Abstract

Force fields based on molecular mechanics (MM) are the main computational tool to study the relationship between protein structure and function at the molecular level. To validate the quality of such force fields, high-level quantum-mechanical (QM) data are employed to test their capability to reproduce the features of all major conformational substates of a series of blocked amino acids. The phase-space overlap between MM and QM is quantified in terms of the average structural reorganization energies over all energy minima. Here, the structural reorganization energy is the MM potential-energy difference between the structure of the respective QM energy minimum and the structure of the closest MM energy minimum. Thus, it serves as a measure for the relative probability of visiting the QM minimum during an MM simulation. We evaluate variants of the AMBER, CHARMM, GROMOS and OPLS biomolecular force fields. In addition, the two blocked amino acids alanine and serine are used to demonstrate the dependence of the measured agreement on the QM method, the phase, and the conformational preferences. Blocked serine serves as an example to discuss possible improvements of the force fields, such as including polarization with Drude particles, or using tailored force fields. The results show that none of the evaluated force fields satisfactorily reproduces all energy minima. By decomposing the average structural reorganization energies in terms of individual energy terms, we can further assess the individual weaknesses of the parametrization strategies of each force field. The dominant problem for most force fields appears to be the van der Waals parameters, followed to a lesser degree by dihedral and bonded terms. Our results show that performing a simple QM energy optimization from an MM-optimized structure can be a first test of the validity of a force field for a particular target molecule.

Keywords: molecular mechanics, quantum mechanics, AMBER, CHARMM, GROMOS, OPLS

1. Introduction

Computer simulations have become an indispensable tool to study processes involving proteins, nucleic acids, lipid membranes, and drug-like molecules. Although these systems are very different, all simulations share some common features and challenges. The two fundamental prerequisites to correctly capture the driving free energies of a system are the accurate description of inter- and intramolecular interactions and the adequate sampling of all relevant conformations [1–3]. These two requirements are in conflict with each other, since a more sophisticated description of molecular interactions involves higher computational costs, which limits the capability to search through a multitude of different possible conformations. In terms of the balance between these two requirements, one can distinguish between classical force fields based on molecular mechanics (MM) and quantum-mechanical (QM) methods.

MM force fields are fast and well suited for sampling, but involve many approximations that limit their accuracy (see [4], for a review). Their potential-energy function U is a sum of simple terms [5]. The molecular structure is maintained by harmonic functions for bond stretching, bond-angle bending, and out-of-plane distortions (improper dihedrals), while Fourier expansions are used for the dihedral-angle torsions. Non-bonded interactions include the van der Waals interactions, which are modelled by a Lennard-Jones potential, and electrostatic interactions based on point charges. Thus, electronic polarization is usually not modelled explicitly, and chemical bonds cannot be formed or broken. QM approaches [6–14] are based on molecular orbital calculations and combine a heavy computational burden with highly accurate interactions. They capture the correct physical behaviour, but are limited in terms of the size and time scale of the processes that can be studied (usually only hundreds of atoms on the time scale of picoseconds).

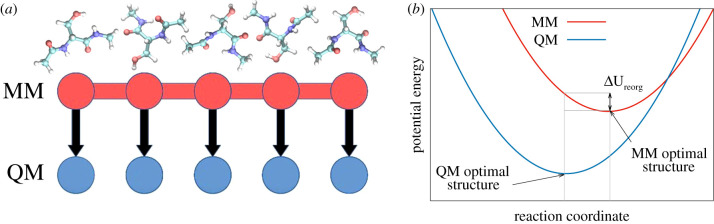

To resolve the conflict between the computational costs of sampling on the one hand and physical faithfulness on the other hand, it is possible to resort to a multi-scale approach (see [15–27]) that employs an MM representation to perform the sampling, followed by post-processing of the MM trajectory with a QM Hamiltonian to obtain the correct ensemble (figure 1a). This approach has led to significantly improved results in the recent past [29–31]; however, there are several cases where the multi-scale approach fails to converge. This can be explained by the disparity of the respective MM and QM potential-energy surfaces. If the MM potential-energy surface is not representative for the QM one, most sampled conformations will reside in high energy areas of phase space, and, consequently, only marginally contribute to the final result.

Figure 1.

(a) Snapshots from free-energy calculations based on molecular mechanics (MM) simulations can be post-processed in a highly parallel fashion with quantum-mechanical (QM) potential-energy evaluations to obtain QM-corrected free-energy differences. Each arrow represents an alchemical transformation from the MM Hamiltonian to the QM Hamiltonian. (b) The alchemical transformation at each snapshot converts the MM potential-energy function (red) to the QM potential (blue). Depending on the position along the one-dimensional reaction coordinate that connects the two end states, different potential-energy differences between MM and QM can be obtained. A simple metric for the convergence of free-energy calculations is the structural reorganization energy () [28]. It is characterized by the MM potential-energy difference between the QM optimal structure and the MM optimal structure. Thus, it directly measures the energetic costs for the MM force field to sample the correct QM structure. is also related to the variance of the potential-energy difference distribution, which determines the variance of the free-energy estimate.

Since the phase-space overlap between MM and QM can only be determined by simulating the whole phase space, it is difficult to predict problematic cases a priori. However, by using linear response theory [32–35], and taking loans from Marcus theory [36], it is possible to roughly estimate the expected phase-space overlap. The variance of a free-energy result based on the Zwanzig equation [37] is proportional to the variance of the probability distribution of the underlying potential-energy differences between the two end states [38–41]. For two shifted harmonic oscillators, the potential-energy difference probability distribution is a Gaussian with a width that is directly proportional to the structural reorganization energy (, cf. figure 1b). Here, the structural reorganization energy is defined as the MM potential-energy difference between the structure of the respective QM energy minimum and the structure of the closest MM energy minimum. can be obtained by a simple MM energy minimization starting from the QM-optimized structure. The expected variance of the free-energy estimate then becomes

| 1.1 |

where kB is the Boltzmann constant, T the absolute temperature, and n represents the number of independent potential-energy difference samples. A thorough analysis of equation (1.1) is provided in [28], yielding R2 between 0.66 and 0.97 for several series of free-energy simulations. Notably, equation (1.1) only holds if there is one dominant energy well in the system. In principle, if there are multiple low-lying energy minima, equation (1.1) has to be solved for each well and weighted according to its Boltzmann probability to predict the variance of a free-energy estimate. However, Boltzmann weighting based on gas-phase energies can neglect rotational states that might become relevant in the folded protein or in a binding event. To account for such eventualities, we use the unweighted average structural reorganization energies, since we are primarily interested in using them as a measure for the difficulty for the MM representation to sample all correct QM minima.

Here, we employ the average structural reorganization energies from a series of conformational states as a measure for the faithfulness of the MM representation towards a QM energy surface. Given the eminent importance of proteins in biomedical applications, we focus on average structural reorganization energies of blocked amino acids. We first illustrate the faithfulness for blocked alanine and serine, using the CHARMM36 force field [42] as the MM representation, and BLYP/6-31G(d) [43–45], as well as M06-2X/6-31G(d) [46], as the QM target Hamiltonians. This demonstrates the variability of the structural reorganization energies with respect to the target QM method and the secondary structure. We also examine the differences between conformations in the gas phase and in aqueous solution. In a second step, we ask the question which MM force field among AMBER [47,48], CHARMM [42,49], GROMOS [50,51] and OPLS [52] more closely reproduces all QM energy minima occurring in 14 neutral amino acids according to the refined YMPJ conformer database [53,54]. Blocked serine is used as an example to discuss possible improvements by the CHARMM polarizable force field [55–57], or using tailored force fields based on QM optimizations [58]. In the following, we first discuss the methodological details, followed by presenting the results and our conclusions.

2. Methods

2.1. Alanine and serine

The MM calculations of N-acetyl-alanine-methylamide and N-acteyl-serine-methylamide were carried out with the CHARMM simulation package [59,60] and QM/MM calculations were conducted with Q-Chem [6], using the CHARMM/Q-Chem interface [61]. The initial backbone conformations of N-acteyl-alanine-methylamide and N-acteyl-serine-methylamide were generated by using harmonic restraints with a force constant of 418 kJÅ− 2, with equilibrium torsion angles of ϕ = −135°, ψ = 135° for the β-sheet structure, ϕ = − 60°, ψ = 150° for the PP2-helix, ϕ = − 60°, ψ = − 40° for the α-helix, and ϕ = 60°, ψ = 40° for the left-handed helix with 30 steps of steepest descent and 150 steps of adopted basis Newton–Raphson (ABNR) energy minimization. In the gas phase, the QM-optimized structures were generated with 500 steps of ABNR energy minimization. For the determination of the MM-optimized structure, the QM-optimized structures were minimized again for 500 steps of ABNR energy minimization with the CHARMM36 force field. In the gas phase, only one structure was employed to determine . For the structures in aqueous solution, 1683 TIP3P water molecules were added and the system was simulated for 0.5 ns with constant pressure and a time step of 1 fs. Subsequently, eight 0.1 ns simulations with different initial velocities were used to generate different solvent structures. The structural reorganization energies for aqueous solution listed in table 1 are averages of energy minimizations based on those eight different solvent structures and were performed while keeping the water coordinates fixed. The QM/MM-optimized structures in aqueous solution were generated with 500 steps of ABNR energy minimization while keeping the surrounding MM water molecules frozen. The solute was treated quantum-mechanically, and electrostatic embedding was used for the QM/MM solute–solvent interactions. The QM/MM→QM/MM structural reorganization energies in aqueous solution between M06-2X/6-31G(d) and BLYP/6-31G(d) were calculated by performing 250 steps of ABNR energy minimization with BLYP/6-31G(d), starting from a structure that was previously optimized with M06-2X/6-31G(d). The QM structural reorganization energies in the gas phase between M06-2X/6-31G(d) and BLYP/6-31G(d) were calculated by performing 150 steps of ABNR energy minimization.

Table 1.

Average structural reorganization energies for blocked alanine and serine, using the CHARMM36 force field, and including the contributions from different MM energy terms. Two target QM Hamiltonians are used (BLYP/6-31G(d) and M06-2X/6-31G(d)), and each comparison was performed once in the gas phase and once in aqueous solution using QM/MM with TIP3P water. Four different backbone conformations are considered: β-sheet, PP2-helix, α-helix and left-handed helix (left-h. helix). Due to the omission of some energy terms in this table (e.g. dihedral and CMAP terms), the contributions do not necessarily add up to 100%. All reorganization energies are in kJ mol−1.

| alanine |

serine |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| structure | Bonda | Angleb | Elecc | vdWd | Bonda | Angleb | Elecc | vdWd | ||

| gas phase BLYP/6-31G(d) | ||||||||||

| β-sheet | 22.9 | 48% | 7% | 11% | 2% | 31.2 | 54% | 15% | 8% | 4% |

| PP2-helix | 26.6 | 74% | 4% | 10% | 2% | 24.8 | 76% | 18% | −6% | 3% |

| α-helix | 28.2 | 67% | 6% | 10% | 4% | 27.4 | 68% | 17% | 7% | 7% |

| left-h. helix | 28.2 | 57% | 13% | −3% | 6% | 33.9 | 55% | 4% | −9% | 5% |

| gas phase M06-2X/6-31G(d) | ||||||||||

| β-sheet | 15.9 | 27% | 2% | 9% | 9% | 28.1 | 25% | 11% | 6% | 27% |

| PP2-helix | 18.4 | 53% | −9% | 26% | 18% | 16.4 | 43% | 2% | 10% | 31% |

| α-helix | 25.2 | 61% | 13% | 6% | 40% | 16.2 | 43% | 3% | 10% | 30% |

| left-h. helix | 14.7 | 24% | 1% | 1% | 13% | 33.7 | 21% | −6% | 42% | |

| aqueous phase BLYP/6-31G(d) | ||||||||||

| β-sheet | 22.1 | 63% | −6% | 1% | 17% | 26.6 | 68% | 7% | −12% | 27% |

| PP2-helix | 24.3 | 56% | −12% | −3% | 30% | 28.2 | 60% | 0% | −14% | 31% |

| α-helix | 24.5 | 60% | −4% | −12% | 24% | 27.8 | 64% | 7% | −18% | 19% |

| left-h. helix | 24.9 | 71% | −20% | −5% | 37% | 26.0 | 73% | −10% | −12% | 36% |

| aqueous phase M06-2X/6-31G(d) | ||||||||||

| β-sheet | 17.1 | 41% | −10% | 11% | 34% | 19.6 | 36% | 6% | 8% | 39% |

| PP2-helix | 23.5 | 27% | −16% | 7% | 52% | 28.0 | 22% | −1% | 2% | 55% |

| α-helix | 22.0 | 31% | −10% | −1% | 50% | 24.1 | 26% | 5% | 3% | 37% |

| left-h. helix | 26.0 | 33% | −25% | 8% | 71% | 26.2 | 26% | −14% | 9% | 66% |

aContributions to based on mismatches of the bond lengths in %. bContributions to based on mismatches of the bond angles in %. cContributions to based on electrostatic interactions in %. dContributions to based on Lennard-Jones interactions in %.

2.2. Energy minima of the 14 neutral amino acids

Based on the structures of the YMPJ conformer database [54] and the refinements from [53], all energy minima of the N-acetyl-X-methylamide versions of the 14 neutral amino acids Ala (10 minima), Asn (12 minima), Cys (23 minima), Gln (20 minima), Gly (8 minima), Ile (24 minima), Leu (26 minima), Met (56 minima), Phe (26 minima), Pro (5 minima), Ser (23 minima), Thr (17 minima), Tyr (16 minima) and Val (14 minima) were evaluated. The conformations were generated with the MP2/cc-pVTZ level of theory [62,63]. The energy minimizations for the CHARMM, AMBER and OPLS force fields were performed with the CHARMM simulation package, using the respective natural constants. This procedure ensures that the starting coordinates maintained a precision of 10−10 Å (e.g. the pdb format only supports a precision of 10− 3 Å, which can lead to artefacts in the determination of the structural reorganization energies). The energy minimizations involved 100 steps of steepest descent, followed by up to 10 000 steps of ABNR energy minimization. For the GROMOS 54A7 force field [50,51], the energy minimization was performed with the GROMOS simulation package [64], using up to 10 000 steps of steepest descent for the energy minimization.

2.3. Possible improvement strategies

Analogously to the previous subsection, the CHARMM Drude polarizable force field [55,56] was employed to determine the structural reorganization energies of blocked serine. To illustrate the effect of adjusting the bonded parameters, tailored force field parameters were generated from the global energy minimum structure of blocked serine in the YMPJ conformer database (xab.xyz). Every atom was assigned to a unique atom type to allow unique equilibrium bond length and angle values, and the values were populated with the QMFIX command in the FREN module of CHARMM [58]. Charges and Lennard-Jones parameters were retained from the original parametrization. The MM→QM values with the OM2 semi-empirical method [65,66] were calculated by starting from the MM-optimized structure and performing an energy minimization with the MNDO program [13].

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Dependence on the quantum mechanical method and the solvent environment

Before comparing the faithfulness of different MM force fields to a QM Hamiltonian, it is indispensable to point out the dependence of the structural reorganization energies on the target QM method, as well as the solvent environment. Different QM methods can lead to a variety of rankings in terms of the relative energies of conformers [53,54,67]. To evaluate those aspects, we resort to the blocked amino acids alanine and serine. The solvent affinity of blocked serine strongly depends on the backbone conformation, due to hydrogen bond formation between the peptide groups of the backbone and the side-chain hydroxyl group (the so-called self-solvation effect) [68–70]. To properly account for this effect in a simulation, it is necessary to consider all relevant backbone geometries corresponding to β-sheet, PP2-helix, α-helix and left-handed helix structures.

The two target QM Hamiltonians, BLYP/6-31G(d) and M06-2X/6-31G(d), were chosen because they yielded very different QM/MM hydration free energies in previous studies [29,58,71,72]. The average deviation of the hydration free energies from BLYP/6-31G(d)/TIP3P and M06-2X/6-31G(d)/TIP3P was 23%, while the average deviation of M06-2X/6-31G(d)/TIP3P hydration free energies from the MP2/aug-cc-pVDZ/TIP3P results was only 2% [58]. Thus, BLYP/6-31G(d) and M06-2X/6-31G(d) represent two opposite extremes among the considered density functional theory (DFT) methods in terms of their solvent affinity, with M06-2X/6-31G(d) being significantly more hydrophilic than BLYP/6-31G(d) or the experimental data. This was rationalized in terms of their ratios of Hartree–Fock exchange, which leads to different levels of charge separation, and also different bond lengths [71]. For the 4 × 8 structures in aqueous solution, the average structural reorganization energies between M06-2X/6-31G(d) and BLYP/6-31G(d) amount to 10.9 ± 0.8 kJ mol−1 for alanine, and 12.1 ± 0.7 kJ mol−1 for serine. The low standard deviations indicate that the structural reorganization energies between the two QM methods are almost independent of the surrounding water structure or the backbone conformation. In the gas phase, the average structural reorganization energies between M06-2X/6-31G(d) and BLYP/6-31G(d) amount to 12.1 ± 0.8 kJ mol−1 for alanine and 13.6 ± 0.3 kJ mol−1 for serine.

The corresponding average structural reorganization energies for the CHARMM36 force field relative to the BLYP/6-31G(d) and M06-2X/6-31G(d) DFT methods are shown in table 1. The total average structural reorganization energy between the QM structures and the MM structures amounts to 24.5 kJ mol−1 for blocked alanine and serine. This is twice as high as the total average QM structural reorganization energy between BLYP/6-31G(d) and M06-2X/6-31G(d) of 12.2 kJ mol−1. The average MM structural reorganization energy corresponds to ca 10 kBT at room temperature, which would lead to exceedingly high variances in free-energy calculations according to equation (1.1) [28]. In addition, the total average structural reorganization energy is higher for BLYP (26.7 kJ mol−1) than for M06-2X (22.2 kJ mol−1), which indicates that the CHARMM36 force field is more compatible with M06-2X. Moreover, the total average structural reorganization energy in aqueous solution (24.4 kJ mol−1) is about the same as in the gas phase (24.5 kJ mol−1). This either indicates cancellation of errors between the phases, or that the main source of errors is not affected by the change of the electrostatic environment.

Especially in the gas phase one can observe a large variation of the reorganization energies in response to conformational changes. The standard deviations of the average over all four secondary structures are 2.5 and 4.0 kJ mol−1 for alanine and serine with BLYP/6-31G(d), and 4.7 and 8.7 kJ mol−1 for M06-2X/6-31G(d). This indicates that the errors of BLYP/6-31G(d) are more systematic. A similar trend can be observed in aqueous solution, where the standard deviations of the values are 1.3 and 1.0 kJ mol−1 for alanine and serine with BLYP/6-31G(d), and 3.7 and 3.6 kJ mol−1 for M06-2X/6-31G(d). Thus the variations in aqueous solution are smaller than in the gas phase. However, the variations are significantly larger than the standard deviations of the QM structural reorganization energies (0.3 to 0.8 kJ mol−1). This is probably an effect of the Boltzmann weighting in the parametrization procedure of the MM force field, as low-energy secondary structures play a more prominent role in protein dynamics.

Table 1 also lists the contributions of the individual energy terms of the force field to the average structural reorganization energies in percent. Positive components indicate a destabilization of the QM structure, while negative values imply a stabilization of the optimal QM geometry within the MM force field. However, because of the coupling between the different energy terms, a rigorous decomposition is not possible [73,74]. A surprising result in both the gas phase and aqueous solution is the dominance of discrepancies due to the bonded structure of the MM force field (on average 49%), rather than differences that arise from non-bonded interactions (on average 2% for electrostatics and 27% for van der Waals interactions). On average, each bond length of the MM-optimized structure deviates by about 0.018 Å from the QM-optimized structure, which adds to the observed discrepancies. This holds true for several backbone conformations and both evaluated QM methods. Notably, the optimal bond length depends on the exact details of the QM method, such as the amount of Hartree–Fock exchange in DFT.

These findings are a clear indicator that the currently employed approach for bond length and bond angle parametrization is inadequate for multi-scale free energy calculations (at least for the CHARMM36 force field). The changes of the bonded structure due to the response to the local environment are not adequately described in this formalism. For example, a hydroxyl bond stretches as it is transferred from a hydrophobic environment to aqueous solution, in order to increase the interactions with the solvent [75]. Such deviations of the MM force field from the target QM function can be corrected by adjusting the bonded parameters based on the target QM function and the environment under consideration in a custom-fit approach for each individual bond. Such tailored force fields have been referred to as MM’ states [58], and have recently been shown to significantly boost the convergence of multi-scale free-energy calculations by Giese & York [76], as well as by Hudson et al. [77]. One major challenge for tailored MM’ force fields are the structural changes between different phases. This entails that currently employed thermodynamic cycles should be complemented with legs that consider the changes of the bonded structure between, for example, the gas phase and the aqueous phase. This can be straightforwardly implemented by employing a free-energy calculation or analytical corrections for the changes of the bonded terms [75,78–80] between the dummy end states of the different legs in post-processing.

3.2. Comparison of different force fields

Table 2 shows the average structural reorganization energies for different force fields over all energy minima of the 14 neutral blocked amino acids relative to the MP2/cc-pVTZ-optimized structures of the refined YMPJ conformer database [53,54]. The difference between and can serve as a measure for the variance of the reorganization energy. The force fields are listed in alphabetical order. Table 2 also includes the average contributions of the individual MM energy terms, such as bond stretching (Bond), angle bending (Angle), dihedral angles (Dihedral), improper dihedrals (Impr), van der Waals interactions (vdW) and electrostatic interactions (Elec). The CHARMM36 force field also incorporates a cross-term correction potential for the backbone dihedrals (CMAP).

Table 2.

Average structural reorganization energies for the 14 neutral blocked amino acids in the gas phase with different force fields, including root mean squared structural reorganization energies and the average contributions from different MM energy terms. The are relative to the MP2/cc-pVTZ-optimized structures of the YMPJ conformer database [53,54].

| AMBER ff94 | AMBER ff14SB | ||

| 31.6 kJ mol−1 | 33.1 kJ mol−1 | ||

| 35.7 kJ mol−1 | 35.7 kJ mol−1 | ||

| Bonda | 5% | Bonda | 5% |

| Angleb | −1% | Angleb | 6% |

| Dihedralc | 21% | Dihedralc | 24% |

| Imprd | 5% | Imprd | 6% |

| vdWe | 42% | vdWe | 39% |

| Elecf | 27% | Elecf | 20% |

| CHARMM22 | CHARMM36 | ||

| 40.5 kJ mol−1 | 38.0 kJ mol−1 | ||

| 42.8 kJ mol−1 | 39.3 kJ mol−1 | ||

| Bonda | 23% | Bonda | 24% |

| Angleb | 5% | Angleb | 4% |

| Dihedralc | 19% | Dihedralc | 16% |

| Imprd | 12% | Imprd | 13% |

| vdWe | 32% | vdWe | 35% |

| Elecf | 9% | Elecf | 5% |

| CMAPg | 3% | ||

| GROMOS 54a7 | OPLS-AA | ||

| 30.5 kJ mol−1 | 35.5 kJ mol−1 | ||

| 42.1 kJ mol−1 | 38.4 kJ mol−1 | ||

| Bonda | − 29% | Bonda | 7% |

| Angleb | − 5% | Angleb | 4% |

| Dihedralc | 15% | Dihedralc | 18% |

| Imprd | 14% | Imprd | 5% |

| vdWe | 74% | vdWe | 64% |

| Elecf | 32% | Elecf | 3% |

aContributions to based on mismatches of the bond lengths in %. bContributions to based on mismatches of the bond angles in %. cContributions to based on dihedral angles in %. dContributions to based on improper dihedrals in %. eContributions to based on Lennard-Jones interactions in %. fContributions to based on electrostatic interactions in %. gContributions to based on cross-term CMAP potential in %.

The best performance of an all atom force field in terms of average structural reorganization energies was attained with AMBER ff94 ( kJ mol−1). Based on equation (1.1), this would lead to a variance of ca 105 kJ mol−1 in a free-energy calculation at 298 K using 1 million independent data points. This is unacceptably high. The AMBER ff14SB force field performs similarly, but exhibits a higher of 33.1 kJ mol−1. The contributions from the individual energy terms for the AMBER ff94 and AMBER ff14SB force fields indicate that the main reason for the observed discrepancies between MM and QM lies in the van der Waals parameters (42 and 39%, respectively), followed by dihedral terms (21 and 24%, respectively) and electrostatic charges (27 and 20%, respectively). The bond angle and improper dihedral parameters appear to be well parametrized compared to the QM method as they only contribute with up to 6% to the average structural reorganization energy. However it should be noted that all force-field parameters are coupled to each other and therefore cannot be optimized independently. The individual contributions are merely an indicator for the need of improvement.

The worst performance in terms of average structural reorganization energies is observed for the CHARMM22 force field with a of 40.5 kJ mol−1. The CHARMM36 force field performs slightly better with a of 38.0 kJ mol−1, which is also in line with the range of structural reorganization energies observed in table 1 of the previous section. Also in the CHARMM force fields the van der Waals parameters dominate the reorganization energies with contributions of 32 and 35%. However, this is the smallest contribution from the van der Waals parameters in the whole dataset. In contrast to the other force fields, the contribution from the bond terms is significant with 23 and 24%. This is somewhat surprising, given that the bond lengths can be determined experimentally and are probably the easiest parameters to adjust. However, there seems to be no clear systematic difference between the bonded parameters of CHARMM22 and, for example, OPLS-AA. The average difference between the equilibrium bond lengths of alanine is ca 0.004 Å, and the mean absolute difference is 0.018 Å. The largest differences are observed for carbon–carbon bonds (deviations of ca − 0.03 Å), followed by the carbon–hydrogen bonds (deviations of ca +0.02 Å). The force constants tend to be weaker in CHARMM22 (on average −9%). Other contributions include the dihedral terms (19 and 16%) and improper dihedrals (12 and 13%). In CHARMM36, the CMAP backbone correction seems to have little impact on the deviations arising from the dihedral terms. This indicates that the main deviations arise from the side chain dihedral parameters, which are unaffected by the CMAP potential. Interestingly, while the bonded terms lead to significant deviations, the non-bonded van der Waals and electrostatic parameters taken together are the most faithful in the whole set.

The GROMOS 54a7 united atom force field exhibits the lowest with 31 kJ mol−1 but also the highest variance with a of 42.1 kJ mol−1. The high reflects the poor performance for proline, which exhibits a of 113.2 kJ mol−1. It is also remarkable with respect to the bond and angle terms, which actually stabilize the correct QM structure. This is evidenced by the negative contributions with − 29% and − 5%, respectively. On the other hand, the contribution from the van der Waals parameters is the highest in the whole dataset with 74%. The same holds true for the electrostatic interactions with a contribution of 32%. This most likely reflects the united atom formalism, where the hydrogens and the carbon atoms of aliphatic groups are treated as a single particle. For practical applications in multi-scale simulations, the GROMOS force fields require a reliable mapping method to determine the missing hydrogen positions for the QM calculations. Finally, the OPLS-AA force field yields a of 35.5 kJ mol−1. In comparison to most other force fields, the bond, angle, dihedral and electrostatic charge parameters seem to be nearly perfect. There are only two major weaknesses. The contribution from the van der Waals interactions is the second-highest value in the dataset with 62%, and the dihedral potentials lead a contribution of 18%.

Overall, it is remarkable to observe how the different parametrization philosophies of classic force fields lead to distinctive characteristics in the contributions to the structural reorganization energies. However, the different force fields also influenced each other substantially [4]. For example, OPLS used the same bonded parameters as AMBER, which is reflected in the comparable contributions to . On the other hand, many van der Waals parameters of OPLS were incorporated in AMBER ff94 [47], but yet the respective contributions in table 2 are rather different (42% or 13.3 kJ mol−1 for AMBER ff94, and 64% or 22.7 kJ mol−1 for OPLS-AA). This is most likely a reflection of the influence of the other parameters (e.g. van der Waals parameters that were developed independently of the charge scheme).

