Abstract

Introduction

Asthma, a well-known chronic respiratory disease, is common worldwide. This study aimed to assess the quality of life in bronchial asthma patients and to determine the factors leading to poor quality of life among these patients.

Materials and methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted at a public sector hospital. The sample size was calculated as 134, with a nonprobability consecutive sampling technique. The Ethical Review Committee approved the study protocol. Demographic and asthma quality of life data were collected via a questionnaire. Data were analyzed IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 19.0 (Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.). Multivariate logistic regression was performed to observed the effect of these variables on the poor quality of life. A regression coefficient and odds ratio with a confidence interval of 95% and P-value ≤ .05 were taken as significant.

Results

The average age of patients was 40.6 ± 9.5 years. In this study, 96 of 134 patients (71.4%) with bronchial asthma reported a poor quality of life. In the univariate analysis, advanced age (≥ 40 years), obesity, being female, family history of asthma, pets at home, and moderate severity of asthma significantly contributed to poor quality of life. Multivariate logistic regression was performed, and it was observed that advanced age (≥ 40 years), being female, a pet at home, and moderate severity of asthma were four to 13 times more likely to predict a poor quality of life for patients with bronchial asthma.

Conclusions

The severity of asthma significantly contributed to poor quality of life. Health facilitators should look into the causes of such risk to increase the perception of health-related quality of life (HRQoL) among asthma patients.

Keywords: asthma, bronchial asthma, copd, hrqol

Introduction

Asthma, a well-known chronic respiratory disease, is one of the most common global problems, with an estimated total of 300 million affected individuals, comprising all age groups and exerting a significant burden on patients and their families [1]. The asthma load report by the Global Initiative for Asthma indicates that the prevalence of asthma ranges from 1% to 18% of the population [1,2]. Patients diagnosed with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) have significantly reduced health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and account for 250,000 deaths per year worldwide [3]. HRQoL is a vital factor in pulmonary illnesses [4], and COPD can reduce HRQoL via physical and psychosocial complications [5].

Though asthma negatively impacts the quality of life of the patients, the core influencing factors are not fully understood. The most severe forms of asthma are integrated with a poor HRQoL with nonlinear coordination [6,7]. Factors need to be identified to improve HRQoL [6-8]. Motaghi-Nejad et al. found that asthma has a negative influence on the HRQoL in 48.3% of patients [9]. Gonzalez-Barcala et al. analyzed factors associated with a poor HRQoL like obesity (24.9%), being female (28%), advanced age (21.7%), low education (56.5%), family history of asthma (24.4%), moderate persistent severity of asthma (36.4%), being a smoker (23.3%), and pets at home (24.4%) [10]. HRQoL interventions are integrated with several clinical trials [11-13]. Furthermore, no local study data on effective pharmacotherapy are available. The study aims to assess the relationship between asthma severity and HRQoL and determine the primary factors in asthma that impact patient quality of life.

Materials and methods

This cross-sectional study was held at the outpatient department of a public sector hospital. The sample size (N=134) was estimated on the prevalence rate of factors (12.7%) through the help of the World Health Organization sample size calculator [12]. A confidence interval (CI) of 95% and a non-probability consecutive sampling technique was used during data collection. All patients with mild to moderate persistent asthma were classified according to the tool defined by the Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma [13]. Patients ranged from 18 to 60 years in age and were of either sex. Patients had clinical stability, no exacerbation, and had asthma for at least six months and treatment for the prior two weeks. Patients unwilling to participate were excluded from the study along with patients with acute severe/persistent asthma and those with a history of severe respiratory tract infection/chronic rhino-sinusitis, pulmonary tuberculosis, or lung cancer the past month. Ethical approval was granted from the Institutional Ethical Review Committee.

All subjects fulfilling the eligibility criteria were enrolled after providing informed verbal and written consent. The principal investigator interviewed the patients in the outpatient department of a public hospital. Each interview lasted 10 to 20 minutes. Data were collected on a proforma and included basic demographic information such as age, sex, body mass index (BMI), duration of disease, duration of treatment, place of residency, occupation, education, and economic status, addiction, smoking status, the severity of asthma, and pet exposure. A predesigned Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire (AQLQ) was used with permission [11-16]. This scale, developed in Canada, assesses the quality of life of asthmatic patients and includes physical and emotional health, subjective health status, and domains of functioning that are important to patients. The data were entered and analyzed by using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 19.0 (Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.). The mean and standard deviation was calculated for age, BMI, duration of asthma, duration of treatment, and AQLQ score. The frequency and percentage were calculated for sex, the severity of asthma, residency, quality of life (poor/satisfactory), and other factors (BMI, age, sex, education, economic status, smoking habits, pets at home, and asthma severity). Effect modifiers like age, sex, residency, duration of disease, duration of treatment, and the severity of asthma were controlled through multivariate analysis instead of stratification techniques. Multivariate logistic regression was performed to observe the effect of these variables on the quality of life. The regression coefficient and odds ratio, with a 95% CI, were reported. A P-value ≤ .05 was considered significant.

