Abstract

The increased adoption of clinical whole exome sequencing (WES) has improved the diagnostic yield for patients with complex genetic conditions. However, the informatics practice for handling information contained in whole exome reports is still in its infancy, as evidenced by the lack of a common vocabulary within clinical sequencing reports generated across genetic laboratories. Genetic testing results are mostly transmitted using portable document format, which can make secondary analysis and data extraction challenging. This paper reviews a sample of clinical exome reports generated by Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments–certified genetic testing laboratories at tertiary-care facilities to assess and identify common data elements. Like structured radiology reports, which enable faster information retrieval and reuse, structuring genetic information within clinical WES reports would help facilitate integration of genetic information into electronic health records and enable retrospective research on the clinical utility of WES. We identify elements listed as mandatory according to practice guidelines but are currently missing from some of the clinical reports, which might help to organize the data when stored within structured databases. We also highlight elements, such as patient consent, that, although they do not appear within any of the current reports, may help in interpreting some of the information within the reports. Integrating genetic and clinical information would assist the adoption of personalized medicine for improved patient care and outcomes.

Keywords: Common data elements, clinical WES, Health Level-7 Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources, electronic health records, exome report, structured vocabulary

INTRODUCTION

Until recently, physicians have approached genetic testing using single-gene and targeted gene-panel tests to identify disease-causing mutations underlying many complex genetic disorders. Single-gene tests are best suited to a distinct clinical phenotype indicating a possible genetic condition caused by a mutation in a single gene. A gene panel is best suited for diseases with limited locus heterogeneity, or when a clinician suspects multiple genes within a common pathway to be disease relevant.

Since the first human genome assembly was completed in 2003, the demand for cheaper and faster sequencing methods has continually increased.1 This demand gave rise to the massively parallel next-generation sequencing (NGS) technology that can perform whole exome sequencing (WES) or whole genome sequencing in an extremely short period of time.2 With decreasing costs and a reasonable molecular diagnostic rate (∼25%), WES is entering clinical genetics practice, allowing more efficient testing for disease-causing variants to aid in clinical diagnostics.3–6 In some cases, WES leads to earlier diagnosis, thus putting an end to the diagnostic odyssey physicians experience when attempting to identify the underlying cause of a patient’s disease. Physicians who adopt WES technology find that this gene-agnostic sequencing approach increases the likelihood of identifying the variants related to disease pathology, especially for rare genetic disorders.7 With the patient’s consent, secondary findings (SFs) for the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG)-recommended gene list may also be reported (59 genes).8 Although SFs are not directly related to the clinical phenotype for which the sequencing test was ordered, they could indicate an unknown diagnosis or a percentage risk for developing the disease in the future.9 Pharmacogenetic variants, which can aid the physician in treatment selection or tailoring of individual drug therapies (eg, to maximize efficacy or minimize the risk for potential adverse reactions), are also sometimes reported in a clinical report.

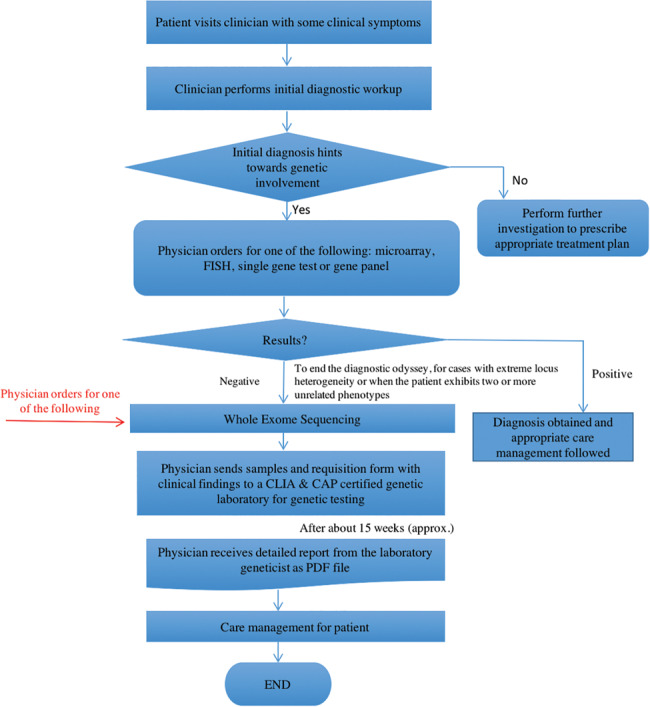

Typically, a physician orders WES when a patient’s clinical presentation indicates a genetically determined disease without a known genetic etiology, or when all indicated genetic testing results have been negative. In order to put an end to the diagnostic odyssey, the physician orders for WES and sends the patient’s samples for testing to a genetic laboratory (Figure 1 ) certified by the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988 (CLIA) and the College of American Pathologists (CAP). Typically, the turnaround time for results is ∼15–16 weeks. Most labs still continue to return a clinical summary report in portable document format (PDF), although there are substantial efforts being made in the area of electronic return of results that cannot be directly integrated into an electronic health record (EHR) system. It is important to note, however, that this time frame is typical for the return of a WES report, but other genetic testing gets done faster.

Figure 1.

A typical clinical exome sequencing workflow from patient first presenting symptoms at the clinic to care management based on the sequencing report.

The process of transmitting genetic test results to the EHR system can be cumbersome. Current practices at our facility and others involve manually uploading the clinical reports as PDF files into the EHR, which are then made viewable to physicians through a third-party application.10 Further, this unwieldy process and format prevents physicians from electronically querying and searching reports for information of interest. Interpretation of the variants of clinical interest is usually presented as free or semistructured text within the clinical report. The free-text nature of the report creates informatics challenges downstream, since discrete data elements are usually preferred in the informatics pipeline, especially for clinical decision support processes. This challenge compares to radiology informatics, where raw image data can be large, and its interpretation is usually in free-text format.11

Despite clinical-reporting format differences between laboratories, the content generally conforms to standards set by organizations such as CLIA, CAP, and the ACMG.12 Some of these standards have been created through multiple rounds of workgroup discussions, involving clinicians from different subspecialties.13 Based on these discussions, the Research and Development Advisory Board came up with a template for the different entities that should be included within a genetic test report.14,15 However, extracting discrete information from PDF files is a major pitfall. Manually sifting through text documents is error-prone and precludes using a single application to display both genomic and clinical information. Moreover, a hospital can receive sequencing results from multiple genetic labs, each with a different reporting format. Any slight variation in format and content in clinical reports across multiple genetic labs (eg, continually upgrading their standards over time) poses an interoperability issue when trying to consolidate report information from different labs into a single data source. Standardized discrete information elements are essential for integrating genomic information into EHRs to improve outcomes.

Some of these issues can be addressed with uniform reporting across genetic labs. This review aims to compare clinical reports from various genetic laboratories and identify some of the common data elements (CDEs) within a WES clinical report. A CDE is defined as a logical unit of data that contains information of a single kind.16 The “commonality” term does not require that the term be part of every clinical report. A CDE can be included in a list if it is found in >50% of the sample reports or is identified in the literature and by experts as being critical for clinical interpretation of sequencing. Organizations such as CLIA, CAP, and ACMG have standard guidelines for what should definitely be included within a clinical report. Health Level-7 International (HL7) is an organization dedicated to providing a framework for the standardized exchange of electronic health information. With the world moving toward implementing precision medicine, HL7 is currently working on coming up with standards for genomics data that can facilitate their integration into EHR systems. Similarly, Logical Observation Identifiers Names and Codes is currently extending its framework to include structured codes for genetic test orders as well as results. The established CDEs have been compared with these different standards to identify elements currently missing in lab reports that can potentially benefit the clinical community, if available. Identifying discrete CDEs will simplify transmission of genetic information from labs to physicians, and finally into the EHR.

The goal of this review is to analyze clinical sequencing reports from multiple clinical laboratories and identify the CDEs. The intent of this manuscript is 3-fold: to highlight (1) the genomic data elements reported by various genetic laboratories, (2) the inconsistency in information across labs, and (3) elements that are currently missing but could potentially be beneficial to physicians if included in reports. We limit the analysis to reports generated from WES, with the future goal of applying a similar model to whole genome sequencing test reports. We aspire to raise awareness of the complexity and weaknesses currently associated with genetic test reports, ultimately to help improve diagnostic outcomes and therapeutic options.

EXAMPLE REPORTS FROM CLIA- AND CAP-CERTIFIED LABORATORIES

Few CLIA- and CAP-certified laboratories have clinical WES capabilities. We contacted representatives and analyzed sample reports from the following vendors: Baylor, Emory Genetics, Partners Healthcare, ARUP Labs, Ambry Genetics, and GeneDx.