3.3. Possible improvement strategies

One major improvement strategy for current force fields is the introduction of polarization [67,81–83]. Table 3 illustrates the effect of a naive use of the CHARMM Drude polarizable force field [55–57] on of blocked serine. The worst-performing force field of table 2, CHARMM22, serves as a reference. Unfortunately, due to a mismatch of the bond-angle terms of the blocking groups, the Drude force field performs significantly worse than CHARMM22, yielding a of 126.1 kJ mol−1. The high average structural reorganization energy of the Drude force field shows that calculating at least one relative to a QM-minimized structure is an efficient way to detect errors of a force field for a molecule of interest before performing a simulation. In this case, one can also take an MM-optimized structure and perform a QM energy optimization to determine the MM→QM . For example, using the OM2 semi-empirical method [65] it takes nine seconds to calculate a MM→QM of 100.4 kJ mol−1, which can serve as an indicator that the force field is probably not reliable for this particular molecule.

Table 3.

Average structural reorganization energies for blocked serine in the gas phase with different possible improvement strategies. The are relative to the MP2/cc-pVTZ-optimized structures of the YMPJ conformer database [53,54]. All values are in kJ mol−1.

| CHARMM22 | CHARMM-Drude | ||

| 39.5 | 126.1 | ||

| 42.0 | 127.9 | ||

| Bonda | 7.6 | Bonda | 3.6 |

| Angleb | 3.4 | Angleb | 91.9 |

| Dihedralc | 7.4 | Dihedralc | 3.0 |

| Imprd | 5.1 | Imprd | 7.1 |

| vdWe | 11.4 | vdWe | 22.1 |

| Elecf | 4.6 | Elecf | −3.9 |

| CMAPg | 2.2 | ||

| CHARMM22′ | CHARMM-Drude″ | ||

| 32.9 | 39.4 | ||

| 35.6 | 44.0 | ||

| Bonda | −1.7 | Bonda | −3.2 |

| Angleb | 4.4 | Angleb | −3.2 |

| Dihedralc | 7.6 | Dihedralc | 4.6 |

| Imprd | 5.1 | Imprd | 7.1 |

| vdWe | 12.7 | vdWe | 22.3 |

| Elecf | 4.8 | Elecf | 14.7 |

| CMAPg | 12.7 | ||

′Bond length force field parameters were adapted to the QM minimal energy structure with the QMFIX command [58]. ′′Bond length and bond angle force field parameters were adapted to the QM minimal energy structure with the QMFIX command [58]. aContributions to based on mismatches of the bond lengths in kJ mol−1. bContributions to based on mismatches of the bond angles in kJ mol−1. cContributions to based on dihedral angles in kJ mol−1. dContributions to based on improper dihedrals in kJ mol−1. eContributions to based on Lennard-Jones interactions in kJ mol−1. fContributions to based on electrostatic interactions in kJ mol−1. gContributions to based on cross-term CMAP potential in kJ mol−1.

Coming back to the performance of the CHARMM Drude force field in table 3, the improved electrostatic energy contribution (Elec = − 3.9 kJ mol−1 compared to +4.6 kJ mol−1 with CHARMM22) shows that the inclusion of Drude particles does indeed improve the electrostatic representation compared to the additive force field. Also the bond (Bond = 3.6 kJ mol−1 compared to 7.6 kJ mol−1) and dihedral parameters (Dihedral = 3.0 kJ mol−1 compared to 7.4 kJ mol−1) of the Drude force field are superior to the CHARMM22 force field. However, since the angle and the van der Waals (vdW = 22.1 kJ mol−1 compared to 11.4 kJ mol−1) contributions are significantly higher than in CHARMM22, the Drude force field performs worse. This indicates again that the van der Waals parameters are a major obstacle for reaching low structural reorganization energies.

A simple strategy to address the problem of mismatching bond and angle parameters is to populate the equilibrium values of the force field with the values from the QM-optimized structure. This can be achieved with the QMFIX command in CHARMM [58]. The performance of adjusting the bond length terms of the CHARMM22 force field (denoted as CHARMM22’) and adapting both the bond and angle parameters of the Drude force field (CHARMM-Drude”) are shown in the bottom part of table 3. Merely adjusting the bond lengths reduces the of the CHARMM22 force field to 32.9 kJ mol−1. By using the same strategy for all considered amino acids, an average of 33.3 kJ mol−1 is obtained. Thus, the performance of the tailored CHARMM22’ force field is comparable to the performance of the AMBER ff14SB force field. By adjusting both the bond and the angle terms, the of the CHARMM-Drude” force field for blocked serine drops to 39.4 kJ mol−1. This shows that the main source of discrepancies in this particular case were the angle parameters. However, the resulting performance of the Drude force field is comparable to the original CHARMM22 force field. The limiting factors for the CHARMM-Drude” force field are the van der Waals parameters, the electrostatics, and the CMAP potential. The high contribution from the electrostatic terms shows that the improvement of some parameters can lead to a massive deterioration of the contributions from other energy parameters, because all energy terms are coupled to each other. Thus, there is no simple recipe to improve the parameters.

4. Conclusion

The presented results demonstrate that none of the evaluated force fields adequately reproduces the QM energy minima of 14 blocked amino acids in the gas phase based on the MP2/cc-pVTZ level of theory. Some discrepancies are to be expected, as the biomolecular force fields are parametrized for aqueous solution. Therefore, some of the findings reflect the principal limitations of additive force fields, or were deliberately taken into account during the parametrization process [84]. However, since the main difference between the gas phase and aqueous solution is the change of the electrostatic environment, this mainly entails some deviations due to the fixed point charges. The average structural reorganization energies over all considered energy minima reside in a range between 30.5 kJ mol−1 and 40.5 kJ mol−1. Thus, no force field clearly outperforms the others. To put these numbers into perspective, one can also consider the average structural reorganization energy between BLYP/6-31G(d) and M06-2X/6-31G(d) for blocked alanine and serine, which amounts to 12.2 kJ mol−1. The discrepancies between MM and QM are approximately two to three times higher than the discrepancies between the two different QM methods. Since the variance of a free-energy extrapolation from MM to QM depends on the exponential of the structural reorganization energy (equation (1.1)), attempts to reweight from MM to QM will most likely lead to extremely poor precision.

In terms of , the GROMOS 54a7 force field performed best, followed by AMBER ff94, AMBER ff14SB, OPLS-AA, CHARMM36 and CHARMM22. However, all force fields exhibited different shortcomings. For example, the GROMOS 54a7 force field performs exceedingly well in terms of bonded terms, but exhibits large discrepancies due to its van der Waals interactions. The CHARMM force fields, on the other hand, perform well in terms of non-bonded interactions, but fail in terms of their bonded terms. The OPLS-AA force field is well balanced, except for its van der Waals parameters. The AMBER force fields exhibit a relatively low contribution from the van der Waals parameters, but at the cost of higher discrepancies due to the electrostatic charges. Overall, given the different parametrization strategies, an appropriately chosen consensus approach that combines simulations from multiple MM force fields might lead to improved results.

As illustrated for blocked alanine and serine, high structural reorganization energies were also obtained for the DFT methods BLYP/6-31G(d) and M06-2X/6-31G(d). Thus, this is not an artefact of the employed target QM method. While the inclusion of explicit solvent might decrease the deviations from the QM energy minima, the discrepancies for the CHARMM36 force field are still substantial with average structural reorganization energies between 17.1 and 28.2 kJ mol−1. A similar performance can be expected for other force fields, as the structural reorganization energies strongly depend on the QM method, phase, and conformational preferences.

The results further highlight that the use of MM force fields for sampling in multi-scale free-energy simulations requires a prior tuning of the parameters to the target QM Hamiltonian. Especially challenging are the van der Waals parameters, which account for 32–74% of the average structural reorganization energies. Dihedral (15–24%) and bonded terms (− 29 to +24%) can also play a significant role in some force fields. Therefore, the employment of either tailored MM’ fields [58,76,77], or force fields that were completely derived from QM [85–89] will most likely play a more important role in the future of multi-scale applications that combine MM with QM.

Acknowledgements

This work would not have been possible without the support and guidance of Walter Thiel, who recently passed away and, therefore, could not be included as an author. We dedicate this paper to his memory. G.K. would also like to especially thank Alexander Nikiforov for pointing out the YMPJ conformational database, as well as Bernard R. Brooks, Pavlo O. Dral, Richard W. Pastor, Frank C. Pickard and Yihan Shao for very helpful discussions. The authors also thank the anonymous reviewers for their input.

Data accessibility

This article has no additional data.

Authors' contributions

The work was performed by G.K. The data were analysed by G.K. and S.R. The manuscript was prepared by G.K. and S.R.

Competing interests

We declare we have no competing interest.

Funding

This work was partially supported by the Max Planck Society. Parts of the research leading to these results received funding from the European Research Council through an ERC Advanced grant (OMSQC).

References

- 1.Christ CD, Mark AE, van Gunsteren WF. 2010. Basic ingredients of free energy calculations: a review. J. Comput. Chem. 31, 1569–1582. ( 10.1002/jcc.21450) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hansen N, van Gunsteren WF. 2014. Practical aspects of free-energy calculations: a review. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 10, 2632–2647. ( 10.1021/ct500161f) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pohorille A, Jarzynski C, Chipot C. 2010. Good practices in free-energy calculations. J. Phys. Chem. B 114, 10235–10253. ( 10.1021/jp102971x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Riniker S. 2018. Fixed-charge atomistic force fields for molecular dynamics simulations in the condensed phase: an overview. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 58, 565–578. ( 10.1021/acs.jcim.8b00042) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levitt M, Lifson S. 1969. Refinement of protein conformations using a macromolecular energy minimization procedure. J. Mol. Biol. 46, 269–279. ( 10.1016/0022-2836(69)90421-5) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shao Y. et al. 2006. Advances in methods and algorithms in a modern quantum chemistry program package. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 8, 3172–3191. ( 10.1039/B517914A) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aquilante F. et al. 2016. Molcas 8: new capabilities for multiconfigurational quantum chemical calculations across the periodic table. J. Chem. Phys. 37, 506–541. ( 10.1002/jcc.24221) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parrish RM. et al. 2017. Psi4 1.1: a open-source electronic structure program emphasizing automation, advanced libraries, and interoperability. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 13, 3185–3197. ( 10.1021/acs.jctc.7b00174) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neese F. 2018. Software update: the ORCA program system, version 4.0. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Comput. Mol. Sci. 8, e1327 ( 10.1002/wcms.1327) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.TURBOMOLE v6.3 2011 A development of the University of Karlsruhe and Forschungszentrum Karlsruhe GmbH, 1989–2007; available from www.turbomole.com.

- 11.Stewart JJP. 2016. MOPAC2016, Stewart computational chemistry, Colorado Springs, CO; available from http://openmopac.net.

- 12.Aradi B, Hourahine B, Frauenheim T. 2007. DFTB+, a sparse matrix-based implementation of the DFTB method. J. Phys. Chem. A 111, 5678–5684. ( 10.1021/jp070186p) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thiel W. 2006. MNDO2005, version 7.1. Mülheim an der Ruhr, Germany: Max-Planck-Institut für Kohlenforschung.

- 14.Frisch MJ. et al. 1998. Gaussian 98. Pittsburgh, PA: Gaussian, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Luzhkov V, Warshel A. 1992. Microscopic models for quantum mechanical calculations of chemical processes in solutions: LD/AMPAC and SCAAS/AMPAC calculations of solvation energies. J. Comput. Chem. 13, 199–213. ( 10.1002/jcc.540130212) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gao J, Xia X. 1992. A priori evaluation of aqueous polarization effects through Monte Carlo QM-MM simulations. Science 258, 631–635. ( 10.1126/science.1411573) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beierlein FR, Michel J, Essex JW. 2011. A simple QM/MM approach for capturing polarization effects in protein-ligand binding free energy calculations. J. Phys. Chem. B 115, 4911–4926. ( 10.1021/jp109054j) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heimdal J, Ryde U. 2012. Convergence of QM/MM free-energy perturbations based on molecular-mechanics or semiempirical simulations. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys 14, 12 592–12 604. ( 10.1039/c2cp41005b) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fox SJ, Pittock C, Tautermann CS, Fox T, Christ C, Malcolm NO, Essex JW, Skylaris CK. 2013. Free energies of binding from large-scale first-principles quantum mechanical calculations: application to ligand hydration energies. J. Phys. Chem. B 117, 9478–9485. ( 10.1021/jp404518r) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.König G, Pickard FC, Mei Y, Brooks BR. 2014. Predicting hydration free energies with a hybrid QM/MM approach: an evaluation of implicit and explicit solvation models in SAMPL4. J. Comput.-Aid. Mol. Design 28, 245–257. ( 10.1007/s10822-014-9708-4) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.König G, Hudson PS, Boresch S, Woodcock HL. 2014. Multiscale free energy simulations: an efficient method for connecting classical MD simulations to QM or QM/MM free energies using non-Boltzmann Bennett reweighting schemes. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 10, 1406–1419. ( 10.1021/ct401118k) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Genheden S, Martinez AIC, Criddle MP, Essex JW. 2014. Extensive all-atom Monte Carlo sampling and QM/MM corrections in the SAMPL4 hydration free energy challenge. J. Comput.-Aided Mol. Des. 28, 187–200. ( 10.1007/s10822-014-9717-3) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hudson PS, Woodcock HL, Boresch S. 2015. Use of nonequilibrium work methods to compute free energy differences between molecular mechanical and quantum mechanical representations of molecular systems. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 6, 4850–4856. ( 10.1021/acs.jpclett.5b02164) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sampson C, Fox T, Tautermann CS, Woods C, Skylaris CK. 2015. A ‘Stepping Stone’ approach for obtaining quantum free energies of hydration. J. Phys. Chem. B 119, 7030–7040. ( 10.1021/acs.jpcb.5b01625) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cave-Ayland C, Skylaris CK, Essex JW. 2015. Direct validation of the single step classical to quantum free energy perturbation. J. Phys. Chem. B 119, 1017–1025. ( 10.1021/jp506459v) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ryde U, Söderhjelm P. 2016. Ligand-binding affinity estimates supported by quantum-mechanical methods. Chem. Rev. 116, 5520–5566. ( 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00630) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hudson PS, Woodcock HL, Boresch S. 2019. On the use of interaction energies in QM/MM free energy simulations. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 15, 4632–4645. ( 10.1021/acs.jctc.9b00084) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.König G, Brooks BR, Thiel W, York DM. 2018. On the convergence of multi-scale free energy simulations. Mol. Simulat. 44, 1062–1081. ( 10.1080/08927022.2018.1475741) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pickard FC, König G, Simmonett AC, Shao Y, Brooks BR. 2016. An efficient protocol for obtaining accurate hydration free energies using quantum chemistry and reweighting from molecular dynamics simulations. Biorg. Med. Chem. 24, 4988–4997. ( 10.1016/j.bmc.2016.08.031) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pickard FC, König G, Tofoleanu F, Lee J, Simmonett AC, Shao Y, Ponder JW, Brooks BR. 2016. Blind prediction of distribution in the SAMPL5 challenge with QM based protomer and pKa corrections. J. Comput.-Aided Mol. Des. 30, 1087–1100. ( 10.1007/s10822-016-9955-7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.König G. et al. 2016. Calculating distribution coefficients based on multi-scale free energy simulations: an evaluation of MM and QM/MM explicit solvent simulations of water-cyclohexane transfer in the SAMPL5 challenge. J. Comput.-Aided Mol. Des. 30, 989–1006. ( 10.1007/s10822-016-9936-x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Warshel A, Russell ST. 1984. Calculations of electrostatic interactions in biological systems and in solutions. Q. Rev. Biophys. 17, 283–422. ( 10.1017/S0033583500005333) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Åqvist J, Medina C, Samuelsson JE. 1994. New method for predicting binding-affinity in computer-aided drug design. Prot. Eng. 7, 385–391. ( 10.1093/protein/7.3.385) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hummer G, Pratt LR, García AE. 1996. Free energy of ionic hydration. J. Phys. Chem. 100, 1206–1215. ( 10.1021/jp951011v) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heid E, Moser W, Schröder C. 2017. On the validity of linear response approximations regarding the solvation dynamics of polyatomic solutes. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 19, 10940–10950. ( 10.1039/C6CP08575J) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marcus R. 1993. Electron-transfer reactions in chemistry—theory and experiment (Nobel Lecture). Ang. Chem. Int. Ed. 32, 1111–1121. ( 10.1002/anie.199311113) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zwanzig RW. 1954. High-temperature equation of state by a perturbation method. I. Nonpolar gases. J. Chem. Phys. 22, 1420–1426. ( 10.1063/1.1740409) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zuckerman DM, Woolf TB. 2002. Theory of a systematic computational error in free energy differences. Phys. Rev. Lett. 89, 180602 ( 10.1103/PhysRevLett.89.180602) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shirts MR, Pande VS. 2005. Comparison of efficiency and bias of free energies computed by exponential averaging, the Bennett acceptance ratio, and thermodynamic integration. J. Chem. Phys. 122, 144107 ( 10.1063/1.1873592) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lu N, Kofke DA. 2001. Accuracy of free-energy perturbation calculations in molecular simulation. I. Modeling. J. Chem. Phys. 114, 7303–7311. ( 10.1063/1.1359181) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boresch S, Woodcock HL. 2017. Convergence of single-step free energy perturbation. Mol. Phys. 115, 1200–1213. ( 10.1080/00268976.2016.1269960) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Best RB, Zhu X, Shim J, Lopes PE, Mittal J, Feig M, MacKerell AD Jr. 2012. Optimization of the additive CHARMM all-atom protein force field targeting improved sampling of the backbone ϕ, ψ and side-chain χ1 and χ2 dihedral angles. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 8, 3257–3273. ( 10.1021/ct300400x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Becke A. 1988. Density-functional exchange-energy approximation with correct asymptotic behavior. Phys. Rev. A 38, 3098–3100. ( 10.1103/PhysRevA.38.3098) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee C, Yang W, Parr R. 1988. Development of the Colle-Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Phys. Rev. B 37, 785–789. ( 10.1103/PhysRevB.37.785) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hariharan PC, Pople JA. 1974. Accuracy of ah n equilibrium geometries by single determinant molecular orbital theory. Mol. Phys. 27, 209–214. ( 10.1080/00268977400100171) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhao Y, Truhlar DG. 2007. The M06 suite of density functionals for main group thermochemistry, thermochemical kinetics, noncovalent interactions, excited states, and transition elements: two new functionals and systematic testing of four M06-class functionals and 12 other function. Theor. Chem. Acc. 120, 215–241. ( 10.1007/s00214-007-0310-x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cornell WD. et al. 1995. A second generation force field for the simulation of proteins and nucleic acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 117, 5179–5197. ( 10.1021/ja00124a002) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Maier JA, Martinez C, Kasavajhala K, Wickstrom L, Hauser KE, Simmerling C. 2015. ff14SB: improving the accuracy of protein side chain and backbone parameters from ff99SB. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 11, 3696–3713. ( 10.1021/acs.jctc.5b00255) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.MacKerell AD. et al. 1998. All-atom empirical potential for molecular modeling and dynamics studies of proteins. J. Phys. Chem. B 102, 3586–3616. ( 10.1021/jp973084f) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schmid N, Eichenberger AP, Choutko A, Riniker S, Winger M, Mark AE, van Gunsteren WF. 2011. Definition and testing of the GROMOS force-field versions 54A7 and 54B7. Europ. Biophys. J. 40, 843–856. ( 10.1007/s00249-011-0700-9) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Horta BA, Lin Z, Huang W, Riniker S, Van Gunsteren WF, Hünenberger PH. 2012. Reoptimized interaction parameters for the peptide-backbone model compound N-methylacetamide in the GROMOS force field: influence on the folding properties of two beta-peptides in methanol. J. Comput. Chem. 33, 1907–1917. ( 10.1002/jcc.23021) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jorgensen WL, Maxwell DS, Tirado-Rives J. 1996. Development and testing of the OPLS all-atom force field on conformational energetics and properties of organic liquids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 118, 11225–11236. ( 10.1021/ja9621760) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kesharwani MK, Karton A, Martin JM. 2015. Benchmark ab initio conformational energies for the proteinogenic amino acids through explicitly correlated methods. Assessment of density functional methods. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 12, 444–454. ( 10.1021/acs.jctc.5b01066) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yuan Y, Mills MJ, Popelier PL, Jensen F. 2014. Comprehensive analysis of energy minima of the 20 natural amino acids. J. Phys. Chem. A 118, 7876–7891. ( 10.1021/jp503460m) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lopes PE, Huang J, Shim J, Luo Y, Li H, Roux B, MacKerell AD Jr. 2013. Polarizable force field for peptides and proteins based on the classical drude oscillator. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 9, 5430–5449. ( 10.1021/ct400781b) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lemkul JA, Huang J, Roux B, MacKerell AD Jr. 2016. An empirical polarizable force field based on the classical drude oscillator model: development history and recent applications. Chem. Rev. 116, 4983–5013. ( 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00505) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Huang J, Simmonett AC, Pickard FC IV, MacKerell AD Jr, Brooks BR. 2017. Mapping the drude polarizable force field onto a multipole and induced dipole model. J. Chem. Phys. 147, 161702 ( 10.1063/1.4984113) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.König G, Pickard FC, Huang J, Thiel W, MacKerell AD, Brooks BR, York DM. 2018. A Comparison of QM/MM simulations with and without the drude oscillator model based on hydration free energies of simple solutes. Molecules 23, 2695 ( 10.3390/molecules23102695) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Brooks BR. et al. 2009. CHARMM: the biomolecular simulation program. J. Comput. Chem. 30, 1545–1614. ( 10.1002/jcc.21287) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Brooks BR, Bruccoleri RE, Olafson BD, States DJ, Swaminathan SA, Karplus M. 1983. CHARMM: a program for macromolecular energy, minimization and dynamics calculations. J. Comput. Chem. 4, 187–217. ( 10.1002/jcc.540040211) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Woodcock HL III, Hodošček M, Gilbert AT, Gill PM, Schaefer HF III, Brooks BR. 2007. Interfacing Q-Chem and CHARMM to perform QM/MM reaction path calculations. J. Comp. Chem. 28, 1485–1502. ( 10.1002/jcc.20587) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Møller C, Plesset MS. 1934. Note on an approximation treatment for many-electron systems. Phys. Rev. 46, 618–622. ( 10.1103/PhysRev.46.618) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dunning TH., Jr 1989. Gaussian basis sets for use in correlated molecular calculations. I. The atoms boron through neon and hydrogen. J. Chem. Phys. 90, 1007–1023. ( 10.1063/1.456153) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.van Gunsteren WF, Billeter SR, Eising AA, Hünenberger PH, Krüger PK, Mark AE, Scott WR, Tironi IG. 1996. Biomolecular simulation: the GROMOS96 manual and user guide. Zürich, Switzerland: vdf Hochschulverlag.

