Abstract

Among the 146 patients enrolled in the Korean FH registry, 83 patients who had undergone appropriate LLT escalation and were followed-up for ≥ 6 months were analyzed for pathogenic variants (PVs). The achieved percentage of expected low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (LDL-C) reduction (primary variable) and achievement rates of LDL-C < 70 mg/dL were assessed. The correlations between the treatment response and the characteristics of PVs, and the weighted 4 SNP-based score were evaluated. The primary variables were significantly lower in the PV-positive patients than in the PV-negative patients (p = 0.007). However, the type of PV did not significantly correlate with the primary variable. The achievement rates of LDL-C < 70 mg/dL was very low, regardless of the PV characteristics. Patients with a higher 4-SNP score showed a lower primary variable (R2 = 0.045, p = 0.048). Among evolocumab users, PV-negative patients or those with only defective PVs revealed higher primary variable, whereas patients with at least one null PV showed lower primary variables. The adjusted response of patients with FH to LLT showed significant associations with PV positivity and 4-SNP score. These results may be helpful in managing FH patients with diverse genetic backgrounds.

Subject terms: Clinical genetics, Dyslipidaemias, Risk factors, Dyslipidaemias

Introduction

Many patients with familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) are not diagnosed early enough to be treated properly and this has made it a global health issue1–3. Pharmacological treatment for FH has made considerable progress in the past two decades. Currently, pharmacological agents including statins, ezetimibe, and PCSK9 inhibitors are used to treat FH in clinical practice4,5. Clinical trials or registry studies conducted till date have reported that individual responses to lipid-lowering therapy (LLT) using statins6 and/or PCSK9 inhibitors7–9 vary substantially. Individual difference in response to LLT is a crucial clinical issue as it can affect cardiovascular outcomes10. However, the reason underlying the variation in response to LLT among individuals is not yet completely understood.

Several clinical11 and genetic factors12 have been reported to influence the response in general population. Thus, in FH, it is likely that genetic variations affect an individual’s response to LLT. Differences in cardiovascular risk due to genetic characteristics in FH13,14 may be partly explained if the presence or type of pathogenic variants (PVs) influenced the patient response. Some studies have reported that the response to statins15 and PCSK9 inhibitors16 could differ depending on PV types, such as defective PV. However, contradictory studies8,17 have warranted the need for further studies to clarify the link between genetic characteristics and responses to statins and PCSK9 inhibitors.

This study aimed to analyze the relationship between genetic characteristics and the response to LLT in patients with FH. The primary variable in our study was the achieved percentage of expected response to LLT. First, the expected low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (LDL-C) reduction with an LLT regimen was estimated and then the achieved percentage of this expected value was calculated for each subject. The correlation of the 4-SNP score18 with the response was also investigated, and the difference in response according to genetic characteristics was evaluated in patients receiving evolocumab.

Methods

Study population

Nine university hospitals participated in this study supported by the Korean Society of Lipid and Atherosclerosis18–21. All subjects gave written informed consent, and all study protocols were approved by the institutional review board of Severance Hospital, Seoul, Korea. The study protocol conforms to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki. One hundred and forty-six men and women aged more than 19 years who met the Simon-Broome criteria22 for heterozygous FH were enrolled in the study conducted from January 2009 to July 2014. Among them, 83 patients who underwent proper escalation of LLT (described in ‘2.3. Parameters of response to LLT’) and followed up for ≥ 6 months, and for whom pre- and post-treatment LDL-C levels were known were finally analyzed. Among the 63 excluded patients, 31 did not receive appropriate LLT escalation, 18 were not followed-up for 6 months, whereas 14 did not undergo regular measurement of LDL-C.

Clinical and genetic data collection

Patient history was obtained from every patient, and each patient was subjected to physical examination and laboratory assessment. Patients under LLT at enrollment were asked to skip lipid-lowering agents for 4 weeks unless they had a history of atherosclerotic cardiovascular or cerebrovascular diseases. The patients fasted for 12 h before blood sampling, and the samples were analyzed within 4 h at a local laboratory. DNA sequencing and analysis for putative PVs was performed as described previously20 and in Supplementary Information.

