Abstract

Introduction

Catatonia arises from serious mental, medical, neurological or toxic conditions. The prevalence range depends on the setting and the range is anything from 7% to 63% in other countries. South African prevalence rates are currently unknown. The proposed study is a quantitative descriptive study using the Bush Francis Catatonia Screening Instrument as a screening tool with a data capturing information sheet to extract clinical information from patient folders. The study will investigate: (1) prevalence of catatonia, (2) clinical and demographic correlates associated with catatonia, (3) predictors of catatonia, (4) response to treatment and (5) subjective experience of catatonia.

Methods and analysis

The setting is an acute mental health unit (MHU) within a regional, general medical hospital in Nelson Mandela Bay, South Africa, which accepts referrals from within the hospital and from outlying clinics. Participants will be recruited from inpatients in the MHU from beginning of September 2020 to end of August 2021. Most admissions are involuntarily, under the Mental Health Care Act of 2002 with an age range of 13 to over 65 years. Participants who screen positive for catatonia will be followed up after discharge for 3 months to measure outcomes. Primary outcomes will include the 12-month prevalence rate of catatonia, descriptive and other data on presentation and assessment of catatonia in the MHU. Secondary outcomes will include data on treatment response, participants’ report of their subjective experience of catatonia and predictors of catatonia. Descriptive statistics, multivariate binomial logistic regression and univariate analyses will be conducted to evaluate associations between catatonia and clinical or demographic data which could be predictors of catatonia. Survival analysis will be used to examine the time to recovery after diagnosis and initiation of treatment. The 95% CI will be used to demonstrate the precision of estimates. The level of significance will be p≤0.05.

Ethics and dissemination

The study has received ethical approval from the Research and Ethics Committees of the Eastern Cape Department of Health, Walter Sisulu University and Nelson Mandela University. The results will be disseminated as follows: at various presentations and feedback sessions; as part of a PhD thesis in Psychology at Nelson Mandela University; and in a manuscript that will be submitted to a peer-reviewed journal.

Keywords: neurology, adult psychiatry, mental health, child & adolescent psychiatry

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study to examine the prevalence of catatonia in South Africa and aims to address the lack of data on prevalence rates of catatonia, presentation, optimal management, predictors and outcomes in this setting.

The triangulation of information sources like the Bush Francis Catatonia Rating Scale, a validated catatonia screening tool, clinical notes, and subjective reports of catatonic episodes from the participants present a unique opportunity to investigate different aspects of catatonia.

The descriptive nature of the study and the limited number of participants could limit the applicability of significant associations between variables regarding cause and effect and the generalisability of findings. The heterogenous nature of catatonia and inter-rater reliability of catatonia screening instruments are another source of potential limitations of the study.

Introduction

In the 1880s, Kraepelin described the prevalence of catatonia as close to 20% in 500 cases.1 Modern-day studies show a range from less than 10% to 63%.1–3 Catatonia is often treated by psychiatrists, even though underlying causes may be other medical conditions such as neurological, infectious, endocrine and substance-induced disorders.1 Grover et al4 described close to 40% of 205 patients who had delirium and two or more catatonic symptoms on the Bush Francis Catatonia Rating Scale (BFCRS).

Luchini et al5 characterised catatonia as an autonomous syndrome, frequently associated with mood disorders but also observed in patients with other conditions including neurological, neurodevelopmental, physical and toxic conditions. Current evidence has provided some answers about the categorisation of catatonia, clinical presentations, interventions and response to treatment.6–8

The current study will investigate the prevalence of catatonia in patients of the Dora Nginza Hospital (DNH) mental health unit (MHU), associated risk factors and response to treatment. Due to the prominent role played by electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) in the treatment of catatonia, the results from this study may have applicability in public mental health planning, and availability of ECT in public hospitals.1

Catatonia in South Africa

There are currently no studies describing the prevalence of catatonia in South Africa (SA), which leaves clinicians blind to the burden of the disease linked to this potentially fatal syndrome. Clinicians may, therefore, be unaware of the importance of the assessment and detection of catatonia, leading to missed opportunities to intervene in what is a highly treatable condition.

