Abstract

Current dental sealants with methacrylate based chemistry are prone to hydrolytic degradation. A conventional ethylene glycol dimethacrylate (EGDMA) was compared to a novel methacrylate monomer with a flipped external ester group (ethylene glycol ethyl methacrylate - EGEMA) that was designed to resist polymer degradation effects. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy and water contact angle confirmed a comparable degree of initial conversion and surface wettability for EGDMA and EGEMA. EGDMA disks initially performed better compared to EGEMA as suggested by higher surface hardness and 1.5 times higher diametral tensile strength (DTS). After 15 weeks of hydrolytic and accelerated aging, EGDMA and EGEMA DTS was reduced by 88% and 44% respectively. This accelerated aging model resulted in 3.3 times higher water sorption for EDGMA than EGEMA disks. EGDMA had an increase in grain boundary defects and visible erosion sites with accelerated aging, while for EGEMA the changes were not significant.

1. Introduction

In the last few decades, polymers used in dentistry have been modified with the goal of increasing durability and longevity. Early dental prosthetic materials such as cellulose nitrate, vinyl resins and phenol formaldehyde, were deficient in stability, strength, degradation, and abrasion resistance [1]. The introduction of methacrylate monomers like 1,1,1-trimethylolethane trimethacrylate, 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate (HEMA), diethylene glycol dimethacrylate (DEGDMA), 1,1,1-trimethylolpropane triacrylate, triethylene glycol dimethacrylate (TEGDMA), and urethane dimethacrylate (UDMA) [2] substantially improved the dimensional stability, strength, water absorption, and photo polymerization of materials used in dental prosthetics [3]. To further improve longevity, by increasing overall hardness and strength, while reducing polymer shrinkage that can lead to deleterious outcomes especially in direct restorations, smaller methacrylate monomers were blended with larger, rigid, hydrophobic monomers like Bisphenol A ethoxylate methacrylate (BisEMA) and Bisphenol A glycidyl methacrylate (BisGMA) [4].

BisEMA and BisGMA blends with monomers such as TEGDMA/EGDMA may have improved physical and mechanical properties but are known to undergo decomposition when challenged with acidic, enzymatic, and cariogenic bacterial environments by irreversible hydrolysis of ester bonds [5–7]. While polymer decomposition directly affects material physical and mechanical properties like microhardness as a result of hydrolytic degradation,[8] there are additional concerns about the systemic biocompatibility of degraded by-products [9,10]. There have been reports that enzyme-polymer interactions can lead to by-products like methacrylic acid which can further undergo oxidation leading to production of hazardous formaldehyde [11]. In addition to effects on host tissue, the current methacrylate blends are known to preferentially influence, within in vitro systems, the growth of certain bacterial species, thereby triggering the physical changes in the dental restoration material and facilitate the progression of secondary caries [12]. This sequela may be compounded by the leaching of unreacted (co)monomers and by-products from the hydrolyzed polymer composites [7,13,14]. The developed grain boundary defects from the breakdown of these conventional methacrylate polymers may harbor the additional growth of bacteria [15]. All these changes may lead to clinical failure of the dental material especially at its interface with the tooth [16].

In order to improve the longevity of the polymer structure, researchers have been exploring and incorporating a range of additives in polymers and changing the chemistry of (co)monomers. An ether chemistry based polymer (1,12-Bis(4-vinylphenyl)-2,5,8,11-tetraoxadodecane (TEG-DVBE)) was reported by Gonzalez-Bonet et al. suggesting that the lack of an ester group resulted in an enzymatic and hydrolytic resistive dental resin [17]. In a more recent study, a mixed resin was proposed with ether group monomer ‘triethylene glycol-divinylbenzyl ether (TEG-DVBE)’ along with urethane dimethacrylate (UDMA) as base monomer which were more resistant to hydrolytic degradation and possessed controlled photo-polymerization [18,19]. While the development of ether based dental materials is promising these materials still benefit from the addition of methacrylate based macromers such as TEGDMA or EGDMA as diluents to improve the reaction kinetics of photo-polymerization reaction [20]. Ether-based polymers have notable potential in clinical practice, but there are still development and commercialization challenges ahead.

Recent advances in several other chemistry systems have addressed water sorption stability. Vinyl sulfonamide and thiol based resins polymers have low water sorption and increased toughness when compared to TEGDMA and Bis-GMA based resin [21]. Investigations into Standard Guide for Accelerated Aging of Sterile Barrier Systems for Medical Devices methacrylamide-methacrylate (TEGDMA/HEMA/Bis-GMA) hybrid monomer resins have reported that even though hybrid systems have lower degree of polymerization and polymerization rate these hybrid systems performed better in long term dentin bonding, storage modulus, water sorption and solubility studies [22]. These studies guide future research into degradation resistance by demonstrating that many initial properties, such as degree of polymerization, are not predictive in terms of longer-term outcomes.

Dimethacrylate based (ester) monomers have vast clinical advantages in the ease, timing, degree of polymerization, and initial physical properties. Another approach to developing a new hydrolytic resistant resin is to address the location of the ester bond within a cured methacrylate polymer. The location of the ester bond may directly affect the durability and longevity of the resin material.

In this study, we synthesized a novel methacrylate (ethylene glycol ethyl methacrylate (EGEMA)) that has a switched or ‘flipped external’ ester group design compared to a traditional methacrylate (Ethylene glycol dimethacrylate (EGDMA)). EGEMA and EGDMA were added separately to a photo-activator system to create two different curable polymers. The flipped external ester group within the cured EGEMA polymer may hydrolyze in aqueous conditions like the ester group in EGDMA. However, the novel design of EGEMA potentially preserves the overall structure of the strength maintaining polymer backbone unlike EGDMA where the backbone network is broken upon hydrolysis. The aim of this study was to test EGEMA and EGDMA samples for changes in physical and mechanical properties after 15 weeks of accelerated aging.

2. Experimental section

2.1. Materials

Ethylene glycol dimethacrylate (EGDMA – 335681, Millipore Sigma USA) was used as a control monomer in this study. The photo/co-initiators Camphorquinone (CQ - 124893), Ethyl 4-(dimethyl amino) benzoate (EDMAB - E24905), and Diphenyliodonium hexafluorophosphate ((PH2I)+(PF6)− - 548014) were also purchased from Millipore Sigma USA and used without any modification. The monomer ethylene glycol ethyl methacrylate (EGEMA) was synthesized in a 1-pot 2-step reaction. Briefly, the reaction sequence began with commercially available 1,2-bis(2-iodoethoxy)ethane which is metallated with zinc followed by copper using a organometallic transformations similar to previously reported by Knochel and co-workers [16,17]. The Cu-Zn trans-metallated intermediate was reacted in situ with two equivalents of the electrophile ethyl 2-bromomethylacrylate to generate EGEMA in 54% yield. Ethyl-2-bromomethylacylate was synthesized in a two-step (66% yield) reaction [25], or purchased from Millipore Sigma USA. EGEMA is a liquid at room temperature with a viscosity of 10cP, and it remains a liquid at 0°C. The synthesis of EGEMA and spectroscopic characterization is further discussed in the Supplemental Information. To prevent spontaneous polymerization, monomethyl ether hydroquinone (MEHQ, Millipore Sigma) was added as an inhibitor, and the concentration of MEHQ was equilibrated to the concentration of 200ppm for both EGDMA and EGEMA.

