Abstract

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is widely prevalent, associated with morbidity and mortality, but may be lessened with timely implementation of evidence-based strategies including blood pressure (BP) control. Nonetheless, an evidence-practice gap persists. We synthesize the evidence for clinician-facing interventions to improve hypertension management in CKD patients in primary care.

Methods

Electronic databases and related publications were queried for relevant studies. We used a conceptual model to address heterogeneity of interventions. We conducted a quantitative synthesis of interventions on blood pressure (BP) outcomes and a narrative synthesis of other CKD relevant clinical outcomes. Planned subgroup analyses were performed by (1) study design (randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or nonrandomized studies (NRS)); (2) intervention type (guideline-concordant decision support, shared care, pharmacist-facing); and (3) use of behavioral/implementation theory.

Results

Of 2704 manuscripts screened, 73 underwent full-text review; 22 met inclusion criteria. BP target achievement was reported in 15 and systolic BP reduction in 6 studies. Among RCTs, all interventions had a significant effect on BP control, (pooled OR 1.21; 95% CI 1.07 to 1.38). Subgroup analysis by intervention type showed significant effects for guideline-concordant decision support (pooled OR 1.19; 95% CI 1.12 to 1.27) but not shared care (pooled OR 1.71; 95% CI 0.96 to 3.03) or pharmacist-facing interventions (pooled OR 1.04; 95% CI 0.82 to 1.34). Subgroup analysis finding was replicated with pooling of RCTs and NRS. The five contributing studies showed large and significant reduction in systolic BP (pooled WMD − 3.86; 95% CI − 7.2 to − 0.55). Use of a behavioral/implementation theory had no impact, while RCTs showed smaller effect sizes than NRS.

Discussion

Process-oriented implementation strategies used with guideline-concordant decision support was a promising implementation approach. Better reporting guidelines on implementation would enable more useful synthesis of the efficacy of CKD clinical interventions integrated into primary care.

PROSPERO Registration Number

CRD42018102441

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s11606-020-06103-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Key Words: chronic kidney disease, blood pressure control, primary care practitioner interventions, systematic review, guideline implementation, implementation strategies

BACKGROUND

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) affects 8–16% people worldwide,1 and is a strong contributor to morbidity and mortality.2 CKD often remains undiagnosed and/or poorly managed, especially in older individuals,1, 3, 4 despite existing guidelines for diagnosing and managing the disease.5–7 Optimal CKD care may slow the rate of CKD progression and decrease the morbidity and mortality in this high-risk population.8 Most patients with CKD particularly early CKD are managed in the primary care setting,1 yet there is limited evidence of successful interventions to improve CKD management in primary care and their associated implementation strategies.9 Previous systematic reviews of interventions targeted at primary care clinicians managing patients with CKD have examined a number of intervention strategies. These interventions have been delivered in a variety of ways, including Chronic Disease Management (CDMs) strategies,10 multifaceted care approaches,11 continuous improvement interventions,12 clinical pathways for primary care,13 e-alerts,14, 15 pharmacy-facing interventions,16 and nurse-led disease management programs or models of care interventions for chronic disease.14, 17 Except for two,18, 19 most of these reviews included studies from acute care settings and did not differentiate between interventions specifically targeting clinicians from those focused on patients. More importantly, these reviews conflated the intervention with the implementation process, providing limited clarity concerning the intervention’s core disease management elements vs. the process of its implementation in the primary care setting. This knowledge is necessary to guide the development of successful and sustainable evidence-based practices to manage CKD, and potentially other chronic diseases, in primary care.

We therefore conducted a systematic review of published literature between 2000 and late 2017, seeking to identify both intervention types and implementation intervention strategies that were most likely to improve clinical and process outcomes for patients with CKD in the primary care setting.

METHODS

This study adheres to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analysis (PRISMA).20 This systematic review is registered with PROSPERO (registration number: CRD42018102441; http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO). A protocol of this systematic review has been published.21

Eligibility Criteria

Details of the eligibility and inclusion criteria are included in the published systematic protocol21 and reflected in Figure 2. We excluded studies that were in primitive clinical settings and those that did not separate data from primary care and specialty practice.

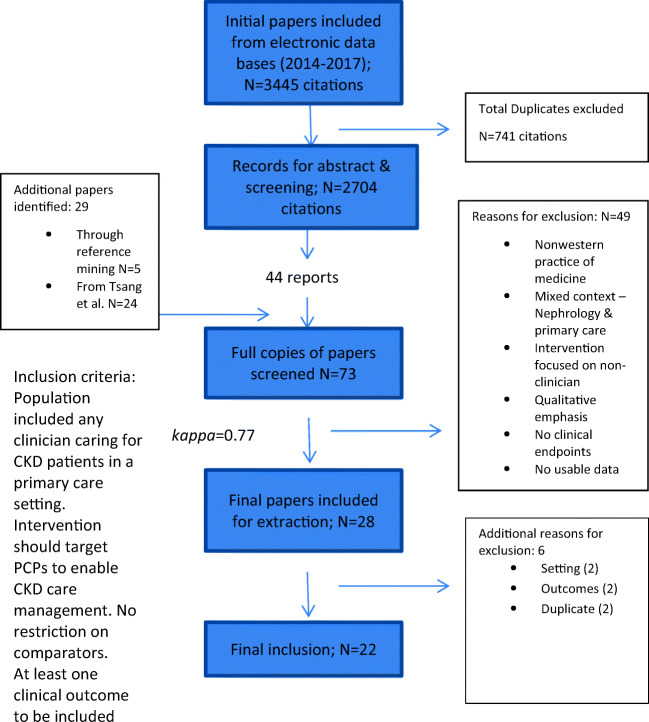

Figure 2.

PRISMA flow diagram of included studies.

Conceptual Model

Three frameworks guided our conceptual approach to address the anticipated heterogeneity in interventions targeting CKD management in order to synthesize evidence of their efficacy (Fig. 1). The Chronic Care Model (CCM),22, 23 relevant to primary care settings, enabled a meaningful categorization of interventions based on their core disease management elements. Proctor et al.’s framework24 provided us guidance to distinguish these interventions (the “what”) from implementation processes (the “how”) to integrate them into the practice. The Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) framework25 further enabled us to identify and extract both explicitly defined and implicit implementation processes employed in each study. This list of 73 implementation strategies is categorized into nine conceptually distinct clusters to enable better tailoring of implementation strategies to different settings.26

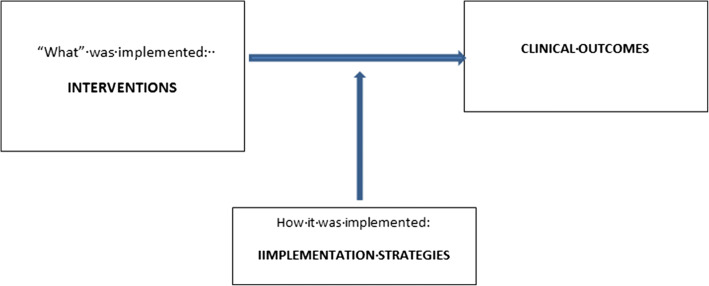

Figure 1.

Conceptual model to address heterogeneity of interventions targeting CKD management.

Through the integration of these frameworks, we identify CCM defined categories of clinician-facing BP management and other CKD interventions to compare, at the same time reviewing implementation strategies used with these interventions. We identified patterns among the most successful interventions by summary through tabulation methods. Narrative analyses were conducted by noting the studies with intervention success, defined in terms of magnitude of effect on BP outcomes. We thematically analyzed features of successful studies.

Since this was a review targeting clinicians, clinicians were actively involved in the conceptualization, literature search, data abstraction, analysis, and interpretation of findings.

Search Methods for Identification of Studies

We searched PubMed, EBSCO, CINAHL, Scopus, Ovid Medline, Ovid Cochrane Library, Ovid EMBASE, Ovid PsycINFO, and Web of Science with the help of an experienced librarian (PJE). The search strategy used is included in Supplement 1 Limiting our attention to a period relevant to contemporary clinical guidelines and scientific evidence, we focused on published reports from 2000 to October 2017. We built our search results off Tsang et al.27 from 2000 till 2014; their literature search was identical to ours. We updated their list with the search for published reports from 2014 to October 2017. As implementation interventions that promote the adoption and integration of evidence-based practices are closely related to the fields of quality improvement and improvement science, we included search terms associated with these fields. We reference mined and hand searched all studies included in full-text reviews, relevant systematic reviews, related publications, and published and unpublished studies from clinical registries and Clinicaltrials.gov.

Selection

Search results were downloaded into EndNote (version 8). Two reviewers (CCK and BT) identified studies for full-text review based on the abstract and title with any studies with disagreement undergoing full-text review. After sharing inclusion and exclusion criteria and the review objectives, reviewers (CCK, BT, MAL, and JM), who were not blinded to author/institution reviewed full-text versions of eligible studies. Eligibility at both the abstract and full-text level was assessed in duplicate and independently. Disagreements were resolved by consensus; in the absence of consensus, a third reviewer (CCK or BT) arbitrated. We calculated Cohen’s kappa28 to assess level of agreement between reviewers.

Data Collection

Clinicians (BT, ME, CCD, RGM, and JM) defined a categorized list of relevant clinical outcomes for extraction (see Table 3). After pilot testing an abstraction form in Excel (Supplement 2 material) and a brief orientation of review objectives, reviewers (CCK, BT, MAL, CCD, RGM, and JM) abstracted data. We extracted data on characteristics of study participants, study design, details of interventions and controls, implementation strategies (identified and categorized according to the ERIC framework29, 30), outcome measures (see Table 3), and study quality factors. Discrepancies in abstracted data were adjudicated by consensus.