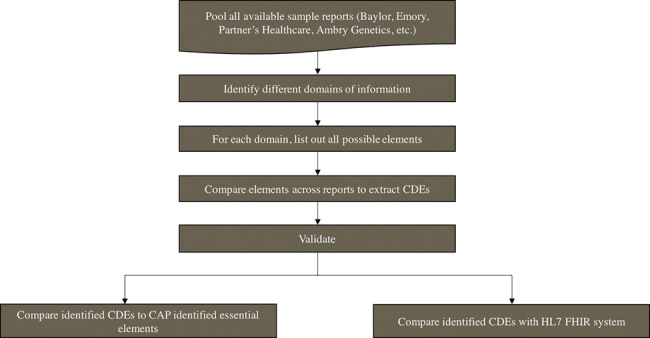

To identify the CDEs, each report was manually analyzed using the workflow shown in Figure 2 . Data elements related to a common entity were grouped into larger blocks of information, termed “domains.” For example, a clinical domain like Patient Demographics contains different types of information about the common entity, the patient (eg, Patient Name, Patient ID, Patient Age, Patient Gender, etc.). Domains can be simple, containing only elements, or branched into subdomains, depending on the complexity of the information.

Figure 2.

Process for identifying and validating common data elements (CDEs) from sample clinical exome reports.

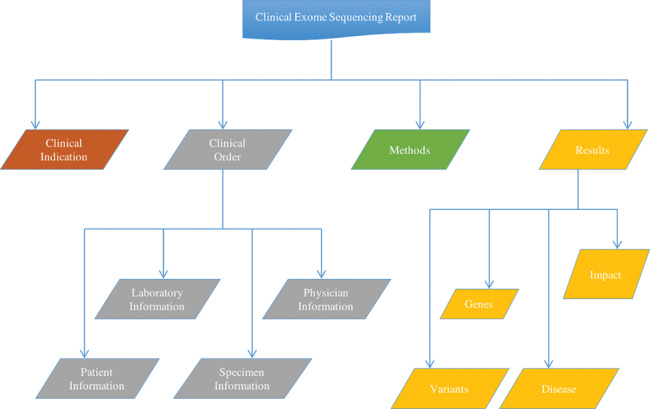

Four major domains, Clinical Indication, Clinical Order, Methods, and Results, along with several subdomains and elements, shown in Figure 3 , were identified as contained in the different clinical exome sequencing reports and described in detail below.Supplementary Table S1 gives a distribution of all the identified domains and elements across the different genetic testing reports. The complete list of identified CDEs, along with small descriptions, is shown in Table 1 below.

Figure 3.

Major domains and subdomains identified by comparing the different clinical exome sequencing reports. Four major domains of information were identified within an exome sequencing report. The homogenous domains, Clinical Indication and Methods, each have elements only (not shown), whereas the heterogeneous domains, Clinical Order and Results, are subdivided into subdomains, each with their own elements (not shown).

Table 1.

Common data elements identified by analyzing the different clinical exome sequencing reports

| Common Data Elements | Descriptions |

|---|---|

| Patient Name | Name associated with the patient |

| Patient ID/MRN | Unique ID or medical record number associated with a patient. Some places use generic IDs, whereas others use medical record numbers. The purpose of both is to uniquely identify a patient. |

| DOB | Date of birth of the patient |

| Gender | Gender/sex of the patient |

| Requisition #/Accession # | Identifies the order placed by the physician for a particular patient and all the associated specimens. |

| Specimen Type | DNA from blood (most common) and saliva comprise the most common specimen types. |

| Specimen Collection Date | Date the specimen was collected by the lab |

| Specimen Received Date | Date the specimen was received by the genetic laboratory |

| Test Ordered on Specimen | Date the test was ordered by the send-out lab |

| Test Reported on Specimen | Date the test results were reported |

| Laboratory ID | ID of the lab conducting the genetic test |

| Referring Physician Name | Physician who ordered the genetic test |

| Referring Hospital/Facility | Affiliated hospital/facility of the referring physician |

| Medical History | Medical history/diagnoses associated with the patient at the time he or she first saw the doctor |

| Primary Findings | All variants identified in genes that are associated with the clinical phenotype of the patient |

| Medically Actionable Findings | Any pathogenic variant found in genes not directly associated with the clinical phenotype of the patient but have been deemed medically actionable by ACMG guidelines |

| Carrier Status | Carrier status of the patient if a variant is found in one of the ACMG recommended sets of autosomal recessive disorders |

| Pharmacogenetic Results | Variants in specific genes involved in drug metabolism, such as VKORC1/CYP2C9 and CYPC19 |

