Abstract

Objective: Electronic health record (EHR) data are used to exchange information among health care providers. For this purpose, the quality of the data is essential. We developed a data quality feedback tool that evaluates differences in EHR data quality among practices and software packages as part of a larger intervention.

Methods: The tool was applied in 92 practices in the Netherlands using different software packages. Practices received data quality feedback in 2010 and 2012.

Results: We observed large differences in the quality of recording. For example, the percentage of episodes of care that had a meaningful diagnostic code ranged from 30% to 100%. Differences were highly related to the software package. A year after the first measurement, the quality of recording had improved significantly and differences decreased, with 67% of the physicians indicating that they had actively changed their recording habits based on the results of the first measurement. About 80% found the feedback helpful in pinpointing recording problems. One of the software vendors made changes in functionality as a result of the feedback.

Conclusions: Our EHR data quality feedback tool is capable of highlighting differences among practices and software packages. As such, it also stimulates improvements. As substantial variability in recording is related to the software package, our study strengthens the evidence that data quality can be improved substantially by standardizing the functionalities of EHR software packages.

Keywords: electronic health record, primary care, medical informatics

BACKGROUND AND SIGNIFICANCE

Electronic health record (EHR) systems are increasingly used in primary care in many countries. Technical developments have made it possible to share EHR data among health care providers who are caring for the same patient. Data sharing is necessary in practices with more than 1 physician, and in some countries there is a national data hub that allows doctors to see summary care records of patients of other doctors. Also, clinical decision support and numerous other e-health applications, partly based on EHR data, have emerged to help health care providers provide safer and more effective care. In addition, EHRs are increasingly used to monitor and improve the quality of health care. It is believed that the use and reuse of EHR data may improve quality of care and the health of populations.1–4

However, to actually achieve these benefits, EHR data need to be complete and correct. For example, EHRs need to provide a complete overview of a patient’s comorbidities, intolerances, comedications, and allergies. However, it has been shown that the quality of recording (and the resulting data) in primary care varies substantially and is considered suboptimal in many situations.5–8 It is not a surprise that family physicians are reluctant to depend on EHR data from their colleagues, as they have little confidence in the quality of such data.9,10 In order to enhance the use of EHR, it is necessary to enhance trust in the data, and to achieve this, the quality and comparability of the data should be above suspicion.

Objective

The purpose of this paper is, first, to compare data quality among practices that use different software packages, and second, to evaluate the effect of a data quality feedback tool to enhance the quality of EHR recording and the resulting data.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

A total of 121 practices in the Twente region (eastern part of the Netherlands) were invited to participate in the study. Practices were included in the study if they consented to data extractions to measure the quality of their data. Three software packages were commonly used among these family practices. These are 3 of the 6 most commonly used in the Netherlands.

Intervention

Two EHR data extractions were performed to assess data quality. We measured data quality using the data quality feedback tool (see below). Based on the first measurement, which took place in 2010, family physicians received feedback through a Web portal (see below), in which they were compared with their colleagues elsewhere in the region and grouped by software package. In the period between the 2 measurements, they had the opportunity to improve their recording behavior. Also, participating practices had the opportunity to follow courses that were organized by local experts, family physicians who also participated in the study. During these training courses, the results of the first measurement were discussed and participants were trained on how to interpret the indicator scores and what to do with them. A year after the first feedback, a second measurement was performed to assess to what extent data quality had improved. A chart of the timeline of the study is available as Supplemental Material I.

Survey

All participants were asked to fill out a questionnaire after the first measurement. The purpose of this questionnaire was to collect information on what kind of actions family practices had taken to improve the quality of recording and to evaluate the usefulness of the data quality feedback tool. The questionnaire was developed especially for this project and piloted by local experts. In total, 79 of the original 92 practices returned the questionnaire.

The data quality feedback tool

Data extraction

Data quality indicators for each individual practice were calculated on the basis of data extractions from the EHR systems in 2010 and 2011. On each occasion, data that had been recorded in the previous 12 months were extracted. We used data-extraction tools that were available from the predecessor of the NIVEL Primary Care Database (https://www.nivel.nl/en/dossier/nivel-primary-care-database), the Netherlands Information Network of General Practice.11 EHR data in different formats, originating from different software packages, were entered into 1 uniform database. Data were de-identified at the patient level. Sites were identifiable only to the researchers. As Dutch law allows the use of anonymized EHRs for research purposes under certain conditions, we did not need informed consent or approval by a medical ethics committee for this study (Dutch Civil Law, Article 7:458).12 The study was approved by the steering committee of the Netherlands Information Network of General Practice in 2009.

Development of the data quality indicators

The data quality feedback tool was developed by NIVEL (Netherlands Institute for Health Services Research), together with the Dutch College of General Practitioners and Scientific institute for quality of healthcare (IQ Healthcare). During the process, the setup and outcomes of the tool were regularly presented to an advisory board of family physicians.