Results

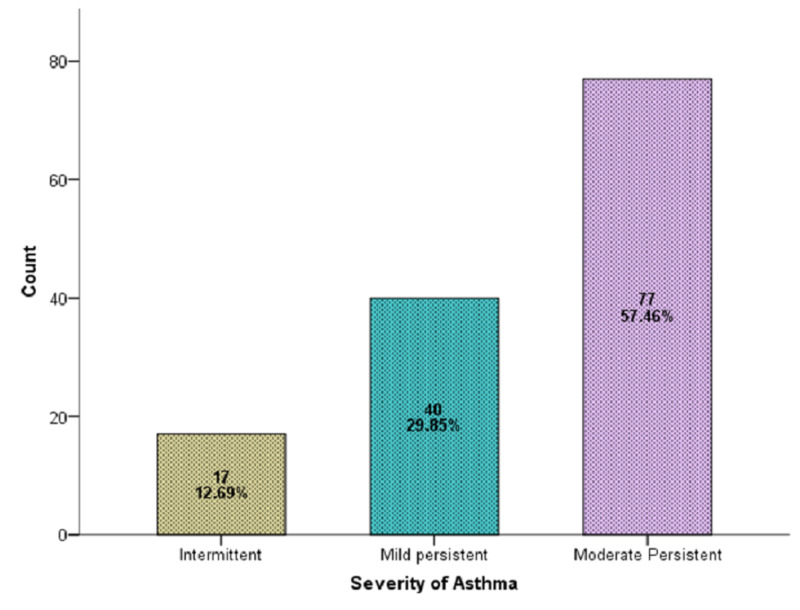

A total of 134 diagnosed cases of asthma for at least six months and on treatment for at least two weeks were selected in this study. The average age of the patients was 40.6 ± 9.5 years (95% CI: 39.04 to 42.29). Average BMI, duration of asthma, duration of treatment, AQLQ score is presented in Table 1. There were 79 (58.96%) men and 55 (41.04%) women. Intermittent asthma was found in 12.69% of patients, mild asthma in 29.85%, and moderate asthma in 57.46% (Figure 1).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of the characteristics of patients.

Abbreviations: AQLQ, Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire; BMI, body mass index

| Variables | Mean | 95% Confidence Interval for Mean | Standard Deviation | |

| Upper Bound | Lower Bound | |||

| Age (years) | 40.6 | 39.0 | 42.2 | 9.5 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.38 | 23.66 | 25.11 | 4.19 |

| Duration of asthma (months) | 14.50 | 13.67 | 15.33 | 4.87 |

| Duration of treatment (weeks) | 6.43 | 5.88 | 6.99 | 3.24 |

| AQLQ Score | 3.84 | 3.52 | 4.16 | 1.87 |

Figure 1. Severity of asthma (n=134).

