Abstract

Introduction

Globally, a record number of people are affected by humanitarian crises caused by conflict and natural disasters. Many such populations live in settings where epidemiological transition is underway. Following the United Nations high level meeting on non-communicable diseases, the global commitment to Universal Health Coverage and needs expressed by humanitarian agencies, there is increasing effort to develop guidelines for the management of hypertension in humanitarian settings. The objective was to investigate the prevalence and incidence of hypertension in populations directly affected by humanitarian crises; the cascade of care in these populations and patient knowledge of and attitude to hypertension.

Methods

A literature search was carried out in five databases. Grey literature was searched. The population of interest was adult, non-pregnant, civilians living in any country who were directly exposed to a crisis since 1999. Eligibility assessment, data extraction and quality appraisal were carried out in duplicate.

Results

Sixty-one studies were included in the narrative synthesis. They reported on a range of crises including the wars in Syria and Iraq, the Great East Japan Earthquake, Hurricane Katrina and Palestinian refugees. There were few studies from Africa or Asia (excluding Japan). The studies predominantly assessed prevalence of hypertension. This varied with geography and age of the population. Access to care, patient understanding and patient views on hypertension were poorly examined. Most of the studies had a high risk of bias due to methods used in the diagnosis of hypertension and in the selection of study populations.

Conclusion

Hypertension is seen in a range of humanitarian settings and the burden can be considerable. Further studies are needed to accurately estimate prevalence of hypertension in crisis-affected populations throughout the world. An appreciation of patient knowledge and understanding of hypertension as well as the cascade of care would be invaluable in informing service provision.

Keywords: systematic review, hypertension, public health, health policy, epidemiology

Key questions.

What is already known?

Globally, non-communicable diseases are a leading cause of mortality and according to the WHO, hypertension is estimated to cause 12.8% of all deaths.

As of 2018, more than 70 million people were displaced as a result of humanitarian crises.

It is likely that people with hypertension are underserved in humanitarian settings.

What are the new findings?

Reported prevalence of hypertension in crisis-affected populations varies considerably across different populations with higher prevalence in those living in high-income countries.

There are very little data from Africa and Asia (except Japan) despite protracted refugee situations on these continents.

We have collated published estimates of hypertension prevalence by crisis, as well as the limited data on hypertension control, access to care and treatment, and patient understanding of hypertension.

What do the new findings imply?

Given the substantial prevalence of hypertension in many of the studies, assessment of hypertension and appropriate resourcing to treat it should be a priority for agencies providing emergency and longer-term care for patients after or during humanitarian crises in order to prevent significant mortality and morbidity.

There is a need to capture the patient experience in order to better inform service development.

Further research is needed, especially in Africa and Asia where there are additional protracted refugee situations.

Introduction

Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) are the leading cause of mortality globally, and nearly three-quarters of deaths due to NCDs occur in low/middle-income countries (LMICs).1

The Humanitarian Coalition defines a humanitarian crisis as ‘an event or series of events that represents a critical threat to the health, safety, security or well-being of a community or other large group of people’.2 Globally, the number of people affected by persecution, conflict, violence, human rights violations or natural disasters remains at record high levels; there were 70.8 million people displaced at the end of 2018. Increasing numbers of refugees are living in situations of protracted displacement (average 20 years) and in urban settings. Nine out of the ten countries hosting most of the world’s refugee populations are themselves developing nations and as such face financial and infrastructure challenges to meeting healthcare and other needs.3

Large numbers of those experiencing forced displacement (refugees or internally displaced persons) originate from Syria, Colombia, South Sudan, Democratic Republic of Congo, Myanmar, Yemen, Ethiopia and Somalia.3 In the former two countries, the epidemiological transition was apparent even before the displacement occurred, with cardiovascular diseases being the main cause of death in 1990. Even now, ischaemic heart disease and stroke combined contribute a similar proportion of deaths as conflict and terrorism in Syria, 33.83% and 36.13%, respectively.4

These factors have led to increasing calls for consideration of NCD care in humanitarian crises.5–7 The United Nations (UN) high-level meeting on the prevention and control of NCDs in 2011 highlighted the importance of prevention8 and workshops with non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and civil society groups highlighted the need for further information about prevention activities in humanitarian settings in particular.9 UN member states have agreed to achieve Universal Health Coverage (UHC) (which includes healthcare in humanitarian crises) by 2030, and prevention and treatment of raised blood pressure (BP) is one of the key recommended indicators.10

We can expect to find both new and poorly controlled hypertension in humanitarian crises. Armed conflicts in particular, are associated with increased short-term and long-term cardiac morbidity and mortality and increases in BP.11 12 Furthermore, the concept of ‘disaster hypertension’ was coined to describe the, often transient, increase in BP and associated cardiovascular mortality seen after natural disasters.13 For NCD management in general, disrupted supply of medication and the challenge of keeping already pressurised health systems functioning, are likely to result in poor disease control for existing patients.5 For hypertension in particular, there is ongoing research examining the link between different types of stress and increases in BP. Chronic rather than acute stress is associated with the development of long-term hypertension14 15 and there is some suggestion that higher levels of stress are associated with increased risk of developing the disease.16 Following exposure to conflict, research in military populations shows that post-traumatic stress disorder and injury severity are independent risk factors for the development of hypertension.17

Existing reviews have examined the burden of diabetes,18 substance misuse,19 20 smoking,21 alcohol,22 23 cardiovascular disease11 and NCDs24 25 in specific humanitarian settings. However, we do not have a broad understanding of hypertension in populations affected by crises. This is needed for service development.

The objective of this review was to investigate the prevalence and incidence of hypertension in populations directly affected by humanitarian crises; the cascade of care in these populations and patient knowledge of and attitude to hypertension.

Methods

We carried out a systematic review in accordance with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.26 Five databases were searched: Medline, Embase, PsycINFO, Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature and Web of Science. The search terms were adapted, following consultation with a librarian, from a similar review by Kehlenbrink et al18 examining the available evidence for the burden of diabetes in humanitarian crises. The search strategy is outlined in online supplemental appendix 1. Searches were conducted on 19th of August 2019. Given the importance of NGOs and civil service organisations in this area, the following grey literature databases were searched on 28th of August 2019: Google, ReliefWeb, UN High Commissioner for Refugees, WHO Institutional Repository for Information Sharing, UNICEF, Médecins Sans Frontières, International Rescue Committee, International Committee of the Red Cross, Centre for Disease Control and Prevention and Active Learning Network for Accountability and Performance. A list of the search terms used to identify relevant grey literature can be seen in online supplemental appendix 2.

bmjgh-2020-002440supp001.pdf (661.3KB, pdf)

bmjgh-2020-002440supp002.pdf (29.6KB, pdf)

Studies were assessed for the following criteria:

Population

The population of interest was non-pregnant, civilian adults (defined as 18 years or older) who had been directly exposed to a humanitarian crisis. This included refugees and internally displaced people.

Exposure

For the purposes of this review, the causes of humanitarian crises of interest were author defined armed conflict, complex emergencies and natural disasters (including earthquakes, floods, landslides, tidal waves, tsunamis, cyclones, droughts and famine). Only those studies reporting exposure which was ongoing in or began after 1 January 1999 were included.

Comparator

The presence or absence of a comparator was not used to determine study inclusion.

Outcome

The primary outcomes of interest were:

Prevalence and incidence of hypertension in populations directly affected by conflict, complex emergencies or natural disasters.

Proportion diagnosed with hypertension who are aware of the diagnosis, are receiving treatment, support or advice at time of study, and have achieved adequate levels of control.

Proportion with known hypertension who sought treatment but did not receive it.

Patient knowledge and attitude of hypertension as a problem.

Secondary outcomes were:

Understanding of whether or not hypertension management is included as part of a wider programme of prevention or health promotion.

Barriers and facilitators to accessing treatment.

For inclusion purposes, there were no restrictions placed on the mode of diagnosis of hypertension, duration of illness or treatment received.

Eligibility criteria

We included all study types, in any language, set in high-income, middle-income or low-income countries. Studies of populations directly affected by crises including general populations or populations selected from service users (without restriction by disease type) or selected for hypertension or cardiovascular disease interventional studies were included. Studies with mixed populations were only included if the population of interest could be clearly differentiated. Qualitative studies were included if patients with hypertension from the population of interest were directly interviewed.

Theses, conference proceedings, letters, clinical guidelines, study protocols, reports with no description of methods, opinion pieces or any study published before 1 January 1999 were excluded. Studies relating to economic migrants or migrants not affected by conflict or natural disasters were excluded. The individual study author’s definitions of type of migrant and exposure were applied. Studies including children (aged under 18 years) or examining hypertension in pregnancy where non-pregnant, adult data could not be extracted were excluded. Studies including only military or service personnel were also excluded. Isolated incidents of terrorism out with the context of armed conflict were not considered eligible.

