Abstract

Background/Aim: Accurate prediction of radiotherapy results is indispensable for the individualized selection of treatment modalities of cancer. We examined the application of the artificial neural network (ANN) model in predicting radiotherapy results using clinical factors and immunohistochemical staining of Ku70 as inputs. Patients and Methods: We analyzed 79 prostate cancer patients with localized adenocarcinoma treated with radiotherapy between August 2001 and October 2010. We also analyzed 46 hypopharyngeal cancer patients with squamous cell carcinoma treated with radiotherapy between March 2002 and December 2009. The properly trained ANN analysis using a standard feedforward, back-propagation neural network was used to predict the radiotherapy treatment results. Results: The areas under the receiver-operating characteristic curve (AUC) were 0.939 for patients treated with intensity modulated radiotherapy (IMRT)+androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), 0.803 for IMRT alone, and 0.960 for 3D-conformal radiotherapy (CRT) alone in prostate cancer. Sensitivity and specificity were 85.7% and 90.4% for IMRT+ADT, 75.0% and 88.5% for IMRT alone, and 92.3% and 100% for 3D-CRT alone. The AUC was 0.901 for hypopharyngeal cancer. Sensitivity and specificity were 66.7% and 88.2%, respectively. Conclusion: We demonstrated a possibility to predict the radiotherapy treatment results in prostate and hypopharyngeal cancer using ANN in combination with Ku70 expression and clinical factors as inputs.

Keywords: Prediction, artificial neural network, ku70, radiotherapy, prostate cancer, hypopharyngeal cancer

Accurate prediction of the results of radiotherapy is important to achieve individualized radiotherapy. DNA is the principal target for radiation-induced cell death. Mutations in the DNA repair mechanisms, such as in base excision repair, homologous recombination or nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ) genes can all lead to increased radiosensitivity (1). Therefore, comprehensive genome and miRNA analysis is best to be performed before radiotherapy (2,3). As expected, these analyses are expensive and can only be performed at designated institutions, which creates the additional issue of time delay to results.

We have previously examined the relationship between the outcome of radiotherapy in relation to the expression of NHEJ proteins involved in the repair of DNA double strand breaks (4) in prostate biopsy specimens, demonstrating an improval in the prediction of prostate specific antigen (PSA) failure by combining an immunohistochemical examination of Ku70 with clinical parameters (5), such as the Gleason score and the D’Amico risk classification (6).

The artificial neural network (ANN) is a machine learning classifier that uses a computational model simulating the behavior of neural networks in the human brain. The ANN can learn the relationship between input data and teaching data (7). In other words, a mathematical model representing the relationship between the input and teaching data can be constructed by changing the weighting factors connecting neurons in the ANN through a learning process. The ANN has recently been applied to a variety of pattern recognitions and data classifications in the diagnostic field (8). Using clinical factors and immunohistochemical staining for Ku70 as input, we investigated the application of ANNs to predict radiotherapy outcomes.

