Abstract

Computer-aided learning (CAL) offers enormous potential in disseminating oral health care information to patients and caregivers. The effectiveness of CAL, however, remains unclear.

Objectives: The purpose of this study was to systematically review published evidence on the effectiveness of CAL in disseminating oral health care information to patients and caregivers.

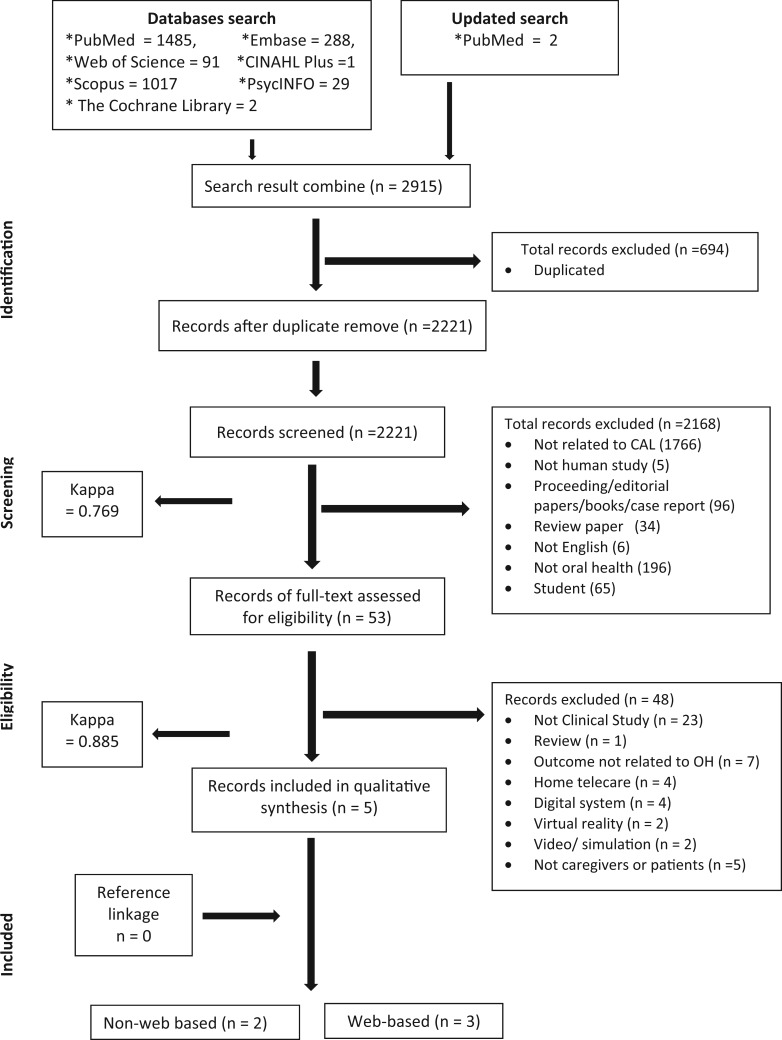

Materials and Methods: A structured comprehensive search was undertaken among 7 electronic databases (PUBMED, CINAHL Plus, EMBASE, SCOPUS, WEB of SCIENCE, the Cochrane Library, and PsycINFO) to identify relevant studies. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and observational studies were included in this review. Papers were screened by 2 independent reviewers, and studies that met the inclusion criteria were selected for further assessment.

Results: A total of 2915 papers were screened, and full texts of 53 potentially relevant papers (κ = 0.885) were retrieved. A total of 5 studies that met the inclusion criteria (1 RCT, 1 quasi-experimental study, and 3 post-intervention studies) were identified. Outcome measures included knowledge, attitude, behavior, and oral health. Significant improvements in clinical oral health parameters (P < .05) and knowledge/attitudes (P < .001) were reported in 2 of the studies. The 3 remaining studies reported improved oral health behaviors and confidence.

Conclusion: There is a limited number of studies which have examined the effectiveness of CAL interventions for oral health care among patients and caregivers. Synthesis of the data suggests that CAL has positive impacts on knowledge, attitude, behavior, and oral health. Further high- quality studies on the effectiveness of CAL in promoting oral health are warranted.

Keywords: computer-aided learning, oral health care, patients, caregivers

INTRODUCTION

Disseminating oral self-care information to patients and caregivers is key in preventing oral diseases and maintaining oral health.1,2 While one-on-one instruction offers the potential to address individual patients’ needs, build rapport with patients, and tailor oral health information and required counseling, there are cost-effectiveness concerns.3 To this end, there has been widespread dissemination of oral health education through pamphlets, brochures, and mass media campaigns, but with questionable evidence of their effectiveness.4 More recently, with advances in computer technology the dissemination of oral health information and oral health promotion has become feasible.5 Typically this is referred to as computer-aided learning (CAL), “any learning that is mediated by a computer and which requires no direct interaction between the user and a human instructor in order to run.”6 The process has been referred to as computer- assisted learning (CAL),6 computer-based instruction (CBI), and computer-aided instruction (CAI).7

CAL has been used in a wide variety of modes for patient education and counseling.8 Earlier CAL programs mainly involved a “one-way” delivery of educational content to users.9 More recently, however, CAL has been enhanced with audio and video components, and has also incorporated more interactive elements such as feedback, discussions, forums, and quizzes.10–12 Self-assessment for CAL has also been introduced and is one of the ways users can assess their own performance, and this has been shown to enhance users’ knowledge, attitude, skills, and behavior. With the widespread availability of computers and associated digital technology, CAL offers opportunities for greater accessibility and more affordable oral health education and counseling.13

In the dental arena, CAL has been widely adopted as a means of communication and collaboration among dental practitioners to enhance dental care and services.14,15 CAL is an established pedagogy for the education of dental practitioners and dental students, and an integral part of distance learning.11,16–18 To date, studies relating to the use of CAL in dentistry have focused on the enhancement of knowledge in patient management and decision making.19 The effectiveness of CAL and the extent to which it is used in patient and caregiver education remain unclear.

To our knowledge, no reviews have been conducted on CAL related to oral health among patients or caregivers. There has been an increasing interest in computer-assisted patient education, and this is reflected by a general increase in the number of studies included in prior reviews. For example, Krishna et al.20 reported 13 studies up to 1994, while Lewis21 reported 21 studies up to 199822 and 32 studies up to 2001 in an updated review. While fewer studies (26) have been reported in more recent reviews23 and 25 studies reported from January 2001 to January 2008,24 this was related to searches limited to randomized clinical trial studies23 and studies pertaining to the impact of CAL on clinical and economic outcomes. These prior studies demonstrated the use of CAL in a variety of formats (eg, CD-ROMs, multimedia, Internet) across a wide spectrum of health care settings. The implementation of computer-assisted patient education has resulted in improvements in knowledge, attitude, clinical outcomes, and other measures such as behavior. Despite the large number of studies investigating computer patient education in the general health care setting, the number of studies on CAL related to oral health retrieved for the present review was limited.

Thus, the objective of this systematic review was to evaluate the current evidence for the effectiveness of CAL in the dissemination of oral care information and education to patients and caregivers.

Methodology

Search strategy

An electronic database search was undertaken using PUBMED (1950 to October 2014), CINAHL (1937 to October 2014), EMBASE (1947 to October 2014), SCOPUS (1960 to October 2014), PsycINFO (1970 to October 2014), the Cochrane Library (1997 to October 2014), and WEB of SCIENCE (1956 to October 2014). The search had no date limit and was solely based on the indexing databases available at the University of Hong Kong library. The search terms used in this review were based on systematic reviews on “oral health,” “patient’s education,” and “computer based education programs”23–26 and used the following keywords: computer system OR computer based OR computer assisted OR computer AND dental health education OR health promotion OR oral health OR dental hygiene OR preventive dentistry OR mouth diseases OR tooth injuries OR gum shields OR oral cancer OR toothpaste OR mouth rinse OR floss OR varnish OR antimicrobial agent OR atraumatic restorative treatment OR plaque control OR behavior training AND caregivers OR patient education. Search results were updated until July 2015. Relevant articles from reference lists were manually searched for potential papers that met inclusion criteria.

Screening and selection

Potentially relevant papers were screened independently by 2 reviewers (N.A.M., J.Z.). Studies that covered CAL and oral health were all included. The searches were not limited to the clinical oral health outcomes, but also included changes in behavior, attitudes, and knowledge regarding oral health. Duplicate papers were retrieved from the 7 databases and were removed. Titles were screened and grouped accordingly. If there was any uncertainty in the title, the abstract was read and assessed. Disagreement between reviewers was resolved through discussion, and consensus was reached with a third reviewer (O.L.). The inclusion criteria were studies incorporating the use of CAL (non-Web-based and Web-based) for oral health care learning activities, and targeted at either caregivers or patients or both. Studies of the following design were included: RCTs, case-control studies, cohort studies, and cross-sectional studies. Only studies written in the English language were selected.

Full texts of the potentially relevant papers were retrieved, read, and approved by 2 independent reviewers (N.A.M., J.Z.). Consensus was reached through discussion between reviewers. Observational studies and clinical trials were evaluated using STROBE criteria and CONSORT criteria, respectively.

Assessment of study heterogeneity

The assessment of study heterogeneity for data extraction was based on the following factors:

Study design

CAL characteristics

Outcome measure

Results

Searches of all the databases identified 2915 papers. Duplicate studies (n = 694) between the databases were removed. A total of 2221 papers were then screened by the 2 independent reviewers (κ = 0.769), and 2168 papers were excluded due to unmet inclusion criteria. Full texts of 53 potential papers were retrieved, and were screened by the 2 independent reviewers (κ = 0.885). Five papers that met the inclusion criteria were selected for content evaluation, with 48 papers excluded, as they were either not clinical studies or not related to oral health, were review papers, or did not involve patients or caregivers. Studies that were performed using computers but in the form of home telecare, digital system, virtual reality, or simulation video were not included in this review. No additional studies were found through reference linkage. An overview of the study screening and selection process is summarized in Figure 1 (PRISMA flow diagram of the screened articles). Table 1 describes the details of the 5 papers that met the inclusion criteria.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of the screened articles

Table 1.