2.2. Mold setup and disk preparation

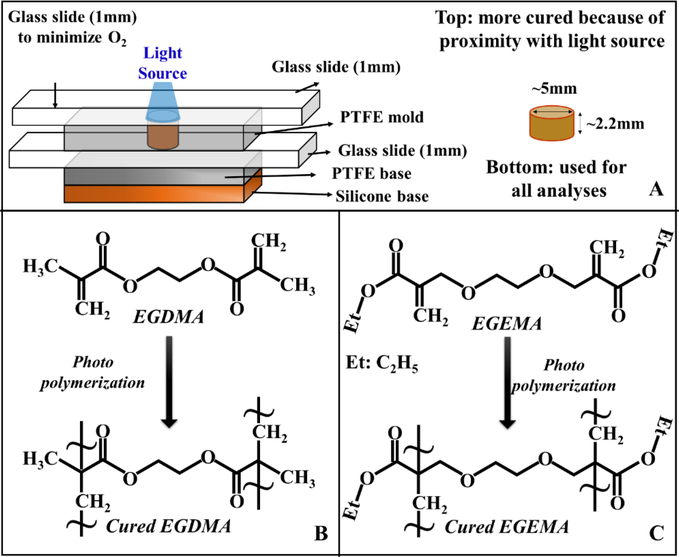

The EGDMA and EGEMA macromer disks were prepared by the addition of a photo-activator system (macromer mixture) composed of Camphorquinone (CQ), ethyl 4-dimethylamino benzoate (EDMAB) and diphenyliodonium hexafluorophosphate (PH2I)+(PF6)− in a polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) mold. 40μL of the macromer mixture (Figure 1A) in a solvent free composition were placed in PTFE mold with a glass slide as a base. A white PTFE sheet and silicone rubber were used to minimize the polymer mixture leakage. The hypothesized photo-polymerization reaction of EGDMA and EGEMA in the presence of camphorquinone (CQ) as photo-initiator and EDMAB & (PH2I)+(PF6)− as co-initiators are illustrated in Figure 1B–1C. For this study, all the disks were prepared at 1000mW/cm2 using a LED curing light (VALO S06816, Ultradent, UT) and cured for 40 seconds. We optimized the concentrations of the monomer and photo/co-initiator mixture source power and curing time using EGDMA monomer disks (to preserve EGEMA monomer material for use in the studies), and this information has been included as supplementary data (Table S1). The amounts of EGDMA, EGEMA, and photo/co-initiators used are shown in Table 1.

Figure 1:

the schematic of disk preparation set up (A), and photo polymerization reaction schematic for EGDMA (B) and EGEMA (C).

Table 1:

Composition of EGDMA and EGEMA mixtures with the amount of photo/co-initiators for preparing disks at 1000mW/cm2 and cured for 40seconds.

| Resin | Monomer (ml) | CQ (mg) | EDMAB (mg) | PH2I+ (mg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EGDMA | 1.0 | 5 | 13 | 13 |

| EGEMA | 1.0 | 5 | 13 | 13 |

2.3. Hydrolytic stability and Accelerated aging study

Polymer disks of EGDMA and EGEMA were tested for hydrolytic stability using an accelerated ageing model [26,27]. The sample disks were stored in sodium phosphate buffer (1.0ml) at pH of 7.4, which corresponds to resting pH of saliva and the sodium phosphate buffer was refreshed every week during weight assessment (every week) and hardness measurement (every 3rd week). An ASTM based method for accelerated aging of medical devices and polymers was carried out for 15 weeks (ASTM F1980–16). The sample disks (n=8) were exposed to sodium phosphate buffer solutions at 37°C (oral environment) and 55°C (accelerated aging, roughly 15 weeks ≈1 year @ 37°C). The 55°C temperature was employed for accelerated ageing, keeping 37°C as ambient temperature. The formulae to calculate the accelerated ageing factor (AAF) is given as equation 1 and accelerated ageing time (AAT) as equation 2.

| (1) |

| (2) |

Where T is experimental temperature and Ta is ambient temperature (37°C), which gave 3.48 as AAF at 55°C using equation 1. This indicates that the incubation time of 3.48 days for disks at 37°C would be equal to 1 day for disks at 55°C. In our study, we assumed Simulated Real Time Ageing (SRTA) as 365 days and using both SRTA and AAF in equation 2, the calculated accelerated ageing time (AAT) value was 104.82 days, which is equivalent to 15 weeks. Therefore, theoretically the degradation or damage to disks at 55°C in 15 weeks would be equivalent to 1 year at 37°C.

The longitudinal monitoring of weight (Mettler AE50, in grams up to 4 decimal places) every week and micro hardness of the disks were performed at week 3, 6, 9, 12 and 15. For weight and hardness measurements, the disks were blot dried (5–6 times) until no water was observed on the tissue surface. At the end of the study, the surface and subsurface analysis was performed by contact angle measurement using a captive air bubble technique, Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM), and Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT).

2.4. Material characterization

Fourier Transformation Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy

The degree of conversion (DC) of the monomers into a polymer disks was used as a measure of polymerization efficiency between EGDMA and EGEMA. The prepared polymer disks were stored at room temperature in airtight glass containers prior to mechanical, physical and chemical characterization for 24 hrs. For FTIR-ATR analysis, the bottom side of the prepared disks was placed in contact with the diamond crystal and force was applied to improve contact and signal. A Nicolet iS50 Fourier Transformation Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) system in Attenuated Total Reflectance (ATR) mode using diamond crystal was used in transmittance mode (2cm−1 resolution and 25 scans for each sample) over a 400–4000cm−1 range and the data were converted to absorbance (OMNIC, Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA). The absorbance data was used to calculate the degree of conversion or polymerization using equation 3 [28,29].

| (3) |

Water Contact Angle

Water contact angle measurements were used for examining the surface wettability of cured polymer disks. The analyses were performed by the sessile drop method using a contact angle meter (DM-CE1; Kyowa Interface Science, Japan) equipped with a digital camera and image analysis software (FAMAS, Kyowa Interface Science, Japan). Deionized water was used as the wetting liquid with a drop volume of 2.0 μL, and 4 disks for each sample type were analyzed. After hydrolytic stability study period of 15 weeks, the polymer disks were again analyzed for changes in wettability using the captive air bubble method for contact angle measurement [30]. The captive bubble setup was used to avoid the contact angle measurement error facilitated by developed cracks, grain boundaries, and damaged surface topography because of hydrolytic instability of disks in buffer. Disks were submerged upside down in a container with water. An air bubble was injected and the contact angle of the bubble with the surface of the immersed disk was measured (see Supplementary-Figure S1 for the set-up).