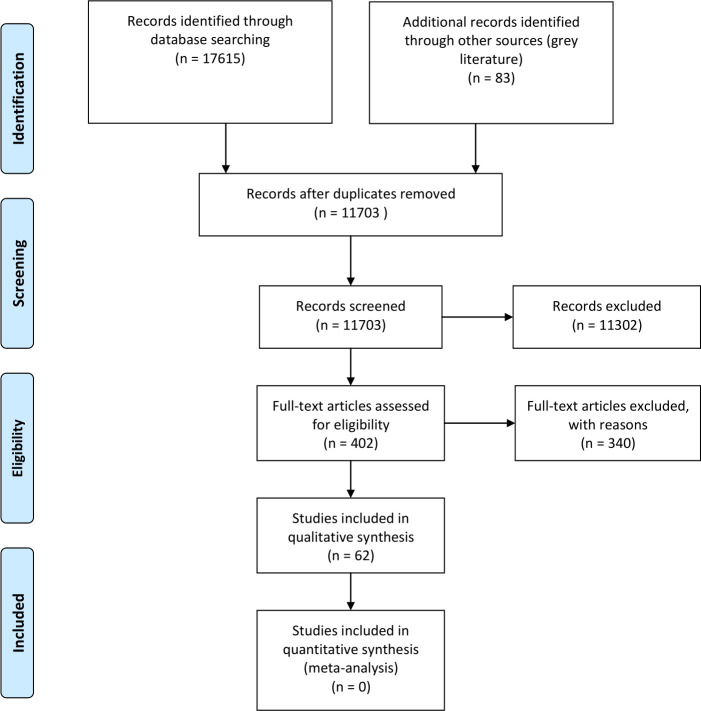

The authors used Rayyan to manage the identified references.27 Two reviewers screened the titles and abstracts of identified studies against the inclusion/exclusion criteria. At this stage, if either reviewer included a study, it was taken through to the full-text screening. Full texts of 318 published studies and 83 grey literature articles were screened for eligibility. Any conflicts were discussed and consensus was arrived at. Any studies excluded at the full-text screening stages were documented in a table with accompanying reasoning (online supplemental appendices 3 and 4). A third reviewer did not need to be consulted to resolve any disagreements. Two studies could not be accessed and so were excluded. The screening process is outlined in the PRISMA flow diagram in figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram. From: Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group (2009). Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med 6(7): e1000097. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed1000097. For more information, visit www.prisma-statement.org.

bmjgh-2020-002440supp003.pdf (197.6KB, pdf)

bmjgh-2020-002440supp004.pdf (216.3KB, pdf)

Definitions

Any definition of hypertension was considered, as described in individual studies. However, on quality assessment, the authors considered acceptable definitions of hypertension to be the WHO definition (ie, diagnosis if, when it is measured on two different days, the systolic BP readings on both days was ≥140 mm Hg and/or the diastolic BP readings on both days was ≥90 mm Hg.); or national or international clinical guidelines specified in a study; or doctor diagnosed hypertension; or the use of anti-hypertensive medication in those with a history of hypertension.

Data extraction and risk of bias assessment

Data extraction and risk of bias assessment were carried out by one author (JK or OO) with a 10% cross check by a second author (JK or FK). A data extraction tool was developed and piloted. For all study types, a description of the population, the location of the study, the type of study and a description of the crisis were extracted. For quantitative studies, the definition of hypertension and the number and proportion of those with the disease (with a measure of spread) for the whole population and for population subgroups were extracted. For qualitative studies, concepts and themes around the patients’ understanding of hypertension (primary outcome) and barriers and facilitators (secondary outcomes) were extracted.

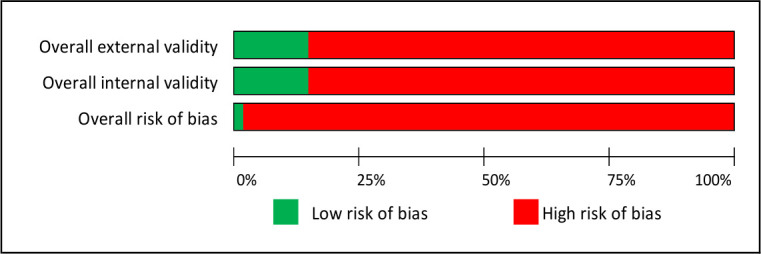

A tool developed by Hoy et al28 was used for assessing risk of bias in prevalence studies. This tool assesses external and internal validity. The external validity domain comprises questions about the sampling frame, sample selection and non-response bias. The internal validity domain comprises questions about the case definition, the measurement tool selected and application of that tool (see figure 2 for more details.) After piloting the tool, the authors adapted it slightly in order to give the studies a rating (of either high or low risk of bias) for both internal and external validity, as well as an overall score. This added further detail for assessing the quality of the included studies. For qualitative papers, the CASP toolkit was used.29

Figure 2.

Risk of bias. External validity questions: Was the sampling frame a true or close representation of the target population?, Was some form of random selection used to select the sample, or was a census undertaken?, Was the likelihood of non-response bias minimal? Internal validity questions: Were data collected directly from the subjects (as opposed to a proxy)?, Was an acceptable case definition used?, Was the study instrument that measured the parameter of interest shown to have reliability and validity?, Was the same mode of data collection used for all subjects?, Was the length of the shortest prevalence period for the parameter of interest appropriate?, Were the numerator and denominator for the parameter of interest appropriate?

Due to the heterogeneity of the included studies, the results were synthesised in a narrative description, exploring disease burden, treatment provision and treatment uptake. None of the qualitative papers we have included reported on our primary outcomes. Had there been more data available, we planned an interpretative review using a meta-ethnographic approach.30

Patient and public involvement

This research was done without patient or public involvement.

Results

Study characteristics

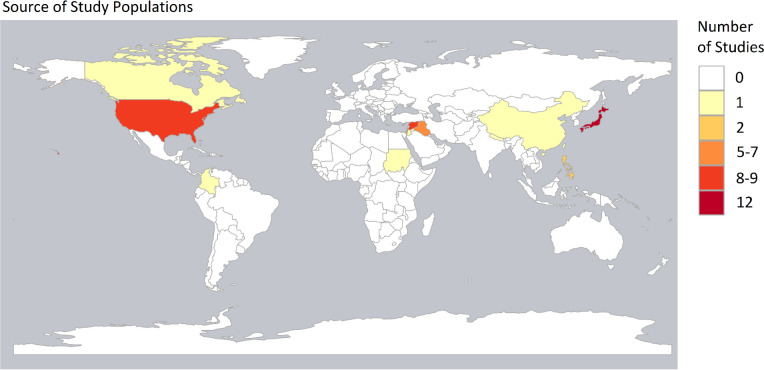

Sixty-two papers reporting 61 studies were included in the analysis. Table 1 outlines the key features of the included studies. The papers are organised by alphabetical order of the crisis. Twenty-five relate to conflicts, 6 relate to long-standing refugee situations and 31 are non-conflict related. Thirty studies were conducted in high-income countries (HICs) and the other 31 were conducted in LMICs. Of the HIC studies, five were related to populations who had been displaced from LMICs.31–34 The map in figure 3 shows the countries from which participants originated. The most frequently examined populations were from Japan, followed by the USA and Syria.

Table 1.

Study characteristics

| First author and year | Description of crisis (name, category and dates, as described in paper) | Population as described in paper | Adults or elderly (as defined by paper) | Displaced | Type of crisis | Location of study |

| Gómez-Restrepo et al 201884 | Colombian conflicts, (ongoing) | 10764 respondents to the National Mental Health Survey (2016), some of whom exposed to armed conflict | Adult | Unclear | Conflict | LMIC |

| Furusawa et al 201185 | Earthquake, Solomon Islands, (2007) | Villagers in Western province | Adult | Mixed | Non-conflict | LMIC |

| Vanasse et al 201686 | Flood in the city of Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu, (2011) | All adult individuals covered by the Quebec universal public health insurance plan resident in postcodes affected by the flood (271 postcodes, 119 of which had more than half of their surface area flooded) | Adult | Unclear | Non-conflict | HIC |

| Ebner et al 201638 | Great East Japan Earthquake, (2011) | Adults over 40 living in Kawauchi village, 20 km west from Fukushima | Adult | Yes | Non-conflict | HIC |

| Hayashi et al 201787 | Great East Japan Earthquake, (2011) | People aged 40–74 years living in 1 of 13 municipalities in Fukushima in the evacuation zone | Adult | Mixed | Non-conflict | HIC |

| Hoshide et al 201988 | Great East Japan Earthquake, (2011) | 388 evacuees living in evacuation shelters after the earthquake | Adult | Yes | Non-conflict | HIC |

| Nagai et al 201837 | Great East Japan Earthquake, (2011) | Patients aged 40–74 years living near Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant | Adult | Mixed | Non-conflict | HIC |

| Nomura et al 201689 | Great East Japan Earthquake, (2011) | Patients aged 40–74 years living in Minamisoma and Soma | Adult | Mixed | Non-conflict | HIC |

| Ohira et al 201651 | Great East Japan Earthquake, (2011) | Evacuee and non-evacuee Japanese adults without hypertension aged 40–74 years living near the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant before the earthquake | Adult | Mixed | Non-conflict | HIC |

