Abstract

Quantifying alert override has been the focus of much research in health informatics, with override rate traditionally viewed as a surrogate inverse indicator for alert effectiveness. However, relying on alert override to assess computerized alerts assumes that alerts are being read and determined to be irrelevant by users. Our research suggests that this is unlikely to be the case when users are experiencing alert overload. We propose that over time, alert override becomes habitual. The override response is activated by environmental cues and repeated automatically, with limited conscious intention. In this paper we outline this new perspective on understanding alert override. We present evidence consistent with the notion of alert override as a habitual behavior and discuss implications of this novel perspective for future research on alert override, a common and persistent problem accompanying decision support system implementation.

Keywords: alert systems, CPOE, e-prescribing, habits

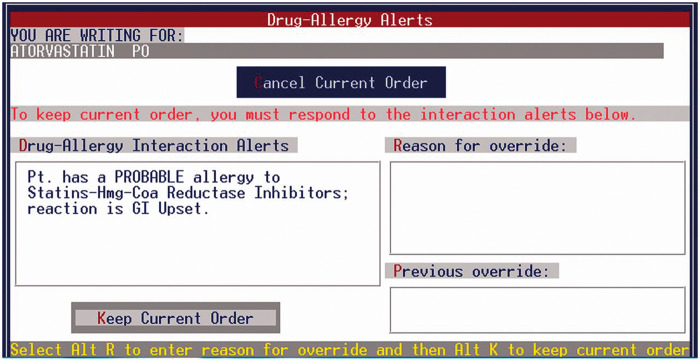

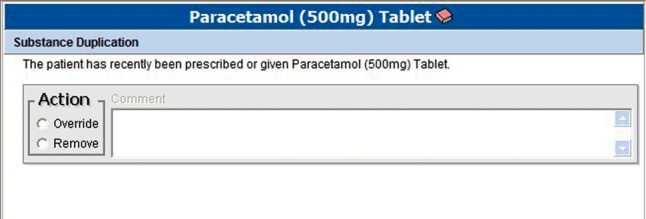

Alert or alarm overload represents a persistent problem for users, implementers, and designers in a range of industries. Offshore oil control room operators are often over-alerted about potential failures in components of the system,1 and processing plant operators experience “alarm floods,” large quantities of alarms signaling plant disturbances (eg, pressure, temperature).2 In health care, alert overload has become an increasingly significant problem as clinical information systems become more widespread and sophisticated. This is not a new problem; a 1969 report describes users becoming “frustrated” by a hospital information system’s continuous feedback.3 In this paper, we focus on alerts embedded in electronic prescribing systems (ePSs) and computerized provider order entry (CPOE) systems. These alerts are triggered at the point of prescribing and are designed to warn doctors about possible errors in orders, such as patient allergies, inappropriate dosing, or drug-drug interactions (DDIs). Alert fatigue, the mental state resulting from alert overload, is a frequent unintended consequence of clinical decision support implementation.4 Alert fatigue describes users becoming overwhelmed by and desensitized to alert presentation.5,6 A perceived consequence of alert fatigue is alert override: users move past the alert screen or box without canceling or changing an order in response to the information contained in the alert. For example, to override the alert in Figure 1, the user clicks “Override,” and in Figure 2, the user clicks “Keep Current Order.” Users are sometimes required to provide a reason for overriding an alert, by either selecting a reason from a drop-down list or entering a free-text reason, as in Figures 1 and 2. Quantifying alert override has been the focus of much research in health informatics, with studies showing that doctors override computerized alerts in ePS/CPOE up to 95% of the time.7–10

Figure 1.

An example of a drug-order duplication alert

Figure 2.

An example of a drug allergy alert

Research evaluating alert effectiveness has largely consisted of assessments of alert overrides, with override rate traditionally viewed as a surrogate inverse indicator for alert effectiveness. If an alert is frequently overridden, then it naturally follows that the alert is not providing prescribers with useful or relevant information. For example, in a study that aimed to identify noncritical DDIs that would not need to be presented to users as interruptive alerts, an analysis of alert data was performed and all DDI alerts that were overridden more than 90% of the time were presented to an expert panel for discussion as potentially of limited value.11 More recently, researchers have cautioned against using override rates as a means of assessing alert effectiveness.12,13 This is primarily because an override rate does not tell the full story about an alert’s impact on prescribing behaviors (eg, changes that are made to prescriptions long after the alert has been triggered and clicked past). In a study that used field observations and interviews with prescribers to explore prescriber-alert interactions, it was discovered that some alerts that were overridden were still useful, as they prompted prescribers to discuss information with patients.14 This positive effect would not have been captured if alert override rate had been used as the only indicator of effectiveness.

Relying on alert override rate to assess computerized alerts also assumes that alerts are being read and determined to be irrelevant by users. Our research suggests that this is unlikely to be the case when users are experiencing alert overload.15 We shadowed teams of doctors as they prescribed medications on ward rounds using an ePS and observed a very large number of alerts being triggered (approximately half the medication orders triggered one or more alerts). We noticed that prescribers not only overrode most of the alerts, but rarely read the alert content.15 If users are overriding alerts not simply based on an assessment of their relevance, then some additional driver must be at play. We suggest that over time, alert override becomes habitual; this behavior is activated by environmental cues and repeated automatically, without conscious intention.

ALERT OVERRIDE AS A HABIT

A large amount of human behavior occurs automatically, with limited awareness. Habits are “learned sequences of acts that have become automatic responses to specific cues and are functional in obtaining certain goals or end-states.”16 Habits are formed by establishing an association between an environmental cue, a response, and its consequences.17 For habits to form, the context must be stable, the behavior must be repeated frequently, and the outcome of the behavior must be reinforcing (ie, satisfying).18 In Table 1, we consider the 3 antecedents to habit formation in the context of alert override.

Table 1.

Alert override and the three antecedents to habit formation

| Required antecedents to habit formation | Relevance to alert override |

|---|---|

| Stable context | Alert override occurs on presentation of a computerized alert, which occurs when doctors are using an ePS/CPOE to prescribe medications |

| Frequent behavior | Alerts are overridden regularly and frequently |

| Positive outcome/ reinforcement | Overriding an alert allows the prescriber to proceed with the medication order and is not accompanied by an immediate negative consequence |

Although behaviors are initially carried out consciously, over time, as they are performed repeatedly, they become habitual and begin to be performed automatically. A key characteristic of habit is automaticity. Habits are performed efficiently, with limited awareness.16,19 We perform many behaviors (eg, driving a car) without being aware of making discrete decisions along the way (eg, indicating when turning). We also perform many behaviors with little mental effort, under conditions of high workload, time pressure, and information overload. Once a habit is formed, it is the context or a specific cue in the environment that activates the automated behavior. And when a habit is strong, the user is less likely to consider contextual information, less likely to search for new information, and less likely to contemplate alternative courses of action.16

We apply this notion to alert presentation and override. When a prescriber encounters an alert for the first time, he or she is likely to read the alert content and, if not relevant, override the alert to proceed with the prescription. We suggest that over time, as prescribers encounter more irrelevant or predictable alerts and override more alerts, the override response becomes habitual. When an alert is presented, it acts as a cue and automatically triggers the override response. Under conditions of alert overload, alert override is no longer driven by a conscious decision to act. The prescriber automatically overrides the alert with little attention given to the alert content or its relevance to the patient.

EVIDENCE FOR ALERT OVERRIDE AS A HABIT

The health informatics literature provides us with several interesting findings that are consistent with the idea that alert override represents a habitual response. Results from numerous studies have shown that users may not be reading alert content when a computerized alert is presented. For example, a detailed retrospective review of alerts triggered by physicians over a 4-day period at two US primary teaching hospitals showed that even highly relevant alerts (eg, exact allergy matches) were frequently overridden.8 In a study where alert content was modified to include more relevant patient information, little impact on override rates was observed, suggesting that users could potentially have not noticed this improved specificity.20 Similarly, in a study that examined nearly 15 000 overrides across 36 US primary practices, it was shown that users continued to override important and useful alerts, despite modifications to the system so that more meaningful alerts were presented.21 Overall, these findings are compatible with the theory that users may not be attending to the alert content before performing an override response.

Evidence for alerts not being read also comes from the unfortunate circumstance where a safety-critical alert is overridden and the result is a medication error and subsequent patient harm; alert fatigue is often cited as the cause.22,23

Further evidence that points to habit formation as a possible mechanism for alert override is found in studies investigating the reasons recorded by doctors for overriding an alert. Doctors are unlikely to enter an override reason into an electronic system if they are not required to do so,24,25 and when a reason is provided, it is not always useful or appropriate.8,25 A US study reviewing nearly 500 DDI alert overrides and accompanying patient charts found that although two-thirds of the overrides were considered appropriate, less than two-thirds of the reasons selected by doctors from a drop-down list (eg, “will monitor as recommended”) reflected actions that were actually carried out.21 The authors suggested that some providers were selecting reasons at random so they could proceed with the order.21

Studies investigating prescriber responses to alerts over time are lacking. In one study that examined clinician responses to clinical trial alerts in an electronic medical record, responses decreased over a 36-week exposure period (dropping 2.7% per 2-week period).6 A review of over 3 million prescriptions across 863 US practices revealed that clinicians who wrote more electronic prescriptions were more likely to override alerts than clinicians who wrote fewer prescriptions (P < .001).26 Similarly, a review of responses to best-practice alerts over a 3-year period in a health network in New York showed that for every additional 100 alerts received by a provider, the override rate increased by 1%.27 In this setting, there was also a negative association between frequency of drug alerts and alert acceptance.27 These findings collectively suggest that alert content may not be the only driver for alert override. An alternative mechanism, one that develops over time with increased exposure to alerts, may be contributing to the override response. We propose that this is habit formation.

Several strategies have been proposed and evaluated for improving alert effectiveness, such as customizing alerts for clinicians,26 increasing alert specificity,28 tiering alerts and presenting only high-level (severe) alerts to clinicians,29 and improving alert interface design.30 These strategies are not dissimilar to those adopted in other industries (eg, process industries), where alarm management has focused on reducing the number and improving the quality and clarity of alarms presented.31 These strategies are also consistent with a habit development framework, as they target one or more of the three antecedents of habit formation. Approaches that reduce the number of alerts being presented also reduce the number of times a clinician overrides an alert, thus lessening the “frequent behavior.” Strategies that make alerts more distinguishable from one another disrupt the “stable context,” and those that result in more relevant alerts being presented attenuate the “positive reinforcement.” Overriding alerts that are irrelevant is satisfying and is thus likely to foster habit formation. Overriding alerts that are highly relevant is not satisfying, as this action is likely to lead to patient harm.

IMPLICATIONS OF HABIT DEVELOPMENT AND FUTURE RESEARCH

In viewing alert override as an overlearned response, future research on alerts in ePS/CPOE should focus on examining behaviors rather than intentions. Reasoned action models, such as the theory of planned behavior,32 might not be the most useful theoretical foundations for studying and understanding user responses to alerts, particularly when users are experiencing alert overload. These theories propose that attitudes, intentions, and norms guide future behavior. Although these factors are highly relevant to habit development, once a habit is well-established, measures of past behavioral frequency are likely to contribute to the prediction of future behavior more than measures contained in these theories.16 Surveys and interviews will thus not give us useful information about alert override, as it takes place outside a user’s consciousness. Observational methods would be much more valuable.

Further research is needed to demonstrate the automaticity of alert override: the speed at which the response occurs and the user’s knowledge of the alert content. Interestingly, no research to date has systematically investigated the impact of alert rate on alert override. If alert override is a habitual response, how much exposure to the cue-response-consequence (alert-override-continue order) environment is needed before a habit is formed? To date, no association has been shown between number of alerts experienced and override rates, but this is most likely because only a small number of studies have explored this relationship.7 How do we stop users from overriding alerts once an override habit is formed? How do we get users to read and consider alert content again? Interventions aimed at changing beliefs or attitudes are unlikely to be effective in changing habitual behaviors, and lack of attention to new information makes habits very hard to break.16 Strategies that target one or more of the antecedents to habit formation (ie, frequent behavior, stable context, and positive reinforcement) are most likely to be successful.

Contribution

All authors contributed to the writing of this perspective paper.

Funding

This work was supported by National Health and Medical Research Council program grant 1054146. This funder played no role in the preparation of this perspective paper.

