Abstract

Abstract

Breast cancer is one of the leading causes of death among women. We employed in silico model to predict the mechanism of actions of selected novel compounds reported against breast cancer using ADMET profiling, drug likeness and molecular docking analyses. The selected compounds were andrographolide (AGP), dipalmitoylphosphatidic acid (DPA), 3-(4-Bromo phenylazo)-2,4-pentanedione (BPP), atorvastatin (ATS), benzylserine (BZS) and 3β,7β,25-trihydroxycucurbita-5,23(E)-dien-19-al (TCD). These compounds largely conform to ADMETlab and Lipinki’s rule of drug likeness criteria in addition to their lesser hepatotoxic and mutagenic effects. Docking studies revealed a strong affinity of AGP versus NF-kB (− 6.8 kcal/mol), DPA versus Cutlike-homeobox (− 5.1 kcal/mol), BPP versus Hypoxia inducing factor 1 (− 7.7 kcal/mol), ATS versus Sterol Regulatory Element Binding Protein 2 (− 7.2 kcal/mol), BZS versus Ephrin type-A receptor 2 (− 4.4 kcal/mol) and TCD versus Ying Yang 1 (− 9.4 kcal/mol). Likewise, interaction between the said compounds and respective gene products were evidently observed with strong affinities; AGP versus COX-2 (− 9.6 kcal/mol), DPA versus Fibroblast growth factor receptor (− 5.9 kcal/mol), BPP versus Vascular endothelial growth factor (− 5.8 kcal/mol), ATS versus HMG-COA reductase (− 9.1 kcal/mol), BZS versus L-type amino acid transporter 1 (− 5.3 kcal/mol) and TCD versus Histone deacytylase (− 7.7 kcal/mol), respectively. The compounds might potentially target transcription through inhibition of promoter-transcription factor binding and/or inactivation of final gene product. Thus, findings from this study provide a possible mechanism of action of these xenobiotics to guide in vitro and in vivo studies in breast cancer.

Graphic abstract

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s40203-020-00057-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Breast cancer, Compounds, In silico, Mechanism, Predictions, Docking

Introduction

In developed countries, incidence and mortality rates of most cancers are decreasing, while in developing countries incidence and mortality rates are increasing (Abdulkareem 2017). Breast cancer is the most common form of cancer among women with an increasing burden of over 35% between 1990 and 2010 (Hjelm et al. 2019; Shadap et al. 2019). In developing countries, individuals with breast cancer often present advanced stages which contributes to high mortality rates with an overall survival rate not exceeding 60% (Barbosa and Martel 2020). Fascinatingly and quite unfortunate, breast and cervical cancers are the two most common types of cancer responsible for approximately 50.3% of all cancer cases in Nigeria (CCP 2018).

A number of limitations have been attributed to the most common approaches for breast cancer treatment. They mainly include surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, stem cell and dendritic cell-based immunotherapy (Budzik et al. 2019; Yaghoubi et al. 2019). Cancer cells manipulate the normal growth and immune mechanism of the host cell, increasing the rate of proliferation leading to the formation of neoplasms (Yaghoubi et al. 2019). Currently targeted anti-cancer mechanisms include inhibition of mutagenesis, suppression of DNA adduct, inhibition of reactive oxygen species, and regulation of cell-cycle (Tsubura et al. 2011). Therefore, most chemotherapeutic approaches against breast cancer target induction of apoptosis and inhibition of tumor cells proliferation (Sheikhpoor 2019). Molecular subtyping has identified three distinct histological types of breast cancer: hormone receptor (HR) positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor (HER2/neu) positive, and triple-negative (TN) (Kumar et al. 2019). Triple-negative breast cancer is characterized by high invasiveness, poor prognosis and frequent relapse following treatment (Dehghani et al. 2019). Triple-negative breast cancer lacks progesterone (PR), estrogen (ER) and HER2 receptor expression and the phenotype is associated with metastasis, lower survival rate and shorter life expectancy (Budzik et al. 2019).

Several signaling pathways have been implicated in the regulation of apoptosis through the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), stress-activated protein kinase (SAPK)/Jun-N-terminal kinase (JNK) and p38 pathways (Tsubura et al. 2011; Zhu et al. 2018). Deactivation of phosphorylated ERK, which is activated by various growth factors and mitogens leads to inhibition of cell growth (Gong et al. 2018). Phosphorylation of JNK and p38 leads to prolonged activation of JNK/SAPK, and subsequent induction of apoptotic cell death (Ma et al. 2019). A number of protein targets such as histone acetyltransferase (p300), COX-2, adiponectin, leptin, among many others can promote cell proliferation, angiogenesis, invasiveness, metastasis, inhibition of apoptosis and immune-surveillance (Ahn et al. 2011; Peng et al. 2018). In addition, the transcriptional co-activators of the above mentioned targets could be of great importance in regulating cell growth, division and, preventing the cancer growth (Peng et al. 2018).

As a result of tumor resistance to therapy, toxicities and side effects associated with orthodox drugs vis-à-vis the cost effectiveness and affordability, a paradigm shift towards the use of natural substances has generated research interest to curb the growing burden of breast cancer. Natural dietary substances comprising phytochemicals have been found to be promising biotherapeutic agents in mitigating breast cancer. They act through induction of apoptosis, affecting cell proliferation and differentiation, inhibiting angiogenesis, and other cellular transduction pathways (Vadodkar et al. 2012) implicated in mammary carcinogenesis. Some of these natural products with reported anti-breast cancer effects are andrographolide (AGP) (Peng et al. 2018), dipalmitoylphosphatidic acid (DPA) (Chen et al. 2018), 3-(4-Bromo phenylazo)-2,4-pentanedione (BPP) (Talib and Al-noaimi 2018), atorvastatin (ATS) (Ma et al. 2019), benzylserine (BZS) (Geldermalsen et al. 2018) and 3β,7β,25-trihydroxycucurbita-5,23(E)-dien-19-al (TCD) (Bai et al. 2016).

Despite the reported effects of these phytocompounds and their metabolites in targeting certain genes implicated in mammary carcinogenesis and cancer, a clear understanding of the molecular mechanism of their actions still remains a challenging puzzle. Potential drug molecules must have affinity to target sites, be adequately absorbed, distributed, metabolized and excreted, while having minimal side effects. In silico prediction models are currently used to obtain consensus predictions on the suitability of study molecules, thereby saving effort, time and resources that could result in futile in vitro and in vivo experiments. Hence, in this communication we employed in silico model to predict the mechanism of actions based on three dimensional effects (compounds versus transcriptional factors, genes promoter region and gene products) of these novel compounds reported against breast cancer using ADMET profiling, drug likeness and molecular docking analyses. Findings from this study might unravel the mechanisms of action of these xenobiotics and validate the reported claims relating to the therapeutic potential of these compounds against breast cancer and carcinogenesis.