Details of reported papers

| No. | Authors, Year, Country | Study design | Clinical issues | Type of outcome measure | Sample | Instruments | Intervention | Intervention Duration | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Jerreat et al., 2007, UK | Post- intervention (P) | Inpatient denture care | Effectiveness of denture care guidelines through CAL –P3 | n = 81 nurses in general hospital | Questionnaire following the program | CAL program on denture care (following pilot 1, baseline, and pilot 2, introduce guidelines) | Not mentioned | 100% reported useful and satisfied with CAL and 98% had improved confidence |

| 2 | Matthews et al., 2001, USA | Post- intervention | Pain and anxiety of needles | Preference, attitude, and experience toward dental anesthesia | n = 97 recall patients from private clinics, n = 196 general population | Questionnaire following the information on periodontal disease and treatment choices (5-point Likert scale) | Computerized decision aid (laptop with CD-ROM) | Information and survey, 30 minutes | No significant difference between the 2 groups in preference of dental anesthesia (P = .085) but significantly associated with pain and anxiety |

| 3 | Ojima et al., 2003, Japan | RCT (P) | Periodontal health and OH | Perio health, plaque removal, and OH effectiveness of a Web-based intervention system at workplace | n = 6; test (face-to-face toothbrushing instruction and follow-up via phone and the system) n = 7; control (face-to-face toothbrushing instruction and followup via phone) workers in a company | Periodontal health assessment (perio destruction), plaque accumulation, gingival inflammation, and oral hygiene. (baseline and 3 months) | Web-based personalized intervention system: oral self-care materials, text, image, and video (view own skills) | From the second follow-up to the third months. | A significant difference in all indices between baseline and 3-month assessment (P < .05) in test group, and only plaque accumulation and oral hygiene for control group; Web more effective than conventional approach |

| 4 | Albert et al., 2014, USA | Quasi-experimental | Maternal caries transmission | Effectiveness of Web-based on knowledge, attitude, and behavior of mother/caregiver | n = 459/589 (mothers and primary caregivers) | Questionnaire pre- and post-survey (immediately after the intervention) | Internet-delivered educational intervention;after registration, pre-survey, followed by intervention and end with post-survey | No specific time mentioned for program accessed online | Significant improvement in knowledge (P < .001) and attitude (P < .001), increased behavior change |

| 5 | George et al., 2014, Australia | Post- intervention (P) | Maternal oral health | Effectiveness of online education program and midwives’ knowledge | n = 12/22 (only 12 returned feedback/knowledge) | Questionnaire; feedback form and knowledge test (at end of modules) | Online education program (modules and video) ( + hard copy, used when no Internet access) | 14-to-16-hour program 4 months online information | The Education program is useful and accessible and increased confidence in promoting oral health, help to access knowledge improvement |

Study design

All studies selected for the review utilized CAL in the form of either a Web-based (3 studies) or non-Web-based (eg, computer-based software and CD-ROM or intranet) intervention. The 2 non-Web-based studies specifically evaluated the local use of computers at specified study sites.27,28 On the other hand, the Web-based studies provided online information and did not specify the physical location where study subjects could access this information. Among the 5 papers that met the inclusion criteria, 1 study was an RCT,29 1 was a quasi- experimental study,30 and 3 were post-intervention studies.27,28,31 Three studies were conducted among caregivers (nurses, Jerreat et al.27; midwives, George et al.31; mothers/primary caregivers, Albert et al.30) and 2 studies were on non–health care providers (patients from private clinics, Matthews et al., 2001; company employees: Ojima et al.29). The sample size ranged from 6 subjects29 to 589 subjects,30 and the follow-up time ranged up to 3 months.29 Two of the studies were conducted in the United States28,29; others were in Australia, Japan, and the United Kingdom.

CAL characteristics

The specific characteristics of CAL varied widely across the 5 studies. Two studies provided a Web-based program with videos,29,31 with 1 study providing additional hard copy information as an alternative for subjects without Internet access at home.31 The Web-based videos investigated by George et al.31 were on practical skills and demonstrated the provision of oral health education, assessment, and referral by midwives. Ojima et al.29 used personalized videos containing patient- specific advice on oral care. The non-Web-based interventions used a direct access method, with laptop computers with CD-ROMs and headphones placed at specific locations in community centers.28 No further details regarding the delivery of CAL were provided by Jerreat et al.27

Learning environments for CAL programs were based on convenience sampling, and included hospitals, community centers, and offices as well as at-home usage. The timing of CAL provision varied widely across the studies. The CAL program could be viewed immediately after registration of the subjects,28,30,31 following written guidelines intervention,27 and after face-to-face toothbrushing instruction and follow-up.29

Outcome measures

One study administered questionnaires before and after provision of CAL to assess knowledge, attitude, and behavior,30 while 1 study used clinical indicators (eg, periodontal, plaque index).29 The other studies used post-intervention questionnaires to assess behavior,27 attitude,28 and knowledge.31 Jerreat et al.27 and George et al.31 also reported on the usefulness of the CAL program, and reported an improvement in the subjects’ confidence to deliver information and promote oral health to patients.

Albert et al.30 reported improvements in knowledge, attitude, and behavior with respect to maternal caries transmission after the CAL intervention. The study by Ojima et al.29 demonstrated significant improvement in clinical indicators (periodontal assessment, plaque accumulation, gingival inflammation, and oral hygiene) (P < .05) with the provision of CAL, compared to the control group at 3 months follow-up. Matthews et al.,28 however, did not observe a significant difference in the study outcome (eg, subjects’ preference for dental anesthesia) even when both groups were given an identical CAL program. The study showed that patients’ concerns about pain and anxiety have a significant effect on their preference for dental anesthesia, with no report on the effect of the CAL program used in both groups.

Reporting quality

STROBE and CONSORT assessment is detailed in Tables 2 and 3. The single RCT was further assessed for risk of bias (Table 4).

Table 2.

STROBE

| Heading | Item no. | Recommendation | Matthews et al., 2001 | Jerreat et al., 2007 | Albert et al., 2014 | George et al., 2014 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Title and abstract | 1 | (a) Indicate the study’s design with a commonly used term in the title or the abstract | – | – | – | √ |

| (b) Provide in the abstract an informative and balanced summary of what was done and what was found | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||

| Background | 2 | Explain the scientific background and rationale for the investigation being reported | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Objectives | 3 | State specific objectives, including any prespecified hypotheses | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Study design | 4 | Present key elements of study design early in the paper | – | √ | – | √ |

| Setting | 5 | Describe the setting, locations, and relevant dates, including periods of recruitment, exposure, follow-up, and data collection | √ | √ | – | √ |

| Participants | 6 | (a) Give the eligibility criteria and the sources and methods of selection of participants (*describe method of follow-up) (*cohort only) | √ | – | √ | √ |

| (b) For matched studies, give matching criteria and number of exposed and unexposed (*cohort only) | ||||||

| (c) For matched studies, give matching criteria and the number of controls per case (*case-control only) | ||||||

| Variables | 7 | Clearly define all outcomes, exposures, predictors, and potential confounders and effect modifiers; give diagnostic criteria, if applicable | – | √ | √ | √ |

| Data source/ measurement | 8* | For each variable of interest, give sources of data and details of methods of assessment (measurement); describe comparability of assessment methods if there is more than 1 group | – | – | √ | – |

| Bias | 9 | Describe any efforts to address potential sources of bias | – | – | – | – |

| Study size | 10 | Explain how the study size was arrived at | – | – | – | – |

| Quantitative variables | 11 | Explain how quantitative variables were handled in the analyses; if applicable, describe which groupings were chosen and why | – | – | – | – |

| Statistical methods | 12 | (a) Describe all statistical methods, including those used to control for confounding | – | – | √ | √ |

| (b) Describe any methods used to examine subgroups and interactions | – | – | – | – | ||

| (c) Explain how missing data were addressed | – | – | – | – | ||

| (d) If applicable, explain how loss to follow-up was addressed (*cohort) | – | – | – | – | ||

| *If applicable, describe analytical methods, taking account of sampling strategy (*cross-sectional) | ||||||

| **If applicable, explain how matching of cases and controls was addressed (*case-control studies) | ||||||

| (e) Describe any sensitivity analyses | – | – | – | – | ||

| Participants | 13* | (a) Report numbers of individuals at each stage of the study; eg, numbers potentially eligible, examined for eligibility, confirmed eligible, included in the study, completing follow-up, and analyzed | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| (b) Give reasons for non-participation at each stage | – | – | – | – | ||

| (c) Consider use of a flow diagram | – | – | – | – | ||

| Descriptive data | 14* | (a) Give characteristics of study participants (eg, demographic, clinical, social) and information on exposure and potential confounders | – | – | √ | √ |

| (b) Indicate the number of participants with missing data for each variable of interest | – | – | – | – | ||

| (c) Summarize follow-up time (average and total amount) (*cohort only) | – | |||||

| Outcome data | 15* | Report numbers of outcome events or summary measures | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| **Report numbers in each exposure category, or summary measures of exposure (*case-control) | ||||||

| Main results | 16 | (a) Give unadjusted estimates and, if applicable, confounder-adjusted estimates and their precision (eg, 95% confidence interval); make clear which confounders were adjusted for and why they were included | – | – | – | – |

| (b) Report category boundaries when continuous variables were categorized | – | – | – | – | ||

| (c) If relevant, consider translating estimates of relative risk into absolute risk for a meaningful time period | – | – | – | – | ||

| Other analyses | 17 | Report other analyses done; eg, analyses of subgroups and interactions and sensitivity analyses | – | – | – | – |

| Key results | 18 | Summarize key results with reference to study objectives | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Limitations | 19 | Discuss limitations of the study, taking into account sources of potential bias or imprecision; discuss both direction and magnitude of any potential bias | – | – | √ | √ |

| Interpretation | 20 | Give a cautious overall interpretation of results considering objectives, limitations, multiplicity of analyses, results from similar studies, and other relevant evidence | √ | – | √ | √ |

| Generalizability | 21 | Discuss the generalizability (external validity) of the study results | – | – | √ | √ |

| Funding | 22 | Give the source of funding and the role of the funders for the present study and, if applicable, for the original study on which the present article is based | – | – | √ | √ |

| 9 | 9 | 15 | 17 |

Table 3.

Consort (clinical trials)

| Heading | Item no. | Recommendation | Ojima M et al., 2003 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Title and abstract | 1 | (c) Identification as a randomized trial in the title | √ |

| (d) Structured summary of trial design, methods, results, and conclusions | √ | ||

| Background and objectives | 2 | (a) Scientific background and explanation of rationale | √ |

| (b) Specific objectives or hypotheses | √ | ||

| Trial design | 3 | (a) Description of trial design (such as parallel, factorial including allocation ratio) | – |

| (b) Important changes to methods after trial commencement (such as eligibility criteria), with reasons | – | ||

| Participants | 4 | (a) Eligibility criteria for participants | – |

| (b) Settings and locations where the data were collected | – | ||

| Interventions | 5 | (a) Interventions for each group with sufficient details to allow replication, including how and when they were administered | √ |

| Outcomes | 6 | (a) Completely defined prespecified primary and secondary outcome measures, including how and when they were assessed | √ |

| (b) Any changes to trial outcomes after the trial commenced, with reasons | – | ||

| Sample size | 7 | (a) How sample size was determined | – |

| (b) When applicable, explanation of any interim analyses and stopping guidelines | – | ||

| Sequence generation | 8 | (a) Method used to generate the random allocation sequence | – |

| (b) Type of randomization; details of any restriction (such as blocking and block size) | – | ||

| Allocation concealment mechanism | 9 | Mechanism used to implement the random allocation sequence (such as sequentially numbered containers), describing any steps taken to conceal the sequence until interventions were assigned | – |

| Implementation | 10 | Who generated the random allocation sequence, who enrolled participants, and who assigned participants to interventions | – |

| Blinding | 11 | (a) If done, who was blinded after assignment to interventions (eg, participants, care providers, those assessing outcomes) and how | – |

| (b) If relevant, description of the similarity of interventions | – | ||

| Statistical methods | 12 | (f) Statistical methods used to compare groups for primary and secondary outcomes | √ |

| (g) Methods for additional analyses, such as subgroup analyses and adjusted analyses | – | ||

| Participant flow | 13 | (a) For each group, the number of participants who were randomly assigned, received intended treatment, and were analyzed for the primary outcome | √ |

| (b) For each group, losses and exclusions after randomization, with reasons | – | ||

| Recruitment | 14 | (a) Dates defining the periods of recruitment and follow-up | √ |

| (b) Why the trial ended or was stopped | – | ||

| Baseline data | 15 | Table showing baseline demographic and clinical characteristics for each group | – |

| Numbers analyzed | 16 | For each group, number of participants (denominator) included in each analysis and whether the analysis was by original assigned groups | – |

| Outcomes and estimation | 17 | (a) For each primary and secondary outcome, results for each group and the estimated effect size and its precision (such as 95% confidence interval) | – |

| (b) For binary outcomes, presentation of both absolute and relative effect sizes is recommended | – | ||

| Ancillary analyses | 18 | Results of any other analyses performed, including subgroup analyses and adjusted analyses, distinguishing prespecified from exploratory | – |

| Harms | 19 | All important harms or unintended effects in each group | – |

| Limitations | 20 | Trial limitations, addressing sources of potential bias, imprecision, and, if relevant, multiplicity of analyses | √ |

| Generalizability | 21 | Generalizability (external validity, applicability) of the trial findings | √ |

| Interpretation | 22 | Interpretation consistent with results, balancing benefits and harms, and considering other relevant evidence | – |

| Registration | 23 | Registration number and name of trial registry | – |

| Protocol | 24 | Where the full trial protocol can be accessed, if available | – |

| Funding | 25 | Sources of funding and other support (such as supply of drugs), role of funders | – |

| 10 |

Table 4.

Risk of bias assessment

| Domain/Authors | Ojima et al., 2003 (P) | Support for judgment |

|---|---|---|

| Selection bias | ||

| Random sequence generation | Unclear risk | Insufficient information; only mentioned workers were randomized to either experimental or control group without further elaboration |

| Allocation concealment | Unclear risk | Not described in the study |

| Performance bias | ||

| Blinding of participants and personnel | Unclear risk | Did not address in the study |

| Detection bias | ||

| Blinding of outcome assessment | Unclear risk | Did not address in the study |

| Attrition bias | ||

| Incomplete outcome data | Low risk | No missing outcome data |

| Reporting bias | ||

| Selective reporting | Unclear risk | Insufficient information |

| Other bias | ||

| Other sources of bias | Unclear risk | Insufficient information |

Discussion

Web-based delivery of CAL has been widely used as an additional tool for patient education in the medical field,32 and significant impacts have been reported in both dental and medical education.5,33 Indeed, the systematic search used in this review retrieved a large number of studies detailing the use of CAL in other areas of dentistry, such as education for dental students and dental professionals. Few studies, however, were related to CAL delivery of information to patients or caregivers. The selection criteria for the type of study were not restricted to RCT, as this would have further limited the number of available studies for this review. The papers that met the inclusion criteria were found to be diverse in terms of study design, clinical setting, sample size, assessment instrument, and type of CAL intervention.