Patients and Methods

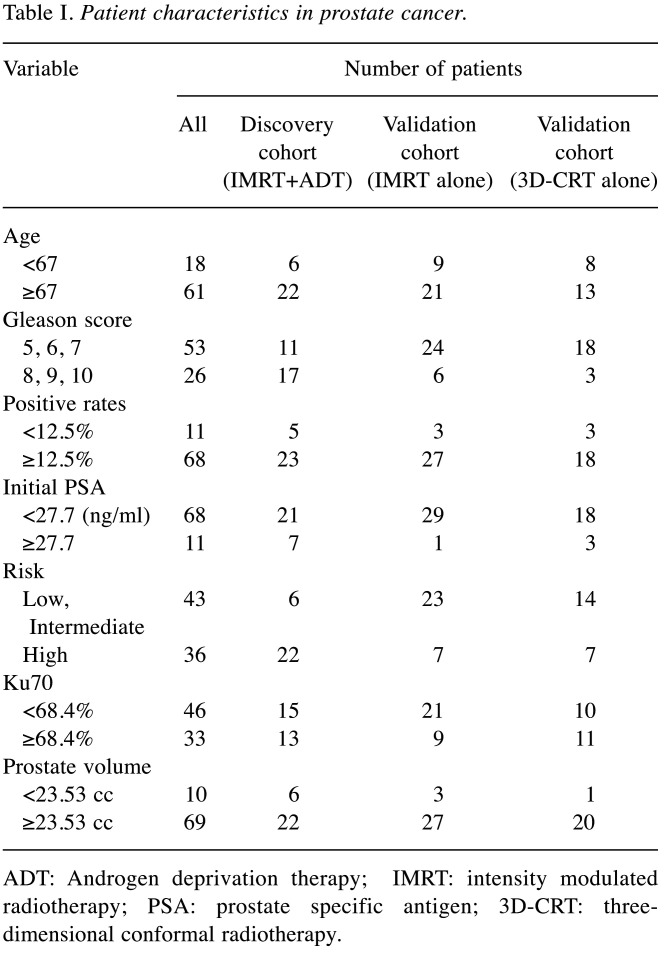

Patients. Concerning prostate cancer, 58 patients with localized adenocarcinoma treated with intensity modulated radiotherapy (IMRT) between August 2007 and October 2010 and 21 patients treated with three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy (3D-CRT) between August 2001 and May 2007 were analyzed. Patient characteristics are listed in Table I. Patients were divided into two groups, with the cut-off value based on the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve of each variable.

Table I. Patient characteristics in prostate cancer.

ADT: Androgen deprivation therapy; IMRT: intensity modulated radiotherapy; PSA: prostate specific antigen; 3D-CRT: threedimensional conformal radiotherapy.

Patients with prostate cancer were separated into three cohorts for discovery, and two cohorts for validation. The discovery cohort consisted of patients treated with IMRT and androgen deprivation therapy (ADT). The validation cohort consisted of patients treated with IMRT without ADT. The other validation cohort involved patients treated with 3D-CRT without ADT. The Phoenix definition was used for biochemical relapse (nadir+2 ng/ml).

Concerning hypopharyngeal cancer, 46 patients with squamous cell carcinoma were treated with radiotherapy between March 2002 and December 2009 were analyzed. Regarding tumour, node, and metastasis (TNM) stage (7th edition) (9), 4 patients had stage I disease, 10 had stage II, 8 had stage III and 35 had stage IV disease (Table II). Most patients (75%) had stage III or IV disease.

Table II. Patient characteristics in hypopharyngeal cancer.

The median follow-up time to the last contact or mortality was 78 months in patients treated with IMRT+ADT (discovery cohort), 80 months in IMRT without ADT (validation cohort), and 120 months in 3D-CRT (validation cohort) for prostate cancer patients, and 62 months for hypopharyngeal cancer patients.

All patients provided an informed consent to participate in this study. This study was approved by the ethics committee of Sapporo Medical University.

Treatment. With regards to prostate cancer, details of the radiation treatment planning of IMRT and 3D-CRT have been described previously (10). For IMRT, the dose covering 95% of the target volume (D95) was set at 76 Gy and was delivered in 38 fractions. The clinical target volume (CTV) was defined according to risk, as evaluated by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines (11). For 3D-CRT, the dose was set at 70 Gy at the isocenter and was delivered in 35 fractions. Neoadjuvant ADT was performed in 28 patients before IMRT. Radiotherapy usually commenced 3 months after neoadjuvant ADT. Adjuvant ADT was performed in 16 patients. The duration of adjuvant ADT was i) <1 year in 2 patients, ii) 2-3 years in 11 patients, and iii) >5 years in 3 patients. The treatment method for hypopharyngeal tumor has been described in detail previously (12). Briefly, in 51 of the 57 patients, chemotherapy was administered concurrently with radiotherapy. Six patients were treated with radiotherapy alone. The chemotherapy consisted of 5-Fluorouracil and cisplatin (FP) or tegafur/gimeracil/oteracil (S-1). A dose of 50 Gy was administered in 25 fractions to the primary tumor and regional lymph nodes. Doses of 10-20 Gy were usually added to the primary tumor with reduced fields after the completion of 50 Gy.

