Abstract

Objective: Our objective was to characterize physicians’ participation in delivery and payment reform programs over time and describe how participants in these programs were using health information technology (IT) to coordinate care, engage patients, manage patient populations, and improve quality.

Materials and Methods: A nationally representative cohort of physicians was surveyed in 2012 (unweighted N = 2567) and 2013 (unweighted N = 2399). Regression analyses used those survey responses to identify associations between health IT use and participation in and attrition from patient-centered medical homes (PCMHs), accountable care organizations (ACOs), and pay-for-performance programs (P4Ps).

Results: In 2013, 45% of physicians participated in PCMHs, ACOs, or P4Ps. While participation in each program increased (P < .05) between 2012 and 2013, program attrition ranged from 31–40%. Health IT use was associated with greater program participation (RR = 1.07–1.16). PCMH, ACO, and P4P participants were more likely than nonparticipants to perform quality improvement and patient engagement activities electronically (RR = 1.09–1.14); only ACO participants were more likely to share information electronically (RR = 1.07–1.09).

Discussion: Participation in delivery and payment reform programs increased between 2012 and 2013. Participating physicians were more likely to use health IT. There was significant attrition from and switching between PCMHs, ACOs, and P4Ps.

Conclusion: This work provides the basis for understanding physician participation in and attrition from delivery and payment reform programs, as well as how health IT was used to support those programs. Understanding health IT use by program participants may help to identify factors enabling a smooth transition to alternative payment models.

Keywords: health information technology, electronic health records, medical home, pay for performance, accountable care organizations

BACKGROUND

There is a major transformation under way in the US health care delivery system.1,2 Beginning in 2016, the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA) mandates shifts to payment adjustments based on care quality, resource use, clinical practice improvement, and meaningful use of certified health IT.3 Concomitant with this is a movement to change care delivery to a more team-based approach that enables increased coordination among providers and better allows for a population health focus. Health care delivery and payment reform models include patient-centered medical homes (PCMHs), pay-for-performance programs (P4Ps), and shared savings through accountable care organizations (ACOs). There are indicators that delivery and payment reform participation is growing, yet little national data exists that characterizes physicians’ overall participation in 1 or more delivery and payment reform activities over time.4–6

Participation in PCMH, ACO, and P4P models may involve major changes to the way physicians practice medicine that are not easy to implement, including adoption and use of health information technology.7–10 Advanced use of health IT for care coordination, patient population management, and patient engagement may be essential to the success of these reform efforts.2,3,11 In spite of this, there is a lack of information about how health IT use impacts participation in delivery and payment reform. Assessing how health IT use is related to care delivery reform participation may shed light on how to support physicians engaged in these activities.

OBJECTIVE

The 2012 and 2013 National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS) Physician Workflow Supplements, longitudinal surveys of a nationally representative cohort of physicians, were used to assess physicians’ use of health IT and their participation in care delivery and payment reform activities. Data from these surveys were used to address the following questions: (1) What were the level of and characteristics associated with physician participation in ACO, PCMH, and P4P models? (2) How were physicians who participated in each of these programs using health IT to coordinate care, manage populations, perform quality improvement programs, or engage patients in their own care? (3) Did health IT use vary with participation in multiple care delivery and payment reform models? (4) What were the ACO, PCMH, and P4P participation trends between 2012 and 2013? (5) What characteristics were associated with changing participation between 2012 and 2013? These data reflect the characteristics and experiences of nationally representative physicians who were early participants in these delivery and payment reform activities and may provide valuable insight regarding how to support physicians in successfully transitioning to the new payment delivery models required under MACRA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population

The NAMCS Physician Workflow Supplement was a series of nationally representative surveys conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics of a cohort of nonfederally employed ambulatory care physicians who provided direct patient care. This series of longitudinal surveys was conducted annually from 2011 through 2013; data from the 2012 and 2013 surveys were used for these analyses. Samples of the complete surveys are available online.12 Additional information on survey methodology was previously published.13,14 In brief, among eligible participants, the unweighted response rate was 56.3% (2567 respondents) for the 2012 survey and 55.3% (2399 respondents) for the 2013 survey.

Independent variables

Independent variables were used to identify characteristics associated with participation in ACO, PCMH, and P4P programs. These variables were grouped into several categories: physician and practice-level characteristics, area characteristics, and use of health IT. The year of the survey was also included to track changes between the 2 years. All data were obtained through physician self-report.

Physician and practice-level characteristics

Physician characteristics were age, sex, and specialty. All practice-level characteristics were based on the physician’s primary practice, defined as the practice in which the physician saw the most ambulatory care patients. Practice size was based on the number of physicians in that practice. Other practice-level characteristics were practice ownership and whether the practice included multiple clinical specialties. Participation in ACO, PCMH, and P4P models was based on whether the physician’s primary practice was active in the respective program.

Area characteristics

Area characteristics were based on the county of the physician’s primary practice location. Micropolitan counties and counties without a core-based statistical area designation were classified as rural.

Use of health IT

Health IT use was based on a dichotomous variable that assessed physician use of an EHR system. EHR users who identified that their system was enabled to meet meaningful use criteria were classified as using certified health IT.15

Outcomes

All percentages are weighted, unless indicated otherwise.

Participation in ACO, PCMH, or P4P programs

Dichotomous outcomes were used to estimate physician participation in 3 types of health care delivery reform: PCMH, ACO, and P4P programs. Participation in these programs was based on whether the physician’s primary practice was active in the program. In addition, a dichotomous composite measure was created to indicate participation in at least 1 of the 3 named programs.

ACO, PCMH, and P4P attrition

Among physicians participating in PCMH, ACO, or P4P programs in 2012, a dichotomous outcome was created to estimate physician attrition from each program in 2013. For each program, the variable assessed 1 of 2 options: whether the physician participated in each program for 2 years (2012 and 2013), or participated in 2012 but stopped participating in 2013.

