Abstract

Objectives

To quantify the social burden among Japanese migraine patients in the context of currently available migraine treatments, by comparison with non-migraine controls, and comparison of migraine patients currently taking prescription medication versus not taking prescription medication.

Design

Cross-sectional analysis.

Setting

Data from the population-based online self-administered Japan National Health and Wellness Survey (NHWS) 2017.

Participants

Respondents to the NHWS (n=30 001) were ≥18 years. Migraine patients were respondents with self-reported experience and physician diagnosis of migraine. Non-migraine controls reported no migraine experience. Migraine patients were subgrouped into currently taking prescription medication for migraine (Rx) and currently not taking prescription medication (non-Rx).

Methods

One-way analysis of variance tests were performed to compare health-related quality of life (HRQoL), work productivity and activity impairment and healthcare resource utilisation between migraine patients and matched non-migraine controls selected by 1:1 propensity score matching. Generalised linear models were used to compare outcomes and migraine related characteristics between Rx and non-Rx.

Results

Compared with matched controls, migraine patients (n=1265) had significantly lower HRQoL in terms of lower Physical Component Summary (48.36 vs 51.29, p<0.001), Mental Component Summary (44.65 vs 48.31, p<0.001), Role/Social Component Summary (41.78 vs 46.18, p<0.001) and mean EuroQol 5-Dimension index (0.77 vs 0.86, p<0.001) scores. Migraine patients experienced significantly higher absenteeism (6.95% vs 3.07%, p<0.001), presenteeism (32.73% vs 18.94%, p<0.001), work productivity loss (34.82% vs 20.03%, p<0.001) and daily activity impairment (35.70% vs 22.04%, p<0.001) and visited healthcare professionals more often (8.38 vs 4.57, p<0.001) than controls. No significant differences in these outcomes were found when comparing Rx (n=587) and non-Rx (n=678) patients.

Conclusions

There is an unmet need for improved HRQoL and work productivity in Japanese migraine patients despite the currently available prescription medications, which are important factors to consider for future development of migraine therapies.

Keywords: migraine, public health, health economics

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The recruitment of respondents to the Japan 2017 National Health and Wellness Survey (NHWS) used a stratified random sampling procedure with strata by sex and age according to national census data, thereby ensuring that the demographic composition of the sample was representative of the adult population in Japan.

This study used the validated instruments Short Form-12 version 2, EuroQol-5 Dimension, Work Productivity and Activity Impairment questionnaire to quantify the burden of migraine and Headache Impact Test for assessment of headache-related disability.

The data from NHWS are cross-sectional and no causal relationships can be assumed.

As all data are self-reported, no verification of patient-reported outcomes was conducted, and data are subject to recall bias.

Although NHWS is broadly representative of the Japanese adult population, it is unclear the extent to which the migraine patients and migraine patients taking Rx are representative of the larger population.

Introduction

Migraine is a common disabling headache disorder, known to impose a burden on both patients and societies worldwide.1–3 Since 1990, migraine has been the second leading cause of years lived with disability and the sixth most prevalent disease.4 Globally, the prevalence of migraine has been estimated to be 11.6%, and in Asia 10.1%.5 The 1-year prevalence of migraine among adults in East Asia ranged from 6.0% to 14.3%.6 In Japan, the prevalence has been estimated to be between 6.0% and 8.9%, with the 1-year prevalence among non-elderly adults reported at 6.0%.6–9

A recent study of European migraine patients showed that suffering from at least 4 monthly headache days (MHDs) was associated with poorer health-related quality of life (HRQoL), high healthcare resource utilisations (HCRU) and loss of work productivity compared with non-migraine controls.1 In another study among migraine patients with at least 4 MHDs and had failed at least one preventive migraine treatment, impact of migraine on professional, private and social domains were reported by 70%, 64% and 78% of the respondents, respectively.10 Migraine was also reported to be associated with a high economic burden, with annual direct cost of chronic migraine substantially higher than that of episodic migraine.11 In Japan, previous studies have also reported an incremental impact of migraine on patients’ social life and work. In a nationwide survey from 1997, 30% of migraine patients reported a severe impairment of their daily activities where bed rest was frequently required. Furthermore, 32% of migraine patients reported moderate to severe impairment in social activities including cancellation of work and daily appointments.7 Similarly, in the regional Daisen study from 1999, 20.3% of migraine patients reported that they had experienced time or days off from work and 27.3% reported being unable to do housework.8 The general health perception was worse compared with non-headache subjects, as migraine patients more often reported their health as ‘poor’ and half of the patients suffered from sleep disturbance.8 Despite the disabling impact of migraine, both surveys revealed large populations of underdiagnosed and undertreated migraine patients. More than 60% of patients had never consulted a physician for headache, as few as 5%–7% of patients continuously consulted a physician for migraine,7 8 and only 11.6% of patients were aware that their headache was migraine.7 8 Further studies have investigated the impact of migraine on the active Japanese workforce, which found that 22.4% of migraineurs had missed work due to headaches several times in the past year.9 Additionally, migraine and headaches were the leading causes of absence from work (absenteeism) for employed women in their 50s (6.2 days of absence, 4 weeks recall period), and the leading cause of not being able to fully perform while at work (presenteeism) for employed men in their 20s with 49.5 hours lost in the last 4 weeks.12

With these most recent studies of migraine burden performed in 20089 and 2013,12 there has been a paucity in research and there is a need for updated data to gain further insights and understand the current burden of migraine in Japan, in the context of currently available treatments. Therefore, the objective of this study was to quantify the migraine associated burden by comparison of HRQoL, work productivity and activity impairment (WPAI) and HCRU in migraine patients and people without migraine experience, and among the treated migraine population versus non-treated migraine population.

Methods

This research was a cross-sectional study using data from the National Health and Wellness Survey (NHWS) conducted in 2017. NHWS is an online self-administered survey and was granted exemption status upon review by Pearl International Review Board (Indianapolis, Indiana, USA). All respondents provided informed consent prior to participating.

Study population

Respondents to the NHWS were aged 18 years or older and were recruited from web-based opt-in consumer panels. Respondents were already members of these panels, recruited through opt-in emails, coregistration with panel partners, newsletter campaigns, banner placements and had provided informed consent prior to participation. Recruitment of NHWS respondents used a stratified random sampling procedure, with strata by sex and age according to census data from the US census database which sources from the Japan Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications,13 which was implemented to ensure that the demographic composition of the sample was representative of the Japan adult population. Representation of NHWS data has been validated and weighted against reliable sources including government agencies’ health statistics and unaffiliated third parties.14 15

Respondents who self-reported a physician diagnosis of migraine were included in the migraine patient group. Those who self-reported no experience of migraine were the non-migraine controls. Respondents with self-reported physician diagnosis of migraine were further subgrouped into patients who reported currently taking prescription medication for migraine (Rx) and patients currently not taking any prescription medication (non-Rx).

Patient involvement

Patients and respondents to NHWS were not involved in setting the research questions, outcomes measures nor the design of the study. The data used in this study were obtained from patients and respondents who provided self-reported information in the NHWS.

Measures

Covariates

The demographic and general health characteristics included: gender, age, marital status, number of children living in the household, household income, employment status, smoking status, alcohol use, exercise behaviour and Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI).16–18

Measures

HRQoL was assessed by the Short Form-12 health survey version 2 (SF-12v2),19 which consists of 12 questions with summary scores that was translated and validated for use in the Japanese population.20 21 The Mental Component Summary (MCS) score, Physical Component Summary (PCS) score and Role/Social Component Summary (RCS) score were calculated based on survey responses. Each domain and summary score was calculated using a norm-based scoring algorithm which allows for all measures to be viewed together on the same graph and allows for scores to be interpreted relative to population means. Higher scores indicate better quality of life.

Health state utilities were quantified with the EuroQol 5-Dimension 5 Levels (EQ-5D 5L) instrument, which is a standardised measure of health status to provide a simple, generic measure of health.22 EQ-5D index score is a single summary index derived from the EQ-5D 5 L questions,23 scored by using the Japanese tariff. Higher scores indicate better health status. In addition, the EQ Visual Analogue Scale (EQ VAS) was used which records the patient’s self-rated health on a 100 mm VAS, where the endpoints are labelled ‘The best health you can imagine’ (100) and ‘The worst health you can imagine’ (0). The VAS can be used as a quantitative measure of health outcome that reflect the patient’s own judgement.

For work productivity assessment, the WPAI questionnaire24 was used to measure the impact of health on both employment-related and daily activities. This six-item validated instrument consists of four metrics: absenteeism (the percentage of work time missed because of one’s health in the past 7 days), presenteeism (the percentage of impairment experienced because of one’s health while at work in the past 7 days), overall work productivity loss (an overall impairment estimate that is a combination of absenteeism and presenteeism), and daily activity impairment (the percentage of impairment in daily activities because of one’s health in the past 7 days). These four subscales are generated in the form of percentages, with higher values indicating greater impairment. Only respondents who reported being full-time, part-time or self-employed provide data for absenteeism, presenteeism and overall work impairment. All respondents provide data for activity impairment.

HCRU was considered in terms of the number of outpatient visits in the past 6 months to healthcare providers (practitioner/family practitioners, internists and dentists as well as more specialised physicians), the emergency room (ER) and the hospitalisation for the participant’s own medical condition.

Respondents with migraine used the validated Headache Impact Test (HIT-6) scale for assessment of headache-related disability.25 Scores from HIT-6 range from 36 to 78. A higher HIT-6 score indicates a greater impact of headache on the daily life of respondents.

Migraine-specific characteristics and treatment

All migraine patients were asked several questions in relation to their migraine including the symptoms experienced due to migraine, number of years experiencing migraine, diagnosing physician, number of migraines in the past 30 days and in the past 6 months, number of headache days in the past 30 days, experienced migraine related to menstrual cycle, days of missed work due to migraine in the past 6 months, days of missed household activities due to migraine in the past 6 months, current use of prescription medication (Rx) to treat or prevent migraine, and usage of over-the-counter (OTC) or herbal products to treat migraine. Respondents specified the type of Rx which included the following drug classes: triptan, anticonvulsant, beta blocker, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and others. The top 10 self-reported OTC and herbal products contained the following active ingredients: loxoprofen, aspirin, ibuprofen, acetaminophen, chondroitin and ergotamine. In addition, respondents with migraine answered the validated HIT-6 scale for assessment of headache-related disability.25

Statistical analysis

Demographic factors and general health characteristics were compared between migraine patients and non-migraine controls to understand the baseline differences in the two groups. Demographic factors, general health characteristics and migraine-specific variables were summarised descriptively among migraine patients. Age, CCI, gender, employment status, household income, smoking status, and alcohol use were used in the 1:1 propensity score matching using a greedy matching algorithm to form the matched non-migraine control group. Post-matching bivariate comparisons were conducted between migraine patients and matched non-migraine respondents to assess the balance of the matching. After propensity score matching, outcomes were compared between patients with migraine and matched non-migraine controls. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests were used for comparison of these continuous outcome variables.

Demographic factors, general health characteristics, migraine-specific variables (including migraine-related symptoms) were also compared between migraine patients currently taking Rx and not currently taking Rx, using χ2 test for categorical variables and one-way ANOVA for continuous variables. Generalised linear models (GLMs) were used to compare the outcomes between migraine patients currently taking Rx and migraine patients currently not taking Rx, accounting for demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients. Normal distribution with identity link were specified in the GLMs for normally distributed outcomes, such as HRQoL scores. Negative binomial distribution with log link was specified for outcomes with skewed distributions, such as WPAI and HCRU. Estimated adjusted means and p values were reported for each health outcome. All outcome variables were predetermined before the analyses and the analyses were not of exploratory manner. No correction for multiple testing was conducted for this study. Complete data were available, and no imputation was carried out. For all analyses, statistical significance was assessed at a significance level of 0.05. All data analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics Version 2226 and R Version 3.4.4.27

Results

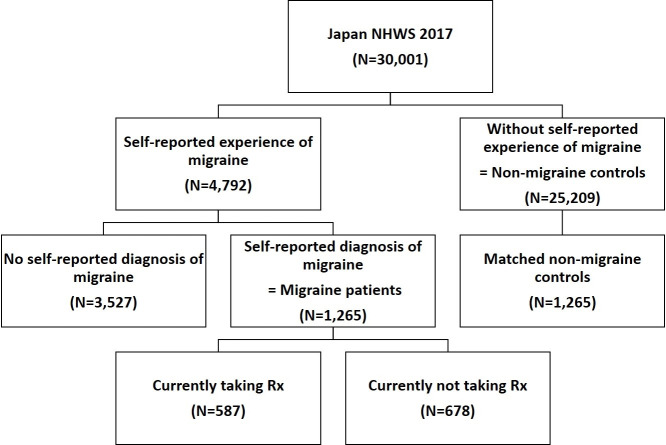

A total of 25 209 respondents without self-reported experience with migraine were included in the non-migraine group and 4792 respondents self-reported experience with migraine (figure 1). Among the 4792 respondents who self-reported experience with migraine, 74% (n=3527) had never been diagnosed by a physician. The 1265 respondents with self-reported physician diagnosed migraine were included in the migraine patient group for the further analyses.

Figure 1.

Respondent flow chart. NHWS, National Health and Wellness Survey; Rx, prescription medication.

On average, migraine patients tend to be younger than non-migraine respondents (43.8 vs 52.8 years, p<0.001) and have a significantly higher CCI (0.24 vs 0.17, p<0.001) (see online supplemental table 1). More migraine patients are female (66.6% vs 47.1%, p<0.001), currently employed (59.8% vs 54.7%, p<0.001) and have children in the household (27.7% vs 18.6% p<0.001). Compared with controls, fewer migraine patients are married/living with partner (53.1% vs 62.5%, p<0.001) and have completed university (42.5% vs 49.2%, p<0.001). Migraine patients have similar household income to non-migraine respondents. A slightly higher percentage of migraine patients currently smoke (44.0% vs 41.2%, p=0.046) compared with non-migraine respondents, but slightly fewer migraine patients currently consume alcohol (63.2% vs 66.2%, p=0.031). Detailed results are listed in online supplemental table 1).

bmjopen-2020-038987supp001.pdf (75.5KB, pdf)

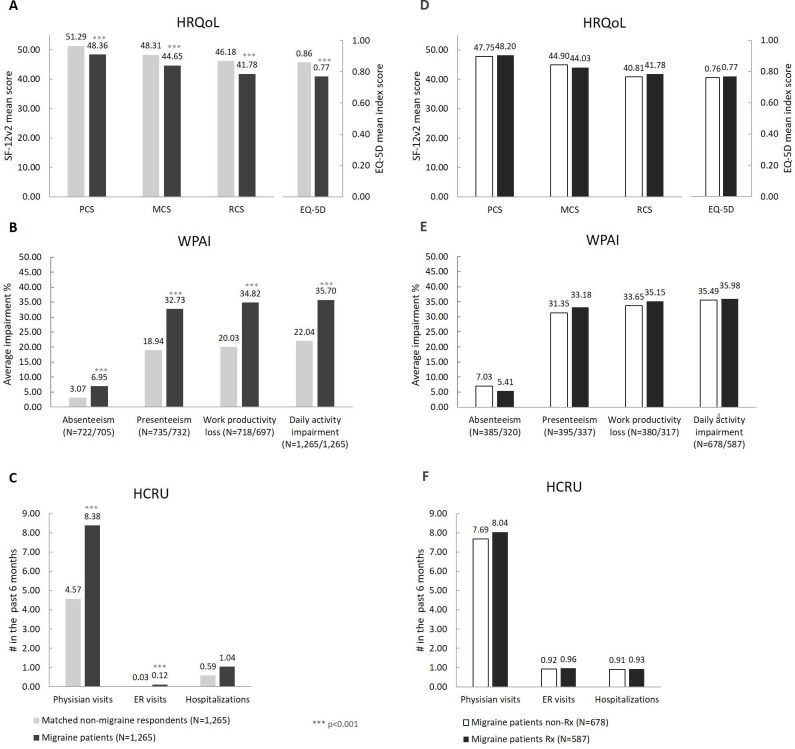

Comparison of outcomes in migraine patients versus matched non-migraine controls

After 1:1 propensity score matching, the majority of demographic and clinical characteristics were balanced between migraine patients and matched non-migraine controls (see online supplemental table 1). Bivariate comparison between matched non-migraine controls and migraine patients were conducted to evaluate the burden of migraine in terms of HRQoL, WPAI and HCRU (figure 2). We found that migraine patients had significantly lower PCS (48.36 vs 51.29, p<0.001), MCS (44.65 vs 48.31, p<0.001) and RCS (41.78 vs 46.18, p<0.001) scores as well as significantly lower EQ-5D index (0.77 vs 0.86, p<0.001) and EQ-5D VAS (64.41 vs 73.49, p<0.001) scores. The differences in MCS and RCS between the two groups were more than 3 points, which is defined as a minimum clinically important difference28 (figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Comparison of health outcomes between migraine patients and matched non-migraine respondents (A–C), and between migraine patients currently taking Rx and not currently taking Rx (D–F). (A–C) Migraine patients and matched non-migraine respondents: Bivariate analysis for comparison of health outcomes between migraine patients and matched non-migraine respondents. D–F: migraine patients currently taking prescription medication (RX) and migraine patients not currently taking RX: adjusted means from GLM analysis for comparison of health outcomes between migraine patients currently taking prescription medication (RX) and migraine patients not currently taking RX. EQ-5D, EuroQol-5 Dimension; ER, emergency room; HCRU, healthcare resource utilisation; HRQoL, health-related quality of life; MCS, Mental Component Summary; PCS, Physical Component Summary; RCS, Role/Social Component Summary; Rx, prescription medication; WPAI, work productivity and activity impairment.

In terms of WPAI, migraine patients experienced significantly higher absenteeism (6.95% vs 3.07%, p<0.001), presenteeism (32.73% vs 18.94%, p<0.001), work productivity loss (34.82% vs 20.03%, p<0.001) and daily activity impairment (35.70% vs 22.04%, p<0.001) compared with matched controls (figure 2B).

Compared with controls, migraine patients visited healthcare professionals (HCPs) almost twice as often (8.38 vs 4.57, p<0.001) and visited the ER four times as often (0.12 vs 0.03, p<0.001). There were no significant differences in the number of hospitalisations between the two groups (figure 2C).

Migraine-related health characteristics among migraine patients

On average, patients received a migraine diagnosis 11.77 years ago (SD 10.84), and the majority (58.3%) were diagnosed by a primary care physician/general practitioner (GP)/internist (table 1). On average, patients experienced migraine 4.69 times (SD 6.22) in the past 30 days and 23.36 times (SD 33.72) in the past 6 months. In the past 30 days, migraine patients had an average of 6.45 (SD 7.02) headache days. Among female migraine patients, 41.4% experienced menstrual-related migraine. An average of 1.62 days of work and 2.94 days of household activities were missed due to migraine in the past 6 months. Among all patients, the average HIT-6 score was 59.37 (SD 7.97) and more than half (57.2%) of patients were severely impacted (HIT-6 score ≥60).25

Table 1.

Bivariate comparison of migraine-related health characteristics in diagnosed migraine patients and patients currently taking Rx versus patients not currently taking Rx (non-Rx)

| Diagnosed migraine patients (n=1265) |

Non-Rx (n=678) |

Rx (n=587) |

P value Non-Rx vs Rx |

|||||

| Mean or % | (SD) or (n) |

Mean or % |

(SD) or (n) |

Mean or % |

(SD) or (n) |

|||

| Time since migraine (years), mean (SD)* | 11.27 | (10.87) | 11.14 | (11.20) | 11.44 | (10.41) | 0.635 | |

| Diagnosing physician, % (n)* | Primary care Physician/GP/internist | 58.3% | (686) | 60.3% | (409) | 55.5% | (277) | 0.181 |

| Neurologist | 27.2% | (320) | 25.2% | (171) | 29.9% | (149) | ||

| Other | 14.5% | (171) | 14.5% | (98) | 14.6% | (73) | ||

| No of migraine in the past 30 days, mean (SD) | 4.69 | (6.22) | 3.61 | (5.54) | 5.95 | (6.72) | <0.001 | |

| No of migraine in the past 6 months, mean (SD) | 23.36 | (33.72) | 17.70 | (29.13) | 29.91 | (37.31) | <0.001 | |

| Days missed work due to migraine in the past 6 months, mean (SD) | 1.62 | (10.24) | 1.39 | (9.37) | 1.89 | (11.17) | 0.384 | |

| Days of household activities missed due to migraine in the past 6 months, mean (SD) | 2.94 | (12.67) | 1.81 | (5.70) | 4.25 | (17.48) | <0.001 | |

| No of headache days in the past 30 days, mean (SD) | 6.45 | (7.02) | 5.12 | (5.88) | 7.70 | (7.75) | <0.001 | |

| No of headache days in the past 30 days, % (n) | 0–3 MHDs | 49.4% | (365) | 57.3% | (205) | 42.0% | (160) | <0.001 |

| 4–14 MHDs | 36.8% | (272) | 33.8% | (121) | 39.6% | (151) | ||

| ≥15 MHDs | 13.8% | (102) | 8.9% | (32) | 18.4% | (70) | ||

| Don’t know | 24.0% | (304) | 24.4% | (161) | 24.0% | (143) | ||

| Not asked | 17.5% | (222) | 10.7% | (159) | 17.5% | (63) | ||

| Menstrual-related migraine (n= female only), % (n)† | 41.4% | (349) | 38.0% | (167) | 45.3% | (182) | 0.031 | |

| Use of OTC/Herbal products to treat migraine, % (n) | 12.9% | (163) | 14.6% | (99) | 10.9% | (64) | 0.050 | |

| Currently using Rx to treat or prevent migraine, % (n) | 46.4% | (587) | – | – | 100% | (587) | – | |

| Acute medication only, % (n)‡ | 77.5% | (455) | – | – | 77.5% | (455) | ||

| Preventive medication only, % (n)‡ | 14.3% | (84) | – | – | 14.3% | (84) | ||

| Both, % (n)‡ | 8.2% | (48) | – | – | 8.2% | (48) | ||

| HIT-6 score, mean (SD) | 59.37 | (7.97) | 57.76 | (8.00) | 61.23 | (7.52) | <0.001 | |

| HIT-6 impact grade, % (n) | Little to no impact | 11.3% | (143) | 14.9% | (101) | 7.2% | (42) | <0.001 |

| Moderate impact | 16.3% | (206) | 19.8% | (134) | 12.3% | (72) | ||

| Substantial impact | 15.3% | (193) | 16.4% | (111) | 14.0% | (82) | ||

| Severe impact | 57.2% | (723) | 49.0% | (332) | 66.6% | (391) | ||

*Sample size of diagnosed migraine patients who reported the time since diagnosis: n=1177, Non-Rx: n=678, Rx: n=499.

†Sample size of diagnosed migraine patients: n=842, Non-Rx: n=440, Rx: n=402.

‡Sample size of diagnosed migraine patients taking Rx: n=587.

GP, general practitioner; HIT, Headache Impact Test; MHD, monthly headache day; OTC, over-the-counter medication; Rx, prescription medication.

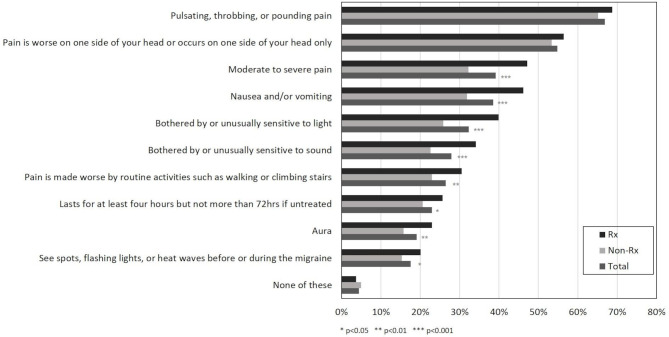

The most common migraine-related symptom was pulsating, throbbing, or pounding pain (66.9%), followed by ‘pain being worse on one side of your head or occurs on one side of your head only’ (54.8%), moderate to severe pain (39.1%), nausea and/or vomiting (38.5%), bothered by or unusually sensitive to light (32.3%), bothered by or unusually sensitive to sound (27.9%), pain made worse by routine activities such as walking or climbing stairs (26.5%), migraine lasting for at least 4 hours but not more than 72 hours if untreated (23.0%), aura (19.1%), and seeing spots, flashing lights or ‘heat waves’ before or during the migraine (17.5%). 4.4% of patients experienced none of the above symptoms (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Migraine-related symptoms. Non-Rx, patients currently not taking prescription medication; Rx, patients currently taking prescription medication.

Treatment use in migraine patients

Among all migraine patients, the majority (678; 53.6%) were not currently taking any prescription medication (Rx) (figure 1). 587 (46.4%) were currently taking prescription medication (Rx), whereof 77.5% currently used acute treatment, 14.3% used preventive treatments and 8.2% used both (table 1). Of the 678 migraine patients not currently taking Rx, 384 (56.6%) had previously used a prescription medication and 294 (43.4%) had never used a prescription medication, and 50 (17.0%) of the 294 patients had been recommended a prescription medication by the physician before. Of the migraine patients not currently taking Rx, 99 (14.6%) had used OTC or herbal product to treat migraine. Out of the total 1265 migraine patients, only 163 patients (12.9%) had used OTC or herbal product to treat migraine and 142 patients recalled the name of the OTCs they used.

Comparison of outcomes in Rx patients versus non-Rx patients

There were no differences in demographic characteristics between the Rx and non-Rx group, except for marital status. Significantly fewer patients taking Rx were married or living with partner (47.0% vs 58.4%, p<0.001) (table 2). In terms of migraine-related characteristics, migraine patients currently taking Rx experienced migraine significantly more often in the past 30 days (5.95 vs 3.61, p<0.001) and in the past 6 months (29.91 vs 17.70, p<0.001) compared with those not currently taking Rx (table 1). More days of household activities (4.25 vs 1.81, p<0.001) were missed due to migraine among patients currently taking Rx and a significantly higher percentage of patients had ≥15 MHDs (18.4% vs 8.9%, p<0.001) (table 1). A significantly higher average HIT-6 score (61.23 vs 57.76, p<0.001) was observed among migraine patients currently taking Rx and a higher percentage were determined to have severe impact (66.6% vs 49.0%, p<0.001) (table 1).

Table 2.

Bivariate comparison of demographics and general health characteristics in diagnosed migraine patients and patients currently taking Rx versus patients not currently taking Rx (non-Rx)

| Diagnosed migraine patients (n=1265) |

Non-Rx (n=678) |

Rx (n=587) |

P value No Rx vs Rx |

|||||

| Mean or % | (SD) or (n) |

Mean or % | (SD) or (n) |

Mean or % | (SD) or (n) |

|||

| Age, mean (SD) | 43.79 | (14.27) | 44.06 | (14.82) | 43.47 | (13.61) | 0.463 | |

| Gender, % (n) | Female | 66.6% | (842) | 64.9% | (440) | 68.5% | (402) | 0.177 |

| Marital status, % (n) | Married or living with partner | 53.1% | (672) | 58.4% | (396) | 47.0% | (276) | <0.001 |

| Having children <18 in the household, % (n) | Yes | 27.7% | (351) | 27.7% | (188) | 27.8% | (163) | 0.987 |

| Employment status, % (n) | Currently employed | 59.8% | (756) | 60.0% | (407) | 59.5% | (349) | 0.835 |

| Household income, % (n) | <¥3 000 000 | 18.7% | (237) | 18.4% | (125) | 19.1% | (112) | 0.318 |

| ¥3 000 000 to <¥5 000 000 | 25.0% | (316) | 24.2% | (164) | 25.9% | (152) | ||

| ¥5 000 000 to <¥8 000 000 | 24.6% | (311) | 26.0% | (176) | 23.0% | (135) | ||

| ¥8 000 000 or more | 17.0% | (215) | 18.1% | (123) | 15.7% | (92) | ||

| Decline to answer | 14.7% | (186) | 13.3% | (90) | 16.4% | (96) | ||

| CCI, mean (SD) | 0.24 | (1.00) | 0.19 | (0.60) | 0.29 | (1.32) | 0.072 | |

| Currently smoking, % (n) | Yes | 44.0% | (557) | 43.8% | (297) | 44.3% | (260) | 0.862 |

| Currently use alcohol, % (n) | Yes | 63.2% | (800) | 64.9% | (440) | 61.3% | (360) | 0.189 |

| Currently exercise, % (n) | Yes | 44.3% | (561) | 43.4% | (294) | 45.5% | (267) | 0.449 |

CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index; Rx, prescribed medication.

Without adjustment, the bivariate comparisons of outcomes in Rx versus non-Rx showed that migraine patients currently taking Rx had a lower MCS, higher daily activity impairment and increased number of visits to physicians in the past 6 months. No other differences in outcomes were observed (see online supplemental table 2).

bmjopen-2020-038987supp002.pdf (129.9KB, pdf)

After adjusting for potential confounding effects (age, CCI, gender, marital status, currently employed and number of migraines in the past 30 days), no significant differences in HRQoL, WPAI or HCRU were found between the two groups (figure 2D–F).

Discussion

In this study, we found that migraine patients in Japan experience a significant burden of illness compared with matched controls without migraine in terms of lower HRQoL, higher WPAI and HCRU (figure 2), and 88.8% of patients reported that migraine had a moderate to severe impact on their daily life (HIT-6 score) (table 1). Compared with matched controls, migraine patients had 2.93 points decreased PCS (p<0.001) and more than 3 points decreased MCS (3.66 points, p<0.001) and RCS (4.40 points, p<0.001) (figure 2), which indicates that migraine has a clinically significant impact on migraine patients’ mental health and role/social functioning. In comparison, similarly lower MCS scores have been reported in Japanese patients with arthritis (−3.4 points) and ischaemic heart disease (−4.1) compared with controls, and similarly lower PCS scores were reported in patients with diabetes (−3.0 point), chronic lung disease (−3.1 point) and ischaemic heart disease (−2.6 points).29

In addition to lower HRQoL, we observed that migraine patients who were currently employed had higher levels of work productivity loss compared with matched non-migraine controls, with 2.2-fold higher absenteeism (p<0.001), 1.7-fold higher presenteeism (p<0.001) and 1.7-fold higher work productivity loss (p<0.001) (figure 2). The actual work loss that Japanese migraine patients experience was thereby quantified based on the validated WPAI tool,24 and supports the previous findings that migraine can cause a substantial loss of work productivity.7–9 12

The finding in this current study that 74% of surveyed participants who reported ever having experienced migraine had not received a physician diagnosis of migraine indicates a large population of underdiagnosed migraine patients in Japan. This is supported by other studies showing that large proportions of migraine sufferers never consulted a physician.7 8

Additionally, in this study, we found that more than half of the diagnosed migraine patients (53.6%) were currently not receiving treatment with prescribed medication (non-Rx) (figure 1). However, 56.6% of non-Rx had previously received treatment which indicates a high treatment discontinuation rate which is supported by the previous study by Meyers et al30 where 62.2% discontinued prophylactic treatment after an average of 61.2 days. Also, 43.4% of non-Rx patients have not previously received prescription medication which reflects an unmet need for treatment. Other studies have similarly described that 30%–60% of migraine patients had never received prescription of preventive therapy,31 and that lack of efficacy and side effects were the most common reasons for discontinuation of both acute and preventive therapy.31–34 A recent study reported that among Japanese migraine patients who visited HCPs, lack of efficacy with both preventive (anticonvulsants and calcium antagonist) and acute treatment (triptans and NSAIDs) was experienced by half and a third of the patients, respectively.31

Migraine patients currently taking prescribed medication (Rx) had significantly worse migraine-related characteristics compared with migraine patients currently not taking any Rx (table 1, figure 3). This indicates that those taking Rx suffer from more severe migraine. Interestingly, migraine patients receiving Rx suffer similar impairment of HRQoL and work productivity as non-Rx patients (figure 2). This indicates that despite currently available preventive and acute treatments for migraine,6 10 there is an unmet need for improved HRQoL and work productivity among migraine patients, implying that current treatments have limited effects on these outcomes for patients. Additionally, only 14.3% of patients currently taking Rx received preventive treatments for migraine, indicating a lack of prescription of preventive therapy. These are important factors to consider for future treatment development.

The limitations of the study should be recognised. The data from NHWS are cross-sectional and no causal relationships can be assumed. As all data are self-reported, no verification of migraine diagnosis or patient reported outcomes was conducted, and data are subjected to recall bias. Although NHWS is broadly representative of the Japanese adult population, it is unclear the extent to which the migraine patients and migraine patients taking Rx are representative of the larger population. Due to the design of the survey, the reasons for not taking Rx or for discontinuation of Rx (eg, less migraine episodes or lack of efficacy) were not reported and could not be concluded. Also, NWHS primarily relied on respondents with internet access and these patients could potentially be different from the broader population (eg, more knowledgeable or engaged in their healthcare).

Conclusion

Migraine patients in Japan experience a significant burden of illness with decreased HRQoL, around twofold increased work productivity loss and twice as many visits to HCPs compared with non-migraine controls. There is a large proportion of both underdiagnosed and undertreated migraine patients. The migraine patients not receiving prescribed medication for treatment of their disease suffer similarly decreased HRQoL and high levels of work productivity loss as patients currently receiving prescribed medication. These results indicate an unmet need for improved HRQoL and work productivity in Japanese migraine patients despite the currently available prescription medications, which are important factors to consider for future development of migraine therapies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Dina Graae Kristensen at Graae MediWrite, for the medical writing support provided, including development, editing and proofreading of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: HI, KU and TN conceptualised the study and analysed and interpreted the data. SJ, ZC and YC designed the analysis plan, conducted the analyses and interpreted the data. All authors revised the manuscript drafts for intellectual content and edited the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final draft.

Funding: This research was funded by Eli Lilly Japan KK.

Competing interests: HI reports personal fees for consulting, lectures and speaker's honorarium from Pfizer, Eisai, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Kyowa Kirin, Takeda Pharmaceutical, Amgen Astellas BioPharma, and Eli Lilly, outside the submitted work. KU, TK and ZC are full-time employees of Eli Lilly Japan KK. and share holders of Eli Lilly & Company. SJ and YC are full-time employees of Kantar, Health Division.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: NHWS was granted exemption status upon review by Pearl International Review Board (Indianapolis, IN).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available on reasonable request.

Supplemental material This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

References

- 1.Vo P, Fang J, Bilitou A, et al. Patients’ perspective on the burden of migraine in Europe: a cross-sectional analysis of survey data in France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom. J Headache Pain 2018;19:82. 10.1186/s10194-018-0907-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yao C, Wang Y, Wang L, et al. Burden of headache disorders in China, 1990–2017: findings from the global burden of disease study 2017. J Headache Pain 2019;20:102. 10.1186/s10194-019-1048-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) The International classification of headache disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia Int J Headache 2018;38:1–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.GBD 2016 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. Lancet 2017;390:1211–59. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32154-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Woldeamanuel YW, Cowan RP. Migraine affects 1 in 10 people worldwide featuring recent rise: a systematic review and meta-analysis of community-based studies involving 6 million participants. J Neurol Sci 2017;372:307–15. 10.1016/j.jns.2016.11.071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takeshima T, Wan Q, Zhang Y, et al. Prevalence, burden, and clinical management of migraine in China, Japan, and South Korea: a comprehensive review of the literature. J Headache Pain 2019;20:111. 10.1186/s10194-019-1062-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sakai F, Igarashi H. Prevalence of migraine in Japan: a nationwide survey. Cephalalgia 1997;17:15–22. 10.1046/j.1468-2982.1997.1701015.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takeshima T, Ishizaki K, Fukuhara Y, et al. Population-based door-to-door survey of migraine in Japan: the daisen study. Headache 2004;44:8–19. 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2004.04004.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suzuki N, Ishikawa Y, Gomi S, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of headaches in a socially active population working in the Tokyo metropolitan area -surveillance by an industrial health consortium. Intern Med 2014;53:683–9. 10.2169/internalmedicine.53.1700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martelletti P, Schwedt TJ, Lanteri-Minet M, et al. My migraine voice survey: a global study of disease burden among individuals with migraine for whom preventive treatments have failed. J Headache Pain 2018;19:115. 10.1186/s10194-018-0946-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Negro A, Sciattella P, Rossi D, et al. Cost of chronic and episodic migraine patients in continuous treatment for two years in a tertiary level headache centre. J Headache Pain 2019;20:120. 10.1186/s10194-019-1068-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wada K, Arakida M, Watanabe R, et al. The economic impact of loss of performance due to absenteeism and presenteeism caused by depressive symptoms and comorbid health conditions among Japanese workers. Ind Health 2013;51:482–9. 10.2486/indhealth.2013-0016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.United States Census Bureau International data base, 2019. Available: https://www.census.gov/data-tools/demo/idb/informationGateway.php

- 14.Bolge SC, Doan JF, Kannan H, et al. Association of insomnia with quality of life, work productivity, and activity impairment. Qual Life Res 2009;18:415–22. 10.1007/s11136-009-9462-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DiBonaventura MD, Wagner J-S, Yuan Y, et al. Humanistic and economic impacts of hepatitis C infection in the United States. J Med Econ 2010;13:709–18. 10.3111/13696998.2010.535576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987;40:373–83. 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Charlson ME, Charlson RE, Peterson JC, et al. The Charlson comorbidity index is adapted to predict costs of chronic disease in primary care patients. J Clin Epidemiol 2008;61:1234–40. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Quan H, Li B, Couris CM, et al. Updating and validating the Charlson comorbidity index and score for risk adjustment in hospital discharge Abstracts using data from 6 countries. Am J Epidemiol 2011;173:676–82. 10.1093/aje/kwq433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brazier JE, Roberts J. The estimation of a preference-based measure of health from the SF-12. Med Care 2004;42:851–9. 10.1097/01.mlr.0000135827.18610.0d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fukuhara S, Bito S, Green J, et al. Translation, adaptation, and validation of the SF-36 health survey for use in Japan. J Clin Epidemiol 1998;51:1037–44. 10.1016/S0895-4356(98)00095-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fukuhara S, Ware JE, Kosinski M, et al. Psychometric and clinical tests of validity of the Japanese SF-36 health survey. J Clin Epidemiol 1998;51:1045–53. 10.1016/S0895-4356(98)00096-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.EuroQol Group EuroQol--a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy 1990;16:199–208. 10.1016/0168-8510(90)90421-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shiroiwa T, Fukuda T, Ikeda S, et al. Japanese population norms for preference-based measures: EQ-5D-3L, EQ-5D-5L, and SF-6D. Qual Life Res 2016;25:707–19. 10.1007/s11136-015-1108-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reilly MC, Gooch KL, Wong RL, et al. Validity, reliability and responsiveness of the work productivity and activity impairment questionnaire in ankylosing spondylitis. Rheumatology 2010;49:812–9. 10.1093/rheumatology/kep457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kosinski M, Bayliss MS, Bjorner JB, et al. A six-item short-form survey for measuring headache impact: the HIT-6. Qual Life Res 2003;12:963–74. 10.1023/A:1026119331193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.IBM Corp IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp, 2013

- 27.R Core Team R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2018. https://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maruish ME. User’s Manual for the SF-36v2 Health Survey. 3rd ed Lincoln, RI: Quality Metric Incorporated, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alonso J, Ferrer M, Gandek B, et al. Health-related quality of life associated with chronic conditions in eight countries: results from the International quality of life assessment (IQOLA) project. Qual Life Res 2004;13:283–98. 10.1023/B:QURE.0000018472.46236.05 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meyers JL, Davis KL, Lenz RA, et al. Treatment patterns and characteristics of patients with migraine in Japan: a retrospective analysis of health insurance claims data. Cephalalgia 2019;39:1518–34. 10.1177/0333102419851855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ueda K, Ye W, Lombard L, et al. Real-World treatment patterns and patient-reported outcomes in episodic and chronic migraine in Japan: analysis of data from the Adelphi migraine disease specific programme. J Headache Pain 2019;20:68. 10.1186/s10194-019-1012-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lipton RB, Hutchinson S, Ailani J, et al. Discontinuation of acute prescription medication for migraine: results from the chronic migraine epidemiology and outcomes (CaMEO) study. Headache 2019;59:1762–72. 10.1111/head.13642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wells RE, Markowitz SY, Baron EP, et al. Identifying the factors underlying discontinuation of triptans. Headache 2014;54:278–89. 10.1111/head.12198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blumenfeld AM, Bloudek LM, Becker WJ, et al. Patterns of use and reasons for discontinuation of prophylactic medications for episodic migraine and chronic migraine: results from the second International burden of migraine study (IBMS-II). Headache 2013;53:644–55. 10.1111/head.12055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2020-038987supp001.pdf (75.5KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-038987supp002.pdf (129.9KB, pdf)