Immunohisotochemical staining. Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded specimens from pretreated needle biopsies performed before treatments were assessed for Ku70. Eight to 14 biopsy specimens were collected per patient. Among these biopsy specimens taken, two specimens that had prostate cancer cells were selected and observed. Immunohistochemical staining was carried out as previously described using the Ku70 monoclonal antibody (MC-351, clone N3H10, Kamiya Biochemical Company, Tukwila, WA, USA) (13). Numbers of cells were counted in the most intensely stained area using an Olympus BX51 high-power view (×400) (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). The number of cells that stained positive for Ku70 was determined by scoring two microscopic fields with >250 tumor cells each, determining the percentages of Ku70-positive cells. The values of immunohistochemical staining were evaluated by two researchers without prior knowledge of either radiosensitivity or treatment outcome.

Statistical analysis. The MLR model was used for the univariate and multivariate analyses. A significance level of 0.05 was used throughout the study. All data were analyzed using R, version 2.3.0 (R Foundation, Vienna, Austria).

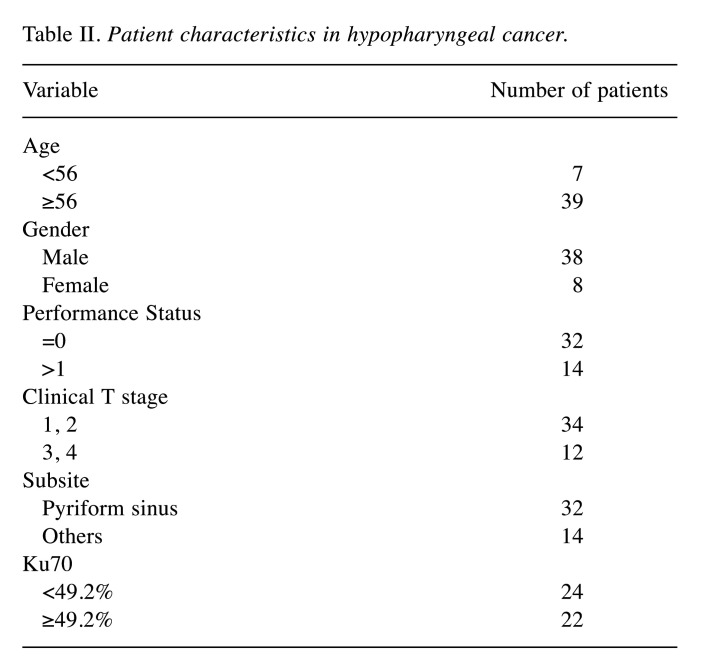

Artificial neural network. The ANN model has a standard feedforward, backpropagation neural network with three layers: i) an input layer, ii) a hidden layer and iii) an output layer. Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) networks are a new tool for designing a special class of layered feedforward networks (14). The input layer contains the source neurons and the output layer contains the result neurons. These two layers connect the network to the outside world. In addition, because there is no direct access to the MLP network, there are usually one or more additional neuron layers, called hidden neurons. Hidden neurons extract important features in the input data (7). The discovery cohort uses validation techniques to optimize the time to complete a network training session. Patients in the discovery cohort were automatically grouped into estimation, validation, and test datasets. The estimation data set is used to train the model and the validation data set is used to evaluate the model performance. The neural network is then optimized using the training dataset. Finally, a separate test dataset is used to determine when to stop training to reduce overfitting. The training cycle repeats itself until the test errors are no longer reduced (15). We trained the ANN and tested its ability to predict PSA relapse using the six clinical factors and Ku70 expression in tumor cells of the discovery cohort (IMRT+ADT). We chose the patients treated with IMRT+ADT as a discovery cohort, and the other groups (IMRT without ADT and 3DCRT without ADT) as validation cohorts, in order to examine whether an ANN is applicable to patients under different treatment. For this purpose, we constructed an ANN with input units of the seven prognostic factors, ten hidden units, and one output unit corresponding to the predicted value of the PSA relapse rate (Figure 1). We included statistically insignificant clinical factors in the multivariate analysis as input, since these factors may have significance in the ANN analysis. We did not include radiation doses or use of ADT as input factors as they were similar in each cohort. Last, we did not include T-stage as an input as in the diagnosis of T- stage, trans-rectal ultrasonography was not performed in all patients. In prostate cancer, the input variables were: i) age, ii) Gleason score, iii) positive rates of needle biopsy, iv) initial prostate-specific antigen (PSA), v) D’Amico risk classification, vi) Ku70, and vii) prostate volume and the output variable was the biochemical relapse. In hypopharyngeal cancer, the input variables were: i) age, ii) sex, iii) performance status (PS), iv) clinical T stage, v) subsite, and vi) Ku70 and the output variable was the local recurrence. Sensitivity and specificity were calculated by setting the threshold of the ANN output value to 0.5. The discriminatory power of the models was also analyzed using the area under the ROC curves (AUC). ANN analysis was performed using MATLAB (R2016a) software (Mathworks, Natick, MA, USA).

