Abstract

Since mid-April 2020, cases of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) associated with coronavirus disease 2019 that mimics Kawasaki disease (KD) have been reported in Europe and North America. However, no cases have been reported in Korea. We describe an 11-year old boy with fever, abdominal pain, and diarrhea who developed hypotension requiring inotropes in intensive care unit. His blood test revealed elevated inflammatory markers, thrombocytopenia, hypoalbuminemia, and coagulopathy. Afterward, he developed signs of KD such as conjunctival injection, strawberry tongue, cracked lip, and coronary artery dilatation, and parenchymal consolidation without respiratory symptoms. Microbiological tests were all negative including severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction. However, serum immunoglobulin G against SARS-CoV-2 was positive in repeated tests using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and fluorescent immunoassay. He was recovered well after intravenous immunoglobulin administration and discharged without complication on hospital day 13. We report the first Korean child who met all the criteria of MIS-C with features of incomplete KD or KD shock syndrome.

Keywords: Kawasaki Disease, Kawasaki Disease Shock Syndrome, Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children, Intravenous Immunoglobulin, COVID-19

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has been spreading worldwide since it was first reported in Wuhan, China in December 2019. On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the COVID-19 outbreak a pandemic.1 Clinical symptoms of COVID-19 in pediatric patients are generally less severe than those in adult patients.2 However, since mid-April 2020, clusters of children with multisystem inflammatory disease similar to Kawasaki disease shock syndrome (KDSS) have been reported in Europe3 and North America,4 and some cases appeared to be associated with COVID-19. In these cases, the clinical presentations varied and were consistent with complete or incomplete Kawasaki disease (KD), toxic shock syndrome (TSS), multisystemic hyperinflammation, gastrointestinal symptoms (such as abdominal pain and diarrhea), or pleural/pericardial effusion.5 In some cases, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and/or antibody tests for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) yielded positive results. The WHO has provided a preliminary case definition of “multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) and adolescents” temporally associated with COVID-19.6 Here, we present a case of a South Korean child who met all criteria of MIS-C6,7 with features of incomplete KD or KDSS and was tested positive on the SARS-CoV-2 antibody test. This is the first case of MIS-C related to COVID-19 in Korea.8