White and Robins9 described 17 patients with catatonia in SA who received antipsychotic medication. There was a deterioration in their clinical presentation into neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS). The risk of precipitating NMS in this case series was linked to the administration of antipsychotics. This study also challenged the notion of NMS being viewed as a separate condition to catatonia. Since then, catatonia has not been widely studied in SA, despite the researchers’ observation that it continues to present a significant and sometimes life-threatening challenge. Another study conducted in SA described the treatment of 42 patients with catatonia with ECT.10 The current study represents the first stages of aiming to fill the gap in the existing research with a prospective study on prevalence and predictive data.

Prevalence of catatonia in other parts of the world

Fink and Taylor1 described a rate of catatonia of 10% in acutely ill psychiatric patients and Stuivenga and Morrens2 a rate of 16.9% when applying the -Diagnostic Statistical Manual - 5 (DSM-5) criteria. Conditions found in association with a catatonic presentation have included psychiatric diagnoses like bipolar disorder, delirious mania, psychotic depression, schizophrenia and other medical conditions.2 6 In some instances, the cause leading to catatonia has been less well defined. DSM-5 has captured the multiple possible associations that occur with catatonia by including it as a specifier for mood disorders and schizophrenia or as linked to another medical condition.11 Catatonia also appears as an entity with undefined aetiology under ‘catatonia not otherwise specified’.8

Choice of screening tool and rating scale

In 1996, Bush et al3 designed the Bush Francis Catatonia Screening Instrument (BFCSI) a 14-item scale for screening for catatonia and a 23-item scale for rating severity of catatonia.12 They demonstrated that the scales were reliable and valid tools for diagnosis and evaluation of response to treatment. The scales have a dual utility of screening and measurement of the severity of catatonia. A systematic review of seven catatonia rating scales reported a similar finding when comparing the BFCRS with other tools to screen for catatonia.13 They recommend the BFCRS for routine use because of ease of use, reliability and validity. Wilson et al14 found 300 out of 339 patients with acute medical and psychiatric illness screened positive for catatonia when applying the BFCRS.

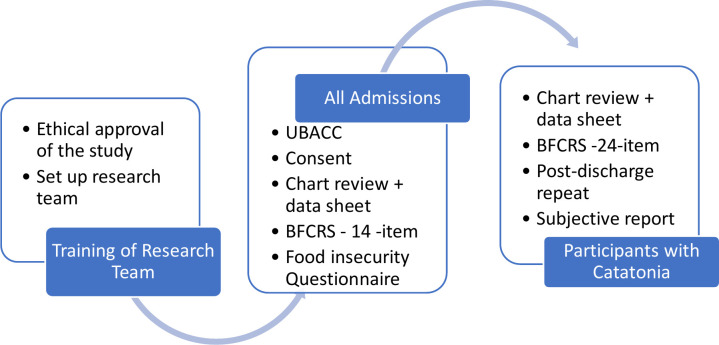

The BFCSI and BFCRS have been used successfully in the MHU as screening and rating scales for the past 9 years in the MHU which is the site of the current study. Other reasons supporting the utility of the scales in this study are: (1) the reported ease of use, (2) reliability, (3) validity as both a screening tool and a measure of severity and (4) its use since 2011 in the study site has not yielded any issues with applicability or appropriateness when used in this clinical setting. Figure 1 reflects the assessment tools and process that will be applied to assess participant and collect data.

Figure 1.

Assessment tools. BFCRS, Bush Francis Catatonia Rating Scale; UBACC, University of California, San Diego Brief Assessment of Capacity to Consent Questionnaire.

Management of catatonia

The biological treatment for catatonia has advanced over the last century, from insulin coma therapy of the early 1930s and Meduna’s use of seizure-inducing camphor oil injections to Cerletti’s first documented use of an electric shock procedure in 1938.1 Available evidence on management of catatonia includes the published works from various researchers.1 6 7 9 14–19 Lorazepam and ECT are the current recommended treatments, irrespective of aetiology. They are effective in most cases.1 7 9 14 17

In both the White and Robins9 and Fricchione et al7 case series, intravenous administration of benzodiazepines (diazepam or lorazepam) was demonstrated as an efficacious treatment for catatonia. Response is seen relatively rapidly, that is, within minutes of administration. Instead of a sedative effect that one observes with the administration of benzodiazepines in non-catatonic patients, those with catatonia tend to ‘wake up’ from stupor or normalise from a state of extreme excitement. In the White and Robins9 study, two patients who did not receive intravenous benzodiazepines died.