According to the detection of non-synonymous variants by the Unified GATK Genotyper (v2.3.6), variants were classified as pathogenic based on the information regarding three FH-related genes on public databases. For variants that had not been previously reported, pathogenicity was confirmed based on one of the following: (1) inevitably deleterious effects of amino acid changes such as frame shift insertions/deletions and copy number deletions or (2) co-segregation of the same variants within the family. Thereafter, all variants listed as pathogenic were validated by Sanger sequencing. All variants were also checked by the MUTALYZER program. Finally, each variant was classified according to the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics guidelines. Null PVs included point PVs that cause a premature stop codon, missense PVs affecting the fifth cysteine rich repeat in the ligand binding domain of LDLR, small deletions or insertions causing a frame shift, and a premature stop codon or large rearrangements. The remaining in-frame point PVs and in-frame small deletions and insertions consisted of receptor-defective PVs13.

Parameters of response to LLT

When patients were enrolled in the study, LLT was initiated with moderate intensity statins (i.e. rosuvastatin 5‒10 mg, atorvastatin 10‒20 mg, or other statins with a similar efficacy). If the statin was tolerated well, it was up-titrated every 2 months to reach an LDL-C level of 100 mg/dL. Ezetimibe was added if patients were intolerant to the statins or if the target LDL-C level was not achieved with the maximum tolerable dose of statin. Bile acid sequestrants, niacin, or PCSK9 inhibitors were administered to patients who did not show sufficient LDL-C reduction with statin/ezetimibe regimens. However, data only related to treatment responses for maximum statin dose with or without ezetimibe before introduction of other agents were used for the main analysis.

Pre-treatment LDL-C levels were defined as the documented values before drug therapy, whereas post-treatment LDL-C levels were defined as the values obtained by a maximally up-titrated statin/ezetimibe regimen at 6‒12 months after drug treatment. The primary evaluation variable was the achieved percentage of expected LDL-C reduction. The expected LDL-C reduction was calculated using different doses of statins determined from previous studies and reviews (Table 1)23–29. Other evaluation variables included the percentage LDL-C reduction and achievement rate of an LDL-C target of < 70 mg/dL.

Table 1.

Expected LDL-C reduction by different doses of the lipid-lowering regimen.

| Lipid-lowering regimen | Expected LDL-C reduction, % |

|---|---|

| Atorvastatin 10 mg or similar/day | − 40 |

| Atorvastatin 20 mg or similar/day | − 46 |

| Atorvastatin 40 mg or similar/day | − 52 |

| Atorvastatin 80 mg or similar/day | − 56 |

| Atorvastatin 20 mg/ezetimibe 10 mg/day | − 61 |

| Atorvastatin 40 mg/ezetimibe 10 mg/day | − 66 |

| Evolocumab 140 mg/2 weeks | − 54 (additional) |

LDL-C low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol.

For additional six patients who received evolocumab in addition to the statin/ezetimibe regimens, the achieved percentage of expected LDL-C reduction was analyzed separately. The expected LDL-C reduction after addition of evolocumab to the regimen at a dose of 140 mg/2 weeks for 3 months was assumed to be 54%.

4-SNP score

We genotyped the four SNPs associated with cholesterol levels in the FH patients and the general population in East Asia18,30, i.e., rs651007, rs599839, rs12654264, and rs2738446 and are located close to ABO, CELSRS-PSRC1-SORT1, HMGCR, and LDLR, respectively. Weighted mean SNP scores of patients were calculated using alleles associated with cholesterol levels and their beta-coefficients, as reported in the East Asian genome-wide association study (Supplementary Table 1. List of SNPs associated with elevated LDL-C levels in East Asians). The correlation between the 4-SNP score and the primary variable was analyzed.

Statistical analyses

Continuous data are presented as mean ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range), whereas categorical variables are reported as frequencies and percentages. Data related to clinical and laboratory values were compared using the chi-square test. Between-group comparisons were performed using the Mann‒Whitney U-test. Linear regression was used to assess the association between the 4 SNP score and treatment response in the PV-negative group. There were no missing data in this study. All analyses used a significance level of 0.05. SPSS version 25.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for the analyses.

Results

Clinical characteristics of the study population

The characteristics of the 83 patients enrolled in the study are presented in Table 2. The mean age of the patients was 53 years and 50 (60%) of them were women. Putative PVs were identified in 30 patients (36%) (Supplementary Table S2). The median baseline LDL-C was higher in the carriers of PVs compared to that in the PV-negative patients (246 mg/dL and 206 mg/dL, respectively, p < 0.001). The median baseline LDL-C levels were 256 mg/dL, 248 mg/dL, and 205 mg/dL in patients with null LDLR PVs, defective LDLR PVs, and APOB or PCSK9 PVs, respectively. However, differences in LDL-C levels between individuals with different PV types were insignificant (Table 3). During the median follow-up period of 10 months, 40 (48%) patients were treated with statin monotherapy, whereas 43 (52%) received statin/ezetimibe combination therapy (Table 2).

Table 2.

Clinical and laboratory parameters of the study population.

| Variables | Value or frequency (total subjects = 83) |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 53 ± 12 |

| Females | 50 (60.2) |

| Medical history | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 6 (7.2) |

| Hypertension | 30 (36.1) |

| Current smoking | 2 (2.4) |

| CAD | 27 (32.5) |

| Family history | |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 46 (55.4) |

| Premature CAD | 42 (50.6) |

| Physical findings | |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 24.7 ± 4.5 |

| Tendon xanthoma | 17 (20.5) |

| Type of FH in clinical diagnosis | |

| Definite | 18 (21.7) |

| Possible | 65 (78.3) |

| PV positivity | 30 (36.1) |

| Lipid profile, mg/dL | |

| Total cholesterol | 307 (287, 341) |

| Triglyceride | 149 (116, 227) |

| HDL-C | 46 (40, 56) |

| LDL-C | 213 (198, 248) |

| Maximal statin-based lipid-lowering regimen | |

| Atorvastatin 10 mg or similar | 6 (7.2) |

| Atorvastatin 20 mg or similar | 22 (26.5) |

| Atorvastatin 40 mg or similar | 7 (8.4) |

| Atorvastatin 80 mg or similar | 5 (6.0) |

| Atorvastatin 20 mg/ezetimibe 10 mg or similar | 10 (12.0) |

| Atorvastatin 40 mg/ezetimibe 10 mg or similar | 21 (25.3) |

| Atorvastatin 80 mg/ezetimibe 10 mg or similar | 12 (14.5) |

Data are presented as n (%), mean ± standard deviation, or median (interquartile range).

Premature CAD is defined as CAD at age < 50 years in a grandparent, aunt, or uncle or at age < 60 years in a parent, sibling, or child.

CAD coronary artery disease, FH familial hypercholesterolemia, PV pathogenic variant, HDL-C high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol, LDL-C low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol.

Table 3.

Genetic background and response to LLT with a statin/ezetimibe regimen.

| Total population (n = 83) | PV-negative (n = 53) | PV-positive (n = 30) | pa | pb | pc | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any PV-positive (n = 30) | LDLR mutation (n = 27) |

APOB or PCSK9 PV (n = 3) |

||||||||

| Any LDLR PV (n = 27) | Null LDLR PV (n = 10) | Defective LDLR PV (n = 17) | ||||||||

| Pre-statin/ezetimibe LDL-C, mg/dL | 213 (198, 248) | 206 (197, 223) | 246 (215, 284) | 248 (222, 288) | 256 (223, 289) | 248 (213, 294) | 205 (174, –) | < 0.001 | 0.078 | 0.63 |

| Post-statin/ezetimibe LDL-C, mg/dL | 114 (96, 131) | 105 (88, 125) | 122 (110, 138) | 122 (114, 139) | 133 (123, 143) | 119 (110, 137) | 97 (69, –) | 0.012 | 0.13 | 0.059 |

| LDL-C reduction, % | 51.9 (41.9, 57.3) | 50.7 (42.2, 55.6) | 50.7 (39.5, 58.4) | 50.4 (39.4, 58.8) | 49.9 (44.8, 54.4) | 51.0 (39.4, 61.2) | 59.1 (24.1, –) | 0.82 | 0.56 | 0.48 |

| LDL-C reduction % of expected value | 89.3 (70.1, 109.2) | 95.3 (75.3, 118.1) | 82.8 (59.1, 91.2) | 81.2 (59.9, 91.1) | 76.9 (66.6, 85.6) | 88.6 (58.0, 94.2) | 89.5 (34.5, –) | 0.007 | 0.76 | 0.15 |

| Achievement of LDL-C < 70 mg/dL (%) | 5 (6.0) | 4 (7.5) | 1 (3.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (33.3) | 0.44 | 0.003 | 1.00 |

Data are presented as median (interquartile range) or number (%).

pa: comparison between PV-positive and -negative patients.

pb: comparison between LDLR PV and APOB or PCSK9 PV carriers.

pc: comparison between null LDLR PV and defective LDLR PV carriers.