Any attempt to assess data quality should start with assessing the purpose for which the data are intended to be used.13,14 In our study, the primary purpose of the data is to help health care providers manage an individual patient’s care. Therefore, the tool primarily focuses on data elements that are incorporated into the Dutch equivalent of the summary care record that is used in the UK.15 The assumption was that these data elements are the most important in the exchange of patient information. How these data elements should be recorded is described by a guideline based on the same assumption, the “adequate EHR recording guideline” issued by the Dutch College of General Practitioners.16,17 It was decided that data quality indicators should focus on following requirements:

EHR data should:

contain a complete overview of patients’ health problems, contraindications and medications.

be structured following the concept of episodes of care. An episode of care should contain all information about diagnosis, referrals, interventions, and medications with respect to a particular health problem, starting with the first contact and ending with the last contact for that problem.

use the International Classification of Primary Care (ICPC) to describe health problems.

The next step was to develop indicators describing the quality of recording with respect to these data elements. An important challenge here was to not mix up quality of care with quality of recording.

The following data quality indicators emerged from this process (see Supplemental Material II for definitions and interpretation of the indicators):

| Indicators for a complete list of patients’ health problems: |

| 1. Average number of active episodes of care per patient |

| 2. Number of episodes that have a “special attention label” as percentage of the episodes that should have this label |

| Indicators for completeness of diagnosis codes: |

| 3. Percentage of episodes that have a “meaningful” ICPC code |

| 4. Completeness of ICPC coding for several diseases based on drug treatment. This was done for: |

| 4a. Diabetes: number of patients who have an episode of diabetes (T90) recorded, as percentage of patients taking blood glucose–lowering medication (A10B) |

| 4b. Asthma/COPD: number of patients who have an episode of asthma or COPD (ICPC R95/R96) recorded, as percentage of patients taking sympathomimetics (ATC: R03A), glucocorticoids (R03BA), or parasympathicolytics (R03BB) |

| 4c. Cardiovascular disease: number of patients who have an episode of hypertension (K86/K87), angina pectoris (K74), heart failure (K77), atrial fibrillation (K78), or other chronic ischemic heart disease (K76) recorded, as percentage of patients taking diuretics (C03), beta-blockers (C07), calcium antagonists (C08), or agents targeting the renin angiotensin system (C09) |

| 4d. Depression: number of patients who have an episode of anxiety disorder (ICPC P74), depressed feelings (P03), or depression (P76) recorded, as percentage of patients taking antidepressants (ATC N06A) |

| 4e. Parkinson’s disease: number of patients who have an episode of Parkinson’s disease (N87) recorded, as percentage of patients taking dopa and its derivatives (N04BA) |

| 4f. Epilepsy: number of patients who have an episode of epilepsy (N88) recorded, as a percentage of patients taking anticonvulsants (N03) |

| 4g. Thyroid disorder: number of patients who have an episode of thyroid disorder (ICPC T85/T86) recorded, as a percentage of patients taking thyroid mimetics (H03A) or thyroid statics (H03B) |

| Indicator for structuring information into episode of care: |

| 5. Percentage of patient encounters recorded as part of an episode of care |

| Indicators for an appropriate medication list: |

| 6. Percentage of drugs not prescribed in the last 6 months, but still labeled as “current medication” |

| 8. Percentage of drugs linked to an episode of care |

| 9. Percentage of drugs linked to an episode with a meaningful ICPC code |

| Indicators for medication safety: |

| 10. Percentage of patients for whom a medication allergy or intolerance is recorded |

| 11. Percentage of patients for whom a contraindication is recorded |

Indicators were based on the last 12 months of recording. Some data quality indicators are partly dependent on the composition of practice populations. For example, the number of active episodes of care is likely to be higher in practices with a larger number of elderly people, irrespective of quality of recording. This applies also to the number of patients with an allergy or intolerance and contraindications. Therefore, these indicator scores were standardized by age and gender. Standardization was performed by weighing the stratum- specific outcomes of the practice populations to the age and gender distribution of the Dutch population

Validation

A possible source of variations could be in the way raw data were extracted or processed.13,18 Therefore, the validity of indicator scores was checked manually by comparing records in our database with records in the original EHR systems and seeing whether these records were identical and whether data were missing. This was done for each of the software packages in 1 or 2 practices. Any anomalies in data or outcomes of the tool were also discussed with the local practice to assess whether data quality indicator outcomes were plausible in the eyes of the practice.

