Abstract

Objective: To determine the effect of availability of clinical information from an integrated electronic health record system on pregnancy outcomes at the point of care.

Materials and methods: We used provider interviews and surveys to evaluate the availability of pregnancy-related clinical information in ambulatory practices and the hospital, and applied multiple regression to determine whether greater clinical information availability is associated with improvements in pregnancy outcomes and changes in care processes. Our regression models are risk adjusted and include physician fixed effects to control for unobservable characteristics of physicians that are constant across patients and time.

Results: Making nonstress test results, blood pressure data, antenatal problem lists, and tubal sterilization requests from office records available to hospital-based providers is significantly associated with reductions in the likelihood of obstetric trauma and other adverse pregnancy outcomes. Better access to prenatal records also increases the probability of labor induction and decreases the probability of Cesarean section (C-section). Availability of lab test results and new diagnoses generated in the hospital at ambulatory offices is associated with fewer preterm births and low-birth-weight babies.

Discussion and conclusions: Increased availability of specific clinical information enables providers to deliver better care and improve outcomes, but some types of clinical data are more important than others. More available information does not always result from automated integration of electronic records, but rather from the availability of the source records. Providers depend upon information that they trust to be reliable, complete, consistent, and easily retrievable, even if this requires multiple interfaces.

Keywords: information transmission, electronic health records, mixed methods, pregnancy outcome

INTRODUCTION

Electronic health record (EHR) systems are designed to facilitate the flow of clinical information across care settings. The extent to which that information results in better clinical decision-making and improvements in health outcomes depends on both the technical quality of the system and the work processes put in place to extract maximum value from the system.1–3 While providers often believe they know what information is required to make appropriate and informed decisions, there are few objective studies on which specific pieces of clinical data are most important to the quality of care, or how the delivery of the data affects its usefulness.

We employed mixed methods to determine how well an integrated EHR system transmitted clinical information from outpatient obstetrics/gynecology (OB/GYN) offices to the inpatient labor and delivery unit, and vice versa, during pregnancy care. Using surveys at the point of care, we tracked the transmission of clinical information across care settings and interviewed providers to determine how they access the information and what barriers they face in improving access. We also used multiple regression to determine which specific pieces of clinical data had the largest effect on care processes and were the most important in reducing adverse pregnancy events. Our models are risk adjusted and rely on changes in information available to physicians over time and across patients due to the EHR implementation, in order to isolate the effect of data availability from unobservable confounding factors.

BACKGROUND AND SIGNIFICANCE

Physicians caring for patients who previously received care at other sites are particularly likely to lack complete information on examinations and test results, resulting in worse health outcomes.4–7 Bridging such gaps in information availability is a key objective of policies promoting the adoption of EHRs, and some previous studies have shown that EHRs are associated with improved flow of information.8,9 In the specific case of obstetric care, which by its very nature involves care at different sites, EHRs can improve communication and data availability.10–14 However, many studies focus on the transmission of either a single piece of clinical data or group of data (eg, discharge summaries) without measuring the separate availability of multiple data items or their efficacy in provision of care. There are inherent constraints in the design of EHR systems that limit the amount of information that can be highlighted and most reliably conveyed to providers. As a result, it is important to determine which data items have the largest impact on care provision and outcomes so that their transmission can be prioritized in EHR design. It is also important to understand how providers access EHR data, because mode of access has been shown to affect usability of data.15,16

DATA AND METHODS

Our field site is the Lehigh Valley Health Network (LVHN), which installed and integrated a new EHR in 2009–2012 to increase clinical information flow between ambulatory practices and the hospital. Physicians in the triage subunit of the labor and delivery unit evaluate expectant mothers arriving at the hospital and either formally admit or discharge them. If the latter, patients continue office appointments until a subsequent visit to triage results in admission for delivery or they are directly admitted to the hospital. Before EHR deployment, providers in triage relied on paper records sent by courier from OG/GYN offices, which were often out of date. Conversely, information concerning hospital visits was frequently unavailable at those practices.

We surveyed both triage and outpatient providers during a 3–4 month interval at 3 different points of time throughout the multiyear integration process. We asked about the availability of clinical information that LVHN physicians felt were most important for managing pregnancy cases at each location. Triage providers were asked about availability of the following information from a patient’s prenatal record: blood pressure, cervical examinations, antenatal problem list, nonstress tests, group B strep tests, prior uterine incision type(s), and, for Medicaid patients, a tubal sterilization request (Supplementary Appendix Figure A1). Office providers were asked whether they were aware that a patient had recently visited triage, how they knew this information, and whether information on cervical examinations, nonstress test results, new diagnoses, and laboratory work from a patient’s most recent visit to triage was available for review during the office visit (Supplementary Appendix Figure A2). Across all 3 survey waves, we collected 1203 surveys from triage providers and 3699 surveys from providers in OB/GYN offices. Among the latter, 377 providers reported that the patient had recently visited triage.

