Abstract

Background

Mobile clinics have been used to deliver primary health care to populations that otherwise experience difficulty in accessing services. Indigenous populations in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States experience greater health inequities than non-Indigenous populations. There is increasing support for Indigenous-governed and culturally accessible primary health care services which meet the needs of Indigenous populations. There is some support for primary health care mobile clinics implemented specifically for Indigenous populations to improve health service accessibility. The purpose of this review is to scope the literature for evidence of mobile primary health care clinics implemented specifically for Indigenous populations in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States.

Methods

This review was undertaken using the Joanna Brigg Institute (JBI) scoping review methodology. Review objectives, inclusion criteria and methods were specified in advance and documented in a published protocol. The search included five academic databases and an extensive search of the grey literature.

Results

The search resulted in 1350 unique citations, with 91 of these citations retrieved from the grey literature and targeted organisational websites. Title, abstract and full-text screening was conducted independently by two reviewers, with 123 citations undergoing full text review. Of these, 39 citations discussing 25 mobile clinics, met the inclusion criteria. An additional 14 citations were snowballed from a review of the reference lists of included citations. Of these 25 mobile clinics, the majority were implemented in Australia (n = 14), followed by United States (n = 6) and Canada (n = 5). No primary health mobile clinics specifically for Indigenous people in New Zealand were retrieved. There was a pattern of declining locations serviced by mobile clinics with an increasing population. Furthermore, only 13 mobile clinics had some form of evaluation.

Conclusions

This review identifies geographical gaps in the implementation of primary health care mobile clinics for Indigenous populations in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States. There is a paucity of evaluations supporting the use of mobile clinics for Indigenous populations and a need for organisations implementing mobile clinics specifically for Indigenous populations to share their experiences. Engaging with the perspectives of Indigenous people accessing mobile clinic services is imperative to future evaluations.

Registration

The protocol for this review has been peer-reviewed and published in JBI Evidence Synthesis (doi: 10.11124/JBISRIR-D-19-00057).

Supplementary Information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at10.1186/s12939-020-01306-0.

Keywords: Global health, Health services, Indigenous health, Mobile health clinics, Primary health care

Background

Accessible primary health care is an inherent human right for all populations, as stipulated by the Declaration of Alma-Ata (1978) [1]. Primary health care encompasses early interventions delivered by general practitioners, nurses and allied health professionals such as health promotion, screening for disease and health education for disease prevention [1, 2]. Evidence supports the effectiveness of primary health care services in improving the management of chronic disease and addressing risk factors for developing chronic disease, across a range of contexts [3–6]. However, primary health care services are not always accessible for all populations. This is the case for Indigenous populations in Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United States, who often experience racism, cultural, transport and financial barriers when accessing health services [7–10].

The multi-dimensional nature of health care access is well documented which includes the availability, accessibility, accommodation, affordability, acceptability and awareness of health care services [11, 12]. For Indigenous people, an important component of health care access is the provision of culturally safe and holistic health care by a trusted health professional who respects their values, traditions and customs [13–15]. Across the globe, Indigenous populations are culturally and linguistically diverse, with differing environmental contexts (e.g. climates, connections to land and waterways), cultural practices (e.g. lore, customs, spiritual beliefs) and cultural identities (e.g. kinship ties, ancestors) [16]. In modern states with a history of invading Indigenous lands through the process of colonization (e.g. Australia, Canada, New Zealand and United States), there are numerous Indigenous nations, tribes and clans, all with unique cultural identities, histories and languages [16]. However, there are similarities in the experience of colonialization for Indigenous people (e.g. racism, violence, experience of European communicable diseases and loss of land), particularly in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States, which has led to enduring inequity [7, 17, 18].

To redress health inequities for Indigenous populations, including the burden of chronic disease and high mortality rate compared to non-Indigenous populations [18], culturally safe models of health care are needed which improve the accessibility of primary health care services [19]. Evidence supports that a greater participation of Indigenous people in their health care leads to better health outcomes [20, 21]. Therefore, Indigenous-governed health care services are inherent to the provision of culturally accessible health care [22]. In Australia, over 140 Aboriginal Community-Controlled Health Services (ACCHOs) provide primary health care services to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people [23]. Internationally, evidence supports the important contribution of Indigenous-governed health organisations in providing culturally safe and accessible primary health care for Indigenous populations [24–27].

Mobile clinics implemented specifically for Indigenous populations and governed by Indigenous health organisations, may be one way to improve the accessibility of culturally safe primary health care for Indigenous populations. It is known that mobile clinics are able to deliver health care to populations experiencing health inequity, particularly in countries where health care can be otherwise inaccessible due to transport, financial or cultural barriers [28–30]. In the United States, there has been an upward surge in the implementation of mobile clinics, particularly of mobile clinics delivering primary health care services [31, 32]. The support for mobile clinics in providing flexible and safe health care to vulnerable people has gained traction with the recent COVID-19 pandemic [33]. In other countries, mobile clinics have also been implemented with the purpose of screening for communicable and non-communicable diseases [34–36] and providing disaster relief [37, 38]. Some research supports the potential for mobile clinics to be a cost-effective model of health care and improve the management of chronic disease [29, 39].

There is also some evidence of mobile clinics being implemented specifically for Indigenous populations, either by an Indigenous health organization [40] or for a specific disease (e.g. diabetes) [41] or treatment (e.g. dialysis) [42]. What is not known, is the available evidence regarding the use of primary health care mobile clinics implemented specifically for Indigenous populations in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States who share a similar history of colonization, discrimination and barriers to accessing primary health care services [7]. This was apparent when undertaking a preliminary search of the literature for evidence around the effectiveness of mobile clinics for Indigenous populations, as part of seeking funding for a mobile clinic to be implemented in an Australian ACCHO. Indeed, it was an absence of evidence that made it difficult to obtain funding for the mobile clinic, justifying the need for a systematic scoping review. It is known that there is a vast body of literature regarding mobile clinics in the United States, yet there is very little focus on Native American, Native Hawaiian, and Alaskan Native populations [32]. A systematic scoping review was conceptualised to synthesise the available evidence regarding the use of primary health care mobile clinics implemented specifically for Indigenous populations in order to identify gaps in the literature and inform future research evaluating mobile clinics for Indigenous populations. Specifically, the review question developed was:

What is the evidence surrounding the use of mobile primary healthcare clinics implemented for Indigenous populations in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States?

Specific objectives were to: (1) scope the models of primary health care clinics for Indigenous populations (in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States) as described in the literature, (2) determine geographically where mobile primary health care clinics for Indigenous populations (in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States) have been implemented and, (3) examine the findings of any evaluations of mobile primary health care clinics for Indigenous populations (in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States) that have been published in the literature.

Methods

This systematic scoping review examines the evidence surrounding the use of mobile primary healthcare clinics implemented for Indigenous populations in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States [43]. This review was conducted in accordance with the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Reviewer’s Manual 2017: Methodology for JBI Scoping Reviews [44]. Search terms were developed using a PCC (Population, Concept, Context) mnemonic. The premise and methods of this review, have been published elsewhere [43]. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis extension for scoping reviews checklist (PRISMA-ScR) [45] was adhered to in the reporting of this review (Additional file 1_PRISMA-ScR checklist).

Search strategy

The JBI three step search process was utilized to develop the search strategy [44]. This involved a preliminary search undertaken in MEDLINE and CINAHL using keywords from the review question. A tailored search was then developed for each information source. For database search strategies, a combination of Boolean operators, truncations and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) were used (Additional file 2_ Academic database search strategies). Librarian assistance was provided for the development of the Ovid MEDLINE search strategy. Support was also provided in translating the search strategies into other databases. The reference lists of included studies were then searched for additional studies.

Databases searched included: Ovid MEDLINE, CINAHL (EBSCOhost), Embase (Elsevier), Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, SocINDEX (EBSCOhost), and INFORMIT.

Multiple platforms were used to search for unpublished studies and grey literature which included: Australian, Canadian, New Zealand, and the United States Indigenous-specific research websites, Indigenous organisational websites, health services and health research websites and open access websites, repositories and catalogues (Additional file 3_Grey Literature sources).

Inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria

Literature based on the following criteria was considered (Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria).