Because the number of possible iterations to account for switching between programs is too large to measure with this survey sample, 3 composite measures were created to estimate overall participation changes. One composite measure was created to estimate whether a provider stopped participating in any program in 2013; for this measure, physicians were considered to have participated in 2 years of delivery reform if they participated in at least 1 of the 3 programs in 2012 and 2013 (it did not have to be the same program for both years); physicians were considered to have stopped participating in 2013 if they participated in at least 1 delivery reform program in 2012 but did not participate in any of the 3 programs in 2013. The second measure estimated whether the number of programs participated in between 2012 and 2013 increased; this dichotomous measure counted any provider who participated in more programs in 2013 than in 2012 as increasing their participation, and the comparison group included those providers who participated in delivery reform in 2012 and 2013 and in the same number of programs across both years. Finally, a dichotomous measure that estimated declining participation was used to estimate the proportion of providers who decreased the number of programs they participated in between 2012 and 2013, again using those providers who participated in delivery reform in 2012 and 2013 with the same number of programs as the comparison group.

Health IT use for advanced care processes

Eight outcomes were created to estimate the use of health IT to perform selected clinical processes electronically. These clinical processes were population management, patient engagement, care coordination, and quality improvement programs. For each outcome, a physician was considered to have performed the process electronically if the task(s) within the category was performed and the question “Is this process computerized?” was answered in the affirmative.

Two outcomes estimated the use of health IT for population management. The first outcome assessed whether physicians generated a patient list based on patient diagnosis, lab results, or vital signs. The second outcome in this category assessed whether electronic lists of patients due for tests or preventive care were generated.

Three measures of patient engagement were reported separately; these were providing patients with a copy of their health information, recording a patient’s advance directive, and providing patients with a clinical summary for each visit.

Care coordination was separated into 2 categories that estimated electronic health information exchange. The ability to receive health information electronically was captured if the physician indicated an ability to either receive patient clinical information from other treating providers or receive information to manage a post-hospital discharge. Physicians’ ability to send patient clinical information to other health care providers electronically was also estimated.

The quality improvement outcome estimated whether physicians generated reports on clinical care measures for patients with specific chronic conditions or by patient demographic characteristics electronically, or submitted clinical care measures to public or private insurers electronically.

Analysis methods

All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3. Multivariate regressions controlled for survey year and physician and practice-level characteristics. Physician characteristics were age, sex, and specialty. Practice-level characteristics were practice size, ownership, whether the practice included multiple physician specialties, whether the practice was located in a rural care setting, and electronic health record (EHR) adoption. The first set of models estimated overall physician participation in health care delivery reform.

Models that estimated the association between health IT use and health care delivery reform participation used the subset of the physician population that had adopted an EHR. These health IT use models included the same independent variables as the participation models and participation in each of the 3 programs (PMCH, ACO, and P4P) or the composite delivery reform participation variable.

Models that examined physician attrition from ACO, PCMH, or P4P programs in 2013 were based on physician and practice-level characteristics in 2012. These models included the same covariates as the other regression models, with the exception of practice size. Due to the amount of missing data and smaller sample sizes, the models became unstable when practice size was included.

RESULTS

Participation in health care delivery reform programs

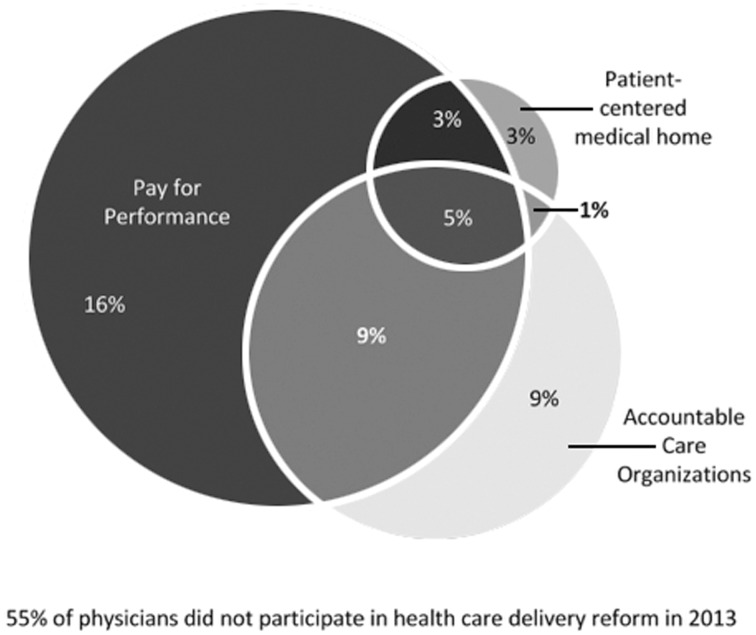

In 2013, 45% of physicians were participating in some form of health care delivery or payment reform program (Figure 1). Pay-for-performance programs had the highest rate of participation (32%), followed by ACOs (24%) and PCMHs (12%). Eighteen percent of all physicians participated in more than 1 health care delivery reform program, and 5% of all physicians participated in all 3 programs.

Figure 1.

Physician participation in health care delivery reform activities in 2013 Source: Authors' analysis of 2013 National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey Physician Workflow Supplement data Note: Percentages represent weighted estimates based on a nationally representative sample of physicians (n = 2399)

Consistent across all 3 programs was a higher level of participation among primary care physicians (19–57%) compared to physicians from other specialties (5–34%) (Supplement 1). Almost two-thirds (65%) of physicians in practices with more than 10 physicians participated in at least 1 delivery or payment reform program; across practice size, solo practice physicians had the lowest rates of participation (24%).

