Abstract

Objective

While most hospitals have adopted electronic health records (EHRs), we know little about whether hospitals use EHRs in advanced ways that are critical to improving outcomes, and whether hospitals with fewer resources – small, rural, safety-net – are keeping up.

Materials and Methods

Using 2008–2015 American Hospital Association Information Technology Supplement survey data, we measured “basic” and “comprehensive” EHR adoption among hospitals to provide the latest national numbers. We then used new supplement questions to assess advanced use of EHRs and EHR data for performance measurement and patient engagement functions. To assess a digital “advanced use” divide, we ran logistic regression models to identify hospital characteristics associated with high adoption in each advanced use domain.

Results

We found that 80.5% of hospitals adopted at least a basic EHR system, a 5.3 percentage point increase from 2014. Only 37.5% of hospitals adopted at least 8 (of 10) EHR data for performance measurement functions, and 41.7% of hospitals adopted at least 8 (of 10) patient engagement functions. Critical access hospitals were less likely to have adopted at least 8 performance measurement functions (odds ratio [OR] = 0.58; P < .001) and at least 8 patient engagement functions (OR = 0.68; P = 0.02).

Discussion

While the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act resulted in widespread hospital EHR adoption, use of advanced EHR functions lags and a digital divide appears to be emerging, with critical-access hospitals in particular lagging behind. This is concerning, because EHR-enabled performance measurement and patient engagement are key contributors to improving hospital performance.

Conclusion

Hospital EHR adoption is widespread and many hospitals are using EHRs to support performance measurement and patient engagement. However, this is not happening across all hospitals.

Keywords: hospitals, EHR adoption, digital divide

BACKGROUND AND SIGNIFICANCE

Over the past 6 years, US hospitals have rapidly adopted electronic health records (EHRs) in response to financial incentives through Medicare and Medicaid.1,2 In the last national data, over three-quarters of hospitals had adopted at least a basic EHR, up from 9% in 2008.3–9 In addition, adoption was fairly evenly distributed across different types of hospitals, and notably, there was little evidence of a digital divide between safety-net and non–safety-net hospitals. However, there were some differences in adoption, with small and rural hospitals lagging behind. Assessing the most recent data on national EHR adoption is therefore critical to determine whether these hospitals are catching up.

While it is encouraging that we largely avoided a digital divide in EHR adoption, it is possible that a new type of divide may emerge among hospitals that have adopted EHRs. Many of the benefits expected from EHRs require advanced functions that go beyond using the core capabilities of these systems to document and manage individual patient care. Two domains of advanced use are particularly critical to the realization of expected benefits: using EHR data for performance measurement, and engaging patients through better access to their data as well as supporting other patient-centric care activities. The former enables performance feedback via dashboards and other approaches to identify domains of suboptimal performance.10,11 The latter ensures that patients can be active participants in their care and facilitates engagement in self-management.12,13

There is reason to believe that not all hospitals are equally capable of pursuing these advanced EHR functions. Performance measurement using EHR data requires both technical skills to extract and manage data and analytic skills to turn data into meaningful and accurate quality measures. Patient engagement functions require redesigned workflows, as well as dedicated staff time, to ensure that patients understand how to use newly available functions, and to respond to patient questions in secure messages, patient-generated health data, and requests for changes to their records.

OBJECTIVE

In this study, we use data from the most recent American Hospital Association (AHA) Annual Survey of Hospitals Information Technology (IT) Supplement to report the most recent measures of EHR adoption across US hospitals. We then assess the extent to which hospitals are engaged in 10 functions related to using EHR data for performance measurement and 10 functions related to using EHRs to engage patients. We assess the potential emergence of a digital “advanced use” divide by examining whether certain types of hospitals – in particular, small, rural, safety-net hospitals – are less likely to have adopted these advanced functions. Our results are critically important to determine the extent to which hospitals are pursuing the advanced EHR functions needed to maximize potential benefits from EHR adoption. They also serve to inform policymakers on whether additional policy interventions may be needed to ensure that EHRs facilitate the transformation to a high-performing, data-driven, patient-centric health care system.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Survey