Clinicians (RGM, CCD, AP, JD, JM, MYE, and BT) abstracted pre-specified clinical outcomes. To classify the study populations we used the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD classification.29 Implementation science researchers (CCK and MAL) dissected and abstracted details on interventions and implementation strategies. The lead author (CCK) oversaw integration of the two separate abstraction efforts. Authors of the primary studies were contacted for clarification of missing or unclear data. Using Proctor et al.’s framework,24 we categorized interventions (“what” implemented) with guidance from the CCM,22, 23 and implementation strategies (“how” implemented), with the ERIC framework.25, 26

Methodological Quality and Certainty in the Evidence

We used the Cochrane Collaboration’s risk of bias tool30 to evaluate the methodological quality of included RCTs. For NRS, we adapted the New Castle Ottawa instrument to assess risk of bias.18 These evaluations were conducted at the study level. The certainty in evidence (confidence in the effect) was evaluated using adaptations of GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation) for complex interventions.31

Data Synthesis

In order to triangulate findings across studies, we adopted a dual analyses strategy, one narrative and the second, a meta-analysis on BP outcomes, the most prevalent endpoint across included studies. The narrative synthesis utilized a conceptual framework described above. Meta-analysis of BP outcomes is described as follows.

For RCTs, we compared the difference between the intervention and control groups on achievement of BP targets and reduction in systolic BP. We calculated the odds ratios (OR) for number of patients achieving target BP and weighted mean difference (WMD) for systolic BP levels using the Cochrane handbook (https://handbook-5-1.cochrane.org/). To summarize the totality of the evidence from both RCTs and NRS, we also calculated proportionate change in BP target achievement before and after the interventions in the intervention groups of included studies. The DerSimonian and Laird random effects method32 was used to pool the effect size across study types (i.e., OR and WMD) from included studies. Planned subgroup analyses were performed by (1) study design (RCT or NRS), (2) intervention type (guideline-concordant decision support, shared care, pharmacist-facing), and (3) use of behavioral/implementation theory. We used I2 indicator to evaluate heterogeneity across the included studies, in which > 50% suggests substantial heterogeneity.30 Stata version 15.1 was used to conduct the analyses.11

RESULTS

Study Selection

Our initial search for 2015–2017 identified 3444 records (Fig. 2). After removing 741 duplicates and reviewing 2704 titles/abstracts, we identified 48 studies for full review. We identified 10 trials from Clinicaltrials.gov, two of which met our inclusion criteria; results of both are pending and not available. After adding 24 studies from Tsang et al.27 and 5 identified by reference mining we reviewed in full 73 manuscripts; 28 were included with 88.7% agreement (Cohen’s k 0.77). During data abstraction, we eliminated 6 because they did not separate out the results for primary care setting33, 34 or inappropriate outcomes19, 35; two reports36, 37 were redundant as data from these were included in a subsequent comprehensive publication.38 This yielded a total of 22 studies for review.

Study Characteristics

Included studies are summarized in Table 1. Twelve studies were RCTs, while the rest were NRS (cohort or before-after studies). One study38 presented results of four independent, non-overlapping 1-year phases of a multifaceted collaborative QI strategy examining independent cohorts of patients, which were treated as four separate studies for meta-analysis. The studies enrolled patients, ranging from 45 to 121,362 each. Studies were limited to practices in the industrialized world; one was in an underserved area.43 Most studies focused on CKD stages 3–5; two included stages 1–2 with proteinuria50, 59 and three also included patients with uncontrolled BP at high risk for developing CKD.14, 51, 52 Most studies included all adult patients while two studies40, 54 were limited to elderly patients; two42, 47 also presented data on a subgroup of elderly patients. Only five studies39, 41, 43, 51, 53 reported on minority patients (range 5–50%) with percentage ranging from 5 to over 50%. All studies included patients of both sexes.

Table 1.

Description of Included Studies

| Study authors Year Setting |

Number of patients (% female) % black/minorities Age (SD/IQR) CKD stage Study design (duration months) |

Intervention name and brief description Target of intervention Use of implementation framework or behavioral theory |

ERIC implementation strategies abstracted from publication (organized by concept mapped cluster defined by Waltz et al. 2015) | Primary outcome (measure) and/or BP outcomes (measure) Secondary outcomes |

Effect size on primary outcome or BP outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Guideline-concordant decision support interventions | |||||

|

Abdel-Kader, K. et al. 201139 Academic outpatient practice, USA |

248 (62.9%) 37.5% black Age 65.2 (14) Stages 3b–5 Cluster RCT (12 months) |

Clinical decision support system (real time automated electronic alert) and education meetings; educational sessions + electronic alert 30 primary care physicians No |

Train and educate stakeholders •Conduct educational meetings Support clinicians •Facilitate relay of clinical data to providers •Remind clinicians |

Nephrology referral (referral order to nephrologist) BP management (odds of Achieving target BP < 130/80) Lab management Medication management Patient identification |

9.7% (intervention arm) vs. 16.5% (control arm) NS OR of achieving target BP = 2.07 (CI 0.8–5.17) NS |

|

Akbari, A. et al. 200440 Academic family medicine outpatient practice, Canada |

324 (56.2%) 76.2 years (6.3) Stages 2–5 Before-after (12 months) 12 months |

Automatic lab reporting of eGFR and Educational program (two 1-h didactic teaching seminars and facilitation visits, academic detailing, post education support) Primary care physicians No |

Train and educate stakeholders •Conduct educational meetings •Develop educational materials •Distribute educational materials •Provide ongoing consultation Support clinicians •Facilitate relay of clinical data to providers Provide interactive assistance •Facilitation |

Patient identification (% of patients with GFR < 78 with CKD documented) (% of patients with GFR < 60 with CKD documented) Disease progression |

For patients with GFR < 78, pre-intervention 22.4% versus post-intervention 85.1% recognized* For patients with GFR < 60, pre-intervention 13.9% versus, post-intervention 69.3% recognized* |

|

Drawz, P. E. et al. 201241 Primary care VA outpatient clinics, USA |

781 (4.7%) 45.5% black Age 71.0 (10.3) Stages 3–5 + chronicity Cluster RCT (12 months) |

Chronic kidney disease registry and provider education (plus education lecture given daily for a week at start of study, academic detailing) and access to CKD registry PCPs No |

Train and educate stakeholders •Conduct educational meetings •Conduct educational outreach visits Support clinicians •Facilitate relay of clinical data to providers |

Lab monitoring (odds of having measurement of PTH in intervention vs control clinic)) BP management (odds of achieving BP target < 130/80) Medication management |

Adjusted OR = 1.53; (1.01, 2.30)* Adjusted OR = 1.15 (0.86,1.53) NS |

|

Erler, A. M. et al. 201242 46 small primary care practices, Germany |

404 (63%) Age 80.4 (7.2) Stages 3b–5 and elderly patients with hypertension Cluster RCT (6 months) |

DOSING + an educational intervention Physician education on detection and management of CKD, checklist of medications to be reduced/avoided for CKD patients + software program support in form of database on fractional renal excretion, monthly reminders to use the program PCPs No |

Train and educate stakeholders •Make training dynamic •Distribute educational material •Conduct educational meetings Support clinicians •Remind clinicians •Facilitate relay of clinical data to providers |

Medication management (% of patients receiving ≥ 1 prescriptions exceeding the recommended max daily dose) (% of patients receiving prescriptions exceeding the standard daily dosage by > 30%) (% with contraindicated or potentially dangerous meds (metformin, nitrofurantoin, allopurinol)) |

Decrease in prescriptions exceeding max daily dosage: OR 0.46 (CI 0.26, 0.82)* Decrease in prescriptions > 30% over standard daily dosage: OR 0.66 (CI 0.36, 1.21) NS Decrease in contraindicated meds 18% in treatment arm vs 1% in control arm NR |

|

Fox, C. H. et al. 200843 2 primary care practices in underserved area, USA |

181 patients (NR) 67.5% black Age NR Stages 3–5 Before-after QI (12) |

Multifaceted QI intervention using practice facilitation to promote uptake of KDOQI: Practice facilitation (including building relationships, facilitating change, implementing national guidelines, and sharing best practices), Computer decision support, Academic detailing Clinicians Yes: practice facilitation |

Train and educate stakeholders •Conduct educational outreach visits Support clinicians •Facilitate relay of clinical data to providers •Remind clinicians Provide interactive assistance •Facilitation Adapt and tailor to context •Use data warehousing techniques Use evaluation and iterative strategies •Audit and provide feedback •Assess for readiness and identify barriers and facilitators Change infrastructure •Change accreditation or membership requirements |

Patient identification (Number with CKD diagnosis) Medication management Laboratory management Disease progression Anemia diagnosis |

Pre-intervention of 30 (21%) to post-intervention of 114 (79%)* |

|

Humphreys, J. et al. 201738 |

Number of patients in Project 1: 4185 Project 2: 2055 Project 3: 1871 Project 4: 665 (female % NR) KDIGO stages 3–5 Before-after (12) |

Staged improvement collaborative to promote uptake of CKD management guidelines in primary care practices Projects 1 and 2: Learning events, improvement targets, PDSA cycles, benchmarking of audit data, tailored facilitated support and staff time reimbursement. Besides the above QI process, multidisciplinary teams and an embedded approach to evaluation and learning to ensure ongoing reflection and refinement of improvement program. IMPAKT a data extraction and audit tool (IMproving Patient care and Awareness of Kidney disease progression Together) Projects 3 and 4: Mostly similar interventions as in projects 1 and 2 (with less financial incentives, but greater feedback and learning from earlier Projects). Physicians Yes: Model for improvement PARIHs—an evidence-based implementation framework Quality and outcomes framework |

