Abstract

Many complex natural and artificial systems are composed of large numbers of elementary building blocks, such as organisms made of many biological cells or processors made of many electronic transistors. This modular substrate is essential to the evolution of biological and technological complexity, but has been difficult to replicate for mechanical systems. This study seeks to answer if layered assembly can engender exponential gains in the speed and efficacy of block or cell-based manufacturing processes. A key challenge is how to deterministically assemble large numbers of small building blocks in a scalable manner. Here, we describe two new layered assembly principles that allow assembly faster than linear time, integrating n modules in O(n2/3) and O(n1/3) time: one process uses a novel opto-capillary effect to selectively deposit entire layers of building blocks at a time, and a second process jets building block rows in rapid succession. We demonstrate the fabrication of multi-component structures out of up to 20 000 millimetre scale spherical building blocks in 3 h. While these building blocks and structures are still simple, we suggest that scalable layered assembly approaches, combined with a growing repertoire of standardized passive and active building blocks could help bridge the meso-scale assembly gap, and open the door to the fabrication of increasingly complex, adaptive and recyclable systems.

Keywords: self-assembly, voxel printing, layered assembly, multi-material printing, digital fabrication, self-alignment

1. Introduction

Most man-made mechanical systems today are constructed of a large variety of parts and components with arbitrary geometric and functional interfaces. The arbitrary architecture of such integrations makes it difficult to systematically design, simulate and fabricate complex three-dimensional machines, as well as to repair, adapt and recycle existing machines. By contrast, electronic circuits have reached very large-scale integration (VLSI) levels through the consistent definition of elementary building blocks, interfaces and design rules. Biological systems also construct, repair, adapt and recycle large-scale and complex organisms by combining and recombining a relatively small repertoire of building block types—such as cells, proteins or amino acids.

Here we explore an analogous concept applied to physical systems, where machines would execute a large-scale integration of millions of small-scale building blocks. The building blocks would be self-aligning and interlocking, resulting in integrated and precise large-scale systems. Most building blocks can be passive and low cost, while others could be active sensors, actuators, computational and power components used more sparingly. A relatively small set of elementary building blocks will enable a large range of machines that can be fabricated, akin to how a small set of primary colours in a printer enables a combinatorial space of colour shades and complex pictures.

Previous work by Gershenfeld and colleagues [1,2] and Whitesides & Grzybowski [3] predicts that enabling large-scale integrations of components in arbitrary three-dimensional configurations would usher what is essentially a transition from analogue to digital in the manufacturing of physical matter. A major challenge to the realization of this vision, however, is the difficulty of precisely assembling massive numbers of small-scale building blocks into arbitrary configurations within a three-dimensional lattice.

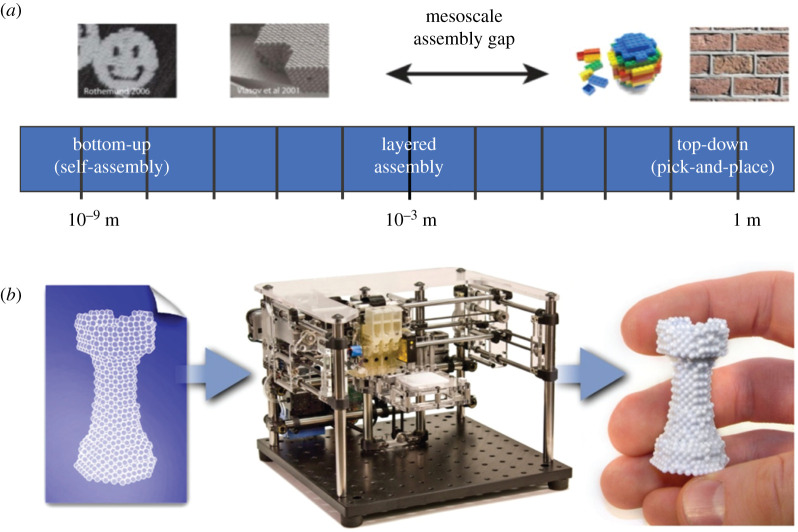

The challenge of assembling large numbers of components is especially difficult at the meso-scale where neither self-assembly nor top-down pick-and-place techniques are particularly effective (figure 1a). Recent manufacturing techniques such as bottom-up self-assembly [3,4] offer some of the benefits of modular assembly in their ability to spontaneously assemble structures guided by local interactions between components; however, self-assembly processes can be difficult to control and are generally limited to regular, semi-periodic or random structures [5–7]. Top-down deterministic pick-and-place approaches [8] offer precise control over production and are useful where a relatively small number of components are to be placed. However, they are limited in their throughput, and at small scales are often limited to two dimensions.

