Abstract

Congenital obstructive nephropathy hinders normal kidney development. The severity and the duration of obstruction determine the compensatory growth of the contralateral, intact opposite kidney. We investigated the regulation of renal developmental genes, that are relevant in congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract (CAKUT) in obstructed and contralateral (intact opposite) kidneys after unilateral ureteral obstruction (UUO) in neonatal and adult mice. Newborn and adult mice were subjected to complete UUO or sham-operation, and were sacrificed 1, 5, 12 and 19 days later. Quantitative RT-PCR was performed in obstructed, intact opposite kidneys and sham controls for Gdnf, Pax2, Six4, Six2, Dach1, Eya1, Bmp4, and Hnf-1β. Neonatal UUO induced an early and strong upregulation of all genes. In contrast, adult UUO kidneys showed a delayed and less pronounced upregulation. Intact opposite kidneys of neonatal mice revealed a strong upregulation of all developmental genes, whereas intact opposite kidneys of adult mice demonstrated only a weak response. Only neonatal mice exhibited an increase in BMP4 protein expression whereas adult kidneys strongly upregulated phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase class III, essential for compensatory hypertrophy. In conclusion, gene regulation differs in neonatal and adult mice with UUO. Repair and compensatory hypertrophy involve different genetic programs in developing and adult obstructed kidneys.

Subject terms: Nephrology, Kidney, Kidney diseases

Introduction

Congenital obstructive nephropathy is a frequent cause of kidney failure in infants and children1–3. In contrast to adult kidneys, obstruction in a developing kidney induces severe disruption of nephron maturation and dramatic reduction of functioning nephrons4,5. The development of congenital obstructive nephropathy is regulated by a complex interplay of genetic and non-genetic factors3. Histologically, congenital obstructive nephropathies are characterized by dysplastic renal growth, interstitial fibrosis and compensatory growth of the intact opposite kidney6. Compensatory hypertrophy in the contralateral kidney is different from normal renal growth7–10. Two mechanisms are involved in this process: hypertrophy, defined as an increase in nephron size and mass, and hyperplasia, defined as an increase in nephron cell number9. The degree of compensatory hypertrophy has been shown to correlate with the extent of obstruction, loss of function in the affected kidney, and level of phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase class III (Pik3c3) expression in the intact opposite kidney of adult mice7,10–12.

Several genes are of major importance for renal development and represent candidate genes for congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract (CAKUT). These genes may also play a role in repair, regeneration and compensatory growth after renal injury. We studied the regulation of renal developmental genes that are associated with CAKUT in obstructed, intact opposite and sham-operated kidneys following unilateral ureteral obstruction (UUO) in newborn and adult mice: Gdnf (Glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor), Pax2 (Paired homeobox gene 2), Six4 (Sineoculis homeobox homolog 4), Six2 (Sineoculis homeobox homolog 2), Dach1 (Dachshund homolog 1), Eya1 (Eyes absent homolog 1), Bmp4 (Bone morphogenetic protein 4), and Hnf-1β (Hepatocyte nuclear factor-1β). Knockout-data for these genes emphasize a possible involvement of these genes with renal malformation13–15. Some of these genes may also be involved in repair and regeneration following renal injury. In kidney development, nephron progenitor cells are a transient developmental cell type that gives rise to nephrons. Nephron progenitor cells fully differentiate in mice by postnatal day 5. Many of the genes studied here are only expressed in nephron progenitor cells (Gdnf16, Six217, Eya118, HNF-1ß19 and Six46) and are not present in the adult kidney. They were assayed following ureteral obstruction as an upregulation of these genes would indicate a novel repair mechanism involving possible re-activation of the developmental program or de-differentiation of existing cells in the adult kidney.

In kidney development, Gdnf promotes the branching and regulates the length of the ureteric bud and further differentiation of the mesenchyme16,20. Gdnf non-synonymous deleterious variants are reported in about 5% of CAKUT patients21. Pax2 is a key transcriptional factor in nephron specification22. Autosomal dominant mutations in the PAX2 gene cause the renal-coloboma syndrome23. It is highly expressed in proliferative tissue24 and has anti-apoptotic effects25,26. In models of renal ischemia and acute tubular necrosis Pax2 is re-expressed27,28 and required for kidney repair29. Six2 is essential during all stages of kidney development15,17. Deficiency in Six2 during prenatal development is associated with reduced nephron number, chronic renal failure, and hypertension14. SIX2 mutations have been observed in children with renal hypodysplasia30. DACH1 is found in developing human kidneys where it inhibits TGF-β-induced apoptosis31. It is a transcription factor that is important for podocyte differentiation and kidney function32. EYA1 is essential for human kidney development33,34. Eya1−/−-knockout-mice show renal agenesis, and mutations in the human Eya1 gene cause branchio-oto-renal (BOR)-syndrome34. Eya1 interacts strongly with Six1 and Six4 to regulate nephron progenitor cells18. Six1/Six4 deficiency leads to kidney and ureter agenesis35. Bmp4, a member of the TGF-ß family, promotes proliferation, has anti-apoptotic effects and is essential for the outgrowth and positioning of the ureteric bud36,37. Bmp4+/−-knockout-mice show a variety of kidney malformations, ranging from renal hypodysplasia and hydronephrosis to polycystic kidneys36–38. BMP4 mutations have been reported in children with renal hypodysplasia30,39,40. Hnf-1β regulates gene expression in kidney, liver and other epithelial organs19,41. During embryogenesis, Hnf-1β is required for initiation of nephrogenesis, ureteric bud branching, and nephron segmentation42. Dominant-negative expression of Hnf-1β leads to cyst formation and hydroureters25. Mutations of HNF-1β in humans produce maturity-onset diabetes of the young type 5 (MODY5) and cystic abnormalities of the kidney (renal cyst and diabetes-syndrome, RCAD-syndrome).

Several animal models have shown that renal malformations can be caused by obstruction of the urinary tract1,43,44. Neonatal UUO interferes with normal nephrogenesis and branching morphogenesis. In order to study the effect of an early obstruction during kidney development on the regulation of these genes in the obstructed kidneys as well as the intact opposite kidneys, we performed unilateral ureteral obstruction (UUO) in newborn and adult mice. In humans, nephrogenesis is completed before birth, but in mice, it continues for 1–2 weeks after birth. Therefore, neonatal UUO at the second day of life serves as a model to study the effects of urinary tract obstruction on renal development1,45. In this study, we demonstrate that renal developmental gene regulation differs in neonatal and adult mice upon ureteral obstruction. Our findings support differential regeneration and repair processes in neonatal versus adult mice with UUO.