The dose range used at the study site tends to be higher and is given more frequently compared with the recommendation in the Rasmussen et al19 paper. This is mainly because patients at the site present at advanced stages of catatonia and tend to respond slowly or not at all when the lower or less frequent doses are employed.

The subjective experience of catatonia

Northoff et al20 conducted a retrospective study on 24 catatonic patients post recovery after a catatonic episode. The patients reported intense emotions which could not be controlled and ambivalence with less focus on their altered movements. Other descriptions of catatonia have stated an extreme fear response characterised by freezing, likened to the defence seen in animals of tonic immobility or freezing in the face of danger.21

This study will investigate the subjective experience of catatonia as described by participants once discharged from the hospital, to shed light on the emotive and cognitive experience of catatonia in the study cohort. This may provide clues on the psychological drivers of the catatonic response and could pave the way for further research into the psychology of the catatonic response.

Aims

This study aims to determine the prevalence of catatonia in an acute MHU in urban SA and research its assessment and management in this setting.

Objectives

The two main research objectives are:

Screening of consenting participants admitted to the MHU in DNH using the BFCSI for catatonia, over a 12-month period from the 1 September 2020 to the end of August 2021, to describe the prevalence of catatonia in this setting.

Description of demographic and clinical information, including response to treatment, in participants diagnosed with catatonia based on their BFCSI scores and clinical assessments performed by the admitting doctor.

Response to treatment will be according to the following parameters: a 50% reduction in signs and symptoms will be considered a response while a 100% reduction will be a considered a full resolution. Conversely, a reduction in symptoms of less than 50% will be regarded as a suboptimal response and a reduction that is more than 50% but less than 100% will be a response but without full resolution. In addition, significant clinical correlates and risk factors in participants with catatonia will be described, and participants with catatonia will be followed up once discharged at 1-month, 2-month and 3-month intervals, to assess outcomes using the BFCSI and information about readmission or recurrence of any episode of mental illness. The association that will be looked at is between catatonia and demographic or clinical correlates such as age, gender, DSM-5 diagnosis, substance use, vitamin 12 deficiency and food insecurity and other co-occurring medical conditions. Participants’ experience of catatonia once it has resolved will also be described.

Research design

This is a prospective, descriptive triangulation study using mixed quantitative and qualitative methods. An exploratory qualitative aspect will investigate the emotive and cognitive subjective experience of participants with catatonia to establish a direction for further research. This is because there are currently limited data available on the subjective experience of catatonia, with most research focusing on quantitative aspects.

The quantitative elements of the study will include data collected from participant files of BFCSI scores on admission, with additional clinical and demographic information collected via a predesigned datasheet (see online supplemental appendix 1). The qualitative element will describe the participant’s reported experience of the catatonic episode, post discharge.

bmjopen-2020-040176supp001.pdf (144.9KB, pdf)

Methods and analysis

The study will take a positivist paradigm approach to investigate the potential causal relationships between catatonia and different variables via correlational studies.22 Creswell23 described the positivist’s approach as an attempt to identify causes, which influence outcomes, the aim being to formulate laws, thus yielding a basis for prediction and generalisation. In the current study, deductive reasoning will be applied to data collected through (1) direct observation and (2) quantitative and qualitative approaches, to identify associations with catatonia, causal relationships, and possibly, predictors of catatonia.22

Sources of information that will be used for triangulation include: the participants’ BFCSI/ BFCRS scores (see online supplemental appendix 2) and clinical notes; field notes taken by the research team during direct observation and interviews; and participant and relative interviews focusing on response to treatment, food insecurity and the subjective experience of catatonia. Additionally, the mixed methods nature of the study will enable the generation of both objective (as documented by treating and research teams) and subjective data regarding the experience of catatonia. This type of triangulation is an important tool for meeting the goals of this study while facilitating a holistic assessment of catatonia in this cohort.

bmjopen-2020-040176supp002.pdf (274.4KB, pdf)

The study process and outline

Two research assistants (RAs) with a background in health will be recruited to assist the researcher with fieldwork. A health background is necessary to understand the medical terminology that is used in the clinical notes and screening tools. A part-time administrative assistant will be contracted to assist with data capturing and collation. Fieldwork will include the recruitment of participants and collection of data by the researcher and RAs. There will be a limited follow-up component that extends to up to 3 months following discharge from the hospital.