Figure 1.

Layered assembly. (a) A meso-scale assembly gap currently exists between deterministic top-down assembly methods and bottom-up self-assembly. (b) A layered assembler (centre) arranges raw building blocks into the desired object. Here, a rook shape composed of several thousand spherical elements is specified electronically (left) and assembled into a physical object (right).

Attempts have been made to reconcile different modes of assembly such as hierarchical [9–13], directed [14–16] and templated [17–19] self-assembly, but these approaches cannot yet uniquely address each element in a massive three-dimensional matrix or operate with meso-scale prefabricated components.

Recent additive-manufacturing technologies such as selective laser sintering [20] have enabled top-down fabrication of arbitrarily complex three-dimensional geometries, but those methods also cannot handle multi-material manufacturing or prefabricated building blocks [21]; as a result, they are limited to a relatively small set of passive homogeneous materials with mutually compatible rheological properties [22–26].

Here, we describe two processes that can address these needs. Both processes translate an electronic blueprint describing the three-dimensional configuration of building blocks, into a physical object. The first process is based on an opto-capillary effect that assembles an entire layer in parallel akin to the xerography process used in a laser printer. The second process conceptually resembles an inkjet printer and operates by rapidly depositing a row of building blocks through a nozzle.

After considering a wide variety of constituent element geometries [27], we chose to explore the layered assembly process using spherical elements, because they represent the optimal combination of manufacturability, precision and self-alignment. Specifically, for millimetre scale or smaller elements, spheres are easily mass manufactured, and available as existing commercial products like powders, pellets and ball bearings. As for precision and self-alignment, the geometry of spheres offer unique intra-layer self-alignment where spheres underneath a given layer act as alignment guides for the spheres in the subsequent layer, much like Lego bricks act as alignment guides for bricks placed above them. Finally, spheres are symmetric allow for efficient mass manipulation with tools like a vibration feeder (electronic supplementary material, section S1).

2. Parallel-layered assembly

The parallel method of layered assembly selectively assembles an entire layer of elements at once. The key challenge is how to selectively address individual voxels in a large two-dimensional array. We solve this challenge by exploiting light-sensitive capillary effects. Capillary effects are well suited to manipulate millimetre scale elements in parallel. We use optical energy to address region selectively, similar to the process used in xerography. However, instead of the light dissipating electrostatic forces on a photoconductive surface, here the light is intense enough to locally dry a water-based solution on the deposition head surface, and thus locally control its capillary adhesion force.

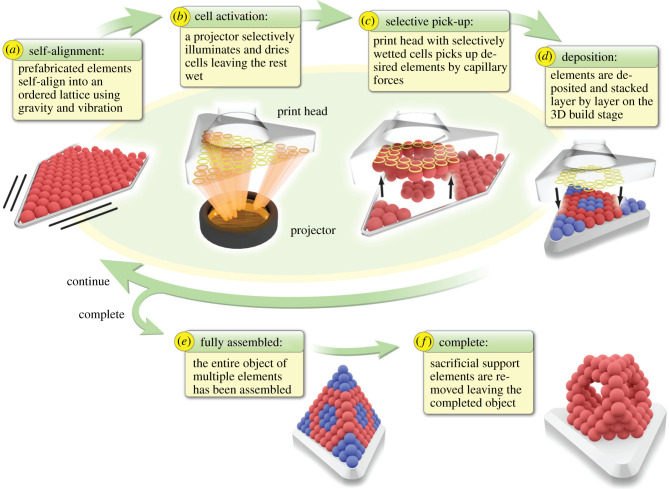

Figure 2 illustrates the steps in the layered assembly process. The desired object is first expressed in a blueprint made up of a series of binary bitmaps that correspond to successive layers of the physical building blocks to be assembled. Each bit in the bitmap signals the existence or absence of a specific physical element type in a specific layer in the target object. Prefabricated elements of the appropriate types are then dispensed into the material feeder trays. Elements of a single material self-align using gravity and vibration in the tray (figure 2a). The spheres are settled until they reach a perfect two-dimensional hexagonal arrangement. In these demonstrations, we used spherical 1.5 mm diameter elements in 55-unit triangular trays. We separately aligned two types of spheres of different materials (see electronic supplementary material, section S1). This fabrication process is scalable to larger layers, a wide array of materials, and elements as small as 100 mm, whose are dominated by stiction [28] and Van Der Waals forces [29].

Figure 2.

Parallel-layered assembly using spherical elements. (a) Prefabricated elements of multiple materials are poured into feeders and self-align into an ordered lattice. (b) A projector selectively activates the desire cells on the wetted deposition tool by drying unwanted cells. (c) The head is pressed against the lattice and all wetted regions pick up elements simultaneously and deposit them on the build stage (d). Steps A through D are repeated for each material of each layer. Once the entire object is assembled (e), sacrificial support material may be removed to create freeform geometry (f).

Once a uniform layer of a single material has been self-aligned, we used a parallel capillary opto-fluidic effect to selectively pick up elements specified by the electronic bitmap through a process of selective wetting. First, a flat print head containing a pattern of divots corresponding to lattice positions is uniformly wetted using a solution of water mixed with detergent (electronic supplementary material, section S1). This solution was chosen to enable favourable wetting characteristics. The bitmap of elements is then transformed into a black and white image of a pattern of dots that each coincide with a cell on the print head. Using appropriate optics, this image is then projected onto the infrared absorbing deposition head using a digital light projector with high infrared emitting mercury arc lamp (figure 2b). The desired pattern of cells is dried in approximately one minute, leaving the remainder of the cells wet and ready to pick up building blocks through capillary effects.

To pick up and deposit the desired elements, the selectively wetted print head presses down onto the aligned spheres. The water in the active divots wets around the perimeter of its respective sphere, holding it in place by surface tension. The deposition head then lifts and carries only these selected spheres to the build stage (figure 2c). A liquid polyvinyl acetate binder was used to temporarily bind the structure together during the build process. The layer of binder is spread on the existing printed object, and the current layer is deposited. Each sphere falls into the interstitial region of the three spheres below it and is held by the adhesive properties of the binder as the deposition head moves away (figure 2d). The process described above is repeated once for each material type for each layer. Since an entire layer can be placed simultaneously regardless of the number of elements in the layer, assembling an object with n elements can be accomplished in O(n1/3) time.

At several steps in this process, machine vision is used to monitor and verify important information regarding the build (see electronic supplementary material, section S1). During the self-alignment of elements in the feeders, any errors (such as a void within the lattice or a dislocation) are characterized and can be accounted for as necessary either by resetting the alignment process, or by repeating the layer deposition for error correction. During the selective drying process, the significant change in reflectance between wet and dry surfaces make optical feedback for this process straightforward. Additional machine vision steps directly before and after deposition verify which elements were actually deposited, and this information is used in a closed-loop deposition algorithm to account for errors.

3. Serial-layered assembly

The alternative serial method employs a continuously scanning deposition tool that deposits elements on demand, in the same way that an inkjet printer deposits droplets of ink. A cross-section of a deposition module is shown in figure 3a, while a sample part constructed from this process is shown in figures 1b and 3b. The elementary modules, in this case spheres, are poured in the top of the reservoir. An alignment paddle wheel runs continuously to replenish the one-dimensional buffer below as it is emptied. The spheres are gravity-fed through the buffer and deposited by a solenoid-actuated escapement mechanism. This mechanism is designed such that every actuation of the solenoid releases exactly one discrete sphere and advances the buffer by one.

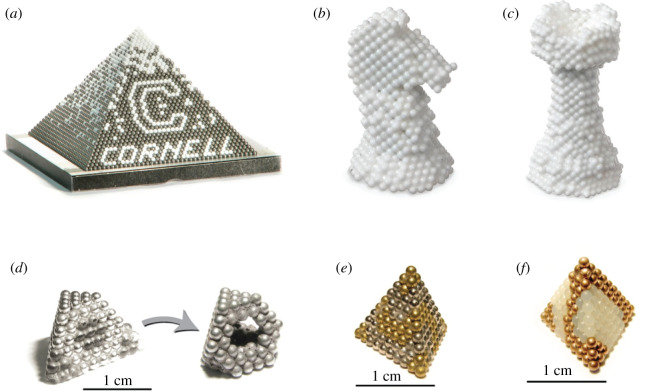

Figure 3.

Examples of objects built by layered assembly: 1.5 mm spherical elements of multiple materials are assembled into a stable three-dimensional lattice such as (a) a 22 000 element structure. Selectively bonding elements enables freeform shapes such as a knight (b) and rook (c). Other material and post-processing combinations result in a freeform stainless steel structure (d), a brass and stainless steel structure (e) and a copper–nylon structure which forms a simple electrical network (f).

An optical distance sensor is used in the serial process to monitor and verify the placement of each element. Missing elements are automatically corrected. For the implementation described here, one material deposition module was used per material in the finished object. However, the process scales in a manner similar to inkjet printers by incorporating multiple parallel jets per material. Ideally, a complete row of modules can be deposited simultaneously simply by duplicating the deposition heads, leading to a O(n2/3) scaling with respect to the number of elements placed. Additional technical details can be found in electronic supplementary material, section S2.

4. Results

Using the two three-dimensional-layered assemblers, we constructed a variety of structures using different combinations of metallic and non-metallic materials, including a simple electrical network constructed of copper and nylon elements. We created freeform geometries from sintered stainless steel, using acrylic spheres as a sacrificial material to support overhanging regions in steel elements (see electronic supplementary material, section S3). Alternatively, we used acetone vapours to sinter acrylic elements together, using steel elements as sacrificial support structures (see electronic supplementary material, section S3). We have demonstrated the automated fabrication of structures with greater than 20 000 elements in less than 3 h (figure 3).

The performance characteristics of the serial and parallel implementations are shown in table 1. As a comparison, we included a high-performance pick-and-place benchmark system that can place approximately three elements per second. The serial process was configured to deposit approximately eight elements per second when depositing in a continuous line. However, when accounting for re-positioning the deposition head and error correction, the average deposition rate is around 2.5 elements per second. The parallel system places one material of one layer of up to 55 elements in approximately 285 s. Therefore, it takes 90 min to complete a full two-material, 10-layered build. The length of time needed to complete a single layer is independent of the number of elements in a given layer but rather is limited by the time needed for the drying process.

Table 1.

Assembly rate scaling characteristics. As implemented, the serial assembly approach is much faster per element, but the parallel approach has a lower error rate and scales more favourably to objects with many more elements.

| fast pick-and-place (baseline) | serial implementation | parallel implementation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| minimum time/element | 0.3 s | 0.13 s | 5.16 s |

| average time/element | 0.3 s | 0.43 sa | 27.47 sa |

| error rate | n.a. | 1.57% | 0.91% |

| scalability (as function of number of elements n) | O(n) | O(n2/3) | O(n1/3) |

| expected time to assemble one billion building blocks in a 1000-sided cubeb | 10 years | 42 hc | 80 hd |

aIncludes error correction time.

bExcludes potential error correction time.

cAssumes identical deposition and feed rates as the demonstrated implementation with a deposition module per row.

dAssumes identical time per layer as the demonstrated implementation.

A fundamental characteristic that distinguishes layered assembly processes from traditional pick-and-place assemblers is their ability to scale favourably to large numbers of building blocks. At small numbers of modules, a fast pick-and-place method may be superior. But as the number of elements grows, both the serial and parallel methods become asymptotically preferable in time per element. The serial method can be adapted to deposit an entire line of material simultaneously. The parallel method naturally scales more favourably for high component counts because increasing the number of elements per layer does not increase the time per layer. The number of building blocks per layer can scale to large sizes and resolutions limited only by the current optical addressing technology, making the selective deposition of 1000 × 1000 building blocks in a single pass within reach. We note that all traditional pick-and-place, as well as the proposed layered assembly methods can be trivially accelerated by adding multiple printheads or assembly arms working in parallel or in a hierarchy.

In large structures, random dimensional errors of the individual elements tend to cancel out. Theoretical models also suggest that that the error in the dimensions of a printed object grows more slowly than in proportion to its size [27]. Specifically, stacking a pyramid of n layers of building blocks, each with a random diametrical standard deviation σv would result in a structure with a theoretical dimensional precision ɛ that grows as . The unintuitive implication is that a printed structure can be more precise that the assembler that assembled it. This sub-linear error scaling was verified both with numerical simulation and experiment (see electronic supplementary material, section S4).

5. Conclusion

The objects and basic building blocks presented in this work are a basis of both complex geometries and multi-material structures that can be fabricated with layered assembly. The principles underlying this process could have profound implications for the way that complex machines are designed, fabricated and recycled. For example, by printing layers of elements that consist of different materials into a single structure, layered assembly techniques could enable the production of tunable material properties [30], as well as combining mutually incompatible materials (such as metals and polymers, figure 3d) in a single build. Biological materials shaped into spheroids could permit fabrication of heterogeneous tissue on demand for tissue engineering applications [31].The path forward for this technology is the continued development and refinement of solid-state-actuated and software-controlled parallel positioning devices which can position both passive and active materials. Solid-state-actuation is particularly important for grasping millimetre scale (or smaller) objects in densely packed configurations, since it obviates the need for closely packed motors typically used in impactive robotic grippers. Finally, software control enables high processing speed and capability of handling a large number of elements.

The flexibility of using prefabricated discrete elements as fabrication building blocks enables layered assembly to go beyond the creation of just passive materials. For example, conductive and non-conductive elements permit the fabrication of three-dimensional electric circuits (e.g. figure 3f). Microprocessors, sensors and actuators embedded in ‘smart elements,' will allow fabrication of three-dimensional integrated active devices such as robots. Moreover, systems composed of elementary building blocks could be dismantled and the building blocks reused for new objects, providing a deeper level of recyclability not unlike biology.

Even a relatively small repertoire of carefully chosen element types covering a finite range of structural and functional properties will span a virtually endless space of potential blueprints. New simulation and design tools will be necessary to model, predict and explore this space. The ability of layered assembly techniques to fabricate complex designs on demand in a single desktop process may help provide more opportunities for designers to create and share their ideas, and help remove many of the fabrication barriers that currently prevent many ideas from being realized.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Data accessibility

Any new data presented in this paper is included in the article and supplementary information.

Competing interests

We declare we have no competing interests.

Funding

This work was supported by DARPA Grant No. W911NF-11-1-0093 and NSF Grant No. 0757478.

References

- 1.Gershenfeld N. 2008. Fab: the coming revolution on your desktop–from personal computers to personal fabrication, p. 288 New York, NY: Basic Books. (doi:13-978-0-465-02745-3) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Langford W, Ghassaei A, Gershenfeld N. 2016. Automated assembly of electronic digital materials. In International Manufacturing Science and Engineering Conference, vol. 2, p. V002T01A013 New York, NY: ASME ( 10.1115/MSEC2016-8627) [DOI]

- 3.Whitesides GM, Grzybowski B. 2002. Self-assembly at all scales. Science 295, 2418–2421. ( 10.1126/science.1070821) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Winfree E, Liu F, Wenzler LA, Seeman NC. 1998. Design and self-assembly of two-dimensional DNA crystals. Nature 394, 539–544. ( 10.1038/28998) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Breen TL, Tien J, Oliver SRJ, Hadzic T, Whitesides GM. 1999. Design and self-assembly of open, regular, 3D mesostructures. Science 284, 948–951. ( 10.1126/science.284.5416.948) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vlasov YA, Bo XZ, Sturm JC, Norris DJ. 2001. On-chip natural assembly of silicon photonic bandgap crystals. Nature 414, 289–293. ( 10.1038/35104529) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chworos A, Severcan I, Koyfman AY, Weinkam P, Oroudjev E, Hansma HG, Jaeger L. 2004. Building programmable jigsaw puzzles with RNA. Science 306, 2068–2072. ( 10.1126/science.1104686) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eigler DM, Schweizer EK. 1990. Positioning single atoms with a scanning tunnelling microscope. Nature 344, 524–526. ( 10.1038/344524a0) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.He Y, Ye T, Su M, Zhang C, Ribbe AE, Jiang W, Mao C. 2008. Hierarchical self-assembly of DNA into symmetric supramolecular polyhedra. Nature 452, 198–201. ( 10.1038/nature06597) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ikkala O, Ten Brinke G. 2002. Functional materials based on self-assembly of polymeric supramolecules. Science 295, 2407–2409. ( 10.1126/science.1067794) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu H, Thalladi VR, Whitesides S, Whitesides GM. 2002. Using hierarchical self-assembly to form three-dimensional lattices of spheres. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124, 14 495–14 502. ( 10.1021/ja0210446) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lopes WA, Jaeger HM. 2001. Hierarchical self-assembly of metal nanostructures on diblock copolymer scaffolds. Nature 414, 735–738. ( 10.1038/414735a) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Böker A, et al. 2004. Hierarchical nanoparticle assemblies formed by decorating breath figures. Nat. Mater. 3, 302–306. ( 10.1038/nmat1110) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin Y, et al. 2005. Self-directed self-assembly of nanoparticle/copolymer mixtures. Nature 434, 55–59. ( 10.1038/nature03310) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang Y, Duan X, Wei Q, Lieber CM. 2001. Directed assembly of one-dimensional nanostructures into functional networks. Science 291, 630–633. ( 10.1126/science.291.5504.630) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bowden N, Terfort A, Carbeck J, Whitesides GM. 1997. Assembly of mesoscale objects into ordered two-dimensional arrays. Science 276, 233–235. ( 10.1126/science.276.5310.233) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang D, Möhwald H. 2004. Template-directed colloidal self-assembly -the route to ‘ top-down’ nanochemical engineering. J. Mater. Chem. 14, 459–468. ( 10.1039/b311283g) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheng JY, Mayes AM, Ross CA. 2004. Nanostructure engineering by templated self-assembly of block copolymers. Nat. Mater. 3, 823–828. ( 10.1038/nmat1211) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hynninen AP, Thijssen JHJ, Vermolen ECM, Dijkstra M, Van Blaaderen A. 2007. Self-assembly route for photonic crystals with a bandgap in the visible region. Nat. Mater. 6, 202–205. ( 10.1038/nmat1841) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.ASTM. 2012. F2792-12a. Standard Terminology for Additive Manufacturing Technologies ( 10.1520/F2792-12A) [DOI]

- 21.Mici J, Ko JW, West J, Jaquith J, Lipson H. 2019. Parallel electrostatic grippers for layered assembly. Addit. Manuf. 27, 451–460. ( 10.1016/j.addma.2019.03.032) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Calvert P. 2001. Inkjet printing for materials and devices. Chem. Mater. 13, 3299–3305. ( 10.1021/cm0101632) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sun C, Fang N, Wu DM, Zhang X. 2005. Projection micro-stereolithography using digital micro-mirror dynamic mask. Sens. Actuator. A Phys. 121, 113–120. ( 10.1016/j.sna.2004.12.011) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stute F, Mici J, Chamberlain L, Lipson H. 2018. Digital wood: 3D internal color texture mapping. 3D print. Addit. Manuf. 4, 285–290. ( 10.1089/3dp.2018.0078) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Skylar-Scott MA, Mueller J, Visser CW, Lewis JA. 2019. Voxelated soft matter via multimaterial multinozzle 3D printing. Nature 575, 330–335. ( 10.1038/s41586-019-1736-8) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Russo A, Ahn BY, Adams JJ, Duoss EB, Bernhard JT, Lewis JA. 2011. Pen-on-paper flexible electronics. Adv. Mater. 23, 3426–3430. ( 10.1002/adma.201101328) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hiller J, Lipson H. 2009. Design and analysis of digital materials for physical 3D voxel printing. Rapid Prototyp. J. 15, 137–149. ( 10.1108/13552540910943441) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fearing RS. 1995. Survey of sticking effects for micro parts handling In IEEE Int. Conf. Intell. Robot. Syst., pp. 212–217. Piscataway, NJ: IEEE. ( 10.1109/iros.1995.526162) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li Q, Rudolph V, Peukert W. 2006. London-van der Waals adhesiveness of rough particles. Powder Technol. 161, 248–255. ( 10.1016/J.POWTEC.2005.10.012) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hiller J, Lipson H. 2010. Tunable digital material properties for 3D voxel printers. Rapid Prototyp. J. 16, 241–247. ( 10.1108/13552541011049252) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Du Y, Lo E, Ali S, Khademhosseini A. 2008. Directed assembly of cell-laden microgels for fabrication of 3D tissue constructs. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 9522–9527. ( 10.1073/pnas.0801866105) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Any new data presented in this paper is included in the article and supplementary information.