Abstract

Background and Purpose

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is an incurable, incapacitating disorder resulting from increased pulmonary vascular resistance, pulmonary arterial remodelling, and right ventricular failure. In preclinical models, the combination of a PDE5 inhibitor (PDE5i) with a neprilysin inhibitor augments natriuretic peptide bioactivity, promotes cGMP signalling, and reverses the structural and haemodynamic deficits that characterize PAH. Herein, we conducted a randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial to assess the efficacy and safety of repurposing the neprilysin inhibitor, racecadotril, in PAH.

Experimental Approach

Twenty‐one PAH patients stable on PDE5i therapy were recruited. Acute haemodynamic and biochemical changes following a single dose of racecadotril or matching placebo were determined; this was followed by a 14‐day safety and efficacy evaluation. The primary endpoint in both steps was the maximum change in circulating atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) concentration (Δmax), with secondary outcomes including pulmonary and systemic haemodynamics plus mechanistic biomarkers.

Key Results

Acute administration of racecadotril (100 mg) resulted in a 79% increase in the plasma ANP concentration and a 106% increase in plasma cGMP levels, with a concomitant 14% fall in pulmonary vascular resistance. Racecadotril (100 mg; t.i.d.) treatment for 14 days resulted in a 19% rise in plasma ANP concentration. Neither acute nor chronic administration of racecadotril resulted in a significant drop in mean arterial BP or any serious adverse effects.

Conclusions and Implications

This Phase IIa evaluation provides proof‐of‐principle evidence that neprilysin inhibitors may have therapeutic utility in PAH and warrants a larger scale prospective trial.

Abbreviations

- ANP

atrial natriuretic peptide

- BNP

brain natriuretic peptide

- CNP

C‐type natriuretic peptide

- ET‐1

endothelin‐1

- GC‐1

NO‐sensitive GC α1β1 isoform

- GC‐2

NO‐sensitive GC α2β1 isoform

- GC‐A

natriuretic peptide‐sensitive GC‐A

- IDMC

independent data monitoring committee

- IMP

investigational medicinal product

- LA

left atrium

- LVEF

left ventricular ejection fraction

- MABP

mean arterial BP

- mPAP

mean pulmonary artery pressure

- NEP

neprilysin/neutral endopeptidase

- NOx

[NO2 −] + [NO3 −]

- PAH

pulmonary arterial hypertension

- PCWP

pulmonary capillary wedge pressure

- PDE5i

PDE5 inhibitor

- PH

pulmonary hypertension

- PVR

pulmonary vascular resistance

- RHC

right heart catheterization

- RV

right ventricle

What is already known

Drugs that elevate cGMP (i.e., PDE5 inhibitors) have proven efficacy in pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH).

Neprilysin inhibitors augment natriuretic peptide‐driven cGMP signalling and are licensed for use in heart failure.

What this study adds

Combining PDE5 and neprilysin inhibitors produces additive beneficial haemodynamic effects in PAH patients.

What is the clinical significance

These data support a larger prospective trial evaluating the repurposing of neprilysin inhibitors for PAH.

1. INTRODUCTION

Pulmonary hypertension (PH) is a progressive, debilitating disorder with high associated morbidity and mortality. It is characterized by an increased pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) and a degenerative remodelling of the pulmonary arterial tree, leading to right ventricular (RV) failure and death. A cure remains elusive, and contemporary strategies to improve therapy have focused on developing drug combinations that synergize in the pulmonary circulation, improving haemodynamics and reversing structural remodelling (Ghofrani et al., 2002; Hoeper et al., 2004; Humbert et al., 2004).

Targeting cGMP is effective in treating PH, exemplified by the clinical use of PDE5 inhibitors (PDE5i; Galie et al., 2005) and soluble GC (NO‐sensitive GC‐1 and GC‐2; “sGC”) stimulators (Ghofrani et al., 2013). However, these approaches only slow disease progression rather than offering resolution. Preclinical studies exploring cGMP signalling in the pulmonary circulation have provided compelling evidence to support atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) and/or brain natriuretic peptide (BNP)‐driven cGMP production in optimizing cGMP‐based therapy founded on PDE inhibition, in terms of both efficacy and (pulmonary) selectivity. For example, the beneficial effects of PDE5i in experimental models of chronic hypoxia‐induced PH are blunted in animals lacking GC‐A (the cognate receptor for ANP and BNP; Zhao, Mason, Strange, Walker, & Wilkins, 2003); a similarly exacerbated phenotype in observed in GC‐A−/− animals with bleomycin‐triggered pulmonary fibrosis and secondary PH, with an associated loss of efficacy of PDE5i (Baliga et al., 2014). Furthermore, infusion of natriuretic peptides in the presence of the PDE5i sildenafil synergistically reduces pulmonary artery pressure in hypoxia‐induced PH (Preston, Hill, Gambardella, Warburton, & Klinger, 2004); a similar interaction has been reported between urodilatin (a renal‐specific ANP variant) and the PDE5i dipyridamole (Schermuly et al., 2001). Similarly, infusion of monoclonal antibodies neutralizing ANP stimulates the development of PH in response to hypoxia (Raffestin et al., 1992), whilst exogenously administered or adenovirus‐mediated natriuretic peptide supplementation protects against PH and the accompanying right ventricular hypertrophy (Jin, Yang, Chen, Jackson, & Oparil, 1988; Klinger et al., 1993; Louzier et al., 2001). Such findings suggest that the mechanism of pulmonary selectivity of PDE5i depends on the bioactivity of natriuretic peptides and, additionally, that in PH, release of natriuretic peptides represents a cytoprotective mechanism that slows disease progression.

One potential mechanism that might be utilized pharmacologically in PH to promote this protective role of natriuretic peptides is to inhibit the enzyme neprilysin (or neutral endopeptidase, NEP). NEP is a membrane bound zinc metallopeptidase responsible for the metabolism and inactivation of an array of vasodilator (e.g., natriuretic peptides, adrenomedullin, vasoactive intestinal peptide) and vasoconstrictor (e.g., angiotensin II, endothelin‐1 [ET‐1]) peptides (Erdos & Skidgel, 1989; Kenny & Stephenson, 1988). Indeed, preclinical evidence indicates that NEP−/− mice are less susceptible to hypoxia‐induced pulmonary oedema (Irwin, Patot, Tucker, & Bowen, 2005) and that inhibition of NEP attenuates hypoxia‐induced PH by potentiating the action of natriuretic peptides (Klinger et al., 1993; Thompson, Sheedy, & Morice, 1994; Winter, Zhao, Krausz, & Hughes, 1991). These observations fit with the up‐regulation of NEP in the pulmonary circulation during acute lung injury and heart failure (Abassi, Kotob, Golomb, Pieruzzi, & Keiser, 1995; Hashimoto, Amaya, Oh‐Hashi, Kiuchi, & Hashimoto, 2010).

We exploited this “natriuretic peptide‐centric” approach to evaluate the therapeutic potential of a PDE5i and NEPi combination in animal models of PH (Baliga et al., 2008; Baliga et al., 2014). Our data showed that this dual therapy is superior to either drug alone in hypoxia‐induced PH and PH secondary to pulmonary fibrosis. This held true for both haemodynamic (e.g., pulmonary artery pressure) and structural (e.g., right ventricular hypertrophy and pulmonary arterial remodelling) indices; importantly, however, combination therapy did not significantly affect systemic BP, confirming selective targeting of the pulmonary vasculature (Baliga et al., 2008; Baliga et al., 2014). Thus, by combining a PDE5i and a NEPi, it is possible to harness further the beneficial effects of natriuretic peptide‐cGMP signalling, thereby optimizing pulmonary efficacy and selectivity.

A clear advantage of evaluating this novel PDE5i/NEPi combination in PH patients is the availability of existing licensed medications; the PDE5i sildenafil and tadalafil are prescribed for the treatment of PAH, and the NEPi, racecadotril, is also licensed for use in secretory diarrhoea. In accord, this report describes a randomized, double‐blind, placebo controlled trial to assess the safety and efficacy of repurposing racecadotril in PAH patients stable on PDE5i therapy.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study design and participants

This study was a single‐centre, double‐blind, Phase IIa, randomized, placebo‐controlled trial conducted in two stages (with planned interim and final analyses), to determine whether administration of the NEPi, racecadotril, to patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH; WHO Group 1) on PDE5i therapy, increases plasma [ANP] and favourably alters pulmonary haemodynamics without affecting mean arterial BP (MABP). The trial was approved by a local independent research ethics committee (NRES Committee London—Westminster; ref: 13/LO/0387), the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (ref: 20363/0320/001‐0003), documented in approved registries (EudraCT#2012003921‐13), and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (1996) and the principles of the International Conference on Harmonization‐Good Clinical Practice guidelines. Trial management was undertaken by the UCL Comprehensive Clinical Trials Unit and an Independent Trial Steering Committee and Independent Data Monitoring Committee (IDMC) provided trial oversight. Eligible patients at the Royal Free London NHS Foundation Trust who gave written informed consent were included in the trial.