| Gene Name | Human Gene Nomenclature Committee gene symbol of the gene where a variant has been found |

| Associated Disease | Disease associated with the gene where a candidate disease-causing variant is found |

| Inheritance Pattern | Mode of inheritance of the disease within family members (eg, autosomal dominant, recessive, etc.) |

| Co-segregation of Variant | Specifies whether the variant is found among all affected in the family and not found among unaffected. |

| DNA Change | Specific nucleotide change associated with the variant |

| Protein Change | Specific amino acid change associated with the variant |

| Transcript Identifier | Specific transcript within the gene that contains the mutation |

| Chromosomal Location | Exact location of a variant with respect to the chromosome, that is, chromosome number and positional coordinate |

| Zygosity | Specifies whether both alleles contain the variant (homozygous) or one of the alleles contains the variant (heterozygous). |

| Frequency of Variant Within Healthy Population | Variant frequency seen among healthy individuals (ie, what is its frequency in the 1000 Genomes database or other databases that contain information from healthy individuals) |

| Variant Conservation | Mutations found in a highly conserved region are more likely to be lethal/pathogenic. |

| Variant Clinical Significance | Classifies whether the identified clinically significant variant is pathogenic, likely pathogenic or a variant of uncertain significance. |

| Reference Genome Build | Version of the reference genome used when performing sequence assembly and variant calling |

| References | Links to publications and databases that support the results |

| NGS Method | Specific next-generation sequencing technology used by the laboratory |

| Sequencing Platform | Specific sequencing platform used for the process |

| Exome Coverage | Percentage of exomes covered through the sequencing process |

| Confirmation Using Sanger Sequencing | All candidate variants are verified through Sanger sequencing. |

The domains correspond chronologically with the clinical exome sequencing pipeline, where the physician first makes a diagnosis based on some of the initial clinical symptoms, then orders a genetic test if the diagnosis indicates a potential genetic involvement. Sometimes a gene panel or microarray test is sufficient to identify the cause, but in some cases the physician might enter a diagnostic odyssey. In such cases, a WES test is ordered, since it has a comparatively better diagnostic rate over other tests, thus giving a better edge over others. We describe in greater detail below the different domains and subdomains along with the representative elements within each.

The Clinical Indication domain represents the clinical phenotypes observed in the patient before sequencing. Some laboratories that offer exome sequencing on parental samples also report phenotypes previously observed within other members of the family, which can be used for variant interpretation. Clinical Indication is a homogenous domain whose elements include Medical History and Family Information.

Clinical Order is the second major domain within a clinical report. While subdomains and elements within this domain do not really influence the interpretation of the clinical report, they are useful metadata within a database that link the sequencing results with entities such as specimen or patient. Clinical Order, a heterogeneous domain, has different subdomains, including Patient Information, Laboratory Information, Specimen Information, and Physician Information. The Patient Information subdomain includes all demographics related to the patient (eg, patient name, patient ID, age, etc.). The Laboratory Information subdomain provides details on the genetics lab performing the exome sequencing experiment on the samples and includes the single element Laboratory ID. Since every patient is associated with at least 1 specimen for DNA sequencing, the Specimen Information subdomain includes the elements Specimen Type, Collection Date, Order Date, etc. Physician Information (Table 1) is the final subdomain in Clinical Order and includes details on the ordering physician (eg, elements like physician name, affiliated hospital, address).

The Methods domain serves as a footprint of the associated clinical report, since a different sequencing method or coverage can lead to a new set of variants being identified. Although information within this domain does not directly impact clinical interpretation, its vital role can lead to differences in the final set of clinically significant variants obtained.17 The specific sequencing technology used (ie, type of capture, sequencing instrument used, genotyping/aligning/calling/annotating pipeline used, reference database), along with details on coverage, constitute most of the information within this domain. This homogenous domain includes the following elements of Sequencing Type, such as NGS Methodology and Platform.

The final domain, Results, is the most important entity within a clinical exome sequencing report. When a pathogenic/likely pathogenic variant is identified (a positive result), the information within this domain assists the physician in identifying the medical cause and providing the patient with a molecular diagnosis. This informative domain has the most profuse variations across reports and can be divided into 4 major subdomains: Variants, Genes, Disease, and Impact.

