The HIV-1 Env cytoplasmic tail (CT) is required for efficient Env incorporation into nascent particles and viral transmission in primary CD4+ T cells. The MT-4 T-cell line has been reported to support multiple rounds of infection of HIV-1 encoding a gp41 CT truncation. Uncovering the underlying mechanism of MT-4 T-cell line permissivity to gp41 CT truncation would provide key insights into the role of the gp41 CT in HIV-1 transmission. This study reveals that multiple factors contribute to the unique ability of a gp41 CT truncation mutant to spread in cultures of MT-4 cells. The lack of a requirement for the gp41 CT in MT-4 cells is associated with the combined effects of rapid HIV-1 protein production, high levels of cell-surface Env expression, and increased susceptibility to cell-to-cell transmission compared to nonpermissive cells.

KEYWORDS: HIV-1, Env, gp41, cytoplasmic tail, virological synapse, transmission, HTLV-1, Tax

ABSTRACT

HIV-1 encodes an envelope glycoprotein (Env) that contains a long cytoplasmic tail (CT) harboring trafficking motifs implicated in Env incorporation into virus particles and viral transmission. In most physiologically relevant cell types, the gp41 CT is required for HIV-1 replication, but in the MT-4 T-cell line the gp41 CT is not required for a spreading infection. To help elucidate the role of the gp41 CT in HIV-1 transmission, in this study, we investigated the viral and cellular factors that contribute to the permissivity of MT-4 cells to gp41 CT truncation. We found that the kinetics of HIV-1 production and virus release are faster in MT-4 than in the other T-cell lines tested, but MT-4 cells express equivalent amounts of HIV-1 proteins on a per-cell basis relative to cells not permissive to CT truncation. MT-4 cells express higher levels of plasma-membrane-associated Env than nonpermissive cells, and Env internalization from the plasma membrane is less efficient than that from another T-cell line, SupT1. Paradoxically, despite the high levels of Env on the surface of MT-4 cells, 2-fold less Env is incorporated into virus particles produced from MT-4 than SupT1 cells. Contact-dependent transmission between cocultured 293T and MT-4 cells is higher than in cocultures of 293T with most other T-cell lines tested, indicating that MT-4 cells are highly susceptible to cell-to-cell infection. These data help to clarify the long-standing question of how MT-4 cells overcome the requirement for the HIV-1 gp41 CT and support a role for gp41 CT-dependent trafficking in Env incorporation and cell-to-cell transmission in physiologically relevant cell lines.

IMPORTANCE The HIV-1 Env cytoplasmic tail (CT) is required for efficient Env incorporation into nascent particles and viral transmission in primary CD4+ T cells. The MT-4 T-cell line has been reported to support multiple rounds of infection of HIV-1 encoding a gp41 CT truncation. Uncovering the underlying mechanism of MT-4 T-cell line permissivity to gp41 CT truncation would provide key insights into the role of the gp41 CT in HIV-1 transmission. This study reveals that multiple factors contribute to the unique ability of a gp41 CT truncation mutant to spread in cultures of MT-4 cells. The lack of a requirement for the gp41 CT in MT-4 cells is associated with the combined effects of rapid HIV-1 protein production, high levels of cell-surface Env expression, and increased susceptibility to cell-to-cell transmission compared to nonpermissive cells.

INTRODUCTION

HIV-1 Env is initially synthesized in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) as a polyprotein precursor, gp160. The gp160 monomers oligomerize into predominantly trimers in the ER before transport to the Golgi (1). Once in the Golgi, gp160 trimers are cleaved by furin to generate the mature surface Env subunit gp120 and the transmembrane subunit gp41 (2). The two subunits are noncovalently linked to form a trimeric gp120:gp41 heterodimer in the functional Env glycoprotein complex (3, 4). The mature, trimeric Env complex traffics via the secretory pathway to the plasma membrane (PM), the site of viral assembly and budding. Env is expressed on the surface of infected cells and is incorporated into virus particles, where it is embedded in the viral envelope (for review, see reference 5).

The two subunits of Env are responsible for different functions of the glycoprotein complex. The gp120 subunit promotes particle attachment and entry by binding to receptor (CD4) and coreceptor (CXCR4 or CCR5). The gp41 subunit comprises three domains: an ectodomain that associates with gp120 and contains the determinants critical for membrane fusion, a transmembrane domain that anchors Env in the lipid bilayer, and a cytoplasmic tail (CT) that regulates a number of aspects of Env function (6). While the principal functions of the Env complex are well characterized, and it is clear that the gp41 CT regulates Env incorporation into virions, the precise role of the CT in Env biology remains poorly understood.

HIV-1 and other retroviruses are transmitted to target cells in vitro and in vivo via either cell-free or cell-to-cell (C-C) infection (for review, see reference 7). Cell-free infection occurs when virions that are not associated with the virus-producing cell bind and enter uninfected target cells. C-C infection is defined as direct transmission of nascent particles at points of contact, known as infectious or virological synapses (VSs), between infected and uninfected cells (8–10). Studies have established that, in vitro, viral dissemination by C-C transmission is a highly efficient mode of viral transfer relative to cell-free infection (11, 12). However, the relative contribution of cell-free versus C-C transmission to viral spread in vivo is less clear. In most cell types, viral transmission requires CT-dependent localization of Env to viral assembly sites (13–16) and Env binding to CD4 and coreceptor. A hallmark of C-C spread is the accumulation of viral proteins, in particular, Gag and Env, at the VS (10, 14, 17–19). How Env is directed to the VS is not well understood; further elucidation of this process is fundamental to our ability to design therapies capable of blocking C-C transmission.

The lentiviral gp41 CT is very long compared to those of other retroviruses; it contains ∼150 amino acids in the case of HIV-1 and ∼164 amino acids in the case of simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV). The lentiviral gp41 CT harbors trafficking motifs implicated in Env recycling, incorporation, and viral transmission, and in maintaining low levels of Env on the surface of infected cells (for reviews, see references 5 and 20–22). One such trafficking motif is the highly conserved YxxΦ motif (with Φ representing a hydrophobic amino acid) (23–25) known to interact with host cell clathrin-adaptor protein complex 2 (AP-2) and mediate fast internalization of HIV-1 and SIV Env via clathrin-mediated endocytosis (26–30). The gp41 CT contains several other well-conserved tyrosine and dileucine motifs that may also play a role in Env trafficking and subcellular localization (26–28, 31–33). The high degree of conservation in both the length of the gp41 CT and the YxxΦ motif suggests that these features play key roles in lentiviral transmission. It is currently unclear whether Env recycling from the PM is a requisite step in Env incorporation into the assembling Gag lattice. Recent evidence suggests a role for recycling in Env incorporation (33, 34), and many studies have explored the role of trafficking motifs in the gp41 CT in promoting the proper spatiotemporal localization of Env during assembly (5, 20, 21, 35), but the role of Env recycling in Env incorporation is not well defined.

Wild-type (WT) HIV-1 has an average of ∼10 Env trimers per virion (36), and truncation of the gp41 CT generally results in a 10-fold decrease in Env incorporation in physiologically relevant cell types (which we refer to as being nonpermissive to gp41 CT truncation) (37). The sparsity of Env on HIV-1 particles suggests that Env incorporation is tightly regulated. The degree of regulation seems to be cell-type and CT dependent. For example, in the nonpermissive T-cell line CEM-A, WT Env is localized at the neck of the budding particle, while truncation of the gp41 CT results in a more uniform Env distribution around the virus particle (35). In the permissive COS7 fibroblast-like cell line, both WT and CT-truncated Env are evenly distributed around the virus particle. CT-dependent endocytosis of WT Env from the PM is more active in CEM-A than in COS7, suggesting that Env recycling regulates Env distribution on the virus particle. Importantly, in both cell lines, incorporation of the gp41 CT-truncated mutant was reduced compared to the WT, consistent with the essential role for the CT in trapping Env in the assembling Gag lattice (38). These data highlight the multifaceted role of the gp41 CT in regulating Env incorporation and the cell-type-dependent utilization of the CT in viral assembly.

A functional interaction between the gp41 CT and the matrix (HIV-1 matrix protein [MA]) domain of the Gag polyprotein has been postulated to play an important role in capturing Env during viral assembly (for reviews, see references 39–41). Compelling evidence for the trapping of the gp41 CT by the Gag lattice has been previously demonstrated by various studies showing the clustering of Env trimers at sites of virus assembly (13, 15, 35, 38) and retention of full-length Env, but not CT-truncated Env, in detergent-stripped Gag virus-like particles (42). Further evidence for the trapping of the gp41 CT by the Gag lattice is provided by the ability of single amino acid changes in MA to block WT Env incorporation (43–50). Truncation of the gp41 CT reverses the Env incorporation block imposed by these point mutations in MA (43, 46, 48, 50). Similarly, Env incorporation is inhibited by small intragenic deletions in MA or deletion of the globular domain of MA, and this inhibition is relieved by truncation of the gp41 CT (48, 51). Highlighting the importance of MA-gp41 CT interactions, a small deletion in the gp41 CT that inhibits Env incorporation is rescued by a single amino acid change in MA (52). Further underscoring the intimate relationship between MA and the gp41 CT, truncation of the gp41 CT abrogates Gag’s ability to repress premature fusion of Env with the target cell membrane (15, 53, 54). Recent studies have demonstrated an important role for trimerization of the MA domain of Gag in the formation of a Gag lattice that accommodates the long gp41 CT during Env incorporation (44, 45, 55). While evidence of the relationship between the gp41 CT and MA is well appreciated, the precise mechanism of how Env is incorporated into the assembling Gag lattice is not well understood.

Our understanding of the function of the gp41 CT and MA in Env incorporation suggests four general models of Env incorporation: (i) passive incorporation (Env incorporation does not require its concentration at assembly sites), (ii) Gag-Env cotargeting (Gag and Env are both targeted to an assembly platform, such as a membrane microdomain), (iii) direct Gag-Env interaction (Gag directly binds the gp41 CT, thereby capturing it into assembling virions), and (iv) indirect Gag-Env interaction (a host factor serves as a bridge between Gag and Env for the capture of Env by the assembling Gag lattice) (5, 39). These models are not mutually exclusive; for example, Env could colocalize with Gag at sites of virus assembly and then be captured by the Gag lattice via direct interactions between MA and the gp41 CT, and other combinations of these models can be readily envisioned. Interestingly, even foreign viral glycoproteins have been shown to cluster at HIV-1 assembly sites in the context of pseudotype particle formation (56, 57).

The unusual ability of certain T-cell lines (notably MT-4, C8166, and M8166) to be highly susceptible to HIV-1 infection and permissive to loss of certain viral protein functions is incompletely understood. In particular, MT-4 cells are known to be permissive, relative to other T-cell lines, to deletion of the gp41 CT (19, 37, 46, 48, 50, 55, 58–62), loss of integrase (IN) function (63, 64), disruption of proper capsid (HIV-1 capsid protein [CA]) multimerization (65), deletion of Nef (66), and a large MA deletion (51). A functional IN protein is required for productive HIV-1 replication in a majority of cell lines and human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (hPBMCs) (64). MT-4 and C8166 cells are known to be permissive to type I IN mutations (mutations in IN that specifically block viral DNA integration into the host cell genome), while Jurkat E6.1 cells and hPBMCs are nonpermissive to defects in integration (64). It was recently reported that MT-4 and C8166 cells are likely permissive to type I IN mutations due to human T-cell leukemia virus 1 (HTLV-1) Tax expression inducing NF-κB protein recruitment to the HIV-1 long terminal repeat (LTR) on unintegrated HIV-1 DNA (63). Furthermore, it was previously suggested by Emerson et al. (19) that HTLV-1 Tax expression may contribute to MT-4 cell permissivity by causing potent and chronic activation of NF-κB signaling (67), resulting in transactivation of the HIV-1 LTR (68). The ability of MT-4 cells to support rapid replication of HIV-1 and gain second-site compensatory mutations unlikely to be acquired in less-permissive cells has led to the use of this cell line for selection experiments with a wide variety of defective MA and CA mutants (46, 65, 69–71). Uncovering the underlying mechanisms of MT-4 cell line permissivity is important because of the frequent use of this cell line in HIV-1 replication studies (16, 72–74).