Step 1

After consenting, patients considered for Step 1 of the trial underwent right heart catheterization (as routine care). Patients who met the inclusion criteria were randomized to receive a single dose of racecadotril (100 mg; p.o.) or matching placebo (concurrently with their existing PDE5i therapy). The access sheath to the catheter was maintained in position so that pulmonary and systemic haemodynamic measurements could be recorded at 1.5 and 2 hr following administration of racecadotril or placebo, after which it was removed. Venous blood samples were also collected at baseline, 0, 1, 2, 3, and 6 hr, following administration of racecadotril or placebo for the assessment of biochemical endpoints.

Step 2

Patients were randomized to receive racecadotril (100 mg, t.i.d.; p.o.) or matching placebo for 14 days in addition to (and concomitantly with) their current PH‐directed therapy. Systemic BP measurements and venous blood samples were taken at baseline (Day 0) and Day 14. A telephone conversation at Day 7 was undertaken to assess the occurrence of any adverse events (AEs).

2.2. Endpoints

Step 1

The primary endpoint was the maximum change (Δmax) in plasma [ANP]. Secondary endpoints comprised a range of pulmonary and systemic haemodynamic indices: Δmax mean pulmonary artery pressure (mPAP), Δmax PVR, Δmax pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP), Δmax MABP, Δmax plasma [BNP], Δmax plasma [NT‐proBNP], Δmax plasma [C‐type natriuretic peptide (CNP)], Δmax plasma [ET‐1], Δmax plasma [cGMP], Δmax plasma [NOx].

Step 2

The primary co‐endpoints were safety (adverse effects; assessed for seriousness, severity and causality by on‐site clinicians and reported to the IDMC) and Δmax plasma [ANP]. Secondary endpoints comprised a range of systemic haemodynamic indices: Δmax MABP, Δmax plasma [BNP], Δmax plasma [NT‐proBNP], Δmax plasma [CNP], Δmax plasma [ET‐1], Δmax plasma [cGMP], Δmax plasma [NOx].

2.2.1. Study drug

The NEPi racecadotril (Hidrasec®, Tiorfan®; benzyl N‐[3‐(acetylthio)‐2‐benzylpropanoyl]glycinate) is approved in Europe and South America for the treatment of acute diarrhoea. Racecadotril reduces intestinal hyper‐secretion of water and electrolytes, without affecting basal secretion and has no effect in the normal intestine. When given orally, NEP inhibition is solely peripheral; racecadotril does not affect central NEP activity. It has a reassuring safety record (>1 million adult exposures), with rarely reported (<2%) side effects including drowsiness, nausea, dizziness, and headaches. In adults, single doses of 2 g (i.e., 20 times the therapeutic dose for the treatment of acute diarrhoea) have been administered in clinical trials for up to 3 months without causing any harmful effects (Lecomte, 2000). Racecadotril has a rapid onset of action, with maximal inhibition of NEP at 60 min following a single dose of 100 mg (p.o.) in humans (Lecomte, 2000); NEP activity returns to baseline within 8 hr (the biological half‐life is approximately 3.5 hr). This PK profile translates to significantly increased plasma ANP levels within 2 hr, returning to baseline at approximately 6 hr (Kahn et al., 1990). Racecadotril does not induce or inhibit CYP450 enzymes, and the principal route of elimination is renal.

2.2.2. Inclusion criteria

WHO Group I pulmonary arterial hypertension (i.e., idiopathic, familial, or associated with connective tissue diseases)

18–80 years old

Technically satisfactory RHC (Step 1 only)

Taking sildenafil (20–100 mg; t.i.d.) or tadalafil (20–40 mg; o.d.) for at least 1 month

No changes to any PH‐specific therapies for 1 month

Six‐minute walk distance of >150 m

Not pregnant (women only)

Able to provide consent for the trial

2.2.3. Exclusion criteria

Known sensitivity to racecadotril or its excipients

Clinical diagnosis of liver cirrhosis or alanine transaminase/aspartate transaminase >2x upper limit of normal

Kidney disease with an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of <50 ml·min−1

History of angioedema

Systolic BP < 85 mmHg

Known history of drug or alcohol abuse within 6 months of enrolment

Participation in a clinical study involving another investigational drug

Women who are breastfeeding

Taking an ACE inhibitor

Any clinical condition for which the investigator would consider the patient unsuitable for the trial

2.2.4. Biochemical assays

All clinical biochemistry (including NT‐proBNP) and haematology analyses were conducted at the Royal Free London NHS Foundation Trust. Plasma natriuretic peptide, ET‐1, and cGMP concentrations were determined using commercially available enzyme immunoassay (Phoenix Pharmaceuticals Inc., Karlsruhe, Germany). Plasma samples were also analysed for nitrite (NO2 −) and nitrate (NO3 −), as an index of endogenous NO production (total NOx), using chemiluminescence as described previously (Ignarro, Fukuto, Griscavage, Rogers, & Byrns, 1993).

2.2.5. Sample size

Based on previous clinical studies (Berglund, Nyquist, Beermann, Jensen‐Urstad, & Theodorsson, 1994; Bruins et al., 2004; Tan, Kloppenborg, & Benraad, 1989), the between patient SD of the percentage change from baseline in ANP (i.e., primary outcome measure) was estimated as 12.2. Sample size calculations used a two‐sided 5% significance level, 80% power, and a 2:1 active : placebo randomization ratio.

Step 1

Within each block of six patients (in Step 1a and Step 1b), a sample size of four patients on active therapy and two patients on placebo enabled detection of a difference between the two groups in the mean percentage change in ANP of 50%. Combination of the placebo groups from the two blocks of six patients, with adjustment for multiple comparisons using the Bonferroni procedure, permitted the detection of a difference between placebo and racecadotril in the mean percentage change in ANP of 21%. By way of precedent, in chronic heart failure, 30 mg sinorphan (L‐isomer of acetorphan; equivalent to 60 mg of racecadotril) increases plasma ANP by 100% (Kahn et al., 1990), and in cirrhotic patients, 100 mg sinorphan elicits a 180% increase in plasma ANP (Dussaule et al., 1991). In PH patients, a 21% increase was therefore considered conservative.

Step 2

Using a 2:1 active : placebo ratio, a sample size of eight patients on active therapy and four patients on placebo enabled detection of a difference between the two groups in the mean percentage change in ANP of 21%. A 2:1 ratio also provide twice as much information on the safety profile of the drug combination, with minimal effect on the difference that would be able to be distinguished.

2.2.6. Early patient safety and biological activity adaptive design

Step 1 of the study was designed with an adaptive early recruitment phase to allow early termination in case of lack of biological activity of racecadotril or harms. Step 1 was further broken down into two steps:

Step1a

After the first six patients received a single dose of 100 mg of racecadotril or placebo, the trial stopped recruitment, and key clinical parameters and safety data were reviewed in an unblinded fashion by the IDMC who were asked to consider whether a dose of racecadotril has been identified that

on average increases ANP by a minimum of 20%,

on average decreases PVR by a minimum of 10%, and

on average decreases SBP by no more than 10%

based on whether the 95% confidence interval (CI) for the relevant (racecadotril–control) difference excluded any of these prespecified clinically important changes. The recommendation was to continue recruiting patients without increasing the investigational medicinal product (IMP) dose due to the apparent pharmacodynamic effect.

Step1b

An additional six patients were recruited into the study and administered a single dose of 100 mg of racecadotril or placebo followed by the IDMC data review in a similar fashion to Step1a. The IDMC recommended proceeding to Step 2 of the trial, recruiting patients at the 100 mg dose of racecadotril.

2.2.7. Randomization and blinding

Patients were randomly assigned in a 2:1 ratio to received 100 mg of racecadotril or matching placebo using random permuted blocks. The allocation sequence was computer‐generated by the trial statistician, and concealment of allocation was ensured by the use of an identical inert placebo, with security in place to ensure allocation of unblinded codes could not be accessed by anyone in the trial team other than the statistician and the pharmacist (for manufacturing and labelling purposes).

2.2.8. Data and statistical analyses

All statistical tests were two‐sided with a significance level of 5%. All continuous efficacy outcomes were log transformed for the statistical analyses. Results were back transformed and are presented as geometric means and 95% CI or ratios and 95% CI. All statistical analysis was based on a prespecified Statistical Analysis Plan which was reviewed by the Trial Steering Committee and IDMC. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata/IC (Ver.14.2 RRID:SCR_012763; StataCorp, College Station, TX, 77845 USA). The data and statistical analysis comply with the recommendations of the British Journal of Pharmacology on experimental design and analysis in pharmacology.

