing research in the real world. Sage, 2013. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.