Materials and methods

Experimental protocol

Two-day-old WT mice (C57/BL6) and 7–8 week old adult mice were subjected to complete left ureteral obstruction or sham operation under general anesthesia with isoflurane (3–5% v/v) and oxygen (0.5 L/min) on the second day of life, and at 7–8 weeks, respectively, as described before46. The sex distribution was in both groups equal. After recovery, neonatal mice were returned to their mothers until sacrifice 1, 5, 12 and 19 days after surgery (n = 16 per group). The adult mice were also sacrificed 1, 5, 12 and 19 days after surgery (n = 16 per group). All experiments were performed according to national animal protection laws and the guidelines of animal experimentation established and approved by the Regierungspräsidium Karlsruhe and the Committee for Animal Experimentation of the University of Heidelberg (Az 35–9185.81/G-89/05).

Real-time quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

Kidneys from neonatal and adult mice were harvested 1, 5, 12, and 19 days after UUO or sham-operation (n = 4 in each group). Using Quiagen, RNA was isolated (Sigma, Munich) and checked for integrity. RNA was quantified photometrically. Real time RT-PCR was performed using oligo(dT)/random hexamer primers (10:1). One microgram of RNA was reverse transcribed using the Abi Prism 7000 Real Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Darmstadt) with specific primers for 18S, mouse-Gdnf, -Pax2, -Six4, -Six2, -Dach1, -Eya1, -Bmp4, and -Hnf-1β (Table 1), and Universal Mastermix (Applied Biosystems) with SYBR green to measure PCR products. All the primer pairs have been purchased from Applied Biosystems. We used serial dilutions of an arbitrary cDNA pool to generate a standard curve. Levels of mRNA were normalized to corresponding 18S quantities measured within the same run. Relative amount of mRNA was calculated using comparative Ct (ΔCt) method.

Table 1.

Real time RT-PCR primer sequences.

| Gene | Forward primer | Reverse primer |

|---|---|---|

| 18S | AGTTGGTGGAGCGATTTGTC | GCTGAGCCAGTTCAGTGTAGC |

| Gdnf | CGCTGACCAGTGACTCCAATAT | TTCAGTCTTTTAATGGTGGCTTGA |

| Pax2 | CGAGGAAGTCGAGGTATACACTGA | GCAGGTGCTTCCGCAAAC |

| Six 4 | CAGCTTCACAAGGTAATCTTTCAGTTAC | AGGAACGGTGTATACCACTGCA |

| Eya1 | GAATTTCCTCCTATGGTGCATTGT | GGTAGCTGTACGGTGCCTGTC |

| Hnf-1β | AGATGTCAGGAGTGCGCTACAA | CTGGTCACCATGGCACTGTTA |

| Six2 | ACCACGCAAGTCAGCAACTG | TTGTGGCTGCTGGAATTGG |

| Dach1 | GTTGGCAGCAGTGGTGGTT | CAGATGGTTGAGAGGATGGCTAA |

| Bmp4 | GTGAGGAGTTTCCATCACGAAGAA | GGATGCTGCTGAGGTTGAAGAG |

Identification of proliferation and BMP4

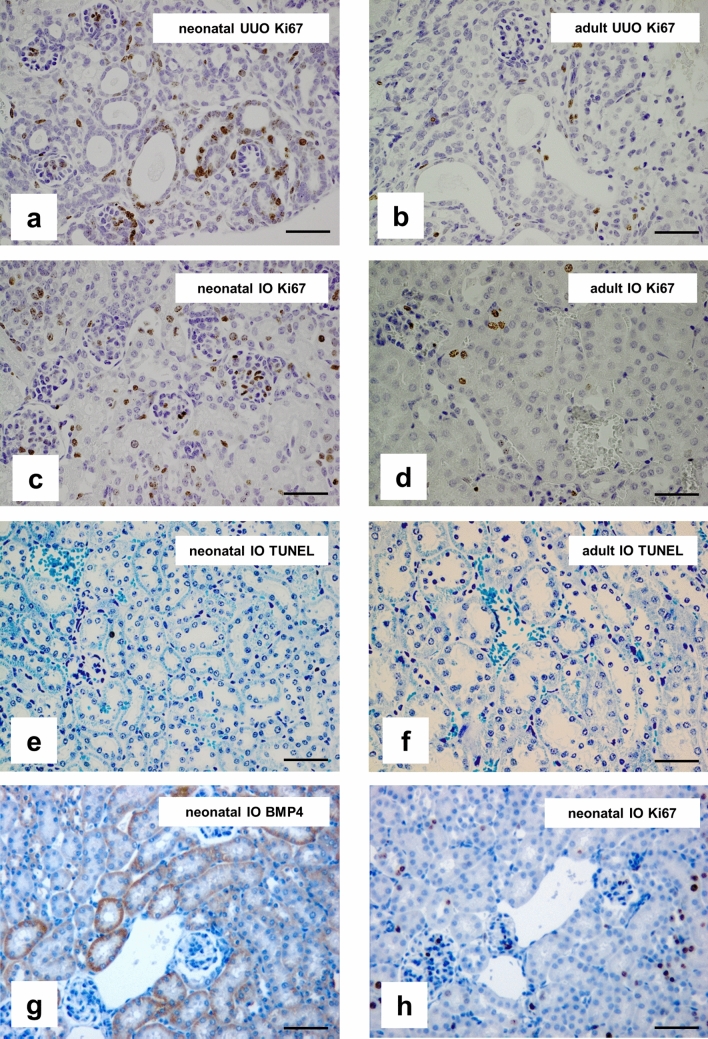

Proliferation and BMP4 expression were examined by immunohistochemistry as described previously45. Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded sections of UUO-, IO- and sham-operated kidneys of newborn and adult mice (n = 8 per time point) were subjected to antigen retrieval and incubated with Ki67 antibody (DAKO M7248) to stain proliferating nuclei, or with BMP4 antibody (ab 6296, Abcam). Control sections were stained simultaneously with a non-specific, species-controlled primary antibody. We used biotinylated goat anti-rat IgG (Southern Biotechnology Associates, Inc., Birmingham, AL) as secondary antibody. After incubation with ABC reagent (Vectastain, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and counterstaining with hemalaun, proliferation was calculated by counting the number of Ki67 positive cells in 20 sequentially selected microscopic high power fields (hpfs) at × 400 magnification. Proliferation was expressed as the mean number of Ki67 positive cells per hpf. Photomicrographs of proliferating cells and BMP4 expression in the obstructed and intact opposite kidney of adult and newborn mice are shown in Fig. 5.

Figure 5.

