Abstract

The sustainable production of chemicals from non-petrochemical sources is one of the greatest challenges of our time. CO2 release from industrial activity is not environmentally friendly yet provides an inexpensive feedstock for chemical production. One means of addressing this problem is using acetogenic bacteria to produce chemicals from CO2, waste streams, or renewable resources. Acetogens are attractive hosts for chemical production for many reasons: they can utilize a variety of feedstocks that are renewable or currently waste streams, can capture waste carbon sources and covert them to products, and can produce a variety of chemicals with greater carbon efficiency over traditional fermentation technologies. Here we investigated the metabolism of Clostridium ljungdahlii, a model acetogen, to probe carbon and electron partitioning and understand what mechanisms drive product formation in this organism. We utilized CRISPR/Cas9 and an inducible riboswitch to target enzymes involved in fermentation product formation. We focused on the genes encoding phosphotransacetylase (pta), aldehyde ferredoxin oxidoreductases (aor1 and aor2), and bifunctional alcohol/aldehyde dehydrogenases (adhE1 and adhE2) and performed growth studies under a variety of conditions to probe the role of those enzymes in the metabolism. Finally, we demonstrated a switch from acetogenic to ethanologenic metabolism by these manipulations, providing an engineered bacterium with greater application potential in biorefinery industry.

Keywords: syngas, acetogen, metabolic engineering, CO2 fixation, Clostridium ljungdahlii, autotrophic

Introduction

Acetogenic bacteria utilize the Wood-Ljungdahl pathway (WLP) to non-photosynthetically fix inorganic carbon into acetyl-CoA, which is then converted into products, normally acetate and to a lesser extent, ethanol. Acetate production is an important feature of acetogenic metabolism. In Clostridium ljungdahlii, a model acetogen, acetate formation primarily occurs sequentially with the conversion of acetyl-CoA to acetyl-P via phosphotransacetylase (PTA) and then from acetyl-P to acetate via acetate kinase (ACK), with the ACK step generating ATP (Köpke et al., 2010). Acetate generation is important for ATP formation, as acetogens have low ATP budgets because they survive on the “thermodynamic limit of life”, on a small free energy change (Schuchmann and Müller, 2014).

Based on genome information and published data, C. ljungdahlii is believed to make ethanol from acetyl-CoA via two established mechanisms: aldehyde ferredoxin oxidoreductase (AOR) and bifunctional aldehyde/alcohol dehydrogenase (AdhE) (Köpke et al., 2010; Leang et al., 2013). AOR catalyzes the reversible conversion of acetate to acetaldehyde, with ferredoxin as the electron acceptor/donor. AdhE is a bifunctional enzyme, catalyzing the reversible conversion of acetyl-CoA to acetaldehyde, then to ethanol, using NAD(P)H as the electron donors.

Acetogens have been studied for their ability to generate value-added products from either syngas alone or in conjunction with sugar for increased carbon yield (Köpke et al., 2010; Jones et al., 2016). Many of these value-added products are derived from acetyl-CoA, which is generated from the WLP and glycolysis and serves as a primary intermediate in central carbon metabolism. Thus, it would be useful to understand the metabolism around this acetyl-CoA node to help guide metabolic engineering efforts.

Pta is the most obvious target, as it is the first and direct step to making acetate from acetyl-CoA. C. ljungdahlii pta (CLJU_c12770) has been targeted in three studies via gene disruption, CRISPR interference, and CRISPR/Cas9, but in all cases it was ambiguous what was happening. In the gene disruption study of pta, pta was replaced with a butyrate pathway that could have side reactions to generate acetate (Ueki et al., 2014). In the CRISPR interference study, knockdown of pta was incomplete and did not show an obvious growth phenotype leaving open the possibility that leaky expression was responsible for acetate production (Woolston et al., 2018). In the CRISPR/Cas9 study, the pta deletion strain growth data was only characterized vs. the wild type on syngas, showing no significant growth after 96 h or characterization of heterotrophic growth (Huang et al., 2016). High yields of acetate remained in strains targeting pta, suggesting that alternative pathways may be important for acetate production. Studies of acetyl-CoA metabolism suggest that there may be multiple important enzymes and pathways utilizing acetyl-CoA (Ueki et al., 2014; Whitham et al., 2015; Huang et al., 2016). Thus, we set out to delete pta and other key genes to understand their roles in metabolism and product formation.

Materials and Methods

Microbial Strains and Media Composition

Clostridium ljungdahlii DSM 13528 was acquired from The Leibniz Institute DSMZ (Braunschweig, Germany). Routine growth was performed in YTF media (10 g L–1 yeast extract, 16 g L–1 Bacto tryptone, 4 g L–1 sodium chloride, 5 g L–1 fructose, 0.5 g L–1 cysteine, pH 6) at 37°C with a N2 headspace. Routine manipulations and growth were performed in a COY (Grass Lake, MI) anaerobic growth chamber, flushed with 95% N2 and 5% H2 and maintained anaerobic by palladium catalyst.

For growth and fermentation characterization, cells were grown anaerobically in PETC 1754 media (ATCC) with sodium sulfide omitted. The gas pressure was at 1 atm, and the headspace was flushed with N2 unless indicated otherwise. Cells were grown in 18 × 150 mm Balch tubes (approximate total volume of 29 mL) crimped shut with 5 mL of PETC, with fructose, CO, or H2 added as described, standing upright in a 37°C incubator, shaking at 250 RPM. All fermentation data shown was the result of three replicates. Media components were supplied by Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO), while gases were > 99% purity, supplied by Airgas (Radnor Township, PA).

Escherichia coli strains were acquired from New England Biolabs (NEB) (Ipswich, MA). NEB 10-beta was utilized for general molecular purposes and plasmid propagation, while E. coli strain NEB Express was used for plasmid preparation for transformation into C. ljungdahlii due to methylation compatibility (Leang et al., 2013).

Molecular Techniques

Standard molecular techniques were used with enzymes from NEB. For routine PCR and cloning, Phusion polymerase was used to create and amplify fragments. For PCR screening the genetic loci of target genes, LongAmp polymerase was used. The ladder used was 1 kb Opti-DNA Marker from Applied Biological Materials (Vancouver, Canada). To generate new constructs, DNA was ligated together using Gibson assembly (NEB).

Plasmids from the pMTL80000 modular system from Chain Biotech (Nottingham, United Kingdom) were used to generate the constructs transformed into C. ljungdahlii. The original construct with Cas9 targeting pta was acquired from the original paper’s author describing the Cas9 system in C. ljungdahlii and ligated into pMTL83151 to generate the pta deletion construct (Huang et al., 2016). The plasmids were retargeting accordingly by ligating the new guide RNA and homology arms via PCR overlap extension (plasmids and primers are listed in Supplementary Table S1).

Complement plasmid for the aor2 and pta/ack were created using HiFi assembly (NEB) as follows. Gene fragments were gel purified from PCR amplification using Phusion DNA polymerase and the primers stated in Supplementary Table S1. pMTL83151 was cut using NotI and gel purified. Purified gene fragments and NotI cut pMTL83151 were assembled using HiFi assembly following the manufacturer’s instructions. Resulting colonies were screened with the primers used to make the gene fragments. Positive colonies were grown overnight, and plasmids purified using Monarch plasmid miniprep kit (NEB). Confirmation of complete plasmids was confirmed by whole plasmid sequencing by MBH DNA Core (Cambridge, MA).

