Abstract

Parsonage-Turner Syndrome (PTS), also known as idiopathic brachial plexopathy or neuralgic amyotrophy, is an uncommon condition characterized by acute onset of shoulder pain, most commonly unilateral, which may progress to neurologic deficits such as weakness and paresthesias (Feinberg and Radecki, 2010 [1]). Although the etiology and pathophysiology of PTS remains unclear, the syndrome has been reported in the postoperative, postinfectious, and post-vaccination settings, with recent viral illness reported as the most common associated risk factor (Beghi et al., 1985 [2]). Various viral, bacterial, and fungal infections have been reported to precede PTS, however, currently there are no reported cases of PTS in the setting of recent infection with SARS-CoV2 (COVID-19). We present a case of a 17 year old female patient with no significant past medical or surgical history who presented with several weeks of severe joint pain in the setting of a recent viral illness (SARS-CoV2, COVID-19). MRI of the left shoulder showed uniform increased T2 signal of the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, teres major, and trapezius muscles, consistent with PTS. Bone marrow biopsy results excluded malignancy and hypereosinophilic syndrome as other possible etiologies. Additional rheumatologic work-up was also negative, suggesting the etiology of PTS in this patient to be related to recent infection with SARS-CoV2 (COVID-19). Radiologists should be aware of this possible etiology of shoulder pain as the number of cases of SARS-CoV2 (COVID-19) continues to rise worldwide.

Keywords: Parsonage-turner syndrome, Acute idiopathic brachial neuritis, Neuralgic amyotrophy, Shoulder-girdle syndrome, Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C), SARS-CoV2

1. Introduction

Parsonage-Turner Syndrome (PTS), also known as idiopathic brachial plexopathy or neuralgic amyotrophy, is an uncommon condition with a reported overall incidence of 1.64 cases in 100,000 people [1]. It most commonly affects young adults, although cases have been reported from 3 months of age to 75 years [1]. It is characterized by acute onset of severe shoulder pain, most commonly unilateral, which may extend to the arm and hand [1]. The pain is often constant and is not positional in nature. It is usually self-limiting and may last for 1–2 weeks, although less frequently, persistent pain has been reported [1]. PTS is also characterized by associated delayed upper extremity weakness, muscle atrophy, and painless paresthesias, which tend to slowly and gradually resolve [3]. Although most patients report 80–90% recovery of muscle strength at 2–3 years, greater than 70% of patients experience residual paresis and exercise intolerance [4].

The diagnosis of PTS is primarily made through clinical history/symptoms and physical exam findings. Additional diagnostic work-up, including imaging and electromyography may support the diagnosis of PTS often by excluding other etiologies [5]. The differential diagnosis for PTS includes primary glenohumeral joint pathology, however PTS can be distinguished from primary joint pathology through appropriate clinical history, physical exam, and imaging findings. Treatment of PTS predominantly focuses on pain management with opiates, NSAIDs, and neuroleptics [1]. Additionally, there is some evidence to suggest that the use of early oral corticosteroid therapy may be beneficial [5].

Although the etiology and pathophysiology of PTS remains unclear, the syndrome has been reported in the postoperative, postinfectious, and post-vaccination settings [1,2]. There is a possible underlying genetic component, as variants of PTS are hereditary [6]. PTS has also been associated with various autoimmune disorders such as systemic lupus erythematous, temporal arteritis, and polyarteritis nodosa [1]. However, recent viral illness and recent immunization are the most common associated risk factors, with cases reported in 25% and 15% of patients who developed PTS, respectively [6]. Given this relatively strong correlation, it is thought that PTS may result from a viral illness directly involving the brachial plexus or from an autoimmune response to a viral infection or antigen [1]. Various viral, bacterial, and fungal infections have been reported to precede PTS, including herpes simplex virus, Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, varicella zoster virus, Parvo virus B19, Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), Hepatitis B virus, Hepatitis E virus, Vaccina virus, Coxsackie B virus, and west nile virus [7]. However, currently there are no reported cases of PTS in the setting of recent infection with SARS-CoV2 (COVID-19). We present a case of a patient found to have PTS shortly after proven infection with SARS-CoV2 (COVID-19).

2. Case report

A 17 year old female patient with no significant past medical or surgical history presented with several weeks of shortness of breath and joint pain. She reports her symptoms initially began 3 months prior to presentation, when she experienced fevers, chills, and other upper respiratory infection symptoms for about 1 week, which resolved without intervention. A few weeks later the patient reported new onset of multifocal joint pain, most prominent in the left shoulder and left hand. The pain was described as constant, but exacerbated by any movement. She initially presented to her primary care physician and was given a short dose of oral steroids, during which her symptoms greatly improved. However, shortly after this, the patient began to experience worsening abdominal pain, shortness of breath, palpitations, and joint pain, which prompted her to visit the emergency department.

On physical exam, she appeared pale, was able to speak in full sentences on room air, but appeared short of breath. She had full range of motion of the left shoulder and left hand, but was somewhat limited by pain. Her exam was otherwise within normal limits. Her serum inflammatory markers were markedly elevated, including c-reactive protein (CRP) of 92.6 mg/L (reference range ≤3.0 mg/L), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 98 mm/h (reference range 0–30 mm/h), d-dimer of 3479.5 ng/mL (reference range 30–230 ng/mL), and ferritin of 1216.1 ng/mL (reference range 8.0–252.0 ng/mL). She was anemic, with a hemoglobin of 6.8 g/dL (reference range 11.5–16.0 g/dL) and had mild leukocytosis, white blood cell count of 12.3 K/uL (reference range 4.0–10.3 K/uL), with eosinophilia of 15% (reference range 1–5%) on manual differentiation. The HIV and respiratory pathogen PCR panel were negative. The SARS-CoV2 real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction test (RT-PCR) from nasopharyngeal swab was negative, however serum IgG antibodies for SARS-CoV2 were positive, suggesting prior infection/exposure.

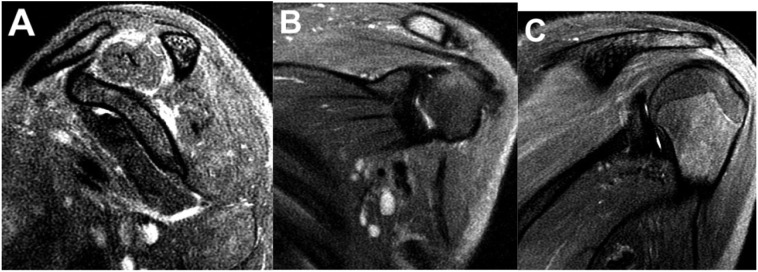

Imaging workup included CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis which revealed cardiomegaly, mediastinal and left supraclavicular adenopathy, hepatomegaly, and ascites, possibly related to systemic infection/inflammation or malignant etiology. An echocardiogram revealed dilation of the left coronary artery. MR of the left shoulder demonstrated uniform increased T2 signal of the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, teres major, and trapezius muscles, consistent with PTS (Fig. 1a, b, c).

Fig. 1.

Sagittal (A) and coronal (B, C) views of a fat-saturated T2-weighted sequence of the left shoulder demonstrates diffusely increased signal of the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, teres major, and trapezius muscles.

Diagnostic work-up for underlying malignancy or rheumatologic disorder was negative. Bone marrow biopsy and aspirate results also excluded hematologic malignancy and hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES) as alternative etiologies for the patient's symptoms.

Given the temporal relation of her symptom onset, markedly increased inflammatory markers, dilation of left coronary artery, and confirmed infection/exposure to SARS-CoV2, a post COVID-19 hyperinflammatory syndrome such as multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) was the favored diagnosis over other etiologies such as a developing autoimmune disorder.

3. Discussion

Although history and physical exam are integral in the diagnosis of PTS, further evaluation with imaging is often helpful as a means of ruling out other etiologies for a patient's symptoms in addition to confirming a suspected diagnosis of PTS. MRI is the imaging modality of choice to evaluate for PTS.

Imaging findings in PTS on MRI are thought to reflect the sequela of denervation of skeletal muscle in the distribution of the brachial plexus [8]. In the acute phase, denervated muscle may appear normal, however the earliest detectable abnormality is diffusely increased T2-weighted signal due to intramuscular edema, which may not be present until after 2 weeks [8,9]. Corresponding T1-signal abnormality may not be present. The supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles have been reported to be most commonly involved [8].

If the disease progresses to subacute or chronic denervation, findings compatible with subsequent muscle atrophy, such as decreased muscle volume and increased T1-weighted signal due to fatty infiltration may be seen [8]. As clinical symptoms resolve, intramuscular signal abnormalities on MR will not persist [8].

MRI can also exclude other sources of shoulder pain, such as rotator cuff tear, impingement syndrome, and labral tear [8].

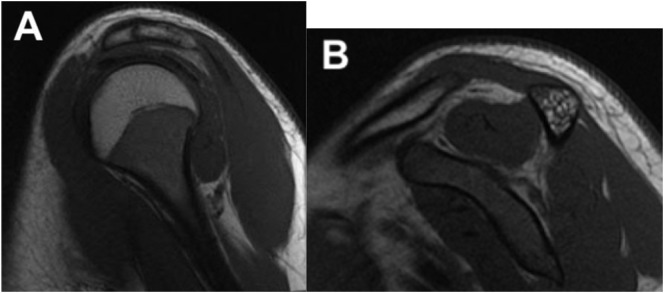

In our case, MRI of the left shoulder demonstrated uniform increased T2 signal of the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, teres major, and trapezius muscles (Fig. 1a, b, c). There was no corresponding T1-weighted signal abnormality (Fig. 2a, b). There was no evidence of muscle atrophy or underlying injury to the rotator cuff tendons or labrum. There was no fracture or abnormality in bone marrow signal. The glenohumeral and acromioclavicular joints appeared normal. There was no evidence of bursitis. These imaging findings are consistent with the diagnosis of PTS.

Fig. 2.

Sagittal (A) and coronal (B) views of a fat-saturated T1-weighted sequence of the left shoulder demonstrates no abnormal T1 signal, normal muscle volume, and lack of muscle atrophy or fatty infiltration.

Upon initial presentation, there were many possible etiologies of shoulder pain in this patient. After underlying malignancy, rheumatologic disorder, and hypereosinophilic syndrome were ruled out, sequelae of a post COVID-19 hyperinflammatory syndrome such as multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) likely explains this patient's symptoms, serum and pathologic analyses, and imaging findings. This is further supported by the initial improvement in symptoms after administration of oral corticosteroids. While a post-viral hyperinflammatory syndrome is a well-known cause of PTS, it has not been reported in a case of recent infection with SARS-CoV2 (COVID-19), as demonstrated in our patient. The number of cases of SARS-CoV2 (COVID-19) continues to rise worldwide and this post-infectious syndrome is an increasingly significant possible etiology of pain in a patient with suspected PTS.

Footnotes

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. The authors have no competing interests to disclose.

References

- 1.Feinberg J.H., Radecki J. Parsonage turner syndrome. HSS J. 2010;6(2):199–205. doi: 10.1007/s11420-010-9176-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beghi E., Kurland L.T., Mulder D.W., Nicolosi A. Brachial plexus neuropathy in the population of Rochester, Minnesota, 1970–1981. Ann Neurol. 1985;18(3):320–323. doi: 10.1002/ana.410180308. September. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gonzalez-Alegre P., Recober A., Kelkar P. Idiopathic brachial neuritis. Iowa Orthop J. 2002;22:81–85. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Alfen N. Clinical and pathophysiological concepts of neuralgic amyotrophy. Nat Rev Neurol. 2011;7:315–322. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2011.62. https://doi-org.ezproxy.med.cornell.edu/10.1038/nrneurol.2011.62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fransz D.P., Schönhuth C.P., Postma T.J. Parsonage-turner syndrome following post-exposure prophylaxis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2014;15:265. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-15-265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fibuch E.E., Mertz J., Geller B. Postoperative onset of idiopathic brachial neuritis. Anesthesiology. 1996;84(2):455–458. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199602000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stek C.J., van Eijk J.J.J., Jacobs B.C. Neuralgic amyotrophy associated with Bartonella henselae infection. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2011;82:707–708. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2009.191940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scalf R.E., Wenger D.E., Frick M.A., Mandrekar J.N., Adkins M.C. MRI findings of 26 patients with parsonage-turner syndrome. Am J Roentgenol. 2007;189(1):W39–W44. doi: 10.2214/AJR.06.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gaskin C.M., Helms C.A. Parsonage-turner syndrome: MR imaging findings and clinical information of 27 patients. Radiology. 2006;240(2):501–507. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2402050405. August. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]