The first example of adamantane derivatives containing monoterpene moieties that showed inhibitory activity against several orthopoxviruses.

The first example of adamantane derivatives containing monoterpene moieties that showed inhibitory activity against several orthopoxviruses.

Abstract

Currently, the spectrum of agents against orthopoxviruses, in particular smallpox, is very narrow. Despite the fact that smallpox is well controlled, there is, for many reasons, a real threat of epidemics associated with this or a similar virus. In order to search for new low molecular weight orthopoxvirus inhibitors, a series of amides combining adamantane and monoterpene moieties were synthesized using 1- and 2-adamantanecarboxylic acids as well as myrtenic, citronellic and camphorsulfonic acids as acid components. The produced compounds exhibited high activity against the vaccinia virus (an enveloped virus belonging to the poxvirus family), which was combined with low cytotoxicity. Some compounds had a selectivity index higher than that of the reference drug cidofovir; the highest SI = 1123 was exhibited by 1-adamantanecarboxylic acid amide containing the (–)-10-amino-2-pinene moiety. The produced compounds demonstrated inhibitory activity against other orthopoxviruses: cowpox virus (SI = 30–406) and ectromelia virus (mousepox virus, SI = 39–707).

Introduction

In 1980, the World Health Organization (WHO) Assembly declared eradication of black (or natural) smallpox, caused by the agent referred to as the variola virus (VARV), which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus, on the planet. Since that time, vaccination against smallpox has been discontinued. Smallpox was the first disease in human history to be controlled by means of mass vaccination. Now, about 50% of the world's population is estimated to have no smallpox immunity. However, an Independent Advisory Group on Public Health Implications of Synthetic Biology Technology Related to Smallpox report to the WHO Director-General noted the need to continue developing new low molecular weight agents against the VARV.1 This conclusion is related to several reasons. First, due to climate change, the risk of smallpox spread from permafrost soils containing human smallpox remains. Second, the development and accessibility of biotechnologies pose a threat of reproduction of the VARV or a similar virus for terrorist purposes.2 Also, there is a risk of illegal SV storage and deliberate use of natural or recombinant VARV strains against the population. Another argument in favor of the development of new anti-orthopoxvirus agents is the potential danger to humans of other orthopoxviruses circulating in animal populations, such as monkeypox viruses and cowpox viruses, which evolve, spread, and periodically cause disease outbreaks in humans. For example, the latest monkeypox outbreak in humans occurred in Africa in 2016;3 it is worth noting that mortality from this disease amounts to 17%.4,5

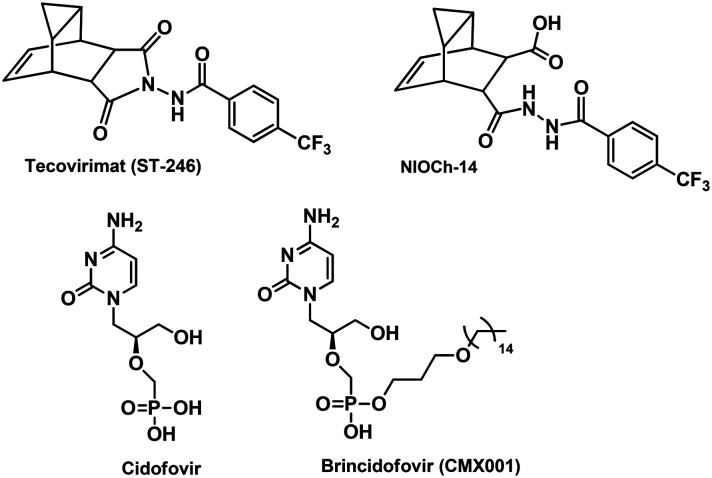

The only drug available for the treatment of smallpox and monkeypox is tecovirimat (TPOXX®), created on the basis of chemical compound ST-246 developed by SIGA Technologies Inc. (USA) (Fig. 1), was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use in the United States in 2018.6 The mechanism action of tecovirimat (TPOXX®, ST-246) is different from that of cidofovir (CDV) that inhibits viral DNA replication. The target of chemical compound ST-246 is a highly conserved virus-encoded protein, p37, present in all orthopoxviruses.7 An agent NIOCH-14, an analogue of ST-246, was developed at the Novosibirsk Institute of Organic Chemistry in cooperation with the VECTOR State Research Center of Virology and Biotechnology. This compound has been effective against orthopoxviruses in in vivo and in vitro experiments.8 The mechanism of action of NIOCH-14 is the same as that of ST-246 because NIOCH-14 is its prodrug and metabolized into ST-246 in mammals. Another anti-smallpox drug, brincidofovir (CMX001), which is undergoing clinical trials,9 is a lipophilic nucleotide analogue of cidofovir (Fig. 1). Cidofovir is an antiviral drug used for treating cytomegalovirus retinitis; in this case, cidofovir exhibits activity in lethal orthopoxvirus infection models in mice and monkeys.10 Cidofovir was shown to have low oral bioavailability and shown to be toxic to the kidneys; in addition, this drug was not effective when used after manifestation of smallpox lesions in VARV-infected monkeys. In the case of brincidofovir in small rodent models, it does not provide an adequate level of protection against lethal ectromelia infection in mice.11 Nevertheless, potential development of orthopoxvirus resistance to brincidofovir and tecovirimat necessitates further research for creating new biologically active compounds with mechanisms of action differing from those of drugs that are at the advanced stages of development, as it was concluded by the Advisory Group of Independent Experts to Review the Smallpox Programme in comments12 to the WHO report “Scientific review of variola virus research, 1999–2010”.10

Fig. 1. Chemical structure of the inhibitors of orthopoxvirus replication.

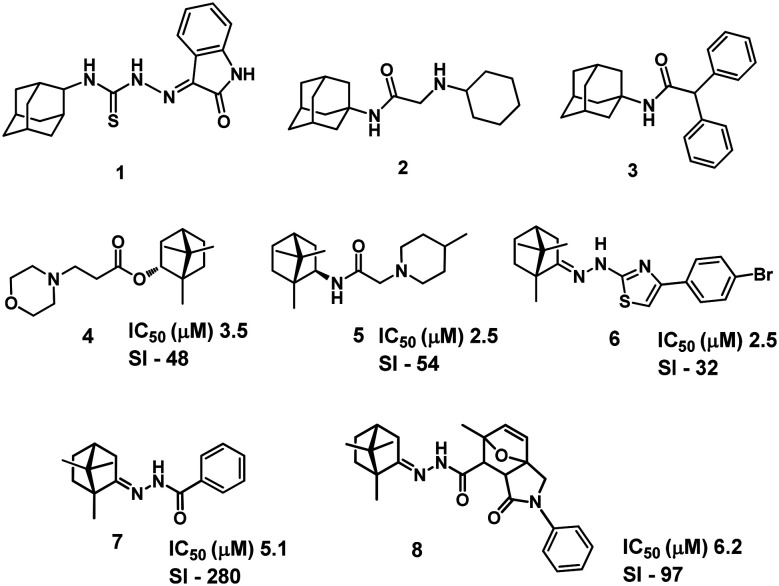

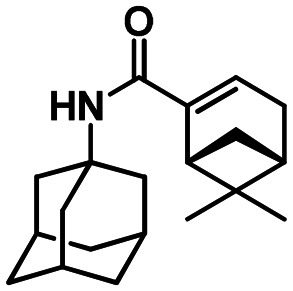

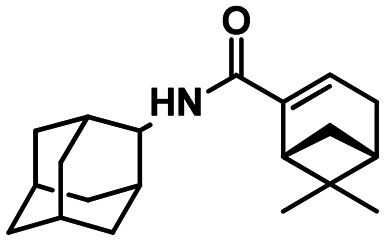

Some adamantane derivatives are known to exhibit antiviral activity, mainly against the influenza virus.13 However, a vaccinia virus inhibitor, 1H-indole-2,3-dion-3-(N-2-adamantyl thiosemicarbazone) 1, was found among adamantane derivatives (Fig. 2); exposure of the cell culture to the inhibitor at a concentration of 2 μg ml–1 for 3 h reduced vaccinia virus reproduction by 42%.14 Some substituted aminoacetyl-adamantylamines also have pronounced inhibitory activity against the vaccinia virus (e.g., compound 2, Fig. 2).15 A study16 demonstrated that N-1-adamantyl-2,2-diphenylacetamide 3 (Fig. 2) at a concentration of 2 μg ml–1 reduced reproduction of the vaccinia virus in cell culture by 72 to 100%. However, these studies lack the data on toxicity of the compounds, which prevents assessment of the selectivity index and, accordingly, the practical potential of these compounds. In addition, activity of the presented compounds towards other orthopoxviruses has not been studied.

Fig. 2. Chemical structure of inhibitors of orthopoxvirus replication containing adamantane 1–3 and 1,7,7-trimethylbicyclo[2.2.1]heptane 4–8 scaffolds.

Natural compounds, in particular natural bicyclic monoterpenoids containing the bicyclo[2.2.1]heptane moiety, have been used as starting molecules for the development of antiviral drugs.17 For example, earlier we discovered highly effective influenza virus inhibitors based on camphor,18 borneol,19 myrtenol20 and isopulegol,21 and showed high anti-filovirus activity of compounds containing the 1,7,7-trimethylbicyclo[2.2.1]heptane scaffold.22,23 Expanding the spectrum of antiviral activity of the synthesized agents, we have recently started studying their properties against vaccinia viruses. Thus, we demonstrated that ester 4 and amide 5 exhibited pronounced activity against the vaccinia virus.24 Camphor-derived compound 6 (Fig. 2) containing a thiazole ring showed activity in a lower micromolar range (IC50: 2.4–3.7 μM; IC50 is the virus inhibitory concentration providing 50% cell survival in virus-infected monolayers) with moderate cytotoxicity in the Vero cell line (CC50: 64–94 μM; CC50 is the toxicity concentration causing 50% cell death in uninfected monolayers).25 Camphor N-acylhydrazones 7 and 8 showed an even higher selectivity index (Fig. 2); their IC50 and CC50 were 5.1 μM and 1430 μM for 7 and 6.2 μM and 490 μM for 8, respectively.26 Agents 4–8 described by us were an order of magnitude more active than the reference drug cidofovir (IC50: 40 μM). Previously, we found that connection of a monoterpene moiety with an aminoadamantane molecule increased its antiviral properties against a rimantadine-resistant strain of the A(H1N1)pdm09 influenza virus.27 At the same time, the anti-smallpox activity of compounds combining adamantane and monoterpene moieties was not previously studied.