Figure 1. The architecture of the ANN model used for predictions of PSA relapse in prostate cancer and locoregional recurrence in hypopharyngeal cancer.

Results

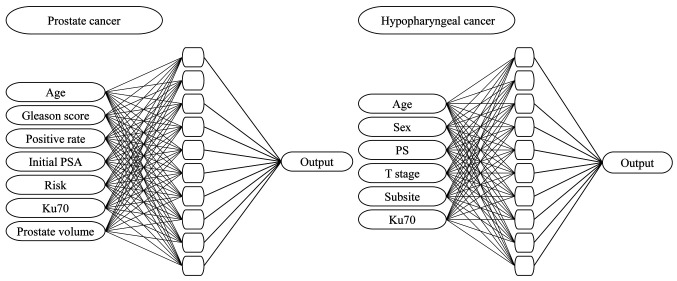

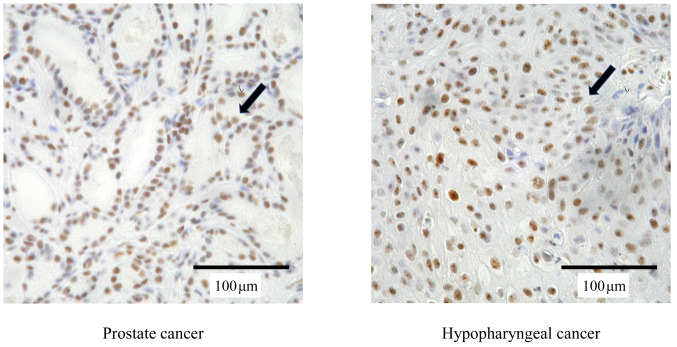

Tumor cells showed nuclear staining for Ku70 (Figure 2), while neither normal epithelial cells nor malignant cells exhibited cytoplasmic or membrane immunoreactivity in the biopsy specimens. The median percentage of tumor cell nuclei with positive staining for Ku70 was 66.4% (range=0-100%) in prostate cancer and 50.7% (range=0-98.3%) in hypopharyngeal cancer.

Figure 2. Expression of Ku70 protein (brown; arrows) in prostate and hypopharyngeal cancer cells from biopsy specimens. Original magnification was ×400.

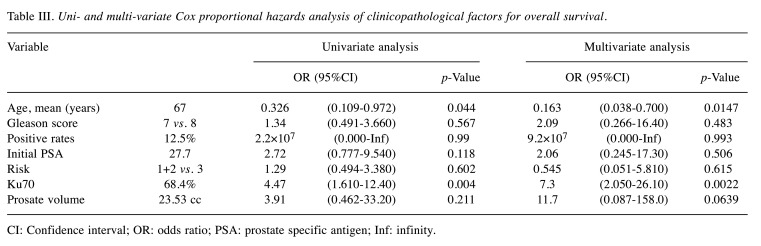

Table III shows the coefficients for PSA relapse in the discovery cohort using the MLR model. Age and Ku70 expression were significantly associated with PSA relapse in the univariate (p<0.05) as well as the multivariate analysis (p<0.05).

Table III. Uni- and multi-variate Cox proportional hazards analysis of clinicopathological factors for overall survival.

CI: Confidence interval; OR: odds ratio; PSA: prostate specific antigen; Inf: infinity.