Proliferation is higher in neonatal kidneys and does not co-localize to BMP4. Immunohistochemical staining of Ki67 in neonatal UUO kidneys (a), adult UUO kidneys (b), neonatal intact opposite kidneys (c), and adult intact opposite kidneys (d) 5 days after surgery. Dark brown nuclei indicate Ki67 positive proliferating cells. TUNEL staining for renal apoptosis in neonatal intact opposite kidneys (e) and adult intact opposite kidneys (f) 19 days after surgery. BMP4 is expressed in tubular cells of neonatal intact opposite kidneys (g) and does not co-localize to proliferating cells (h). A photograph of an obstructed (UUO) kidney at day 5 after ureteral obstruction is in supplementary material (Supplementary Figure S13) online. Staining of sham-operated controls are in supplementary material (Supplementary Figure S14) online. Bar = 100 μm. Magnification of 200 ×.

Detection of cellular apoptosis

Apoptotic cells were detected by the terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT)- mediated dUTP-biotin nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay as described previously4. Briefly, formalin-fixed tissue sections were de-paraffinized and rehydrated followed by incubation with proteinase K (20 µg/ml). After quenching, equilibration buffer was applied, followed by working strength enzyme (ApopTag Peroxidase In Situ Apoptosis Detection Kit, Millipore, Schwalbach, Germany). Cells were regarded as TUNEL positive if their nuclei were stained black and displayed typical apoptotic morphology. Apoptosis was calculated in neonatal mice (n = 8 per time point) by counting the number of TUNEL positive cells in 20 sequentially selected microscopic fields of view (hpfs) at × 400 magnification and expressed as the mean number of cells per hpf.

Western immunoblotting

Kidneys of UUO and control mice were harvested on 1, 5, 12 and 19 days after obstruction (n = 3 in each group) as described previously4. In brief, kidneys were homogenized in protein lysis buffer (Triton-X 100 1%, Tris 100 mM, Na4P2O3 100 mM, NaF 100 mM, EDTA 10 mM) containing a cocktail of proteinase and phosphatase inhibitors (1 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM PMSF, 10 µg/ml leupeptin, 10 µg/ml aprotinin) and centrifuged for 60 min at 20,000×g. The protein content of the supernatants was measured using the BCA Protein Assay Kit (Pierce #23225). 15–20 µg of protein were separated on polyacrylamide gels at 180 V for 45 min and blotted onto nitrocellulose membranes (105 V, 80 min). After blocking antibody-specific for 2 h in Tris-buffered saline with Tween-20 containing 5% nonfat dry milk and/or BSA, blots were incubated with primary antibodies 2 h at room temperature or at 4 °C overnight. Gdnf antibody (Abcam plc, Cambridge, UK, ab 17732; 1:1000), BMP4 antibody (clone V9, Sigma, Germany, V-6630; 1:200), Pik3c3 antibody (Echelon Biosciences, Z-R016, 1:100) were used for western blot analysis. GAPDH (DUNN Labortechnik H86540M) was used as an internal loading control and to normalize samples. Blots were washed with Tris-buffered saline with Tween-20 and incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature. Immune complexes were detected using enhanced chemiluminescence method. Blots were exposed to x-ray films (Kodak, Stuttgart, Germany), the films were scanned and protein bands were quantified using the densitometry program Image J. Each band represents one single mouse kidney.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± standard error. Comparisons between groups were made using one-way analysis of variance followed by the Student–Newman–Keuls test. Comparisons between left and right kidneys were performed using the Students t-test for paired data. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

Results

Gene regulation differs in neonatal and adult kidneys

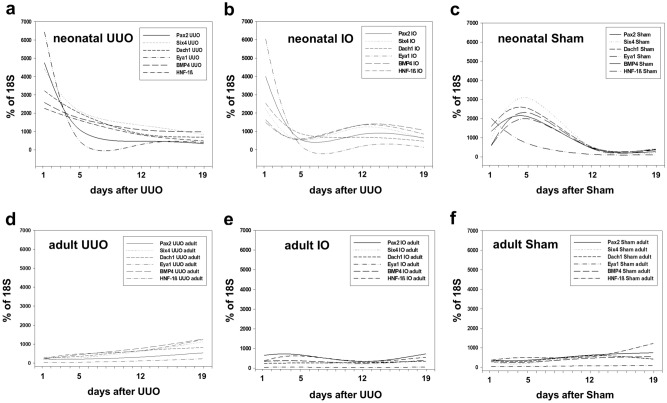

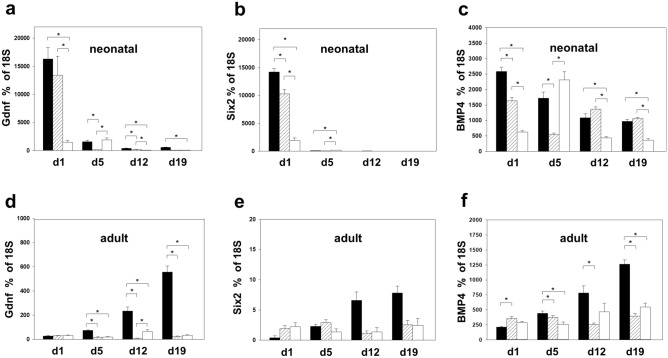

Developmental genes were analyzed in neonatal and adult kidneys with unilateral ureteral obstruction (UUO) at 1, 5, 12, and 19 days after surgery (n = 4 in each group) (Figs. 1 and 2). Quantitative RT-PCR for Pax2, Six4, Dach1, Eya1, Bmp4, Hnf-1β, Gdnf, and Six2 was performed in obstructed (UUO), intact opposite (IO), and sham-operated kidneys (Sham). UUO resulted in a significant mRNA-upregulation of all developmental genes in neonatal obstructed and intact opposite kidneys compared to sham operated controls (Figs. 1a–c and 2a–c). This upregulation was strongest directly after UUO was performed (d1) and decreased toward day 19. Adult kidneys showed a weaker gene expression than neonatal kidneys with a delayed upregulation (d12, d19) in obstructed kidneys, and transient upregulation of only Pax2 at d1 and d5 in intact opposite kidneys compared to sham operated controls (Fig. 1d–f). In neonatal obstructed kidneys Gdnf showed the highest mRNA-expression (Fig. 2a), followed closely by Six2 (Fig. 2b). Neonatal contralateral (IO) kidneys showed a parallel expression pattern with initial upregulation of all genes on day 1 (Fig. 2a,b). Only Bmp4 mRNA showed an early upregulation in intact opposite kidneys of neonatal mice following UUO (Fig. 2c). This Bmp4 upregulation in IO-kidneys remained significant 12 and 19 days after obstruction (n = 4 in each group) (Fig. 2c). Adult obstructed kidneys showed no initial upregulation on day 1 after UUO (Fig. 2d–f). Particular genes showed increased expression beginning on day 12: Gdnf and Bmp4 (Fig. 2d,f). By contrast, Six2 was not present in the adult kidney. Intact opposite kidneys of adult mice showed no Bmp4 upregulation from d1 to day 19 after surgery (Fig. 2f).

Figure 1.

