Abstract

Among Medicare beneficiaries, dental, vision, and hearing services could be characterized as high need, high cost, and low use. While Medicare does not cover most of these services, coverage has increased recently as a result of changes in state Medicaid programs and increased enrollment in Medicare Advantage (MA) plans, many of which offer these services as supplemental benefits. Using data from the 2016 Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey, this analysis shows that MA plans are filling an important gap in dental, vision, and hearing coverage, particularly among low- and middle-income beneficiaries. In 2016 only 21 percent of beneficiaries in traditional Medicare had purchased a stand-alone dental plan, whereas 62 percent of MA enrollees were in plans with a dental benefit. Among Medicare beneficiaries with coverage overall, out-of-pocket expenses still made up 70 percent of dental spending, 62 percent of vision spending, and 79 percent of hearing spending. While Medicare beneficiaries are enrolling in private coverage options, they are not getting adequate financial protection. This article examines these findings in the context of recent proposals in Congress to expand Medicare coverage of dental, vision, and hearing services.

Over the past two decades, dental, vision, and hearing health have emerged as public health concerns. Once thought of as negligible aspects of aging, poor oral health, vision loss, and hearing loss have been independently linked to numerous negative health outcomes. Key reports from the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine and the President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology have highlighted the challenges in obtaining necessary dental, vision, and hearing care, particularly among older adults and other vulnerable populations.1–4

While access to dental, vision, and hearing services is low, need for the services is high.5–8 Nineteen percent of older adults have untreated tooth decay, and another nineteen percent have complete tooth loss.9 Vision loss affects thirty-seven million Americans ages fifty and older, and two-thirds of adults ages seventy and older have clinically relevant hearing loss.10 Research has shown how poor oral, vision, and hearing outcomes affect poor health outcomes if left untreated. Poor oral health limits one’s ability to eat and speak11 and is associated with poor health outcomes, including diabetes,12 cardiovascular disease,13 and pulmonary infections.14 Vision loss is associated with an increased risk of falls,15 depression,16 cognitive impairment,17,18 hospitalization,19 and mobility limitations20 among older adults. Hearing loss has been associated with dementia,21 falls,22 and depression,23 as well as higher health care spending and rates of hospitalizations and thirty-day readmissions.24 These three conditions also affect social engagement among older adults, whether because of difficulty interacting and communicating,25 fear of leaving familiar environments or inability to see faces,26 or fear of smiling or embarrassment due to the condition of one’s mouth.27 Despite the high prevalence of these poor health outcomes among older adults, little headway has been made in improving access to relevant dental, vision, or hearing services.

Low rates of use of dental, vision, and hearing preventive and treatment services are due in part to the high costs of and lack of insurance coverage for these services. Traditional Medicare (Parts A and B) does not cover dental services; vision care for refraction services, corrective lenses, or low-vision devices; or hearing care for its beneficiaries. Beneficiaries in traditional Medicare can choose to purchase supplemental coverage (also known as stand-alone plans) for dental, vision, or both services, but rates of up-take for such plans are low. Stand-alone plans for hearing coverage do not exist, so beneficiaries in traditional Medicare do not have access to financial protection from the costs related to hearing aids and services. Some Medicare Advantage (MA, also known as Medicare Part C) plans offer these supplemental benefits as part of their benefit packages, by either using rebate dollars or charging additional premiums. However, generosity of coverage varies greatly by plans, and just over one-third of Medicare beneficiaries are enrolled in MA plans.28,29

The needs of the Medicare population have changed greatly since 1965, when Medicare was enacted. Since that time, the life expectancy of Medicare beneficiaries at age sixty-five has increased by almost five years (to 84.4 years),30 and tooth, vision, and hearing loss—once considered a natural part of aging—have been shown to greatly affect people’s quality of life, social engagement and contributions, and other health outcomes, as mentioned above. Treatment options and technologies to address oral health, vision loss, and hearing loss have also advanced greatly in both effectiveness and cost since 1965.31,32 As a consequence, many federal policy makers advocate including coverage of dental, vision, and hearing aid coverage and related services as part of the traditional Medicare program. Rules governing traditional Medicare provide the minimum benefit requirements for MA plans. Therefore, any benefits included under traditional Medicare would also be included in all MA plans. To date, there has been little consensus as to what scope of dental, vision, and hearing services the Medicare program should cover and how it should be financed. In this article we assess the extent of the current access, coverage, and cost challenges for dental, vision, and hearing care by Medicare beneficiaries and describe the coverage options that could be considered under different Medicare benefit designs.