Competing interests

No competing interests to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1. Walker GH, Waterfield S, Thompson P. All at sea: an ergonomic analysis of oil production platform control rooms. Int J Ind Ergon 2014;44(5):723–731. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schleburg M, Christiansen L, Thornhill NF, Fay A. A combined analysis of plant connectivity and alarm logs to reduce the number of alerts in an automation system. J Process Control 2013;23(6):839–851. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gouveia W, Diamantis C, Barnett G. Computer applications in the hospital medication system. Am J Health Syst Pharm 1969;26(3):141–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ash JS, Sittig DF, Campbell EM, Guappone KP, Dykstra RH. Some Unintended Consequences of Clinical Decision Support Systems. AMIA Annual Symp Proc 2007;2007:26–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lawless ST. Time for Alert-ology or RE-sensitization? Pediatrics 2013;131(6):e1948–e1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Embi PJ, Leonard AC. Evaluating alert fatigue over time to EHR-based clinical trial alerts: findings from a randomized controlled study. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2012;19(e1):e145–e148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. van der Sijs H, Aarts J, Vulto A, Berg M. Overriding of drug safety alerts in computerized physician order entry. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2006;13(2):138–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bryant AD, Fletcher GS, Payne TH. Drug interaction alert override rates in the Meaningful Use era. No evidence of progress. Appl Clin Inform 2014;5(3):802–813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nanji KC, Slight SP, Seger DL, et al. Overrides of medication-related clinical decision support alerts in outpatients. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2014;21(3):487–491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Topaz M, Seger DL, Lai K, et al. High override rate for opioid drug-allergy interaction alerts: current trends and recommendations for future. Stud Health Technol Inform 2015;216:242–246. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Phansalkar S, van der Sijs H, Tucker AD, et al. Drug-drug interactions that should be non-interruptive in order to reduce alert fatigue in electronic health records. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2013;20(3):489–493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Payne TH, Hines LE, Chan RC, et al. Recommendations to improve the usability of drug-drug interaction clinical decision support alerts. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2015;22(6):1243–1250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. McCoy AB, Waitman LR, Lewis JB, et al. A framework for evaluating the appropriateness of clinical decision support alerts and responses. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2012;19(3):346–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Russ AL, Zillich AJ, McManus MS, Doebbeling BN, Saleem JJ. Prescribers' interactions with medication alerts at the point of prescribing: a multi-method, in situ investigation of the human-computer interaction. Int J Med Inform 2012;81(4):232–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Baysari MT, Westbrook JI, Richardson KL, Day RO. The influence of computerized decision support on prescribing during ward-rounds: are the decision-makers targeted? J Am Med Inform Assoc 2011;18:754–759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Verplanken B, Aarts H. Habit, attitude, and planned behaviour: is habit an empty construct or an interesting case of goal-directed automaticity? Eur Rev Soc Psychol 1999;10(1):101–134. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Neal D, Wood W. Automaticty in situ and in the lab: the nature of habit in daily life. In: Morsella E, Bargh J, Gollwitzer P, eds. Oxford Handbook of Human Action. New York: Oxford University Press; 2009:442–457. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Limayem M, Hirt SG, Cheung CMK. How habit limits the predictive power of intention: the case of information systems continuance. MIS Q 2007;31(4):705–737. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Verplanken B, Orbell S. Reflections on past behavior: a self-report index of habit strength1. J Appl Soc Psychol 2003;33(6):1313–1330. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Duke JD, Li X, Dexter P. Adherence to drug-drug interaction alerts in high-risk patients: a trial of context-enhanced alerting. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2013;20(3):494–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Slight SP, Seger DL, Nanji KC, et al. Are we heeding the warning signs? Examining providers' overrides of computerized drug-drug interaction alerts in primary care. PLoS One 2013;8(12):e85071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Baysari MT. Finding fault with the default alert. AHRQ WebM&M 2013. http://webmm.ahrq.gov/case.aspx?caseID=310 Accessed January 30, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Grissinger M. Medication errors involving overrides of healthcare technology. Pa Patient Saf Advis 2015;12(4):141–148. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chused AE, Kuperman GJ, Stetson P. Alert override reasons: a failure to communicate. AMIA Symposium Proceedings 2008:111–115. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Grizzle AJ, Mahmood MH, Ko Y, et al. Reasons provided by prescribers when overriding drug-drug interaction alerts. Am J Manag Care 2007;13(10):573–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Isaac T, Weissman JS, Davis RB, et al. Overrides of medication alerts in ambulatory care. Arch Intern Med 2009;169(3):305–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ancker JS, Kern LM, Edwards A, et al. How is the electronic health record being used? Use of EHR data to assess physician-level variability in technology use. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2014;21(6):1001–1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Smithburger PL, Buckley MS, Bejian S, Burenheide K, Kane-Gill SL. A critical evaluation of clinical decision support for the detection of drug-drug interactions. Expert Opin Drug Safety 2011;10(6):871–882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Paterno MD, Maviglia SM, Gorman PN, et al. Tiering drug-drug interaction alerts by severity increases compliance rates. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2009;16(1):40–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Russ AL, Zillich AJ, Melton BL, et al. Applying human factors principles to alert design increases efficiency and reduces prescribing errors in a scenario-based simulation. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2014;21(e2):e287–e296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Stauffer T. Implement an effective alarm management program. Chem Eng Progress 2012;108(7):19–27. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ajzen I. Theories of Cognitive Self-Regulation. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 1991;50(2):179–211. [Google Scholar]