Electrocompetent Cell Preparation and Transformation Protocol

Transformation protocols were similar to previously reported conditions (Leang et al., 2013). Briefly, C. ljungdahlii was grown on YTF with 40 mM DL-Threonine to early log phase (0.2–0.7), harvested and washed with ice cold SMP buffer (270 mM sucrose, 1 mM MgCl2, 7 mM sodium phosphate, pH 6), then resuspended in SMP buffer with 10% (dimethyl sulfoxide) DMSO and frozen at −80°C until use for transformation.

Electroporation was performed in a COY chamber with a Bio-Rad (Hercules, California) Gene Pulser Xcell electroporator under the following conditions: 25 μL cells were mixed with 2–10 μg of DNA in a 1 mm cuvette, pulsed 625 kV with resistance at 600 Ω and a capacitance of 25 μF. They were then resuspended in 5 mL of YTF and recovered overnight at 37°C. Cells were then plated in 1.5% agar YTF with thiamphenicol (Tm) at a final concentration of 10 μg/mL, which was Tm concentration used for general propagation. Typically, colonies appeared between 3 and 7 days after plating.

Generating and Validating Deletion Strains

To generate the plasmids targeting pta (CLJU_c12770) NC_014328.1 (1376316.1377317), we received the pta targeting Cas9 fragment described from Huang et al. (2016) and recreated the pta deletion vector by cloning in the fragment via restriction cloning into pMTL83151. Subsequent aor2 (CLJU_c20210) (2192715.2194538), and adhE1/adhE2 (CLJU_c16510/CLJU_c16520) (1791269.1793881/1794033.1796666), Cas9 deletion constructs were generated with the pta targeting vector as a backbone, using PCR to change gene targeting, similar to previously reported protocols (Huang et al., 2016). For the aor1 (CLJU_c20110) (2179645.2181468) deletion, the original promoter driving cas9 was replaced with a riboswitch-linked promoter (pbuE, P = 8 bp) activated by 2-aminopurine (2-AP) at 2 mM (Marcano-Velazquez et al., 2019). These strains were dilution plated on YTF agar with Tm and 2-AP and allowed for grow until colonies appeared (around 1 week). Once colonies appeared, they were individually picked, and PCR screened to isolate bacteria with successful genetic editing. To cure the plasmid and restore sensitivity to Tm, these strains were serially transferred 2 times in non-selective media and dilution plated on YTF agar for single colony isolation, then tested for sensitivity to Tm and PCR screened for loss of the Tm resistance gene.

Analytical Techniques

Fermentation liquid samples of 150 μL were extracted by syringe, filtered using Costar Spin-X 0.45 μm filters (Corning, Corning, NY), and stored at −20°C until the experiments completed. Fermentation products in the liquid phase (acetate, ethanol, and 2,3 butanediol) were measured by high-performance liquid chromatography on a 1,200 series Agilent (Santa Clara, CA) with an Aminex HPX-87H column using a Micro Guard Cation H Cartridge, at 55°C with 4 mM H2SO4 mobile phase, as previously described (Marcano-Velazquez et al., 2019). Optical density was measured at 600 nm using a Milton Roy (Ivyland, PA) Spectronic 21D.

Biochemical Assays

Wild type and derived cultures were grown in 50 mL PETC medium with 5 g/L fructose and harvested at mid log phase (0.3–0.7 OD600) by centrifugation at 4,000 g for 10 min. The supernatants were discarded, and pellets were frozen at −80°C for future use. Cell pellets were resuspended in 200 μL phosphate buffer (pH 7.6) which contained 25 mg/ml lysozyme and 10 mM dithiothreitol. Resuspended cells were added to a screwcap tube contained acid washed glass beads (Sigma-Aldrich, United States) and lysed using a Tissuelyser II (Qiagen, Germany) at a frequency of 30 1/s for 2 min. Lysed cells were subsequently centrifuged at 17,000 g for 2 min. The resulting supernatant was extracted and stored in anaerobic vials at –80°C for future use. Protein concentration was determined using Bradford reagent (Sigma-Aldrich) following the manufacturer’s instructions using a Tecan infinite M200 pro plate reader (Tecan Life Sciences, Switzerland). All assays are reported as specific activities (μmol min–1 mg–1) and were performed in triplicate in the anaerobic COY chamber at 27°C. Enzyme assay mixtures without cell free extract were used to track baseline changes in absorbance.

To test Pta activity in the wild type and derived mutants, the procedure employed was based on formation of thioester bond formation of acetyl-CoA, following the change in absorbance at 233 nm using a molar extinction coefficient of 4,360 M–1 cm–1 (Klotzsch, 1969). In short, 200 μL of a 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.6) containing 1.6 mM glutathione, 0.43 mM coenzyme-A (CoA), 7.23 mM acetyl-phosphate, and 13.3 mM ammonium sulfate was added to 1 μL of cell free extract, and monitored for 233 nm change in a NanoDrop One from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA) at 15 s intervals for 4 min.

To test Aor activity in the wild type and derived mutants, the procedure employed was based on benzyl viologen reduction (Heider et al., 1995). In short, 200 μL of a 100 mM phosphate buffered mix (pH 7.6) containing 1.6 mM benzyl viologen, 1 mM acetaldehyde and 1 mM dithiothreitol was added 10 μL of cell free extract in a flat bottom 96 well plate. Reduction of benzyl viologen was measured at 600 nm using a molar extinction coefficient of 7,400 M–1 cm–1 using BioTek Synergy Neo2 plate reader (BioTek Instruments, United States) at 10 s intervals for 5 min.

To test both Adh and Aldh activity in the wild type and derived mutants, enzymatic reduction of NAD+/NADP+ was employed based on previous published methods (Lo et al., 2015). For the Adh assay, 200 μL of a 100 mM Tris-HCL (pH 7.8) buffer mixture containing 10 mM ethanol, 1 mM NAD+ or 1 mM NADP+ and 1 mM dithiothreitol was added to 10 μL of cell free extract in a flat bottom 96 well plate. Reduction of NAD+ or NADP+ was measured at 340 nm using BioTek Synergy Neo2 plate reader at 10 s intervals for 5 min. For the Aldh assay, 200 μL of 100 mM Tris-HCL (pH 7.8) buffer mixture containing 0.43 mM CoA, 1 mM NAD+ or 1 mM NADP+, 10 mM acetaldehyde and 1 mM dithiothreitol was added to 10 μL of cell free extract in a flat bottom 96 well plate. Reduction NAD(P)+ was calculated using a molar extinction coefficient of 6,220 M–1 cm–1.

Results

Generation and Characterization of Phosphotransacetylase Gene(pta) Negative Strain

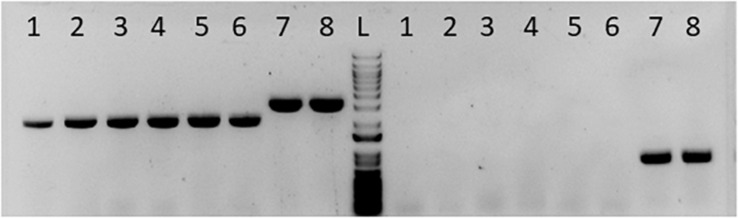

To determine the role of pta in acetate formation, we utilized Cas9 to delete pta. Cas9 can be utilized to generate markerless deletion strains, which is useful for generating strains with multiple deletions when selective markers are limited. Because of the importance of pta to acetogenic metabolism and as a target for genetic engineering for increased product formation, we acquired the Cas9 pta deletion cassette and with which created the pta deletion strain (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Gel picture showing successful deletion of pta in C. ljungdahlii. Columns labeled 1–6 to the left of the ladder “L” were presumptive pta deletion colonies for single colony purification. Column 7 was wild type DNA mixed with the pta deletion plasmid. Column 8 is the wild type DNA alone. The set of lanes to the left of the ladder “L” was PCR amplifying the pta region. Columns 1–6 show a smaller pta region, indicating loss of pta at that region in the genome. Columns 7 and 8 show the wild type band size. The set of lanes to the right of the ladder (L) was PCR amplifying a region inside pta. Columns 1–6 show no fragment amplified, indicating no detectable pta in those colonies. Columns 7 and 8 show the fragment of pta in unedited DNA.

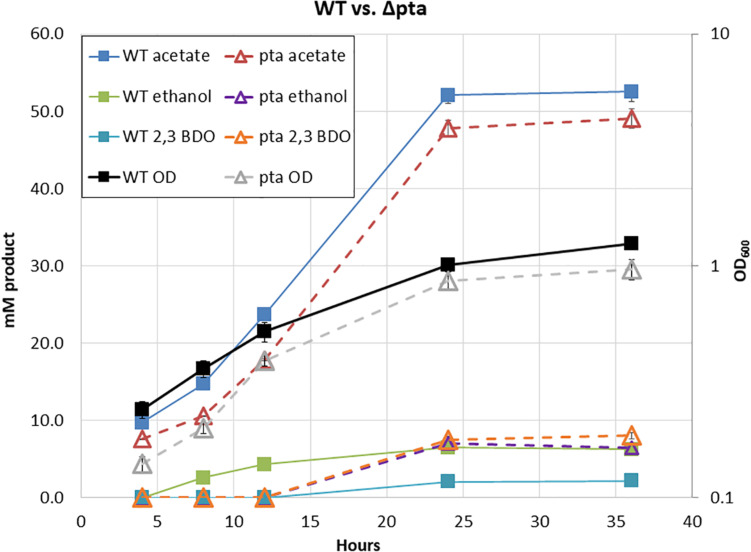

Surprisingly, in our initial characterization of heterotrophic growth, there was little initial difference between the Δpta and wild-type strain (Figure 2). The wild type and Δpta strain grew at similar rates and produced a similar amount of products. Both the wild type and Δpta strain produced high levels of acetate during heterotrophic growth (51 vs. 47 mM) and similar amounts of ethanol (∼6 mM). The only notable difference is that the Δpta strain produced markedly more 2,3 butanediol (2,3 BDO) than the wild-type strain (8 vs. 2 mM). The carbon/electron recovery from fermentation products was 0.79/0.85 for the wild type and 0.86/0.97 for the Δpta strain.

FIGURE 2.

Heterotrophic growth and fermentation products of C. ljungdahlii wild type and the pta deletion strain on PETC with 5 g/L fructose. Wild type is marked with solid lines and squares, while Δpta is marked dashed lines with hollow triangles. Growth rate, OD600, and fermentation products are similar across the duration of the experiment.

Predictions from the metabolic model developed by Nagarajan et al. (2013) suggested loss of pta would redirect flux toward ethanol formation through AdhE, yet we observed no increase in ethanol. We reasoned that if acetyl-CoA was no longer being directed toward acetate via acetyl-P, perhaps it was through an acetaldehyde intermediate via Aldh and AOR. If this was the case, NADH would be consumed, ferredoxin would be reduced, and acetaldehyde would be oxidized to acetate. The increased reduced ferredoxin (Fdred) could then be utilized by the WLP to fix the CO2 evolved by glycolysis. Redox consumption via the WLP may be preventing ethanol formation.

Creation and Characterization of Δpta Derivative Strains

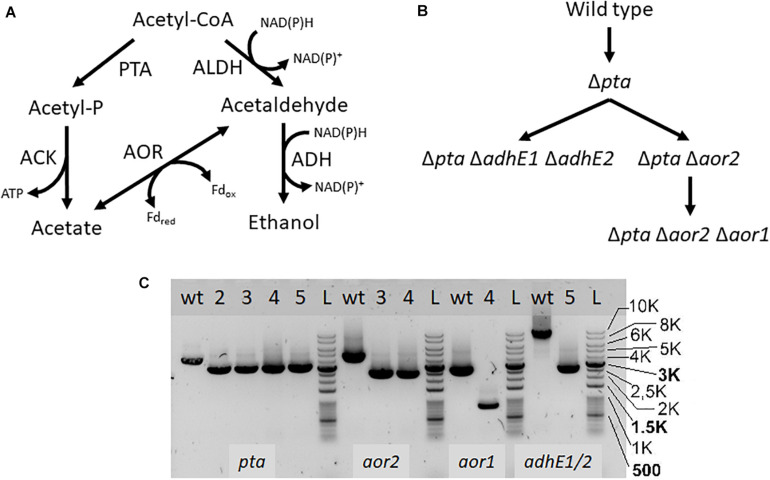

If pta is not essential for acetate formation, how is acetate enzymatically produced in the Δpta strain? There are a number of enzymes identified that can influence acetyl-CoA that may change product formation, in particular AOR and the AdhE. We therefore targeted these genes using CRISPR/Cas9 to understand their metabolic function (Figure 3). We show deletion of these genes using PCR to amplify external target gene regions (Figure 3C) and confirmed loss of the genes by PCR and sequencing (Supplementary Figures S1, S2).

FIGURE 3.

Acetyl-CoA metabolism and creation of deletion mutants. PTA, phosphotransacetylase; ACK, acetate kinase; ALDH/ADH, aldehyde/alcohol dehydrogenase; AOR, aldehyde ferredoxin oxidoreductase (A) Map of acetyl-CoA metabolism with metabolites, cofactors, and enzyme reactions. (B) Strain map showing lineage of deletions made. (C) PCR confirmation of deletion strains. Primers were used to amplify the genomic regions of pta, aor2, aor1, adhE1, and adhE2, to confirm genomic deletions. Lanes labeled with “wt” is wild type DNA control, while lanes with “L” are the DNA ladder. Lanes with numbers correspond to the following strains: 2- Δpta, 3- Δpta Δaor2, 4- Δpta Δaor2 Δaor1, 5- Δpta ΔadhE1 ΔadhE2. The lower bands in the lanes correspond to expected gene deletions targeted by the homology arms.

AOR catalyzes the fully reversible interconversion of acetate and acetaldehyde with ferredoxin as the electron donor or acceptor. Although reversible, AOR’s physiological directionality is of question but could be the source of acetate, if acetaldehyde is derived from acetyl-CoA (Ueki et al., 2014; Richter et al., 2016; Nissen and Basen, 2019). Transcriptomics studies under heterotrophic and autotrophic conditions have shown that aor2 (CLJU_c20210) is the predominantly expressed AOR (2085 heterotrophic/612 autotrophic FPKM), vs. aor1 (CLJU_c20110) (10 heterotrophic/7 autotrophic FPKM) (Nagarajan et al., 2013). CRISPRi targeting aor2 showed an effect on fermentation products, although only while targeting pta as well (Woolston et al., 2018). Thus, we decided to first target aor2 using CRISPR/Cas9 in the Δpta strain background.