Vickers Hardness

For the physical characterization, micro hardness was measured using a Micro Surface Vickers Hardness Tester (Buehler Micromet II, Buehler Ltd., Lake Bluff, IL, USA) which is equipped with a diamond pyramid micro-indenter with a 136o angle between the opposing faces. A load of 100g was applied with an indentation holding time of 20sec. Vickers hardness (HV) was obtained using equation 4:

| (4) |

where F is the applied load in grams and d is the average length of the indentation measured in μm [31,32]. At least 3 disks for each sample type were analyzed with 2 indents on each disk. Hardness was measured for the ‘as prepared’ disks and the disks under hydrolytic challenge at week 3, 6, 9, 12 and 15.

Diametral tensile strength and total energy to fracture

The mechanical property - diametral tensile strength (DTS – Kg*f/cm2), which is a measure of material fracture point, was measured using a material testing system (858 Mini Bionix® II, MTS, Eden Prairie, MN, USA) at MDRCBB, School of Dentistry, University of Minnesota, by applying a load up to 5 kN on the ‘as prepared’ disks and disks dried after the conclusion of the hydrolytic stability study (n=6). The average disk diameter and thickness measured for EGDMA disks were 4.90mm±0.08 and 2.65mm±0.17, while for EGEMA the average diameter and thickness were 4.95mm±0.07 and 2.72mm±0.16, and statistically non-significant (p>0.99). The formulae used to calculate the diametral tensile stress at a given time for ‘as prepared’ disk and those same disks after 15 weeks of hydrolytic study have been included as equation 5.[33]

| (5) |

Where σx is the diametral tensile stress (MPa = ((Kg*f)/cm2)*(−0.09807)), P is applied load in Newton, D is diameter (mm) and T is thickness of disk (mm). For DTS vs stain graphs, the strain values were calculated using the equation ((Lt-L0)/L0), where L0 is the initial length and Lt is varying length with load and time.

To understand material toughness of these polymer discs before and after ageing, the total energy to fracture point was calculated using the diametral tensile stress vs strain data. The absolute area under the curve of diametral tensile stress vs strain was calculated (Origin 2019b software; Analysis – Mathematics - integrate) [34].

2.5. Water sorption, Optical Coherence tomography (OCT) and Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

The EGDMA and EGEMA ‘as prepared’ disks and the disks incubated for 15 weeks in buffer solution were rinsed with DI water and vacuum dried in a desiccator. Before and after vacuum drying, disk weight was obtained for both end point weight loss and relative water sorption for both the polymer materials.

To non-destructively examine the subsurface polymer integrity and identify the presence of refractive index mismatches caused by cracks filled with air (grain boundaries), a near-infrared 1315–1340nm Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) system (IVS-2000, Santec, Japan: bandwidth of source and numeric aperture of the focusing lens, min. Axial resolution: <18μm, min. Lateral resolution: 12.4μm, Depth of focus: 0.48mm, acquisition speed: 20,000 lines/second, Axial pixel size: >1000, Axial pixel resolution: <10μm) was used to image the disks (n=4). The intensity per pixel data in image text file was converted into a logarithmic false color scale (dB) using a custom script in Matlab R2019a. Based on the average background signal, the scattering intensities values above 20 dB were defined as possessing major grain boundary defects and values above 2 dB and below 20 dB were defined as a minor grain boundary defects. These values were arbitrarily defined, as a change in 2 dB is nearly a 50% increase in scattering and 20 dB is nearly an increase in 100-fold.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) imaging was used to study changes in the surface topography of the polymer disks. To characterize the surface topography, the polymer disks were broken into smaller pieces, followed by mounting on aluminum SEM stubs using carbon tape. The mounted specimens were then coated with a 15nm-thick Iridium layer to minimize polymer damage and then imaged by SEM (Hitachi SU8230, 40,000x magnification, voltage: 2kV, current: 5μA).

2.6. Statistical analysis

A Kruskal-Wallis test (Dunn’s multiple comparison) was conducted using GraphPad Prism version 8.0.2 software. The 95% confidence intervals have been used as error bars in all the graphs/data sets. In the case of relative weight loss at different temperatures, the mean relative weight loss every week was compared to relative weight at week 0. The asterisks representation is as follows: non-significant (ns) for p>0.05, * for p ≤ 0.05 (a), ** for p ≤ 0.01 (b), *** for p ≤ 0.001 (c) and **** for p ≤ 0.0001 (d). Kaplan-Meier (% survival curve) was drawn using the 10% relative weight loss as a measure for substantial failure.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Degree of conversion and Initial Characterization

The disk preparation set up schematics is shown in Figure 1A, while the Figures 1B and 1C illustrates the photo-polymerization reactions of acrylate group in both the EGDMA and EGEMA polymers. In the case of EGDMA, the ester group was inside the two polymerized chains joined by ester group (-COO-CH2-CH2-OOC-), while in the case of EGEMA, the ester group was outside and the polymerized chains were joined by the methylene glycol –CH2-O-CH2-CH2-O-CH2- group. We are defining the ester group in EGEMA as a ‘flipped external’ ester group.