Many of the characteristics associated with delivery and payment reform participation were similar across all programs (Table 1). Adjusting for physician and practice characteristics, participation in ACO and P4P programs increased from 2012 to 2013. Participation in at least 1 delivery or payment reform program was not statistically different between rural and urban settings of care (RR = 0.95, 95% CI, 0.90-1.01). Physicians in practices with more than 10 physicians were more likely than solo practice physicians to participate in P4P programs (RR = 1.27, 95% CI, 1.18-1.38), ACO programs (RR = 1.12, 95% CI, 1.04-1.21), and PCMH programs (RR = 1.13, 95% CI, 1.08-1.19), when controlling for other characteristics.

Table 1.

Physician characteristics associated with health care delivery reform participation, 2012–2013

| Independent Variables | PCMH |

ACO |

P4P |

Any delivery reform participation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR (95% CI) | RR (95% CI) | RR (95% CI) | RR (95% CI) | |

| Health IT Characteristics | ||||

| EHR Adoption (Ref = non-adopter) | ||||

| Adopted certified EHR | 1.07 (1.04, 1.10)* | 1.11 (1.06, 1.15)* | 1.16 (1.10, 1.22)* | 1.20 (1.14, 1.26)* |

| Adopted EHR that is not certified | 0.98 (0.95, 1.01) | 0.97 (0.92, 1.03) | 0.97 (0.91, 1.04) | 0.99 (0.92, 1.06) |

| Survey Year: 2012 (Ref = 2013) | 0.98 (0.95, 1.01) | 0.93 (0.90, 0.97)* | 0.96 (0.93, 0.99)* | 0.94 (0.91, 0.98)* |

| Physician Characteristics | ||||

| Female (Ref = Male) | 0.99 (0.95, 1.02) | 0.97 (0.92, 1.02) | 0.97 (0.92, 1.02) | 0.96 (0.91, 1.01) |

| Physician Age <50 years (Ref = Over 50 years) | 1.01 (0.98, 1.04) | 0.94 (0.90, 0.99)* | 1.01 (0.96, 1.06) | 0.98 (0.94, 1.03) |

| Primary Care Physician (Ref = No) | 1.12 (1.09, 1.15)* | 1.07 (1.03, 1.11)* | 1.15 (1.10, 1.21)* | 1.19 (1.14, 1.25)* |

| Practice Characteristics | ||||

| Practice Ownership (Ref = Physician/Group practice) | ||||

| Hospital/academic med ctr | 1.01 (0.97, 1.04) | 1.08 (1.03, 1.13)* | 1.04 (0.98, 1.10) | 1.1 (1.04, 1.16)* |

| HMO/insurance/other corp | 1.02 (0.96, 1.07) | 1.09 (1.00, 1.18) | 1.19 (1.11, 1.29)* | 1.21 (1.13, 1.30)* |

| Community health center | 1.19 (1.10, 1.29)* | 0.99 (0.91, 1.08) | 1.03 (0.92, 1.15) | 1.06 (0.95, 1.18) |

| Practice Size (Ref = solo) | ||||

| 11+ physicians | 1.13 (1.08, 1.19)* | 1.12 (1.05, 1.20)* | 1.27 (1.18, 1.37)* | 1.27 (1.18, 1.36)* |

| 6–10 physicians | 1.08 (1.03, 1.14)* | 1.05 (0.98, 1.11) | 1.13 (1.05, 1.20)* | 1.17 (1.09, 1.25)* |

| 2–5 physicians | 1.05 (1.02, 1.08)* | 1.04 (0.99, 1.09) | 1.12 (1.06, 1.18)* | 1.13 (1.07, 1.20)* |

| Multispecialty Practice (Ref = No) | 1.00 (0.97, 1.03) | 1.01 (0.97, 1.06) | 0.98 (0.93, 1.02) | 1.00 (0.95, 1.05) |

| Rural Area (Ref = Urban) | 0.98 (0.95, 1.01) | 0.96 (0.92, 1.00) | 0.95 (0.90, 1.01) | 0.95 (0.90, 1.00) |

Source: Authors' analysis of 2012–2013 National Ambulatory Care Survey Physician Workflow Supplements

Notes: Estimates based on generalized linear models. PCMH = patient-centered medical home, ACO = accountable care organization, P4P = pay-for-performance, HMO = Health Management Organization, RR = relative risk, CI = confidence interval. Certified EHR was based on physicians responding in the affirmative to having an EHR system that met meaningful use criteria. Physicians participating in at least 1 of the 3 activities (PCMH, ACO, P4P) were categorized as participating in any delivery reform activity. Asterisks indicate statistical significance at P < .05.

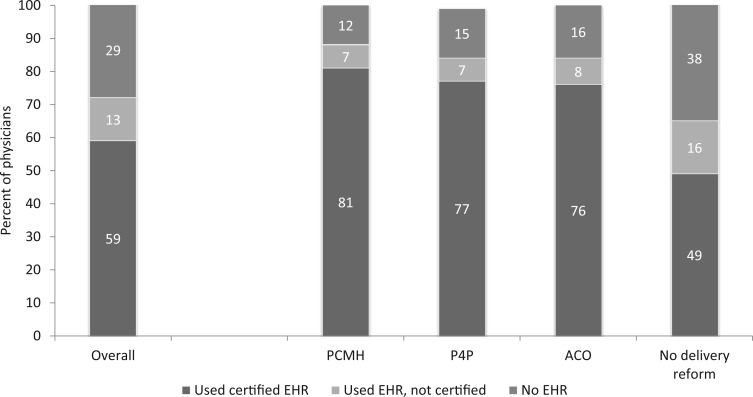

Physicians using certified health IT were 20% more likely to participate in health care delivery or payment reform than those not using an EHR (RR = 1.20, 95% CI, 1.14-1.27). Physicians using EHRs that were not certified had similar rates of participation as physicians who had not adopted an EHR (RR = 0.99, 95% CI, 0.92-1.07). In 2013, more than 8 in 10 physicians who participated in delivery or payment reform reported using health IT, and of those, the majority reported using certified health IT products (Figure 2). The highest rate of use was among PCMH participants (89% using EHRs) and 84% of ACO and P4P participants reporting EHR use. Among physicians who did not participate in delivery or payment reform, EHR adoption was lower (62%), and a higher percentage reported using a system that was not certified.