The purpose of this study was to synthesize amides combining adamantane and monoterpene moieties to investigate their inhibitory activity against orthopoxviruses.

Results and discussion

Chemistry

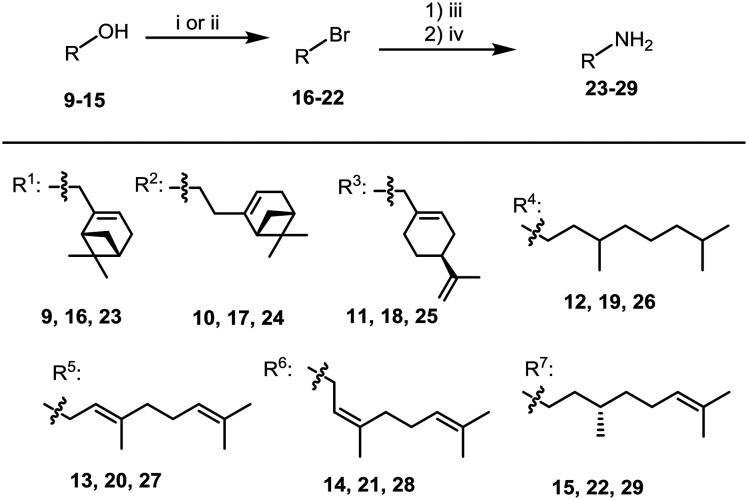

At the first stage, several monoterpene amines were synthesized for producing target amides containing an adamantane moiety. For this purpose, bromo derivatives 16–21 were prepared from (–)-myrtenol 9, (–)-nopol 10, (–)-perillyl alcohol 11, 3,7-dimethyloctanol 12, geraniol 13, and nerol 14 by the reaction with PBr3 (Scheme 1). Almost all bromides were isolated from the reaction mixtures by column chromatography in yields of 30 to 95%. Bromides 20 and 21 were unstable on SiO2 and were used without purification. Bromide 22 was synthesized from (S)-citronellol 15 by treatment with N-bromosuccinimide in the presence of PPh3 according to the procedure in ref. 28 (Scheme 1). The yield of compound 22 after purification by column chromatography on silica gel amounted to 79%. Amines 23–29 were produced from bromides 16–22 according to the Gabriel procedure (Scheme 1). Amines 23, 24 and 26–28 were previously described in ref. 29–35.

Scheme 1. Reagents and conditions: (i) was used for 16–21: PBr3 (0.4 eq.), Et2O; (ii) was used for 22: NBS, PPh3, CH2Cl2; (iii) potassium phthalimide (1.1 eq.), DMF, 60 °C, 6 h; (iv) ethylenediamine (2 eq.), MeOH, reflux, 4 h.

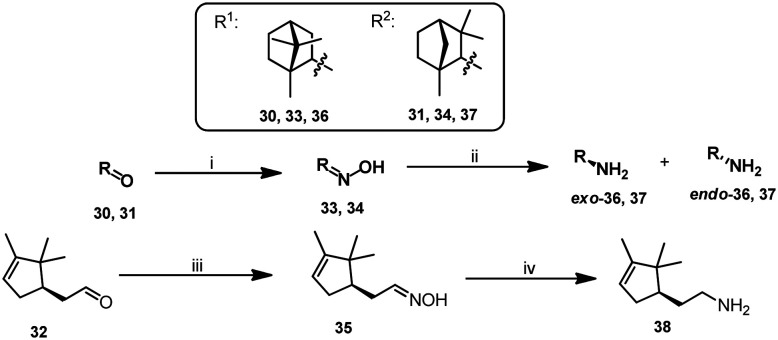

By using (+)-camphor 30, (–)-fenchone 31, and (+)-campholenic aldehyde 32, we prepared appropriate oximes 33–35 (Scheme 2), which were then reduced to amines using the NaBH4–NiCl2 system for compounds 36 and 37, and LiAlH4 was used as a reducing agent for oxime 35. In this case, amines 36 and 37 were formed as mixtures of exo- and endo-isomers; predominant diastereomers were isolated from the reaction mixtures by column chromatography.

Scheme 2. Reagents and conditions: (i) NH2OH·HCl, NaOAc, MeOH/H2O, reflux; (ii) NaBH4, NiCl2, –40 °C; (iii) NH2OH·HCl, K2CO3, EtOH, 3 h; (iv) LiAlH4, THF, reflux, 3 h.

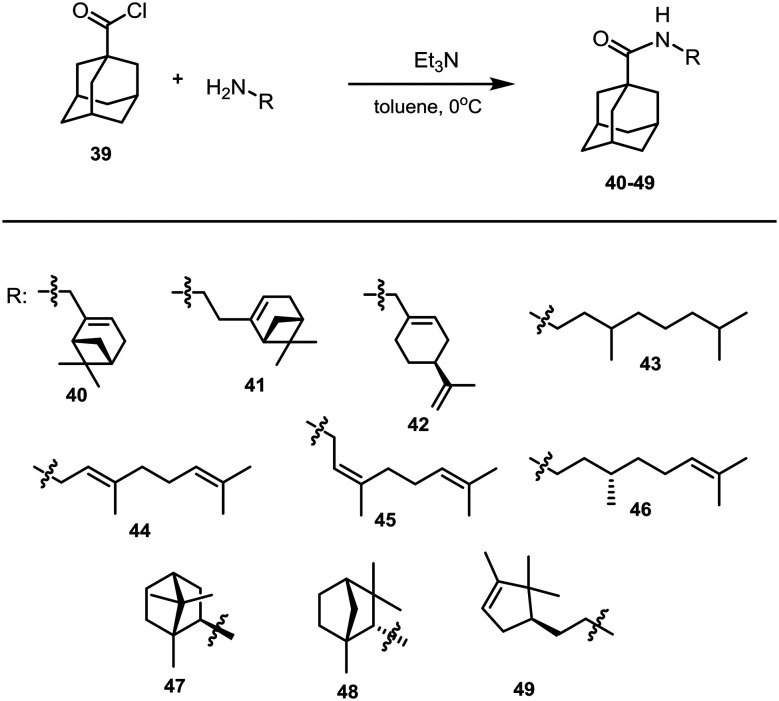

The reaction of amines 23–29 and 36–38 with 1-adamantanecarboxylic acid chloride 39 was used to prepare target amides 40–49 in yields from 12% to 99% (Scheme 3). In some cases, preparation of compounds with purity suitable for biological studies required additional purification of the resulting amides by column chromatography or recrystallization, which decreased their yields, e.g., in the case of amides 40–42 and 44–46. Compounds 43, 45, and 46 were previously described by Chepanova et al.36

Scheme 3. Synthesis of compounds 40–49.

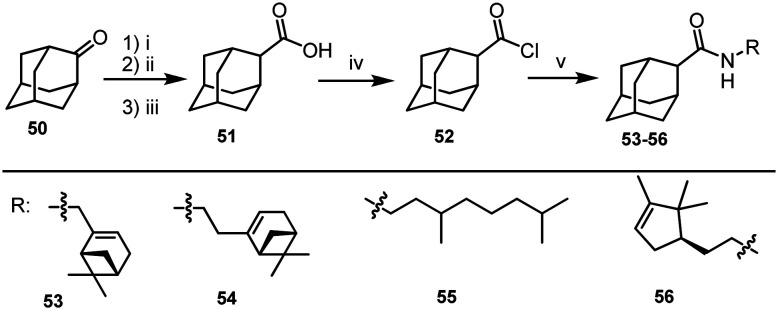

1-Adamantanecarboxylic acid chloride 39 is a commercially available reagent. Its isomer, 2-adamantane carboxylic acid chloride 52, was synthesized using 2-adamantanone 50. The method of synthesis of acid chloride 52 included preparation of an appropriate oxirane by reacting 50 with trimethylsulfoxonium iodide,37 opening of the epoxide group to form the aldehyde, and oxidizing the resulting aldehyde to acid 51 using the Jones reagent.38 2-Adamantane carboxylic acid chloride 52 was prepared according to the procedure39 by boiling acid 51 in SOCl2 (Scheme 4). Another series of amides 53–56 were prepared by reacting acid chloride 52 with amines 23, 24, 26, and 38 (Scheme 4).

Scheme 4. Reagents and conditions: (i) Me3SO+I–, NaOH, iPrOH, reflux; (ii) BF3·Et2O, benzene, stirring, 1 min; (iii) CrO3/H2SO4/H2O, Et2O; (iv) SOCl2, reflux, 4 h; (v) corresponding amine (1 eq.), Et3N (1.1 eq.), dry toluene, 0 °C.

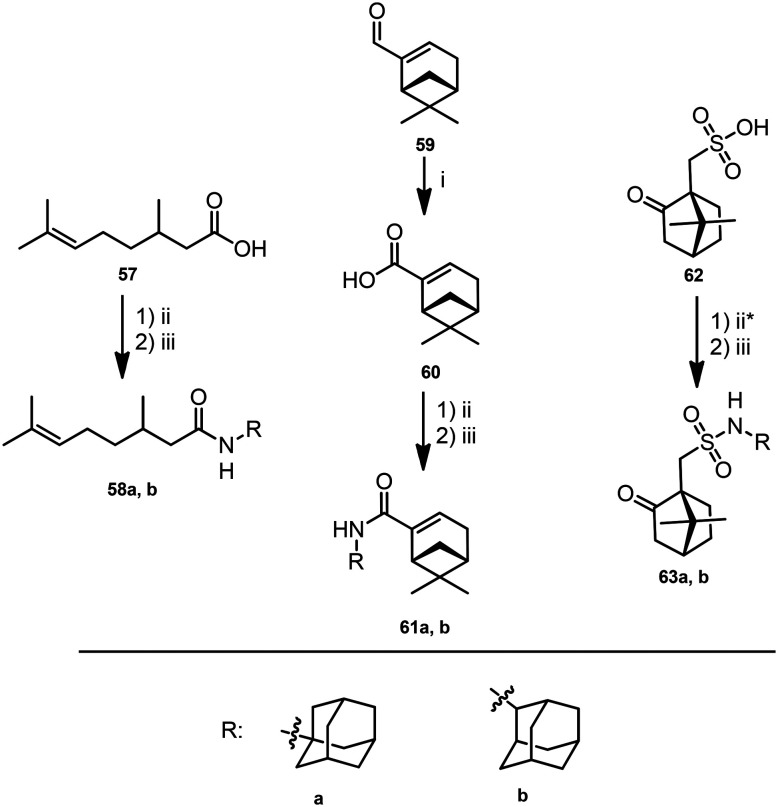

Given the commercial availability of citronellic acid 57, the appropriate acid chloride was synthesized, the interaction of which with 1- and 2-aminoadamantanes gave amides 58a and 58b (Scheme 5). Chromatographic purification of the compounds resulted in mixtures containing, along with amides 58a or 58b, starting acid 57. Treatment of the resulting mixtures with a NaOH solution was found to not remove the acid. However, replacement of sodium hydroxide with potassium hydroxide led to complete removal of the residual acid, as a salt, into the aqueous phase. Compounds 58a and 58b were obtained in yields of 70% and 72%, respectively.

