Abstract

Objective: Event notifications are real-time, electronic, automatic alerts to providers of their patients’ health care encounters at other facilities. Our objective was to examine the effects of organizational capability and related social/organizational issues upon users’ perceptions of the impact of event notifications on quality, efficiency, and satisfaction.

Materials and methods: We surveyed representatives (n = 49) of 10 organizations subscribing to the Bronx Regional Health Information Organization’s event notification services about organizational capabilities, notification information quality, perceived usage, perceived impact, and organizational and respondent characteristics. The response rate was 89%. Average item scores were used to create an individual domain summary score. The association between the impact of event notifications and organizational characteristics was modeled using random-intercept logistic regression models.

Results: Respondents estimated that organizations followed up on the majority (83%) of event notifications. Supportive organizational policies were associated with the perception that event notifications improved quality of care (odds ratio [OR] = 2.12; 95% CI, = 1.05, 4.45), efficiency (OR = 2.06; 95% CI = 1.00, 4.21), and patient satisfaction (OR = 2.56; 95% CI = 1.13, 5.81). Higher quality of event notification information was also associated with a perceived positive impact on quality of care (OR = 2.84; 95% CI = 1.31, 6.12), efficiency (OR = 3.04; 95% CI = 1.38, 6.69), and patient satisfaction (OR = 2.96; 95% CI = 1.25, 7.03).

Conclusions: Health care organizations with appropriate processes, workflows, and staff may be better positioned to use event notifications. Additionally, information quality remains critical in users’ assessments and perceptions.

INTRODUCTION

In the US health care system, patients typically seek care from many different providers and organizations, and communication between these organizations is of variable quality.1 Health care professionals are often unaware of their patients’ encounters with other providers.2 Patients themselves may perceive it as burdensome to serve as an information mediator, and may not provide detailed information because they do not understand what information is important to their care, mistakenly believe that health care organizations are already communicating with each other, or have privacy concerns.3–5

An event notification system is a type of information technology service designed to address some of the information and communication challenges resulting from fragmented care.6 Sometimes referred to as an alert or subscription service, event notification is the real-time, electronic, automatic alerting of providers to their patients’ health care encounters at other facilities.7 These event notifications are triggered by registration and discharge information recorded in hospitals’ admission-discharge-transfer (ADT) systems. A typical use case is to inform an ambulatory primary care provider as soon as one of his or her patients has been admitted to a local emergency department (ED).8 These systems fall under the broader category of health information exchange (HIE) technologies and may be offered by community health information organizations.6,8

Event notifications offer great potential for improving health care quality, not only by increasing providers’ general awareness of patient history,9,10 but also by prompting immediate intervention where appropriate.7 Health care organizations and individual providers report that event notifications have prompted telephone calls to patients, facilitated scheduling of post-discharge follow-up visits, and identified patients for referral to care coordination programs.9,11,12

Despite this promise, the pragmatic effectiveness of these systems is likely to be influenced by the recipient health care organization’s capabilities. An organization’s capabilities include the policies, workflow processes, and shared perceptions that enable the organization to pursue its goals and objectives.13,14 User requirement studies of multiple event notification systems, conducted during the formative phase of development and involving interviews with key informants, suggested that a health care organization probably requires certain types of infrastructure in order to be able to respond to event notifications: alerts should be integrated into organizational and clinical workflows, policies and procedures should specify how events should be handled, and skilled staff should be in place.7,12,15 However, the perspectives of managers and front-end users of an existing system may differ from the perspectives of key informants during the development phase.

We therefore drew upon previous findings and the broader sociotechnical perspective16–19 to conduct a survey study among users of a recently launched event notification system in a region with a large medically underserved population and a highly fragmented health care delivery system. Our objective was to examine the effects of organizational capability and related social/organizational issues upon users’ perceptions of the impact of event notifications on care quality, organizational efficiency, and patient satisfaction.

METHODS

Setting and Sample

We surveyed health care professionals at organizations subscribing to event notification services from the Bronx Regional Health Information Organization (RHIO) in New York City. The Bronx RHIO is a provider-governed NY State–certified clinical information exchange that facilitates health information exchange for more than 70 inpatient and ambulatory care organizations and includes information on nearly 2.3 million patients in the city’s poorest and most medically underserved borough. The Bronx RHIO, established in 2005, also offers a portal for querying patient information, a centralized data repository for analytics, a data availability flag for ED users (an indicator highlighting the existence of patient information from other providers), DIRECT messaging, and electronic referral messages.20