For each clinical data element, we created an indicator variable that equaled 1 if providers responded that the information was available for review at the appropriate location, and 0 otherwise. Depending on the nature and timing of the visits, some of this information may not have been collected, so we allowed providers to indicate whether specific data were not applicable (N/A), and created indicator variables to measure N/A status. In addition, if patients had multiple visits during the survey period, we averaged the values of the indicator variables to reflect proportions.

We also completed 76 interviews of personnel (providers and staff) at OB/GYN offices and triage at 3 different points in time. Interviews focused on workflow, facilitating conditions (eg, training, user involvement, champions), process changes, and data access, as well as attitudes toward the system and the implementation process.3

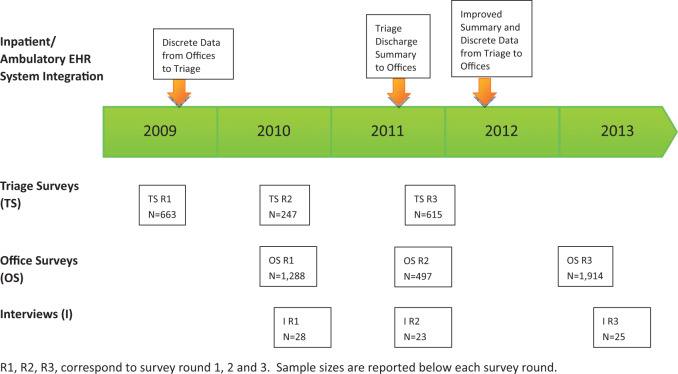

Figure 1 shows the timing of our interviews and our triage and office surveys relative to the EHR implementation timeline. By the beginning of the first round of triage surveys, the ambulatory EHR was installed in approximately half of the outpatient practices, and ambulatory EHR terminals were available in triage at the hospital. In the second half of 2009 a computer interface was installed, allowing data to move automatically from the ambulatory EHR to the inpatient EHR in triage, enabling access to prenatal histories directly within the inpatient system. By mid-2011 there was limited 2-way flow of information, with a discharge summary sent automatically from the inpatient EHR in triage to the ambulatory EHR, and additional functionality was enabled in March 2012 enabling a set of discrete clinical data elements from triage visits to directly populate specific locations in the ambulatory EHR interface.

Figure 1.

Implementation timeline.

Measures of information availability: perceived vs technical

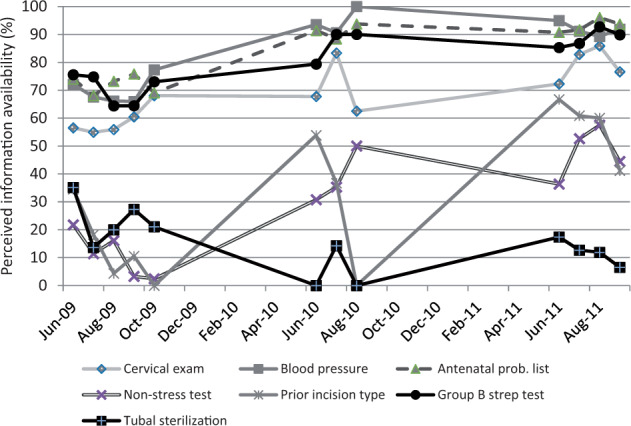

Our surveys indicate that information availability generally increased over the staged installation of the EHR system (Figure 2). However, it is important to make a distinction between actual information acquisition by providers, or perceived information availability, which we measured through our surveys, and technical information availability in the EHR system. In some cases clinical data may be contained in the EHR but providers fail to access the data, or clinical data may be absent from the EHR but providers access the data through other means. Indeed, our interviews suggest that providers in triage frequently did not obtain data from the automated user interface.

Figure 2.

Information availability on the inpatient triage subunit over time.

To investigate discrepancies between perceived and technical information availability, we conducted an audit of survey responses using data extracted directly from the inpatient and outpatient EHR systems (Table 1). We used only survey rounds 2 and 3 when evaluating the triage and office surveys, which were collected after data were flowing electronically from the other care setting. There were 4 possible scenarios where survey data elements were compared to EHR data: (1) the data element was present in the EHR and providers indicated it was available (column 1); (2) the data element was present in the EHR but providers indicated it was not available, suggesting a failure to recognize the data in the EHR user interface (column 2); (3) the data element was not in the applicable EHR interface but providers indicated it was available, suggesting they obtained it through other means (column 3); or (4) the data elements were not in the EHR and providers indicated it was not available (column 4).

Table 1.