Variant subdomain: A sequencing test is conducted to identify pathogenic/likely pathogenic variants that may be related to the phenotype observed in the patient. Information associated with a particular change in a given genomic location forms the Variant subdomain and its associated elements (eg, Variant ID, DNA Change for Variant, Protein Change for Variant, Zygosity, etc.). Avariant can be classified as being pathogenic, likely pathogenic, likely benign, benign, or of unknown significance.12 Knowledge bases are constantly evolving with new variant information updated daily, and there are documented inconsistencies across laboratories in variant reclassification.18 Sufficient evidence could be gathered over time to cause a variant previously characterized as benign or of unknown significance to be amended as a pathogenic variant, and vice versa. Tracking the updates within different knowledge bases is critical for accurately reporting/updating information.

Gene subdomain: Typically, a variant is associated with a given genomic location. Depending on the type of sequencing performed, a variant could be exonic, intronic, intergenic, etc. Since we are restricting data to that in exome sequencing reports, each variant lies either within or near the coding region of a gene, giving rise to the Gene subdomain. The Gene subdomain groups all variants found at or close to a given gene and contains the elements of Gene Name, Position, etc.

Disease subdomain: Mapping the gene/variant information to the associated disease(s)/phenotype(s) found within external databases like the Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) creates the Disease subdomain. The elements within this subdomain include Disease Name, OMIM ID (if available and part of OMIM) and Mode of Inheritance (Table 1). The identified variant can be either linked to a previously identified disease or associated more at the gene level. While the associated disease phenotypes could match the clinical phenotype of the patient, at other times the identified variant can be linked to a different, yet medically actionable, disease phenotype (called an incidental finding).

Impact subdomain: The results within a clinical report are typically broken down into subsections, based on whether they are related directly or indirectly to the clinical condition of the person, thus laying the foundation for the Impact subdomain, whose elements include: (1) Primary (where the variant is directly related to the patient’s phenotype), (2) Medically Actionable (where the variant is associated with a disease phenotype not currently observed in the patient), (3) Carrier Status (identifies carriers of an autosomal recessive disease), and (4) Pharmacogenetic Status (mutations in genes related to drug metabolism).

HL7-FHIR STANDARD FOR GENOMICS

Once the CDEs are identified, they are compared to the existing data model within the HL7 framework, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Comparative analysis of the essential elements clinical exome common data elements (CDEs) and the HL7 Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resource (FHIR) genetic analysis data model

| Clinical Exome CDEs | Overlap between CDEs and HL7 FHIR Elements | HL7 FHIR Standard Profile for Genetics Elements |

|---|---|---|

| Patient Name | N | N |

| Patient ID/MRN | N | N |

| DOB | N | N |

| Gender | N | N |

| Requisition #/Accession # | N | N |

| Family # | N | N |

| Specimen Type | N | N |

| Specimen Collection Date | N | N |

| Specimen Received Date | N | N |

| Test Ordered on Specimen | N | N |

| Test Reported on Specimen | N | N |

| Medical History | Y | geneticsAssessedCondition |

| Gene Name | Y | geneticsGene |

| National Center for Biotechnology Information Transcript Reference | Y | geneticsTranscriptReferenceSequenceID |

| Exons | Y | geneticsDNARegionName |

| Associated Disease | N | N |

| Inheritance Pattern | N | N |

| Chromosomal Location of Variant | Y | geneticsChromosome/geneticsGenomics |

| Start/geneticsGenomicsStop | ||

| DNA Change | Y | geneticsDNASequenceVariation |

| Protein Change | Y | geneticsAminoAcidChange |

| Zygosity | Y | geneticsAllelicState |

| Population Level Frequency | Y | geneticsAllelicFrequency |

| Variant Clinical Significance | N | N |

| Genome Build | Y | geneticsGenomeBuild |

| Reference | N | N |

| NGS Method | N | N |

| Sequencing Platform | N | N |

| Exome Coverage | N | N |

| Read Length | N | N |

| N | N | geneticsCIGAR |

| N | N | geneticsVariationID |

| N | N | geneticsDNASequenceVariationType |

| N | N | geneticsAminoAcidChangeType |

| N | N | geneticsGenomicSourceClass |

| N | N | geneticsSpecies |

Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources (FHIR) is the latest HL7 protocol for exchanging health information. HL7 has been involved with health care data modeling for >20 years. The FHIR specifications combine features from previous versions of HL7.19 All data are encapsulated within defined Resources, which are extensible over time with an identifying URL.

Initially, Resources managed, stored, and exchanged various hospital-related information, including clinical, financial, and administrative information. But the integration of genomic data into the clinic prompted HL7-FHIR to include Standard Profile for Genetics as an extension to the Observation resource to report structured genetic test results. Although the resource is generic in nature to report information for any type of genetic test, HL7-FHIR is the best available data model with which to compare the CDEs identified here.