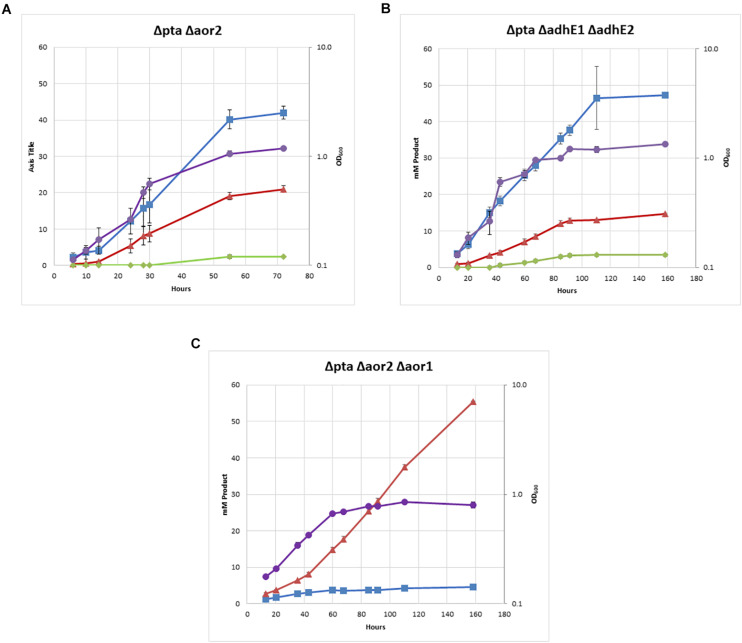

The double Δpta Δaor2 strain under heterotrophic conditions produced much more ethanol than the wild type or parent Δpta strains. Whereas ethanol was produced in trace amounts in both those strains with an acetate to ethanol ratios of 9:1 (Figure 2), the Δpta Δaor2 strain consistently produced acetate to ethanol in a 2:1 ratio (Figure 4A). This suggests that aor2 directionality under heterotrophic growth at pH 6.0 is in the acetate forming direction. It also suggests aor2 was important for reduced ferredoxin production and/or acetaldehyde oxidation and prevented ethanol formation under heterotrophic conditions. In contrast to the Δpta strain, the Δpta Δaor2 strain under these conditions produced similar 2,3 BDO (2 mM) to the wild type, despite an increase in the production of ethanol. The carbon/electron recovery from fermentation products was 0.82/0.97 for the Δpta Δaor2 strain.

FIGURE 4.

Heterotrophic growth and fermentation products of strains on PETC with 5 g/L fructose. Acetate in blue squares, ethanol in red triangles, 2,3-butanediol in green diamonds, OD600 in purple circles. (A) Δpta Δaor2, (B) Δpta ΔadhE1 ΔadhE2, and (C) Δpta Δaor2 Δaor1.

Next, we decided to target the bifunctional alcohol/aldehyde dehydrogenases (adhE) genes in the Δpta strain. Bifunctional alcohol/aldehyde dehydrogenases catalyze the conversion of acetyl-CoA to acetaldehyde to ethanol using 2 NAD(P)H as electron donors, and could be the source of acetaldehyde substrate for AOR. These genes are also considered important for ethanol production in other Clostridia, so the production of both acetate and ethanol could be affected (Cooksley et al., 2012; Lo et al., 2015). There are two annotated adhE genes in the genome, adhE1 and adhE2 (CLJU_c16510 and CLJU_c16520), which are colocalized in the genome. It was previously shown that disruption of adhE1 but not adhE2 resulted in a decrease in ethanol when grown on fructose (Leang et al., 2013). Omics studies have also shown that this is probably because adhE1 is the predominantly expressed AdhE (166 heterotrophic/0.1 autotrophic FPKM) vs. adhE2 (5.3 heterotrophic/0 autotrophic FPKM) (Nagarajan et al., 2013). Due to colocalization of adhE1 and adhE2, we decided to simultaneously target both to create the strain Δpta ΔadhE1 ΔadhE2 (Figure 3C). We targeted adhE1 using the guide RNA and supplied recombination regions downstream of the adhE2 for repair. The Δpta ΔadhE1 ΔadhE2 strain showed increased ethanol formation (15 mM) over the parent Δpta strain (∼5 mM), suggesting that there are additional proteins involved in ethanol formation, perhaps from other annotated acetaldehyde/alcohol dehydrogenases (Figure 4B; Whitham et al., 2015). The acetate amount is comparable to that of the Δpta parental strain. The carbon/electron recovery from fermentation products was 0.83/0.94 for the Δpta ΔadhE1 ΔadhE2 strain.

Finally, we targeted aor1 in the Δpta Δaor2 strain. Whether aor1 had an influence on metabolism in C. ljungdahlii was unclear in literature. Low detection of aor1 was shown in a previous study (10.4 heterotrophic/6.5 autotrophic FPKM) (Nagarajan et al., 2013), although there were reports of increased aor1 under some conditions and variability in some reports (Whitham et al., 2015; Richter et al., 2016; Aklujkar et al., 2017). To target aor1 we decided to test the original Cas9 construct vs. a riboswitch inducible Cas9 recently developed (Marcano-Velazquez et al., 2019). Working with Cas9 construct for the previous deletions was difficult due to several reasons. In E. coli, the plasmid was unstable and often produced truncated plasmids, and did not readily produce concentrated plasmid. In C. ljungdahlii transformation efficiencies were low due to constitutive expression of Cas9, which would only allow growth of colonies that had both taken up the plasmid and undergone successful genome editing (Huang et al., 2016). Coupling of an inducible riboswitch with Cas9 has shown improved genomic editing in other Clostridia (Cañadas et al., 2019). Switching the original thiolase promoter with the riboswitch inducible promoter (the 2-AP riboswitch linked with the Cthe_2638 promoter, pbuE, P = 8 bp) resulted in improved performance in E. coli and allowed comparable transformation efficiency of non-Cas9 plasmids, while we were unable to get successful transformants of the constitutive Cas9 construct targeting aor1. After getting successful colonies, we induced Cas9 using 2-AP and plated cells on 2-AP plates. Five colonies were isolated and tested, with two showing the edited aor1 genotype.

The Δpta Δaor2 Δaor1 strain showed several distinct features compared to Δpta Δaor2 (Figure 4C). There was a dramatic decrease in acetate and increase in ethanol, with a ∼85% selectivity for ethanol compared to acetate. No 2,3 BDO was detected. The strain also grew much slower than other strains, including Δpta Δaor2, but was eventually able to consume all the fructose. The carbon/electron recovery from fermentation products was 0.72/1.05 for the Δpta Δaor2 Δaor1 strain. To confirm the acetate phenotype, the Δpta Δaor2 Δaor1 strain was retransformed with the control plasmid or a plasmid expressing pta/ack or aor2, which resulted in increased acetate vs. Δpta Δaor2 Δaor1 with the control plasmid (Supplementary Figure S3). The plasmid complementation did not completely restore acetate production, but that may be due to inferior expression from plasmids (Leang et al., 2013).

