Abstract

Objectives:

To determine associations between 18–22 month (early) hand function and scores on the Movement Assessment Battery for Children, 2nd edition (MABC) at 6–7 years of age (school-age) in extremely preterm children.

Study design:

Prospective multi-center cohort of 313 extremely preterm children with early hand function assessment and school-age MABC testing. Early hand function was compared with ‘definite deficits’ (MABC <5th percentile) and MABC standard scores. Early hand function was categorized as ‘no deficit’ versus ‘any deficit’. Mixed effect regression models evaluated the association of early hand function with MABC deficits, controlling for multiple demographic, neonatal, and childhood factors.

Results:

Children with early hand function deficits were more likely to have definite school-age deficits in all MABC subtests (Manual Dexterity, Aiming and Catching, and Balance) and to have received physical or occupational therapy (45% vs 26% P < .001). Children with early hand function deficits had lower Manual Dexterity (p=0.006), Balance (p=0.035) and Total Test scores (p=0.039). Controlling for confounders, children with early hand function deficits had higher odds of definite school-age deficits in Manual Dexterity (aOR (95% CI):2.78 (1.36, 5.68), p=0.005) and lower Manual Dexterity (p=0.031) and Balance (p=0.027) scores. When excluding children with cerebral palsy and intelligence quotients<70, hand function deficits remained significantly associated with manual dexterity.

Conclusion:

Hand function deficits at 18–22 months are associated with manual dexterity deficits and motor difficulties at school-age, independent of perinatal-neonatal factors and the use of occupational or physical therapy. This has significant implications for school success, intervention and rehabilitative therapy development.

Keywords: Extremely preterm, fine motor, hand function

Children born extremely preterm (<28 weeks of gestation) are at high risk of significant motor deficits including cerebral palsy (CP). However; milder motor impairments such as fine motor deficits are nearly 3 times more common than CP (1). Fine motor function, or ‘hand function’, comprises the control and coordination of the musculature of the hands and fingers (2). During early childhood, accurate, coordinated movement of the muscles of the fingers and hands is critical for environmental exploration and learning.

At school-age, fine motor deficits may affect daily functioning and school success (1). Successful participation in the majority of kindergarten activities requires fine motor proficiency (3). In typically developing children at school-age and adulthood, early fine motor function has been associated with higher order executive functioning skills, such as planning and working memory (2, 4, 5). Connectivity between motor areas and other processing centers of the brain is essential for typical development of language (6, 7). Early fine motor skills require engagement from primary and secondary motor brain networks, and are strong predictors of school readiness (5–8). Despite the importance of fine motor function for future successes, studies of outcomes in extremely preterm children often assess only global motor function in early life, overlooking the impact of milder motor impairments or fine motor function.

Though fine motor functioning has been associated with neurodevelopment and school performance in typically developing children, the association between early hand function and school-age outcomes is not well understood in children born extremely preterm. Should toddler-age hand function be predictive of school-age manual dexterity, it could present an opportunity for targeted and evidence-based early intervention. We therefore sought to determine associations between early hand function at 18–22 months and scores on the Movement Assessment Battery for Children, 2nd edition (MABC) at early school age (6–7 years) in children born extremely preterm. We hypothesized that early hand function would be positively associated with later performance on the Manual Dexterity subtest of the MABC assessment, and that hand function at 18–22 months would also be associated with MABC Total Test scores and with scores on the Aiming and Catching and Balance subtests of the MABC at school age.

Methods

This was a prospective, observational cohort study of children enrolled in the SUPPORT Neuroimaging and Neurodevelopmental Outcomes (NEURO) Study of extremely preterm infants born at <28 weeks of gestation. The SUPPORT NEURO study was a secondary to the SUPPORT study (9) and included neonatal neuroimaging as well as 18–22 month and 6–7 year neurodevelopmental assessments (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT00063063 and NCT0000) (10, 11). Children were eligible for inclusion in this study if they were enrolled in the SUPPORT NEURO study, had complete hand function assessments on the 18–22 month neuromotor examination, and completed the Manual Dexterity subtest of the MABC at the 6–7-year visit. The NEURO study enrolled children from 5/2005 to 2/2009 at 15 NRN centers nationwide. Informed consent was obtained for study participants, and the study was approved by the institutional review boards of all participating centers, and by the institutional review board of RTI International, the Data Coordinating Center for the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Development Neonatal Research Network (NICHD NRN).

Measures

Early Hand Function.

Pincer and grasp capacity, exaggerated hand preference, and ability to perform bimanual functions were assessed in detail at 18–22 months of corrected age using the ‘hand function’, ‘upper limb function’, and ‘hand preference’ subsections of the standardized NRN neuromotor examination (1). Clinicians trained and certified annually in this assessment perform this examination. The child is sitting comfortably with hands free during these portions of the examination. Pincer and grasp capacity are assessed in the ‘hand function’ subsection of the examination. This requires presenting a Cheerio to the child at waist-level on a flat, firm surface that is of contrasting color with the Cheerio. The hand function items are coded as 1) fine pincer grasp, 2) finger-thumb grasp, 3) more than one finger-thumb (rake) grasp and 4) tries but unable to grasp. Ability to perform bimanual functions is determined in the ‘upper limb function’ subsection. This is coded as: 1) No apparent problem with bimanual tasks (the child is able to manipulate small toys and small objects with both hands and transfer from one hand to the other with both hands in midline position); 2) Some difficulty using both hands together (the child is able to perform the task with a typical variation but with limitation and difficulty in the midline position on bimanual transfer); and 3) No functional bimanual task. Hand preference is coded as: 1) no preference; 2) exaggerated right; 3) exaggerated left. This is determined by the child’s method of obtaining an offered object. If a child presented an object on his or her right side consistently reaches across midline to grab it with the left hand, this is considered “exaggerated left”. An “exaggerated right” is when a child presented an object on the left side consistently reaches across midline to grab it with the right hand.