- 65.Weber W, Thiel W. 2000. Orthogonalization corrections for semiempirical methods. Theor. Chem. Acc. 103, 495–506. ( 10.1007/s002149900083) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dral PO, Wu X, Spörkel L, Koslowski A, Weber W, Steiger R, Scholten M, Thiel W. 2016. Semiempirical quantum-chemical orthogonalization-corrected methods: theory, implementation, and parameters. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 12, 1082–1096. ( 10.1021/acs.jctc.5b01046) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ponder JW. et al. 2010. Current status of the AMOEBA polarizable force field. J. Phys. Chem. B 114, 2549–2564. ( 10.1021/jp910674d) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.König G, Boresch S. 2009. Hydration free energies of amino acids: why side chain analog data are not enough. J. Phys. Chem. B 113, 8967–8974. ( 10.1021/jp902638y) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.König G, Bruckner S, Boresch S. 2013. Absolute hydration free energies of blocked amino acids: implications for protein solvation and stability. Biophys. J. 104, 453–462. ( 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.12.008) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Roseman MA. 1988. Hydrophilicity of polar amino-acid side-chains is markedly reduced by flanking peptide bonds. J. Mol. Biol. 200, 513–522. ( 10.1016/0022-2836(88)90540-2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.König G, Mei Y, Pickard FC IV, Simmonett AC, Miller BT, Herbert JM, Woodcock HL, Brooks BR, Shao Y. 2016. Computation of hydration free energies using the multiple environment single system quantum mechanical/molecular mechanical method. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 12, 332–344. ( 10.1021/acs.jctc.5b00874) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Huang J. et al. 2017. An estimation of hybrid quantum mechanical molecular mechanical polarization energies for small molecules using polarizable force-field approaches. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 13, 679–695. ( 10.1021/acs.jctc.6b01125) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mark AE, van Gunsteren W. 1994. Decomposition of the free energy of a system in terms of specific interactions. implications for theoretical and experimental studies. J. Mol. Biol. 240, 167–176. ( 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1430) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Smith PE, van Gunsteren W. 1994. When are free energy components meaningful? J. Phys. Chem. 98, 13735–13740. ( 10.1021/j100102a046) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.König G, Brooks BR. 2015. Correcting for the free energy costs of bond or angle constraints in molecular dynamics simulations. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1850, 932–943. ( 10.1016/j.bbagen.2014.09.001) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Giese TJ, York DM. 2019. Development of a robust indirect approach for MM→ QM free energy calculations that combines force-matched reference potential and Bennett’s acceptance ratio methods. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 15, 5543–5562. ( 10.1021/acs.jctc.9b00401) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hudson PS, Boresch S, Rogers DM, Woodcock HL. 2018. Accelerating QM/MM free energy computations via intramolecular force matching. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 14, 6327–6335. ( 10.1021/acs.jctc.8b00517) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.König G, Miller BT, Boresch S, Wu X, Brooks BR. 2012. Enhanced sampling in free energy calculations: combining SGLD with the Bennett’s acceptance ratio and enveloping distribution sampling methods. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 8, 3650–3662. ( 10.1021/ct300116r) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Boresch S, Karplus M. 1996. The Jacobian factor in free energy simulations. J. Chem. Phys. 105, 5145–5154. ( 10.1063/1.472358) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Herschbach DR, Johnston HS, Rapp D. 1959. Molecular partition functions in terms of local properties. J. Chem. Phys. 31, 1652–1661. ( 10.1063/1.1730670) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bradshaw RT, Essex JW. 2016. Evaluating parametrization protocols for hydration free energy calculations with the amoeba polarizable force field. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 12, 3871–3883. ( 10.1021/acs.jctc.6b00276) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mohamed NA, Bradshaw RT, Essex JW. 2016. Evaluation of solvation free energies for small molecules with the amoeba polarizable force field. J. Comput. Chem. 37, 2749–2758. ( 10.1002/jcc.24500) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Albaugh A. et al. 2016. Advanced potential energy surfaces for molecular simulation. J. Phys. Chem. B 120, 9811–9832. ( 10.1021/acs.jpcb.6b06414) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.MacKerell A, Feig M, Brooks C. 2004. Extending the treatment of backbone energetics in protein force fields: limitations of gas-phase quantum mechanics in reproducing protein conformational distributions in molecular dynamics simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 25, 1400–1415. ( 10.1002/jcc.20065) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Grimme S. 2014. A general quantum mechanically derived force field (QMDFF) for molecules and condensed phase simulations. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 10, 4497–4514. ( 10.1021/ct500573f) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Vanduyfhuys L, Vandenbrande S, Verstraelen T, Schmid R, Waroquier M, Van Speybroeck V. 2015. QuickFF: a program for a quick and easy derivation of force fields for metal-organic frameworks from ab initio input. J. Comput. Chem. 36, 1015–1027. ( 10.1002/jcc.23877) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Vandenbrande S, Waroquier M, van Speybroeck V, Verstraelen T. 2016. The monomer electron density force field (MEDFF): a physically inspired model for noncovalent interactions. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 13, 161–179. ( 10.1021/acs.jctc.6b00969) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Prampolini G, Campetella M, De Mitri N, Livotto PR, Cacelli I. 2016. Systematic and automated development of quantum mechanically derived force fields: the challenging case of halogenated hydrocarbons. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 12, 5525–5540. ( 10.1021/acs.jctc.6b00705) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Brunken C, Reiher M. 2019. Self-parametrizing system-focused atomistic models. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 16, 1646–1665. ( 10.1021/acs.jctc.9b00855) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

This article has no additional data.