Study Data And Methods

Data Source

This analysis used data from the 2016 Cost Supplement to the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (MCBS), a nationally representative survey of Medicare beneficiaries. To confirm enrollment in Medicare Advantage plans with supplemental benefits, we linked MA plan numbers to the plans’ benefit data for 2016. The MCBS oversamples older and younger Medicare beneficiaries (those ages eighty-five and older and those ages sixty-four and younger), as well as those participating in accountable care organizations and Hispanic beneficiaries. We used survey weights in all analyses to account for this oversampling and to generate nationally representative estimates of Medicare beneficiaries in 2016. In that year 14,062 Medicare beneficiaries were interviewed for the survey, representing 58,641,440 people nationally who had ever been enrolled in Medicare in 2016.

Beneficiary Categories

Across the analyses, we compared three main categories of Medicare beneficiaries. People were allocated to Medicaid if the administrative files confirmed that they were enrolled in Medicaid in addition to Medicare (dually enrolled) for at least one month in the study year. The remaining Medicare beneficiaries were allocated to either traditional Medicare or Medicare Advantage based on their enrollment throughout the year. These groups were mutually exclusive.

Income relative to the federal poverty level is determined by household income for the respondent and the federal poverty level determined by the Census Bureau for people ages sixty-five and older by household size. For the purposes of this study, we defined low-income beneficiaries as those with incomes of up to 100 percent of poverty ($11,511 for a single person in 2016). High-income beneficiaries were those with incomes of at least 400 percent of poverty.

Spending And Coverage Categories

The MCBS creates general categories of spending across services such as inpatient, outpatient, and medical provider (services provided in a doctor’s office). Use of dental services constitute one such service category. To calculate spending related to vision, and hearing services, we were able to identify use and spending related to optometrist services or to the purchase of eyeglasses (which we used to determine vision-related costs) and use and spending related to audiologist services or to the purchase or repair of hearing aids (which we used to determine hearing-related costs). All total costs are also separated by payer—including private insurance, Medicare, Medicaid, and out-of-pocket spending.

Coverage of dental, vision, and hearing services was constructed from and limited by the information available through the MCBS for people in traditional Medicare. We were able to complement the self-reported information with MA plan benefit data for those enrolled in MA plans. The questions in the MCBS are limited to self-reports of dental and vision coverage. As there are no stand-alone plans available for hearing aids or services, the survey does not ask about them. To account for the coverage of hearing care that exists through some state Medicaid programs, we assumed that Medicare beneficiaries who were dually enrolled in Medicaid and lived in states that covered hearing care as a state benefit in 2016 had hearing coverage.29

Limitations

This study had some important limitations. First, given that no administrative claims data are available to confirm the use and cost of dental, vision, or hearing services (as they are not paid for by Medicare), this study relied on self-reported information.

Second, to determine coverage of dental, vision, and hearing services via Medicaid, we assumed that people with Medicaid who lived in states providing that benefit in their Medicaid plan had coverage. However, the eligibility thresholds and generosity of benefits of Medicaid plans vary greatly across states. For example, some state Medicaid plans cover people with mild hearing loss, while other plans cover hearing aids and services only once the hearing loss is more severe.29 We were not able to account for these differences in our analysis.

Study Results

Access To Dental, Vision, And Hearing Care

DENTAL: One in two Medicare beneficiaries reported in 2016 having had a dental visit in the past twelve months, although levels of access varied substantially by income: 27 percent of low-income beneficiaries had had a visit, compared to 73 percent of high-income beneficiaries (exhibit 1). Ten percent of all Medicare beneficiaries said that they had not had any dental visit in the previous twelve months because of cost. Cost as a restriction was more prevalent among lower-income beneficiaries than it was among higher-income beneficiaries.

VISION: In 2016, 39 percent of Medicare beneficiaries reported having trouble seeing even with their glasses, and only 58 percent of those beneficiaries reported having had an eye exam in the past twelve months. Trouble seeing even with glasses was more likely among beneficiaries in the lowest income group (48 percent), compared to those in the highest income group (32 percent). The proportion of those with vision trouble who had had an eye exam was lower among low-income beneficiaries (47 percent), compared to high-income beneficiaries (67 percent).