2.2.9. Nomenclature of targets and ligands

Key protein targets and ligands in this article are hyperlinked to corresponding entries in http://www.guidetopharmacology.org, the common portal for data from the IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY (Harding et al., 2018), and are permanently archived in the Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2017/18 (Alexander, Christopoulos et al., 2017; Alexander, Fabbro et al., 2017a,b).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Step 1

3.1.1. Overview

Seventeen patients were screened at the Royal Free London NHS Foundation Trust, between February 2014 and December 2015, for entry to Step 1 of the trial. A total of 15 participants were randomized. Of these, two participants did not receive racecadotril (one due to technical difficulties with the RHC and the other was ruled unfit to receive IMP), and one participant was withdrawn and replaced (for logistical reasons). This is depicted in the CONSORT flow chart (Figure 1). The analysis population for Step 1 comprises nine patients allocated to racecadotril and four allocated to placebo.

Figure 1.

CONSORT flow chart for Step 1 (left panel) and Step 2 (right panel)

3.1.2. Characteristics of the study population

All baseline and procedural characteristics were similar between groups, except the plasma [CNP] which by chance was higher in the placebo group (Table 1). The mean age of the trial participants was 57 years, with 77% (10/13) female. All participants had significantly raised mPAP (45.54 ± 2.8 mmHg) and PVR (514.5 ± 39.9 dynes·s−1·cm−5) consistent with a PAH diagnosis.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of study population—Step 1

| Characteristic | Placebo (n = 4) | Racecadotril (n = 9) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age (years) | Mean (SD) | 58 (10) | 57 (14) |

| Sex | (M/F) | 0/4 | 3/6 |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Caucasian | Number (%) | 4 (100) | 8 (89) |

| Black African | Number (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (11) |

| Weight (kg) | Mean (SD) | 72.5 (24.3) | 76.8 (8.3) |

| Height (m) | Mean (SD) | 1.65 (0.06) | 1.70 (0.14) |

| Body mass index (kg·m−2) | Mean (SD) | 28.3 (7.7) | 26.9 (4.7) |

| Clinical biochemistry | |||

| ALT (U·L−1) | GM [95% CI] | 16 [12, 21] | 19 [15, 24] |

| AST (U·L−1) | GM [95% CI] | 18 [12, 27] | 23 [19, 28] |

| eGFR (ml·min−1) | GM [95% CI] | 63 [50, 79] | 72 [62, 82] |

| Hb (g·L−1) | GM [95% CI] | 137 [120, 156] | 129 [113, 146] |

| WBC (×109·L−1) | GM [95% CI] | 8 [4, 15] | 7 [6, 8] |

| RBC (×1012·L−1) | GM [95% CI] | 4.62 [4.20, 5.08] | 4.33 [3.87, 4.83] |

| PT (s) | GM [95% CI] | 11 [10, 13] | 16 [12, 23] |

| APTT (s) | GM [95% CI] | 30 [27, 33] | 36 [33, 39] |

| Disease characteristics | |||

| Time since diagnosis (months) | Mean (SD) | 11.3 (0.6 to 198.9) | 24.3 (12.1 to 48.8) |

| PH group | |||

| 1.1 Idiopathic | Number (%) | 1 (25) | 3 (33) |

| 1.4.1 CTD | Number (%) | 2 (75) | 6 (67) |

| 1.4.4 CHD | Number (%) | 1 (25) | 0 (0) |

| WHO functional class | |||

| I | Number (%) | 0 (0) | 2 (22) |

| II | Number (%) | 2 (50) | 1 (11) |

| III | Number (%) | 2 (50) | 6 (67) |

| 6MWD (m) | GM [95% CI] | 364 [198, 669] | 402 [335, 483] |

| Borg dyspnoea score | Mean (SD) | 11.8 (3.2) | 10.8 (3.9) |

| Concurrent PH therapy | |||

| Sildenafil | Number (%) | 4 (100) | 10 (89) |

| Tadalafil | Number (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (11) |

| ERA | Number (%) | 1 (25) | 8 (89) |

| Prostacyclin analogue | Number (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (11) |

| Diuretic | Number (%) | 1 (25) | 6 (67) |

| Primary endpoint | |||

| Plasma [ANP] (nM) | GM [95% CI] | 0.11 [0.06, 0.20] | 0.08 [0.05, 0.12] |

| Systemic haemodynamics | |||

| MABP (mmHg) | GM [95% CI] | 95 [79, 115] | 89 [81, 98] |

| SBP (mmHg) | GM [95% CI] | 133 [111, 159] | 122 [112, 133] |

| DBP (mmHg) | GM [95% CI] | 76 [60, 95] | 72 [64, 81] |

| SaO2 (%) | GM [95% CI] | 94 [89, 100] | 95 [93, 98] |

| Pulmonary haemodynamics | |||

| mPAP (mmHg) | GM [95% CI] | 48 [37, 62] | 43 [36, 51] |

| PVR (dynes·s−1·cm−5) | GM [95% CI] | 549 [327, 921] | 470 [368, 602] |

| PCWP (mmHg) | GM [95% CI] | 10 [6, 19] | 11 [10, 13] |

| TAPSE (mm) | GM [95% CI] | 22.6 [19.5, 26.1] | 19.0 [15.7, 22.9] |

| TRV (m·s−1) | GM [95% CI] | 4.1 [2.4, 6.8] | 3.2 [2.8, 3.8] |

| Cardiac indices | |||

| HR (bpm) | GM [95% CI] | 85 [63, 116] | 72 [64, 80] |

| CO (L·min−1) | GM [95% CI] | 5.4 [2.9, 10.3] | 5.4 [4.3, 6.7] |

| SV (ml) | GM [95% CI] | 64 [42, 97] | 75 [59, 95] |

| LVEF (%) | GM [95% CI] | 57 [53, 61] | 56 [55, 58] |

| LA area (cm2) | GM [95% CI] | 15.6 [11.7, 20.7] | 18.2 [15.2, 21.9] |

| RA area (cm2) | GM [95% CI] | 19.1 [13.3, 27.5] | 19.7 [15.0, 25.8] |

| RV diameter (cm) | GM [95% CI] | 3.9 [3.0, 5.2] | 3.7 [3.3, 4.2] |

| Pericardial effusion | Number (%) | 0 (0) | 2 (22) |

| Biomarkers | |||

| Plasma [BNP] (nM) | GM [95% CI] | 0.007 [0.00002, 2.01] | 0.004 [0.0004, 0.04] |

| Plasma [NT‐proBNP] (nM) | GM [95% CI] | 38 [10, 137] | 40 [18, 89] |

| Plasma [CNP] (pM) | GM [95% CI] | 706 [0, 1642008] | 38 [1, 2214] |

| Plasma [cGMP] (nM) | GM [95% CI] | 41 [14, 119] | 17 [8, 36] |

| Plasma [ET‐1] (nM) | GM [95% CI] | 1.96 [1.14, 3.36] | 1.86 [1.62, 2.14] |

| Plasma [NOx] (nM) | GM [95% CI] | 36,274 [14389, 91445] | 31,642 [15836, 63223] |

Note: ALT, alanine transaminase; APTT, activated partial thromboplastin time; AST, aspartate transaminase; BNP, brain natriuretic peptide; CTD, connective tissue disease; CHD, congenital heart disease; CNP, C‐type natriuretic peptide; eGFR, estimated GFR; ERA, endothelin receptor antagonist; ET‐1, endothelin‐1; GM, geometric mean; HR, heart rate; CO, cardiac output; LA, left atrium; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; mPAP, mean pulmonary artery pressure; NT‐proBNP, N‐terminal‐proBNP; NOx, [NO2 −] + [NO3 −]; PT, prothrombin time; PVR, pulmonary vascular resistance; PCWP, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure; RA, right atrium; RBC, red blood cell count; RV, right ventricle; SV, stroke volume; TAPSE, tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion; TRV, tricuspid regurgitant velocity; WBC, white blood cell count; 6MWD, 6min walk distance.