We used data from the AHA Annual Survey IT Supplement for information technology adoption from 2008 to 2015. The survey is sent to the chief executive officer of every US hospital, who is asked to complete it or delegate completion to the most appropriate person in the organization. All nonrespondents receive multiple mailings and follow-up phone calls to achieve a high response rate. The most recent survey was fielded from December 2015 to March 2016. Hospitals completed the survey online or by mail. Survey questions capture information about the extent of adoption of a range of individual computerized clinical and patient-facing functions as well as use of EHR data for performance measurement. The survey was sent to 6290 hospitals and received 3538 responses (56% response rate).

Measures: electronic health record adoption

The current level of EHR adoption among US hospitals was evaluated using prior definitions of computerized functions required for basic and comprehensive EHR systems.14 A hospital with at least a basic EHR system reported full implementation of the following 10 computerized functions in at least 1 clinical unit of the hospital: patient demographics, physician notes, nursing assessments, patient problem lists, patient medication lists, discharge summaries, radiology reports, laboratory reports, diagnostic test results, and order entry for medications. A hospital with a comprehensive EHR system reported all basic functions, along with 14 additional functions, fully implemented across all major clinical units. Those additional functions are: support for advance directives; order entry for lab reports, radiology tests, consultation requests, and nursing orders; ability to view radiology images, diagnostic test images, and consultant reports; and clinical decision support for clinical guidelines, clinical reminders, drug allergy results, drug-drug interactions, drug-lab interactions, and drug dosing support.

Measures: advanced use – performance measurement and patient engagement functions

We used additional questions on the AHA Annual Survey IT Supplement to capture hospital adoption of EHR functions in 2 advanced domains. First, we captured whether or not hospitals engaged in each of 10 uses of EHR data for performance measurement. These functions were: creating dashboards of organizational, unit-level, and individual performance; allowing clinicians to query data; assessing adherence to clinical guidelines; identifying care gaps for specific patient populations; generating reports to inform strategic planning; supporting a continuous improvement process; monitoring patient safety; and identifying high-risk patients for follow-up care. Second, we captured whether or not hospitals adopted each of 10 patient-facing EHR functions. These functions allowed patients to: view, download, and electronically send their health information online; request amendments to their medical record; request refills for prescriptions, schedule appointments, and pay bills online; submit patient-generated data; use secure messaging with providers; and designate family members or caregivers to access information on their behalf. Supplementary Table S1 includes the full text of relevant survey questions. None of these functions were part of the definition of a basic or comprehensive EHR.

Measures: hospital characteristics

We used data from the 2014 AHA Annual Survey to capture key hospital characteristics that have been shown in prior work to be associated with EHR adoption: size (<100 beds, 100–399 beds, ≥400 beds), teaching status, ownership, region, urban or rural location, and participation in reform programs (both a patient-centered medical home [PCMH]15 and an Accountable Care Organization [ACO],16 an ACO only, a PCMH only, or neither).

To assess safety-net status, we used 2 measures. First, we examined critical-access hospitals (CAHs), which have ≤25 beds and provide the majority of care in areas where access is limited. Second, we used the Medicare disproportionate share hospital (DSH) index, which is based on the fraction of a hospital’s elderly Medicare patients who are also eligible for Supplemental Security Income and the fraction of nonelderly patients with Medicaid. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services uses this formula to identify hospitals for additional Medicare payments in caring for impoverished populations. We used the 2015 Impact File compiled by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services to obtain each hospital’s DSH index and segmented hospitals into quartiles, with hospitals in the top quartile representing those with the highest DSH index. The 25th percentile for DSH payments was 18.6%, the median was 25.7%, and the 75th percentile was 34.8%. DSH index was not available for 29% of hospitals in our sample, all but 37 of which were CAHs, since CAHs do not report DSH data. We excluded these 37 hospitals from our analysis.