Validation of survey responses with information in EHR

| Panel A: Inpatient EHR (I-EHR) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surveyed data elements | In I-EHR and triage survey | In I-EHR but not triage survey | In triage survey but not I-EHR | Not in I-EHR or triage survey | N |

| (1) (%) | (2) (%) | (3) (%) | (4) (%) | ||

| Cervical exam available | 60.19 | 10.19 | 21.21 | 8.40 | 726 |

| Blood pressure available | 67.49 | 2.89 | 25.76 | 3.86 | 726 |

| Nonstress test available | 9.34 | 61.02 | 3.31 | 26.31 | 726 |

| Group B strep test available | 44.28 | 26.07 | 14.48 | 15.17 | 725 |

| Tubal sterilization request available | 2.75 | 67.63 | 0.28 | 29.34 | 726 |

| Prior uterine incision type available | 7.58 | 62.81 | 2.20 | 27.41 | 726 |

| Panel B: Ambulatory EHR (A-EHR) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surveyed data elements | In A-EHR and office survey (%) | In A-EHR but not office survey (%) | In office survey but not A-EHR (%) | Not in A-EHR or office survey (%) | N |

| New diagnoses available | 22.38 | 26.19 | 7.14 | 44.29 | 210 |

| Cervical exam available | 40.81 | 11.66 | 8.07 | 39.46 | 223 |

| Nonstress test available | 41.89 | 12.16 | 4.95 | 40.99 | 222 |

| Lab test results available | 24.75 | 22.77 | 6.44 | 46.04 | 202 |

Providers frequently reported that they did not have data (eg, nonstress tests, tubal sterilization requests, and prior uterine incision types), even though these data were technically available within the inpatient EHR. And in some cases, data that did not exist in the inpatient EHR (cervical exams and blood pressure) were accessed, but not from the inpatient EHR. This is consistent with the finding from our provider interviews that they rarely used the interfaced data within the inpatient EHR, but often accessed the patient’s information directly from ambulatory EHR terminals in triage, in order to circumvent technical problems with the automated data interface. Some triage data were still unavailable in the offices, reflecting technical and process difficulties during the implementation process. Even when data were contained in the ambulatory EHR (new diagnoses, lab tests), some providers reported that they were unavailable, suggesting difficulties accessing the data through the user interface.

This audit of the triage and office survey data highlights one advantage of our study: by measuring providers’ perceptions of information availability directly rather than relying on data extracted from the EHR, we can account for alternative models of data access and providers’ difficulties in extracting data from the EHR.

Measures of pregnancy outcomes and care processes

We constructed patient-level measures of pregnancy and birth outcomes from LVHN medical billing databases and from chart review, and merged these with our triage and office survey records. From the billing database we constructed indicators of whether: (1) there was obstetric trauma during the birth, (2) the birth took place before 37 weeks gestation (preterm birth), and (3) the baby had low birth weight (<2500 g). From chart review we constructed a measure of adverse outcomes (AOs) based on 10 preidentified adverse events. Each adverse event was weighted to reflect its severity, and these numbers were then summed across mother and baby(ies) to calculate a weighted AO score (Supplementary Appendix Table A1).17,18 We also examined the impact of changes in the availability of data on 2 processes of care derived from billing databases, whether the birth was medically induced and whether it was by C-section.

Specifications

We used multiple regression to determine whether greater clinical information availability, as measured by the indicator variables constructed from responses to our triage and office surveys, was associated with improvements in pregnancy outcomes and changes in care processes. We estimated linear probability models for most outcomes, but because the distribution of the AO score is right-skewed with a mass point at zero, we analyzed it using 2 separate regressions: a linear probability model for whether the individual experienced an adverse outcome and an ordinary least squares regression of the ln(adverse outcome score) on the sample of observations where the score > 0.

We regressed our measures of information availability on different outcome measures depending on whether they were collected at the triage subunit in the hospital or the OB/GYN offices. In particular, we correlated the indicator for obstetric trauma and the AO score to measures of information availability at triage, because these outcomes are affected by clinical decision-making during delivery, while we correlated indicators of preterm birth and low birth weight to measures of information availability at the OB/GYN offices, because these outcomes are sensitive to prenatal care. Although we regressed our 2 process measures (labor induction and C-section) on measures of information availability collected in both settings, we present only the models that use triage data, because there were no statistically significant results from models using data from the OB/GYN offices.