3.1.3. Primary endpoint

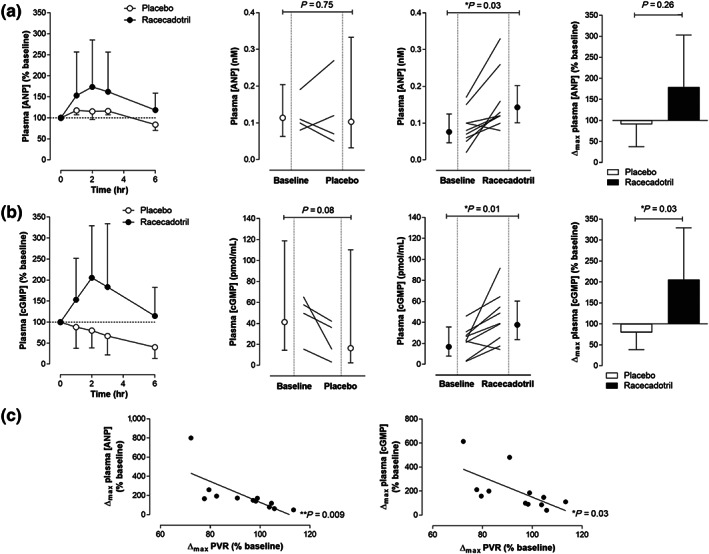

Administration of racecadotril caused an increase in plasma [ANP] that peaked at 2 hr and returned to baseline by 6 hr (Figure 2). This pharmacokinetic profile mirrored that observed in previous studies evaluating racecadotril in left heart failure patients and closely aligns with the biological half‐life of the drug (Dussaule et al., 1991; Kahn et al., 1990; Lecomte, 2000). Racecadotril caused a significant increase (79%) in the maximum plasma [ANP] whereas a small decrease was observed in the placebo arm (albeit two patients receiving placebo exhibited an increase in plasma [ANP] (Figure 2). These data suggest that, akin to previous studies in heart failure, NEP inhibition causes a significant rise in circulating ANP levels.

Figure 2.

Time course (left panel), absolute change (middle panels), and maximum percentage change from baseline (right panel) in plasma atrial natriuretic peptide concentration ([ANP]); (a) or cGMP concentration; (b) in PAH patients receiving racecadotril (100 mg) or matching placebo. Data are represented as geometric mean ± 95% CI. n = 4 (placebo) and n = 9 (racecadotril). Data were analysed by paired t test for absolute intrapatient change (i.e., before and after treatment) and by unpaired t test for intergroup comparison (i.e., placebo vs. racecadotril) of Δmax (%). Correlation between maximum percentage change in PVR and maximum percentage change in plasma [ANP] or plasma [cGMP] (c). n = 4 (placebo) and n = 8 (racecadotril). Data were analysed by Pearson correlation. In all cases, P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant

3.1.4. Secondary endpoints

The increases in plasma [ANP] in patients receiving racecadotril was mirrored temporally and in magnitude by plasma cGMP concentrations (Figure 2). Thus, cGMP levels peaked at the 2 hr timepoint and were 106% higher compared to baseline, returning to pre‐IMP concentrations after 6 hr (Figure 2). Indeed, plasma [cGMP] was significantly increased in the racecadotril arm per se and in comparison to placebo (Figure 2). These data imply that the temporal elevation in circulating ANP concentrations results in a commensurate increase in cGMP formation (via activation of GC‐A).

The parallel rise in plasma levels of ANP and cGMP in response to racecadotril exerted a positive influence on pulmonary haemodynamics without having an overt effect on the systemic circulation. In this setting, PVR and PCWP were reduced in patients receiving racecadotril compared to placebo (although one of four patients in the placebo arm also exhibited a reduction in PVR and PCWP), and the peak response on pulmonary haemodynamics (2 hr) matched the maximum rise in both plasma [ANP] and [cGMP] (Figure 3); indeed, there was a significant correlation between increases in plasma [ANP] and plasma [cGMP] with reductions in PVR (Figure 2), tendering some elementary indication of causality. A similar trend was observed with mPAP (Figure 4) in the absence of any overt change in cardiac output or heart rate (Table 2). However, there was no significant effect of racecadotril on MABP between the active and control arms (Figure 4), with MABP falling modestly over time in both groups.

Figure 3.

Time course (left panel), absolute change (middle panels), and maximum percentage change from baseline (right panel) in pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR; (a) or pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP); (b) in PAH patients receiving racecadotril (100 mg) or matching placebo. Data are presented as geometric mean ± 95% CI. n = 4 (placebo) and n = 8 (racecadotril). Data were analysed by paired t test for absolute intrapatient change (i.e., before and after treatment) and by unpaired t test for intergroup comparison (i.e., placebo vs. racecadotril) of Δmax (%). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant

Figure 4.

Time course (left panel), absolute change (middle panels), and maximum percentage change from baseline (right panel) in mean pulmonary artery pressure (mPAP; (a) or mean arterial BP (MABP); (b) in PAH patients receiving racecadotril (100 mg) or matching placebo. Data are presented as geometric mean ± 95% CI. n = 4 (placebo) and n = 9 (racecadotril). Data were analysed by paired t test for absolute intrapatient change (i.e., before and after treatment) and by unpaired t test for intergroup comparison (i.e., placebo vs. racecadotril) of Δmax (%). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant

Table 2.

Additional haemodynamic and biomarker parameters—Step 1

| Characteristic | Placebo (n = 4) | Racecadotril (n = 9) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Systemic haemodynamics | |||

| ΔSBP (mmHg) | −6 [−54, 94] | −15 [−25, −3] | 0.18 |

| ΔDBP (mmHg) | −16 [−60, 74] | −24 [−37, −9] | 0.44 |

| ΔHR (bpm) | −22 [−36, −6] | −4 [−24, 21] | 0.64 |

| ΔCO (L·min−1) | 0.2 [−0.3, 0.6] | 0.3 [−0.1, 0.6] | 0.56 |

| ΔSV (ml) | 29 [6, 58] | 33 [20, 46] | 0.56 |

| ΔSaO2 (%) | −1 [−12, 12] | −1 [−6, 3] | 0.99 |

| Biomarkers | |||

| ΔPlasma [BNP] (nM) | 155 [−84, 4367] | 32 [−79, 714] | 0.37 |

| ΔPlasma [CNP] (pM) | −1 [−96, 2466] | −44 [−87, 154] | 0.36 |

| ΔPlasma [NOx] (nM) | −28 [−49, 0] | −47 [−77, 22] | 0.56 |

Note: Data are presented as change in geometric mean [95% CI].

Importantly, plasma [ET‐1] was not changed following exposure to racecadotril (Figure 5). This is a key safety readout since NEP metabolizes a number of vasoactive peptides, including ET‐1 (Llorens‐Cortes et al., 1992), which is known to be a key driver of pathology in PAH and the target of existing therapy (Luscher & Barton, 2000; Stewart, Levy, Cernacek, & Langleben, 1991; Williamson et al., 2000). Additional mechanistic biomarkers were also unaltered following racecadotril administration in comparison to placebo. This included plasma concentrations of other members of the natriuretic peptide family including BNP (Table 2), NT‐proBNP (Figure 5), and CNP (Table 2), and plasma NOx (as an index of NO bioactivity; Table 2). The lack of effect of NEP inhibition on these biomarkers intimates that the rise in plasma [cGMP] and accompanying reductions in PVR and PCWP are solely mediated by increased ANP bioactivity.

Figure 5.

Time course (left panel), absolute change (middle panels), and maximum percentage change from baseline (right panel) in plasma endothelin‐1 concentration ([ET‐1]; (a) or N‐terminal‐pro‐brain natriuretic peptide concentration [NT‐proBNP]; (b) in PAH patients receiving racecadotril (100 mg) or matching placebo. Data are presented as geometric mean ± 95% CI. n = 4 (placebo) and n = 9 (racecadotril). Data were analysed by paired t test for absolute intrapatient change (i.e., before and after treatment) and by unpaired t test for intergroup comparison (i.e., placebo vs. racecadotril) of Δmax (%). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant

3.1.5. Safety

No serious adverse events (SAEs) or serious adverse reactions were reported in Step 1 of the trial. Only one patient allocated to racecadotril reported (two) minor AEs that were potentially drug‐related: vomiting and epistaxis. Full details of the AEs reported by severity grade, seriousness criteria, causality, and trial step can be found in Table 5.

Table 5.