Three possible levels of hand function were attributed based on the assessments: normal, mild deficit and severe deficit. Normal (‘no deficit’) in hand function was defined as 1) fine pincer or finger thumb grasp, 2) no hand preference, and 3) no apparent problem with bimanual tasks. Mild deficit was defined as 1) more than one finger-thumb (rake) grasp, 2) any hand preference, and 3) some difficulty using both hands together. Severe deficit was defined as 1) tries but unable to grasp, 2) any hand preference, and 3) no functional bimanual task. As only 7 children had severe hand deficits, these children were combined with those with mild deficits, leaving 2 hand function categories utilized for analysis — 1) ‘no deficit’ versus 2) ‘any deficit’. ‘Any deficit’ in hand function was defined as any of the following: 1) any hand preference, 2) rake grasp, 3) some difficulty with using both hands together, 4) tries but unable to grasp, or 5) no ability to perform functional bimanual tasks. Where different values were found for the right versus the left hand, the worst score was assigned. NRN examiners assessing hand function were masked to hospital morbidities. The Motor scale of the Bayley Scales of Infant-Toddler Development, 3rd Edition was not part of the 18–22 month NRN assessment until after 2010, and was not available for the children included in this study (1).

Movement Assessment battery for Children-II (MABC).

The MABC is a widely used motor assessment tool utilized for the identification and characterization of motor and coordination impairments in children ages 3–17 years (12, 13). The youngest age band of the MABC was administered (3 years 0 months to 6 years 11 months) at the same time as a neurological examination that was performed by a physician or other clinician who was trained and certified in the assessment. The MABC evaluates 3 scales – Manual Dexterity, Aiming and Catching, and Balance. Scaled MABC scores are obtained as well as percentiles. Scores ≤5th percentile demonstrate a significant movement difficulty (‘definite deficit’); scores from the 6–15th percentile indicate ‘at risk’; and ≥16th percentile are unlikely to have a movement difficulty (‘no deficit’).

Statistical Analyses.

We determined a priori that with the available sample size there was 90% power to detect medium-sized differences (d=0.5) in mean MABC scale scores between the two hand function groups. Medical and psychosocial variables previously shown to adversely affect neurodevelopmental outcomes in at-risk children (14–20) were compared based on Manual Dexterity deficit category (none, at-risk, and definite) in bivariate analyses using chi-square tests (Table 1). Then, we compared performance on the MABC at school-age for children with versus without hand function deficits at 18–22 months of corrected age. Frequencies, percentages, and chi-square tests were computed for categorical variables and means, standard deviations, and t-tests for continuous variables.

Table 1.

Percentage of Children with Manual Dexterity Deficits at School Age by Demographic, Perinatal and Neonatal Characteristics and Gross Motor Function

| Variable | N | Manual Dexterity Deficit* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Definite N (Row %) | At-risk N (Row %) | None N (Row %) | p-value | ||

| Demographic/Perinatal/Neonatal | |||||

| Birth weight | |||||

| < 840 | 148 | 59 (40) | 25 (17) | 64 (43) | 0.255 |

| 840+ | 162 | 51 (31) | 27 (17) | 84 (52) | |

| Gestational age | |||||

| < 26 weeks | 109 | 50 (46) | 21 (19) | 38 (35) | 0.003 |

| 26+ weeks | 201 | 60 (30) | 31 (15) | 110 (55) | |

| Multiple gestation | |||||

| Yes | 72 | 20 (28) | 17 (24) | 35 (49) | 0.123 |

| No | 238 | 90 (38) | 35 (15) | 113 (47) | |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||

| Non-Hispanic black | 106 | 42 (40) | 16 (15) | 48 (45) | 0.318 |

| Non-Hispanic white | 127 | 45 (35) | 17 (13) | 65 (51) | |

| Hispanic | 69 | 21 (30) | 18 (26) | 30 (43) | |

| Other | 8 | 2 (25) | 1 (13) | 5 (63) | |

| Non-Hispanic white | |||||

| Yes | 193 | 45 (35) | 17 (13) | 65 (51) | 0.367 |

| No | 117 | 65 (36) | 35 (19) | 83 (45) | |

| Maternal education | |||||

| < HS | 79 | 30 (38) | 13 (16) | 36 (46) | 0.829 |

| HS or more | 225 | 77 (34) | 38 (17) | 110 (49) | |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 167 | 67 (40) | 34 (20) | 66 (40) | 0.006 |

| Female | 143 | 43 (30) | 18 (13) | 82 (57) | |

| Any antenatal steroids | |||||

| Yes | 296 | 100 (34) | 50 (17) | 146 (49) | 0.012 |

| No | 14 | 10 (71) | 2 (14) | 2 (14) | |

| Cesarean delivery | |||||

| Yes | 205 | 75 (37) | 39 (19) | 91 (44) | 0.178 |

| No | 105 | 35 (33) | 13 (12) | 57 (54) | |

| PDA diagnosed | |||||

| Yes | 155 | 63 (41) | 28 (18) | 64 (41) | 0.069 |

| No | 155 | 47 (30) | 24 (15) | 84 (54) | |

| Early sepsis | |||||

| Yes | 9 | 4 (44) | 0 (0) | 5 (56) | 0.390 |

| No | 301 | 106 (35) | 52 (17) | 143 (48) | |

| Late sepsis | |||||

| Yes | 94 | 38 (40) | 15 (16) | 41 (44) | 0.481 |

| No | 216 | 72 (33) | 37 (17) | 107 (50) | |

| NEC | |||||

| Yes | 20 | 6 (30) | 0 (0) | 14 (70) | 0.050 |

| No | 290 | 104 (36) | 52 (18) | 134 (46) | |

| Severe ROP | |||||

| Yes | 30 | 14 (47) | 5 (17) | 11 (37) | 0.286 |

| No | 258 | 85 (33) | 43 (17) | 130 (50) | |

| Surgery for PDA, NEC, or ROP | |||||

| Yes | 55 | 24 (44) | 5 (9) | 26 (47) | 0.165 |

| No | 255 | 86 (34) | 47 (18) | 122 (48) | |

| Postnatal steroids | |||||

| Yes | 20 | 9 (45) | 2 (10) | 9 (45) | 0.540 |

| No | 287 | 99 (34) | 50 (17) | 138 (48) | |

| BPD | |||||

| Yes | 115 | 47 (41) | 16 (14) | 52 (45) | 0.268 |

| No | 195 | 63 (32) | 36 (18) | 96 (49) | |

| Physical Therapy (received or receiving) | |||||

| Yes | 149 | 61 (41) | 24 (16) | 64 (43) | 0.158 |

| No | 160 | 49 (31) | 28 (18) | 83 (52) | |

| Occupational Therapy (received or receiving) | |||||

| Yes | 157 | 71 (45) | 26 (17) | 60 (38) | < 0.001 |

| No | 152 | 39 (26) | 26 (17) | 87 (57) | |

| Gross Motor Function | |||||

| Any CP | |||||

| Yes | 7 | 4 (57) | 1 (14) | 2 (29) | 0.467 |

| No | 303 | 106 (35) | 51 (17) | 146 (48) | |

| Moderate/severe CP | |||||

| Yes | 1 | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.402 |

| No | 309 | 109 (35) | 52 (17) | 148 (48) | |

| GMFCS level 2 or higher | |||||

| Yes | 4 | 2 (50) | 1 (25) | 1 (25) | 0.656 |

| No | 306 | 108 (35) | 51 (17) | 147 (48) | |

Categories correspond to <5th Percentile (Definite deficit); 5th-15th Percentile (At-risk), >15th (No deficit)