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Indigenous populations across the lifespan (infants, children, adolescents and adults) including; Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People (Australia), First Nations, Inuit, and Métis People (Canada), Māori People (New Zealand) and Native American, Native Hawaiian and Alaskan Native People (United States). | No exclusion criteria |

| Concept |

Mobile primary health care clinics implemented specifically for Indigenous populations Mobile clinics include a transportable clinic in the form of a van, truck or bus that has been equipped with health equipment |

Mobile primary health care clinics implemented for the general population Outreach services delivered by teams of fly in and fly out health professionals Delivery of health care services remotely through mobile technology |

| Context | Mobile primary health care clinics implemented within Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United States |

Mobile clinics delivering only specialist or rehabilitation services Not published in English |

No restrictions were placed on the quality or study design used. All types of literature, including media releases, webpages and news articles, were considered. Literature published since 1 January 2006 was considered in order to capture mobile clinics implemented since the ‘United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples’ (2007), where a greater international focus on the need to work in partnership with Indigenous populations to improve health outcomes, was established [46].

For consistency, the term ‘Indigenous’ has been used throughout this review to refer to all clans, tribes and communities of Indigenous populations within a global context. We acknowledge the diversity and uniqueness of all Indigenous tribes, clans and nations. No disrespect is intended by the use of this term.

Study selection and data extraction

Searches for published and unpublished literature were conducted by two researchers (HB and GE). Titles and abstracts retrieved were screened independently by two reviewers (HB and GE). Full text review and data extraction were then undertaken independently by the same two reviewers. For articles not meeting the inclusion criteria, reasons for exclusion were provided. The reference lists of included citations were then screened for additional citations in order to scope for all possible citations meeting the inclusion criteria.

The published data extraction table was used and modified to extract the longitude and latitude coordinates for locations serviced by the included mobile clinics from publicly available information [43]. The coordinates were then imported into ArcGIS ArcMap 10.6.1 (ESRI, CA, USA), a Geographical Information System (GIS), and mapped as point locations. Using a spatial join, the coordinates were linked with an underlying geographical characteristic described either as the Remoteness Structure (Australia) [47], Population Centre and Rural Area Classification 2016 (Canada) [48], or Urban status (United States) [49] to determine the classification of locations serviced by included mobile clinics. It is important to note that each country included in this review has a different rural area classification system. In Australia, Remoteness Structure comprises five categories: Major Cities of Australia, Inner Regional Australia, Outer Regional Australia, Remote Australia, and Very Remote Australia [47]. These classifications offer complete coverage of the Australian continent. Population centers in Canada are described as Small (1000-29,999), Medium (30,000-99,999) or Large (100,000 and over) with all other areas not classified, indicating very low population densities [48]. The urban footprint in the United States (high population density and urban land use) are described as Urban Clusters (2500-49,999) and Urbanised areas (> 50,000) [49]. Like Canada, all other areas are not classified. The spatial data used was based upon each modern state’s most recent census – 2016 for Australia and Canada (next census due 2021), and 2010 for the United States (next census due 2020).

Review findings were developed using a descriptive approach that addressed the review objectives, as per the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Reviewer’s Manual 2017: Methodology for JBI Scoping Reviews [44]. This involved examining the evidence that met the inclusion criteria, providing a summary of citations and synthesising extracted data where possible (e.g. geographical characteristics of location(s) where mobile clinics were implemented).

Results

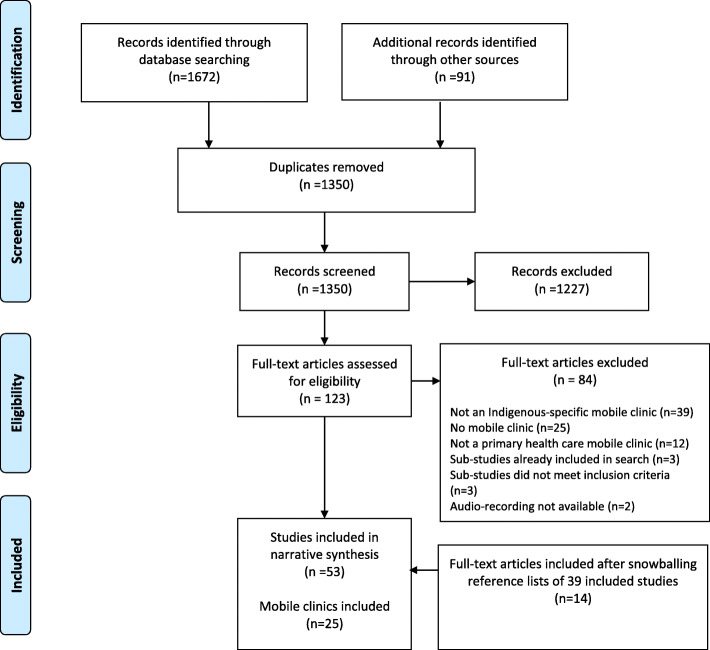

Database searches yielded 1672 citations. An additional 91 citations were retrieved from an extensive search of the grey literature and targeted organisational websites. A total of 1350 unique title and abstracts were screened, after duplicates were removed. The full texts of 123 citations were screened in accordance with the review criteria, identifying 39 relevant citations (Fig. 1– PRISMA Flow Diagram). An additional 14 citations were snow-balled from 39 included citations, resulting in a total of 53 included citations discussing 25 mobile clinics.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA diagram of the systematic review process for this review

Reasons for excluding citations were provided (Additional file 4_Excluded studies) and included: not an Indigenous-specific mobile clinic (n = 39), no mobile clinic (n = 25), not a primary health care mobile clinic (n = 12), sub-studies already included in search (n = 3), sub-studies did not meet the inclusion criteria (n = 3) and audio-recording not available (n = 2).

Information sources of citations meeting the review criteria (n = 53) included peer-reviewed journal articles (n = 18), conference presentations, papers or posters (n = 3), thesis (n = 1), independent report (n = 1), organisational annual reports or web pages (n = 25), and media releases or online news articles (n = 5).

Finding 1: geographical distribution of mobile clinics for Indigenous populations

Of the 25 mobile clinics included (many servicing multiple locations), most were implemented in Australia (n = 14), followed by the United States (n = 6) and Canada (n = 5). No primary health care clinics implemented specifically for Māori populations in New Zealand, were retrieved from the search (Table 2).

Table 2.

Included mobile primary health care clinics implemented for Indigenous populations

| Mobile clinic name | Citation | Year of implementation | Service provider | Country | State/Province |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health E Screen 4 Kids |

ABC 2008 [50] Elliot et al. 2010 [51] Nguyen et al. 2015 [52] Smith et al. 2013 [53] Smith et al. 2015 [54] Smith et al. 2012 [55] |

2009 | University of Queensland | Australia | Queensland |

| Bega Garnbirringu mobile clinic |

Alcohol and Other Drugs Knowledge Centre 2018 [56] Bega Garnbirringu Health Service 2018 [57] |

Not reported | Bega Garnbirringu Health Service | Australia | Western Australia |

| Maari Ma Health Aboriginal Corporation mobile clinic |

Australian Mobile Health Clinics Association 2015 [58] Parliament of Australia 2014 [59] |

2014 | Maari Ma Health Aboriginal Corporation | Australia | New South Wales |

| University of Queensland Indigenous Health Mobile Training Unit/Medical Outreach Boomerang van (MOB van) |

Australian Mobile Health Clinics Association 2015 [58] University of Queensland 2013 [60] Carbal Medical Service 2020 [61] Carbal Medical Services 2014 [62] |

2013 | University of Queensland, Health Workforce Australia and Carbal Health Service | Australia | Queensland |

| Moorditj Djena mobile podiatry clinic | Ballestas et al. 2014 [63] | 2011 | Derbarl Yerrigan Health Service and North and South Metropolitan Health Services | Australia | Western Australia |

| Western Desert Kidney Health mobile bus |

Bestel 2010 [64] Sinclair et al. 2016 [65] Jeffries-Stokes 2017 [66] |

2010 | University of Western Australia | Australia | Western Australia |

| Tulku Wan Wininn mobile clinic | Budja Budja Aboriginal Cooperative 2019 [40] | 2019 | Budja Budja Aboriginal Cooperative | Australia | Victoria |

| Queensland Aboriginal and Islander Health Council (QAIHC) mobile health clinic | Burgess & Buchannan 2013 [67] | 2013 | QAIHC | Australia | Queensland |

| Goondir Health Services Mobile Medical Clinic (MMC) |

Goondir Health Services 2020 [68] Goondir Health Services 2019 [69] |

2010 | Goondir Health Services | Australia | Queensland |

| Earbus mobile health clinics |

Ear bus 2020 [70] Ear bus 2018 [71] |

2014 | Earbus foundation of Western Australia | Australia | Western Australia |

| Chevron-Pilbara Ear Health Program |

Telethon Speech & Hearing 2020 [72] Higginbotham & Shur 2012 [73] Krishnaswamy, Monley & Kishida 2015 [74] Telethon Speech & Hearing 2019 [75] |