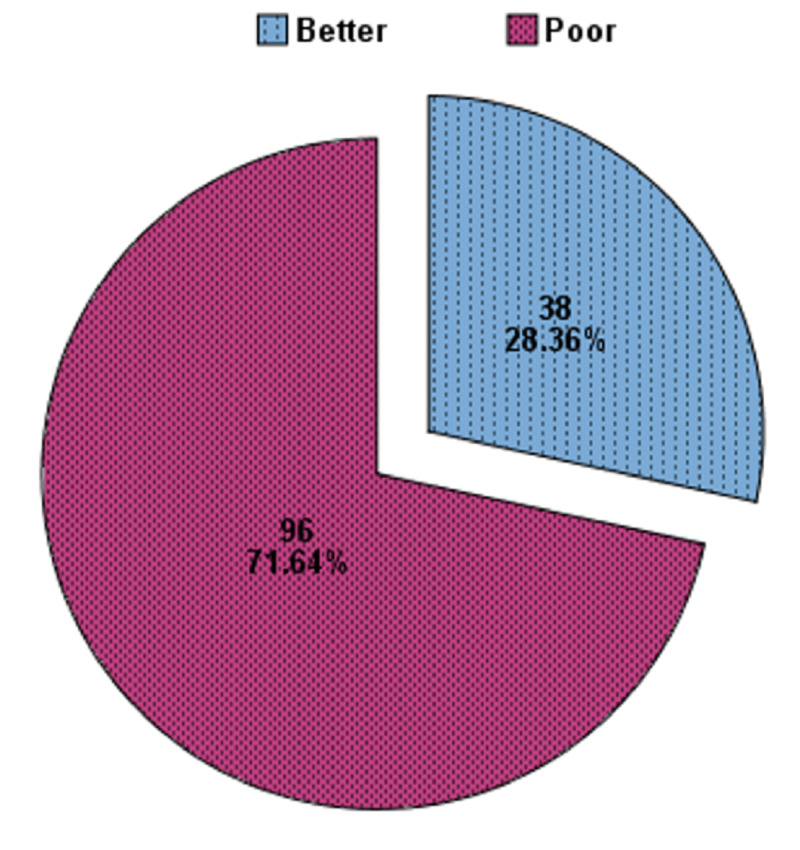

Ninety-six of 134 (71.4%) patients were observed with a poor quality of life in bronchial asthma (Figure 2). Table 2 presents factors contributing to poor quality of life in bronchial asthma patients. An age of 40 years or older, obesity, being female, pets at home, and moderate severity of asthma significantly contributed to poor quality of life while low educational status, family history of asthma, and smoking habits did not have a significant impact. Multivariate logistic regression revealed that advanced age (≥ 40 years), being female, a pet at home, and moderate severity of asthma were four to 13 times more likely to predict a poor quality of life in bronchial asthma (Table 3). The model specification of the logistic regression is also presented in Table 3.

Figure 2. Quality of life in bronchial asthma patients (n=134).

Table 2. Factors leading to poor quality of life in bronchial asthma patients.

Abbreviation: BMI, body mass index

| Factors | N | Quality of life | P-value | |

| Poor | Better | |||

| Advanced age | ||||

| ≥40 Years | 73 | 61 (83.6%) | 12 (16.4%) | .001 |

| <40 Years | 61 | 35 (57.4%) | 26 (42.6%) | |

| Obesity | ||||

| BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 | 52 | 47 (90.4%) | 5 (9.6%) | .0005 |

| BMI < 25 kg/m2 | 82 | 49 (59.8%) | 33 (40.2%) | |

| Gender | ||||

| Men | 79 | 48 (60.8%) | 31 (39.2%) | .001 |

| Women | 55 | 48 (87.3%) | 7 (12.7%) | |

| Education Level | ||||

| Uneducated | 88 | 67 (76.1%) | 21 (23.9%) | .100 |

| Educated | 46 | 29 (63%) | 17 (37%) | |

| Socioeconomic Status | ||||

| Low | 56 | 43 (76.8%) | 13 (23.2%) | .383 |

| Middle | 74 | 51 (68.9%) | 23 (31.1%) | |

| High | 4 | 2 (50%) | 2 (50%) | |

| Family History of Asthma | ||||

| Yes | 66 | 53 (80.3%) | 13 (19.7%) | .028 |

| No | 68 | 43 (63.2%) | 25 (36.8%) | |

| Smoker | ||||

| Yes | 59 | 46 (78%) | 13 (22%) | .150 |

| No | 75 | 50 (66.7%) | 25 (33.3%) | |

| Pets at home | ||||

| Yes | 42 | 39 (92.9%) | 3 (7.1%) | .0005 |

| No | 92 | 57 (62%) | 35 (38%) | |

| Severity of Asthma | ||||

| Moderate | 77 | 25 (43.9%) | 32 (56.1%) | .0005 |

| Mild and intermitted | 57 | 71 (92.2%) | 6 (7.8%) | |

Table 3. Multivariate logistic regression model to predict a poor quality of life in bronchial asthma.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; SE, standard error.

Dependent variable = Quality of Life (Poor, Better)

Model Summary: Model Accuracy = 90.3%; -2 Log likelihood = 83.14; Cox & Snell R Square = 43.6%; Nagelkerke R Square= 62.5%

| Variables | Regression Coefficient | SE | P-value | OR | 95% CI for OR | |

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| Advance Age (≥ 40 Years) | 1.387 | .592 | .019 | 4.00 | 1.25 | 12.76 |