| Sakai et al 201770 | Great East Japan Earthquake, (2011) | Individuals aged 40–90 years living in the vicinity of the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant who had attended annual health checkups since 2008 | Adult | Mixed | Non-conflict | HIC |

| Satoh et al 201639 | Great East Japan Earthquake, (2011) | Patients aged 40–90 years who were living near the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant | Adult | Mixed | Non-conflict | HIC |

| Shiba et al 201990 | Great East Japan Earthquake, (2011) | Patients aged 65 years or older in Iwanuma affected by the tsunami | Elderly | Mixed | Non-conflict | HIC |

| Suda et al 201991 | Great East Japan Earthquake, (2011) | Evacuees with disaster medical records from Minamisanriku town after the earthquake | Adult | Mixed | Non-conflict | HIC |

| Takahashi et al 201692 | Great East Japan Earthquake, (2011) | 6528 disaster survivors in heavily tsunami-damaged municipalities (both relocated and non-relocated) | Adult | Mixed | Non-conflict | HIC |

| Toda et al 201793 | Great East Japan Earthquake, (2011) | Adults over 40 years living in Minamisoma city, 10–40 km from the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Plant | Adult | Mixed | Non-conflict | HIC |

| An et al 201549 | Hurricane Ike, (2008) | Free clinic attendees who had stayed on the island during the rainstorm >18 years, did not have a pre-hurricane history of coronary heart disease or psychiatric diagnoses and could read English |

Adult | No | Non-conflict | HIC |

| Gomez et al 200994 | Hurricane Ivan, (2004) | Adult members of the community of 'Jubilee', Grenada | Adult | No | Non-conflict | LMIC |

| Greenough et al 200895 | Hurricane Katrina, (2005) | Heads of household in Louisiana American Red Cross shelters | Adult | Yes | Non-conflict | HIC |

| Kessler 200796 |

Hurricane Katrina, (2005) | Adults living in areas eligible for assistance after Hurricane Katrina | Adult | Mixed | Non-conflict | HIC |

| Islam et al 200864 | Hurricane Katrina, (2005) | 2194 adults over 65 with hypertension on managed care organisation databases | Elderly | No | Non-conflict | HIC |

| Krol et al 200797 | Hurricane Katrina, (2005) | Patients from Biloxi/Gulfport affected by Hurricane Katrina | Adult | Unclear | Non-conflict | HIC |

| Krousel-Wood et al 200860 | Hurricane Katrina, (2005) | Community-dwelling patients attending the hypertension section of a multispecialty group practice | Adult | Mixed | Non-conflict | HIC |

| Rodriguez et al 200640 | Hurricane Katrina, (2005) | Adult evacuees from Louisiana in Oklahoma | Adult | Yes | Non-conflict | HIC |

| Vest et al 200641 | Hurricane Katrina, (2005) | New Orleans adults displaced by Hurricane Katrina, sheltered in Austin, Texas | Adult | Yes | Non-conflict | HIC |

| Arrieta et al 200965 | Hurricane Katrina, 2005 | 30 health and social service providers, 28 chronic disease patients | Adult | Unclear | Non-conflict | HIC |

| Burton et al 200935 | Hurricane Katrina, 2005 | Non-institutionalised Peoples Health enrollees who lived in four parishes in the New Orleans metropolitan area (age 65+ years) | Elderly | Mixed | Non-conflict | HIC |

| Burger et al 201948 | Hurricane Sandy, (2012) | Patients from 7 Federal Quality Health Centres in New Jersey | Adult | No | Non-conflict | HIC |

| Prueksaritanond et al 200798 | Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami, (2004) | 87 elderly members of the Ban Nam Khem Community, Thailand | Elderly | No | Non-conflict | LMIC |

| Doocy et al 201342 | Iraq War, (2003–2011) | Iraqi populations displaced in Jordan and Syria | Adult | Yes | Conflict | LMIC |

| Mateen et al 201299 | Iraq War, (2003–2011) | Iraqi refugees in Jordan | Adult | Yes | Conflict | LMIC |

| Lafta et al 2016100 | Iraq War and subsequent sectarian violence, (2003–) | Women from internally displaced families living in informal settlements | Adult | Yes | Conflict | LMIC |

| Anon et al 2010 101 | Iraq War, (2003–2011) | Iraqi refugees settled in San Diego, California | Adult | Yes | Conflict | HIC |

| Jen et al 201531 | Iraq War, (2003–2011) | 290 Iraqi adult refugees recently arrived in Michigan | Adult | Yes | Conflict | HIC |

| Taylor et al 201432 | Iraq War, (2003–2011) | Iraqi adults settled in the USA for between 8 and 36 months | Adult | Yes | Conflict | HIC |

| Baxter et al 201866 | Iraqi Civil War, (2014–17) | 15 adult from Mosul presenting to MSF in Kurdistan | Adult | Yes | Conflict | LMIC |

| Cetorelli et al 201752 | Iraqi Civil War, (2014–17) | Adults in BRHA camps | Adult | Yes | Conflict | LMIC |

| Dudova et al 2015102 | Iraqi Civil War, (2014–17) | 1119 refugee patients at a primary care clinic for internally displaced people in Ozal city, Erbil | Adult | Yes | Conflict | LMIC |

| Lipsitz et al 201036 | Israel–Lebanon War, (2006) | Patients attending five clinics in Jerusalem and surrounding areas, whose home address was in northern Israel | Adult | Yes | Conflict | HIC |

| Adrega et al 2018103 | Nepal earthquake, (May 2015) | Dislodged inhabitants of Sindhupalchok | Adult | Mixed | Non-conflict | LMIC |

| Khader et al 201453 | Palestine conflict, (—) | All Palestinian patients registered in 6 UNRWA primary care clinics in Jordan | Adult | Yes | Long-standing refugee situation | LMIC |

| Khader et al 201261 | Palestine conflict, (—) | Palestinian refugees registered with Nuzha primary care centre with hypertension | Adult | Yes | Long-standing refugee situation | LMIC |

| Mousa et al 2010104 | Palestine conflict, (—) | Palestinian refugees in Jordan, Lebanon, Syrian Arab Republic, West Bank and the Gaza Strip served by UNRWA primary care facilities | Adult | Yes | Long-standing refugee situation | LMIC |

| Saadeh et al 201543 | Palestine conflict, (—) | Palestinian refugees (aged 40 years and over) treated by GPs at the UNRWA primary healthcare centres in Jordan | Adult | Yes | Long-standing refugee situation | LMIC |

| Saleh et al 2018 44 | Palestine conflict, (—) | Palestinian refugees (aged 40 years and over) living in camps in Lebanon | Adult | Yes | Long-standing refugee situation | LMIC |

| Abukhdeir et al 2013105 | Palestinian conflict, (—) | Palestinians living in the Gaza Strip and the West Bank | Adult | Mixed | Long-standing refugee situation | LMIC |

| Renzaho et al 201433 | Sudanese wars (ongoing throughout time frame) | 314 Sudanese refugees settling in Brisbane/Toowoomba, Australia. | Adult | Yes | Conflict | HIC |

| Mobula et al 201650 | Super Typhoon Haiyan, Philippines, (2013) | Patients attending clinics conducted by mobile medical teams | Adult | Unclear | Non-conflict | LMIC |

| Balcilar et al 201662 | Syrian War, (2011–) | Syrian refugees in Turkey aged 18–69 years | Adult | Yes | Conflict | LMIC |

| Chahda et al 201547 | Syrian War, (2011–) | 167 Syrian refugees registered with CLMC and 43 Palestinian refugees from Syria registered with the Palestinian Women’s Humanitarian Organisation in Lebanon | Elderly | Yes | Conflict | LMIC |

| Doocy et al 201854 | Syrian War, (2011–) | Syrian refugees in Lebanon | Adult | Yes | Conflict | LMIC |

| Doocy et al 201567 | Syrian War, (2011–) | Syrian refugees in Jordan | Adult | Yes | Conflict | LMIC |

| Doocy et al 201655 | Syrian War, (2011–) | Syrian refugees in Lebanon | Adult | Yes | Conflict | LMIC |

| Eryurt et al 202046 | Syrian War, (2011–) | Syrian refugees in Turkey (age 18–69 years) | Adult | Yes | Conflict | LMIC |

| Maldari et al 201934 | Syrian War, (2011–) | Syrian refugees seen at Refugee Health Service, South Australia | Adult | Yes | Conflict | HIC |

| Rehr et al 201856 | Syrian War, (2011–) | Non-camp Syrian refugees in Irbid northern Jordan | Adult | Yes | Conflict | LMIC |

| Strong et al 2015106 | Syrian War, (2011–) | 210 older refugees from Syria in Lebanon | Elderly | Yes | Conflict | LMIC |

| Doocy et al 2014107 | Syrian War, (2011–) | Syrian refugees in Jordan | Adult | Yes | Conflict | LMIC |

| Vernier et al 201945 | Syrian War, (2011–) | Families living in Ein Issa camp | Adult | Yes | Conflict | LMIC |

| Doocy et al 201657 | Syrian War, (2011) | Syrian refugees in Jordan | Adult | Yes | Conflict | LMIC |

| Kayali et al 201958 | Syrian War, (2011) | Patients with hypertension in Shatila refugee camp | Adult | Yes | Conflict | LMIC |

| Lin et al 2015108 | Typhoon Morakot, Taiwan, (2009) | Typhoon-displaced adults from Kaohsiung County. Two groups: 1 moved to shelters, 1 moved within the community | Adult | Yes | Non-conflict | LMIC |

| Sun et al 201359 | Wenchuan earthquake, China (2008) | 3230 adults over 20 who had stayed in temporary shelters for more than 1 year | Adult | Yes | Non-conflict | LMIC |

BRHA, Board of Relief and Humanitarian Affairs; CHD, coronary heart disease; CLMC, Caritas Lebanon Migrant Centre; GP, general practitioner; HIC, high-income country; LMIC, low/middle-income country; MSF, Médecins Sans Frontières; UNRWA, United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestinian Refugees in the Middle East.

