Abstract

Background:

Dexmedetomidine (DEX) is a sedative and analgesic that is frequently used post-operatively in children following liver transplantation. Hepatic dysfunction, and including alterations in drug clearance, are common immediately following liver transplantation. However, the pharmacokinetics (PK) of DEX in this population is unknown. The objective of this study was to determine the PK profile of DEX in children following liver transplantation.

Methods:

This was a single center, open-label PK study of DEX administered as an intravenous loading dose of 0.5 mcg/kg followed by a continuous infusion of 0.5 mcg/kg/hr. Twenty subjects, age 1 month to 18 years, who were admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit following liver transplantation were enrolled. Whole blood was collected and analyzed for DEX concentration using a dried blood spot method. Non-linear mixed-effects modeling was used to characterize the population PK of DEX.

Results:

DEX PK was best described by a two-compartment model with first-order elimination. A typical child following liver transplantation with an INR of 1.8 was found to have a whole blood DEX clearance of 52 L/h (95%CI 31-73 L/h). In addition, inter-compartmental clearance was 246 L/h (95%CI 139-391 L/h), central volume of distribution was 186 L/70-kg (95%CI 140-301 L/70-kg), and peripheral volume of distribution was 203 L (95%CI 123-338 L). Inter-individual variability ranged from 11 to 111% for all parameters. Clearance was not found to be associated with weight but was found to be inversely proportional to international normalized ratio (INR). An increase in INR to 3.2 resulted in a 50% decrease in DEX clearance. Weight was linearly correlated with central volume of distribution. All other covariates including age, ischemic time, total bilirubin and alanine amino transferase were not found to be significant predictors of DEX disposition.

Conclusions:

Children who received DEX following liver transplantation have large variability in clearance, which was not found to be associated with weight but is influenced by underlying liver function as reflected by INR. In this population, titration of DEX dosing to clinical effect may be important because weight-based dosing is poorly associated with blood concentrations. More attention to quality of dexmedetomidine sedation may be warranted when INR values are changing.

Introduction

More than 500 pediatric liver transplantations are performed annually in the US [1]. Multiple factors affect liver function after transplantation, including ischemia time with reperfusion injury, donor age, and donor and recipient co-morbidities. Hepatic reperfusion injury produces graft dysfunction [2] as well as vascular and biliary complications [3]. The degree of reperfusion injury is related to ischemic time, duration of surgery, blood flow through the hepatic vessels, and occurrence of perioperative hypotension [4]. Most studies of drug pharmacokinetics (PK) after liver transplantation relate to immunosuppression drugs [5, 6]. There is limited information pertaining to sedative and analgesic medications, yet they are frequently used postoperatively [7, 8, 9, 10]. In children, postoperative sedation and analgesia are needed to optimize comfort and relieve pain, while maintaining graft function. Dexmedetomidine (DEX) is a sedative and analgesic medication with minimal respiratory effects at therapeutic doses [11], thereby facilitating timely extubation following surgery.

DEX is a selective alpha2-adrenergic agonist that is primarily metabolized in the liver. The PK of DEX used for sedation in the pediatric ICU post-operative from a variety of procedures have been reported to be influenced by age, weight and time on cardiopulmonary bypass [12, 13, 14]. The clearance increases from birth in term neonates to reach 84.5% of the mature value by 1 year of age [13]. DEX is highly bound to plasma proteins (94%). The fraction of bound drug decreases in adults with hepatic impairment [15]. After a single dose of DEX administered to adult patients with hepatic insufficiency, the volume of distribution and the elimination half-life increase while the clearance decreases with the severity of illness [16].

There are no PK data for the disposition of DEX in children or adults following liver transplantation, yet alterations in the PK of drugs are anticipated given the frequent hepatic dysfunction. The objective of this study was to determine the PK profile of DEX in children following liver transplantation.

Material and Method

Study conduct

Approval from the Stanford University Institutional Review Board was obtained prior to the commencement of this study. Written informed consent was obtained from parents and/or legal guardians of each subject. Assent was also obtained from children ≥7 years of age. Eligible subjects included infants and children from 1 month to 18 years of age undergoing mechanical ventilation following liver transplantation. DEX infusion was initiated within 6 hours of arrival to the PICU. Exclusion criteria included renal dysfunction defined as serum Cr > 1.5 mg/dL or a creatinine 1.5 times the upper limit of normal for age, subject weight <5 kg, use of renal replacement therapy, persistent post-operative hemodynamic instability, or heart block without an existing pacemaker.