Analyses

Of the 3538 hospitals that responded to the survey, we limited our sample to the 2803 nonfederal general medical and surgical acute-care hospitals in the 50 states and the District of Columbia. To adjust for nonresponse bias and to generate nationally representative estimates, results were weighted using an inverse probability weight generated from a model predicting survey response based on size, ownership, teaching status, system affiliation, urban or rural location, region, and critical access status.17

To assess national hospital EHR adoption trends, we calculated the weighted proportion of hospitals that had adopted at least a basic EHR system or a comprehensive EHR system in 2015 and then compared those numbers to the weighted proportion reported in 2008–2014.3–9 Next, we calculated 2015 EHR adoption levels – comprehensive, basic, or less than basic – for key hospital characteristics, including our 2 measures of safety-net status. To account for nonresponse bias, we report weighted percentages.

We then used a multinomial logistic regression to examine the relationships between each hospital characteristic and the hospital’s likelihood of having adopted at least a basic EHR (but less than comprehensive EHR) or at least a comprehensive EHR, compared to having adopted less than a basic EHR. We selected a multinomial model over an ordered model, because we hypothesized that different factors would be associated with whether a hospital could advance from less than basic to basic EHR (ie, paper to electronic) as opposed to basic to comprehensive EHR (ie, adding breadth and depth of electronic functions); this hypothesis was empirically supported by a Brant test that showed that our data violated the proportionality assumption. To provide context for EHR adoption results, we calculated the weighted proportion of hospitals reporting each of 9 possible barriers to EHR adoption.

To assess national hospital engagement in the 2 domains of advanced use, we calculated the weighted proportion of hospitals that used EHR data for each of the 10 potential functions. We also calculated the proportion of hospitals that adopted at least 8 of the 10 functions as well as all 10 functions. We then used a logistic regression to examine the independent relationships between each hospital characteristic and the odds of adopting at least 8 functions.

Finally, we calculated the weighted proportion of hospitals that adopted each of the 10 patient engagement functions. We again calculated the proportion of hospitals that adopted at least 8, as well as all 10, functions. We then used a logistic regression model to examine the independent relationships between each hospital characteristic and the odds of adopting at least 8 of the 10 functions.

RESULTS

Adoption

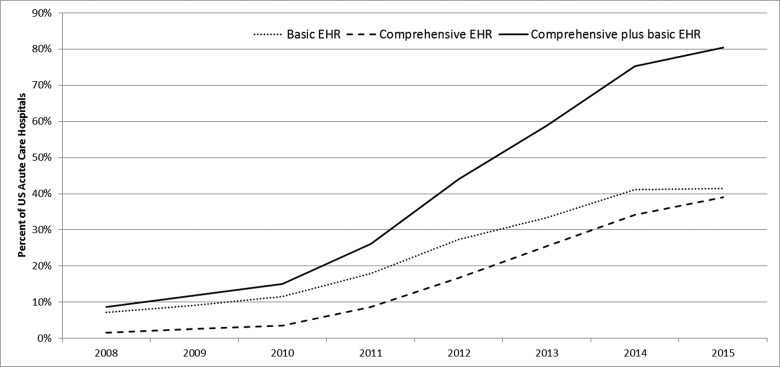

A total of 80.5% of US hospitals had adopted at least a basic EHR in 2015, an increase of 5.3 percentage points from 2014 (75.2%) (Figure 1). Basic EHR adoption increased very slightly, from 41.1% in 2014 to 41.4% in 2015, while comprehensive EHR adoption levels rose from 34.1% to 39.1%.

Figure 1.

Electronic health record (EHR) adoption trends in US hospitals, 2008–2015.