HEARING: Forty-five percent of all Medicare beneficiaries reported some trouble hearing even with a hearing aid.While fewer low-income beneficiaries reported having trouble hearing than those at higher income levels, only 7 percent of those with low incomes who reported hearing trouble had gone to an audiologist, compared to 14 percent of those with high incomes. However, the relationship with income was not monotonic.

Exhibit 1.

Access to dental, vision, and hearing services among Medicare beneficiaries, by income, 2016

| Income (% of federal poverty level) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | <100% | 100–149% | 150–199% | 200–399% | ≥400% | |

| Population | 100% | 15% | 15% | 13% | 28% | 29% |

| Dental | ||||||

| Had dental visit in past year | 50 | 27 | 29 | 39 | 54 | 73 |

| Did not have dental visit in past year due to cost | 10 | 16 | 17 | 17 | 8 | 3 |

| Vision | ||||||

| Trouble seeing even with glasses | 39 | 48 | 46 | 39 | 38 | 32 |

| Had an eye exam in the past year if trouble seeing | 58 | 47 | 51 | 57 | 61 | 67 |

| Hearing | ||||||

| Trouble hearing even with hearing aid | 45 | 39 | 42 | 45 | 50 | 45 |

| Went to audiologist if trouble hearing | 12 | 7 | 13 | 9 | 12 | 14 |

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data for 2016 from the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey.

Coverage Of Dental, Vision, And Hearing Care

Thirty-five percent of Medicare beneficiaries with high incomes (400 percent or more of the federal poverty level) had dental coverage, compared to 26 percent of those with low incomes (less than 100 percent of poverty) (exhibit 2). More high-income beneficiaries got their dental coverage through stand-alone dental plans (20 percent) than from MA plans (15 percent). With the exception of low-income beneficiaries, who got most of their coverage through Medicaid, most Medicare beneficiaries got their dental coverage through their MA plan.

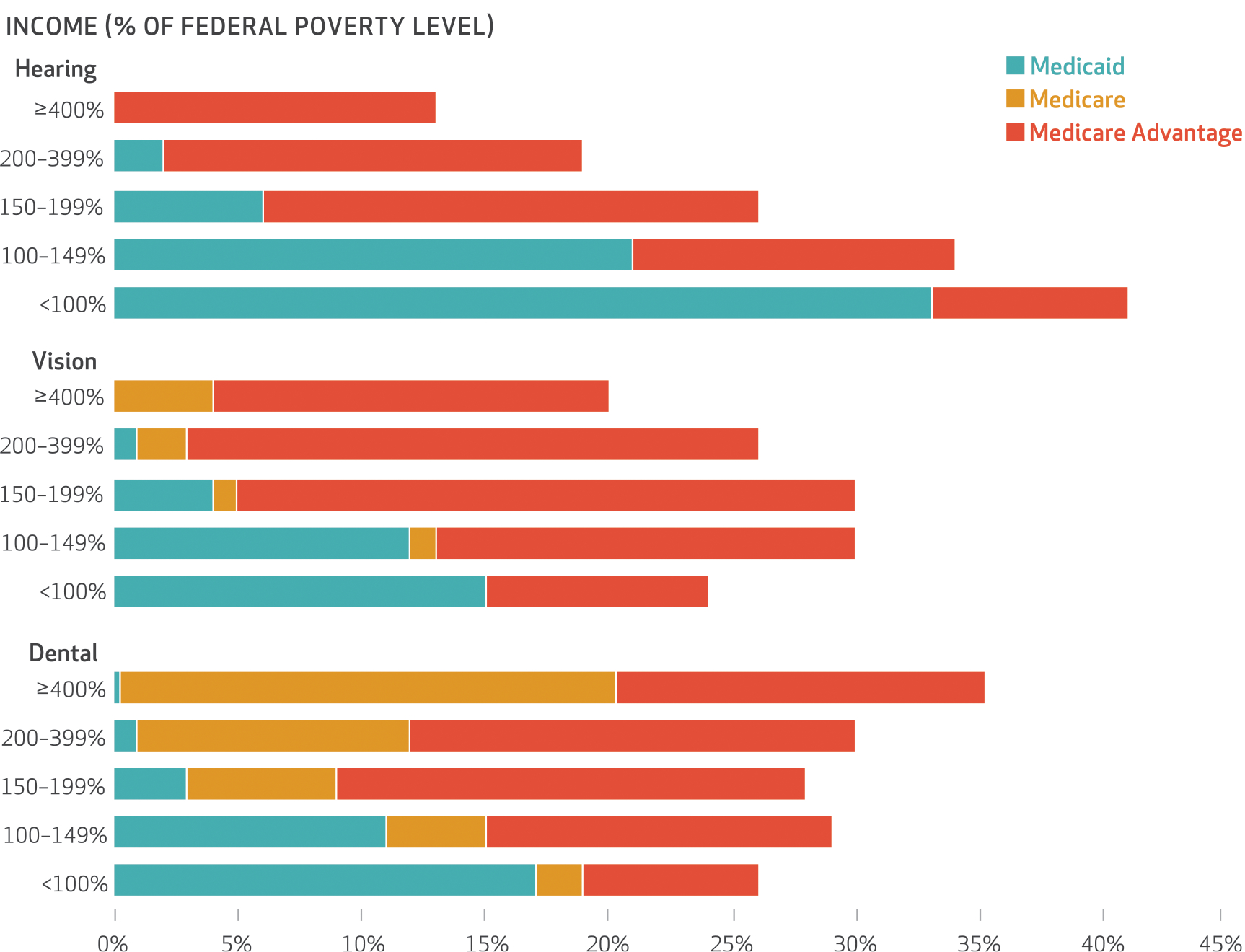

Exhibit 2. Percent of Medicare beneficiaries with dental, vision, and hearing coverage, by income and type of insurance, 2016.

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data for 2016 from the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey. NOTE “Medicare” refers to stand-alone plans in traditional Medicare.

The role of stand-alone plans in providing coverage was substantially lower in vision coverage, the majority of which was provided by Medicaid and MA plans. Coverage of hearing care was higher among low-income beneficiaries, with 41 percent covered (33 percent of those in Medicaid and 8 percent of those in MA plans), compared to 13 percent of high-income beneficiaries (all of whom received coverage through MA plans). While there was variation in the roles of stand-alone, Medicaid, and MA coverage across dental, vision, and hearing services, MA plans provided the bulk of coverage for all three services among Medicare beneficiaries—particular ly for those with incomes of 150–199 percent of poverty.

Cost And Financial Burden Of Dental, Vision, And Hearing Care

Sixty-two percent of MA enrollees who were not dually enrolled in Medicaid had dental coverage in 2016, compared to 28 percent of Medicare beneficiaries who were dually enrolled (exhibit 3). Twenty-one percent of traditional Medicare beneficiaries were covered for dental care through stand-alone plans. Overall, people who had dental coverage were more likely to have had at least one dental visit in the past twelve months (61 percent), compared to those who did not have dental coverage (42 percent). Financial protection was greatest for those who had dental coverage, although there was still substantial out-of-pocket spending for beneficiaries overall, averaging $894 for those with dental coverage and $928 for those without.

Exhibit 3.

Use and cost of dental, vision, and hearing services among Medicare beneficiaries, by type of insurance, 2016

| Type of insurance | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (N = 58,641,440) | Medicaid (n = 11,728,288) | Medicare (n = 31,079,963) | MA (n = 15,833,189) | |||||

| Covered | Not covered | Covered | Not covered | Covered | Not covered | Covered | Not covered | |

| DENTAL | ||||||||

| Has insurance (%) | 36 | 64 | 28 | 72 | 21 | 79 | 62 | 38 |

| Had dental visit in past 12 months (% of those in the row above) | 61 | 42 | 27 | 17 | 80 | 49 | 55 | 52 |

| Spending on dental care among those with a visit ($) | 1,278 | 1,065 | 549 | 791 | 1,329 | 1,151 | 1,331 | 925 |

| OOP spending on dental care among those with a visit ($) | 894 | 928 | 348 | 614 | 872 | 1,005 | 1,009 | 833 |

| OOP spending (% of total spending) | 70 | 87 | 63 | 78 | 66 | 87 | 76 | 90 |

| VISION | ||||||||

| Has insurance (%) | 26 | 74 | 26 | 74 | 4 | 96 | 67 | 33 |

| Had eye exam in past 12 months (% of those in the row above) | 56 | 54 | 48 | 43 | 74 | 57 | 57 | 56 |

| Spending on vision care among those with a visit ($) | 333 | 353 | 272 | 275 | 415 | 369 | 331 | 336 |