Materials and methods

Materials

Computational software used for this work includes UCSF Chimera (v. 1.0.1), Discovery Studio (v19.1.0.18287) and other online computational tools available.

Methods

Selection of novel compounds reported against breast cancer

Six compounds were selected as targets based on the previous report on their role in breast cancer. The selection criterion involved the use of an open target platform for identification of compounds most commonly reported on triple negative breast cancer (Carvalho-Silva et al. 2019). The SMILE and three dimensional structural format of the compounds selected were obtained from PubChem database with the CID number: andrographolide (5318517), atorvastatin (60823), Benzylserine (78457), dipalmitoylphosphatidic acid (446066), 3-(4-Bromophenylazo)-2, 4-pentanedione (3992276) and 3β, 7β, 25-Trihydroxycucurbita-5, 23(E)-dien-19-al (44577792).

Pharmacokinetic studies of the compounds by ADMET Analysis

The ADMET properties of the compounds were assessed using ADMETlab platform (https://admet.scbdd.com/webserver/ADMETprediction) as previously described by Jie et al. (2018). The assessment was carried out for each physiochemical property (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity) through submitting a SMILE format of the individual compound obtained from PubChem database. The analysis was carried-out based on a comprehensively collected database consisting of 288,967 entries from peer-reviewed publications, ChEMBL, EPA and DrugBank databases. All the data were checked and washed by Molecular Operating Environment (MOE, version 2016), divided into six classes (basic, A, D, M, E and T) and a series of subclasses according to their endpoint meanings. The corresponding basic information and experimental values of these entries form the basis for prediction on a new compound established on computational similarity check.

Drug likeness analysis

To determine the drug likeness properties of the selected compounds, the same ADMETlab platform was used (https://admet.scbdd.com/webserver/Druglikenessanalysis) as previously described by Jie et al. (2018). Three dimensional structures of the compounds sourced from PubChem were submitted through the platform. The compounds were screened for drug-likeness properties based on several expert criterions that are used in drug design considered crucial for any drug candidate. The most commonly used rules considered in this work include; Lipinski’s rule, Ghose’s rule, Operea’s rule, Veber’s rule and Varma’s rule.

Targets (transcriptional factors, promoter regions and gene products) Identification

The protein targets (gene product and their transcription factors) were selected based on their previous report; their central mechanistic role in breast cancer. Open target platform was used to select the target based on prioritization by scoring target-disease associations using evidence from 20 data sources (Carvalho-Silva et al. 2019). The score for the associations ranges from 0 to 1; the stronger the evidence for an association, the stronger the association score closer to 1. The three dimensional structures of the targets and transcription factors were obtained from Protein Data Bank. The transcription factors selected and their PDB codes include; cut like-homeobox (IX2N), hypoxia inducing factor1 (2YCO), ying and yang 1 (4C5I), sterol regulatory element-binding proteins-2 (1UKL), aryl hydrocarbon receptor (5YZY), activating transcription factor 4 (1CI6) while the gene products include; fibroblast growth factor receptor (4F64), cyclooxygenase 2 (3PGH), vascular endothelial growth factor(1QS2), hydroxy-3-methylgluteryl-CoA reductase (IHWL), L-type amino acid transporter 1 (6JMR), alanine, serine, cysteine-preferring transporter 2 (3SZA), histone deacetylase (3COY). Gene sequences of the selected targets (Homo sapien) were obtained from PubMed (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed) in FASTA format. The target sequence obtained from NCBI include; Fibroblast Growth Factor 1 (AE014296.5), Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (NM_001287044.2), Cyclo-oxygenase-2 (CM000252.1), Histone Deacetylase (CM000252.1), Hydroxy-3-Methylgluteryl-CoA Reductase (M62766.1), L-Type Amino Acid Transpoter (9AE014298.5). The sequences were uploaded to Promoter 2.0 prediction platform (https://www.cbs.dtu.dk) for prediction of possible promoter sequence (S_Table 1). The predicted sequences were converted to a 3D-helical structure (S_Figure 1) using Discovery studio (v19.1.0.18287) and saved as a protein data bank file (Biovia 2015).

Molecular docking of the compounds against targets (transcriptional factors, promoter regions and gene products)

The crystal structure of the targets were prepared by removing solvent molecules, co-crystallized ligands and optimized to simulate physiological conditions using Chimera v 1.1 (Pettersen et al. 2004). Polar hydrogen was added and partial charges were assigned to the standard residue using Gasteiger partial charge, which assumes all hydrogen atoms are represented explicitly. The most favorable binding interactions were determined by molecular docking studies using Chimera (V 1.1). The interactions of the docked complexes were studied visually with the help of Discovery Studio 2017 R2 Client (v17.2.0.16349).

Results

Pharmacokinetic studies

The pharmacokinetic studies of the compounds show that most of the compound display a moderate solubility based on distribution and partition coefficient (Table 1). The absorption of the compounds by human intestinal and human epithelial colorectal adenocarcinoma cells absorption models indicate a moderate absorption with respect to all the compounds with the exception of andrographolide and atorvastatin for human intestine and epithelial colorectal adenocarcinoma cells, respectively. Such compounds can also be distributed in the body efficiently. Most of the compounds indicated a potential ability to pass through the blood brain barrier with the exception of andrographolide. The metabolism of the compounds in consideration to Cytochrome 1A2 and 3A4 illustrate the compounds to possess a potent inhibition and substrate at different levels. All the compounds revealed a short clearance rate but a very low half-life time, non-mutagenic and hepatotoxic with the exception of andrographolide and atorvastatin.

Table 1.