Adverse events by severity, seriousness and causality for each trial step

| Trial step | Patient ID | Treatment group | Adverse event | Severity grade(0–5) | Seriousness | Outcome | Treatment related? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | COM202 | Racecadotril | Vomiting | 2 | Not serious | Resolved | Possibly |

| 1 | COM202 | Racecadotril | Epistaxis | 2 | Not serious | Resolved | Possibly |

| 2 | COM121 | Racecadotril | Headache | 1 | Not serious | Resolved | Possibly |

| 2 | COM121 | Racecadotril | Diarrhoea | 1 | Not serious | Resolved | No |

| 2 | COM121 | Racecadotril | Dizziness | 1 | Not serious | Resolved | Possibly |

| 2 | COM121 | Racecadotril | Cough | 1 | Not serious | Resolved | Possibly |

| 2 | COM121 | Racecadotril | Vomiting | 1 | Not serious | Resolved | Possibly |

| 2 | COM123 | Racecadotril | Headache | 1 | Not serious | Resolved | Possibly |

| 2 | COM123 | Racecadotril | Epistaxis | 1 | Not serious | Resolved | Possibly |

| 2 | COM123 | Racecadotril | Stomach pain | 1 | Not serious | Resolved | Possibly |

| 2 | COM123 | Racecadotril | Upper respiratory tract infection | 2 | Not serious | Resolved | Possibly |

| 2 | COM125 | Racecadotril | Constipation | 1 | Not serious | Resolved | Possibly |

| 2 | COM126 | Placebo | Diarrhoea | 2 | Not serious | Resolved | No |

| 2 | COM126 | Placebo | Dry skin | 1 | Not serious | Resolved | No |

| 2 | COM127 | Racecadotril | Hiccups | 1 | Not serious | Resolved | No |

| 2 | COM127 | Racecadotril | Body cramps | 1 | Not serious | Resolved | No |

3.2. Step 2

3.2.1. Overview

A total of 10 patients were screened at the Royal Free London NHS Foundation Trust, between May 2016 and October 2016, for possible entry to Step 2 of the trial. Of these, two were excluded before they were randomized; one patient was unable to attend further visits, and the second individual declined to participate after initially consenting. Due to logistical difficulties in recruiting patients to this phase of the study, only eight participants were randomized; this fell short of the necessary 12 individuals, randomized 1:2 to the placebo and racecadotril arms, to be powered to detect a 21% difference in plasma [ANP], the primary endpoint. This is depicted in the CONSORT flow chart (Figure 1). The analysis population for Step 2 comprises five patients allocated to racecadotril and three allocated to placebo.

3.2.2. Characteristics of the study population and treatment compliance

All baseline and procedural characteristics were similar between groups, except by chance the plasma [ANP], plasma [CNP], plasma [cGMP], and plasma [NOx] were higher in the placebo group (Table 3). The mean age of the trial participants was 68 years, with 88% (7/8) female.

Table 3.

Baseline characteristics of study population—Step 2

| Characteristics | Placebo (n = 3) | Racecadotril (n = 5) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age (years) | Mean (SD) | 67 (3) | 69 (7) |

| Sex | (M/F) | 1/2 | 0/5 |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Caucasian | Number (%) | 3 (100) | 4 (80) |

| Black African | Number (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (20) |

| Weight (kg) | Mean (SD) | 77.0 (20.3) | 77.0 (20.3) |

| Height (m) | Mean (SD) | 1.67 (0.07) | 1.63 (0.07) |

| Body mass index (kg·m−2) | Mean (SD) | 27.5 (6.1) | 29.3 (7.8) |

| Clinical biochemistry | |||

| ALT (U·L−1) | GM [95% CI] | 19 [13, 26] | 24 [11, 53] |

| AST (U·L−1) | GM [95% CI] | 21 [14, 31] | 23 [11, 46] |

| eGFR (ml·min−1) | Median (IQR) | 69 [71, 90] | 73 [73, 90] |

| Hb (g·L−1) | GM [95% CI] | 120 [76, 188] | 127 [114, 142] |

| WBC (×109·L−1) | GM [95% CI] | 6 [4, 11] | 5 [4, 6] |

| RBC (×1012·L−1) | GM [95% CI] | 4.26 [3.02, 5.99] | 4.51 [3.76, 5.42] |

| PT (s) | GM [95% CI] | 11 [11, 13] | 17 [9, 31] |

| APTT (s) | GM [95% CI] | 36 [25, 52] | 37 [31, 44] |

| Disease characteristics | |||

| Time since diagnosis (months) | Mean (SD) | 35.0 (27.8) | 13.4 (11.2) |

| PH group | |||

| 1.1 Idiopathic | Number (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (20) |

| 1.4.1 CTD | Number (%) | 3 (100) | 4 (80) |

| 1.4.4 CHD | Number (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| WHO Functional Class | |||

| I | Number (%) | 1 (33) | 0 (0) |

| II | Number (%) | 0 (0) | 2 (40) |

| III | Number (%) | 2 (67) | 3 (60) |

| 6MWD (m) | GM [95% CI] | 443 [201, 975] | 315 [191, 522] |

| Borg dyspnoea score | Mean (SD) | 10.7 (3.2) | 13.0 (3.7) |

| Concurrent PH therapy | |||

| Sildenafil | Number (%) | 3 (100) | 5 (100) |

| Tadalafil | Number (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| ERA | Number (%) | 0 (0) | 2 (40) |

| Prostacyclin analogue | Number (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Diuretic | Number (%) | 3 (100) | 3 (60) |

| Primary endpoint | |||

| Plasma [ANP] (nM) | GM [95% CI] | 0.20 [0.17, 0.24] | 0.16 [0.08, 0.34] |

| Systemic haemodynamics | |||

| MABP (mmHg) | GM [95% CI] | 73 [34, 156] | 70 [55, 90] |

| SBP (mmHg) | GM [95% CI] | 115 [78, 170] | 121 [105, 141] |

| DBP (mmHg) | GM [95% CI] | 71 [46, 111] | 68 [54, 86] |

| SaO2 (%) | GM [95% CI] | 97 [91, 103] | 95 [93, 97] |

| Pulmonary haemodynamics | |||

| TAPSE (mm) | GM [95% CI] | 23.7 [14.0, 40.0] | 17.6 [10.6, 29.0] |

| TRV (m·s−1) | GM [95% CI] | 2.61 [0.69, 9.93] | 3.62 [2.84, 4.61] |

| Cardiac indices | |||

| HR (bpm) | GM [95% CI] | 87 [48, 158] | 88 [72, 107] |

| CO (L·min−1) | GM [95% CI] | 5.4 [2.9, 10.3] | 5.4 [4.3, 6.7] |

| SV (ml) | GM [95% CI] | 64 [42, 97] | 75 [59, 95] |

| LVEF (%) | GM [95% CI] | 58 [58, 58] | 57 [54, 60] |

| LA area (cm2) | GM [95% CI] | 22.6 [19.1, 26.8] | 19.1 [11.7, 31.3] |

| RA area (cm2) | GM [95% CI] | 24.3 [19.3, 30.5] | 18.0 [13.4, 24.1] |

| RV diameter (cm) | GM [95% CI] | 3.7 [2.8, 5.0] | 3.8 [3.2, 4.5] |

| Pericardial effusion | Number (%) | 1 (33) | 1 (20) |

Note: ALT, alanine transaminase; APTT, activated partial thromboplastin time; AST, aspartate transaminase; BNP, brain natriuretic peptide; CHD, congenital heart disease; CNP, C‐type natriuretic peptide; CO, cardiac output; CTD, connective tissue disease; eGFR, estimated GFR; ERA, endothelin receptor antagonist; ET‐1, endothelin‐1, GM: geometric mean; HR, heart rate; IQR, interquartile range; LA, left atrium; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; mPAP, mean pulmonary artery pressure; NOx, [NO2 −] + [NO3 −]; NT‐proBNP, N‐terminal‐proBNP; PCWP, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure; PT, prothrombin time; PVR, pulmonary vascular resistance; RA, right atrium; RBC, red blood cell count; RV, right ventricle; SV, stroke volume; TAPSE, tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion; TRV, tricuspid regurgitant velocity; WBC, white blood cell count; 6MWD, 6‐min walk distance.

All patients were treatment compliant; that is, they took at least 30 of the 42 tablets during the repeat dosage schedule of 12–14 days. The median number of capsules taken in the placebo and racecadotril groups was 39 (IQR 39 to 40) and 40 (IQR 37 to 41), respectively.

3.2.3. Primary endpoint

Administration of racecadotril for 14 days caused ~25% increase in plasma [ANP], whereas those individuals receiving placebo saw a drop in their plasma [ANP] of ~10%; however, an intrapatient analysis did not reveal a significant increase (P = 0.19), despite an apparent trend (Figure 6). The clear increase in circulating ANP levels brought about by NEP inhibition in Step 1 was therefore not maintained to the same extent over a period of 2 weeks in response to t.i.d. administration of the same dose of racecadotril.

Figure 6.

Absolute change (left and middle panels) and maximum percentage change from baseline (right panel) in mean arterial BP (MABP); (a) or plasma atrial natriuretic peptide concentration [ANP]; (b) in PAH patients receiving racecadotril (100 mg; t.i.d.; 14 days) or matching placebo. Data are presented as geometric mean ± 95% CI. n = 3 (placebo) and n = 5 (racecadotril). Data were analysed by paired t test for absolute intrapatient change (i.e., before and after treatment) and by unpaired t test for intergroup comparison (i.e., placebo vs. racecadotril) of Δmax (%). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant

3.2.4. Secondary endpoints

Despite the inability to detect an increase in plasma [ANP] following chronic dosing, arguably, the most important goal of Step 2 was to assess the safety of daily use of racecadotril in patients with PH. Administration of racecadotril over 14 days did not alter MABP, substantiating the acute lack of effect in Step 1 (Figure 6); moreover, chronic administration of racecadotril did not cause any SAEs (see below).