2011 | Telethon Speech & Hearing | Australia | Western Australia |

| Pi:Lu Bus | Evins 2018 [76] | 2018 | Riverland Aboriginal Health Service | Australia | South Australia |

| Murchison Outreach Services mobile clinic | Geraldton Regional Aboriginal Medical Service 2020 [77] | Not reported | Geraldton Regional Aboriginal Medical Service | Australia | Western Australia |

| Nhulundu Health Service Mobile Clinic | Nhulundu Health Service 2016 [78] | Not reported | Nhulundu Health Service | Australia | Queensland |

| Screening for Limb, I-eye, Cardiovascular, and Kidney complications of diabetes (SLICK vans) |

Jin 2014 [79] Oster et al. 2009 [80] Oster et al. 2010a [41] Virani et al. 2006 [81] |

2001–2010 | University of Alberta, First Nations and Health Canada | Canada | Alberta |

| Mobile Diabetes Screening Initiative (MDSi) |

Ralph-Campbell et al. 2009 [82] Oster et al. 2010b [83] Ralph-Campbell et al. 2011 [84] Toth 2014 [85] |

2003 | Alberta Health and Wellness, Northern Regional Health Authorities and University of Alberta | Canada | |

| Seabird Island Mobile Diabetes Telemedicine | Jin 2014 [79] | 2009 | Seabird Island Band | Canada | British Columbia |

| Manitoba Diabetes Integration Project (DIP) | Jin 2014 [79] | 2008 | Diabetes Integration Project, Inc. | Canada | Manitoba |

| Mobile Diabetes Telemedicine Clinic |

First Nations Health Authority 2019 [86] Dawson et al. 2009 [87] Jin 2014 [79] Carrier Sekani Family Services 2015 [88] |

2002 | Carrier Sekani Family Services | Canada | British Columbia |

| Great Plains Mobile Mammography Screening |

Roubidoux et al. 2018 [89] Roen et al. 2013 [90] Rural Health Information Hub 2019 [91] Indian Health Service 2020 [92] |

2006–2018 | Great Plains Area Indian Health Service | United States | North and South Dakota, Iowa and Nebraska |

| Tuba City Regional Health Care Corporation Mobile Health Program |

Mobile Healthcare Association 2020 [93] Bylander 2017 [94] Tuba City Regional Health Care Corporation 2019 [95] |

Not reported | Tuba City Regional Health Care Corporation | United States | Arizona |

| Winslow Indian Health Care Centre Medical Mobile Vehicle |

Mobile Healthcare Association 2020 [93] Winslow Indian Health Care Centre 2020 [96] |

2019 | Winslow Indian Health Care Center | United States | Arizona |

| Bay Clinic Mobile Health Unit |

Mobile Health Map 2020 [31] Bay Clinic 2020 [97] |

Not reported | Bay Clinic | United States | East Hawaii |

| Mniwiconi clinic and farm Mobile Clinic |

Mobile Health Map 2020 [31] Mniwiconi clinic and farm 2019 [98] |

Not reported | Mniwiconi clinic and farm | United States | North Dakota |

| Wisconsin Ho-Chunk Nation mobile clinic |

Children’s Health Fund 2012 [99] Mobile Healthcare Association 2020 [93] |

2012 | Ho-Chunk Nation Department of Health and Children’s Fund | United States | Wisconsin |

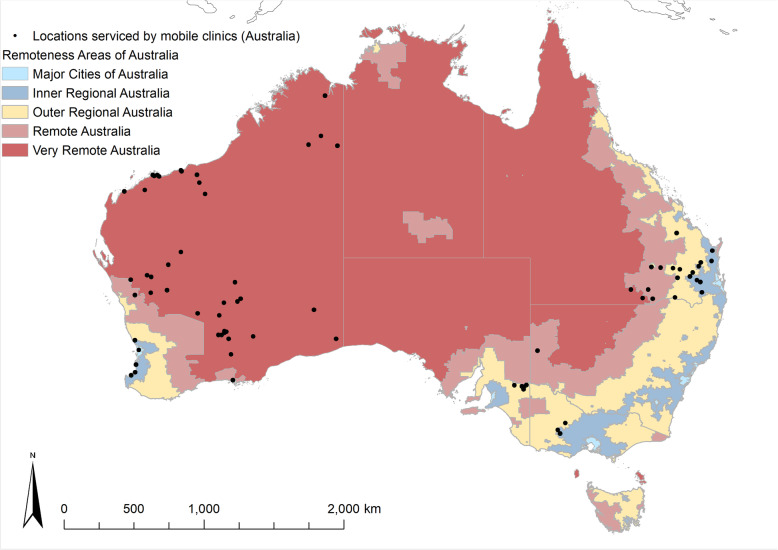

In Australia, the majority of locations serviced by mobile clinics were located in Very Remote Australia (n = 44; Table 3; Fig. 2). This was compared to Inner and Outer Regional Australia, which both had a similar amount of locations represented (n = 15 and n = 17 respectively). The remoteness classification with the least amount of locations was Major Cities of Australia (n = 2).

Table 3.

Summary of mobile clinics in Australia, Canada and the United States stratified by measure of remoteness or population size

| Australia (Remoteness Structure) | Frequency of locations serviced by mobile clinics (%) |

| Major Cities of Australia | 2 (2.3) |

| Inner Regional Australia | 15 (17.2) |

| Outer Regional Australia | 17 (19.5) |

| Remote Australia | 9 (10.4) |

| Very Remote Australia | 44 (50.6) |

| Total | 87 (100.0) |

| Canada (Population Centre and Rural Area Classification 2016) | |

| Large Urban (> 100,000) | 3 (1.9) |

| Medium (30,000-99,999) | 6 (3.7) |

| Small (1000–29,999) | 11 (6.8) |

| Outside (< 1000) | 142 (87.7) |

| Total | 162 (100.0) |

| United States (Urban areas) | |

| Urbanised Area (> 50,000) | 1 (2.8) |

| Urbanised Cluster (2500-49,999) | 11 (30.6) |

| Outside classification (< 2499) | 24 (66.7) |

| Total | 36 (100.0) |

Fig. 2.

Location of mobile clinics implemented for Indigenous populations in Australia

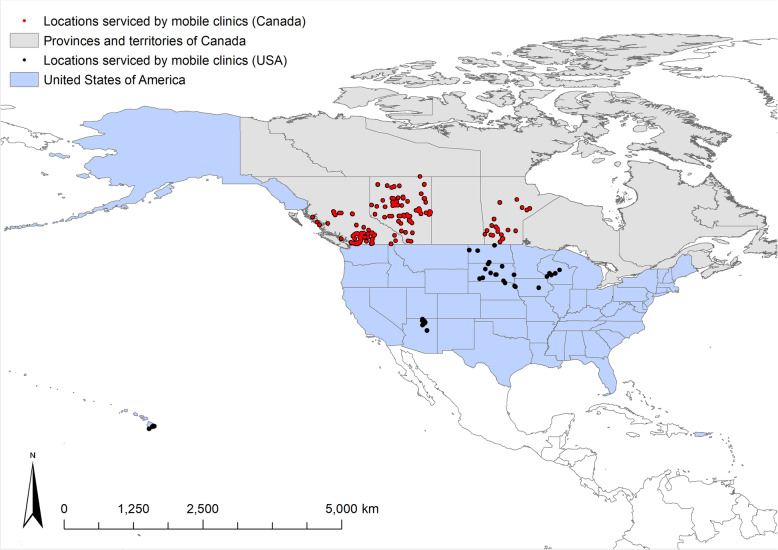

In Canada, most locations serviced by a mobile clinic were outside the formal classification of population centres (n = 142; Table 3; Fig. 3). There was a declining presence of mobile clinics with the increasing size of population centres. This was similar to the United States where two thirds of mobile clinic activity was in areas classified as being outside Urbanised Areas or Urbanised Clusters (n = 24, Table 3; Fig. 3). Locations with a mobile clinic presence were more numerous in Urbanised Clusters (n = 11) compared to Urbanised Areas (n = 1).

Fig. 3.