Predicted pharmacokinetic profile of the selected compounds

| Category | Property (unit) | Predicted Result | Inference/reference range | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AGP | DPA | BPP | ATS | BZS | TCD | |||

| Basic physicochemical property | LogP (partition coefficient) (log mol/L) | 1.963 | 3.640 | 3.079 | 6.314 | 0.615 | 9.524 |

Optimal: 0 < LogP < 3 LogP < 0: poor lipid bilayer permeability LogP > 3: poor aqueous solubility |

| LogD7.4 (Distribution coefficient D) (log mol/L) | 2.007 | 10.513 | 2.325 | 1.479 | −1.152 | 4.757 |

< 1: high solubility; 1–3: moderate solubility; ≥ 3: low solubility |

|

| Absorption | Papp (Caco-2 permeability) (cm/s) | −4.986 | −5.013 | −4.358 | −5.336 | −5.029 | −4.662 | Optimal: higher than − 5.15 or − 4.70 |

| HIA (Human Intestinal Absorption) (%) | 0.406 | 0.784 | 0.61 | 0.549 | 0.69 |

> 0.5: HIA positive < 0.5: HIA negative |

||

| Distribution | PPB (Plasma protein binding) (%) | 80.363 | 61.791 | 78.149 | 95.731 | 48.824 | 75.145 | 90%: Significant with drugs that are highly protein-bound and have a low therapeutic index |

| BBB (Blood brain barrier) (%) | 0.691 | 0.423 | 0.876 | 0.884 | 0.898 | 0.97 |

≥ 0.1: BBB positive < 0.1: BBB negative |

|

| Metabolism | CYP1A2-Inhibitor | 0.039 | 0.376 | 0.79 | 0.554 | 0.049 | 0.06 |

> 0.5: An inhibitor < 0.5: Non-inhibitor |

| CYP1A2-Substrate | 0.345 | 0.226 | 0.518 | 0.849 | 0.154 | 0.42 |

> 0.5: Substrate < 0.5: Non-substrate |

|

| CYP3A4-Inhibitor | 0.135 | 0.23 | 0.004 | 0.555 | 0.004 | 0.31 |

> 0.5: An inhibitor < 0.5: Non-inhibitor |

|

| CYP3A4-Substrate | 0.558 | 0.02 | 0.345 | 0.778 | 0.122 | 0.53 |

> 0.5: Substrate < 0.5: Non-substrate |

|

| Excretion | Clearance (mL/min/kg) | 1.808 | 0.746 | 0.661 | 1.554 | 1.649 | 1.985 |

Range: > 15 high; 5 < Cl < 15: moderate; < 5: low |

| T1/2 (Half life) (H) | 1.263 | 1.673 | 1.384 | 1.938 | 0.882 | 1.22 |

Range: > 8H: high; 3 h < Cl < 8H: moderate; < 3H: low |

|

| Toxicity | hERG (hERG blockers) | 0.337 | 0.31 | 0.28 | 0.644 | 0.161 | 0.43 |

> 0.5: A Blocker < 0.5: Non-blocker |

| H-HT (Human Hepatotoxicity) | 0.78 | 0.01 | 0.54 | 0.972 | 0.458 | 0.01 |

> 0.5: HHT positive < 0.5: HHT negative |

|

| AMES (Ames mutagenicity) | 0.34 | 0.148 | 0.394 | 0.082 | 0.184 | 0.19 |

> 0.5: Positive < 0.5: Negative |

|

AGP andrographolide, DPA dipalmitoyphosphatidic acid, BPP 3-(4-Bromophenylazo)-2, 4-pentanedione, ATS atorvastatin, BZS benzyl-serine, TCD 3β, 7β, 25-Trihydroxycucurbita-5, 23(E)-dien-19-al

Drug likeness analysis

Drug likeness properties of the selected compounds were determined using criteria put forward by Lipinski, Ghose, Oprea, Vaber and Verma. The results obtained were shown (Table 2) containing the parameter assessed, the scores and percentages compliance to individual rules, respectively. All the compounds show strong compliance with Lipinski’s, Veber’s and Verma’s rule, while dipalmitoyl phosphatidic acid, atorvastatin and 3β, 7β, 25-trihydroxy cucurbita-5,23(e)-dien-19-al display very poor submission with Ghose’s rule. Benzylserine and dipalmitoyl phosphatidic show poor agreement to Oprea’s rule with 33.33% and 0.0%, respectively.

Table 2.

Drug-likeness properties of the selected compounds

| S/N | Name of rule | Property | Rules | Predicted result and percentages matches for dipalmitoylphosphatic acid | Predicted result and percentages matches for andrographolide | Predicted result and percentages matches for 3-(4-bromophenylazo)-2,4-pentanedione | Predicted result and percentages matches for atorvastatin | Predicted result and percentages matches for benzyl serine | Predicted result and percentages matches for 3β, 7β, 25-trihydroxycucurbita-5,23(e)-dien-19-al | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Lipinki’s rule | Molecular weight | ≤ 500 | 648.9 | 50% | 350.4 | 100% | 283.1 | 100% | 558.6 | 50% | 195.2 | 100% | 414.8 | 75.0% |

| Lipophilicity (logP) | ≤ 5 | 10.513 | 1.963 | 0 | 6.314 | 0.615 | 9.524 | ||||||||

| Hydrogen bond acceptor | ≤ 10 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 0 | ||||||||

| Hydrogen bond donors | ≤ 5 | 2 | 3 | 3.073 | 4 | 2 | 0 | ||||||||

| 2 | Ghose’s rule | Lipophilicity (logP) | − 5.6 < logP < − 0.4 | 10.5 | 0.00% | 1.963 | 100% | 3.073 | 100% | 6.314 | 0.00% | 0.615 | 100% | 414.8 | 25.0% |

| Molecular weight | 160 < MW < 480 | 648.9 | 350.4 | 283.1 | 558.6 | 195.2 | 9.524 | ||||||||

| Molar refractivity | 40 < MR < 130 | 179.4 | 93.56 | 27 | 76.00 | 51.71 | 131.5 | ||||||||

| Total number of atoms | 20 < atoms < 70 | 113 | 55 | 63.80 | 157.2 | 27 | 84 | ||||||||

| 3 | Oprea’s rule | Number of rings | ≥ 3 | 0 | 33.33% | 24 | 66.67% | 1 | 66.7% | 4 | 100% | 1 | 0% | 4 | 66.7% |

| Number of rigid bonds | ≥ 18 | 7 | 3 | 12 | 31 | 9 | 28 | ||||||||

| No. of rotatable bonds | ≥ 6 | 36 | 3 | 4 | 13 | 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | Veber’s rule | No. of rotatable bonds | ≥ 10 | 36 | 66.67% | 3 | 100% | 4 | 100% | 13 | 66.7% | 5 | 100% | 5 | 100% |

| TPSA | ≤ 140 | 119.3 | 86.99 | 58.86 | 111.8 | 72.55 | 0 | ||||||||

| Hydrogen bond donor | ≤ 12 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 0 | ||||||||

| Hydrogen bond acceptor | ≤ 12 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 3 | |||||||||

| 5 | Varma’s rule | Molecular weight | ≤ 500 | 648.9 | 100% | 350.4 | 100% | 283.1 | 100% | 558.7 | 60% | 195.2 | 100% | 414.8 | 100% |

| TPSA | ≤ 125 | 119.3 | 86.99 | 58.86 | 111.8 | 72.55 | 0 | ||||||||

| Hydrogen bond donor | ≤ 9 | 2 | 2.007 | 2.325 | 4 | 2 | 0 | ||||||||

| Hydrogen bond acceptor | ≤ 9 | 6 | 3 | 0 | 5 | 3 | 0 | ||||||||

| 5 | 4 | ||||||||||||||

| 3 | |||||||||||||||

Molecular docking studies

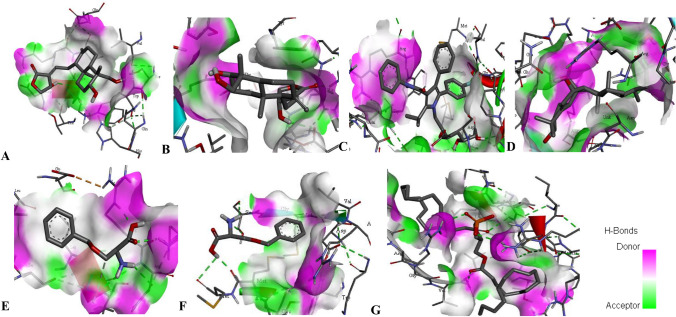

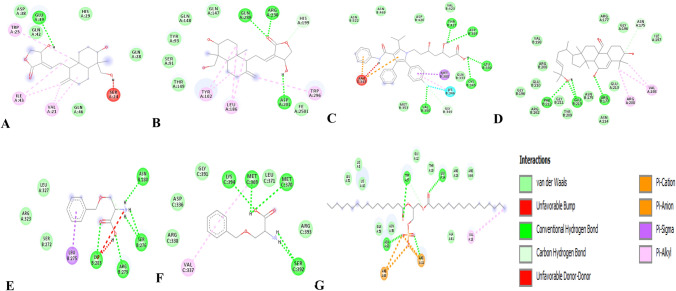

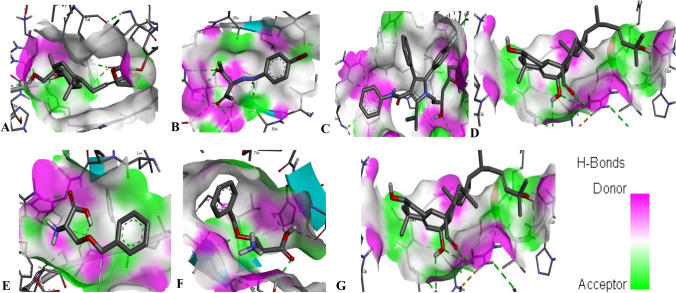

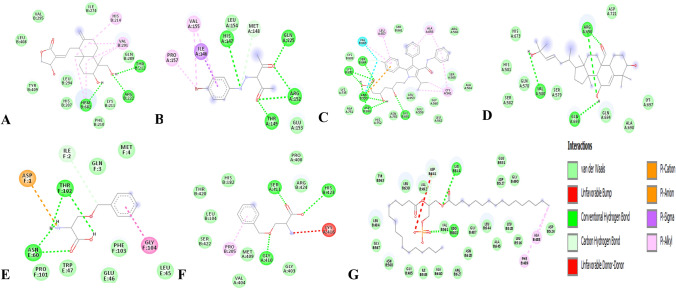

Binding energy and inhibition binding constants of the various interactions were found to be impressive as shown in Tables 3 and 4. Strong interactions were recorded between transcription factors and the compounds (Table 3). Similar interaction was observed when the compounds were docked with the target proteins and the promoter regions coding the target proteins (Table 4 and S_Table 2). All the compounds bound to the target proteins and the promoter region reasonably with binding interactions. The interactions resulted from both polar and nonpolar amino acid residue found within the binding cavities of the proteins (Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4 and S_Figure 2). In addition, hydrogen, hydrophobic and other non-conventional interactions were found to exist between the compounds and the targeted receptors.

Table 3.

Binding energy and inhibition binding constant of the transcription factor with the various compounds

| Target name and PDB code | Compounds | Binding energy (kCal) | Inhibition constant (µM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cutlike-homeobox (5ZXE) | DPA | − 5.1 | 0.991 |

| Cutlike-homeobox (5ZXE) | AGP | − 6.8 | 0.988 |

| Hypoxia inducing factor1 (2GIM) | AGP | − 7.7 | 0.986 |

| Sterol regulatory element-binding proteins -2 [1UKL] | ATS | − 7.2 | 0.987 |

| Aryl hydrocarbon receptor (5YZY) | BZS | − 4.4 | 0.992 |

| Activating transcription factor 4 (1CI6) GENE | BZS | − 4.4 | 0.992 |

| Ying and Yang 1 (4C5I) | TCD | − 9.4 | 0.983 |

Three letter code in bracket indicate protein data bank identification code

AGP andrographolide, DPA dipalmitoyphosphatidic acid, BPP 3-(4-bromophenylazo)-2, 4-pentanedione, ATS atorvastatin, BZS benzyl-serine, TCD 3β, 7β, 25-trihydroxycucurbita-5, 23(E)-dien-19-al

Table 4.

Binding energy and inhibition binding constant of the protein targets with the various compounds

| Target name and PDB code | Compounds | Binding energy (kCal) | Inhibition constant (µM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fibroblast growth factor receptor (5Z2S) | DPA | − 5.9 | 0.989 |

| Cyclooxygenase 2 (5KIR) | AGP | − 9.6 | 0.983 |

| Vascular endothelial growth factor (3QTK) | BPP | − 5.8 | 0.990 |

| Hydroxy-3-methylgluteryl-CoA reductase [3CCT] | ATS | − 9.1 | 0.984 |

| L-type amino acid transporter 1 (6IRS) | BZS | − 5.3 | 0.990 |

| Alanine, serine, cysteine-preferring transporter 2 (6RVX) | BZS | − 6.4 | 0.989 |

| Histone deacetylase (6CEF) | TCD | − 7.7 | 0.986 |

Three letter code in bracket indicate protein data bank identification code

AGP andrographolide, DPA dipalmitoylphosphatidic acid, BPP 3-(4-bromophenylazo)-2, 4-pentanedione, ATS atorvastatin, BZS benzyl-serine, TCD 3β, 7β, 25-trihydroxycucurbita-5, 23(E)-dien-19-al

Fig. 1.

3D interaction of the compounds with transcription factor. a NF-KB with andrographolide, b BPP with HF1, c ATS with SREBP-2, d TCD with Ying Yang 1, e BZS with EphA2, f BZS with AHR, g DPA with CHB

Fig. 2.