CASE DESCRIPTION

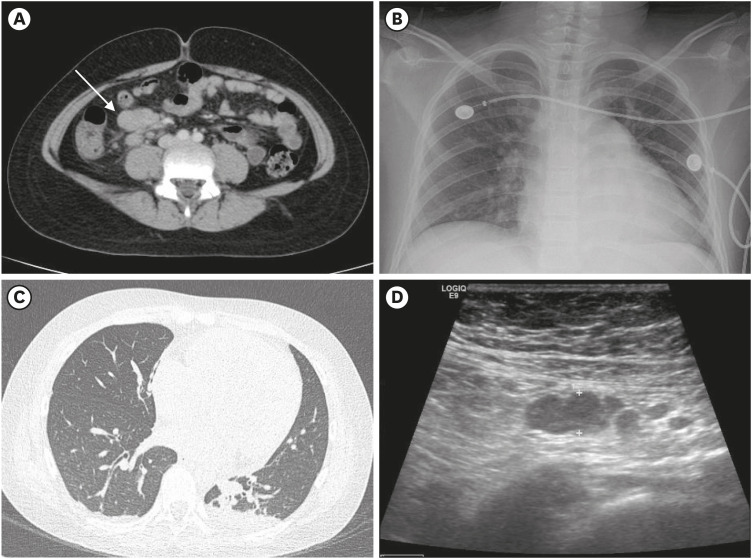

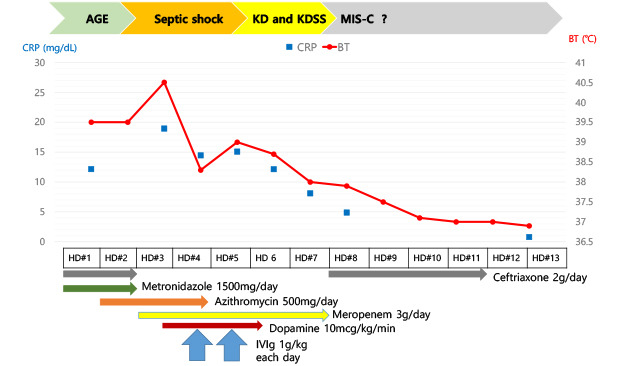

A previously healthy 11-year-old boy was hospitalised on April 29, 2020 with a 4-day history of fever, nausea, and abdominal pain. He looked acutely ill, but his vital signs were stable. A clear breathing sound was heard, and direct tenderness on the right side of his abdomen was noted. The patient had no medical history other than pneumonia, which he had developed 7 years before. He had not been in contact with any person diagnosed with COVID-19. However, he was in the Philippines from January to the first week of March 2020, where 10 confirmed cases of COVID-19 were reported during that period9 and had flown back to Korea. Laboratory findings revealed elevated C-reactive protein (CRP, 121.50 mg/L) and procalcitonin (0.750 mcg/L) levels with a normal whole blood cell count. Fig. 1 shows the imaging tests performed during hospitalization. Abdominal pelvic computed tomography (CT) revealed bowel wall thickening in the terminal ileum and multiple enlarged lymph nodes along the ileocolic artery (Fig. 1A). Even after the administration of intravenous antibiotics, his symptoms persisted, and he developed diarrhea. On hospital day 3, he suddenly developed hypotension (66/36 mmHg), requiring administration of inotropic agents. He was transferred to an intensive care unit. Laboratory tests showed a white blood cell count of 5.82 × 103/µL (segmented neutrophils, 92.1%) and platelet count of 100 × 103/µL. Serum CRP and procalcitonin levels were markedly elevated at 189.50 mg/L and 14.55 mcg/L, respectively. Serum aspartate aminotransferase/alanine aminotransferase level (61/86 U/L), pro-brain natriuretic peptide level (3,131 ng/L), prothrombin time (16.1 seconds; international normalized ratio: 1.52), activated partial thromboplastin time (42.5 seconds), fibrinogen level (18.61 g/L), and D-dimer level (0.894 µg/mL) were also elevated, but cardiac markers were within the normal range. Cardiomegaly on chest X-ray (CXR) (Fig. 1B) and hypoalbuminemia (22 g/L) were observed on hospital day 4. Based on suspected septic shock, 1 g/kg/day of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG; Green Cross Corp., Yongin, Korea) was administered for 2 days.

Fig. 1. Abdomen and chest CT, bowel ultrasonography and simple CXR. (A) Abdominal CT finding on the emergency room visit showed enlarged lymph nodes (arrow, maximum length; 2.7 cm) with diffuse bowel wall thickening. (B) Cardiomegaly were shown on CXR on hospital day 4. (C) CT finding demonstrated cardiomegaly and pleural effusion with lung parenchymal consolidation on hospital day 4. (D) On hospital day 13 (last day of hospitalization), the enlarged lymph nodes had decreased to 0.89 cm on bowel ultrasonography.

CT = computed tomography, CXR = chest X-ray.

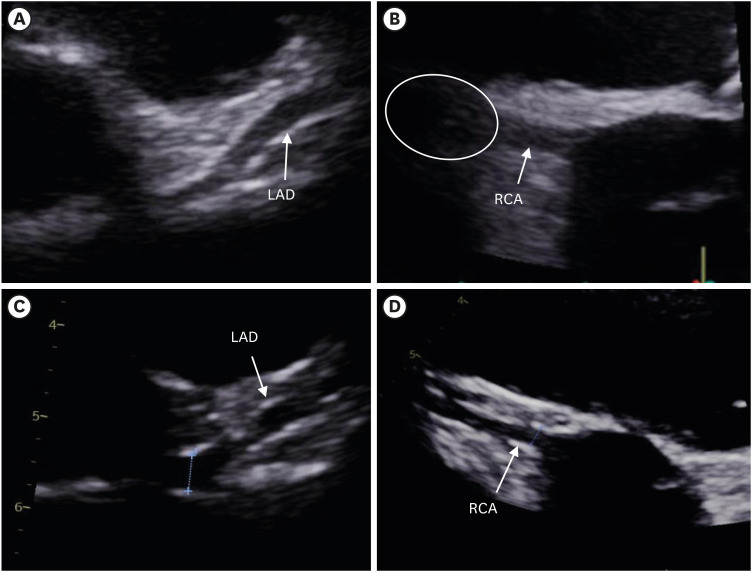

On hospital day 6, the patient's blood pressure was stable without inotropes, but he developed conjunctival injection, cracked lips (Fig. 2A), and strawberry tongue (Fig. 2B). Fig. 2 shows clinical signs consistent with the KD observed in the patients, and Fig. 3 shows coronary arteries by echocardiography. On echocardiography, the left main coronary artery was dilated, and the left anterior descending artery was not tapered (Fig. 3A). Right coronary artery (RCA) dilatation and aneurysmal changes (Fig. 3B) with mild pericardial effusion were identified. On coronary CT, RCA aneurysms or thrombi were not seen, but pleural effusion with lung parenchymal consolidation was newly detected in the absence of respiratory symptoms (Fig. 1C). We diagnosed the patient with KDSS and administered high-dose aspirin (30 mg/kg/day). His fever finally subsided on hospital day 8, but erythematous papular rash and finger desquamation were observed. He was transferred to the general ward and the aspirin dose was reduced to an antithrombotic dose (4 mg/kg/day). Desquamations of the left wrist and perianal area were seen on his last day (day 13) of hospitalisation (Fig. 2C and D). Elevated inflammation markers and coagulopathy had normalized. Cardiomegaly and pleural effusion were not detected on the CXR. Bowel ultrasonography showed that the enlarged lymph nodes were significantly reduced (maximum size from 2.73 to 0.89 cm) (Fig. 1D), and coronary artery dilatation was markedly reduced on echocardiography after 3 days of IVIG treatment (Fig. 3C and D).

Fig. 2. Clinical features consistent with Kawasaki disease. (A, B) The cracked lip and strawberry tongue newly appeared on hospital day 6. (C, D) Desquamation of the perianal area and the wrist were observed on the patient's last day of hospitalization.

Fig. 3. Echocardiography findings. (A) The LMCA (4.3 mm [Z-scorea 1.64]) and the LAD (3.8 mm [Z-score 2.23]) were not tapered. (B) The RCA (4.1 mm [Z-score 2.62]) was dilated and aneurysmal change was suspected on hospital day 6. (C) On hospital day 13, the size of the LMCA (3.9 mm [Z-score 1.04]) and LAD (2.9 mm [Z-score 0.38]) had decreased. (D) The RCA size had decreased dramatically (3.1 mm [Z-score 0.70]) on the last day of patient's hospitalization.

LMCA = left main coronary artery, LAD = left anterior descending coronary artery, RCA = right coronary artery, CAL = coronary artery length.

aThe definition of CAL has been modified, with CAL defined by a Z-score ≥ 2.5, corrected for body surface.

No pathogens were detected in the patient's blood, sputum, stool, or urine. PCR tests for the identification of pathogens in the respiratory tract and stool were negative. PCR tests for SARS-CoV-2 (Seegene, Seoul, Korea) performed using his nasopharyngeal swab, sputum, serum, urine, and stool showed negative results. However, a serum SARS-CoV-2 specific antibody test using fluorescent immunoassay (Boditech Med Inc., Chuncheon, Korea) yielded positive results for immunoglobulin G (IgG; 23.69, cut-off index: > 1.1; sensitivity = 95.8%; specificity = 96.7%) and negative results for immunoglobulin M (IgM) in his serum (0.08). To minimise the possibility of false-positive and/or non-specific reactions, we repeatedly performed various anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibody test using kits with different target antigens and methodologies. All tests showed positive results. To exclude the potential cross-reactivity of IVIG products (Green Cross Corp.) with SARS-CoV-2 antibody test kits, IVIG products manufactured from the same lots as those administered to the patient were tested. All tests using IVIG products yielded negative results (Table 1). On hospital day 13, the patient was discharged after improvement of symptoms, and he has been doing well since then without any complications.