Web portal

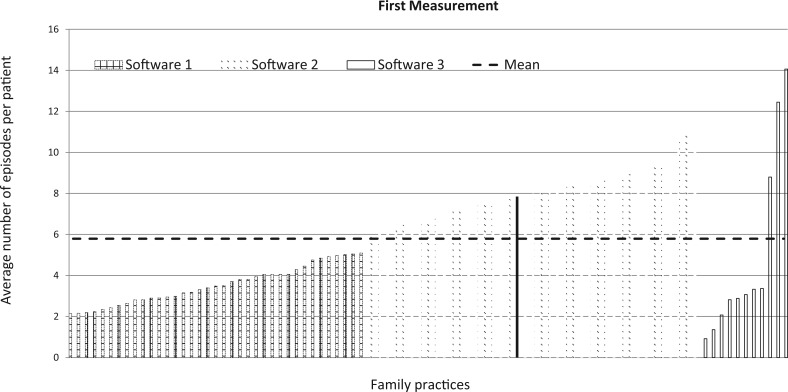

The feedback consisted of graphs for all indicators, showing the scores of an individual practice compared to all other participating individual practices and the overall average. Other participating practices were de-identified to preserve a high participation rate and confidentiality.19,20Figure 1 shows an example of these graphs. In addition, practices received instructions on how to improve data quality, including lists of individual patients with probable incomplete data.

Figure 1.

Average number of active episodes per patient for each practice in the first measurement. The graph is exemplary of the many graphs that were fed back to the family physicians. Each bar represents the score of 1 practice. Scores were ranked and grouped by software package to visualize differences. Each practice’s own score was fed back in red (shown here as a solid line in black).

Philosophy

For many data quality indicators, it is not possible to set clear-cut standards below or above which data quality can be valued as good or bad. This applies, for example, to the number of active episodes of disease. Also, higher or lower scores are not necessarily better scores. The philosophy behind the data quality feedback tool was not to judge, but to make practices aware of their recording behavior and to what extent their scores deviate from other practices. In addition, at a more aggregate level, in many of the indicators, the amount of variation between practices, and software packages as such, is at least as interesting as the number of practices below or above a certain level.

Analyses

Descriptive statistics were computed to investigate differences in scores among participating practices. Differences between the first and second measurement were tested using the Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-ranks test. Differences between software packages were tested using the Kruskal-Wallis rank test. All analyses were performed in STATA (version 13). In addition, multilevel analysis was performed to assess the amount of variance at the level of practices (level 1) of software packages (level 2). For this, we used a model without any explanatory variables.

RESULTS

Participants

Of the 121 practices that were invited to participate in the study, 106 (88%) decided to participate in the first measurement of the tool and consented to extraction of EHR data. Of these 106 practices, 93 participated in the second measurement 12 months later. The main reason for dropout was a change in the ownership or management of a practice. One additional practice was excluded from the analysis because of a change of software package between the first and second measurements. In this paper we use data from the 92 practices with 2 measurements.

Variation among practices

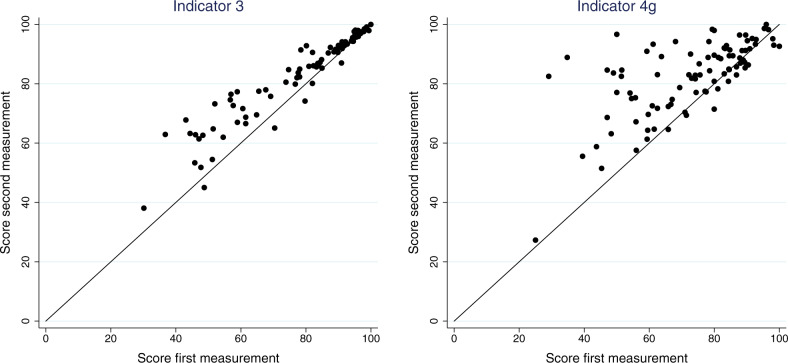

Scores on the individual indicators varied considerably among practices in the first measurement (Table 1). For example, the average number of active episodes per patient ranged from 0.9 to 14, with a mean of 5.7 episodes among practices (see also Figure 1). The percentage of episodes that had a “meaningful” ICPC code (indicator 3) ranged from 30% to 100% among practices, with a mean of 79% (see also Figure 2). In the second measurement, results had improved (Table 1). In general, practices had significantly higher scores in the second measurement; in particular, practices that had scored low in the first measurement yielded much higher scores in the second measurement (Figure 2). The variation among practices was considerably lower in the second measurement (Supplemental Material III, Table 1). Nonetheless, a considerable amount of variation in scores remained (Table 1 and Figure 2).

Table 1.

Results of the first and second measurements with the data quality feedback tool among the 92 practices that participated in the study

| Indicator | Target values for individual practices (see Supplemental Material II for detailed information) | First measurement | Second measurement | Mean difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 92 | N = 92 | |||

| Mean ± SD (min–max) | Mean ± SD (min–max) | |||

| 1. Average number of active episodes of care per patienta | No preset target for individual practices | 5.7 ± 2.8 | 6.5 ± 2.5 | 0.8* |

| (0.9 –14.1) | (2.0 –15.9) | |||

| 2. Percentage of episodes that have a “special attention label” as percentage of episodes that should have this label | High percentage is better | 65.9 ± 30.1 | 70.8 ± 25.8 | 4.9* |

| (0.7 –100.0) | (6.5 –100.0) | |||

| 3. Percentage of episodes that have a “meaningful” ICPC code | High percentage is better | 79.3 ± 18.3 (30.2 –100.0) | 84.1 ± 14.2 (38.0 –100.0) | 4.8* |