The sample size of 20 subjects was determined based on conventional pediatric PK study size requirements, interest in exploring covariate relationships in this specialized population and enrollment goals based on estimated number liver transplantation during the 12 months study period.

Dexmedetomidine Administration

Following admission to the pediatric intensive care unit post-operatively, subjects received DEX administered as an intravenous loading dose of 0.5 mcg/kg followed by a continuous infusion starting at 0.5 mcg/kg/hr per study protocol. After the initial 6 hours, the primary ICU medical team was able to titrate the dose or discontinue the infusion per standard of care. Supplemental sedative and analgesic drugs were administered as per standard of care at the discretion of the ICU medical team.

Pharmacokinetic Sampling and Drug Quantitation

Whole blood samples for dried blood spot analysis were obtained at the following time points: baseline (prior to DEX administration) then at 5, 10, 15, 30, 60, 120, 240, and 360 minutes following initiation of dexmedetomidine. Additional samples were obtained subsequently every 6 hours until the discontinuation of infusion for up to 72 hours. A PK sample was obtained immediately prior to end of infusion and every 6 hours following discontinuation of DEX for up to 24 hours. For infusion continued for more than 72 hours, no end of infusion samples were obtained. Additional PK samples were obtained prior to any rate change during the initial 72 hours of infusion.

At each sampling time point, ~80 μL whole blood was collected on Whatman 903 filter paper cards (~40 μL whole blood/spot x 2 spots). After drying, the filter paper was stored at −75°C. The concentrations of DEX in whole blood were measured using a validated liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry assay (iC42 Clinical Research and Development, Aurora, CO). The assay was linear in the range of 37.5-3050 pg/mL. The inter-day coefficient of variation was 6.7-8.6%.

Population Pharmacokinetic Analysis

NONMEM 7.2 (ICON Development Solutions, Ellicott City, MD) was used for population PK analysis. All models were run using the first order conditional estimation with interaction (FOCE-I) method. RStudio Version 0.97.320 (RStudio, Inc., Boston, MA) was used for goodness-of-fit diagnostics. Model selection was based on successful NONMEM minimization, the Akaike information criterion to evaluate one, two, and three-compartment model structures, the likelihood ratio test for nested models (covariate model) with a decrease in objective function (OBJ) of >3.84 (p<0.05), visual inspection of diagnostic scatter plots (observed vs. individual and population predicted concentrations, residual/conditional weighted residual vs. predicted concentration or time), the precision of the parameter estimates measured by the percent standard error of the mean, and changes in the inter-individual and residual variability.

Model Development

One, two and three-compartment models were evaluated. Subsequent model exploration was performed using ADVAN3 (2-compartment intravenous) and TRANS4 (parameters clearance, inter-compartmental clearance, central and peripheral volumes of distribution) subroutine. An exponential variance model was used to describe inter-individual variability (IIV) of parameters: Pik = θk exp(ηik), where Pik is the estimated parameter value for individual i for parameter k, θk is the typical population value of parameter k, and ηki is the inter-individual random effect for individual i and parameter k.

Additive, proportional and combined (additive and proportional) error functions were evaluated to describe the residual variability. A combined residual error function was incorporated into the final model: Cobs,ij = (Cpred,ij*(1+εPij))+εAij where Cobs,ij is the observed concentration, Cpred,ij is the individual predicted concentration, εPij is the proportional residual random error and εAij is the additive residual random error for individual i and measurement j.

Covariate Data Analysis

Once the structural PK model was established, biologically or clinically plausible covariates were evaluated for their influence on PK parameters. Covariate analysis occurred using a standard forward addition and backward elimination procedure. An increase in OBJ >6.63 (p <0.01) during backward elimination was considered significant and warranted inclusion of the covariate in the final model. Standard covariates for size (i.e. weight) and development (i.e.age) were included in the covariate analysis. In addition, since liver function after transplantation is affected by multiple factors, covariates including ischemia times, donor age, liver type (reduced or whole), recipient international normalize ratio (INR), total bilirubin (Tbili) and alanine amino transferase (ALT) were also examined [17].