Additional mechanistic biomarkers (e.g., cGMP, BNP, NT‐proBNP, CNP, and NOx) were unaltered following racecadotril administration in comparison to placebo (Table 4). Again, NEP inhibition did not alter plasma [ET‐1] levels (Table 4), which is critical to any potential therapeutic application of the drug in PAH.

Table 4.

Additional haemodynamic and biomarker parameters—Step 2

| Characteristic | Placebo (n = 3) | Racecadotril (n = 5) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Haemodynamics | |||

| ΔSBP (mmHg) | −10 [−42, 41] | −4 [−24, 19] | 0.36 |

| ΔDBP (mmHg) | −10 [−56, 83] | −4 [−19, 13] | 0.70 |

| ΔHR (bpm) | −7 [−38, 40] | 24 [5, 46] | 0.05 |

| ΔSaO2 (%) | 0 [−7, 6] | 0 [−3, 3] | 0.97 |

| Biomarkers | |||

| ΔPlasma [BNP] (nM) | 548 [−100, 1195000] | −66 [−99, 1336] | 0.20 |

| ΔPlasma [NT‐proBNP] (nM) | 16 [−75, 440] | −12 [−20, −3] | 0.40 |

| ΔPlasma [CNP] (pM) | −16 [−44, 26] | −2 [−16, 16] | 0.16 |

| ΔPlasma [cGMP] (nM) | −51 [−92, 193] | 34 [−64, 395] | 0.66 |

| ΔPlasma [ET‐1] (nM) | −21 [−84, 278] | −20 [−37, 1] | 0.96 |

| ΔPlasma [NOx] (nM) | −23 [−79, 186] | 1 [−48, 94] | 0.96 |

Note: Data are presented as change in geometric mean (95% CI).

3.2.5. Safety

No SAEs or serious adverse reactions were reported in Step 2 of the trial. Table 5 shows there were a total of 14 minor AEs reported by patients allocated to racecadotril, and thought to be potentially drug‐related, included vomiting, epistaxis, dizziness, and headache. The difference in the proportion of patients reporting at least one AE between the two arms (i.e., 0.33 in the placebo group vs. 0.80 in the racecadotril) was not statistically significant (P = 0.464; Fisher's exact test).

4. DISCUSSION

The introduction of PDE5i and sGC stimulators, both of which promote cGMP‐dependent signalling, has significantly improved the treatment of PAH (Galie et al., 2005; Ghofrani et al., 2013). However, a significant cohort of PAH patients do not respond well to these interventions, or experience a diminution of efficacy over time (Galie et al., 2009). This is particularly true of PDE5i since blockade of cGMP breakdown is inexorably dependent on endogenous NO and/or natriuretic peptide signalling to drive efficacy (i.e., endogenous input to the system), which often wane with disease progression. The development of sGC stimulators has negated this decline in efficacy to a certain extent, circumventing the reliance on endogenous NO signalling; this is demonstrated, arguably, by maintained improvement in 6‐min walk distance, WHO functional class, and NT‐proBNP levels 2 years after initiation of treatment (Rubin et al., 2015). However, pharmacological activation of sGC appears not to provide any pulmonary specificity, eliciting a generic vasodilator influence which can result in dose‐limiting systemic hypotension or drug discontinuation for related adverse effects (Galie, Muller, Scalise, & Grunig, 2015; Ghofrani et al., 2016; Rubin et al., 2015). Thus, identification of drug combinations which trigger cGMP signalling preferentially in the pulmonary vasculature and RV have potential to optimally harness the therapeutic potential of cGMP above and beyond existing therapy and further improve the treatment of PH.

Targeting natriuretic peptide signalling may address this aspiration. Evidence from preclinical and clinical studies suggests that the therapeutic efficacy of PDE5i in PH is primarily dependent on promoting natriuretic peptide bioactivity rather than NO (Baliga et al., 2014; Jin et al., 1988; Klinger et al., 1993; Louzier et al., 2001; Zhao et al., 2003). This concept provides a clear rationale for evaluating combination therapy with PDE5i and NEPi (which slows natriuretic peptide inactivation) in PH patients. Indeed, a precedent for such a therapeutic strategy exists in left‐sided heart failure; the dual NEPi (sacubitril)‐angiotensin receptor blocker (valsartan), LCZ696, has been demonstrated to reduce mortality and hospitalizations by approximately 20% in a large scale RCT (McMurray et al., 2014).

Herein, acute administration of racecadotril to PH patients stable on PDE5i therapy caused a marked augmentation of circulating ANP concentrations that peaked at 2 hr and returned to baseline within 6 hr. This pharmacodynamic profile closely matches the plasma half‐life of the drug (6–8 hr). The circulating levels of cGMP followed an almost identical time course and magnitude. These commensurate increases provide good evidence of the anticipated efficacy of NEPi in the PAH patients population, increasing ANP/GC‐A/cGMP signalling for therapeutic gain. Accordingly, acute administration of racecadotril produced a commensurate effect on pulmonary haemodynamics (i.e., PVR and PCWP), but not the systemic vasculature, as predicted by preclinical models (a phenomenon also observed following administration of NEPi to healthy volunteers; Ando, Rahman, Butler, Senn, & Floras, 1995). The time course of reduction in pulmonary haemodynamic variables also matched the biological half‐life of the drug and the temporal profile of the enhancement of ANP and cGMP. Yet there was little or no effect on MABP across the entire time course of the acute study, which was corroborated by observations from the 14‐day evaluation in which systemic haemodynamics remained unchanged between the placebo and active arms. These findings give credence to thesis that combination of PDE5i and NEPi produces a pulmonary‐specific effect on haemodynamics.

Importantly, administration of racecadotril was not associated with an overt increase in circulating ET‐1 concentrations. This is an important finding since NEP is thought to underpin a principle route of ET‐1 breakdown and inactivation (Llorens‐Cortes et al., 1992). ET‐1 is well‐established to contribute to disease progression in PH and pharmacological blockade of its cognate receptor(s), particularly the ETA subtype, is effective in treating the disease (Luscher & Barton, 2000; Stewart et al., 1991; Williamson et al., 2000). Thus, at least in this relatively short‐term evaluation, the efficacy of NEP inhibition does not appear to be limited by detrimental augmentation of ET‐1 bioactivity. Interestingly, the plasma concentrations of BNP and NT‐proBNP did not show a similar significant change in patients receiving racecadotril, which likely reflects the reduced susceptibility of BNP to breakdown by NEP (compared to ANP; Watanabe, Nakajima, Shimamori, & Fujimoto, 1997). CNP levels were also unaltered in the face of NEP blockade; this is perhaps surprising since this is the preferred natriuretic peptide substrate for NEP (Watanabe et al., 1997). However, CNP acts primarily in a paracrine fashion, and its systemic concentrations might not reflect tissue levels (Potter, 2011). Finally, and as expected, the circulating NOx concentrations were not altered by NEP inhibition, confirming that the increases in cGMP observed in patients receiving racecadotril were exclusively due to up‐regulation of ANP/GC‐A signalling and not through activation of NO‐driven pathways.

Longer term (14 day) treatment with racecadotril did not appear to give rise to equivalent increases in circulating ANP levels as achieved by acute administration. This reduced efficacy is likely underpinned by two explanations. First, the study was powered to detect an intrapatient difference in plasma [ANP] of 21%, so since recruitment fell short of the desired total in Step 2, a larger prospective study would be required to corroborate a beneficial effect of this magnitude. Second, the rapid pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profile of racecadotril with respect to plasma [ANP] demonstrated in Step 1 implies that time of administration is critical to the detection of elevated levels. Whilst patients were requested to take their final dose of racecadotril on the morning of their 14 day assessment (concurrently with their PDE5i therapy), the time between consumption and hospital evaluation varied greatly and did not coincide with the peak plasma [ANP] identified in Step 1. However, previous clinical studies in heart failure have demonstrated that NEP inhibition (using ecadotril, omapatrilat, or LCZ696) maintains elevated [ANP] and/or [cGMP] chronically, for up to 8 months (Campese et al., 2001; Cleland & Swedberg, 1998; McMurray et al., 2014; Packer et al., 2015), tendering reassurance that NEPi are likely to exert a similar longer term pharmacological action in the PH patient cohort. Additionally, this trial did not investigate the dose–response relationship for racecadotril in PAH patients, rather the study utilized the licensed dose of this NEPi for safety and repurposing intentions. Thus, it is possible that the maximum pharmacodynamic effect has not been reached, and higher concentrations of racecadotril would exert greater beneficial activity. Further optimization in this context is warranted. Regardless, it should be noted that the fall in PVR produced by NEP inhibition herein was on top of that provided by existing PDE5i therapy, suggesting current cGMP‐centric drugs can be further enhanced.