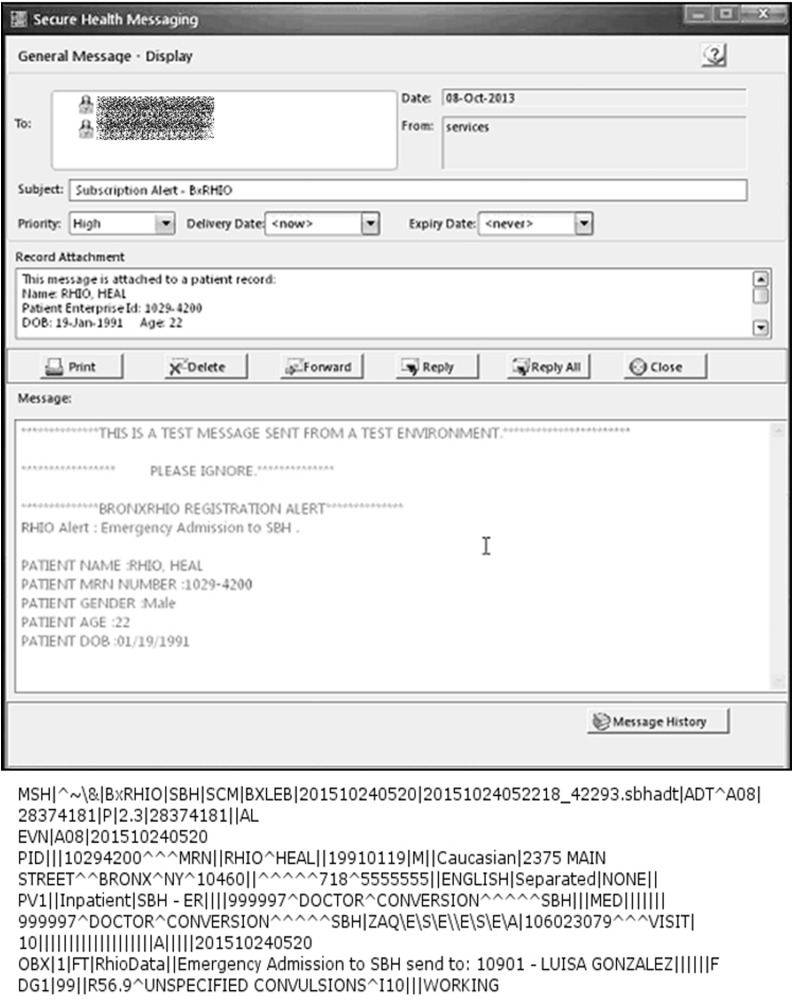

The Bronx RHIO launched an event notification system in December 2011. Using the ADT feeds from participating hospitals, the Bronx RHIO automatically notifies subscribers when their patients have ED visits, hospital admissions, or discharges (Figure 1). The listing of patients with active event notification services is curated: subscribing organizations and providers submit listings of patients for event notification inclusion to the Bronx RHIO. Providers may continually update their subscription lists, meaning patients can cycle on and off event notification services. The event notification messages, which include only patient identity and location information, are sent to the providers as secure email or HL7 messages.

Figure 1.

Example of event notification alert (HL7 and viewed within a provider’s EHR) sent by the Bronx Regional Health Information Exchange

Survey sample

Of the 11 health care organizations that were active subscribers to the event notification system in the spring of 2015, 10 agreed to participate in our survey. Working through contact individuals provided by the Bronx RHIO, we obtained the names and contact information for any employees or providers who received event notifications as part of their job, responded to event notifications as part of their job, managed other staff who responded to event notifications, or were responsible for developing the organization’s policies and procedures around event notification. This resulted in a sample of 55 potential respondents.

The 10 surveyed organizations represented different potential use cases for alert notification systems. Those with a population health focus included a Medicare Accountable Care Organization (ACO) and a Medicaid health home. These 2 organizations are similar in that they are collaborations of multiple providers intending to manage the health of publicly insured populations. A second set of 4 organizations (a health center, 2 ambulatory care practices, and the outpatient clinic of a health system) were mainly primary care providers. Two of the remaining organizations delivered integrated services for a specific at-risk population (such as combining health services with programs and resources to address broader social, behavioral, and economic needs). The last 2 organizations were home health agencies supporting care coordination and patient management activities. At the time of survey administration, organizations averaged 18 months of experience with the event notification system (maximum = 44, minimum = 7). On average, organizations had subscribed to 2440 patients a month. However, there was a great deal of variation. The population health focus agencies maintained notification subscriptions on many thousands of individuals, and at the other end of the spectrum the outpatient clinic of the health system averaged fewer than a dozen subscribed patients a month.

Questionnaire

To construct the questionnaire, we adopted and adapted items from existing instruments that measured usage and perceptions of notifications of test results,21 electronic messaging with patients,22 and automated drug alerts.23 Conceptually and operationally, these technologies are similar to event notification systems, as each introduces new information to the user in order to prompt an action. We also identified relevant questions on usage, quality, organizational characteristics, and user perceptions from the health services research, information systems, and management information systems literature.24–28 Item wording and language were adjusted based on pilot interviews about the usage of event notification services at 2 sites.