Figure 3.

Map showing the number of papers by country of origin of study population. Map created using R. Granada is missing from the map and featured in one paper.

Six papers related to elderly populations and the remaining papers were related to general adult populations over the age of 18 years. Thirty-five studies considered displaced populations, while 5 considered non-displaced populations and 16 considered mixed populations of both displaced and non-displaced participants. Displacement status was unclear for five studies.

Several crises were the subject of multiple studies. The Great East Japan Earthquake was the subject of 12 studies, Hurricane Katrina was the subject of 9 studies, the Iraq wars since 2003 were the subject of 9 studies, the Palestinian conflict was the subject of 6 studies and the Syrian War was the subject of 12 studies (13 papers).

Prevalence and incidence of hypertension

Fifty-five studies reported information on hypertension prevalence. Of these, only 33 have prevalence rates related to the whole population sample. The remaining papers measure prevalence in subgroups, either by sex, age, ethnicity, evacuation status, location or housing damage. Among the whole population samples, the prevalence rates range from 3%35 36 to 83.14%.35 The wide range reflects the heterogeneity of the studies, especially the different mean ages of the populations. We present the prevalence data in tables 2 and 3 by country income levels of HICs or LMICs.

Table 2.

Prevalence of hypertension reported in eligible studies conducted in high-income countries

| First author and year | Measurement used | Subgroup (if no whole population prevalence available) | Number with disease | Value of denominator | Proportion with disease as reported (%) | Measure of spread as reported (95% CI) |

| Japan | ||||||

| Ebner et al 201638 | BP >130/85 or on antihypertensive medications | Pre-earthquake | 6107 | 9296 | 65.7 | 62.7 to 68.5 |

| 2012 | 1731 | 2801 | 61.8 | 58.2 to 65.2 | ||

| 2013 | 1780 | 2794 | 63.7 | 59.9 to 67.4 | ||

| Hayashi et al 201787 | BP >140/90 or on medication | Baseline BP | 14 492 | 54 | ||

| Hoshide et al 201988 | Mean of 3×BP >140/90 | Disaster HTN | 158 | 272 | ||

| Pre-earthquake HTN | 126 | 272 | ||||

| Disaster HTN among patients without prevalent HTN | 66 | 146 | 45.2 | |||

| Disaster HTN among patients with HTN normally | 92 | 126 | 73 | |||

| Nagai et al 201837 | BP >140/90 or on antihypertensive medications | 2010 male | 9912 | 44.4 | 42.7 to 46.0 | |

| 2011 male | 7249 | 47.2 | 45.2 to 49.2 | |||

| 2012 male | 9499 | 48.8 | 47.1 to 50.6 | |||

| 2013 male | 9485 | 47.4 | 45.7 to 49.2 | |||

| 2014 male | 9619 | 45.5 | 43.8 to 47.3 | |||

| 2010 female | 12 178 | 37.5 | 36.3 to 38.7 | |||

| 2011 female | 8828 | 38.6 | 37.3 to 40.0 | |||

| 2012 female | 11 615 | 39 | 37.8 to 40.3 | |||

| 2013 female | 11 851 | 37.8 | 36.6 to 39.1 | |||

| 2014 female | 12 341 | 35.6 | 34.4 to 36.8 | |||

| Nomura et al 201689 | BP >140/90 or on antihypertensive medications | Baseline (2008–2010) evacuee |

437 | 960 | 45.5 | |

| Baseline (2008–2010) non-evacuee |

2463 | 5446 | 45.3 | |||

| 2011 evacuee | 112 | 216 | 51.9 | |||

| 2011 non-evacuee | 1506 | 2870 | 52.6 | |||

| 2012 evacuee | 333 | 627 | 53.1 | |||

| 2012 non-evacuee | 2020 | 3886 | 52.1 | |||

| 2013 evacuee | 366 | 657 | 55.7 | |||

| 2013 non-evacuee | 1888 | 3680 | 51.3 | |||

| 2014 evacuee | 297 | 617 | 48.1 | |||

| 2014 non-evacuee | 1758 | 3591 | 49.2 | |||

| Ohira et al 201651 | On medication or BP >140/90 | Men | 1242 | 4515 | 27.5 | |

| Women | 1362 | 6522 | 20.9 | |||

| Sakai et al 201770 | Not stated | Evacuee | 5364 | 54.1 | ||

| Non-evacuee | 2349 | 56.3 | ||||

| Satoh et al 201639 | Not stated | Low risk, evacuee | 7253 | 56.3 | ||

| Low risk, non-evacuee | 13 730 | 56.1 | ||||

| Moderate risk, evacuee | 1777 | 71 | ||||

| Moderate risk, non-evacuee | 3319 | 69.5 | ||||

| High risk, evacuee | 290 | 86.6 | ||||

| High risk, non-evacuee | 492 | 80.3 | ||||

| Very high risk, evacuee | 87 | 93.1 | ||||

| Very high risk, non-evacuee | 140 | 92.1 | ||||

| Shiba et al 201990 | HTN medication | 414 | 1195 | 34.6 | ||

| Suda et al 201991 | ICD-10 | 2678 | 10 462 | 25.6 | ||

| Takahashi et al 201692 | Self-reported | 3160 | 32 | |||

| 3368 | 29 | |||||

| Toda et al 201793 | Antihypertensive medication | 2009 men | 74 | 224 | 33 | |

| 2009 women | 85 | 339 | 25.1 | |||

| 2010 men | 80 | 224 | 35.7 | |||

| 2010 women | 96 | 339 | 28.3 | |||

| 2011 men | 90 | 224 | 40.2 | |||

| 2011 women | 109 | 339 | 32.2 | |||

| 2012 men | 99 | 224 | 44.2 | |||

| 2012 women | 124 | 339 | 36.6 | |||

| Hurricane Katrina | ||||||

| Greenough et al 200895 | Self-reported | 170 | 499 | 34.8 | 30.4 to 39.2 | |

| Kessler 200796 |

Self-reported | 1043 | 31.2 | SE±2.5 | ||

| Krol et al 200797 | Record on medical chart | Age 22–65 | 99 | 677 | 26.1 | |

| Age >65 | 29 | 72 | 59.2 | |||

| Rodriguez et al 200640 | Self-reported | 62 | 241 | 25.7 | ||

| Vest et al 200641 | Self-reported | 71 | 183 | 39.5 | 32.5 to 46.5 | |

| Burton et al 200935 | ICD-9-CM | 20 612 | 83.14 | |||

| Other HIC | ||||||

| Vanasse et al 2016 (Canada)86 | History of hypertension was defined as a hospitalisation with a main or a secondary diagnosis of hypertension (ICD-9 codes: 401–405 and ICD-10-CA codes: I10–I13, I15) or at least two ambulatory visits for hypertension in a 2-year span between 1996 and the beginning of the study period |

2328 | Whole sample | 10 081 | 23.1 | |

| An et al 2015 (USA)49 | Self-reported/on medication/average of 3 consecutive measures, cut-off >140/90 | 14 | 19 | 73.7 | ||

| Burger et al 2019 (USA)48 | Self-reported | 27 | 489 | 5.5 | ||

BP, blood pressure; HIC, high-income country; HTN, hypertension; ICD, International Classification of Diseases.

Table 3.