Table 1. Serologic tests for anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies of the patient's serum and IVIG products administered to the patient.

| Variables | RDT using gold conjugate | FIA using europium particle | ELISA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manufacturer | Wells Bio Inc., Seoul, Koreaa | SD Biosensor Inc., Suwon, Korea | Boditech Med Inc., Chuncheon, Korea | SD Biosensor Inc., Suwon, Korea | PCL Inc, Seoul, Korea | ||

| Target protein | RBDb | NCP | NCP | NCP | RBDb & NCP | ||

| Cut-off value | Visual interpretation | Visual interpretation | COI ≥ 1.1 | COI ≥ 1.0 | OD ratio ≥ 1.0 | ||

| Patient's serum | IgM: negative | IgM: negative | IgM: 0.03 | IgM: 0.89 | Total ab 14.85 | ||

| IgG: positive | IgG: positive | IgG: 20.90 | IgG: 12.7 | ||||

| IVIG Lot 381B19006 | IgM/IgG | OD ratio | |||||

| Concentration | |||||||

| 10,000 | 0.06/0.17 | 0.105 | |||||

| Diluted with serum, mg/dL | |||||||

| 1/2:5,000 | 0.04/0.01 | 0.037 | |||||

| 1/4:2,500 | 0.02/0.00 | 0.034 | |||||

| 1/8:1,250 | 0.04/0.03 | 0.034 | |||||

| 1/16:625 | 0.04/0.00 | 0.026 | |||||

| 1/32:312.5 | 0.04/0.01 | 0.029 | |||||

| IVIG Lot 383A19012 | IgM/IgG | OD ratio | |||||

| Concentration | |||||||

| 10,000 | 0.06/0.10 | 0.018 | |||||

| Diluted with serum, mg/dL | |||||||

| 1/2:5,000 | 0.03/0.00 | 0.021 | |||||

| 1/4:2,500 | 0.03/0.00 | 0.011 | |||||

| 1/8:1,250 | 0.03/0.02 | 0.005 | |||||

| 1/16:625 | 0.02/0.00 | 0.018 | |||||

| 1/32:312.5 | 0.04/0.01 | 0.021 | |||||

SARS-CoV-2 = severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, IVIG = intravenous immunoglobulin, RDT = rapid diagnostic test, FIA = fluorescence immunoassay, ELISA = enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, RBD = receptor binding domain, NCP = nucleocapsid protein, COI = cut-off index, IgG = immunoglobulin G, IgM = immunoglobulin M, OD = optical density, ab = antibody.

aThis kit was assembled in Korea, using the materials manufactured by Jiangsu Medomics Medical Technology (Nanjing, China); bRBD of spike protein.

In the initial evaluation, this case was not classified as MIS-C due to a lack of history of COVID-19 infection, uncertainty in the positive antibody test for SARS-CoV-2 performed with IVIG-administered serum, and no increase in neutralizing antibody values over time. However, the positive IgG results in other types of antibody tests performed with his serum obtained 2 months after discharge proved that he has been infected with COVID-19, and this case was finally confirmed as MIS-C (Supplementary Table 1).

Ethics statement

This case report is published with the consent of the patient and his parents.

DISCUSSION

There is a growing concern over emerging cases of MIS-C worldwide. MIS-C shows features similar to KD or KDSS in addition to multiple organ inflammation with elevated inflammatory markers in the blood. Although clusters of cases of MIS-C from Europe and North America have been reported during the COVID-19 pandemic, no case has been reported from Korea. Given the high prevalence of KD or KDSS in Korea, no report of MIS-C during the pandemic is unusual and merits further investigation. This difference in epidemiology may indicate why MIS-C is different from KD or KDSS, despite having similar features.

The novel multisystem inflammatory syndrome was first suggested by Verdoni et al.10 in Italy, and clusters of more cases have since been reported in Europe and the United States. Accordingly, WHO/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention issued a definition of MIS-C and urged awareness and alertness of the disease.6,11 Our case fulfils all the suggested case definitions.

It was difficult to diagnose our patient's illness and identify its causes, who was hospitalized for severe enteritis with negative PCR results for SARS-CoV-2. During admission, further symptoms consistent with MIS-C had appeared, and the patient condition improved in response to IVIG. Enteritis symptoms, such as abdominal pain or diarrhea, are rare in KD. However, enteritis symptoms appeared to be common in MIS-C. In a case series from the UK, diarrhea or abdominal pain were noted on all patients with MIS-C.12

In our patient, PCR and IgM antibody results for SARS-CoV-2 were negative, but the IgG result was positive, which may represent a prior COVID-19 infection. In a case series from the UK, the PCR results were positive in only 50% children with MIS-C; the remaining 50% children with negative PCR results showed IgG antibodies against SARS-CoV-2.12 Another report of MIS-C cases in New York demonstrated that 8 of 17 patients tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 on PCR, while the other 9 patients tested positive on serology.13 PCR yields negative results after 3–4 weeks of a SARS-CoV-2 infection. Serum IgM disappears within 6–7 weeks of infection, while IgG persists for several months.14 In previous studies, the interval between the onsets of COVID-19 and MIC-S symptoms were reported as 6 weeks for 24% patients with MIS-C (median: 21 days).7,15 Thus, although our patient had no obvious history of exposure to any COVID-19 patient, he may have been exposed to the virus at the airport or somewhere else on his way back to Korea from the Philippines. Although our patient had no respiratory symptoms of COVID-19, IgG antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 were highly positive, and lung parenchymal consolidation was detected on CT. An asymptomatic prior infection could be a cause of MIS-C in our patient.

It is unclear whether MIS-C is caused by a direct SARS-CoV-2 infection or delayed immune response after the infection. It has been suggested that antibody-dependent enhancement of hyperinflammation leads to a more severe outcome in dengue fever.16 Further, in SARS-CoV infection, anti-spike IgG reduced wound healing and provoked lung injury by skewing lung macrophage response and proinflammatory cytokines.17 Likewise, SARS-CoV-2 may induce the hyperinflammatory condition in multiple organs with the antibody-dependent mechanism.

Our patient showed overlapping features of incomplete KD and/or KDSS. However, the features differed from those of KD or KDSS in the following respects: 1) older age; 2) normal cardiac enzyme levels and function and minimal valve regurgitation; and 3) coronary dilation in the acute stage and prompt normalization within 3 days after a single IVIG treatment.18,19 In a recent multicentre study comparing MIS-C with KD, KDSS, and TSS, patients with MIS-C were older and higher levels of inflammatory markers than those with KD, KDSS, or TSS.16

There is no gold standard serological test for anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies. We used various anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibody test kits with different target antigens and methodologies to minimise the possibility of false-positive and/or non-specific reactions; all the tests yielded concordantly positive results. In addition, we evaluated IVIG products administered to the patient at serial dilutions and found that all tests using IVIG showed negative IgG results. For our patient, multiple serological tests suggested a diagnosis of COVID-19.

To our knowledge, no case of MIS-C has been reported in Korea. Thus far, cases have been concentrated in Europe and North America; however, clinicians from other countries should be aware of this novel syndrome in cases of incomplete KD or KDSS, even when there is no clear history of contact or symptoms of COVID-19, and consider immunomodulatory therapy. Further research and international cooperation are required to investigate the immunopathogenesis of COVID-19 in children.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank the Korean manufacturers for their donations of antibody test kits, Jin Yang Baek for laboratory work.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

- Conceptualization: Jung HL, Shim JY, Sol IS, Kwak JH.

- Supervision: Shim JY.

- Writing - original draft: Kim H, Ko JH, Yang A, Kim DS, Shim JW.

- Writing - review & editing: Sol IS, Kwak JH.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Serologic tests for anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies of the patient's serum conducted by the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. [Updated 2020]. [Accessed May 12, 2020]. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019.