| OOP spending on vision care among those with a visit ($) | 206 | 229 | 109 | 108 | 252 | 242 | 215 | 271 |

| OOP spending (% of total spending) | 62 | 65 | 40 | 39 | 61 | 66 | 65 | 81 |

| HEARING | ||||||||

| Has insurance (%) | 24 | 76 | 49 | 51 | 0 | 100 | 52 | 48 |

| Had a hearing visit in past 12 months (% of those in the row above) | 6 | 8 | 3 | 3 | —a | 9 | 8 | 8 |

| Spending on hearing care among those with a visit ($) | 981 | 1,483 | 279 | 565 | —a | 1,526 | 1,163 | 1,569 |

| OOP spending on hearing care among those with a visit ($) | 775 | 1,131 | 203 | 442 | —a | 1,116 | 924 | 1,393 |

| OOP spending (% of total spending) | 79 | 76 | 73 | 78 | —a | 73 | 79 | 89 |

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data for 2016 from the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (MCBS). NOTES Types of insurance are mutually exclusive. People with any Medicaid coverage were placed in the Medicaid category even if they received their Medicare coverage through Medicare Advantage (MA). This is why the distribution of the population in MA looks smaller than is generally stated. Dental and vision coverage in traditional Medicare are through stand-alone plans. There are no stand-alone hearing plans. It is possible that some employer-sponsored retiree plans include hearing coverage, but there are no direct questions in the MCBS about self-reported hearing coverage. OOP is out-of-pocket.

Not applicable.

Sixty-seven percent of MA enrollees were covered for vision services, compared to 4 percent who reported having any vision coverage through stand-alone plans in traditional Medi care. Overall, Medicare beneficiaries with vision coverage were about as likely to report having had an eye exam in the past twelve months (56 percent) as those who did not have coverage (54 percent). Medicaid beneficiaries had the lowest share of out-of-pocket spending, contributing less than half of the total costs. Total spending among people in traditional Medicare with vision coverage was high ($415) compared to spending among MA enrollees with coverage ($331).

Coverage for hearing aids and services is not available as a stand-alone plan for purchase, and therefore traditional Medicare beneficiaries do not have hearing coverage unless it is through an employer-sponsored retiree plan. Fifty-two percent of MA enrollees were in plans with a hearing benefit, and 49 percent of Medicare beneficiaries dually enrolled in Medicaid had access to hearing coverage through their MA plan or Medicaid state benefit. Spending on hearing care was highest among traditional Medicare and MA enrollees without hearing coverage ($1,526 and $1,569, respectively). Spending was lower among MA enrollees with hearing coverage, compared to those without ($1,163 versus $1,569), although the share that accessed hearing care services was the same in both groups (8 percent).

Discussion

Medicare beneficiaries, like everyone else, thrive when they have good oral, hearing, and visual health that allows them to talk, eat, communicate with others, and engage with their surroundings. Studies have shown that if oral, visual, and hearing health are not maintained, there are negative consequences for one’s general health—which results in poor outcomes for beneficiaries as well as avoidable and costly emergency department and hospital visits. Older adults are more likely to experience poor oral, visual, and hearing health, partly as a product of aging but also because of poor access to preventive services over time that could have maintained better health. Given the need in this population, access to dental, vision, and hearing services is remarkably low. As confirmed by this analysis, people with incomes at or near the poverty level—who have the least ability to pay for services out of pocket—have the poorest access to care and are the most likely to report cost as the reason for not accessing dental care.

Stand-alone dental and vision plans were once the only option Medicare beneficiaries had for getting financial protection from the high costs of these services, although the plans were restricted to those who could afford the additional monthly premiums. Now beneficiaries have the option of accessing coverage through MA plans that offer coverage for these services at no charge or a low cost. As shown in this analysis, MA plans are filling the coverage gap, particularly among those with low or middle incomes (100–399 percent of poverty). However, more research is required to understand the generosity of these benefits. This analysis suggests that even MA enrollees with coverage were paying a high proportion of the total cost out of pocket (65 percent of vision costs, 76 percent of dental costs, and 79 percent of hearing costs).