Train and educate stakeholders •Create a learning collaborative •Conduct educational outreach visits Provide interactive assistance •Facilitation •Centralize technical assistance Adapt and tailor to context •Promote adaptability Use evaluation and iterative strategies •Conduct local needs assessment •Develop a formal implementation blueprint •Conduct cyclical small tests of change •Assess for readiness and identify barriers and facilitators •Audit and provide feedback •Stage implementation scale up Utilize financial strategies •Alter incentive/allowance structures—projects 1 and 2 only •Fund and contract for the clinical innovation Develop stakeholder interrelationships •Identify and prepare champions •Capture and share local knowledge |

Patient identification (Change in CKD Prevalence: % of CKD patients on practice registries) BP management (% achieving proteinuric and nonproteinuric targets post QI vs. overall CKD patients) |

Project 1: Relative increase of 38% (3.6 to 5.0) in tx practices vs 22% (3.7 to 4.5) in control practices. NR Project 2: Relative increase of 26% (4.6 to 5.8) in tx practices vs 5% (4.4 to 4.6) in control practices. NR Project 3: Relative increase of 38% (3.6 to 5.0) in tx practices vs 22% (3.7 to 4.5) in control practices. NR Project 4: Relative increase of 15% (5.2 to 6.0) in tx practices vs − 4% (5.5 to 5.3) in control practices. NR Project 1: % achieving 140/90 mmHg: 88%; 130/80 mmHg: 69% vs. all CKD patients: 74%. NR Project 2: % achieving 140/90 mmHg: 90%; 130/80 mmHg: 83% vs. all CKD patients: 46%. NR Project 3: % achieving 140/90 mmHg: 89%; 130/80 mmHg: 71% vs. all CKD patients: 48%. NR Project 4: % achieving 140/90 mmHg: 92% ; 130/80 mmHg: 76% vs. all CKD patients: 45%. NR |

|

Karunaratne, K. et al. 201344 Primary care, UK |

10,040 (55%) 74.7 years (NR) KDIGO stages 3–5 CKD Before-after (48) |

p4p indicators in the quality and outcomes framework for CKD guideline implementation Physicians Yes: Pay for performance Quality outcomes framework |

Use evaluation and iterative strategies •Develop and organize quality monitoring systems Utilize financial strategies •Alter incentive/allowance structures |

BP management (% all CKD patients achieving BP targets: 145/80) (% HTN patients achieving BP targets) (Mean BP) Medication management |

Between pre and post-QOF period, % of all CKD patients increased 41.5 to 50.0%. NR Between pre- and post-QOF period % of HTN patients increased 28.8–45.1%. NR Mean BP for all patients between periods 1 and 2 (143/78 to 140/76)*; between periods 2 and 3 (138/75)* Mean BP for HTN patients between periods 2 and 3 (146/79 to 140/76)* and between periods 2 and 3 (139/75)* |

|

Litvin, C. B. et al. 201645 11 primary care PPRNet practices, USA |

No data on number of patients, only number of practices (11), physicians (25), and mid-level providers (15). CKD 3–5 Before-after (24) |

Two year demonstration project to demonstrate effectiveness of clinical decision support (CDS) to improve identification and management of CKD in primary care. CDS included a risk assessment tool, health maintenance protocols, flowchart, and patient registry. Clinicians No |

Train and educate stakeholders •Conduct educational outreach visits Support clinicians •Remind clinicians •Facilitate relay of clinical data to providers Provide interactive assistance •Facilitation Adapt and tailor to context •Promote adaptability Use evaluation and iterative strategies •Audit and provide feedback •Conduct cyclical small tests of change |

Patient identification (Albuminuria screening) (Albuminuria monitoring) BP management (% BP < 140/90 CKD without proteinuria) (% BP < 130/80 CKD with proteinuria) Lab monitoring Medication management |

Increases in albuminuria screening by 30%*and monitoring albuminuria by 25%* % change for patients without proteinuria; 2.5 (CI 0.0,7.0) NS % change for patients with proteinuria; − 1.5(CI − 50.5, 9.0) NS |

|

Lusignan, S. et al. 201346 93 general primary care practices, UK |

23,311 (66.6%) Overall 75.1 (11.9) KDIGO stages 3–5 Cluster RCT (24) |

Audit-based education intervention as part of QICKD (quality improvement in CKD). A complex nonjudgmental educational intervention which provides education and peer support and documents the gap between achievement and guidelines. Clinicians Yes: Control theory |

Train and educate stakeholders •Conduct educational outreach visits •Distribute educational materials •Conduct educational meetings Support clinicians •Facilitate relay of clinical data to providers Use evaluation and iterative strategies •Audit and provide feedback •Develop and organize quality monitoring systems Provide interactive assistance •Centralize technical assistance Develop stakeholder interrelationships •Use an implementation advisor |

BP management (Odds of achieving BP target—at least 5 mmHg reduction in SBP) Medication management Mortality Onset of CV disease |

Audit-based education vs control: SBP decreased by 2.41 mmHg (CI 0.59–4.29 mmHg)* OR of achieving > 5 mmHg reduction in SBP vs. control 1.24 (CI 1.05–1.45)* Guidelines and prompts vs. control produced no significant change |

|

Manns, B. et al. 201247 93 primary care practices, Alberta, CA |

22,092 (63.7) Age 72.2 (12.5) 5444 (55.2%) elderly w DM or proteinuria Age 78.2 (7) Stages 3–5 Cluster RCT (25) |

Enhanced eGFR laboratory prompt (additional education about significance of CKD, specific management recommendations, including those based on guidelines to monitor and measure different lab values) 420 primary care physicians No |

Train and educate stakeholders •Distribute educational materials Support clinicians •Remind clinicians |

Medication management (Prescriptions for % w ACEi/ARB medication in all patients) (Prescriptions for % w ACEi/ARB medication in elderly patients with an eGFR < 30 ml/min per 1.73 m2 Patient identification Lab monitoring Nephrology referral |

ACEi/ARB use post-treatment was 77.1% and 76.9% in the standard and enhanced prompt groups, respectively. NS In the subgroup of elderly patients with an eGFR < 30 ml/min per 1.73 m2, ACEi/ARB use was higher in the enhanced prompt group. NS |

|

Stoves, J. 201048 Primary care, UK |

466 patients (NR) Age 72.1 (NR) Stage NR Any CKD referrals Comparative before-after (12) |

E-consults for CKD (instead of actual hospital referrals) Clinicians No |

Train and educate stakeholders •Conduct educational meetings •Distribute educational materials Support clinicians •Facilitate relay of clinical data to providers Use evaluation and iterative strategies •Stage implementation scale up Change infrastructure •Change record systems |

Nephrology referral (Wait time for referral response) (Rate of referrals between electronic versus paper referrals to nephrologists) (Appropriateness and quality of all referrals, timeliness of responses and follow-up action) |

Time to response was 7 (0.8) days for e-consult vs. 55.1 (1.6) days for paper referral to clinic NR Rate of referrals was approximately 1.25/10,000 population for e-consults versus 1.75/10,000 for paper referrals. NR Appropriateness was 90% vs. 56% for e-consult vs. paper referrals. NR E-consultation provided nephrologists with access to more clinical information. GPs reported that the service was convenient, provided timely and helpful advice, and avoided outpatient referrals. Specialist recommendations were well followed, and GPs felt more confident about managing CKD. |

|

Xu, G. et al. 201749 48 primary care practices, UK |

121,362 (NR) Age (NR) Patients with CKD or uncontrolled hypertension Before-after (18) |

IMPAKT IT study: efficient transmission of information between primary/secondary care, two QI improvement audit using IT resources and multi professional, collaborative teams, RN run protocol Clinicians Yes |

Train and educate stakeholders •Create a learning collaborative •Provide ongoing consultation Support clinicians •Facilitate relay of clinical data to providers Provide interactive assistance •Facilitation Use evaluation and iterative strategies •Audit and provide feedback |

Patient identification (Prevalence of coded CKD between visits 1, 2, and 3) BP management (Paired difference in % with BP measurement between visits 1, 2, and 3) (Paired difference % meeting BP management targets between visits 1, 2, and 3) |

Significant increase in % coded CKD 4.79* to 4.98 NS to 4.89 NS respectively. Decrease in uncoded CKD from 4.69* to 4.45 NS and 4.45 NS respectively. Paired difference in % of patients with BP recorded 91.78 NS to 91.36* to 93.37 NS Paired difference in % achieving BP targets.49.43* to 54.55 NS to 53.93 NS |

| Pharmacy-facing | |||||

|

Al Hamarneh, Y. N. et al. 201750 56 community pharmacies Community setting, Canada |

290 (54.8%) 61.2 (12.1) Stages 3–5 or proteinuria RCT (3 months) |

RxEACH Trial (subgroup analysis) Community pharmacy-based intervention program (on line pharmacist training program), face-face regional meetings. Training included modules on case finding risk calculation and management, documentation of care plans for remuneration. Intervention also included medication therapy management of patients, pharmacy consults, pharmacists-physician communication regular f/u visits with patient. Pharmacists No |

Train and educate stakeholders •Develop educational materials •Conduct educational meetings Support clinicians •Facilitate relay of clinical data to providers •Revise professional roles Engage consumers •Intervene with patients/consumers to enhance uptake and adherence |