Adoption by hospital type

EHR adoption levels varied across all key hospital characteristics (Table 1). Hospitals participating in both an ACO and PCMH had the highest level of comprehensive EHR adoption (58.9%), while for-profit hospitals had the lowest level (23.8%). In our multinomial model, 2 characteristics were independently associated with adoption of a basic EHR: private for-profit hospitals were more likely than private not-for-profit hospitals to have achieved this level of adoption, while hospitals only participating in ACOs were less likely to have done so (Supplementary Table S2). In contrast, many characteristics were associated with a greater likelihood of adopting a comprehensive EHR. Larger hospitals, private not-for profit hospitals, urban hospitals, hospitals located outside the Northeast, and hospitals participating in reform efforts were all more likely to have adopted a comprehensive EHR. Our 2 proxy measures of safety-net status were not related to either basic or comprehensive EHR adoption (Supplementary Table S2).

Table 1.

Hospital adoption of comprehensive, basic, and less than basic EHR systems, by key hospital characteristics, 2015

| Hospital characteristic | Comprehensive EHR (%) | Basic EHR (%) | Less than basic EHR (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| All | 39.1 | 41.4 | 19.5 |

| Bed size | |||

| Small (0–100) | 33.7 | 42.6 | 23.7 |

| Medium (100–399) | 41.8 | 41.9 | 16.4 |

| Large (400+) | 55.3 | 33.8 | 10.9 |

| Teaching status | |||

| Teaching hospital | 47.6 | 38.1 | 14.2 |

| Non-teaching hospital | 35.7 | 42.7 | 21.6 |

| Ownership | |||

| Not-for-profit | 46.8 | 35.3 | 17.8 |

| For-profit | 23.8 | 58.1 | 18.1 |

| Public | 29.5 | 45.7 | 24.8 |

| Location | |||

| Urban | 44.5 | 39.7 | 15.8 |

| Rural | 31.7 | 43.7 | 24.6 |

| Region | |||

| Northeast | 36.2 | 43.5 | 20.4 |

| Midwest | 46.2 | 34.4 | 19.5 |

| South | 45.3 | 35.2 | 19.5 |

| West | 37.4 | 43.6 | 19.1 |

| Critical access status | |||

| Yes | 31.5 | 44.0 | 24.6 |

| No | 42.3 | 40.4 | 17.4 |

| Disproportionate-share hospital quartile | |||

| 1 (lowest) | 44.9 | 37.9 | 17.3 |

| 2 | 41.9 | 41.8 | 16.3 |

| 3 | 41.1 | 42.9 | 16.0 |

| 4 (highest) | 40.8 | 39.6 | 19.5 |

| Payment reform participation | |||

| No payment reform participation | 32.7 | 44.5 | 22.8 |

| Only ACO participation | 53.5 | 27.1 | 19.4 |

| Only PCMH participation | 50.5 | 34.2 | 15.3 |

| Both ACO and PCMH participation | 58.9 | 31.4 | 9.7 |

Notes: N = 2803. Results are weighted so that they are nationally representative.

Barriers to EHR adoption

Ongoing costs (62% of hospitals), obtaining physician cooperation (58%), and up-front costs (52%) were the most prevalent barriers to adoption reported by hospitals (Supplementary Table S3). When we examined barriers by hospital type – location and size – we found that rural hospitals were more likely to report up-front and ongoing costs and obtaining physician cooperation as barriers compared to their urban counterparts. Small hospitals were more likely to report the 2 cost-related barriers compared to medium and large hospitals.

Advanced EHR functions: EHR data for performance measurement

There was substantial variation in the proportion of hospitals engaged in each of the 10 uses of EHR data to support performance measurement (Table 2). The most prevalent use was to monitor patient safety (71.4% of hospitals), followed by support a continuous improvement process (71.1%), create a dashboard of organizational performance (68.1%), and create individual provider performance profiles (59.0%). Creating an approach for clinicians to query EHR data was the least prevalent (39.8%). In all, 23.8% of hospitals adopted all 10 functions, while 4.9% adopted none; 37.5% of hospitals adopted at least 8 functions (Supplementary Table S4).

Table 2.

Hospital adoption of advanced EHR functions: performance measurement and patient engagement, 2015

| EHR data for performance measurement | ||

| Hospital uses EHR data to: | Yes (%) | No (%) |

| Monitor patient safety (eg, adverse drug effects) | 71.4 | 28.6 |

| Support a continuous quality improvement process | 71.1 | 28.9 |

| Create a dashboard of organizational performance | 68.1 | 31.9 |

| Create individual provider performance profiles | 59.0 | 41.0 |

| Generate reports to inform strategic planning | 58.1 | 41.9 |

| Create a dashboard of unit-level performance | 56.9 | 43.1 |

| Identify high-risk patients for follow-up care using algorithm or other tools | 52.6 | 47.4 |

| Assess adherence to clinical practice guidelines | 51.9 | 48.1 |

| Identify gaps in care for specific patient populations | 47.2 | 52.8 |

| Create an approach for clinicians to query the data | 39.8 | 60.2 |

| All of the above | 23.8 | 76.2 |

| Patient engagement | ||

| Patients have the ability to: | Yes | No |

| View their health/medical data online | 95.1 | 4.9 |

| Download information from their health/medical record | 86.8 | 13.2 |

| Designate a family member or caregiver to access information on their behalf (ie, proxy access) | 81.3 | 18.7 |

| Request an amendment to change/update their health/medical record | 76.9 | 23.1 |

| Pay bills online | 73.3 | 26.7 |

| Electronically transmit (send) care/referral summaries to a third party | 71.3 | 28.7 |

| Use secure messaging with providers | 62.5 | 37.5 |

| Schedule appointments online | 43.1 | 56.9 |

| Request refills for prescriptions online | 41.7 | 58.3 |

| Submit patient-generated data (eg, blood, glucose, weight) | 36.7 | 63.3 |

| All of the above | 15.4 | 84.6 |

Notes: N = 2730. Results are weighted so that they are nationally representative.

In our logistic regression, several hospital characteristics were associated with adoption of at least 8 functions (Table 3). Hospitals with a basic (OR = 1.37; P = .02) or comprehensive (OR = 4.33; P < .01) EHR system were more likely to have adopted at least 8 functions compared to those with less than a basic EHR. Private for-profit hospitals (OR = 0.33; P < .001) and public hospitals (OR = 0.71; P < .001) were less likely to have adopted at least 8 functions compared to private not-for-profit hospitals. CAHs were also less likely to have these advanced functions (OR = 0.58; P < .001). Finally, participating in one or both reform programs was positively associated with adoption of at least 8 advanced functions: only ACO (OR = 1.55; P < .001), only PCMH (OR = 1.74; P < .001), or both (OR = 3.07; P < .001).

Table 3.

Hospital characteristics associated with adoption of advanced EHR functions, 2015

| Hospital characteristics | 8–10 performance measurement functions adopted |

8–10 patient engagement functions adopted |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio | P-value | Odds ratio | P-value | |

| EHR adoption | ||||

| Less than basic EHR | Reference | |||

| Basic EHR | 1.37 | .02 | 3.78 | <.01 |

| Comprehensive EHR | 4.33 | <.01 | 6.84 | <.01 |

| Size | ||||

| <100 beds | Reference | |||

| 100–399 beds | 1.13 | 0.34 | 1.14 | 0.28 |

| ≥400 beds | 1.34 | 0.12 | 1.97 | <0.01 |

| Ownership | ||||

| Private nonprofit | Reference | |||

| Private for-profit | 0.33 | <0.01 | 1.17 | 0.29 |

| Public nonfederal | 0.71 | <0.01 | 0.59 | <0.01 |

| Teaching status | ||||

| Non-teaching hospitals | Reference | |||

| Teaching hospitals | 1.25 | 0.06 | 1.23 | 0.09 |

| Location | ||||

| Urban | Reference | |||

| Rural | 0.83 | 0.13 | 0.87 | 0.25 |

| Region Northeast | Reference | |||

| Region Midwest | 1.71 | <0.01 | 2.06 | <0.01 |

| Region South | 1.47 | 0.01 | 1.84 | <0.01 |

| Region West | 0.79 | 0.16 | 1.63 | 0.04 |

| Safety-net status | ||||

| Not critical access | Reference | |||

| Critical access | 0.58 | <0.01 | 0.68 | 0.02 |

| DSH quartile 1 (lowest) | Reference | |||

| DSH quartile 2 | 0.99 | 0.93 | 0.89 | 0.42 |

| DSH quartile 3 | 0.98 | 0.88 | 0.71 | 0.02 |

| DSH quartile 4 (highest) | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.43 | <0.01 |