Enzyme Assays on Strains

To examine changes brought by targeted gene deletions, we assayed strains for enzymatic activity based on the targeted genes. First, we measured phosphotransacetylase activity of the wild type and Δpta strain and confirmed loss of detectable phosphotransacetylase activity, measuring wild type specific activity of 1.47 vs. < 0.01 for the Δpta strain. Next, we measured the activity of AOR, Aldh, and Adh (Table 1). For AOR activity, we measured relatively low activity in the wild type strain, which increased fivefold in the Δpta strain. Interestingly, the Δpta Δaor2 strain had the highest detectable AOR activity, while the Δpta Δaor2 Δaor1 strain had the lowest activity of the Δpta derivative strains, but still significantly higher activity than the wild type. For Aldh NAD+ activity, we found that a large increase in the Δpta strain vs. the wild type, and a subsequent reduction in Aldh activity in the Δpta ΔadhE1 ΔadhE2, although still above wild type levels. For ADH activity, activities were low for wild type, Δpta, and Δpta ΔadhE1 ΔadhE2, although the highest activity was found in the Δpta ΔadhE1 ΔadhE2.

TABLE 1.

AOR, Adh, and Aldh cell free extract specific activity.

| BV AOR | NAD+ ADH | NADP+ ADH | NAD+ ALDH | NADP+ ALDH | |

| WT | 0.09 (0.00) | 0.01 (0.01) | 0.03 (0.01) | 0.01 (0.01) | 0.01 (0.01) |

| pta | 0.38 (0.02) | 0.01 (0.01) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.46 (0.01) | 0.01 (0.01) |

| pta aor2 | 0.47 (0.02) | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| pta aor2 aor1 | 0.31 (0.02) | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| pta adhE1 adhE2 | ND | 0.03 (0.01) | 0.01 (0.01) | 0.08 (0.01) | 0.01 (0.01) |

Cell free extract activities of acetaldehyde ferredoxin oxidoreductase, alcohol dehydrogenase, and aldehyde dehydrogenase, reported in μmol min–1 mg–1, measured as reduction of the electron acceptor. The top line lists the electron acceptor, either NAD(P)+ or benzyl viologen (BV). AOR, aldehyde ferredoxin oxidoreductase; ADH, alcohol dehydrogenase; ALDH, aldehyde dehydrogenase; ND, not determined. Standard deviation is in parenthesis. For all assays, n = 3.

Autotrophic Growth of Strains

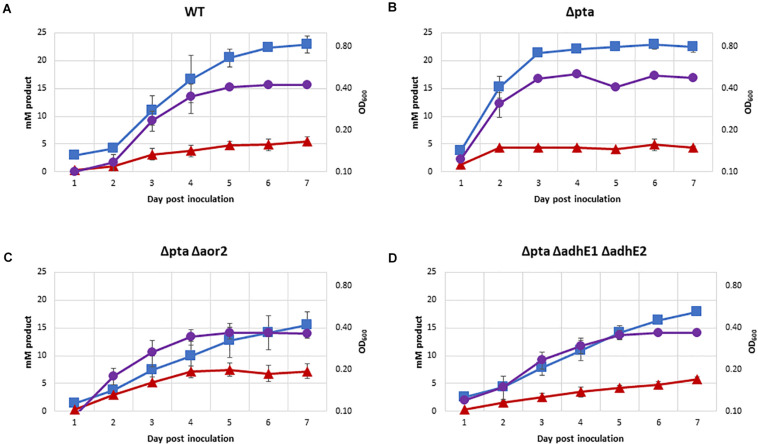

One of the most important predicted functions of Pta in C. ljungdahlii is to generate acetyl-P for ATP synthesis. The previous CRISPR/Cas9 study on the Δpta strain showed no significant growth on syngas (Huang et al., 2016). In contrast with previously data, we demonstrated robust growth of most strains on 100% CO in PETC media without sugar over a 7-day period (Figure 5), except for Δpta Δaor2 Δaor1 which did not grow (OD did not increase by more than 0.1 over 7 days). Acetate was the primary product formed in all strains, with Δpta Δaor2 having the least (16 mM) and wild type and Δpta the most (∼23 mM). Δpta Δaor2 had the most (7 mM) of ethanol formed, while the others had similar levels (∼5 mM). 2,3 BDO was not a significant product (<2 mM formed). Final OD of strains ranged between 0.35 and 0.48, with strains that generated more acetate having a higher OD.

FIGURE 5.

Growth and fermentation products of strains on PETC with 100% CO. Strains were grown over 7 days with fermentation products and growth monitored, with approximately a 5:1 headspace to liquid ratio. Acetate as blue squares, ethanol as red triangles, OD600 as purple circles. (A) Wild type, (B) Δpta, (C) Δpta Δaor2, and (D) Δpta ΔadhE1 ΔadhE2.

H2-Enhanced Mixotrophic Growth for Carbon Conversion

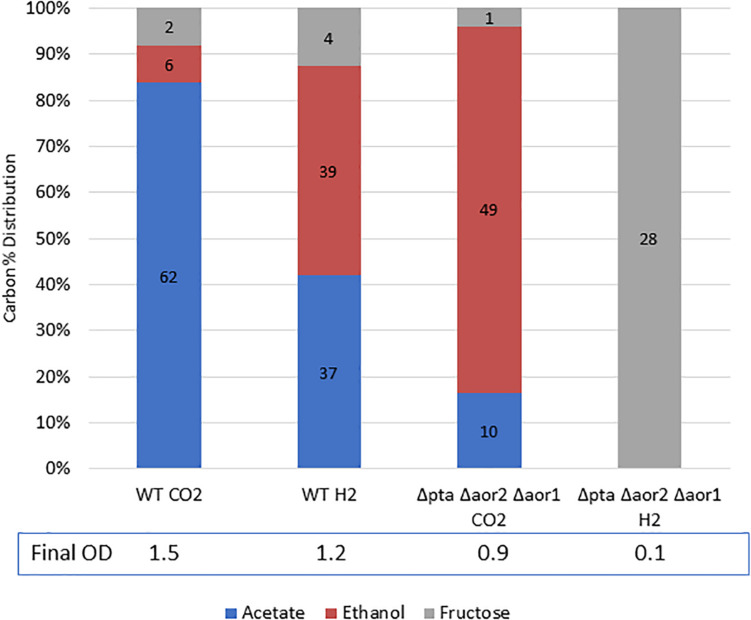

Traditional fermentation ethanol yields are limited to a theoretical 66% carbon yield due to loss of CO2 via decarboxylation when converting pyruvate to acetyl-CoA. Acetogens can overcome these limitations by simultaneously utilizing fructose and syngas in mixotrophic growth, allowing for capture of CO2 and conversion to acetyl-CoA (Jones et al., 2016). C. ljungdahlii was shown to be one of the best acetogens at syngas-enhanced mixotrophic growth as well as ethanol tolerance.

Since the Δpta Δaor2 Δaor1 was able to produce ethanol at a high yield heterotrophically, we were interested in its performance under H2-enhanced mixotrophic growth compared to the wild type. Theoretically H2 could be used to capture lost CO2 from glycolysis and supply reducing power to reduce acetyl-CoA to ethanol, resulting in a carbon yield increase on a per sugar basis. In a wild type strain, addition of H2 with growth on sugar was shown to shift fermentation products toward more ethanol (Jones et al., 2016).