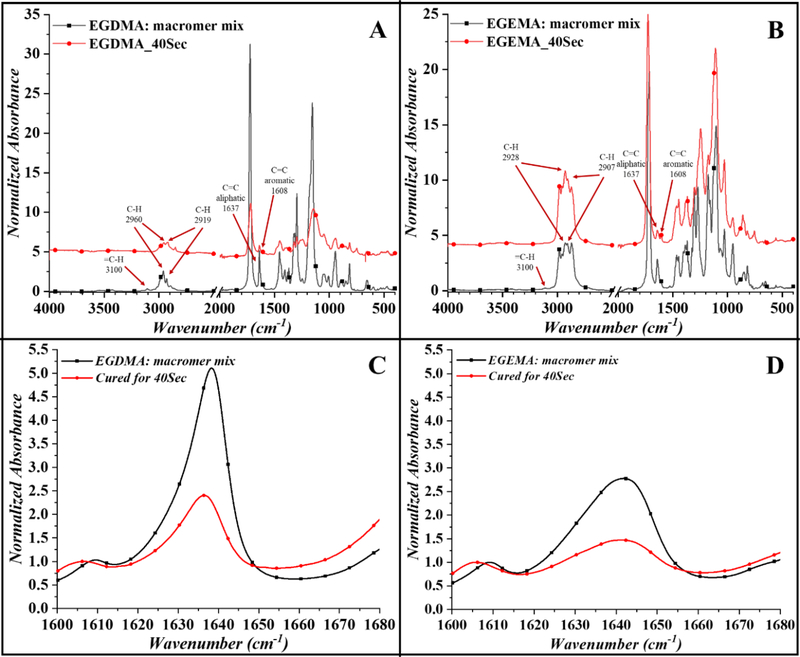

The prepared disks were first characterized by FTIR in ATR mode as we expected changes in FTIR-ATR spectrum during the photocuring of both the polymers EGDMA and EGEMA. The FTIR-ATR spectra of pure compounds along with the disk cured for 40 seconds is shown in Figure 2A – EGDMA, and 2B - EGEMA. The 3 regions of primary changes in the FTIR-ATR spectra included 2800–3000cm−1 for C-H sp3 and =C-H at 3100cm−1 (1st region). The 2nd region was for C=C acyl around 1637cm−1 and C=C aromatic (for photo-initiator/co-initiators) around 1608cm-1. The 3rd region was for C=O for ester and/or carboxylic acid at 1700 – 1750 cm-1. The 4th region from 1550cm−1 to 650cm−1 is for various C-O (ether, ester and carboxyl) and C-H (sp3 and sp2) stretching and bending modes.

Figure 2:

Complete FTIR scan for macromer mix and cured polymer disks for 40seond for EGDMA (A) and EGEMA (B), and the normalized peak at 1637cm−1 for stock and cured (40sec) for EGDMA (C) and EGEMA (D). Macromer mix: monomer with photo/co-initiators, cured/40sec: disks prepared by curing for 40seconds.

In the case of both EGDMA and EGEMA macromer mixtures, we observed a peak at 3100cm−1 for =C-H which showed reduced or negligible intensity after photocuring of acrylate C=C bonds. We expected major changes in 3rd region and used the FTIR-ATR information to calculate the degree of polymerization/conversion (DC) [28,29]. The acyl C=C group (in macromer mix) peak intensity at 1637cm−1 reduced on photo-polymerization (cured for 40 second) while the aromatic C=C peak intensity at 1608 cm−1 remained un-changed in both EGDMA and EGEMA polymer disks as shown in Figure 2A-EGDMA and 2B-EGEMA.

There was no change observed for C=O peak (1721 cm−1) in EGDMA spectra for macromer mixture and cured polymer disks. While for EGEMA, the C=O (ester) peak was observed at 1720 cm−1 (macromer mixture) which shifted to 1727 cm−1 on photocuring (disks). In the region 3000–2800 cm−1 (which is for aliphatic C-H sp3 bonds), we observed major changes for peaks at 2960 cm−1 and 2919 cm−1 for EGDMA, and 2928 and 2907cm−1 for EGEMA. In the case of EGDMA, the peak intensity for 2919 cm−1 increased after curing which may be associated with the increased C-H asymmetric stretching [35]. While in case of EGEMA, the C-H asymmetric peaks showed shift and enhanced intensity at 2928 cm−1, which may be a result of different groups surrounding the C-H sp3. All C-H stretching vibrations lies in the same region 2975–2840cm−1, which has been reported for both methyl (in EGDMA) and methylene (in EGDMA and EGEMA) stretching bands [36].

The normalized peaks at 1637cm−1 for the macromer mixture and disks prepared at 40 second curing time are shown in Figure 2C-EGDMA and 2D-EGEMA showing reduced intensity on curing, which signifies polymerization of methacrylate bonds in both the monomers. The calculated degree of conversion/polymerization (DC) values for EGDMA and EGEMA disks cured 40second at 1000mW/cm2 were 45.24%±8.8 and 44.60%±1.5 (figure 3A), while the surface contact angle for the respective disks were 65.45°±5.8 and 66.04°±6.4 (figure 3B). The data suggested comparable polymerization capability of both EGDMA and EGEMA monomers as well as surface wettability property.

Figure 3:

the quantified degree of conversion (A) and water contact angle (B) data for both EGDMA and EGEMA ‘as prepared’ disks (cured for 40sec). Relative weight loss data for EGDMA and EGEMA at 37°C (C) and 55°C (D) over the period of 15 weeks showing the mean (black line) and data distribution. AP – ‘as prepared’ disks, @T°C – disks incubated at T temperature in storage buffer. Not significant (ns) for p>0.05, * for p ≤ 0.05 (a), ** for p ≤ 0.01 (b), *** for p ≤ 0.001 (c) and **** for p ≤ 0.0001 (d). Week 1 - data collected at week 1 and so on. Error bars represent 95% confidence level.

The measured hardness, DTS vs strain curve, calculated DTS values and Total Energy to Fracture for ‘as prepared’ EGDMA and EGEMA disks has been included in Figure 4 and Figure 5 respectively. The ‘as prepared’ EGDMA disks (11.3HV and 10.35MPa) had higher hardness (p<0.0001) and DTS (p:ns) values compared to EGEMA disks (7.8HV and 8.44MPa) respectively, suggesting better initial performance and higher load bearing capability (Fig. 4A–4B and 5B). Total Energy to Fracture was significantly higher (P<0.05) for EGEMA (2.2MJ/m3) as prepared disks compared to EGDMA disks (1.4MJ/m3), which is a measure of material toughness (Figure 5C).

Figure 4:

measured hardness data for EGDMA (A) and EGEMA (B) disks at different temperatures in 15 weeks study. AP – ‘as prepared’ disks, @T°C – disks incubated at T temperature in storage buffer. Not significant (ns) for p>0.05, * for p ≤ 0.05 (a), ** for p ≤ 0.01 (b), *** for p ≤ 0.001 (c) and **** for p ≤ 0.0001 (d). W3-data collected at week 3 and so on. Diametral Tensile strength data collected at the end of study (week 15). Error bars represent 95% confidence level.

Figure 5:

The diametral tensile stress vs stain graphs for both polymer disks (A) and calculated DT Strength values for respective sample types (B) incubated at 37°C and 55°C, the calculated Total energy to Fracture (C) using DTS vs strain graphs, which is a measure of material toughness for the same sample types. AP – ‘as prepared’ disks, @T°C – disks incubated at T temperature in storage buffer. Not significant (ns) for p>0.05, * for p ≤ 0.05 (a), ** for p ≤ 0.01 (b), *** for p ≤ 0.001 (c) and **** for p ≤ 0.0001 (d). Error bars represent 95% confidence level.