Prevalence of hypertension reported in eligible studies conducted in LMICs

| First author and year | Measurement used | Subgroup (if no whole population prevalence available) | Number with disease | Value of denominator | Proportion with disease as reported (%) | Measure of spread as reported (95% CI) |

| Iraq | ||||||

| Doocy et al 201342 | Taking medications or medical visits | Jordan | 3414 | 19.6 | 18.3 to 21.0 | |

| Syria | 2342 | 19.6 | 18 to 21.3 | |||

| Mateen et al 201299 | ICD-10 diagnosis | 18–59 male | 390 | 2252 | 17.3 | |

| 18–59 female | 420 | 2399 | 17.5 | |||

| 60–79 | 784 | 1230 | 63.7 | |||

| >80 | 76 | 100 | 76 | |||

| Lafta et al 2016100 | Diagnosis by a health worker | 240 | 1216 | 19.7 | ||

| Anon et al 2010101 | BP >140/90 on two measurements | 83 | 129 | 64.3 | ||

| Jen et al 201531 | Doctor diagnosed | 28 | 290 | 9.6 | ||

| 38 | 290 | 13.1 | ||||

| Taylor et al 201432 | Self-reported | 95 | 366 | 26 | ||

| Cetorelli et al 201752 | Health professional diagnosis | 30–44 | 1193 | 4.4 | 3.2 to 5.9 | |

| 45–59 | 550 | 23.9 | 19.8 to 28.5 | |||

| 60+ | 309 | 32.1 | 26.3 to 38.4 | |||

| Dudova et al 2015102 | On patient documents | 35–44 | 10 | 122 | 8.2 | |

| 45–54 | 46 | 204 | 22.6 | |||

| 55–64 | 79 | 231 | 34.2 | |||

| 65+ | 109 | 226 | 48.2 | |||

| Palestine | ||||||

| Saadeh et al 201543 | Clinical diagnosis | 2008 | 42 495 | 307 935 | 13.8 | |

| 2009 | 46 317 | 312 951 | 14.8 | |||

| 2010 | 49 361 | 324 743 | 15.2 | |||

| 2011 | 52 718 | 323 423 | 16.3 | |||

| 2012 | 53 278 | 367 434 | 14.5 | |||

| Mousa et al 2010104 | One-off BP >140/90 | 1453 | 7762 | 18.7 | ||

| Abukhdeir et al 2013105 | Self-reported | Age 20–39 | 77 | 0.8 | ||

| Age 40–64 | 633 | 14.1 | ||||

| Age 65+ | 393 | 33.1 | ||||

| Saleh et al 201844 | One-off BP >140/90 | 37.2 | ||||

| Syria | ||||||

| Balcilar et al 201662 | >140/90 or on medication | 1463 | 5713 | 25.6 | 24.4 to 26.7 | |

| Chahda et al 201547 | Self-reported | Elderly Syrian refugees | 89 | 167 | 53 | 46 to 61 |

| Elderly Palestinian refugees from Syria | 37 | 43 | 86 | 72 to 94 | ||

| Doocy et al 201567 | Self-reported | 18–39 | 60 | 3019 | 2 | 1.4 to 2.6 |

| 40–59 | 220 | 1040 | 21.1 | 18.6 to 23.7 | ||

| 60+ | 195 | 374 | 52.1 | 46.5 to 57.7 | ||

| Adult | 475 | 4433 | 10.7 | 9.8 to 11.7 | ||

| Doocy et al 201655 | Healthcare professional diagnosed | 3886 | 7.4 | 6.6 to 8.3 | ||

| Eryurt et al 202046 | Medication for hypertension or raised BP (average of 2 readings) | 1687 | 5322 | 32 | ||

| Maldari et al 201934 | Patient/clinician reported | 25 | 186 | 13.4 | ||

| Rehr et al 201856 | Self-reported | 1126 | 8029 | 14 | 13.2 to 14.8 | |

| Doocy et al 2014107 | Self-reported | 500 | 5154 | 9.7 | 8.8 to 10.6 | |

| Vernier et al 201945 | Self-reported | 28 | 582 | 4.8 | 3.3 to 6.9 | |

| Other LMIC | ||||||

| Sun et al 2013 (China)59 | BP >140/90 or diagnosis or taking medications | 778 | 3230 | 24.08 | ||

| Gomez-Restrepo et al 2018 (Colombia)84 | Doctor diagnosed | Exposed to conflict | 101 | 493 | 20.4 | 15.7 to 26.1 |

| Doctor diagnosed | Exposed to conflict and another traumatic event | 65 | 346 | 18.7 | 12.2 to 27.6 | |

| Adrega et al 2018 (Nepal)103 | Self-reported/on medication/one-off BP >140/90 | 62 | 167 | 22.4 | ||

| Mobula et al 2016 (Philippines)50 | BP >=140/90 | 1709 | 3633 | 47 | ||

| Renzaho et al 2014 (Sudan)33 | Healthcare diagnosed | 39 | 314 | 12.4 | ||

| Lin et al 2015 (Philippines)108 | Self-reported | 127 | 228 | 46.2 | ||

| Prueksaritanond et al 2007 (Taiwan)98 | Not reported | 38 | 87 | 43.7 | ||

| Furusawa et al 2011 (Solomon Islands)85 | One-off BP >140/90 | Titiana | 79 | 622 | 12.7 | |

| Tapurai | 68 | 919 | 7.4 | |||

| Mondo | 59 | 129 | 45.8 | |||

| Gomez et al 2009 (Grenada)94 | Not reported | 30 | ||||

BP, blood pressure; ICD, International Classification of Diseases; LMIC, low/middle-income country.

Of the groups of studies, the Great East Japan Earthquake studies (table 2) are the most homogenous because 8 of the 12 studies gathered data from the same source of routine health data targeting adults between the ages of 40 and 74 years. The prevalence range in these studies was 35.6% in female participants in 201437 to 65.7% in both men and women before the earthquake.38 Several of the studies examined the changing prevalence of hypertension from the years before the earthquake to the years following the earthquake. Among these studies, some of the data may have been repeated because the authors used samples from overlapping communities. However, even among these studies there were important differences in study design. Some measured the BPs of the whole population,37 whereas others only measured the BP of patients who were normally normotensive.39

In comparison, six of the nine studies relating to Hurricane Katrina measured prevalence of hypertension (see table 2). Burton et al found the highest prevalence of hypertension among elderly enrollees on a health insurance programme (83.14%).35 However, the prevalence of hypertension among adults of all ages who were either in shelters or eligible for government assistance was between 25.7%40 and 39.5%.41

The studies relating to Iraq are more difficult to compare because of the different ways in which the prevalence is reported (table 3). In particular, the studies divide the prevalence into different age categories. However, as may be expected, all of the studies report that the prevalence of hypertension increases with age. For example, Doocy et al report a prevalence of 9.3% among adults aged 18–49 years and a prevalence of 68.8% among adults over the age of 70 years.41 42

For Palestinian refugees aged 40 years and above based in Jordan, Lebanon, Syrian Arab Republic, West Bank and the Gaza Strip, the prevalence of hypertension ranged from 13.8%.43 to 29.7%.44 (table 3). Most of these studies collected data from the UN Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA) primary healthcare facilities.

Again, the prevalence rates for hypertension among the Syrian studies are difficult to compare due to the different age ranges and age distributions within the study populations (table 3). However, the prevalence rates in adult populations range from 4.8%45 to 32%.46 One study considered elderly patients only, and found the rates of hypertension to be up to 83%.47 This population size, however, was small and the measure of hypertension was self-reported diagnosis. As with the other groups, the studies broke down prevalence rates by age, gender or location.

Looking at the remaining geographical areas, there were only four studies in the HIC group and they were all based in either the USA or Canada. Hypertension prevalence in the HIC studies varied considerably from 5.5%48 to 73.7%.49 However, this highest estimate is taken from a study with only 19 participants. Among the remaining eight LMIC studies, the prevalence ranged from 12.4%33 to 47%.50

Only four papers measured the incidence of hypertension.31 35 49 51 These studies all took place in HICs and incidence ranged from 10.25/1000 to 210.52/1000.

Other outcomes

The other outcomes we examined were considered less frequently. Nine studies considered care seeking or treatment.37 52–59 Among studies examining utilisation of health services, a high proportion of patients with hypertension sought care for their condition in crisis settings; over 80% as reported by Rehr et al56 and Doocy et al57 (these data only relate to patients from Syria and Iraq). There was, however, no evidence detailing challenges to accessing care among patients who sought treatment.

In relation to treatment, the picture was more variable; the rates of treatment ranged from 53.4%59 to 98.1% of patients with hypertension.54 Eight studies considered BP control or medication adherence.53 54 58–63 This was very variable. Khader et al, for example, note that among Palestinian refugee patients with hypertension attending UNWRA clinics in Jordan, BP control was as high as 83%53 whereas Sun et al found that only 17.84% of patients diagnosed with hypertension after the Wenchuan earthquake had controlled BP.59 Sun et al were also the only authors to consider awareness of diagnosis.59

Six studies considered the barriers that patients face to manage their BP in crises, citing cost and availability of care, and severity of crisis in a given location as key reasons for disruptions in treatment and control.60 63–67 This group contains the only two qualitative studies included in the review. 65 66 There were also only two studies measuring what the authors considered to be a proxy for patient understanding of hypertension, that is, whether or not patients took medications as prescribed.52 59 This ranged from 33.1% in China to 68.5% in Iraq.