While the Δpta Δaor2 Δaor1 grew heterotrophically but not on CO alone, we wondered whether the strain could utilize fructose and H2 simultaneously to get a larger ethanol yield than on fructose alone. To test this, we grew the wild type strain and the Δpta Δaor2 Δaor1 strain on 5 g/L fructose with either 100% H2 or 100% CO2 (as a control) in the headspace (Figure 6). After a week of growth, the wild type with CO2 or H2 and Δpta Δaor2 Δaor1 with CO2 consumed most of the sugar, while the Δpta Δaor2 Δaor1 with H2 failed to grow at all. Based on the fructose added, the carbon recovery of the wild type strain was ∼90% in CO2 and ∼105% in H2, while only 75% Δpta Δaor2 Δaor1 in CO2.

FIGURE 6.

Mixotrophic growth and fermentation products of wild type vs. Δpta Δaor2 Δaor1 on PETC with 5 g/L fructose with either 100% CO2 or 100% H2. Strains were grown on 5 g/L (28 mM) fructose with the indicated headspace gas (CO2 or H2). Carbon distribution of fermentation products/residual fructose is indicated by bar chart%, while the number label is mM amount after 5 days. The OD600 after 5 days is indicated at the bottom.

Discussion

Acetate formation is a key characteristic of acetogens, which utilize the WLP to fix CO2 and produce primarily acetate. Surprisingly under a wide variety of conditions in C. ljungdahlii, Pta is unnecessary for acetate formation, despite being normally understood as a critical enzyme for ATP production and acetate formation. What are the underlying mechanisms and enzymes that drive C. ljungdahlii metabolism? There are a few models that attempt to predict C. ljungdahlii metabolism. Nagarajan’s genome-scale model suggested that deleting pta and ack would force ethanol production rather than acetate, but this model was missing the AOR reaction functioning in the acetate forming direction (Nagarajan et al., 2013). Richter et al. (2016) suggested that thermodynamics, rather than enzyme expression, is a driving force behind the product formation in C. ljungdahlii, and that AOR is an important arbiter in determining acetate:ethanol ratios. We provide evidence that model has value. Despite pta as one of the most highly expressed genes and an important contributor to ATP/acetate formation, the Δpta and wild-type strain had very similar product profiles. Richter et al. (2016), however, suggested that a pta/ack knockout strain would not produce acetate, but we have shown high acetate yield without pta. We believe this is through the activity of AOR. AOR has been proposed to be important for metabolism in C. ljungdahlii, and aor2 has been found to be expressed under both heterotrophic and autotrophic growth conditions (Nagarajan et al., 2013; Ueki et al., 2014; Whitham et al., 2015; Richter et al., 2016; Aklujkar et al., 2017; Woolston et al., 2018; Zhu et al., 2020). What is the purpose of AOR in acetogens? There are several potential functions: ferredoxin reoxidation under growth on CO, detoxifying short-chain fatty acids when pH is low, and maximizing ATP yield during autotrophic ethanol production (Mock et al., 2015; Richter et al., 2016; Liew et al., 2017).

We provide evidence that a potential function of AOR may be to supply ferredoxin via an acetaldehyde intermediate from acetyl-CoA. Although in acetogens, AOR was thought to primarily function in the reduction of carboxylic acids, oxidation of aldehydes may be an important feature as well. Balancing redox cofactors is likely to be an important part of C. ljungdahlii metabolism and AOR could be a method of indirectly “upgrading” electrons from NAD(P)H (E0’ = −320 mV) to Fdred (E0’ = −400 mV). The directionality of AOR is partially determined by pH, as AOR is only active on protonated short-chain fatty acids (i.e., acetic acid, pKa = 4.7) (Huber et al., 1995; Napora-Wijata et al., 2014). A higher pH would drive the reaction toward reducing ferredoxin as acetic acid would be deprotonated to acetate. High expression of AORs has been shown in both heterotrophic and autotrophic conditions, despite high yields of acetate, so even in Pta and Ack competent strains AOR may be converting acetaldehyde to acetate. This process would provide redox flexibility and ATP through the conversion of Fdred to NAD(P)H via the NADH ferredoxin:NADP+ oxidoreductase and proton-translocating ferredoxin:NAD+ oxidoreductase, which would then be consumed by the electron demanding WLP. Indeed, in many of our Δpta strains, growth and product formation was like the wild type and only appeared to be severely compromised when both aor1 and aor2 were also deleted (Figure 4C). Interestingly, enzyme assays in the Δpta strain of both NAD+-linked Aldh and AOR were significantly higher than the wild type strain, suggesting that this pathway is the main route of acetate formation in this strain. Even with loss of aor2, we detected the highest AOR activity in the Δpta Δaor2 strain (Table 1). It should be noted that the AOR assay used benzyl viologen rather than ferredoxin, and thus these activities may not be true indicators of AOR activity. AOR genes are widely distributed among acetogens and could serve a similar role in those organisms (Nissen and Basen, 2019). In the closely related Clostridium autoethanogenum, aor1, and aor2 were deleted, and it was shown that loss of aor2, but not aor1, improves autotrophic ethanol production. In the same study, it was also shown that loss of these genes prevents reduction of carboxylic acids (Liew et al., 2017). It is unknown why there is a difference in the response between C. ljungdahlii and C. autoethanogenum, but potentially it was because the pta/ack pathway was functional in those strains. Pta and Ack are usually some of the highest detected enzymes, which points to their central role in acetate formation. In our Δpta derivative strains, AOR may be the only functional route to acetate, which may be a preferred product due to electron consumption by the WLP. It is still unknown why there are two genes and what factors drive their expression. Additionally, while these organisms are over 99% identical, there are significant differences in metabolism, substrate consumption, and product formation (Bruno-Barcena et al., 2013; Jones et al., 2016). Specific differences in the WLP enzymes include a uniquely truncated C. autoethanogenum acsA gene which could have a major effect on metabolism (Liew et al., 2016).

The Δpta Δaor2 Δaor1 strain shows slower heterotrophic growth. Why is this the case? The WLP is an electron demanding process and the formation of ethanol would potentially cause redox imbalance. Alternatively, if AOR “upgrading” of electrons is disabled, there may be a cofactor mismatch between electrons produced by glycolysis (Fdred and NADH) and demanded by the WLP. Electron requiring enzymes of the WLP require redox cofactors (i.e., NADPH, Fdred, and possibly NADH) in specific amounts. Fdred can be used to reduce NAD(P)+ through the activity of Rnf and Nfn, which has been detected in high activities, suggesting these interconversions are actively taking place.

The Δpta Δaor2 Δaor1 strain also showed no detectable autotrophic growth, even though ethanol formation through adhE is a net ATP positive process (Bertsch and Müller, 2015; Mock et al., 2015). We suspect that this is due to the regulation of adhE1, as adhE1 appears to be highly expressed under heterotrophic conditions but virtually undetectable in autotrophic conditions (Nagarajan et al., 2013). This makes sense as ethanol production through ADHE is much less ATP efficient than through AOR, but the underlying regulatory mechanism of adhE control is still unknown. Mixotrophic conditions of Δpta Δaor2 Δaor1 also showed no detectable growth. We think this may be due to CO/H2 inhibiting strong expression of adhE1, like on autotrophic growth. If this is the case, adhE1 regulation may not be an autotrophic mechanism per se, but rather in response to reducing gases or redox state, regardless of the presence of sugar. Alternatively, a recent study looking at C. autoethanogenum autotrophic growth suggests that ethanol formation through ADHE may be thermodynamically unfeasible under certain conditions and that AOR is important for energy generation and redox balance (Mahamkali et al., 2020). These factors could explain the lack of growth in the presence of syngas. Although there have been studies looking at heterotrophic, autotrophic, and mixotrophic growth, little is known about the mechanisms that govern the metabolism of these organisms. Since acetogenic metabolism is ATP and thermodynamically limited, there may be multiple mechanisms at work (Schuchmann and Müller, 2014; Molitor et al., 2017).

