Introduction

Immunocompromised patients remain at an increased risk for cardiac implantable electronic device (CIED) infection,1 typically with Staphylococcus spp. as the most common culprit.2 Herein, we describe the case of an immunocompromised elderly patient who presented with unprovoked pericardial bleeding and cardiac tamponade as a consequence of spontaneous erosion and perforation of the right ventricle due to an acutely infected but otherwise chronically stable defibrillator lead in the setting of tricuspid valvular infective endocarditis secondary to Staphylococcus epidermidis.

Key Teaching Points.

-

•

Late, spontaneous myocardial erosion/perforation due to an acutely infected but otherwise chronically stable cardiac implantable electronic device lead remains exceedingly rare.

-

•

Such an outcome may occur in patients with infective endocarditis exposed to long-standing immunosuppression therapy coupled with predisposing risk factors (eg, advanced age and chronic kidney disease).

-

•

In some patients, the manifestation of late lead-related myocardial perforation may not be clinically evident, whereas in others, the resulting cardiac perforation may pose a life-threatening outcome.

Case report

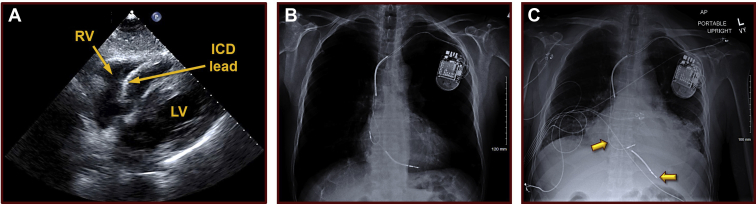

A 76-year-old man with past medical history significant for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation and sick sinus syndrome, on long-term oral anticoagulation therapy, in the setting of ischemic cardiomyopathy with a remote anterior wall myocardial infarction and an estimated left ventricular ejection fraction of 30%–35%, stage IV chronic kidney disease, ankylosing spondylitis, and Crohn disease on immunosuppression therapy, presented to the Emergency Department of our hospital with new-onset chest pain, shortness of breath, and worsening weakness. He was on chronic immunosuppression therapy for a 30-year history of ankylosing spondylitis and Crohn disease, treated with prednisone 5 mg daily and mesalamine 2000 mg 3 times a day. Furthermore, 7 years earlier, he had received an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) after surviving an out-of-hospital ventricular fibrillation cardiac arrest. He had not had any recent cardiovascular procedures or interventions during the course of the past 3½ years other than a routine 2-D echocardiogram 4 weeks earlier, which had confirmed a severely impaired but stable left ventricular systolic function and a normal right ventricle and pericardium (Figure 1A). Upon presentation to the Emergency Department, he was suspected with community-acquired pneumonia. But when compared to a prior radiograph from 1½ years earlier (Figure 1B), his new chest radiograph demonstrated an enlarged cardiac silhouette with likely dislodgements of his chronically stable atrial and defibrillator leads (Figure 1C). The atrial lead seemed to have rotated in position, with the tip no longer in the right atrial appendage where it was originally implanted, and the defibrillator lead exhibited an unusually vertical orientation suggestive of possible protrusion inferiorly beyond the cardiac border. An ICD interrogation indeed confirmed new abnormal findings, including a markedly reduced P wave and a diminished R wave amplitude with no evidence of pacing capture at maximum output (7.5 V at 1.5 ms) in either lead. Conversely, routine, serial ICD interrogations during the preceding 7 years had all been stable and within the normal limits, with the most recent one just 4 weeks earlier demonstrating stable P and R waves measuring 1.1 mV and 11.8 mV, with impedances of 420 ohms and 460 ohms and pacing thresholds of 1.0 V at 0.5 ms (both leads), respectively. There was no evidence of twiddler’s syndrome, nor was there a recent history of trauma or manipulation of the ICD electrodes.

Figure 1.

Baseline echocardiographic and radiographic findings. A: A baseline 2-D echocardiographic image from 4 weeks prior to hospital presentation, depicting a stable defibrillator lead, a normal right ventricle, and a normal pericardium without any pericardial effusion. B: A baseline chest radiograph (anterior-posterior projection), obtained 1½ years prior to presentation to the hospital, demonstrating normal heart and lungs and stable atrial and ventricular implantable cardioverter-defibrillator leads. The atrial lead was implanted in the right atrial appendage and the defibrillator lead in the inferior apex of the right ventricle. C: A chest radiograph (anterior-posterior projection) obtained at the time of presentation to the hospital, illustrating an enlarged cardiac silhouette with likely dislodgements of the previously chronically stable atrial and defibrillator leads. The radiograph shows that the atrial lead has now rotated in position, with the tip no longer visible in the right atrial appendage, where it was originally implanted. Additionally, the defibrillator lead also exhibits an unusually vertical orientation suggesting possible protrusion beyond the cardiac border, inferiorly. ICD = implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; LV = left ventricle; RV = right ventricle.

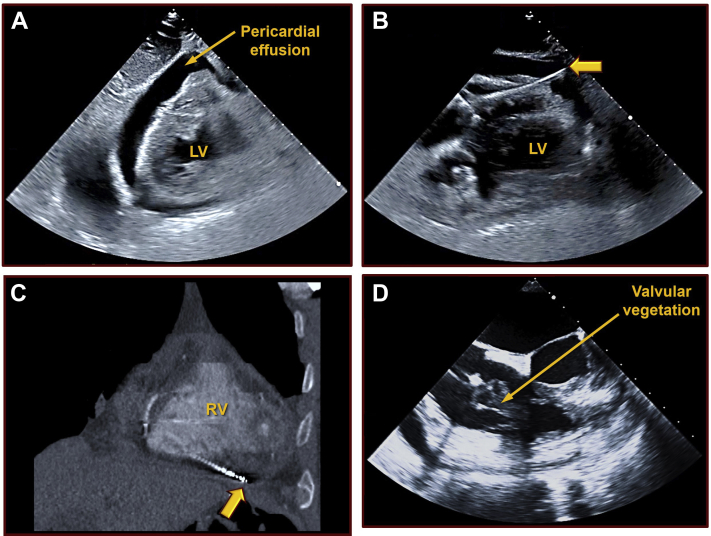

Meanwhile, a repeat 2-D echocardiogram obtained at the time of presentation showed a new, large circumferential pericardial effusion with tamponade physiology (Figure 2A). Furthermore, the echocardiogram demonstrated the defibrillator lead extending beyond the right ventricular wall and into the pericardium (Figure 2B). The Supplemental Video further illustrates this unusual finding. The same was also confirmed on a subsequent computerized tomography scan (Figure 2C). The patient was found to be bacteremic, with 2 sets of blood cultures positive for Staphylococcus epidermidis. Yet, his white blood count remained normal (8200/microliter), but with evidence of anemia with a hematocrit of 27.9%. His estimated glomerular filtration rate was also reduced at 18 mL/min. He underwent urgent pericardiocentesis with the removal of 735 mL of dark-colored blood from the pericardium and subsequent percutaneous extraction of his ICD system, including the dislodged leads. The extraction of the leads was performed in a hybrid operating room with cardiac surgical back-up support and the pericardial drain in situ. However, it proved to be quite simple and was performed without the need for any specialized tools, as little resistance was encountered while retracting and removing the leads. Cultures from the pericardial fluid were also found to be positive for Staphylococcus epidermidis. Moreover, a large tricuspid valvular vegetation was discovered, which persisted even after the removal of the ICD hardware (Figure 2D; Supplemental Video).

Figure 2.

Right ventricular perforation. A: A repeat 2-D echocardiographic image at the time of presentation to the hospital showing a new, large circumferential pericardial effusion with cardiac tamponade physiology. B: An echocardiographic image demonstrating the defibrillator lead extending beyond the right ventricular wall, into the pericardium. C: The same abnormal finding is illustrated on a computerized tomography scan. D: A large tricuspid valve vegetation observed persisting after the removal of the implantable cardioverter-defibrillator hardware. LV = left ventricle; RV = right ventricle.

The patient was treated successfully with a 2-week course of intravenous ceftriaxone. In addition, given his history of resuscitated out-of-hospital ventricular fibrillation arrest, he was discharged with a wearable cardioverter-defibrillator. His prednisone dose was tapered to 3 mg daily thereafter, and he has made full recovery. Three months following hospital discharge, he received another ICD system. While considerations were given to implantation of a subcutaneous device, in view of his marked resting sinus bradycardia and chronotropic incompetence, he ultimately received another dual-chamber transvenous system with atrial pacing capability. Meanwhile, he has not had any recurrent infections, sequelae, or related complications during long-term follow-up.

Discussion

Although late ventricular perforation by CIED leads have been previously reported,3, 4, 5, 6, 7 simultaneous dislodgement of infected but chronically stable atrial and ventricular leads is rather uncommon. But even more unusual and exceedingly rare is the observation of spontaneous lead–related ventricular erosion by an acutely infected but otherwise chronically stable defibrillator lead, as illustrated in the current case report.

In general, the incidence of adverse events associated with contemporary, pectoral ICD implants remains low.8 The incidence of device-related infection necessitating CIED system removal as well as lead complications are both estimated at ∼2%.9 The latter primarily consists of early lead dislodgement.8 Although the overall frequency of ICD lead dislodgement and related cardiac perforation is estimated between 0.6% and 5.2%,10 late lead dislodgement (defined as >1 month following implant) remains extremely rare.4,5 Moreover, the manifestations of late lead-related myocardial perforation may sometimes not even be clinically evident.6,7 But in rare instances, as the one presented in the current manuscript, the resulting cardiac perforation might pose a life-threatening outcome.5,7

To date, more than 60 studies have examined a variety of risk factors associated with CIED-related infection.11 These studies have implicated several host-specific factors, such as corticosteroid use and chronic kidney disease, as well as device-related variables (eg, CIED type, such as ICD or cardiac resynchronization therapy devices).11 Among the various risk factors, a number of observational studies have repeatedly shown an increased risk of systemic infections associated with corticosteroid therapy, even at low/moderate dosing intensity.12 In general, most of these studies have divided daily prednisone dosages into “low,” “moderate,” or “high” categories. Although somewhat arbitrary, most studies consider “low”-dose therapy as less than 5 mg daily. The duration of therapy itself is also thought to be an important factor, but is perhaps less well-defined in terms of the associated infectious risk.12 The exact dosing and duration that substantially change the risk–benefit ratio for corticosteroids likely vary by the individual, his/her underlying immune system, and the presence or absence of coexisting risk factors.

A recent multicenter study1 evaluating the independent predictors of acute CIED infection prompting patient hospitalization examined the outcomes of 19,603 patients who underwent a CIED implant. The authors identified advanced age, a depressed renal function, and immune compromise as independent and significant predictors of CIED infection. In this study, among the host-related risk factors, a compromised immune system yielded the highest odds ratio, of 2.28, for CIED infection.1 In another study, long-term corticosteroid use and chronic kidney disease yielded odds ratios of 3.44 and 3.02, respectively, for CIED infection.11 Granted that these prediction models were created in the setting of acute CIED infection, it is still noteworthy that the patient in the current case exhibited all 3 risk factors. In fact, rare, unprovoked, nosocomial CIED-related13 and non-CIED14 hardware infections have been well described in immunocompromised patients receiving long-term corticosteroid therapy. Furthermore, such individuals can frequently present with serious systemic infections, and even sepsis, with only subtle or mild symptoms nonsuggestive of a catastrophic infection, as was encountered in the current case.15 The authors believe that the long-standing history of corticosteroid therapy, coupled with concomitant immunosuppression with mesalamine and other existing risk factors in this patient, such as advanced age and chronic kidney disease, collectively prompted the unusual complication of dual lead dislodgement with silent ventricular erosion and perforation observed in the current case. As such, this report serves as an important reminder for clinicians to assume a high level of clinical vigilance toward rare and unusual infection-related complications and manifestations when approaching immunocompromised patients, particularly those receiving corticosteroid therapy with complex risk factors.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we report an unusual case of acute erosion and perforation of the right ventricle due to an infected but otherwise chronically stable defibrillator lead, resulting in pericardial bleeding and cardiac tamponade. Although exceedingly rare, such a complication may occur spontaneously in immunocompromised patients, resulting in life-threatening outcomes. Clinical recovery and survival are determined by early diagnosis and timely intervention.

Footnotes

Funding Sources: The authors have no funding sources to disclose. Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrcr.2020.09.001.

Appendix. Supplementary data

Spontaneous right ventricular erosion and perforation by an acutely infected but otherwise chronically stable defibrillator lead. Shown are 2-D echocardiographic video clips recorded before and after pericardiocentesis, showing a chronically stable, infected defibrillator lead acutely eroded through the right ventricle into the pericardium with associated pericardial effusion and cardiac tamponade as well as a tricuspid valve vegetation that continued to persist following the removal of the hardware and the leads.

References

- 1.Birnie D.H., Wang J., Alings M. Risk factors for infections involving cardiac implanted electronic devices. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74:2845–2854. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.09.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atkinson J.B., Robinowitz M., McAllister H.A., Jr., Forman M.B., Virmani R. Cardiac infections in the immunocompromised host. Cardiol Clin. 1984;2:671–686. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jessel P.M., Yadava M., Nazer B. Transvenous management of cardiac implantable electronic device late lead perforation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2020;31:521–528. doi: 10.1111/jce.14331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amara W., Cymbalista M., Sergent J. Delayed right ventricular perforation with a pacemaker lead into subcutaneous tissues. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2010;103:53–54. doi: 10.1016/j.acvd.2008.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schroeter T., Doll N., Borger M.A., Groesdonk H.V., Merk D.R., Mohr F.W. Late perforation of a right ventricular pacing lead: A potentially dangerous complication. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;57:176–177. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1038705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aykan H.H., Akın A., Ertuğrul İ., Karagöz T. Delayed right-ventricular perforation by pacemaker lead; a rare complication in a 12-year-old girl. Turk Kardiyol Dern Ars. 2015;43:185–187. doi: 10.5543/tkda.2015.98372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fagundes A.A., Magalhães L.P., Pinheiro J., Flausino L., Souza L.R. Delayed right ventricular perforation in patient with implantable cardioverter – defibrillator. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2010;95:e148–e150. doi: 10.1590/s0066-782x2010001600021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shahian D.M., Williamson W.A., Martin D., Venditti F.J., Jr. Infection of implantable cardioverter defibrillator systems: A preventable complication? Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1993;16:1956–1960. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.1993.tb00988.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gold M.R., Peters R.W., Johnson J.W., Shorofsky S.R. Complications associated with pectoral implantation of cardioverter defibrillators. World–Wide Jewel Investigators. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1997;20:208–211. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.1997.tb04844.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carlson M.D., Freedman R.A., Levine P.A. Lead perforation: Incidence in registries. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2008;31:13–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2007.00943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Polyzos K.A., Konstantelias A.A., Falagas M.E. Risk factors for cardiac implantable electronic device infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Europace. 2015;17:767–777. doi: 10.1093/europace/euv053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Youssef J., Novosad S.A., Winthrop K.L. Infection risk and safety of corticosteroid use. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2016;42:157–176. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2015.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adjodah C., D'Ivernois C., Leyssene D., Berneau J.B., Hemery Y. A cardiac implantable device infection by Raoultella planticola in an immunocompromized patient. JMM Case Rep. 2017;4 doi: 10.1099/jmmcr.0.005080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laurent F., Rodriguez-Villalobos H., Cornu O., Vandercam B., Yombi J.C. Nocardia prosthetic knee infection successfully treated by one-stage exchange: Case report and review. Acta Clin Belg. 2015;70:287–290. doi: 10.1179/2295333714Y.0000000109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fishman J.A. Infection in organ transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2017;17:856–879. doi: 10.1111/ajt.14208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Spontaneous right ventricular erosion and perforation by an acutely infected but otherwise chronically stable defibrillator lead. Shown are 2-D echocardiographic video clips recorded before and after pericardiocentesis, showing a chronically stable, infected defibrillator lead acutely eroded through the right ventricle into the pericardium with associated pericardial effusion and cardiac tamponade as well as a tricuspid valve vegetation that continued to persist following the removal of the hardware and the leads.