Change CV risk (Change in estimated CV risk) BP management (Change in SBP) Change in ESRD risk (Change in estimated 5 years ESRD risk) Diabetes management Lipid management Medication management |

RRR of 20% for CV risk* Difference in differences between treatment and control group: 10.5 mmHg in SBP* RRR of 27% for ESRD risk NS |

|

Carter, B. L. et al. 201551 Multi-state primary care, USA |

625 (40.3%) Minority 54% Black 38.2% Stages 3–5 Uncontrolled hypertension Age 61.8 (13.7) Pragmatic RCT (36) |

Physician/pharmacist collaboration (CAPTION). Medical record review and information intake by pharmacist from patients. Care plan developed by pharmacists including recommendation, communicated with primary care physician 9 months (brief intervention) 24 months (sustained intervention) Pharmacists Yes: Theory of planned behavior |

Train and educate stakeholders •Provide ongoing consultation •Conduct educational meetings Support clinicians •Facilitate relay of clinical data to providers •Create new clinical teams Engage consumers •Intervene with patients/consumers to enhance uptake and adherence |

BP management (% achieving BP goal < 140/90 for uncomplicated HTN) (% achieving BP goal < 130/80 for DM/CKD) (Adjusted mean difference in SBP and DBP for all patients) (Adjusted mean difference in SBP and DBP for minority patients) |

48% vs 40%; Adjusted OR 0.93 [0.48–1.8] for uncomplicated HTN NS 38% vs 24% Adjusted OR 2.16 [1.08–4.33]* for DM/CKD patients. Adjusted mean difference—all patients: SBP/DBP : − 6.1*/− 2.9 mmHg* Adjusted mean difference—minorities: SBP/DBP: − 6.4*/− 2.9 mmHg* |

|

Chang, A.R. et al. 201652 Six primary care sites within a health system, USA |

47 patients (57.4%) Age 67.2 (10) Stage 3a eGFR 45–59 Uncontrolled BP (> 150/80) Pragmatic cluster RCT (18) |

Pharmacist medication therapy management (MTM) + usual care training for pharmacists (hypertension management education + KDIGO guideline adherence education). Pharmacists were allowed to prescribe and titrate medications. Pharmacists No |

Train and educate stakeholders •Conduct educational meetings •Provide ongoing consultation •Conduct ongoing training Support clinicians •Create new clinical teams •Revise professional roles Engage consumers •Intervene with patients/consumers to enhance uptake and adherence |

Lab monitoring (% screened for proteinuria or protein/creatinine ratio for all patient and previously unscreened patients) BP management (Achievement of BP goals) Medication management |

Proteinuria screening at the population level (OR 2.6; 95% CI 0.5–14.0) NS Proteinuria screening for previously unscreened patients OR 7.3; 95% CI 0.96–56.3)* Achievement of BP goal (OR 0.9; 0.3–3.0) NS |

|

Cooney, D. H. et al. 201553 Primary care, USA (VA setting) |

2199 (1.5%) Black 5.4% 75.7 years (8.2) KDIGO CKD 3b–5 Pragmatic cluster RCT (12 months) |

Pharmacist based QI program (+ lecture on KDOQI guidelines), delivery system redesign (pharmacists interact more with PCPs and patients), self-management support for patients and EMR based CKD registry Pharmacists No |

Train and educate stakeholders •Distribute educational materials •Conduct educational meetings Support clinicians •Facilitate relay of clinical data to providers •Revise professional roles Engage consumers •Intervene with patients/consumers to enhance uptake and adherence |

BP management (Decrease in mean SBP) (% at goal BP) Laboratory monitoring Mortality Quality of life Medication management Patient identification Nephrology referral |

SBP: 134.4 vs. 152.1 NS % at goal BP: 42.0% vs. 41.2% NS |

|

Via-Sosa, M. A. et al. 201354 40 Spanish community pharmacies, Spain |

354 (64%) Age 82.1 (7.1)) CKD 3–5 Before-after (3 months) |

Educational intervention to improve drug dosing service by community pharmacies Structured method for pharmacy communication with PCP Clinicians No |

Support clinicians •Facilitate relay of clinical data to providers •Revise professional roles |

Medication management (Prevalence of drug dosing inadequacy) (Mean of drug-related problems or appropriateness) |

Pre-intervention between group difference in the prevalence of dosing inadequacy: 0.73% [95% CI (− 6.0, − 7.5] NS Post-intervention between group difference in the prevalence of dosing inadequacy 13.5% [95% CI 8.0–19.5]* Pre-intervention difference in the mean drug-related problems per patient 0.05 [95% CI (− 0.2)–0.3] Post-intervention difference: 0.5 [95% CI 0.3–0.7]* |

| Shared care interventions | |||||

|

Barrett, B. J. et al. 201155 Primary care, Canada |

474 (55%) 71 (40,75) Stages 3–4 RCT (36 months) |

Nurse-coordinated model of care with access to neurologist consults, nurse followed medical protocols and worked in close collaboration with a nephrologist. Nurses No |

Support clinicians •Revise professional roles •Create new clinical teams Provide interactive assistance •Provide clinical supervision Engage consumers •Prepare patients/consumers to be active participants |

BP management (% on target BP < 130/80 mmHg) Medication management Disease progression Diabetes control CV outcomes |

Difference in BP target at 12 months (61.5% vs. 45.9%) NS Difference in BP target at 24 months (63.2% vs. 47%) NS |

|

Richards, N. et al. 200856 Primary care, UK |

483 (53%) 77.1 (NR) Stages 4 and 5 (some high 3b) Before-after (12 months) |

Algorithm-based primary care disease management program based on automated diagnosis using eGFR reporting. The DMP was delivered by a community-based team of nurses, dietician, and social worker. The four main facets of program included patient education, medicine management, dietetic advice, and optimization to achieve clinical targets. Clinicians and patients Yes |

Support Clinicians •Create new clinical teams Use evaluation and iterative strategies •Audit and provide feedback Engage consumers •Prepare patients/consumers to be active participants |

Lipid management (% achieving target for total cholesterol, HDL, LDL, triglycerides—9 months vs. 0 month)) BP management (% on target for SBP and DBP: 130/80 respectively for patient without DM or proteinuria (% on target for SBP and DBP 120/75 respectively for patients with DM and/or proteinuria) Disease progression |

Cholesterol (< 5 mmol/l): 75% vs 64.5%* HDL (> 1.2 mmol/l) 43.8% vs. 59.4%. NS LDL (< 3 mmol/l): 82.0 vs. 69.1%* Triglycerides (< 2 mmol/l): 56.3% vs. 65%. NS SBP (target—130/80): 53.2% vs 37.1%* DBP (target—130/80): 90.3% vs. 68.4%* SBP (target—120/75): 24.1% vs 18.8%. NS DBP (target—120/75): 55.2% vs. 52.8%. NS |

|

Scherpbier-de Haan, N. D. et al. 201357 9 primary care practices, Netherlands |

165 (55.8%) Age 73.1 (8.1) Stage 3–5 Cluster RCT (12 months) |

Shared care model where nurse practitioner played a central role and a nephrologist and a nephrology nurse could be consulted Clinicians and patients No |

Train and educate stakeholders •Provide ongoing consultation •Distribute educational materials •Conduct educational meetings Support clinicians •Create new clinical teams |

BP management (% meeting BP target of 130/80) (Change in SBP) (Change in DBP) Medication management Diabetes management Lipid management Nephrology referral Functional status Smoking status |

% meeting SBP target: 44.4% vs. 21.6%; OR = 2.9 (95% CI 1.4 to5.8)* % meeting DBP target: 71.1%% vs. 50%; OR = 2.5 (95% CI 1.3 to 4.7)* Change in SBP: − 8.1(4.8–11.3) Tx group compared to − 0.2 (95% CI = − 3.8 to 3.3) control group. NS Lowering of DBP − 1.1 (95% CI = − 1.0 to 3.2) Tx group compared to − 0.5 (95% CI = − 2.9 to 1.8) control group. NS |

|

Thomas, N. et al. 201458 29 GP primary care in England and Wales, UK |

No information on number of patients Stages 3–5 CKD Before-after study (NR) |

Care bundle for CKD: three evidence-based interventions (group education of patients, training of providers and patient involvement) Providers and patients No |

Train and educate stakeholders •Conduct educational meetings Provide interactive assistance •Facilitation Adapt and tailor to context •Promote adaptability Use evaluation and iterative strategies •Obtain and use patients/consumers and family feedback •Stage implementation scale up •Conduct cyclical small tests of change •Audit and provide feedback Engage consumers •Involve patients/consumers and family members •Prepare patients/consumers to be active participants |

Patient identification (Recorded prevalence of CKD) BP management (Proportion of patients treated to NICE targets for BP control < 140/90 mmHg for patients without DM or proteinuria) (Proportion of patients treated to NICE targets for BP control < 130/80 mmHg if patient had DM and/or proteinuria (ACR > 70) |

Overall prevalence increased from 4% (± 1.54 %) to 4.9% (± 1.62%) NR BP target achievement increased from 61.4 to 62.8% and from 74.8 to 76.7% for patients with CKD and DM. NR BP target achievement increased from 48 to 49.2% for patients without CKD and DM. NR |

|

Yamagata, K. et al. 201659 Primary care, Japan |

2379 (28.1%) Age 63.0 years (8.4) Stages 3–5 and stages 1–2 with proteinuria Cluster RCT (42 months) |

Multidimensional behavior modification intervention targeted at clinicians and patients: clinicians received guidelines and audit and feedback through data sheets; patients receive education regarding lifestyle modification Clinicians and patients No |