Figure 2.

Use of electronic health record systems by physician participants in health care delivery reform Source: Authors' analysis of 2013 National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey Physician Workflow Supplement data Notes: Percentages represent weighted estimates based on a nationally representative sample of physicians (n = 2399). PCMH = patient-centered medical home, ACO = accountable care organization, P4P = pay-for-performance. Certified EHR was based on physicians responding in the affirmative to having an EHR system that met meaningful use criteria. Physicians participating in at least 1 of the 3 activities (PCMH, ACO, P4P) were categorized as participating in any delivery reform activity.

Use of health IT for advanced care processes

Physicians with EHRs who participated in at least 1 delivery or payment reform program were more likely to perform each of the 9 health IT processes electronically when compared with physicians with EHRs who did not participate in a reform program (Table 2).

Table 2.

Among EHR adopters, likelihood that delivery or payment reform participants performed clinical processes electronically

| Type of Program Participation | Population Management Activities RR (95% CI) |

Patient Engagement Activities RR (95% CI) |

Care Coordination Activities RR (95% CI) |

Quality improvement |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Generate patient lists | Create reminders for preventive care | Patient access to electronic health information | Record advance directives | Clinical summary to patients | Receive clinical information from other providers | Send clinical information to other providers | ||

| RR (95% CI) | ||||||||

| Overall Delivery Reform Participation | ||||||||

| PCMH (Ref = no PCMH) | 1.14 * | 1.11* | 1.08* | 1.10* | 1.15* | 1.06 | 1.06 | 1.09* |

| (1.07, 1.22) | (1.03, 1.19) | (1.01, 1.16) | (1.01, 1.19) | (1.08, 1.23) | (0.99, 1.13) | (0.99, 1.14) | (1.02, 1.17) | |

| ACO (Ref = no ACO) | 1.10* | 1.04 | 1.10* | 1.11* | 1.10* | 1.07* | 1.09* | 1.12* |

| (1.03, 1.17) | (0.98, 1.11) | (1.03, 1.16) | (1.03, 1.18) | (1.04, 1.17) | (1.01, 1.13) | (1.03, 1.15) | (1.05, 1.19) | |

| P4P (Ref = no P4P) | 1.08* | 1.05 | 1.08* | 1.11* | 1.05 | 1.03 | 1.02 | 1.13* |

| (1.02, 1.14) | (0.99, 1.11) | (1.02, 1.14) | (1.04, 1.18) | (0.99, 1.12) | (0.97, 1.09) | (0.96, 1.08) | (1.07, 1.20) | |

| Multiple Program Participation | ||||||||

| PCMH Participation (Ref = PCMH only) | ||||||||

| ACO + PCMH + P4P | 1.28* | 1.15 | 1.30* | 1.17 | 1.28* | 1.17 | 1.44* | 1.22* |

| (1.11, 1.47) | (1.00, 1.32) | (1.13, 1.49) | (1.00, 1.37) | (1.14, 1.44) | (0.99, 1.38) | (1.17, 1.76) | (1.02, 1.45) | |

| PCMH + ACO | 1.32* | 1.22* | 1.42* | 1.20 | 1.33* | 1.16 | 1.43* | 1.27* |

| (1.12, 1.54) | (1.06, 1.40) | (1.24, 1.62) | (0.98, 1.46) | (1.16, 1.54) | (0.99, 1.37) | (1.15, 1.78) | (1.02, 1.59) | |

| PCMH + P4P | 1.37* | 1.27* | 1.26* | 1.06 | 1.19* | 1.20* | 1.37* | 1.17 |

| (1.21, 1.53) | (1.08, 1.50) | (1.11, 1.44) | (0.90, 1.24) | (1.07, 1.33) | (1.05, 1.37) | (1.12, 1.66) | (0.95, 1.43) | |

| ACO Participation (Ref = ACO only) | ||||||||

| ACO + PCMH + P4P | 1.19* | 1.05 | 1.14 | 1.23* | 1.18* | 1.05 | 1.11 | 1.11 |

| (1.04, 1.36) | (0.90, 1.23) | (1.02, 1.28)* | (1.05, 1.44) | (1.06, 1.32) | (0.90, 1.21) | (0.98, 1.25) | (0.95, 1.30) | |

| ACO + PCMH | 1.24* | 1.19* | 1.22* | 1.30* | 1.22* | 1.06 | 1.13 | 1.17 |

| (1.04, 1.47) | (1.01, 1.40) | (1.09, 1.36) | (1.07, 1.58)* | (1.09, 1.37) | (0.92, 1.22) | (0.98, 1.30) | (0.99, 1.38) | |

| ACO + P4P | 1.12 | 1.05 | 1.04 | 1.18 | 1.03 | 1.02 | 0.99 | 1.07 |

| (0.98, 1.27) | (0.92, 1.20) | (0.92, 1.18) | (1.04, 1.35)* | (0.91, 1.17) | (0.91, 1.14) | (0.87, 1.11) | (0.94, 1.22) | |

| P4P Participation (Ref = P4P only) | ||||||||

| ACO + PCMH + P4P | 1.23* | 1.12 | 1.16* | 1.17* | 1.27* | 1.10 | 1.22* | 1.14 |

| (1.11, 1.37) | (0.97, 1.28) | (1.04, 1.29) | (1.02, 1.35) | (1.15, 1.40) | (0.97, 1.25) | (1.08, 1.39) | (1.00, 1.30) | |

| P4P + PCMH | 1.34* | 1.21* | 1.12 | 1.04 | 1.10 | 1.14* | 1.17* | 1.12 |

| (1.20, 1.49) | (1.07, 1.37) | (0.98, 1.28) | (0.89, 1.22) | (0.98, 1.23) | (1.02, 1.28) | (1.02, 1.34) | (0.97, 1.31) | |

| P4P + ACO | 1.13* | 1.04 | 1.07 | 1.15* | 1.19* | 1.07 | 1.06 | 1.07 |

| (1.02, 1.25) | (0.93, 1.16) | (0.95, 1.20) | (1.02, 1.30) | (1.06, 1.35) | (0.98, 1.18) | (0.96, 1.18) | (0.95, 1.20) | |