All specifications include fixed effects for the delivering physician, to control for time-invariant attributes of physicians (such as practice style) that might otherwise confound the estimates. We also controlled for variation in individual patient characteristics and the baseline risk of adverse birth outcomes, using the mother’s age group (5-year categories from age 11 through age 45), race (white, black, Hispanic, other), insurance status (commercial, Medicare, Medicaid, Medicaid managed care), and admission type (elective, emergency, urgent); whether she had 1 of several preexisting conditions, nonpreventable birth complications, a previous C-section, and multiple birth delivery; and indicator variables for her quartile in the patient risk distribution based on diagnostic cost group/hierarchical coexisting conditions (DCG/HCC) patient risk scores.19,20 The complete list of preexisting conditions and nonpreventable birth complications is shown in Supplementary Appendix Table A2. In models of obstetric trauma and the AO score, we also controlled for delivery type (vaginal delivery without instruments, vaginal delivery with instruments, or C-section).

We include indicators for survey year and whether the clinical information measured in our triage and office surveys was contained in the inpatient or ambulatory EHR system at the time of survey (irrespective of whether it was recognized by providers). Inclusion of the latter is meant to ensure that we captured the effect of changes in providers’ perceptions of information availability, not whether the information was or was not contained in the system. For the inpatient EHR, our electronic audit revealed that the clinical data elements contained in the triage survey were either all missing or all available, so we include just 1 control variable for information availability. In the ambulatory EHR, information availability varied across clinical data elements, so we created indicators for each of the 4 types of clinical data elements.

Our models of obstetric trauma, AO score, labor induction, and C-section are based on the full sample of 1203 patients represented in our 3 triage survey rounds, because nearly all of these patients had a prenatal record. However, in our office surveys, providers were only asked to report whether clinical data from a triage visit was available if they knew the patient had such a visit. As a result, our models of preterm birth and low birth weight are based on the subset of 377 patients whom providers reported had a triage visit. As a sensitivity test, we also estimated using the larger set of 773 patients whom providers indicated had a triage visit or they did not know whether the patient had a triage visit. Descriptive statistics from our 2 main samples are reported in Table 2, and descriptive statistics for control variables are included in Supplementary Appendix Table A3. For all estimations, we clustered the standard errors at the delivering physician level.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics for key dependent and independent variables

| Variables | Triage survey sample (N = 1203) | OB/GYN office survey sample (N = 377) |