Medical and psychosocial variables were selected for inclusion as control variables in the regression models if they differed significantly at p < 0.1 for Manual Dexterity deficit in bivariate comparisons. Finally, linear mixed effect regression models compared scores on the MABC tests based on hand function deficit, after controlling for demographic and medical characteristics and including NRN center as a random effect. A similar generalized linear mixed effect model compared definite (vs. none/at-risk) deficits in Manual Dexterity by early hand function deficit while controlling for other factors.

Results

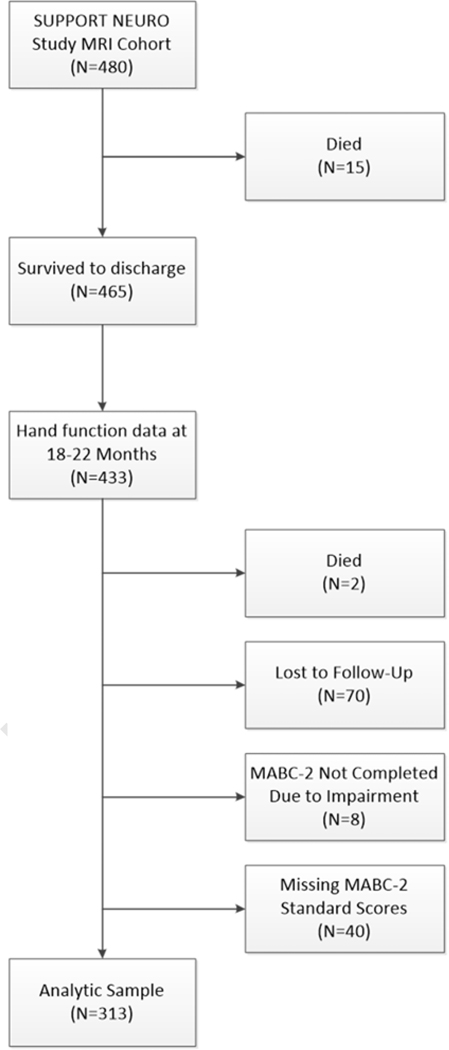

A total of 313 children were included in the study sample. Figure 1 (available at www.jpeds.com) details the study sample selection process. We compared the demographic and neonatal characteristics (Table I) for the 313 children in the analysis with the 110 who were excluded due to loss-to-follow-up or missing MABC standard scores. Those who were excluded from the analyses were more likely to have received postnatal steroids (13% vs. 7%, p=0.049), otherwise there were no significant differences between the groups. There was no difference in rates of early hand function deficits between the children who were included and those who were lost to follow-up or missing MABC scores (13% vs. 18%, respectively, p=0.224).

School-age motor performance.

Overall, 35% of children had definite deficits on the MABC Manual Dexterity subtest, 10% had definite deficits in Balance, 6% had definite deficits in Aiming and Catching, and 17% had total MABC test scores in the ‘definite deficit’ range. Table 1 presents the unadjusted comparison of demographic and medical characteristics based on deficits on the MABC Manual Dexterity subscale at school-age. Children who were born at <26 weeks were significantly more likely to have definite Manual Dexterity deficits at school-age than those born at 26–28 weeks (p=0.003). Boys were more likely to have school-age Manual Dexterity deficits than girls (p=0.006), and children who received physical and/or occupational therapy (PT/OT) at 18–22 months were more likely to have Manual Dexterity deficits at school-age (p<0.001). Children who received antenatal steroids were less likely to have definite Manual Dexterity deficits at school-age (p=0.012). There was no increase in Manual Dexterity deficits based on race/ethnicity.

School-age motor function and early hand function.

The percentage of children in each hand function group at 18–22 months who had MABC deficits at 6–7 years is shown in Table 2. Children with early hand function deficits were significantly more likely to have definite deficits (scores <5th percentile) in total MABC scores and in all MABC subtests at school-age than those without early hand function deficits. Children with early hand function deficits also had lower mean Manual Dexterity, Balance, and Total Test scores (p=0.006, p=0.035, and p=0.039, respectively; Table 2). Mean scores on the Aiming and Catching subscale were not significantly different based on early hand function.

Table 2.

Percentage of Children with Hand Function Deficits at 18–22 Months by MABC Findings at school-age

| Variable | Hand Function Deficit | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| No deficit | Any deficit | p-value | |

| MABC-2 Categories | n/N (Col %) | n/N (Col %) | |

| Manual Dexterity | |||

| <5th Centile (Definite Deficit) | 87/269 (32) | 23/41 (56) | 0.012 |

| 6th-15th Centile (At-Risk) | 47/269 (17) | 5/41 (12) | |

| >15th Centile (No Deficit) | 135/269 (50) | 13/41 (32) | |

| Aiming and Catching | |||

| <5th Centile (Definite Deficit) | 12/270 (4) | 7/42 (17) | 0.007 |

| 6th-15th Centile (At-Risk) | 31/270 (11) | 3/42 (7) | |

| >15th Centile (No Deficit) | 227/270 (84) | 32/42 (76) | |

| Balance | |||

| <5th Centile (Definite Deficit) | 21/266 (8) | 9/42 (21) | 0.021 |

| 6th−15th Centile (At-Risk) | 45/266 (17) | 7/42 (17) | |

| >15th Centile (No Deficit) | 200/266 (75) | 26/42 (62) | |

| Total Test Score | |||

| <5th Centile (Definite Deficit) | 38/264 (14) | 14/41 (34) | 0.005 |

| 6th−15th Centile (At-Risk) | 63/264 (24) | 10/41 (24) | |

| >15th Centile (No Deficit) | 163/264 (62) | 17/41 (41) | |

| MABC-2 Scores | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | p-value |

| Manual Dexterity | 6.89 (3.43) | 5.27 (4.01) | 0.006 |

| Aiming and Catching | 9.55 (3.06) | 9.05 (4.47) | 0.358 |

| Balance | 8.53 (2.98) | 7.43 (4.03) | 0.035 |

| Total Test Score | 7.75 (3.23) | 6.56 (4.42) | 0.039 |

Regression models of school-age motor function by early hand function.