The 41-item questionnaire (see Appendix) covered the areas of organizational capabilities (eg, existence of policies and procedures, technical resources, staff attitudes, and staff capacity); notification information quality (eg, information relevancy, completeness, accuracy, and usability); perceived usage; perceived impact (ie, care quality, organizational efficiency, and patient satisfaction); and organizational and respondent characteristics (eg, staffing, services, and job titles). Questions about perceptions utilized 7-point Likert-type responses ranging from “strongly disagree” or “never” to “strongly agree” or “always.” We piloted the questionnaire with a case manager and a physician executive for length, content, and comprehension.

Data collection

Surveys were administered online and individual informed consent was obtained from each respondent. Respondents were provided a financial incentive to complete the survey. Intentionally, we recruited multiple respondents per site. To provide additional details and clarity on work processes, we conducted short follow-up telephone interviews with representatives from 4 organizations (2 that had highly favorable views and 2 that had less favorable views of event notifications). The study was approved by the Weill Cornell Institutional Review Board.

Analysis

We described respondents’ and organizational characteristics using frequencies and percents. For perceptions measured with Likert-type items, we reported categorized distributions (disagree/never, neutral/sometimes, agree/always). Furthermore, because we created our instrument to reflect specific domains a priori, we took respondents’ average scores across the respective items (with values for reverse scored items adjusted accordingly) to create an individual domain summary score for use in regression models: organizational policies and procedures, staff support/attitudes, staff capacity, and event notification information quality. To check the robustness of these a priori domains, we computed the Cronbach’s alpha within each domain and performed an exploratory factor analysis to see whether the items loaded on the expected domains. The alphas for each domain ranged from 0.79 to 0.93, and the rotated factor analysis was also supportive of the 4 domains (details not reported).

We measured the bivariate associations between the perceived impact of event notifications and individual and organizational characteristics using random-intercept logistic regression models.29 The 3 dependent variables (care quality, organizational efficiency, and patient satisfaction) were modeled individually. Due to highly skewed responses, we divided each into high agreement (responses of 6 or 7) versus all other values. For each model, the respondents’ organization was entered as random intercept in order to account for the clustered nature of responses (ie, multiple survey respondents per organization). Because the sample size did not permit modeling of each type of organization, we focused on the groupings of population health, integrated services, and all other organizations. Regression coefficients were exponentiated to express odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

RESULTS

The overall survey response rate was 89.1% (n = 49) and the completion rate was 78.2% (n = 43). All health care organizations were represented by at least 2 different respondents (mean = 4.9). Two respondents were excluded because their practice had subscribed to an event notification service from the RHIO but had not yet begun using it in their clinic. As a result, these respondents had no experience with event notification.

Most survey respondents (59.6%) had managerial or administrative jobs (Table 1). These individuals had titles such as director, program supervisor, vice president, clinical manager, medical director, and chief medical informatics officer. Job titles that implied direct patient engagement, such as care manager and coordinator, were less common. A minority of survey respondents were clinicians (31.9%). In terms of organizations, most respondents worked for a health home (34.0%), followed closely by integrated service organizations (31.9%).

Table 1.

Characteristics (organizational and individual) of health care organizations and professionals subscribing to event notifications services

| Characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Respondents | |

| Clinician (physician, nurse, or physician assistant) | 15 (31.9) |

| Job type | |

| Patient engagement | 13 (27.7) |

| Managerial/administration | 28 (59.6) |

| Age | |

| <30 | 4 (8.5) |

| 30–40 | 12 (25.5) |

| 40–50 | 9 (19.1) |

| 50–60 | 11 (23.4) |

| >60 | 3 (6.4) |

| Organizational | |

| Type | |

| Accountable care organization | 3 (6.4) |

| Health home | 16 (34.0) |

| Health system outpatient practice | 3 (6.4) |

| Ambulatory care practice | 2 (4.3) |

| Health center | 2 (4.3) |

| Integrated services | 15 (31.9) |

| Home health | 6 (12.8) |

| Organization has … | |

| Care managers | 40 (85.1) |

| Social workers | 39 (83.0) |

| Patient navigators | 34 (72.3) |

| Health coaches | 24 (51.1) |

| Notification services | |

| Type of notifications organization receives …a | |

| Any clinical event | 9 (19.2) |

| Emergency department encounters | 33 (70.2) |

| Inpatient admissions | 28 (59.6) |

| All patients | 19 (40.4) |

| High utilizers | 9 (19.2) |

| Patients with chronic conditions | 9 (19.2) |

| Home health patients | 17 (36.2) |

| Behavioral health patients | 5 (10.6) |

| Geriatric patients | 4 (8.5) |

| Children/adolescents | 0 (0.0) |

| Alerts delivered via EHR | |

| Yes | 23 (48.9) |

| No | 10 (21.3) |

| Don’t know | 13 (27.7) |

| Person primarily responsible for event notifications | |

| Primary medical provider (eg, MD/DO/NP) | 4 (8.5) |

| Midlevel providers (eg, PA) | 2 (4.3) |

| Nursing staff (RN/LPN) | 6 (12.8) |

| Other office staff | 30 (63.8) |

| Nobody specific | 2 (4.3) |

| Technical support contact within the organization to help with event notifications | 30 (63.8) |

aCategories are not mutually exclusive.