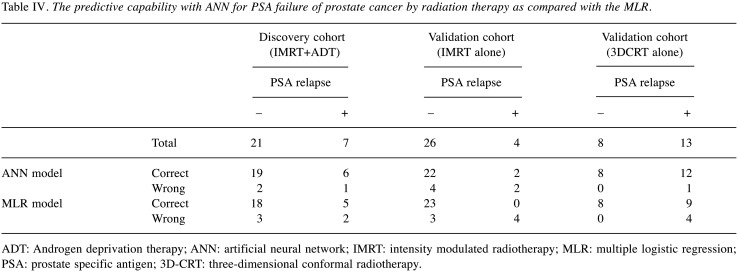

Table IV demonstrates the predictive capability with ANN for local control of prostate cancer by radiation therapy in the discovery and in the two sets of validations, as compared to the MLR. In the discovery cohort (IMRT+ADT), a correct prediction was possible in 19 of 21 patients without a PSA relapse, and 6 of 7 with a PSA relapse. Although the results of the prediction using the ANN model were almost similar as MLR in the discovery cohort, much less false negative rates were obtained using ANN in validation cohorts compared to MLR.

Table IV. The predictive capability with ANN for PSA failure of prostate cancer by radiation therapy as compared with the MLR.

ADT: Androgen deprivation therapy; ANN: artificial neural network; IMRT: intensity modulated radiotherapy; MLR: multiple logistic regression; PSA: prostate specific antigen; 3D-CRT: three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy.

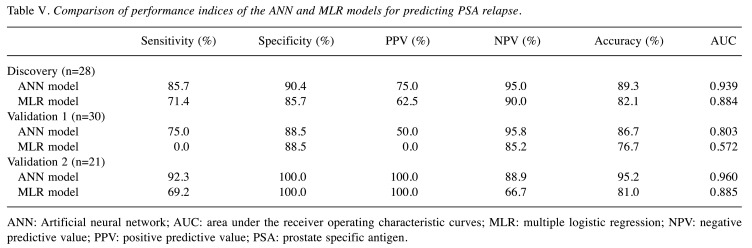

In order to validate these results, the ANN constructed using the discovery cohort (IMRT+ADT) was applied to two cohorts of patients with different treatments, such as IMRT without ADT or 3D-CRT without ADT (Table V). In these validation test stages for the ANN, the same prognostic factors were used as an input to the ANN trained using the discovery cohort, and then the ANN calculated the output according to the same weighting factors in the network as in the discovery cohort. In a validation cohort (IMRT without ADT), PSA recurrence-free was correctly predicted, in 22 of 26 PSA-free cases. PSA recurrence was predictable in two of four patients. When Ku70 expression was excluded from the input units and only the six clinical factors were used for the ANN analysis, the false positive increased. This meant that 8 of 26 patients without a PSA relapse were calculated as a PSA relapse. In the MLR model, the prediction of patients without relapse was similar to the one by ANN. However, none of the PSA relapsed patients were predictable. In another validation cohort (3DCRT without ADT), all 8 patients without PSA relapse as well as 12 of 13 with PSA relapse were predicted correctly. When Ku70 expression was excluded from the input units and only the six clinical factors were used for the ANN analysis, a correct prediction was possible with all 8 patients without a PSA relapse. In this analysis, however, the rate of the false negative increased, and 5 of 13 patients with a PSA relapse were calculated as no PSA relapse. In the MLR model, the prediction of patients without a relapse was similar to ANN, however, the number of false positives increased and 4 of 13 patients with a PSA relapse were calculated as no PSA relapse. The prognostic potency of ANN regarding two cohorts of validation is reasonably good and proves the appropriate choice and shape of the network proposed. Comparisons of performance indices in the discovery and validation cohorts showed that the ANN model tended to outperform the MLR (Table V). The values of AUC in ANN were better than MLR in all cohorts, although the differences were not significant due to the small numbers of patients.

Table V. Comparison of performance indices of the ANN and MLR models for predicting PSA relapse.

ANN: Artificial neural network; AUC: area under the receiver operating characteristic curves; MLR: multiple logistic regression; NPV: negative predictive value; PPV: positive predictive value; PSA: prostate specific antigen.

