Abstract

Background:

Cardiovascular electronic consultation is a new service line in consultative medicine and enables care without in-person office visits. We aimed to evaluate accessibility and time saved as measures of efficiency, determine the safety of cardiology electronic consultations, and assess satisfaction by responding cardiologists.

Methods:

Using a mixed-methods approach and a modified time-driven, activity-based, costing framework, we retro-spectively analysed cardiology electronic consultations. A random subset of 500 electronic consultations referred between 2013–2017 were reviewed. Accessibility was determined based upon increased number of patients served without the need for an in-person clinic visit. To assess safety, medical records were reviewed for emergency room visits or hospital admission at six months from the initial electronic consultation date. Responding cardiologist satisfaction was assessed by voluntary completion of an online survey.

Results:

The majority of electronic consultations were related to medication advice, clearance for surgery, evaluation of images, or guidance after abnormal testing. Recommendations included echo (10.8%), stress testing (5.0%), other imaging (4.0%) and other subspecialist referrals (3.8%). Electronic consultations were completed within 0.7±0.5 days of the request, with a time to completion of 5–30 min. Over a six-month follow-up, 13.9% of patients had an in-person visit and 2.2% of patients were hospitalised, but none were directly related to the electronic consultation question. Satisfaction by responding cardiologists was modest.

Conclusion:

In conclusion, within a single-payer system, cardiology electronic consultations represent a convenient and safe alternative for providing consultative cardiovascular care, but further optimization is necessary to minimise electronic consultation fatigue experienced by cardiologists.

Keywords: Electronic consultation, cardiology, specialty care, veterans

Introduction

In recent years, the need to control healthcare costs and availability of technology paved way for telemedicine. Although ‘curbside’ consultations have always existed, the rise of electronic consultations (e-consults) formalised the process and created a new service line for delivery of consultative medicine.1,2 Since the 1960s,3,4 the United States Veteran’s Health Administration (VHA) has been piloting telehealth technology and developing programmes to improve patient care and access,5 particularly in rural areas.6 The VHA is one of the largest integrated, single-payer healthcare systems in the USA with >9 m constituents.7 While much of the VHA’s telehealth efforts have focused on mental health and primary care, a shortage of specialised physicians and need for access and rational triage gave birth to subspecialty e-consults.8,9

The e-consult programme within VHA9,10 and other healthcare systems2,11,12 is intended to efficiently enable communication between primary care clinicians and specialists using the electronic medical record (EMR), without the necessity of in-person clinic visits.8 All information utilised by the specialist to answer the clinical question posed by the primary care clinician is acquired from the EMR through chart review. Several single-centre observational studies have demonstrated benefits including increased speed of communication, time and resources saved for both patients and the healthcare system, and user satisfaction.13,14 Since cardiovascular patients tend to be complex and e-consult questions may be time-sensitive, safety becomes a frequent concern. Moreover, while efficiency of telemedicine has been reported, consultant time and satisfaction have not been assessed. Using a mixed-methods approach with time-driven activity-based costing (TDABC), the aims of this study were to assess the value of cardiology e-consults in a single-payer system through measures of efficiency, safety and consultant satisfaction.