The Standard Profile for Genetics resource within FHIR is used to store structured genetic test results. This resource contains 4 major domains: Sequence Information, Variation, Context, and State. The Sequence Information domain contains elements that describe all sequencing-related information, such as genome build used for assembly, chromosomal coordinates, reference/alternate alleles, etc. The Variation domain contains elements about the identified variation itself, such as variant ID, DNA change, protein change, etc. The context of the variation is captured within the Context subdomain, which contains elements such as the gene where the variant is found, whether the variant is exonic/intronic, the tissue where the variant is found, etc. Finally, the State subdomain contains additional information regarding the variant, such as its allele frequency, coverage, zygosity in the individual, etc. Table 2 displays the list of elements common to the CDEs and HL-7 model and highlights domains and elements that are entirely missing from the HL7 model, such as Clinical Order. This can be due to some of the elements within the Clinical Order domain not being directly associated with a genetic test result. Besides, other independent resources in HL7 such as Patient, Practitioner, etc., can be used to structure the information seen in the Clinical Order section of a clinical report. A high degree of similarity in elements exists within the Variant and Gene domains, which capture most of the relevant information from a sequencing experiment. The Variant Clinical Significance element is not part of the HL7 list, despite its ability to characterize the variant as being clinically significant (based on some defined rules). The Clinical Significance element is common to all reports used in this review. Likewise, Table 2 also shows elements that are part of the HL7 model but were not part of the lab reports. Although none of the missing elements are critical for the interpretation process, these elements were uniformly overlooked by all the participating laboratories whose reports were assessed here.

DISCUSSION

The effort to integrate genetic information with EHRs further drives personalized medicine. The completion of the Human Genome Project laid the foundation for personalized medicine by giving health care providers the appropriate science and tools to define disease at the molecular level.20 A lack of published standards creates a bottleneck in the practice of personalized medicine.17 One of the many challenges is the diversity of genetic data, available in varying formats and naming conventions. Many clinicians have previously expressed dissatisfaction with clinical genetic test reports, due partly to variations in reporting formats.13,21 Often, clinicians have difficulty interpreting every bit of information within a clinical report, perhaps due to a lack of knowledge as well as a lack of structure in the reports.18 Structured reporting of genetic test results could promote greater ease of understanding among clinicians, resulting in improved patient outcomes. The variation in genetic test reports represents a similar situation to radiology reporting. At the beginning, radiology reports also lacked a definite structure and format, making data retrieval and integration a challenge. Structured reporting allows for automated or semiautomated abstraction of the data that can be used for research and clinical quality improvement.22 Surveys of physicians and continuous discussions among radiology board members helped resolve the issue. But this is never a onetime process, and constant improvements are made to these standards over time.

When comparing the different clinical reports, most of the domains and subdomains identified indicate a high level of agreement between laboratories, with a few disparate cases. A limitation of this review is that by examining only one sample report per laboratory, we disregarded potential interreport variability within the same laboratory.

The Variants subdomain contains the largest number of elements of all identified domains and subdomains. This is expected, since a clinician orders a WES for diagnostic and disease management purposes. This largest subdomain likewise also contains the greatest variability in elements, as observed among the reporting laboratories. Thus automated or semiautomated comparisons across reports from multiple laboratories becomes a major challenge for clinicians. Although the genome build is required by CAP, different laboratories demonstrate a high variability in reporting the build used (Supplementary Table S1). Some reports mentioned chromosomal locations without reference to the genomic build; manually cross-referencing 2 such reports takes considerable effort to discern whether both reports refer to the same variant or different variants.

Information within the Methods domain is reasonably homogeneous across all laboratory reports, which reflects its importance in downstream interpretation. Differences in the sequencing methodology and the bioinformatics pipelines used for NGS analyses can be a significant source of variability in the final outcome.23 Sometimes 7%–10% of the exons can contain very low-quality sequence reads, preventing an accurate variant call and leading to false positive and false negative results. Although the Methods domain contains an element that represents the minimum coverage maintained by the experiment, the exact coverage associated with a clinically significant variant is never reported. Regions of insufficient coverage are also not reported. Although the recommended guidelines do not mandate reporting of the coverage associated with an individual variant, this element can help discriminate a false positive from a true clinically significant variant.