Location of mobile clinics implemented for Indigenous populations in Canada and the United States

Finding 2: primary health mobile clinic models for Indigenous populations

Of the mobile clinics included in the search (n = 25), the types of primary health care services and targeted populations varied (Table 3). These included delivering a broad range of general primary health care services (n = 13), providing disease specific services (e.g. diabetes management, screening and education n = 6, renal disease and other chronic disease screening n = 1, breast cancer screening n = 1, ear disease screening n = 3) and opportunistic health services and health promotion (n = 1) to Indigenous populations.

Most of the mobile clinics were implemented for Indigenous populations across the lifespan (n = 15), with fewer implemented for a specific age, gender group or population with chronic disease (infants, children or young people aged less than 18 years n = 4, people with diabetes n = 4, women n = 1, adults n = 1). There was evidence of Indigenous organisations governing and/or implementing 14 of the 25 mobile clinics (56%), with the remainder implemented in partnership with a non-Indigenous organisation or institution (n = 10). No information was provided about the involvement of Indigenous people in the implementation of one mobile clinic [67].

Information about the funding source(s) was retrieved for 19 of the 25 (76%) mobile clinics. Various sources were used to fund the mobile clinics which included governments, health organisations, commercial entities, universities and philanthropic organisations or foundations.

Finding 3: evidence of evaluated mobile clinics for Indigenous populations

Of the 25 included mobile clinics, 13 (52%) had evidence of some form of evaluation (Table 4). Of these 13 mobile clinics, most of the evaluation findings were disseminated in the non peer-reviewed literature or grey literature (n = 7 mobile clinics), with fewer evaluation findings disseminated in the peer-reviewed literature (n = 6 mobile clinics).

Table 4.

Included primary health care mobile clinic models for Indigenous populations

| MOBILE PRIMARY HEALTH CARE MODEL | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mobile health clinic name | Target population | Services providedwd | Indigenous community involvement | Evaluation methods | Participant sample | Evaluation Outcomes | Mobile clinic funding source |

| Health E Screen 4 Kids | Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children (aged > 18 years) | Screening, surveillance, primary care health checks and ENT surgery (e.g. taking out adenoids, putting in grommets) | In partnership |

(1) Feasibility study [51] (2) Cost-effectiveness analysis [52] (3) Pre and post-intervention analysis of hospital ENT service utilization [53] (4) Retrospective review of service activity from 2009 to 2011 [55] (5) Retrospective review of service activity from 2009 to 2014 [54] |

(1) Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children aged between 0 and 16 years receiving service between February and July 2009 (n = 743) (2) Annual costs of mobile van including services delivered, staff costs, maintenance costs and fixed costs (3) ENT outpatient appointments at Royal Children’s Hospital (2006–2008 n = 329) and (2009–2011 n = 105) (4) Children registered with the service (n = 1053) (5) Children registered with the service (n = 3105) |

(1) 41% of children failed one or more components of ear-screening assessment, 12% had signs of hearing impairment and 15% failed vision-screening assessment with 157 referrals to ENT specialists for review (2) Estimated cost for mobile van was higher than control (Deadly Ears Program), however generated high QALYs (15.94 v. 15.90) than control. Found to be a cost-effective strategy (3) Increase in routine assessment of children, increase in ENT surgical procedures locally and reduced need for families to travel to tertiary centers (4) High screening rates of children as a result of service with 2111 screening assessments undertaken and reduced wait times for ENT specialist review (5) Since service commenced, the number of screening assessments completed per year has increased (2009 n = 752, compared to 2014 n = 1454), increase in patients and decrease in proportion of children failing screening assessments and being referred to ENT. |

University of Queensland, Centre for Online Health and Royal Children’s Hospital Foundation |

| Bega Garnbirringu Health Service mobile clinic | All Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people | Primary care services delivered by GP, RN and AHWs such as wound care, health screenings (including sexual health), chronic disease management, pathology services (including Point of Care (PoC) testing), health education, annual Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health checks and visiting specialist services. | Implemented and delivered by an Aboriginal Community-Controlled Health Organisation | None to report | None to report | None to report | Not reported |

| Maari Ma Health Aboriginal Corporation mobile clinic | All Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people | Opportunistic health service delivery at community and sports events including health promotion and influenza vaccination | Implemented and delivered by an Aboriginal Community-Controlled Health Organisation | None to report | None to report | None to report | Australian Commonwealth Government |

| University of Queensland Indigenous Health Mobile Training Unit (MOB van) | All Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people | Primary health care including GP assessments, opportunistic health checks and school health checks | Implemented and delivered in partnership with an Aboriginal Community-Controlled Health Organisation | Descriptive statistics for 2014 annual report [62] | Clients of service | Multiple outcomes including 50% increase in the number of active clients, triple the number of GPs employed in 2014 compared to 2013, an increase in the number of completed health checks by 29% and funding secured for a new clinic in Warwick. | Queensland Health, Health Workforce Australia |

| Moorditj Djena mobile podiatry clinic | All Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people | Diabetes self-management and education including podiatric assessment. | Implemented and delivered by an Aboriginal Community -Controlled Health Organisation | Mixed methods including focus groups, interviews, review of program documents and descriptive analysis of clinical and administrative data [63]. | Clients of service (n = 702) |

Multiple outcomes including 3500 occasions of service in first 2.5 years and identified that outreach capacity is a strength. Multiple challenges including planning and coordination of outreach clinics, recruitment of staff and staff turnover, van procurement, launch and ongoing promotion of clinical service, ordering of equipment and logistical organisation, development of a database for electronic record keeping and negotiating fees to minimize costs to clients. |

National Partnership Agreement for ‘Closing the Gap’ in Indigenous Health Outcomes |

| Western Desert Kidney Health mobile bus | All Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people | Early detection of disease, chronic disease management and health promotion | Implemented and delivered in partnership with Aboriginal organisations |

(1) Qualitative interviews [65] (2) Community based participatory research project with annual cross sectional surveys over 3 years [66] |

(1) Aboriginal people living in remote communities receiving service (n = 26) (2) Aboriginal people from 10 locations |

(1) Found to be highly acceptable and effective means of disseminating the importance of prevention, early detection and management of diabetes and kidney disease (2) Multiple outcomes including high participation rate of Aboriginal people (79%), higher than predicated rates of diabetes, hypertension, hematuria and ACR and Aboriginal women found to be the highest risk group |

BHP Billiton Nickel West, University Western Australia, University of Notre Dame, Bega Garnbirringu Health Services, Goldfields Esperance GP Network and Wongutha Bimi Aboriginal Corporation |

| Budja Budja Aboriginal Cooperative | All Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people | Primary health care services including audiology, optometry, general health checks and health promotion and education | Implemented and delivered | None to report | None to report | None to report | Deakin University School of Medicine, Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet (Indigenous Affairs) and Budja Budja Aboriginal Coopertaive |

| Queensland Aboriginal and Islander Health Council (QAIHC) mobile health clinic | Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people | Primary health care services | Not reported | None to report | None to report | None to report | Queensland Gas Company (QGC) |

| Goondir Health Services Mobile Medical Clinic | Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, including school-aged children | Primary health care including disease prevention and chronic disease management, men’s and women’s health and health checks in schools | Delivered by an Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation | Descriptive statistics of services delivered [69] | Clinic data | Multiple outcomes including 187% increase in number of patients over 4 years. | Queensland Health, Broncos and Goondir Health Service |

| Earbus mobile health clinics | Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and young people | Primary and secondary services including ear screening, surveillance and treatment by GPs, audiologist and ENTs | Partners with Aboriginal Community-Controlled Health Service to deliver health services. | Regional descriptive statistics of services delivered [71] | Patient records | Multiple outcomes reporting on disease prevalence and screening rates in patient cohort stratified by geographical region | Earbus foundation of WA (charity) receiving multiple sources of funding (e.g. Neilson Foundation, ALCOA, MZI Resources and Ian Potter Foundation) |

| Chevron-Pilbara Ear Health Program | Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander school-aged children | Primary and secondary services including: ear health checks, hearing screening, Nurse Practitioner consultations and appointments with Ear Nose and Throat Specialists. | Partner with Aboriginal communities, Elders, schools and other health services to deliver health services. |

(1) Descriptive statistics of services delivered [73] (2) Descriptive statistics of attendance rates [74] (3) Descriptive statistics in annual report [75] |

(1) Patient and clinical data (2) Clinical data 2014–2015 (3) Clinical data 2011–2019 |

(1) Multiple outcomes including number of schools accessed and outcomes of hearing tests (pass, review, refer) (2) Increased attendance rates (40% pre July 2014 to 85.1% Jan-June 2015) (3) Multiple outcomes including 10,137 ear health screenings for 4881 people. |

Partners, Benefactors & Supporters; Channel 7 Telethon Trust, Chevron, Western Australian Government, Lottery West, The Hearing Research & Support Foundation, The Crommelin Family, Bill 7 Rhonda Wyllie Foundation, Jack Bendat, Tony Fini Foundation, Stan Perron Charitable Trust, Frank Tomasi Family Trust, Toybox International, LD Total |

| Pi:Lu Bus | All Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people | Primary health services including education | Aboriginal health service delivered | None to report | None to report | None to report | Bus provided by Transport South Australia |

| Murchison Outreach Services | All Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people | Primary care services including: general medical care, chronic disease and health promotion | Operated and delivered by an Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation | None to report | None to report | None to report | Not reported |

| Nhulundu Health Service Mobile Clinic | All Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people | Outreach medical services delivered by a GP, nurse and health worker | Operated and delivered by an Aboriginal medical service | None to report | None to report | None to report | Not reported |

| Screening for Limb, I-eye, Cardiovascular, and Kidney complications of diabetes (SLICK vans) | Alberta First Nations with diabetes | Diabetes screening, education and counselling service with point-of-care laboratory equipment and a retinal camera | Delivered in partnership with First Nations people |

(1) Descriptive analysis of patient cohort [80] (2) Descriptive longitudinal analysis of clinical indicators [41] (3) Descriptive quantitative analysis of key evaluation indicators [79] (4) Preliminary evaluation [81] |

(1) Participants who completed screening and survey (n = 743) (2) Patients screened with diabetes 2001–2007 (n = 2102) (3) Patient and clinic data between 2001 and 2007 (4) First Nations people with known diabetes 2001 to 2003 |

(1) Various clinical indicators, service utilization and health literacy. (2) Significant improvements in BMI, blood pressure, total cholesterol and HbA1c were identified (p < 0.01) in returning patients (3) Multiple outcomes including clinic visits (n = 830), annual costs avoided by patients and changes in clinical indicators (e.g. mass (kg), BMI, HbA1c, BP, MAP, LDL and total cholesterol) (4) Screened n = 1151 clients, modest improvements in program outcomes at 6 to 12 months |

Canadian Health Infostructure Partnership Program (CHIPP), Health Canada and Aboriginal Diabetes Initiative |

| Mobile Diabetes Screening Initiative (MDSi) | Metis adults (aged 18 years and over) and other remote Indigenous communities | Diabetes screening service | Implemented in partnership with Metis communities |

(1) Descriptive cross-sectional quantitative study with multiple measures (e.g. body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, blood pressure, blood glucose, blood lipids and HbA1c) [82] (2) Telephone survey [83] (3) Longitudinal analysis [84] |

(1) Patients screened with fasting glucose without a known history of diabetes (n = 266) between 2003 and 2007 (2) Adult patients (n = 175) between 2003 and 2008 (3) Clinical data from 2003 to 2009 |

(1) Prevalence of undiagnosed diabetes was 5.3% and pre-diabetes was 20.3% (CDA criteria) and 51.9% (ADA criteria) (2) 51% of participants indicated GP follow up after screening, with 66% of those who had been told they had probable diabetes, visiting a physician. (3) For returning adults with diabetes, significant improvements (p < 0.05) were observed in BMI, blood pressure, total cholesterol and HbA1c. |

Alberta Health and Wellness Program |

| Seabird Island Mobile Diabetes Telemedicine | People with diabetes residing in 70 First Nation reserve communities in southern mainland BC | Eye exam, PoC laboratory tests, nurse assessment, diabetes management and education | Directed by members from tribal councils | Descriptive quantitative analysis of key evaluation indicators [79] | Patient records with diabetes (n = 1160) 2010–2013 | Multiple outcomes including patient mean avoided cost ($260,027 per year) and mean difference in clinical indicators of diabetes (although not statistically significant): body mass − 0.5 kg, HbA1c −0.08%, systolic blood pressure 1.1 mmHg, diastolic blood pressure − 0.5 mmHg, Mean Arterial Pressure (MAP) 0.1 mmHg, Low Density Lipids (LDL) -0.13 mmol/L | Health Canada, Aboriginal Diabetes Initiative and British Columbia agencies including Fraser Health Authority and First Nations Health Authority. |

| Manitoba Diabetes Integration Project (DIP) | People with diabetes residing in 19 First Nation reserves in Manitoba | PoC laboratory tests, nurse assessment and diabetes management and education advice | Directed by members from tribal councils | Descriptive quantitative analysis of key evaluation indicators [79] | Patient records with diabetes (n = 2790) between 2008 and 2013 | Multiple outcomes including patient mean avoided cost ($272,289 per year) and change in mean difference of clinical indicators of diabetes: mass − 0.4 kg, HbA1c − 0.09%, systolic blood pressure − 1.6 mmHg, diastolic blood pressure − 1.0 mmHg, MAP −1.1 mmHg, LDL 0.09 mmol/L | Health Canada and Aboriginal Diabetes Initiative |

| Mobile Diabetes Telemedicine Clinic (MDTC) | People with diabetes residing in 59 First Nations communities in Northern British Columbia | Diabetes screening and management including eye exam, point of care (PoC) testing, nursing and dietitian assessments and education | Delivered by First Nations health service | Longitudinal cohort data analysis [79, 87] | Patient records from 2003 to 2009 | Modest improvements in some clinical outcomes (e.g. mean decline in body mass of 1.6 kg, mean decline in LDL was 0.3 mmol/L, mean absolute decline in A1c was 0.4%) | Health Canada and Aboriginal Diabetes Initiative |

| Great Plains Mobile Mammography Screening | Native American and Alaskan women | Mammography screening and referrals to tertiary centers | Delivered by Indian health services |

(1) Retrospective analysis of clinic records [89] (2) Retrospective analysis of clinical records [90] |

(1) Native Indian and Alaskan Native patient records 2007–2009 (n = 2640) (2) Complete patient records from 2007 to 2009 (n = 1771) |

(1) Incomplete patient reports were more frequent in mobile mammography than the fixed site (21.9% v. 15.2%) (2) Adherence to screening guidelines found in 39.86% of patients |

Not reported |

| Tuba City Regional Health Care Corporation Mobile Health Program | Native Indian people from Navajo, Hopi and San Juan Southern Paiute tribes | Primary Healthcare including immunizations and dental exams | Delivered by an Indian Tribal Organisation | None to report | None to report | None to report | Health Resources and Services Administration (Grant) |

| Winslow Indian Health Care Centre Medical Mobile Vehicle | Native Indian people | Primary care, dental, pharmacy, public health nursing, physical therapy, and some specialty services. | Delivered by Indian health service | None to report | None to report | None to report | Not reported |

| Bay Clinic Mobile Health Unit | East Hawai’i residents | Primary health care including preventative care, treatment, urgent care, immunization and vaccines, chronic disease management and dental services | Delivered by an East Hawai’I community health service | None to report | None to report | None to report | The Harry & Jeanette Weinberg Foundation, Inc., Hearst Foundations, Atherton Family Foundation, HDS Foundation, USDA/Rural Development, County of Hawai’i, McInerny Foundation, Ouida & Doc Hill Foundation, The Shippers Wharf Committee Trust |

| Mniwiconi clinic and farm Mobile Clinic | Indian tribal members | Health care | Indian delivered | None to report | None to report | None to report | Not reported |

| Wisconsin Ho-Chunk Nation mobile clinic | Indian babies, children and young people | Primary healthcare including acute care, laboratory services, vision and hearing screening, immunisations and other preventative care, education (e.g. asthma management, obesity prevention) | Delivered in partnership with an Indian Department of Health | None to report | None to report | None to report | Idol Gives Back Foundation (philanthropic) |

Of the evaluated mobile clinics, various approaches to undertaking an evaluation were used. Some evaluations produced multiple citations for a single mobile clinic (Table 4). Most of the evaluations used quantitative methods of evaluation (n = 11) including descriptive statistics (e.g. of clinical indicators, patient demographics, service data), surveys and longitudinal data. One of these included a cost-effectiveness analysis [52]. Two evaluations used a mixed methods approach consisting of both quantitative and qualitative methods of evaluation. Of the two mobile clinics evaluated using mixed methods (e.g. including qualitative methods of data collection such as interviews and focus group sessions), one evaluation did not provide qualitative data [63], whereas the other provided rich qualitative findings with evidence of engaging with the perspectives and voices of Indigenous people [65, 66]. Evaluations were heterogeneous in terms of evaluation methods and outcomes, making it difficult to compare findings. However, the participant sample included in evaluations was those receiving the services of the respective mobile clinic with a client or patient record (Table 4).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic scoping review examining primary health care mobile clinics implemented for Indigenous populations in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States. This review locates evidence of mobile clinics that have been implemented specifically for Indigenous populations (with the exception of New Zealand), and highlights the potential for mobile clinics to improve the accessibility of primary health care services. These findings are a valuable contribution to the growing body of international literature around the use of mobile clinics [28, 29, 32, 33, 36, 38]. Before discussing the implications of these findings, it is important to reiterate that Indigenous populations are diverse, have different languages, cultural identities, customs, lore and spiritual beliefs [16]. However, Indigenous populations in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States share the experience of colonization and require culturally safe health care embedded in the principles of self-determination [7, 16, 17, 46].

Likewise, there are key differences between the health care systems of Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States, which may account for variations in the implementation of mobile clinics specifically for Indigenous populations. Australia, Canada, and New Zealand have universal access to health care for all populations [100–102] which differs from the partially-funded health care system in the United States [103]. There are also complexities around the policies of each modern state regarding the funding of Indigenous-governed health services and programs [104]. In the United States, funding is allocated through the Indian Health Service (IHS), with a key criticism being the failure to provide sufficient resources to meet the health care needs (particularly primary health care needs) of a growing Native American, Native Alaskan, and Native Hawaiian population [17, 105]. In Australia and Canada, Indigenous health organisations (e.g. ACCHOs in Australia and on-reserve First Nations health services in Canada) receive some funding from governments to provide primary health care services to Indigenous populations, yet inequities exist in the distribution of funding (e.g. lack of funding for Métis People) and power imbalances between government and Indigenous health-organisations [17, 27, 104]. The funding structure in New Zealand differs again, with a more integrated approach of health service delivery through mainstream health services or private agencies and greater participation of Māori People in the process of informing the policy of District Health Boards (DHB) [17, 106]. The need to reform health care systems for the provision of equitable and culturally safe health care for Indigenous populations, has been widely discussed in the peer-reviewed literature [27, 104, 105].

There are also variations as to how population density is described in Australia, Canada, and the United States, which also has implications for interpreting the findings of this review (see Table 3). Australia’s Remoteness Structure [47] has a complete coverage of the continent, whereas Canada and the United States classify their urban areas by population size [48, 49]. Although there are other geographical methods for classifying population density (e.g. in Australia, Modified Monash Model [107]), this review has included classification methods used by decision-makers in each country at the time of analysis. For example, the Australian Government’s Rural Health Multidisciplinary Training (RHMT) Program [108] utilizes the Remoteness Structure [47] to guide investment to improve the recruitment and retention of health professionals in rural and remote Australia. Likewise, the Population Centre and Rural Area Classification 2016 (Canada) [48] and Urban status (United States) [49] are both based on the most recent census for each respective country and are used in government decision-making. Acknowledging these variations, this review identifies a pattern of increasing presence of mobile clinics in areas with lower population densities (see Table 3). Geographical gaps in service provision are evident (Figs. 2 and 3), indicating that the implementation of mobile clinics for Indigenous populations is not widespread.

There are also variations in the models of primary health care mobile clinics implemented for Indigenous populations. Most of the mobile clinics retrieved by this review targeted Indigenous populations across the lifespan, indicating a holistic family-centered model of primary health care, which is a preferred characteristic of Indigenous primary health care services [109]. Some mobile clinics targeted specific chronic diseases prevalent in Indigenous populations (e.g. diabetes) [110] and prevention of chronic disease for specific populations (e.g. otitis media in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children) [111]. Although there was some evidence of Indigenous organisational governance or involvement in the implementation of most mobile clinics, it was difficult to ascertain the degree of Indigenous community ownership. This is a key issue which has been discussed in another review examining chronic disease programs implemented for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations [112], and in the international literature examining health services and programs for Indigenous populations [27, 113, 114]. Indigenous community ownership of mobile clinics is imperative to ensuring culture, self-determination, and community participation are embedded in the delivery of primary health care services [109].

A paucity of published and publicly available evaluations of primary health care mobile clinics implemented specifically for Indigenous populations is also highlighted. This is despite a growing body of literature evaluating mobile clinics implemented for general populations and those at-risk for developing chronic disease, particularly in the United States [28, 31–33, 36, 39]. Although there is heterogeneity in the approaches used to evaluate mobile clinics implemented for Indigenous populations, there is some evidence that supports the potential for mobile clinics to increase attendance rates to services [54, 62, 69, 72] and improve clinical indicators (e.g. BMI, HbA1C) of targeted chronic diseases (e.g. diabetes) in Indigenous people accessing mobile clinic services [41, 79]. However, evaluation methods have relied heavily on the analysis of patient records and service data (see Table 4). The perspectives and insights of Indigenous people accessing mobile clinic services is largely absent. Findings support the need for high quality evaluations of Indigenous health programs which integrate qualitative evidence regarding the views and perspectives of Indigenous people [115]. An absence of qualitative data around the effectiveness of mobile clinics makes it difficult to know whether mobile clinics have potential to improve the cultural accessibility of primary health care services for Indigenous populations. This is a gap in existing knowledge which requires further research.

It is also difficult to examine how sustainable primary health care mobile clinics are when implemented for Indigenous populations. It is noted that the five diabetes mobile clinics retrieved from Canada were funded under the Aboriginal Diabetes Initiative (ADI), yet it is difficult to identify from the available literature as to whether all of these mobile clinics have been sustained over time under the original funding arrangement [79]. This highlights a key issue mediating the sustainability of mobile clinics in general, being the reliance on multiple funding sources (e.g. government and philanthropic) and/or short funding cycles [33]. There is also limited cost-effectiveness data around the use of mobile clinics for Indigenous populations [52]. Future research should include economic evaluations, coupled with an evaluation of the effectiveness and cultural acceptability of mobile clinics for Indigenous populations. This is imperative to informing the allocation of resources by decision-makers (e.g. governments and Indigenous-health organisations) to mobile clinics.

Limitations

Every effort has been made to search academic databases and grey literature sources for primary health care mobile clinics that have been implemented for Indigenous populations in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States. In Australia, it is known that a significant proportion of health research involving Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations is published in the grey literature [116]. A thorough search of grey literature information sources across key websites has been undertaken through the independent searching of two researchers and follow up of organisations, authors and researchers for additional information. Therefore, a limitation of this review is the manual processes required to undertake this search and the acknowledgement that there is the potential for some mobile clinics to be missed due to this.

Conclusions

This review identifies geographical gaps and a paucity of evidence around the implementation of primary health care mobile clinics for Indigenous populations in Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United States. The findings support the need to undertake rigorous mixed methods evaluations of primary health care mobile clinics implemented specifically for Indigenous populations. Through the involvement of Indigenous people in the evaluation process, greater insights will be obtained as to the potential for mobile clinics to improve access to culturally safe and holistic primary health care services. It is important for organisations implementing primary health mobile clinics for Indigenous populations, to share their experiences by making evaluations publicly available, ideally through the peer-reviewed literature. This is essential in developing evidence around innovative models of health care that have the potential to improve health outcomes for Indigenous people globally. Dissemination of evaluation evidence concerning mobile clinics will also be invaluable to decision-makers, including Indigenous health organisations, who are considering allocating resources to a primary health care mobile clinic.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the contribution of Deakin University librarians Rebecca Muir, Fiona Russell and Blair Kelly, in providing guidance on the development of the initial search strategy and use of academic databases and information sources. We also acknowledge the role of Budja Budja Aboriginal Cooperative (Halls Gap, Victoria, Australia), including Chief Executive Officer, Tim Chatfield, Djab Wurrung man, and Independent Director and Secretary, Roman Zwolak, in assisting with formulating the review question. This systematic scoping review was undertaken as part of Hannah Beks’ thesis, in order to fulfil the requirements of the Doctor of Philosophy (PhD).

Abbreviations

- ACCHO

Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation

- JBI

Joanna Briggs Institute

- PCC

Population, Concept, Context

- PRISMA - ScR

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Scoping Reviews

Authors’ contributions

HB led the scoping review design, screening of data, data extraction, analysis of data, and drafting of the manuscript. GE was involved in the scoping review design, screening of data, data extraction, analysis of data and drafting of the manuscript. RC and VLV were involved in the scoping review design, analysis of data and drafting of the manuscript. VLV produced the geographical outputs and analysis. JC, FM and YP were involved in the analysis of data, and drafting of the manuscript which included a review for cultural appropriateness in the reporting of outcomes. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

No funding was received for this review. Robyn A Clark is supported by a Heart Foundation Future Leader Fellowship (APP ID. 100847). Hannah Beks, Geraldine Ewing, and Vincent L Versace are funded by the Australian Government Department of Health Rural Health Multidisciplinary Training (RHMT) Program.

Availability of data and materials

Geographical locations of mobile clinics are publicly available.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Hannah Beks, Email: hannah.beks@deakin.edu.au.

Geraldine Ewing, Email: g.ewing@deakin.edu.au.

James A. Charles, Email: james.charles@deakin.edu.au

Fiona Mitchell, Email: fiona.mitchell@deakin.edu.au.

Yin Paradies, Email: yin.paradies@deakin.edu.au.

Robyn A. Clark, Email: robyn.clark@flinders.edu.au

Vincent L. Versace, Email: vincent.versace@deakin.edu.au

References

- 1.UNICEF, World Health Organization . International conference on primary health care. Declaration of Alma-Ata: international conference on primary health care [internet] Geneva: World Health Organization; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Primary Health Care Research and Information Service . Primary health care matters. Adelaide: Primary Health Care Research & Information Service; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mitchell LJ, Ball LE, Ross LJ, Barnes KA, Williams LT. Effectiveness of dietetic consultations in primary health care: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2017;117(12):1941–1962. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2017.06.364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Black RE, Taylor CE, Arole S, Bang A, Bhutta ZA, Chowdhury AMR, et al. Comprehensive review of the evidence regarding the effectiveness of community-based primary health care in improving maternal, neonatal and child health: 8. Summary and recommendations of the expert panel. J Glob Health. 2017;7(1):433–444. doi: 10.7189/jogh.07.010908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Álvarez-Bueno C, Rodríguez-Martín B, García-Ortiz L, Gómez-Marcos MÁ, Martínez-Vizcaíno V. Effectiveness of brief interventions in primary health care settings to decrease alcohol consumption by adult non-dependent drinkers: a systematic review of systematic reviews. Prev Med. 2015;76(Suppl 1):33–38. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reynolds R, Dennis S, Hasan I, Slewa J, Chen W, Tian D, et al. A systematic review of chronic disease management interventions in primary care. BMC Fam Pract. 2018;19(1):1–13. doi: 10.1186/s12875-017-0692-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paradies Y. Colonisation, racism and Indigenous health. J Popul Res. 2016;33(1):83–96. doi: 10.1007/s12546-016-9159-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davy C, Harfield S, McArthur A, Munn Z, Brown A. Access to primary health care services for Indigenous peoples: a framework synthesis. Int J Equity Health. 2016;15(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12939-016-0450-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marrone S. Understanding barriers to health care: a review of disparities in health care services among Indigenous populations. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2007;66(3):188–198. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v66i3.18254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Filippi MK, Perdue DG, Hester C, Cully A, Cully L, Greiner A, et al. Colorectal Cancer screening practices among three American Indian communities in Minnesota. J Cult Divers. 2016;23(1):21–27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Penchansky R, Thomas JW. The concept of access: definition and relationship to consumer satisfaction. Med Care. 1981;19(2):127–140. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198102000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saurman E. Improving access: modifying Penchansky and Thomas’s theory of access. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2015;21(1):36–39. doi: 10.1177/1355819615600001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jennings W, Bond C, Hill PS. The power of talk and power in talk: a systematic review of Indigenous narratives of culturally safe healthcare communication. Aust J Prim Health. 2018;24(2):109–115. doi: 10.1071/PY17082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greenwood M, Lindsay N, King J, Loewen D. Ethical spaces and places: Indigenous cultural safety in British Columbia health care. AlterNative. 2017;13(3):179–189. doi: 10.1177/1177180117714411. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ellison-Loschmann L, Pearce N. Improving access to health care among New Zealand’s Maori population. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(4):612–617. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.070680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.United Nations . State of the World's Indigenous peoples [internet] New York: United Nations; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pulver L, Ring I, Waldon W, Whetung V, Kinnon D, Graham C, et al. Indigenous health – Australia, Canada, Aotearoa New Zealand and the United States - laying claim to a future that embraces health for us all. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anderson I, Robson B, Connolly M, Al-Yaman F, Bjertness E, King A, et al. Indigenous and tribal peoples' health (the lancet–Lowitja Institute global collaboration): a population study. Lancet. 2016;388(10040):131–157. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00345-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gibson O, Lisy K, Davy C, Aromataris E, Kite E, Lockwood C, et al. Enablers and barriers to the implementation of primary health care interventions for Indigenous people with chronic diseases: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2015;10(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0261-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bath J, Wakerman J. Impact of community participation in primary health care: what is the evidence? Aust J Prim Health. 2015;21(1):2–8. doi: 10.1071/PY12164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reeve C, Humphreys J, Wakerman J, Carter M, Carroll V, Reeve D. Strengthening primary health care: achieving health gains in a remote region of Australia. Med J Aust. 2015;202(9):483–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Panaretto KS, Dellit A, Hollins A, Wason G, Sidhom C, Chilcott K, et al. Understanding patient access patterns for primary health-care services for Aboriginal and islander people in Queensland: a geospatial mapping approach. Aust J Prim Health. 2017;23(1):37–45. doi: 10.1071/PY15115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation (NACCHO) Annual Report 2018–2019. Canberra: National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation (NACCHO); 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Campbell MA, Hunt J, Scrimgeour DJ, Davey M, Jones V. Contribution of Aboriginal community-controlled health Services to improving Aboriginal health: an evidence review. Aust Health Rev. 2018;42(2):218–226. doi: 10.1071/AH16149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gomersall JS, Gibson O, Dwyer J, O'Donnell K, Stephenson M, Carter D, et al. What Indigenous Australian clients value about primary health care: a systematic review of qualitative evidence. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2017;41(4):417–423. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beaton A, Manuel C, Tapsell J, Foote J, Oetzel JG, Hudson M. He Pikinga Waiora: supporting Māori health organisations to respond to pre-diabetes. Int J Equity Health. 2019;18(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12939-018-0904-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lavoie JG, Dwyer J. Implementing Indigenous community control in health care: lessons from Canada. Aust Health Rev. 2016;40(4):453–458. doi: 10.1071/AH14101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yu SWY, Hill C, Ricks ML, Bennet J, Oriol NE. The scope and impact of mobile health clinics in the United States: a literature review. Int J Equity Health. 2017;16(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12939-017-0671-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abdel-Aleem H, El-Gibaly OMH, El-Gazzar A, Al-Attar GST. Mobile clinics for women's and children's health. Cochrane Datab Syst Rev. 2016, Issue 8. Art. No.: CD009677. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD009677.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Barker C, Bartholomew K, Bolton P, Walsh M, Wignall J, Crengle S, et al. Pathways to ambulatory sensitive hospitalisations for Māori in the Auckland and Waitemata regions. N Z Med J. 2016;129(1444):15–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mobile Health Map . Find Clinics Mobile Health Map. Boston: Harvard Medical School; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Malone NC, Williams MM, Smith Fawzi MC, Bennet J, Hill C, Katz JN, et al. Mobile health clinics in the United States. Int J Equity Health. 2020;19(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12939-020-1135-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Attipoe-Dorcoo S, Delgado R, Gupta A, Bennet J, Oriol NE, Jain SH. Mobile health clinic model in the COVID-19 pandemic: lessons learned and opportunities for policy changes and innovation. Int J Equity Health. 2020;19(1):1–5. doi: 10.1186/s12939-020-01175-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gutierrez-Padilla JA, Mendoza-Garcia M, Plascencia-Perez S, Renoirte-Lopez K, Garcia-Garcia G, Lloyd A, et al. Screening for CKD and cardiovascular disease risk factors using Mobile clinics in Jalisco, Mexico. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;55(3):474–484. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dhore PB, Tiwari S, Mandal MK, Purandare VB, Sayyad MG, Pratyush DD, et al. Design, implementation and results of a mobile clinic-based diabetes screening program from India. J Diabetes. 2016;8(4):590–593. doi: 10.1111/1753-0407.12387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bertoncello C, Cocchio S, Fonzo M, Bennici SE, Russo F, Putoto G. The potential of mobile health clinics in chronic disease prevention and health promotion in universal healthcare systems. An on-field experiment. Int J Equity Health. 2020;19(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12939-020-01174-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rassekh BM, Shu W, Santosham M, Burnham G, Doocy S. An evaluation of public, private, and mobile health clinic usage for children under age 5 in Aceh after the tsunami: implications for future disasters. Health Psychol Behav Med. 2014;2(1):359–378. doi: 10.1080/21642850.2014.896744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McGowan CR, Baxter L, Deola C, Gayford M, Marston C, Cummings R, et al. Mobile clinics in humanitarian emergencies: a systematic review. Conflict Health. 2020;14(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s13031-019-0247-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hill CF, Powers BW, Jain SH, Bennet J, Vavasis A, Oriol NE. Mobile health clinics in the era of reform. Am J Manag Care. 2014;20(3):261–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Budja Budja Aboriginal Cooperative. New Mobile clinical health Van [internet]. Halls Gap: Budja Budja Aboriginal Cooperative; 2020. Available from: https://budjabudjacoop.org.au/new-mobile-clinical-health-van-april-2019/. Accessed 31 Jan 2020.