Paradoxically, while there is a lack of formal study on CAL, this method of patient and caregiver education appears to have wide practical usage in dental practices.23 Manufacturers such as Colgate and Oral-B provide a wide range of education to dental health care providers and patient education using videos and articles. It was also observed that the oral health education information available online was not limited to manufacturers’ products. Oral care information was also provided online by particular institutions and private practices. In addition to improving services for patients, patient management, and communication, patients education is also provided by companies dedicated to dental care, such as Henry Schein and Patterson Dental. However, none of those provides evidence on the effectiveness of the methods used to educate patients and improved patient care. Such good results can be implemented in other areas of the globe to benefit patients.

This review was limited to the use of CAL programs (one-way delivery of educational content to the user) to improve knowledge, attitude, behavior, and oral health. Studies on patients or caregivers related to home telecare, such as videoconferencing or use of digital systems to guide toothbrushing (eg, personal digital assistant and digital tooth brushing), virtual reality, and simulation of pre- and post-surgery were excluded from this review. CAL programs delivered via non-Web-based (eg, computer-based software and CD-ROMs) and Web-based formats are less complex and less costly, and were included in this review as they are the most widely used for delivering information to patients.9,13 CAL based on direct access via CD-ROM can also reach communities without Internet access,34 while the Web-based method allows information to be accessed online at any time.13 Therefore, the purpose of this review was to identify, in-depth, how CAL in these 2 formats has been used in the dissemination of information to patients, with the goal of informing clinicians as to the potential of CAL to deliver oral health education to a wider population, not only to those patients in the clinical, surgical, or hospital setting.

The use of CAL via Web-based delivery appears to have more advantages over conventional methods of dissemination education such as didactic teaching or the use of computers in the presence of other personnel. These methods are often associated with additional constraints on financial and human resources.24 For instance, the time required for health care providers to deliver health information to an individual or group of patients has been identified as a major issue.13 The development of CAL programs at the initial stages can be costly, difficult, and time consuming.35 The cost of program development and maintenance, however, will be lower in the long run.36,37 Proper planning of the program is also required to ensure that the information can be delivered effectively.38 CAL program development is usually centralized at one particular center that manages the dissemination of information to widely diverse subject groups. Unlike other general or health information that is available online, CAL programs can be tailored to the needs of end users39 either for a particular community or a personalized program. Specific details can be prepared and made relevant to the target group, and this could help to enhance the effectiveness of the intervention.40

Besides tailoring the information for individual cases, a CAL program can also be tailored in terms of viewing time.34 The flexibility to view the program without any restriction in timing or location has resulted in more positive outcomes.41 In addition, it can also increase participants’ satisfaction, concentration,42 and interest.24 This may lead to higher compliance and usage of a CAL program. However, studies have also shown that printed information can have higher usage rates compared to information delivered via computers.34,43,44 This may be due to factors such as a lack of Internet access,45–47 low interest,48 and computer illiteracy.49

There were a few limitations identified from the studies. Small study sample sizes and the lack of control groups likely influenced the study results and their generalizability. The effects of the intervention may also have been influenced by factors such as convenience sampling, small sample sizes, pilot studies, time constraints, computer skills, and technical problems. Technical problems may include the availability of Internet access and computer software compatibility.31 In regard to the STROBE50 and CONSORT51 reporting checklist, this systematic review revealed that the number of items mentioned in the reported articles was low. Hence this may compromise the generalizability of the results due to low quality of the studies.

Three out of the 4 studies that utilized questionnaires did not administer pre-intervention surveys.27,28,31 Therefore, no definitive conclusions can be drawn with regard to the impact of the intervention before and after the programs. Furthermore, as 4 of the 5 studies did not perform follow-up assessments,27,28,30,31 the long-term impact of CAL on knowledge, attitudes, and behavior remains to be determined. In addition, the exclusion of unpublished literature and non-English studies may have resulted in a potential selection bias. Furthermore, large variations across studies in the timing and duration of the interventions, as well as assessment time points, may have led to ambiguous results of the studies on oral health.

CAL can be extended with the use of tablets, mobile phones, or personal digital assistants, which are becoming more common even in low- and middle-income countries. Despite the high incidence of usage in developed countries, little is known on this use as “mobile health.” A study by Kreb and Duncan (2015) found that even with a large proportion of the population using mobile phones, there are still many who do not use health apps due to high cost, low interest, and high data entry.52 In general, the availability of information through computers or digital devices has shown inconsistency or limited improvement in terms of disseminating general health and oral health information, with little evidence. Therefore, proper planning and designing of CAL studies, and their impact, in relation to oral health in disseminating information and educating patients and caregivers are essential. Multidisciplinary collaboration among health stakeholders, database and Web personnel, dental practitioners, and the community may help to increase the dissemination of oral health information through CAL and improve oral health.