Both allometric and linear weight models standardized to 70-kg adult body weight were used to evaluate the influence of weight on clearances and volumes of distribution:

where Pik is the typical parameter value for individual i and parameter k with weight WTi, θk is the population estimate of parameter k and θallometric is an allometric power parameter. θallometric was fixed at 0.75 for clearances, and 1 for volumes for allometric weight and 1 for both clearances and volumes for linear weight evaluation.

The influence of age and donor age-related effects on clearance was assessed using linear, power and variable slope sigmoidal (Hill equation) models:

where AGE is the subject age and EP50 is the AGE where the parameter value is 50% of its maximal value.

The influence of donor liver ischemic time on clearance was assessed using a power model:

where ITi is the ischemic time for individual i, ITmedian is the median ischemic time and θIT is the power parameter to describe the magnitude of ischemic time effect.

The influence of liver type on clearance was assess using a power model:

where LT was fixed at 0 for reduced and 1 for whole liver transplant and θLT describes the magnitude of effect.

Finally, INR, TBili and ALT were explored as time-dependent covariates. Each subject had liver function tests and coagulation profile per standard of care (on PICU admission and every 6 hours thereafter in the first post-operative day and then daily or twice daily in subsequent post-operative days. Missing covariate values at the time of PK sampling were imputed using linear interpolation. The influence of INR, TBili and ALT were assessed using a power model [18]:

where θCOV is the coefficient to describe the magnitude of time-dependent covariate effect, ηθcov is the inter-individual variability on the covariate effect, COVij is the time-dependent covariate value for individual i and measurement j and COVmedian is the median time-dependent covariate value.

Model Evaluation

A bootstrap analysis was performed on the final PK model to evaluate parameter uncertainty and estimate 95th percentile confidence intervals. One thousand replicates of the dataset were generated by repeated sampling with replacement with each subject as a unit of resampling. The final PK model was used to estimate model parameters for each of the 1000 datasets. The 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles were used to compute the 95th percentile confidence intervals.

Safety Monitoring and Analyses

All subjects had continuous hemodynamic and respiratory monitoring as standard of care. Additionally, laboratory data such as arterial blood gas, chemistries and coagulopathy panels were obtained as standard of care per liver transplant protocol. Dose limiting bradycardia (heart rate < 40-70 bpm) and hypotension (mean arterial pressure < 40 - 60 mmHg) were defined by age.

Results

The demographics and the baseline characteristics of subjects are listed in Table 1. The median age and weight of the subjects were 1.21 years (0.5 to 17.75 years) and 10.75 kg (5.3 to 60 kg), respectively. The median duration of DEX infusion was 20.25 hours (range: 5.8-72 hours).

Table 1:

Subjects demographics and baseline characteristics on admission to PICU

| All subjects | |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 1.2 (0.5 to 18 years old) |

| Age group </= 1 year of age (%) | 50 |

| Age group > 12 years of age (%) | 10 |

| Weight (kg) | 10.8 (5.3-60) |

| Diagnosis (%) | |

| Biliary atresia | 25 |

| Metabolic disease | 40 |

| Acute Hepatic Failure | 10 |

| Malignancy | 5 |

| Other | 20 |

| Liver transplant type (%) | |

| Full liver | 55 |

| Reduced-size liver | 45 |

| Total ischemic time (hours) | 8.1 (1.4-12.5) |

| Total infusion time (hours) | 20.3 (5.8-72.2) |

| International Normalized Ratio (INR) rate of change during the DEX infusion | 0.75 (−0.7 – 6.8) |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dl) rate of change during the DEX infusion | 0.4 (−2.9 to 12.9) |

| ALT (U/L) rate of change during the DEX infusion | 158 (−1216 to 866) |

| Donor age (years) | 6.9 (0.6-41.6) |

| Age group </= 1 year of age (%) | 10 |

| Age group > 12 years of age (%) | 40 |

Results presented as median (range) except where noted

One subject had the DEX infusion started in the operating room without receiving the loading dose with PK sampling initiated in the PICU 6 hours after start of DEX infusion. One subject required initiation of continuous renal replacement therapy on postoperative day two due to acute kidney injury, and DEX sampling was discontinued. Data from all subjects were included in the analysis. Twenty-two percent of the samples were below the limit of quantitation. These samples were included in the PK analysis as their measured values.

The base model was a two-compartment model with covariance between clearance and central volume of distribution inter-individual random effects. All models minimized with successful execution of the covariance step. Allometric weight scaling on clearance did not result in decrease in the objective function. The addition of linear weight to central volume of distribution resulted in a 7-point decrease in the objective function (p<0.05). Age was highly correlated with weight and did not show additional influence on the PK model. The effect of INR on clearance resulted in a 9-point decrease in the objective function (p<0.05). All other covariates, including ischemic time, TBili and ALT, were not found to be significant predictors of DEX disposition.

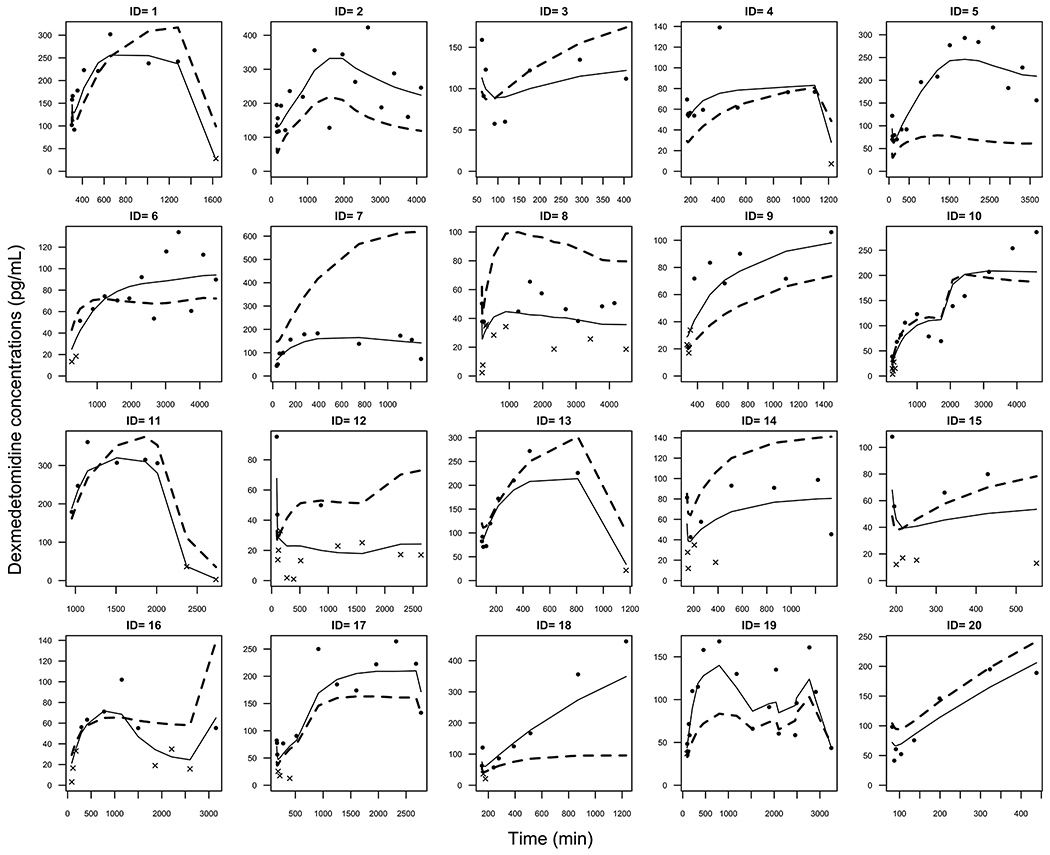

Final parameter estimates and inter-individual variability including standard errors of the point estimates and bootstrap statistics for the final PK model are represented in Table 2. Observed vs. individual and population predicted concentrations are shown in Figure 1. Observed, population and individual predicted concentrations versus time for each subject are presented in Figure 2 while the Inter-individual variability for each subject and parameter may be found in Supplemental Figure 1.

Table 2.

Final parameter estimates. IIV is the inter-individual variability, RSE is the relative standard error and CI is the confidence interval obtained from bootstrap analysis.

| Parameter | Estimate | %IIV | %RSE | Bootstrap 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clearance (L/hr) | 52 | 79 | 14 | 31, 73 |

| Central Volume of Distribution (L/70 kg) | 186 | 11 | 14.7 | 140, 301 |

| Q (L/hr) | 246 | 111 | 33.7 | 139, 391 |

| Peripheral Volume of Distribution (L/70 kg) | 203 | 68 | 22.6 | 123, 338 |

| Coefficient of effect of INR on Clearance | −0.484 | 104 | 78.9 | −1.846, −0.028 |

| Residual Variability (proportional) | 0.24 | 35 | 0.13, 0.28 | |

| Residual Variability (additive) | 15.3 | 30.4 | 12.1, 22.6 |

Clearance covariate model: Clearance (L/hr) = 52 * e[−0.484*(INR - 1.8)]

Figure 1.

Observed versus individual-predicted and observed versus population-predicted concentrations.

Figure 2.

Observed (dot = above limit of quantitation, x = below limit of quantitation), individual-predicted (solid line) and population-predicted (dashed line) concentrations for each subject versus time. DEX infusion for Subject 11 was initiated in the operating room without a bolus dose. Inter-individual variability for each subject and parameter may be found in Supplemental Figure 1.

A typical child following liver transplantation with an INR of 1.8 was found to have a whole blood DEX clearance of 52 L/h (95%CI 31-73 L/h). In addition, inter-compartmental clearance was 246 L/h (95%CI 139-391 L/h), central volume of distribution was 186 L/70-kg (95%CI 140-301 L/70-kg), and peripheral volume of distribution was 203 L (95%CI 123-338 L). Inter-individual variability in pharmacokinetics parameters was large (range 11-111%). There was no significant covariance in the final model. The PK parameters were estimated with acceptable precision as indicated by 95% confidence interval and relative standard error < 35%. There were no clinically significant changes in hemodynamic or respiratory parameters that required discontinuation of the DEX infusion.

Discussion

The major metabolic pathways of DEX are direct N-glucuronidation, aliphatic hydroxylation (mediated primarily by CYP2A6), and N methylation [15]. It is known that any decrease in hepatic function modifies DEX PK, including decreased DEX clearance that correlates with the severity of hepatic dysfunction [16]. It is expected that after liver transplantation multiple complex changes in drug metabolism occur due to factors such as altered hepatic and portal hepatic blood flow, abnormal biliary flow, variations in plasma protein concentrations, and liver regeneration. Metabolic enzymatic functions are compromised as result of ischemia-reperfusion injury, inflammation, graft size, organ preservation and/or donor comorbidities. CYP function changes in the first month following liver transplantation with decreased function of CYP2C19 and significantly increased CYP2E1 function [19]. Those changes in CYP enzyme activity may be explained by ischemia-reperfusion injury and liver regeneration that leads to increased pro-inflammatory cytokine activity [20]. Although CYP2A6 function after liver transplantation has not been reported, multifactorial and dynamic determinants of hepatic blood flow and metabolic activity contribute to the large variability in DEX clearance that we found within our study population.

We studied the PK of DEX in 20 children after liver transplantation. Using dried bloodspot assay and non-linear mixed-effects modeling, a typical child with an INR of 1.8 was found to have a whole blood DEX clearance of 52 L/h (95%CI 31-73 L/h). In addition, inter-compartmental clearance was 246 L/h (95%CI 139-391 L/h), central volume of distribution was 186 L/70-kg (95%CI 140-301 L/70-kg), and peripheral volume of distribution was 203 L (95%CI 123-338 L). In a pooled analysis of 4 PK studies in children, plasma DEX clearance was as low as 18 L/h at birth to 42 L/h in children undergoing cardiac surgeries [21]. In a study of 36 infants after cardiac surgery, plasma DEX clearance was 16.8 L/h and dependent on age, weight, total bypass time and cardiac anatomy [22] while a separate study of 20 critically ill infants clearance was 48L/h with an inter-individual variability of 35% [23]. In this population, clearance was influenced by post-gestational age and prior history of cardiac surgery. In a study of 38 critically ill children, with a median age of 70 months, plasma DEX clearance was 41.6 L/h with a variability of 30.9 % [24]. Volume of distribution at steady state has been reported to be 56.3 to 107.1 L/70-kg in children, 118 L/70-kg in healthy adults, and 104 L/70-kg in critically ill adults [11,12, 13,14, 15, 17]. Direct comparison of our findings to those published in the literature is limited due to differences in plasma and whole blood concentration measurements. Nevertheless, variability and relationships with covariates are important to compare and explore.

Our findings that the PK of DEX is highly variable after liver transplantation are consistent with a small number PK studies of other drugs administered post-transplantation including morphine and oxycodone [7, 8]. The variability of plasma DEX clearance in pediatric population have been reported to be ranging between 22% to 35%. DEX PK studies in critical care adults reported higher variability in PK estimates [25, 26, 27] with plasma DEX clearance variability estimated at 67% (CI 40-95%) in one study [22]. These findings were attributed to critical illness, concomitant medication administration, decreased P450 enzymes quantity and function, and possibly low hepatic blood flow associated with injury and/or shock requiring vasopressors.

Allometric scaling is commonly used for estimation of drug clearance in children where a nonlinear relationship between weight and drug clearance exists in normal pediatric growth and development [28] although others argue there are limitations and misconceptions to this approach [29]. Transplanted liver mass-to-body weight ratio has been reported as a significant covariate in clearance of other medications including tacrolimus in the early postoperative period [5,30]. The PK of tacrolimus has also been found to depend on liver type, with reduced livers expressing an apparent clearance significantly lower than whole livers (5.75 versus 44 L/h) thought secondary to higher drug exposure relative to the total metabolic enzyme content in adults [31]. In contrast with previous reports of DEX PK, patient weight did not have significant influence on DEX clearance in our population. Additionally, DEX clearance did not appear to be affected by liver type. The lack of association between patient weight or liver type and DEX clearance may be attributed to transplanted liver mass-to-body weight differences in our patient population. Transplant liver mass is dependent on liver type (reduced or whole) and the body mass of the donor rather than the recipient. Children receiving liver transplants often do not receive size-matched livers. The new graft mass is typically sized greater the patient’s native liver, particularly when a reduced liver is used. In our cohort, 9 (45%) of subjects received a reduced liver. Without the transplanted liver mass, we were not able to explore the relationship between transplanted liver mass and DEX clearance in our study.

As liver function is affected by multiple factors, variables including cold and warm ischemic times, donor age, recipient INR, total bilirubin and ALT were collected for inclusion in the covariate analysis. INR, ALT and TBili were used as markers of liver function. After liver transplantation, tacrolimus clearance has been shown to be inversely correlated with AST and bilirubin, while volume of distribution was inversely correlated with albumin levels [6]. Similar findings were found in critical care adults with respect to DEX [27]. In our population, INR was found to have an inverse relationship with DEX clearance, suggesting that DEX clearance is inversely proportional with the severity of liver dysfunction as previously reported by Cunningham et all [16].

Children undergoing liver transplantation represent a very heterogeneous population in terms of donor and recipient age and underlying disease, which likely contributes to the variability in our study. In addition, there are several limitations to our study. The small sample size of twenty patients limits our ability to estimate PK parameters with significant precision evidenced by the wide confidence intervals and our ability to define covariate relationships. There were also a number of samples below the limit of quantitation. As we did not measure the mass or the volume of the transplanted liver, we were not able to directly evaluate the relationship between liver size and DEX clearance. We used dried blood spot analysis, a laboratory method whereby drug concentrations are measured using only a single drop of blood. This method is widely used in newborn screening, ribonucleic acid (RNA) and hormone detection, and therapeutic drug monitoring [32, 33, 34]. In children it is important to use small blood samples in order to minimize iatrogenic anemia and the need for blood transfusion. Although dried blood spot analysis limited our ability to directly compare to other studies of DEX PK, the knowledge gained through this study provides the first PK framework for DEX disposition in a highly vulnerable pediatric population. The model developed may be used for future dosing considerations and design of clinical studies.

Conclusions

DEX clearance following liver transplantation is highly variable and was not associated with patient weight in this study. DEX clearance is influenced by liver function as reflected by INR. Titration of DEX dosing to clinical effect is especially important in children after liver transplantation because as weight-based dosing may be poorly associated with blood concentration. In addition to clinical signs, INR may be used to help guide titration.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure 1. Inter-individual variability for: A) clearance, B) central volume of distribution, C) intercompartmental clearance, D) peripheral volume of distribution. Dashed lines represent 25th & 75th quantiles.

Key points Summary:

What are the PK indices of Dexmedetomidine (DEX) used post-operatively in children following pediatric liver transplantation?

Children who received DEX following liver transplantation have large variability in clearance, which is not associated with weight but is influenced by underlying liver function as reflected by INR.

In this population, titration of DEX dosing to clinical effect is especially important because weight-based dosing is poorly associated with blood concentrations.

Acknowledgements

This study was performed in collaboration with the Dr. Jeffrey L. Galinkin, MD, Professor of Anesthesiology and Pediatrics at University of Colorado (Aurora, Co, USA) and Dr. Uwe Christians, MD, Ph.D., Professor of Anesthesiology at University of Colorado (Aurora, Co, USA) from the iC42 Clinical Research and Development Laboratory, University of Colorado (Aurora, CO, USA) where all the blood samples were anayzed, Stanford Clinical Data warehouse, Stanford University, Palo Alto, Ca, USA provided clinical data collection. This research would not have been possible without the support of the Division of Pediatric Critical Care Medicine and the Pediatric Liver Transplant Program at Stanford University School of Medicine and the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit staff at Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital Stanford.

Funding: Child Health Research Institute, Ernest and Amelia Gallo Endowed Postdoctoral Fellow, NIH CTSA UL1 RR025744.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest/Financial Disclosures: None

References

- 1.Rawal N, Yazigi N. Pediatric liver transplantation. Pediatr Clin N Am 64 (2017) 677–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Washington K Update on post-liver transplantation infections, malignancies, and surgical complications. Adv.Anat.Pathol 2005. July;12(4): 221–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ben-Ari Z, Pappo O, and Mor E. Intrahepatic cholestasis after liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2003. October;9(10), 1005–1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Serracino-Inglott F, Habib NA, Mathie R. Hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury. Am J Surg 2001. February:181(2):160–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wallin JE, Bergstrand M, Wilczek HE, Nydert S, Karlsson O, Staatz CE. Population Pharmacokinetics of tacrolimus in pediatric liver transplantation: Early posttransplantation clearance. Ther Drug Monit. 2011. December;33(6):663–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Musuamba FT, Guy-Viterbo V, Reding R, Verbeeck RK, Wallemacq P. Population pharmacokinetic analysis of tacrolimus early after pediatric liver transplantation. Ther Drug Monit. February 2014;36(1):54–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shelly MP, Quinn KG, Park GR. Pharmacokinetics of morphine in subjects following orthotopic liver transplantation; Br J Anesth. 1989. October;63(4): 375–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tallgren M, Olkkola KT, Seppala T, Hockestedt K, Lindgren L. Pharmacokinetics and ventilatory effects of oxycodone before and after liver transplantation. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1997. June; 61(6):655–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shelly MP, Dixon JS, Park GR. The pharmacokinetics of midazolam following orthotropic liver transplantation. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1989. May 27(5), 629–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chow B, Bowden MI, Ho E, Weatherley C, Bion JF. Pharmacokinetics and dynamics of atracurium infusions after paediatric orthotopic liver transplantation. Br J Anaesth 2000. December; 85(6): 850–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Su F, Hammer GB. Dexmedetomidine: pediatric pharmacology, clinical uses and safety. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2011. January 10(1): 55–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Su F, Nicolson SC, Gastonguay MR, et al. Population Pharmacokinetics of dexmedetomidine in infants following open heart surgery. Anesth Analg. 2010. May 1; 110(5): 1383–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Díaz SM, Rodarte A, Foley J, Capparelli EV. Pharmacokinetics of Dexmedetomidine in postsurgical pediatric intensive care unit subjects: Preliminary study. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2007. September;8(5):419–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Potts AL, Anderson B, Warman GR, Lerman J, Diaz SM, Vilo S. DEX pharmacokinetics in pediatric intensive care-a pooled analysis. Paediatr Anaesth. 2009. November; 19 (11):1119–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Precedex (DEX) package insert. Lake Forest, IL: Hospira, Inc., 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cunningham FE, Baughman VL, Tonkovich L, Lam N, Layden T. Pharmacokinetics of dexmedetomidine in subjects with hepatic failure. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics, February 1999. 65, 128–128. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anderson BJ, Allegaert K, Holford NH. Population clinical pharmacology of children: modeling covariate effects. Anderson 2006. Eur J Pediatr. 2006. December; 165(12):819–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wählby U, Thomson AH, Milligan PA, Karlsson MO. Models for time-varying covariates in population pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic analysis. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2004. October;58(4):367–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu S, Frye RF, Branch RA, Venkataramanan R, Fung JJ, Burckart JJ. Effect of age and postoperative time on cytochrome p450 enzyme activity following liver transplantation. J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;45: 666–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li M, Zhao Y, Humar A, Tevar AD, Hughes C, Venkataramanan R. Pharmacokinetics of drugs in adult living donor liver transplant patients: regulatory factors and observations based on studies in animals and humans. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2006. October 1;43:282–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Petroz GC, Sikich N, James M, et al. A phase I, two-center study of the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of dexmedetomidine in children. Anesthesiology 2006; 105: 1098–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Su F, Gastonguay MR, Nicolson SC, DiLiberto M, Ocampo-Pelland A, Zuppa AF. Dexmedetomidine pharmacology in neonates and infants after open heart surgery; Anesth Analg. 2016. May;122(5):1556–66. doi: 10.1213/ANE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Greenberg RG, Wu H, Laughon M et al. Population Pharmacokinetics of Dexmedetomidine in Infants. J Clin Pharmacol 2017. September; 57(9) 1174–1182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wiczling P, Bartkowska-Sniatkowska A, Szerkus O, et al. The pharmacokinetics of dexmedetomidine during long-term infusion in critically ill pediatric patients. A Bayesian approach with informative priors. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn (2016) 43:315–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iirola T, Ihmsen H, Laitio R, et al. Population pharmacokinetics of dexmedetomidine during long-term sedation in intensive care patients. Br J Anaesth. 2012. March;108 (3): 460–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holliday SF, Kane-Gill SL, Empey PE, Buckley MS, Smithburger PL. Interpatient variability in dexmedetomidine response: A Survey of the Literature. Scientific World Journal. 2014. January 16;2004:805013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Valitalo PA, Ahtola-Satila T, Wighton A, Sarapohja T, Pohjanjousi P, Garratt C. Population pharmacokinetics of dexmedetomidine in critically ill patients. Clin Drug Investig 2013. August; 33(8):579–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Foissac F, Bouazza N, Valade E, et al. , Prediction of drug clearance in children. J Clin Pharmacol. 2015. July; 55(7): 739–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fisher DM, Shafer SL.; Allometry, Shallometry!. Anesth Analg 2016. May;122(5) 1234–1238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ganesh S, Almazroo OA, Tevar A, Humar A, Venkataramanan A. Drug metabolism, drug interactions, and drug-induced liver injury in living donor liver transplant patients. Clin Liver Dis. 2017. February; 21 (1) 181–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Staatz CE, Taylor PJ, Lynch S, Willis C, Charles G, Tett SE. Population pharmacokinetics of tacrolimus in children who receive cut-down or full liver transplants. Transplantation. 2001. September 27;72(6): 1056–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Antunes MV, Charão MF, Linden R. Dried blood spots analysis with mass spectrometry: Potentials and pitfalls in therapeutic drug monitoring. Clin Biochem. 2016. September;49(13-14): 1035–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Patel P, Mulla H, Tanna S. Facilitating pharmacokinetic studies in children: a new use of dried blood spots. Arch Dis Child 2010. June; 95(6): 484–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Clavijo C, Bendrick-Peart J, Zhang YL, Johnson G, Gasparic A, Christians U. An automated, highly sensitive LC-MS/MS assay for the quantification of the opiate antagonist naltrexone and its major metabolite 6beta-naltrexol in dog and human plasma. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2008; 874: 33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure 1. Inter-individual variability for: A) clearance, B) central volume of distribution, C) intercompartmental clearance, D) peripheral volume of distribution. Dashed lines represent 25th & 75th quantiles.