Scheme 5. Reagents and conditions: (i) NaClO2, KH2PO4, H2O2, t-BuOH; (ii) SOCl2, dry benzene as a solvent, reflux, 4 h; * without solvent (iii) corresponding amine (1 eq.), Et3N (1.1 eq.), dry toluene, 0 °C.

Myrtenic acid chloride was prepared by oxidation of (–)-myrtenal 59 to the appropriate acid 60 with sodium chlorite under slightly acidic conditions, according to the procedure in ref. 40 (Scheme 5) and subsequent boiling with SOCl2. Its interaction with 1- and 2-aminoadamantanes provided appropriate amides 61a and 61b (Scheme 5) in yields of 71% and 30%, respectively.

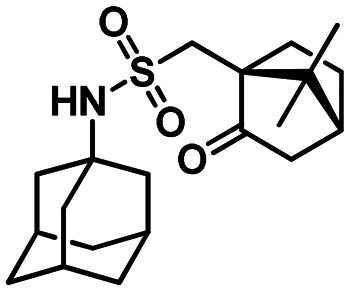

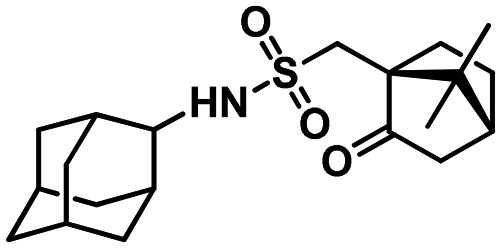

Sulfonamides 63a and 63b were synthesized from camphorsulfonic acid 62 according to a procedure similar to that used for the preparation of citronellic acid amides, which involved the synthesis of an appropriate acid chloride and its interaction with aminoadamantanes (Scheme 5). The yields of compounds 63a and 63b were 50% and 34%, respectively.

Biology

Compounds were screened for virus inhibitory activity (IC50) against orthopoxviruses using the vaccinia virus (Copenhagen strain) in Vero cell culture; cytotoxicity (CC50) of the compounds was studied in the same cell culture (Table 1). Cytotoxicity and inhibitory activity were assessed in Vero cell culture using an adapted colorimetric method.41 As positive controls, i.e. agents with established antiviral activity against orthopoxviruses, two compounds were used: the commercially available drug cidofovir (Heritage Consumer Products, USA) and ST-246, synthesized for research purposes in the Novosibirsk Institute of Organic Chemistry according to the method described by the authors.42 These anti-orthopoxvirus drugs, which exhibit different mechanisms of action, were used not only for comparison, but as verified internal standards to confirm the normal functioning of the virus–cell system for testing the activity of the newly studied drugs.

Table 1. Indicators of cytotoxicity (CC50) and antiviral activity (IC50) of amides 40–49, 53–56, 58a, 58b, 61a, 61b, 63a and 63b against the vaccinia virus (VV) in Vero cell culture.

| Compound | CC50, μM | IC50, μM | SI |

40

40

|

1908.6 ± 101.4 | 1.7 ± 0.2 | 1123 |

41

41

|

750.2 ± 84.6 | 1.8 ± 0.2 | 417 |

42

42

|

319.0 ± 39.6 | 12.3 ± 0.8 | 26 |

43

43

|

17.3 | na | — |

44

44

|

18.9 ± 2.3 | 5.9 ± 0.6 | 3 |

45

45

|

12.9 | na | — |

46

46

|

18.1 ± 2.2 | 3.6 ± 0.2 | 5 |

47

47

|

316.7 ± 39.3 | 10.6 ± 0.7 | 30 |

48

48

|

316.9 ± 39.3 | 14.4 ± 0.9 | 22 |

49

49

|

316.9 ± 39.3 | 2.5 ± 0.2 | 126 |

53

53

|

1225.9 ± 143.9 | 4.6 ± 0.2 | 267 |

54

54

|

372.5 ± 97.7 | 4.4 ± 0.1 | 85 |

55

55

|

13.7 ± 1.7 | 2.8 ± 0.2 | 5 |

56

56

|

316.7 ± 39.3 | 2.6 ± 0.2 | 122 |

58a

58a

|

37.0 ± 4.6 | 3.1 ± 0.2 | 12 |

58b

58b

|

329.5 ± 40.8 | 14.8 ± 0.9 | 22 |

61a

61a

|

7.9 ± 0.9 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 11 |

61b

61b

|

811.5 ± 110.5 | 2.5 ± 0.1 | 325 |

63a

63a

|

164.2 ± 20.3 | 2.3 ± 0.1 | 71 |

63b

63b

|

95.8 ± 11.8 | 0.6 ± 0.04 | 160 |

| Cidofovir | 475.3 ± 30.1 | 40.0 ± 1.2 | 12 |

| ST-246 | 1276 ± 202 | 0.01 ± 0.003 | 127 600 |

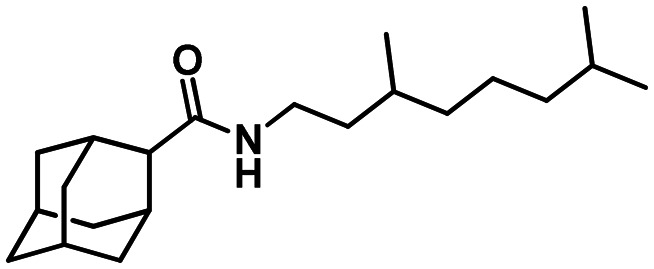

An analysis of the data presented in Table 1 shows that amides containing acyclic monoterpene substituents (compounds 43–46, 55, 58a, and 58b) mainly exhibited moderate inhibitory activity or no activity against the vaccinia virus (IC50: 2.8–14.8 μM) and fairly high toxicity to Vero cells (CC50: 12.9–37.0 μM), which led to low selectivity indices (SI). Amide 58b derived from citronellolic acid and 2-aminoadamantane was the least cytotoxic compound in this group (CC50: 330 μM), which, in combination with an IC50 value of 14.8 μM, led to a SI of 22. The results comparable to those of compound 58b were also obtained for a monocyclic perillyl alcohol monoterpene derivative 42. Amides 43 and 45 containing 3,7-dimethyloctanol and nerol moieties had no activity against the vaccinia virus, but were highly toxic (CC50: 17 μM and 13 μM, respectively).

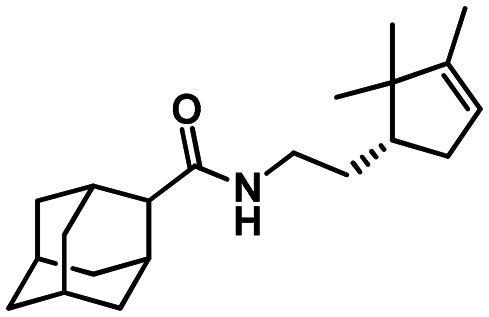

Transition to compounds containing a (–)-campholenaldehyde moiety, amides 49 and 56, demonstrates that compounds 49 and 56 having activity comparable to that of derivatives containing acyclic monoterpenoid substituents exhibited lower cytotoxicity, which led to a good SI of about 126 and 122, respectively, with the latter being independent of the amide group location in the adamantane scaffold.

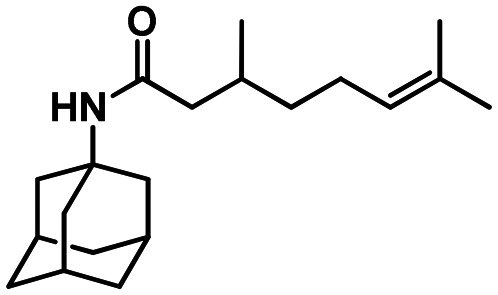

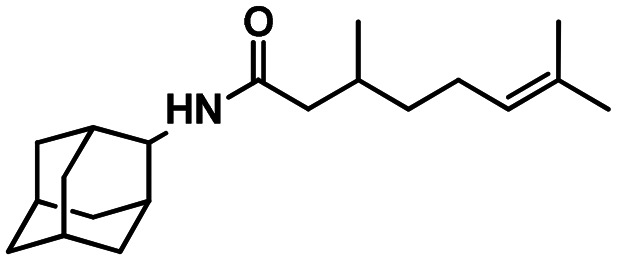

Among the studied compounds, the most promising group was that containing bicyclic monoterpenoid moieties ((–)-10-amino-2-pinene: 40, 41, 53, 54, 61a, and 61b; camphor: 47, 63a, and 63b; and fenchone: 48). In this group, there were amides with a maximum selectivity index, such as compound 40 with a SI of 1123.

Comparison of amides 40, 53, 41, and 54 reveals that an increase in the length of the linker between adamantane and monoterpene moieties increases the cytotoxicity of the compounds. Furthermore, as follows from Table 1, 1-adamantanecarboxylic acid derivatives have higher activity than 2-adamantanecarboxylic acid derivatives. Introduction of camphor or fenchone as substituents decreases the activity of the compounds (i.e. increases IC50), as in amides 47 and 48. Transition to sulfamides 63a and 63b reveals that the activity of these compounds increases compared to that of amides 47 and 48, but compounds 63a and 63b are more cytotoxic than 47 and 48. Unlike amides 40, 45, 41, and 54, higher activity among compounds 63a and 63b was demonstrated by the substance with a substituent at position 2 of the adamantane moiety. 2-Aminoadamantane derivative 61b has a selectivity index an order of magnitude higher than that of compound 61a, which is mainly due to the high cytotoxicity of amide 61a. In this case, almost all amides containing bicyclic monoterpenoid substituents showed higher activity (IC50: 0.6–14.4 μM) than the reference drug cidofovir (IC50: 40 μM), and their selectivity index exceeded the SI of the reference drug by two orders of magnitude. For amides that are structurally similar and could be considered as amides containing an amide bond with a reversed direction, different trends were found. In general, transition to amides of monoterpene acids 58a, 61a, 61b leads to slightly increased activity compared to derivatives of adamantane carboxylic acids 40, 46, 53. At the same time, the derivatives of myrtenic acid 61a and 61b showed higher cytotoxicity than their analogs – amides, containing myrtenic fragment 40 and 53. On the other hand, the amide of citronellic acid 58a was found to be about 2 times less cytotoxic than 1-adamantane carboxylic acid derivative 46.

In summary, bicyclic monoterpene derivatives demonstrate higher activity than the acyclic and monocyclic monoterpene ones. Moreover, bicyclic derivatives show scientifically lower cytotoxicity leading to an increased SI. Sulfonamides were found to be more active as well as more cytotoxic than their structural analogs, derivatives of camphor. In general, amides containing the 1-adamantanane fragment were more active than isomeric 2-adamantane substituted derivatives.

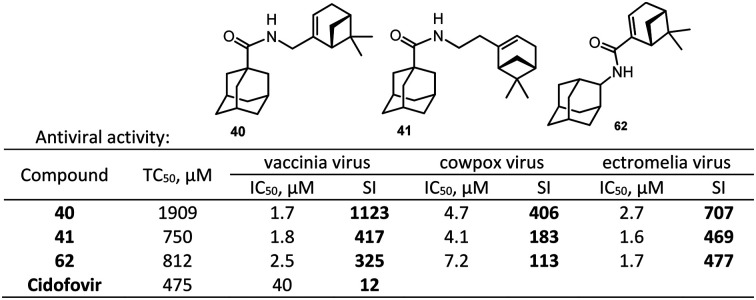

Therefore, initial screening revealed the highest activity combined with low cytotoxicity in compounds containing bicyclic monoterpenoid moieties. For further study, we selected amides containing the (–)-10-amino-2-pinene moiety (amides 40, 41, 53, 54, and 61b) because this group included compound 40 that showed the highest SI among the investigated compounds. These compounds were tested for activity against cowpox (CPXV, Grishak strain) and mousepox (ectromelia virus (ECTV), K-1 strain) viruses (Table 2).

Table 2. Indicators of cytotoxicity (CC50) and antiviral activity (IC50) of amides 40, 41, 53, 54, and 61b against the cowpox virus (CPXV) and ectromelia virus (ECTV) in Vero cell culture.

| Compound | CC50, μM (M ± Sm, n = 3) | CPXV |

ECTV |

||

| IC50, μM (M ± SD, n = 3) | SI | IC50, μM (M ± SD, n = 3) | SI | ||

| 40 | 1908.6 ± 101.4 | 4.7 ± 0.2 | 406 | 2.7 ± 0.2 | 707 |

| 41 | 750.2 ± 84.6 | 4.1 ± 0.6 | 183 | 1.6 ± 0.6 | 469 |

| 53 | 1225.9 ± 143.9 | 15.0 ± 0.2 | 82 | 12.6 ± 0.2 | 97 |

| 54 | 372.5 ± 97.7 | 12.5 ± 0.1 | 30 | 9.5 ± 0.1 | 39 |

| 61b | 811.5 ± 110.5 | 7.2 ± 0.2 | 113 | 1.7 ± 0.2 | 477 |

Amides 40, 41, 53, 54, and 61b showed high activity against the mousepox virus. In this case, 1-adamantanecarboxylic acid derivatives (compounds 40 and 41) were more active than 2-adamantanecarboxylic acid derivatives (compounds 53 and 54) (Table 2). This trend is observed for all studied orthopoxviruses.

The cytotoxicity of most tested compounds was 2-fold or lower as compared to the reference drug cidofovir. In this case, there were compounds whose selectivity index was more than two orders of magnitude higher than that of the reference drug, e.g., amide 40 with a SI of 1123, synthesized based on 1-adamantane carboxylic acid chloride 39 and (–)-10-amino-2-pinene 23. In our work we didn't investigate the mechanism of action of the new adamantane derivatives, since the objective of this study was to demonstrate the anti-orthopoxvirus activity of our synthesized adamantane–monoterpene conjugates and to identify the most active ones.

Therefore, in this study, we discovered a new type of highly effective low-toxic orthopoxvirus inhibitors combining monoterpenoid and adamantane moieties via an amide linker.

Conclusions

In this study, we investigated a series of new amides for their inhibitory activity against orthopoxviruses (vaccinia virus – VV, cowpox virus – CPXV, mousepox virus – ectromelia virus – ECTV). For this purpose, we synthesized a series of new amides 40–49 and 53–56 combining adamantane and monoterpene moieties; they were prepared starting from monoterpene amines 23–29 and 36–38, which were then acylated with 1- and 2-adamantanecarboxylic acid chlorides. Some amides (58, 59, 61a, 61b, 63a, and 63b) were also prepared starting from 1- and 2-aminoadamantanes. Almost all amides containing bicyclic (β-bornane and pinene) monoterpenoid substituents exhibit higher activity (IC50: 0.59–14.40 μM) than the reference drug cidofovir (IC50: 40 μM), and their selectivity index exceeds that of the reference drug by two orders of magnitude towards the vaccinia virus. The highest activity in combination with low cytotoxicity was exhibited by compounds containing a pinene moiety: 40, 41, 53, 54, and 61b. These compounds were also active against cowpox (SI: 30–406) and mousepox (SI: 39–707) viruses. 1-Adamantanecarboxylic acid amide 40 containing the (–)-10-amino-2-pinene moiety was the most effective (SI(VV) = 1123, SI(CPXV) = 406, SI(ECTV) = 707); this compound is promising for further investigation as a potential antiviral drug for the treatment of orthopoxvirus infection, including smallpox.

Materials and methods

Chemistry

All chemicals were purchased from commercial vendors and used without further purification, unless indicated otherwise. Column chromatography was performed using silica gel (60–230 μ, Macherey-Nagel) and a solution containing 0% to 5% ethyl acetate in hexane. Optical rotations [α]T°CD were measured on a PolAAr 3005 polarimeter, and the optical rotation values are given in 10–1 deg cm2 g–1. 1H- and 13C-NMR spectra were registered on a Bruker DRX-500 spectrometer (500.13 MHz (1H) and 125.76 MHz (13C) in CDCl3) and on Bruker Avance – III 600 (600.30 MHz (1H) and 150.95 MHz (13C) in CDCl3). Chemical shifts obtained are given in ppm, relative to residual chloroform (δH 7.24, δC 76.90 ppm), and J values are given in Hz. The compound structures were determined by analyzing their 1H-NMR spectra; 1H, 1H double resonance spectra and 2D correlation spectra 1H–1H (COSY, NOESY); J-modulated 13C-NMR spectra (JMOD) and 13C,1H-type 2D heteronuclear correlation with one-bond and long-range spin–spin coupling constants (COSY and HSQC, J(C,H) = 135 Hz and 145 Hz, respectively, COLOC and HMBC,2,3 J(C,H) = 10 Hz and 7 Hz, respectively). Numeration of atoms in the compounds (see the ESI†) is given for assigning the signals in the NMR spectra and does not coincide with the nomenclature of the compounds. The elemental composition of the compounds was determined from the high-resolution mass spectra (HR-MS) recorded on a DFS Thermo Scientific spectrometer in full scan mode (0–500 m/z, 70 eV electron impact ionization, direct sample injection). The conversion of the reagents, the content of the compounds in fractions during chromatography and the purity of the target compounds were determined using gas chromatography methods: 7820A gas chromatograph (Agilent Tech., USA), flame-ionization detector, HP-5 capillary column (0.25 mm × 3 m × 0.25 μm), helium carrier gas (flow rate 2 mL min–1, flow division 99 : 1), temperature range from 120 °C to 280 °C, heating 20 °C min–1. The purity of the target compounds for biological testing was confirmed to be more than 95%.

General synthesis procedure

To carboxylic or sulfonic acid chloride (1 eq.) in dry toluene solution (5 ml) was added triethylamine (1.1 eq.), and the corresponding amine (1 eq.) in dry toluene (1 ml) was added to the solution at 0 °C, the resulting mixture was stirred for 12 hours at room temperature. Toluene was evaporated, and the residue was treated with 10 ml of 5% NaOH (5% KOH in the case of 58a and 58b) and extracted with EtOAc (3 × 20 ml). The organic layer was washed with 20 ml of saturated NaCl solution and dried over sodium sulfate and the solvent was distilled off. The resulting amide was purified by silica gel column chromatography. The synthesis and characterization of adamantane derivatives 43, 45, 55, 58a, 58b were published previously.36

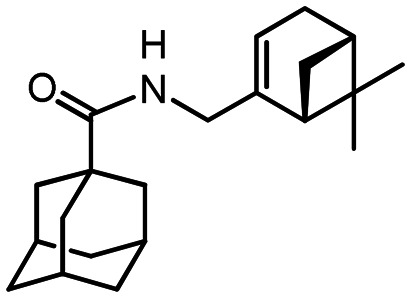

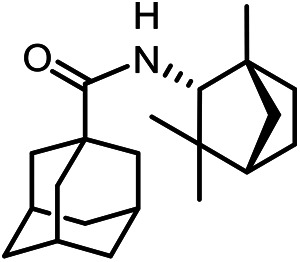

N-(((1R,5S)-6.6-Dimethylbicyclo[3.1.1]hept-2-en-2-yl)methyl)adamantane-1-carboxamide 40

Yield 42%. [α]25D = –19 (c 0.78 in MeOH). δH (600 MHz, CDCl3) 0.81 (3 H, s, 22-Me), 1.12 (1 H, d, J20anti,20sin = 8.6, 20-Hanti), 1.24 (3 H, s, 21-Me), 1.64–1.74 (6 H, m, 4-2H, 6-2H, 10-2H), 1.82 (6 H, d, 3J = 3.0, 2-2H, 8-2H, 9-2H), 1.99 (1 H, ddd, J19,17 = J19,20sin = 5.6, J19,15 = 1.5, 19-H), 1.99–2.03 (3 H, m, 3-H, 5-H, 7-H), 2.05–2.09 (1 H, m, 17-H), 2.18 (1 H, dm, 2J = 17.7, 16-H), 2.25 (1 H, dm, 2J = 17.7, 16-H′), 2.35 (1 H, ddd, J20sin,20anti = 8.6, J20sin,17 = J20sin,19 = 5.6, 20-Hsin), 3.69 (1 H, ddm, 2J = 15.2, J13,NH = 5.4, 13-H), 3.78 (1 H, ddm, 2J = 15.2, J13′,NH = 6.0, 13-H′), 5.32–5.35 (1 H, m, 15-H), 5.45–5.52 (1 H, br m, NH). δC (150 MHz, CDCl3) 40.58 (s, C-1), 39.26 (t, C-2, C-8, C-9), 28.04 (d, C-3, C-5, C-7), 34.42 (t, C-4, C-6, C-10), 177.54 (s, C-11), 43.70 (t, C-13), 144.82 (s, C-14), 118.20 (d, C-15), 31.02 (t, C-16), 40.65 (d, C-17), 37.82 (s, C-18), 43.90 (d, C-19), 31.39 (t, C-20), 26.00 (q, C-21), 21.13 (q, C-22). m/z 313.2396 (M+ C21H31O1N1+, calc. 313.2400).