Differential renal developmental gene expression in neonatal and adult mouse kidneys after unilateral ureteral obstruction (UUO). Quantitative RT-PCR of renal developmental genes in neonatal and adult kidneys of WT mice 1, 5, 12, and 19 days after UUO. Surgery was performed in neonatal mice on the second day of life (a–c) and in adult mice at the age of 7–8 weeks (d–f). A second scale that shows the early postnatal age (d1–d7 after surgery) is in supplementary material (Supplementary Figure S10) online. IO = intact opposite kidney, Sham = sham-operated kidney.

Figure 2.

Gdnf, Six2 and BMP4 mRNA message in neonatal and adult mouse kidneys after UUO. Gdnf, Six2 and BMP4 gene expression were measured in UUO-, intact opposite (IO)-, and sham-operated kidneys of neonatal (a–c) and adult (d–f) mice by quantitative RT-PCR. Gdnf showed the highest upregulation after UUO, followed by Six2. Neonatal but not adult intact opposite kidneys upregulated BMP4 mRNA. Additional graphs for Pax2, Six4, Dach1, HNF-1ß and Eya1 are in supplementary material (Supplementary Figure S11 and S12) online. UUO = obstructed kidneys (black), IO = intact opposite kidneys (striped), sham = sham operated (white). n = 4; *p < 0.05.

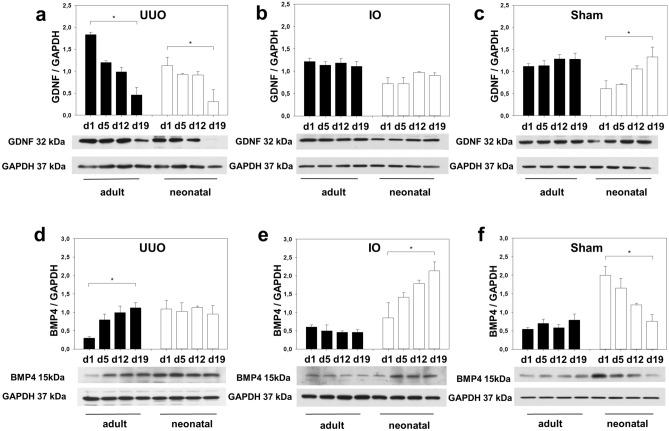

GDNF and BMP4 protein expression after UUO. BMP4 expression increases only in neonatal but not in adult intact opposite kidneys

We next questioned whether the difference in Gdnf and Bmp4 message following UUO was mirrored by the GDNF and BMP4 protein expression in the obstructed, intact opposite, and sham-operated kidney of newborn and adult mice using Western blot (n = 3 in each group). As shown in Fig. 3a, GDNF expression markedly decreased in both adult and neonatal mice following UUO. Similarly, GDNF abundance was equal in IO- and sham operated kidneys of neonatal and adult mice (Fig. 3b,c). In contrast BMP4 expression was markedly upregulated in adult UUO-kidneys following obstruction but did not change in neonatal kidneys with UUO (Fig. 3d). In intact opposite kidneys of neonatal mice BMP4 was highly expressed (Fig. 3e). In contrast, BMP4 did not change in adult IO-kidneys after surgery. Sham operated kidneys of neonatal mice showed a marked decrease in BMP4 expression (Fig. 3f). These results suggest that BMP4 may be involved in compensatory growth in neonatal IO-kidneys.

Figure 3.

Gdnf expression decreased after UUO and BMP4 increased in neonatal intact opposite kidneys with compensatory renal growth. Neonatal mice (white bars) and adult mice (black bars) were subjected to UUO or sham operation. Whole kidneys were processed for western blot analysis at day 1, 5, 12, and 19 after surgery. Gdnf was reduced in both neonatal and adult UUO-kidneys (a). Gdnf expression did not change in intact opposite kidneys (b), but increased in sham-operated neonatal kidneys (c). BMP4 expression increased in adult UUO-kidneys (d) and in neonatal intact opposite kidneys (e) after obstruction. BMP4 decreased in neonatal sham-operated controls (f). The shown western blot images are cropped, for uncropped western blots see Supplementary Fig. S1–S6 online. For details on significance between groups see Supplementary Table S1 online. n = 3; *p < 0.05.

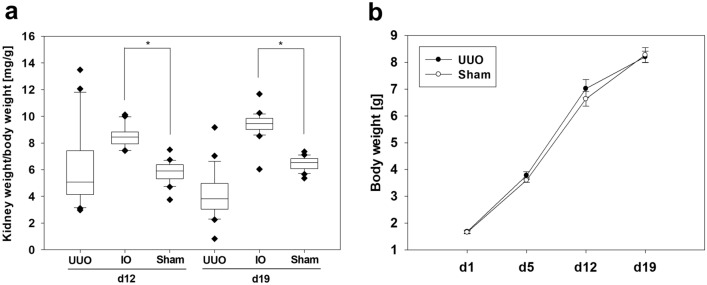

Kidney to body weight ratio indicates compensatory growth of neonatal IO-kidneys

The kidney and body weights of neonatal mice were measured on days 12 and 19 after surgery (n = 20 per group) (Fig. 4a). The kidney weight/body weight ratio in mg/g was calculated. The kidney weight/body weight ratios of intact opposite (IO) kidneys were significantly higher than of the sham-operated kidneys on both days after surgery. UUO did not cause any differences in body weight of mice compared to the sham-operated controls (Fig. 4b). These data confirm the compensatory growth of the intact opposite kidney.

Figure 4.

Kidney weight of neonatal intact opposite kidneys increased after UUO. Kidney weight/body weight ratio [mg/g] from neonatal mice after 12 and 19 days of unilateral ureteral obstruction (UUO) (a). The weight of the intact opposite kidney (IO) was on average significantly higher than the weight of the sham-operated kidney. There was no difference in the body weight gain between mice with UUO or sham operation (b). UUO/IO n = 20, sham n = 20; *p < 0.05.

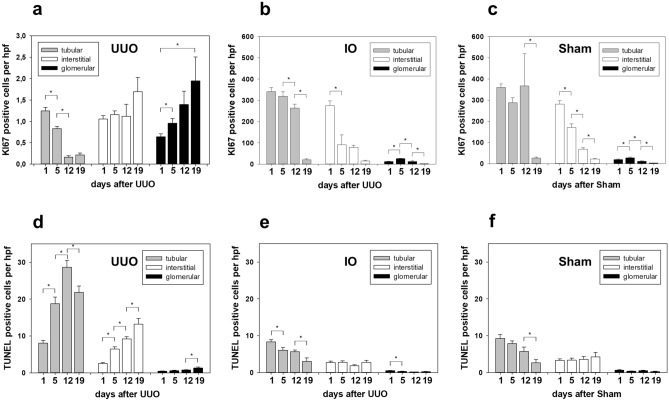

Proliferation, apoptosis and localization of BMP4

Proliferation of tubular, glomerular, and interstitial cells was studied in newborn and adult mice kidneys following UUO using Ki67 immunostaining (Fig. 5a–d). Proliferation was higher in neonatal UUO kidneys (Fig. 5a) and neonatal intact opposite kidneys (Fig. 5c) than in adult UUO kidneys (Fig. 5b) and adult intact opposite kidneys, respectively (Fig. 5d). Apoptosis was hardly detectable in kidneys with compensatory growth (Fig. 5e,f). BMP4 expression localized to proximal and distal tubular structures in intact opposite kidneys of neonatal mice (Fig. 5g). No co-localization of BMP4 expression and Ki67 positive cells in intact opposite kidneys of neonatal mice was observed, suggesting that BMP4 may induce nephron hypertrophy without stimulating proliferation (Fig. 5g,h).