Train and educate stakeholders •Conduct ongoing training •Distribute educational materials Support clinicians •Facilitate relay of clinical data to providers Use evaluation and iterative strategies •Audit and provide feedback Engage consumers •Intervene with patients/consumers to enhance uptake and adherence •Prepare patients/consumers to be active participants |

Patient adherence (Discontinuous visits defined as > 6 months of no visit) BP management (% achieving BP targets) Nephrology referral Disease progression Guideline adherence |

Rate of discontinuous visits: 16.2% in group A (weak intervention) versus 11.2% in group B (strong intervention)* % achieving BP targets: 82.4% (group A) vs. 84.6% (group B) NS |

ACE - ace inhibitor, ARB - angiotensin receptor blocker, ACR - albumin-creatinine ratio , BP – Blood Pressure, CKD – chronic kidney disease, CV – Cardiovascular, ESRD – End Stage Renal Disease, ESKD – end stage kidney disease, DM - Diabetes mellitus, HbA1c -hemoglobin A1c, HTN - Hypertension, SBP systolic BP, DBP diastolic BP, LDL - low density lipoprotein, HDL - high density lipoprotein, OR - odds ratio, RR - relative risk, RRR - relative risk reduction

* = p value < 0.05; N/A non applicable; NS Not significant, NR Significance not reported, Lab = laboratory monitoring; Meds = medications. BP values are reported as mmHg; Laboratory values are reported as mmol/l unless otherwise specified

Study clinical outcomes (see Table 3) are described in Table 1. Reported clinical outcomes varied across studies; most studies reported more than one outcome. BP goal attainment and/or reduction in systolic/diastolic BP, were the most frequent,20, 23–25, 27–30, 45, 46, 49, 56–58, 60 followed by patient identification for CKD. Fifteen studies included medication management most often focused on prescription of ACE/ARB-inhibitor prescriptions or avoidance of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, eight studies included patient identification for CKD, seven studies, laboratory monitoring of CKD, and targets in diabetes and lipid management were reported in 3 and 2 studies respectively.

Risk of Bias in Studies

Most studies had areas with high risk of bias due to lack of blinding (Table 2). Overall, the RCTs were less biased than NRS as expected.

Table 2.

Risk of Bias Table

| Randomized controlled trials Study authors and year |

Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Blinding of participant and personnel (performance bias) | Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Selective outcome reporting (reporting bias) | Other sources of bias | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abdel-Kader, K. et al. 201139 | Low | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | |

| Al Harmaneh, Y. N. et al., 201750 | Low | Low | High | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | |

| Barrett, B. J. et al., 201155 | Low | Low | High | High | Low | Low | Low | |

| Carter, B. L. et al, 201551 | Unclear | Unclear | High | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | |

| Chang, A. R. et al., 201652 | Low | Unclear | High | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | |

| Cooney, D. H. et al.,201553 | Low | Low | High | Low | Low | Low | Low | |

| Drawz, P. E. et al., 201241 | Low | High | High | Low | Low | Low | Low | |

| Erler, A. M. et al., 201242 | High | High | Low | High | Unclear | Unclear | Low | |

| Lusignana, S. et al., 201346 | Low | Unclear | High | Low | Low | Low | Low | |

| Manns, B. et al, 201247 | High | High | High | Low | Low | Low | Low | |

| Scherpbier-de Haan, N. D. et al., 201357 | High | Low | High | Low | Low | Low | Low | |

| Yamagata, K. et al., 201659 | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | High | Unclear | |

|

Nonrandomized studies (NRS) Study authors and year |

Representativeness of cohort | Selection of non-exposed cohort | Ascertainment of exposure | Demonstration that outcome of interest was not present at start of the study | Comparability of cohort on the basis of design or analysis | Assessment of outcomes | Was follow-up long enough for outcomes to occur? | Adequacy of follow-up |

| Akbari, A. et al.200440 | Truly representative | Not applicable | Secure record | Yes | Not applicable | Standard procedure well described | Yes | Complete follow-up—all subjects accounted for |

| Fox, C. H. et al., 200843 | Truly representative | Not applicable | Secure record | Yes | Not applicable | Standard procedure well described | Yes | Subjects lost to follow-up unlikely to introduce bias, small number lost, > 80% follow-up/descr of those lost |

| Humphreys, J. et al., 201738 | Truly representative | Not applicable | Secure record | Yes | Not applicable- | Standard procedure well described | Yes | Subjects lost to follow-up unlikely to introduce bias, small number lost, > 80% follow-up/descr of those lost |

| Karunaratne, K. et al., 201344 | Somewhat representative | Not applicable | Secure record | Yes | Not applicable | No description | Yes | Subjects lost to follow-up unlikely to introduce bias, small number lost, > 80% follow-up/descr of those lost |

| Litvin, C. B. et al., 201645 | Somewhat representative | Not applicable | Secure record | Yes | Not applicable | Record linkage | Yes | F/U rate < 80% and no description of those lost |

| Richards, N. et al., 200856 | Somewhat representative | Not applicable | Secure record | Yes | Not applicable | Standard procedure well described | Yes | Subjects lost to follow-up unlikely to introduce bias, small number lost, > 80% follow-up/descr of those lost |

| Stoves, J., 201048 | Somewhat representative | Not available | Structured interview | Yes |

By design Not available |

Self-report | No | Complete follow-up—all subjects accounted for |

| Thomas, N. et al., 201458 | Somewhat representative | Not applicable | Secure record | Yes | Not applicable | Standard procedure well described | Yes | F/U rate < 80% and no description of those lost |

| Via-Sosa, M. A. et al., 201354 | Somewhat representative | Not available | Secure record | Yes | Study controls for other important factors | Record linkage | Yes | Complete follow-up—all subjects accounted for |

| Xu, G. et al., 201749 | No description of derivation of cohort | Not applicable | No description | Yes | Not applicable | No description | Yes | F/U rate < 80% and no description of those lost |

Clinical Interventions: “What” Was Implemented?

Table 1 includes a brief description of specific interventions used in each study, grouped into three categories: (1) guideline-concordant decision support through electronic prompts or managing/tracking CKD patient registries to identify and manage CKD,38–49 (2) pharmacist-facing interventions50–54 to manage CKD in primary care, and (3) shared care interventions to manage CKD55–59 involving multidisciplinary care teams (e.g., nurse practitioners) in CKD prevention and management.

Meta-analysis of Effect of Clinical Interventions on Hypertension Outcomes

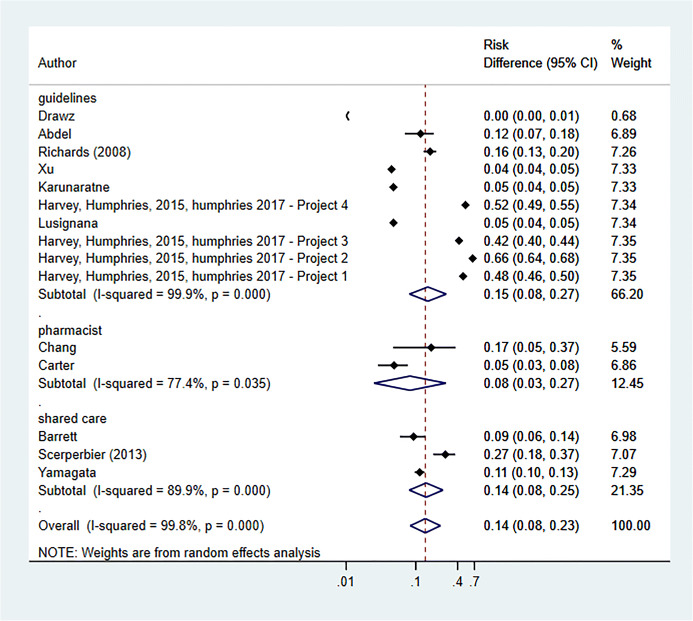

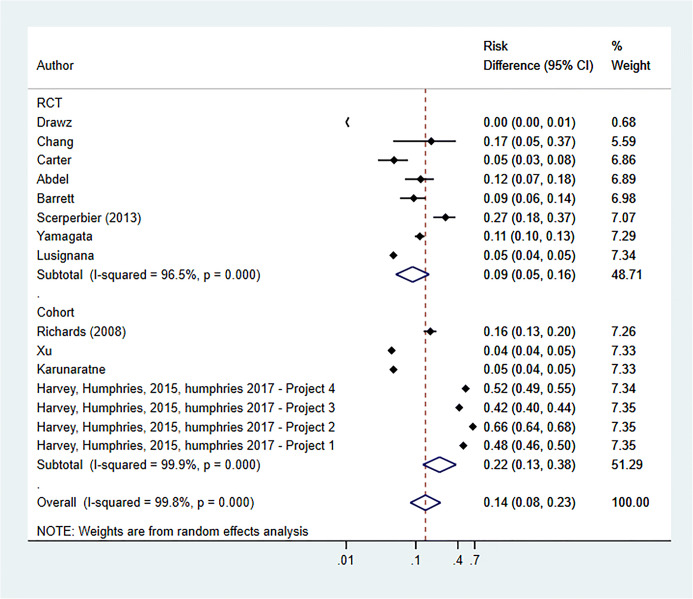

Pooling the results of RCTs and NRS (using the DerSimonian–Laird technique29), the overall effect of clinical interventions on achievement of target BP was significant (proportionate change 0.14; 95% CI 0.08 to 0.23; I2 = 80.6%; p = 0.006). Most benefit was observed with guideline-concordant decision support interventions (proportionate change 0.15; 95% CI 0.08 to 0.27; I2 = 99.9%; p = 0.000) and shared care models (proportionate change 0.14; 95% CI 0.08 to 0.25; I2 = 89.9%; p = 0.000), but heterogeneity was high (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Meta-analysis of CKD interventions on BP target achievement (only RCTs).

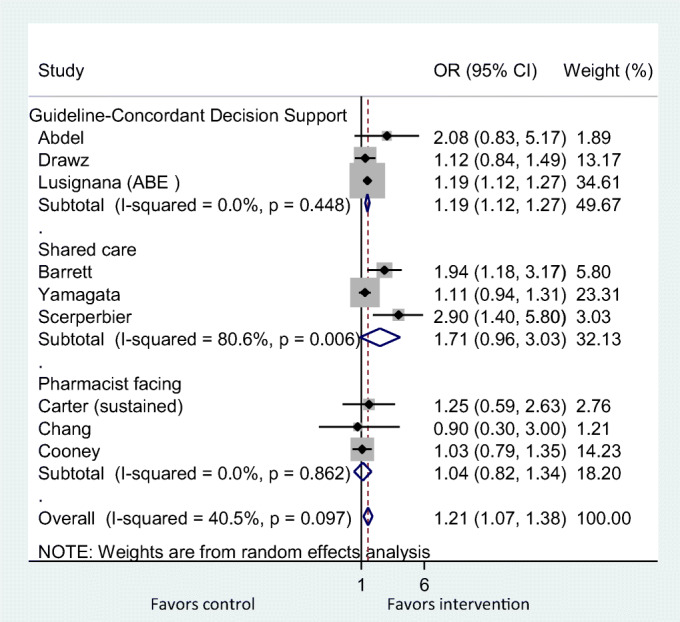

The nine contributing RCTs39, 41, 46, 51–53, 55, 57, 59 demonstrated a significant effect of all clinical interventions on the achievement of target BP control, (pooled OR 1.21; 95% CI 1.07 to 1.38; I2 = 40.5%; p = 0.097) (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Meta-analysis of CKD interventions on BP target achievement (RCTs and NRS).

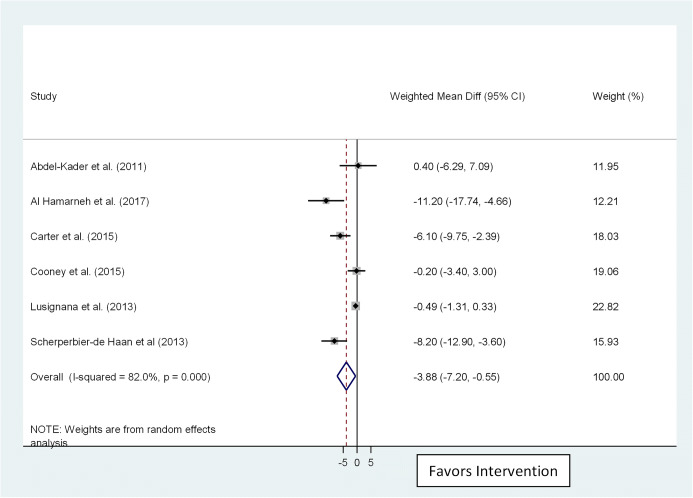

Six studies examined systolic BP reduction, rather than target BP attainment.39, 46, 50, 51, 53, 57 These demonstrated high degree of benefit (pooled WMD − 3.86; 95% CI − 7.2 to − 0.55; I2 = 82.0%; p < 0.001) (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Meta-analysis of CKD interventions on reduction in systolic BP.

Planned subgroup analysis examining for potential differences in intervention efficacy by study design demonstrated a significantly stronger effect size with NRSs (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Impact of study design on BP target achievement (RCTs and NRS).

Due to the small number of included studies (n < 20), and high heterogeneity (I2 ≥ 50%), we determined that evaluation of publication bias (e.g., funnel plots and Egger’s regression test) was not feasible.61

Implementation Strategies: “How” the Clinical Intervention Was Implemented

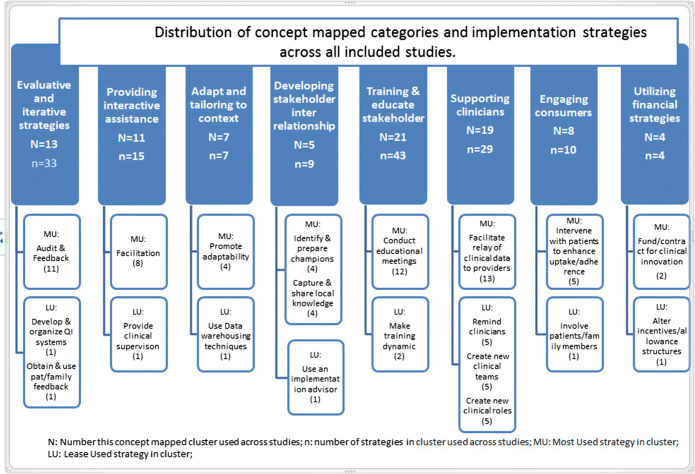

The number of implementation strategies per study, classified using the ERIC framework,25 ranged from 2 to 15 (see Table 1). We summarized the distribution of implementation strategies into concept mapped clusters (see Table 4) reflected in Waltz et al.24 in Figure 7. Most frequently used clusters were “Training and educating stakeholders” (21 studies) and “Supporting clinicians” (19 studies). The least used clusters of strategies were “Developing stakeholder relationships” (5 studies) and “Using financial strategies” (4 studies). Table 1 provides further information on individual strategies under each cluster.

Figure 7.

Distribution of concept mapped categories and implementation strategies across all included studies.

Interventions were paired with implementation strategies in both similar and different ways. All interventions used strategies under “Training and educating stakeholders” and “Supporting clinicians” frequently. Guideline-concordant decision support was often paired with “Evaluative and Iterative Strategies” and “Providing Interactive Assistance.” The four large studies—Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRC)—were exceptional in the use the most number of diverse strategies. Pharmacist-facing interventions and shared care interventions also employed “Evaluative and Iterative strategies,” “Providing Interactive Assistance,” and “Adapting and tailoring to context”; pharmacist-facing interventions used them less frequently that shared care interventions.

Implementation Frameworks: “Why” Interventions and Implementation Strategies Are Likely To Impact Outcomes

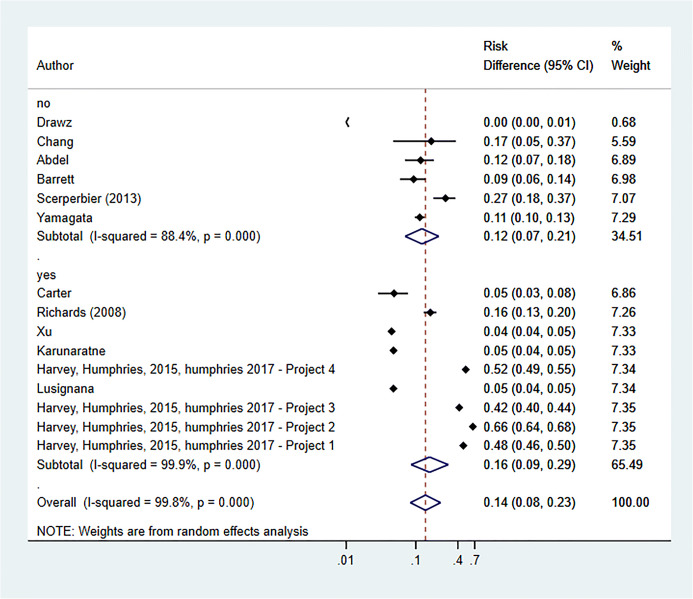

Behavioral and/or implementation theory, intended to guide the research, were mentioned by 738, 43, 44, 46, 49, 51, 56 of the 22 studies. Planned subgroup analysis, based on whether an implementation framework or behavioral theory was used (proportionate change 0.14; 95% CI 0.08 to 0.23; I2 = 99.8%; p = 0.000) or not (proportionate change 0.12; 95% CI 0.07 to 0.21; I2 = 88.4%; p = 0.000), failed to show a difference in effect (Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

Impact of implementation framework on BP target achievement (RCTs and NRS).

DISCUSSION

Summary of Findings

The main purpose of our review was to identify successful CKD management techniques that improve care quality for CKD patients. We found that clinician-facing interventions yielded modest but significant results to control BP, a key factor in halting the progression of CKD. Guideline-concordant decision support interventions demonstrated greater improvements than shared care and pharmacist-facing interventions. The best implementation approach was a combination of guideline-concordant decision support interventions implemented with clinician-directed education and support and more importantly with process intensive, tailored, and stakeholder-engaged strategies to enable adoption of the intervention. Other outcomes measured did not lend themselves to comparative or quantitative analysis because of inadequate numbers and heterogeneity of measures reported.

Certain implementation strategies, like training clinicians and facilitating relay of clinical data were used across all three interventions, while the more process-oriented strategies such as audit and feedback, conducting cyclical small tests of change, facilitation and adaptation to context were used less frequently. While education strategies and infrastructural support, typical change strategies are necessary, they may not suffice for better and sustained clinical outcomes. Process-oriented strategies, albeit personnel resource intensive requiring leadership, additional resources and continued commitment to learning, feedback and necessary adaptation have a better payoff. The lack of implementation outcomes60 (e.g., feasibility, acceptability) in most studies was notable.

The use of theoretical models/frameworks failed to show an impact, possibly due to wrong model choice, model not consistently guiding the study/evaluation or unanticipated/unaccounted confounding contextual factors. However, in at least one instance, where a model, the Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services (PARIHS) implementation framework consistently guided the CLAHRC studies,35 the resulting clinical outcomes were significantly higher than average. These studies also had better reporting of implementation strategies used.

Our finding that NRSs had larger improvements relative to RCTs draws attention to the salience of quasi-experimental studies to study implementation. Most implementation efforts in real-world settings cannot be limited to controlled environments implicit in RCTs. Except for the Lusignana et al.46 RCT, we note a richer diversity of implementation strategies in NRS settings (e.g., Fox,43 Humphreys,38 Litvin, 45 Thomas58). Interventions tested in highly controlled environments may not avail of the impact of tailoring, adaptation, iterative learning, and other natural processes of dissemination and implementation more likely to be present in larger scale, system level studies, likely to be NRS. These processes have been shown to enable implementation (e.g.,62, 63). These benefits of the NRS have to be balanced against the known limitation such as the Hawthorne and placebo effects, and selection and reporting bias on ascertainment of exposure and outcomes assessment.

Complex interventions typically have lower GRADE scores (certainty of evidence) relative to simple interventions because of their inherent heterogeneity and lack of direct applicability.64 Using a modified framework for interpreting GRADE for complex interventions,31 we can differentiate interpretation of GRADE scores based on end-user needs. Thus, from a policy maker’s perspective, where the whole bundle of interventions is of interest, we assessed a moderate GRADE score. However, from a clinician perspective, where interest is on the most effective component of interventions, the high heterogeneity within each category of interventions resulted in a lower assessed GRADE score. Additionally, interventions were not well described to assess applicability to specific settings. Low GRADE scores may be mitigated with high effect sizes,31 relevant to the four CLAHRC studies, increasing the certainty of evidence from these studies: guideline-concordant decision support used with education and infrastructure support for clinicians and process-oriented, contextually adapted implementation.

While other systematic reviews examined similar interventions, we focused our attention on interventions targeting clinicians, influential players who can make a dent in early identification and arresting progress of CKD. We found that implementation strategies that go beyond mere education and support of clinicians are what make some interventions more successful than others. Tsang et al.,27 utilizing a rapid realist review method, echo our findings with their insight that compatibility with existing practices, ownership of feedback processes and individualized, tailored improvements were winning strategies. On the other hand, Galbraith et al.10 found that computer-assisted or education-based CDM interventions were not superior to usual care. Silver et al.12 found that collectively, QI strategies did not have significant effects on BP outcomes. These discrepancies with our review could be due to the larger scope of interventions we examined and our analytic framework to categorize and assess them. Similar reviews in other chronic diseases9, 65, 66 found high heterogeneity across studies, largely due to the variety of implementation strategies used. In addition, tailoring guideline implementation strategies to context, and using more than one strategy, preferably, complementary, seemed to be the common theme across our study and studies in the broader category of management of chronic conditions in primary care. Our study brings to the fore the potential for well-implemented guideline-concordant care for CKD management in primary care through the use of carefully designed implementation interventions.

Strength and Limitations

The strengths of our study include a comprehensive search strategy to identify studies. Clinician stakeholders were engaged throughout the design and conduct of the study, allowing our findings to be relevant and immediately actionable to clinicians and health systems. A robust analytic strategy, integrating three established models helped to identify what worked best among the heterogeneous CKD management interventions. Our use of the ERIC checklist25 elicited otherwise overlooked implementation details and provided a normative comparison across studies. In addition, the triangulation of data through narrative insights and meta-analyses provided rich plausible explanations of why some implementation studies were more successful than others.

Limitations include high heterogeneity complicating evidence synthesis efforts. It is possible that the high I2 observed in our meta-analysis were because some implementation strategies were more effective than others. The high heterogeneity is not unlike other similar efforts at evidence synthesis of quality improvement and implementation strategies to manage chronic conditions in primary care.65 Due to the small number of studies included (n < 20) and high heterogeneity, we were unable to statistically evaluate publication bias (e.g., funnel plot, Egger’s regression test). The fact that most studies had at least one positive outcome suggests the presence of publication bias. We were hampered by limited reporting in published manuscripts in abstracting implementation strategies. These studies rarely included implementation outcomes as defined by Proctor et al.49 Finally, limited and non-uniform reporting across studies hampered our ability to analyze impact on all clinical outcomes. We did not include non-English studies so might have missed data in other languages.

Conclusion

Clinician-facing interventions, particularly guideline-concordant decision support has the potential to improve BP outcomes in primary care. These effects are larger when implementation is tailored to context and includes facilitation, local involvement, periodic feedback, and engaged leadership.

Better reporting of interventions, their implementation, and contextual factors in published studies are needed. Implementation outcomes such as acceptance, appropriateness, and feasibility should be part of primary studies. The sustainability of the successful intervention efforts and the cost-effectiveness of alternative implementation should be assessed.

Electronic supplementary material

(DOCX 23 kb)

(XLSX 40 kb)

(DOC 63 kb)

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Aaron Leppin MD for the implementation science expertise and advice with the study.

Authors’ Contributions

CCK and BT are the guarantors of this review. CCK conceptualized, designed, and coordinated the study; did the title and abstract and full-text review, data abstraction, data coordination, and clean-up; and drafted the initial and final manuscript. BT designed and coordinated the study; did the title and abstract and full-text review and data abstraction; and helped revise the manuscript. CCD and MAL helped in the design of the study; did the title and abstract and full-text review and data abstraction; and helped revise the manuscript. RGM did full-text review and data abstraction. CCD and RGM also provided substantial input and revisions to later drafts of the manuscript. AP did data abstraction, data coordination, and clean-up. PJE was responsible for the search strategy and literature search. JM did the title and abstract and full-text review and data abstraction. ME and JD did data abstraction. MA and ZW conducted meta-analyses. NDS and HMM provided guidance in conceptualizing the study and provided feedback through the project. HMM also guided strategy for analyses and provided substantial input into revisions to the manuscript. All authors read, added final revisions, and approved the final manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials

Available from the first author upon reasonable request.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Ethics Approval and Consent To Participate

Not required since human subjects were not involved.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable

Footnotes

Prior Presentations

This research was presented in two poster abstracts at the 11th Annual Conference on the Science of Dissemination & Implementation in Health, Academy Health; December 3–5, 2018, Washington DC.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Allen AS, Forman JP, Orav EJ, Bates DW, Denker BM, Sequist TD. Primary care management of chronic kidney disease. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(4):386–92. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1523-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Webster AC, Nagler EV, Morton RL, Masson P. Chronic kidney disease. Lancet. 2017;389(10075):1238–52. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32064-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coresh J, Selvin E, Stevens LA, Manzi J, Kusek JW, Eggers P, et al. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in the United States. JAMA. 2007;298(17):2038–47. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.17.2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jha V, Garcia-Garcia G, Iseki K, Li Z, Naicker S, Plattner B, et al. Chronic kidney disease: global dimension and perspectives. Lancet. 2013;382(9888):260–72. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60687-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grol R, Grimshaw J. From best evidence to best practice: effective implementation of change in patients’ care. Lancet. 2003;362(9391):1225–30. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14546-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levey AS, Schoolwerth AC, Burrows NR, Williams DE, Stith KR, McClellan W. Comprehensive public health strategies for preventing the development, progression, and complications of CKD: report of an expert panel convened by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;53(3):522–35. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;39(2 Suppl 1):S1-266. [PubMed]

- 8.Lea JP, McClellan WM, Melcher C, Gladstone E, Hostetter T. CKD risk factors reported by primary care physicians: do guidelines make a difference? Am J Kidney Dis. 2006;47(1):72–7. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kovacs E, Strobl R, Phillips A, Stephan AJ, Muller M, Gensichen J, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the effectiveness of implementation strategies for non-communicable disease guidelines in primary health care. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(7):1142–54. doi: 10.1007/s11606-018-4435-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Galbraith L, Jacobs C, Hemmelgarn BR, Donald M, Manns BJ, Jun M. Chronic disease management interventions for people with chronic kidney disease in primary care: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2018;33(1):112–21. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfw359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.LLC SC; Pages www.stata.com.

- 12.Silver SA, Bell CM, Chertow GM, Shah PS, Shojania K, Wald R, et al. Effectiveness of quality improvement strategies for the management of CKD: a meta-analysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;12(10):1601–14. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02490317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elliott MJ, Gil S, Hemmelgarn BR, Manns BJ, Tonelli M, Jun M, et al. A scoping review of adult chronic kidney disease clinical pathways for primary care. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2017;32(5):838–46. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfw208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu H, Mou L, Cai Z. A nurse-coordinated model of care versus usual care for chronic kidney disease: meta-analysis. J Clin Nurs. 2017;26(11-12):1639–49. doi: 10.1111/jocn.13533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bello AK, Qarni B, Samimi A, Okel J, Chatterley T, Okpechi IG, et al. Effectiveness of multifaceted care approach on adverse clinical outcomes in nondiabetic CKD: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Kidney Int Rep. 2017;2(4):617–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2017.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tesfaye WH, Castelino RL, Wimmer BC, Zaidi STR. Inappropriate prescribing in chronic kidney disease: a systematic review of prevalence, associated clinical outcomes and impact of interventions. Int J Clin Pract. 2017;71(7). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Chen CC, Chen Y, Liu X, Wen Y, Ma DY, Huang YY, et al. The efficacy of a nurse-led disease management program in improving the quality of life for patients with chronic kidney disease: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2016;11(5):e0155890. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0155890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wells G, B. Shea, D. O'Connell, J. Peterson, V. Welch, M. Losos, P. Tugwell 2012; Pages on July 15 2018.

- 19.Joosten H, Drion I, Boogerd KJ, van der Pijl EV, Slingerland RJ, Slaets JP, et al. Optimising drug prescribing and dispensing in subjects at risk for drug errors due to renal impairment: improving drug safety in primary healthcare by low eGFR alerts. BMJ Open. 2013;3(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ. 2015;350:g7647. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g7647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kamath CC, Claudia C. Dobler, Michelle A. Lampman, Patricia J. Erwin, John Matulis, Muhamad Elrashidi, Rozalina G. McCoy, Mouaz Alsawas, Atieh Pajouhi, Amrit Vasdev, Nilay D. Shah, M. Hassan Murad, Bjorg Thorsteinsdottir. Implementation strategies for interventions to improve the management of chronic kidney disease (CKD) by primary care clinicians: protocol for a systematic review. (accepted for publication at BMJ Open). 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness. JAMA. 2002;288(14):1775–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.14.1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness: the chronic care model, Part 2. JAMA. 2002;288(15):1909–14. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.15.1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Proctor EK, Landsverk J, Aarons G, Chambers D, Glisson C, Mittman B. Implementation research in mental health services: an emerging science with conceptual, methodological, and training challenges. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2009;36(1):24–34. doi: 10.1007/s10488-008-0197-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Powell BJ, Waltz TJ, Chinman MJ, Damschroder LJ, Smith JL, Matthieu MM, et al. A refined compilation of implementation strategies: results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project. Implement Sci. 2015;10:21. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0209-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Waltz TJ, Powell BJ, Matthieu MM, Damschroder LJ, Chinman MJ, Smith JL, et al. Use of concept mapping to characterize relationships among implementation strategies and assess their feasibility and importance: results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) study. Implement Sci. 2015;10:109. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0295-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tsang JY, Blakeman T, Hegarty J, Humphreys J, Harvey G. Understanding the implementation of interventions to improve the management of chronic kidney disease in primary care: a rapid realist review. Implement Sci. 2016;11:47. doi: 10.1186/s13012-016-0413-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Collaborations TC. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. 2011(5.1.0).

- 29.KDIGO. “KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease.” Kidney International. 2013. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, Juni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murad MH, Almasri J, Alsawas M, Farah W. Grading the quality of evidence in complex interventions: a guide for evidence-based practitioners. Evid Based Med. 2017;22(1):20–2. doi: 10.1136/ebmed-2016-110577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7(3):177–88. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tan J, McCready F, Noovao F, Tepueluelu O, Collins J, Cundy T. Intensification of blood pressure treatment in Pasifika people with type 2 diabetes and renal disease: a cohort study in primary care. N Z Med J. 2014;127(1404):17–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bhardwaja B, Carroll NM, Raebel MA, Chester EA, Korner EJ, Rocho BE, et al. Improving prescribing safety in patients with renal insufficiency in the ambulatory setting: the Drug Renal Alert Pharmacy (DRAP) program. Pharmacotherapy. 2011;31(4):346–56. doi: 10.1592/phco.31.4.346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pourrat X, Sipert AS, Gatault P, Sautenet B, Hay N, Guinard F, et al. Community pharmacist intervention in patients with renal impairment. Int J Clin Pharm. 2015;37(6):1172–9. doi: 10.1007/s11096-015-0182-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Humphreys J, Harvey G, Coleiro M, Butler B, Barclay A, Gwozdziewicz M, et al. A collaborative project to improve identification and management of patients with chronic kidney disease in a primary care setting in Greater Manchester. BMJ Quality and Safety. 2012;21. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Harvey G, Oliver K, Humphreys J, Rothwell K, Hegarty J. Improving the identification and management of chronic kidney disease in primary care: lessons from a staged improvement collaborative. International Journal for Quality in Health Care. 2015;27(1):10–6. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzu097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Humphreys J, Harvey G, Hegarty J. Improving CKD diagnosis and blood pressure control in primary care: a tailored multifaceted quality improvement programme. Nephron Extra. 2017;7(1):18–32. doi: 10.1159/000458712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abdel-Kader K, Fischer GS, Li J, Moore CG, Hess R, Unruh ML. Automated clinical reminders for primary care providers in the care of CKD: a small cluster-randomized controlled trial. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;58(6):894–902. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Akbari A, Swedko PJ, Clark HD, Hogg W, Lemelin J, Magner P, et al. Detection of chronic kidney disease with laboratory reporting of estimated glomerular filtration rate and an educational program. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Drawz PE, Miller RT, Singh S, Watts B, Kern E. Impact of a chronic kidney disease registry and provider education on guideline adherence—a cluster randomized controlled trial. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2012;12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Erler A, Beyer M, Petersen JJ, Saal K, Rath T, Rochon J, et al. How to improve drug dosing for patients with renal impairment in primary care—a cluster-randomized controlled trial. BMC Fam Pract. 2012;13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Fox CH, Swanson A, Kahn LS, Glaser K, Murray BM. Improving chronic kidney disease care in primary care practices: an Upstate New York Practice-Based Research Network (UNYNET) study. J Am Board Fam Med. 2008;21. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Karunaratne K, Stevens P, Irving J, Hobbs H, Kilbride H, Kingston R, et al. The impact of pay for performance on the control of blood pressure in people with chronic kidney disease stage 3–5. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2013;28. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Litvin CB, Hyer JM, Ornstein SM. Use of clinical decision support to improve primary care identification and management of chronic kidney disease (CKD) Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine: JABFM. 2016;29(5):604–12. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2016.05.160020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lusignan S, Gallagher H, Jones S, Chan T, Vlymen J, Tahir A, et al. Audit-based education lowers systolic blood pressure in chronic kidney disease: the quality improvement in CKD (QICKD) trial results. Kidney Int. 2013;84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Manns B, Tonelli M, Culleton B, Faris P, McLaughlin K, Chin R, et al. A cluster randomized trial of an enhanced eGFR prompt in chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7(4):565–72. doi: 10.2215/CJN.12391211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stoves J, Connolly J, Cheung CK, Grange A, Rhodes P, O’Donoghue D, et al. Electronic consultation as an alternative to hospital referral for patients with chronic kidney disease: a novel application for networked electronic health records to improve the accessibility and efficiency of healthcare. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010;19(5):e54. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2009.038984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xu G, Major R, Shepherd D, Brunskill N. Making an IMPAKT; improving care of chronic kidney disease patients in the community through collaborative working and utilizing Information Technology. BMJ Qual Improv Rep. 2017;6(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Al Hamarneh YN, Tsuyuki RT, Jones CA, Manns B, Tonelli M, Scott-Douglass N, et al. Effectiveness of pharmacist interventions on cardiovascular risk in patients with CKD: a subgroup analysis of the randomized controlled RxEACH Trial. Am J Kidney Dis. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.Carter BL, Coffey CS, Ardery G, Uribe L, Ecklund D, James P, et al. Cluster-randomized trial of a physician/pharmacist collaborative model to improve blood pressure control. Circulation. Cardiovascular Quality & Outcomes. 2015;8(3):235–43. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.114.001283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chang AR, Evans M, Yule C, Bohn L, Young A, Lewis M, et al. Using pharmacists to improve risk stratification and management of stage 3A chronic kidney disease: a feasibility study. BMC Nephrology. 2016;17(1):168. doi: 10.1186/s12882-016-0383-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cooney D, Moon H, Liu Y, Miller RT, Perzynski A, Watts B, et al. A pharmacist based intervention to improve the care of patients with CKD: a pragmatic, randomized, controlled trial. BMC Nephrology. 2015;16:56. doi: 10.1186/s12882-015-0052-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Via-Sosa MA, Lopes N, March M. Effectiveness of a drug dosing service provided by community pharmacists in polymedicated elderly patients with renal impairment—a comparative study. BMC Fam Pract. 2013;14:96. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-14-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Barrett BJ, Garg AX, Goeree R, Levin A, Molzahn A, Rigatto C, et al. A nurse-coordinated model of care versus usual care for stage 3/4 chronic kidney disease in the community: a randomized controlled trial. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 56.Richards N, Harris K, Whitfield M, O’Donoghue D, Lewis R, Mansell M, et al. Primary care-based disease management of chronic kidney disease (CKD), based on estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) reporting, improves patient outcomes. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 57.Scherpbier-de Haan ND, Vervoort GM, van Weel C, Braspenning JC, Mulder J, Wetzels JF, et al. Effect of shared care on blood pressure in patients with chronic kidney disease: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Br J Gen Pract. 2013;63(617):e798–806. doi: 10.3399/bjgp13X675386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Thomas N, Gallagher H, Jain N. A quality improvement project to improve the effectiveness and patient-centredness of management of people with mild-to-moderate kidney disease in primary care. BMJ Qual Improv Rep. 2014;3(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 59.Yamagata K, Makino H, Iseki K, Ito S, Kimura K, Kusano E, et al. Effect of behavior modification on outcome in early- to moderate-stage chronic kidney disease: a cluster-randomized trial. PLoS One. 2016;11(3):e0151422. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0151422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, Hovmand P, Aarons G, Bunger A, et al. Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2011;38(2):65–76. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ioannidis JP, Trikalinos TA. The appropriateness of asymmetry tests for publication bias in meta-analyses: a large survey. Cmaj. 2007;176(8):1091–6. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.060410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chambers DA, Norton WE. The adaptome: advancing the science of intervention adaptation. Am J Prev Med. 2016;51(4 Suppl 2):S124–31. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Powell BJ, Fernandez ME, Williams NJ, Aarons GA, Beidas RS, Lewis CC, et al. Enhancing the impact of implementation strategies in healthcare: a research agenda. Front Public Health. 2019;7:3. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2019.00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]