Although some standards do exist for genetic data (eg, most laboratories use Human Genome Variation Society nomenclature for representing genetic mutations), strict adherence to rules when creating genetic sequencing reports is limited. Discrepancies regarding what information is critical for making a clinical diagnosis are common. The CAP guidelines require the following information, as shown in Table 3, be part of every clinical report: Variants reported using Human Genome Variation Society nomenclature, that includes a gene name (including the Human Genome Organization identifier) and a versioned reference transcript (Transcript Reference ID from National Center for Biotechnology Information, Ensembl, etc.), reference sequence genome assembly and version number, and genomic coordinate for each variant (Variant Chromosomal Position).

Table 3.

Presence of CLIA/CAP/ACMG elements across laboratory reports

| Data Element | CLIA/CAP/ACMG Guidelines | Emory | Baylor | Partners Healthcare | Ambry | ARUP Labs | GeneDx |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human Genome Variation Society Nomenclature for Variant | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Transcript Reference | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Reference Sequence Genome | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Variant Chromosomal Position | Y | N | Y | N | Y | N | N |

| Variant Classification | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N |

Most of the laboratory reports we studied contained these elements, but not all. Not all CAP-certified laboratories reported all of the mandatory elements. The variant chromosomal position is reported in only 4 of the 6 labs studied. This is the most basic information associated with a variant and is used to map a variant within the genome. This information is also necessary from a database standpoint, since it helps to uniquely identify every variant. One of the challenges often faced when reporting genomic coordinates is that they change with every version/build of the human genome. Thus, as a complement, the reference genome version should also be included in the clinical report. Laboratories that do not report genomic coordinates do mention the reference genome version within their clinical reports, whereas those that report the variant chromosomal position omit the genome build. Since the 2 pieces of information are complementary, reports should include both elements or neither; reporting only 1 makes the information irrelevant. One of the 6 laboratories also does not comply with the requirement of reporting the actual transcript where the mutation occurs. This omission makes interpretation largely complicated, especially in cases where a single gene can harbor multiple functional transcripts and each transcript can contain different mutations.

There is also a lot of information collected as part of the routine genetic testing process but never mentioned in clinical reports. One example is patient consent, which is universally missing from all reports used in this study. Clinical reports can vary incredibly, depending on what information patients wish to obtain for themselves and what to allow other physicians and researchers to obtain. This can get extremely complicated, as there are different levels of information. A patient can consent at the beginning for a specific task to be performed but withdraw it after some time, making it a challenge to manage the data. This is one of the reasons for not including it as part of a clinical report, since it is hard to withdraw data from an existing report. Currently, an entire area of consent management is dedicated to managing this complex information. Such changes are easier to keep track of in a database setting, and this could be a reason to include some consent-related information in clinical reports. It is also hard to interpret empty headers in clinical reports, since they could be due to 1 of 2 reasons: either the patient did not consent for the data to be viewable, or there was no information for the particular patient to be displayed. Both cases would be represented as a blank field within a database, thus making interpretation and downstream decision support difficult.

The other missing entity is the list of knowledge bases, along with their version numbers, that is used as part of the bioinformatics pipeline to generate the final list of clinically significant variants. One version of a knowledge base might label a variant “benign,” whereas an updated version might call it “pathogenic.” It is important to capture these transitions, both to keep the patient informed and for trace-back purposes. Currently, many of the lab reports mention some of the knowledge base names. But this needs to happen universally in a more consistent format for better care management.

Identifying the CDEs is a critical step in facilitating the return of structured genomic data from laboratories. Since the long-term goal is to store this structured information as discrete fields with the EHR, the next logical step in this direction would be to bin the range of values that is acceptable for each CDE when stored within a database-like setting.

CONCLUSION

The focus of the present study was to identify some CDEs by comparing various clinical reports, and not to model the acceptable range of values for every element. Since a given element (eg, the cDNA reference sequence) can be represented through either an accession number or a different identifier, non-uniformity in the reporting may result. Therefore, identifying the range of values for a given element is the next logical step in establishing a common database schema. We defer to organizations such as HL7 and Logical Observation Identifiers Names and Codes to standardize the vocabulary used with genomic information. The current study focused on WES reports, with the intent of being able to apply the standards to other genetic tests, such as gene panels or whole genome sequencing. The guidelines set by CLIA/CAP/ACMG for reporting results from single-gene or multigene panel tests are similar to the guidelines set for WES reports. The main difference is the absence of secondary findings for both single-gene and gene-panel tests. With sharply decreasing costs and rising rates of adoption in clinical diagnostics, accurate identification and management of genomic information for NGS can elevate patient care to a new level. Therefore, identifying a concrete, consistent set of data elements surrounding variant representation will facilitate integrating WES into patient diagnosis and clinical care.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sector.