Source: Authors' analysis of 2013 National Ambulatory Care Survey Physician Workflow Supplement

Notes: This table shows the rates of performing selected advanced care processes electronically among physicians who adopted EHRs in 2013. Four separate generalized linear models were run for each computerized activity, for a total of 24 models, each controlling for physician and practice-level characteristics. PCMH = patient-centered medical home, ACO = accountable care organization, P4P = pay-for-performance, RR = relative risk, CI = confidence interval. Certified EHR was based on physicians responding in the affirmative to having an EHR system that met meaningful use criteria. Physicians participating in at least 1 of the 3 activities (PCMH, ACO, P4P) were categorized as participating in any delivery reform activity. Asterisks indicate statistical significance at P < .05.

Physicians who used EHRs and participated in ACOs were more likely to perform all selected processes electronically, except for creating reminders for preventive care, compared to physicians with EHRs who did not participate in ACOs.

Among physicians who used EHRs, those who participated in PCMH programs were more likely to complete both population management (RR = 1.11-1.14) functions electronically, compared with physicians who did not participate in PCMH programs. PCMH participants who used EHRs were also more likely to record advance directives electronically (RR = 1.10, 95% CI, 1.01-1.19), provide clinical summaries to patients (RR = 1.15, 95% CI, 1.08-1.23), and perform quality improvement functions electronically (RR = 1.09, 95% CI, 1.02-1.17) than physicians with EHRs who were not participating in PCMH programs. Rates of sending or receiving clinical information electronically were similar between PCMH participants and nonparticipants who used EHRs.

There were 4 functionalities for which physicians who participated in P4P programs were more likely to perform electronic clinical care processes compared to EHR adopters not participating in P4P programs: generating patient lists (RR = 1.08, 95% CI, 1.02-1.14), providing patients access to electronic health information (RR = 1.08, 95% CI, 1.02-1.15), recording advance directives (RR = 1.11, 95% CI, 1.04-1.18), and quality improvement (RR = 1.13, 95% CI, 1.07-1.20).

Among physicians with EHRs who participated in multiple delivery reform programs, many combinations of program participation resulted in an increased likelihood of performing the selected processes electronically, compared to participation in a single program. For example, physicians who participated in a combination of PCMH and ACO programs were more likely to perform quality improvement activities electronically, compared to physicians who participated only in a PCMH program (RR = 1.22-1.27), but there was no statistical difference in performance of those quality improvement tasks between those who participated in both programs and those participating in just an ACO.

Physicians’ receiving and sending electronic health information varied by participation in care delivery and payment reform programs. With the exception of physicians who participated in both P4P and PCMP programs (compared to those who only participated in a P4P), those who participated in multiple delivery or payment reform activities were not more likely to receive clinical information electronically when compared to physicians who participated in a single program. Physicians in PCMH programs in combination with ACO or P4P programs were between 37% and 44% more likely to send clinical information electronically compared to physicians who only participated in a PCMH program; physicians in P4P and PCMH programs were 17–22% more likely to send clinical information electronically than physicians who only participated in a P4P program.

Delivery reform participation trends

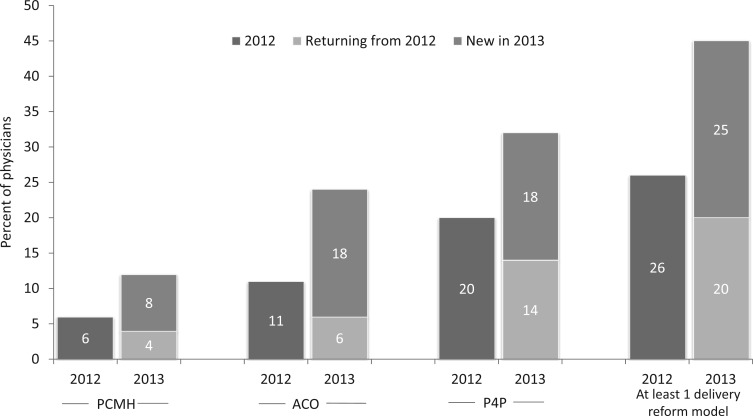

Participation in all 3 programs rose between 2012 and 2013 (Figure 3). One-quarter of physicians were new program participants; new program participation was highest for the ACO program, with 75% of 2013 ACO participants being new to the program.

Figure 3.

Percent of physicians who were participating in ACO, PCMH, and/or P4P activities in 2012 and 2013 Source: Authors' analysis of 2012 and 2013 National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey Physician Workflow Supplements data Notes: Percentages represent weighted estimates based on a nationally representative sample of physicians. This figure shows overall participation trend in ACO, PCMH, and P4P programs between 2012 and 2013, as well as overall participation trends in at least 1 delivery/payment reform activity. PCMH = patient-centered medical home, ACO = accountable care organization, P4P = pay-for-performance. Physicians participating in at least 1 of the 3 activities (PCMH, ACO, P4P) were categorized as participating in any delivery reform activity.