Risk of bias

Online supplemental appendix 5 gives details of the risk of bias for each study and figure 2 summarises this across all studies. Only one of the studies was considered to be at low risk of bias.62 A further 10 studies were considered at low risk of bias in one domain. All other studies were at high risk of bias across both domains. Seventeen of the studies used self-reporting as the case definition, while several others did not report the case definition at all. As can be seen in tables 2 and 3, very few studies included a measure of data spread such as CIs. In addition, many of the sampling frames used were not a close representation of the target populations: for example, they may be clinic attendees, patients attending screenings or an unspecified sample of evacuation shelters.

bmjgh-2020-002440supp005.pdf (215.2KB, pdf)

Discussion

This systematic review included 61 studies, 55 of which considered prevalence of hypertension. There was far less evidence relating to patient access to care and patient views of hypertension. The included studies were heterogeneous in relation to their populations and corresponding crises. It is therefore challenging to make comparisons and draw robust conclusions from the available evidence. Even studies reporting on the same crises often considered different population groups.35 40 In this review, the prevalence of hypertension tended to be greater among the USA and Japanese populations in comparison to the Palestinian and Syrian populations. This is in keeping with the distribution of hypertension in the general population of those countries (USA prevalence of hypertension 30% (95% CI 35%–26%), Japan 50% (95% CI 60%–42%), Palestine 16% (19%–14%) and Syria 12% (14%–10%)).68

Looking at the global picture, 26.4% of the adult population had hypertension in 2000 and in adults over the age of 25 years, the prevalence is estimated to be 40%.69 The prevalences reported in the papers we examined were generally higher than this in HIC and similar to this in LMIC (where whole population prevalences are reported). This could be due to the impact of experiencing a crisis, so called ‘disaster hypertension’ or due to overdiagnosis.13 It could also be due to more deprived populations at greatest risk of hypertension being situated in the most precarious areas of countries and cities.

Most of the papers included in this review did not compare the prevalence of hypertension in the crisis-affected population with that in a similar non-affected population. Post hoc comparison was considered using data from the Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network.68 There are differences in the definition of hypertension and challenges to matching the age stratification which made this difficult.

However, one paper did compare the risk of incident hypertension in those evacuated with those not evacuated from the area affected by the Great Japan Earthquake. The authors found that in men only there was a significantly increased risk of developing hypertension in those evacuated (HR 1.20 (1.07–1.35) p=0.003).51 This adds further evidence to the argument that exposure to natural disasters may be an independent risk factor for the development of hypertension. However, the demography and pre-existing burden of disease in Japan means that these findings cannot be readily applied to other earthquake-prone regions such as Nepal, Pakistan and Bangladesh.

The global distribution of included studies was uneven with Japanese, American and Syrian populations being relatively well researched. This poses an information challenge for those planning services in protracted refugee situations. Eleven of the 22 recognised protracted refugee situations are in Africa and 3 are in Asia.2 Global skewing in different directions was also seen in other systematic reviews, although our paper is unusual in also including findings from HIC.11 18 Despite there being a large number of studies featured in our review, there is still a need for more widespread work to address operational needs.

As seen in other reviews examining NCDs humanitarian settings11 18 21 22 24 the risk of bias in the majority of included studies was high. Overall this may be due to the challenges of designing studies and collecting data in resource poor settings. In this review we found that many of the sampling frames were not representative of the target populations. In addition, while a large number of studies examined the prevalence of multiple NCDs, the data available relating to each condition were limited; for example, few studies presented information about spread of data. The reporting of degree of exposure to crises was also varied. Some studies (mainly related to natural disasters) used evacuation status as a proxy measurement for high or low exposure to an event.70 On the other hand, much looser measures of exposure were used in other studies, such as refugee status or country of origin in which there was a crisis.31

In many studies the risk of bias was high because the authors used self-reporting of hypertension or a one-off BP measurement in order to diagnose hypertension. This issue was also noted in studies of diabetes.18 In both cases, this results in a poor understanding of the burden of disease. Diagnosis of hypertension is getting increasingly complex. Hypertension can be conceptualised as either a disease or risk factor and this can impact on the thresholds beyond which the diagnosis is made. Further there is a discussion about how best to measure BP and when to measure it. For example, ambulatory BP measurements are a better predictor of cardiovascular disease than clinic measurements and different thresholds are recommended for diagnosis with each tool.71 However there is an argument that taking a risk factor approach alone, particularly at lower risk thresholds, results in overdiagnosis and overtreatment.72 While this is problematic in any setting, it is particularly so in crises where resources are limited and medication supplies may be erratic.

Hypertension is one of several risk factors used to predict cardiovascular outcomes of interest (usually myocardial infarction, stroke or death). In their review on the impact of armed conflict on cardiovascular disease, Jawad et al found that there was consistent evidence across included studies for an increase in systolic BP, mortality from chronic ischaemic heart disease and unspecified heart disease. However, there was no consistent evidence for an increase in the diagnosis of hypertension.11 (Although we identified papers reporting on changes in BP, these were not included as the population were not identifiable as being hypertensive or otherwise.) Among other queries, this raises the question of whether the thresholds for diagnosing hypertension are correct for this population. Prediction modelling is one approach to setting diagnostic and treatment thresholds and is dependent on the availability of longitudinal data which follows the trajectory of individuals from the time they develop the risk factor to the point at which the outcome occurs.73 Although WHO has produced risk prediction charts for use in different geographical areas,74 these do not explicitly account for the potential effect of exposure to crises.

Despite the challenges of working in humanitarian settings, several agencies have produced guidelines for the identification and management of hypertension.75 Attempts have been made to apply the WHO’s Package of Non-communicable Disease Interventions in humanitarian settings76 and the Interagency Emergency Health Kit has included a supplementary module with antihypertensive medications since 2017.77 Although it is unclear how widely these are being used. Furthermore, in both chronic and acute crises, psychological distress is frequently reported.78 Stress in its various forms increases BP and there is emerging evidence that managing stress will decrease BP.79 In crises, this raises the question of the optimal mode of treatment, beyond the traditional biomedical model.

This review found relatively little data collected on the cascade of care; namely patient awareness of diagnosis, seeking treatment and achieving BP control. However, in keeping with a review of diabetes care in humanitarian settings,18 we found that where healthcare utilisation was evaluated, high proportions of patients would seek care.56 57 These data are important in identifying targets for system strengthening and more details may be available in unpublished service monitoring schemes. There have been some attempts to understand barriers to care, particularly in the Middle Eastern setting. While this can help to raise awareness of potential issues in other settings, such barriers will be highly context dependent.

Control, treatment and prevention of the negative consequences of hypertension can be framed as a complex intervention. Several components are needed beyond the provision of medication. For example, dietary changes, the ability to exercise and smoking cessation efforts all form part of the ideal package of care. Those affected by humanitarian situations typically have limited control over their ability to make healthy choices. As a result, policies ranging from the choice of food parcel being funded, to the establishment of safe spaces to exercise and consideration of the ease with which tobacco can be purchased, need to be considered through a health-promotion lens.80 81 Both qualitative and quantitative data are needed to develop an effective offer. WHO emphasises the importance of qualitative data to inform the values, acceptability, equity and feasibility implications of its guidelines.82 In particular qualitative research is critical in informing the implementation of evidence into practice83 if we do not know the meanings that patients attach to hypertension, we cannot hope to influence their behaviour or to develop services which will achieve penetration. Lastly, both qualitative and quantitative data are needed to adequately evaluate complex interventions.

At this time, the commitment to UHC, the global epidemiological transition and the changing demography of refugee populations has come together to focus the attention of WHO, UN and NGOs working in the health sphere on NCDs. As these agencies are developing and refining guidelines, it is critical that good quality qualitative and quantitative data be generated. Our review demonstrates a particular gap in qualitative and longitudinal research.

Strengths and limitations

There were several strengths to this review. Steps were taken to identify both published and grey literature which is important in these settings. A rigorous systematic approach was taken in the analysis and extraction of data.

There are also a number of limitations to this study. This review only considers studies published from 1 January 1999. This decision was made in order to provide an accurate estimate of the recent picture of hypertension and related health services. It does not, however, examine the effects of crises on subsequent peace-time generations. In addition, two studies could not be accessed for full-text screening.

While there were data available in some of the excluded studies that would have been relevant to the present study, the reporting of these data meant that the studies were not eligible for inclusion. Several studies that were excluded after full-text screening, for example, collected mixed data with adults and children and groups of refugees from multiple destinations. The results were reported in such a way that the groups could not be distinguished from each other and therefore the studies were excluded from the final synthesis.

Although several excluded studies did present qualitative outcomes, such as patient understanding of hypertension, and barriers and facilitators to accessing care, most of these were considered in the context of all patients with NCDs. As such the authors could not distinguish the patients with hypertension from those with other diseases. While some of these findings may have been relevant to populations with hypertension, they were not specific.

Finally, while the risk of bias tool used was appropriate for the study designs included, it did not distinguish between varying degrees of high risk of bias. Some studies, for instance, in the high risk of bias group used more robust methods than others.

Conclusion

This study supports previous scholarship in identifying the large burden of hypertension among populations affected by humanitarian crises. This suggests that service providers going into such scenarios should plan to see and treat hypertension. Further well-conducted and reported studies are needed to examine accurate prevalence of hypertension in specific regions and also to consider the cascade of care for patients with hypertension, patient knowledge and understanding of hypertension in order to better inform service provision for this large vulnerable patient group. Longitudinal studies may provide insight into the appropriate diagnostic and treatment thresholds for hypertension in prolonged crises.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Seye Abimbola

Contributors: FK, OO and JK—study conception and design. JK, OO, MM, WP, SS, AS and FK—acquisition of data. JK, OO and FK—analysis and interpretation of data. JK and FK—drafting of the manuscript. SS—creating images. JK, OO, SS, WP, MM and FK—critical revision.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: No data are available. Systematic review with no meta-analysis.

