Abstract

Objective: There are several user-based and expert-based usability evaluation methods that may perform differently according to the context in which they are used. The objective of this study was to compare 2 expert-based methods, heuristic evaluation (HE) and cognitive walkthrough (CW), for evaluating usability of health care information systems.

Materials and methods: Five evaluators independently evaluated a medical office management system using HE and CW. We compared the 2 methods in terms of the number of identified usability problems, their severity, and the coverage of each method.

Results: In total, 156 problems were identified using the 2 methods. HE identified a significantly higher number of problems related to the “satisfaction” attribute (P = .002). The number of problems identified using CW concerning the “learnability” attribute was significantly higher than those identified using HE (P = .005). There was no significant difference between the number of problems identified by HE, based on different usability attributes (P = .232). Results of CW showed a significant difference between the number of problems related to usability attributes (P < .0001). The average severity of problems identified using CW was significantly higher than that of HE (P < .0001).

Conclusion: This study showed that HE and CW do not differ significantly in terms of the number of usability problems identified, but they differ based on the severity of problems and the coverage of some usability attributes. The results suggest that CW would be the preferred method for evaluating systems intended for novice users and HE for users who have experience with similar systems. However, more studies are needed to support this finding.

Keywords: health information systems, heuristic evaluation, cognitive walkthrough, user-computer interface, comparison

INTRODUCTION

Many health care information systems have been developed to promote the quality of health care. Computer-based patient records is one system that can manage patient information, save clinician time, and improve safety in the health care domain.1 Because of its positive effect on patient care and the quality of outcomes, use and adoption of this system have increased over time.2–4 However, there are still some barriers to the successful interaction of users with this system and subsequently its complete adoption.

Researchers5,6 have shown that usability problems are among the significant barriers to adoption of health information technology, and they can negatively affect practitioners’ decision making, time management, and productivity.6 This can lead to user fatigue and confusion and subsequently to withdrawal or rejection of the systems. Hence, evaluation of health information systems seems to be essential in order to make user interaction more effective. Several methods exist for evaluating computer-based information systems. They can be categorized into 2 main groups: user-based and expert-based methods. Heuristic evaluation (HE) and cognitive walkthrough (CW) are 2 well-known expert-based methods that can identify a large number of problems using small amounts of financial and time resources.7,8 HE is guided by heuristic principles5 to identify user interface designs that violate these principles. CW evaluates the degree of difficulty to accomplish tasks using a system to determine the actions and goals needed to accomplish each task.9 The question now arises: which of these methods performs better in terms of identifying user interaction problems with health information systems, and what are the differences?

Based on a search by the authors, only 1 study10 used HE and CW methods synchronously in the domain of health care. The goal of this study was to develop a hybrid method, and it did not compare the performance of these 2 expert-based methods for identifying usability problems. Other comparative studies on HE and/or CW compared 1 of these 2 usability methods with usability testing methods. For example, among the studies in the field of health care, Yen and Bakken11 and Thyvalikakath et al.12 compared the HE method with user-testing methods. In another study, Khajouei et al.13 compared CW with the think-aloud method (a type of user-testing method).

Since the performance of these 2 expert-based methods (HE and CW) has not been compared in the domain of health care, the objective of this study was to compare these 2 methods to identify usability problems of health information systems. Also, given that each usability problem affects users in a different way,14 we aimed to compare the 2 methods in terms of the different types of identified usability problems.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Evaluation methods

In this study, we compared the heuristic evaluation (HE) and cognitive walkthrough (CW) methods for evaluating the usability of health information systems. Both are inspection (expert-based) methods conducted without the involvement of users.15 However, the main focus and process of applying these 2 methods are fairly different. HE is done by expert evaluators examining the design of a user interface and judging its compliance with a list of predefined principles (heuristics). These principles are used as a template, helping the evaluators to identify the potential problems users may encounter.5,16 CW is a task-oriented and structured method that focuses on the learnability of a system for new users. In this method, evaluators step through a user interface by exploring every step needed to complete a task. Meanwhile, they examine how easy it is for new users to accomplish tasks with the system. CW can be applied to study complex user interactions and goals.9,17

System

To compare the HE and CW methods, we evaluated a medical office management system, called Clinic 24, as a sample of computer-based patient records. This system was developed by Rayan Pardaz Corporation and is used in 71 medical offices throughout Iran. To facilitate the evaluation process, the system was installed on the researchers’ computer with the permission of the software provider. The system has 2 parts, secretarial (used by physicians’ secretaries) and clinical (used by physicians). Given the importance and higher relevance of the clinical part to the health care domain, the focus of this study was on this part. Physicians document the treatment process in the system by either using a light pen or selecting from predefined options in the system. In this part, physicians can document the treatment process based on the Subjective, Objective, Assessment, and Plan (SOAP) documentation method. This part provides functionality to document the chief complaint, diagnosis, and drug prescription(s) for each patient.