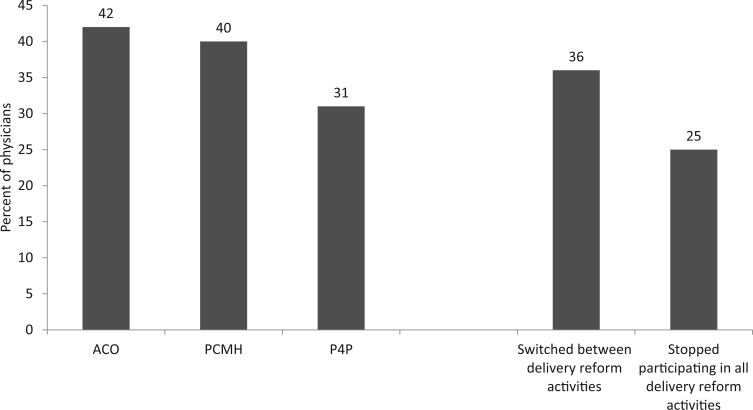

Approximately 42% of physicians participating in an ACO in 2012 stopped participation in 2013, 40% of PCMH-enrolled physicians stopped participating in 2013, and 31% of physicians stopped participating in P4Ps between 2012 and 2013 (Figure 4). This did not mean they stopped participating in delivery or payment reform altogether. While one-quarter of physicians who participated in at least 1 reform program in 2012 dropped from all programs in 2013, more than one-third of physicians switched between 1 or more programs in 2013.

Figure 4.

Among the providers participating in PCMH, P4P, or ACO programs in 2012, the proportion of providers who stopped or changed their participation in 2013 Source: Authors' analysis of 2012 and 2013 National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey Physician Workflow Supplements data Notes: Percentages represent weighted estimates based on a nationally representative sample of physicians. This figures shows the attrition rates from PCMH, P4P, and ACO programs between 2012 and 2013, among physicians who were participating in the respective program in 2012. It also shows the percent of physicians who changed the program they were participating in between 2012 and 2013, or who dropped from all delivery/payment reform activities in 2013. PCMH = patient-centered medical home, ACO = accountable care organization, P4P = pay-for-performance.

Characteristics associated with changing participation

Thirty-seven percent of physicians increased the number of delivery and payment reform programs they participated in between 2012 and 2013 (Table 3). Physician age, sex, specialty, and practice size were associated with increased participation between those 2 years. Physicians who used EHRs and generated patient lists were more likely to increase the number of reform programs they were participating in, compared to EHR users who did not generate patient lists.

Table 3.

Characteristics of physicians who changed participation in delivery or payment reform programs between 2012 and 2013

| Among 2012 PCMH, ACO, P4P program participants, % who stopped participating in all delivery reform | Among 2012 PCMH, ACO, P4P program participants, % who decreased the no. of or switched between programs | Increased no. of delivery reform programs they were participating in (includes providers who did not participate in any program in 2012) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 25 | 16 | 37 |

| Age | |||

| Under 50 | 31 | 23 | 41* |

| Over 50 (Ref) | 22 | 13 | 32 |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 18 | 16 | 41* |

| Male (Ref) | 28 | 16 | 32 |

| Primary Care Physician | |||

| Yes | 33* | 17 | 43* |

| No (Ref) | 20 | 13 | 27 |

| Practice Size | |||

| 11 + physicians | 16 | 8 | 44* |

| 6–10 physicians | 27 | 20 | 34* |

| 2–5 physicians | 25 | 20 | 37* |

| Solo (Ref) | 39 | 5 | 12 |

| Ownership | |||

| Physician/group practice | 25 | 10 | 27 |

| Community health center | 7 | 21 | 54 |

| HMO/insurance co/other health care corp | 25 | 29 | 38 |

| Hospital/academic med ctr (Ref) | 27 | 25 | 47 |

| Rural Area | |||

| Yes | 34 | 15 | 35 |

| No (Ref) | 24 | 27 | 31 |

| EHR Adoption | |||

| Adopted certified EHR | 17* | 18 | 39 |

| Adopted EHR that is not certified | 30 | 10 | 33 |

| Non-adopter (Ref) | 42 | 14 | 32 |

| Among physicians who used EHRs, those who performed the following functions electronically: | |||

| Generated patient lists | |||

| Yes | 17 | 20 | 45* |

| No (Ref) | 23 | 10 | 30 |

| Generated reminders | |||

| Yes | 18 | 17 | 40 |

| No (Ref) | 22 | 16 | 35 |

| Provided electronic copy of health information to patient | |||

| Yes | 14* | 17 | 39 |

| No (Ref) | 27 | 16 | 36 |

| Recorded advance directives | |||

| Yes | 9* | 13 | 37 |

| No (Ref) | 28 | 20 | 38 |

| Provided patient with clinical summary | |||

| Yes | 15* | 17 | 42 |

| No (Ref) | 25 | 16 | 33 |

| Received patient health information electronically | |||

| Yes | 15* | 17 | 40 |

| No (Ref) | 29 | 16 | 33 |

| Sent patient health information electronically | |||

| Yes | 15* | 15 | 40 |

| No (Ref) | 30 | 21 | 33 |

Source: Authors' analysis of 2012 and 2013 National Ambulatory Care Survey Physician Workflow Supplements.

Notes: This table shows the percentage of physicians within each category who changed their delivery/payment reform participation between 2012 and 2013 (as measured by participation in at least 1 of these in 2012: ACO, P4P, PCMH). Asterisks indicate statistical significance of P < .05 in a bivariate analysis. HMO = Health Management Organization, PCMH = patient-centered medical home, ACO = accountable care organization, P4P = pay-for-performance. Certified EHR was based on physicians responding in the affirmative to having an EHR system that met meaningful use criteria. Physicians participating in at least 1 of the 3 activities (PCMH, ACO, P4P) were categorized as participating in any delivery reform activity.