| Obesity (BMI ≥25 kg/m2) | .844 | .671 | .208 | 2.32 | 0.62 | 8.65 |

| Female Gender | 1.732 | .727 | .017 | 5.65 | 1.36 | 23.50 |

| Uneducated Patients | .617 | .666 | .354 | 1.85 | 0.50 | 6.84 |

| Low Socioeconomic status | .638 | .683 | .350 | 1.89 | 0.49 | 7.21 |

| Family History of Asthma (Yes) | .862 | .575 | .134 | 2.36 | 0.76 | 7.30 |

| Smoker (Yes) | 1.112 | .688 | .106 | 3.04 | 0.79 | 11.71 |

| Pet At Home(Yes) | 1.806 | .821 | .028 | 6.08 | 1.21 | 30.45 |

| Residency (Rural) | .268 | .601 | .656 | 1.30 | 0.40 | 4.24 |

| Duration of Asthma (Months) | .087 | .080 | .278 | 1.09 | 0.93 | 1.27 |

| Duration of Treatment of Asthma (weeks) | -.046 | .097 | .636 | 0.95 | 0.78 | 1.15 |

| Severity of Asthma (Moderate) | 2.617 | .672 | .0005 | 13.68 | 3.66 | 51.12 |

| Constant | -4.669 | 1.810 | .010 | .009 | ||

Discussion

Our patient population age and male-to-female ratio were similar to the demographics of similar studies reported by Gonzalez-Barcala [10] and Nalina and Chandra [17].

Most of our patients (71.4%) reported a poor quality of life with bronchial asthma, which was higher than the percentage of those reporting a poor quality of life in the report by Motaghi-Nejad et al., who found that only 48.3% of patients reported a poor quality of life [9]. The reasons for the higher incidence of poor quality of life in our patients were likely due to our study population’s more advanced age (> 40 years) and lower educational and socioeconomic status than those in Motaghi-Nejad et al.’s patient population.

In the present study, advanced age ≥ 40 years, obesity, being female, family history of asthma, pets at home, and moderate severity of asthma was significantly contributors to poor quality of life. Gonzalez-Barcala et al. reported similar findings but also found that a low education level (56.5%) and smoking status (23.3%) were associated with a poor HRQoL. These findings were consistent with our results [10]. However, unlike Gonzalez-Barcala et al., we did not address the impact of recurrent admissions on the HRQoL [10].

Even though no association was seen among age and HRQoL [18,19], several authors have noticed a decrease in HRQoL with increasing age [20,21]. Many factors are associated with age and illness, including immunosenescence [22-24]. As comorbidities increase with age, they contribute to the symptomatology and even prohibit the use of certain asthma medications due to contraindications [22,23].

Lower health proficiency has been reported in patients with a lower education level. Likewise, lower numerical aptitudes, progressively postponed determination of asthma, more unfortunate access to social status, or poorer health status could add to the decrease in HRQoL seen in these patients [25,26].

Our study was limited in that the research reflects patients from a single hospital, which means our findings may not be generalizable across a wider geographic population. It is, therefore, recommended that similar studies be conducted in other locations across Pakistan to gain a more accurate assessment of a broad population.

Conclusions

This study identified several factors responsible for the poor quality of life of patients with asthma. These factors consisted of advanced age, increased asthma severity, poor control of asthma, low education level, and low socioeconomic status. Given the relevant impact of economic and education levels, it is essential that health care providers ensure that patients receive proper education for the prevention of asthma symptoms and provide supportive care when possible to help patients achieve a good quality of life.

The content published in Cureus is the result of clinical experience and/or research by independent individuals or organizations. Cureus is not responsible for the scientific accuracy or reliability of data or conclusions published herein. All content published within Cureus is intended only for educational, research and reference purposes. Additionally, articles published within Cureus should not be deemed a suitable substitute for the advice of a qualified health care professional. Do not disregard or avoid professional medical advice due to content published within Cureus.

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Human Ethics

Consent was obtained by all participants in this study. Institutional Review Board Committee JPMC, Karachi issued approval NO.F.2-81/2017-GENL/8822/JPMC. Institutional Review Board has approved

Animal Ethics

Animal subjects: All authors have confirmed that this study did not involve animal subjects or tissue.