2D interaction of the compounds with transcription factor. a NF-KB with andrographolide, b BPP with HF1, c ATS with SREBP-2, d TCD with Ying Yang 1, e BZS with EphA2, f BZS with AHR, g DPA with CHB

Fig. 3.

3D interaction of the compounds with a protein end-product. a COX-2 with andrographolide, b BPP with VEGF, c ATS with HMGCR, d TCD with HDAC, e BZS with LAT1, f BZS with ASCT2, g DPA with FGFR

Fig. 4.

2D interaction of the compounds with a protein end-product. a COX-2 with andrographolide, b BPP with VEGF, c ATS with HMGCR, d TCD with HDAC, e BZS with LAT1, f BZS with ASCT2, g DPA with FGFR

Discussion

Metabolism in tumor cells requires sufficient nutrient, nucleic acids, and biomolecules to synthetize substances needed for proliferation and growth (Guan et al. 2018). Over the years, considerable numbers of failure rates were recorded in the field of drug discovery and these reflect insufficient understanding of the role of the chosen target in disease, and the consequences of modulating it with a drug (Carvalho-Silva et al. 2019). Numerous pathways identified to be active during cell proliferation and growth has been reported to play a potential role in interfering with tumor formation (Singh et al. 2013). Therefore, targeting biomolecules involved in these pathways could be a novel strategy for treatment and management of tumor growth. Natural compounds with low toxicity, high tolerability and wide bioavailability have attracted growing interest for use in cancer chemoprevention (Wang et al. 2013). Several natural compounds were reported to be effective in inhibiting breast cancer growth (Wang et al. 2012). For instance, andrographolide has been reported to inhibit breast cancer through suppressing COX-2 expression and angiogenesis via inactivation of p300 signaling and VEGF pathway (Peng et al. 2018); 3-(4-Bromo phenylazo)-2,4-pentanedione as a promising anticancer agent that can inhibit breast cancer cells through apoptosis induction and angiogenesis inhibition (Talib and Al-noaimi 2018); 3β,7β,25-trihydroxy cucurbita-5,23(E)-dien-19-al ability to induce breast cancer cell apoptosis was accompanied by downregulation of Akt-NF-κB signaling, up-regulation of p38 mitogen activated protein kinase and p53, increased reactive oxygen species generation as well as inhibition of histone deacetylases protein expression (Bai et al. 2016); atorvastatin inhibiting breast cancer cells by downregulating PTEN/AKT pathway via promoting ras homolog family member B (RhoB) (Ma et al. 2019); benzylserine inhibiting breast cancer cell growth by disrupting intracellular amino acid homeostasis and triggering amino acid response pathways (Geldermalsen et al. 2018), and dipalmitoyl phosphatidic acid reported to have inhibited breast cancer growth by suppressing angiogenesis via inhibition of the CUX1/FGF1/HGF signaling pathway (Chen et al. 2018). However, despite this avalanche reported biological activities of these novel compounds, their potential drug properties and underlying molecular mechanisms of action remain a challenging puzzle. Herein for the first time, we showed how in silico model predicts the mechanism of action based on three dimensional effects (compounds versus transcriptional factors, genes promoter region and gene products) of these novel compounds reported against breast cancer using ADMET profiling, drug likeness and molecular docking analyses.

ADMET studies comprise of pharmacokinetic properties which determine whether a drug will get to the target protein in the body, and how long it will stay in the bloodstream (Dong et al. 2018). It is aimed at calculating many physical properties such as polarity, surface area, water solubility, and absorption properties of a compound by means of human Intestinal absorption, permeability for Caco-2 cell, Blood–Brain-Barrier (BBB) penetration, and plasma protein binding (Golla et al. 2014). LogP is an octanol–water partition coefficient and can be defined as the relative concentration of the solute in octanol and water. It is a measure of the degree of hydrophobicity and plays a role in drug absorption via the phospholipid bilayer (Prashantha Kumar et al. 2010). LogP value between a negative value and 3 is necessary for drugs to possess satisfactory absorption via the phospholipid bilayer. Although, a more polar drug usually encounters difficulties when passing through phospholipid bilayer into the cell (Yusof and Segall 2013). The compounds used for this study demonstrated a moderate solubility in both polar and nonpolar environments. This suggested that the compounds with the exception of Benzylserine can be partially transported through extracellular fluids and across cell membranes. Meanwhile, a compound like benzylserine can be efficiently transported because of its high solubility in aqueous extracellular suspension. Similar moderate pattern in physicochemical properties by different compounds were reported (Ali et al. 2017), as passive diffusion through a cell membrane is a key element of transcellular absorption (Segall and Greene 2014). Therefore, these compounds must be able to partition into the membrane after desolvation from the polar aqueous GI tract and then diffuse across the nonpolar membrane and resolvate upon exit at the other side (Doak et al. 2014). The compounds also demonstrated partial absorption through human intestinal absorption and epithelial colorectal adenocarcinoma cell-line. This increases the chance of drugs reaching their targets at an effective concentration for proper elicitation of action. Fascinatingly, compounds in the present study could be transported efficiently through bloodstream to their various targets as evidence from plasma binding abilities bearing in mind that, drugs passing through blood–brain barrier might likely cause a serious damaging effect that can lead to a greater metabolic complications. Cytochrome P450 induction is less likely to increase drug interactions through formation of an active metabolite which could lead to more efficiency (Kamel and Harriman 2013) as evidently observed in our study. Conversely, inhibition of the enzymes can produce reactive metabolites which lead to toxicity (Fontana et al. 2005). The compounds interact weakly with cytochrome 1A2 and 3A4, which indicate the little role these enzymes played in metabolism of the chosen compounds. This is in agreement with the pharmacokinetic studies carried out on atorvastatin with significant plasma protein binding and interaction with cytochrome 3A4 (Lennernäs 2003).