Participants

Since 3 to 5 evaluators are considered sufficient to perform HE and CW evaluations,5,18 5 evaluators were recruited in this study to evaluate Clinic 24. The evaluators had a background in health information technology and received theoretical and practical training about the HE and CW evaluation methods. All evaluators had a minimum of 3 years’ evaluation experience, and 3 of them had already been engaged in other domestic usability evaluation projects. They agreed to conduct the evaluation and completed informed consent forms in advance. The study was approved by the ethics committee of Kerman University of Medical Sciences (Ref. No. K/93/693).

Data collection

In HE, each evaluator examined the conformity of the user interface of Clinic 24 to Nielsen 10 heuristic principles (Table 1). Any mismatch was identified as a usability problem.

Table 1.

| Heuristic principle | Definition | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Visibility of system status | Users should be informed about what is going on with the system through appropriate feedback. |

| 2 | Match between system and the real world | The image of the system perceived by users and presentation of information on screen should match the model users have about the system. |

| 3 | User control and freedom | Users should not have the impression that they are controlled by the system. |

| 4 | Consistency and standards | Users should not have to wonder whether different words, situations, or actions mean the same thing. Design standards and conventions should be followed. |

| 5 | Error prevention | It is always better to design interfaces that prevent errors from happening in the first place. |

| 6 | Recognition rather than recall | The user should not have to remember information from one part of the system to another. |

| 7 | Flexibility and efficiency of use | Both inexperienced and experienced users should be able to customize the system, tailor frequent actions, and use shortcuts to accelerate their interaction. |

| 8 | Aesthetic and minimalist design | Any extraneous information is a distraction and a slowdown. |

| 9 | Help users recognize, diagnose, and recover from errors | Error messages should be expressed in plain language (no codes), precisely indicate the problem, and constructively suggest a solution. |

| 10 | Help and documentation | System should provide help when needed. |

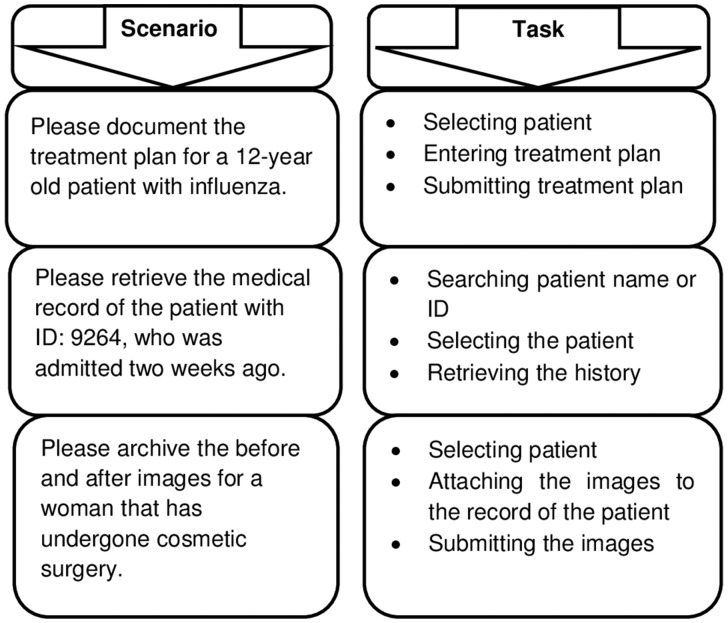

In CW the user interface of the system was evaluated based on the methodology proposed by Polson and Lewis.9 This evaluation was carried out using 10 scenarios. Each scenario consisted of a set of tasks that evaluators had to perform using the system. The scenarios were carefully designed, in consultation with several physicians and the designers of the system, to be as representative of the physicians’ daily work as possible. Figure 1 shows 3 examples of the scenarios and their corresponding tasks.