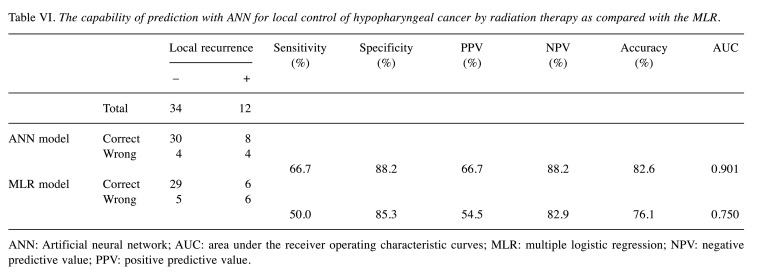

We then trained the ANN and tested its ability to predict local recurrence using the five clinical factors as well as the Ku70 expression in the hypopharyngeal cancer patients. For this purpose, we constructed an ANN with input units of the six prognostic factors, ten hidden units, and one output unit corresponding to the predicted value of local recurrence rate (Figure 2). Chemotherapy was not added to the input factor because the type and number of courses of chemotherapy were different. Compared to MLR, the capability of prediction of the ANN for local recurrence of hypopharyngeal cancer following radiation therapy is shown in Table VI. A correct prediction was possible by ANN in 30 of 34 patients without local recurrence, and in 8 of 12 patients with local recurrence. The irradiation doses were not used as an input factor of ANN or following analysis since similar total doses were used.

Table VI. The capability of prediction with ANN for local control of hypopharyngeal cancer by radiation therapy as compared with the MLR.

ANN: Artificial neural network; AUC: area under the receiver operating characteristic curves; MLR: multiple logistic regression; NPV: negative predictive value; PPV: positive predictive value.

When the MLR model was used, there were more false negatives compared to ANN. Comparisons of performance indices showed that the ANN model tended to outperform the MLR. The values of AUC in ANN were better than MLR although the differences were not significant due to the small number of patients.

Discussion

The purpose of this study is to develop a clinically useful method for predicting radiation therapy treatment results by combining immunohistochemical staining of the biopsy specimen with ANN analysis, which can be easily performed at any hospital.

The repair of various types of DNA damage is critical for cell survival. Of these, the DNA double-strand break (DSB) is one of the most serious forms of damage induced by DNA-damaging agents, such as ionizing irradiation (16). NHEJ is a key mechanism of DNA DSB repair (17), divided into three steps: i) detection, ii) processing and iii) ligation of DSB ends. In the detection step, Ku protein, a heterodimer consisting of Ku70 and Ku86, first binds to the ends of double-stranded DNA and then recruits the DNA-PK catalytic subunit (DNA-PKcs). The complex consisting of Ku70, Ku86 and DNA-PKcs is termed DNA dependent protein kinase (DNA-PK). Upon binding of DNA-PKcs to DNA ends, it exerts its kinase catalytic activity to phosphorylate substrate proteins. Thus, DNA-PK is considered the molecular sensor of DSB, triggering the signaling cascade. At the final ligation step, the DNA ligase IV in a tight association with the DNA repair protein XRCC4 catalyzes the reaction to join the two DNA ends together (18). Thus, Ku70 is a core component of NHEJ. Therefore, the immunohistochemical analysis of proteins involved in NHEJ may have a potential as a predictive assay for clinical tumor radiosensitivity. We have recently reported that the expression of proteins, such as Ku70 and XRCC4, in biopsy specimens could be a predictive marker of recurrence following radiotherapy, independently of the classic clinical prognostic markers (5,12,19,20).

The ANN model has been increasingly used in clinical research, especially for prognosis prediction (21-23) far more superior compared to the MLR and Cox models (15). The present study used the ANN model to predict radiotherapy treatment results for prostate cancer and the accuracy of the analysis by ANN was compared to MLR. The prediction of PSA relapse of prostate cancer following radiotherapy using the ANN model was more accurate compared to the prediction using the MLR models. Our results demonstrated the advantages and preferred characteristics of the ANN model over MLR.

In the treatment of prostate cancer, it is already known that the difference in radiation doses and the presence or absence of ADT affect the recurrence of PSA. Therefore, treatment was classified into three cohorts of discovery (IMRT+ADT) and two of validation (IMRT without ADT and 3D-CRT without ADT). Our method could differentiate between patients in the discovery group as with or without PSA relapse with an accuracy of 89.3%. Similar results were obtained in the two cohorts of validation. In the ROC analysis, the AUC value of the ANN model was 0.939 in IMRT+ADT (discovery cohort), 0.803 in IMRT without ADT (validation cohort), and 0.960 in 3D-CRT without ADT (validation cohort), suggesting that our method for prediction may be at a clinically usable level for prostate cancer. To investigate whether our method can be applied to other types of cancer we also applied it to predict the therapeutic effect of hypopharyngeal cancer. The AUC value of the ANN model was 0.901, showing that our method for prediction may also be at a clinically usable level for hypopharyngeal cancer.