The RAs will be trained by the researcher on:

Application of the BFCSI and BFCRS to ensure they are knowledgeable about the screening tool and its interpretation.

Assessment of capacity to consent using the University of California, San Diego Brief Assessment of Capacity to Consent Questionnaire (UBACC).

The UBACC has been applied successfully in the Eastern and Western Cape in study cohorts recruited from inpatient mental health institutions.24 25

The inter-rater reliability (IRR) of the BFCRS was demonstrated to be good (α=0.779) in a study looking at four different instruments to assess for catatonia.26 In the planned study, training that will be provided by the lead researcher to the RAs on the use of the BFCSI/BFCRS will be through:

Explaining the meaning of terms used in the BFCSI/BFCRS to describe clinical signs and symptoms of catatonia.

Providing a demonstration of how to elicit and document the 14-items and 23-items in the BFCSI/BFCRS, and how to capture the relevant information accurately onto the data capturing form.

Ensuring RAs start with practice participants initially under direct observation of the lead researcher, before starting the actual recruitment. An IRR in the range of (α=0.61–0.8) during the practice scoring will be deemed acceptable for RAs to proceed to the scoring of study participants.

IRR will also be addressed through ensuring that everyone has a similar understanding of all items to be rated in the screening tool and how these should be recorded.

The researcher and RAs will assess participants who meet the inclusion criteria for capacity to consent, using the UBACC. All those with intact capacity to consent will be requested to consider entering the study (see online supplemental appendices 3 and 4). For participants who may be assessed as lacking the capacity to consent, their closest relatives or guardians will be requested to consent on their behalf through proxy consent (proxy consent and its ethical application are further discussed in the section ‘Ethics and dissemination’). Additionally, in those assessed to lack capacity to consent, such capacity will be reviewed weekly to allow for further re-engagement on their consent to take part in the study, the ultimate aim being to change from proxy consent to personal consent as soon as potential participants have regained capacity. Data collected about any participant who chooses to withdraw from the study will be removed from the study data sets and destroyed.

bmjopen-2020-040176supp003.pdf (160.8KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-040176supp004.pdf (152.1KB, pdf)

The research team will collect data from the clinical files of consenting participants on BFCSI/BFCRS scores and additional descriptive and demographic information as guided by the study questionnaire and study protocol. The completed data capturing forms will be submitted to the administrative assistant for data collation and entry into a spreadsheet at the end of each week. The assessment of new admissions will be daily on weekdays with the expectation being to conduct daily screening or within the first 48 hours at least. Information on clinical presentation of patients admitted over weekends will be supplemented from the clinical folders. In cases where the researcher or RAs identify possible missed catatonia, the treating doctor will be provided with any additional information picked up during the participants’ assessment to allow for a review of the patient’s clinical case and management.

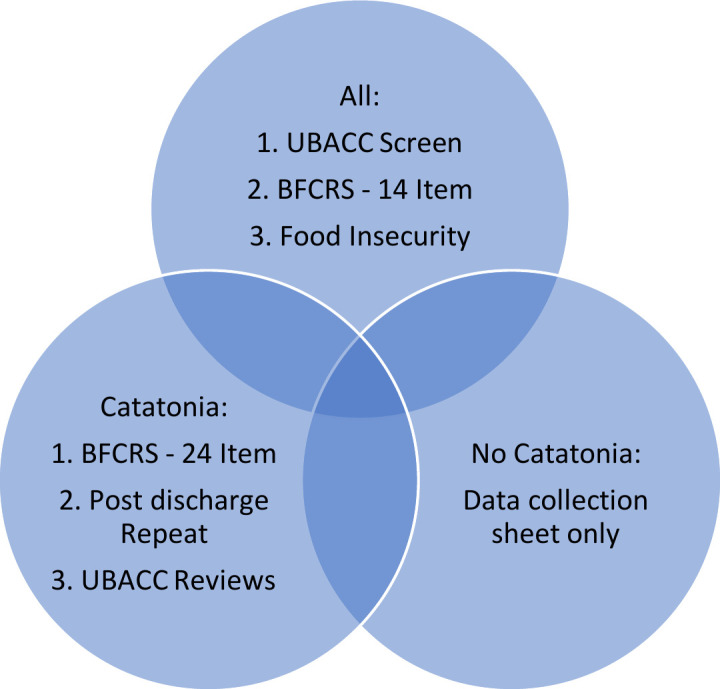

During the limited follow-up period, the researcher and RAs will repeat the BFCSI assessment and conduct face-to-face interviews with participants regarding their experience of catatonia at 1 month, 2 months and 3 months post discharge. Recurrence of symptoms or readmissions since the last discharge will be documented. The participant’s willingness to continue with the study will be reviewed during every visit to ensure their consent remains valid throughout. Figure 2 shows a summary of the study process that will be followed.

Figure 2.

The study process. BFCRS, Bush Francis Catatonia Rating Scale; UBACC, University of California, San Diego Brief Assessment of Capacity to Consent Questionnaire.

Setting

The setting will be a 35-bed acute MHU in DNH, a general hospital in the Eastern Cape Province in SA. The hospital is in Zwide, in the iBhayi area of Port Elizabeth which has a population of over one million within an urban area that has a high morbidity of mental illness.27 Close to 70% of the population comprises working age adults between 15 and 64 years and the city has an unemployment rate of close to 30%.27 Zwide itself has a population of 238 000.28 Health services in the hospital include obstetrics and gynaecology, paediatrics, basic surgical, internal medicine and family medicine. The MHU is an acute inpatient unit offering 24 hours care to persons who present with acute mental illness requiring inpatient treatment. It accepts referrals from all the other hospital departments including the accident and emergency department, as well as referrals from primary care clinics and district hospitals in the nearby vicinity. The usual period of admission ranges anything from 3 days to a few weeks.

All cases of suspected catatonia, from any of the referring departments, are discussed with the MHU team and prioritised for admission into the unit. Any treatment given thereafter is discussed with the MHU team and documented in the patient’s folder.

Sampling

Convenience sampling of all patients admitted to the MHU over a 12-month period (September 2020 to August 2021) will be undertaken. Contact details of all consenting participants who screen positive for catatonia will be entered into a database to enable contact for future follow-up at the end of 1 month, 2 months and 3 months post discharge. This information will be password encrypted.

The number of patients expected to be admitted during the study period is around 1000 based on previous unit stats over the last 3 years and adjusted down slightly to accommodate the effect of the COVID-19 outbreak on hospital admissions. The margin of error or CI will be set at 95% and the SD will be set at 0.05. To determine the total sample size required, the formula: n=N/(1+Ne2) will be used and yields a minimum sample size of 286 subjects. A further 20% (57) will be added to account for data entry errors and non-responses. The appropriate sample size of participants to be screened for the prevalence of catatonia in the unit is 343.

Participants

Most people admitted to the DNH MHU are involuntary admissions under the Mental Health Care Act of 2002.29 Age of admission ranges from 13 to over 65 years because there are no child, adolescent or geriatric inpatient-specific services in the region.

Inclusion criteria

All patients admitted to the unit during the study period will be eligible for inclusion.

Those who screen positive for two or more catatonic signs and symptoms on the BFCSI will be included during the follow-up period for the qualitative part of the study.

Exclusion criteria

Refusal to take part in the study, whether through the direct patient consent process or the proxy consent process, will result in the exclusion of the patient.

Methods of assessment and measurement

The BFCSI is a 14-item scale (see online supplemental appendix 2) that is used to screen for catatonia and the BFCRS is a 21-item scale used to rate severity.11 The BFCSI is used on initial assessment and the full BFCRS is used to determine severity. Participants’ responses to the standard interventions of intravenous lorazepam administration or ECT will be documented by the admitting doctor in the case notes. The research team will then capture this information on a predesigned data collection sheet. When a patient presents with two or more positive items on the BFCSI, they are deemed catatonic and further management is guided by the unit protocol. A lorazepam infusion of 1 mg or 2 mg is administered and a response of 50% or greater reduction in the scale score verifies the diagnosis although absence of verification does not exclude catatonia. The research team will capture information on participant’s BFCSI/BFCRS scores and other clinical data on a predesigned data collection sheet.

The clinical data that will be collected include current psychiatric diagnosis, co-occurring medical conditions, any other treatment administered, history of substance use, history of previous catatonic episodes, vital signs like temperature on admission, blood pressure, pulse, investigations like creatine kinase, iron levels, thyroid function tests, urea and electrolytes or any other relevant clinical investigations reflected in the file which are noted by the treating team to be of relevance to the current admission, and food insecurity. The participants’ case notes will form a primary source of information as well as direct observation of the participants. Additional information will be sought from relatives if the participant is unable to respond adequately to information required on food security questions due to the severity of catatonic symptoms, or in those who are unable to provide the additional information for whatever other reason.

Regarding social determinants of mental health, current evidence indicates that those who are poor or disadvantaged suffer disproportionately from common mental disorders and their adverse consequences.30 The strength of the association with poverty has at times varied depending on the type of poverty measure used. Food insecurity as a poverty measure is one of the factors with a consistent and strong association with common mental disorders.31 In this study, the administration of a food security questionnaire will be used to assess the correlation of poverty to catatonia. Two food insecurity questions are drawn from the United Stated Department of Agriculture’s 18-question Household Food Security Scale.32 They make up The Hunger Vital Sign Questionnaire, a validated two-question food insecurity screening tool used in the clinical setting. The questions are:

Within the past 12 months, we worried whether our food would run out before we got money to buy more.

Within the past 12 months, the food we bought just did not last and we did not have money to get more.

During the follow-up period, participants will be asked to describe their experience of the catatonic episode as well as their perception of recovery.

Expected outputs

The 12-month prevalence rate of catatonia.

Descriptive and other data on presentation and assessment of catatonia in the DNH unit.

Data on treatment response, short-term outcomes and subjective experience of catatonia.

Predictors for catatonia based on clinical correlates and other descriptive data collected.

Recommendations and guidelines for the management of catatonia and possible prevention strategies.

Data management and analysis

Quantitative data collected will be summarised using descriptive statistics. Categorical variables will be presented using frequency tables, percentages and graphs. Two or more categorical variables will be compared using contingency tables (eg, 2×2 table) and the expected frequencies will be calculated to determine the type of test best suited to determine the extent of any identified relative associations. If the expected frequencies in all cells are ≥5, then the χ2 test will be used and if the expected frequencies are <5 in any cells, then the Fisher’s exact test will be used.

Binomial logistic regression will also be conducted to determine the predictors of catatonia and to estimate the risk ratio. If the numerical data are not normally distributed, non-parametric statistics will be used (median and IQR). The best fitting model of multivariate analysis will be chosen through forward selection of model building. The model with the lowest Bayesian information criterion will be selected as the better model and the 95% CI will be used to estimate the precision of estimates. Survival analysis will be used to determine the time to recovery and the HR (ie, the total number and timing of each event indicating relapse in this study) will be reported for this purpose.

Qualitative data collated during the follow-up period will be analysed to elucidate the subjective experience of catatonia in this cohort. Aspects of the thematic analysis presented by Braun and Clarke33 will be applied to identify themes. Themes will be identified through a framework approach identifying word repetition, local expressions, metaphors and similarities, differences and keywords. A tentative hypothesis and theory regarding the experience of catatonia will be presented based on emergent themes. Data collected during the quantitative and qualitative segments of the study will be analysed separately but compared for congruency of reported information to enhance data integration.

In summary, data integration will be in the form of:

Converting information gathered from the quantitative aspects of the study into numerical information that can be processed through application of statistical methods to test for correlations and associations.

Identifying common themes through field notes taken when interviewing participants during the outpatient stage of the study.

Assessing congruency between common themes about the subjective experience of catatonia as described by participants and commonly identified presenting symptoms as highlighted in case notes and listed in the data collection sheet. The advantage of this approach is that it strengthens the validity and reliability of the study.

Patient and public involvement

No formal patient advisory committee was set up and there was no patient or public involvement in the design and planning of the study.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics clearance has been granted for the study by the Eastern Cape Department of Health Ethics Committee (see online supplemental appendixs 5 and 6), the Walter Sisulu University Research and Ethics Committee and the Nelson Mandela University Human Research Ethics Committee (see online supplemental appendix 7). The study does not have any intervention arm.

bmjopen-2020-040176supp005.pdf (528.8KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-040176supp006.pdf (172.6KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-040176supp007.pdf (3MB, pdf)