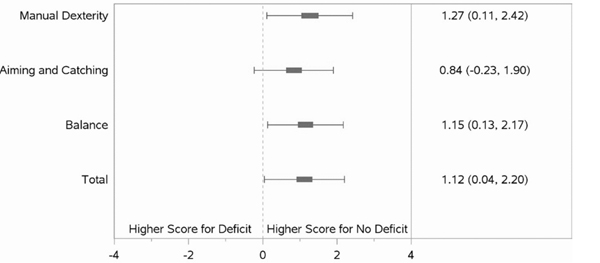

Results of regression models are shown in Figure 2 and Table 3. Each model controlled for variables that were significantly associated with school-age Manual Dexterity in bivariate analyses at p<0.1 (OT/PT receipt at 18–22 months, gestational age, male sex, receipt of antenatal steroids, NEC, and PDA). After controlling for these variables, children with hand function deficits at 18–22 months’ corrected age had nearly 3 times the odds of having a definite deficit (< 5th percentile) on the MABC Manual Dexterity subtest at 6–7 years (Table 3). Children who received OT/PT at 18–22 months had nearly twice the odds of having a school-age definite deficit in Manual Dexterity. Children with higher gestational ages (26–28 weeks versus those born <26 weeks) as well as those children who received antenatal steroids had lower odds of having a definite Manual Dexterity deficit at school-age. When mean MABC scores were considered (Figure 2), children with hand function deficits had significantly lower scores on the MABC Manual Dexterity (p=0.024) and Balance (p=0.020) subsets as well as Total Test (p=0.036) scores than those without deficits after controlling for other factors (Figure 2), but these groups did not differ on the Aiming and Catching subtest.

Figure 2.

Linear Regression Models of School-Age MABC-2 mean scores by Early Hand Function

Note: Coefficients are adjusted for site, received OT/PT at 18–22 months, gestational age, male, antenatal steroids, NEC, and PDA

Table 3.

Generalized Linear Regression Models of MABC-2 Manual Dexterity < 5th Percentile (vs. ≥5th Percentile) by 18–22-month Hand Function

| Variable | Adj. OR* (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Hand Function Deficit | 2.78 (1.36, 5.68) | 0.005 |

| Received OT/PT** | 1.93 (1.15, 3.24) | 0.013 |

| Gestational age | 0.76 (0.59, 0.97) | 0.030 |

| Male | 1.44 (0.87, 2.39) | 0.154 |

| Antenatal steroids | 0.16 (0.04, 0.57) | 0.005 |

| NEC | 0.68 (0.23, 2.00) | 0.481 |

| PDA | 1.25 (0.75, 2.08) | 0.400 |

Center is included as a random effect

Recorded at 18–22 month corrected age visit

Sensitivity Analyses.

We reran bivariate comparisons for the MABC subtests excluding the following groups, one at a time: (1) children with any level of CP, (2) children with moderate/severe CP, and (3) children with a full-scale intelligence quotient (IQ) < 70. After excluding these groups, hand function deficits at 18–22 months remained significantly associated with school-age Manual Dexterity scores only (Table 4; available at www.jpeds.com).

Discussion

In this longitudinal study of >300 extremely preterm infants followed from preschool to school-age, fine motor deficits at 18–22 months were significantly associated with manual dexterity deficits and poorer balance at school-age, independent of perinatal-neonatal factors and OT/PT receipt. In sensitivity analyses excluding children with CP and IQ<70, hand function deficits at 18–22 months remained significantly associated with school-age Manual Dexterity scores. We also found that exposure to antenatal steroids was associated with lower rates of manual dexterity deficits at school-age, which could be related to a number of confounders and intermediates influenced by steroid receipt. Other researchers have found rates of CP in extremely preterm children of 7 to 11% (21, 22). Our finding that only 2% of the current study’s cohort had CP at 6–7 years (considerably lower than the published prevalence rates for extremely preterm children) may indicate that children with CP were less likely to complete the MABC. Even within the context of fewer children with CP and potential severe impairments, 35% of our cohort still had fine motor (manual dexterity) deficits at school age. This finding thus supports published literature showing that milder motor impairments are significant contributors to functional impairment (23, 24). The foundations for the fine motor skills necessary for school success emerge in early infancy; and acquisition of these skills by school-age is critical, as up to two-thirds of daily kindergarten activities rely on fine motor skills (3). Fine motor execution is fundamental to the development of handwriting skills (25) and is strongly associated with numerical manipulation ability and executive function competencies such as processing speed and working memory (2, 26). We demonstrated that early hand function deficits at 18–22 months were associated with concurrent deficits in object permanence as a measure of early working memory in children born extremely preterm (1). Given that deficiencies in grapho-motor skills tend to cluster with deficits in attention and processing speed at school-age (27), the high rate of manual dexterity deficits in our cohort of extremely preterm children in early childhood and at school-age is especially concerning. Our study was not designed to determine whether children with manual dexterity deficits also had higher rates of attention deficit problems, a common problem in children born extremely preterm (28). Therefore, we are unable at this time to speculate on the influence of deficient attentional networks on dexterity findings.

The rate of hand function deficits in the cohort increased from 16% at 18–22 months to 35% at school age. The results of a meta-analysis of studies of motor development in children born preterm and very low birth weight from birth to adolescence suggested that the differences in motor function between the preterm and very low birth weight children and those born at term decrease in the first years of life, but increase later in development (25). This may represent an increase in fine motor deficits as extremely preterm children age, but is more likely a function of the increased complexity of manual dexterity demands in older age assessments such as the MABC.