Supplemental material This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

References

- 1.World Health Organization World health statistics 2016: monitoring health for the SDGs sustainable development goals. World Health Organization, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Proulx M. What is a humanitarian emergency? Available: https://www.humanitariancoalition.ca/info-portal/factsheets/what-is-a-humanitarian-crisis [Accessed 26 Apr 2020].

- 3.UNHCR Global trends - forced displacement in 2018. Available: https://www.unhcr.org/5d08d7ee7.pdf [Accessed 5 Aug 2019].

- 4.IHME GBD compare [Internet]. Available: http://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare [Accessed 5 Aug 2019].

- 5.Aebischer Perone S, Martinez E, du Mortier S, et al. Non-communicable diseases in humanitarian settings: ten essential questions. Confl Health 2017;11:17. 10.1186/s13031-017-0119-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Slama S, Kim H-J, Roglic G, et al. Care of non-communicable diseases in emergencies. Lancet 2017;389:326–30. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31404-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spiegel PB, Checchi F, Colombo S, et al. Health-care needs of people affected by conflict: future trends and changing frameworks. Lancet 2010;375:341–5. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61873-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cooper K. The un high-level meeting on the prevention and control of NCDS (New York, 19–20 September 2011) and associated side-events, 2011. Available: https://ncdalliance.org/sites/default/files/resource_files/C3%20Report%20on%20Side%20Events.pdf [Accessed 5 Aug 2019].

- 9.Cooper K. NCD care in humanitarian settings: a clarion call to civil society, 2018. Available: https://www.rodekors.dk/sites/rodekors.dk/files/2018-10/NCD%20care%20in%20humanitarian%20settings%20-%20a%20clarion%20call%20to%20civil%20society.pdf [Accessed 5 Aug 2019].

- 10.WHO Universal health coverage (UHC). Available: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/universal-health-coverage-(uhc) [Accessed 5 Aug 2019].

- 11.Jawad M, Vamos EP, Najim M, et al. Impact of armed conflict on cardiovascular disease risk: a systematic review. Heart 2019;105:1388–94. 10.1136/heartjnl-2018-314459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hayman KG, Sharma D, Wardlow RD, et al. Burden of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality following humanitarian emergencies: a systematic literature review. Prehosp Disaster Med 2015;30:80–8. 10.1017/S1049023X14001356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kario K. Disaster hypertension. Circ J 2012;76:553–62. 10.1253/circj.CJ-11-1510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spruill TM. Chronic psychosocial stress and hypertension. Curr Hypertens Rep 2010;12:10–16. 10.1007/s11906-009-0084-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu M-Y, Li N, Li WA, et al. Association between psychosocial stress and hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurol Res 2017;39:573–80. 10.1080/01616412.2017.1317904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spruill TM, Butler MJ, Thomas SJ, et al. Association between high perceived stress over time and incident hypertension in black adults: findings from the Jackson heart study. J Am Heart Assoc 2019;8:e012139. 10.1161/JAHA.119.012139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Howard JT, Sosnov JA, Janak JC, et al. Associations of initial injury severity and posttraumatic stress disorder diagnoses with long-term hypertension risk after combat injury. Hypertension 2018;71:824–32. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.117.10496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kehlenbrink S, Smith J, Ansbro Éimhín, et al. The burden of diabetes and use of diabetes care in humanitarian crises in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2019;7:638–47. 10.1016/S2213-8587(19)30082-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greene MC, Kane JC, Khoshnood K, et al. Challenges and opportunities for implementation of substance misuse interventions in conflict-affected populations. Harm Reduct J 2018;15:58. 10.1186/s12954-018-0267-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ezard N. Substance use among populations displaced by conflict: a literature review. Disasters 2012;36:533–57. 10.1111/j.1467-7717.2011.01261.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lo J, Patel P, Roberts B. A systematic review on tobacco use among civilian populations affected by armed conflict. Tob Control 2016;25:129–40. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-052054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lo J, Patel P, Shultz JM, et al. A systematic review on harmful alcohol use among civilian populations affected by armed conflict in low- and middle-income countries. Subst Use Misuse 2017;52:1494–510. 10.1080/10826084.2017.1289411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weaver H, Roberts B. Drinking and displacement: a systematic review of the influence of forced displacement on harmful alcohol use. Subst Use Misuse 2010;45:2340–55. 10.3109/10826081003793920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Massey E, Smith J, Roberts B. Health needs of older populations affected by humanitarian crises in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Confl Health 2017;11:29. 10.1186/s13031-017-0133-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Naja F, Shatila H, El Koussa M, et al. Burden of non-communicable diseases among Syrian refugees: a scoping review. BMC Public Health 2019;19:637. 10.1186/s12889-019-6977-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, et al. Rayyan-a web and mobile APP for systematic reviews. Syst Rev 2016;5:210. 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoy D, Brooks P, Woolf A, et al. Assessing risk of bias in prevalence studies: modification of an existing tool and evidence of interrater agreement. J Clin Epidemiol 2012;65:934–9. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.CASP CASP checklists - CASP - Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. Available: https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/ [Accessed 4 Oct 2019].