Overall, this systematic review shows that there is a need for more studies to strengthen the evidence regarding the impact of CAL on patient and caregiver education, particularly in oral health.

Conclusion

There is a limited number of studies which have examined the effectiveness of CAL interventions for oral health care among patients and caregivers. Preliminary data suggest that CAL has positive impacts on knowledge, attitude, behavior, and oral health. Therefore, there is a need for more quality studies in this area, as CAL could provide an effective and alternative means of disseminating oral health information to patients and caregivers.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the HKU library staff for their help in guiding the authors in the search strategy and performing the database search.

Contributors

N.A.M. drafted the manuscript; conducted the database search, screening the titles, abstracts, and full texts of the potential articles; assessed the relevant papers according to STROBE and CONSORT guidelines; summarized the details of the relevant papers; analyzed and interpreted the information; reviewed and amended the manuscript accordingly; and approved the submitted manuscript. J.Z. participated in screening the titles, abstracts, and full texts of the potential articles; was involved in analyzing the relevant papers; and approved the submitted manuscript. O.L. participated in interpreting the information; consulted persons during the screening; critically revised the manuscript; and reviewed and approved the submitted manuscript. L.J. participated in interpreting the information, critically revised the manuscript, and reviewed and approved the submitted manuscript. C.M. participated in interpreting the information; consulted persons during the screening and analyzing; critically revised the manuscript; and reviewed and approved the submitted manuscript. All authors agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sector.

Competing interests

None.