| Payment reform participation | ||||

| Neither ACO nor PCMH participation | Reference | |||

| Only ACO participation | 1.55 | <0.01 | 2.14 | <0.01 |

| Only PCMH participation | 1.74 | <0.01 | 2.14 | <0.01 |

| Both ACO and PCMH participation | 3.07 | <0.01 | 3.13 | <0.01 |

Notes: N = 2730. Results are weighted so that they are nationally representative. Bold indicates statistically significant relationships at the p<0.05 level.

Advanced EHR functions: patient engagement

Of the 10 patient engagement functions, hospital adoption ranged from 36.7% to 95.1% (Table 2). Patients’ ability to view their health/medical data online was the most prevalent (95.1% of hospitals), followed by the ability to download information from their health/medical record (86.8%) and the option to designate a family member or caregiver to access information on their behalf (81.3%). Ability to submit patient-generated data was the least prevalent function (36.7% of hospitals). In all, 15.4% of hospitals had adopted all 10 patient engagement functions and 2.7% had adopted none; 41.7% of hospitals had adopted at least 8 functions (Supplementary Table S4).

In our logistic regression, hospitals with a basic (OR = 3.78; P < .001) or comprehensive (OR = 6.84; P < .001) EHR were again more likely to have at least 8 patient engagement functions compared to hospitals with less than a basic EHR (Table 3). Hospitals located in the Midwest (OR = 2.06; P < .001), South (OR = 1.84; P < .001), or West (OR = 1.63; P = .04) were also more likely to have at least 8 patient engagement functions compared to those in the Northeast. Public hospitals (OR = 0.59; P < .001) were less likely to have adopted at least 8 patient engagement functions. CAHs (OR = 0.68; P = .02) and hospitals in the third (OR = 0.71, P = .02) and fourth (OR = 0.43; P < .001) quartile of the DSH index were also less likely to have adopted at least 8 patient engagement functions. Finally, reform participation was positively associated with adoption of all patient engagement functions, including hospitals in an ACO (OR = 2.14; P < .001), a PCMH (OR = 2.14; P < .001), or both (OR = 3.13; P < .001).

DISCUSSION

Our study continues to track progress toward nationwide EHR adoption among US hospitals and introduces new measures that are likely more critical to track moving forward, because they capture advanced uses of EHRs. In terms of at least basic EHR adoption, we observed a small but meaningful increase of 5.3 percentage points. While this is a slowdown after several years of double-digit annual gains, if this rate persists (which is reasonable to assume, given that it is similar to pre–Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act [HITECH] adoption rates), the country should reach 100% adoption in 4 more years. In the first national data on adoption of advanced functions that facilitate improved performance measurement and patient engagement, we found that about one-quarter of hospitals are engaged in all performance measurement functions and 15% are engaged in all patient engagement functions. Of concern, CAHs were less likely to be engaged in at least 8 of each set of functions. This suggests the emergence of a digital “advanced use” divide that may require new policy efforts to ensure that all hospitals translate EHR adoption into improved patient outcomes.

Our EHR adoption results reveal that, while levels continued to rise and are now above 80% for adoption of at least a basic EHR, there are several potential obstacles on the path to 100% adoption. First, the hospitals that are still not using an EHR with basic functions have to progress to at least basic EHR adoption. We found no clear set of characteristics that defines this group, making it difficult to target assistance efforts. Second, when we observed differences in adoption level by hospital type, much of the difference was driven by lower levels of comprehensive EHR adoption, notably among rural and small hospitals. These results suggest a distinct set of barriers impeding progress from basic to comprehensive EHRs. If advancing to comprehensive adoption is a national policy goal, it will likely require new support, specifically for resource-constrained hospitals.