The association other researchers have noted between early fine motor skill and higher order functioning likely relates to the interplay between cognitive and motor regions in the brain during development. In infancy, movements are initially reflexive; increased cognitive control and ability is required as more purposeful, complex movements are needed (29). Movement therefore drives cognition and higher order functioning through engagement of motor skills in problem-solving. The interconnection of motor and cognitive function is founded on the neural interconnections between brain regions previously thought to function primarily for cognition or movement, but not both. Fine motor function has also been demonstrated to mediate the visual memory and visual motor integration deficiencies seen in preterm children (30), and visual perceptive function is a factor underlying the IQ differences seen in preterm and term children (31). Fine motor function requires visual-motor coordination and visual spatial integration (29), and is a critical component of visual-motor integration (32). Our findings of increased manual dexterity deficits at school age may represent the inability of extremely preterm children to keep up with increasing manual dexterity demands as they age; this may be confounded by deficits in visual motor skills, though we are unable to determine this within the current study.

The impact of early fine motor ability on the development of later motor ability and higher order functioning in extremely preterm children is not well studied. The early neural insults sustained by extremely preterm infants may result in abnormalities in critical brain circuits responsible for the visual perceptual, motor coordination, and integration skills necessary for adequate fine motor function (29). These neural abnormalities, in turn, may lead to abnormal visual motor integration and may underlie not only the fine motor, balance and coordination deficits, but the abnormalities in many of the other neurodevelopmental domains associated with the poor school outcomes of many extremely preterm children. More likely, fine motor learning of advanced skills is driven by the brain’s Bayesian computations of new movement, based on prior probability (experience) of movement (33). Early deficits in hand function limit experience and decrease its quality, resulting in more faulty computations and poorer execution of movement, with the downstream effect of magnifying early fine motor deficits. Early hand functioning was longitudinally assessed with school age fine and gross motor function; however, the two measurement time points were remote. Causation cannot therefore be directly inferred between early hand function deficits and the school age motor performance. The more global perinatal neural insults of extremely preterm infants may drive both proximal and distal motor functioning. Conversely, early hand function deficits may cumulatively affect school age motor function via limitations in motor experiences as has been shown in adults (34). Either hypothesis could be supported from our study results, and future studies should longitudinally examine these connections with multiple time points and causal mediation analyses.

This study had several limitations. First, the MABC Manual Dexterity test focuses on the visual motor coordination element of fine motor function and not the visual spatial integration element (e.g., replicating an internally created representation of an image and creating it using the small muscles of the hand in an activity such as copying) (29). Also, though the early fine motor assessment was extracted from the standardized NRN neuromotor examination with highly monitored inter-rater reliability, the psychometric properties of this assessment have not been published. Although not feasible within the diverse NRN sites and resource constraints, the current study would have been bolstered by the inclusion of an early hand function assessment such as the Mini-Assisting Hand Assessment (35). In addition, 7% of the children who were included in the 18–22 month assessment had impairment at school age that precluded completion of the MABC. This could have biased the results of the study, as loss of these children could have resulted in an underestimation of school-age impairment. The lack of inclusion of 27% of the population studied at 18–22 months in the school age assessment could similarly have resulted in unknown bias in the results. Conversely, the study is strengthened by the large sample size despite the losses, and measures of both early and school-age fine motor function.

The effect of poor fine motor skill on adaptive functioning during early life cannot be overstated. Early dysfunction impairs a child’s ability to explore their environment, develop key communication skills (both non-verbal early on and written during school), and is associated with decreased motor function, cognition, executive functioning, behavioral issues and learning problems in older children (14). The association of school-age fine motor deficits with early hand function deficits may not only provide a more granular ability to predict which extremely preterm children are most likely to develop issues at school-age so as to allow for closer surveillance; this association may also indicate a target for earlier intervention (early hand function) that may allow clinicians to leverage early neuroplasticity to improve neurological connections in the first 2 years of life and enhance outcomes across neuropsychological domains. In the extremely preterm population even more than in term infants, fine motor skill characterization may be critical to rigorous intervention design to support early scholastic skills. Our finding that school-age manual dexterity and balance deficits remained despite receipt of PT/OT in the preschool years could be secondary to children with the poorest motor function being more likely to receive these therapies at the early age and also to have abnormalities at school age. This finding more likely points to the extreme heterogeneity in therapies delivered to the children resulting in no overall effect, as suggested by previous research (36). Evidence-based, standardized and targeted early interventions, however, improve outcomes (36–40) and are critically needed for this population.

In conclusion, longitudinal studies of fine motor development in extremely preterm infants offer an opportunity to characterize the trajectory of fine motor outcomes through school-age in extremely preterm children and identify early predictors of school-age outcomes. This study provides important longitudinal data to that end. Our findings may have significant implications for school success and more complex constructs such as later executive function. Further study is necessary to further elucidate the full phenotype of motor development in extremely preterm children so that interventions may be effectively designed and monitored for efficacy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank our medical and nursing colleagues and the infants and their parents who agreed to take part in this study.

The National Institutes of Health (M01 RR30, M01 RR32, M01 RR39, M01 RR54, M01 RR59, M01 RR64, M01 RR80, M01 RR70, M01 RR633, M01 RR750, M01 RR997, UL1 RR25008, UL1 RR25744, UL1 TR442), the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) (U10 HD21364, U10 HD21385, U10 HD21373, U10 HD27851, U10 HD27856, U10 HD27880, U10 HD27904, U10 HD34216, U10 HD36790, U10 HD40461, U10 HD40492, U10 HD40689, U10 HD53089, U10 HD53109, U10 HD53119, U10 HD53124), and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) (via co-funding) provided grant support for the Neonatal Research Network’s Extended Follow-up at School Age for the SUPPORT Neuroimaging and Neurodevelopmental Outcomes (NEURO) Cohort. The National Institutes of Health, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) provided grant support for the Neonatal Research Network’s Extended Follow-up at School Age for the SUPPORT Neuroimaging and Neurodevelopmental Outcomes (NEURO) Cohort through cooperative agreements. Recruitment for the 18–22 month follow-up took place from 2006–2011, and the 6–7 year follow-up took place from 2010–2016. While NICHD staff had input into the study design, conduct, analysis, and manuscript drafting, the comments and views of the authors do not necessarily represent the views of the NICHD.

Data collected at participating sites of the NICHD Neonatal Research Network (NRN) were transmitted to RTI International, the data coordinating center (DCC) for the network, which stored, managed and analyzed the data for this study. On behalf of the NRN, RTI International had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

Portions of this study were presented at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting, April 24-May 1, 2019, Baltimore, Maryland.