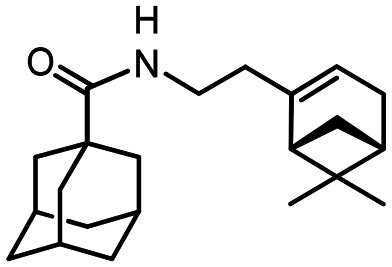

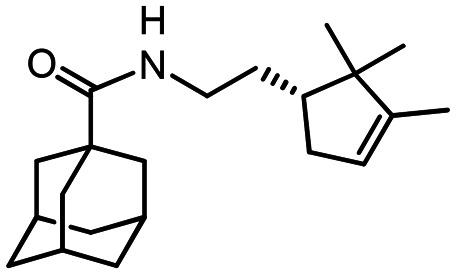

N-(2-((1R,5S)-6.6-Dimethylbicyclo[3.1.1]hept-2-en-2-yl)ethyl)adamantane-1-carboxamide 41

Yield 31%. [α]24D = –20 (c 1.25 in MeOH). δH (500 MHz, CDCl3) 0.81 (3 H, s, 23-Me), 1.08 (1 H, d, 2J = 8.6, 21-Hanti), 1.24 (3 H, s, 22-Me), 1.62–1.73 (6 H, m, 4-2H, 6-2H, 10-2H), 1.79 (6 H, d, 3J = 3.0, 2-2H, 8-2H, 9-2H), 1.97–2.04 (4 H, m, 3-H, 5-H, 7-H, 20-H), 2.05–2.14 (3 H, m, 14-2H, 18-H), 2.19 (1 H, dm, 2J = 17.7, 17-H), 2.25 (1 H, dm, 2J = 17.7, 17-H′), 2.36 (1 H, ddd, 2J = 8.6, J21cis,18 = 5.6, J21cis,20 = 5.6, 21-Hcis), 3.14–3.29 (2 H, m, 13-2H), 5.25–5.28 (1 H, m, 16-H), 5.59 (1 H, br s, NH). δC (125 MHz, CDCl3) 40.41 (s, C-1), 39.12 (t, C-2, C-8, C-9), 28.00 (d, C-3, C-5, C-7), 36.41 (t, C-4, C-6, C-10), 177.57 (s, C-11), 36.36 (t, C-13), 36.30 (t, C-14), 145.47 (s, C-15), 118.59 (d, C-16), 31.24 (t, C-17), 40.54 (d, C-18), 37.72 (s, C-19), 45.10 (d, C-20), 31.67 (t, C-21), 26.05 (q, C-22), 21.12 (q, C-23). m/z 327.2552 (M+ C22H33O1N1+, calc. 327.2557).

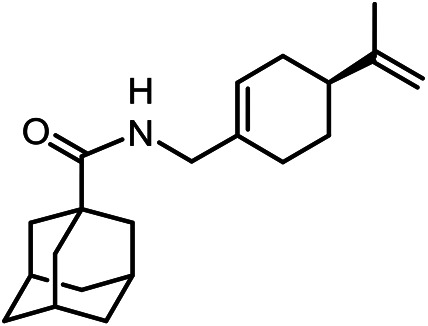

N-(((S)-4-(Prop-1-en-2-yl)cyclohex-1-en-1-yl)methyl)adamantane-1-carboxamide 42

Yield 23%. [α]24D = –46 (c 1.60 in MeOH). δH (500 MHz, CDCl3) 1.38–1.48 (1 H, m, 18-Ha), 1.64–1.75 (6 H, m, 4-2H, 6-2H, 10-2H), 1.70 (3 H, s, 22-Me), 1.76–1.82 (1 H, m, 18-He), 1.84 (6 H, d, 3J = 3.0, 2-2H, 8-2H, 9-2H), 1.85–2.14 (8 H, m, 3-H, 5-H, 7-H, 16-2H, 17-H, 19-2H), 3.68–3.79 (2 H, m, 13-2H), 4.66–4.70 (2 H, m, 21-2H), 5.50–5.54 (1 H, m, 15-H), 5.55–5.62 (1 H, br m, NH).δC (125 MHz, CDCl3) 40.56 (s, C-1), 39.22 (t, C-2, C-8, C-9), 28.00 (d, C-3, C-5, C-7), 36.39 (t, C-4, C-6, C-10), 177.68 (s, C-11), 44.54 (t, C-13), 134.42 (s, C-14), 122.01 (d, C-15), 30.33 (t, C-16), 40.90 (d, C-17), 27.31 (t, C-18), 26.85 (t, C-19), 149.62 (s, C-20), 108.53 (t, C-21), 20.63 (q, C-22). m/z 313.2402 (M+ C21H31O1N1+, calc. 313.2400).

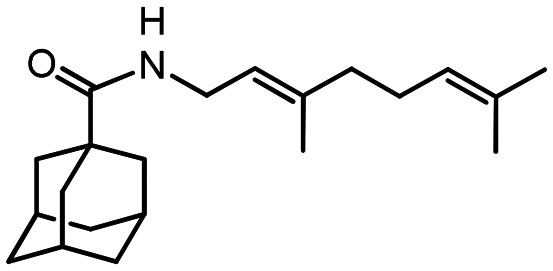

N-((E)-3.7-Dimethylocta-2.6-dien-1-yl)adamantane-1-carboxamide 44

Yield 29%. δH(600 MHz, CDCl3) 1.58 (3 H, br s, 21-Me), 1.64 (3 H, br s, 22-Me), 1.66 (3 H, m, 20-Me), 1.64–1.74 (6 H, m, 4-2H, 6-2H, 10-2H), 1.82 (6 H, d, 3J = 3.0, 2-2H, 8-2H, 9-2H), 1.96–2.03 (5 H, m, 3-H, 5-H, 7-H, 16-2H), 2.03–2.09 (2 H, m, 17-2H), 3.80 (2 H, br t, J13,14 ≈ 7.0, 13-2H), 5.05 (1 H, tm, J18,17 = 7.0, 18-H), 5.15 (1 H, tm, J14,13 = 7.0, 14-H), 5.43 (1 H, br s, NH). δC(150 MHz, CDCl3) 40.42 (s, C-1), 39.17 (t, C-2, C-8, C-9), 28.03 (d, C-3, C-5, C-7), 36.43 (t, C-4, C-6, C-10), 177.60 (s, C-11), 37.23 (t, C-13), 120.08 (d, C-14), 139.77 (s, C-15), 39.36 (t, C-16), 26.25 (t, C-17), 123.74 (d, C-18), 131.60 (s, C-19), 25.57 (q, C-20), 17.59 (q, C-21), 16.16 (q, C-22). m/z 315.2554 (M+ C21H33O1N1+, calc. 315.2557).

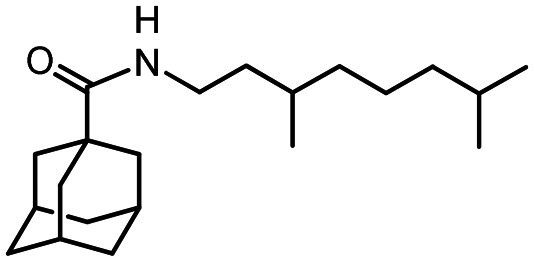

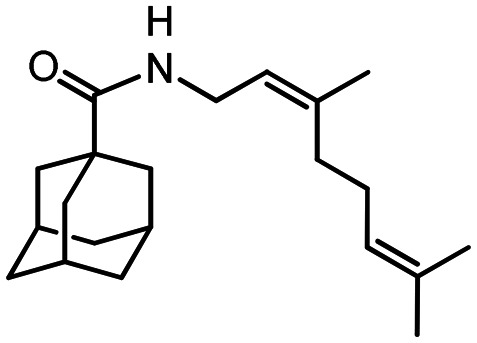

N-((S)-3.7-Dimethyloct-6-en-1-yl)adamantane-1-carboxamide 46

Yield 32%. [α]25D = +6 (c 0.87 in MeOH). δH(600 MHz, CDCl3) 0.87 (3 H, d, J22,15 = 6.6, 22-Me), 1.10–1.17 (1 H, m, 16-H), 1.22–1.34 (2 H, m, 14-H, 16-H′), 1.38–1.50 (2 H, m, 14-H′, 15-H), 1.57 (3 H, br s, 21-Me), 1.64 (3 H, br s, 20-Me), 1.63–1.73 (6 H, m, 4-2H, 6-2H, 10-2H), 1.81 (6 H, d, 3J = 3.0, 2-2H, 8-2H, 9-2H), 1.87–2.02 (5 H, m, 3-H, 5-H, 7-H, 17-2H), 3.16–3.27 (2 H, m, 13-2H), 5.04 (1 H, tm, J18,17 = 7.2, 18-H), 5.51 (1 H, br s, NH). δC(150 MHz, CDCl3) 40.37 (s, C-1), 39.14 (t, C-2, C-8, C-9), 28.00 (d, C-3, C-5, C-7), 36.40 (t, C-4, C-6, C-10), 177.68 (s, C-11), 37.23 (t, C-13), 36.47 (t, C-14), 30.06 (d, C-15), 36.79 (t, C-16), 25.23 (t, C-17), 124.45 (d, C-18), 131.20 (s, C-19), 25.57 (q, C-20), 17.54 (q, C-21), 19.30 (q, C-22). m/z 317.2717 (M+ C21H35O1N1+, calc. 317.2713).