The fact that our prediction method is effective for different types of cancers, such as prostate and hypopharyngeal cancer, might indicate the versatility of our prediction method. Results of radiotherapy for prostate cancer and hypopharyngeal cancer could be predicted using ANN by simply adding the immunohistochemical staining of Ku70 with the clinical factors used in ordinary clinical practice into inputs. This method is inexpensive and applicable to any hospital since the ANN software is already on the market and is not expensive. However, several limitations are present in this study. The number of patients is small, and some patients were treated with IMRT without image-guidance. We are planning to conduct a study to confirm our results using a larger cohort of patients treated with uniform therapy, such as image-guided IMRT.

In conclusion, we demonstrated a possibility to predict radiotherapy treatment results in prostate and hypopharyngeal cancer with ANN by using Ku70 expression and clinical factors as inputs. This model could be clinically useful since it is inexpensive and applicable to any hospital.

Conflicts of Interest

The Authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Authors’ Contributions

TH and MS participated in the data collection and interpretation, performed the analysis and participated in the drafting and final revising of the manuscript. MH, TT and YF participated in the patient care, data collection and interpretation. YM participated importantly in the conception of the study and helped to draft the manuscript. KS participated importantly in the conception and design and helped to draft the manuscript. All Authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Wouters BG, Begg AC. Irradiation-induced damage and the DNA damage response. In: Basic clinical radiobiology. 4th ed. Joiner MC, van der Kogeleds A (eds) London: Edward Arnold. 2009;London:pp 11–27. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kerns SL, Dorling L, Fachal L, Bentzen S, Pharoah PDP, Barnes DR, Gómez-Caamaño A, Carballo AM, Dearnaley DP, Peleteiro P, Gulliford SL, Hall E, Michailidou K, Carracedo A, Sia M, Stock R, Stone NN, Sydes MR, Tyrer JP, Ahmed S, Parliament M, Ostrer H, Rosenstein BS, Vega A, Burnet NG, Dunning AM, Barnett GC, West CML, Radiogenomics Consortium Meta-analysis of genome wide association studies identifies genetic markers of late toxicity following radiotherapy for prostate cancer. EBioMedicine. 2016;10(C):150–163. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Someya M, Yamamoto H, Nojima M, Hori M, Tateoka K, Nakata K, Takagi M, Saito M, Hirokawa N, Tokino T, Sakata KI. Relation between Ku80 and microRNA-99a expression and late rectal bleeding after radiotherapy for prostate cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2015;115:235–239. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2015.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pannunzio NR, Watanabe G, Lieber MR. Nonhomologous DNA end-joining for repair of DNA double-strand breaks. J Biol Chem. 2018;293:10512–10523. doi: 10.1074/jbc.TM117.000374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hasegawa T, Someya M, Hori M, Matsumoto Y, Nakata K, Nojima M, Kitagawa M, Tsuchiya T, Masumori N, Hasegawa T, Sakata KI. Expression of Ku70 predicts results of radiotherapy in prostate cancer. Strahlenther Onkol. 2017;193:29–37. doi: 10.1007/s00066-016-1023-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.D’Amico AV, Whittington R, Malkowicz SB, Schultz D, Blank K, Broderick GA, Tomaszewski JE, Renshaw AA, Kaplan I, Beard CJ, Wein A. Biochemical outcome after radical prostatectomy, external beam radiation therapy, or interstitial radiation therapy for clinically localized prostate cancer. JAMA. 1998;280(11):969–974. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.11.969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nikolaus K, Tal G. Neural network models and deep learning. Curr Biol. 2019;29(7):R231–R236. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2019.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Filippo A, Alberto L, Eladia M, Petr V, Ales H, Josef H. Artificial neural networks in medical diagnosis. J Appl Biomed. 2013;11:47–58. doi: 10.2478/v10136-012-0031-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, Fritz AG, Greene FL, Trotti A, editors. New York, NY:Springer. 2010. AJCC cancer staging manual (7th ed) [Google Scholar]