Most commonly, respondents reported receiving event notifications for ED (70.2%) and inpatient admissions (59.6%). Approximately half of respondents (48.9%) reported that event notifications were delivered directly to their organization’s EHR. However, more than a quarter (27.7%) were unaware of how the RHIO notified their organization.

Perceptions of event notifications

Respondents indicated that organizations generally attempted to act on event notifications quickly, had the capacity to respond, and had positive attitudes toward the role of event notifications (Table 2). Specifically, respondents reported that their organizations generally attempted to act on hospitalization notifications while the patient was still in the hospital (59.6% always) or within 1–2 days of discharge (72.3% always). For ED event notification, respondent approaches were similar. Follow-up interviews indicated that acting on event notification information was a multistep process, often involving more than 1 individual (eg, 1 person got and screened the notifications while another person or team was responsible for contacting the individuals). Activities varied, usually depending on the known clinical situation of the patient. The informants might try to reach the patient while admitted to the hospital or the ED (although reaching patients in the ED could be a challenge; as one individual noted, “usually by the time you get to the emergency room, people are gone”). For other types of patients, it was often considered more useful to telephone the patient after discharge to obtain information or schedule a follow-up visit.

Table 2.

Health care professionals’ perceptions of event notification services and their organization’s capacity to respond to event notifications, Bronx Regional Health Information Organization 2015

| Domain/Item | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Policies and procedures | Disagreea | Neutrala | Agreea |

| Before the Bronx RHIO subscription alerts were implemented, we had effective procedures to find out when our patients were admitted to the ED or the hospital. | 23 (48.9) | 12 (25.5) | 8 (19.1) |

| Our organization has effective written policies and procedures for responding to Bronx RHIO subscription alerts. | 6 (12.8) | 12 (25.5) | 25 (53.2) |

| Our organization has effective policies and procedures in place to respond to Bronx RHIO subscription alerts arriving after normal business hours. | 16 (34.0) | 10 (21.3) | 17 (36.2) |

| If we receive an alert that a subscribed patient is at the ED, we: | Neverb | Sometimesb | Alwaysb |

| Try to contact the ED while the patient is in the ED. | 10 (21.3) | 7 (14.9) | 25 (53.2) |

| Try to contact the patient within 1–2 days of the ED visit. | 4 (8.5) | 5 (10.6) | 32 (68.1) |

| Discuss with patient at their next visit. | 9 (19.1) | 1 (2.1) | 31 (66.0) |

| Try to contact patient’s primary care provider (if not part of our organization) about ED visit. | 6 (12.8) | 7 (14.9) | 26 (55.3) |

| Do not respond to alerts about ED visits. (R) | 33 (70.2) | 1 (2.1) | 5 (10.6) |

| If we receive an alert that a subscribed patient has been admitted to the hospital, we: | |||

| Try to contact the hospital while patient is in the hospital. | 4 (8.5) | 9 (19.1) | 28 (59.6) |

| Try to contact the patient within 1–2 days of the hospital visit. | 2 (4.3) | 5 (10.6) | 34 (72.3) |

| Discuss with patient at their next visit. | 4 (8.5) | 4 (8.5) | 31 (66.0) |

| Try to contact patient’s primary care provider (if not part of our organization) about the admission. | 1 (6.4) | 6 (12.8) | 28 (59.6) |

| Do not respond to alerts about inpatient admissions. (R) | 32 (68.1) | 4 (8.5) | 3 (6.4) |

| Our organization has a specific staff member whose job is to follow up on patients in response to Bronx RHIO subscription alerts. | 6 (12.8) | 9 (19.1) | 28 (59.6) |

| If the patient’s primary (responsible) provider is not available, subscription alerts always go to the covering provider. | 6 (12.8) | 17 (36.2) | 18 (38.3) |

| Staff capacity | Disagreea | Neutrala | Agreea |

| The number of alerts our organization receives exceeds what we can effectively manage. (R) | 32 (68.1) | 10 (21.3) | 1 (2.1) |

| We receive too many to easily focus on most important ones. (R) | 34 (72.3) | 9 (19.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Staff support/attitudes | |||

| The administrative staff in our organization believe subscription alerts help them get their job done effectively. | 6 (12.8) | 12 (25.5) | 24 (51.1) |

| The clinical staff in our organization believe subscription alerts are an essential component of high-quality care. | 6 (12.8) | 11 (23.4) | 24 (51.1) |

| The leaders in our organization have emphasized the importance of subscription alerts in high-quality care. | 6 (12.8) | 6 (12.8) | 20 (63.8) |

| Event notification information quality | |||

| Subscription alerts are clinical useful. | 3 (6.3) | 5 (10.6) | 24 (72.3) |

| Subscription alerts identify patients' hospitalizations that our organization was not aware of. | 2 (4.3) | 6 (12.8) | 24 (72.3) |

| Subscription alerts identify patients' ED visits that our organization was not aware of. | 1 (2.1) | 6 (12.8) | 35 (74.5) |

| As a result of subscription alerts, we have identified clinical conditions we did not realize patients had. | 5 (10.6) | 14 (29.8) | 23 (48.9) |

| As a result of subscription alerts, we have identified patients that are high utilizers of medical services. | 2 (4.3) | 12 (25.5) | 28 (59.6) |

| It likely that a patient’s care will be changed due to our receipt of a Bronx RHIO subscription alert. | 6 (12.8) | 13 (27.7) | 23 (48.9) |

| Subscription alerts do not provide enough information. (R) | 17 (36.2) | 18 (38.3) | 7 (14.9) |

| We often receive subscription alerts for patients that are not ours. (R) | 27 (57.4) | 14 (29.8) | 1 (2.1) |

| The information received from the subscription alerts is clear and understandable. | 3 (6.4) | 8 (17.0) | 31 (66.0) |

aOn a 7-point scale: 1, 2, 3 = Disagree; 4 = Neutral; 5, 6, 7 = Agree bOn a 7-point scale: 1, 2, 3 = Never; 4 = Sometimes; 5, 6, 7 = Always (R) = Reverse scored for analysis

In terms of capacity to respond, respondents generally disagreed that they received too many event notifications (72.3%), or that they could not focus on important events (68.1%). However, respondents’ perceptions about the organizations’ use of effective written policies and procedures around event notifications ranged from somewhat to generally favorable. Notably, respondents indicated that their organizations had not had effective procedures for identifying patients’ emergency visits and admissions prior to the implementation of the event notification system. Finally, the perception was that clinical staff, administrative staff, and organizational leadership tended to view event notification services as important. For all 3 categories, more than half of respondents agreed with those assessments.

Respondents’ perceptions about the quality and impact of event notifications were generally favorable (Table 2). Respondents indicated that event notifications tended to be relevant (eg, high scores on the “clinically useful,” “patients’ hospitalizations that our organization was not aware of,” and “identified clinical conditions” questions); usable (high scores on the “clear and understandable” question); and accurate (low scores on the “patients that are not ours” question). Perceptions of information completeness (ie, “do not provide enough information”) tended to be a bit less favorable.

Perceived impact and usage

Respondents generally agreed that event notification improved the quality of health care, the organization’s efficiency, and patient satisfaction. The vast majority (66.0%) agreed with the statement that event notifications “have improved our ability to provide high quality of care.” Likewise, 68.1% agreed that event notifications “have improved our efficiency.” Fewer respondents, 51.1%, agreed that event notifications “have improved patient satisfaction.”

The goals of organizations and providers subscribing to notification services included improved care coordination, reduced readmissions, fewer emergency room visits, and better discharge planning. One interviewee offered an example of how the event notification service allowed case managers to improve care: “We have a 78-year-old Latino Cuban gentleman who has been in New York, moved here from Cuba years ago. And his form of medical care has always been, ‘I don’t feel good; I go to the hospital.’ He was constantly in and out of the hospital. … He was admitted via ambulance to a local hospital, spent maybe 10 days in the hospital, which allowed the case manager to begin to work with not only the client, the social worker in the hospital, and a family member so that we were all on the same page as to how to work with this client so that he would get to the doctor. … We went through maybe January/February where he was in the hospital every other week. He hasn't had a hospitalization since March.” Likewise, a physician recounted how event notifications were very useful for managing the care of a high-utilizing patient: “I have a patient who has brain damage from an accident, but he cannot remember anything that anyone tells him, and he's really bad about telling people. … So now when he shows up in the emergency room with belly pain or a sore throat, which he repetitively does, I can talk to the doctor and say, ‘You know, I know this man very well. What's going on with him? If he's stable and everything's okay, just have him see me tomorrow, and I will make sure that everything is okay.’ I've done that a couple of times.” A home health agency reported that event notifications helped home health nurses avoid needless trips to patients’ homes. Being aware that a patient had been admitted to the hospital, and therefore wouldn’t be at home for a scheduled visit, was a simple and important gain in organizational efficiency, as time and effort can be redirected toward other patients.

Respondents estimated that their organizations followed up on the majority of event notifications (mean = 83%, median = 90%, range 25–100%). More than half of respondents (56%) reported that an event notification had prompted them to look up additional information in the Bronx RHIO’s query-based HIE system. The query-based HIE system fit into the workflow by identifying which provider to contact at the admitting hospital. A physician described the efficiencies created by the interaction of the event notification system and the query-based HIE like this: “When somebody is admitted to another hospital, it can be very difficult to figure out who to talk to. … [The Bronx RHIO] allows me to see who wrote what notes. I can actually call the nurse or I can call the doctor, whoever wrote the notes, and it's just so much more efficient than trying to go through a hospital operator.”