Drug-likeness analysis preliminarily screens out some promising compounds that are likely to be drugs based on some properties considered crucial (Dong et al. 2018). Virtually all the compounds indicated a potential druggable character, with the exception of molecular weight and number of rotatable bonds. Hydrogen bond acceptors and donors in drug structures play an important role in water solubility, membrane transport, distribution, and drug-receptor interactions (Cheng et al. 2007; Prashantha Kumar et al. 2010). Hydrogen bond donors were counted by considering hydrogen atoms connected directly to oxygen and/or nitrogen atoms in their structures (Prashantha Kumar et al. 2010). About zero to five hydrogen bond donors and zero to ten hydrogen bond acceptors are necessary for the drugs to possess a satisfactory bioavailability and the optimum number of drug-receptor interactions via hydrogen bonds (Dong et al. 2018). Molecular weight indicates the mass as well as the size, volume, and density (Prashantha Kumar et al. 2010). Molecular weight plays a greater role in determining the solubility, absorption and distribution of a given drug candidate (Doak et al. 2014). However, most of the compounds reported in this work appear to violate this parameter. Drug-receptor interactions are associated with the conformational distortions of both the drug and the receptor complementing one another (Yusof and Segall 2013). Conformational distortions in turn depend on the presence of rotatable bonds in drug structures. The number of rotatable bonds also determined the degree of freedom with respect to conformational stability of a drug candidate in the biological system. The TPSA indicates the surface area required to bind with the majority of the target receptors (Prashantha Kumar et al. 2010). TPSA is a very good descriptor for characterizing drug absorption, including intestinal absorption, bioavailability, permeability, and blood–brain barrier penetration. TPSA value less than 125 is necessary for the drugs to possess a satisfactory bioavailability (Dong et al. 2018). Aromatic rings also play an important role in contributing to hydrophobicity by exhibiting Van der Waals forces of attractions or p stackings with target receptors (Cheng et al. 2007). Greater or equal to 3 aromatic rings are necessary for the drugs to possess satisfactory bioavailability and drug-receptor interactions via Van der Waals forces of attraction or p stackings (Dong et al. 2018). Nevertheless, large numbers of aromatic rings reduced hydrophilicity, as a result of which the water solubility was decreased, leading to poor drug distribution in the body.

Transcription factors bind to specific DNA regulatory sequences such as silencer, promoter, together with other molecules that initiate the recruitment of transcription machinery for protein expression (Lambert et al. 2018). Binding of many small molecules to transcription factors or promoter sequence can alter their interaction from two sided approach, which probably leads to induction or inhibition of gene expression. In the same style, the final gene product can be activated or inhibited, depending on the site of interaction and the residues involved. The selected compounds demonstrated a very strong binding affinity with the promoter element of the gene coding for the targets proteins and with their respective transcription factors. This binding can prevent or impair the recruitment of transcription factors around promoter sequence elements, thus affecting transcription and gene expression. Both the interactions with the DNA segment and transcriptions factors involved both polar and nonpolar residues existing within their binding cavities. Hydrogen bond was observed between andrographolide with asparagine (139) of the NF-kB, BPP with histidine (374) and tyrosine (303) of HIF1, atorvastatin with asparagine (469) of SREBP-2, TCD with aspartate (538) and tryptophan (536) of Ying Yang 1, benzyl serine with threonine (101) of EphA2, benzylserine with aspartate (196) of AHR, and finally dipalmitoyl phosphatidic acid interact with CHB only through hydrophobic and Vander Waals forces. COX-2 expression could be transcriptionally regulated by the recruitment of trans-activators and coactivators to the corresponding sites of its promoters (Peng et al. 2018). Previous studies indicate that andrographolide can bind to NF-kB and disable its DNA binding activity (Peng et al. 2018; Zhu et al. 2013). However, repulsive forces were also recorded in all the compounds with the exception of atorvastatin. Steric unfavorable forces usually weaken the interaction and can lead to competitive displacement.

All the target receptors carefully chosen in this work were implicated in pathways involved directly or indirectly to cell proliferations and growth especially as it relates to mammary carcinogenesis and cancer. High expression of COX-2 has been reported to promote proliferation, angiogenesis, invasiveness, metastasis, inhibition of apoptosis and immune-surveillance (Zhang et al. 2014). Andrographolide binds to COX-2 through hydrogen bonds with glutamate (465) and arginine (46) and other non-conventional interactions. Therefore, inhibition of the enzyme or its expression could play a central role in interrupting the processes started above, hence, cancer cells death. Angiogenesis is initiated through recruitment of multiple angiogenic factors from cancer cells, such as VEGF, FGF and HGF and many others (Ruf and Yokota 2010). Although, VEGF identified as the most important and upon binding to VEGF receptors on the surface of endothelial cell, signal pathways including Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK and PI3K/Akt will be activated, which sequentially promote endothelial cells recruitment and proliferation (Wang et al. 2013). 3-(4-Bromo phenylazo)-2, 4-pentanedione can bind to both VEGF, its promoter sequence as well as transcription factor through both polar and nonpolar interactions. The interaction could lead to inhibition of angiogenesis through inactivation of VEGF signaling and or its expression. 3-(4-Bromo phenylazo)-2, 4-pentanedione was reported to inhibit the growth in breast cancer cell line through down regulation of VEGF (Talib and Al-noaimi 2018). In the same manner, dipalmitoyl phosphatidic acid interacts with fibroblast growth factor 1, its promoter region and transcription factor responsible for its expression. Dipalmitoyl Phosphatidic acid was reported to directly inhibit proliferation, migration and tube formation of vascular endothelial cells through modulation of cut-like homeobox (Chen et al. 2018). High cholesterol level has been related to incidence of breast cancer and products of mevalonate pathways have been reported to promote migration, proliferation, differentiation, and intracellular trafficking of tumor cells (Dimitroulakos et al. 2006). Therefore, reduction in products of the mevalonate pathway such as cholesterol can affect cell proliferation and differentiation of tumor cells. Atorvastatin was reported to inhibit tumor cells invasion, proliferation and promote apoptosis both in vitro and in vivo (Ma et al. 2019). Cancer cells selectively up-regulate amino acid transporters to facilitate rapid uptake of amino acids such as leucine and glutamine (Geldermalsen et al. 2018). These amino acids are very crucial in cell proliferation for biosynthesis of macromolecules, generation of cellular energy, and stimulation of the mTORC1 signaling pathway (Babu et al. 2003). Leucine uptake is predominantly mediated by the L-type amino acid transporter (LAT) family while glutamine transport is facilitated by alanine, serine, cysteine-preferring transporter 2 (ASCT2) in multiple cancer cells (Babu et al. 2003; Body et al. 2005). Benzylserine can modulate the expression of LAT1 and ASCT2 and or their activity through promoter region binding and gene product inhibition. It has been reported that (Geldermalsen et al. 2018), benzylserine inhibited the uptake of leucine and glutamine in MCF-7, HCC1806 and MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cell-line, causing decreased cell viability and cell cycle progression. A balance in the opposing actions of histone acetyltransferases and histone deacetylases is necessary for epigenetic regulation of gene expression (Zucchetti et al. 2019). Impairment in the balance between the actions of these enzymes has been reported in the development of breast cancer (Guo et al. 2018). Therefore, histone deacetylase inhibitors can maintain the cellular acetylation profile and reverse the function of several proteins responsible for breast cancer development (Damaskos et al. 2017; Ediriweera et al. 2019). 3β,7β,25-trihydroxy cucurbita-5,23(E)-dien-19-al was recounted to inhibit histone deacetylases protein expression and suppression of MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cell-lines (Bai et al. 2016). These findings among other information have invariably corroborated with our in silico results.