Abbreviations:

- CP

Cerebral palsy

- MABC

Movement Assessment Battery for Children, 2nd edition

- NICHD NRN

Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Development Neonatal Research Network

- NEURO

Neuroimaging and Neurodevelopmental Outcomes

- OT

Occupational therapy

- PT

Physical therapy

Appendix

Additional members of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Development Neonatal Research Network

NRN Steering Committee Chairs: Alan H. Jobe, MD PhD, University of Cincinnati (2003–2006); Michael S. Caplan, MD, University of Chicago, Pritzker School of Medicine (2006–2011); Richard A. Polin, MD, Division of Neonatology, College of Physicians and Surgeons, Columbia University, (2011-present).

Alpert Medical School of Brown University and Women & Infants Hospital of Rhode Island (U10 HD27904) – Abbot R. Laptook, MD; Betty R. Vohr, MD; Angelita M. Hensman, MS RNC-NIC; Elisa Vieira, RN BSN; Emilee Little, RN BSN; Katharine Johnson, MD; Barbara Alksninis, PNP; Mary Lenore Keszler, MD; Andrea M. Knoll; Theresa M. Leach, MEd CAES; Elisabeth C. McGowan, MD; Victoria E. Watson, MS CAS.

Case Western Reserve University, Rainbow Babies & Children’s Hospital (U10 HD21364, M01 RR80) – Michele C. Walsh, MD MS; Avroy A. Fanaroff, MD; Deanne E. Wilson-Costello, MD; H. Gerry Taylor, PhD; Maureen Hack, MD (deceased); Allison Payne, MD MSCR; Nancy S. Newman, RN; Bonnie S. Siner, RN; Arlene Zadell, RN; Julie DiFiore, BS; Monika Bhola, MD; Harriet G. Friedman, MA; Gulgun Yalcinkaya, MD.

Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, University of Cincinnati Medical Center, and Good Samaritan Hospital (UG1 HD27853) – Kimberly Yolton, PhD.

Department of Diagnostic Imaging and Radiology, Children’s National Medical Center, Washington DC – Dorothy Bulas, MD.

Duke University School of Medicine, University Hospital, and Duke Regional Hospital (U10 HD40492, M01 RR30) – Ronald N. Goldberg, MD; C. Michael Cotten, MD MHS; Kathryn E. Gustafson, PhD; Ricki F. Goldstein, MD; Patricia Ashley, MD; Kathy J. Auten, MSHS; Kimberley A. Fisher, PhD FNP-BC IBCLC; Katherine A. Foy, RN; Sharon F. Freedman, MD; Melody B. Lohmeyer, RN MSN; William F. Malcolm, MD; David K. Wallace, MD MPH.

Emory University, Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, Grady Memorial Hospital, and Emory Crawford Long Hospital (U10 HD27851, RR25008, M01 RR39) – David P. Carlton, MD; Barbara J. Stoll, MD; Susie Buchter, MD; Anthony J. Piazza, MD; Ira Adams-Chapman, MD; Sheena Carter, PhD; Sobha Fritz, PhD; Ellen C. Hale, RN BS CCRC; Amy K. Hutchinson, MD; Maureen Mulligan LaRossa, RN; Yvonne Loggins, RN, Diane Bottcher, RN.

Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development – Rosemary D. Higgins, MD; Stephanie Wilson Archer, MA.

Indiana University, University Hospital, Methodist Hospital, Riley Hospital for Children, and Wishard Health Services (U10 HD27856, M01 RR750) – Brenda B. Poindexter, MD MS; Gregory M. Sokol, MD; Lu-Ann Papile, MD; Heidi M. Harmon, MD MS; Abbey C. Hines, PsyD; Leslie D. Wilson, BSN CCRC; Dianne E. Herron, RN; Lucy Smiley, CCRC.

McGovern Medical School at The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston and Children’s Memorial Hermann Hospital (U10 HD21373) – Kathleen A. Kennedy, MD MPH; Jon E. Tyson, MD MPH; Allison G. Dempsey, PhD; Janice John, CPNP; Patrick M. Jones, MD MA; M. Layne Lillie, RN BSN; Saba Siddiki, MD; Daniel K. Sperry, RN.

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute – Mary Anne Berberich, PhD; Carol J. Blaisdell, MD; Dorothy B. Gail, PhD; James P. Kiley, PhD.

RTI International (U10 HD36790) – Abhik Das, PhD; Dennis Wallace, PhD; Marie G. Gantz, PhD; Jeanette O’Donnell Auman, BS; Jane A. Hammond, PhD; Jamie E. Newman, PhD MPH; W. Kenneth Poole, PhD (deceased).

Stanford University and Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital (U10 HD27880, UL1 RR25744, M01 RR70) – Krisa P. Van Meurs, MD; David K. Stevenson, MD; Maria Elena DeAnda, PhD; M. Bethany Ball, BS CCRC; Patrick D. Barnes, MD; Gabrielle T. Goodlin, BAS.

Tufts Medical Center, Floating Hospital for Children (U10 HD53119, M01 RR54) – Ivan D. Frantz III, MD; Elisabeth C. McGowan, MD; John M. Fiascone, MD; Anne Furey, MPH; Brenda L. MacKinnon, RNC; Ellen Nylen, RN BSN; Ana Brussa, MS OTR/L; Cecelia Sibley, PT MHA.

University of Alabama at Birmingham Health System and Children’s Hospital of Alabama (U10 HD34216, M01 RR32) – Waldemar A. Carlo, MD; Namasivayam Ambalavanan, MD; Monica V. Collins, RN BSN MaEd; Shirley S. Cosby, RN BSN; Vivien A. Phillips, RN BSN; Kristy Domanovich, PhD; Sally Whitley, MA OTR-L FAOTA; Leigh Ann Smith CRNP, Carin R. Kiser, MD.

University of California – San Diego Medical Center and Sharp Mary Birch Hospital for Women (U10 HD40461) – Neil N. Finer, MD; Donna Garey, MD MPH; Maynard R. Rasmussen; MD; Paul R. Wozniak, MD; Yvonne E. Vaucher, MD MPH; Martha G. Fuller, PhD RN; Natacha Akshoomoff, PhD; Wade Rich, BSHS RRT; Kathy Arnell, RNC; Renee Bridge, RN.

University of Iowa (U10 HD53109, UL1 TR442, M01 RR59) – Edward F. Bell, MD; Tarah T. Colaizy, MD; John A. Widness, MD; Jonathan M. Klein, MD; Karen J. Johnson, RN BSN; Michael J. Acarregui, MD; Diane L. Eastman, RN CPNP MA; Tammy L. V. Wilgenbusch, PhD.