Association with perceived impact

The organizational policy and procedure score and the information quality score were the only factors significantly associated with all 3 outcome measures (Table 3). Specifically, having organizational policies that supported alert response was associated with the perception that event notifications improve quality of care (OR = 2.12; 95% CI = 1.05, 4.45), efficiency (OR = 2.06; 95% CI = 1.00, 4.21), and patient satisfaction (OR = 2.56; 95% CI = 1.13, 5.81). Likewise, respondents who reported that event notifications had high information quality were more likely to perceive a positive impact on quality of care (OR = 2.84; 95% CI = 1.31, 6.12), efficiency (OR = 3.04; 95% CI = 1.38, 6.69), and patient satisfaction (OR = 2.96; 95% CI = 1.25, 7.03).

Table 3.

Unadjusted associations between perceived organizational characteristics and perceived impact of event notification services

| “Event notifications … | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | have improved our ability to provide high quality of care” | have improved our efficiency” | have improved patient satisfaction” |

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | Odds ratio (95% CI) | Odds ratio (95% CI) | |

| Respondent | |||

| Clinician (physician, nurse, or physician assistant) | 0.48 (0.89, 2.64) | 0.71 (0.15, 3.38) | 1.49 (0.41, 5.35) |

| Patient engagement job role | 1.75 (0.32, 9.66) | 4.00 (0.73, 21.83) | 5.71 (1.30, 25.02)* |

| Organization | |||

| Organizational focus | |||

| Population healtha | 4.89 (0.93, 25.67) | 6.40 (1.18, 34.61)* | 4.00 (0.66, 24.29) |

| Integrated services | 34.60 (3.05, 391.96)** | 16.00 (2.16, 118.26)** | 4.50 (0.70, 28.79) |

| All others | (reference) | (reference) | (reference) |

| Alerts delivered via EHR | 2.43 (0.42, 14.14) | 3.30 (0.52, 20.92) | 2.75 (0.77, 9.86) |

| Technical support contact within organization | 1.51 (0.30, 7.46) | 2.48 (0.50, 12.22) | 1.83 (0.46, 7.31) |

| Office staff primarily responsible for event notifications | 7.33 (1.63, 32.91)** | 4.20 (1.00, 17.58)* | 3.00 (0.67, 13.47) |

| Organizational policy and procedures score | 2.12 (1.05, 4.45)* | 2.06 (1.00, 4.21)* | 3.48 (1.30, 9.36)* |

| Staff support/attitude score | 1.40 (0.93, 2.12) | 1.36 (0.90, 2.05) | 1.16 (0.77, 1.74) |

| Staff capacity score | 1.03 (0.67, 1.85) | 1.06 (0.60, 1.89) | 1.12 (0.68, 1.86) |

| Event notification information quality score | 2.84 (1.31, 6.12)** | 3.04 (1.38, 6.69)** | 2.96 (1.25, 7.03)* |

*P < .05

**P < .01aIncludes respondents within a health home and accountable care organization

Also associated with greater perceived positive impact on quality of care and efficiency were (1) reporting that office staff (not clinical staff) were primarily responsible for receiving and reviewing event notifications, and (2) being employed by an organization that provided integrated services (Table 3). Notably, working in an organization with a population health focus (like a health home or ACO) was also associated with higher likelihood of reporting that event notifications had a positive impact on efficiency. Finally, compared to those with managerial or administrative jobs, respondents involved in direct patient engagement activities were significantly more likely to report that event notifications improved patient satisfaction.

DISCUSSION

This study sought to examine the association between perceived organizational capabilities and responses to event notification services. Based on responses from a diverse set of health care professionals, we conclude that an event notification service is more likely to be seen as improving care quality, organizational efficiency, and patient satisfaction by users whose organizations had policies and procedures that support responding to alerts. We also found that the perceived information quality of the event notifications was associated with a positive perceived impact on quality, efficiency, and patient satisfaction. These findings suggest practical guidance to those health information organizations offering event notification services and leaders of health care organization seeking to utilize these types of services in support of operational and clinical goals.

Consistent with a sociotechnical perspective, these findings suggest that organizations that establish workflows, processes, policies, and culture to effectively use information are better positioned to have health information technology projects succeed.30,31 Overall, this concept was reflected in the association between an increased policy and procedure score and perceived impact. However, the concept underlies other associations observed in the data. For example, using office staff (not clinically licensed staff) to manage event notifications suggests procedures that may better align with use of event notifications, because neither understanding the content of event notifications (which contained no clinical information) nor contacting facilities to locate patients requires clinical expertise. In fact, qualitative interviews with nonclinical staff at health homes have indicated that these types of information are among the most important to their jobs.32,33 Likewise, the higher perceived impact for ACOs, health homes, and integrated service delivery organizations likely reflect those organizations’ dedication of resources and effort to managing patient care across multiple settings.34,35 Increased awareness about patient care in other settings addresses a serious limitation facing health care organizations seeking to coordinate care.36

At the same time, this study also is a reminder that information quality remains critical in users’ assessments and perceptions. Information (or data) quality is a driver of information system usage in general.37 The consistent association between information quality and perceived impact is all the more striking considering the Bronx RHIO’s event notification system is a minimal information intervention. Only a few data elements are shared (patient names and location information). Regardless of how “basic” these types of data may be, if any organization offering event notification services hopes to have satisfied users, priority must be given to assuring timely notification about the right patient to the correct provider. Other studies have indicated that providers find being notified electronically about patient discharges useful,6,9–12,38,39 but this study illustrates the relationship between perceived impact and perceived information quality.

The varying organizational capabilities and importance of information quality may help explain the inconsistent literature on the impact of event notification systems. For example, quantitative evaluations of event notifications sent to primary care practices have found no effect on readmissions and repeat ED visits.10,40 In contrast, 1 evaluation of event notifications for HIV patients suggested that the service improved re-engagement with care services and clinical indicators.41 In the more favorable study, event notifications contained specific clinical information for a key patient population and were integrated into the EHRs of providers practicing in an integrated delivery system. The fact that the findings of our survey contrast with the existing literature suggests that those seeking to leverage event notification technology need to establish definitive processes for managing information, have the capability to respond to alerts, and ensure high information quality.

Limitations

This study is based on a small sample of respondents from a limited number of health care organizations that have implemented 1 event notification service, which resulted in several limitations. The small sample size, which is reflected in the wide confidence intervals around the parameter estimates, would not support multivariate analyses or stratification by key variables such as organizational size or clinical role. The generalizability of findings is also limited in terms of the event notification system (other systems may contain different information from a different array of providers), the respondents (all were self-selected system adopters), and the location (an urban area in a state with strong policy support for health information exchange). Importantly, with this cross-sectional design, we cannot establish causality or temporal sequence. We do not know if it was the presence of organizational capabilities that drove perceived effectiveness, or if the perception of event notification effectiveness drove the organizational policy development. In fact, it may not be possible to determine whether one caused the other, as a sociotechnical perspective suggests instead that the technology and the organization mutually transformed each other.30,31 Also, it is possible that unmeasured experiences with other systems influenced perceptions. For example, interviews indicated that more than 1 event notification system was in use in at least 1 organization: the Bronx RHIO’s event notification system and the internal system used for notifying the ACO of admissions to their own hospital. Lastly, our survey items, while adapted from existing instruments, measured respondents’ perceptions only. As a result, activities that constituted following up on a patient or how the organization’s efficiency improved were open to the respondents’ interpretations.

Conclusion

Event notification services are intended to address the information and communication challenges resulting from fragmented care. Health care organizations with appropriate processes, workflows, and staff may be better positioned to use this technology to improve patient care. At the same time, information quality remains critical in users’ assessments and perceptions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This project was made possible with funding from the New York State Department of Health and the assistance of the New York eHealth Collaborative, the Bronx RHIO, Cornell Survey Research Institute, and Baria Hafeez, MS.

CONTRIBUTOR

JV and JA conceived, designed, and implemented the study. JV and JA analyzed the data and wrote the final manuscript.

FUNDING

The work was supported by the New York State Department of Health (contract number 14-HITEC-01).

COMPETING INTEREST

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bourgeois FC, Olson KL, Mandl KD. Patients treated at multiple acute health care facilities: quantifying information fragmentation. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:1989–1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kripalani S, LeFevre F, Phillips CO, et al. Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital-based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care. JAMA. 2007;297: 831–841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Roberts RO, Bergstralh EJ, Schmidt L, et al. Comparison of self-reported and medical record health care utilization measures. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49:989–995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wallihan DB, Stump TE, Callahan CM. Accuracy of self-reported health services use and patterns of care among urban older adults. Med Care. 1999;37:662–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ancker JS, Witteman HO, Hafeez B, et al. The invisible work of personal health information management among people with multiple chronic conditions: qualitative interview study among patients and providers. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17:e137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gutteridge DL, Genes N, Hwang U, et al. Enhancing a Geriatric Emergency Department Care Coordination Intervention using automated health information exchange-based clinical event notifications. EGEMS. 2014;2:1095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Moore T, Shapiro JS, Doles L, et al. Event detection: a clinical notification service on a health information exchange platform. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2012;2012:635–642. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. The Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. Improving Hospital Transitions and Care Coordination Using Automated Admission, Discharge and Transfer Alerts: a Learning Guide. 2013. https://www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/onc-beacon-lg1-adt-alerts-for-toc-and-care-coord.pdf.

- 9. Altman R, Shapiro JS, Moore T, et al. Notifications of hospital events to outpatient clinicians using health information exchange: a post-implementation survey. Inform Prim Care. 2012;20:2492–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lang E, Afilalo M, Vandal AC, et al. Impact of an electronic link between the emergency department and family physicians: a randomized controlled trial. CMAJ. 2006;174:313–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Anand V, Sheley ME, Xu S, et al. Real time alert system: a disease management system leveraging health information exchange. Online J Public Health Inform. 2012;4:ojphi.v4i3.4303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Trudnak T, Mansour M, Mandel K, et al. A case study of pediatric asthma alerts from the beacon community program in cincinnati: technology is just the first step. EGEMS. 2014;2:1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ulrich D, Lake DG. Organizational Capability: Competing from the Inside Out. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Collis DJ. Research note: how valuable are organizational capabilities? Strateg Manag J. 1994;15:143–152. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Herwehe J, Wilbright W, Abrams A, et al. Implementation of an innovative, integrated electronic medical record (EMR) and public health information exchange for HIV/AIDS. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2012;19:448–452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Berg M. Patient care information systems and health care work: a sociotechnical approach. Int J Med Inform. 1999;55:87–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Berg M. Implementing information systems in health care organizations: myths and challenges. Int J Med Inform. 2001;64:143–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Heeks R. Health information systems: failure, success and improvisation. Int J Med Inform. 2006;75:125–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ancker JS, Kern LM, Abramson E, et al. The Triangle Model for evaluating the effect of health information technology on healthcare quality and safety. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2012;19:61–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. BronxRHIO. For Providers. 2014. https://www.bronxrhio.org/for-providers. Accessed on 8 January, 2015.

- 21. Singh H, Spitzmueller C, Petersen NJ, et al. Primary care practitioners’ views on test result management in EHR-enabled health systems: a national survey. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2013;20:727–735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kittler AF, Carlson GL, Harris C, et al. Primary care physician attitudes towards using a secure web-based portal designed to facilitate electronic communication with patients. Inf Prim Care. 2004;12:129–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Glassman PA, Belperio P, Simon B, et al. Exposure to automated drug alerts over time: effects on clinicians’ knowledge and perceptions. Med Care. 2006;44:250–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Venkatesh V, Morris MG, Davis GB, et al. User acceptance of information technology: toward a unified view. MIS Q. 2003;27:425–478. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lee YW, Strong DM, Kahn BK, et al. AIMQ: a methodology for information quality assessment. Inf Manag. 2002;40:133–146. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wang CJ, Patel MH, Schueth AJ, et al. Perceptions of standards-based electronic prescribing systems as implemented in outpatient primary care: a physician survey. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2009;16:493–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rittenhouse DR, Casalino LP, Gillies RR, et al. Measuring the medical home infrastructure in large medical groups. Health Aff. 2008;27:1246–1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rittenhouse DR, Casalino LP, Shortell SM, et al. Small and medium-size physician practices use few patient-centered medical home processes. Health Aff. 2011;30:1575–1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rabe-Hesketh S, Skrondal A. Multilevel and Longitudinal Modeling Using Stata. 2nd ed. College Station, TX: Stata Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Aarts J, Doorewaard H, Berg M. Understanding implementation: the case of a computerized physician order entry system in a large dutch university medical center. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2004;11:207–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Berg M, Aarts J, van der Lei J. ICT in health care: sociotechnical approaches. Methods Arch. 2003;42:297–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kierkegaard P, Kaushal R, Vest JR. How could health information exchange better meet the needs of care practitioners? Appl Clin Inform. 2014;5: 861–877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Richardson JE, Vest JR, Green CM, et al. A needs assessment of health information technology for improving care coordination in three leading patient-centered medical homes. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2015;22:815–820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Taylor EF, Machta RM, Meyers DS, et al. Enhancing the primary care team to provide redesigned care: the roles of practice facilitators and care managers. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11:80–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Burns LR, Pauly MV. Accountable care organizations may have difficulty avoiding the failures of integrated delivery networks of the 1990s. Health Aff. 2012;31:2407–2416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Emanuel E. Why accountable care organizations are not 1990s managed care redux. JAMA. 2012;307:2263–2264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. DeLone WH, McLean ER. The DeLone and McLean Model of information systems success: a ten-year update. J Manag Inf Syst. 2003;19:9–30. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Afilalo M, Lang E, Léger R, et al. Impact of a standardized communication system on continuity of care between family physicians and the emergency department. CJEM. 2007;9:79–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hunchak C, Tannenbaum D, Roberts M, et al. Closing the circle of care: implementation of a web-based communication tool to improve emergency department discharge communication with family physicians. CJEM. 2015;17:123–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gurwitz JH, Field TS, Ogarek J, et al. An electronic health record–based intervention to increase follow-up office visits and decrease rehospitalization in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62: 865–871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Magnus M, Herwehe J, Gruber D, et al. Improved HIV-related outcomes associated with implementation of a novel public health information exchange. Int J Med Inform. 2012;81:e30–e38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]