With respect to safety, racecadotril has a reassuring profile with more than 1 million patient exposures without overt evidence of serious side effects. Whilst there were numerically more AEs reported by patients taking racecadotril versus placebo, there was not a statistical difference between the two groups; moreover, the AEs reported by those taking racecadotril were mild and largely expected based on the vascular (vasodilator) and intestinal (diminution of Cl− and water secretion) effects of NEP inhibition, including headache, dizziness, and constipation. These observations give reassurance that chronic use of NEPi in the PAH population will be well tolerated and safe, although a longer term study will be needed to ratify this.

In sum, this study provides proof‐of‐concept clinical evidence of the therapeutic potential of repurposing NEP inhibition in PAH. The beneficial effects of NEPi are dependent on endogenous natriuretic peptide bioactivity, synergize with PDE5i, and exhibit a pulmonary‐specific action. The dual mechanism of action inherent to a PDE5i/NEPi combination is unique in terms of existing PH therapy (which target one step in the cGMP signalling cascade) and therefore holds a theoretical advantage in treating the disease. These findings warrant a larger scale, prospective study with this combination therapy in PH patients to determine if efficacy, selectivity, and safety are maintained over a longer period with respect to pulmonary haemodynamics, RV function, exercise capacity, and quality of life.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

B.S. has been a consultant/advisory board member for GSK & Actelion. J.C. has been a consultant/advisory board member for Actelion, GSK, Bayer, United Therapeutics, Endotronic, and Pfizer. A.H. has been a consultant/advisory board member for Bayer AG, Serodus ASA, and Palatin Technologies Inc.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors made a significant contribution to the experimental design, data acquisition, and analysis/interpretation, were involved with drafting or critically appraising the manuscript, gave approval for submission, and are familiar with all aspects of the study.

DECLARATION OF TRANSPARENCY AND SCIENTIFIC RIGOUR

This Declaration acknowledges that this paper adheres to the principles for transparent reporting and scientific rigour of preclinical research as stated in the BJP guidelines for Design & Analysis, and as recommended by funding agencies, publishers and other organisations engaged with supporting research.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge the contribution made by the members of the Trial Steering Committee and Independent Data Monitoring Committee—Prof. Martin Wilkins, Prof. Mark Griffiths, and Dr. Timothy Collier.

This work was supported by a British Heart Foundation Project Grant (PG/11/88/28992) and the National Institutes for Health Research, Comprehensive Biomedical Research Centre award to UCL.

Hobbs AJ, Moyes AJ, Baliga RS, et al. Neprilysin inhibition for pulmonary arterial hypertension: A randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, proof‐of‐concept trial. Br J Pharmacol. 2019;176:1251–1267. 10.1111/bph.14621