All patients admitted to the unit will be presented with an information leaflet on the study in English or Xhosa. Consent for inclusion in the study will be obtained from all participants who have the capacity to consent, which will be determined through application of the UBACC. Proxy consent will be sought from a relative or guardian for all patients who lack the capacity to consent or are minors between the ages of 13 and 18 years of age. The use of proxy consent in mental health research is applicable for those who lack the capacity to consent and the nearest relative or guardian consents on their behalf. It is permissible within the mental healthcare setting due to the challenges with capacity to consent that may exist in patients with acute mental illness.34 Proxy consent ensures that respondents’ rights are guarded while making it possible to include individuals or groups who may potentially benefit from scientific advances gained from research. This approach is also supported by the Helsinki Declaration on ethical research which states that ‘for a research subject who is legally incompetent, physically or mentally incapable of giving consent or is a legally incompetent minor, the investigator must obtain informed consent from the legally authorised representative in accordance with applicable law’.35 The Department of Health Guidelines on ethics in health research similarly state that persons should not be excluded unfairly based on discrimination or disability.36

The Mental Healthcare Act (MHCA) of 2002 also makes a reference as to whom may be considered an associate of a patient admitted under the MHCA: for example, a spouse, next of kin, partner, associate, parent or guardian.29 A similar approach will be taken for this research. All data will be anonymised and stored under lock and key, with access granted to the research team only.

Dissemination of results

The results will be presented at feedback sessions with the Hospital Board, Eastern Cape Department of Health and at national and international congresses and may be used to compile guidelines on assessment and management of catatonia in the region. They will also be compiled as a thesis, which will be submitted for examination for a PhD in Psychology at Nelson Mandela University. A research report based on the study results will be submitted to peer-reviewed journals to be considered for publication.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Sikhumbuzo Mabunda for the valuable comments and assistance provided in the data analysis section.

Footnotes

Contributors: ZZ conceived the idea and devised the project and its main conceptual ideas assisted by SvW and MF. LS and JC supervised the development of this manuscript and provided editorial input.

Funding: This work was supported by the South African Medical Research Council (SAMRC), grant tracking number 2017SAMRC0SIR0000157977 and an educational grant from the Health and Welfare Sector Education and Training Authority (2018/2019HWSETA219986789).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

References

- 1.Fink M, Taylor MA. Catatonia: a clinician’s guide to diagnosis and treatment. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stuivenga M, Morrens M. Prevalence of the catatonic syndrome in an acute inpatient sample. Front Psychiatry 2014;5:174. 10.3389/fpsyt.2014.00174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bush G, Fink M, Petrides G, et al. Catatonia. I. rating scale and standardized examination. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1996;93:129–36. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1996.tb09814.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grover S, Ghosh A, Ghormode D. Do patients of delirium have catatonic features? an exploratory study. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2014;68:644–51. 10.1111/pcn.12168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luchini F, Medda P, Mariani MG, et al. Electroconvulsive therapy in catatonic patients: efficacy and predictors of response. World J Psychiatry 2015;5:182–92. 10.5498/wjp.v5.i2.182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fink M, Taylor MA. The many varieties of catatonia. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2001;251 Suppl 1:I8–13. 10.1007/PL00014200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fricchione GL, Cassem NH, Hooberman D, et al. Intravenous lorazepam in neuroleptic-induced catatonia. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1983;3:338???342–42. 10.1097/00004714-198312000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tandon R, Heckers S, Bustillo J, et al. Catatonia in DSM-5. Schizophr Res 2013;150:26–30. 10.1016/j.schres.2013.04.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.White DA, Robins AH. An analysis of 17 catatonic patients diagnosed with neuroleptic malignant syndrome. CNS Spectr 2000;5:58–65. 10.1017/S1092852900013419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Odayar K, Eloff I, Esterhuysen W. Clinical and demographic profile of catatonic patients who received electroconvulsive therapy in a South African setting. S Afr J Psych 2018;24:1–5. 10.4102/sajpsychiatry.v24i0.1100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM- 5. Washington: American Psychiatric Association, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sienaert P, Dhossche DM, Vancampfort D, et al. A clinical review of the treatment of catatonia. Front Psychiatry 2014;5:181. 10.3389/fpsyt.2014.00181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sienaert P, Rooseleer J, De Fruyt J. Measuring catatonia: a systematic review of rating scales. J Affect Disord 2011;135:1–9. 10.1016/j.jad.2011.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilson JE, Niu K, Nicolson SE, et al. The diagnostic criteria and structure of catatonia. Schizophr Res 2015;164:256–62. 10.1016/j.schres.2014.12.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fink M, Taylor MA. Electroconvulsive therapy: evidence and challenges. JAMA 2007;298:330–2. 10.1001/jama.298.3.330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fink M. What was learned: studies by the Consortium for research in ECT (core) 1997-2011. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2014;129:417–26. 10.1111/acps.12251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Petrides G, Fink M, Husain MM, et al. Ect remission rates in psychotic versus nonpsychotic depressed patients: a report from core. J Ect 2001;17:244–53. 10.1097/00124509-200112000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosebush PI, Hildebrand AM, Furlong BG, et al. Catatonic syndrome in a general psychiatric inpatient population: frequency, clinical presentation, and response to lorazepam. J Clinical Psychiatry 1990;51:357–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rasmussen SA, Mazurek MF, Rosebush PI. Catatonia: our current understanding of its diagnosis, treatment and pathophysiology. World J Psychiatry 2016;6:391–8. 10.5498/wjp.v6.i4.391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Northoff G, Krill W, Wenke J, et al. [The subjective experience in catatonia: systematic study of 24 catatonic patients]. Psychiatr Prax 1996;23:69–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moskowitz AK. “Scared stiff”: catatonia as an evolutionary-based fear response. Psychol Rev 2004;111:984–1002. 10.1037/0033-295X.111.4.984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scotland J. Exploring the philosophical underpinnings of research: relating ontology and epistemology to the methodology and methods of the scientific, interpretive, and critical research paradigms. English Language Teaching 2012;5:9–16. 10.5539/elt.v5n9p9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Creswell JW. Research design: qualitative and mixed methods approaches. London: Sage, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Campbell MM, Susser E, Mall S, et al. Using iterative learning to improve understanding during the informed consent process in a South African psychiatric genomics study. PLoS One 2017;12:e0188466. 10.1371/journal.pone.0188466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Campbell MM, de Vries J, Mqulwana SG, et al. Predictors of consent to cell line creation and immortalisation in a South African schizophrenia genomics study. BMC Med Ethics 2018;19:72. 10.1186/s12910-018-0313-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sarkar S, Sakey S, Mathan K, et al. Assessing catatonia using four different instruments: inter-rater reliability and prevalence in inpatient clinical population. Asian J Psychiatr 2016;23:27–31. 10.1016/j.ajp.2016.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Republic of South Africa, c2011 Statistics South Africa: Nelson Mandela bay, 2020. Available: http://www.statssa.gov.za/?page_id=993&id=nelson-mandela-bay-municipality

- 28.Republic of South Africa Statistics South Africa: statistics South Africa to release the quarterly labour force survey (QLFS), 2nd quarter 2019, 2019. Available: http://www.statssa.gov.za/?p=12358

- 29.Government Gazette, Republic of South Africa . Mental health care act 2002 (act no. 17 of 2002) general regulations, 2004. Available: https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/a17-02.pdf

- 30.World Health Organization Social determinants of mental health. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2020. https://www.who.int/mental_health/publications/gulbenkian_paper_social_determinants_of_mental_health/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lund C, Breen A, Flisher AJ, et al. Poverty and common mental disorders in low and middle income countries: a systematic review. Soc Sci Med 2010;71:517–28. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.04.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.American Academy of Pediatrics Addressing food insecurity: a toolkit for pediatricians, 2020. Available: https://frac.org/wp-content/uploads/frac-aap-toolkit.pdf

- 33.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006;3:77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mason S, Barrow H, Phillips A, et al. Brief report on the experience of using proxy consent for incapacitated adults. J Med Ethics 2006;32:61–2. 10.1136/jme.2005.012302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.World Medical Association World medical association declaration of Helsinki. Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. Bull World Health Organ 2001;79:373–4. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Department of Health, Republic of South Africa . Ethics in health research: principles, processes and structures, 2nd edition. 2nd edition Pretoria: National Department of Health, 2020. https://www.ru.ac.za/media/rhodesuniversity/content/ethics/documents/nationalguidelines/DOH_(2015)_Ethics_in_health_research_Principles,_processes_and_structures.pdf [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2020-040176supp001.pdf (144.9KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-040176supp002.pdf (274.4KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-040176supp003.pdf (160.8KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-040176supp004.pdf (152.1KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-040176supp005.pdf (528.8KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-040176supp006.pdf (172.6KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-040176supp007.pdf (3MB, pdf)