3.2. Hydrolytic stability and accelerated aging

The ‘as prepared’ disks (n=16) were suspended in 1.0ml sodium phosphate buffer (in 5.0ml glass bottles with air-tight PTFE lids) and incubated at 37°C and 55°C in a digitally controlled temperature oven. The relative weight changes of the EGDMA (n=8) and EGEMA (n=8) disks are shown in Figure 3C and 3D respectively, showing the relative weight loss distribution of individual disks over the period of 15 weeks as a violin graph. The accelerated aging model (temperature of 55°C) resulted in higher material weight loss. In terms of relative weight loss (%) at 37°C and 55°C, EGDMA disks lost more relative weight 9.0% and 12.5% compared to EGEMA disks which lost only 5.23% and 6.4% at respective temperatures. The relative weight loss for EGDMA disks was significant from week 7 at 37°C while week 6 at 55°C as a result of accelerated ageing temperature. On the other hand, for EGEMA, the changes were significant at week 15 and week 9 onwards at 37°C and 55°C, as represented in figure 3C and 3D. The choice of storage media may have affected the results of this work. While the Academy of Dental Materials has proposed the reproducible storage media of water to test hydrolysis effects, our study choose a phosphate buffer in water [37] as the primary storage media since it is reproducible, stable at a pH range of 5.1 to 8.0 to test the influence of pH, and compatible for the temperature aging model of 55 °C. Also, esterase enzymes can be suspended in phosphate buffers which can be used in future studies examining the direct effects of esterase enzymes on EGDMA and EGEMA degradation. It should be pointed out that there are additional options of storage media such as a more complex artificial saliva [38] that may produce different results and may have additional advantages on accelerated ageing model/experiments.

3.3. Change in hardness, and Diametral Tensile Strength (DTS)

As the disks aged in 37°C and 55°C buffer solution, hardness characterization was performed every 3rd week (Figure 4A-EGDMA and 4B-EGEMA), and at the end of longitudinal study diametral tensile strength (DTS) was measured which is included as Figure 5A (Diametral Tensile Stress vs strain) and 5B (DTS bar graph with statistical analysis). We carefully term ‘hardness’ as “selective intact surface hardness” because following week 9 the EGDMA disks started curling, leading to the formation of irregular surface island or patterns resulting in difficulty to find a flat surface for indenting. These irregular surfaces could not be accurately measured by the hardness test (the sample measurements can only be conducted with intact surfaces). The selective intact surface hardness data suggested a slight increase in hardness at both temperatures for EGDMA (Figure 4A), though only the observed hardness at week 12 onwards at temp 55°C was statistically significant. The increase in the hardness value could be the result of sample bias due to only sampling intact surfaces and discounting rough and degraded surfaces.

Another explanation is that hardness values may be associated with the increase in brittleness of EGDMA polymer disks as result of dark/post curing process in buffer, which was supported by significant decrease in DTS values with increasing temperature (2.94MPa for 37°C, p=0.0337 and 1.11MPa for 55°C, p=0.0003) compared to ‘as prepared’ disks (11.68MPa), as reported in Figure 5B as a result of destabilized EGDMA polymer structure. The loss of DTS for EGDMA was temperature dependent suggested by 75.81% and 88.19% loss in strength at 37°C and 55°C respectively. The incubation of commercially available cements like Breeze-composite, Adhesor Carbofine - Zinc polycarboxylate and IHDENT-Giz type II in different solvents (ethanol, tea and soda) is known to alter the Vickers hardness and diametral tensile strength of cements disks over the period of 30 days [39].

Contrary to EGDMA, the EGEMA monomer disks showed a significant increase in hardness up to week 9 followed by reduction in average hardness values until week 15 (Figure 4B). This supports the hypothesis that, initially the rate of dark curing in buffer dominated over the hydrolysis of ester group in EGEMA which is supported by an increase in hardness up to week 9, followed by ester group hydrolysis dominance at both temperatures leading to softening of polymer disks. Unlike EGDMA, EGEMA polymer disks lost only 44% diametral tensile strength.

3.4. Total Energy to Fracture (Toughness)

The total energy to fracture (Fig. 5C) for EGEMA (2.2MJ/m3) pristine disks was significantly higher (p<0.05) compared to EGDMA (1.4MJ/m3) pristine disks. For EGDMA disks, the total energy to fracture that can be a measure of material toughness decreased significantly with an increase in incubation temperature (37°C: 0.23MJ/m3, p=0.02 and 55°C: 0.16MJ/m3, p=0.0012). While for EGEMA disks, the significant reduction in total energy to fracture was at 37°C (0.43MJ/m3, p=0.0011), with slight increase at 55°C (0.84MJ/m3). The analysis suggested that even though hardness and DTS suggested that the pristine EGEMA disk were not mechanically stronger than EGDMA, the toughness calculation reported otherwise. In addition, the incubation temperature had the similar effect on EGDMA disks in all the tested mechanical properties. The temperature 55°C for EGEMA tend to improve the mechanical property compared to 37°C in sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) but the improvement was not significant and need further investigation. Supporting our analysis, there have been reports suggesting to improve the properties like degree of conversion, fracture toughness, and elastic modulus of Bis-GMA:TEGDMA composite on 24h thermal treatment [40].

3.5. Wettability, End point weight loss and water sorption

Compared to EGDMA disks (average contact angle 52°), EGEMA polymer disks showed statistically significant increase in wettability suggested by an average contact angle 34° for disks incubating in buffer at both temperatures, shown in Figure 6A. This higher wettability in the case of EGEMA disks could be associated to the presence of more accessible carboxyl groups on the surface, which lie outside the polymer chain in molecular arrangement. These results suggest that as ester groups hydrolyze during ageing, carboxylic acid groups replaced the ester groups in both the EGDMA and EGEMA monomers disks. The presence of carboxylic acid (-COONa/H) groups in the polymer disk structure increased the wettability of disks suggested by reduced water contact angle values measured by captive bubble set up.

Figure 6:

Water contact angle (A), terminal weight loss data of ‘as prepared’ disks compared to disks incubated at different temperature up to week 15 (B) and relative water sorption for EGDMA and EGEMA disks incubated at 37°C and 55°C (C). AP – ‘as prepared’ disks, @T°C – disks incubated at T temperature in storage buffer. Not significant (ns) for p>0.05, * for p ≤ 0.05 (a), ** for p ≤ 0.01 (b), *** for p ≤ 0.001 (c) and **** for p ≤ 0.0001 (d). W3-data collected at week 3 and so on. All these data sets collected at the end of study (week 15). Error bars represent 95% confidence level.

The end point weight loss by the EGDMA polymer disks was significant at week 15, as suggested by higher weight loss at 55°C (22.45%, p=0.0072) compared to 37°C (12.12%, ns) as shown in Figure 6B. This loss in material could be associated with the leaching of un-reacted components in the mixture or the expected loss of ethylene glycol from the polymer backbone as a by-product. In our study of EGEMA polymer disks, which restricted the loss of backbone as a result of re-arrangement of ester bond (moved outside) and backbone connecting the methacrylate polymer chain with ether bond, which is not susceptible to hydrolysis, showed a non-significant decrease in weight loss as shown in Figure 6B. Interestingly, the weight change (not relative weight loss) for both EGDMA and EGEMA polymer disk in storage buffer at 37°C and 55°C was not significant, which may be associated with the adsorption of water molecules replacing lost material.