In this study, we examined a number of factors involved in viral replication and spread in cells both permissive (i.e., MT-4) and nonpermissive (i.e., all other T-cell lines tested) for gp41 CT truncation. Our results show that HTLV-1 Tax expression is not the sole determinant of permissivity to gp41 CT truncation. Rather, high surface Env expression, rapid kinetics of HIV protein production and virus release, and efficient C-C transmission likely contribute to the MT-4 cell permissivity to CT-truncation.

RESULTS

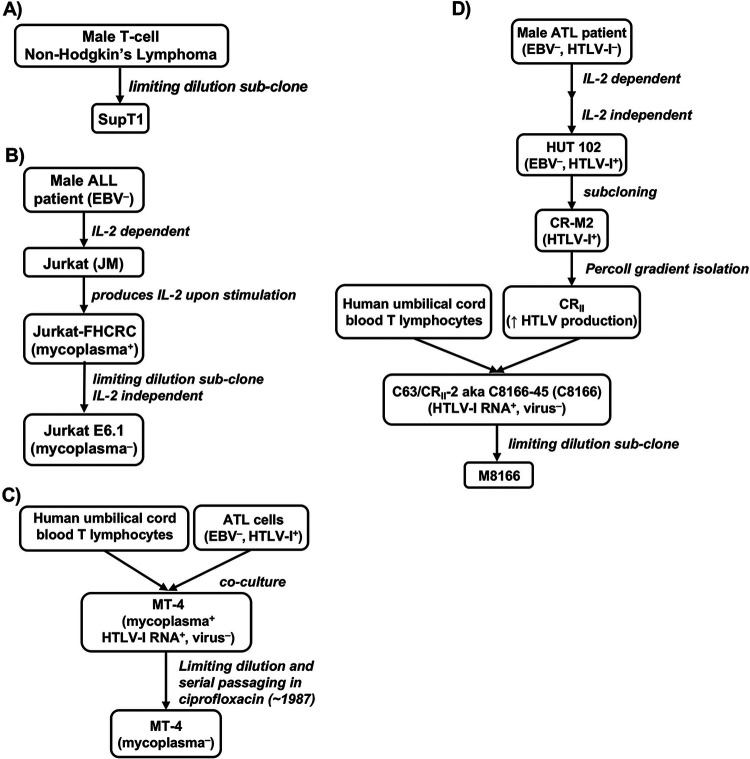

Lineage and validation of cell lines used to interrogate T-cell line permissivity to replication of an HIV-1 mutant lacking the gp41 CT.

To investigate the mechanistic basis for the permissivity of MT-4 cells to replication of a gp41 CT-truncation mutant, a panel of five T-cell lines were selected based on their origins (Fig. 1) and previously reported permissivity, or lack thereof, to gp41 CT truncation. Previous studies have reported that MT-4 (19, 37, 46, 48, 50, 55, 58–62) and M8166 (75) cells are permissive to truncation of the gp41 CT, and it is established that hPBMCs, SupT1, and Jurkat E6.1 are not permissive (19, 37). Therefore, two HTLV-1– lymphoma-derived cell lines, SupT1 (76) and Jurkat E6.1 (77) (Fig. 1A and B) and three HTLV-1-transformed lines, MT-4 (78), C8166 (79), and M8166 (Fig. 1C and D), were selected for this study. The cell line lineage and HTLV-1 particle and RNA production status of each cell line are shown in Fig. 1. C8166, M8166, and MT-4 cells all express HTLV-1 RNA but do not produce viral particles. Due to the presence of HTLV-1 RNA, they do express the HTLV-1 Tax protein (60, 80, 81). SupT1 and Jurkat E6.1 cells do not express HTLV-1 RNA or proteins (76, 77).

FIG 1.

Lineage of cell lines used to interrogate T-cell line permissivity to replication of an HIV-1 mutant lacking the gp41 CT. (A) The SupT1 T-cell line was derived from a pleural effusion of a male patient with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Cells were subcloned by limiting dilution to generate a cell line capable of continual growth from a single-cell colony (76). (B) The peripheral blood of a 14-year-old boy with relapsed acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL) was used to generate the EBV–, IL-2-dependent JM T-cell line (77). The JM line was then subcloned to generate the Jurkat-FHCRC subclone for its ability to produce IL-2 upon stimulation with phorbol esters or lectins (116). The “-FHCRC” designation indicates the cell line originated at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center. Jurkat-FHCRC was then subjected to limiting dilution to generate an IL-2 -independent, mycoplasma-free cell line, Jurkat E6.1 (117). (C) To generate the MT-4 cell line, cells from an adult male ATL patient were cocultured with male human infant cord leukocytes, and therefore it is unknown whether these cells are of cord leukocyte or ATL cell origin (78). Cells were gifted to the lab of Douglas Richman by Harada et al. (118) and serially passaged by terminal dilution cloning of the cells in the presence of ciprofloxacin until they were determined to be mycoplasma free. These cells were then donated to the NIH ARP by Douglas Richman (D. Richman, personal communication). (D) To generate the C8166 T-cell line, cells were first acquired from a 26-year-old male ATL patient’s inguinal lymph node (119) and maintained in IL-2 for several passages until they were deemed IL-2 independent (120). This T-cell line, HUT 102, was determined to be EBV– and HTLV+. The CR-M2 subclone of HUT 102 was then isolated and further purified by percoll gradient isolation to generate a cell line with increased HTLV production, designated CRII (121). CRII was then used to transform human umbilical cord blood T leukocytes by cell hybridization to generate the C63/CRII-2 cell line, also known as (aka) the C8166-45 (aka 81-66 or C8166) cell line (79). The “-45” designation indicates the cell line has 45 chromosomes. “CR” indicates the cells were transformed by the HTLV-1CR virus. Characterization of this line found that it produces HTLV-1 RNA but no virus particles (79). C8166 cells were then subjected to limiting dilution to generate a clone more susceptible to formation of syncytia when cultures were infected with HIV-1 (122). This new C8166-derived cell line was named M8166.

Short tandem repeat (STR) profiling was utilized to validate the identity of all the cell lines in our T-cell panel by comparing the allele calls between the cells and the published STR profile on the Cellosaurus database (Table 1). The MT-4 cell STR profile, recently validated by functional assays, morphological analysis, and assessment of HTLV-1 Tax protein expression (60), was an exact match to the Cellosaurus reference profile (Table 1). Jurkat E6.1 and SupT1 cell line STR profiles were both close matches to the published STR profiles. The STR profile revealed some genetic instability in SupT1 compared to the SupT1-CCR5 cell line, indicated by the presence of extra, lower-intensity alleles at several gene loci (data not shown). Overall, the STR profile of our SupT1 cell line was a 95% match to the SupT1-CCR5 cell line, confirming the identity of our laboratory SupT1 line. The Jurkat E6.1 cell line also displayed some genetic instability (data not shown), which accounts for its imperfect match to the Cellosaurus reference profile.

TABLE 1.

T-cell line STR profiles

| Genetic loci | Jurkat E6.1 | MT-4 | C8166, M8166 | SupT1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| D3S1358 | 15, 17 | 17 | 15,16 | 16, 17, 18, 19 |

| TH01 | 6, 9.3 | 7 | 6, 9.3 | 9.3 |

| D21S11 | 30.2, 31.2, 33.2 | 28, 30.3 | 27, 30 | 28, 31, 32, 33 |

| D18S51 | 12, 13, 20, 21 | 13 | 14, 17 | 13, 14 |

| Penta E | 10, 12 | 5, 15 | 7, 11 | 13, 14, 16 |

| D5S818 | 9 | 10, 11 | 12 | 11 |

| D13S317 | 8, 12 | 12 | 10, 11 | 10, 11, 12 |

| D7S820 | 8, 12 | 8, 10 | 9, 10 | 11 |

| D16S539 | 11 | 9, 12 | 12, 13 | 9, 12 |

| CSF1PO | 10, 11, 12, 13 | 11, 12 | 10 | 10, 11, 12 |

| Penta D | 11, 13 | 10, 13 | 11, 15 | 12 |

| vWA | 18, 19 | 17, 18 | 15, 16 | 16,17,18, 19 |

| D8S1179 | 12, 13, 14, 15 | 10, 15 | 11, 14 | 13,14 |

| TPOX | 8, 10 | 11 | 11 | 9 |

| FGA | 20, 21 | 23 | 21, 22 | 19, 20, 21 |

| AMEL | X, Y | X, Y | X, Y | X, Y |

| Percentage match to Cellosaurus database | 87.88 | 100 | 98.31 | 82.35 |

| Source | NIH-ARP | NIH-ARP | NIH-ARP | Unknown |

| Catalog no. | 177 | 120 | 404 and 11395 |

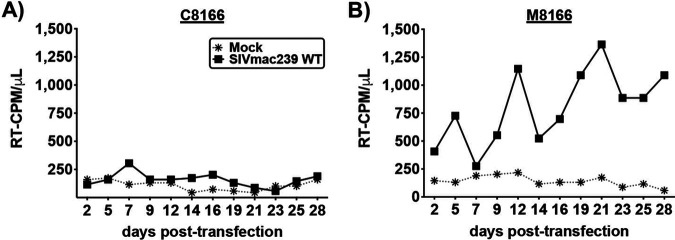

M8166 is a subclone of the C8166 cell line (Fig. 1D), and therefore these two lines share the same STR profile (Table 1), which was an ∼98% match to the cell line profile published in the Cellosaurus database and in a separate report (82). To further confirm the identity of the M8166 and C8166 cell lines, they were assessed for their capacity to host replication of WT SIVmac239 (Fig. 2). The C8166 line has been reported to exhibit a block to efficient SIV replication (83), whereas M8166 is reportedly capable of hosting multiple rounds of SIVmac239 replication (84). Consistent with these reports, SIVmac239 did not establish a spreading infection in C8166 (Fig. 2A), while it did in M8166 cells (Fig. 2B). Together, the STR profile and capacity of M8166, but not C8166, cells to support multiple rounds of SIVmac239 replication confirm the identity of the C8166 and M8166 cell lines used in this study.

FIG 2.

Spreading infection kinetics of SIVmac239 in C8166 and M8166. (A) C8166 and (B) M8166 were transfected with SIVmac239 encoding the indicated Env CT genotype. Supernatant was sampled every 2 to 3 days for analysis by HIV-1 RT assay, and cell cultures were split 1/2. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments.