REFERENCES

- Abassi, Z. A. , Kotob, S. , Golomb, E. , Pieruzzi, F. , & Keiser, H. R. (1995). Pulmonary and renal neutral endopeptidase EC 3.4.24.11 in rats with experimental heart failure. Hypertension, 25, 1178–1184. 10.1161/01.HYP.25.6.1178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, S. P. H. , Christopoulos, A. , Davenport, A. P. , Kelly, E. , Marrion, N. V. , Peters, J. A. , … CGTP Collaborators (2017). The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2017/18: G protein‐coupled receptors. British Journal of Pharmacology, 174(S1), S17–S129. 10.1111/bph.13878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, S. P. H. , Fabbro, D. , Kelly, E. , Marrion, N. V. , Peters, J. A. , Faccenda, E. , … CGTP Collaborators (2017a). The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2017/18: Catalytic receptors. British Journal of Pharmacology, 174(S1), S225–S271. 10.1111/bph.13876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, S. P. H. , Fabbro, D. , Kelly, E. , Marrion, N. V. , Peters, J. A. , Faccenda, E. , … CGTP Collaborators (2017b). The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2017/18: Enzymes. British Journal of Pharmacology, 174(Suppl 1), S272–S359. 10.1111/bph.13877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ando, S. , Rahman, M. A. , Butler, G. C. , Senn, B. L. , & Floras, J. S. (1995). Comparison of candoxatril and atrial natriuretic factor in healthy men. Effects on hemodynamics, sympathetic activity, heart rate variability, and endothelin. Hypertension, 26, 1160–1166. 10.1161/01.HYP.26.6.1160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baliga, R. S. , Scotton, C. J. , Trinder, S. L. , Chambers, R. C. , MacAllister, R. J. , & Hobbs, A. J. (2014). Intrinsic defence capacity and therapeutic potential of natriuretic peptides in pulmonary hypertension associated with lung fibrosis. British Journal of Pharmacology, 171, 3463–3475. 10.1111/bph.12694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baliga, R. S. , Zhao, L. , Madhani, M. , Lopez‐Torondel, B. , Visintin, C. , Selwood, D. , … Hobbs, A. J. (2008). Synergy between natriuretic peptides and phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors ameliorates pulmonary arterial hypertension. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 178, 861–869. 10.1164/rccm.200801-121OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berglund, H. , Nyquist, O. , Beermann, B. , Jensen‐Urstad, M. , & Theodorsson, E. (1994). Influence of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibition on relation of atrial natriuretic peptide concentration to atrial pressure in heart failure. British Heart Journal, 72, 521–527. 10.1136/hrt.72.6.521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruins, S. , Fokkema, M. R. , Römer, J. W. , Dejongste, M. J. , van der Dijs, F. P. , van den Ouweland, J. M. , & Muskiet, F. A. (2004). High intraindividual variation of B‐type natriuretic peptide (BNP) and amino‐terminal proBNP in patients with stable chronic heart failure. Clinical Chemistry, 50, 2052–2058. 10.1373/clinchem.2004.038752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campese, V. M. , Lasseter, K. C. , Ferrario, C. M. , Smith, W. B. , Ruddy, M. C. , Grim, C. E. , … Liao, W. C. (2001). Omapatrilat versus lisinopril: Efficacy and neurohormonal profile in salt‐sensitive hypertensive patients. Hypertension, 38, 1342–1348. 10.1161/hy1201.096569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleland, J. G. , & Swedberg, K. (1998). Lack of efficacy of neutral endopeptidase inhibitor ecadotril in heart failure. The International Ecadotril Multi‐Centre Dose‐Ranging Study Investigators. Lancet, 351, 1657–1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dussaule, J. C. , Grange, J. D. , Wolf, J. P. , Lecomte, J. M. , Gros, C. , Schwartz, J. C. , … Ardaillou, R. (1991). Effect of sinorphan, an enkephalinase inhibitor, on plasma atrial natriuretic factor and sodium urinary excretion in cirrhotic patients with ascites. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, 72, 653–659. 10.1210/jcem-72-3-653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erdos, E. G. , & Skidgel, R. A. (1989). Neutral endopeptidase 24.11 (enkephalinase) and related regulators of peptide hormones. The FASEB Journal, 3, 145–151. 10.1096/fasebj.3.2.2521610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galiè, N. , Ghofrani, H. A. , Torbicki, A. , Barst, R. J. , Rubin, L. J. , Badesch, D. , … Simonneau, G. (2005). Sildenafil citrate therapy for pulmonary arterial hypertension. The New England Journal of Medicine, 353, 2148–2157. 10.1056/NEJMoa050010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galie, N. , Manes, A. , Negro, L. , Palazzini, M. , Bacchi‐Reggiani, M. L. , & Branzi, A. (2009). A meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials in pulmonary arterial hypertension. European Heart Journal, 30, 394–403. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galie, N. , Muller, K. , Scalise, A. V. , & Grunig, E. (2015). PATENT PLUS: A blinded, randomised and extension study of riociguat plus sildenafil in pulmonary arterial hypertension. European Respiratory Journal, 45, 1314–1322. 10.1183/09031936.00105914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghofrani, H. A. , Galiè, N. , Grimminger, F. , Grünig, E. , Humbert, M. , Jing, Z.‐C. , … Rubin, L. J. (2013). Riociguat for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. The New England Journal of Medicine, 369, 330–340. 10.1056/NEJMoa1209655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghofrani, H. A. , Grimminger, F. , Grünig, E. , Huang, Y. G. , Jansa, P. , Jing, Z. C. , … Humbert, M. (2016). Predictors of long‐term outcomes in patients treated with riociguat for pulmonary arterial hypertension: Data from the PATENT‐2 open‐label, randomised, long‐term extension trial. Lancet Resp Med, 4, 361–371. 10.1016/S2213-2600(16)30019-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghofrani, H. A. , Wiedemann, R. , Rose, F. , Olschewski, H. , Schermuly, R. T. , Weissmann, N. , … Grimminger, F. (2002). Combination therapy with oral sildenafil and inhaled iloprost for severe pulmonary hypertension. Annals of Internal Medicine, 136, 515–522. 10.7326/0003-4819-136-7-200204020-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding, S. D. , Sharman, J. L. , Faccenda, E. , Southan, C. , Pawson, A. J. , Ireland, S. , … NC‐IUPHAR (2018). The IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY in 2018: Updates and expansion to encompass the new guide to immunopharmacology. Nucleic Acids Research, 46, D1091–D1106. 10.1093/nar/gkx1121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto, S. , Amaya, F. , Oh‐Hashi, K. , Kiuchi, K. , & Hashimoto, S. (2010). Expression of neutral endopeptidase activity during clinical and experimental acute lung injury. Respiratory Research, 11, 164 10.1186/1465-9921-11-164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoeper, M. M. , Faulenbach, C. , Golpon, H. , Winkler, J. , Welte, T. , & Niedermeyer, J. (2004). Combination therapy with bosentan and sildenafil in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. The European Respiratory Journal, 24, 1007–1010. 10.1183/09031936.04.00051104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humbert, M. , Barst, R. J. , Robbins, I. M. , Channick, R. N. , Galiè, N. , Boonstra, A. , … Simonneau, G. (2004). Combination of bosentan with epoprostenol in pulmonary arterial hypertension: BREATHE‐2. The European Respiratory Journal, 24, 353–359. 10.1183/09031936.04.00028404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ignarro, L. J. , Fukuto, J. M. , Griscavage, J. M. , Rogers, N. E. , & Byrns, R. E. (1993). Oxidation of nitric oxide in aqueous solution to nitrite but not nitrate: Comparison with enzymatically formed nitric oxide from L‐arginine. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 90, 8103–8107. 10.1073/pnas.90.17.8103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin, D. C. , Patot, M. T. , Tucker, A. , & Bowen, R. (2005). Neutral endopeptidase null mice are less susceptible to high altitude‐induced pulmonary vascular leak. High Altitude Medicine & Biology, 6, 311–319. 10.1089/ham.2005.6.311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin, H. K. , Yang, R. H. , Chen, Y. F. , Jackson, R. M. , & Oparil, S. (1988). Chronic infusion of atrial natriuretic peptide prevents pulmonary hypertension in hypoxia‐adapted rats. Transactions of the Association of American Physicians, 101, 185–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn, J. C. , Patey, M. , Dubois‐Rande, J. L. , Merlet, P. , Castaigne, A. , Lim‐Alexandre, C. , … Schwartz, J. C. (1990). Effect of sinorphan on plasma atrial natriuretic factor in congestive heart failure. Lancet, 335, 118–119. 10.1016/0140-6736(90)90595-V [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny, A. J. , & Stephenson, S. L. (1988). Role of endopeptidase‐24.11 in the inactivation of atrial natriuretic peptide. FEBS Letters, 232, 1–8. 10.1016/0014-5793(88)80375-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klinger, J. R. , Petit, R. D. , Curtin, L. A. , Warburton, R. R. , Wrenn, D. S. , Steinhelper, M. E. , … Hill, N. S. (1993). Cardiopulmonary responses to chronic hypoxia in transgenic mice that overexpress ANP. Journal of Applied Physiology, 75, 198–205. 10.1152/jappl.1993.75.1.198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klinger, J. R. , Petit, R. D. , Warburton, R. R. , Wrenn, D. S. , Arnal, F. , & Hill, N. S. (1993). Neutral endopeptidase inhibition attenuates development of hypoxic pulmonary hypertension in rats. Journal of Applied Physiology, 75, 1615–1623. 10.1152/jappl.1993.75.4.1615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecomte, J. M. (2000). An overview of clinical studies with racecadotril in adults. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents, 14, 81–87. 10.1016/S0924-8579(99)00152-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llorens‐Cortes, C. , Huang, H. , Vicart, P. , Gasc, J. M. , Paulin, D. , & Corvol, P. (1992). Identification and characterization of neutral endopeptidase in endothelial cells from venous or arterial origins. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 267, 14012–14018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louzier, V. , Eddahibi, S. , Raffestin, B. , Déprez, I. , Adam, M. , Levame, M. , … Adnot, S. (2001). Adenovirus‐mediated atrial natriuretic protein expression in the lung protects rats from hypoxia‐induced pulmonary hypertension. Human Gene Therapy, 12, 503–513. 10.1089/104303401300042401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luscher, T. F. , & Barton, M. (2000). Endothelins and endothelin receptor antagonists: Therapeutic considerations for a novel class of cardiovascular drugs. Circulation, 102, 2434–2440. 10.1161/01.CIR.102.19.2434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMurray, J. J. , Packer, M. , Desai, A. S. , Gong, J. , Lefkowitz, M. P. , Rizkala, A. R. , … PARADIGM‐HF Investigators and Committees (2014). Angiotensin‐neprilysin inhibition versus enalapril in heart failure. The New England Journal of Medicine, 371, 993–1004. 10.1056/NEJMoa1409077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Packer, M. , McMurray, J. J. , Desai, A. S. , Gong, J. , Lefkowitz, M. P. , Rizkala, A. R. , … PARADIGM‐HF Investigators and Coordinators . (2015). Angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibition compared with enalapril on the risk of clinical progression in surviving patients with heart failure. Circulation, 131, 54–61. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.013748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter, L. R. (2011). Natriuretic peptide metabolism, clearance and degradation. The FEBS Journal, 278, 1808–1817. 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08082.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston, I. R. , Hill, N. S. , Gambardella, L. S. , Warburton, R. R. , & Klinger, J. R. (2004). Synergistic effects of ANP and sildenafil on cGMP levels and amelioration of acute hypoxic pulmonary hypertension. Experimental Biology and Medicine (Maywood, N.J.), 229, 920–925. 10.1177/153537020422900908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raffestin, B. , Levame, M. , Eddahibi, S. , Viossat, I. , Braquet, P. , Chabrier, P. E. , … Adnot, S. (1992). Pulmonary vasodilatory action of endogenous atrial natriuretic factor in rats with hypoxic pulmonary hypertension. Effects of monoclonal atrial natriuretic factor antibody. Circulation Research, 70, 184–192. 10.1161/01.RES.70.1.184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, L. J. , Galiè, N. , Grimminger, F. , Grünig, E. , Humbert, M. , Jing, Z. C. , … Ghofrani, H. A. (2015). Riociguat for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension: A long‐term extension study (PATENT‐2). The European Respiratory Journal, 45, 1303–1313. 10.1183/09031936.00090614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schermuly, R. T. , Weissmann, N. , Enke, B. , Ghofrani, H. A. , Forssmann, W. G. , Grimminger, F. , … Walmrath, D. (2001). Urodilatin, a natriuretic peptide stimulating particulate guanylate cyclase, and the phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitor dipyridamole attenuate experimental pulmonary hypertension: Synergism upon coapplication. American Journal of Respiratory Cell and Molecular Biology, 25, 219–225. 10.1165/ajrcmb.25.2.4256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, D. J. , Levy, R. D. , Cernacek, P. , & Langleben, D. (1991). Increased plasma endothelin‐1 in pulmonary hypertension: Marker or mediator of disease? Annals of Internal Medicine, 114, 464–469. 10.7326/0003-4819-114-6-464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan, A. C. , Kloppenborg, P. W. , & Benraad, T. J. (1989). Influence of age, posture and intra‐individual variation on plasma levels of atrial natriuretic peptide. Annals of Clinical Biochemistry, 26(Pt 6), 481–486. 10.1177/000456328902600604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, J. S. , Sheedy, W. , & Morice, A. H. (1994). Neutral endopeptidase (NEP) inhibition in rats with established pulmonary hypertension secondary to chronic hypoxia. British Journal of Pharmacology, 113, 1121–1126. 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1994.tb17112.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe, Y. , Nakajima, K. , Shimamori, Y. , & Fujimoto, Y. (1997). Comparison of the hydrolysis of the three types of natriuretic peptides by human kidney neutral endopeptidase 24.11. Biochemical and Molecular Medicine, 61, 47–51. 10.1006/bmme.1997.2584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, D. J. , Wallman, L. L. , Jones, R. , Keogh, A. M. , Scroope, F. , Penny, R. , … Macdonald, P. S. (2000). Hemodynamic effects of bosentan, an endothelin receptor antagonist, in patients with pulmonary hypertension. Circulation, 102, 411–418. 10.1161/01.CIR.102.4.411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter, R. J. , Zhao, L. , Krausz, T. , & Hughes, J. M. (1991). Neutral endopeptidase 24.11 inhibition reduces pulmonary vascular remodeling in rats exposed to chronic hypoxia. The American Review of Respiratory Disease, 144, 1342–1346. 10.1164/ajrccm/144.6.1342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, L. , Mason, N. A. , Strange, J. W. , Walker, H. , & Wilkins, M. R. (2003). Beneficial effects of phosphodiesterase 5 inhibition in pulmonary hypertension are influenced by natriuretic peptide activity. Circulation, 107, 234–237. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000050653.10758.6B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]