| 4a. Number of patients with an ICPC code for diabetes as a percentage of patients taking diabetes medication | High percentage is better | 98.1 ± 2.8 | 98.8 ± 1.5 | 0.7 |

| (84.2 –100.0) | (92.1 –100.0) | |||

| 4b. Number of patients with an ICPC code for asthma/COPD as a percentage of patients taking asthma/Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) medication | No preset target for individual practices | 58.1 ± 13.0 | 67.2 ± 10.8 | 9.0* |

| (18.4 –83.1) | (28.3 –83.9) | |||

| 4c. Number of patients with an ICPC code for cardiovascular disease as a percentage of patients taking cardiovascular medication | No preset target for individual practices | 77.3 ± 11.0 | 85.1 ± 9.0 | 7.8* |

| (41.9 –93.2) | (49.0 –96.6) | |||

| 4d. Number of patients who have an ICPC code for depression as a percentage of patients taking antidepressant drugs | No preset target for individual practices | 48.5 ± 14.3 | 55.2 ± 11.5 | 6.7* |

| (17.6 –76.8) | (21.1 –80.8) | |||

| 4e. Number of patients who have an ICPC code for Parkinson’s disease as a percentage of patients taking medication for Parkinson’s | Percentage near 100% | 76.2 ± 21.3 | 87.4 ± 17.6 | 11.1* |

| (33.3 –100.0) | (50.0 –100.0) | |||

| 4f. Number of patients who have an ICPC code for epilepsy as a percentage of patients taking epilepsy medication | No preset target for individual practices | 30.3 ± 14.1 | 35.5 ± 14.5 | 5.2* |

| (7.5 –65.2) | (10.3 –69.2) | |||

| 4g. Number of patients who have an ICPC code for thyroid disorder as a percentage of patients taking thyroid medication | High percentage is better | 72.7 ± 17.1 | 82.5 ± 12.5 | 9.8* |

| (25.0 –100.0) | (27.3 –100.0) | |||

| 5. Percentage of patient encounters recorded as part of an episode of care | High percentage is better | 91.7 ± 14.7 | 95.5 ± 10.1 | 3.8* |

| (18.9 –100.0) | (42.1 –100.0) | |||

| 6. Percentage of drugs possibly falsely labeled as currentb | Low percentage is better | 6.1 ± 6.6 | 3.6 ± 3.3 | −2.5* |

| (0.2 –25.7) | (0.2 –10.9) | |||

| 8. Percentage of drugs linked to an episode of care | High percentage is better | 54.0 ± 36.5 | 63.0 ± 33.2 | 9.0* |

| (2.1 –98.8) | (5.5 –99.7) | |||

| 9. Percentage of drugs linked to an episode with a meaningful ICPC code | High percentage is better | 84.8 ± 17.0 | 90.7 ± 11.5 | 6.0* |

| (19.8 –99.8) | (42.4 –100.0) | |||

| 10. Percentage of patients for whom a medication allergy or intolerance is recordeda | No preset target for individual practices | 7.0 ± 4.2 | 7.6 ± 4.3 | 0.6* |

| (0.5 –29.9) | (0.0 –32.3) | |||

| 11. Percentage of patients for whom a contraindication is recordeda | No preset target for individual practices | 23.2 ± 15.7 | 41.9 ± 6.4 | 18.7* |

| (1.8 –50.0) | (26.7 –57.6) |

*Significant at P < .05.

aOutcomes of indicator 1, “the active number of active episodes of care per patient,” indicator 10, “percentage of patients for whom a medication allergy or intolerance is recorded,” and indicator 11, “percentage of patients for whom a contraindications is recorded” were weighted to the age and gender distribution of a standard population. bThis is the only indicator for which lower scores can be regarded as better scores.

Figure 2.

Plot of the scores of the 92 participating practices on 2 indicators. Indicator 3: “Percentage of episodes that have a meaningful ICPC code.” Indicator 4g: “Percentage of patients taking thyroid medication who have an ICPC code for thyroid disorder.” Practices with scores above the diagonal line improved on the second measurement; practices further away from the diagonal improved more.

Differences among software packages

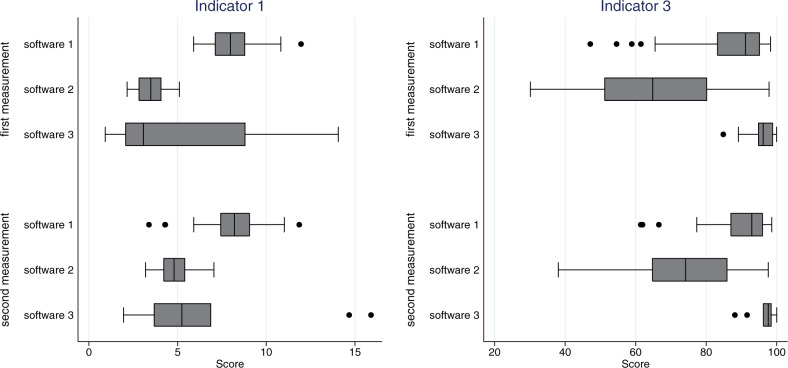

We observed a substantial amount of variation among software packages (Figure 3 and Supplemental Material III, Table 2) in the first measurement. As compared to practices using EHR system 1, practices with EHR system 2 had on average 4.5 fewer active episodes per patient (indicator 1) and had ICPC codes recorded with an episode of care in 20% fewer of their episodes (indicator 3). In EHR system 1, 12% of the prescriptions were likely to be falsely labeled as “current medication” (indicator 6), whereas practices using software 2 and software 3 had on average <2%.

Figure 3.

Comparison of different software packages. Indicator 1: “Average number of active episodes of care per patient.” Indicator 3: “Percentage of episodes that have a meaningful ICPC code.” Box plots indicate median and 25% and 75% quartiles; 10% and 90% are presented with brackets, and lowest and highest values with dots.

Table 2.

Actions taken by physicians, based on the results of the first measurement (N = 79)

| Actions | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Number of physicians who took taken action based on first feedback | 53 (67) |

| Type of action: | |

| Checking patients with probably incomplete data, using the provided patient lists | 37 (47) |

| Better recording of diagnosis with ICPC | 37 (47) |

| Better recording and updating of active episodes | 35 (44) |

| Checking on episodes of special interest | 31 (39) |

| Better recording of allergies | 13 (16) |

| Better recording of contraindications | 8 (10) |

| Other actions | 7 (9) |

Based on the results of the first measurement, the vendor of EHR system 1 actively helped its customers update their current lists of medications and close episodes that were no longer “active.” However, in the second measurement, differences among EHR systems largely remained (Figure 3 and Supplemental Material III, Table 2). For almost all indicators, differences among software packages were significant at P < .05 in the first and second measurements (Supplemental Material III, Table 2). Multilevel analyses confirmed the importance of EHR systems, as a large proportion of the total variance of most indicators was at the level of software (data not shown). For example, about 40% of the total variation in “the percentage of episodes that have a meaningful ICPC code” was at the software level.

User evaluations of the data quality feedback tool

In total, 79 family physicians returned the questionnaire. These physicians were from 67 of the 92 practices that participated in the study. Of these 79 physicians, 78% agreed that the tool was helpful in gaining insight into their recording habits and in pinpointing recording problems; 85% found the tool helped them follow recording guidelines; 67% said they had taken action based on the first measurement (Table 2). Most of them checked for the completeness of ICPC coding and/or used patient lists provided by the feedback tool to check for incomplete or incorrect data, and 44% checked the active status of diseases. A minority of the physicians also checked contraindications or allergies among their patients (Table 2). In the period between the 2 measurements, 86% of the family physicians followed a course to improve their recording. Moreover, 75% indicated that other employees did the same.

DISCUSSION

Summary of findings

The quality of EHR data is important, as EHR data are increasingly used for the exchange of information among health services in providing care for patients. For example, emergency care providers may not have a complete picture of a patient’s medical background, which may result in treatment errors and a lower quality of care.3,21–23 In addition, Dentler et al.24 showed that data quality influences the validity of quality-of-care indicator results in colorectal cancer surgery. Opondo et al.25 found that adherence to prescribing guidelines varies among software packages. In addition, at a more aggregate level, insufficient EHR data quality may result in invalid morbidity estimates and quality-of-care measurements. Van den Dungen et al.,26 for example, showed that calculations of prevalence of diseases based on EHRs is partly dependent on the EHR software package. When used properly, EHR data may contribute to greater patient safety and a more efficient use of scarce resources.27 Good data quality is considered sine qua non for achieving this.

This study describes a data quality feedback tool and its effects, together with accompanying educational training, on the quality of recording in primary care EHRs in 92 family practices.

The data quality indicators in the tool were based on recording guidelines for data elements that are also part of the national summary care record format. Results of the data quality tool were discussed during teaching courses given by peers.

We found substantial differences among practices and software packages. Most physicians agreed that the tool was useful in pinpointing shortcomings in their recording habits. The tool had an impact on recording habits of family physicians, but also on the software vendors, as 1 of them actively changed the functionality of its software package in the period between the 2 measurements. A year after the feedback and educational training, physicians recorded more completely and uniformly, and differences among practices and software packages had diminished. The greatest improvement was achieved among practices that had a relatively low quality of recording at the beginning of the study. However, adequate recording is still far from universal, and a substantial variability in quality of recording is still related to the software package.

Comparison with other methods to improve data quality

A range of methods have been proposed to improve the quality of EHR data, in which feedback, education, and training are often the mainstays.28,29 It has been found that feedback can be an effective tool to raise the quality of EHR in primary care, especially when it is regarded as clinically relevant, educationally oriented, given by peers, and sensitive to the sociotechnical context.30 Several studies have described positive effects.31–35 Other methods, such as self-assessments tools making use of quality probes and audits, have also been used.36,37 One study demonstrated the value of patient access and input in keeping records up to date.38 In the UK, considerably improved levels of data recording have been achieved when financial incentives were introduced as part of the quality and outcomes framework.39 In the Netherlands (partly as a spinoff of this study), part of the reimbursement of family physicians in 2012–2014 was made dependent on the completeness of ICPC code recording, and this too seems to have had a positive effect. To date, it is unclear which approach is the most appropriate. Our study shows that giving feedback and education without any financial compensation, just by creating awareness and relying on intrinsic motivation, can be effective. From the improvement science point of view,40,41 we would have liked to have assessed the impact of individual contributing factors, but this was not possible within the framework of this study. However, the facts that our tool was developed in close cooperation with physicians, our project was supported by an organization that was firmly embedded in the local health care system, and we were able to visualize the results of our tool in an attractive and understandable way, as well as the presence of training courses given by local experts, all made significant contributions.

The role of EHR software

While an effect of software functionality has been found before,42–45 there are not many studies reporting the direct impact of different systems on the data quality of EHR. Substantial heterogeneity and a lack of standardization in EHR software functionality were observed in Australia and France, but the actual effect on data quality was not investigated.46,47 The need to standardize EHR software has long been recognized in the Netherlands. A so-called reference model was first developed by the Dutch College of General Practitioners in the 1990s,48 and nowadays every EHR system complies with this model. However, software packages do vary in the way the requirements of the model are implemented.49,50 For example, in software package 1 it is possible to record patient consultations without entering an ICPC code, whereas in software 2 and 3 omitting an ICPC code is virtually impossible. Software 2 and 3 automatically generate a stop date with a prescription, whereas users of software 1 have to enter a stop date manually. Some of these differences may be attributed to a combination of peculiarities of the software and knowledge about its functionalities by users. For example, many users of software 3 were not aware of the possibility to attach a “special attention label” to a specific disease. Our data quality feedback tool shows the impact of these changes. However, more research is needed to assess the impact of specific EHR design differences, and differences in local settings and configurations. Results of this research will help us to decide whether it is better to focus on improving doctors’ recording behavior or on the design of EHR systems.

Limitations of this study

This study also has some limitations. First, we focused mainly on 1 aspect of data quality: completeness. We think other aspects, like accuracy and correctness, are equally important but dependent on whether a data element is actually recorded (completeness). The different aspects are often viewed as complementary for assessing data quality.51 However, the main problem in EHR data for managing patient care was regarded to be incomplete recording and not necessarily incorrect or inaccurate recording. Still, some of the indicators touch upon the issue of correctness as well, for example, the data quality indicators that focus on the diagnosis recording and medication. These may indicate not only that a particular diagnosis is missing (completeness), but also that the diagnosis information that is recorded is actually wrong. Also, the data quality feedback tool itself is not necessarily limited to indicators for completeness; it may be expanded to indicators for accuracy and correctness.

Another limitation is the lack of a control group. The differences we found between measurements 1 and 2 may reflect a nationwide trend toward EHR data quality improvement. However, within the framework of this study, it was not possible to establish a control group. The primary intention of the study was to improve the quality of recording in a whole region. All practices in the region were invited to participate in the study and data were retrieved only for those that wanted to participate and get feedback on their quality of data.

A third limitation is the fact that it was impossible for us to distinguish the effects of the data quality feedback tool itself and the educational part of the intervention, as almost all participants received both. Furthermore, it has been found in previous studies that feedback should always be accompanied by educational activities to have an impact. However, the positive effect of the tool is supported by the survey material, as most participants indicated that they found the feedback tool useful in itself. Lastly, the participating practices may not have been representative of all Dutch family practices. They may have been more interested in data quality issues and more motivated to change their behavior beforehand.

CONCLUSION

This study describes a data quality feedback tool that shows substantial variation in the quality of recording in EHRs among practices and software packages. Results of this study suggest that providing actionable information to health professionals with this tool, as part of a training intervention, is an effective instrument to improve the quality and comparability of EHR data. Although data quality cannot be addressed by better technology alone, our study also strengthens the evidence that software vendors should be aware of the impact of different implementations of functionalities. We hope that this study contributes to an improvement in the quality of the meaningful use of EHR data.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

For their contribution to this study, the authors wish to thank Jacqueline Noltes, Bennie Assink, Jan Dekker, Herman Levelink, Joris van Grafhorst, Peter Kroeze, Bert Sanders, Khing Njoo, Waling Tiersma, and Stefan Visscher.

CONTRIBUTORS

All authors made substantial contributions to: conception and design; acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data; drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; and final approval of the version to be published.

FUNDING

This work was supported by primary care out-of-hours services cooperations of Twente-Oost and Hengelo, Netherlands.