Materials and methods

Participants and framework

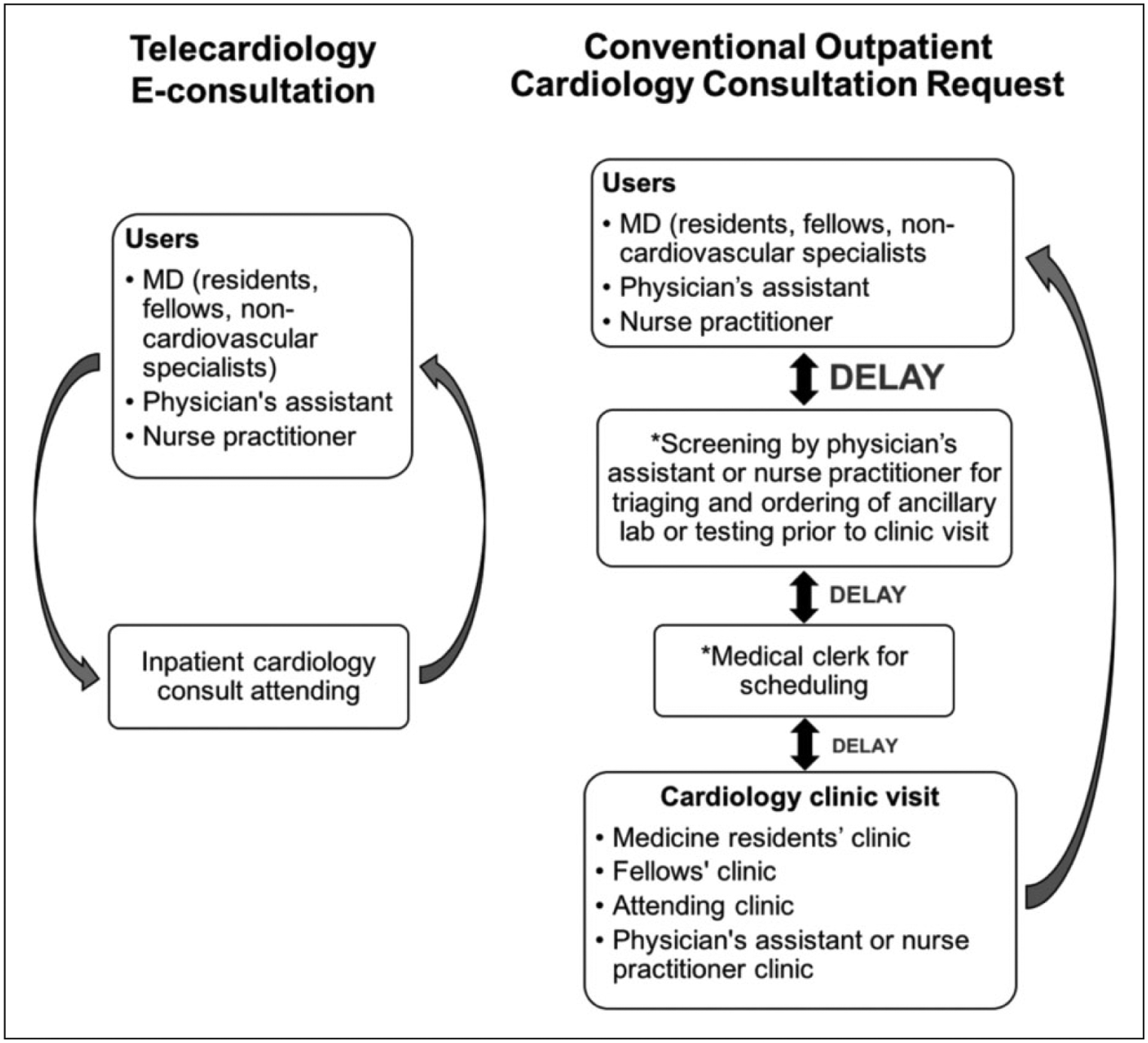

The project was reviewed by the local Institutional Review Board and was deemed to be exempt. Follow-up review of medical records was performed (ALN, BSB) for quality improvement and to ensure safety for the new service line. We used a mixed-methods analytical approach,15,16 which included a combination of quantitative and supplemental qualitative data to iteratively enhance the understanding of patterns observed. We defined value in the context of efficiency or accessibility (the quality of being easy to obtain) and time saved, safety and consultant satisfaction. Safety was reflected in the six-month adverse event rate for hospitalization (or emergency room visit) directly related to the e-consult question. We applied a TDABC framework17,18 to assess cost savings in the context of efficiency by comparing the care delivery value chain (CDVC) for cardiovascular e-consults vs conventional in-person, office-based cardiovascular consultative clinic visits (Figure 1). The TDABC framework was utilised as the costing method due to its ability to lever-age units of time, as opposed to individual costs, and to better reflect the multiple drivers of total cost through the CDVC. Because cardiovascular e-consults stream-lined multiple processes (obviated the cost for ancillary personnel at two different steps of the CDVC, and reduced resource costs to time spent by consulting cardiologists), all seven steps of TDABC were not applied.18

Figure 1.

Comparison of workflow between telecardiology e-consultation (left) and conventional in-person clinic referral (right) in the cardiovascular care delivery value chain (CDVC). CDVC is a framework that conceptualises the organization and structure of care delivery for various medical conditions. In some cases, conventional in-person cardiology consultations are converted to e-consults and vice-versa. E-consultation mitigates third-party ancillary processes (*), which streamlines the communication between users (primary care team) and cardiology consultants. MD: medical doctor.

Setting

The VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System provides both inpatient and outpatient care services and is composed of the VA West Los Angeles Medical Center (WLAMC; a tertiary referral centre), two free standing ambulatory care centres, and eight surrounding community clinics. VA WLAMC is affiliated with multiple academic centres and hosts medical trainees from affiliated healthcare institutions. The Division of Cardiology consists of 10 full-time cardiologists, three part-time cardiologists, and two part-time nurse practitioners. All attending cardiologists rotated on the inpatient cardiology consultation service and sub-specialization included general cardiology, interventional cardiology, cardiovascular imaging and clinical cardiac electrophysiology. The e-consult programme began in 2013. Between 2013–2017, a total of 4833 e-consults were sent to the Cardiology Division at VA WLAMC. Figure 1 outlines the workflow for cardiology e-consults compared to conventional in-person consultations. Any person with ordering privileges may submit an e-consult to cardiology.

Quantitative analysis

Quantitative characteristics of the cardiology e-consults were extracted from the electronic medical records by two independent reviewers (ALN, BSB) according to pre-specified variables needed for the evaluation of e-consults. Both reviewers had no vested interest in the outcome of the e-consult service line. A list of all e-consults received over the four-year study period (n = 4833) was provided to the reviewers who were blinded to all detail regarding the encounters; a total of 500 e-consults were randomly chosen by the reviewers for detailed chart review. From the 500 e-consults, we collected the following data: common consult questions, diagnoses based on international classification of diseases, 9th revision (ICD-9) codes, recommended tests and other consultations, time spent, follow-up visits and/or hospitalizations within six months of the e-consult request. These data were used to iteratively improve the service line. Workload credit used for resource allocation was based on self-reported time spent (as a reflection of patient complexity, time, and risk) and were divided into <15 min, 15–30 min, 30–45 min, and >45 min. The time duration corresponded to an outpatient case complexity typically used for documentation of work-relative value units (wRVUs) based upon the 2017 revised physician fee schedule per the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS): Level 2 (1.34 wRVU), Level 3 (1.88 wRVU), Level 4 (3.02 wRVU) and Level 5 (3.77 wRVU) visits. Accessibility was based upon increased number of patients served in lieu of an in-person clinic visit. Measures of efficiency included time-saved and costing analysis based on updated wRVU equivalents for potential in-person specialty clinic visits. Date and time stamps from the signature of the requesting service and the responding consultant were used to determine time to completion. Time-saved was determined by comparing the average elapsed time duration for completion of an e-consult with the conventional wait time for an in-person appointment. To assess short-term safety, medical records were reviewed for in-person clinic visits and/or inpatient hospitalizations occurring within the six-month window of the e-consult. Any subsequent in-person clinic visits or hospitalizations directly related to the e-consult question were reviewed and documented.

Qualitative analysis

To qualitatively assess the overall impression of the e-consult programme and consultant satisfaction, an electronic survey (SurveyMonkey, San Mateo, California, USA) consisting of six questions was sent to attending cardiologists who regularly served on the inpatient consult service (n=13). Survey questions were:

I am satisfied with the cardiology e-consult programme.

E-consult is a time burden that is not reflected in the workload and/or detracts from other duties and obligations.

The types of clinical questions asked with an e-consult are generally appropriate.

The e-consult programme minimised inappropriate traditional ‘in-person’ consult referrals.

The e-consult programme improved access to cardiovascular consultative care.

Survey participants were asked to respond to each question as definitely true, mostly true, mostly false or definitely false. Participants were able to provide free text comments at the end of the survey, which were also reviewed. Participation in the survey was voluntary.