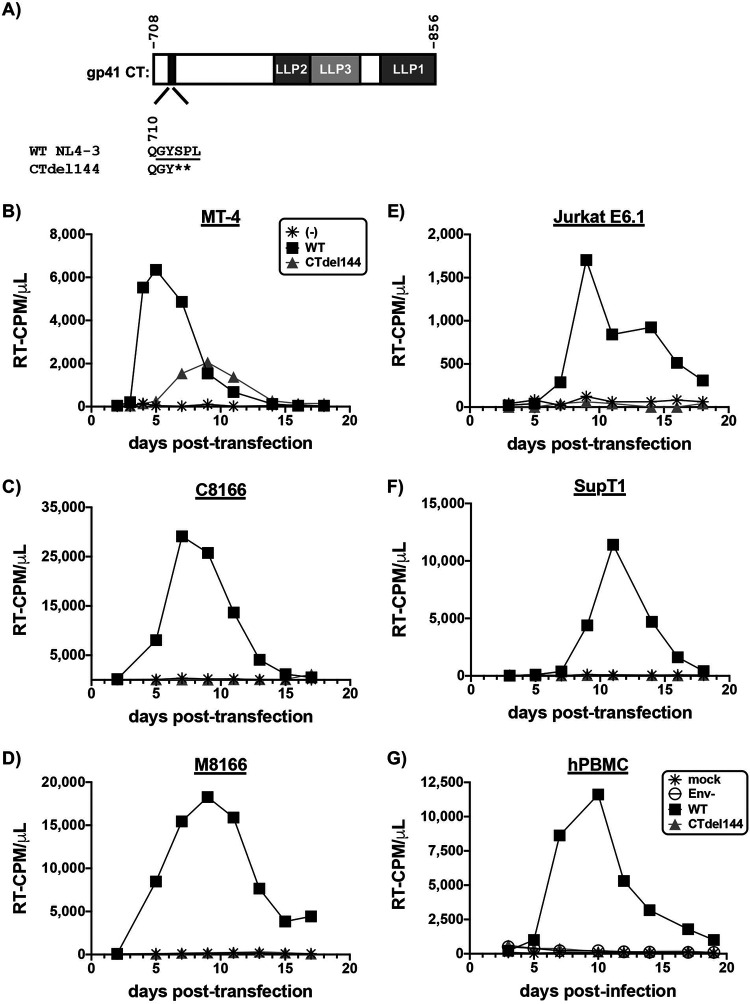

MT-4 is the only T-cell line tested in this study that is permissive to the gp41 CT truncation mutant CTdel144.

HIV-1 replication in most T-cell lines is abrogated by truncation of the gp41 CT (19, 37), but several studies have demonstrated that the MT-4 cell line is able to propagate a gp41 CT-deleted mutant (19, 37, 46, 48, 50, 55, 58–62). To evaluate the ability of the CTdel144 mutant, which lacks 144 amino acids from the gp41 CT (43), to replicate in HTLV-1-transformed T-cell lines, MT-4, C8166, and M8166 cells were transfected with the WT pNL4-3 molecular clone or the CTdel144 derivative to initiate a spreading infection (Fig. 3A). MT-4 cells (Fig. 3B to D) supported rapid WT HIV-1 replication with supernatant HIV-1 reverse transcriptase (RT) activity detectable within 2 days posttransfection and peaking 5 days posttransfection (Fig. 3B). Replication of WT HIV-1 in M8166 and C8166 cells peaked between 7 and 9 days posttransfection. Replication of HIV-1 in T-cell lines not permissive to truncation of the gp41 CT—or in phytohemagglutinin (PHA)-activated PBMCs isolated from healthy donors—was markedly slower than in MT-4 cells (Fig. 3C to G compared to Fig. 3B). Consistent with previous reports (19, 37, 46, 48, 50, 55, 58–62), the MT-4 cell line supported replication of the CTdel144 mutant. In contrast, neither of the other two HTLV-1-transformed T-cell lines (C8166 and M8166), the two HTLV-1– lymphoma-derived cell lines (SupT1 and Jurkat E6.1), or hPBMCs supported replication of CTdel144 (Fig. 3B compared to Fig. 3C to G). Therefore, under these standard conditions, MT-4 is unique among the T-cell lines tested here in its capacity to support multiple rounds of CTdel144 replication.

FIG 3.

MT-4 is the only T-cell line tested that is permissive to the gp41 CT truncation mutant CTdel144. (A) Schematic representation of the NL4-3 gp41 CT and gp41 CT genotypes used in this study. The lentiviral lytic peptide (LLP) domains are indicated in gray boxes, and the highly conserved tyrosine endocytosis motif is indicated with a shaded black rectangle. The CTdel144 mutant was generated by introducing two stop codons in the highly conserved tyrosine endocytosis motif, resulting in a CT of 4 amino acids (43). The numbers above the gp41 CT schematic indicate the first and last amino acid positions of the gp41 CT. The number below the gp41 CT indicates the position of the QGYSPL sequence. The tyrosine endocytosis motif, GYSPL, is underlined. (B to G) Replication curves for spreading infection are shown. (B to F) Cell lines were either mock transfected or transfected with pNL4-3 encoding the indicated gp41 CT genotype. Cells were split (B to D) 1/2 or (E to F) 1/3 every 2 to 3 days, and an aliquot of the supernatant was reserved for analysis of HIV-1 RT activity at each time point. (G) hPBMCs were transduced with VSV-G-pseudotyped NL4-3 encoding the indicated gp41 CT genotype or mock infected. Supernatant was sampled every 2 to 3 days for analysis of HIV-1 RT activity, and cell cultures were supplemented with fresh medium. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments (B to F) and 3 donors (G).

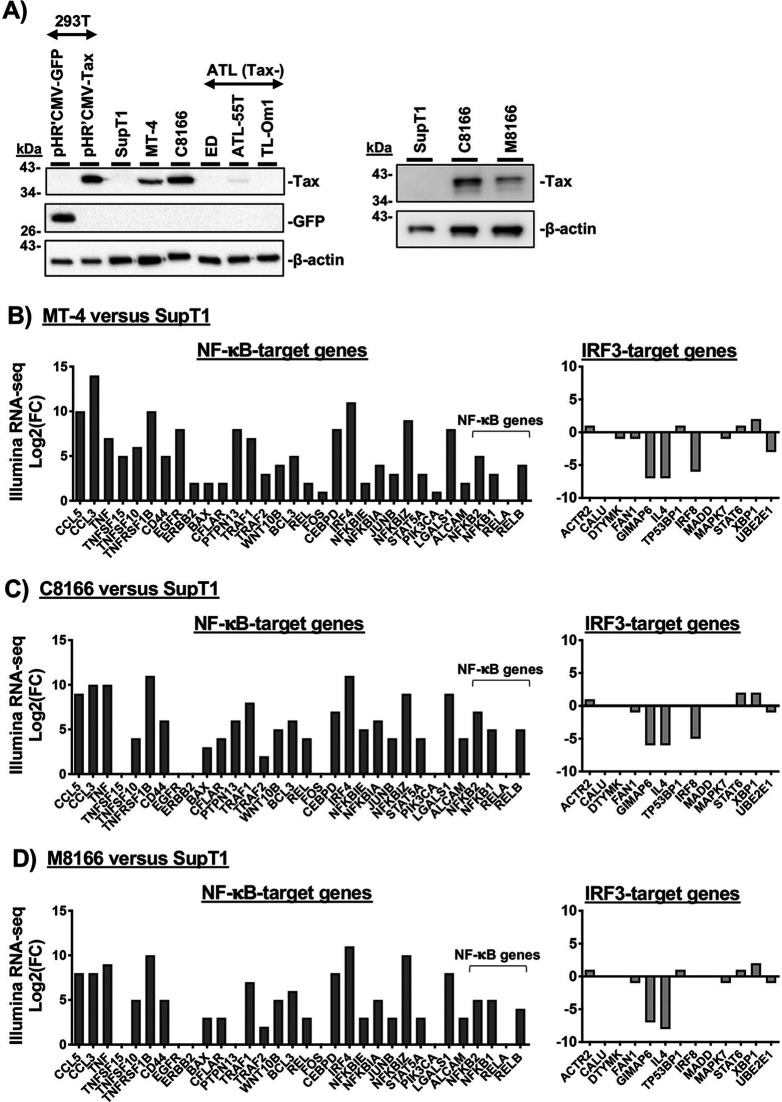

NF-κB-target gene expression in Tax-expressing T-cell lines is higher than in SupT1.

To determine the relative levels of Tax expression in MT-4, C8166, and M8166 cells, Western blot analysis of cell lysates was performed (Fig. 4A). To control for antibody specificity, two sets of controls were included: (i) a panel of adult T-cell leukemia (ATL) cells previously reported to have lost Tax expression (85) and (ii) 293T cells transfected with a Tax expression vector (Fig. 4A). Western blot analysis indicated that C8166 expressed substantially more Tax protein than MT-4 or M8166 cells, while a small amount of Tax expression in the ATL-55T-cell line was detectable.

FIG 4.

NF-κB-target gene expression in Tax-expressing T-cell lines is higher than in SupT1. (A) Cell lysates from the indicated cell lines were analyzed by Western blotting for HTLV-1 Tax expression. 293T cells were transfected with a GFP expression vector as a transfection control or a Tax expression vector as a control for antibody specificity. ATL Tax-deficient cells were included as the negative control for Tax expression in immortalized T-cell lines. (B to D) RNA levels of the indicated NF-κB- and IRF3-target genes were compared to SupT1. RNA levels were determined by Illumina RNA-seq. As described in more detail in Materials and Methods, comparisons are reported as the log2 of the fold change (FC) of the HTLV-transformed line (MT-4, C8166, or M8166) relative to the lymphoma-derived T-cell line, SupT1.

Tax is a known oncogene whose expression induces rapid senescence through potent and persistent NF-κB hyperactivation and upregulation of NF-κB-regulated genes (85, 86). To ascertain whether Tax expression in these cells has resulted in hyperactivation of NF-κB signaling, Illumina RNA-seq was employed to measure the RNA expression of NF-κB-dependent and -independent genes in untreated cells. A panel of NF-κB target genes was selected from a database of genes activated by NF-κB; these included immunoreceptor genes and genes involved in proliferation, apoptosis, stress response, and cytokine stimulation (87). A control panel of NF-κB-independent genes targeted by the IRF3 transcription factor was derived from the ENCODE Transcription Factors database (available on the Harmonizome search engine) for IRF3-target genes identified by chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq) (88, 89). IRF3-target genes also targeted by NF-κB, identified by their presence in the NF-κB-target gene panel (87), were not used in the IRF3-dependent target gene analysis. Overall, NF-κB-target gene transcripts were upregulated in all three HTLV-1-transformed lines relative to SupT1 (Fig. 4B to D, left). IRF3-target genes were not consistently up- or downregulated (Fig. 4B to D, right), consistent with a Tax-dependent chronic hyperactivation of NF-κB, but not IRF3, signaling in Tax-expressing cell lines. These data establish that Tax transactivation of the HIV-1 LTR is not solely responsible for MT-4 cell line permissivity to gp41 CT truncation.

Viral entry mediated by full-length and CT-truncated Env is equivalent among HTLV-transformed T-cell lines.

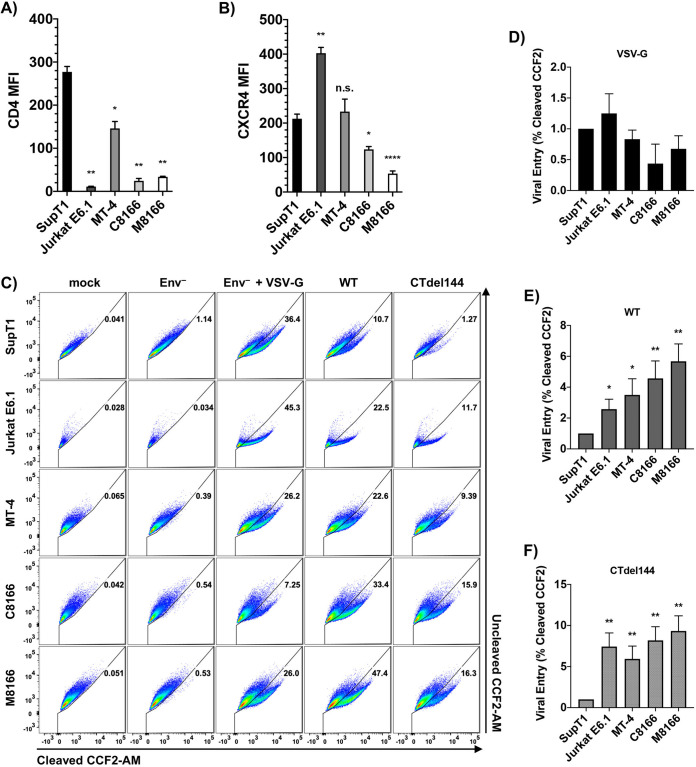

Binding of virion-associated Env to the CD4 receptor and CXCR4 or CCR5 coreceptor is an essential step for infection of human T cells by most strains of HIV-1. T-cell line tropic isolates, like NL4-3, use CXCR4 as their coreceptor. To determine whether high-level expression of CD4 or CXCR4 on the surface of MT-4 cells could contribute to the permissivity of this cell line to CT-truncated HIV-1, surface CD4 and CXCR4 were measured on the panel of T-cell lines (Fig. 5A and B). While MT-4 cells did express more CD4 and CXCR4 than C8166 or M8166, they expressed less CD4 than SupT1. Therefore, receptor and coreceptor expression levels do not account for the permissive phenotype exhibited by the MT-4 cell line.