Delivery or payment reform program attrition was higher among physicians who were not using EHRs and those who performed the selected processes electronically. Among physicians participating in delivery or payment reform in 2012, 42% of those who were not using an EHR stopped all participation in 2013, while 17% who used a certified EHR stopped all participation. Physicians who used EHRs in more advanced ways—to engage their patients and exchange patient health information electronically—were less likely to stop all delivery and payment reform activities compared to those who used an EHR but did not perform those activities electronically.

Minimal differences were observed among providers who decreased but did not stop all participation, or switched between programs, in the 2 years studied.

DISCUSSION

Physicians’ participation in delivery and payment reform grew significantly, increasing by more than one-third between 2012 and 2013. By 2013, almost half of all physicians participated in 1 or more delivery or payment reform programs and 18% participated in multiple initiatives. Physicians participating in these programs were more likely to use certified health IT and to use their health IT to perform selected functions electronically. Participation in multiple delivery or payment reform programs was positively associated with performing these functions electronically, with the exception of receiving clinical information. Attrition between 2012 and 2013 was higher among physicians not using certified health IT and those not performing these functions electronically.

Physicians who worked in larger practices were more likely to participate in delivery and payment reform programs. These physicians may have greater resources to support the changes required to participate in such initiatives and may be more likely to be part of organizations establishing ACOs. Smaller practices may need additional technical assistance to engage in such efforts, similar to what was provided through the Regional Extension Center program.16–19 Notable in this work was that no differences were observed in delivery reform participation between rural and urban settings of care, when controlling for other characteristics.

Another factor strongly associated with physician participation in delivery and payment reform was certified health IT adoption. Physicians who had adopted an EHR that was not certified did not have similarly high rates of participation. Prior studies have found more clinical benefits associated with certified EHRs, that certain functions were easier to perform with certified EHRs, and that physicians using certified EHRs were more likely to perform those functions.14,20–23 Some programs, such as the NCQA’s 2011 PCMH certification program and ACOs operated through the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation programs, are aligned with the Medicare and Medicaid EHR incentive programs. This alignment may be the cause of the higher rates of use of certified EHRs among those program participants.

The findings that delivery or payment reform program participants were more likely than nonparticipants to use their health IT to engage their patients, conduct quality improvement activities, manage high-risk populations, and coordinate care are consistent with past analyses.22 There was variation in performing these functions electronically by program type. For example, only ACO participants had significantly higher rates of both sending and receiving health information electronically compared to nonparticipant EHR adopters. This may be because ACO participation requires greater exchange of health information across organizations to manage patient populations, or because the resources of the ACO allow for greater electronic capabilities or a common platform through which participants may exchange information. In contrast, physicians participating in P4P programs demonstrated fewer differences in electronic performance of the selected processes. Other studies have found that hospital P4P programs have not been successful, and emerging evidence on physician P4P programs is mixed.24–33 There may, however, be a synergistic effect between programs: these findings demonstrated that physicians who participated in more than 1 program were more likely to perform the selected functions electronically than those who participated in a single program.

We found extensive attrition and program switching. While primary care physicians were more likely to participate in delivery and payment reform in 2013 and more likely to increase the number of programs they participated in between 2012 and 2013, they were also more likely to stop participating in all delivery or payment reform activities between those 2 years. Recent evaluations of the Pioneer ACO program have found that ACOs participating in these programs achieved savings.33,35 Since delivery and payment reform programs focus on care coordination with a focus on primary care, this attrition trend is something that will need to be monitored and the reasons for it explored.

LIMITATIONS

These data are from 2012 and 2013 and may not reflect current levels of physician participation. Examining the experiences and attrition and program switching among early participants is critical in understanding how physicians can be better supported through care transformation. There are few national analyses that have examined physician participation in care delivery reform and the role of health IT specifically.6

These findings are based upon self-reported data, which may lead to overestimates of EHR adoption and participation in care delivery and payment models. It is also unclear from these analyses whether the health IT use preceded program participation or occurred as a result of participation. In addition, the survey responses are based on activities performed by physicians. It is possible, and likely, that some of the functionalities were performed not by the physician but by other staff in the practice, or by the ACO parent organization. Additional studies should be performed that identify practice- and organizational-level performance of functionalities electronically.

The overall survey response rates were relatively high and all analyses were weighted to account for nonresponse bias. The sample sizes for analyses related to the attrition and program switching and change in care delivery reform participation were relatively small, making it difficult to draw solid conclusions. Future studies that use a mix of qualitative approaches and surveys with larger samples may provide a better understanding of drivers of physician attrition and program switching in care delivery reform participation.

Use of certified EHRs may be underestimated because the survey question asked whether the EHR used was enabled for meaningful use. Physicians not participating in the Medicare or Medicaid EHR incentive programs may not have been familiar with the phrase “meaningful use,” or may not have been aware that their certified technology met meaningful use criteria.

CONCLUSION

Physician attrition and program switching in delivery and payment models at this early stage were high. Monitoring physician participation in and attrition from delivery and payment reform programs as the US health care system shifts to a value-based payment structure will be critical to ensure that high-quality, affordable care is available to all patients. This work provides the basis for understanding which health IT functionalities were being used to support delivery and payment reform programs. Understanding the intersection between health IT adoption and use and payment and delivery reform may allow for a better assessment of what may be required for a successful systemwide transition to value-based payment.

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sector.

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

D.H.G. and V.P. designed and interpreted the data; D.H.G. completed the data analyses; D.H.G. and V.P. contributed to the writing, review, editing, and final approval of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1. Burwell SM. Setting value-based payment goals – HHS efforts to improve U.S. health care. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(10):897–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Maxson ER, Jain SH, McKethan AN, et al. Beacon communities aim to use health information technology to transform the delivery of care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(9):1671–1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015, Pub.L. 114-10. https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/house-bill/2/text/pl. Accessed November 15, 2015.