|---|---|---|

| Mean (Std Dev) | Mean (Std Dev) | |

| Birth outcomes and care processes | ||

| Obstetric trauma | 6.5% (24.6) | – |

| Proportion adverse outcome score > 0 | 7.6% (26.5) | – |

| Log adverse outcome score (if score > 0)a | 3.094 (88.2) | – |

| Labor induction | 55.3% (49.7) | – |

| C-section | 30.8% (46.2) | – |

| Preterm birthb | – | 7.3% (26.1) |

| Low birth weightb | – | 6.2% (24.2) |

| Data elements in triage survey (N = 1203) | ||

| Cervical exam available | 71.2% (43.9) | – |

| Cervical exam not available | 26.2% (42.4) | – |

| Blood pressure available | 84.1% (35.3) | – |

| Blood pressure not available | 13.2% (32.6) | – |

| Antenatal problem list available | 84.8% (34.8) | – |

| Antenatal problem list not available | 12.5% (31.9) | – |

| Nonstress test available | 9.5% (28.2) | – |

| Nonstress test not available | 27.0% (42.6) | – |

| Nonstress test N/A | 60.7% (47.1) | – |

| Prior uterine incision type available | 6.6% (24.2) | – |

| Prior uterine incision type not available | 8.3% (26.9) | – |

| Prior uterine incision type N/A | 82.6% (37.4) | – |

| Group B strep test available | 53.3% (48.1) | – |

| Group B strep test not available | 8.5% (27.1) | – |

| Group B strep test N/A | 35.1% (45.9) | – |

| Tubal sterilization request available | 3.5% (17.7) | – |

| Tubal sterilization request not available | 14.4% (33.7) | – |

| Tubal sterilization request N/A | 78.6% (39.7) | – |

| Any data element missing | 4.3% (19.5) | |

| Data elements in OB/GYN office survey (N = 377) | ||

| New diagnoses available | – | 23.4% (40.6) |

| New diagnoses not available | – | 51.2% (47.7) |

| New diagnoses N/A | – | 12.6% (31.5) |

| Cervical exam available | – | 30.9% (44.8) |

| Cervical exam not available | – | 48.0% (48.5) |

| Cervical exam N/A | – | 8.1% (25.8) |

| Nonstress test available | – | 27.9% (43.6) |

| Nonstress test not available | – | 51.5% (48.9) |

| Nonstress test N/A | – | 7.8% (25.9) |

| Lab tests available | – | 17.7% (36.5) |

| Lab tests not available | – | 54.4% (48.1) |

| Lab tests N/A | – | 14.1% (33.6) |

| Patient visited triagec | – | 13.2% (33.9) |

| Patient did not visit triagec | – | 73.8% (44.1) |

| Do not know whether patient visited triagec | – | 13.2% (33.9) |

| Knew patient visited triage from EHR | – | 22.4% (40.5) |

| Told by patient she visited triage | – | 12.7% (32.1) |

| Knew patient visited triage for other reasond | – | 26.0% (42.6) |

| Any data element missing | 14.8% (34.0) | |

| Inpatient EHR information availability controls | ||

| All data elements present in EHR | 66.4% (46.3) | – |

| Outpatient EHR information availability controls | ||

| New diagnoses present in EHR | – | 25.7% (43.0) |

| Cervical exam present in EHR | – | 29.8% (45.2) |

| Nonstress test present in EHR | – | 31.2% (46.0) |

| Lab tests results present in EHR | – | 24.3% (42.3) |

aBased on 91 observations with positive AO score; reported in the log scale. bBased on 369 observations. cBased on the full sample of 3699 office surveys. dOther reasons provider knew patient visited triage included provider asked patient, provider saw patient on triage, reason undetermined.

ESTIMATION RESULTS

Tables 3 and 4 contain our estimation results. All specifications include physician fixed effects as well as controls for survey year and the technical availability of the clinical data. Consequently, the estimates reflect the marginal impact of actual data availability as perceived by providers on outcomes and care processes.

Table 3.

Impact of availability of information from office prenatal records to providers in triage on birth outcomes and processes

| Panel A | Obstetric trauma |

AO score > 0 |

Log (AO score) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surveyed data elements | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) |

| Cervical exam available | −2.0 | −2.6 | 0.1 | −1.8 | −46.7 | −37.0 |

| (2.1) | (2.5) | (2.0) | (2.5) | (43.0) | (63.5) | |

| Blood pressure available | −1.6 | 0.6 | 2.2 | 3.1 | −108.0*** | −42.5 |

| (2.3) | (2.6) | (2.3) | (3.1) | (38.4) | (80.9) | |

| Antenatal problem list available | 0.5 | 1.4 | 2.0 | 1.2 | −59.4* | −82.2* |

| (2.8) | (2.8) | (2.7) | (3.3) | (34.5) | (46.8) | |

| Nonstress test available | −6.6* | −7.1* | −0.3 | −0.2 | −14.0 | −48.9 |

| (3.3) | (3.7) | (2.8) | (2.8) | (45.8) | (55.9) | |

| Prior uterine incision type available | 4.9 | 6.2 | −2.2 | −3.0 | −24.7 | −62.7 |

| (3.9) | (4.2) | (3.4) | (3.4) | (82.5) | (77.8) | |

| Group B strep test available | 0.7 | 1.5 | 0.4 | −0.6 | −11.0 | −51.5 |

| (3.1) | (3.0) | (3.0) | (3.2) | (56.1) | (57.5) | |

| Tubal sterilization request available | −5.1 | -4.8 | −4.1* | −4.1 | −61.8 | −83.7 |

| (3.1) | (3.3) | (2.4) | (2.5) | (121.7) | (161.2) | |

| Mean of outcome variable | 6.5 | 7.6 | − | |||

| N | 1203 | 1203 | 1203 | 1203 | 91 | 91 |

| R2 | 0.068 | 0.027 | 0.614 | |||

| Panel B | Labor induction |

C-section |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surveyed data elements | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

| Cervical exam available | 6.5* | 6.0 | −7.0*** | −1.3 |

| (3.2) | (4.6) | (2.6) | (3.3) | |

| Blood pressure available | 2.3 | −4.1 | −11.3*** | −6.4 |

| (4.5) | (6.3) | (4.2) | (4.4) | |

| Antenatal problem list available | 6.0 | 5.1 | −9.3* | −3.1 |

| (3.8) | (4.2) | (4.6) | (4.6) | |

| Nonstress test available | 7.6 | 7.1 | 5.8 | 8.7* |

| (5.6) | (5.5) | (4.6) | (4.6) | |

| Prior uterine incision type available | 5.5 | 4.3 | −5.7 | −5.3 |

| (7.6) | (7.3) | (8.5) | (8.6) | |

| Group B strep test available | 9.3** | 6.5 | −16.8*** | −14.2** |

| (4.3) | (4.4) | (5.1) | (5.4) | |

| Tubal sterilization request available | −8.2 | −10.3 | −5.6 | −6.5 |

| (8.2) | (8.6) | (6.8) | (7.3) | |

| Mean of process variable | 55.3 | 30.8 | ||

| N | 1203 | 1203 | 1203 | 1203 |

| R2 | 0.195 | 0.375 | ||

***P < .01, **P < .05, *P < .1. Standard errors, reported in parentheses, are cluster-corrected at the delivering physician level.

Table 4.

Impact of availability of information from triage visits to providers in OB/GYN offices on birth outcomes

| Panel A: Provider knew patient visited triage | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surveyed data elements | Preterm birth |

Low birth weight |

||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| New diagnoses available | 0.7 | 2.1 | −3.9*** | −3.0* |

| (2.3) | (3.3) | (1.3) | (1.6) | |

| Cervical exam available | −5.1 | −4.5 | −5.4 | −3.3 |

| (4.2) | (3.7) | (3.4) | (3.1) | |

| Nonstress test available | −3.1 | 0.7 | −4.0 | −0.6 |

| (5.5) | (5.7) | (3.4) | (3.2) | |

| Lab test results available | −3.7 | −3.3 | −3.8 | −1.5 |

| (3.1) | (5.0) | (2.5) | (2.9) | |

| Mean of outcome variable | 7.3 | 6.2 | ||

| N | 369 | 369 | 369 | 369 |

| R2 | 0.261 | 0.272 | ||

| Panel B: Provider did not always know whether patient visited triage | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surveyed data elements | Preterm birth |

Low birth weight |

||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| New diagnoses available | −1.0 | 0.9 | −5.2*** | −4.0** |

| (2.8) | (3.6) | (1.8) | (1.5) | |

| Cervical exam available | −3.9 | −2.3 | −4.1* | −0.9 |

| (3.2) | (2.9) | (2.3) | (2.3) | |

| Nonstress test available | −3.3 | 0.4 | −3.9 | −1.0 |

| (4.5) | (5.3) | (2.8) | (3.7) | |

| Lab test results available | −5.5** | −5.2 | −5.2** | −2.8 |

| (2.6) | (4.2) | (2.2) | (2.4) | |

| Mean of outcome variable | 6.1 | 4.7 | ||

| N | 773 | 773 | 773 | 773 |

| R2 | 0.260 | 0.208 | ||

Notes: ***P < .01, **P < .05, *P < .1. Standard errors, reported in parentheses, are cluster-corrected at the delivering physician level.

Table 3 contains estimates of the effect of better availability of data from the inpatient EHR in triage on birth outcomes (panel A) and care processes (panel B). Each entry is the coefficient estimate from the regression model multiplied by 100, to reflect the percentage point effect in the linear probability models and the approximate percentage effect in the log-linear model (the exact percentage effect is calculated as 100•[exp(coefficient) − 1]). We report 2 columns of estimates for each outcome measure: those in the rightmost column correspond to a single regression where availability indicators for each clinical data element are entered into the regression jointly (ie, the saturated model); those in the leftmost column correspond to 7 separate regressions in which the outcome was regressed on each data availability indicator separately with the control variables. We estimated these 2 sets of models in order to determine whether multicollinearity across the indicator variables was responsible for reducing the precision of the estimated coefficients in the saturated model. If the estimated effects are similar across the 2 sets of models but the standard errors in the rightmost column are larger, this is likely the case.

We find that availability in triage of nonstress test results from the patient’s prenatal record is significantly associated with a reduction in the likelihood of obstetric trauma. This effect is robust to model specification and large in magnitude, associated with a 7 percentage point reduction in obstetric trauma, which is just over 100% of the mean level of obstetric trauma in our estimation sample (ie, (7/6.5) × 100 = 108%).

Information on tubal sterilization requests for Medicaid patients was associated with a 4 percentage point ((4.1/7.6) × 100 = 54% relative to the mean) reduction in the probability of an adverse pregnancy event, as measured by AO score. Finally, availability of blood pressure information and antenatal problem list was associated with a 66% and 45–56% reduction, respectively, in the magnitude of the AO score, although the effect of blood pressure information was not precisely estimated in the saturated model in column 6. (Due to limitations in statistical power, we were not able to determine which specific components of the AO score are most sensitive to this information.)

The estimates reported in panel B show that information on cervical exam results and group B strep test results was associated with a higher probability of labor induction in the model reported in column 1, although neither was statistically significant in the saturated model in column 2. Availability of cervical exam results, blood pressure, antenatal problem list, and group B strep test was associated with a lower likelihood of performing a C-section, while availability of nonstress test results was positively associated with C-section rates in the saturated model. For both inductions and C-sections, availability of the group B strep test was most strongly associated with use of these procedures, impacting their likelihood by 7–17 percentage points ((6.5/55.3) × 100 = 12% and (16.8/30.8) × 100 = 55% relative to the mean, respectively).

In Table 4 we report the impact of availability at the practices of clinical information from a patient’s most recent visit to triage on the outcome of her pregnancy. Panel A contains our main results, which are based on patients for whom providers knew that a triage visit occurred. We control for whether each clinical data element was N/A for the given triage visit, so the reported coefficients measure the impact of information availability relative to the case where the information from the triage visit was not available. In panel B we report the estimates from models that include patients for whom providers did not know whether they had a recent triage visit. In this case, the control group is heterogeneous (in some cases patients may have visited triage, but their data were not transmitted to the ambulatory EHR), but the larger sample provides more statistical power.

For preterm birth, none of the information availability indicators are precisely estimated in panel A, but in panel B availability at the practices of the results from lab tests performed in triage was associated with a 6 percentage point reduction in the probability of preterm birth. Availability of new diagnoses was significantly associated with a reduced probability of low birth weight, even in the small sample reported in panel A; the results in panel B indicate that cervical exam results and lab test results may also have improved outcomes. These effects were relatively large, ranging from 48 to 111% of the overall sample mean, depending on the measure and specification.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

We estimated the impact of the perceived availability of specific data elements on patient outcomes and care processes, controlling for physician fixed effects as well as survey year and technical availability of the data. Although including physician fixed effects allowed us to account for unobservable time-invariant attributes of physicians, it may also have contributed to low statistical precision, because only variation within physicians over time was used to identify the effects. In order to investigate this possibility, we re-estimated all models without physician fixed effects and report the results in Supplementary Appendix Tables A4 and A5. While the magnitudes of the estimated effects are similar, the precision of estimates in the preterm-birth and low-birth-weight models generally improves.

Overall, our results suggest that availability of nonstress test results from the prenatal record for providers in triage was associated with a significant reduction in the likelihood of obstetric trauma, while blood pressure and problem list data were associated with a large reduction in the adverse outcomes score. Each of these clinical data elements is important in the prevention of adverse birth outcomes. For example, if repeated nonstress testing indicates a nonreassuring fetal heart rate, action is sometimes taken to expedite delivery through medical induction of labor or C-section. Likewise, a trending increase in blood pressure readings might cause physicians to expedite delivery. Being able to observe trends in these data over time through the prenatal record may explain why their availability affects outcomes. We note that the only clinical data element that was not significantly associated with any outcome or process measure, prior uterine incision type, is constant throughout pregnancy.

We also find that greater data availability in triage is associated with a higher rate of medical induction of labor, which suggests that the additional information sometimes prompts providers to place patients in a higher risk category. This may help providers more closely monitor patient health and intervene earlier in higher risk cases, thereby reducing the need for C-section (later intervention after the risk has increased could limit the scope for medical induction, exposing the fetus to a potentially unhealthy intrauterine environment and necessitating C-section to expedite delivery). This conclusion is supported by our interview results. Despite the fact that providers in triage often relied on 2 separate user interfaces to access clinical information, and sometimes could not easily retrieve the information, they felt that information availability improved relative to the period prior to installation of the new EHR system. Moreover, the physicians confirmed that this improved quality of care. Data on the negative association of tubal sterilization requests by Medicaid patients with adverse outcomes is less direct. Failing to have this form online results in the need to perform tubal ligation as an additional procedure at some date after the delivery. It is possible that for some patients expecting to receive a tubal ligation, efforts were made to obtain the form during labor, which distracted from provision of care. Unfortunately, we cannot identify the mechanism for this association in our data, so we leave this for future work.

We find that more information from triage visits in OB/GYN offices is also associated with improved pregnancy outcomes, particularly a reduced likelihood of low birth weight. Triage visits often occur toward the end of pregnancy, close to full term. More readily available information may improve physicians’ ability to monitor patients with complications in the outpatient setting, thus helping to bring those patients to full term before delivery, thereby reducing the prevalence of preterm births and low-birth-weight babies.

Although we find that increased availability of specific clinical information improved birth outcomes, our interviews revealed that this was not always due to direct integration of the inpatient and ambulatory EHR systems. In particular, providers often accessed the ambulatory EHR directly via the terminals installed in triage, because automatically interfaced data was sometimes missing.3 In addition, providers needed to adjust their work processes before they could make use of new data.3,20

Accessing information from the ambulatory EHR rather than the inpatient EHR suggests that providers depend upon information that they trust, ie, that is perceived to be the most reliable, complete, and consistent. More familiar and complete sources of information may be preferred to more efficient but potentially incomplete or unfamiliar sources as perceived by users, even if it requires accessing 2 separate systems. Providers’ lack of trust in certain data may help explain why some data elements had no significant impact.3

Finally, while information may be more available within a system, it must also be easily retrieved to be useful to providers. That some office providers reported missing information which was in fact within the EHR system suggests that some of them had difficulty finding information within the system. This highlights the need for EHR systems to incorporate predictive capabilities to understand exactly what information is needed and when, and then provide it to clinicians within standard workflow interactions.