- 30.Seers K. Qualitative systematic reviews: their importance for our understanding of research relevant to pain. Br J Pain 2015;9:36–40. 10.1177/2049463714549777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jen K-LC, Zhou K, Arnetz B, et al. Pre- and Post-displacement stressors and body weight development in Iraqi refugees in Michigan. J Immigr Minor Health 2015;17:1468–75. 10.1007/s10903-014-0127-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taylor EM, Yanni EA, Pezzi C, et al. Physical and mental health status of Iraqi refugees resettled in the United States. J Immigr Minor Health 2014;16:1130–7. 10.1007/s10903-013-9893-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Renzaho AMN, Bilal P, Marks GC. Obesity, type 2 diabetes and high blood pressure amongst recently arrived Sudanese refugees in Queensland, Australia. J Immigr Minor Health 2014;16:86–94. 10.1007/s10903-013-9791-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maldari T, Elsley N, Rahim RA, Abdul Rahim R. The health status of newly arrived Syrian refugees at the refugee health service, South Australia, 2016. Aust J Gen Pract 2019;48:480–6. 10.31128/AJGP-09-18-4696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burton LC, Skinner EA, Uscher-Pines L, et al. Health of medicare advantage plan enrollees at 1 year after Hurricane Katrina. Am J Manag Care 2009;15:13–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lipsitz JD, Zimmerman D, Kovalski N, et al. Chief complaints and diagnoses of displaced Israelis seeking medical treatment during the 2006 Israel-Lebanon war. Am J Disaster Med 2010;5:305–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nagai M, Ohira T, Takahashi H, et al. Impact of evacuation onstrends in the prevalence, treatment, and control of hypertension before and after a disaster. J Hypertens 2018;36:924–32. 10.1097/HJH.0000000000001626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ebner DK, Ohsawa M, Igari K, et al. Lifestyle-related diseases following the evacuation after the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant accident: a retrospective study of Kawauchi village with long-term follow-up. BMJ Open 2016;6:e011641. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Satoh H, Ohira T, Nagai M, et al. Prevalence of renal dysfunction among evacuees and non-evacuees after the great East earthquake: results from the Fukushima health management survey. Intern Med 2016;55:2563–9. 10.2169/internalmedicine.55.7023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rodriguez SR, Tocco JS, Mallonee S, et al. Rapid needs assessment of Hurricane Katrina evacuees-Oklahoma, September 2005. Prehosp Disaster Med 2006;21:390–5. 10.1017/S1049023X0000409X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vest JR, Valadez AM. Health conditions and risk factors of sheltered persons displaced by Hurricane Katrina. Prehosp Disaster Med 2006;21:55–8. 10.1017/S1049023X00003356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Doocy S, Sirois A, Tileva M, et al. Chronic disease and disability among Iraqi populations displaced in Jordan and Syria. Int J Health Plann Manage 2013;28:e1–12. 10.1002/hpm.2119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saadeh R, Qato D, Khader A, et al. Trends in the utilization of antihypertensive medications among Palestine refugees in Jordan, 2008-2012. J Pharm Policy Pract 2015;8:17. 10.1186/s40545-015-0036-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Saleh S, Alameddine M, Farah A, et al. eHealth as a facilitator of equitable access to primary healthcare: the case of caring for non-communicable diseases in rural and refugee settings in Lebanon. Int J Public Health 2018;63:577–88. 10.1007/s00038-018-1092-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vernier L, Cramond V, Hoetjes M, et al. High levels of mortality, exposure to violence and psychological distress experienced by the internally displaced population of ein Issa cAMP prior to and during their displacement in northeast Syria, November 2017. Confl Health 2019;13:33. 10.1186/s13031-019-0216-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Eryurt MA, Menet MG. Noncommunicable diseases among Syrian refugees in turkey: an emerging problem for a vulnerable group. J Immigr Minor Health 2020;22:44–9. 10.1007/s10903-019-00900-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chahda N, Sayah H, Strong J. Forgotten voices. An insight into older persons among refugees from Syria in Lebanon. Caritas Lebanon Migrant Centre, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Burger J, Gochfeld M, Lacy C. Ethnic differences in risk: experiences, medical needs, and access to care after Hurricane sandy in New Jersey. J Toxicol Environ Health A 2019;82:128–41. 10.1080/15287394.2019.1568329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.An K, Salyer J, Kao H-FS. Psychological strains, salivary biomarkers, and risks for coronary heart disease among Hurricane survivors. Biol Res Nurs 2015;17:311–20. 10.1177/1099800414551164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mobula LM, Fisher ML, Lau N, et al. Prevalence of hypertension among patients attending mobile medical clinics in the Philippines after Typhoon Haiyan. PLoS Curr 2016;8. 10.1371/currents.dis.5aaeb105e840c72370e8e688835882ce. [Epub ahead of print: 20 Dec 2016]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ohira T, Hosoya M, Yasumura S, et al. Evacuation and risk of hypertension after the great East Japan earthquake: the Fukushima health management survey. Hypertension 2016;68:558–64. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.116.07499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cetorelli V, Burnham G, Shabila N. Prevalence of non-communicable diseases and access to health care and medications among Yazidis and other minority groups displaced by Isis into the Kurdistan region of Iraq. Confl Health 2017;11:4. 10.1186/s13031-017-0106-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Khader A, Farajallah L, Shahin Y, et al. Hypertension and treatment outcomes in Palestine refugees in United nations relief and works agency primary health care clinics in Jordan. Trop Med Int Health 2014;19:1276–83. 10.1111/tmi.12356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Doocy S, Lyles E, Fahed Z, et al. Characteristics of Syrian and Lebanese diabetes and hypertension patients in Lebanon. Open Hypertens J 2018;10:60–75. 10.2174/1876526201810010060 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Doocy S, Lyles E, Hanquart B, et al. Prevalence, care-seeking, and health service utilization for non-communicable diseases among Syrian refugees and host communities in Lebanon. Confl Health 2016;10:21. 10.1186/s13031-016-0088-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rehr M, Shoaib M, Ellithy S, et al. Prevalence of non-communicable diseases and access to care among non-cAMP Syrian refugees in northern Jordan. Confl Health 2018;12:33. 10.1186/s13031-018-0168-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Doocy S, Lyles E, Akhu-Zaheya L, et al. Health service utilization among Syrian refugees with chronic health conditions in Jordan. PLoS One 2016;11:e0150088. 10.1371/journal.pone.0150088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kayali M, Moussally K, Lakis C, et al. Treating Syrian refugees with diabetes and hypertension in Shatila refugee cAMP, Lebanon: Médecins sans Frontières model of care and treatment outcomes. Confl Health 2019;13:12. 10.1186/s13031-019-0191-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sun X-C, Zhou X-F, Chen S, et al. Clinical characteristics of hypertension among victims in temporary shield district after Wenchuan earthquake in China. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2013;17:912–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Krousel-Wood MA, Islam T, Muntner P, et al. Medication adherence in older clinic patients with hypertension after Hurricane Katrina: implications for clinical practice and disaster management. Am J Med Sci 2008;336:99–104. 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e318180f14f [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Khader A, Farajallah L, Shahin Y, et al. Cohort monitoring of persons with hypertension: an illustrated example from a primary healthcare clinic for Palestine refugees in Jordan. Trop Med Int Health 2012;17:1163–70. 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2012.03048.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Balcilar M. Non-communicable disease risk factors surveillance among Syrian refugees living in turkey. AFAD, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Doocy S, Lyles E, Roberton T, et al. Syrian refugee health access survey in Jordan. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Islam T, Muntner P, Webber LS, et al. Cohort study of medication adherence in older adults (CoSMO): extended effects of Hurricane Katrina on medication adherence among older adults. Am J Med Sci 2008;336:105–10. 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e318180f175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Arrieta MI, Foreman RD, Crook ED, et al. Providing continuity of care for chronic diseases in the aftermath of Katrina: from field experience to policy recommendations. Disaster Med Public Health Prep 2009;3:174–82. 10.1097/DMP.0b013e3181b66ae4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Baxter LM, Eldin MS, Al Mohammed A, et al. Access to care for non-communicable diseases in Mosul, Iraq between 2014 and 2017: a rapid qualitative study. Confl Health 2018;12:48. 10.1186/s13031-018-0183-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Doocy S, Lyles E, Roberton T, et al. Prevalence and care-seeking for chronic diseases among Syrian refugees in Jordan. BMC Public Health 2015;15:1097. 10.1186/s12889-015-2429-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network Global burden of disease study 2017 (GBD 2017) results. Seattle, United States: Institute for health metrics and evaluation (IHME), 2018. Available: http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool [Accessed 2 May 2020].

- 69.Kearney PM, Whelton M, Reynolds K, et al. Global burden of hypertension: analysis of worldwide data. Lancet 2005;365:217–23. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17741-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sakai A, Nakano H, Ohira T, et al. Persistent prevalence of polycythemia among evacuees 4 years after the Great East Japan Earthquake: A follow-up study. Prev Med Rep 2017;5:251–6. 10.1016/j.pmedr.2017.01.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schwartz CL, McManus RJ. What is the evidence base for diagnosing hypertension and for subsequent blood pressure treatment targets in the prevention of cardiovascular disease? BMC Med 2015;13:256. 10.1186/s12916-015-0502-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Haase CB, Gyuricza JV, Brodersen J. New hypertension guidance risks overdiagnosis and overtreatment. BMJ 2019;365:l1657. 10.1136/bmj.l1657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Steyerberg EW. Clinical prediction models: a practical approach to development, validation, and updating. Springer Science & Business Media, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 74.WHO/ISH WHO/ISH risk prediction charts. Available: https://www.who.int/ncds/management/WHO_ISH_Risk_Prediction_Charts.pdf?ua=1 [Accessed 30 Apr 2020].

- 75.Albajar P, Frontières MS. Clinical guidelines: diagnostic and treatment manual; for curative programmes in hospitals and dispensaries; guidance for prescribing, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Martinez RE, Quintana R, Go JJ, et al. Use of the who package of essential noncommunicable disease interventions after Typhoon Haiyan. WPSAR 2015;6:18–20. 10.5365/wpsar.2015.6.3.HYN_024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.WHO Interagency emergency health kit 2017. Available: https://www.who.int/emergencies/kits/iehk/en/ [Accessed 3 May 2020].

- 78.Silove D, Ventevogel P, Rees S. The contemporary refugee crisis: an overview of mental health challenges. World Psychiatry 2017;16:130–9. 10.1002/wps.20438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Linden W, Lenz JW, Con AH. Individualized stress management for primary hypertension: a randomized trial. Arch Intern Med 2001;161:1071–80. 10.1001/archinte.161.8.1071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Basu S, Yudkin JS, Berkowitz SA, et al. Reducing chronic disease through changes in food aid: a microsimulation of nutrition and cardiometabolic disease among Palestinian refugees in the middle East. PLoS Med 2018;15:e1002700. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Roberts B, Patel P, McKee M. Noncommunicable diseases and post-conflict countries. Bull World Health Organ 2012;90:2, 2A. 10.2471/BLT.11.098863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Downe S, Finlayson KW, Lawrie TA, et al. Qualitative evidence synthesis (QES) for guidelines: paper 1 – using qualitative evidence synthesis to inform guideline scope and develop qualitative findings statements. Health Res Policy Syst 2019;17 10.1186/s12961-019-0467-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Glenton C, Lewin S, Lawrie TA, et al. Qualitative evidence synthesis (QES) for guidelines: paper 3 – using qualitative evidence syntheses to develop implementation considerations and inform implementation processes. Health Res Policy Syst 2019;17 10.1186/s12961-019-0450-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gómez-Restrepo C, Rincón CJ, Medina-Rico M. [Chronic diseases in the population affected by the armed conflict in Colombia, 2015]. Rev Panam Salud Publica 2018;41:e144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Furusawa T, Furusawa H, Eddie R, et al. Communicable and non-communicable diseases in the Solomon Islands villages during recovery from a massive earthquake in April 2007. N Z Med J 2011;124:17–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Vanasse A, Cohen A, Courteau J, et al. Association between floods and acute cardiovascular diseases: a population-based cohort study using a geographic information system approach. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2016;13:168. 10.3390/ijerph13020168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hayashi Y, Nagai M, Ohira T, et al. The impact of evacuation on the incidence of chronic kidney disease after the great East Japan earthquake: the Fukushima health management survey. Clin Exp Nephrol 2017;21:995–1002. 10.1007/s10157-017-1395-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hoshide S, Nishizawa M, Okawara Y, et al. Salt intake and risk of disaster hypertension among Evacuees in a shelter after the great East Japan earthquake. Hypertension 2019;74:564–71. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.119.12943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]