Figure 1.

Examples of scenarios and their corresponding tasks.

To perform the CW evaluation, we first determined initial user goals and subgoals based on each scenario and made an action-sequence list as described by Polson et al.9 Independent evaluators then systematically stepped through the system by examining each task, noting: (1) user goals, (2) user subgoals, (3) user actions, (4) system responses, and (5) potential user interaction problems. Each evaluator independently provided a list of usability problems with their descriptions and corresponding screenshots in a Word file. Verbal comments of evaluators were transcribed by a coordinator. Evaluators were also encouraged to write down their extra comments.

Certain parts of the system that are rarely used by physicians were not evaluated. To prevent bias, HE was done on all parts that CW was performed on (those covered by the 10 scenarios). The evaluation was done in 2 rounds. To increase the validity of the results and prevent any learning effect, we counterbalanced the order of the evaluators for each method. The first method for each evaluator was specified randomly. In the first round of the evaluation, 3 evaluators performed HE and 2 evaluators CW. After a washout period of 4 weeks, the order of the evaluators was reversed.

Analysis

The collected data from independent evaluations were reviewed and compared in joint meetings by the 5 evaluators. We held 3 formal joint meetings, each lasting approximately 3 hours with short breaks, to analyze both the HE and CW results and to categorize the identified problems. Another meeting was scheduled to summarize and calculate the average severity of the problems (45 minutes). Each meeting was coordinated by one of the authors. In the meetings, by merging identical problems identified by different evaluators, a master list of unique problems was provided for each method. Every identified problem was discussed and any disagreement was resolved by consensus. Whenever no agreement was reached, we regarded an issue as a usability problem if confirmed by at least 3 reviewers.

The master lists were distributed among evaluators, and they independently determined the severity of the problems. The problem severity was assigned based on a combination of 3 factors: frequency of problem, potential impact of problem on user, and persistence of problem every time user faces the same situation. Using these factors, evaluators rated the severity of each problem according to the Nielsen 5-scale rating as follows: 0 = not a problem at all, 1 = cosmetic problem only, 2 = minor usability problem, 3 = major usability problem, 4 = usability catastrophe.20,21 The absolute severity of each problem was determined by averaging the severity scores assigned by different evaluators to that problem.

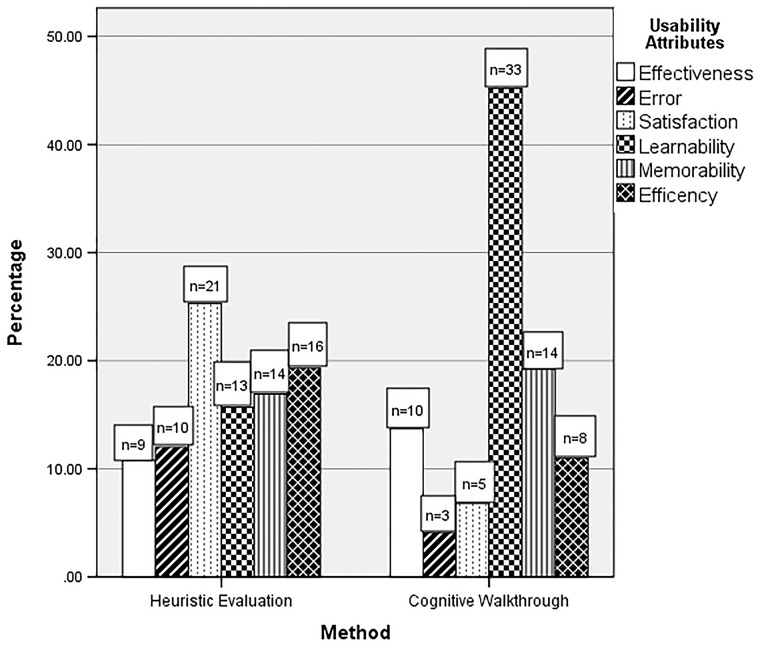

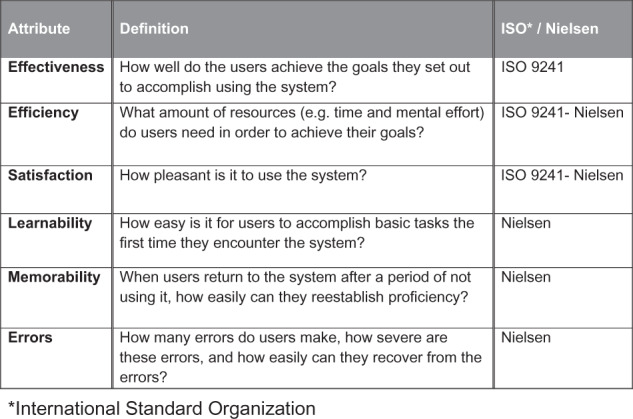

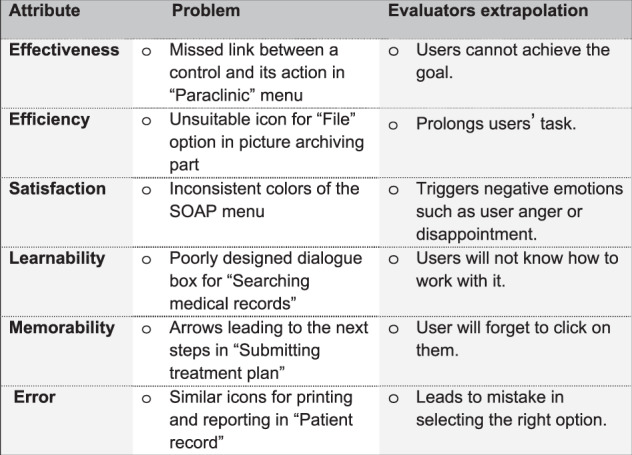

In this study, we compared the 2 methods in terms of the number of identified usability problems, the severity of problems, and the coverage of each method. To compare the coverage of the 2 usability evaluation methods, problems were categorized based on a combination of usability attributes proposed by the International Standard Organization (ISO)14 and Nielsen22 (Figure 2). In the ISO definition, effectiveness, efficiency, and satisfaction are identified as key attributes of usability.14 Nielsen also put forward 5 usability attributes: learnability, efficiency, memorability, errors, and satisfaction.22 In line with the usability attribute definitions in Figure 2, the decision to assign problems to each category was made based on analyses of the evaluator’s verbal feedback noted by the coordinator or themselves, the written descriptions of problems, and the screenshots. Examples of problems, as categorized based on the violated attributes, are shown in Figure 3. Although a specific problem may affect more than 1 usability attribute, we assigned each problem to the most appropriate attribute category by consensus.

Figure 2.

Usability attributes extracted from the ISO and Nielsen definitions14,22.

Figure 3.

Examples of problems, categorized based on the violated attributes.

Data were analyzed using SPSS (version 20, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). A Chi-square test was used to compare the number of usability problems identified by each method and the coverage of each method. Also we used Chi-square to check the potential carryover effects by comparing the number of problems identified in the 2 rounds of the evaluation per method. The mean severity of problems identified by the 2 methods was compared using a Mann-Whitney test. In this study, we used a significance level of 0.05.

RESULTS

The HE and CW methods identified 92 and 64 usability problems, respectively. Table 2 shows the number of problems identified by each method and the number of evaluators per method in the 2 rounds of evaluation. There were no significant differences between the numbers of problems identified in the 2 rounds of evaluation for each method (P > .05), indicating that the carryover learning effects were small or nonexistent.

Table 2.

Number of problems and evaluators per method in the 2 rounds of evaluation

| Round of evaluation | Heuristic evaluation |

Cognitive walkthrough |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of evaluators | No. of problems | No. of evaluators | No. of problems | |

| Round 1 | 3 | 47 | 2 | 37 |

| Round 2 | 2 | 45 | 3 | 27 |

Twenty-five out of these 156 problems were identified identically by both methods. Removing duplications between the results of the 2 evaluations left 131 unique problems. Each of the methods could identify <70% of the total unique problems. HE detected 83 problems encompassing 63% (95% confidence interval [CI], 0/55-0/7) and CW identified 73 problems encompassing 56% (95% CI, 0/47-0/64) of the total unique problems.

The number and percentage of problems identified using each of the methods in terms of usability attributes is shown in Figure 4. There was no significant difference between the number of problems identified using HE, based on the different usability attributes (P = .232). Results of CW showed a significant difference between the number of problems related to different usability attributes (P < .0001). The CW method performed notably better in identifying “learnability” problems (45% of CW results).

Figure 4.

The number of usability problems in both methods in terms of usability attributes.

Table 3 compares the 2 methods in terms of the total number of identified problems and the problems related to each usability attribute. There was no significant difference between the 2 methods based on total number of problems and problems related to the “effectiveness,” “error,” “memorability,” and “efficiency” attributes (P > .05). HE identified a significantly higher number of problems related to the “satisfaction” attribute than CW did (P = .002). The number of problems identified by CW concerning the “learnability” attribute was significantly higher than those identified by HE (P = .005).

Table 3.

Comparison of the 2 methods based on categories of problems

| Usability problems | HE* | CW** |

|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | |

| 83 (53) | 73 (47) | |

| Usability attributes | ||

| Effectiveness | 9 (47) | 10 (53) |

| Error | 10 (77) | 3 (23) |

| Satisfaction | 21 (81) | 5 (19) |

| Learnability | 13 (28) | 33 (72) |

| Memorability | 14 (50) | 14 (50) |

| Efficiency | 16 (67) | 8 (33) |

*Heuristic Evaluation.

**Cognitive Walkthrough.

Table 4 compares the severity of the problems identified by the 2 methods. The average severity of the problems identified by CW was significantly greater than that of HE.

Table 4.

Comparing severity of the problems identified by the 2 evaluation methods

| Mann-Whitney test | Median (IQR) | Mean ± SD | Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Z = −3.82 P < .0001 | 2.2 (1) | 0.58 ± 1.93 | HE |

| 2.4 (0.8) | 0.54 ± 2.32 | CW |

DISCUSSION

Principal findings

The results of this study showed no significant difference between HE and CW in terms of the total number of identified usability problems. However, these methods differ from each other in detecting problems concerning 2 usability attributes, learnability and satisfaction. They also differ based on the severity of identified problems.

To our knowledge, this is the first study comparing HE and CW for evaluating health information systems. Hence, we can discuss our results only in relation to studies evaluating information systems in other domains. Although in our study the HE method found more usability problems than CW, this difference was not statistically significant. Jeffries et al.,8 in a study comparing 4 usability evaluation methods, including HE and CW, showed that the HE method identified a significantly larger number of problems. In a study by Doubleday et al.,23 comparing HE with a user-testing method, most of the usability problems were found by the HE method. However, the results of HE depended to a large extent on the competency and expertise of evaluators.5,24–27 In this study, the same group of evaluators carried out both HE and CW, to prevent any bias on the part of the evaluators. In the previous studies,19,28 2 different groups of evaluators ran the studies, and the evaluators of HE were user interface experts.

Some studies18,29 concluded that since HE is guided by a set of principles, evaluators can freely step through the user interface to find violations without paying attention to the steps required to complete a task; hence, it can catch the problems that CW may miss. CW is led by a series of scenarios that should cover all possible actions a representative user takes to complete a task.9,30 It is therefore recommended to use an adequate number of scenarios to ensure all users’ tasks are covered. While it is not clear how comprehensive the scenarios of a CW study are, some of the previous studies may not have used a sufficient number of scenarios to cover all the users’ tasks.31,32

Strengths and weaknesses

In this study, we developed 10 scenarios in consultation with a group of physicians (end users) and developers of the system to ensure that they were representative of all users’ interactions with the system in a real setting. This may have minimized the difference between the number of problems identified by HE and CW compared to the results of previous studies. Moreover, based on our results and the results of previous studies,18,29 the design of a system can also affect the results of an evaluation study using a specific method. There are many approaches to designing information systems. One designer may follow a series of predefined principles and standards addressing issues such as layout, appearance, and consistency of interface design, while another may focus on the tasks to be accomplished by the system (user actions and system responses).33 This may somewhat affect the results of some of the compared evaluation methods. For example, in this study, HE identified many problems negatively affecting the aesthetic design of the system. These problems can be identified by CW only if they potentially impair the process of doing a task. However, more studies on a wider range of applications with more participants are required to determine the many factors affecting the results of a usability evaluation study.

Previous studies8,28 used the number and severity of identified usability problems to compare usability evaluation methods. In this study, besides these 2 criteria, we also used a combination of usability attributes proposed by ISO and Nielsen14,22 to compare the coverage of usability attributes per method.

Meaning of the study and directions for future research

Our study showed that CW found significantly more usability problems concerning the “learnability” attribute, while HE found more concerning the “satisfaction” attribute. It has also been emphasized in the relevant literature29 that, compared to other evaluation methods, CW has a stronger focus on learnability issues. Learnability is the attribute that mainly affects novice users when trying to use a system for the first time.34 Satisfaction is the attribute that mainly can be judged by users with experience with a system.35 These findings suggest that CW would be the preferred method for evaluating systems intended for novice users and HE for users with experience with similar systems. However, more studies of this type on different systems are required to confirm this finding and to determine the coverage of other attributes by each method.

In this study, the mean severity of the problems identified using CW was significantly greater than that of problems identified using HE. Consistent with our results, Jeffries et al.8 showed that CW detects more severe problems than HE. The greater severity of problems in the CW evaluation can be explained as follows. HE checks whether the design of a user interface conforms to a limited number of predefined principles without taking into account the tasks to be performed by potential users. These principles are general and may find some superficial and common problems that may not bother all users, while CW is a task-oriented method with explicit assumptions about users and their tasks. CW, therefore, can detect problems that may hinder the accomplishment of a task or affect a specific type of user. This makes CW a better choice for evaluating mission-critical systems such as health information systems.

The results of this study shed light on the potential differences between the HE and CW methods and can help evaluators of health information systems to select the appropriate methods based on their users and systems.

CONCLUSION

This study showed that HE and CW do not differ significantly in terms of the number of usability problems identified by each method. However, CW works significantly better for identifying usability problems that affect learnability of the system, and HE performs better for detecting problems that result in user dissatisfaction. Based on this, CW may be a better choice for evaluating systems designed for novice users and HE for users who have previous experience with a similar system. However, more studies of this type on a wide range of systems can support our results. Moreover, the potential of CW to identify problems of higher severity makes it suitable for evaluating mission-critical systems. The results of expert-based methods such as HE and CW are somewhat dependent on the evaluators’ expertise and the number and comprehensiveness of materials such as study scenarios.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank Rayan Pardaz Corporation for installation of the software on the researchers’ computer. We are grateful to Elnaz Movahedi, Sadriyeh Hajesmail Gohari, Zahra Karbasi, and Elham Saljooghi for their contributions to the evaluation.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

R.K. and M.Z. contributed to the conception and design of the study, acquisition and interpretation of the data, and drafting the paper. Y.J. was primarily responsible for the statistical analysis of the data. All 3 authors read and approved the final version of the article submitted.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest in this study.

REFERENCES

- 1. Erstad TL. Analyzing computer-based patient records: a review of literature. J Healthc Inform Manag. 2003;174:51–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lehmann CU, O'Connor KG, Shorte VA, Johnson TD. Use of electronic health record systems by office-based pediatricians. Pediatrics. 2015;1351:e7–e15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Xierali IM, Hsiao CJ, Puffer JC, et al. The rise of electronic health record adoption among family physicians. Ann Family Med. 2013;111:14–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hsiao C-J, Hing E. Use and Characteristics of Electronic Health Record Systems Among Office-Based Physician Practices, United States, 2001-2012. Huntsville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) Data Brief, No 111; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nielsen J. Finding usability problems through heuristic evaluation. Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. ACM 1992;1992:373–380. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Simon SR, Kaushal R, Cleary PD, et al. Correlates of electronic health record adoption in office practices: a statewide survey. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2007;141:110–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Polson P, Rieman J, Wharton C, Olson J, Kitajima M. Usability inspection methods: rationale and examples. The 8th Human Interface Symposium (HIS92). Kawasaki, Japan 1992;1992:377–384. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jeffries R, Miller JR, Wharton C, Uyeda K. User interface evaluation in the real world: a comparison of four techniques. Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. ACM 1991;1991:119–124. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Polson PG, Lewis C, Rieman J, Wharton C. Cognitive walkthroughs: a method for theory-based evaluation of user interfaces. Int J Man-machine Stud. 1992;365:741–773. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kushniruk AW, Monkman H, Tuden D, Bellwood P, Borycki EM. Integrating heuristic evaluation with cognitive walkthrough: development of a hybrid usability inspection method. Stud Health TechnolI Inform. 2014;208:221–225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yen PY, Bakken S. A comparison of usability evaluation methods: heuristic evaluation versus end-user think-aloud protocol: an example from a web-based communication tool for nurse scheduling. AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings/AMIA Symposium AMIA Symposium. 2009;2009:714–718. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Thyvalikakath TP, Monaco V, Thambuganipalle H, Schleyer T. Comparative study of heuristic evaluation and usability testing methods. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2009;143:322. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Khajouei R, Hasman A, Jaspers MW. Determination of the effectiveness of two methods for usability evaluation using a CPOE medication ordering system. Int J Med Inform. 2011;805:341–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Abran A, Khelifi A, Suryn W, Seffah A. Consolidating the ISO usability models. Proceedings of 11th International Software Quality Management Conference. Citeseer 2003;2003:23–25. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mack RL, Nielsen J. Usability Inspection Methods. New York: Wiley & Sons; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nielsen J, Molich R. Heuristic evaluation of user interfaces. Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. ACM 1990;1990:249–256. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wharton C, Rieman J, Lewis C, Polson P. The cognitive walkthrough method: a practitioner's guide. Usability Inspection Methods. Wiley & Sons 1994;1994:105–140. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nielsen J. Usability inspection methods. Conference Companion on Human Factors in Computing Systems. ACM 1995;1995:377–378. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Khajouei R, Peek N, Wierenga P, Kersten M, Jaspers MW. Effect of predefined order sets and usability problems on efficiency of computerized medication ordering. Int J Med Inform. 2010;7910:690–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nielsen J. Severity ratings for usability problems. Nielsen Norman Group; 1995. Available at: https://www.nngroup.com/articles/how-to-rate-the-severity-of-usability-problems/. Accessed June 10, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nielsen J. Usability Engineering. Boston, MA: Academic Press; 1993;102–105. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Buchanan S, Salako A. Evaluating the usability and usefulness of a digital library. Library Rev. 2009;589:638–651. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Doubleday A, Ryan M, Springett M, Sutcliffe A. A comparison of usability techniques for evaluating design. Proceedings of the 2nd Conference on Designing Interactive Systems: Processes, Practices, Methods, and Techniques. ACM 1997;1997:101–110. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Choi J, Bakken S. Web-based education for low-literate parents in Neonatal Intensive Care Unit: development of a website and heuristic evaluation and usability testing. Int J Med Inform. 2010;798:565–575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hripcsak G, Wilcox A. Reference standards, judges, and comparison subjects. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2002;91:1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Khajouei R, Ahmadian L, Jaspers MW. Methodological concerns in usability evaluation of software prototypes. J Biomed Inform. 2011;444:700–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hertzum M, Jacobsen NE. The evaluator effect: A chilling fact about usability evaluation methods. Int J Hum Comput Interact. 2003;151:183–204. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Karat C-M, Campbell R, Fiegel T. Comparison of empirical testing and walkthrough methods in user interface evaluation. Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. ACM 1992;1992:397–404. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jaspers MW. A comparison of usability methods for testing interactive health technologies: methodological aspects and empirical evidence. Int J Med Inform. 2009;785:340–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Blackmon M. Cognitive walkthrough. Encyclopedia Hum Comput Interact. 2004;2:104–107. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Karahoca A, Bayraktar E, Tatoglu E, Karahoca D. Information system design for a hospital emergency department: a usability analysis of software prototypes. J Biomed Inform. 2010;432:224–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Khajouei R, de Jongh D, Jaspers MW. Usability evaluation of a computerized physician order entry for medication ordering. MIE. 2009;2009:532–536. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Huenerfauth MP. Design approaches for developing user-interfaces accessible to illiterate users. Proceedings of the 18th National Conference on Artificial Intelligence. In Intelligent and Situation-Aware Media and Presentations Workshop (AAAI-02), Edmonton, Alberta, Canada. 2002. Available at: http://www.aaai.org/Papers/Workshops/2002/WS-02-08/WS02-08-005.pdf. Accessed June 9, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Faulkner L, Wick D. Cross-user analysis: benefits of skill level comparison in usability testing. Interact Comput. 2005;176:773–786. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lindgaard G, Dudek C. What is this evasive beast we call user satisfaction? Interact Comput. 2003;153:429–452. [Google Scholar]