Competing Interests

None.

Author Contributions

SML, YH, and RS contributed to the conception and study design. RS analyzed the different genetic lab reports, identified the CDEs, and wrote the draft. CA and SFB contributed to the clinical lab information within the manuscript. RS, YH, CA, SFB, KM, JC, CB, and SML reviewed and revised the draft to generate the final manuscript.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary material is available at Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association online.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Grant Wood, Jeff Hoffman, and Kim McBride for reviewing the manuscript, Julie Gastier-Foster for participating in discussions, and Melody Davis for scientific edits to the manuscript.

References

- 1. Grada A, Weinbrecht K. Next-generation sequencing: methodology and application. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:e11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pareek CS, Rafal S, Andrzej T. Sequencing technologies and genome sequencing. J Appl Genet. 2011;52:413–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Goh G, Choi M. Application of whole exome sequencing to identify disease-causing variants in inherited human diseases. Genomics Inform. 2012;10:214–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yang Y, Yaping Y, Muzny DM. et al. Clinical whole-exome sequencing for the diagnosis of Mendelian disorders. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1502–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bainbridge MN, Wiszniewski W, Murdock DR. et al. Whole-genome sequencing for optimized patient management. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:87re3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. de Ligt J, Willemsen MH, van Bon BWM. et al. Diagnostic exome sequencing in persons with severe intellectual disability. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1921–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Stavropoulos DJ, Daniele M, Rebekah J. et al. Whole-genome sequencing expands diagnostic utility and improves clinical management in paediatric medicine. NPJ Genomic Med. 2016;1:15012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kalia SS, Adelman K, Bale SJ. et al. Recommendations for reporting of secondary findings in clinical exome and genome sequencing, 2016 update (ACMG SF v2.0): a policy statement of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics. Genet Med. 2016;19:249–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Green RC, Berg JS, Grody WW. et al. ACMG recommendations for reporting of incidental findings in clinical exome and genome sequencing. Genet Med. 2013;15:565–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. McLaughlin HM, Ceyhan-Birsoy O, Christensen KD. et al. A systematic approach to the reporting of medically relevant findings from whole genome sequencing. BMC Med Genet. 2014;15:134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Danton GH. Radiology reporting, changes worth making are never easy. Appl Radiol. 2010;39:19–23. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S. et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17:405–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lubin IM, McGovern MM, Gibson Z. et al. Clinician perspectives about molecular genetic testing for heritable conditions and development of a clinician-friendly laboratory report. J Mol Diagn. 2009;11:162–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Scheuner MT, Hilborne L, Brown J. et al. A report template for molecular genetic tests designed to improve communication between the clinician and laboratory. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 2012;16:761–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Scheuner MT, Edelen MO, Hilborne LH. et al. Effective communication of molecular genetic test results to primary care providers. Genet Med. 2013;15:444–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. [No title]. https://c-path.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/Creating-Common-Data-Elements-for-Neurologic-Diseases.pdf. Accessed June 17, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Brownstein CA, Beggs AH, Homer N. et al. An international effort towards developing standards for best practices in analysis, interpretation and reporting of clinical genome sequencing results in the CLARITY Challenge. Genome Biol. 2014;15:R53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Amendola LM, Jarvik GP, Leo MC. et al. Performance of ACMG-AMP variant-interpretation guidelines among nine laboratories in the clinical sequencing exploratory research consortium. Am J Hum Genet. 2016;99:247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bender D, Sartipi K. HL7 FHIR: An agile and RESTful approach to healthcare information exchange In: 2013 IEEE 26th International Symposium on Computer-Based Medical Systems. 10 October 2013:326–31; Porto, Portugal. [Google Scholar]

- 20. McCarthy JJ, McLeod HL, Ginsburg GS. Genomic medicine: a decade of successes, challenges, and opportunities. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5:189sr4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Krousel-Wood M, Andersson HC, Rice J. et al. Physicians’ perceived usefulness of and satisfaction with test reports for cystic fibrosis (DeltaF508) and factor V Leiden. Genet Med. 2003;5:166–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kahn CE, Langlotz CP, Burnside ES. et al. Toward best practices in radiology reporting 1. Radiology. 2009;252:852–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. O’Rawe J, Jiang T, Sun G. et al. Low concordance of multiple variant-calling pipelines: practical implications for exome and genome sequencing. Genome Med. 2013;5:28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.