University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center (U10 HD53089, M01 RR997) – Kristi L. Watterberg, MD; Robin K. Ohls, MD; Jean Lowe, PhD; Janell Fuller, MD; Julie Rohr, MSN RNC CNS; Conra Backstrom Lacy, RN; Rebecca Montman, BSN; Sandra Brown, RN BSN.

University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas, Parkland Health & Hospital System, and Children’s Medical Center Dallas (U10 HD40689, M01 RR633) – Myra Wyckoff, MD; Luc Brion, MD; Pablo J. Sánchez, MD; Charles R. Rosenfeld, MD; Walid A. Salhab, MD; Roy J. Heyne, MD; Sally S. Adams, MS RN CPNP; James Allen, RRT; Laura Grau, RN; Alicia Guzman; Gaynelle Hensley, RN; Elizabeth T. Heyne, PsyD PA-C; Jackie F. Hickman, RN; Melissa H. Leps, RN; Linda A. Madden, RN CPNP; Melissa Martin, RN; Nancy A. Miller, RN; Janet S. Morgan, RN; Araceli Solis, RRT; Lizette E. Lee, RN; Catherine Twell Boatman, MS CIMI; Diana M Vasil, MSN BSN RNC-NIC.

University of Utah Medical Center, Intermountain Medical Center, LDS Hospital, and Primary Children’s Medical Center (U10 HD53124, M01 RR64) – Bradley A. Yoder, MD; Roger G. Faix, MD; Sarah Winter, MD; Shawna Baker, RN; Karen A. Osborne, RN BSN CCRC; Carrie A. Rau, RN BSN CCRC; Sean Cunningham, PhD; Ariel Ford, PhD.

Wayne State University, Hutzel Women’s Hospital, and Children’s Hospital of Michigan (U10 HD21385) – Seetha Shankaran, MD; Athina Pappas, MD; Beena G. Sood, MD MS; Rebecca Bara, RN BSN; Thomas L. Slovis, MD (deceased); Elizabeth Billian, RN MBA; Laura A. Goldston, MA; Mary Johnson, RN BSN.

Figure 1.

(online only). Sample Selection Flowchart

Table 4.

Sensitivity Analyses

| Variable | N | Hand Function Deficit | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No deficit Mean (SD) | Any deficit Mean (SD) | p-value | ||

| Excluding children with any CP | ||||

| Manual Dexterity (standard score) | 303 | 6.90 (3.43) | 5.55 (4.02) | 0.027 |

| Aiming and Catching (standard score) | 304 | 9.57 (3.05) | 9.79 (4.01) | 0.688 |

| Balance (standard score) | 300 | 8.57 (2.97) | 8.00 (3.76) | 0.288 |

| Total Composite (standard score) | 298 | 7.78 (3.23) | 7.00 (4.29) | 0.187 |

| Excluding children with moderate/severe CP | ||||

| Manual Dexterity (standard score) | 309 | 6.89 (3.43) | 5.33 (4.05) | 0.009 |

| Aiming and Catching (standard score) | 311 | 9.55 (3.06) | 9.20 (4.42) | 0.520 |

| Balance (standard score) | 307 | 8.53 (2.98) | 7.59 (3.94) | 0.071 |

| Total Composite (standard score) | 304 | 7.75 (3.23) | 6.70 (4.38) | 0.071 |

| Excluding children with Full Scale IQ < 70 | ||||

| Manual Dexterity (standard score) | 281 | 7.20 (3.38) | 5.80 (4.05) | 0.027 |

| Aiming and Catching (standard score) | 282 | 9.69 (3.11) | 9.58 (4.43) | 0.855 |

| Balance (standard score) | 280 | 8.84 (2.83) | 7.97 (3.90) | 0.106 |

| Total Composite (standard score) | 278 | 8.04 (3.16) | 7.26 (4.33) | 0.195 |

Footnotes

List of additional members of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Development Neonatal Research Network is available at www.jpeds.com (Appendix)