- 10.Someya M, Hori M, Tateoka K, Nakata K, Takagi M, Saito M, Hirokawa M, Hareyama M, Sakata KI. Results and DVH analysis of late rectal bleeding in patients treated with 3D-CRT or IMRT for localized prostate cancer. J Radiat Res. 2015;5:122–127. doi: 10.1093/jrr/rru080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.NCCN National Comprehensive Cancer. Available at:http://www.nccn.org [Last accessed on 1st April 2017]

- 12.Hayashi J, Sakata KI, Someya M, Matsumoto Y, Satoh M, Nakata K, Hori M, Takagi M, Kondoh A, Himi T, Hareyama M. Analysis and results of Ku and XRCC4 expression in hypopharyngeal cancer tissues treated with chemoradiotherapy. Oncol Lett. 2012;4:151–155. doi: 10.3892/ol.2012.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sakata K, Matsumoto Y, Tauchi H, Satho M, Oouchi A, Nagakura H, Koito K, Hosoi Y, Suzuki N, Komatsu K, Hareyama M. Expression of genes involved in repair of DNA double-strand breaks in normal and tumor tissues. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001;49:161–167. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(00)01352-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rumelhart DE, Hinton GE, Williams RJ. Cambridge, MIT Press. 1986. Learning internal representations by error propagation. In: Rumelhart DE, McCleland JL (eds). Parallel distributed processing: explorations in the microstructure of cognition. pp. 318–362. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sandberg IW, Lo JT, Fancourt CL, Principe JC, Katagiri S, Haykin S, editors. New York, Wiley. 2001. Nonlinear dynamical systems: feedforward neural network perspectives. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hall EJ. Philadelphia, Lippincott Williams < Wilkins. 2006. DNA strand breaks and chromosomal aberrations. In: Radiobiology for the Radiologist. Hall EJ and Giaccia AM (eds). 6th edition. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Polo SE, Jackson SP. Dynamics of DNA damage response proteins at DNA breaks: a focus on protein modification. Genes Dev. 2011;25(5):409–433. doi: 10.1101/gad.2021311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hall EJ. Philadelphia, Lippincott Williams < Wilkins. 2012. Molecular mechanisms of DNA and chromosome damage and repair. In: Radiobiology for the Radiologist. Hall EJ, Giaccia AJ (eds). 7th ed; pp. 12–21. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hori M, Someya M, Matsumoto Y, Nakata K, Kitagawa M, Hasegawa T, Tsuchiya T, Fukushima Y, Gocho T, Sato Y, Ohnuma H, Kato J, Sugita S, Hasegawa T, Sakata KI. Influence of XRCC4 expression in esophageal cancer cells on the response to radiotherapy. Med Mol Morphol. 2017;50(1):25–33. doi: 10.1007/s00795-016-0144-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takada Y, Someya M, Matsumoto Y, Satho M, Nakata K, Hori M, Saito M, Hirokawa N, Tateoka K, Teramoto M, Saito T, Hasegawa T, Sakata KI. Influence of Ku86 and XRCC4 expression in uterine cervical cancer on the response to preoperative radiotherapy. Med Mol Morphol. 2016;49(4):210–216. doi: 10.1007/s00795-016-0136-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang SH, Loh JK, Tsai JT, Houg MF, Shi HY. Predictive model for 5-year mortality after breast cancer surgery in Taiwan residents. Chin J Cancer. 2017;36:23–31. doi: 10.1186/s40880-017-0192-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bucinski A, Baczek T, Krysinski J, Szoszkiewicz R, Zaluski J. Clinical data analysis using artificial neural networks (ANN) and principal component analysis (PCA) of patients with breast cancer after mastectomy. Rep Pract Oncol Radiother. 2007;12(1):9–17. doi: 10.1016/S1507-1367(10)60036-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kathrine R, Manish K, Therese S, Anne HR, Dag RO. Early prediction of response to radiotherapy and androgen-deprivation therapy in prostate cancer by repeated functional MRI: a preclinical study. Radiat Oncol. 2011;6:65. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-6-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]