Our results on the adoption of advanced EHR functions tell a mixed story. On the one hand, certain valuable functions were widely adopted. More than 70% of hospitals reported using EHR data to monitor patient safety and support continuous quality improvement. Adoption of patient engagement functions was even higher, with 3 functions adopted by >80% of hospitals (viewing data online, downloading data, and designating family/caregiver access to information); these functions top the list likely because they are included in meaningful use. However, certain valuable functions were not widely adopted. Only about half of hospitals use EHR data to identify high-risk patients, assess adherence to clinical guidelines, and identify gaps in care for specific patient populations. Only about one-third of hospitals allow submission of patient-generated health data.

Hospital characteristics associated with adoption of advanced functions suggest that resources, IT capabilities, and performance incentives are potentially important drivers. While we do not observe the underlying mechanisms, it is likely that performance incentives coming from payment reform programs create the business need, particularly for performance measurement and leveraging EHR data for secondary purposes. Unfortunately, as reported in other studies,18–20 many hospitals face challenges in turning EHR data into meaningful performance measures – the IT capabilities can be expensive, and substantial organizational resources are often required to clean and analyze the data. Our results suggest that those IT capabilities and organizational resources may serve as enablers that allow hospitals to respond to new performance incentives. That these IT and organizational capabilities may be lacking among safety-net providers is interesting, given that we did not find that safety-net status was associated with EHR adoption level (ie, no digital adoption divide). It suggests that the IT and organizational capabilities necessary to support advanced use may be distinct from those required for EHR adoption, and safety-net providers may be specifically struggling to obtain the former.

LIMITATIONS

Our study has several limitations. Although the survey achieved a high response rate and we used a model to adjust for potential nonresponse bias, these adjustments may not have been perfect. Second, we used self-reported survey data and were not able to verify the accuracy of the responses. However, data from the AHA Annual Survey IT Supplement have been validated against other sources21 and routinely used to assess national EHR adoption. Third, survey questions about the adoption of functions related to EHR data for performance measurement and patient engagement were binary. We therefore were not able to account for the extent of use of those functions. Finally, we were not able to assess causal mechanisms underlying the relationships between hospital characteristics and levels of EHR and adoption of advanced functions.

Policy implications

Our results suggest the need for policy efforts that continue to push toward 100% EHR adoption and, in parallel, add a focus on adoption of advanced functions. Given the prevalence of cost-related barriers to EHR adoption, it will be important to ensure that adoption of advanced functions is affordable. If so, group purchasing arrangements and implementation collaboratives (to share organizational best practices) could help facilitate this. In addition, more transparency around the resources, including vendor costs, to adopt and use advanced functions could be useful. The 21st Century Cures Act sets up a framework for such transparency, but has not specifically included performance measurement and patient engagement functions. Our findings suggest that specifically including these functions in the metrics pursued under the upcoming act’s transparency efforts could be valuable. Understanding the specific challenges to adoption of advanced functions faced by safety-net hospitals would help target these strategies to their needs.

Such efforts may also be useful as delivery and payment reform efforts mature and hospitals become increasingly motivated to pursue adoption of advanced EHR functions. Using EHR data for performance measurement is a foundational capability for improving quality and reducing cost, and hospitals that lack measurement capabilities fly blind in their efforts to improve. Patient engagement tools are also important, particularly because few reform programs limit patient choice of when and where to seek care. Hospitals therefore need tools to help patients make good decisions, and patient engagement tools will undoubtedly be key to doing this at scale. Therefore, the success of many delivery and payment reform efforts likely rests on hospitals’ ability to effectively adopt and use performance measurement and patient engagement functions. This should further motivate policymakers to pursue approaches to facilitate progress in these areas.