Results

Patient characteristics

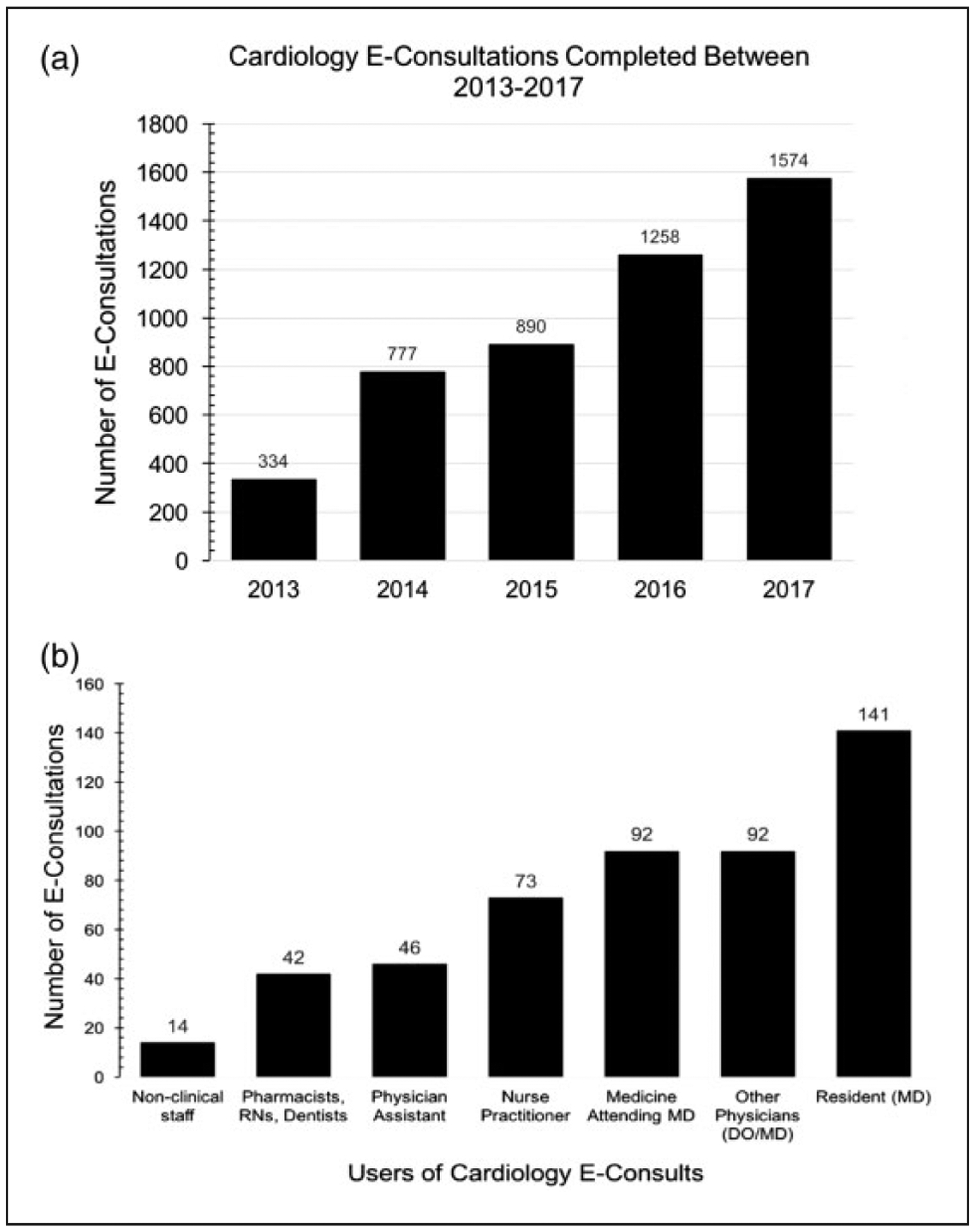

A total of 4833 e-consults were received from 2013–2017 (Figure 2(a)). The patients were predominantly male (95.8%, 479/500) and between the age of 24–96 years (64±12 years). By 2017, the number of cardiology e-consults received was five times the number of e-consults from 2013. The background of persons requesting cardiology e-consults and the volume of e-consults are illustrated in Figure 2(b). Cardiology e-consults were also used by both by non-clinicians who had ordering privileges and by clinicians for administrative questions (e.g. ‘we cannot find the Holter report’).

Figure 2.

Number of cardiology e-consultations between 2013–2017 and users of cardiology e-consultations. Bar graphs display (a) the total number of cardiology e-consultations between 2013 and 2017 and (b) user frequency of cardiology e-consultations. Non-clinical staff consisted of clinical specialists, social workers, clinic/centre clerks and other personnel from preventive medicine. DO: doctor of osteopathic medicine; MD: medical doctor; RN: registered nurse.

E-consult diagnoses and specialist recommendations

Table 1 summarises the most common diagnoses for cardiology e-consults. Based on ICD-9 codes, the three most frequent diagnoses were essential hypertension, dyslipidaemia and atrial fibrillation. Consult questions ranged from diagnostic to therapeutic including medication recommendations (initiation, change, continuation and/or discontinuation), clearance for dental work and/or other surgical procedures, evaluation of imaging findings and guidance on how to proceed with abnormal test results. Less than 5% of e-consults pertained to administrative requests (e.g. ‘Where is the echo report?’). Of the e-consults analysed, 78.8% (394/500) did not result in additional testing. In 21.2% (106/500) of consults, one or more subsequent tests or referrals were ordered: 54 echocardiograms (10.8%), 25 stress tests (5%), 20 other imaging tests (4%) and 19 referrals to other subspecialists (3.8%).

Table 1.