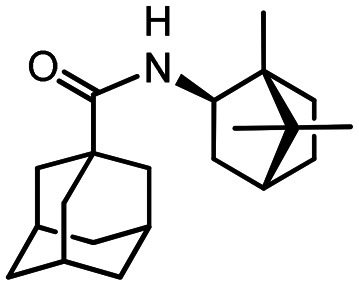

N-((1R,2R,4R)-1.7.7-Trimethylbicyclo[2.2.1]heptan-2-yl)adamantane-1-carboxamide 47

Yield 98%. [α]25D = –38 (c 0.94 in MeOH). δH(500 MHz, CDCl3) 0.78 (3 H, s, 20-Me), 0.80 (3 H, s, 21-Me), 0.89 (3 H, s, 22-Me), 1.12 (1 H, ddd, 2J = 12.3, J16endo,15endo = 9.4, J16endo,15exo = 4.5, 16-Hendo), 1.26 (1 H, ddd, 2J = 12.8, J15endo,16endo = 9.4, J15endo,16exo = 4.1, 15-Hendo), 1.45–1.56 (2 H, m, 15-Hexo, 18-Hexo), 1.62–1.74 (8 H, m, 4-2H, 6-2H, 10-2H, 16-Hexo, 17-H), 1.79 (6 H, d, 3J = 2.7, 2-2H, 8-2H, 9-2H), 1.82 (1 H, dd, 2J = 13.3, J18endo,13endo = 9.1, 18-Hendo), 1.96–2.04 (3 H, m, 3-H, 5-H, 7-H), 3.86 (1 H, ddd, J13endo,18endo = 9.1, J13,12 = 8.9, J13endo,18exo = 5.0, 13-Hendo), 5.54 (1 H, br d, J12,13 = 8.9, NH). δC(125 MHz, CDCl3) 40.41 (s, C-1), 39.27 (t, C-2, C-8, C-9), 28.08 (d, C-3, C-5, C-7), 36.44 (t, C-4, C-6, C-10), 176.78 (s, C-11), 55.82 (d, C-13), 48.31 (s, C-14), 35.74 (t, C-15), 26.90 (t, C-16), 44.80 (d, C-17), 39.14 (t, C-18), 46.89 (s, C-19), 11.49 (q, C-20), 20.13, 20.14 (2q, C-21, C-22). m/z 315.2553 (M+ C21H33O1N1+, calc. 315.2553).

N-((1R,2R,4S)-1.3.3-Trimethylbicyclo[2.2.1]heptan-2-yl)adamantane-1-carboxamide 48

Yield 99%. [α]20D = +22 (c 0.56 in MeOH). δH(600 MHz, CDCl3) 0.72 (3 H, s, 21-Me), 0.99 (3 H, s, 22-Me), 1.09 (3 H, s, 20-Me), 1.12–1.21 (3 H, m, 17-2H, 19-Hanti), 1.39–1.47 (1 H, m, 16-Hexo), 1.60–1.65 (2 H, m, 16-Hendo, 19-Hsin), 1.66–1.75 (7 H, m, 4-2H, 6-2H, 10-2H, 15-H), 1.85 (6 H, d, 3J = 2.6, 2-2H, 8-2H, 9-2H), 2.00–2.04 (3 H, m, 3-H, 5-H, 7-H), 3.54 (1 H, dd, J13exo,12 = 9.0, J13exo,17exo = 1.6, 13-Hexo), 5.60 (1 H, br d, J12,13 ≈ 9.0, NH). δC(150 MHz, CDCl3) 40.85 (s, C-1), 39.48 (t, C-2, C-8, C-9), 28.11 (d, C-3, C-5, C-7), 36.45 (t, C-4, C-6, C-10), 178.23 (s, C-11), 62.34 (d, C-13), 38.94 (s, C-14), 48.06 (d, C-15), 25.75 (t, C-16), 27.35 (t, C-17), 48.21 (s, C-18), 42.42 (t, C-19), 30.60 (q, C-20), 20.87 (q, C-21), 19.48 (q, C-22). m/z 315.2560 (M+ C21H33O1N1+, calc. 315.2557).

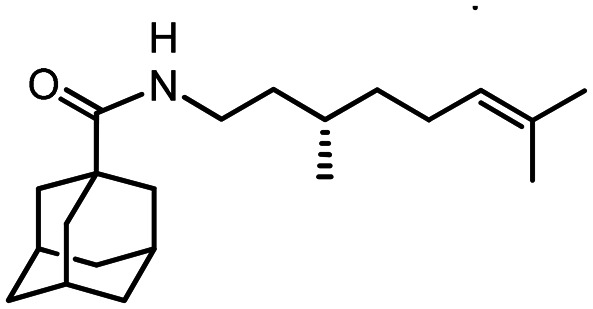

N-(2-((R)-2.2.3-Trimethylcyclopent-3-en-1-yl)ethyl)adamantane-1-carboxamide 49

Yield 55%. [α]19D = –11 (c 0.4 in MeOH). δH(600 MHz, CDCl3) 0.71 (3 H, s, 21-Me), 0.92 (3 H, s, 20-Me), 1.35–1.43 (1 H, m, 14-H), 1.55 (3 H, m, 22-Me), 1.55–1.72 (8 H, m, 4-2H, 6-2H, 10-2H, 14-H′, 15-H), 1.80 (6 H, d, 3J = 3.0, 2-2H, 8-2H, 9-2H), 1.80–1.85 (1 H, m, 19-H), 1.97–2.01 (3 H, m, 3-H, 5-H, 7-H), 2.23–2.29 (1 H, m, 19-H′), 3.13–3.20 (1 H, m, 13-H), 3.23–3.30 (1 H, m, 13-H′), 5.16–5.19 (1 H, m, 18-H), 5.62 (1 H, br s, NH). δC(150 MHz, CDCl3) 40.36 (s, C-1), 39.14 (t, C-2, C-8, C-9), 27.99 (d, C-3, C-5, C-7), 36.38 (t, C-4, C-6, C-10), 177.62 (s, C-11), 38.68 (t, C-13), 29.92 (t, C-14), 47.93 (d, C-15), 46.66 (s, C-16), 148.35 (s, C-17), 121.42 (d, C-18), 35.37 (t, C-19), 25.56 (q, C-20), 19.51 (q, C-21), 12.41 (q, C-22). m/z 315.2553 (M+ C21H33O1N1+, calc. 315.2557).

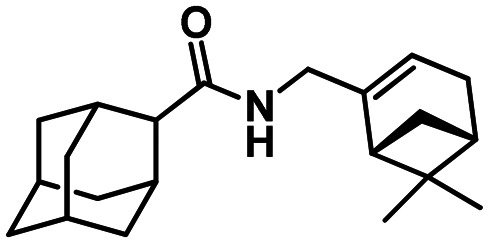

N-(((1R,5S)-6.6-Dimethylbicyclo[3.1.1]hept-2-en-2-yl)methyl)adamantane-2-carboxamide 53

Yield 46%. [α]25D = –16 (c 0.62 in MeOH). δH(600 MHz, CDCl3) 0.80 (3 H, s, 22-Me), 1.13 (1 H, d, J20anti,20sin = 8.7, 20-Hanti), 1.24 (3 H, s, 21-Me), 1.57–1.62 (2 H, m, 4-H, 9-H), 1.69–1.77 (4 H, m, 6-2H, 8-H, 10-H), 1.80–1.84 (1 H, m, 5-H or 7-H), 1.84–1.95 (5 H, m, 7-H or 5-H, 8-H′, 10-H′, 4-H′, 9-H′), 2.04 (1 H, ddd, J19,17 = J19,20sin = 5.6, J19,15 = 1.4, 19-H), 2.05–2.09 (1 H, m, 17-H), 2.18 (1 H, dm, 2J = 17.7, 16-H), 2.20–2.28 (3 H, m, 1-H, 3-H, 16-H′), 2.35 (1 H, ddd, J20sin,20anti = 8.7, J20sin,17 = J20sin,19 = 5.6, 20-Hsin), 2.42–2.45 (1 H, br s, 2-H), 3.76 (1 H, ddm, 2J = 15.1, J13,NH = 6.0, 13-H), 3.83 (1 H, ddm, 2J = 15.1, J13′,NH = 6.0, 13-H′), 5.34–5.37 (1 H, m, 15-H), 5.45–5.56 (1 H, br m, NH). δC(150 MHz, CDCl3) 29.81 and 30.00 (2d, C-1, C-3), 49.98 (d, C-2), 33.21 and 33.28 (2t, C-4, C-9), 27.30 and 27.39 (2d, C-5, C-7), 37.26 (t, C-6), 38.25 (t, C-8, C-10), 173.71 (s, C-11), 43.85 (t, C-13), 144.92 (s, C-14), 118.47 (d, C-15), 31.03 (t, C-16), 40.65 (d, C-17), 37.83 (s, C-18), 43.93 (d, C-19), 31.44 (t, C-20), 25.99 (q, C-21), 21.02 (q, C-22). m/z 313.2402 (M+ C21H31O1N1+, calc. 313.2400).

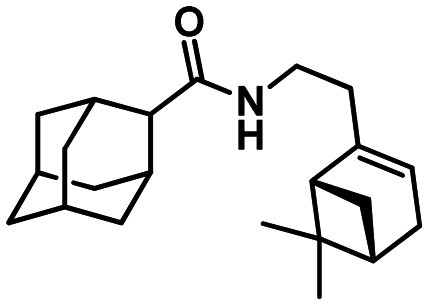

N-(2-((1R,5S)-6.6-Dimethylbicyclo[3.1.1]hept-2-en-2-yl)ethyl)adamantane-2-carboxamide 54

Yield 31%. [α]24D = –19 (c 0.93 in MeOH). δH(600 MHz, CDCl3) 0.78 (3 H, s, 23-Me), 1.06 (1 H, d, 2J = 8.7, 21-Hanti), 1.22 (3 H, s, 22-Me), 1.53–1.58 (2 H, br d, 2J = 12.8, 4-H, 9-H), 1.66–1.73 (4 H, m, 6-2H, 8-H, 10-H), 1.76–1.80 (1 H, m, 5-H or 7-H), 1.81–1.91 (5 H, m, 4-H′, 7-H or 5-H, 8-H′, 9-H′, 10-H′), 2.01 (1H, ddd, J20,18 = J20,21cis = 5.6, J20,16 = 1.3, 20-H), 2.03–2.07 (1 H, m, 18-H), 2.09–2.24 (6 H, m, 1-H, 3-H, 14-2H, 17-2H), 2.33 (1 H, ddd, 2J = 8.7, J21cis,18 = 5.6, J21cis,20 = 5.6, 21-Hcis), 2.36–2.39 (1 H, m, 2-H), 3.21–3.33 (2 H, m, 13-2H), 5.23–5.26 (1 H, m, 16-H), 5.64–5.70 (1 H, br m, NH). δC(150 MHz, CDCl3) 29.75 and 29.80 (2d, C-1, C-3), 49.85 (d, C-2), 33.12 and 33.13 (2t, C-4, C-9), 27.23 and 27.31 (2d, C-5, C-7), 37.19 (t, C-6), 38.19 (t, C-8, C-10), 173.63 (s, C-11), 36.49 (t, C-13, C-14), 145.38 (s, C-15), 118.35 (d, C-16), 31.17 (t, C-17), 40.52 (d, C-18), 37.69 (s, C-19), 45.14 (d, C-20), 31.55 (t, C-21), 26.02 (q, C-22), 20.95 (q, C-23). m/z 327.2560 (M+ C22H33O1N1+, calc. 327.2557).