CONCLUSION

Eight years after the passage of HITECH, we continue to look ahead to the goal of nationwide EHR adoption. With 80% of hospitals having adopted at least a basic EHR, the finish line is in sight, but our study helps illuminate potential obstacles that will need to be overcome to cross the finish line. We also present new national data on the adoption of performance measurement and patient engagement functions, creating a baseline from which to track progress. Doing so is particularly critical as health reform efforts mature and hospitals, particularly CAHs, are likely to need affordable, effective ways to adopt these advanced functions in order to facilitate improved performance.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

Competing Interests

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of Health and Human Services.

Funding

None.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary material is available at Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association online.

References

- 1. Blumenthal D. Launching HITECH. N Engl J Med. 2010;3625:382–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Adler-Milstein J, Furukawa MF, Jha AK. et al. Early results from the hospital electronic health record incentive programs. Am J Managed Care. 2013;197:e273–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Adler-Milstein J, DesRoches CM, Kralovec P. et al. Electronic health record adoption in US hospitals: progress continues, but challenges persist. Health Affairs. 2015;3412:2174–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Henry J, Pylypchuk Y, Searcy T. et al. Adoption of Electronic Health Record Systems among US Non-Federal Acute Care Hospitals: 2008-2015. ONC Data Brief. 35:1-9. Washington DC: Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Adler-Milstein J, DesRoches CM, Furukawa MF. et al. More than half of US hospitals have at least a basic EHR, but stage 2 criteria remain challenging for most. Health Affairs. 2014;339:1664–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. DesRoches CM, Charles D, Furukawa MF. et al. Adoption of electronic health records grows rapidly, but fewer than half of US hospitals had at least a basic system in 2012. Health Affairs. 2013;328:1478–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. DesRoches CM, Worzala C, Joshi MS. et al. Small, nonteaching, and rural hospitals continue to be slow in adopting electronic health record systems. Health Affairs. 2012;315:1092–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jha AK, Burke MF, DesRoches CM. et al. Progress toward meaningful use: hospitals' adoption of electronic health records. Am J Managed Care. 2011;17(Spec No.):SP117–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jha AK, DesRoches CM, Kralovec P. et al. A progress report on electronic health records in US hospitals. Health Affairs. 2010;2910:1951–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Baron RJ. Quality improvement with an electronic health record: achievable, but not automatic. Ann Int Med. 2007;1478:549–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Persell SD, Kaiser D, Dolan NC. et al. Changes in performance after implementation of a multifaceted electronic-health-record-based quality improvement system. Med Care. 2011;492:117–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Irizarry T, DeVito Dabbs A, Curran CR. Patient portals and patient engagement: a state of the science review. J Med Internet Res. 2015;176:e148.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ricciardi L, Mostashari F, Murphy J. et al. A national action plan to support consumer engagement via e-health. Health Affairs. 2013;322: 376–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jha AK, DesRoches CM, Campbell EG. et al. Use of electronic health records in US hospitals. New Engl J Med. 2009;36016:1628–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Stange KC, Nutting PA, Miller WL. et al. Defining and measuring the patient-centered medical home. J General Int Med. 2010;256:601–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Berwick DM. Launching accountable care organizations—the proposed rule for the Medicare Shared Savings Program. New Engl J Med. 2011;36416:e32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kalton G, Kasprzyk D. The treatment of missing survey data. Survey Methodol. 1986;121:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cleverley WO, Cleverley JO. Scorecards and dashboards using financial metrics to improve performance: the balanced scorecard and its natural subset, the dashboard, can help keep you focused on the critical areas that affect your hospital's overall performance. Healthc Financial Manag. 2005;597:64–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. American Hospital Association. Hospitals Face Challenges Using Electronic Health Records to Generate Clinical Quality Measures. 2013. Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Brown DS, Aydin CE, Donaldson N. Quartile dashboards: translating large data sets into performance improvement priorities. J Healthc Qual. 2008;306:18–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Everson J, Lee S-YD, Friedman CP. Reliability and validity of the American Hospital Association's national longitudinal survey of health information technology adoption. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014;21(e2):e257–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.