The Δpta ΔadhE1 ΔadhE2 strain raises several questions around ethanol and acetate formation in this organism. Despite loss of these highly expressed enzymes under heterotrophic conditions, loss of these enzymes increased ethanol formation and significant amounts of ethanol and acetate were formed. Acetate was still the primary product, which is probably from the active AORs in this strain, but ethanol was about 33% of the product formed. AdhE’s main function is probably the reversible conversion of acetyl-CoA to ethanol (and vice versa) and not acetaldehyde generation for AOR activity. AdhEs are known to form spirosomes, which are large structures believed to sequester the toxic acetaldehyde from the rest of the cell (Kim et al., 2019). However, the Δpta strain had higher Aldh activity than the Δpta ΔadhE1 ΔadhE2 strain, suggesting that these adhE genes may be important for Aldh activity, which has been seen in other Clostridia (Yao and Mikkelsen, 2010). Even with the loss of both adhE genes, the Δpta ΔadhE1 ΔadhE2 strain had some Aldh activity, and slightly higher Adh activity, which could explain the increased ethanol formation. This suggests the presence of other important aldehyde and alcohol dehydrogenases. There are many others annotated and expressed, but their function and importance are not well understood (Whitham et al., 2015). Other studies have pointed out other potential candidates that are highly expressed, but as we have shown for aor2 vs. aor1, expression levels under those studies may be deceptive for predicted metabolic effect. The metabolic effect of these enzymes change depending on the state of cells. For instance, during growth on syngas, ethanol can be both produced and consumed, which is dependent on both AdhE and AOR (Liu et al., 2020). Additionally, there are many potential redundant enzymes and their regulation is unknown, and while many of these genes are annotated as alcohol or aldehyde dehydrogenases, they may not be specific for acetaldehyde/ethanol (Tan et al., 2015). In general, we did not detect high Adh activity, which suggests a lack of highly expressed/active alcohol dehydrogenases. The leftover acetate in the Δpta Δaor2 Δaor1 fermentations could perhaps be formed from other annotated AORs or from ctf (Ueki et al., 2014; Whitham et al., 2015). While we noted strain differences in enzymatic activity, these assays were extremely limited. We did not test cells under different growth conditions or attempt to optimize enzymatic activity, and we used benzyl viologen as a proxy for ferredoxin. A more careful enzymatic study may be expected to find different results (Lo et al., 2015; Mock et al., 2015). It will be important to rigorously test enzymatic activity and identify responsible enzymes, for both metabolic engineering and fundamental understanding.

Understanding the underlying mechanisms of acetogen metabolism is important for engineering them for targeted chemical formation. Acetogens are being investigated for their autotrophic, heterotrophic, and mixotrophic growth capabilities to produce a wide variety of products with high carbon-conversion efficiency. We show that substrate level phosphorylation of ATP via pta is not required for robust growth on CO. This may be helpful when designing pathways for product formation, as ATP production via substrate level phosphorylation is not an absolute requirement and ATP production through proton motive force generated by Rnf is sufficient (and necessary) for autotrophic growth (Tremblay et al., 2013). We did not test autotrophic growth differences of the strains on H2/CO2, which is expected to have lower ATP yield than CO growth, but H2/CO2 growth is still expected to be ATP positive assuming acetate is formed (Mock et al., 2015).

Indeed, C. ljungdahlii has already been engineered to produce acetone, butanol, and butyrate (among many others), and acetate has been an ever-present product in those studies. We have successfully reduced acetate production by > 80% via targeted gene knockout, which should help inform further work in engineering new products in acetogens and increasing yield of desired products. In this work, we engineered C. ljungdahlii and improved yield of ethanol from ∼10% to over 80%. In the process, we clarified the role of several genes involved in acetyl-CoA metabolism and showed that substrate phosphorylation via pta is unnecessary for autotrophic growth on CO (Figure 5). We also identify gaps in our knowledge of acetogens and highlight important areas of study in acetogens for further research in both fundamental understanding and applied metabolic engineering.

Author’s Note

This work was authored by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory, operated by Alliance for Sustainable Energy, LLC, for the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) under Contract No. DE-AC36-08GO28308. Funding provided by DOE and Bioenergy Technology Office (BETO). The views expressed in the article do not necessarily represent the views of the DOE or the U.S. Government. The U.S. Government retains and the publisher, by accepting the article for publication, acknowledges that the U.S. Government retains a nonexclusive, paid-up, irrevocable, worldwide license to publish or reproduce the published form of this work, or allow others to do so, for U.S. Government purposes.

Data Availability Statement

All datasets generated for this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material.

Author Contributions

JL, P-CM, YG, and ZR led the research. JL and JH designed the experiments. JL, JH, JJ, CU, LM, and WX performed the experiments. JL, WX, and P-CM wrote the article. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was authored by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory, operated by Alliance for Sustainable Energy, LLC, for the US Department of Energy (DOE) under Contract No. DE-AC36-08GO28308. Funding provided by DOE and Bioenergy Technology Office (BETO). The views expressed in the article do not necessarily represent the views of the DOE or the US Government. The US Government retains and the publisher, by accepting the article for publication, acknowledges that the US Government retains a nonexclusive, paid-up, irrevocable, worldwide license to publish or reproduce the published form of this work, or allow others to do so, for US Government purposes.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was supported by the US Department of Energy (DOE) Bioenergy Technology Office (BETO) and National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) under Contract DEAC36-08-GO28308.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fbioe.2020.560726/full#supplementary-material

References

- Aklujkar M., Leang C., Shrestha P. M., Shrestha M., Lovley D. R. (2017). Transcriptomic profiles of clostridium ljungdahlii during lithotrophic growth with syngas or H 2 and CO 2 compared to organotrophic growth with fructose. Sci. Rep. 7 1–14. 10.1038/s41598-017-12712-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertsch J., Müller V. (2015). Bioenergetic constraints for conversion of syngas to biofuels in acetogenic bacteria. Biotechnol. Biofuels 8:210. 10.1186/s13068-015-0393-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruno-Barcena J. M., Chinn M. S., Grunden A. M. (2013). Genome sequence of the autotrophic acetogen clostridium autoethanogenum JA1-1 Strain DSM 10061, a producer of ethanol from carbon monoxide. Genome Announc. 1:e00628-13. 10.1128/genomeA.00628-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cañadas I. C., Groothuis D., Zygouropoulou M., Rodrigues R., Minton N. P. (2019). RiboCas: a universal CRISPR-based editing tool for clostridium. ACS Synth. Biol. 8 1379–1390. 10.1021/acssynbio.9b00075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooksley C. M., Zhang Y., Wang H., Redl S., Winzer K., Minton N. P. (2012). Targeted mutagenesis of the clostridium acetobutylicum acetone–butanol–ethanol fermentation pathway. Metab. Eng. 14 630–641. 10.1016/j.ymben.2012.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heider J., Ma K., Adams M. W. (1995). Purification, characterization, and metabolic function of tungsten-containing aldehyde ferredoxin oxidoreductase from the hyperthermophilic and proteolytic archaeon thermococcus strain ES-1. J. Bacteriol. 177 4757–4764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H., Chai C., Li N., Rowe P., Minton N. P., Yang S., et al. (2016). CRISPR/Cas9-based efficient genome editing in clostridium ljungdahlii, an autotrophic gas-fermenting bacterium. ACS Synth. Biolo. 5 1355–1361. 10.1021/acssynbio.6b00044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber C., Skopan H., Feicht R., White H., Simon H. (1995). Pterin cofactor, substrate specificity, and observations on the kinetics of the reversible tungsten-containing aldehyde oxidoreductase fromclostridium thermoaceticum. Arch. Microbiol. 164 110–118. 10.1007/BF02525316 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jones S. W., Fast A. G., Carlson E. D., Wiedel C. A., Au J., Antoniewicz M. R., et al. (2016). CO2 fixation by anaerobic non-photosynthetic mixotrophy for improved carbon conversion. Nat. Commun. 7:12800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim G., Azmi L., Jang S., Jung T., Hebert H., Roe A. J., et al. (2019). Aldehyde-alcohol dehydrogenase forms a high-order spirosome architecture critical for its activity. Nat. Commun. 10 1–11. 10.1038/s41467-019-12427-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klotzsch H. R. (1969). “[59] phosphotransacetylase from Clostridium kluyveri,” in Methods in Enzymology, Vol. 13 eds Kaplan N. O., Colowick S. P. (Cambridge, MA: Academic Press.), 381–386. 10.1016/0076-6879(69)13065-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Köpke M., Held C., Hujer S., Liesegang H., Wiezer A., Wollherr A., et al. (2010). Clostridium ljungdahlii represents a microbial production platform based on syngas. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107 13087–13092. 10.1073/pnas.1004716107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leang C., Ueki T., Nevin K. P., Lovley D. R. (2013). A genetic system for clostridium ljungdahlii: a chassis for autotrophic production of biocommodities and a model homoacetogen. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79 1102–1109. 10.1128/AEM.02891-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liew F., Henstra A. M., Köpke M., Winzer K., Simpson S. D., Minton N. P. (2017). Metabolic engineering of clostridium autoethanogenum for selective alcohol production. Metab. Eng. 40 104–114. 10.1016/j.ymben.2017.01.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liew F., Henstra A. M., Winzer K., Köpke M., Simpson S. D., Minton N. P. (2016). Insights into CO2 fixation pathway of clostridium autoethanogenum by targeted mutagenesis. mBio 7:e00427-16 10.1128/mBio.00427-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z.-Y., Jia D. C., Zhang K. D., Zhu H. F., Zhang Q., Jiang W. H., et al. (2020). Ethanol metabolism dynamics in clostridium ljungdahlii grown on carbon monoxide. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 86:e00730-20 10.1128/AEM.00730-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo J., Zheng T., Hon S., Olson D. G., Lynd L. R. (2015). The bifunctional alcohol and aldehyde dehydrogenase gene, AdhE, is necessary for ethanol production in clostridium thermocellum and thermoanaerobacterium saccharolyticum. J. Bacteriol. 197 1386–1393. 10.1128/JB.02450-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahamkali V., Valgepea K., de Souza R., Lemgruber P., Plan M., Tappel R., et al. (2020). Redox controls metabolic robustness in the gas-fermenting acetogen clostridium autoethanogenum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 117 13168–13175. 10.1073/pnas.1919531117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcano-Velazquez J. G., Lo J., Nag A., Maness P. C., Chou K. J. (2019). Developing riboswitch-mediated gene regulatory controls in thermophilic bacteria. ACS Synth. Biol. 8 633–640. 10.1021/acssynbio.8b00487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mock J., Zheng Y., Mueller A. P., Ly S., Tran L., Segovia S., et al. (2015). Energy conservation associated with ethanol formation from H2 and CO2 in clostridium autoethanogenum involving electron bifurcation. J. Bacteriol. 197 2965–2980. 10.1128/JB.00399-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molitor B., Marcellin E., Angenent L. T. (2017). Overcoming the energetic limitations of syngas fermentation. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. Mech. Biol. Energy 41 84–92. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2017.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagarajan H., Sahin M., Nogales J., Latif H., Lovley D. R., Ebrahim A., et al. (2013). Characterizing acetogenic metabolism using a genome-scale metabolic reconstruction of clostridium ljungdahlii. Microb. Cell Factor. 12:118. 10.1186/1475-2859-12-118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Napora-Wijata K., Strohmeier G. A., Winkler M. (2014). Biocatalytic reduction of carboxylic acids. Biotechnol. J. 9 822–843. 10.1002/biot.201400012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nissen L. S., Basen M. (2019). The emerging role of aldehyde:ferredoxin oxidoreductases in microbially-catalyzed alcohol production. J. Biotechnol. 306 105–117. 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2019.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter H., Molitor B., Wei H., Chen W., Aristilde L., Angenent L. T. (2016). Ethanol production in syngas-fermenting clostridium ljungdahlii is controlled by thermodynamics rather than by enzyme expression. Energy Environ. Sci. 9 2392–2399. 10.1039/C6EE01108J [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schuchmann K., Müller V. (2014). Autotrophy at the thermodynamic limit of life: a model for energy conservation in acetogenic bacteria. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 12 809–821. 10.1038/nrmicro3365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan Y., Liu Z.-Y., Liu Z., Li F.-L. (2015). Characterization of an acetoin Reductase/2,3-butanediol dehydrogenase from clostridium ljungdahlii DSM 13528. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 79–80 1–7. 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2015.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay P. L., Zhang T., Dar S. A., Leang C., Lovley D. R. (2013). The Rnf complex of clostridium ljungdahlii is a proton-translocating ferredoxin:NAD+ oxidoreductase essential for autotrophic growth. mBio 4:e00406-12. 10.1128/mBio.00406-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueki T., Nevin K. P., Woodard T. L., Lovley D. R. (2014). Converting carbon dioxide to butyrate with an engineered strain of clostridium ljungdahlii. mBio 5:e01636-14. 10.1128/mBio.01636-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitham J. M., Tirado-Acevedo O., Chinn M. S., Pawlak J. J., Grunden A. M. (2015). Metabolic response of clostridium ljungdahlii to oxygen exposure. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 81 8379–8391. 10.1128/AEM.02491-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolston B. M., Emerson D. F., Currie D. H., Stephanopoulos G. (2018). Rediverting carbon flux in clostridium ljungdahlii using CRISPR interference (CRISPRi). Metab. Eng. 48 243–253. 10.1016/j.ymben.2018.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao S., Mikkelsen M. J. (2010). Identification and overexpression of a bifunctional aldehyde/alcohol dehydrogenase responsible for ethanol production in thermoanaerobacter mathranii. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 19 123–133. 10.1159/000321498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H.-F., Liu Z.-Y., Zhou X., Yi J.-H., Lun Z.-M., Wang S.-N., et al. (2020). . Energy conservation and carbon flux distribution during fermentation of CO or H2/CO2 by clostridium ljungdahlii. Front. Microbiol. 11:416. 10.3389/fmicb.2020.00416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All datasets generated for this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material.