N-(2-((R)-2.2.3-Trimethylcyclopent-3-en-1-yl)ethyl)adamantane-2-carboxamide 56

Yield 33%. [α]19D = –11 (c 0.74 in MeOH). δH(600 MHz, CDCl3) 0.74 (3 H, s, 21-Me), 0.95 (3 H, s, 20-Me), 1.39–1.47 (1 H, m, 14-H), 1.58 (3 H, m, all J < 3.0, 22-Me), 1.58–1.67 (3 H, m, 4-H, 9-H, 14-H′), 1.70–1.77 (5 H, m, 6-2H, 8-H, 10-H, 15-H), 1.79–1.95 (7 H, m, 4-H′, 5-H, 7-H, 8-H′, 9-H′, 10-H′, 19-H), 2.22–2.26 (2 H, m, 1-H, 3-H), 2.30 (1 H, ddm, 2J = 15.3, J19′,15 = 7.8, other J ≤ 3.0, 19-H′), 2.41 (1 H, br s, 2-H), 3.20–3.28 (1 H, m, 13-H), 3.32–3.39 (1 H, m, 13-H′), 5.19–5.22 (1 H, m, 18-H), 5.64 (1 H, br s, 12-H). δC(150 MHz, CDCl3) 29.89 and 29.94 (2d, C-1, C-3), 49.89 (d, C-2), 33.22 (t, C-4, C-9), 27.29 and 27.39 (2d, C-5, C-7), 37.27 (t, C-6), 38.27 (t, C-8, C-10), 173.90 (s, C-11), 38.73 (t, C-13), 30.11 (t, C-14), 47.90 (d, C-15), 46.72 (s, C-16), 148.44 (s, C-17), 121.46 (d, C-18), 35.36 (t, C-19), 25.64 (q, C-20), 19.59 (q, C-21), 12.47 (q, C-22). m/z 315.2558 (M+ C21H33O1N1+, calc. 315.2557).

(1R,5S)-N-(Adamantan-1-yl)-6.6-dimethylbicyclo[3.1.1]hept-2-ene-2-carboxamide 61a

Yield 71%. [α]25D = –32 (c 0.37 in MeOH). δH(600 MHz, CDCl3) 0.79 (3 H, s, 21-Me), 1.11 (1 H, d, J19anti,19sin = 9.0, 19-Hanti), 1.30 (3 H, s, 20-Me), 1.62–1.70 (6 H, m, 4-2H, 6-2H, 10-2H), 2.00 (6 H, d, 3J = 3.0, 2-2H, 8-2H, 9-2H), 2.03–2.11 (4 H, m, 3-H, 5-H, 7-H, 16-H), 2.30 (1 H, ddd, 2J = 19.0, J15,14 = J15,16 = 3.0, 15-H), 2.36 (1 H, ddd, 2J = 19.0, J15′,14 = J15′,16 = 3.0, 15-H′), 2.42 (1 H, ddd, J19sin,19anti = 9.0, J19sin,16 = J19sin,18 = 5.7, 19-Hsin), 2.56 (1 H, ddd, J18,16 = J18,19sin = 5.7, J18,14 = 1.7, 18-H), 5.35 (1 H, br s, 11-H), 6.20–6.23 (1 H, m, 14-H). δC(150 MHz, CDCl3) 51.53 (s, C-1), 41.60 (t, C-2, C-8, C-9), 29.37 (d, C-3, C-5, C-7), 36.30 (t, C-4, C-6, C-10), 166.47 (s, C-12), 144.87 (s, C-13), 127.24 (d, C-14), 31.46 (t, C-15), 40.31 (d, C-16), 37.61 (s, C-17), 41.92 (d, C-18), 31.32 (t, C-19), 25.89 (q, C-20), 20.84 (q, C-21). m/z 299.2242 (M+ C20H29O1N1+, calc. 299.2244).

(1R,5S)-N-(adamantan-2-yl)-6.6-dimethylbicyclo[3.1.1]hept-2-ene-2-carboxamide 61b

Yield 30%. [α]27D = –34 (c 0.57 in MeOH). δH(600 MHz, CDCl3) 0.80 (3 H, s, 21-Me), 1.15 (1 H, d, J19anti,19sin = 9.0, 19-Hanti), 1.31 (3 H, s, 20-Me), 1.61–1.66 (2 H, m, 4-H, 9-H), 1.70–1.77 (4 H, m, 4-H′, 9-H′, 6-2H), 1.79–1.86 (6 H, m, 5-H, 7-H, 8-2H, 10-2H), 1.90–1.94 (2 H, m, 1-H, 3-H), 2.09–2.13 (1 H, m, 16-H), 2.33 (1 H, ddd, 2J = 19.0, J15,14 = J15,16 = 3.0, 15-H), 2.39 (1 H, ddd, 2J = 19.0, J15′,14 = J15′,16 = 3.0, 15-H′), 2.44 (1 H, ddd, J19sin,19anti = 9.0, J19sin,16 = J19sin,18 = 5.7, 19-Hsin), 2.60 (1 H, ddd, J18.16 = J18,19sin = 5.7, J18.14 = 1.7, 18-H), 4.03–4.07 (1 H, m, 2-H), 5.98 (1 H, br d, J11,2 = ≈8.0, 11-H), 6.30–6.33 (1 H, m, 14-H). δC(150 MHz, CDCl3) 31.77 and 31.78 (2d, C-1, C-3), 52.85 (d, C-2), 31.96 and 31.97 (2t, C-4, C-9), 27.00 and 27.13 (2d, C-5, C-7), 37.42 (t, C-6), 36.98 (t, C-8, C-10), 166.21 (s, C-12), 144.27 (s, C-13), 127.93 (d, C-14), 31.52 (t, C-15), 40.37 (d, C-16), 37.69 (s, C-17), 42.01 (d, C-18), 31.32 (t, C-19), 25.90 (q, C-20), 20.85 (q, C-21). m/z 299.2242 (M+ C20H29O1N1+, calc. 299.2244).

N-(Adamantan-1-yl)-1-((1S,4R)-7.7-dimethyl-2-oxobicyclo[2.2.1]heptan-1-yl)methanesulfonamide 63a

Yield 50%. [α]25D = +26 (c 0.86 in MeOH). δH(600 MHz, CDCl3) 0.88 (3 H, s, 21-Me), 1.02 (3 H, s, 22-Me), 1.40 (1 H, ddd, 2J = 12.5, J18endo,19endo = 9.4, J18endo,19exo = 4.0, 18-Hendo), 1.61–1.65 (6 H, m, 4-2H, 6-2H, 10-2H), 1.84 (1 H, ddd, 2J = 14.3, J19endo,18endo = 9.4, J19endo,18exo = 4.8, 19-Hendo), 1.90 (1 H, d, 2J = 18.6, 16-Hendo), 1.94–2.04 (7 H, m, 2-2H, 8-2H, 9-2H, 18-Hexo), 2.05–2.10 (4 H, m, 3-H, 5-H, 7-H, 17-H), 2.30 (1 H, ddd, 2J = 14.3, J19exo,18exo = 11.7, J19exo,18endo = 4.0, 19-Hexo), 2.37 (1 H, ddd, 2J = 18.6, J16exo,17 = 4.8, J16exo,18exo = 3.2, 16Hexo), 2.98 (1 H, d, 2J = 15.0, 13-H), 3.46 (1 H, d, 2J = 15.0, 13-H′), 4.99 (1 H, br s, NH). δC(150 MHz, CDCl3) 55.24 (s, C-1), 43.03 (t, C-2, C-8, C-9), 29.51 (d, C-3, C-5, C-7), 35.85 (t, C-4, C-6, C-10), 54.31 (t, C-13), 59.20 (s, C-14), 216.61 (s, C-15), 42.77 (t, C-16), 42.62 (d, C-17), 26.87 (t, C-18), 26.09 (t, C-19), 48.33 (s, C-20), 19.79 (q, C-21), 19.59 (q, C-22). m/z 365.2023 (M+ C20H31O3N1S1+, calc. 365.2019).

N-(Adamantan-2-yl)-1-((1S,4R)-7.7-dimethyl-2-oxobicyclo[2.2.1]heptan-1-yl)methanesulfonamide 63b

Yield 34%. [α]25D = +24 (c 2.30 in MeOH). δH(600 MHz, CDCl3) 0.88 (3 H, s, 21-Me), 1.01 (3 H, s, 22-Me), 1.39–1.45 (1 H, m, 18-Hendo), 1.57–1.62 (2 H, br d, 2J = 12.8, 4-H, 9-H), 1.71 (2 H, br s, 6-2H), 2.11 (1 H, dd, J17,16exo = 4.7, J17,18exo = 4.3, 17-H), 2.18–2.24 (1 H, m, 19-Hexo), 2.38 (1 H, ddd, 2J = 18.5, J16exo,17 = 4.7, J16exo,18exo = 3.2, 16-Hexo), 2.96 (1 H, d, 2J = 15.0, 13-H), 3.35 (1 H, d, 2J = 15.0, 13-H′), 3.63 (1 H, br s, 2-H), 5.65 (1 H, br s, NH), 1.76–2.05 (13 H, m, signals of unmentioned protons). δC(150 MHz, CDCl3) 32.84 and 33.52 (2d, C-1, C-3), 58.14 (d, C-2), 31.16 and 31.24 (2t, C-4, C-9), 26.93 and 26.80 (2d, C-5, C-7), 37.34 (t, C-6), 37.07 and 37.30 (2t, C-8, C-10), 51.57 (t, C-13), 59.36 (s, C-14), 216.77 (s, C-15), 42.84 (t, C-16), 42.69 (d, C-17), 26.91 (t, C-18), 26.76 (t, C-19), 48.57 (s, C-20), 19.82 (q, C-21), 19.46 (q, C-22). m/z 365.2015 (M+ C20H31O3N1S1+, calc. 365.2019).

Biology

The vaccinia virus (strain Copenhagen), cowpox virus (strain Grishak), mousepox virus – ectromelia (strain K-1), obtained from the State collection of pathogens of viral infections and rickettsioses of the SRC VB Vector (Koltsovo, Novosibirsk region, Russia) were used in this work. Viruses were produced in Vero cell culture in DMEM medium (BioloT, Russia). The concentration of viruses in the culture fluid was determined by the method of plaques by titration of the samples in Vero cell culture, calculated and expressed in decimal logarithms of plaque-forming units per ml (log10 PFU per ml).43 The concentration of the virus in the samples used in this work was from 5.6 to 6.1 log10 PFU per ml. The used series of viruses with the indicated titer was stored at –70 °C.

The antiviral activity of compounds against orthopoxviruses was determined in vitro in Vero cell culture. The Vero cell monolayer was grown in DMEM (BioloT, Russia) in the presence of 5% fetal bovine serum (HyClone, USA) with the addition of gentamicin sulfate (40 units per ml) and amphotericin B (2.5 units per ml) The same medium was used as a support for the cultivation of cells with the virus, but with the addition of 2% serum.

Evaluation of antiviral efficacy of the compounds was carried out according to an adapted and modified method.25 To assess the effectiveness of each sample 8 three-fold dilutions were used. The initial concentration of each compound was 1, 10 or 100 μg ml–1, depending on the preliminary screening of the antiviral activity and toxicity of the drug. For evaluating the antiviral activity firstly to the wells of 96-well plates with a monolayer of cells containing 100 μl of DMEM medium with 2% fetal serum a 50 μl dilution of the samples was added, and then 50 μl of a 1000 PFU per well virus dose was added. Evaluation of the antiviral activity was performed after 4 days. After incubation of the cell monolayers infected with orthopoxvirus and treated with the tested compounds for 4 days, a vital dye “neutral red” was added to the culture medium for 1.5 hours. Next, the monolayer was washed twice with saline solution, the lysis buffer was added and after 30 min the optical density (OD), which is an indicator of the number of cells in the monolayer that is not destroyed in the presence of the virus, was measured on an Emax plate reader (Molecular Devices, USA). The OD values were used to calculate a 50% cytotoxic concentration (CC50 μM) and a 50% virus inhibiting concentration (IC50 μM) using the SoftMax Pro-4.0 computer program. Based on these indicators, the selectivity index (SI) was calculated: SI = CC50/IC50.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The synthesis of the target compounds was carried out under the state assignment of NIOCH SB RAS. The authors would like to acknowledge the Multi-Access Chemical Research Center SB RAS for spectral and analytical measurements. The study of the antiviral activity of chemical compounds was carried out under the state assignment of the State Research Centre of Virology and Biotechnology VECTOR.

Footnotes

†Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available. See DOI: 10.1039/d0md00108b

References

- World Health Organization https://www.who.int/csr/resources/publications/smallpox/synthetic-biology-technology-smallpox/en/ (accessed February 2020).

- Noyce R., Lederman S., Evans D. PLoS One. 2018;13:1. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0188453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen E., Kantele A., Koopmans M., Asogun D., Yinka-Ogunleye A., Ihekweazu C., Zumla A. Infect. Dis. Clin. North Am. 2019;33:1027. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2019.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giulio D., Eckburg P. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2004;4:15. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(03)00856-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen E., Abubakar I., Ihekweazu C., Heymann D., Ntoumi F., Blumberg L., Asogun D., Mukonka V., Lule S., Bates B., Honeyborne I., Mfinanga S., Mwaba P., Dar O., Vairo F., Mukhtar M., Kock R., McHugh T., Ippolito G., Zumla A. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2018;78:78. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2018.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration, https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm613496.htm, (accessed July 2018).

- Jordan R., Leeds J., Tyavanagimatt S., Hruby D. Viruses. 2010;2:2409. doi: 10.3390/v2112409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazurkov O., Kabanov A., Shishkina L., Sergeev A., Skarnovich M., Bormotov N., Skarnovich M., Ovchinnikova A., Titova K., Galahova D., Bulychev L., Sergeev A., Taranov O., Selivanov B., Tikhonov A., Zavjalov E., Agafonov A., Sergeev A. J. Gen. Virol. 2016;97:1229. doi: 10.1099/jgv.0.000422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoy S. Drugs. 2018;78:1377. doi: 10.1007/s40265-018-0967-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/70508/WHO_HSE_GAR_BDP_2010.3_eng.pdf?seq.uence=1 (accessed February 2020).

- Parker S., Chen N., Foster S., Hartzler H., Hembrador E., Hruby D., Jordan R., Lanier R., Painter G., Painter W., Sagartz J., Schriewer J., Buller M. Antiviral Res. 2012;94:44. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2012.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/70509/WHO_HSE_GAR_BDP_2010.4_eng.pdf?seq.uence=1 (accessed February 2020).

- Wanka L., Iqbal K., Schreiner P. Chem. Rev. 2013;113:3516. doi: 10.1021/cr100264t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreutzberger A., Schröders H., Stratmann J. Arch. Pharm. 1984;317:767. doi: 10.1002/ardp.19843170907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May G., Peteri D. Arzneim. Forsch. 1973;23:718. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreutzberger A., Schröders H. Arch. Pharm. 1974;307:766. doi: 10.1002/ardp.19743071007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salakhutdinov N., Volcho K., Yarovaya O. Pure Appl. Chem. 2017;89:1105. [Google Scholar]

- Sokolova A., Yarovaya O., Baev D., Shernyukov A., Shtro A., Zarubaev V., Salakhutdinov N. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017;127:661. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2016.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokolova A., Yarovaya O., Semenova M., Shtro A., Orshanskay Y., Zarubaev V., Salakhutdinov N. MedChemComm. 2017;8:960. doi: 10.1039/c6md00657d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khomenko T., Zarubaev V., Orshanskaya I., Kadyrova R., Sannikova V., Korchagina D., Volcho K., Salakhutdinov N. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2017;27:2920. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2017.04.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilyina I., Zarubaev V., Lavrentieva I., Shtro A., Esaulkova I., Korchagina D., Borisevich S., Volcho K., Salakhutdinov N. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2018;28:2061. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2018.04.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kononova A., Sokolova A., Cheresiz S., Yarovaya O., Nikitina R., Chepurnov A., Pokrovsky A., Salakhutdinov N. MedChemComm. 2017;8:2233. doi: 10.1039/c7md00424a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokolova A., Baranova D., Yarovaya O., Baev D., Polezhaeva O., Zybkina A., Shcherbakov D., Tolstikova T., Salakhutdinov N. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2019;68:1041. [Google Scholar]

- Sokolova A., Yarovaya O., Bormotov N., Shishkina L., Salakhutdinov N. Chem. Biodiversity. 2018;15:1. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.201800153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokolova A., Yarovaya O., Bormotov N., Shishkina L., Salakhutdinov N. MedChemComm. 2018;9:1746–1753. doi: 10.1039/c8md00347e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovaleva K., Zubkov F., Bormotov N., Novikov R., Dorovatovskii P., Khrustalev V., Gatilov Y., Zarubaev V., Yarovaya O., Shishkina L., Salakhutdinov N. MedChemComm. 2018;9:2072. doi: 10.1039/c8md00442k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teplov G., Suslov E., Zarubaev V., Shtro A., Karpinskaya L., Rogachev A., Korchagina D., Volcho K., Salakhutdinov N., Kiselev O. Lett. Drug Des. Discovery. 2013;10:477. [Google Scholar]

- Akgun B., Hall D. Angew. Chem. 2016;128:3977. doi: 10.1002/anie.201510321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ardashov O., Pavlova A., Korchagina D., Volcho K., Tolstikova T., Salakhutdinov N. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2013;21:1082. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2013.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deleris G., Dunogues J., Gadras A. Tetrahedron. 1988;44:4243. [Google Scholar]

- Midland M., Kazubski A. J. Org. Chem. 1992;57:2953. [Google Scholar]

- Suthagar K., Fairbanks A. Chem. Commun. 2017;53:713. doi: 10.1039/c6cc08574a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberhauser C., Harms V., Seidel K., Schröder B., Ekramzadeh K., Beutel S., Winkler S., Lauterbach L., Dickschat J., Kirschning A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018;57:11802. doi: 10.1002/anie.201805526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen S., Roach S. Synthesis. 1994;1995:756. [Google Scholar]

- Pal D., Kara H., Ghosh S. Chem. Commun. 2018;54:928. doi: 10.1039/c7cc08302e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chepanova A., Mozhaitsev E., Munkuev A., Suslov E., Korchagina D., Zakharova O., Zakharenko A., Patel J., Ayine-Tora D., Reynisson J., Leung I., Volcho K., Salakhutdinov N., Lavrik O. Appl. Sci. 2019;9:2767. [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee A., Wu Q., Noble W. J. Org. Chem. 1994;59:3270. [Google Scholar]

- Madder A., Sebastian S., Haver D., Clercq P., Maskill H. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 2. 1997:2787. [Google Scholar]

- Molle G., Bauer P., Dubois J. J. Org. Chem. 1982;47:4120. [Google Scholar]

- Stamford A. A., Boyle C. D. and Huang Y., US Pat., 6444687B1, 2002.

- Selivanov B. A., Tikhonov A. Y., Belanov E. F., Bormotov N. I., Kabanov A. S., Mazurkov O. Yu., Serova O. A., Shishkina L. N., Agafonov A. P., Sergeev A. N. Pharm. Chem. J. 2017;51:439. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey T. R., Jordan R. and Rippin S. R., US Pat., 2004112718A2, 2004.

- Kangro H. and Mahy B., Virology Methods Manual, Academic Press, Cambridge, 1996. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.