Abstract

This cohort study examines how early spending changes vary by incidence of coronavirus disease 2019 and how implementation of policies to limit transmission affect health care spending as the pandemic evolves.

The effect of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic on health care spending in the US has important implications for payers, clinicians, hospitals, health care systems, and patients, and has been the subject of much debate. Understanding how early spending changes varied by disease incidence and implementation of policies to limit transmission can inform expectations about health care spending as the pandemic evolves.

Methods

For the first 14 weeks of 2020, we analyzed multipayer deidentified claims from FAIR Health spanning roughly 75% of the commercially insured and 50% of the Medicare Advantage population. Our analysis included fee-for-service (not capitated) claims submitted to FAIR Health by June 25, 2020, and used 2019 data to correct for unreported claims (eAppendix in the Supplement). The study was determined not to be human subjects research and thus not reviewed by the Harvard Medical School Committee on Human Studies.

We calculated weekly aggregate medical spending in total and categorized by type of care and 4 prespecified groups of states defined by cumulative incidence of confirmed cases by April 7 (COVID-19 activity) and timing of social distancing policies1 (1) New York; (2) high activity (excluding New York); (3) low activity, early social distancing; and (4) low activity, late social distancing (eAppendix in the Supplement). We also examined spending for typically elective procedures and COVID-19 inpatient spending (where identifiable by an emergently introduced diagnosis code).2

We focused on changes in spending from week 9 (ending March 3, 2020) to week 14 (ending April 7, 2020). We quantified the extremeness of these changes using a randomization inference approach (eAppendix in the Supplement).

Results

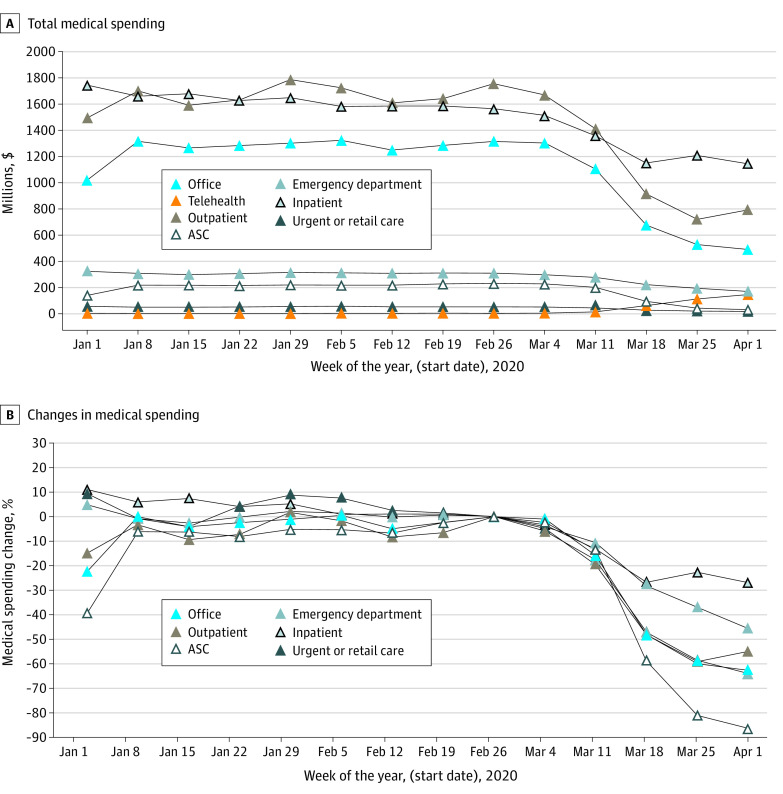

From week 9 to 14, aggregate medical spending decreased by $2.7 billion per week, or 46.0% (Figure 1). Spending decreased across all categories of services except telehealth, ranging from −26.9% for inpatient to −86.2% for ambulatory surgical center care (Figure 2).

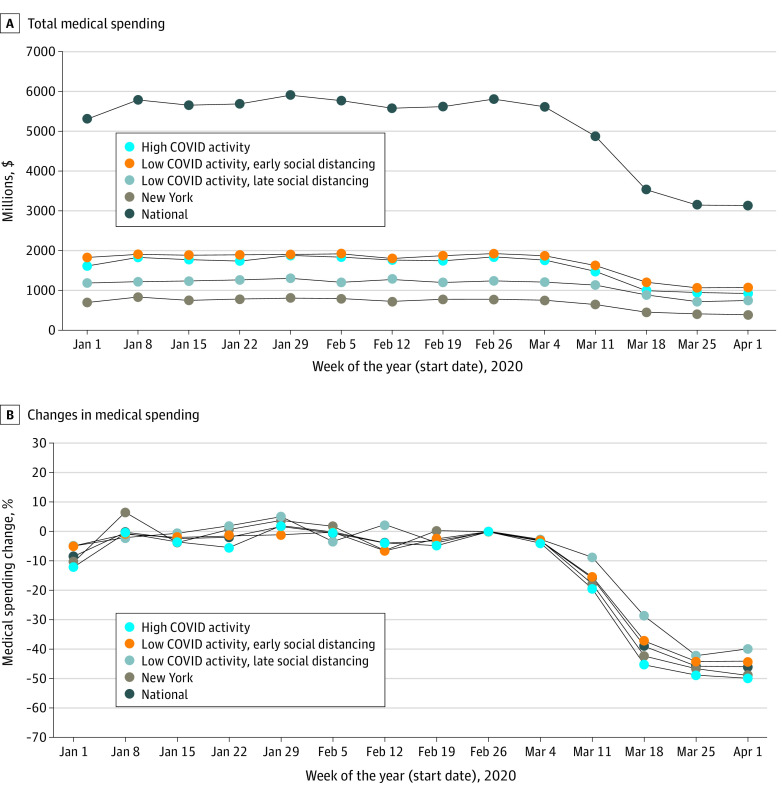

Figure 1. Weekly Total Medical Spending and Spending Changes Through the First Week of April 2020 by COVID-19 Activity, Timing of Social Distancing Policies, and Location.

A, Total medical spending in dollars and (B) relative to week 9. High-activity refers to high cumulative incidence of confirmed COVID-19 cases by April 7, 2020. Early vs late social distancing refers to state order to stay at home, shelter in place, or close nonessential businesses before vs after April 1, 2020. Lower spending during the week of January 1, 2020, is consistent with overlap with a national holiday (utilization was consistently lower in 2019 during holiday weeks). COVID-19 indicates coronavirus disease 2019.

Figure 2. Weekly Aggregate Medical Spending Through the First Week of April 2020, by Type of Care.

A, Aggregate medical spending in dollars and (B) spending relative to week 9. Weekly aggregate spending is displayed by type of care: acute inpatient, emergency department, ambulatory surgery center (ASC), outpatient care in hospital-owned facilities, outpatient care in office setting, telehealth, urgent care centers, and retail clinics. Post-acute spending is not displayed because it constituted a small proportion of spending for the predominantly non-elderly, commercially insured population. Enrollees aged 65 years or older accounted for approximately 16% of spending, as expected from the smaller share of the total Medicare population covered by FAIR Health data relative to the share of the commercially insured. The week of January 1, 2020, was lower for some spending categories owing to overlap with the holiday period. Telemedicine is not shown in panel B because the level of growth from week 9 exceeded 1000%.

Spending reductions were greater in New York (−48.8%) and other high-activity states (−49.9%) than low-activity states, where the reduction was greater in those implementing social distancing policies earlier (−44.2%) rather than later (−39.7%). Identifiable inpatient spending for COVID-19 increased more in high-activity than low-activity states (reaching 25.2% vs 3.5% of week 9 total inpatient spending by week 14), but total inpatient spending fell similarly in high-activity (−25.1%) and low-activity (−26.9%) states. In contrast, spending on elective procedures declined more in high-activity (−85.5%) than low-activity (−76.1%) states. Within each state category, spending reductions for elderly and nonelderly enrollees were largely similar.

All reductions were more extreme than all values produced by permutations of week pairs in 2019; differential percentage reductions in total spending associated with COVID-19 activity and social distancing were more negative than 99.7% and 95.5% of estimates produced by these permutations, respectively.

Discussion

The early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic was associated with a massive decrease in medical spending for the privately insured. Areas with higher COVID-19 activity had larger spending reductions, as increases in COVID-19 spending were more than offset by decreases in spending on non–COVID-19 care. Spending reductions in high-activity states were similarly substantial for seniors, who are at greater risk of hospitalization for COVID-19. Findings for low-activity states suggest a relationship between elevated concern for viral transmission (manifest as earlier distancing policies) and lower use of medical care. As cases surge in new areas and concerns about transmission prompt states to reimpose restrictions, these findings suggest that health care spending will likely rise and fall inversely with the severity of the pandemic and remain below prepandemic levels for its duration. Resurgent or persistent concerns may limit spending via demand-side or supply-side mechanisms, including patient fear of exposure and effects of infection control measures on faciliy capacity and nonessential care.3

The findings of this study do not reflect intensified COVID-19 testing or pent-up demand from deferred care. As incidence fell after our study period, outpatient utilization rebounded but remained below prepandemic levels through mid-June 2020,4 even for older adults for whom pent-up demand should be greater. Our findings suggest that subsequent COVID-19 surges that started in late June should be associated with corresponding spending reductions.

For commercial insurers, the prospect of net gains in 2020 raises questions about optimal use of unspent premium dollars5; rebates mandated by medical loss ratio regulations are partial and delayed by design. For Medicare Advantage plans, our findings suggest potentially substantial cumulative savings. Medicare could remand these savings to preserve the Trust Fund as tax revenue falls.6

eAppendix

References

- 1.Raifman J, Nocka K. COVID-19 US State Policy Database. Boston University School of Public Health. Updated July 2, 2020. Accessed July 9, 2020. https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1zu9qEWI8PsOI_i8nI_S29HDGHlIp2lfVMsGxpQ5tvAQ/edit#gid=2102005060

- 2.New ICD-10-CM code for the 2019 Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated April 1, 2020. Accessed July 9, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/icd/Announcement-New-ICD-code-for-coronavirus-3-18-2020.pdf

- 3.Healthcare Facilities: Managing Operations During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated June 28, 2020. Accessed July 9, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/guidance-hcf.html

- 4.Mehrotra A, Chernew ME, Linetsky D, Hatch H, Cutler D The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Outpatient Visits: Practices Are Adapting to the New Normal. The Commonwealth Fund. Updated June 25, 2020. Accessed July 9, 2020. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/2020/jun/impact-covid-19-pandemic-outpatient-visits-practices-adapting-new-normal

- 5.Dafny LS, McWilliams JM Primary Care Is Hurting: Why Aren’t Private Insurers Pitching In? Health Affairs Blog. Updated May 21, 2020. Accessed July 9, 2020. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20200519.916904/full/

- 6.Cutler DM, Frank RG, Gruber J, Newhouse JP Strengthening The Medicare Trust Fund In The Era Of COVID-19. Health Affairs Blog. Updated June 10, 2020. Accessed July 9, 2020. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20200608.322412/full/

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix