Abstract

Objectives: Medication reconciliation (MedRec) is essential for reducing patient harm caused by medication discrepancies across care transitions. Electronic support has been described as a promising approach to moving MedRec forward. We systematically reviewed the evidence about electronic tools that support MedRec, by (a) identifying tools; (b) summarizing their characteristics with regard to context, tool, implementation, and evaluation; and (c) summarizing key messages for successful development and implementation.

Materials and Methods: We searched PubMed, the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, Embase, PsycINFO, and the Cochrane Library, and identified additional reports from reference lists, reviews, and patent databases. Reports were included if the electronic tool supported medication history taking and the identification and resolution of medication discrepancies. Two researchers independently selected studies, evaluated the quality of reporting, and extracted data.

Results: Eighteen reports relative to 11 tools were included. There were eight quality improvement projects, five observational effectiveness studies, three randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or RCT protocols (ie, descriptions of RCTs in progress), and two patents. All tools were developed in academic environments in North America. Most used electronic data from multiple sources and partially implemented functionalities considered to be important. Relevant information on functionalities and implementation features was frequently missing. Evaluations mainly focused on usability, adherence, and user satisfaction. One RCT evaluated the effect on potential adverse drug events.

Conclusion: Successful implementation of electronic tools to support MedRec requires favorable context, properly designed tools, and attention to implementation features. Future research is needed to evaluate the effect of these tools on the quality and safety of healthcare.

Keywords: medication reconciliation, health information technology, quality improvement, continuity of care, patient safety

Introduction

Medication management continuity is a worldwide patient safety concern and a very complex task1,2 requiring communication and information-sharing among providers, patients, and families across different settings.3 Patients are therefore at risk for medication discrepancies during transitions from one care setting to another.4,5 These discrepancies – unexplained differences among documented regimens across different sites of care6 – can lead to a prolonged hospital stay, early readmission, unplanned visits to the emergency department,4 and even death.7

Medication reconciliation (MedRec) is a formal and collaborative process of obtaining and verifying a complete and accurate list of a patient’s current medicines8 to ensure that precise and comprehensive medication information is transmitted consistently across care transitions.9 Several leading organizations worldwide, such as the World Health Organization, The Joint Commission, the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, the National Institute of Clinical Excellence, and the Canadian Patient Safety Institute, have campaigned for the implementation of MedRec. Despite this, most healthcare organizations are struggling to develop efficient tools and effective implementation strategies.3,7,10,11 Successful MedRec is resource-intensive: it is time-consuming, requires multidisciplinary collaboration, and imposes a cognitive burden on clinicians that could be relieved by the use of technology.2,9,12

Efforts to reduce medication discrepancies using health information technology (IT) have recently emerged13 and different organizations have clearly indicated that technology to support the MedRec process will be essential for its successful implementation across the healthcare system. Electronic medication reconciliation (eMedRec) tools are computerized tools used to help support MedRec processes. These tools allow healthcare providers to compare the best possible medication history to orders and to identify discrepancies by displaying medication lists and to resolve discrepancies by providing the following options: continue, change, or discontinue a medication.14

Whereas previous systematic reviews summarized the available evidence on MedRec,4,5 and a few narrative or scoping reviews have addressed the use of IT in MedRec,3,15,16 to our knowledge, there has been no systematic review of electronic tools (e-tools) to support MedRec. Bassi et al.3 performed a scoping review of primary studies published up to March 2009 that looked at the use of IT in the MedRec process. They found that IT was mainly used to obtain medication information, but very few systems at that time used a fully enabled eMedRec tool. However, the authors reported that promising applications were being developed to support the entire MedRec process. Original studies have since described the development and evaluation of such tools.2,9,12,17,18 We therefore aimed to systematically review the evidence about e-tools that fully support MedRec, by (1) identifying tools; (2) summarizing their characteristics with regard to context, tool, implementation, and evaluation; and (3) summarizing key messages for successful development and implementation of eMedRec tools.

Materials and Methods

Data Sources and Searches

We performed a systematic search of articles published from database inception up to October 2014 using PubMed, the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, Embase, PsycINFO, and the Cochrane Library. We developed the search strategy in consultation with a medical librarian who is experienced in systematic review. We used an iterative process of building a search strategy, running the search, searching the relevant articles for additional terms, and then rebuilding the search strategy. Our search strategy consisted of a combination of subject heading terms and free-text words combining two groups of themes: (1) continuity of care – medication reconciliation, and (2) IT. The final search strategy for PubMed (see Supplementary Appendix I) was then adapted for each database. The other queries can be provided on request.

To identify additional eMedRec tools (both those about which reports have been published and those that have not), we (1) scanned the reference list of included studies and relevant reviews; (2) searched patent databases, ie, the FamPat database (Questel Orbit) and the Espacenet database with the help of Picarre Intellectual Property; (3) searched recent grey literature reports referring to eMedRec;14,19 and (4) scanned the list of articles that subsequently referenced the papers included using Scopus (last search November 2015). More information is available on request.

Study Selection

Eligible reports included original full-text articles, proceedings, and patents describing e-tools that supported all three steps of the MedRec process, namely, (1) gathering the best possible medication history, (2) comparing the different lists in order to identify discrepancies, and (3) resolving those discrepancies. Reports had to contain both a description of the tool and some kind of evaluation, whether regarding a health outcome, provider satisfaction, adherence, utilization, or efficiency. Proceedings and patents were also included – in addition to original full-text articles – because these are frequent forms of publication for health IT tools. If several patents had been written for the same tool, we used the most recent. Because the information available in proceedings is limited, for potentially eligible proceedings, we contacted authors by e-mail to request additional information and/or clarification, using a standardized form and screenshots of the tool. This additional information was then used for study selection and data extraction. If three e-mails to the proceedings authors went unanswered, the proceedings were then excluded.

We excluded reports that did not include a description of the tool, reports referring to an e-tool that only partially supports the MedRec process, reports on the reconciliation of specific drugs and classes, review papers and commentaries, and non-English-language reports. There were no restrictions regarding study type, setting, or type of care transition.

Two reviewers (B.K. and S.M.) independently evaluated the eligibility of reports by first examining their titles and abstracts, and then the full text of reports identified as potentially eligible for this study. Disagreements were resolved by discussion, and, when consensus could not be reached, a third author (A.S.) was consulted and a decision was made. Eligibility was delayed for proceedings and for studies reporting data incompletely, pending author contact (see above).

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

A standardized data extraction form (Supplementary Appendix II) was created based on (1) the Effective Practice and Organization of Care data collection form,20 (2) forms used in previous systematic reviews,3,4,21 and (3) reports from the gray literature on eMedRec.14,19 The form was piloted on four reports by 3 reviewers (A.S., B.K., and S.M.) to ensure completeness, clarity, and reliability. Data extraction included study design (using a recently published categorization of improvement interventions22) and description of context, tool, implementation and evaluation, and lessons learned as reported by the authors. Two reviewers (S.M. and B.K.) independently extracted data. Disagreements were resolved by consensus.

For each report, we evaluated quality in two complementary ways. First, the quality of reporting of the context, tool, and implementation/evaluation was evaluated with the criteria used in a recent systematic review of patient portals.21 These criteria had been modified from criteria developed to assess patient safety strategies, which included health IT applications.23 Second, based on the Canadian Paper to Electronic MedRec Implementation Toolkit14 and on the American Multi-Center Medication Reconciliation Quality Improvement Study (MARQUIS) toolkit to disseminate best practices in inpatient MedRec,19 we listed the main ideal features needed to for a user-friendly and efficient eMedRec tool, and, for each report, we evaluated whether each feature was present.

Data Synthesis and Analysis

Due to the large variation in study types and measurements, a meta-analysis of the studies considered was not possible. Instead, we constructed evidence tables showing the characteristics and results for all included reports and critically analyzed the data. Reports that referred to a single eMedRec tool were grouped together. Finally, we compiled a summary of recommendations made by the authors of the included studies for the successful development and implementation of eMedRec tools. We categorized these factors as being relative to the tool, context, or implementation and used them to draw conclusions.

Results

Study Selection

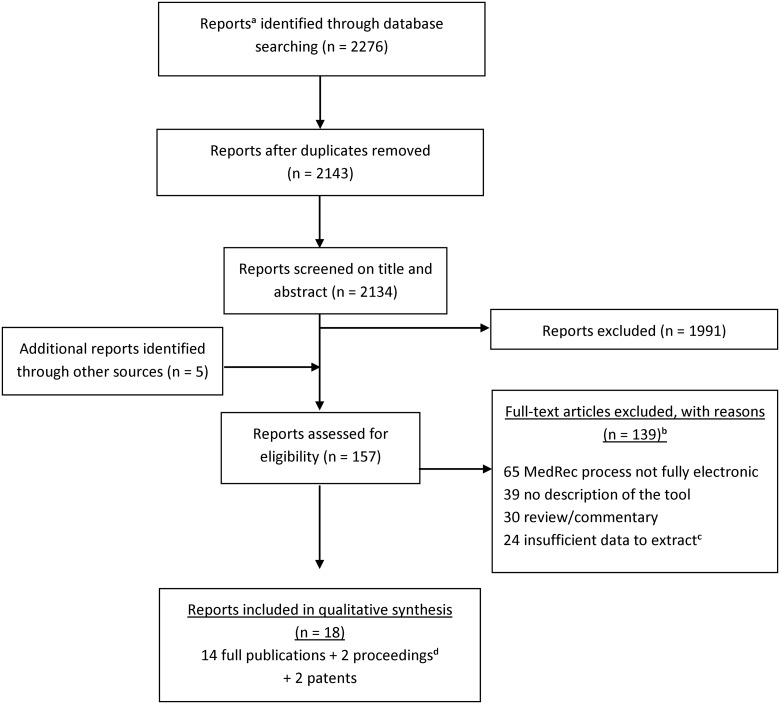

Overall, the search strategy yielded 2143 reports following duplicate removal, of which 1991 were discarded after examining the title and abstract (Figure 1). Of the 152 reports that were selected for full-text screening (or screening of additional information sent by authors, in the case of proceedings) and 5 additional reports identified through reference list searching, 18 met our inclusion criteria (14 published articles, 2 proceedings, and 2 patents). The main reasons for exclusion were (1) the tools described did not support all three steps of the MedRec process, and (2) the report lacked a description of the tool.

Figure 1.

Search strategy and study selection. aReports include full-text articles, proceedings and patents. bReports could be excluded for more than one reason. cInsufficient data means: full text not available or unanswered request by authors of proceedings. dProceedings were included if authors could send us relevant additional information so that publication met inclusion criteria and that data could be extracted.

Description of Studies

The 18 reports included in this study were published over the last 10 years and describe 11 different eMedRec tools. Five reports were about the Automated Patient History Intake Device (APHID),10,11,24–26 three were about the PreAdmission Medication List Builder,1,27,28 two were about the Twinlist,9,12 and there was one report about each of the other tools. According to Portela’s classification, eight reports were quality improvement projects,1,2,9,12,24,29–31 five were effectiveness observational studies,11,25,27,32,33 and three were randomized controlled trials (RCT)28 or RCT protocols.7,10 Because the two remaining reports were patents, we could not classify them in one of these categories. Table 1 summarizes the characteristics and main results of the reports included in this study. The quality of the reports' description of the context, the tool, and the implementation are reported in Table 2.

Table 1.

Description of Studies and Main Results

| e-Tool | Author, country, year | Point of investigation | Objective(s) of the study | Study classa | Main results of evaluationb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The PreAdmission Medication List (PAML) Builder | Poon, USA, 20061 | Admission, discharge | To describe the design of a novel application and the associated services that aggregate medication data from EMR and CPOE systems | Quality improvement project |

|

| Turchin, USA, 20082,7 | Admission, discharge | To assess clinicians' attitudes toward eMedRec, their compliance and the factors that affect their efficiency and compliance | Effectiveness observational study |

|

|

| Schnipper, USA, 20092,8 | Admission, discharge | To measure the impact of an eMedRec intervention on medication discrepancies with the potential for harm | RCT |

|

|

| A tool within the EMR to facilitate MedRec after hospital discharge | Schnipper, USA, 201132 | Post- discharge | To describe the design and implementation of the tool, attempts to improve use, informal feedback from clinicians, and generalizable lessons learned to maximize the usability of the tool and its impact on patient safety | Effectiveness observational study |

|

| A tool for MedRec after hospital discharge with an (electronic) retrieval of community drugs and an (electronic) communication module | Tamblyn, Canada, 20127 | Discharge | To determine whether electronically enabled discharge MedRec reduces the risk of adverse drugs events, emergency room visits, and readmissions 30 days post-discharge compared with usual care | RCT protocol | O: Adverse drug events, emergency visits, hospital readmissions 30 days post-discharge. |

| MedRec application | Cadwallader, USA, 20132 | Outpatient | To design a MedRec application that could incorporate multiple data sources and convey information about patients' adherence to prescribed medications | Quality improvement project | U: Feedback of clinicians, IT professionals, pharmacists, and nurses were collected. Each prototype then underwent iterative revisions to incorporate their feedback. A final prototype was then created by incorporating the best features of each initial approach. |

| e-Tool | Author, country, year | Point of investigation | Objective(s) of the study | Study classa | Main results of evaluationb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Twinlist | Markowitz, USA, 20111,2 | Post- discharge | To evaluate whether a systematic user interface design process will dramatically improve the efficiency and quality of MedRec process | Quality improvement project | U/E: Three tasks were analyzed via the KLM analysis: reconciling two identical medications, removing a medication, and editing its dosage. The number of actions, the number of required mental operations, and overall task completion time were lower for the prototype than either LHS RxPad or PAML. |

| Plaisant, USA, 20139 | Discharge | To describe Twinlist, an interface that provides cognitive support for MedRec. To describe a series of variant designs and discuss their advantages or disadvantages. To report a pilot study. | Quality improvement project | U = Feedback from 20 users: the Twinlist spatial layout is a meaningful grouping and the multistep animation is helpful for learning (70%). | |

| The Automated Patient History Intake Device (APHID) | Lesselroth, USA, 20092,4 | Outpatient | To describe project design and implementation, review preliminary findings on feasibility, and discuss the barriers to adoption encountered by the development team | Quality improvement project |

|

| Lesselroth, USA, 200911 | Outpatient | To describe how a process for patients in the waiting room to use kiosk technology in providing their own medication histories was developed and implemented | Effectiveness observational study |

|

| e-Tool | Author, country, year | Point of investigation | Objective(s) of the study | Study classa | Main results of evaluationb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lesselroth, USA, 20112,5 | Outpatient | To describe the development, administration, and findings of a survey intended to assess PCP perceptions of the tool in an effort to identify factors that can influence implementation | Effectiveness observational study |

|

|

| Lesselroth, USA, 201210 | Outpatient | To evaluate the accuracy of the medication list produced using the software. To measure the incremental value of including medication pictures. To characterize the types and root causes of medication discrepancies detected using the software. | RCT protocol | E: Number of discrepancies, types, root cause, and severity. | |

| Lesselroth, USA, 20142,6 | Any | To describe the invention: APHID supporting medication reconciliation, clinic check-in, demographic and insurance data verification, and allergy review | Patent | NA | |

| A MedRec view within the EHR displaying two columns: inpatient and outpatient medications’ list | Vawdrey, USA, 20102,9 | Admission, discharge | To assess the impact of adopting the eMedRec process at a large academic medical center | Quality improvement project |

|

| A MedRec application launched from within the EHR | Bails, USA, 200830 | Admission, discharge | To describe the interdisciplinary process undertaken at a large academic medical center, to develop a full online MedRec program | Quality improvement project | A: In phase 1, MedRec was done for only 20% of patients. In phase 2, after providing feedback and making eMedRec mandatory, compliance rates achieved 95%. |

| Electronic pathway for MedRec | Lovins, USA, 201131 | Admission, transfer, discharge | To implement an eMedRec pathway to reduce medication errors happening after transitions of care | Quality improvement project |

|

| e-Tool | Author, country, year | Point of investigation | Objective(s) of the study | Study classa | Main results of evaluationb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Discharge Instruction element | Sherer, USA, 201133 | Admission, discharge | To determine the accuracy of the discharge medication list made with the Discharge Instruction element and given to the patient by comparing this list with the list dictated in the discharge summary | Effectiveness observational study |

|

| Interactive Patient Medication List | Tripoli, USA, 20143,4 | NA | To describe the invention: system, methods, and techniques for presenting a medication list to a patient and for maintaining updates to the medication list | Patent | U: Feedback from pharmacists. |

CI, confidence interval; CPOE, computerized physician order entry; eMedRec, electronic medication reconciliation; EHR electronic health record; EMR, electronic medical record; e-tool, electronic tool; IT, information technology; KLM, Keystroke-Level Model; LHS RxPad, Legacy Health System with RxPad record; MedRec, medication reconciliation; NA, not applicable; PCP, primary care provider; RCT, randomized controlled trial; RCT protocol, description of RCT in progress.

aStudy class: According to Portela’s published improvement interventions categorization.22

Quality improvement projects: Project is set up primarily as an improvement effort, to learn what works in a local context. It is typically motivated by a well-defined problem and oriented towards a focused aim. Plan-Do-Study-Act cycles are often applied, allowing for testing incremental, cyclically implemented changes, which are monitored through statistical process control.

- RCTs

- Quasi-experimental designs: The intervention is implemented and followed up over time, ideally with a control.

- Observational (longitudinal) studies: The implementation of the intervention is observed over time.

bResults: O = health outcomes; S = satisfaction; A = adherence; U = utilization; E = efficiency.

Table 2.

Description of the Context, System, Implementation and Presence of Ideal Features of eMedRec Tools

| e-Tool | Author, country, year | Context |

Tool |

Implementation/Evaluation |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Description criteriaa | Description criteriab | Integrated into the workflow? | Linked to other electronic systems?c | Automatic highlighting of discrepancies? | Reason for stopping medication written? | Different possibilities for organizing medication lists? | Description criteriad | eMedRec process with reminder or mandatory?e | Other specific features associated?f | Use of different prototypes? | Usability evaluated? | Routine use? | Evaluation of users’ compliance with eMedRec? | ||

| The PAML Builder | Poon, USA, 20061 | >3 | >3 | + | • | – | ≥2 | + | + | + | + | + | |||

| Turchin, USA, 20082,7 | >3 | >3 | + | ≥2 | + | + | + | ||||||||

| Schnipper, USA, 20092,8 | >3 | >3 | + | • | – | ≥2 | – | + | + | ||||||

| A tool within the EMR for MedRec after hospital discharge | Schnipper, USA, 201132 | >3 | 2 | + | ◉ | + | ≥2 | ◉ | + | + | + | + | + | ||

| MedRec after hospital discharge | Tamblyn, Canada, 20127 | >3 | >3 | + | • | + | + | ≥1 | + | – | – | – | – | ||

| MedRec application | Cadwallader, USA, 20132 | 2 | >3 | – | • | + | + | NA | + | + | + | – | – | ||

| Twinlist | Markowitz, USA, 20111,2 | 0/1 | 2 | – | ○ | + | NA | + | + | – | – | ||||

| Plaisant, USA, 20139 | 2 | 2 | – | ○ | + | + | NA | + | + | – | – | ||||

| APHID | Lesselroth, USA, 20092,4 | >3 | 2 | + | • | – | ≥2 | + | + | + | + | ||||

| Lesselroth, USA, 200911 | > 3 | > 3 | + | ◉ | – | ≥2 | – | + | + | ||||||

| Lesselroth, USA, 20112,5 | > 3 | 0/1 | + | • | – | + | + | + | – | ||||||

| Lesselroth, USA, 201210 | > 3 | 0/1 | + | • | – | – | + | – | |||||||

| Lesselroth, USA, 20142,6 (patent) | NA | >3 | NA | • | + | + | NA | + | NA | NA | NA | NA | |||

| A MedRec view within the EHR displaying two columns | Vawdrey, USA, 20102,9 | >3 | 2 | • | • | + | – | + | + | ||||||

| MedRec application launched from within the EHR | Bails, USA, 200830 | >3 | 2 | + | • | – | ≥2 | • | + | – | + | – | |||

| Electronic pathway for MedRec | Lovins, USA, 201131 | >3 | NA | + | •/◉ | + | + | NA | ◉ | + | + | + | + | ||

| The Discharge Instruction element | Sherer, USA, 201133 | >3 | 2 | + | •/◉ | + | + | ≥1 | ○ | – | + | + | + | ||

| Interactive Patient Med List | Tripoli, USA, 20143,4 | NA | >3 | NA | • | + | + | + | NA | + | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

APHID, Automated Patient History Intake Device; CPOE, computerized provider order entry; e-tool, electronic tool; EHR, electronic health record; eMedRec, electronic medication reconciliation; EMR, electronic medical record; IT, information technology; MedRec, medication reconciliation; NA, not applicable. PAML = PreAdmission Medication List Builder.

+ = YES; – = NO (as reported by the authors). An empty box = not reported by the authors.

aDescription of the context: >3 criteria, 2 criteria, 0/1 criteria: Size, location, or academic status; Financial status, or past IT experience; Information about culture, teamwork, and leadership; Existing external factors: for example, regulatory requirements, presence in the external environment of payments or penalties, such as pay-for-performance or public reporting.

bDescription of the tool: >3 criteria, 2 criteria, 0/1 criteria: different functionalities included; what/how the tool interfaces with the EMR; what is required for the consumer to operate it. Description items had to be sufficiently detailed so that it could be “replicated.”

cLinked to ≥3 other systems = •; Linked to 1 or 2 other systems = ◉; Not linked to any other systems = ○ (eg, CPOE, EMR, pharmacy claim).

dDescription of the implementation: number of components beyond “staff education”: ≥2, ≥1, 0. Possible components are: description of barriers and facilitators, audit and feedback, presence of “champions” (quality improvement leaders) responsible for implementation, assessment of impact on workflow, and tailoring/change management.

eMandatory = •; Reminder = ◉; Nothing = ○.

fOther specific features associated: review appropriateness of medication, post-discharge communication with patient, and or with other healthcare provider (by e-mail/printed list), possibility to reconcile only part of the medication list, decision support functionality (not specifically related to medication reconciliation), existing of different way of presenting medication regimen to the different users according to the needs of each (physician, patient, pharmacist), section for drug event report via e-mail.

Context of Development

Ten of the tools reported on were developed in the United States and one was developed in Canada.7 Except for the Interactive Patient Medication List,34 all the tools were developed in academic environments (ie, academic hospitals or universities). Tools were almost equally implemented at admission and discharge1,27–31,33 or in outpatient clinics.2,10,11,24,25,32 Five of these tools1,10,11,24,25,27,28,30,31,33 were reported as having been developed in hospitals promoting patient safety culture, four reports2,7,29,32 did not include information about this culture, and, for the two last tools, this criterion was not applicable.9,12,34 When patient safety culture was mentioned, the quality improvement team insisted on the need for interdisciplinarity or teamwork for developing and implementing eMedRec. One study highlighted the importance of the context of development.28 In that case, the intervention took place in two hospitals, and a statistically significant decrease in potential adverse drug events was reported in one of the two hospitals. The authors hypothesized that differences in context and implementation (level of publicity and nurses’ involvement) probably contributed to the differences observed.

Characteristics of the Tools

Seven1,7,10,11,24,25,27,28,30–33 of the tools reported on were integrated into the organization’s/clinicians’ workflow. All the tools, except the Twinlist,9,12 used electronic data from different sources, such as pharmacy claims data, electronic medical records, and computerized physician order entry (CPOE) to collect the medication history and identify discrepancies. Despite the fact that these characteristics are considered by the United States and Canadian toolkits as ideal features for eMedRec tools,14,19 only half2,7,9,12,26,31–34 of the 18 reports included in this study highlighted medication discrepancies, only 5 of the 18 reports2,9,31,33,34 offered various possibilities for organizing medication lists differently, and only 37,26,34 documented reasons for stopping medication (Table 2). Other functionalities were implemented in order to reduce the time needed to complete tasks and cognitive burden: displaying medication lists side-by-side2,7,9,12,29,33 and using different filters2,9,31,33,34 for sorting unreconciled medications. Additional functionalities to make the eMedRec process more efficient included gathering information from multiple sources;1,2,10,11,25,26,28–30,34 giving access to detailed information on prescribing, dispensing, etc.;7,34 communicating the reconciled medication list easily and quickly to other providers;7,24,34 linking decision support systems (eg, systems supporting decision to admit patients, supporting drug-drug interaction detection);34 and creating a link with an automatic input to the CPOE.25,30,34 Plaisant’s team9,12 also developed animations to help novices master the tool they reported on.

With regard to the availability of the tools on the market, Twinlist is available as an open-source program,9 the Discharge Instruction element is commercially available,33 and the APHID10,11,24–26 team is working on a prototype for a national enterprise deployment within the Veterans Health Administration. In addition, a few tools can be embedded in electronic health record (EHR) products such as CERNER,33 Eclipsy Sunrise EHR,29 and Siemens EHR.31 Finally, two additional tools will probably be commercially available in the next few years.7,34

Lesselroth’s team involved patients, considered as a group of specific users, in the MedRec process.10,11,24 Patients reviewed their composite list of medications with the eMedRec tool, using a kiosk situated in the lobby, and the program automatically charted patient response in the EHR. Cadwallader also planned to involve patients in this process.2

Implementation and Evaluation

To develop an eMedRec tool, most of the research teams used different prototypes with Plan-Do-Study-Act cycles to improve the tool and adapt it to users’ needs and to workflow (Table 2). These were classified as quality improvement projects (Table 1). Although teams explained that they needed several years to develop the tool before it was finally put into routine use, none mentioned the number of prototypes they developed to arrive at the final tools.

Due to the variability of the objectives recorded and to missing information, results were difficult to compare (Table 1). Nevertheless, the main measures of evaluation were related to usability,1,2,9,11,12,24,25,27,31–33 adherence to the tool,1,11,24,27–33 and user satisfaction.24,25,27,29,31–33

Usability was evaluated in different ways: time saved by clinicians,9,27,33 workflow improvement,11,31 ease of use,1,9,11,12,24,25,27 and understanding of the tool.9,24,25 In several quality improvement projects, usability issues that were identified led to the implementation of improvements in a revised prototype of the tool.

Regarding adherence, some authors1,28,30,32 looked at the number of patients with a medication list created or reconciled, while others measured the proportion of clinicians using the tool29,31 or the proportion of patients connecting to the tool.11,24 When tools were in routine use, several teams struggled with user adherence and therefore implemented specific incentives (Table 2). Three authors reported significant improvements in adherence after implementing a reminder31,32 or even a hard stop.29,30 Other steps taken in support of tool adoption included elaborating workflow models1,10,11,24,28 aimed at integrating the new e-tool in the most efficient way possible and defining the responsibilities1,7,10,11,24,28–30 of each actor. With regard to the impact of eMedRec on health outcomes, Schnipper reported that an eMedRec intervention significantly decreased the risk of potential adverse drug events.28 In her RCT protocol, Tamblyn has planned to measure adverse events, emergency visits, and hospital readmissions.7 Finally, Lesselroth will evaluate the impact of eMedRec on medication discrepancies.10

Recommendations for the Successful Development and Implementation of an eMedRec Tool

Because objectives varied considerably from one report to another, the authors of the reports included in this study arrived at a variety of conclusions. Nevertheless, each team produced a list of recommendations for the successful development and implementation of an eMedRec tool. These are summarized in Box 1.

Box 1.

Recommendations Made by Authors for the Successful Development and Implementation of eMedRec Tools

| Recommendations concerning the context of development |

|

| Recommendations concerning functionalities and development of the tool |

Concerning the tool in general

|

Gathering the best possible medication history

|

| Identification of discrepancies |

Resolving discrepancies

|

| Recommendations concerning the implementation of the tool |

|

CPOE, computerized physician order entry; EHR, electronic health record; EMR, electronic medical record; eMedRec, electronic medication reconciliation; IT, information technology; MedRec, medication reconciliation.

Discussion

Main Findings

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review of e-tools to support MedRec. We have identified 11 tools that support the entire MedRec process, 7 of which are in routine, daily use.1,10,11,24,25,27–33 This adds valuable information to recent literature reviews that identified a limited number of studies of IT support for MedRec. Most studies referred to e-tools that supported some, but not all, steps of the MedRec process.3,4 We mainly found quality improvement studies and observational effectiveness studies that showed positive results overall in terms of usability,1,2,9,11,12,24,25,27,31–33 satisfaction,24,25,27,29,31–33 and adherence.1,11,24,27–33 However, evidence remains insufficient about the impact of eMedRec tools on the quality and safety of healthcare.

Implications for Practice

Recent reports summarized the ideal features and functions an eMedRec tool should include.14,19 None of the tools identified seem to include (or to have described whether or how it included) all of these features and functions, but these manuals were published after all of the reports we identified.

Our data confirm that the success of developing and integrating technical solutions to support MedRec is strongly dependent on attention to implementation processes and extensive usability testing.

Implementation Processes

Successful eMedRec requires a concerted quality improvement effort, of which IT is but one component. To be embraced by most users, eMedRec tools need appropriate national and institutional environments. At the national level, all the tools identified were developed in the United States and Canada, where national campaigns and incentives have encouraged MedRec progress since 2005.35,36 Accordingly, the applicability of our results to other healthcare systems with different environments, cultures, and use of health IT, including those in Europe, cannot be guaranteed. Three studies carried out in Spain with one eMedRec tool have been published recently,18,37,38 but additional studies will need to be conducted in environments outside the United States and Canada.

At the institutional level, we found that endorsement by quality improvement leaders,1,25,30 highly integrated care, past experience of technology, and a culture of fostering patient safety enhanced the adoption of eMedRec into routine use. Persuading frontline users and improving awareness among clinicians of the importance of eMedRec (eg, by specific clinical vignettes) is essential to successful implementation.30 Staff education (eg, providing training on its use, educational handouts, or online materials) and on-site support were repeatedly recommended by researchers.

Despite favorable organizational cultures, institutions have struggled to reach user compliance rates above 50%.14,29,30,32 Additional measures that were reported to be helpful in increasing compliance were (1) workflow redesign1,25,27 and precise definitions of roles and responsibilities,24,27,30 (2) equipping the tools with reminders31,32 or hard-stop systems,29,30 and (3) reducing the time needed to reconcile medication.29 As with non-electronic processes, successfully implementing eMedRec requires multidisciplinary teamwork.31,39,40

Extensive Usability Testing

Usability testing is the most commonly used evaluation method for assessing user interactions with health IT. Clinical processes have to drive IT development and design.27 Usability tests ensure that clinicians and other healthcare professionals have an opportunity to evaluate and provide feedback on eMedRec systems’ functionality, usability, and workflow.14,25,27,30 Most reports evaluated some components of usability.1,2,9,11,12,24,25,27,31–33 Evaluations of Twinlist were unique in that they purposively evaluated cognitive support of MedRec through interface design.9 In an experimental study41 published after we carried out our systematic search, the authors found that Twinlist could significantly improve the performance and safety of MedRec tasks. Their results should certainly help other developers and researchers, including EHR vendors, improve their own design.

Applicability to Commercially Available Tools

Three of the eleven tools that were identified in the present review are available as an open-source program (Plaisant9) or commercially available (Vawdrey29 and Sherer33). Two additional tools are aiming to get into the market.7,26,34 Many other MedRec tools (either stand-alone or embedded in EHRs) are commercially available. Unfortunately, no eligible reports on these other tools were found by our search strategy. In order to explore the applicability of our results to these tools, we contacted 8 eMedRec software vendors referred to in the MARQUIS toolkit19 and 16 EMR vendors and asked them to provide information on their MedRec tools. Three reminders were sent. Seventeen vendors did not respond, and most responders did not want to share detailed information. In addition, we searched for information on the vendors’ websites.42–65 It seems that many tools are clearly integrated in the clinician’s workflow and tightly linked to CPOE and other decision support systems. Many vendors claim that users gain time and accuracy by using their MedRec tool. Nevertheless, information concerning the tool’s characteristics – such as automatically highlighting discrepancies, making it possible to document the reason for stopping/ modifying medication, offering different options for the organization of the medication list – was neither provided by vendors, nor found on their websites. At least nine EHRs had developed a patient portal,50–52,54,57,61–63,65 but patient input is apparently not used to inform the MedRec tool’s consolidated list (a synthesis table can be found in Supplementary Appendix III).

Implications for Research

As most of the tools reported on had only recently been implemented, the evaluations of these tools were mainly limited to measures of usability,1,2,9,11,12,24,25,27,31–33 user adherence,1,11,24,27–33 and satisfaction.24,25,27,29,31–33 We found only one RCT that evaluated the impact of eMedRec on clinical outcomes, namely potential adverse drug events.28

Future studies should correlate the specific features of MedRec tools to their efficacy in improving the identification and resolution of medication discrepancies. This could help with considering which features are the most important. Validated measures should be used to assess usability, such as the Questionnaire for User Interaction Satisfaction,66 and these measures should also be correlated to efficacy. Moreover, future research should evaluate – using rigorous and, if possible, multicentric designs22 – to what extent eMedRec is able to achieve the goal of improving patient safety and quality of care. A few such trials are currently ongoing.7,10

Outcome measures in future trials should include measures of adverse drug events and the number of unintentional medication discrepancies per patient. The latter measure has recently been endorsed by the United States National Quality Forum.67 Such outcomes, together with selected process data, are worth considering in a core dataset. In addition, risks potentially introduced by eMedRec, such as over-reliance on electronic medication lists and technology-induced errors, will need to be evaluated.

Quality of reporting should be improved. The present work has shown that many reports lack adequate information on the characteristics of the tools and of their implementation. Context, the characteristics of the tools, and implementation features all have an impact on effectiveness. Future researchers should carefully describe each component, and particular attention should be paid to describing features that have been listed as essential for the successful implementation of eMedRec.14,19

Further research should investigate the quality of MedRec modules in EHRs and the incremental benefits of add-on MedRec software integrated with these EHRs. However, it should be noted that research on this topic might be hampered by a lack of scientifically rigorous data in peer-reviewed journals or patent databases, by a lack of information due to confidentiality considerations, and by difficulties in implementing direct comparisons, because no hospital is going to adopt more than one EHR at once. However, before/after studies by hospitals adopting different tools might be informative, as might be multihospital comparisons of adjusted discrepancy rates in institutions that use different EHRs.