The hospital and OB/GYN offices in this study are part of a closely integrated network, which could limit the generalizability of our results. In particular, the impact of information availability on outcomes could be more limited in settings with fewer incentives to coordinate care. Another limitation is that the variation in information availability over our analysis period was not generated through a randomized experiment, but through the staged implementation of an EHR. In order to address the concern that the implementation implicitly targeted high-risk groups, we included numerous controls for patient illness severity, including patient demographic and insurance information, as well as patient-level DCG/HCC risk score quartile controls. We also included physician fixed effects to control for unobserved physician skill and effort. Nonetheless, future work using experimental methods is needed to demonstrate that the associations we find represent causal effects.

Our study shows that the information transmitted through EHR systems directly impacts health outcomes and care processes in pregnancy care, although some types of information are more important than others. Automated integration alone is insufficient for improving the quality of care, but greater information availability during the perinatal continuum of care does lead to improved birth outcomes, even if disparate EHR systems are used for information transmission.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Jeffrey McFetridge for research assistance, and the physicians and staff members of the Lehigh Valley Health Network who took time to share their thoughts about and experience with the new information systems.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality under grant PARA-08-270.

COMPETITING INTERESTS

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

CONTRIBUTORS

CM, DL, SS, MD, SC, MS, and MN made significant contributions to the conception and design of the study. CM, DL, MS, and MN collected the data, and CM, LP, and TH conducted the quantitative analysis. SS conducted the qualitative analysis. All authors contributed to either the drafting or revision of the article and approved the article for publication.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary material is available at Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association online.

REFERENCES

- 1. Silow-Carroll S, Edwards J, Rodin D. Using electronic health records to improve the quality and efficiency: the experiences of leading hospitals. Commonwealth Fund Pub. 2012;17:1–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nielsen PE, Thomson BA, Jackson RB, et al. Standard obstetric record charting system: evaluation of a new electronic medical record. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;966:1003–1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sherer SA, Meyerhoefer CD, Sheinberg M, et al. Integrating commercial ambulatory electronic health records with hospital systems: an evolutionary process. Int J Med Inform. 2015;84:683–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Miller DW, Yeast JD, Evans RL. The unavailability of prenatal records at hospital presentation. Obstet Gynecol-New York. 2003;101:87. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Moore C, Wisnivesky J, Williams S, et al. Medical errors related to discontinuity of care from an inpatient to an outpatient setting. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:646–651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kripalani S, LeFevre F, Phillips CO, et al. Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital-based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care. JAMA. 2007;2978:831–841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cebul RD, Rebitzer JB, Taylor LJ, et al. Organizational fragmentation and care quality in the US healthcare system. J Econ Perspect. 2008;224:93–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Maenpaa T, Suominen T, Asikainen P, et al. The outcomes of regional healthcare information systems in health care: a review of the research literature. Int J Med Inform. 2009;78:757–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hsaio C-J, King J, Hing E, et al. The role of health information technology in care coordination in the United States. Med Care. 2015;532: 184–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bernstein PS, Farinelli C, Merkatz IR. Using an electronic medical record to improve communication within a prenatal care network. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;1053:607–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cherouny P, Federico F, Haraden C, et al. Idealized design of perinatal care. In IHI Innovation Series White Paper. Cambridge, MA: Institute for Healthcare Improvement; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 12. McCartney PR. Using technology to promote perinatal patient safety. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2006;35:424–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Campbell EM, Li H, Mori T, et al. The impact of health information technology on work process and patient care in labor and delivery. In Advances in Patient Safety, Volume 4. Technology and Medication Safety. 2008. http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/quality-patient-safety/patient-safety-resources/resources/advances-in-patient-safety-2/Vol02407/Advances-Campbell_47.pdf Accessed January 1, 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Eden KB, Messina R, Hong L, et al. Examining the value of electronic health records on labor and delivery. Am J Obstet and Gynecol 2008;1993:307.e1–e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Edwards PL, Moloney KP, Jacko JA, et al. Evaluating usability of a commercial electronic health record: a case study . Int J Hum-Comp St. 2008;66:718–728. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bernstein PS, Merkatz IR. Reducing errors and risk in a prenatal network with an electronic medical record. J Reprod Med. 2007;5211:987–993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mann S, Marcus R, Sachs B. Lessons from the cockpit: how team training can reduce errors on L&D. Contemp OB/GYN. 2006;51:34–45. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mohr JJ, Barach P, Cravero JP, et al. Microsystems in health care: part 6. Designing patient safety into the microsystem. Joint Comm J Qual Patient Safety. 2003;29:401–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pope GC, Ellis RP, Ash AS, et al. Diagnostic Cost Group Hierarchical Condition Category Models for Medicare Risk Adjustment. (Final report to the Health Care Financing Administration under contract number 500-95-048) Waltham, MA: Health Economics Research, Inc.; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Meyerhoefer C, Deily M, Sherer S, et al. The consequences of electronic health record adoption for physician productivity and birth outcomes. Ind Labor Relat Rev. 2016;694:860–889. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.