Proliferation and apoptosis in neonatal kidneys after UUO

Proliferation and apoptosis of tubular, interstitial and glomerular cells were analyzed using Ki67 and TUNEL staining in obstructed (UUO), intact opposite (IO) and sham-operated (Sham) kidneys (Fig. 6). Following obstruction, proliferation decreased significantly in tubular cells of UUO kidneys (Fig. 6a). In contrast, proliferation of tubular cells in the intact opposite kidney was 300 × times higher than in obstructed neonatal kidneys (Fig. 6b). Sham operated controls indicated the highly proliferative status of the developmental neonatal kidney (Fig. 6c). Apoptosis increased significantly in the neonatal kidney with UUO (Fig. 6d). By contrast, apoptosis was low in intact opposite kidneys (Fig. 6e) and sham operated controls (Fig. 6f).

Figure 6.

Proliferation and apoptosis in neonatal kidneys after UUO. Renal sections of UUO-, IO- and sham-operated kidneys of neonatal mice were stained for tubular (gray bars), interstitial (white bars) and glomerular (black bars) proliferation (Ki67 antibody) (a–c) and apoptosis (TUNEL) (d–f) at 1, 5, 12 and 19 days after surgery and analyzed in 20 high-power fields (hpf) per section at × 400. For details on significance between groups see Supplementary Table S2 online. n = 8; *p < 0.05.

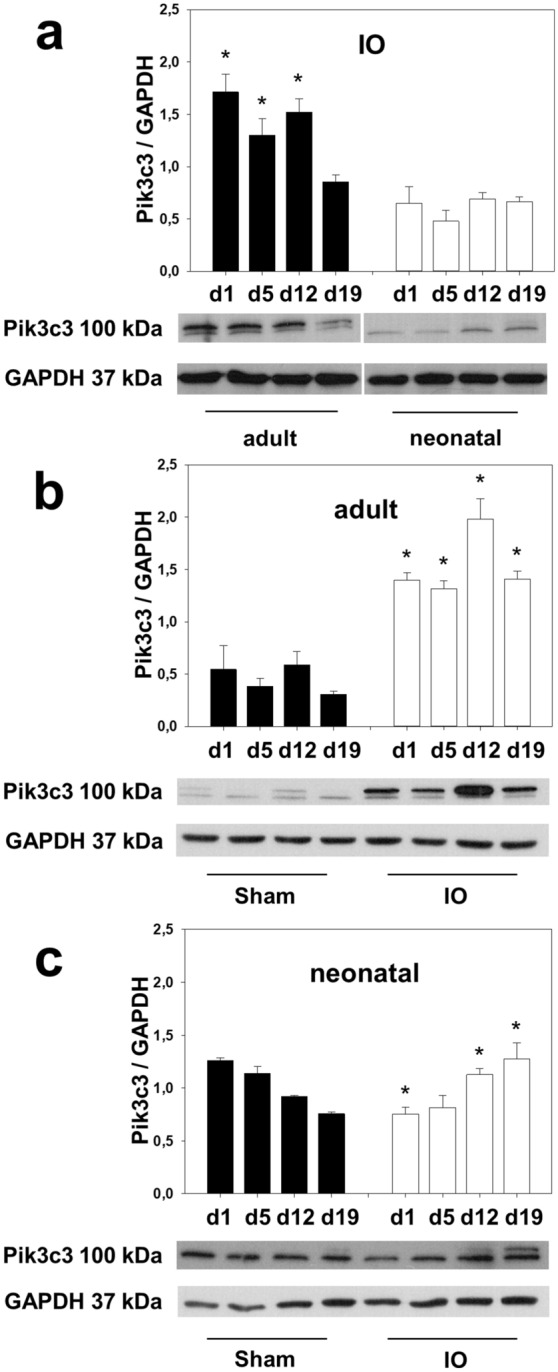

Pik3c3 expression

We analyzed Pik3c3, which controls compensatory nephron hypertrophy in obstructed (UUO), intact opposite (IO) and sham-operated (Sham) kidneys of neonatal and adult mice at 1, 5, 12, and 19 days after surgery using Western blot (n = 3 in each group) (Fig. 7). Pik3c3 expression increased in the intact opposite kidneys of adult mice following surgery (Fig. 7a,b), suggestive of mediating the compensatory nephron growth in the contralateral kidney. For the first time we could show an upregulation of Pik3c3 in neonatal IO-kidneys, which was less pronounced (Fig. 7a,c), indicating a different regulation of compensatory hypertrophy in neonatal and adult mice after renal injury.

Figure 7.

Phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase class III (Pik3c3) expression is upregulated in intact opposite kidneys. Neonatal and adult mice were subjected to UUO or sham operation. Whole kidneys were processed for western blot analysis at day 1, 5, 12, and 19 after surgery. Pik3c3 expression, which controls compensatory hypertrophy, was strongly upregulated in adult intact opposite kidneys (a and b) and less in neonatal IO-kidneys (a and c). The shown western blot images are cropped, for uncropped western blots see Supplementary Fig. S7–S9 online. For additional blots on Pik3c3 expression in UUO and sham-operated kidneys see Supplementary Figure S15. For details on significance between groups see Supplementary Table S3 online. n = 3; *p < 0.05. Significance markings reflect the differences between groups, compared to each other on the same points in time. The images for (a) were rearranged for uniform presentation. The brightness of the western blot images was changed after the analysis for uniform presentation.

Discussion

This study addresses the effect of early renal obstruction on the regulation of renal developmental genes (Gdnf, Pax2, Six4, Six2, Eya1, Dach1, Bmp4 and Hnf-1β) in the obstructed as well as the intact opposite kidneys. In addition, it compares how genes that are associated with CAKUT are regulated in neonatal and adult kidneys after UUO. Our model demonstrated that the regulation of renal developmental genes differs significantly in both the obstructed and the intact opposite kidneys of neonatal versus adult mice. While neonatal mice showed an early upregulation of all developmental genes in both obstructed and intact opposite (IO) kidneys, adult mice exhibited a reversed expression pattern with a delayed and mostly weaker mRNA increase.

In neonatal UUO-kidneys Gdnf showed the highest mRNA upregulation followed closely by Six2, Eya1, Pax2, and Six4. Dach1, Bmp4, and Hnf-1β showed a weaker but still significant mRNA increase following UUO in neonatal mice. Neonatal contralateral kidneys demonstrated a parallel expression pattern with initial upregulation of all genes after obstruction. Gdnf, Six2, Eya1, Pax2 and Dach1 message was almost as strong in neonatal IO-kidneys as in neonatal UUO-kidneys. This dramatic upregulation of developmental genes in neonatal kidneys shows that nephron progenitor cells are present and stimulated following injury. Postnatal nephrogenesis in mice is tightly regulated47; it ceases in the first 5 days after birth and nephron progenitor cells that express developmental genes are no longer present. Our findings are in line with this showing that adult mice with completed nephrogenesis showed a delayed and much weaker gene response with transient upregulation of only Pax2. This upregulation of Pax2 in adult mice probably occurs in association with the proliferative response to renal injury29. Pax2 is a survival factor for renal collecting duct cells and was upregulated in tubular cells after ischemia28. Only Pax2 positive tubular cells underwent complete mitosis after kidney injury, making it an important factor for proliferation and repair47. PAX2 protein is expressed in collecting duct cells, but also in cells of the connecting tubule and the thick ascending limb, as well as in fibroblasts and proximal tubular cells. Here we show that Pax2 is upregulated after UUO, possibly in order to induce regeneration and repair processes. The upregulation of developmental genes is substantially stronger and faster in neonatal than in adult kidneys. While neonatal kidneys react with an immediate upregulation of certain developmental genes as early as 24hours after damage by obstruction, indicating that they may be able to directly stimulate their developmental program, adult kidneys only show partial and weaker upregulation after 2 weeks of persisting damage. This inverse regulation of renal developmental genes implies that regenerative and repair processes are different in neonatal and adult kidneys.

Most of the genes in this study promote proliferation and inhibit apoptosis. Gdnf, which showed highest mRNA expression in neonatal UUO and IO-kidneys, may act as a survival factor following obstruction. Gdnf expression has been shown to be upregulated after podocyte injury, and to inhibit apoptosis and promote differentiation48. In our study, Gdnf mRNA message was upregulated early in obstructed and contralateral kidneys of neonatal mice followed by a strong decrease in Gdnf message over time. Accordingly, Gdnf protein expression decreased significantly in the neonatal UUO-kidney indicating the severe disruption of nephron maturation after obstruction. Only intact opposite and sham-operated kidneys of neonatal mice demonstrated an increase in Gdnf expression, likely reflecting the renal developmental stage. Correspondingly, the Gdnf upregulation was not present in kidneys of adult mice with completed nephrogenesis. A combination of Pax2, Eya1, and most importantly Six2 regulate the Gdnf gene expression49. Our finding that upregulation of Six2 mRNA was synchronized with Gdnf message are in line with those observations. The rapid decline of both genes in neonatal kidneys can be explained by the loss of Six2 during nephrogenesis50. Lineage tracing studies have shown that all nephron cell types are formed from the Six2-expressing cap mesenchyme, which is not present in the human postnatal kidney but is still present in the mouse postnatal kidney until nephrogenesis ends17. The loss of the Six2 progenitor population therefore restricts the options for regeneration and repair. Nevertheless, the neonatal as well the adult kidney can undergo substantial repair and stimulate compensatory growth in the intact opposite kidney.

Proliferation of tubular and glomerular cells is significantly higher in neonatal than adult kidneys and compensatory renal growth of the contralateral kidney is stronger in neonatal than adult UUO11. Accordingly, the calculated kidney weight/body weight ratio of neonatal mice after UUO showed a clear compensatory hypertrophy of the intact opposite kidney in comparison to the sham-operated control. This process of compensatory hypertrophy is regulated by different genes and signaling pathways. In a neonatal UUO model on fetal sheep, numerous protein coding genes could be identified that are differentially regulated following obstruction8. In adult UUO models, upregulated genes in the contralateral kidney belong mostly to transporter and membranes families and are associated with metabolism51. Our data here demonstrated a possible involvement of Bmp4 in compensatory renal growth in neonatal mice with UUO. BMP4 expression increased markedly in intact opposite kidneys of neonatal mice but not in adult mice, suggesting a unique BMP4 dependent repair mechanism in the developing kidney with injury. Developmental gene Bmp4 promotes proliferation in the metanephric mesenchyme and inhibits apoptosis in several tissues36. BMP4 has been found to play a crucial role in wound healing response and thymic regeneration52,53; it triggers pulmonary vascular remodeling and supports self-renewal of embryonic stem cells54,55, emphasizing its importance for regenerative processes. BMP4 is linked to pathological cardiac hypertrophy through activation of proliferation pathways56,57; thus, it may also contribute to compensatory renal growth. In our study BMP4 did not co-localize to Ki67 positive proliferating cells in the intact opposite kidney of neonatal mice, suggesting that BMP4 mediates nephron hypertrophy without stimulating proliferation.

To address the question whether compensatory renal growth of the intact opposite kidney is associated with higher proliferation, Ki67 expression was measured in the obstructed, intact opposite and sham-operated kidneys in neonatal mice after UUO. Interestingly, there was no significant difference in the number of Ki67 positive cells between neonatal IO-kidneys and sham-operated controls. Ki67 starts being expressed in the G1 phase, thus it is a marker for cells that have entered the cell cycle9,58. It does not differentiate between successful proliferation, resulting in hyperplasia, and cells in cell cycle arrest, leading to hypertrophy. Additionally, measurements of apoptosis did not show significant differences between neonatal IO-kidneys and sham-operated controls. Thus, proliferation and apoptosis do not seem to lead to compensatory growth of the neonatal contralateral kidney. Given this, alternative mechanisms of compensatory renal growth were elaborated.

Compensatory growth is different from normal growth. At a cellular level, it is predominantly characterized by cellular hypertrophy (increased cell size and mass), and less by hyperplasia (increased cell number)59. Increased cell size is due to stimulated RNA and protein synthesis, which is regulated by mTORC1 (mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1) signaling. Recently it could be shown that class III phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase (Pik3c3) acts upstream of mTORC1 signaling and mediates protein synthesis and nephron growth in adult mice after completion of nephrogenesis12. Pik3c3 is activated by increased amino acid delivery to the remaining kidney due to increased renal blood flow. The expression level of Pik3c3 controls the degree of contralateral renal growth, thus making it a suitable marker for it. Here we show for the first time, that Pik3c3 is upregulated in neonatal kidneys with compensatory hypertrophy. Pik3c3 expression was stronger in adult IO-kidneys compared to neonatal kidneys, emphasizing again the differential regulation in neonatal and adult kidneys after injury7,12. Even though the upregulation of Pik3c3 expression was less pronounced in neonatal IO-kidneys, it increased over time, in contrast to sham-operated controls. This indicates that protein synthesis, more so than increased proliferation or attenuated apoptosis, represents the driving force behind contralateral renal growth in both adult and neonatal kidneys.

Interaction between BMP4 and the Pik3/Akt pathway has been shown before60,61. However, it was not specified which class of Pik3 interacted with BMP4. We would like to speculate that BMP4 may be able to activate Pik3c3 and stimulate compensatory nephron hypertrophy in neonatal mice. Whether BMP4 and Pik3c3 interact in this specific setting needs to be studied in the future.

Together, these data show that certain renal developmental genes are upregulated after unilateral ureteral obstruction, possibly in order to induce regeneration and repair processes. This upregulation is substantially stronger and faster in neonatal than in adult kidneys. While neonatal kidneys directly stimulate their developmental program, adult kidneys only show partial and weaker upregulation after persisting damage. This implies that regenerative and repair processes are differentially regulated in neonatal and adult kidneys. Most of the genes in this study promote proliferation and inhibit apoptosis. They may contribute to compensatory growth processes in the contralateral kidney. However, increased proliferation and attenuated apoptosis appear to have only a minor influence on compensatory renal growth in the neonatal kidney. Protein synthesis seems to be the driving force behind the compensatory growth of the intact opposite kidney. This is mediated by Pik3c3, which is activated through increased renal blood flow in the contralateral kidney of neonatal and adult mice.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

Dr. Bärbel Lange-Sperandio is supported by a grant from the German Research Foundation (DFG La 1257/5-1).

Author contributions

Conceptualization, B.L.-S.; Methodology and Experimentation, M.J.K., M.W., M.G., U.K., S.W., F.S., and B.L.-S.; Data Analysis, M.J.K., M.W., M.G., U.K., and B.L.-S.; Resources, B.L.-S.; Writing, M.J.K., M.W., and B.L.-S.; Project Administration, B.L.-S.; Funding, B.L.-S.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Melanie J. Kubik and Maja Wyczanska.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-020-76328-3.