LLT lipid-lowering therapy, PV pathogenic variant, LDL-C low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol.

Genetic variants and response to LLT

In the total study population (n = 83), the median LDL-C decreased from 213 mg/dL to 105 mg/dL (median LDL-C reduction 51.9%). The primary variable, the achieved percentage of expected LDL-C reduction, was 89% and the achievement rate of LDL-C < 70 mg/dL was 6.0%. The distribution of the primary evaluation variable is shown in Supplementary Fig. 1 (Distribution of the achieved percentage of expected LDL-C reduction). The primary variable was significantly lower in the PV-positive patients than in the PV-negative patients (82.8% and 95.3%, respectively, p = 0.007). Although this variable was lower in patients with null LDLR PVs than in those with defective LDLR PV, the difference was not significant (76.9% and 88.6%, respectively, p = 0.15). The primary variable was similar between carriers of LDLR PVs and those with PVs in the other two genes. Only four PV-negative patients and one with PCSK9 PV achieved LDL-C < 70 mg/dL (Table 3).

4-SNP score and response to LLT

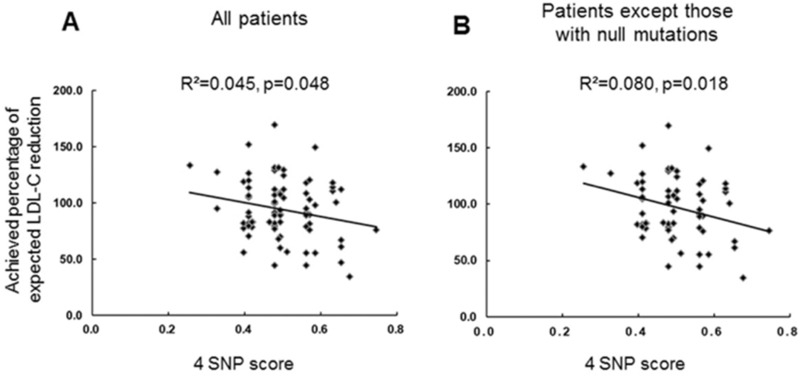

The correlation between the weighted mean of the 4-SNP score in the study population and the primary evaluation variable is presented in Fig. 1. Patients with a higher score showed a lower achieved percentage of expected LDL-C reduction (R2 = 0.045, p = 0.048) (Fig. 1A). Interestingly, the correlation between the 4-SNP score and the primary variable was stronger in the subgroup of patients without null PVs (R2 = 0.080, p = 0.018) (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

Correlation between the weighted 4-SNP score and the achieved percentage of expected LDL-C reduction in all study patients (A) and patients without null PVs (B). The image was created using GraphPad Prism version 8.4.3 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA; www.graphpad.com).

Genetic variants and response to evolocumab

Six additional patients enrolled and analyzed in the study received evolocumab for ≥ 3 months. One of the patients was PV-negative and the others had PVs in LDLR. The primary variable by evolocumab was 153.3% in the PV-negative patients, whereas it was 46.0% in the PV-positive patients. Two of the heterozygous patients had the same null PV in c.682G > T (p.E228X), and the primary evaluation variables were 27.5% and 39.7%, respectively. One heterozygous patient had an LDLR copy number variation and a primary variable of 52.2%. The primary variable for the other heterozygous patient with a defective LDLR PV was 140.9%. Among the two homozygous patients, one had one null and one defective PV and the other had two defective PVs. Interestingly, the achieved percentages of expected LDL-C reduction were quite different in these two individuals (34.0% and 141.8% in the former and the latter, respectively) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Genetic background and response to LLT with evolocumab.