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Duncan AF, Bann CM, Dempsey AG, Adams-Chapman I, Heyne R, Hintz SR, et al. Neuroimaging and Bayley-III correlates of early hand function in extremely preterm children. J Perinatol. 2019;39(3):488–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pitchford NJ, Papini C, Outhwaite LA, Gulliford A. Fine Motor Skills Predict Maths Ability Better than They Predict Reading Ability in the Early Primary School Years. Front Psychol. 2016;7:783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marr D, Cermak S, Cohn ES, Henderson A. Fine motor activities in Head Start and kindergarten classrooms. The American journal of occupational therapy : official publication of the American Occupational Therapy Association. 2003;57(5):550–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Corti EJ, Johnson AR, Riddle H, Gasson N, Kane R, Loftus AM. The relationship between executive function and fine motor control in young and older adults. Human movement science. 2017;51:41–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bala G, Krneta Z, Katic R. Effects of kindergarten period on school readiness and motor abilities. Collegium antropologicum. 2010;34 Suppl 1:61–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pulvermuller F, Hauk O, Nikulin VV, Ilmoniemi RJ. Functional links between motor and language systems. The European journal of neuroscience. 2005;21(3):793–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boulenger V, Roy AC, Paulignan Y, Deprez V, Jeannerod M, Nazir TA. Cross-talk between language processes and overt motor behavior in the first 200 msec of processing. Journal of cognitive neuroscience. 2006;18(10):1607–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grissmer D, Grimm KJ, Aiyer SM, Murrah WM, Steele JS. Fine Motor Skills and Early Comprehension of the World: Two New School Readiness Indicators. Developmental Psychology. 2010;46(5):1008–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Finer NN, Carlo WA, Walsh MC, Rich W, Gantz MG, Laptook AR, et al. Early CPAP versus surfactant in extremely preterm infants. The New England journal of medicine. 2010;362(21):1970–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hintz SR, Barnes PD, Bulas D, Slovis TL, Finer NN, Wrage LA, et al. Neuroimaging and neurodevelopmental outcome in extremely preterm infants. Pediatrics. 2015;135(1):e32–e42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hintz SR, Vohr BR, Bann CM, Taylor HG, Das A, Gustafson KE, et al. Preterm Neuroimaging and School-Age Cognitive Outcomes. Pediatrics. 2018;142(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown T, Lalor A. The movement assessment battery for children—second edition (MABC-2): a review and critique. Physical & occupational therapy in pediatrics. 2009;29(1):86–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Henderson S, Sugden D, Barnett A. Movement Assessment Battery for Children–2. 2007London: Harcourt Assessment. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taylor HG, Klein N, Drotar D, Schluchter M, Hack M. Consequences and risks of <1000-g birth weight for neuropsychological skills, achievement, and adaptive functioning. Journal of developmental and behavioral pediatrics : JDBP. 2006;27(6):459–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laucht M, Esser G, Schmidt MH. Developmental Outcome of Infants Born with Biological and Psychosocial Risks. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1997;38(7):843–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carlo WA, McDonald SA, Fanaroff AA, Vohr BR, Stoll BJ, Ehrenkranz RA, et al. Association of antenatal corticosteroids with mortality and neurodevelopmental outcomes among infants born at 22 to 25 weeks’ gestation. Jama. 2011;306(21):2348–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen G, Chiang W-L, Shu B-C, Guo YL, Chiou S-T, Chiang T-l. Associations of caesarean delivery and the occurrence of neurodevelopmental disorders, asthma or obesity in childhood based on Taiwan birth cohort study. BMJ open. 2017;7(9):e017086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Janz-Robinson EM, Badawi N, Walker K, Bajuk B, Abdel-Latif ME, Bowen J, et al. Neurodevelopmental outcomes of premature infants treated for patent ductus arteriosus: a population-based cohort study. The Journal of pediatrics. 2015;167(5):1025–32. e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Doyle LW, Victorian Infant Collaborative Study G, Victorian Infant Collaborative Study G, for the Victorian Infant Collaborative Study G. Outcome at 5 Years of Age of Children 23 to 27 Weeks’ Gestation: Refining the Prognosis. Pediatrics. 2001;108(1):134–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duncan AF, Watterberg KL, Nolen TL, Vohr BR, Adams-Chapman I, Das A, et al. Effect of ethnicity and race on cognitive and language testing at age 18–22 months in extremely preterm infants. The Journal of pediatrics. 2012;160(6):966–71. e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pierrat V, Marchand-Martin L, Arnaud C, Kaminski M, Resche-Rigon M, Lebeaux C, et al. Neurodevelopmental outcome at 2 years for preterm children born at 22 to 34 weeks’ gestation in France in 2011: EPIPAGE-2 cohort study. BMJ. 2017;358:j3448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hafström M, Källén K, Serenius F, Maršál K, Rehn E, Drake H, et al. Cerebral Palsy in Extremely Preterm Infants. Pediatrics. 2018;141(1):e20171433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jarjour IT. Neurodevelopmental outcome after extreme prematurity: a review of the literature. Pediatric neurology. 2015;52(2):143–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spittle AJ, Cameron K, Doyle LW, Cheong JL. Motor Impairment Trends in Extremely Preterm Children: 1991–2005. Pediatrics. 2018;141(4). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Kieviet JF, Piek JP, Aarnoudse-Moens CS, Oosterlaan J. Motor Development in Very Preterm and Very Low-Birth-Weight Children From Birth to Adolescence: A Meta-analysis. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2009;302(20):2235–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berteletti I, Booth JR. Perceiving fingers in single-digit arithmetic problems. Frontiers in psychology. 2015;6:226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mayes SD, Calhoun SL. Learning, attention, writing, and processing speed in typical children and children with ADHD, autism, anxiety, depression, and oppositional-defiant disorder. Child neuropsychology : a journal on normal and abnormal development in childhood and adolescence. 2007;13(6):469–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Breeman LD, Jaekel J, Baumann N, Bartmann P, Wolke D. Attention problems in very preterm children from childhood to adulthood: the Bavarian Longitudinal Study. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, and allied disciplines. 2016;57(2):132–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carlson AG, Rowe E, Curby TW. Disentangling fine motor skills’ relations to academic achievement: the relative contributions of visual-spatial integration and visual-motor coordination. The Journal of genetic psychology. 2013;174(5–6):514–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thomas AR, Lacadie C, Vohr B, Ment LR, Scheinost D. Fine Motor Skill Mediates Visual Memory Ability with Microstructural Neuro-correlates in Cerebellar Peduncles in Prematurely Born Adolescents. Cereb Cortex. 2017;27(1):322–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Geldof CJ, Oosterlaan J, Vuijk PJ, de Vries MJ, Kok JH, van Wassenaer-Leemhuis AG. Visual sensory and perceptive functioning in 5-year-old very preterm/very-low-birthweight children. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2014;56(9):862–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bolk J, Padilla N, Forsman L, Brostrom L, Hellgren K, Aden U. Visual-motor integration and fine motor skills at 6(1/2) years of age and associations with neonatal brain volumes in children born extremely preterm in Sweden: a population-based cohort study. BMJ open. 2018;8(2):e020478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Toussaint M, Goerick C. A bayesian view on motor control and planning From Motor Learning to Interaction Learning in Robots: Springer; 2010. p. 227–52. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Körding KP, Wolpert DM. Bayesian integration in sensorimotor learning. Nature. 2004;427(6971):244–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Greaves S, Imms C, Dodd K, Krumlinde-Sundholm L. Development of the Mini-Assisting Hand Assessment: evidence for content and internal scale validity. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 2013;55(11):1030–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Spittle A, Orton J, Anderson PJ, Boyd R, Doyle LW. Early developmental intervention programmes provided post hospital discharge to prevent motor and cognitive impairment in preterm infants. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2015(11):Cd005495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Niklasson M, Norlander T, Niklasson I, Rasmussen P. Catching-up: Children with developmental coordination disorder compared to healthy children before and after sensorimotor therapy. PloS one. 2017;12(10):e0186126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tramontano M, Medici A, Iosa M, Chiariotti A, Fusillo G, Manzari L, et al. The Effect of Vestibular Stimulation on Motor Functions of Children With Cerebral Palsy. Motor control. 2017;21(3):299–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ohl AM, Graze H, Weber K, Kenny S, Salvatore C, Wagreich S. Effectiveness of a 10-week tier-1 response to intervention program in improving fine motor and visual-motor skills in general education kindergarten students. The American journal of occupational therapy : official publication of the American Occupational Therapy Association. 2013;67(5):507–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Case-Smith J, Frolek Clark GJ, Schlabach TL. Systematic review of interventions used in occupational therapy to promote motor performance for children ages birth-5 years. The American journal of occupational therapy : official publication of the American Occupational Therapy Association. 2013;67(4):413–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.