Policy Opportunities

Policy makers have been debating the inclusion of dental, vision, and hearing services in traditional Medicare for decades. Despite wide consensus among researchers and policy makers that these services are important for Medicare beneficiaries and that they can affect the beneficiaries’ overall health and well-being, no consensus has been reached for improving beneficiaries’ access to these services and reducing the financial burden associated with them. In the meantime, other policy changes have affected this policy landscape. Medicare Advantage now covers just over a third of Medicare beneficiaries and is driving the improvements in coverage for dental, vision, and hearing services in this population. As part of the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018, the Creating High-Quality Results and Outcomes Necessary to Improve Chronic (CHRONIC) Care Act gave MA plans the flexibility to offer more supplemental benefits and the ability to tailor those benefits to particular high-need subgroups.33 Other relevant policy changes include the Over-the-Counter Hearing Aid Act (part of the FDA Reauthorization Act of 2017), which requires the Food and Drug Administration to develop regulations for an over-the-counter hearing aid to address mild-to-moderate hearing loss by the end of 2020. While the outcomes of this policy change are yet to be realized, it is expected that the market for hearing aids will increase with the entry of technology companies, reducing the price of hearing aids significantly.34 Across all three sectors, some changes are already occurring, with the increase in online offerings and big-box stores providing discounted eyeglasses, hearing aids, and orthodontia.

In many consecutive sessions of Congress, legislation has been introduced that would expand Medicare Part B benefits to include dental, vision, and hearing coverage for all beneficiaries. The current iteration of the legislation, the Medicare Dental, Vision, and Hearing Benefit Act of 2019, H.R. 1393, was introduced by Rep. Lloyd Doggett (D-TX) in February 2019. Under this bill, these services would be covered at 80 percent, with 20 percent cost sharing for beneficiaries, and coverage would be phased in over time to avoid excessive costs that could be anticipated from pent-up demand for these services in the population. This legislation provides some qualifiers regarding frequency of services covered (for example, it would cover only two preventive dental visits per year). However, all types of services appear to qualify for coverage (that is, the full scope from preventive to cosmetic dental services would be covered)—although the health and human services secretary would have the discretion to make this decision. This policy option offers maximum coverage across the Medicare population and provides generous coverage of these services. Consequently, the cost of this benefit expansion proposal could be a barrier to the bill’s passage.

Recent developments in the House of Representatives have sought to address this criticism in two ways, by identifying savings within the program and by proposing a more moderate coverage option. The Lower Drug Costs Now Act of 2019, H.R. 3—introduced in September 2019 by Rep. Frank Pallone Jr. (D-NJ)—would allow the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services to negotiate prices for certain prescription drugs. Medicare’s savings from this bill have been estimated by the Congressional Budget Office to be $345 billion for the period 2023–29.35 In her remarks on the bill, Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-CA) signaled that savings from this bill would be re-invested in “improved benefits for Medicare, hearing, visual, dental, et cetera.”36 This statement coincided with the introduction in the House in October 2019 of three separate bills for dental, vision, and hearing services: the Medicare Hearing Act of 2019, H.R. 4618, introduced by Rep. Lucy McBath (D-GA); the Medicare Dental Act of 2019, H.R. 4650, introduced by Rep. Robin Kelly (D-IL); and the Medicare Vision Act of 2019, H.R. 4665, introduced by Rep. Kim Schrier (D-WA). On December 12, 2019, the House of Representatives passed a revised version of H.R. 3 that included these three bills within it, tying the passage of negotiating prescription drug prices under Medicare to the expansion of coverage for dental, vision, and hearing services for beneficiaries. The three separate bills (now part of H.R. 3) deviate from previous coverage proposals in that they offer a more moderate benefit package, which may therefore be less costly.

For hearing services, H.R. 3 would cover audiology services for the treatment of hearing loss among all beneficiaries, including hearing aid fitting and customization and communication strategies and support, but it would not cover the cost of devices. However, it would cover hearing aids for people with severe-to-profound hearing loss. This would result in coverage for a small but high-need population, while allowing the hearing aid market for those with mild-to-moderate hearing loss to operate under the regulations set forth in the Over-the-Counter Hearing Aid Act. The bill would also ensure that services were available to all beneficiaries, regardless of their degree of hearing loss.

For dental care, H.R. 3 identifies different levels of dental care (preventive and screening, as well as basic and major treatments) and proposes different cost sharing for these categories of care. Preventive, screening, and basic treatment services would be covered at 80 percent with 20 percent cost sharing from year one, whereas major treatments would be covered at 50 percent, and this coverage would be phased in over a four-year period. Excluding the coverage of cosmetic dental services, as the bill proposes, would help contain the costs of the program.