References

- 1.Klein J, et al. Congenital ureteropelvic junction obstruction: human disease and animal models. Int. J. Exp. Pathol. 2011;92:168–192. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2613.2010.00727.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Truong LD, Gaber L, Eknoyan G. Obstructive uropathy. Contrib. Nephrol. 2011 doi: 10.1016/B978-1-4377-1604-7.00125-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lange-Sperandio B. Pediatric obstructive uropathy. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2015 doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-27843-3_51-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Popper B, et al. Neonatal obstructive nephropathy induces necroptosis and necroinflammation. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-55079-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thornhill, B. A. & Chevalier, R. L. variable partial unilateral ureteral obstruction and its release in the neonatal and adult mouse. Methods Mol. Biol.886 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Rosen S, Peters CA, Chevalier RL, Huang WY. The kidney in congenital ureteropelvic junction obstruction: a spectrum from normal to nephrectomy. J. Urol. 2008;179:1257–1263. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.11.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen JK, et al. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling determines kidney size. J. Clin. Invest. 2015;125:2429–2444. doi: 10.1172/JCI78945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Springer A, et al. A fetal sheep model for studying compensatory mechanisms in the healthy contralateral kidney after unilateral ureteral obstruction. J. Pediatr. Urol. 2015;11(352):e1–352.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2015.04.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thomasova D, Anders HJ. Cell cycle control in the kidney. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2015;30:1622–1630. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfu395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koff SA, Peller PA, Young DC, Pollifrone DL. The assessment of obstruction in the newborn with unilateral hydronephrosis by measuring the size of the opposite kidney. J. Urol. 1994;152:596–599. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(17)32659-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yoo KH, Thornhill BA, Forbes MS, Chevalier RL. Compensatory renal growth due to neonatal ureteral obstruction: Implications for clinical studies. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2006;21:368–375. doi: 10.1007/s00467-005-2119-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu T, Dai C, Xu J, Li S, Chen J-K. The expression level of class III phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase controls the degree of compensatory nephron hypertrophy. Am. J. Physiol. Physiol. 2020;318:F628–F638. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00381.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davis TK, Hoshi M, Jain S. To bud or not to bud: the RET perspective in CAKUT. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2014;29:597–608. doi: 10.1007/s00467-013-2606-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fogelgren B, et al. Deficiency in Six2 during prenatal development is associated with reduced nephron number, chronic renal failure, and hypertension in Br/+ adult mice. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 2009;296:1166–1178. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.90550.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Self M, et al. Six2 is required for suppression of nephrogenesis and progenitor renewal in the developing kidney. EMBO J. 2006;25:5214–5228. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Costantini F, Shakya R. GDNF/Ret signaling and the development of the kidney. BioEssays. 2006;28:117–127. doi: 10.1002/bies.20357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Little MH, Kairath P. Does renal repair recapitulate kidney development? J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2017;28:34–46. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2016070748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu J, Xu PX. Eya-six are necessary for survival of nephrogenic cord progenitors and inducing nephric duct development before ureteric bud formation. Dev. Dyn. 2015;244:866–873. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.24282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gong Y, et al. HNF-1β regulates transcription of the PKD modifier gene Kif12. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2009;20:41–47. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008020238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li H, et al. Development of the urogenital system is regulated via the 3′UTR of GDNF. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:1–14. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-37186-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chatterjee R, et al. Traditional and targeted exome sequencing reveals common, rare and novel functional deleterious variants in RET-signaling complex in a cohort of living US patients with urinary tract malformations. Hum. Genet. 2012;131:1725–1738. doi: 10.1007/s00439-012-1181-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Naiman N, et al. Repression of interstitial identity in nephron progenitor cells by Pax2 establishes the nephron-interstitium boundary during kidney development. Dev. Cell. 2017;41:349–365.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2017.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ecoles MR, Schimmenti LA. Renal-coloboma syndrome: a multi-system developmental disorder caused by PAX2 mutations. Clin. Genet. 1999;56:1–9. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0004.1999.560101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Woolf AS, Winyard PJD. Molecular mechanisms of human embryogenesis: developmental pathogenesis of renal tract malformations. Pediatr. Dev. Pathol. 2002;5:0108–0129. doi: 10.1007/s10024001-0141-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paces-Fessy M, Fabre M, Lesaulnier C, Cereghini S. Hnf1b and Pax2 cooperate to control different pathways in kidney and ureter morphogenesis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2012;21:3143–3155. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Porteous S. Primary renal hypoplasia in humans and mice with PAX2 mutations: evidence of increased apoptosis in fetal kidneys of Pax21Neu +/− mutant mice. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2000;9:1–11. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maeshima A, Maeshima K, Nojima Y, Kojima I. Involvement of Pax-2 in the action of activin A on tubular cell regeneration. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2002;13:2850–2859. doi: 10.1097/01.ASN.0000035086.93977.E9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Perin L, et al. Protective effect of human amniotic fluid stem cells in an immunodeficient mouse model of acute tubular necrosis. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e9357. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sharma R, Sanchez-Ferras O, Bouchard M. Pax genes in renal development, disease and regeneration. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2015;44:97–106. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2015.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weber S, et al. SIX2 and BMP4 mutations associate with anomalous kidney development. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2008;19:891–903. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006111282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kozmik Z, et al. Pax-Six-Eya-Dach network during amphioxus development: conservation in vitro but context specificity in vivo. Dev. Biol. 2007;306:143–159. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Endlich N, et al. The transcription factor Dach1 is essential for podocyte function. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2018;22:2656–2669. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.13544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fujimura S, Jiang Q, Kobayashi C, Nishinakamura R. Notch2 activation in the embryonic kidney depletes nephron progenitors. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2010;21:803–810. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009040353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang C, et al. Six1 and Eya1 are critical regulators of peri-cloacal mesenchymal progenitors during genitourinary tract development. Dev. Biol. 2011;360:186–194. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kobayashi H, Kawakami K, Asashima M, Nishinakamura R. Six1 and Six4 are essential for Gdnf expression in the metanephric mesenchyme and ureteric bud formation, while Six1 deficiency alone causes mesonephric-tubule defects. Mech. Dev. 2007;124:290–303. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gonçalves A, Zeller R. Genetic analysis reveals an unexpected role of BMP7 in initiation of ureteric bud outgrowth in mouse embryos. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e19370. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ueda H, et al. Bmp in podocytes is essential for normal glomerular capillary formation. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2008;19:685–694. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006090983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang GJ, Brenner-Anantharam A, Vaughan ED, Herzlinger D. Antagonism of BMP4 signaling disrupts smooth muscle investment of the ureter and ureteropelvic junction. J Urol. 2009;181:401–407. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.08.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schild R, et al. Double homozygous missense mutations in DACH1 and BMP4 in a patient with bilateral cystic renal dysplasia. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2013;28:227–232. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfs539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saisawat P, et al. Identification of two novel CAKUT-causing genes by massively parallel exon resequencing of candidate genes in patients with unilateral renal agenesis. Kidney Int. 2012;81:196–200. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Igarashi P, Shao X, McNally BT, Hiesberger T. Roles of HNF-1β in kidney development and congenital cystic diseases. Kidney Int. 2005;68:1944–1947. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00625.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ferrè S, Igarashi P. New insights into the role of HNF-1β in kidney (patho)physiology. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2019;34:1325–1335. doi: 10.1007/s00467-018-3990-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Woolf AS, Lopes FM, Ranjzad P, Roberts NA. Congenital disorders of the human urinary tract: recent insights from genetic and molecular studies. Front. Pediatr. 2019;7:1–9. doi: 10.3389/fped.2019.00136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jain S, Chen F. Developmental pathology of congenital kidney and urinary tract anomalies. Clin. Kidney J. 2019;12:382–399. doi: 10.1093/ckj/sfy112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gasparitsch M, et al. Tyrphostin AG490 reduces inflammation and fibrosis in neonatal obstructive nephropathy. PLoS ONE. 2019;14:e0226675. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0226675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lange-Sperandio B, et al. Distinct roles of Mac-1 and its counter-receptors in neonatal obstructive nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2006;69:81–88. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lazzeri E, et al. Endocycle-related tubular cell hypertrophy and progenitor proliferation recover renal function after acute kidney injury. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:1–18. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03753-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tsui CC, Shankland SJ, Pierchala BA. Glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor and its receptor Ret is a novel ligand-receptor complex critical for survival response during podocyte injury. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2006;17:1543–1552. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005080835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brodbeck S, Besenbeck B, Englert C. The transcription factor Six2 activates expression of the Gdnf gene as well as its own promoter. Mech. Dev. 2004;121:1211–1222. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2004.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tögel F, et al. Repair after nephron ablation reveals limitations of neonatal neonephrogenesis. JCI Insight. 2017;2:1–13. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.88848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hauser P, et al. Transcriptional response in the unaffected kidney after contralateral hydronephrosis or nephrectomy. Kidney Int. 2005;68:2497–2507. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00725.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wertheimer T, et al. Production of BMP4 by endothelial cells is crucial for endogenous thymic regeneration. Sci. Immunol. 2018;3:eaal2736. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aal2736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Oumi N, et al. A crucial role of bone morphogenetic protein signaling in the wound healing response in acute liver injury induced by carbon tetrachloride. Int. J. Hepatol. 2012;2012:1–10. doi: 10.1155/2012/476820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Masterson JC, et al. Bone morphogenetic protein signalling in airway epithelial cells during regeneration. Cell. Signal. 2011;23:398–406. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2010.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Torres J, Prieto J, Durupt FC, Broad S, Watt FM. Efficient differentiation of embryonic stem cells into mesodermal precursors by BMP, retinoic acid and notch signalling. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e36405. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yuan Y, et al. BMP4 induces cardiomyocyte hypertrophy through the activation of ERK 1/2 signaling pathway in H9c2 cells. Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 2019;62:1–11. doi: 10.1590/1678-4324-2019180699. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sun B, et al. Bone morphogenetic protein-4 mediates cardiac hypertrophy, apoptosis, and fibrosis in experimentally pathological cardiac hypertrophy. Hypertension. 2013;61:352–360. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.00562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Juríková M, Danihel Ľ, Polák Š, Varga I. Ki67, PCNA, and MCM proteins: markers of proliferation in the diagnosis of breast cancer. Acta Histochem. 2016;118:544–552. doi: 10.1016/j.acthis.2016.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rojas-Canales DM, Li JY, Makuei L, Gleadle JM. Compensatory renal hypertrophy following nephrectomy: when and how? Nephrology. 2019;24:1225–1232. doi: 10.1111/nep.13578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shimizu T, Kayamori T, Murayama C, Miyamoto A. Bone morphogenetic protein (BMP)-4 and BMP-7 suppress granulosa cell apoptosis via different pathways: BMP-4 via PI3K/PDK-1/Akt and BMP-7 via PI3K/PDK-1/PKC. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2012;417:869–873. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.12.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lee MY, Lim HW, Lee SH, Han HJ. Smad, PI3K/Akt, and wnt-dependent signaling pathways are involved in BMP-4-induced ESC self-renewal. Stem Cells. 2009;27:1858–1868. doi: 10.1002/stem.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.