The loss of material on degradation, erosion or leeching of un-reacted components in polymer disks resulted in sorption of water molecules into the voids. Higher weight loss could be associated with the surface wettability of polymer disks, which can affect accessibility of water molecules as well as hydrolysis rate. In related studies, disks prepared using a hydrophilic polymer like TEGDMA adsorbed 6.3wt% water, while disks of a resin Bis-EMA only adsorbed 1.79 wt% water as reported by I. Sideridou et al.[41] Similarly, in this study, EGDMA disks showed rapid weight loss and adsorbed more water compared to EGEMA disks (Figure 6C). The water sorption for EGDMA disks was significantly temperature dependent as suggested by the average water sorption % values, 5.15% and 14.78% (p=0.0436) for 37°C and 55°C respectively, while for EGEMA disk, the average water sorption values were 4.11% and 4.01% (p:ns). In other studies, a similar solvent absorption by Bis-GMA and UDMA resins has been reported suggesting 13.3wt% and 12.0wt% ethanol absorption, respectively, while TEGDMA, D3MA and Bis-EMA resins sorbed 10.1wt%, 7.34wt% and 6.61wt% of ethanol/water mixture over 30 days’ time period, respectively, which was associated with the release of unreacted macromer [42].

3.6. SEM and Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) imaging

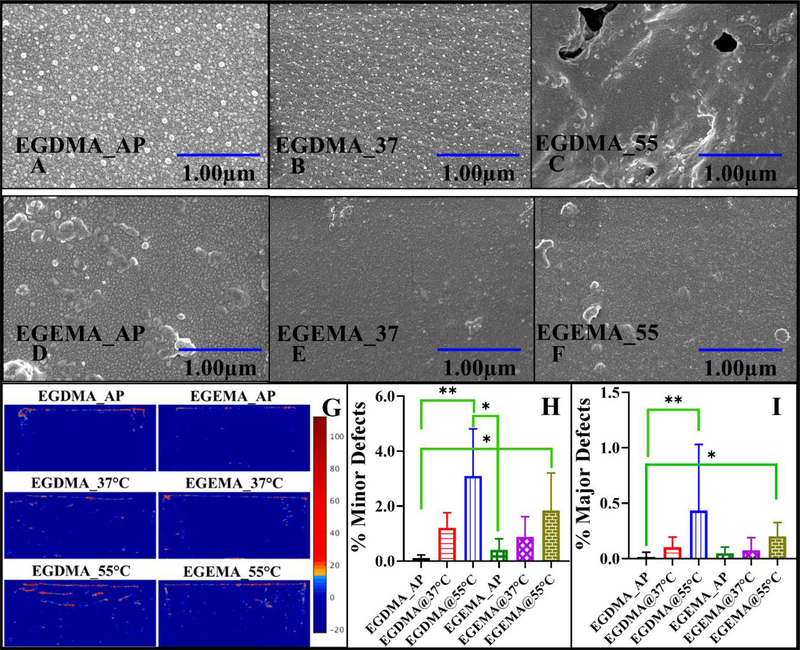

The surface defects on hydrolytic degradation were imaged using SEM. The EGDMA polymer disks which had ester groups connecting the polymerized chains showed visually evident erosion of material and structural damage with increasing temperature (Supplemental- Figure S9-1st row). However, the defects at submicron level were also prominent as shown in Figure 7A–7C, confirming polymer degradation and erosion with increasing temperature. While for EGEMA disks there was no visible structural damage as shown in Figure S9 (2nd row) (bright field image), but at a submicron level we observed some defects in the form of cracks or pores as shown in figure 7D–7F with increasing temperature.

Figure 7:

SEM images of disks “as prepared, at 37°C and 55°C” showing surface changes for EGDMA (A-C) and EGEMA (D-F), Optical Coherence Tomography Images of ‘as prepared’ and disks incubated at different temperatures (G) and semi-quantitative data in bar graph for minor (H) and major (I) grain boundary defects. AP – ‘as prepared’ disks, @T°C – disks incubated at T temperature in storage buffer. Not significant (ns) for p>0.05, * for p ≤ 0.05 (a), ** for p ≤ 0.01 (b), *** for p ≤ 0.001 (c) and **** for p ≤ 0.0001 (d). All these data sets or analysis performed at the end of study (week 15). Error bars represent 95% confidence level.

The subsurface analysis by OCT imaging was in agreement with the SEM results. The disks, which undergo hydrolytic degradation, absorbed water or buffer molecules in the developed cavities, and when vacuum dried, left optical grain boundaries filled with air. The EGDMA and EGEMA disks’ OCT scan for ‘as prepared’ disks showing limited backscattering indicative of a fairly uniform polymer matrix and disks incubated in buffer at 37°C & 55°C showing developed grain boundaries defects are shown in Figure 7G-left column and 7G-right column respectively.

The semi-quantitative analysis using Matlab script for minor and major grain boundary defects % for ‘as prepared’ disks of both the polymers were not statistically significantly. OCT images showed that EGDMA disks incubated at 55°C for 15 weeks develop high scattering grain boundaries as indicated by the false color scale of backscattered intensity. The analysis suggested the temperature dependency of developed grain boundaries as the changes were significant at 55°C compared to ‘as prepared’ disks only in the case of EGDMA polymer (Figure 7H-minor grain boundaries and 7I-major grain boundaries defects). The OCT image analysis concluded that even though there was an increase in minor and major grain boundary defects for EGEMA disks incubated at 37°C and 55°C, these changes were less substantial.

3.7. Hydrolytic degradation reaction and changes in FTIR-ATR spectrum

The reaction schematic for ester group hydrolysis in both the polymers EGDMA and EGEMA in the presence of sodium phosphate buffer pH 7.4 has been included in Figure 8A and 8B, respectively, along with the expected by-products. Further studies will confirm the central hypothesis that, in the case of EGDMA, ethylene glycol is released as a by-product, weakening the backbone of polymer disks, while in the case of EGEMA, ethanol is released from the polymer chain without substantially affecting the polymer chain or disk structure integrity. These future studies may include analysis of collected solutions by Liquid Chromatography (LC) and Gas Chromatography (GC) - Mass Spectroscopy (MS), however, this present study provides compelling evidence that EGEMA is more resistant to changes in the chemical, mechanical, and physical properties during ageing. Polymer backbone preservation is a possible reason for this observation.

Figure 8:

Suggested degradation reaction schematics showing the inter-chain covalent cross-linking is lost with ethylene glycol as a by-product for EGDMA (A) and inter-chain covalent cross-lining is retained by intact backbone chain in EGEMA (B) preserving long term mechanical properties and ethanol as a by-product, FTIR graphs for EGDMA (C) and EGEMA (D) disks cured for 40second and incubated at different temperatures for hydrolytic degradation study. AP – ‘as prepared’ disks, @T°C – disks incubated at T temperature in storage buffer. Not significant (ns) for p>0.05, * for p ≤ 0.05 (a), ** for p ≤ 0.01 (b), *** for p ≤ 0.001 (c) and **** for p ≤ 0.0001 (d).

When examining the weight loss of EGDMA and EGEMA over 15 weeks, 3 disks showed the reduced relative weight more than 10% at 37°C in case of EGDMA while the number increased to 5 at temperature 55°C. On the other hand, because of the resistive hydrolytic behavior and stability of polymer backbone only one EGEMA disk at 55°C temperature showed relative weight loss more than 10%. Kaplan Meier survival curve analysis indicate that EGEMA disks have 100% and 88.89% survival rates at temperature 37°C and 55°C respectively, while the survival percentage decreased to 66.67% and 44.44% for EGDMA respectively and the data was statistically significant as per Log-rank test (p=0.04) (SI Figure S11A).

Because of the ester group hydrolysis in both the polymers, which resulted in release of ethylene glycol and ethanol as by-products from EGDMA and EGEMA, respectively, and formation of carboxylic acid group in both the polymers, we anticipated some changes in FTIR-ATR spectra. Because of the change in design structure of EGEMA or release of small molecule ethanol on hydrolysis, we did not observe any major changes in FTIR-ATR spectra of EGEMA, apart from slight shift in C=O peak from 1727 to 1725cm−1 (3 disks were scanned in ATR mode) and minor shifts and shape changes of FTIR-ATR peaks in the region 1000–650cm−1 which a region for sp2 C-H and C-O bending and stretching modes. Contrary to EGEMA disks, the FTIR-ATR spectra for EGDMA disks (Figure 8C) suggested the loss of 2919cm−1 peak and a single peak at 2960cm−1, which is the region characteristic for C-H stretching. Thus, the loss of intensity for 2919cm−1 may be associated with the release of ethylene glycol molecules (HO-CH2-CH2-OH), which resulted in a reduced number of C-H bond stretching vibrations for both temperatures. The peak at 2960cm−1 was also more prominent in the EGDMA macromer solution as shown in Figure 2A. The new peaks in the region 1440–1400cm−1 and 1320–1210cm−1 could be associated with the C-O for carboxyl group in both of the polymers.

The FTIR-ATR analyses of EGEMA (Figure 8D) ‘as prepared’ and disks under hydrolytic stability investigation showed no changes, confirming the minor or negligible change in the chemical structure. On the other hand, EGDMA disks showed major changes in the region 2975–2840cm−1 that is associated with C-H stretching vibrations with the release of ethylene glycol as an expected by-product. [36]. This further supports the overall ‘polymer backbone preservation’ hypothesis and hydrolytic stability of EGEMA over EGDMA.

4. Conclusion

EGDMA polymers showed markedly greater loss of mechanical and physical properties; and surface degradation effects than EGEMA. While EGEMA did experience some degree of degradation effects, these were substantially less than EGDMA. This identifies EGEMA as a potential degradation resistant hydrophilic monomer that could be incorporated into a dental sealant or composite material system to improve wettability and durability. Future work will examine how blending EGEMA with other flipped ester group design polymers, especially those that contain functional groups providing the rigidity and hydrophobicity, may continue to improve physical, mechanical, and chemical properties and longevity of the polymer matrix.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under award number 2R44DE024013 to TDA Research. Parts of this work were carried out in the Characterization Facility, University of Minnesota, a member of the NSF - Funded Materials Research Facilities Network (www.mrfn.org) via the MRSEC program. The Hitachi SU8320 CryoSEM and Cryo-specimen preparation system were provided by NSF MRI DMR-1229263 program. Authors would like to thank Young Heo and Dr. Hooi Pin Chew for allowing access and setting up the MTS system and OCT IVS 2000 system. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or NSF.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: All co-authors may potentially be named on a TDA Research/University of Minnesota provisional patent.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This document is the Accepted Manuscript version of a Published Work that appeared in final form in ACS Biomaterials Science & Engineering, copyright © American Chemical Society after peer review and technical editing by the publisher. To access the final edited and published work see https://pubs.acs.org/articlesonrequest/AOR-NXR4IHUX4GZWYGMB8GWI.

5. References

- [1].Brauer G M 1966. Dental applications of polymers: a review J. Am. Dent. Assoc 72 1151–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Vervliet P, de Nys S, Boonen I, Duca R C, Elskens M, van Landuyt K L and Covaci A 2018. Qualitative analysis of dental material ingredients, composite resins and sealants using liquid chromatography coupled to quadrupole time of flight mass spectrometry J. Chromatogr. A 1576 90–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Bland M H and Peppas N A 1996. Photopolymerized multifunctional (meth)acrylates as model polymers for dental applications Biomaterials 17 1109–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Bayarı S H, Krafft C, İde S, Popp J, Guven G, Cehreli Z C and Soylu E H 2012. Investigation of adhesive-dentin interfaces using Raman microspectroscopy and small angle X-ray scattering J. Raman Spectrosc 43 6–15 [Google Scholar]

- [5].Delaviz Y, Finer Y and Santerre J P 2014. Biodegradation of resin composites and adhesives by oral bacteria and saliva: A rationale for new material designs that consider the clinical environment and treatment challenges Dent. Mater 30 16–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Finer Y and Santerre J P 2003. Biodegradation of a dental composite by esterases: dependence on enzyme concentration and specificity J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed 14 837–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Khalichi P, Singh J, Cvitkovitch D G and Santerre J P 2009. The influence of triethylene glycol derived from dental composite resins on the regulation of Streptococcus mutans gene expression Biomaterials 30 452–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].NÓBREGA MTC, DANTAS E L de A, ALONSO RCB, ALMEIDA L de F D de, PUPPIN-RONTANI RM and SOUSA FBDE 2020. Hydrolytic degradation of different infiltrant compositions within different histological zones of enamel caries like-lesions Dent. Mater. J 39 449–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Organization W H 2011. Joint FAO/WHO expert meeting to review toxicological and health aspects of bisphenol A: final report, including report of stakeholder meeting on bisphenol A, 1–5 November 2010, Ottawa, Canada Joint FAO/WHO expert meeting to review toxicological and health aspects of bisphenol A: final report, including report of stakeholder meeting on bisphenol A, 1–5 November 2010, Ottawa, Canada [Google Scholar]