| PV-negative (n = 1) | PV-positive (n = 6) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any PV-positive (n = 6) | Heterozygous PV (n = 4) | Homozygous PV (n = 2) | ||||||

| c.682G > T (p.E228X) (n = 2) | CNV, exon 8–12 (n = 1) | c.519C > G (C173W) (n = 1) | G558X and c.-136C > T (n = 1) |

c.1567G > A (V523M) and c.-136C > T (n = 1) | ||||

| Pre-evolocuamb LDL-C, mg/dL | 157 | 154 (135, 327) | 169 | 126 | 138 | 138 | 410 | 299 |

| Post-evolocuamb LDL-C, mg/dL | 27 | 103 (61, 194) | 149 | 99 | 107 | 33 | 329 | 70 |

| LDL-C reduction, % | 82.8 | 21.9 (17.8, 76.2) | 11.8 | 21.4 | 22.5 | 76.1 | 19.8 | 76.6 |

| LDL-C reduction, % of expected value | 153.3 | 46.0 (32.4, 141.1) | 27.5 | 39.7 | 52.2 | 140.9 | 34.0 | 141.8 |

Data are presented as a number, percentage, or median (interquartile range).

LLT lipid-lowering therapy, PV pathogenic variant, LDL-C low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol, CNV copy number variation.

Discussion

The major findings of this study include the following. First, the adjusted response to LLT, the primary variable, was lower in carriers of PVs than in PV-negative patients. The type of PV did not significantly affect the primary variable. Second, individuals with a higher 4-SNP score showed a lower primary variable. Third, the primary variables for evolocumab-treated patients tended to be lower for PV-positive patients, particularly null PV carriers. We determined the response to LLT according to the adjusted percentage change of LDL-C by regimens titrated in the real world, and analyzed its correlation with the patient’s genotype. Prior studies analyzed response to non-maximal intensity LLT31 or unadjusted response to drug doses32. Furthermore, some investigators analyzed the response in a binary fashion according to the attainment of target LDL-C levels15. We evaluated the relationship between polygenic score and adjusted drug response, which has not been previously reported. In addition, we reported the association between genotype and adjusted response to evolocumab, which has also been rarely discussed in previous studies. However, since the number of our cases on this issue was not large, further studies are needed.

The results of this study confirmed that the response to LLT is poorer in PV-positive patients. PV-positive patients with FH have been known to have higher cardiovascular risk than PV-negative patients33. Therefore, genetic information in FH cases could enable risk evaluation, thereby ensuring rigorous management and treatment for individuals with higher risk. Interestingly, 28 patients (33.7%) from our study population received just moderate intensity statins. In additional analysis, the LLT intensities used in the PV-negative group and the PV-positive group were found to be significantly different (p < 0.001) (Supplementary Table S3. LLT intensities used in the PV-negative and -positive patients). In particular, 27 (50.9%) of PV-negative patients used moderate intensity statins, whereas only one (3.3%) of PV-positive patients used moderate intensity statins.

The median percentage change of LDL-C was − 51.9% in our total study population. In clinical trials with heterozygous FH patients, the values were − 49% by pitavastatin 4 mg34 and − 46 to − 51% by simvastatin 80 mg35. However, in real world data of patients receiving statins with or without ezetimibe, the values varied from − 3636 to − 50%37. The percentage change of LDL-C of our study was relatively large in our study. However, it is difficult to directly compare these values, as therapeutic regimens were heterogenous in individual studies, and data on the relationship between LLT intensities and responses have not been shown. This is one of the reasons why we used an adjusted parameter of response to LLT.

In the present study, we compared primary variables according to types of PVs. Although the variables were numerically lower in null LDLR PV carriers than those in defective LDLR PV carriers, the difference was not significant. However, we cannot fully rule out the fact that this might have been significant had the study incorporated a larger number of patients. In a previous study, patients with null PVs had higher LDL-C levels before and after LLT as compared to those with defective PVs38 and lower rates of target achievement independent of the statin dose32. Furthermore, in a relatively large study conducted on Spanish patients, the presence of defective PVs was found to be an independent predictor of achievement of LDL-C goal15. In another study, LDL-C reduction with atorvastatin, 20 mg/day was observed to vary among different classes of LDLR PVs (49% and 34% for class V and class II PVs, respectively)31. Another study revealed that heterozygous FH patients with defective LDLR PVs showed a better response to statin/ezetimibe-based LLT than homozygous FH patients with defective LDLR PVs39. However, data related to the response to LLT based on types of PVs are inconsistent, as indicated by a previous study40, and are not fully understood yet. In a previous study on homozygous FH patients, mean LDL-C reduction by rosuvastatin 20 mg/day was not much different between carriers of defective/negative PVs and those of defective/defective PVs (17.0% and 21.3%, respectively)17.