Conclusion

The compounds indicate potential drugs properties based on the ADMET studies and drug likeness analyses. Although, passing these rules could be biased as the rules are rigid and could lead to the risk of rejecting valuable compounds. Therefore, other criteria not considered in these rules should be given appropriate consideration for critical and thorough evaluation. The compounds also bind to promoter sequence, transcription factors and the final gene product with appreciative binding interactions. These compounds could potentially induce changes in the pathways involved leading to the death of breast cancerous cells. Collectively, findings from this study might have unraveled the mechanisms of actions of these xenobiotics and validate the reported claims as it relates to the chemotherapeutic potential of these compounds against breast cancer and carcinogenesis.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Dr. David A. Ebuka of the Chemistry Department, Ahmadu Bello University Zaria and Prof. M.N. Shuaibu of Biochemistry Department Ahmadu Bello University Zaria for their assistance and guidance towards successful completion of this work. We also wish to thank Mrs. Salamatu Sani of English and Literary studies Department of Ahmadu Bello University Zaria for improving the quality of this manuscript.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

Authors declare that there is no conflict of interest with regards to the publication of this paper.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Abdulkareem F. Epidemiology & incidence of common cancers in Nigeria. J Cancer Biol Res. 2017;5:1105. [Google Scholar]

- Ahn SC, Jang H, Bae SK. Curcumin down-regulates visfatin expression and inhibits breast cancer cell invasion. Endocrinology. 2011;153:554–563. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali A, Badawy MEI, Shah R, Rehman W, El Y. Synthesis, characterization and in-silico ADMET screening of mono- and di-hydrazides and hydrazones. Der Chem Sin. 2017;8:446–460. [Google Scholar]

- Babu E, Kanai Y, Chairoungdua A, Kim DK, Iribe Y, Tangtrongsup S, Jutabha P, Li Y, Ahmed N, Sakamoto S, et al. Identification of a novel system L amino acid transporter structurally distinct from heterodimeric amino acid transporters. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:38–45. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305221200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai LY, Chiu CF, Chu PC, Lin WY, Chiu SJ, Weng JR. A triterpenoid from wild bitter gourd inhibits breast cancer cells. Sci Rep. 2016;6:1–10. doi: 10.1038/srep22419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa AM, Martel F. Targeting glucose transporters for breast cancer therapy : the effect of natural and synthetic compounds. Cancers (Basel) 2020;12:154. doi: 10.3390/cancers12010154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biovia DS (2015) Discovery studio modeling environment. In: San Diego, Dassault Systemes, Release, vol 4

- Body S, Martin L, Zorzano A, Palacin M, Estevez R, Bertran J. Identification of LAT4, a novel amino acid transporter with system L activity. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:12002–12011. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408638200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budzik MP, Sobieraj MT, Sobol M, Patera J, Czerw A. histopathological analysis and comparison with invasive ductal breast cancer Medullary breast cancer is a predominantly triple- negative breast cancer—histopathological analysis and comparison with invasive ductal breast cancer. Arch Med Sci. 2019 doi: 10.5114/aoms.2019.86763.10.5114/aoms.2019.86763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CCP (2018) Nigerian National Cancer Control Plan 2018–2022, pp 1–67

- Carvalho-Silva D, Pierleoni A, Pignatelli M, Ong CK, Fumis L, Karamanis N, Carmona M, Faulconbridge A, Hercules A, McAuley E. Open targets platform: new developments and updates two years on. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:1056–1065. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Zhou Z, Yao Y, Dai J, Zhou D, Zhang LWQ. Dipalmitoylphosphatidic acid inhibits breast cancer growth by suppressing angiogenesis via inhibition of the CUX1/FGF1/HGF signalling pathway. J Cell Mol Med. 2018;2018:1–11. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.13727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng AC, Coleman RG, Smyth KT, Cao Q, Soulard P, Caffrey DR, Salzberg AC, Huang ES. Structure-based maximal affinity model predicts small-molecule druggability. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:71–75. doi: 10.1038/nbt1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damaskos C, Valsami S, Kontos M, Spartalis E, Kalampokas T, Kalampokas E, Athanasiou A, Moris D, Daskalopoulou A, Davakis S, Tsourouflis G, Kontzoglou K, Perrea D, Nikiteas N, Dimitroulis D. Histone deacetylase inhibitors: an attractive therapeutic strategy against breast cancer. Anticancer Res. 2017;37:35–46. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.11286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehghani S, Kooshafar Z, Almasirad A, Tahmasvand R, Moayer F, Muhammadnejad A, Shafiee S, Salimi M. A novel hydrazide compound exerts anti-metastatic effect against breast cancer. Biol Res. 2019;52:1–8. doi: 10.1186/s40659-019-0247-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimitroulakos J, Lorimer AGG. Strategies to enhance epidermal growth factor inhibition: targeting the mevalonate pathway. Clin Cancer. 2006;12:4426s–4431s. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doak BC, Giordanetto F, Kihlberg J. Review oral druggable space beyond the rule of 5: insights from drugs and clinical candidates. Chem Biol Rev. 2014;21:1115–1142. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2014.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong J, Wang NN, Yao ZJ, Zhang L, Cheng Y, Ouyang D, Lu AP, Cao DS. Admetlab: a platform for systematic ADMET evaluation based on a comprehensively collected ADMET database. J Cheminform. 2018 doi: 10.1186/s13321-018-0283-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ediriweera MK, Tennekoon KH, Samarakoon SR. Emerging role of histone deacetylase inhibitors as anti-breast-cancer agents. Drug Discov Today. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2019.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontana E, Dansette PM, Poli SM, Plan C, Ge O. Cytochrome P450 enzymes mechanism based inhibitors: common sub-structures and reactivity. Curr Drug Metab. 2005;6:413–454. doi: 10.2174/138920005774330639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geldermalsen MV, Quek L, Turner N, Freidman N, Pang A, Guan YF, Krycer JR, Ryan R, Wang Q, Holst J. Benzylserine inhibits breast cancer cell growth by disrupting intracellular amino acid homeostasis and triggering amino acid response pathways. BMC Cancer. 2018;18:1–14. doi: 10.1186/s12885-017-3892-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golla UR, State P, Medical H, Sunder S, Bhimathati R. In SILICO design and ADMET prediction of rivastigmine analogues for treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. An Int J Adv Pharm Sci. 2014;4:270–278. [Google Scholar]