FIG 5.

Viral entry mediated by full-length and CT-truncated Env is equivalent among HTLV-transformed T-cell lines. (A) Surface CD4 and (B) CXCR4 were measured by flow cytometry. MFI was determined by measuring the MFI value of CD4+ or CXCR4+ histograms and subtracting the isotype control MFI to directly compare MFIs between samples. To account for fluctuations in flow cytometry data that occur when comparing data from different experiments, cells from different acquisition dates were stained with antibody, fixed, and analyzed in parallel by flow cytometry. The bar graphs show the mean MFI values of cell surface (A) CD4 and (B) CXCR4, ± standard deviation (SD) from three independent experiments and the bar shading for ease of comparison between panels A and B. (C) BlaM-Vpr-based viral entry assays were performed using NL4-3 expressing either WT or CTdel144 Env. A mock treatment and Env– NL4-3 pseudotyped with VSV-G were used as a positive control, and Env– was used as a negative control. Representative FACS dot plots are shown. The virus dose used for each condition was titrated to avoid saturation (in the case of VSV-G and WT) and to be above the Env– conditions (in the case of CTdel144). Therefore, values can only be compared between cell lines for each condition, not between conditions. (D to F)The bar graphs show the fold change in viral entry relative to SupT1 (set at 1) between (D) VSV-G-pseudotyped Env– NL4-3, (E) WT NL4-3, and (F) CTdel144 NL4-3 with SD representing comparison of values derived from three independent experiments. Statistical significance was assessed by one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple-comparison test. P values are defined in Materials and Methods.

To determine whether increased efficiency of viral entry contributes to MT-4 cell line permissivity, the β-lactamase (BlaM)-based viral entry assay was performed using virus bearing either VSV-G, WT HIV-1 Env, or the CTdel144 Env truncation mutant (Fig. 5C to F). Differences in viral entry mediated by VSV-G were not statistically significant between the cell lines (Fig. 5D). Entry mediated by WT HIV-1 Env was significantly lower in SupT1 than in the other T-cell lines, with MT-4 cells intermediate between Jurkat E6.1 and the other HTLV-1-transformed T-cell lines. Entry mediated by WT Env was not statistically different between MT-4 and Jurkat E6.1, C8166, and M8166 cells (Fig. 5E). Entry mediated by CTdel144 was equivalent among all cell lines tested, with the exception of SupT1 cells, which displayed restricted entry consistent with low susceptibility to cell-free HIV-1 infection (18). These results demonstrate that the permissivity of MT-4 cells to the gp41 CT truncation mutant is not explained at the level of cell-free virus entry.

MT-4 cultures release more virus than other T-cell lines due to more rapid viral protein production.

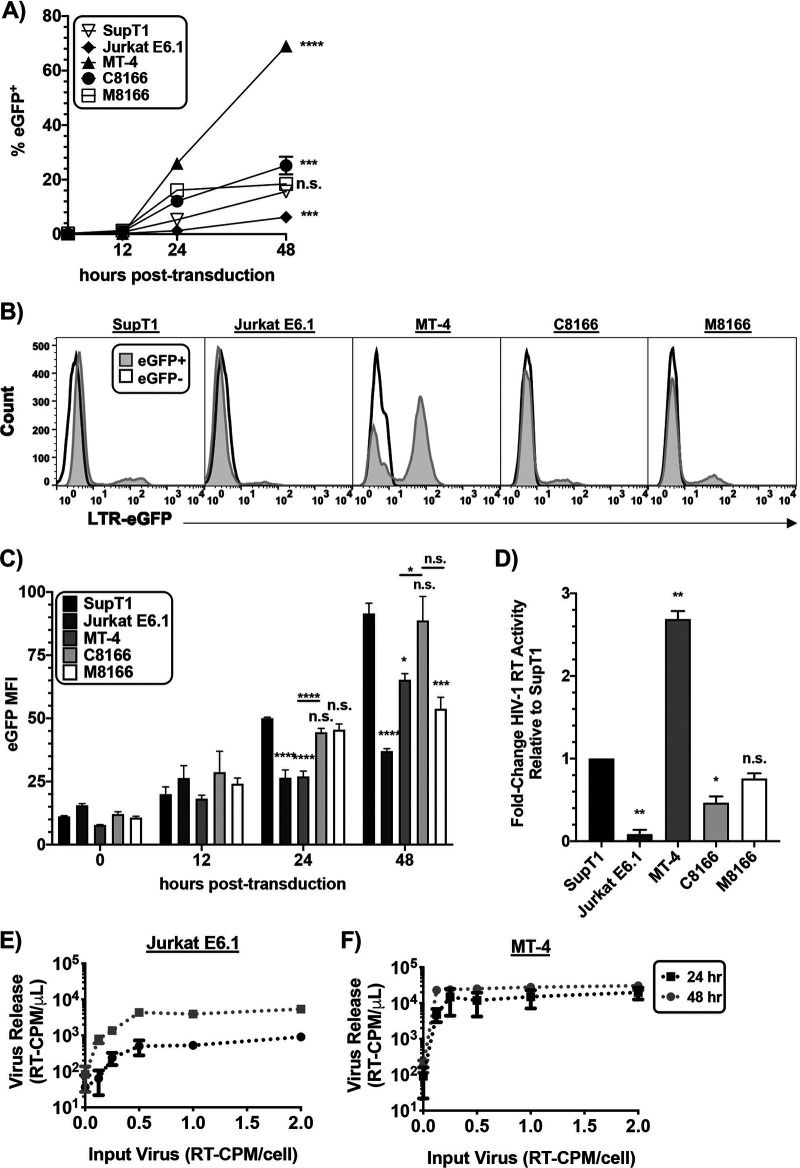

Because the kinetics of HIV-1 replication in MT-4 cells are more rapid than in the other T-cell lines tested, we hypothesized that the kinetics of HIV-1 gene expression might also be faster in MT-4 cells. An equal number of cells were transduced with equivalent amounts of VSV-G-pseudotyped Env– NL4-3 encoding enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) in place of Nef (Fig. 6A to C). In this reporter virus, eGFP expression is under transcriptional control of the viral LTR; eGFP thus serves as a surrogate for LTR-mediated gene expression. Cells were analyzed for eGFP expression by flow cytometry at multiple time points postransduction. We observed that a higher percentage of MT-4 cells expressed eGFP 24 hours postransduction relative to the other T-cell lines (Fig. 6A). The percentage of MT-4 cells expressing eGFP increased ∼3-fold 48 hours postransduction, whereas the other cell lines tested exhibited an ∼2-fold increase in the number of eGFP+ cells, with the exception of M8166, which exhibited only a minor increase in eGFP expression between 24 and 48 hours postransduction. Therefore, the kinetics of HIV-1 protein production in MT-4 cells are faster relative to the other T-cell lines examined here.

FIG 6.

MT-4 cultures release more virus than other T-cell lines due to more rapid viral protein production. Cells were transduced with VSV-G-pseudotyped pBR43IeGFP-nef–Env– reporter virus and collected at various time points. (A) The percentage of cells expressing eGFP at each time point was plotted. Error bars indicating the standard deviation of duplicate infections are too small to be seen. (B) Histogram of eGFP expression in the cell lines 48-hours postransduction indicating the percentage of cells expressing eGFP and their MFI relative to an eGFP– control. (C) eGFP levels at various time points postransduction (p.t.) were determined by the eGFP MFI from which the background MFI from the eGFP– construct was subtracted. The bar graph shows the mean eGFP MFI, ± SD, from three independent experiments. (D) Cell lines were transduced with VSV-G-pseudotyped NL4-3 Env– and washed, and supernatant HIV-1 RT activity was measured 42-hours postransduction. The bar graph shows the mean fold change relative to the SupT1 reference line, ± SD, from three independent experiments. (E and F) An equal number of Jurkat E6.1 and MT-4 cells were transduced with an increasing dose of VSV-G-pseudotyped pBR43IeGFP-nef–Env– reporter virus, and supernatant RT release was measured at 24 and 48 hours postransduction. (A to D) Statistical analysis was performed to compare cell lines relative to SupT1 at individual time points postransduction or between two samples as indicated by the horizontal line between two bars. n.s. indicates no statistical difference between the indicated cell line and the SupT1 reference or between two samples as indicated by the horizontal line between two bars. Statistical significance was assessed by one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple-comparison test.

To determine whether MT-4 cells express more HIV proteins than nonpermissive cells, the eGFP median fluorescence intensity (MFI) was measured at different time points (Fig. 6B and C). At 24 hours postransduction, the MFI of MT-4 was less than that of SupT1, C8166, or M8166 cells. At 48 hours postransduction, the MT-4 MFI increased to that of C8166 and M8166 cells, indicating that the HIV gene expression on a per-cell basis between MT-4 and C8166 is equivalent, consistent with the data of Emerson et al. (19). The finding that SupT1, a Tax– nonpermissive cell line, expressed more eGFP than MT-4 is inconsistent with the hypothesis that MT-4 cells are permissive to CT-truncation due to overall enhanced protein production per cell relative to nonpermissive cells.

To explore the role of viral protein production kinetics in virus output, virus release in the T-cell panel was measured. Cells were transduced with VSV-G-pseudotyped Env– NL4-3 encoding eGFP in place of Nef, and HIV-1 RT released into the supernatant was measured 42 hours postransduction (Fig. 6D). Consistent with increased kinetics of HIV-1 protein expression compared to the other T-cell lines in the panel, HIV-1 RT production was highest for MT-4 compared to other cell lines. To determine whether faster kinetics of viral protein production resulted in higher amounts of virus release from MT-4 cells compared to the nonpermissive Jurkat E6.1 cell line, an equal number of cells were transduced in parallel with increasing doses of VSV-G-pseudotyped Env– NL4-3 encoding eGFP in place of Nef, and HIV-1 RT released into the supernatant at 24 and 48 hours postransduction was measured (Fig. 6E and F). Jurkat E6.1 cells released 10-fold less virus at 24 hours than 48 hours postransduction (Fig. 6E). Virus release from MT-4 cells was indistinguishable between 24- and 48-hour time points at all but the lowest dose used (Fig. 6F). Furthermore, saturation of virus release from MT-4 cells occurred at 24 hours postransduction for all but the lowest input of virus. Taken together, these data indicate that on a per-cell basis, individual MT-4 cells do not exhibit higher steady-state cell-associated viral gene expression than the nonpermissive cell lines tested here. However, virus release reaches its peak in MT-4 cultures at earlier time points and these cells release approximately 3-fold more virus over a 42-hour period compared to nonpermissive cell cultures. Altogether, these data indicate that NL4-3 particle production in MT-4 cells is more efficient than in the other T-cell lines tested.

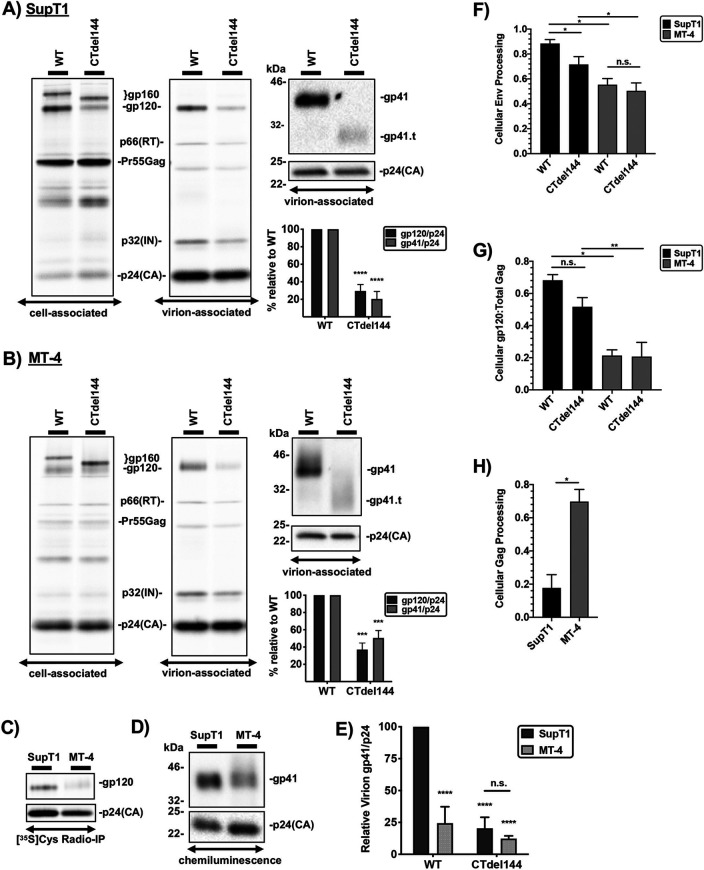

Virion Env incorporation in MT-4 cells is inefficient.

Because Env incorporation into virus particles is essential for viral infectivity, we next investigated the role of the gp41 CT in Env incorporation in SupT1 and MT-4. Env incorporation was determined by two methods, radio-immunoprecipitation (radio-IP) and Western blot analysis (Fig. 7A to C). Equivalent numbers of both MT-4 and SupT1 cells were transduced overnight with VSV-G-pseudotyped HIV-1 expressing either WT or CTdel144 Env and washed extensively the following morning to remove unabsorbed virus. Cell- and virus-containing supernatants were collected, lysed, and prepared for analysis as described in Materials and Methods. Consistent with our previous report (37), truncation of the gp41 CT in a nonpermissive T-cell line, SupT1, resulted in an approximately 10-fold decrease in Env incorporation, as measured by gp120 and gp41 levels in virions, compared to WT (Fig. 7A). In contrast, in MT-4 cells, truncation of the gp41 CT resulted in an approximately 2-fold reduction in Env incorporation (Fig. 7B). We next tested whether higher levels of WT Env are incorporated into virions produced in MT-4 compared to SupT1 cells. Virus lysates were similarly prepared as in Fig. 7A and B, RT-normalized, and subjected to SDS-PAGE, and Env band intensities were measured (Fig. 7C and D). Surprisingly, MT-4 cells were found to incorporate less WT Env than SupT1 cells.

FIG 7.

Virion Env incorporation in MT-4 cells is inefficient. SupT1 (A) and MT-4 (B) cells were transduced with RT-normalized VSV-G-pseudotyped NL4-3 encoding either WT or CTdel144 Env. Cells were metabolically labeled with [35S]Cys, and cell and virus lysates were immunoprecipitated to detect HIV proteins. The locations of p66(RT), the Gag precursor Pr55Gag, p32(IN), and p24(CA) are indicated. Western blotting was performed on the virus fraction to detect gp41 and p24(CA) using equal amounts of WT and CTdel144 viral lysates. gp41.t indicates the position of the truncated gp41, CTdel144. The fold change in Env incorporation between WT and CTdel144 Env, calculated by determining the ratio of virion-associated gp41 to p24(CA) relative to the WT condition, is indicated below the Western blots. (C and D) SupT1 and MT-4 were transduced as in panels A and B, and RT-normalized virus was used to compare gp41 content in the virus fraction. (C) Samples were analyzed by [35S]Cys radio-immunoprecipitation (IP) and (D) Western blots (detected by chemiluminescence). (E) Mean values of WT and CTdel144 gp41 incorporation into virions, with the WT gp41/p24 ratio in SupT1 set at 100. gp41 and p24 values were obtained from panels A and B. Error bars represent ± SD from three independent experiments. (F) Env processing efficiency was quantified by dividing cell-associated gp120 by the total cell-associated Env band intensity (gp120/[gp120+gp160]). (G) The cell-associated Env-to-Gag ratio was determined as (gp120/[Pr55Gag+p24]). (H) Gag processing was determined by dividing p24(CA) by total Gag band intensity. In panels E to G, the bar graphs show the mean values ± SD from three independent experiments. n.s. indicates no statistical difference between two samples as indicated by the horizontal line. Statistical significance was assessed by one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple-comparison test (E to G) or paired Student's t test (A, B, and H).

Having established that WT virus produced from MT-4 cells contains less WT Env than virus produced from SupT1 cells (Fig. 7C and D), we next calculated the Env content of CTdel144 virions produced in MT-4 cells relative to those produced in SupT1 cells. For this comparison, the average WT gp41 incorporation value for MT-4 relative to SupT1 cells determined in Fig. 7D was used to transform MT-4 CTdel144 gp41 virion incorporation values from Fig. 7B. This calculation indicated that CTdel144 Env incorporation in MT-4 and SupT1 cells is comparable (Fig. 7E). These results indicate that CTdel144 Env incorporation efficiency does not contribute to the permissivity of MT-4 cells to gp41 CT truncation.

To gain more insight into why MT-4 cells incorporate less Env than the nonpermissive SupT1 cell line, various parameters of viral assembly were determined (Fig. 7F to H). Env processing in MT-4 was lower than in SupT1 cells (Fig. 7F). The ratio of cell-associated gp120 to total Gag was also lower for MT-4 than SupT1 cells (Fig. 7G). Consistent with a previous report that examined other nonpermissive T-cell lines (19), we observed that Gag processing in MT-4 is more efficient than in the nonpermissive SupT1 cells (Fig. 7H). More efficient Gag processing is likely an indication of more rapid Gag trafficking, membrane association, and/or assembly, perhaps resulting in the completion of Gag lattice assembly before Env is recruited (35).

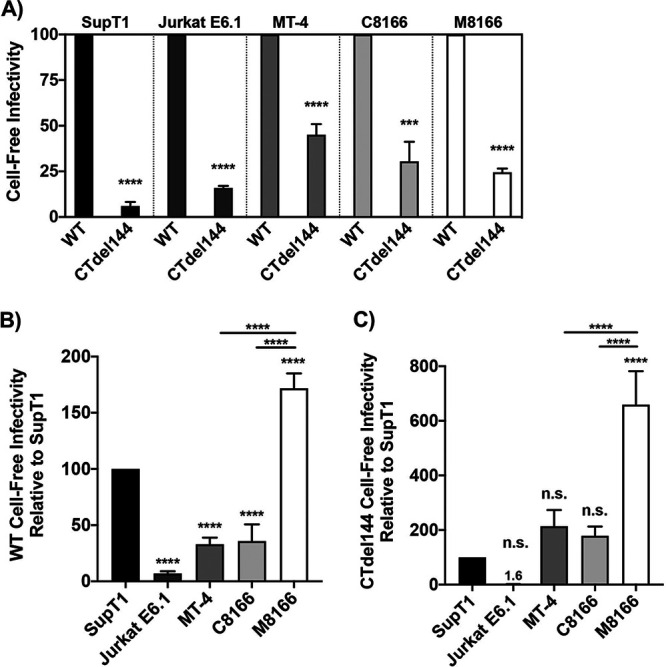

Infectivity of virions produced from MT-4 cells does not explain their permissivity to gp41 CT truncation.

The surprising result that Env incorporation in MT-4 is inefficient relative to SupT1 cells suggested that there is something inherently more efficient about viral transmission in the MT-4 cell line. To determine whether cell-free virions produced from MT-4 cells are more infectious than virions produced from the other cell lines in our panel, TZM-bl infectivity assays were performed (Fig. 8A to C). Cells were transduced with VSV-G-pseudotyped HIV-1 encoding either WT or CTdel144 Env and collected 42 hours postransduction. RT-normalized virus supernatants from the T-cell panel were used to infect TZM-bl cells in parallel. Consistent with our findings that Env incorporation of the CT-truncated Env is reduced ∼10-fold and ∼2-fold in SupT1 and MT-4 cells, respectively, cell-free infectivity was also reduced to a similar extent by the CTdel144 mutation (Fig. 8A). Thus, under these conditions and with these cell lines, cell-free infectivity closely correlates with levels of virion-associated Env.

FIG 8.

Infectivity of virions produced from MT-4 cells does not explain their permissivity to gp41 CT truncation. Cells were transduced with VSV-G-pseudotyped NL4-3 encoding either WT or CTdel144 Env. Viral supernatant was collected 42 hours postransduction. Supernatants were RT normalized, and a serial dilution of virus was used to infect TZM-bl cells. Luciferase values were then used to determine the relative infectivity of virus produced from each T-cell line. (A) The bar graph shows the mean values of CTdel144 relative to WT (set at 100) ± SD from three independent experiments. (B and C) The same virus was used as in panel A to compare WT and CTdel144 virus infectivity between cell lines. The bar graphs show the mean values of (B) WT and (C) CTdel144 relative to the SupT1 reference line (set at 100) ± SD from three independent experiments. Shading of individual columns indicates values for the individual cell lines for ease of comparison between data sets in panels A to C. Statistics relative to the SupT1 reference line, or between two samples as indicated by the horizontal line between two bars, are shown. n.s. indicates no statistical difference between the indicated cell line to the SupT1 reference. Statistical significance was assessed by (A) Student's t test and (B to C) one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple-comparison test.

To directly compare the infectivity between WT and CTdel144 virus produced from all five T-cell lines, TZM-bl cells were infected in parallel with the same RT-normalized virus produced as in Fig. 7A. SupT1 cells were used as the standard of comparison. We observed the infectivity of WT virus produced by all cells, with the exception of M8166, to be significantly lower than WT virus produced by SupT1 cells (Fig. 8B). Interestingly, CTdel144 virions produced in the nonpermissive cell line M8166 exhibited ∼3-fold higher levels of infectivity compared to MT-4 and C8166 cells (Fig. 8C), suggesting that cell-free infectivity is not a contributing factor to the CT-permissive phenotype of MT-4 cells.

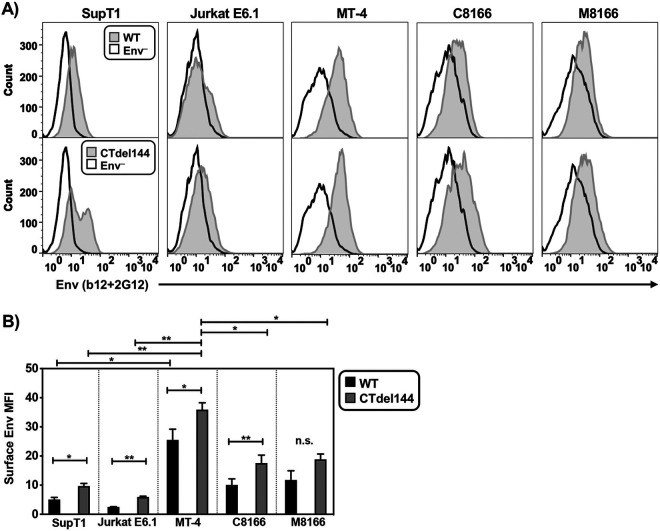

MT-4 cells express higher levels of cell-surface CT-truncated Env than other T-cell lines tested.

Because Env incorporation in MT-4 is reduced compared to that in the other T-cell lines tested, we next investigated whether Env is efficiently expressed on the cell surface of MT-4 cells. To measure cell surface-associated Env, the T-cell panel was transduced with VSV-G pseudotyped WT or CTdel144 NL4-3 and fixed 42 hours later, a time point at which the cells would be expected to express HIV-1 proteins but not display extensive syncytium formation. Fixed cells were then fluorescently labeled with anti-gp120 antibodies, and Env expression was measured by flow cytometry as a shift in the histogram relative to an Env– control (Fig. 9A). WT Env expression on MT-4 cells was higher than on the other cell lines tested (Fig. 9B). Consistent with the role of the gp41 CT in regulating endocytosis (26, 28, 90, 91), truncation of the gp41 CT enhanced cell-surface Env expression in all cell lines, including MT-4, although in M8166 cells the increase was not statistically significant (Fig. 9B).

FIG 9.

MT-4 cells express higher levels of surface CT-truncated Env than other T-cell lines tested as determined by flow cytometry. VSV-G-pseudotyped NL4-3 encoding either WT or Ctdel144 Env or no Env (Env–) was used to transduce T cells. Forty hours postransduction, cells were fixed and stained with anti-Env antibodies for analysis by flow cytometry. (A) A histogram of surface Env for each cell line is shown. Env– cells were used as a control for background staining. (B) Surface Env MFI was determined by measuring the MFI value of the Env+ histogram and subtracting the Env– MFI to directly compare MFIs between samples. To account for fluctuations in flow cytometry data that occur when comparing data from three independent experiments, cells were stained with antibody and analyzed in parallel by flow cytometry. The bar graph shows the mean values of WT and CTdel144 Env MFI ± SD from three independent experiments. n.s. indicates no statistical difference between WT and CTdel144 for the M8166 cell line. Error bars ± SD from 3 independent experiments. Statistical significance was assessed by Student's t test.

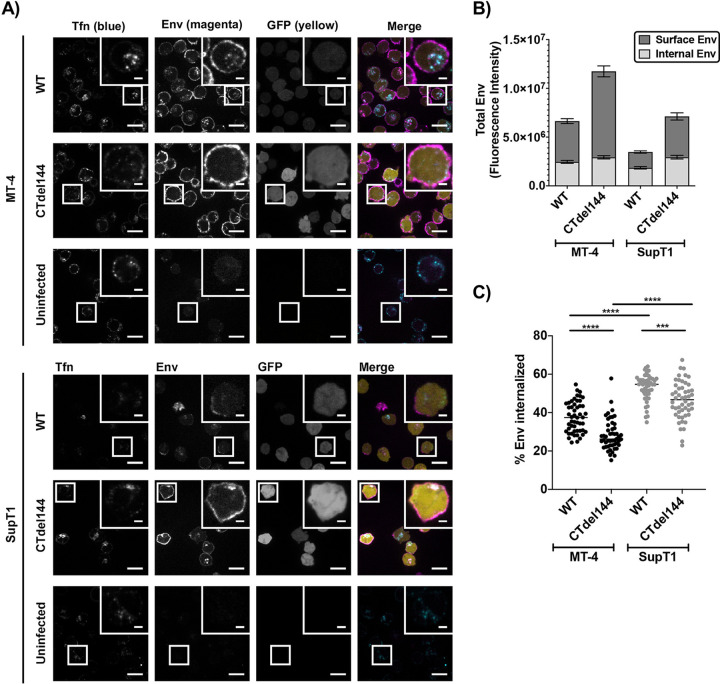

The enhanced surface expression of Env observed in MT-4 cells could be explained by either defects in Env internalization or high levels of viral protein production relative to the other cell lines, resulting in high levels of cell-associated Env. Having established that MT-4 cells do not exhibit higher levels of LTR-mediated gene expression than some other cell lines in the panel, we sought to determine whether Env internalization is defective in MT-4 cells. To confirm the higher levels of cell-associated Env on MT-4 relative to the nonpermissive SupT1 cell line, MT-4 and SupT1 cells were transduced with VSV-G-pseudotyped HIV-1, pulse-chased with a fluorescently labeled anti-gp120 monovalent Fab probe, and analyzed by confocal microscopy (Fig. 10A) (35). A monovalent Fab fragment was used to probe for Env levels to avoid bivalent antibody cross-linking of Env trimers, which has been shown to induce Env internalization (92). The anti-gp120 probe used in the pulse-chase assay labeled both the internalized pool of Env and surface Env. The total (nonbiosynthetic) Env was quantified by combining both the internalized pool and surface Env values. As a control to establish whether AP-2-dependent internalization machinery was functional, the cell media were supplemented during the short anti-gp120 pulse with fluorescent transferrin (Tfn) to label the endosomal compartments (93, 94) (Fig. 10A, uninfected conditions). Tfn was internalized in both SupT1 and MT-4 cells, confirming that both cell lines have an intact endocytosis machinery.

FIG 10.

MT-4 cells express higher levels of Env than SupT1, which is further enhanced by truncating the gp41 CT, as determined by confocal microscopy. MT-4 or SupT1 cells were infected with a replication-and-release-defective HIV-1 mutant (described in Materials and Methods) expressing an eGFP reporter (yellow) and either WT or CTdel144 Env. Approximately 40 hours postinfection, cells were simultaneously pulsed with anti-Env Fab b12-Atto565 (magenta) and transferrin-AF647 (blue) for 12 min and then chased for 50 min. Cells were fixed and imaged by confocal fluorescence microscopy. (A) Representative confocal slices of transduced MT-4 or Jurkat E6.1 cells after the pulse-chase labeling. Scale bars, 15 μm; inset scale bars, 3 μm. (B) Total surface Env and total internal Env per cell were measured using the integrated fluorescence intensity for regions defining the PM of the cell (surface) and a region defining the interior of the cell (internal), using a maximum intensity projection through a 4.5-μm confocal range centered in the approximate middle of a single cell. n = 50 infected cells per sample. The bar graph shows the mean values of surface and internal Env levels. (C) Percentage Env internalization was calculated as the percentage of internal Env above the total Env signal (internal and surface). The scatterplot shows the mean values of percentage internalized Env. n = 50 infected cells per sample. Error bars ± SEM. Statistical significance was assessed by one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple-comparison test.

To determine whether differences exist in Env internalization in SupT1 and MT-4 cells, the ratio of surface to internalized Env was analyzed (Fig. 10B and C). Consistent with the flow cytometric analysis (Fig. 9), MT-4 expressed higher levels of total and surface Env than SupT1 cells (Fig. 10B). Surface Env expression on MT-4 cells was further increased by truncating the gp41 CT. To gain further insight into the ability of MT-4 cells to internalize Env, we determined the percent Env internalization during the pulse-chase (Fig. 10C). More WT Env was internalized in SupT1 than in MT-4 cells during the pulse-chase. As expected, truncation of the gp41 CT resulted in less internalized Env for both MT-4 and SupT1 cells. Altogether, the data suggest that Env levels on the surface of MT-4 cells may be higher than on other lines due to reduced Env internalization.

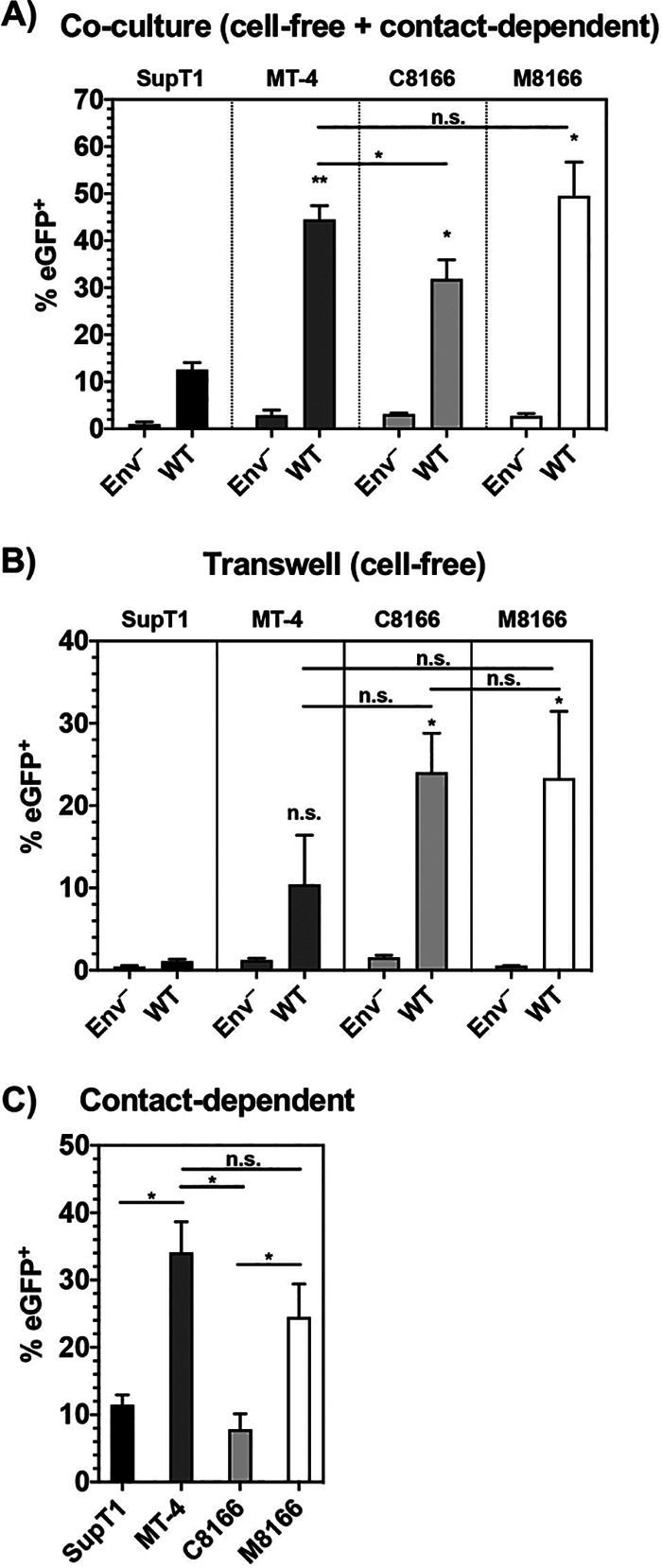

MT-4 cells serve as better targets for contact-dependent transmission than the other cell lines tested.

The results presented above suggest that levels of virion-associated Env and cell-free particle infectivity do not account for the permissivity of MT-4 cells to CT-truncated Env. We therefore explored the role of C-C transmission in the gp41 CT-truncation permissive phenotype. To gain a better understanding of MT-4 cells as a target for HIV-1 infection, we compared the relative ability of cell lines in the T-cell panel to be infected via contact-dependent transmission, using 293T cells as the donor. Nonlymphoid 293T cells do not express the adhesion molecules LFA-1, ICAM-1, or ICAM-3 (95). Using 293T cells as the virus-producing donor cell enabled the study of viral transmission independent of differences in LFA-1:ICAM1/3 engagement, surface Env levels, and kinetics of HIV release, as C-C transfer in this system is dependent primarily on Env-CD4 interactions. Because ∼50% of our Jurkat E6.1 cells do not express CD4 (Fig. 5A), this cell line was excluded from the analysis, as the CD4– cells would not become infected in the assay. The vector used in this analysis encodes eGFP under the control of the HIV-1 LTR; eGFP therefore labels cells infected by either the cell-free or contact-dependent route. 293T cells were transiently transfected with an HIV-1 proviral clone encoding eGFP and 24 hours later either cocultured with dye-labeled T cells or overlaid with a transwell containing dye-labeled T cells. Viral transfer in the coculture thus represents the summation of both cell-free and contact-dependent infection events (Fig. 11A). Evaluation of the transwell data showed that cell-free infection of MT-4 cells is less efficient than that of C8166 and M8166 but more efficient than that of SupT1 (Fig. 11B). Subtracting the transwell from the coculture values produced the contribution of contact-dependent infection (Fig. 11C). The results indicated that MT-4 cells were more efficiently infected by contact-dependent transmission than SupT1 or C8166. High MT-4 and M8166 susceptibility as target cells is not due to higher CD4 expression, since we found that SupT1 express higher levels of CD4 compared to either MT-4 or M8166 cells (Fig. 5A) and equivalent or greater levels of CXCR4 than MT-4 or M8166 cells, respectively (Fig. 5B). The differences in susceptibility to contact-dependent transmission from 293T donor cells to MT-4 and M8166 target cells were not statistically significant, suggesting that high susceptibility to C-C transmission likely contributes to, but does not entirely account for, the CT-truncation permissive phenotype of the MT-4 cell line.

FIG 11.

MT-4 cells serve as better targets for contact-dependent transmission than the other cell lines tested. 293T cells were transfected with pBR43IeGFP-nef– encoding either WT Env or Env–. Twenty-four hours posttransfection, dye-labeled T cells were either cocultured or added to a transwell exposed to the 293T supernatant. Eighteen hours postcoculture, BMS-806 was added to prevent multiple cycles of infection and the formation of syncytia. 48 hours post-initial coculture, cells were collected, fixed, and analyzed by flow cytometry. (A and B) The percentage of cells expressing eGFP was determined and plotted. (C) The transwell value was subtracted from the coculture value to determine the contribution of cell-to-cell transmission. The bar graphs show the mean values of the percentage of cells positive for eGFP expression for the panel A coculture, the panel B transwell (cell-free), and the C-C transmission in panel C ± SD from three independent experiments. Shading of individual columns indicates values for the cell line for ease of comparison between data sets. n.s. indicates no statistically significant difference between the indicated cell line and the SupT1 reference or between two samples as indicated by the horizontal line connecting two bars. Statistical significance was assessed by one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple-comparison test.

DISCUSSION

It has been previously reported in a number of studies that the CTdel144 gp41 truncation mutant is unable to establish a spreading infection in most T-cell lines or primary hPBMCs. In this study, we sought to elucidate the basis for the unusual, and in our analysis unique, permissivity of the MT-4 T-cell line to truncation of the gp41 CT. To this end, a panel of validated T-cell lines known or reported to be permissive or nonpermissive to gp41 CT truncation was compared to the MT-4 cell line. We confirmed that the MT-4 T-cell line is permissive to CT truncation but observed that other HTLV-transformed T-cell lines previously reported as permissive (19, 75, 96) are not. Differences in methodology or cell line origin likely explain the contrast in these findings. In part because of these differences, we extensively validated the T-cell lines used in the study. We found that HTLV-1 Tax expression, viral entry efficiency, cellular levels of viral protein expression, virion-associated Env content, and cell-free viral infectivity did not solely account for permissivity to gp41 CT truncation. A combination of rapid HIV-1 gene expression, enhanced cell-surface Env expression, and high susceptibility to C-C transmission compared to the nonpermissive lines tested in this study likely explains the ability of MT-4 cells to overcome the requirement for the gp41 CT. While our data indicate that Tax expression is not the primary causative factor in MT-4 cell line permissivity to CT truncation, they do not rule out the possibility that the presence or absence of one or multiple host factors could contribute to the permissive phenotype.

It was previously suggested that MT-4 cells express higher levels of Gag proteins after HIV-1 infection relative to the nonpermissive cells examined (19). We found that in MT-4 cultures, more cells were eGFP+ over time, and virus release peaked at 24 hours postransduction, indicating faster HIV-1 protein production kinetics compared to nonpermissive cells. HTLV-1 Tax expression and upregulated NF-κB activity were not associated with greater HIV-1 protein production; C8166 and M8166 cells expressed comparable levels of eGFP per cell relative to Tax– SupT1 and Jurkat E6.1 cells. These contrasting results are likely explained by methodological differences; our flow cytometry approach allowed us to quantify both eGFP expression per cell, and number of cells expressing eGFP, at various time points, while the Western blot approach used by Emerson et al. (19) measured total HIV-1 Gag expression in the cell cultures at a single time point. Both our study and that of Emerson et al. found that MT-4 cultures release approximately 3-fold more virus than nonpermissive cell cultures, and viral spread in MT-4 cultures occurs with faster kinetics than in nonpermissive cells. We conclude that this is due to faster kinetics of HIV-1 protein production and virus release in MT-4 cells rather than more protein being expressed per infected cell relative to nonpermissive cells.

A recent report found that MT-4 and C8166 cells are likely permissive to type I IN mutations due to HTLV-1 Tax expression inducing NF-κB protein recruitment to the HIV-1 LTR on unintegrated HIV-1 DNA (63). If this phenomenon were the cause of T-cell line permissivity to truncation of the gp41 CT, Tax+ C8166 and M8166 cells would also be permissive to gp41 CT truncation. Furthermore, we found that MT-4, C8166, and M8166 cells all display higher NF-κB activity than SupT1, indicating that they are all in a hyper-NF-κB activated state. Therefore, while Tax expression was found to overcome type I IN defects and activate transcription of nonintegrated HIV-1 DNA in C8166 and MT-4 cells (63), this phenomenon does not account for the unique ability of MT-4 cultures to host multiple rounds of CTdel144 infection.

Reduced Env incorporation in MT-4 was associated with a commensurate reduction in cell-free infectivity, suggesting that viral particles produced from MT-4 cells are not inherently more infectious than those produced from nonpermissive cells. We also observed that MT-4 cells exhibit a higher level of Gag processing relative to SupT1 and a lower level of Env processing. More efficient Gag processing may be a consequence of increased assembly kinetics. Previous work has led to the hypothesis that the timing of Gag assembly versus Env expression on the surface can influence the efficiency of Env incorporation; a delay in Env trafficking to the surface relative to completion of Gag assembly reduces the efficiency of Env trapping by the nascent Gag lattice (35), a phenomenon that could account for the relatively inefficient Env incorporation observed in MT-4 relative to SupT1 cells.

Consistent with the role of the gp41 CT in regulating Env internalization from the PM, truncation of the gp41 CT resulted in enhanced surface Env expression on all T-cell lines tested (with the exception of M8166, in which the increase was not statistically significant) as observed in previous studies (34, 97, 98). Analysis of Env internalization, using a pulse-chase assay, found that the amount of Env internalized was reduced in MT-4 compared to SupT1 cells. This reduced Env internalization may contribute to the reduced Env incorporation seen in MT-4 cells, consistent with a role for gp41 CT-dependent internalization from the PM in Env incorporation during viral assembly (33, 34, 99). This finding suggests a recycling-independent Env incorporation model in MT-4, wherein the presence of a full-length tail allows for some enhancement of WT Env incorporation by Gag lattice trapping during particle assembly (38), compared to the passive, less efficient incorporation of the gp41 CT-truncated mutant which is unable to be trapped. This is consistent with the observation that in HeLa cells the Env incorporation defect observed with CTdel144 could be overcome by increasing Env expression while maintaining equivalent Gag levels, essentially increasing the Env:Gag ratio (99); more Env on the surface leads to an increase in nonspecific (passive) incorporation that is less dependent on the gp41 CT and its trapping by the Gag lattice (5). The lower Env:Gag ratio observed in MT-4 compared to SupT1 cells may contribute to the equivalent levels of CTdel144 Env incorporation in these cell lines. It is possible that by increasing the Env:Gag ratio in MT-4 cells, Env incorporation could be increased.

C-C transfer assays using MT-4 donor and MT-4 target cells were performed in a previous study from another research group (19). This study found that C-C transmission in MT-4 cultures is more efficient than in H9, a T-cell line that is nonpermissive for CT truncation. The approach of using 293T as virus-donor cells (18) allowed us to test the susceptibility of the T-cell line panel to contact-dependent transmission independent of the ability of the T-cell lines to serve as donor cells. We observed an approximately 3-fold higher susceptibility of MT-4 and M8166 cells to contact-dependent transmission from 293T donor cells compared to SupT1 and C8166 cells. Because the susceptibility of M8166 cells to infection by a contact-dependent route is not significantly different from that of MT-4 cells, we conclude that susceptibility to contact-dependent infection is likely one of several factors that together contribute to the CT-truncation-permissive phenotype of MT-4 cells. These data also indicate that a differential susceptibility to C-C transmission between C8166 and M8166 cells (a subclone of C8166 cells more susceptible to formation of syncytia and capable of hosting SIV replication) arose during the generation of the M8166 cell line. Because the lipid composition of the target cell membrane has been shown to affect viral fusion and entry (100, 101), it is possible that differences in PM lipid composition between the cell lines studied here account for the high susceptibility of MT-4 and M8166 cells to contact-dependent transmission. Further studies will be required to evaluate this possibility.

The higher surface expression of Env in MT-4 cells relative to nonpermissive T-cell lines may contribute to the formation of more stable and longer-lasting VSs in MT-4 cultures compared to nonpermissive cell cultures. The faster kinetics of virus release from MT-4 donor cells and the higher susceptibility of MT-4 target cells to contact-dependent viral transmission may contribute to the CT-truncation-permissive phenotype by promoting higher levels of productive virus transfer across the VS during the span of the C-C contact time in MT-4 cultures compared to nonpermissive cultures.

The permissivity of the MT-4 cell line to replication of gp41 CT-truncated virus has been of long-standing interest in the field. This study reveals that multiple factors are associated with this phenotype. The results presented here highlight that Env incorporation, viral transfer, and ultimately, the establishment of a spreading infection are influenced by a number of factors, including the kinetics of viral protein expression and virus release, the levels of Env expressed on the cell surface, and the efficiency of Env trafficking and internalization.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines and culture.

The 293T (obtained from American Type Culture Collection [ATCC]) and TZM-bl (obtained from J. C. Kappes, X. Wu, and Tranzyme, Inc., through the NIH AIDS Reagent Program [ARP], Germantown, MD) cell lines were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) containing 5% or 10% (vol/vol) fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2 mM glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Gibco) at 37°C with 5% CO2. Jurkat E6.1, MT-4, C8166-45 (referred to as C8166; cell line accession ID on the Cellosaurus database is CVCL_0195), and M8166 were obtained from Arthur Weiss (catalog no. 177), Douglas Richman (catalog no. 120), Robert Gallo (catalog no. 404), and Paul Clapham (catalog no. 11395), respectively, through the NIH ARP. The source of the SupT1 used in this study is unknown. The SupT1-CCR5 (102) T-cell line was a generous gift from James Hoxie (102) (STR profile submitted to Cellosaurus at the time of submission under accession ID CVCL_X633). The ATL Tax– cells lines (ED, ATL-35T, and TL-Om1) were a generous gift from Chou-Zen Giam. T-cell lines were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% FBS, 2 mM glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Gibco) at 37°C with 5% CO2. Whole blood was obtained from healthy donors via the NIH Clinical Center. hPBMCs were isolated using a ficoll gradient and stimulated with 2 μg/ml PHA-P for 3 to 5 days before infection and then cultured in 50 U/ml interleukin-2 (IL-2).

Cloning and plasmids.

The HIV-1 pNL43-nef–-eGFP reporter vector (also called pBR43IeGFP-nef–; catalog no. 11351) was obtained through the NIH ARP from Frank Kirchhoff. The Env– construct was generated by restriction digest of the pNL4-3/KFS clone (103), referred to here as pNL4-3 Env–, and target vector with StuI and XhoI restriction enzymes followed by ligation of the Env fragment into pBR43IeGFP-nef– to generate pBR43IeGFP-nef–Env–. Unless otherwise indicated, the full-length HIV-1 clade B molecular clone pNL4-3 was used (104). The Env– (103) and the CTdel144 clone (43) were described previously. Wild-type and CTdel SIVmac239 were generated by Bruce Crise and Yuan Li and were a generous gift from Jeff Lifson. Plasmid sequences were confirmed by restriction digest with HindIII and Sanger sequencing. The HIV-1 YU2 Vpr β-lactamase expression vector (pMM310) was obtained from Michael Miller (catalog no.11444) through the NIH ARP. The plasmids pHR′CMV-GFP and pHR′CMV-Tax were a generous gift from Chou-Zen Giam.

For confocal microscopy, nonpropagating, release-defective constructs were generated (pSVNL4-3-ctfl-dPol-dVV-GFP-3′LTR and pSVNL4-3-ctfl-dPol-dVV-dCT-GFP-3′LTR, where ctfl = C-terminal FLAG tag on Gag, dPol = deletion of Pol, dVV = deletion of Vif and Vpr, by removal of the Aflll fragment, and GFP = green fluorescent protein in place of Nef). Expression plasmids for Env and associated mutants in addition to Gag were natively expressed from the reference HIV-1 clone NL4-3 with the following modifications: the pNL4-3 vector was subcloned into an SV40 ori-containing backbone (pN1 vector; Clontech; pSVNL4-3), deletion of pol by removal of the BclI-NsiI fragment, mutation of the p6 PTAP motif (455PTAP458-LIRL) (105), addition of a coding C-terminal FLAG tag to the Gag open reading frame to detect Gag expression (GSDPSSQ500-SGDYKDDDDK) (106), and removal of the 5′ portion of the nef open reading frame and replacement with a GFP coding sequence.

Preparation of virus stocks.

The 293T cells were transfected with HIV-1 proviral DNA using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Virus-containing supernatants were filtered through a 0.45-μm membrane 48 hours posttransfection, and virus was quantified by measuring RT activity. VSV-G-pseudotyped virus stocks were generated from 293T cells cotransfected with proviral DNA and the VSV-G expression vector pHCMV-G (107) at a DNA ratio of 10:1.

For confocal microcopy, virus particles were made using the pSVNL4-3 plasmids. Briefly, VSV-G-pseudotyped, single-round viruses were produced by transfecting 293T cells with the pSVNL4-3 plasmids, the psPAX2 packaging plasmid (a gift from Didier Trono, Addgene plasmid no. 12260), and pVSV-G expression plasmid using polyethyleneimine (PEI) transfection reagent (Alfa Aesar/Thermo Fisher Scientific). The virus was harvested at ∼48 hours after transfection and stored at –80°C.

STR profiling and cell line validation.

The identity of cells in the T-cell line panel was confirmed by performing STR profiling as described previously (60). Briefly, genomic DNA was extracted and sent to Genetica (LabCorp) for profiling. The URL for this data set is https://amp.pharm.mssm.edu/Harmonizome/gene_set/IRF3/ENCODE+Transcription+Factor+Targets. The obtained STR profile was compared to the Cellosaurus reference STR (108) using the percentage match formula (109).

Illumina RNA-Seq.

RNA was extracted from T cells in their exponential growth phase using QIAshredder (Qiagen; catalog no. 79654) and RNeasy Plus minikit (Qiagen; catalog no. 74134). RNA sample integrity was assessed by determining the RNA integrity number (RIN) with an Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer instrument and applying the Eukaryote Total RNA Nano assay. RIN values were between 9 and 10, indicating intact RNA. Samples were sequenced on a HiSeq 2500 instrument, generating an average of 50 million raw reads per sample. Transcript sequence reads were normalized against the total reads for each cell line to generate a reads per kilobase per million mapped reads (RPKM) value. The RPKM is a relative measure of transcript abundance.

A panel of NF-κB-dependent genes was obtained by random selection of genes from a database of NF-κB target genes (87). An IRF3-dependent gene panel was obtained from the Harmonizome search engine (88) by searching the ENCODE Transcription Factors gene set titled “IRF3” (89). This gene set contains 4,159 IRF3 transcription factor target genes obtained from DNA-binding by ChIP-seq data sets. Genes dually targeted by NF-κB and IRF3 were removed from the IRF3-dependent gene panel used in our analysis.

To analyze expression of NF-κB and IRF3 target genes, the average RPKM for each parent gene transcript was mined from the total acquired RNA-seq data set. RPKM values of zero were set to 1 to allow for fold change analysis. HTLV-transformed cell lines were compared to the lymphoma-derived SupT1 line to generate the fold change value. This value was then converted by log2 transformation.

Virus replication assays.

Virus replication kinetics were determined in Jurkat E6.1 and MT-4 cell lines as previously described (26). Briefly, T cells were transfected with proviral clones (1 μg DNA/106 cells) in the presence of 700 μg/ml DEAE-dextran. MT-4, C8166, and M8166 cells were split 1:2 every 2 days, and SupT1 and Jurkat E6.1 were split 1:3 every 2 to 3 days with fresh medium. VSV-G-pseudotyped virus was used to inoculate stimulated hPBMCs. Virus stocks were normalized by 32P RT activity and used to initiate spreading infection. After a 2-hour incubation with VSV-G-pseudotyped virus, cells were washed and resuspended in fresh RPMI-10% FBS. Every other day, half the medium was replaced without disturbing the cells. Virus replication was monitored by measuring the RT activity in collected supernatants over time. RT activity values were plotted using GraphPad Prism to generate replication curves.

HIV-1 infection of T cells.

The 293T cells were plated and cotransfected via lipofectamine the next day with the pNL4-3 proviral clone and the VSV-G expression vector, pHCMV-VSV-G, at a 10:1 ratio. Then, 48 hours posttransfection, supernatants were passed through a 0.45-μm filter, and RT activity was measured by 32P RT activity assay as described previously (110). T cells were plated the night before infection in fresh medium at a density of 5 × 106 cells/2 ml. The following day, cells were infected overnight with RT-normalized virus.

Western blotting for viral proteins.

The morning after transduction, cells were washed extensively to remove any unabsorbed virus and plated in 1.5 ml of RPMI-10; 42 hours postinfection, cells were pelleted and lysed. Virus-containing supernatants were passed through a 0.45-μm filter; 10 μl were set aside for RT assay, and 200 μl were set aside for TZM-bl infectivity assay. The remaining filtered virus-containing supernatant was layered on a 20% wt/vol sucrose/phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) solution and spun for 1.25 hours at 100,000 × g at 4°C in a Sorvall S55-A2 fixed angle rotor (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Cell and virus fractions were lysed in lysis buffer (30 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 0.5% Triton X-100, 10 mM iodoacetamide, complete protease inhibitor [Roche]). Lysates boiled with 6× loading buffer (7 ml 0.5 M Tris-HCl/0.4% SDS, 3.8 g glycerol, 1 g SDS, 0.93 g DTT, 1.2 mg bromophenol blue) were subjected to SDS-PAGE on 12% 1.5-mm gels and processed using standard Western blotting techniques. All antibodies were diluted in 10 ml of 5% milk in TBS blocking buffer. HIV proteins were detected with 10 μg/ml polyclonal HIV immunoglobulin (HIV-Ig) obtained from the NIH ARP. Anti-human IgG conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (HRP) was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (catalog no. GENA933) and used at a 1:5,000 dilution. gp41 was detected with 2 μg/ml 10E8 monoclonal antibody obtained from the NIH ARP (catalog no. 12294) followed by anti-human IgG-HRP as described above.

To detect HTLV-1 Tax protein, 2 × 106 cells were lysed in 100 μl of lysis buffer and 30 μl of 6× loading buffer and boiled for 10 min. Then, 20 μl of cell lysates was loaded on a 12% 1.5-mm Tris-glycine gel and processed using standard Western blotting techniques. HTLV-1 Tax was detected with an anti-Tax-1 mouse monoclonal antibody (Abcam; catalog no. ab26997) at a 2-μg/ml concentration followed by goat-anti-mouse-HRP antibody (Thermo Fisher; catalog no. 32230) at a 0.5-μg/ml concentration. β-actin was used as a loading control and detected using anti-β-actin conjugated directly to HRP (Abcam; catalog no. ab49900). Protein bands were visualized using chemiluminescence with a Bio-Rad Universal Hood II ChemiDoc or the Azure Biosystems Sapphire Biomolecular Imager and then analyzed with ImageLab v5.1 software or the Azure Spot Analysis software, respectively.

Metabolic labeling and radioimmunoprecipitation were performed as previously described (37). Phosphor screens were imaged with a Bio-Rad Personal Molecular Imager system, and quantitative analysis of bands was performed with the Azure Spot Analysis software.

Viral entry assay.

BlaM-Vpr-containing viruses were produced by transient cotransfection of 239T cells with pNL4-3 constructs encoding either Env–, WT, or CTdel144 sequences, a second plasmid (pMM310; NIH ARP; catalog no. 11444) encoding the BlaM-Vpr fusion protein, and a third plasmid (pAdvantage; Promega; catalog no. E1711) to enhance transient protein expression at a 6:2:1 ratio. For the VSV-G control, pHCMV-VSV-G was provided in trans at a 10:1 ratio relative to pNL4-3. Virus-containing supernatant was filtered 48 hours posttransfection and concentrated using Lenti-X concentrator (TakaRa Bio; catalog no. 631231) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After concentration, the virus particles were resuspended in CO2-independent medium (Thermo Fisher; catalog no. 18045088), aliquoted, and stored at –80°C. Resuspended virus was diluted 10,000×, and virus concentration was measured using two methods: (i) p24gag concentration by Lenti-X GoStix Plus (TakaRa Bio; catalog no. 631280) and (ii) 32P RT activity (110).

Entry of BlaM-Vpr-containing virus was detected using a fluorescent substrate, CCF2-AM (Thermo Fisher; catalog no. K1032) (111). To perform the BlaM-Vpr assay, a suspension of 20 × 106 cells/ml was made; 100 μl of this suspension was aliquoted per well of a U-bottom plate. Cells were infected for 4 h at 37°C with 400 ng p24gag. After incubation with virus, cells were washed 2 times with CO2-independent medium supplemented with 10% FBS. Cells were then resuspended in 100 μl CO2-independent medium with 10% FBS and 20 μl of the CCF2-AM reagent (prepared according to the manufacturer’s instructions). Cells were incubated for 1 hour with the CCF2-AM reagent in darkness at room temperature. Cells were then washed 2 times with PBS, resuspended in CO2-indpendent medium plus 10% FBS, and left at room temperature in darkness overnight. Sixteen hours later, cells were fixed in 100 μl 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) and analyzed the same day. Flow cytometric analysis utilized a Fortessa X-20 flow cytometer (BD Bioscience) and FlowJo software (Tree Star, Inc., Ashland, OR, USA).

Single-cycle infectivity assays.

TZM-bl infectivity assays were performed as previously described (112). Briefly, 20,000 TZM-bl cells were plated in a flat-bottomed white-walled plate (Sigma-Aldrich; catalog no. CLS3903-100EA). The following day, the cells were infected with serial dilutions of RT-normalized virus stocks in the presence of 10 μg/ml DEAE-dextran. Approximately 36 hours postinfection, cells were lysed with BriteLite luciferase reagent (Perkin-Elmer), and luciferase was measured in a Wallac BetaMax plate reader.

Flow cytometry.

Cells were resuspended in 8% bovine serum albumin (BSA)/PBS at a concentration of 107 cells/ml. Then, 100 μl was aliquoted into a 96-well V-bottom plate (Sigma-Aldrich; catalog no. CLS3897). An antibody solution was made using 20 μl of either isotype or target antibody per test, as recommended by the manufacturer. The following antibodies from BD Pharmigen were used: APC mouse IgG2a κ isotype control (catalog no. 555576), APC mouse anti-CD184 (CXCR4) (catalog no. 560936), PE mouse anti-CD4 (catalog no. 555347). The isotype control for CD4 was acquired from BioLegend (PE mouse IgG1, κ isotype control; catalog no. 400113). Cells were incubated with antibodies for 20 min at room temperature and then washed 3 times with PBS. Samples were analyzed via the BD FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Bioscience) and FlowJo software (Tree Star, Inc.).