For vision services, H.R. 3 would cover one routine eye exam and one contact lens fitting every two years at 80 percent, with 20 percent cost sharing. In addition, either one pair of eyeglasses (lenses and frames) or a two-year supply of contact lenses would be covered, with the covered cost of frames in 2023 not exceeding $85.

These legislative proposals to expand Medicare Part B would apply to all beneficiaries regardless of whether they were enrolled in traditional Medicare or Medicare Advantage. The bills would likely have the greatest impact on improving access to dental, vision, and hearing services. An alternative way to address coverage gaps for dental, vision, and hearing services would be to offer a premium-financed, voluntary supplemental benefit like the Part D prescription drug benefit. Assuming that the benefit package would be similar to that in current private insurance offerings, the estimated monthly premium to cover these services would be $25 per enrolled beneficiary.5 As highlighted in this article, however, private coverage of dental, vision, and hearing services still results in high out-of-pocket spending among the people using the services.

Conclusion

While knowledge about the importance of dental, vision, and hearing services to general health has changed dramatically since the establishment of the Medicare program, policy makers have struggled to take the crucial steps required to improve access to these services for all Medicare beneficiaries. In this coverage vacuum, MA plans have increased their enrollment to cover just over a third of Medicare beneficiaries, with many plans offering dental, vision, or hearing coverage. This article has shown that the majority of MA enrollees are in plans that offer these benefits. Significant questions remain about the generosity of these plans and what options there are for financial protection for the beneficiaries who choose to be in traditional Medicare. This analysis has laid out the need for policy makers to take action on this issue and discussed some of the current proposals for dental, vision, and hearing benefits under Medicare.

Acknowledgments

The Commonwealth Fund supported this research (Grant No. 20171061).

Contributor Information

Amber Willink, Department of Health Policy and Management and in the Cochlear Center for Hearing and Public Health, both at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, in Baltimore, Maryland..

Nicholas S. Reed, Department of Epidemiology and in the Cochlear Center for Hearing and Public Health, both at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health..

Bonnielin Swenor, Wilmer Eye Institute, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, and Department of Epidemiology, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health..

Leah Leinbach, Department of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine..

Eva H. DuGoff, Department of Health Services Administration, School of Public Health, University of Maryland, in College Park..

Karen Davis, Department of Health Policy and Management, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health..