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to identify the association between the 4-SNP score and the response to LLT. SNPs that correlated with LDL-C levels in Korean patients with FH in our prior study18 were used for the score. A few variants of SLCO1B1, SLCO1B3, and ABCC2 have been reported to be correlated with the response to statins41 in Koreans, and this correlation has been linked to pharmacodynamic pathways. In addition, a common loss-of-function variant of PCSK9 showed an association with greater response to statins in an American study42. The Heart Protection Study and a meta-GWAS demonstrated that variants of SORT1/CELSR2/PSRC1, SLCO1B1, APOE, and LPA are associated with the response to statins12,43. The 4-SNP score in this study includes SORT1, CELSR2, and PSRC1, and the effect of their corresponding variants contributes to the agreement of our findings with those of previous studies.

The present study showed that the presence of a null PV could affect the response to evolocumab regardless of the homozygosity of PVs. Prior data related to the effect of genotype on the response to PCSK9 inhibitors have been variable. An analysis of six studies using alirocumab, a PCSK9 inhibitor, revealed that LDL-C reduction was generally similar across genotypes (54.3% and 60.7% in defective LDLR- and negative LDLR PV carriers, respectively)8. In addition, a recent report on homozygous FH has shown that the response to alirocumab in defective/negative LDLR PV carriers was not worse than that in defective/defective LDLR PV carriers44. On the contrary, in this study, the response to evolocumab was higher than expected in heterozygous FH with defective PVs and in homozygous FH with defective/defective PVs. However, the response in heterozygous and homozygous patients with null PVs was poor. These findings indicate that the influence of null PVs can be greater than that of homozygosity of PVs. A recent study evaluated the long-term effect of evolocumab in homozygous and severe heterozygous FH. Although the relationship between genotype and drug efficacy was not the main focus of this study, reduced efficacy of the agent was observed in patients with two negative LDLR PVs9.

Our study, however, has potential limitations. First, while the current study used a 4-SNP score, the effect of other SNPs of the same genes or other lipid-related genes cannot be ruled out. Second, because this study was performed using data from Korea, we need to be cautious when generalizing our results. Third, we cannot rule out some difference between patient groups that was not revealed in the current data. For example, median baseline LDL-C levels did not differ according to PV types. However, these were derived in part from limited number of patients with APOB or PCSK9 PVs that usually constitute a small minority of FH patients. However, adjustment of the response to LLT by calculating the achieved percentage of expected LDL-C is the strength of this study.

In conclusion, our findings indicate that adjusted response to LLT has significant associations with PV positivity and the 4-SNP score. The results obtained in this study may ensure effective and individual management of FH patients with diverse genetic backgrounds.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Jiyeong Jeong, RN and Yoo Kyung Jung, RN for their excellent assistance with clinical data collection.

Author contributions

H.K., C.J.L., and S.-H.L.: formal analysis, investigation, writing—original draft; D.I.K., M.-Y.R., B.K.L., Y.A., B.R.C., J.-T.W., S.-H.H., J.-O.J., and S.-H.L.: resources, supervision, writing—review & editing; H.P. and J.H.L.: formal analysis, investigation, writing—original draft; S.-H.L.: conceptualization, funding acquisition, and project administration.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Ji Hyun Lee, Email: hyunihyuni@khu.ac.kr.

Sang-Hak Lee, Email: shl1106@yuhs.ac.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-020-75901-0.