- Gong X, Smith JR, Swanson HM, Rubin LP. Carotenoid lutein selectively inhibits breast cancer cell growth and potentiates the effect of chemotherapeutic agents through ROS-mediated mechanism. Molecules. 2018;23:1–18. doi: 10.3390/molecules23040905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan M, Tong Y, Guan M, Liu X, Wang M, Niu R. Lapatinib inhibits breast cancer cell proliferation by influencing PKM2 expression. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2018;17:1–12. doi: 10.1177/1533034617749418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo P, Chen W, Li H, Li M, Li L. The histone acetylation modifications of breast cancer and their therapeutic implications. Pathol Oncol Res. 2018 doi: 10.1007/s12253-018-0433-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hjelm TE, Matovu A, Mugisha N, Lo J. Breast cancer care in Uganda: a multicenter study on the frequency of breast cancer surgery in relation to the incidence of breast cancer. PLoS ONE. 2019;14:1–10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0219601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jie D, Ning-Ning W, Zhi-Jiang Y, Lin Z, Yan C, Defang O, Ai-Ping L, Dong-Sheng C. ADMETlab: a platform for systematic ADMET evaluation based on a comprehensively collected ADMET database. J Cheminform. 2018;10:29. doi: 10.1186/s13321-018-0283-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamel A, Harriman S. Inhibition of cytochrome P450 enzymes and biochemical aspects of mechanism-based inactivation (MBI) Drug Discov Today Technol. 2013;10:e177–e189. doi: 10.1016/j.ddtec.2012.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Aljarrah A, Burney I, Al-moundhri M. Breast cancer (BM) article. Oman Med J. 2019;34:412–419. doi: 10.5001/omj.2019.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert SA, Jolma A, Campitelli LE, Das PK, Yin Y, Albu M, Chen X, HughesWeirauch TJM. The human transcription factors. Cell. 2018;172:660–665. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lennernäs H. Clinical pharmacokinetics of atorvastatin. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2003;42:1141–1160. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200342130-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Q, Gao Y, Xu P, Li K, Xu X, Gao J, Qi Y, Xu J, Yang Y, Song W, He X, Liu S, Yuan X, Yin W, He Y, Pan W, Wei L, Zhang J. Atorvastatin inhibits breast cancer cells by downregulating PTEN/AKT pathway via promoting ras homolog family member B (RhoB) BioMed Res Int. 2019;2019:1–15. doi: 10.1155/2019/3235021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng Y, Wang Y, Tang N, Sun D, Lan Y, Yu Z, Zhao X, Feng L, Zhang B, Jin L, Yu F, Ma X, Lv C. Andrographolide inhibits breast cancer through suppressing COX-2 expression and angiogenesis via inactivation of p300 signaling and VEGF pathway. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2018;37:1–14. doi: 10.1186/s13046-018-0926-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC, Ferrin TE. UCSF Chimera—a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem. 2004;25(13):1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prashantha Kumar BR, Soni M, Bharvi Bhikhalal U, Kakkot IR, Jagadeesh M, Bommu P, Nanjan MJ. Analysis of physicochemical properties for drugs from nature. Med Chem Res. 2010;19:984–992. doi: 10.1007/s00044-009-9244-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ruf W, Yokota NSF. Tissue factor in cancer progression and angiogenesis. Thromb Res. 2010;125:S36–38. doi: 10.1016/S0049-3848(10)70010-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segall MD, Greene N. Finding the rules for successful drug optimisation. Drug Discov Today. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2014.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shadap A, Pais M, Prabhu A. A descriptive study to assess the knowledge on breast cancer and utilization of mammogram among women in selected villages of udupi district, Karnataka. Nitte Univ J Heal Sci. 2019;4:84–87. [Google Scholar]

- Sheikhpoor M. Immunotherapy in breast cancer Immunotherapy in breast cancer. Clin Cancer Investig J. 2019 doi: 10.4103/ccij.ccij. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singh JK, Simões BM, Clarke RB, Bundred NJ. Targeting IL-8 signalling to inhibit breast cancer stem cell activity. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2013;17:1234–1241. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2013.835398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talib WH, Al-noaimi M. A new acetylacetone derivative inhibits breast cancer by apoptosis induction and angiogenesis inhibition. J Cancer Res Ther. 2018 doi: 10.4103/jcrt.JCRT. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsubura A, Lai Y-C, Kuwata M, Uehara N, Yoshizawa K. Anticancer effects of garlic and garlic-derived compounds for breast cancer control. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2011;11:249–253. doi: 10.2174/187152011795347441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vadodkar AS, Suman S, Lakshmanaswamy R, Damodaran C. Chemoprevention of Breast Cancer by Dietary Compounds Dietary Compounds. Anti-cancer Agent Med Chem. 2012;2012:1185–1202. doi: 10.2174/187152012803833008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Ge X, Tian X, Zhang Y, Zhang JPZ. Soy isoflavone: the multipurpose phytochemical (review) Biomed Rep. 2013;1:697–701. doi: 10.3892/br.2013.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T, Song Y, Wang H, Zhang J, Yu S, Gu Y, Chen T, Wang Y, Shen H, Jia G. Oxidative DNA damage and global DNA hypomethylation are related to folate deficiency in chromate manufacturing workers. J Hazard Mater. 2012;213–214:440–446. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2012.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaghoubi A, Khazaei M, Hasanian SM, Avan A. Bacteriotherapy in breast cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:1–21. doi: 10.3390/ijms20235880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yusof I, Segall MD. Considering the impact drug-like properties have on the chance of success. Drug Discov Today. 2013;18:659–666. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2013.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Wang K, Lin G, Zhao Z. Antitumor mechanisms of S-allyl mercaptocysteine for breast cancer therapy. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2014;14:1–12. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-14-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu T, Wang DX, Zhang W, Liao XQ, Guan X, Bo H, Sun JY, Huang NW, He J, Zhang YK, Tong JLC. Andrographolide protects against LPS-induced acute lung injury by inactivation of NF-kappaB. PLoS ONE. 2013;2:e56407. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H, Zhu G, Xu Y, Huang G. Bioscience reports: this is an accepted manuscript, not the final version of record. You are encouraged to use the Version of Record that, when published, will replace this version. The most up-to-date version is available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1042/B. Biosci Rep. 2018;2018:7. doi: 10.1042/BSR20180738. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zucchetti B, Shimada AK, Katz A, Curigliano G. The role of histone deacetylase inhibitors in metastatic breast cancer. Breast. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2018.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.