NOTES

- 1.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Hearing health care for adults: priorities for improving hearing technologies. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Institute of Medicine. Advancing oral health in America.Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3.President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology. Aging America and hearing loss: imperative of improved hearing technologies [Internet]. Washington (DC): Executive Office of the President; 2015. October [cited 2019 Dec 4]. Available from: https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/microsites/ostp/PCAST/PCAST%20hearing%20letter%20report.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Making eye health a population health imperative: vision for tomorrow. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Willink A, Schoen C, Davis K. Consideration of dental, vision, and hearing services to be covered under Medicare. JAMA. 2017;318(7): 605–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Willink A, Shoen C, Davis K. How Medicare could provide dental, vision, and hearing care for beneficiaries. Issue Brief (Commonw Fund). 2018;2018:1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Varadaraj V, Frick KD, Saaddine JB, Friedman DS, Swenor BK. Trends in eye care use and eyeglasses affordability: the US National Health Interview Survey, 2008–2016. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2019;137(4):391–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Willink A, Schoen C, Davis K. Dental care and Medicare beneficiaries: access gaps, cost burdens, and policy options. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(12):2241–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dye B, Thornton-Evans G, Li X, Iafolla T. Dental caries and tooth loss in adults in the United States, 2011–2012. NCHS Data Brief. 2015; (197):197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goman AM, Lin FR. Prevalence of hearing loss by severity in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2016; 106(10):1820–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gil-Montoya JA, de Mello AL, Barrios R, Gonzalez-Moles MA, Bravo M. Oral health in the elderly patient and its impact on general well-being: a nonsystematic review. Clin Interv Aging. 2015;10:461–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wolff LF. Diabetes and periodontal disease. Am J Dent. 2014;27(3): 127–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Friedewald VE, Kornman KS, Beck JD, Genco R, Goldfine A, Libby P, et al. The American Journal of Cardiology and Journal of Periodontology editors’ consensus: periodontitis and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Am J Cardiol. 2009;104(1): 59–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Azarpazhooh A, Leake JL. Systematic review of the association between respiratory diseases and oral health. J Periodontol. 2006;77(9): 1465–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dhital A, Pey T, Stanford MR. Visual loss and falls: a review. Eye (Lond). 2010;24(9):1437–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang X, Bullard KM, Cotch MF, Wilson MR, Rovner BW, McGwin G Jr, et al. Association between depression and functional vision loss in persons 20 years of age or older in the United States, NHANES 2005–2008. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013; 131(5):573–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Swenor BK, Wang J, Varadaraj V, Rosano C, Yaffe K, Albert M, et al. Vision impairment and cognitive outcomes in older adults: the Health ABC Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2019;74(9):1454–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zheng DD, Swenor BK, Christ SL, West SK, Lam BL, Lee DJ. Longitudinal associations between visual impairment and cognitive functioning: the Salisbury Eye Evaluation Study. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2018; 136(9):989–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bal S, Kurichi JE, Kwong PL, Xie D, Hennessy S, Na L, et al. Presence of vision impairment and risk of hospitalization among elderly Medicare beneficiaries. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2017;24(6):364–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Swenor BK, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L, Newman AB, Rubin S, Wilson V. Visual impairment and incident mobility limitations: the Health, Aging and Body Composition study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(1):46–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin FR, Metter EJ, O’Brien RJ, Resnick SM, Zonderman AB, Ferrucci L. Hearing loss and incident dementia. Arch Neurol. 2011;68(2): 214–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin FR, Ferrucci L. Hearing loss and falls among older adults in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(4):369–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mener DJ, Betz J, Genther DJ, Chen D, Lin FR. Hearing loss and depression in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(9):1627–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reed NS, Altan A, Deal JA, Yeh C, Kravetz AD, Wallhagen M, et al. Trends in health care costs and utilization associated with untreated hearing loss over 10 years. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019; 145(1):27–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mick P, Kawachi I, Lin FR. The association between hearing loss and social isolation in older adults. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014; 150(3):378–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coyle CE, Steinman BA, Chen J. Vi sual acuity and self-reported vision status. J Aging Health. 2017;29(1): 128–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Health Policy Institute. Oral health and well-being in the United States [Internet]. Chicago (IL): American Dental Association; [cited 2019 Dec 4]. Available from: https://www.ada.org/~/media/ADA/Science%20and%20Research/HPI/OralHealthWell-Being-StateFacts/US-Oral-Health-Well-Being.pdf?la=en [Google Scholar]

- 28.Freed M, Neuman T, Jacobson G. Drilling down on dental coverage and costs for Medicare beneficiaries [Internet]. San Francisco (CA): Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2019. March 13 [cited 2019 Dec 4]. Available from: https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/drilling-down-on-dental-coverage-and-costs-for-medicare-beneficiaries/ [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arnold ML, Hyer K, Chisolm T. Medicaid hearing aid coverage for older adult beneficiaries: a state-by-state comparison. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(8):1476–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arias E, Xu J. United States life tables, 2017. National Vital Statistics Reports [serial on the Internet]. 2019. June 24 [cited 2019 Dec 4]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr68/nvsr68_07-508.pdf [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Whitson HE, Lin FR. Hearing and vision care for older adults: sensing a need to update Medicare policy. JAMA. 2014;312(17):1739–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lamster IB, Eaves K. A model for dental practice in the 21st century. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(10): 1825–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Willink A, DuGoff EH. Integrating medical and nonmedical services—the promise and pitfalls of the CHRONIC Care Act. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(23):2153–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reed NS, Lin FR, Willink A. Hearing care access? Focus on clinical services, not devices. JAMA. 2018; 320(16):1641–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Swagel PL. Re: Effects of drug price negotiation stemming from Title 1 of H.R. 3, the Lower Drug Costs Now Act of 2019, on spending and revenues related to Part D of Medicare [Internet] Washington (DC): Congressional Budget Office; 2019. October 11 [cited 2019 Dec 4]. Available from: https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2019-10/hr3ltr.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nancy Pelosi [Internet]. Washington (DC): House of Representatives; Press release, Pelosi remarks at press conference on introduction of H.R. 3, the Lower Drug Costs Now Act; 2019. September 19 [cited 2019 Dec 4]. Available from: https://www.speaker.gov/newsroom/91919-2 [Google Scholar]