COMPETING INTERESTS

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1. Blumenthal D, Glaser JP. Information technology comes to medicine. New Engl J Med. 2007;356(24):2527–2534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chaudhry B, Wang J, Wu S, et al. Systematic review: impact of health information technology on quality, efficiency, and costs of medical care. Ann Int Med. 2006;144(10):742–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. King J, Patel V, Jamoom EW, Furukawa MF. Clinical benefits of electronic health record use: national findings. Health Services Res. 2014;49 (1 Pt 2):392–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Delaney BC, Peterson KA, Speedie S, Taweel A, Arvanitis TN, Hobbs FD. Envisioning a learning health care system: the electronic primary care research network, a case study. Ann Family Med. 2012;10(1):54–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Barkhuysen P, de Grauw W, Akkermans R, Donkers J, Schers H, Biermans M. Is the quality of data in an electronic medical record sufficient for assessing the quality of primary care? J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014;21(4):692–698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. de Clercq E, Moreels S, Van Casteren V, Bossuyt N, Goderis G, Bartholomeeusen S. Quality assessment of automatically extracted data from GPs' EPR. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2012;180:726–730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. de Lusignan S, Valentin T, Chan T, et al. Problems with primary care data quality: osteoporosis as an exemplar. Inform Primary Care. 2004;12(3): 147–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Seidu S, Davies MJ, Mostafa S, de Lusignan S, Khunti K. Prevalence and characteristics in coding, classification and diagnosis of diabetes in primary care. Postgraduate Med J. 2014;90(1059):13–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zwaanswijk M, Ploem MC, Wiesman FJ, Verheij RA, Friele RD, Gevers JK. Understanding health care providers' reluctance to adopt a national electronic patient record: an empirical and legal analysis. Med Law. 2013;32(1):13–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zwaanswijk M, Verheij RA, Wiesman FJ, Friele RD. Benefits and problems of electronic information exchange as perceived by health care professionals: an interview study. BMC Health Services Res. 2011;11:256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Verheij RA, van der Zee J. Collecting information in general practice: ‘just by pressing a single button’? In: Westert GP, Jabaaij L, Schellevis FG (red.). Morbidity, performance and quality in primary care. Dutch general practice on stage. Oxon, UK: Radcliffe Publishing Ltd; 2006:265–272. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dutch Civil Law (DCL). Book 7 Dutch Civil Code. Particular agreements. Asten, The Netherlands: DCL. http://www.dutchcivillaw.com/civilcodebook077.htm. Accessed May 16, 2016.