Summary of most common diagnoses by ICD-9 codes associated with cardiology e-consultations.

| ICD-9 codes | Diagnosis | Frequency (%) | In-person clinic visit (%) | Hospitalization (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICD-9-CM 401.9 | Unspecified essential hypertension | 136 (27.2%) | 4 (0.8%) | 1 (0.2%) |

| ICD-9-CM 414.9, 414.00 | Coronary artery disease | 106 (21%) | 18 (3.6%) | 3 (0.6%) |

| ICD-9-CM 272.4 | Dyslipidaemia | 90 (18.0%) | – | – |

| ICD-9-CM 427.31 | Atrial fibrillation | 68 (l3.6%) | 11 (2.2%) | 1 (0.2%) |

| ICD-9-CM 250.00 | Diabetes mellitus without mention of complication, type II or unspecified type, not stated as uncontrolled | 38 (7.6%) | – | – |

| ICD-9-CM 428.0, 425.4 | Congestive heart failure; other cardiomyopathies | 37 (7.4%) | 31 (6.2%) | 6 (1.2%) |

| ICD-9-CM 427.89 | Bradycardia | 20 (4.0%) | 2 (0.4%) | – |

| ICD-9-CM 786.50 | Chest pain NOS - unspecified chest pain | 19 (3.8%) | – | – |

| ICD-9-CM 305.1 | Smoker | 18 (3.6%) | – | – |

| ICD-9-CM 278.00 | Obesity | 17 (3.4%) | – | – |

| ICD-9-CM 424.1 | Aortic valve disorders | 17 (3.4%) | 4 (0.8%) | – |

| ICD-9-CM V58.61 | Long term (current) use of anticoagulants | 16 (3.2%) | – | – |

E-consult time and costing data

The majority of e-consults were completed within 24 h of request (0.7±0.5 days). The amount of time spent completing an e-consult ranged from 15–55 min (34.5±7.5 min). Over the same study period, the wait time for a traditional in-person clinic visit was: 5.2±2.7 days (2014), 9.2±4.7 days (2015), 15.2±7.5 days (2016) and 13±7.5 days (2017). Billing for conventional clinic visits typically account for complexity of the consult question, number of problems addressed, time and risk. Within the sampled population, there were 50 (10%) Level 5 in-person equivalent consultations, 375 (75%) Level 4 consultations, and 75 (15%) Level 3 consultations. Based on the 2017 outpatient wRVUs from the National Physician Fee Schedule, the potential reimbursement equivalent for outpatient consultation visits (500 of total 4833 e-consults received) was US$9241 (Level 5 consults), US$55,987.50 (Level 4 consults), and US$6971.25 (Level 3 consults). If cardiology consultations were billable (reimbursable), the amount of revenue generated by the cardiology e-consults was approximately US$73,000 for the 500 e-consults (~10.3% of total e-consults). By extrapolation, this could equate to ~US$800,000 of revenue for the four-year study period or ~US$200,000 per year of additional revenue.

Safety

Within six months after completion of the e-consult, 70 patients (13.9%) required an in-person cardiology clinic visit indirectly related to the problem addressed in the e-consult. Moreover, 11 patients (2.2%) required inpatient hospitalization due to progression of their disease. Of the patients that required hospitalization, the underlying problem was congestive heart failure (n=6), coronary artery disease (n=3), atrial fibrillation n=1) and hypertension (n=1).

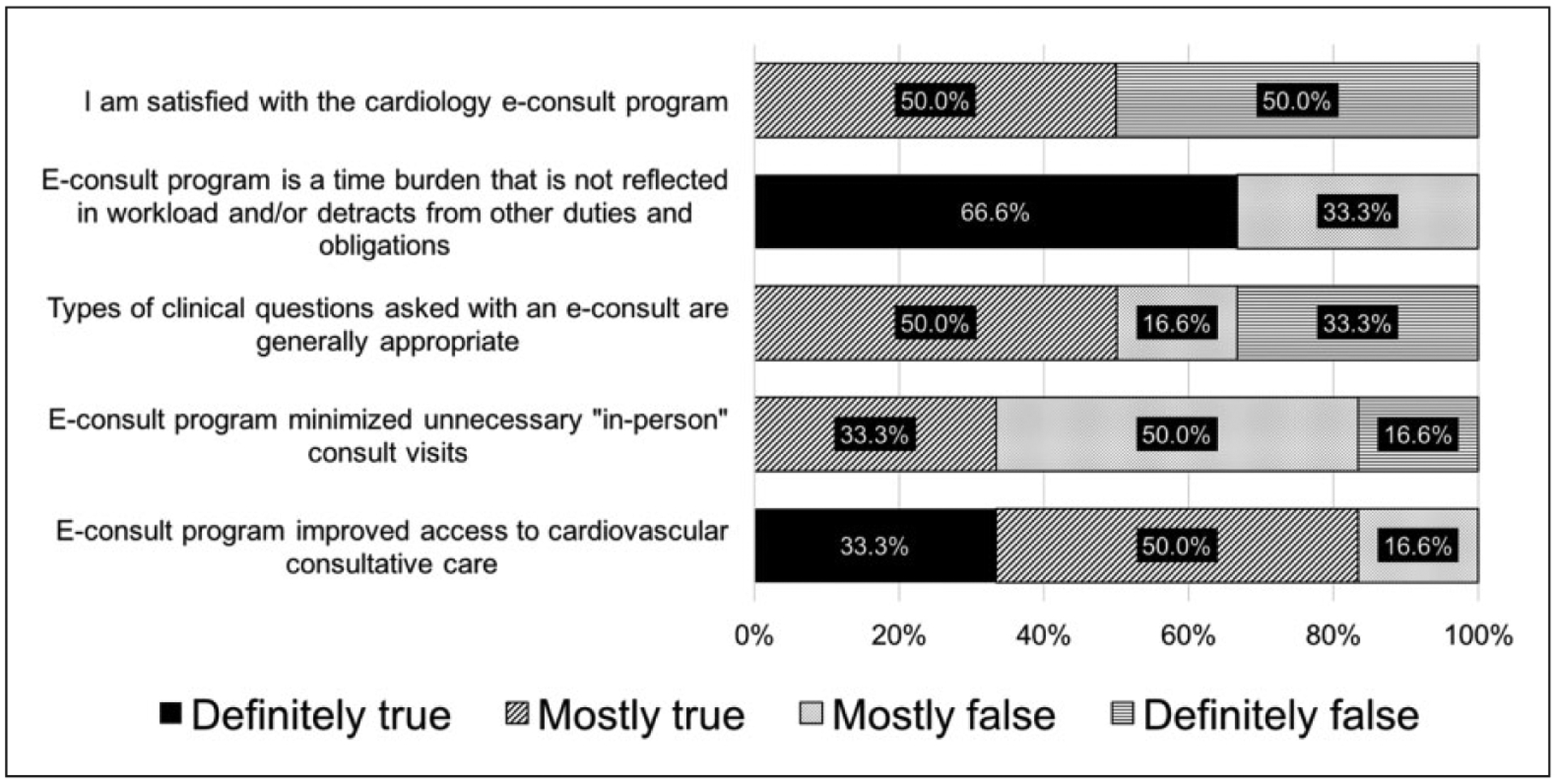

Respondent specialist satisfaction

Of the faculty members available to be surveyed (n=13), two of the faculty members were excluded due to a conflict of interest related to the study design and involvement in the administration of e-consults within the cardiology division. A total of six included faculty members voluntarily completed the questionnaire. Three cardiologists provided additional free-text comments. Figure 3 illustrates the distribution of the survey data. Preliminary survey data results suggested ambivalence about the overall impression of the e-consult programme; at the same time, satisfaction by consultants was equivocal. The majority felt that e-consults increased veterans’ access to cardiovascular consultative care. The sentiments were more negative when it came to minimization of unnecessary in-person visits. Most felt that e-consult questions were appropriate. However, e-consults were viewed as a time burden because the cardiologists completed e-consults on top of their normally designated work. Consultant cardiologists felt the time spent detracted from other duties while on the inpatient consult service. When correlated with the billing service level of the e-consult, the additional time burden coincided with an average increase of at least 69 additional hours per cardiologist per year for 2017 (1574 e-consults in 2017 × assume minimum average 34 min per e-consult=53,516 min/60 min=892 h/13 cardiologists=69 h per cardiologist). Consultants felt that documentation using the current EMR system was complex and inefficient, and contributed to the time burden.

Figure 3.

Survey responses from cardiology consultants (n=6).

Discussion

Using a modified TDABC, our findings demonstrate that e-consults improved the efficiency of cardiovascular consultative medicine and short-term safety was acceptable. A small percentage (2.2%) of our patients were hospitalised within six months, but the need for hospitalization was due to natural progression of the condition and unrelated to a delay in care. Preliminary results on satisfaction by cardiology consultants were equivocal and there was concern about the additional time burden. On average, each cardiologist spent at least 69 additional hours per year answering e-consults in 2017. Compared to reports from multi-payer healthcare systems, where consultants were incentivised through additional compensation, in a single-payer healthcare system without additional compensation, e-consults were perceived as an additional clinical responsibility and time burden. While the results of our study substantiated the findings by Wasfy et al., our work provides additional preliminary assessment of value from the perspective of the consultants. Practice patterns and short-term safety outcomes in our study were similar to those within multi-payer systems.11,19 The average time spent completing e-consults was 34.5±7.5 min; the majority were completed within one day (0.7±0.5 days). The faster response time contributed to time saved and improved the overall efficiency of cardiology consultation within the CDVC.20 Patients benefited by not having to wait for an in-person appointment, which may range from 1–6 months nationally;21,22 our local wait time ranged from 5–15 days. Reduced in-person visits also diminished the need and cost for transportation, which can be a particular problem for elderly veterans23 and those living far from the medical centre.

Although recent interest in e-consult programmes relates to cost-savings, the other facet is potential revenue generation and resource reallocation. Our study was limited by the use of e-consult equivalent levels of reimbursement in the context of a TDABC framework. We calculated a potential revenue of US$73,000, which accounted for only 10.3% (500/4833) of the total number of e-consults. Our estimated costs (or potential revenue) was consistent with those found by colleagues in Eastern Ontario, Canada.24 In a single-payer system, revenue generation may be less significant than the indirect consequences of implementing a cardiology e-consult service. One notable effect is enabling the in-person clinic visit to be saved for more complex patients or those who truly require an in-person assessment. For both patients and systems, an in-person clinic visit is a scarce and costly resource. While future studies may consider using TDABC to compare the value of e-consult programmes across a spectrum of healthcare settings, within the larger value equation, intangible benefits may be gleaned from the types of questions asked through e-consult use, which merit further investigation.

The qualitative findings of our study mirrored those described by Gupte et al.10 Most notable was the common unintended use of e-consults for administrative questions, thereby filling an unmet gap of administrative support. While others have proposed that e-consults may facilitate avoidance of appropriate vs inappropriate subspecialty referrals,2 we did not systematically assess the appropriateness of the e-consult question. Although the workload is accounted for based on the time spent, the lack of resource reallocation lessened the enthusiasm among consulting cardiologists. Cardiology e-consults were viewed as additional tasks on an already full plate, and may potentially contribute to increased dissatisfaction among consulting physicians. Although we expected clinic wait time to improve, the average clinic wait time increased between 2014 and 2017, which may be reflect veterans seeking care as a result of new insurance regulations.

Our study has several limitations. First, this study was a single centre analysis within an integrated healthcare system, which limits the generalisability to single-payer systems. Geography, subspecialty services and local operational framework may also differ from other systems. Because the sampling timeframe was limited to the first three years, discontent among consultants may relate to growing pains during the early years of implementation and lack of programme optimization based upon consulting physician feedback. The growing volume of cardiology e-consults may also be specific to teaching hospitals where trainees/non-specialists may use e-consults more frequently because they are convenient, readily available and without cost to the user other than the time spent entering the e-consult request. Second, we did not assess satisfaction of the requesting service because many publications have established a high level of satisfaction by patients and requesting clinicians.11,23,25 Third, the safety results may reflect a selection bias by primary care clinicians. In deciding to place an e-consult, the primary care clinicians would need to make judgement calls about the nature and acuity of the questions and serve as the initial gatekeepers of safety. Finally, it is challenging to generate an accurate cost-savings analysis when wRVU-based equivalents are used to compare e-consults with in-person visits, but we provided estimates for context. Indeed, physician time is perhaps the most limited of all resources in the cardiovascular care delivery value chain. If cost-savings are viewed only from the standpoint of physician time, then the e-consult shifted physician time from ‘in-person’ to ‘remote or virtual’ care delivery, but did not necessarily reflect a cost-saving to the healthcare system overall.

Despite a modest sample size, our preliminary survey findings raised a variety of important concerns by responding cardiologists. First, trepidation about appropriateness of the e-consult question could be resolved by improved education of primary care clinicians, which has been demonstrated by the VHA-led specialty care access network-extension for community healthcare outcomes (SCAN-ECHO) project.26Second, e-consults were used to mitigate potential legal implications for questions about prophylactic antibiotics prior to dental procedures, which have a clear set of guidelines provided by the American Dental Association.27 The VHA has been exploring alternatives to increase the number of frontline clinicians with varying ability and skillset. It remains unknown how implementation of alternative models for providing primary care will ultimately affect the overall work satisfaction of specialists, particularly in the case of e-consults, if resources are not reallocated. Dissatisfaction among cardiologists and feelings of increased time burden without commensurate incentives are important topics warranting further study in order to minimise the risk of specialist ‘burnout’. Further studies are also needed to determine the most effective way to encourage widespread adoption and to minimise negative views of e-consults as a burden-some workload.10

Conclusions

Our study, along with others, shows promising results in regard to safety and efficiency of the cardiology e-consult. Faster and more conveniently accessible cardiovascular care can be provided to patients without substantial negative impact. In order to improve specialist satisfaction within the service line, strategies are needed to optimise the implementation of cardiology e-consults.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the faculty members in the Division of Cardiology at the Veterans Affairs West Los Angeles Medical Center for their feedback and participation in the surveys. They would also like to thank Manyee Gee at Veterans Affairs West Los Angeles Medical Center for her assistance with data extraction.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Gatley S, Grace A and Lopes V. E-referral and e-triage as mechanisms for enhancing and monitoring patient care across the primary-secondary provider interface. J Telemed Telecare 2003; 9: 350–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen AH, Murphy EJ and Yee HF Jr. eReferral–a new model for integrated care. N Engl J Med 2013; 368: 2450–2453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wittson CL and Benschoter R. Two-way television: Helping the medical center reach out. Am J Psychiatry 1972; 129: 624–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Godleski L, Nieves JE, Darkins A, et al. VA telemental health: Suicide assessment. Behav Sci Law 2008; 26: 271–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hill RD, Luptak MK, Rupper RW, et al. Review of Veterans Health Administration telemedicine interventions. Am J Manag Care 2010; 16: e302–e310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Broderick A. The Veterans Health Administration: Taking home telehealth services to scale nationally. Commonwealth Fund Pub 1657: 4, https://www.commonwealthfund.org/sites/default/files/documents/___media_files_publications_case_study_2013_jan_1657_broderick_telehealth_adoption_vha_case_study.pdf (2013, accessed 1 January 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 7.U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Restoring trust in veteran’s health care. Fiscal Annual Report, 2016, https://www.va.gov/finance/afr/index.asp (2016, accessed 1 January 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Horner K, Wagner E and Tufano J. Electronic consultations between primary and specialty care clinicians: Early insights. The Commonwealth Fund 2011; 23, https://www.commonwealthfund.org/sites/default/files/documents/___media_files_publications_issue_brief_2011_oct_1554_horner_econsultations_primary_specialty_care_clinicians_ib.pdf (2011, accessed 1 January 2018). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kirsh S, Carey E, Aron DC, et al. Impact of a national specialty e-consultation implementation project on access. Am J Manag Care 2015; 21: e648–e654. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gupte G, Vimalananda V, Simon SR, et al. Disruptive innovation: Implementation of electronic consultations in a veterans affairs health care system. JMIR Med Inform 2016; 4: e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wasfy JH, Rao SK, Chittle MD, et al. Initial results of a cardiac e-consult pilot program. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014; 64: 2706–2707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lai L, Liddy C, Keely E, et al. The impact of electronic consultation on a Canadian tertiary care pediatric specialty referral system: A prospective single-center observational study. PLoS One 2018; 13: e0190247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Angstman KB, Adamson SC, Furst JW, et al. Provider satisfaction with virtual specialist consultations in a family medicine department. Health Care Manag (Frederick) 2009; 28: 14–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim Y, Chen AH, Keith E, et al. Not perfect, but better: Primary care providers’ experiences with electronic referrals in a safety net health system. J Gen Intern Med 2009; 24: 614–619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Creswell J. Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/Merrill Prentice Hall, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tashakkori A and Teddlie C. Mixed methodology: Combining qualitative and quantitative approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaplan RS and Anderson SR. Time-driven activity-based costing. Harv Bus Rev 2004; 82: 131–138, 150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keel G, Savage C, Rafiq M, et al. Time-driven activity-based costing in health care: A systematic review of the literature. Health Policy 2017; 121: 755–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wasfy JH, Rao SK, Kalwani N, et al. Longer-term impact of cardiology e-consults. Am Heart J 2016; 173: 86–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Olayiwola JN, Anderson D, Jepeal N, et al. Electronic consultations to improve the primary care-specialty care interface for cardiology in the medically underserved: A cluster-randomized controlled trial. Ann Fam Med 2016; 14: 133–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abouali J and Stoller J. Electronic consultation services: Tool to help patient management. Can Fam Physician 2017; 63: 135–136. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jaakkimainen L, Glazier R, Barnsley J, et al. Waiting to see the specialist: Patient and provider characteristics of wait times from primary to specialty care. BMC Fam Pract 2014; 15: 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rodriguez KL, Burkitt KH, Bayliss NK, et al. Veteran, primary care provider, and specialist satisfaction with electronic consultation. JMIR Med Inform 2015; 3: e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liddy C, Drosinis P, Deri Armstrong C, et al. What are the cost savings associated with providing access to specialist care through the Champlain BASE eConsult service? A costing evaluation. BMJ Open 2016; 6: e010920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vimalananda VG, Gupte G, Seraj SM, et al. Electronic consultations (e-consults) to improve access to specialty care: A systematic review and narrative synthesis. J Telemed Telecare 2015; 21: 323–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sayre GG, et al. Adopting SCAN-ECHO: The providers’ experiences. Healthc (Amst) 2017; 5(1–2): 29–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.American Dental Association. Oral health topics: Antibiotic prophylaxis prior to dental procedures, https://www.ada.org/en/member-center/oral-health-topics/antibiotic-prophylaxis (accessed 1 January 2018).