- [10].Sekizawa J 2008. Low-dose effects of bisphenol A: a serious threat to human health? J. Toxicol. Sci 33 389–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Øysæd H, Ruyter I E and Sjøvik Kleven I J 1988. Release of Formaldehyde from Dental Composites J. Dent. Res 67 1289–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Nedeljkovic I, De Munck J, Ungureanu A-A, Slomka V, Bartic C, Vananroye A, Clasen C, Teughels W, Van Meerbeek B and Van Landuyt K L 2017. Biofilm-induced changes to the composite surface J. Dent 63 36–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Khalichi P 2004. Effect of composite resin biodegradation products on oral streptococcal growth Biomaterials 25 5467–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Sadeghinejad L, Cvitkovitch D G, Siqueira W L, Santerre J P and Finer Y 2016. Triethylene Glycol Up-Regulates Virulence-Associated Genes and Proteins in Streptococcus mutans ed Z T Wen PLoS One 11 e0165760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Huang B, Cvitkovitch D G, Santerre J P and Finer Y 2018. Biodegradation of resin–dentin interfaces is dependent on the restorative material, mode of adhesion, esterase or MMP inhibition Dent. Mater 34 1253–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Moraschini V, Fai C K, Alto R M and dos Santos G O 2015. Amalgam and resin composite longevity of posterior restorations: A systematic review and meta-analysis J. Dent 43 1043–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Gonzalez-Bonet A, Kaufman G, Yang Y, Wong C, Jackson A, Huyang G, Bowen R and Sun J 2015. Preparation of Dental Resins Resistant to Enzymatic and Hydrolytic Degradation in Oral Environments Biomacromolecules 16 3381–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Yang Y, Urbas A, Gonzalez-Bonet A, Sheridan R J, Seppala J E, Beers K L and Sun J 2016. A composition-controlled cross-linking resin network through rapid visible-light photo-copolymerization Polym. Chem 7 5023–30 [Google Scholar]

- [19].Wang X, Huyang G, Palagummi S V, Liu X, Skrtic D, Beauchamp C, Bowen R and Sun J 2018. High performance dental resin composites with hydrolytically stable monomers Dent. Mater 34 228–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Dickens S H, Stansbury J W, Choi K M and Floyd C J E 2003. Photopolymerization Kinetics of Methacrylate Dental Resins Macromolecules 36 6043–53 [Google Scholar]

- [21].Sinha J, Dobson A, Bankhar O, Podgórski M, Shah P K, Zajdowicz S L W, Alotaibi A, Stansbury J W and Bowman C N 2020 Vinyl sulfonamide based thermosetting composites via thiol-Michael polymerization Dent. Mater 36 249–56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Fugolin A P, Lewis S, Logan M G, Ferracane J L and Pfeifer C S 2020 Methacrylamide–methacrylate hybrid monomers for dental applications Dent. Mater 36 1028–37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Majid T N and Knochel P 1990. A new preparation of highly functionaized aromatic and heteroaromatic zinc and copper organometallics Tetrahedron Lett 31 4413–6 [Google Scholar]

- [24].AchyuthaRao S, Tucker C E and Knochel P 1990. Preparation of functionalized zinc and copper organometallics containing sulfur functionalities at the alpha or gamma position Tetrahedron Lett 31 7575–8 [Google Scholar]

- [25].Villieras J and Rambaud M 2002. Wittig-Horner Reaction in Heterogeneous Media; 1. An Easy Synthesis of Ethyl α-Hydroxymethylacrylate and Ethyl α-Halomethylacrylates using Formaldehyde in Water Synthesis (Stuttg) 1982 924–6 [Google Scholar]

- [26].Devices S M. Standard Guide for Accelerated Aging of Sterile Barrier Systems for Medical. ASTM Int.; West Conshohoken, PA, USA: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- [27].ASTM F1980 A. Standard Guide for Accelerated Aging of Sterile Barrier Systems for Medical Devices. ASTM Int.; West Conshohoken, PA, USA: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [28].S L, Y Q, G X, S V, M A, L JS, B CL and Spencer P. AO - Song LO http://orcid.org/000.−0003-1691-9583 2016. Development of methacrylate/silorane hybrid monomer system: Relationship between photopolymerization behavior and dynamic mechanical properties J. Biomed. Mater. Res. - Part B Appl. Biomater 104 841–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Abedin F, Ye Q, Camarda K and Spencer P 2016. Impact of light intensity on the polymerization kinetics and network structure of model hydrophobic and hydrophilic methacrylate based dental adhesive resin J. Biomed. Mater. Res. - Part B Appl. Biomater 104 1666–78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Shojaei A H and Li X 1997. Mechanisms of buccal mucoadhesion of novel copolymers of acrylic acid and polyethylene glycol monomethylether monomethacrylate J. Control. Release [Google Scholar]

- [31].Maier A and Uhl A 2011. Robust Automatic Indentation Localisation and Size Approximation for Vickers Microindentation Hardness Indentations 7th Int. Symp. Image Signal Process. Anal. (ISPA 2011) 295–300 [Google Scholar]

- [32].Ghrib T, Bouhafs M and Yacoubi N 2010. Correlation between Thermal and Mechanical Properties of the 10NiCr11 Advances in the State of the Art of Fire Testing (100 Barr Harbor Drive, PO Box C700, West Conshohocken, PA 19428–2959: ASTM International; ) pp 489–489–11 [Google Scholar]

- [33].Bresciani E, Barata T de J E, Fagundes TC, Adachi A, Terrin MM and Navarro M F de L 2004. Compressive and diametral tensile strength of glass ionomer cements J. Appl. Oral Sci 12 344–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Boazak E M, Greene V K and Auguste D T 2019. The effect of heterobifunctional crosslinkers on HEMA hydrogel modulus and toughness ed Lavik E PLoS One 14 e0215895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Francombe M (Georgia S U 1991. Thin Films for Advanced Electronic Devices (Elsevier Academic Press; ) [Google Scholar]

- [36].Larkin P J. Infrared and Raman Spectroscopy: Principles and Spectral Interpretation 2017 [Google Scholar]

- [37].Armstrong S, Breschi L, Özcan M, Pfefferkorn F, Ferrari M and Van Meerbeek B 2017. Academy of Dental Materials guidance on in vitro testing of dental composite bonding effectiveness to dentin/enamel using micro-tensile bond strength (μTBS) approach Dent. Mater 33 133–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].J Pytko-Polonczyk J, Jakubik A, Przeklasa-Bierowiec A and Muszynska B 2017. Artificial saliva and its use in biological experiments. J. Physiol. Pharmacol 68 807–13 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Szczesio-Wlodarczyk A, Rams K, Kopacz K, Sokolowski J and Bociong K 2019. The Influence of Aging in Solvents on Dental Cements Hardness and Diametral Tensile Strength Materials (Basel) 12 2464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Esteves R A, Boaro L C C, Gonçalves F, Campos L M P, Silva C M and Rodrigues-Filho L E 2018. Chemical and Mechanical Properties of Experimental Dental Composites as a Function of Formulation and Postcuring Thermal Treatment Biomed Res. Int 2018 1–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Sideridou I 2003. Study of water sorption, solubility and modulus of elasticity of light-cured dimethacrylate-based dental resins Biomaterials 24 655–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Sideridou I D and Karabela M M 2011. Sorption of water, ethanol or ethanol/water solutions by light-cured dental dimethacrylate resins Dent. Mater 27 1003–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.