- 41.Oster RT, Shade S, Strong D, Toth EL. Improvements in indicators of diabetes-related health status among first nations individuals enrolled in a community-driven diabetes complications mobile screening program in Alberta, Canada. Can J Public Health. 2010;101(5):410–414. doi: 10.1007/BF03404863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Conway J, Lawn S, Crail S, McDonald S. Indigenous patient experiences of returning to country: a qualitative evaluation on the country health SA Dialysis bus. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):1–13. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3849-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Beks H, Ewing G, Muir R, Charles J, Paradies Y, Clark R, et al. Mobile primary health care clinics for Indigenous populations in Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United States: a scoping review protocol. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2020;18(5):1077–1090. doi: 10.11124/JBISRIR-D-19-00057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Peters MDJ, Godfrey C, McInerney P, Baldini Soares C, Khalil H, Parker D. Chapter 11: Scoping Reviews. In: Areomataris E, Munn Z, editors. Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer’s Manual. Adelaide: Joanna Briggs Institute; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O'Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–473. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.United Nations General Assembly . United Nations declaration on the rights of Indigenous peoples [internet] New York: United Nations General Assembly; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) Remoteness structure. Canberra: ABS; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Canada Statistics . Population Centre and Rural Area Classification 2016. Ontario: Statistics Canada; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 49.United States Census Bureau Department of Commerce . TIGER/Line Shapefile, 2016, 2010 nation, U.S., 2010 census urban area national [internet]. United States Census Bureau. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 50.ABC News . Mobile health clinic to tour Indigenous communities. Ultimo: ABC News; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Elliott G, Smith AC, Bensink ME, Brown C, Stewart C, Perry C, et al. The feasibility of a community-based mobile telehealth screening service for Aboriginal and Torres Strait islander children in Australia. Telemed J E-health. 2010;16(9):950–956. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2010.0045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nguyen KH, Smith AC, Armfield NR, Bensink M, Scuffham PA. Cost-effectiveness analysis of a Mobile ear screening and surveillance service versus an outreach screening, surveillance and surgical Service for Indigenous Children in Australia. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):1–16. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Smith AC, Armfield NR, Wu W-I, Brown CA, Mickan B, Perry C. Changes in paediatric hospital ENT service utilisation following the implementation of a mobile, Indigenous health screening service. J Telemed Telecare. 2013;19(7):397–400. doi: 10.1177/1357633X13506526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Smith AC, Bradford N, Caffery LJ, Armfield NR, Brown C, Perry C. Monitoring ear health through a telemedicine-supported health screening service in Queensland. J Telemed Telecare. 2015;21(8):427–430. doi: 10.1177/1357633X15605407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Smith AC, Armfield NR, Wu W-I, Brown CA, Perry C. A mobile telemedicine-enabled ear screening service for Indigenous children in Queensland: activity and outcomes in the first three years. J Telemed Telecare. 2012;18(8):485–489. doi: 10.1258/jtt.2012.gth114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Alcohol and Other Drugs Knowledge Centre . Bega Garnbirringu Health Service Mobile Clinic. Mt Lawley: Alcohol and Other Drugs Knowledge Centre; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bega Garnbirringu Health Sevice . Mobile Clinic. Kalgoorlie: Bega Garnbirringu Health Service; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Australian Mobile Health Clinics Association . Australian and State Government Policy Support for Mobile Health Care. Gordon: Australian Mobile Health Clinics Association; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Parliament of Australia . New mobile clinic receives support from the Australian Government. Canberra: Parliament of Australia; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 60.University of Queensland . Mobile Indigenous health clinic reaches out to underserviced communities. Brisbane: The University of Queensland; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Carbal Medical Services . Health Service Programs. Toowoomba: Carbal Medical Services; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Carbal Medical Services . Annual Report. Toowoomba; Carbal Medical Services. 2014. pp. 5–15. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ballestas T, McEvoy S, Swift-Otero V, Unsworth M. A metropolitan Aboriginal podiatry and diabetes outreach clinic to ameliorate foot-related complications in Aboriginal people. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2014;38(5):492–493. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bestel M. Ancient art delivers modern health advice. Aust Nurs J. 2010;18(6):42–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sinclair C, Stokes A, Jeffries-Stokes C, Daly J. Positive community responses to an arts-health program designed to tackle diabetes and kidney disease in remote Aboriginal communities in Australia: a qualitative study. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2016;4:307–312. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jeffries-Stokes C. The Western Desert kidney health project. University of Western Australia. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Burgess S, Buchanan K. Mobile health clinic to help boost Indigenous health [internet]. ABC News. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Goondir Health Services . Mobile Health Promotion Van. Dalby: Goondir Health Services; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Goondir Health Services . Goondir Health Services Annual Report 2017–2018. Dalby: Goondir Health Services; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Earbus Foundation of WA . Earbus program. Northbridge: Earbus Foundation of WA; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Earbus Foundation of WA . 2018 Annual report. Northbridge: Earbus Foundation of WA; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Telethon Speech & Hearing . Chevron Pilbara Ear Health Program. Wembley: Telethon Speech & Hearing; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Higginbotham P. Otitis media in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in Western Australia: analyses of recent data of the Telethon Speech and Hearing mobile ear clinic program. Presented: Australian Otitis Media Conference. Fremantle; 2012.

- 74.Krishnaswamy J, Monley P, Kishida Y. Optimising Children's Specialist Ear Health Clinic Attendance Rates in Rural and Remote ATSI Communities. Presented: Aboriginal Health Conference: Healthy Families - Healthy Futures. Perth; 2015.

- 75.Telethon Speech & Hearing . Annual Report 2018. Wembley: Telethon Speech & Hearing; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Evins B. Colourful health bus provides medical services to Aboriginal and Torres Strait islanders in remote areas. Ultimo: ABC Riverland; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Geraldton Regional Aboriginal Medical Service . Mobile Clinic. Geraldton: Geraldton Regional Aboriginal Medical Service; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Nhulundu Health Service . Nhulundu expands services to Biloela. Gladstone: Nhulundu Health Service; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jin A. Aboriginal diabetes initiative (ADI) funded Mobile screening and management projects - synthesis report Surrey. British Columbia: Health Canada; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Oster RT, Virani S, Strong D, Shade S, Toth EL. Diabetes care and health status of first nations individuals with type 2 diabetes in Alberta. Can Fam Physician. 2009;55(4):386–393. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Virani S, Strong D, Tennant M, Greve M, Young H, et al. Rationale and implementation of the SLICK project: screening for limb, I-eye, cardiovascular and kidney (SLICK) complications in individuals with type 2 diabetes in Alberta's first nations communities. Can J Public Health. 2006;97(3):241–247. doi: 10.1007/BF03405595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ralph-Campbell K, Oster RT, Connor T, Pick M, Pohar S, Thompson P, et al. Increasing rates of diabetes and cardiovascular risk in Métis settlements in northern Alberta. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2009;68(5):433–442. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v68i5.17382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Oster RT, Ralph-Campbell K, Connor T, Pick M, Toth EL. What happens after community-based screening for diabetes in rural and Indigenous individuals? Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2010;88(3):28–31. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ralph-Campbell K, Oster R, Conner T, Toth E. Emerging longitudinal trends in health indicators for rural residents participating in a diabetes and cardiovascular screening program in northern Alberta, Canada. Int J Fam Med. 2011;2011:1–6. doi: 10.1155/2011/596475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Toth E. Mobile diabetes screening initiative through the years [internet]. MDSi wrap up meeting. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 86.First Nations Health Authority . Warriors meet again. Vancouver: First Nations Health Authority; 2019. [Google Scholar]