- 2.Lee J, Kim KH, Kang HM, Kim JH. Do we really need to isolate all children with COVID-19 in healthcare facilities? J Korean Med Sci. 2020;35(29):e277. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Toubiana J, Poirault C, Corsia A, Bajolle F, Fourgeaud J, Angoulvant F, et al. Kawasaki-like multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children during the covid-19 pandemic in Paris, France: prospective observational study. BMJ. 2020;369:m2094. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DeBiasi RL, Song X, Delaney M, Bell M, Smith K, Pershad J, et al. Severe coronavirus disease-2019 in children and young adults in the Washington, DC, metropolitan region. J Pediatr. 2020;223:199–203.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morand A, Urbina D, Fabre A. COVID-19 and Kawasaki like disease: the known-known, the unknown-known and the unknown-unknown. Preprints (Basel) 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization. Case report form for suspected cases of multisystem inflammatory syndrome (MIS) in children and adolescents temporally related to COVID-19. [Updated 2020]. [Accessed July 1, 2020]. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/case-report-form-for-suspected-cases-of-multisystem-inflammatory-syndrome-(mis)-in-children-and-adolescents-temporally-related-to-covid-19.

- 7.Dufort EM, Koumans EH, Chow EJ, Rosenthal EM, Muse A, Rowlands J, et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children in New York State. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(4):347–358. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2021756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency. The update of COVID-19 in Korea as of Oct 5. [Updated 2020]. [Accessed October 5, 2020]. https://www.cdc.go.kr/board/board.es?mid=a20501000000&bid=0015.

- 9.World Health Organization. COVID-19 in the Philippines situation report 01. [Updated 2020]. [Accessed October 19, 2020]. https://www.who.int/philippines/internal-publications-detail/covid-19-in-the-philippines-situation-report-01.

- 10.Verdoni L, Mazza A, Gervasoni A, Martelli L, Ruggeri M, Ciuffreda M, et al. An outbreak of severe Kawasaki-like disease at the Italian epicentre of the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic: an observational cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10239):1771–1778. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31103-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) associated with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) [Updated 2020]. [Accessed July 1, 2020]. https://emergency.cdc.gov/han/2020/han00432.asp.

- 12.Chiotos K, Bassiri H, Behrens EM, Blatz AM, Chang J, Diorio C, et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children during the coronavirus 2019 pandemic: a case series. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2020;9(3):393–398. doi: 10.1093/jpids/piaa069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheung EW, Zachariah P, Gorelik M, Boneparth A, Kernie SG, Orange JS, et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome related to COVID-19 in previously healthy children and adolescents in New York City. JAMA. 2020;324(3):294–296. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.10374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sethuraman N, Jeremiah SS, Ryo A. Interpreting diagnostic tests for SARS-CoV-2. JAMA. 2020;323(22):2249–2251. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.8259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feldstein LR, Rose EB, Horwitz SM, Collins JP, Newhams MM, Son MBF, et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in U.S. children and adolescents. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(4):334–346. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2021680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Whittaker E, Bamford A, Kenny J, Kaforou M, Jones CE, Shah P, et al. Clinical characteristics of 58 children with a pediatric inflammatory multisystem syndrome temporally associated with SARS-CoV-2. JAMA. 2020;324(3):259–269. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.10369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu L, Wei Q, Lin Q, Fang J, Wang H, Kwok H, et al. Anti-spike IgG causes severe acute lung injury by skewing macrophage responses during acute SARS-CoV infection. JCI insight. 2019;4(4):e123158. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.123158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rowley AH, Shulman ST. The epidemiology and pathogenesis of Kawasaki disease. Front Pediatr. 2018;6:374. doi: 10.3389/fped.2018.00374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ma L, Zhang YY, Yu HG. Clinical manifestations of Kawasaki disease shock syndrome. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2018;57(4):428–435. doi: 10.1177/0009922817729483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Serologic tests for anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies of the patient's serum conducted by the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency