Abstract

Purpose

Research shows that the professional healthcare working environment influences the quality of care, safety climate, productivity, and motivation, happiness, and health of staff. The purpose of this systematic literature review was to assess instruments that provide valid, reliable and succinct measures of health care professionals’ work environment (WE) in hospitals.

Data sources

Embase, Medline Ovid, Web of Science, Cochrane CENTRAL, CINAHL EBSCOhost and Google Scholar were systematically searched from inception through December 2018.

Study selection

Pre-defined eligibility criteria (written in English, original work-environment instrument for healthcare professionals and not a translation, describing psychometric properties as construct validity and reliability) were used to detect studies describing instruments developed to measure the working environment.

Data extraction

After screening 6397 titles and abstracts, we included 37 papers. Two reviewers independently assessed the 37 instruments on content and psychometric quality following the COSMIN guideline.

Results of data synthesis

Our paper analysis revealed a diversity of items measured. The items were mapped into 48 elements on aspects of the healthcare professional’s WE. Quality assessment also revealed a wide range of methodological flaws in all studies.

Conclusions

We found a large variety of instruments that measure the professional healthcare environment. Analysis uncovered content diversity and diverse methodological flaws in available instruments. Two succinct, interprofessional instruments scored best on psychometrical quality and are promising for the measurement of the working environment in hospitals. However, further psychometric validation and an evaluation of their content is recommended.

Keywords: work environment, organizational culture, hospital, instruments, psychometric properties, systematic review

Purpose

A positive work environment (WE) for healthcare professionals is an important variable in achieving good patient care [1] and is strongly associated with good clinical patient outcomes, e.g. low occurrence of patient falls and pressure ulcers, good pain management, low hospital mortality and hospital acquired infections rates [2, 3]. Associated with efficiency, e.g. fewer re-admissions and adverse events [2–4], a positive WE is a prerequisite for a safety climate and a high performing organization that finds quality improvement a part of daily practice [2, 5, 6]. Research shows that when healthcare professionals perceive a positive WE, they have more job satisfaction and are therefore likely to stay longer; fewer staff will suffer burnout or work-related stress [7–10].

In general, WE is defined as the inner setting of the organization FOR which staff work [11]. In healthcare, a positive WE is defined as a setting that supports excellence and decent practices that strive to ensure health, safety and the personal well-being of staff, support quality patient care and improve the motivation, productivity and performance of individuals and organizations [12]. Pearson et al. [13] explains the relevant elements of WE as ‘a workplace environment characterized by: the promotion of physical and mental health as evidenced by observable positive health and well-being, job and role satisfaction, desirable recruitment and retention rates, low absenteeism, illness and injury rates, low turnover, low involuntary overtime rates, positive inter-staff relationships, low unresolved grievance rates, opportunities for professional development, low burnout and job strain, participation in decision-making, autonomous practice and control over practice and work role, evidence of strong clinical leadership, demonstrated competency and positive perceptions of the work environment including perceptions of work-life balance.’

A positive WE stems from respect and trust between colleagues at all levels, effective collaboration and communication between all educational levels within a profession, different disciplines and working on different departments [14], recognition for good work, a safe atmosphere, positive climate and support from management [5, 6].

Measuring WE is not easy, since this multidimensional concept encompasses diverse elements [13, 15]. Some WE measuring instruments focus on specific professions (e.g. nursing [16–18], physicians [19, 20], residents [21], management [22, 23]) or specific wards (e.g. intensive care units [17], critical care [24], cardiac care [25]) or include only one or two aspects of WE (e.g. ethics, social climate [26], organizational culture [27–29], organizational climate [30]). Achieving a positive WE is not just up to the members of one profession in one department, but a challenge for a team with members from various professions, roles or departments and even organizational boundaries [14, 31]. WE is not the sole responsibility of management, but of management and healthcare professionals together. Therefore, a WE measurement instrument should measure all members of a team and not just those from one profession, one department or one or two aspects of WE.

If hospitals pursue systematic and objective insights into their WE with a valid, reliable and succinct measurement tool, they would gain an understanding of the influential factors that would allow them to improve WE for the benefit of their patients, staff and organization. The aim of this systematic review was to assess instruments that provide valid, reliable and succinct measures of health care professionals’ WE in hospitals.

Data sources and study selection

To find an instrument that staff can use to assess their WE, we performed a three-step study. First, we systematically searched the literature to detect all available WE measuring instruments. Second, we assessed the content of these instruments. Third, we assessed instrument quality with the COSMIN guidelines [32, 33], particularly their psychometric properties. To ensure optimal clarity and transparency, we used the PRISMA reporting guideline to structure this paper [34].

Step 1: systematic literature searches

One researcher (SM) and a librarian systematically searched Embase, Medline Ovid, Web of Science, Cochrane, CENTRAL, CINAHL, EBSCOhost and Google Scholar using key words and their synonyms: ‘WE,’ ‘organizational culture’ and ‘measurement’ (see Supplementary File 1) from inception through December 2018. No search limits were used for language, publication date or type of research. Titles and abstracts of retrieved papers were independently reviewed for inclusion by two researchers (SM and CO). The inclusion criteria were: (i) written in English, the paper describes the development of an original WE measuring instrument for healthcare professionals in hospitals; (ii) the instrument is not a translation of another instrument; (iii) the paper describes psychometric properties with at least some form of construct validity and reliability. Given our focus on the WE of all hospital staff, we excluded papers describing WE instruments in a single profession in one department.

The reviewers discussed to the point of consensus any differences in their assessments of potentially eligible papers. Full versions of eligible papers were then scrutinized independently by three researchers (SM, CO and GB) and cited references were assessed to find additional instruments. Disagreements on these assessments were discussed with a fourth researcher (AMW) until consensus was reached.

Data extraction

Step 2: content assessment

Based on a pre-defined data extraction form two researchers independently (SM, CO, GB or AMW) extracted the study context and instrument content. Study context included research design, country, clinical setting, number and types of health care staff. Instrument content included primary goal, measurement type, focus of interest and number of items, subscales, sample, and study setting.

Next, to enable comparative analysis of the contents, two researchers (SM and CO) independently sorted and clustered all items/subscales of the instruments into elements. Their content analyses were discussed up to consensus by the whole research team.

Step 3: quality assessment

To appraise the methodological quality of the instruments, we assessed their psychometric properties: measurement development, internal consistency, reliability, structural validity, criterion validity, hypothesis testing for construct validity, measurement error and responsiveness. We used the consensus-based standards for the selection of health measurement instruments (COSMIN) risk of bias checklist [32, 35]. The COSMIN checklist was developed to assess the methodological quality of single studies included in systematic reviews of patient-reported outcome measures (PROM) [32]. Although the subject of our review is a staff outcome measurement and not a PROM, this assessment method is useful because the purpose remains the same: screening for the risk of bias. The COSMIN risk of bias checklist is a modular tool, which means that only the measurement properties that were described in a paper were assessed [32]. COSMIN contains two boxes on content validity. The second box focuses on detailed content validity development issues and is not suitable for the type of studies included in this review. Therefore, we used only the first box, ‘PROM development.’ Table 1 lists the definitions of properties as applied in this review.

Table 1.

Definitions of measurement properties [33]

| Measurement property | Definition |

|---|---|

| Content development | The degree to which the content of a measurement instrument is an adequate reflection of the construct to be measured |

| Internal consistency | The degree to which different items of a (sub)scale correlate and measure the same construct (interrelatedness) |

| Reliability | The extent to which scores for persons who have not changed are the same for repeated measurement under several conditions |

| Structural validity | The degree to which the scores of an instrument are an adequate reflection of the dimensionality of the construct to be measured |

| Criterion validity | The degree to which the scores of an instrument are an adequate reflection of a ‘golden standard’ |

| Hypothesis testing for construct validity | The degree to which the scores of the instrument are consistent with the hypotheses based on the assumption that the instrument measures the construct to be measured |

| Measurement error | The systematic and random error of a patient’s score that is not attributed to true changes in the construct to be measured |

| Responsiveness | The ability of an instrument to detect change over time in the construct to be measured |

Two researchers (SM and CO) appraised quality on a four-point scale (very good-adequate-doubtful-inadequate). Their ratings were independently crosschecked by two other researchers (GB and AMW). The methodological quality score for each psychometric property was determined by the lowest rating of any item in that category [32]. When applicable, the measurement properties were rated by the ‘criteria for good measurement properties’ as described by Mokkink et al. [32]. Properties were judged as ‘sufficient’ (+), ‘insufficient’ (−) or ‘indeterminate’ according to the COSMIN standards [35].

Results of data synthesis

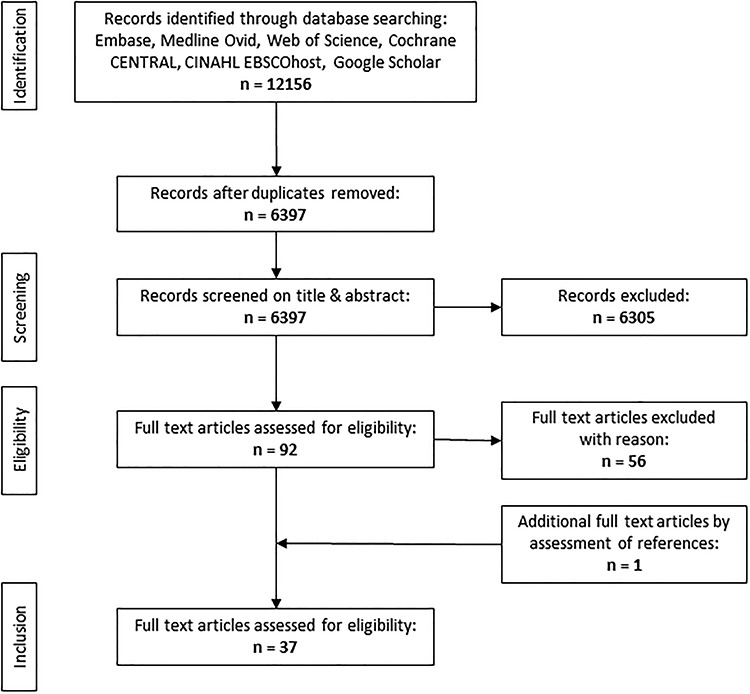

The search strategy (see Figure 1) yielded 6397 individual papers. After screening the titles and abstracts, 6305 papers were excluded because they did not describe the development of an original instrument to measure the WE of healthcare professionals or did not provide psychometric details. This resulted in 92 potentially relevant papers eligible for full text screening. After full text screening, another 57 papers were excluded based on the inclusion criteria. Assessing the references cited in the included papers found one other relevant study for a total of 37 included papers.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of search and selection procedure conform PRISMA [34].

The 37 papers each describe an individual self-assessment instrument, all using Likert scales to reflect on the degree of agreement with a specific proposition about the WE. Going from the date of the oldest publication (1984), development of instruments to measure the WE of healthcare professionals began in 1984 and has been continuously under development since then (see Table 2). Studies took place in the USA (20/37), Canada (4/37), Australia (3/37), UK (3/37) Japan (1/37) and European Union (7/37). More than half (20/37) sampled healthcare professionals in the nursing domain: e.g. nurses/nurse assistants [36–53]. Other studies applied samples of diverse healthcare professionals [54–70]. Most studies focused on measuring WE as a total concept [36–39, 41, 43–45, 48–56, 59, 62, 68, 71, 72] despite terming it differently sometimes, e.g. practice environment [41, 43–45, 49, 52, 56, 68], ward environment [37] or healthy WE [39, 59, 71]. Seven studies focused primarily on culture, as in organizational culture [42, 61, 66], hospital culture [60], nursing [47] or ward culture [63] and culture of care [65]. Additionally, we found WE instruments with a focus on organizational [57, 64, 70] or psychological climate [58] in contrast to instruments that focus on teamwork [46] or aspects of teamwork, such as team vitality [69], team collaboration [67] and workplace relationships [40].

Table 2.

Content and context of work-environment measuring instruments

| Author | Year | Sample and setting | Instrument | Focus | Measurement type | No. of items |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abraham and Foley [36] | 1984 | Nursing students in mental health nursing, USA |

Work-environment scale, short form (WES-SF) |

Work environment | 4-point Likert, agreement | 40 |

| Adams, Bond [37] | 1995 | Registered nurses in inpatient hospital wards, UK |

Ward organizational features scale (WOFS) |

Ward environment | 4-point Likert, agreement | 105 |

| Aiken and Patrician [38] | 2000 | Nurses in hospitals (specialized AIDS units and general medicine), USA |

Revised nursing work index (NWI-R) | Nursing work environment | 4-point Likert, agreement | 57 |

| Appel, Schuler [54] | 2017 | Physicians and nurses in hospitals (ICU, ER, intermediate care, regular wards, OR), Germany |

Kurzfragenbogen zur arbeitsanalyse (KFZA) |

Work environment | 5-point Likert scale | 26 SV 37 LV |

| Berndt, Parsons [39] | 2009 | Nurses in hospitals, USA | Healthy workplace index (HWPI) |

Healthy workplace | 4-point Likert, agreement and presence | 32 |

| Bonneterre, Ehlinger [55] | 2011 | Nurses and nurse assistants in hospitals, France |

Nursing work index—extended organization (NWI-EO) | Psychosocial and organizational work factors | 4-point Likert, agreement | 22 |

| Clark, Sattler [71] | 2016 | Nurses in hospitals, United States | Healthy work-environment inventory (HWEI) | Healthy work environment | 5-point Likert, presence | 20 |

| Duddle and Boughton [40] | 2008 | Nurses in a hospital, Australia | Nursing workplace relational environment scale (NWRES) | Nursing workplace relational environment | 5-point Likert, agreement | 22 |

| Erickson, Duffy [56] | 2004 | Nurses, occupational therapist, physical therapy, respiratory therapy, social services, speech pathology and chaplaincy working within one hospital. United States |

Professional practice environment scale (PPE) |

Practice environment | 4-point Likert, agreement | 39 |

| Erickson, Duffy [41] | 2009 | Nurses within one hospital, USA | Revised professional practice environment scale (RPPE) | Practice environment | 4-point Likert, agreement | 39 |

| Estabrooks, Squires [42] | 2009 | Nurses in pediatric hospitals, Canada |

Alberta context tool (ACT) | Organizational context | 5-point Likert, agreement or presence | 56 |

| Flint, Farrugia [43] | 2010 | Nurses within two hospitals, Australia |

Brisbane practice environment measure (B-PEM) | Practice environment | 5-point Likert, agreement | 26 |

| Friedberg, Rodriguez [57] | 2016 | Clinicians (physicians, nurses, allied health professionals) and other staff (clerks, receptionist) in community clinics and health centers, United States |

Survey of workplace climate | Workplace climate | 5-point Likert, agreement and 1 item: 5-point scale (1 calm—5 hectic/chaotic) | 44 |

| Gagnon, Paquet [58] | 2009 | Health care workers (nurses, health care professionals, technicians, office staff, support staff and management) within one health care center, Canada |

CRISO Psychological climate questionnaire (PCQ) | Psychological climate | 5-point Likert, agreement | 60 |

| Ives-Erickson, Duffy [44] | 2015 | Patient care assistants, within two hospitals, USA |

Patient Care Associates’ Work-environment scale (PCA-WES) |

Practice environment | 4 -point Likert, occurrence | 35 |

| Ives Erickson, Duffy [45] | 2017 | Nurses within one hospital, USA | Professional practice work-environment inventory (PPWEI) |

Practice environment | 6-point Likert, agreement | 61 |

| Jansson von Vultée [59] | 2015 | Health care personal, task advisors, employees at advertising, daycare and in leadership programs, Sweden |

Munik questionnaire | Healthy workplaces | 4-point Likert, agreement | 65 |

| Kalisch, Lee [46] | 2010 | Nurses and nurse assistants in hospitals, USA |

Nursing teamwork survey (NTS) | Nursing teamwork | 5-point Likert appearance | 33 |

| Kennerly, Yap [47] | 2012 | Nurses and nurse assistants in long term care, hospital, ambulatory care, USA |

Nursing culture assessment tool (NCAT) |

Nursing culture | 4-point Likert, agreement | 22 |

| Klingle, Burgoon [60] | 1995 | Patients, nurses and physicians, USA | Hospital culture scale (HSC) | Hospital culture | 5-point Likert, agreement | 15 |

| Kobuse, Morishima [61] | 2014 | Physicians, nurses, allied health personnel, administrative staff, other staff in hospitals, Japan |

Hospital organizational culture questionnaire (HOCQ) |

Organizational culture | 5-point Likert, agreement | 24 |

| Kramer and Schmalenberg [48] | 2004 | Nurses in hospitals, USA | Essentials of Magnetism tool (EOM) | Nursing work environment | 62 | |

| Lake [49] | 2002 | Nurses in hospitals, USA | Practice environment scale of the nursing work index (PES-NWI) |

Practice environment | 4-point Likert, agreement | 31 |

| Li, Lake [50] | 2007 | Nurses in hospitals, USA | Short form of NWI-R | Nursing work environment | 4-point Likert, agreement | 12 |

| Mays, Hrabe [51] | 2010 | Nurses and nurse managers in hospitals, USA |

N2N Work-environment scale | Nursing work environment | 5-point rating scale | 12 |

| McCusker, Dendukuri [62] | 2005 | Employees from rehabilitation services, diagnostic services, other clinical services and support services in one hospital, Canada |

Adapted 24 version NWI-R | Work environment | 4-point Likert, agreement | 23 |

| McSherry and Pearce [63] | 2018 | Nurses, physicians, allied health care and supporting staff in hospitals, UK |

Cultural health check (CHC) | Ward culture | 4-point Likert, occurrence | 16 |

| Pena-Suarez, Muniz [64] | 2013 | Auxiliary nurse, administrator assistant, porter, laboratory technician, X-ray technician and others (nurses and physicians excluded) within health services of Austria, Spain |

Organizational climate scale (CLIOR) | Organizational climate | 5-point Likert, agreement | 50 |

| Rafferty, Philippou [65] | 2017 | Nurses, allied health professionals, physicians, administrative and care assistant in in and outpatients mental health and community care, United Kingdom |

CoCB | Culture of care | 5-point Likert, agreement and 1 open question | 31 |

| Reid, Courtney [52] | 2015 | Nurses in professionals and industrial organizations, Australia | Brisbane practice environment measure (B-PEM) |

Practice environment | 5-point Likert, agreement | 28 |

| Saillour-Glenisson, Domecq [66] | 2016 | Physicians, nurses and orderlies in hospitals, France |

Contexte organisationnel et managérial en etablissement de santé (COMEt) |

Organizational culture | 5-point Likert, agreement | 82 |

| Schroder, Medves [67] | 2011 | Health care professionals from different backgrounds working in health care teams, Canada |

Collaborative practice assessment tool (CPAT) | Team collaboration | 7-point Likert, agreement and 3 open questions |

56 |

| Siedlecki and Hixson [68] | 2011 | Nurses and physicians in one hospital, USA |

Professional practices environment assessment scale (PPEAS) | Professional practice environment |

10-point rating scale | 13 |

| Stahl, Schirmer [72] | 2017 | Midwives within hospitals, Germany | Picker Employee Questionnaire—Midwives |

Work environment | Different rating types with 2–16 answer options |

52 |

| Upenieks, Lee [69] | 2010 | Front line nurses, physicians and ancillary health care providers in hospitals, United States |

Revised health care team vitality instrument (HTVI) |

Team vitality | 5-point Likert, agreement | 10 |

| Whitley and Putzier [53] | 1994 | Nurses in one hospital, USA | Work quality index | Work environment | 7-point Likert, satisfaction | 38 |

| Wienand, Cinotti [70] | 2007 | Physicians, scientist, management, nurses, therapists, laboratory and radiology technicians in hospitals and outpatient clinics, Italy |

Survey on organizational climate in health care institutions (ICONAS) |

Organizational climate | 10-point rating scale | 48 |

Content

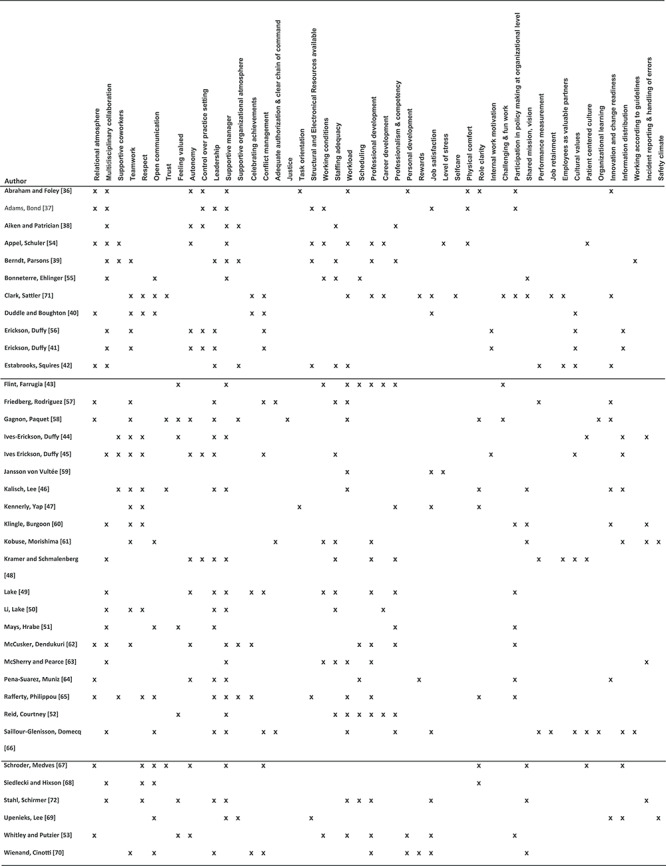

The number of items in the instruments range from 12 to 105 with a mean of 44 items (see Table 2). Sorting and clustering the subscales/items up to consensus resulted in 48 WE elements (see Table 3 and Supplementary File 2). Based on the content comparison, we conclude that 21 instruments measure the environment of clinical inpatient settings [36–39, 41, 43–45, 48–56, 62, 68, 71, 72], sharing common features in terms of items and constructs, e.g. multidisciplinary collaboration [36–39, 41, 44, 48–51, 54–56, 62, 68, 72], autonomy [36, 38, 41, 45, 48, 49, 53, 54, 56, 62], informal leadership [37, 39, 41, 44, 48–51, 56, 72] or supportive management [36–39, 43, 44, 48–50, 52, 54, 55, 62, 72]. Other frequently used constructs and items are staffing adequacy [38, 39, 45, 48–50, 52, 55], workload [36, 43, 52–54, 59, 71, 72] or working conditions [37, 43, 49, 53–55], and professional development [39, 43, 48, 49, 52–54, 62, 71, 72] or professionalism and competency [38, 39, 43, 48, 49, 51, 52, 62]. We found no commonalities among the items and constructs used in instruments focused on culture [42, 47, 60, 61, 63, 65, 66]. These instruments emphasize informal leadership [57, 58, 64, 70], innovation and readiness for change [57, 58, 64] and relational atmosphere [57, 58, 64]. Items on respect [40, 46, 67], teamwork [40, 46], open communication [40, 67, 69], supportive management [46, 67, 69] and information distribution [46, 67, 69] are predominantly present in the instruments that emphasize teamwork.

Table 3.

Content mapping of the instruments

|

Some instruments were developed years ago and have undergone several updates; e.g. the Nursing Work Index [38, 49, 50, 55, 62], Professional Practice Environment [41, 45, 56] and Brisbane practice environment measure [43, 52]. Adapted versions were frequently developed for a different sample than the original instrument [41, 52, 55, 56, 62]. Although several instruments have a development history, the process is not always described properly. Only the instruments developed by Adams, Bond [37], Kramer and Schmalenberg [48], Rafferty, Philippou [65] and Stahl, Schirmer [72] provide enough information on the developmental process to gain an adequate COSMIN score. Some authors refer to other publications for descriptions of the item development process and face or content validity [42, 50, 52, 54, 63].

Methodological quality

Overall, judged by the COSMIN guideline, the methodological quality of the studies is basic but adequate (see Table 3). Most authors explain the structural validity and internal consistency. However, three instruments were rated as inadequate [53, 59, 67] and five as doubtful [37, 41, 60, 63, 66] for structural validity. Ten studies applied confirmative factor analysis, mostly alongside an exploratory factor analysis [43, 46, 47, 52, 57, 58, 64, 66, 67, 69]. Internal consistency measures were calculated and reported with Cronbach’s alpha by all but three authors [36, 59, 69]. Only Pena-Suarez, Muniz [64] conducted cross-cultural validity, although their method was inadequate.

In 12/37 studies, the criteria for sufficient internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha > 0.7 for each subscale [32]) were not met [37, 42, 47, 48, 52, 54, 55, 58, 62, 66, 67, 72].

Other measurement properties were too scattered for both method and method quality to assess criterion validity or hypothesis testing. Other fundamental measurement properties were performed arbitrarily and if available, the quality can be considered as doubtful. Best overall quality assessment was found for the culture of care barometer (CoCB) [65] and the Picker Employee Questionnaire for Midwives [72] because of their overall adequate score on COSMIN criteria and sufficient statistical outcome for internal consistency. That said, measurement properties such as reliability, hypothesis testing and criterion validity have not yet been established for these relatively new instruments (Table 4).

Table 4.

Quality assessment of methodology in work-environment instruments

| Author, year | Quality of instrument development | n | Structural validity | Internal consistency | Other measurement properties | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meth. quality | Rating | Meth. quality | Rating | Yes/no | Specification | Meth. quality | Rating | |||

| Abraham and Foley [36] | Inadequate | 153 | Doubtful | ? | No | |||||

| Adams, Bond [37] | Adequate | 834 | Doubtful | - EFA loadings NR | Very good | - α 0.92–0.66 | Yes | Reliability measurement error | Doubtful inadequate | - Pearson r 0.90–0.71? NR |

| Aiken and Patrician [38] | Inadequate | 2027 | Doubtful | ? Α 0.79–0.75 | Yes | Reliability hypothesis testing |

Inadequate Inadequate | ? NR? NR | ||

| Appel, Schuler [54] | OP | 1163 | Adequate | - EFA loadings SV 0.86–0.36; LV NR |

Very good | - α: LV 0.87–0.60 SV 0.80–0.63 | No | |||

| Berndt, Parsons [39] | Doubtful | 160 | Adequate | - EFA loadings 0.87–0.45 | Very good | + α 0.92–0.88 | Yes | Hypothesis testing |

Very good | + OOM |

| Bonneterre, Ehlinger [55] | Doubtful | 4085 | Adequate | - EFA loadings NR | Very good | - α 0.89–0.56 | Yes | Reliability hypothesis testing | Doubtful | - Spearman’s r 0.88–0.54? KG |

| Clark, Sattler [71] | Doubtful | 520 | Adequate | - EFA loadings 0.79–0.47 | Very good | + α 0.94 | No | |||

| Duddle and Boughton [40] | Doubtful | 119 | Adequate | - EFA loadings 0.88–0.61 | Very good | + α 0.93–0.78 | No | |||

| Erickson, Duffy [56] | Inadequate | 849 | Adequate | - EFA loadings 0.87–0.31 | Very good | + α 0.88–0.78 | No | |||

| Erickson, Duffy [41] | Inadequate | 1550 (2x775) | Doubtful | ? EFA loadings 0.87–0.34 | Very good | + α 0.88–0.81 | No | |||

| Estabrooks, Squires [42] | OP | 752 | Adequate | - EFA loadings 0.86–0.34 | Very good | - α 0.91–0.54 | Yes | Hypothesis testing |

Very good | + OOM |

| Flint, Farrugia [43] | Inadequate | 195 (EFA) 938 (CFA) | Very good | - EFA loadings 0.95–0.38 CFA for each factor Range CFI 0.99–0.919 range RMSEA 0.08–0.06 |

Very good | + α 0.87–0.81 | No | |||

| Friedberg, Rodriguez [57] | Inadequate | 601 | Very good | + EFA and CFA loadings 0.95–0.38 CFI 0.97 RMSEA 0.04 |

Very good | + α 0.96–0.78 | No | |||

| Gagnon, Paquet [58] | Inadequate | 3142 | Very good | + CFA CFI 0.98 RMSEA 0.05 | Very good | - α 0.91–0.64 | Yes | Hypothesis testing |

Inadequate | ? KG |

| Ives-Erickson, Duffy [44] | Inadequate | 390 | Adequate | - EFA loadings 0.88–0.42 | Very good | + α 0.93–0.84 | No | |||

| Ives Erickson, Duffy [45] | Inadequate | 874 | Adequate | - EFA loadings 0.85–0.51 | Very good | + α 0.92–0.82 | No | |||

| Jansson von Vultée [59] | Inadequate | 435 | Inadequate | - NR | Inadequate | NR | No | |||

| Kalisch, Lee [46] | Doubtful | 1758 | Very good | - EFA and CFA: loadings 0.69–0.41; CFI 0.88 RMSEA 0.05 |

Very good | + α 0.85–0.74 | Yes | Reliability criterion validity hypothesis testing |

Doubtful very good Doubtful | + ICC2 > 0.84 + Pearson r 0.76 + KG |

| Kennerly, Yap [47] | Inadequate | 340 | Very good | - EFA and CFA: loadings 0.90–0.51; CFI 0.94 RMSEA 0.06 |

Very good | - α 0.93–0.60 | No | |||

| Klingle, Burgoon [60] | Inadequate | 1829 | Doubtful | - NR | Very good | ? α 0.87–0.81 | Yes | Hypothesis testing |

Doubtful | ? KG |

| Kobuse, Morishima [61] | Doubtful | 2924 | Adequate | - EFA loadings 0.87–0.28 | Very good | + α 0.82–0.75 | Yes | Hypothesis testing |

Inadequate | ? KG |

| Kramer and Schmalenberg [48] | Adequate | 3602 | Adequate | - EFA loadings 0.83–0.34 | Very good | - α 0.94–0.69 | Yes | Reliability hypothesis testing |

Doubtful very good |

? r range 0.88–0.53 + KG |

| Lake [49] | Inadequate | 2299 | Adequate | ? EFA loadings: 0.73–0.40; | Very good | + α 0.84–0.71 | Yes | Reliability hypothesis testing |

Inadequate very good |

+ ICC1 0.97–0.86 + KG |

| Li, Lake [50] | OP | 2000 | Adequate | - EFA loadings > 0.70 | Very good | + α 0.92–0.84 | No | |||

| Mays, Hrabe [51] | Inadequate | 210 | Adequate | - EFA loadings 0.87–0.57 | Doubtful | + α 0.89–0.75 | Yes | Hypothesis testing |

Doubtful | ? KG |

| McCusker, Dendukuri [62] | Inadequate | 121 | Adequate | - EFA loadings 0.79–0.40 | Very good | - α 0.88–0.64 | Yes | Hypothesis testing |

Adequate | ? OOM |

| McSherry and Pearce [63] | OP | 98 | Doubtful | - EFA loadings 0.92–0.17 | Doubtful | + α 0.78–0.71 | No | |||

| Pena-Suarez, Muniz [64] | Inadequate | 3163 | Very good | - EFA and CFA: loadings 0.77–0.41; CFI 0.85 RMSEA 0.06 | Doubtful | - α total scale 0.97 | Yes | Cross-cultural validity | Inadequate | - DIF NR |

| Rafferty, Philippou [65] | Adequate | 1705 | Adequate | - EFA loadings 0.87–0.40 | Very good | + α 0.93–0.70 | No | |||

| Reid, Courtney [52] | OP | 639 | Very good | - EFA and CFA: loadings 0.88–0.40; CFI 0.91 RMSEA 0.06 | Very good | - α 0.89–0.66 | Yes | Hypothesis testing |

Doubtful | ? KG |

| Saillour-Glenisson, Domecq [66] | Inadequate | 859 | Doubtful | - EFA and CFA: loadings, CFI and RMSEA NR | Very good | - α 0.91–0.53 | Yes | Reliability | Inadequate | - ICC range NR |

| Schroder, Medves [67] | Doubtful | 111 | Inadequate | - CFA for each factor range CFI 0.99–0.94 range RMSEA 0.13–0.04 | Very good | - α 0.89–0.67 | No | |||

| Siedlecki and Hixson [68] | Inadequate | 1332 | Adequate | - EFA loadings 0.91–0.71 | Very good | + α 0.89–0.73 | Yes | Hypothesis testing |

Inadequate | ? KG |

| Stahl, Schirmer [72] | Adequate | 1692 | Adequate | - EFA loadings 0.80–0.30 | Very good | - α 0.90–0.50 | Yes | Hypothesis testing |

Inadequate | ? OOM |

| Upenieks, Lee [69] | Doubtful | 464 | Very good | + CFA: CFI = 0.98 RSMEA 0.06 | Yes | Hypothesis testing |

Very good | ? OOM Pearson r 0.52–0.72 |

||

| Whitley and Putzier [53] | Inadequate | 245 | Inadequate | - NR | Very good | + α 0.87–0.72 | No | |||

| Wienand, Cinotti [70] | Doubtful | 8681 | Adequate | - EFA loadings 0.78–0.38 | Very good | + α 0.95–0.76 | Yes | Hypothesis testing |

Very good | ? KG |

NR: Not reported, KG: known groups, OOM: other outcome measurement, OP: other publication, LV: long version, SV: short version, EFA: exploratory factor analysis, CFA: confirmative factor analysis, CFI: comparative fit index, RMSEA: root-mean-square error of approximation, DIF: differential item functioning and ICC: intraclass correlation coefficient.

Discussion

The aim of this review was to assess WE instruments and learn which ones provide valid, reliable and succinct measures of health care professionals’ WE in hospitals. We identified 37 studies that report on the development and psychometric evaluation of an instrument measuring healthcare professionals’ experience of WE in hospitals. The number of instruments found, even using tight inclusion criteria, reflects the importance of the WE concept in the past 35 years. Despite new management structures, the greater focus on cost containment, and the change in focus from profession-centeredness to patient-centeredness have not influenced the importance of WE measurement [6, 73]. Especially rising attention for patient safety and high-performing organizations steered the importance of WE measurement. However, over the years, WE measurements have been made under different names, different elements and focus. Although elements did overlap, we could not identify one clear set to measure WE. Therefore, it is not possible to conclude which elements contribute more to the WE construct based on the assessment of the instruments. Additionally, most studies used a sample from the nursing domain, especially nurses [37, 38, 40, 46–51, 53, 55, 71], whereas a positive WE is team-based and teams in hospitals contain more than one profession, different educational levels and specialisms [14].

We found methodological flaws in most of the papers reporting the development of WE instruments. The most relevant shortcomings are the lack of information on scale development, failing to fully determine structural validity by confirmative factor analysis and failing to establish such psychometric properties as ‘reliability,’ ‘criterion validity,’ ‘hypothesis testing,’ ‘measurement error’ and ‘responsiveness.’ This made drawing firm conclusions on the validity and reliability of the 37 instruments included in this review hardly possible. Just five instruments scored ‘adequate’ or ‘very good’ on the COSMIN risk of bias checklist on all of the applied properties [42, 50, 54, 65, 72]. Of the five, only the short questionnaire for workplace analysis (KFZA) [54] and the CoCB [65] are both generally applicable and succinct, with an item total below the mean of this review. Both instruments are recent developments, which could suggest that scientists are paying more attention to the (reporting of) methodology of measurement instrument development.

Limitations

Some limitations of this study warrant consideration. First, to compare instrument content, the item and subscale descriptions of the individual instruments were mapped into 48 elements. Some details of instruments may possibly have been lost in the mapping process. Second, we sought original development and validation studies for this review, which may mean that other publications that discuss other psychometric properties of the included instruments were left out. Third, we searched for instruments intended to measure the WE in hospitals. Nevertheless, a large group of studies used samples from predominantly one discipline (e.g. nurses or nursing assistants [37, 38, 41–45, 51–53, 71]), and some instruments were developed specifically for one discipline (e.g. nursing [39, 40, 46, 48–50, 55]). Given that nurses are the largest professional group in hospitals, our search had to include measurement instruments for nursing. However, our assessment focused on instruments measuring WE in general and thus excluded instruments measuring a specific type of nursing or department.

Implications for research

To address methodological issues in the development process of instruments, it is important that instruments provide an understanding of the construct to be measured. Therefore, it is crucial that healthcare professionals participate actively in next phase. Clear definitions of items and categories would be helpful in creating distinct construct definitions and thus obtain a better understanding of what should be included in a WE measurement instrument to provide relevant, comprehensible and meaningful information [74, 75]. Some instruments found in this review already perform well, so we do not recommend developing new instruments. Rather, we advise scrutinizing the methodology of existing instruments using the COSMIN guidelines. For instance, we suggest performing confirmative factor analyses to check whether the data fit the proposed theoretical model for WE, and to determine the responsiveness of WE instruments in longitudinal research [32, 35].

Implications for practice

A positive healthcare WE is vital for high-performing healthcare organizations to provide good quality of care and retain a happy, healthy professional workforce [2, 6, 7, 76] so obtaining periodical insight into WE assessment on the team level is important [72]. Preferably, the WE instrument should facilitate teams and management to improve the WE, e.g. by deploying, monitoring and evaluating focused interventions. Besides taking valid, reliable measurements, the instrument should provide clearly relevant information for healthcare professionals [6, 77, 78]. Research shows that if an instrument provides information for use as a dialog tool, teams will become actively engaged in improving their WE [65]. Especially, the CoCB [65] is designed to do this.

Based on the assumption that instruments containing more than one construct measured with the same method are at risk of overrated validity [74, 75], the outcomes of the CoCB should always be used in combination with other managerial information, e.g. patient quality data or data on personnel sick leave and job satisfaction.

Conclusion

The findings of this systematic review have potential value in guiding researchers, healthcare managers and human resource professionals to select an appropriate and psychometrically robust instrument to measure WE. We have demonstrated content diversity and methodological problems in most of the currently available instruments, highlighting opportunities for future research. Based on our findings, we draw the cautious conclusion that more recently developed instruments, such as the CoCB [65], seem to fit current reporting demands for healthcare teams. However, we suggest investing in improving their psychometrical quality.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Wichor M. Bramer, information specialist, Medical Library, Erasmus MC University Medical Center, Rotterdam, The Netherlands, for his assistance on the systematic search of literature.

Contributor Information

Susanne M Maassen, Department of Quality & Patient Care, Erasmus MC University Medical Center, Rotterdam, The Netherlands.

Anne Marie J W Weggelaar Jansen, Department of Health Services Management & Organization, Erasmus School of Health Policy & Management, Erasmus University Rotterdam, Burgemeester Oudlaan 50 (Bayle Building) Postbus 1738, 3000 DR Rotterdam, The Netherlands.

Gerard Brekelmans, Department of Quality & Patient Care, Erasmus MC University Medical Center, Rotterdam, The Netherlands.

Hester Vermeulen, Departement of IQ Healthcare, Radboud Institute of Health Sciences, Scientific Center for Quality of Healthcare, Geert Grooteplein 21 (route 114) Postbus 9101, 6500 HB, NIjmegen, The Netherlands; Departement of Faculty of Health and Social studies, Hogeschool of Arnhem and Nijmegen (HAN) University of Applied Sciences, Kapittelweg 33, Postbus 6960, 6503 GL Nijmegen, The Netherlands.

Catharina J van Oostveen, Department of Health Services Management & Organization, Erasmus School of Health Policy & Management, Erasmus University Rotterdam, Burgemeester Oudlaan 50 (Bayle Building) Postbus 1738, 3000 DR Rotterdam, The Netherlands; Department of Wetenschapsbureau, Spaarnegasthuis Academie, Spaarne Gasthuis, Spaarnepoort 1, Postbus 770, 2130 AT Hoofddorp, The Netherlands.

Author contributions

S.M., A.M.W., C.O. and H.V. were responsible for the conception and design of the study; S.M., A.M.W., C.O. and G.B. were responsible for collection, analysis and interpretation of the data; S.M., A.M. and C.O. wrote the article; S.M., A.M.W. and C.O. had primary responsibility for final content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The research was funded by the Citrien Fonds of ZonMW (grant 8392010042) and conducted on behalf of the Dutch Federation of University Medical Centers’ Quality Steering program.

Conflict of Interest statement

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval for this study is not necessary under Dutch law as no patient data were collected.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and material

Not applicable.

References

- [1]. Aiken LH, Sermeus W, Van den Heede K et al. Patient safety, satisfaction, and quality of hospital care: cross sectional surveys of nurses and patients in 12 countries in Europe and the United States. BMJ 2012;344:e1717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2]. Braithwaite J, Herkes J, Ludlow K et al. Association between organisational and workplace cultures, and patient outcomes: systematic review. BMJ Open 2017;7:e017708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3]. Stalpers D, de Brouwer BJ, Kaljouw MJ, Schuurmans MJ. Associations between characteristics of the nurse work environment and five nurse-sensitive patient outcomes in hospitals: a systematic review of literature. Int J Nurs Stud 2015;52:817–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4]. Lasater KB, McHugh MD. Nurse staffing and the work environment linked to readmissions among older adults following elective total hip and knee replacement. Int J Qual Health Care 2016;28:253–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5]. Sutcliffe KM. High reliability organizations (HROs). Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol 2011;25:133–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6]. Taylor N, Clay-Williams R, Hogden E et al. High performing hospitals: a qualitative systematic review of associated factors and practical strategies for improvement. BMC Health Serv Res 2015;15:244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7]. Aronsson G, Theorell T, Grape T et al. A systematic review including meta-analysis of work environment and burnout symptoms. BMC Public Health 2017;17:264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8]. Kutney-Lee A, Wu ES, Sloane DM, Aiken LH. Changes in hospital nurse work environments and nurse job outcomes: an analysis of panel data. Int J Nurs Stud 2013;50:195–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9]. Van Bogaert P, Peremans L, Van Heusden D et al. Predictors of burnout, work engagement and nurse reported job outcomes and quality of care: a mixed method study. BMC Nurs 2017;16:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10]. Aiken LH, Sloane DM, Clarke S et al. Importance of work environments on hospital outcomes in nine countries. Int J Qual Health C 2011;23:357–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11]. Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE et al. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci 2009;4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12]. RNAoO Workplace Health, Safety and Well-being of the Nurse. Toronto, Canada: Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario, 2008, 1–100. [Google Scholar]

- [13]. Pearson A, Laschinger H, Porritt K et al. Comprehensive systematic review of evidence on developing and sustaining nursing leadership that fosters a healthy work environment in healthcare. Int J Evid Based Healthc 2007;5:208–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14]. Schmutz JB, Meier LL, Manser T. How effective is teamwork really? The relationship between teamwork and performance in healthcare teams: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2019;9:e028280. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-028280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15]. Baumann A. for the International Council of Nurses, Positive Practice Environments: quality workplaces = quality patient care. Information and action tool kit. ICN - International Council of Nurses, 2007 Geneva (Switzerland) ISBN: 92-95040-80-5 retrevied from: https://www.caccn.ca/files/ind_kit_final2007.pdf.

- [16]. Abbenbroek B, Duffield C, Elliott D. Selection of an instrument to evaluate the organizational environment of nurses working in intensive care: an integrative review. J Hosp Admin 2014;3:20. [Google Scholar]

- [17]. Norman RM, Sjetne IS. Measuring nurses’ perception of work environment: a scoping review of questionnaires. BMC Nurs 2017;16:66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18]. Swiger PA, Patrician PA, Miltner RSS et al. The practice environment scale of the nursing work index: an updated review and recommendations for use. Int J Nurs Stud 2017;74:76–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19]. Arnetz BB. Physicians’ view of their work environment and organisation. Psychother Psychosom 1997;66:155–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20]. Kralewski J, Dowd BE, Kaissi A et al. Measuring the culture of medical group practices. Health Care Manag Rev 2005;30:184–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21]. Martowirono K, Wagner C, Bijnen AB. Surgical residents’ perceptions of patient safety climate in Dutch teaching hospitals. J Eval Clin Pract 2014;20:121–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22]. Huddleston P, Mancini ME, Gray J. Measuring nurse Leaders’ and direct care Nurses’ perceptions of a healthy work environment in acute care settings, part 3: healthy work environment scales for nurse leaders and direct care nurses. J Nurs Adm 2017;47:140–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23]. Warshawsky NE, Rayens MK, Lake SW, Havens DS. The nurse manager practice environment scale: development and psychometric testing. J Nurs Adm 2013;43:250–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24]. Choi J, Bakken S, Larson E et al. Perceived nursing work environment of critical care nurses. Nurs Res 2004;53:370–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25]. Bradley EH, Brewster AL, Fosburgh H et al. Development and psychometric properties of a scale to measure hospital organizational culture for cardiovascular care. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2017;10:e003422. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.116.003422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26]. Flarey DL. The social climate scale: a tool for organizational change and development. J Nurs Adm 1991;21:37–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27]. Helfrich CD, Li YF, Mohr DC et al. Assessing an organizational culture instrument based on the competing values framework: exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses. Implement Sci 2007;2:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28]. Heritage B, Pollock C, Roberts L. Validation of the organizational culture assessment instrument. PLoS One 2014;9:e92879. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29]. Scott T, Mannion R, Davies H, Marshall M. The quantitative measurement of organizational culture in health care: a review of the available instruments. Health Serv Res 2003;38:923–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30]. Gershon RRM, Stone PW, Bakken S. Measurement of organizational culture and climate in healthcare. J Nurs 2004;34:33–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31]. Gagliardi AR, Dobrow MJ, Wright FC. How can we improve cancer care? A review of interprofessional collaboration models and their use in clinical management. Surg Oncol 2011;20:146–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32]. Mokkink LB, Vet HCW, Prinsen CAC et al. COSMIN risk of bias checklist for systematic reviews of patient-reported outcome measures. Qual Life Res 2018;27:1171–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33]. Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Knol DL et al. The COSMIN checklist for evaluating the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties: a clarification of its content. BMC Med Res Methodol 2010;10:22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34]. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35]. Prinsen CAC, Mokkink LB, Bouter LM et al. COSMIN guideline for systematic reviews of patient-reported outcome measures. Qual Life Res 2018;27:1147–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36]. Abraham IL, Foley TS. The work environment scale and the Ward atmosphere scale (short forms): psychometric data. Percept Mot Skills 1984;58:319–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37]. Adams A, Bond S, Arber S. Development and validation of scales to measure organisational features of acute hospital wards. Int J Nurs Stud 1995;32:612–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38]. Aiken LH, Patrician PA. Measuring organizational traits of hospitals: the revised nursing work index. Nurs Res 2000;49:146–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39]. Berndt AE, Parsons ML, Paper B, Browne JA. Preliminary evaluation of the healthy workplace index. Crit Care Nurs Q 2009;32:335–44. [Google Scholar]

- [40]. Duddle M, Boughton M. Development and psychometric testing of the nursing workplace relational environment scale (NWRES). J Clin Nurs 2009;18:902–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41]. Erickson JI, Duffy ME, Ditomassi M, Jones D. Psychometric evaluation of the revised professional practice environment (RPPE) scale. J Nurs Adm 2009;39:236–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42]. Estabrooks CA, Squires JE, Cummings GG et al. Development and assessment of the Alberta context tool. BMC Health Serv Res 2009;9:234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43]. Flint A, Farrugia C, Courtney M, Webster J. Psychometric analysis of the Brisbane practice environment measure (B-PEM). J Nurs Scholarsh 2010;42:76–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44]. Ives-Erickson J, Duffy ME, Jones DA. Development and psychometric evaluation of the patient care associates’ work environment scale. J Nurs Adm 2015;45:139–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45]. Ives Erickson J, Duffy ME, Ditomassi M, Jones D. Development and psychometric evaluation of the professional practice work environment inventory. J Nurs Adm 2017;47:259–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46]. Kalisch BJ, Lee H, Salas E. The development and testing of the nursing teamwork survey. Nurs Res 2010;59:42–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47]. Kennerly SM, Yap TL, Hemmings A et al. Development and psychometric testing of the nursing culture assessment tool. Clin Nurs Res 2012;21:467–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48]. Kramer M, Schmalenberg C. Development and evaluation essentials of magnetism tool. J Nurs Adm 2004;34:365–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49]. Lake ET. Development of the practice environment scale of the nursing work index. Res Nurs Health 2002;25:176–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50]. Li YF, Lake ET, Sales AE et al. Measuring nurses’ practice environments with the revised nursing work index: evidence from registered nurses in the veterans health administration. Res Nurs Health 2007;30:31–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51]. Mays MZ, Hrabe DP, Stevens CJ. Reliability and validity of an instrument assessing nurses’ attitudes about healthy work environments in hospitals. J Nurs Manag 2010;19:18–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52]. Reid C, Courtney M, Anderson D, Hurst C. Testing the psychometric properties of the Brisbane practice environment measure using exploratory factor analysis and confirmatory factor analysis in an Australian registered nurse population. Int J Nurs Pract 2015;21:94–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53]. Whitley MP, Putzier DJ. Measuring nurses’ satisfaction with the quality of their work and work environment. J Nurs Care Qual 1994;8:43–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54]. Appel P, Schuler M, Vogel H et al. Short questionnaire for workplace analysis (KFZA): factorial validation in physicians and nurses working in hospital settings. J Occup Med Toxicol 2017;12:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55]. Bonneterre V, Ehlinger V, Balducci F et al. Validation of an instrument for measuring psychosocial and organisational work constraints detrimental to health among hospital workers: the NWI-EO questionnaire. Int J Nurs Stud 2011;48:557–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56]. Erickson JI, Duffy ME, Gibbons MP et al. Development and psychometric evaluation of the professional practice environment (PPE) scale. J Nurs Scholarsh 2004;36:279–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57]. Friedberg MW, Rodriguez HP, Martsolf GR et al. Measuring workplace climate in community clinics and health centers. Med Care 2016;54:944–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58]. Gagnon S, Paquet M, Courcy F, Parker CP. Measurement and management of work climate: cross-validation of the CRISO psychological climate questionnaire. Healthc Manage Forum 2009;22:57–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59]. Jansson von Vultée PH. Healthy work environment--a challenge? Int J Health Care Qual Assur 2015;28:660–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60]. Klingle RS, Burgoon M, Afifi W, Callister M. Rethinking how to measure organizational culture in the hospital setting: the hospital culture scale. Eval Health Prof 1995;18:166–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61]. Kobuse H, Morishima T, Tanaka M et al. Visualizing variations in organizational safety culture across an inter-hospital multifaceted workforce. J Eval Clin Pract 2014;20:273–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62]. McCusker J, Dendukuri N, Cardinal L et al. Assessment of the work environment of multidisciplinary hospital staff. Int J Health Care Qual Assur 2005;18:543–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63]. McSherry R, Pearce P. Measuring health care workers’ perceptions of what constitutes a compassionate organisation culture and working environment: findings from a quantitative feasibility survey. J Nurs Manag 2018;26:127–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64]. Pena-Suarez E, Muniz J, Campillo-Alvarez A et al. Assessing organizational climate: psychometric properties of the CLIOR scale. Psicothema 2013;25:137–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65]. Rafferty AM, Philippou J, Fitzpatrick JM et al. Development and testing of the ‘Culture of care Barometer’ (CoCB) in healthcare organisations: a mixed methods study. BMJ Open 2017;7:e016677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66]. Saillour-Glenisson F, Domecq S, Kret M et al. Design and validation of a questionnaire to assess organizational culture in French hospital wards. BMC Health Serv Res 2016;16:491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67]. Schroder C, Medves J, Paterson M et al. Development and pilot testing of the collaborative practice assessment tool. J Interprof Care 2011;25:189–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68]. Siedlecki SL, Hixson ED. Development and psychometric exploration of the professional practice environment assessment scale. J Nurs Scholarsh 2011;43:421–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69]. Upenieks VV, Lee EA, Flanagan ME, Doebbeling BN. Healthcare team vitality instrument (HTVI): developing a tool assessing healthcare team functioning. J Adv Nurs 2010;66:168–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70]. Wienand U, Cinotti R, Nicoli A, Bisagni M. Evaluating the organisational climate in Italian public healthcare institutions by means of a questionnaire. BMC Health Serv Res 2007;7:73. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-7-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71]. Clark CM, Sattler VP, Barbosa-Leiker C. Development and testing of the healthy work environment inventory: a reliable tool for assessing work environment health and satisfaction. J Nurs Educ 2016;55:555–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72]. Stahl K, Schirmer C, Kaiser L. Adaption and validation of the picker employee questionnaire with hospital midwives. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2017;46:e105–e17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73]. Rathert C, Ishqaidef G, May DR. Improving work environments in health care: test of a theoretical framework. Health Care Manag Rev 2009;34:334–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74]. Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Podsakoff NP. Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu Rev Psychol 2012;63:539–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75]. Terwee CB, Prinsen CAC, Chiarotto A et al. COSMIN methodology for evaluating the content validity of patient-reported outcome measures: a Delphi study. Qual Life Res 2018;27:1159–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76]. Van Bogaert P, Timmermans O, Weeks SM et al. Nursing unit teams matter: impact of unit-level nurse practice environment, nurse work characteristics, and burnout on nurse reported job outcomes, and quality of care, and patient adverse events--a cross-sectional survey. Int J Nurs Stud 2014;51:1123–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77]. Rosen MA, DiazGranados D, Dietz AS et al. Teamwork in healthcare: key discoveries enabling safer, high-quality care. Am Psychol 2018;73:433–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78]. Oerlemans AJM, De Jonge E, Van der Hoeven JG, Zegers M. A systematic approach to develop a core set of parameters for boards of directors to govern quality of care in the ICU. Int J Qual Health C 2018;30:545–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.