REFERENCES

- 1. Schou L. Oral health promotion at worksites. Int Dental J. 1989;39: 122–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Eadie DR, Schou L. An exploratory study of barriers to promoting oral hygiene through carers of elderly people. Commun Dental Health. 1992;9: 343–348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kay E, Locker D. A systematic review of the effectiveness of health promotion aimed at improving oral health. Commun Dental Health. 1998;15: 132–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kay EJ, Locker D. Is dental health education effective? A systematic review of current evidence. Commun Dentistry Oral Epidemiol. 1996;24: 231–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Daunt LA, Umeonusulu PI, Gladman JR, et al. Undergraduate teaching in geriatric medicine using computer-aided learning improves student performance in examinations. Age Ageing. 2013;42: 541–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nerlich S. Computer-assisted learning (CAL) for general and specialist nursing education. Aust Crit Care. 1995;8: 23–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bachman MW, Lua MJ, Clay DJ, Rudney JD. Comparing traditional lecture vs. computer-based instruction for oral anatomy. J Dental Educ. 1998;62: 587–591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Messecar DC, Van Son C, O'Meara K. Reading statistics in nursing research: a self-study CD-ROM module. J Nursing Educ. 2003;42: 220–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Schittek M, Mattheos N, Lyon HC, Attstrom R. Computer assisted learning: a review. Eur J Dental Educ. 2001;5: 93–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bonetti D, Johnston M, Pitts NB, et al. Knowledge may not be the best target for strategies to influence evidence-based practice: using psychological models to understand RCT effects. Int J Behav Med. 2009;16: 287–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Houston TK, Richman JS, Ray MN, et al. Internet delivered support for tobacco control in dental practice: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2008;10: e38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Phillips C, Kiyak HA, Bloomquist D, Turvey TA. Perceptions of recovery and satisfaction in the short term after orthognathic surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;62: 535–544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Belda TE. Computers in patient education and monitoring. Respir Care. 2004;49: 480–488. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Catteau C, Faulks D, Mishellany-Dutour A, et al. Using e-learning to train dentists in the development of standardised oral health promotion interventions for persons with disability. Eur J Dental Educ. 2013;17: 143–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fricton J, Chen H. Using teledentistry to improve access to dental care for the underserved. Dental Clin North Am. 2009;53: 537–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Danley D, Gansky SA, Chow D, Gerbert B. Preparing dental students to recognize and respond to domestic violence: the impact of a brief tutorial. J Am Dental Assoc. 2004;135: 67–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. DeBate RD, Severson HH, Cragun D, et al. Randomized trial of two e-learning programs for oral health students on secondary prevention of eating disorders. J Dental Educ. 2014;78: 5–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hsieh NK, Herzig K, Gansky SA, Danley D, Gerbert B. Changing dentists' knowledge, attitudes and behavior regarding domestic violence through an interactive multimedia tutorial. J Am Dental Assoc. 2006;137: 596–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Grigg P, Stephens CD. Computer-assisted learning in dentistry. A view from the UK. J Dentistry. 1998;26: 387–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Krishna S, Balas EA, Spencer DC, Griffin JZ, Boren SA. Clinical trials of interactive computerized patient education: implications for family practice. J Fam Pract. 1997;45: 25–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lewis D. Computers in patient education. Comput Inform Nursing. 2003;21: 88–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lewis D. Computer-based approaches to patient education: a review of the literature. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1999;6: 272–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wofford JL, Smith ED, Miller DP. The multimedia computer for office-based patient education: a systematic review. Patient Educ Counsel. 2005;59: 148–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fox MP. A systematic review of the literature reporting on studies that examined the impact of interactive, computer-based patient education programs. Patient Educ Counsel. 2009;77: 6–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lam OL, Zhang W, Samaranayake LP, Li LS, McGrath C. A systematic review of the effectiveness of oral health promotion activities among patients with cardiovascular disease. Int J Cardiol. 2011;151: 261–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. McGrath C, McMillan AS, Zhu HW, Li LS. Agreement between patient and proxy assessments of oral health-related quality of life after stroke: an observational longitudinal study. J Oral Rehabil. 2009;36: 264–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jerreat M, Youssouf N, Barker C, Jagger DC. Denture care of in-patients: the views of nursing staff and the development of an educational programme on denture care. J Res Nursing. 2007;12: 193–199. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Matthews DC, Rocchi A, Gafni A. Factors affecting patients' and potential patients' choices among anaesthetics for periodontal recall visits. J Dentistry. 2001;29: 173–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ojima M, Hanioka T, Kuboniwa M, Nagata H, Shizukuishi S. Development of Web-based intervention system for periodontal health: a pilot study in the workplace. Med Inform Internet Med. 2003;28: 291–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Albert D, Barracks SZ, Bruzelius E, Ward A. Impact of a Web-based intervention on maternal caries transmission and prevention knowledge, and oral health attitudes. Maternal Child Health J. 2014;18: 1765–1771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. George A, Duff M, Johnson M, et al. Piloting of an oral health education programme and knowledge test for midwives. Contemp Nurse. 2014;46: 180–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rhee RL, Von Feldt JM, Schumacher HR, Merkel PA. Readability and suitability assessment of patient education materials in rheumatic diseases. Arthritis Care Res. 2013;65: 1702–1706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sellen P, Telford A. The impact of computers in dental education. Primary Dental Care. 1998;5: 73–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kroeze W, Oenema A, Campbell M, Brug J. Comparison of use and appreciation of a print-delivered versus CD-ROM-delivered, computer-tailored intervention targeting saturated fat intake: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2008;10: e12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ritterband LM, Thorndike FP. The further rise of internet interventions. Sleep. 2012;35: 737–738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Griffiths F, Lindenmeyer A, Powell J, Lowe P, Thorogood M. Why are health care interventions delivered over the internet? A systematic review of the published literature. J Med Internet Res. 2006;8: e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Brug J, Oenema A, Kroeze W, Raat H. The internet and nutrition education: challenges and opportunities. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2005;59 (Suppl 1): S130–S137; discussion S8-S9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bahrami M, Deery C, Clarkson JE, et al. Effectiveness of strategies to disseminate and implement clinical guidelines for the management of impacted and unerupted third molars in primary dental care, a cluster randomised controlled trial. Bri Dental J. 2004;197: 691–696; discussion 688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ritterband LM, Thorndike F. Internet interventions or patient education web sites? J Med Internet Res. 2006;8: e18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kreuter MW, Wray RJ. Tailored and targeted health communication: strategies for enhancing information relevance. Am J Health Behav. 2003;27 (Suppl 3): S227–S232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Krishna S, Francisco BD, Balas EA, et al. Internet-enabled interactive multimedia asthma education program: a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2003;111: 503–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Jeong YW, Kim JA. Development of computer-tailored education program for patients with total hip replacement. Healthcare Inform Res. 2014;20: 258–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Marks JT, Campbell MK, Ward DS, et al. A comparison of Web and print media for physical activity promotion among adolescent girls. J Adolesc Health. 2006;39: 96–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Marshall AL, Leslie ER, Bauman AE, Marcus BH, Owen N. Print versus website physical activity programs: a randomized trial. Am J Prevent Med. 2003;25: 88–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lin X, Wang M, Zuo Y, et al. Health literacy, computer skills and quality of patient-physician communication in Chinese patients with cataract. PLoS One. 2014;9: e107615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Naganandini S, Rao R, Kulkarni SB. Survey on the use of the Internet as a source of oral health information among dental patients in Bangalore City, India. Oral Health Prevent Dentistry. 2014;12: 141–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zach L, Dalrymple PW, Rogers ML, Williver-Farr H. Assessing internet access and use in a medically underserved population: implications for providing enhanced health information services. Health Info Libr J. 2012;29: 61–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Peels DA, Bolman C, Golsteijn RH, et al. Differences in reach and attrition between Web-based and print-delivered tailored interventions among adults over 50 years of age: clustered randomized trial. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14: e179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Norman CD, Skinner HA. eHealth literacy: essential skills for consumer health in a networked world. J Med Internet Res. 2006;8: e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Vandenbroucke JP, Von Elm E, Altman DG, et al. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. Ann Int Med. 2007;147: W–163-W-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, et al. CONSORT 2010 explanation and elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63: e1–e37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Krebs P, Duncan DT. Health app use among US mobile phone owners: a National Survey. JMIR mHealth uHealth. 2015;3: e101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]