References

- 1.Nordestgaard BG, et al. Familial hypercholesterolaemia is underdiagnosed and undertreated in the general population: Guidance for clinicians to prevent coronary heart disease: Consensus statement of the European Atherosclerosis Society. Eur. Heart J. 2013;34:3478–3490. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gidding SS, et al. The agenda for familial hypercholesterolemia: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;132:2167–2192. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilemon KA, et al. Reducing the clinical and public health burden of familial hypercholesterolemia: A global call to action. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5:217–229. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2019.5173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cuchel M, et al. Homozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia: New insights and guidance for clinicians to improve detection and clinical management. A position paper from the Consensus Panel on Familial Hypercholesterolaemia of the European Atherosclerosis Society. Eur. Heart J. 2014;35:2146–2157. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mach F, et al. ESC Scientific Document Group. ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: Lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk. Eur. Heart J. 2020;41:111–188. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karlson BW, et al. Variability of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol response with different doses of atorvastatin, rosuvastatin, and simvastatin: Results from VOYAGER. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacother. 2016;2:212–217. doi: 10.1093/ehjcvp/pvw006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Giugliano RP, et al. Clinical efficacy and safety of achieving very low LDL-cholesterol concentrations with the PCSK9 inhibitor evolocumab: A prespecified secondary analysis of the FOURIER trial. Lancet. 2017;390:1962–1971. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32290-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Defesche JC, et al. Efficacy of alirocumab in 1191 patients with a wide spectrum of mutations in genes causative for familial hypercholesterolemia. J. Clin. Lipidol. 2017;11:1338–1346.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2017.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Santos RD, et al. Long-term evolocumab in patients with familial hypercholesterolemia. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020;75:565–574. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akyea RK, Kai J, Qureshi N, Iyen B, Weng SF. Sub-optimal cholesterol response to initiation of statins and future risk of cardiovascular disease. Heart. 2019;105:975–981. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2018-314253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trompet S, et al. Non-response to (statin) therapy: The importance of distinguishing non-responders from non-adherers in pharmacogenetic studies. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2016;72:431–437. doi: 10.1007/s00228-015-1994-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Postmus I, et al. Pharmacogenetic meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies of LDL cholesterol response to statins. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:5068. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alonso R, on behalf of the Spanish Familial Hypercholesterolaemia Group et al. Cardiovascular disease in familial hypercholesterolaemia: Influence of low-density lipoprotein receptor mutation type and classic risk factors. Atherosclerosis. 2008;200:315–321. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2007.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khera AV, et al. Diagnostic yield and clinical utility of sequencing familial hypercholesterolemia genes in patients with severe hypercholesterolemia. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2016;67:2578–2589. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.03.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perez De Isla L, SAFEHEART Investigators et al. Attainment of LDL-cholesterol treatment goals in patients with familial hypercholesterolemia: 5-year SAFEHEART registry follow-up. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2016;67:1278–1285. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stein EA, et al. Effect of the proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin 9 monoclonal antibody, AMG 145, in homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia. Circulation. 2013;128:2113–2120. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.004678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stein EA, et al. Efficacy of rosuvastatin in children with homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia and association with underlying genetic mutations. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2017;70:1162–1170. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.06.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kwon M, et al. Evaluation of polygenic cause in Korean patients with familial hypercholesterolemia—A study supported by Korean Society of Lipidology and Atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 2015;242:8–12. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2015.06.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Han SM, et al. Genetic testing of Korean familial hypercholesterolemia using whole-exome sequencing. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0126706. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0126706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shin DG, et al. Clinical features of familial hypercholesterolemia in Korea: Predictors of pathogenic mutations and coronary artery disease—A study supported by the Korean Society of Lipidology and Atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 2015;243:53–58. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2015.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oh J, et al. Target achievement with maximal statin-based lipid-lowering therapy in Korean patients with familial hypercholesterolemia: A study supported by the Korean Society of Lipid and Atherosclerosis. Clin. Cardiol. 2017;40:1291–1296. doi: 10.1002/clc.22826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marks D, Thorogood M, Neil HAW, Humphries SE. A review on the diagnosis, natural history, and treatment of familial hypercholesterolaemia. Atherosclerosis. 2003;168:1–14. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9150(02)00330-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim KJ, et al. Effect of fixed-dose combinations of ezetimibe plus rosuvastatin in patients with primary hypercholesterolemia: MRS-ROZE (Multicenter Randomized Study of rosuvastatin and eZEtimibe) Cardiovasc. Ther. 2016;34:371–382. doi: 10.1111/1755-5922.12213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Catapano AL, ESC Scientific Document Group et al. 2016 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias. Eur. Heart J. 2016;37:2999–3058. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Collins R, et al. Interpretation of the evidence for the efficacy and safety of statin therapy. Lancet. 2016;388:2532–2561. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31357-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang YJ, et al. Combination therapy of rosuvastatin and ezetimibe in patients with high cardiovascular risk. Clin. Ther. 2017;39:107–117. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2016.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim W, et al. Efficacy and safety of ezetimibe and rosuvastatin combination therapy versus those of rosuvastatin monotherapy in patients with primary hypercholesterolemia. Clin. Ther. 2018;40:993–1013. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2018.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hong SJ, et al. A phase III, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, active comparator clinical trial to compare the efficacy and safety of combination therapy with ezetimibe and rosuvastatin versus rosuvastatin monotherapy in patients with hypercholesterolemia: I-ROSETTE (Ildong rosuvastatin & ezetimibe for hypercholesterolemia) randomized controlled trial. Clin. Ther. 2018;40:226–241.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2017.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ruel I, et al. Imputation of baseline LDL cholesterol concentration in patients with familial hypercholesterolemia on statins or ezetimibe. Clin. Chem. 2018;64:355–362. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2017.279422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim YJ, et al. Large-scale genome-wide association studies in East Asians identify new genetic loci influencing metabolic traits. Nat. Genet. 2011;43:990–995. doi: 10.1038/ng.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miltiadous G, et al. Genetic and environmental factors affecting the response to statin therapy in patients with molecularly defined familial hypercholesterolaemia. Pharmacogenet. Genom. 2005;15:219–225. doi: 10.1097/01213011-200504000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Santos PCJL, et al. Presence and type of low density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR) mutation influences the lipid profile and response to lipid-lowering therapy in Brazilian patients with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia. Atherosclerosis. 2014;233:206–210. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2013.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sharifi M, Rakhit RD, Humphries SE, Nair D. Cardiovascular risk stratification in familial hypercholesterolaemia. Heart. 2016;102:1003–1008. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2015-308845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Noji Y, et al. Long-term treatment with pitavastatin (NK-104), a new HMG-CoA reductase nhibitor, of patients with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia. Atherosclerosis. 2002;163:157–164. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9150(01)00765-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.de Sauvaage Nolting PR, et al. Baseline lipid values partly determine the response to high-dose simvastatin in patients with familial hypercholesterolemia: The examination of probands and relatives in Statin studies with familial hypercholesterolemia (ExPRESS FH) Atherosclerosis. 2002;164:347–354. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9150(02)00111-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rizos CV, et al. Characteristics and management of 1093 patients with clinical diagnosis of familial hypercholesterolemia in Greece: Data from the Hellenic Familial Hypercholesterolemia Registry (HELLAS-FH) Atherosclerosis. 2018;277:308–313. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2018.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Delden XM, et al. LDL-cholesterol target achievement in patients with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia at Groote Schuur Hospital: Minority at target despite large reductions in LDL-C. Atherosclerosis. 2018;277:327–333. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2018.06.820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Santos PCJL, Pereira AC. Type of LDLR mutation and the pharmacogenetics of familial hypercholesterolemia treatment. Pharmacogenomics. 2015;16:1743–1750. doi: 10.2217/pgs.15.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schaefer JR, Kurt B, Sattler A, Klaus G, Soufi M. Pharmacogenetic aspects in familial hypercholesterolemia with the special focus on FHMarburg (FH p.W556R) Clin. Res. Cardiol. Suppl. 2012;7:2–6. doi: 10.1007/s11789-012-0041-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Etxebarria A, et al. Functional characterization and classification of frequent low-density lipoprotein receptor variants. Hum. Mut. 2015;36:129–141. doi: 10.1002/humu.22721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Woo HI, Kim SR, Huh W, Ko JW, Lee SY. Association of genetic variations with pharmacokinetics and lipid-lowering response to atorvastatin in healthy Korean subjects. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2017;11:1135–1146. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S131487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Feng Q, et al. The effect of genetic variation in PCSK9 on the LDL-cholesterol response to statin therapy. Pharmacogenom. J. 2017;17:204–208. doi: 10.1038/tpj.2016.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hopewell JC, et al. Impact of common genetic variation on response to simvastatin therapy among 18 705 participants in the Heart Protection Study. Eur. Heart J. 2013;34:982–992. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hartgers ML, et al. Alirocumab efficacy in patients with double heterozygous, compound heterozygous, or homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia. J. Clin. Lipidol. 2018;12:390–396.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2017.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.