- 13. Khan NA, McGilchrist M, Padmanabhan S., van Staa T., Verheij A. Transform Data Quality Tool. Report on deliverable 5.1 of the TRANSFoRm Project. Transform; 2014. http://www.transformproject.eu/wp-content/uploads/documents/D5.1-Data-Quality-Tool.pdf. Accessed May 16, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kahn MG, Raebel MA, Glanz JM, Riedlinger K, Steiner JF. A pragmatic framework for single-site and multisite data quality assessment in electronic health record-based clinical research. Medical Care. 2012;50 (Suppl):S21–S29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Greenhalgh T, Hinder S, Stramer K, Bratan T, Russell J. Adoption, non-adoption, and abandonment of a personal electronic health record: case study of HealthSpace. BMJ. 2010;341:c5814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nederlands huisartsen genootschap (NHG). Richtlijn adequate dossiervorming met het elektronisch patientendossier ADEPD. Utrecht, The Netherlands: NHG; 2009 https://www.nhg.org/themas/artikelen/richtlijn-adequate-dossiervorming-met-het-epd. Accessed May 16, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nederlands huisartsen genootschap. Richtlijn Gegevensuitwisseling huisarts en Centrale Huisartsenpost (CHP). Utrecht, The Netherlands: NHG; 2008 https://www.nhg.org/sites/default/files/content/nhg_org/uploads/richtlijn_waarneming-v3-24jul081_0.pdf. Accessed May 16, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kahn MG, Brown JS, Chun AT, et al. Transparent reporting of data quality in distributed data networks. EGEMS. 2015;3(1):1052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Smith IR, Foster KA, Brighouse RD, Cameron J, Rivers JT. The role of quantitative feedback in coronary angiography radiation reduction. Int J Qual Health Care. 2011;23(3):342–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Stapenhurst T. The Benchmarking Book: A How-to Guide to Best Practice for Managers and Practitioners. UK: Butterworth-Heinemann; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Greiver M, Barnsley J, Glazier RH, Harvey BJ, Moineddin R. Measuring data reliability for preventive services in electronic medical records. BMC Health Services Res. 2012;12:116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Linder JA, Schnipper JL, Middleton B. Method of electronic health record documentation and quality of primary care. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2012;19(6): 1019–1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Poon EG, Wright A, Simon SR, et al. Relationship between use of electronic health record features and health care quality: results of a statewide survey. Med Care. 2010;48(3):203–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dentler K, Cornet R, ten Teije A, et al. Influence of data quality on computed Dutch hospital quality indicators: a case study in colorectal cancer surgery. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2014;14:32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Opondo D, Visscher S, Eslami S, Verheij RA, Korevaar JC, Abu-Hanna A. Quality of Co-Prescribing NSAID and Gastroprotective Medications for Elders in The Netherlands and Its Association with the Electronic Medical Record. PloS ONE. 2015;10(6):e0129515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. van den Dungen C, Hoeymans N, van den Akker M, et al. Do practice characteristics explain differences in morbidity estimates between electronic health record based general practice registration networks? BMC Family Pract. 2014;15(1):176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Han W, Sharman R, Heider A, Maloney N, Yang M, Singh R. Impact of electronic diabetes registry ‘Meaningful Use' on quality of care and hospital utilization. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2016;23(2):242–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. De Lusignan S TS. The features of an effective primary care data quality programme. In: Ed. Bryant JR. Current perspectives in healthcare computing. Proceedings of HC 2004. Swindon, UK: BCS; 2004:95–102. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Brouwer HJ, Bindels PJ, Weert HC. Data quality improvement in general practice. Family Pract. 2006;23(5):529–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. de Lusignan S. Using feedback to raise the quality of primary care computer data: a literature review. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2005;116: 593–598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Brami J, Doumenc M. Improving general practitioner records in France by a two-round medical audit. J Eval Clin Pract. 2002;8(2):175–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. de Lusignan S, Hague N, Brown A, Majeed A. An educational intervention to improve data recording in the management of ischaemic heart disease in primary care. J Public Health. 2004;26(1):34–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. De Lusignan S, Stephens PN, Adal N, Majeed A. Does feedback improve the quality of computerized medical records in primary care? J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2002;9(4):395–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gilliland A, Mills KA, Steele K. General practitioner records on computer—handle with care. Family Pract. 1992;9(4):441–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Porcheret M, Hughes R, Evans D, et al. Data quality of general practice electronic health records: the impact of a program of assessments, feedback, and training. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2004;11(1):78–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. de Lusignan S, Sadek N, Mulnier H, Tahir A, Russell-Jones D, Khunti K. Miscoding, misclassification and misdiagnosis of diabetes in primary care. Diabetic Med. 2012;29(2):181–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Del Mar CB, Lowe JB, Adkins P, Arnold E, Baade P. Improving general practitioner clinical records with a quality assurance minimal intervention. Brit J General Pract. 1998;48(431):1307–1311. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Staroselsky M, Volk LA, Tsurikova R, et al. Improving electronic health record (EHR) accuracy and increasing compliance with health maintenance clinical guidelines through patient access and input. Int J Med Inform. 2006;75(10-11):693–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Doran T, Kontopantelis E, Valderas JM, et al. Effect of financial incentives on incentivised and non-incentivised clinical activities: longitudinal analysis of data from the UK Quality and Outcomes Framework. BMJ. 2011;342: d3590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Grol R, Baker R, Moss F. Quality improvement research: understanding the science of change in health care. Qual Saf Health Care. 2002;11(2): 110–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Marshall M, Pronovost P, Dixon-Woods M. Promotion of improvement as a science. Lancet. 2013;381(9864):419–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sweidan M, Reeve JF, Brien JA, Jayasuriya P, Martin JH, Vernon GM. Quality of drug interaction alerts in prescribing and dispensing software. Med J Australia. 2009;190(5):251–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hiddema-van de Wal A, Smith RJ, van der Werf GT, Meyboom-de Jong B. Towards improvement of the accuracy and completeness of medication registration with the use of an electronic medical record (EMR). Family Pract. 2001;18(3):288–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. de Lusignan S. The barriers to clinical coding in general practice: a literature review. Med Inform Int Med. 2005;30(2):89–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Adolfsson ET, Rosenblad A. Reporting systems, reporting rates and completeness of data reported from primary healthcare to a Swedish quality register—the National Diabetes Register. Int J Med Inform. 2011;80(9): 663–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Darmon D, Sauvant R, Staccini P, Letrilliart L. Which functionalities are available in the electronic health record systems used by French general practitioners? An assessment study of 15 systems. Int J Med Inform. 2014;83(1): 37–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Pearce CM, de Lusignan S, Phillips C, Hall S, Travaglia J. The computerized medical record as a tool for clinical governance in Australian primary care. JMIR Res Protocols. 2013;2(2):e26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Rijnierse PAJ BE, Westerhof RKD. Publieksversie HIS-referentie model 2011. Utrecht, The Netherlands: Nederlandse huisartsen genootschap (NHG); 2011 https://www.nhg.org/themas/publicaties/his-referentiemodel. Accessed May 16, 2016.

- 49. Hayrinen K, Saranto K, Nykanen P. Definition, structure, content, use and impacts of electronic health records: a review of the research literature. Int J Med Inform. 2008;77(5):291–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Pearce C, Shachak A, Kushniruk A, de Lusignan S. Usability: a critical dimension for assessing the quality of clinical systems. Inform Primary Care. 2009;17(4):195–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Hogan WR, Wagner MM. Accuracy of data in computer-based patient records. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1997;4(5):342–355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.