Increasing patient engagement as another strategy for enhancing eMedRec efficiency16 should be assessed by researchers. Patients can get involved, most often through patient portals, by providing their list of medications, by commenting on medication discrepancies between different lists, and by self-informing about nonadherence. For example, Siek et al.17,68 developed the Colorado Care Tablet, a Personal Health Application that older adults with limited computing experience (ie., a population for which obtaining the best possible medication history is especially challenging)17,37,40 could easily use. Except for the APHID tool,11,24 patient portal studies were excluded from the present review, due to the fact that portals were often not linked to an eMedRec tool or that description of the tool was lacking. From our viewpoint, patient portals remain an interesting way of involving patients and improving medication reconciliation,69 and such data could inform developers of future eMedRec tools.

Limitations

This systematic review has several limitations. First, it is likely that we missed some existing eMedRec tools, because we limited our selection to English-language reports, because we cannot exclude publication bias, and because eMedRec tools developed in countries other than the United States may not have been patented. In addition, the translation of our research query in the Embase database generated difficulties. Indeed, “emtree” (Embase controlled vocabulary) did not contain any specific term for “medication reconciliation” (it was translated as “medication therapy management”). Despite this, our search strategy was comprehensive and not limited to published full-text papers. In addition, we did not restrict our selection to experimental designs. This was certainly appropriate given the objectives of this review, and the data from ongoing quality improvement studies and observations studies were valuable. Second, we had to exclude possibly interesting reports due to absent or incomplete data on the tools they described. Efforts were made to collect additional data from proceedings – some requests were successful but others were not. We did not attempt to collect additional data from authors of full-text papers with no data on the tool. Third, to be included, eMedRec tools had to support the entire MedRec process; this decision was taken for reasons of homogeneity and because we considered it to be an essential feature of eMedRec tools. However, several reports on tools that support some, but not all, steps of the MedRec process have generated some useful data. For example, Agrawal et al. developed an eMedRec system for use on admission to an acute care hospital.39,70,71 Even though resolving discrepancies was not performed electronically, they reported a substantial reduction in medication errors, and the lessons learned from their experience were later used by many other research teams. More recently, Heyworth et al. found that enabling patients to conduct MedRec through a web portal was feasible during the transition from inpatient to outpatient care.72

Conclusion

The transition is under way from paper to eMedRec,14 and the proportion of healthcare organizations using a fully electronic system for MedRec-related activities is expected to increase in the future. E-tools that support the entire MedRec process have been developed and evaluated. In addition to the functionalities of the tools, context and implementation must be carefully considered in order to maximize adherence and effectiveness, and should be more thoroughly reported. Evidence from rigorous studies is needed to evaluate the effect of eMedRec on the quality and safety of healthcare.

Contributors

S.M. and B.K. had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design: All authors. Acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data: All authors. Drafting of the manuscript: S.M. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors. Final approval of the version to be published: All authors. Obtained funding: A.S. Administrative, technical, and material support: S.M., A.S. Study supervision: A.S.

Funding

This work was supported by the Région wallonne WBHealth program Grant 1318069 (principal investigator: A.S.). The funding source had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Competing interests

None.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We acknowledge the contributions of Blake J. Lesselroth, MD MBI FACP, Associate Professor of Medicine & Informatics, Veterans Affairs Portland Healthcare System Oregon Health Sciences University, for his precious and valuable help to gahter information concerning commercially EHR vendors and for his unpublished data; Christine Lanners, Post-graduate, Information Sciences Expert, Deputy Manager, Lecturer, Scientific Logistics/Libraries of the Université Catholique de Louvain/Library of Health Sciences, for assistance with the elaboration of the research query in PubMed; Caroline Closset, Graduate Librarian, Scientific Logistics/Libraries of the Université Catholique de Louvain/Library of Health Sciences, and Delphine Legrand, Bsc, PhD, Université Catholique de Louvain, Louvain Drug Research Institute, Clinical Pharmacy Research Group, for their support in retrieving full-text articles; Philippe d’Antuono, Doctor of Chemical Sciences, Advisor in Intellectual Property at PICARRE between October 2009 and June 2015 and Patent Engineer at CMI Group since June 2015, for searching the patent databases; Jonathan Lovins, MD, SFHM, Associate Chief Medical Informatics Officer, Duke Regional Hospital, Physician, Hospital Medicine, Duke University Health System, Maestrocare Inpatient Physician Champion, Duke University Health System, Assistant Professor of Medicine, Duke University; Julie Cooper, PharmD, BCPS, AQ – Cardiology, Cone Health, Clinical Pharmacist, Program Director, Cardiology Pharmacy Residency, Adjunct Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Practice Advancement and Clinical Education, UNC Eschelman School of Pharmacy; Dominique Comer, PharmD, MS, Value Institute, Christiana Care Health System; Timothy Holahan DO, Clinical Instructor of Medicine, Geriatric Medicine/Palliative Care, University of Rochester Medical Center, Highland Hospital, Highlands at Brighton Transitional Care Facility; Silke Lim, MD, Pharmacy Specialist in Hospital Pharmacy, Kantonsspital Aarau AG (Zwitserland); Allen R. Huang, MDCM, FRCPC, FACP, Chief, Division of Geriatric Medicine, University of Ottawa and The Ottawa Hospital; Mac McKinsey, Director of Communications, Greenway Health; Melanie Bent, Product Management Senior Team, Greenway Health; and Brian C. Elswick, Digital Marketing Coordinator, Greenway Health, for their precious collaboration and the unpublished data and comprehensive information they provided. None of those named received financial compensation.

REFERENCES

- 1. Poon EG, Blumenfeld B, Hamann C, et al. Design and implementation of an application and associated services to support interdisciplinary medication reconciliation efforts at an integrated healthcare delivery network. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2006;13(6):581–592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cadwallader J, Spry K, Morea J, Russ AL, Duke J, Weiner M. Design of a medication reconciliation application: facilitating clinician-focused decision making with data from multiple sources. Appl Clin Inform. 2013;4(1): 110–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bassi J, Lau F, Bardal S. Use of information technology in medication reconciliation: a scoping review. Ann Pharmacotherapy. 2010; 44(5):885–897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mueller SK, Sponsler KC, Kripalani S, Schnipper JL. Hospital-based medication reconciliation practices: a systematic review. Arch Int Med. 2012;172(14):1057–1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kwan JL, Lo L, Sampson M, Shojania KG. Medication reconciliation during transitions of care as a patient safety strategy: a systematic review. Ann Int Med. 2013;158(5 Pt 2):397–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Coleman EA, Smith JD, Raha D, Min SJ. Posthospital medication discrepancies: prevalence and contributing factors. Arch Int Med. 2005;165(16): 1842–1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tamblyn R, Huang AR, Meguerditchian AN, et al. Using novel Canadian resources to improve medication reconciliation at discharge: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2012;13:150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.The Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. Medication Safety. Medication Reconciliation. http://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/our-work/medication-safety/medication-reconciliation. Accessed November 24, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Plaisant C, Chao T, Wu J, et al. Twinlist: novel user interface designs for medication reconciliation. AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings/AMIA Symposium AMIA Symposium. 2013;2013:1150–1159. Videos can be viewed on the project webpage http://www.cs.umd.edu/hcil/sharp/twinlist. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lesselroth BJ, Dorr DA, Adams K, et al. Medication review software to improve the accuracy of outpatient medication histories: protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Human Factors Ergonomics in Manufacturing & Service Industries. 2012;22(1):72–86. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lesselroth B, Adams S, Felder R, et al. Using consumer-based kiosk technology to improve and standardize medication reconciliation in a specialty care setting. Joint Comm J Qual Patient Safety/Joint Comm Resources. 2009;35(5):264–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Markowitz E, Bernstam EV, Herskovic J, et al. Medication reconciliation: work domain ontology, prototype development, and a predictive model. AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings/AMIA Symposium AMIA Symposium. 2011;2011:878–887. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kushniruk AW, Santos SL, Pourakis G, Nebeker JR, Boockvar KS. Cognitive analysis of a medication reconciliation tool: applying laboratory and naturalistic approaches to system evaluation. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2011;164:203–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. The Electronic Medication Reconciliation Group. Paper to Electronic MedRec Implementation Toolkit. ISMP Canada and Canadian Patient Safety Institute, 2014.

- 15. Porcelli PJ, Waitman LR, Brown SH. A review of medication reconciliation issues and experiences with clinical staff and information systems. Appl Clin Inform. 2010;1(4):442–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Monkman H, Borycki EM, Kushniruk AW, Kuo MH. Exploring the contextual and human factors of electronic medication reconciliation research: a scoping review. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2013;194:166–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Siek KA, Khan DU, Ross SE, Haverhals LM, Meyers J, Cali SR. Designing a personal health application for older adults to manage medications: a comprehensive case study. J Med Syst. 2011;35(5):1099–1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gimenez Manzorro A, Zoni AC, Rodriguez Rieiro C, et al. Developing a programme for medication reconciliation at the time of admission into hospital. Int J Clin Pharmacy. 2011;33(4):603–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mueller SK, Kripalani S, Stein J, et al. A toolkit to disseminate best practices in inpatient medication reconciliation: multi-center medication reconciliation quality improvement study (MARQUIS). Jt Comm J Qual Patient Safety/Jt Comm Resources. 2013;39(8):371–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC). Data collection form. EPOC Resources for review authors. Oslo: Norwegian Knowledge Center for the Health Services 2013; http://epoc.cochrane.org/epoc-specific-resources-review-authors. Accessed October, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Goldzweig CL, Orshansky G, Paige NM, et al. Electronic patient portals: evidence on health outcomes, satisfaction, efficiency, and attitudes: a systematic review. Ann Int Med. 2013;159(10):677–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Portela MC, Pronovost PJ, Woodcock T, Carter P, Dixon-Woods M. How to study improvement interventions: a brief overview of possible study types. BMJ Qual Safety. 2015;24(5):325–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Shekelle P, Pronovost P, Wachter R. Assessing the evidence for context-sensitive effectiveness and safety of patient safety practices: developing criteria. AHRQ Publication 2010;11-0006-EF. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lesselroth BJ, Felder RS, Adams SM, et al. Design and implementation of a medication reconciliation kiosk: the Automated Patient History Intake Device (APHID). J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2009;16(3):300–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lesselroth BJ, Holahan PJ, Adams K, et al. Primary care provider perceptions and use of a novel medication reconciliation technology. Inform Primary Care. 2011;19(2):105–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lesselroth B, Felder R, Adams S, Cauthers P, Wong GJ. System and method for automated patient history intake. Patent Application Publication 2014. US Department Veterans Affairs, Baltimore, MD (US) - US2014122129 (A1). [Google Scholar]

- 27. Turchin A, Hamann C, Schnipper JL, et al. Evaluation of an inpatient computerized medication reconciliation system. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2008;15(4): 449–452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Schnipper JL, Hamann C, Ndumele CD, et al. Effect of an electronic medication reconciliation application and process redesign on potential adverse drug events: a cluster-randomized trial. Arch Int Med. 2009;169(8): 771–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Vawdrey DK, Chang N, Compton A, Tiase V, Hripcsak G. Impact of electronic medication reconciliation at hospital admission on clinician workflow. AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings/AMIA Symposium AMIA Symposium. 2010;2010:822–826. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bails D, Clayton K, Roy K, Cantor MN. Implementing online medication reconciliation at a large academic medical center. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Safety/Jt Comm Resources. 2008;34(9):499–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lovins J, Beavers R, Lineberger R. Improving quality, efficiency, and patient/ provider satisfaction with electronic medication reconciliation and discharge instructions [abstract]. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(4):S121. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Schnipper JL, Liang CL, Hamann C, et al. Development of a tool within the electronic medical record to facilitate medication reconciliation after hospital discharge. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2011;18(3):309–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sherer AP, Cooper JB. Electronic medication reconciliation: a new prescription for the medications matching headache [abstract]. Heart Lung. 2011;40(4):372–373. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tripoli LC. Interactive patient medication list. Patent Application Publication 2013. MedImpact Healthcare Systems, Inc., San Diego, CA (US) - US2013304500 (A1). [Google Scholar]

- 35. US Department of Health & Human Services, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Patient Safety Network. Medication Reconciliation. http://psnet.ahrq.gov/primer.aspx?primerID=1. Accessed June 26, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Accreditation Canada, Canadian Institute for Health Information, Canadian Patient Safety Institute, ISMP Canada. Medication Reconciliation in Canada. Raising the Bar. 2012. https://www.accreditation.ca/sites/default/files/med-rec-en.pdf. Assessed February 10, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gimenez-Manzorro A, Romero-Jimenez RM, Calleja-Hernandez MA, Pla-Mestre R, Munoz-Calero A, Sanjurjo-Saez M. Effectiveness of an electronic tool for medication reconciliation in a general surgery department. Int J Clin Pharmacy. 2015;37(1):159–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zoni AC, Duran Garcia ME, Jimenez Munoz AB, Salomon Perez R, Martin P, Herranz Alonso A. The impact of medication reconciliation program at admission in an internal medicine department. Eur J Int Med. 2012;23(8):696–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Agrawal A. Medication errors: prevention using information technology systems. Brit J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;67(6):681–686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gleason KM, McDaniel MR, Feinglass J, et al. Results of the medications at transitions and clinical handoffs (MATCH) study: an analysis of medication reconciliation errors and risk factors at hospital admission. J General Int Med. 2010;25(5):441–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Plaisant C, Wu J, Hettinger AZ, Powsner S, Shneiderman B. Novel user interface design for medication reconciliation: an evaluation of Twinlist. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2015;22(2):340–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. First Databank. FDB MedsTracker MedRec. http://www.fdbhealth.com/solutions/fdb-medstracker-medrec. Accessed December 3, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mediware. State of Michigan Licenses Mediware Medication Management Products for 5 Behavioral Health Hospitals. Mediware/News [eNews]. March 1, 2010. http://www.mediware.com/news/state-of-michigan-licenses-mediware-medication-management-products-for-5-behavioral-health-hospitals. Accessed December 3, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mediware. Mediware Launches Automated Medication Reconciliation Product. Mediware/News [eNews]. May 8, 2007. http://www.mediware.com/news/mediware-launches-automated-medication-reconciliation-product. Accessed December 3, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Elsevier. ExitMeds®. Elsevier's ExitCare, Print Solutions, Medication Management. http://exitcare.com/solutions/print-solutions/medication-management-exitmeds. Accessed December 3, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 46. DrFirst. RcopiaAC. http://www.drfirst.com/products/rcopia/rcopiaac-hospitals. Accessed December 3, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 47. IATRIC Systems. Medication Reconciliation Checklist. 2012. http://docs.iatric.com/hs-fs/hub/395219/file-2543905030-pdf/Documents/IatricMedicationReconciliationChecklist.pdf?t=1449158343541. Accessed December 3, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Health Care Systems. Medication Reconciliation Overview. http://www.hcsinc.net/HCS-Medication-Reconciliation/med-rec-overview.html. Accessed December 3, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Staywell. Krames Exit-Writer®. http://staywell.com/patient-education/krames-exit-writer. Accessed December 3, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 50. EpicCare. Inpatient Clinical System. http://www.epic.com/software-inpatient.php. Accessed December 3, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Cerner Corporation. Cerner Medication History and Cerner Clinical Consulting. http://www.cerner.com/medication_history, http://www.cerner.com/page.aspx?pageid=17179878250&libID=17179878459. Accessed December 3, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 52. MediTech. The Key to Reducing Readmissions? Coordinated Care Transitions and the MEDITECH HER. March 5, 2015. https://ehr.meditech.com/news/the-key-to-reducing-readmissions-coordinated-care-transitions-and-the-meditech-ehr. Accessed December 3, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 53. GE Healthcare. http://www.gehealthcare.com/en. Accessed December 3, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 54. NextGen HealthCare. Ten reasons we are your best EHR choice for better results. Flexibility to match your needs; not the other way around. https://www.nextgen.com/Products-and-Services/Ambulatory/Electronic-Health-Records-EHR. Accessed December 3, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Daiker P. Medication Reconciliation Forms: Automatic, Comprehensive and Compliant. Medhost. http://www.medhost.com/news-and-events/medhost-minute/mm-medication-reconciliation-forms-automatic-compre. 2013. Accessed December 3, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Optum. Preventing Patient Rebounds. 2013. https://www.optum.com/content/dam/optum/resources/whitePapers/ReadmissionPrevention_WhitePaper_Online_FINAL.pdf. Accessed December 3, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Healthland. About Us. EHR Partners. http://www.healthland.com/about_us/partners/ehr_partners. Accessed December 3, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Siemens. Healthcare. http://www.siemens.com/entry/cc/en/#product/188200/227740. Accessed December 3, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Trubridge. Clinical Consulting Services. http://www.trubridge.com/consulting-services/clinical-consulting-services. Accessed December 3, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 60. eClinicalWorks. https://www.eclinicalworks.com. Accessed December 3, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Greenway Health. EHR & Practice Management. http://www.greenwayhealth.com/solution/electronic-health-record-practice-management. Accessed December 3, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Quest Diagnostics. Technology Solutions & Care360. http://www.questdiagnostics.com/home/physicians/technology.html. Accessed December 3, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 63. AllScripts. Health Care Systems HCS Medication Reconciliation. https://allscripts-store.prod.iapps.com/applications/id-13008/HCS_Medication_Reconciliation. Accessed December 3, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 64. Indian Health Service. Medication Reconciliation. http://www.ihs.gov/ehr/medicationreconciliation. Accessed December 3, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 65. McKesson. Medication Reconciliation Solution from RelayHealth Helps to Address Patient Safety in Emergency Rooms Across the Nation. August 13, 2007. http://www.mckesson.com/about-mckesson/newsroom/press-releases/2007/medication-reconciliation-solution-from-relayhealth-helps-to-address-patient-safety-in-emergency-rooms-across-the-nation. Accessed December 3, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 66. Human-Computer Interaction Lab (HCIL) at the University of Maryland at College Park. Questionnaire for User Interaction Satisfaction. 2016. http://lap.umd.edu/quis. Accessed January 27, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 67. US National Quality Forum. NQF Endorsed Standard. Measure Steward: Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Medication Reconciliation: Number of Unintentional Medication Discrepancies per Patient. NQF#2456. Updated September 9, 2014. http://www.qualityforum.org/QPS/QPSTool.aspx#qps PageState=% 7B% 22TabType% 22% 3A1,% 22TabContentType% 22% 3A2, % 22 SearchCriteriaForStandard% 22% 3A% 7B% 22TaxonomyIDs% 22% 3A% 5B% 5D,% 22SelectedTypeAheadFilterOption% 22% 3A% 7B% 22ID% 22% 3 A2 456,% 22FilterOptionLabel% 22% 3A% 222456% 22, % 22Type OfType Ahe ad FilterOption% 22% 3A4,% 22TaxonomyId% 22% 3A0% 7D,% 22Keyword% 22% 3A% 222456% 22,% 22PageSize% 22% 3A% 2225% 22,% 22OrderType% 22% 3A3,% 22OrderBy% 22% 3A% 22ASC% 22,% 22PageNo% 22% 3A1,% 22IsExactMatch% 22% 3Afalse,% 22QueryStringType% 22% 3A% 22% 22,% 22ProjectActivityId% 22% 3A% 220% 22,% 22FederalProgramYear% 22% 3A% 220% 22,% 22FederalFiscalYear% 22% 3A% 220% 22,% 22FilterTypes% 22% 3A2% 7D,% 22SearchCriteriaForForPortfolio% 22% 3A% 7B% 22Tags% 22% 3A% 5B% 5D,% 22FilterTypes% 22% 3A0,% 22PageStartIndex% 22% 3A1,% 22PageEndIndex% 22% 3A25,% 22PageNumber% 22% 3Anull,% 22PageSize% 22% 3A% 2225% 22,% 22SortBy% 22% 3A% 22Title% 22,% 22SortOrder% 22% 3A% 22ASC% 22,% 22SearchTerm% 22% 3A% 22% 22% 7D,% 22ItemsToCompare% 22% 3A% 5B% 5D,% 22SelectedStandardIdList% 22% 3A% 5B% 5D,% 22StandardID% 22% 3A2456,% 22EntityTypeID% 22% 3A1% 7D. Accessed November 18, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 68. Siek KA, Ross SE, Khan DU, Haverhals LM, Cali SR, Meyers J. Colorado Care Tablet: the design of an interoperable Personal Health Application to help older adults with multimorbidity manage their medications. J Biomed Inform. 2010;43(5 Suppl):S22–S26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Schnipper JL, Gandhi TK, Wald JS, et al. Design and implementation of a web-based patient portal linked to an electronic health record designed to improve medication safety: the Patient Gateway medications module. Inform Primary Care. 2008;16(2):147–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Agrawal A, Wu W, Khachewatsky I. Evaluation of an electronic medication reconciliation system in inpatient setting in an acute care hospital. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2007;129(Pt 2):1027–1031. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Agrawal A, Wu WY. Reducing medication errors and improving systems reliability using an electronic medication reconciliation system. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Safety/Jt Comm Resources. 2009;35(2):106–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Heyworth L, Paquin AM, Clark J, et al. Engaging patients in medication reconciliation via a patient portal following hospital discharge. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014;21(e1):e157–e162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.