References

- 1.The global burden of asthma: executive summary of the GINA Dissemination Committee Report. Masoli M, Fabian D, Holt S, Beasley R. Allergy. 2004;59:469–478. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2004.00526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The Cochrane Library and leukotriene receptor antagonists for children with asthma: an overview of reviews. Bjornson CL, Russell K, Plint A, Rowe BH. Evidence-Based Child Health A Cochrane Rev J. 2008;3:595–602. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Respiratory symptoms in adults are related to impaired quality of life, regardless of asthma and COPD: results from the European community respiratory health survey. Voll-Aanerud M, Eagan TM, Plana E, et al. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2010;8:107. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-8-107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clinical, economic, and humanistic burden of asthma in Canada: a systematic review. Ismaila AS, Sayani AP, Marin M, Su Z. BMC Pulm Med. 2013;13:70. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-13-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Improvement in asthma quality of life in patients enrolled in a prospective study to increase lifestyle physical activity. Mancuso CA, Choi TN, Westermann H, Wenderoth S, Wells MT, Charlson ME. J Asthma. 2013;50:103–107. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2012.743150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Asthma control assessed in the EGEA epidemiological survey and health-related quality of life. Siroux V, Boudier A, Bousquet J, et al. Respir Med. 2012;106:820–828. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2012.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Health-related quality of life and asthma among United States adolescents. Cui W, Zack MM, Zahran HS. J Pediatr. 2015;166:358–364. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Measurement properties of the EQ-5D-5L compared to the EQ-5D-3L across eight patient groups: a multi-country study. Janssen MF, Pickard AS, Golicki D, et al. Qual Life Res. 2013;22:1717–1727. doi: 10.1007/s11136-012-0322-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quality of life in asthmatic patients. Motaghi-Nejad M, Shakerinejad G, Cheraghi M, Tavakkol H, Saki A. Int J Bioassays. 2015;4:3757–3762. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Factors associated with health-related quality of life in adults with asthma. A cross-sectional study. Gonzalez-Barcala F-J, de la Fuente-Cid R, Tafalla M, Nuevo J, Caamaño-Isorna F. Multidiscip Respir Med. 2012;7:32. doi: 10.1186/2049-6958-7-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Relationship between guideline treatment and health-related quality of life in asthma. Pont LG, van der Molen T, Denig P, van der Werf GT, Haaijer-Ruskamp FM. Eur Respir J. 2004;23:718–722. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00065204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Validation of a standardized version of the asthma quality of life questionnaire. Juniper EF, Buist AS, Cox FM, Ferrie PJ, King DR. Chest. 1999;115:1265–1270. doi: 10.1378/chest.115.5.1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Asthma Education and Prevention Program - third expert panel on the diagnosis and management of asthma: expert panel report 3: Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma. [Aug;2020 ];https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK7232/ 2007). Accessed

- 14.Mahapatra P, Murthy K, Kasinath P, Yadagiri R. Social, Economic & Cultural Aspects of Asthma: an Exploratory Study in Andhra Pradesh, India. Institute of Health Systems, India 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Using humanistic health outcomes data in asthma. Juniper EF. Pharmacoeconomics. 2001;19:13–19. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200119002-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Evaluation of impairment of health related quality of life in asthma: development of a questionnaire for use in clinical trials. Juniper EF, Guyatt GH, Epstein RS, Ferrie PJ, Jaeschke R, Hiller TK. Thorax. 1992;47:76–83. doi: 10.1136/thx.47.2.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Umashankar: assessment of quality of life in bronchial asthma patients. Nalina N, Chandra M. Int J Med Public Heal. 2015;5:93–97. [Google Scholar]

- 18.The influence of demographic and socioeconomic factors on health-related quality of life in asthma. Apter AJ, Reisine ST, Affleck G, Barrows E, ZuWallack RL. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999;103:72–78. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(99)70528-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Relationship between patient and disease characteristics, and health-related quality of life in adults with asthma. Erickson S, Christian R, Kirking D, Halman L. Respir Med. 2002;96:450–460. doi: 10.1053/rmed.2001.1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Quality of life and economic features in elderly asthmatics. Plaza V, Serra-Batlles J, Ferrer M, Morejón E. Respiration. 2000;67:65–70. doi: 10.1159/000029465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Quality-of-life and asthma-severity in general population asthmatics: results of the ECRHS II study. Siroux V, Boudier A, Anto JM, et al. Allergy. 2008;63:547–554. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2008.01638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Asthma in older adults. Gibson PG, McDonald VM, Marks GB. Lancet. 2010;376:803–813. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61087-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Age-related changes in immune function: effect on airway inflammation. Busse PJ, Mathur SK. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126:690–699. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Asthma in the elderly. Bellia V, Scichilone N, Battaglia S. https://iris.unipa.it/handle/10447/43136 Eur Respir Mon. 2009;43:56–76. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Impact of health literacy on longitudinal asthma outcomes. Mancuso CA, Rincon M. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:813–817. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00528.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Occupational asthma and work-exacerbated asthma. Santos MS, Jung H, Peyrovi J, Lou W, Liss GM, Tarlo SM. Chest. 2007;131:1768–1775. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-2487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]