- 4. National Committee for Quality Assurance. Fact Sheet: Patient-Centered Medical Homes. (2015) https://www.google.com/url?sa=t& rct=j&q =&esrc =s&source=web&cd= 1&ved=0CB4QFjAAahUKEwi44v 7G0avIAhUM1h4K H f93AIg&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.ncqa.org%2FPortals%2F0 %2 F Public %2520Policy%2F2014%2520PDFS%2Fpcmh_2014_fact_sheet.pdf &usg = AFQjCNHwfdEMfyffCjiB3GOwZumCzx4tNA. Accessed October 5, 2015.

- 5. Muhlestein D. Growth and dispersion of accountable care organizations in 2015. Health Affairs Blog. March 31, 2015. http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2015/03/31/growth-and-dispersion-of-accountable-care-organizations-in-2015-2/. Accessed October 5, 2015.

- 6. Shortell SM, McClellan SR, Ramsay PP, Casalino LP, Ryan AM, Copeland KR. Physician Practice Participation in Accountable Care Organizations: The Emergence of the Unicorn. Health Services Res. 2014;49(5):1519–1536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bitton A, Schwartz GR, Stewart EE, et al. Off the hamster wheel? Qualitative evaluation of a payment-linked patient-centered medical home (PCMH) pilot. Milbank Q. 2012;90(3):484–515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Crabtree BF, Nutting PA, Miller WL, et al. Primary care practice transformation is hard work: insights from a 15-year developmental program of research. Med Care. 2011;49 (Suppl):S28–S35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cronholm PF, Shea JA, Werner RM, et al. The patient centered medical home: mental models and practice culture driving the transformation process. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(9):1195–1201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wise CG, Alexander JA, Green LA, et al. Journey toward a patient-centered medical home: readiness for change in primary care practices. Milbank Q. 2011;89(3):399–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bates DW, Bitton A. The future of health information technology in the patient-centered medical home. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(4): 614–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Ambulatory Health Care Data Survey Instruments. (cited March 14, 2016; updated January 17, 2016). www.cdc.gov/nchs/ahcd/ahcd_survey_instruments.htm. Accessed January 20, 2016.

- 13. Jamoom E, Beatty P, Bercovitz A, et al. Physician adoption of electronic health record systems: United States, 2011. NCHS Data Brief, no 98. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. King J, Patel V, Jamoom EW, et al. Clinical benefits of electronic health record use: National findings. Health Serv Res. 2014;49(1 Pt 2):392–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Medicare and Medicaid Programs; Electronic Health Record Incentive Program (Final Rule). Federal Register. 2010;75:144, p. 44314. [PubMed]

- 16. Ryan AM, Bishop TF, Shih S, et al. Small physician practices in New York needed sustained help to realize gains in quality from use of electronic health records. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(1):53–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Audet AM, Squires D, Doty MM. Where are we on the diffusion curve? Trends and drivers of primary care physicians' use of health information technology. Health Serv Res. 2014;49(1 Pt 2):347-360.R [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lynch K, Kendall M, Shanks K, et al. The health IT Regional Extension Center program: evolution and lessons for health care transformation. Health Serv Res. 2014;49(1):421–437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Heisey-Grove D, Danehy LN, Consolazio M, et al. A national study of challenges to electronic health record adoption and meaningful use. Med Care. 2014;52(2):144–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Heisey-Grove D, King J. Physician and practice-level drivers and disparities around meaningful use progress. Health Serv Res. 2015. 2016 Mar 16, epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Furukawa M, Patel V, King J. Physician attitudes on ease of use of EHR functionalities related to meaningful use. AJMC, 21(12):e684–692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. King J, Patel V, Jamoom E, et al. The role of health IT and delivery system reform in facilitating advanced care delivery. Am J Manag Care. 2016;22(4):258–265. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Heisey-Grove D, Hunt D, Helwig A. Physician-reported direct and indirect safety impacts associated with electronic health record technology use. ONC Data Brief, no.19. Washington, DC: Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology; September 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ryan AM. Effects of the Premier Hospital Quality Incentive Demonstration on Medicare patient mortality and cost. Health Serv Res. 2009;44(3):821–842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ryan AM, Blustein J. The effect of the MassHealth hospital pay-for-performance program on quality. Health Serv Res. 2011;46(3):712–728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ryan AM, Blustein J, Casalino LP. Medicare's flagship test of pay-for-performance did not spur more rapid quality improvement among low-performing hospitals. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(4):797–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ryan AM, Burgess JF, Jr, Pesko MF, et al. The early effects of Medicare's mandatory hospital pay-for-performance program. Health Serv Res. 2015;50(1): 81–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ryan AM, McCullough CM, Shih SC, et al. The intended and unintended consequences of quality improvement interventions for small practices in a community-based electronic health record implementation project. Med Care. 2014;52(9):826–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Scott A, Sivey P, Ait Ouakrim D, et al. The effect of financial incentives on the quality of health care provided by primary care physicians. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Petersen LA, Woodard LD, Urech T, et al. Does pay-for-performance improve the quality of health care? Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(4):265–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lemak CH, Nahra TA, Cohen GR, et al. Michigan's fee-for-value physician incentive program reduces spending and improves quality in primary care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34(4):645–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Damberg CL, Elliott MN, Ewing BA. Pay-for-performance schemes that use patient and provider categories would reduce payment disparities. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34(1):134–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Conrad DA, Grembowski D, Perry L, et al. Paying physician group practices for quality: A statewide quasi-experiment. Healthc (Amst). 2013;1(3-4): 108–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. McWilliams JM, Chernew ME, Landon BE, et al. Performance differences in year 1 of pioneer accountable care organizations. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(20):1927–1936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Nyweide DJ, Lee W, Cuerdon TT, et al. Association of Pioneer Accountable Care Organizations vs traditional Medicare fee for service with spending, utilization, and patient experience. JAMA. 2015;313(21):2152–2161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]