Abstract

Purpose:

The purpose of this study was to determine the outcomes of meniscus repair in the adolescent population, including: 1) failure and reoperation rates, 2) clinical and functional results, and 3) activity-related outcomes including return to sport.

Methods:

Two authors independently searched MEDLINE, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials & Cochrane Library, and CINHAL databases for literature related to meniscus repair in an adolescent population according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. No meta-analysis was performed in this qualitative systematic review.

Results:

Thirteen studies, including no Level I, one Level II, one Level III, and eleven Level IV studies yielded 466 patients with 503 meniscus repairs. All defined meniscal re-tear as a primary endpoint, with a reported failure rate ranging from 0–42% at a follow-up ranging from 22–211 months. There were a total of 93 failed repairs. IKDC scores were reported in four studies with a mean improvement ranging from 24–42 (P<0.001). Mean post-operative Lysholm scores were reported in seven studies, ranging from 85–96. Additionally, four of those studies provided mean pre-operative Lysholm scores, ranging from 56–79, with statistically significant mean score improvements ranging from 17–31. Mean post-operative Tegner Activity scores were reported in nine studies, with mean values ranging from 6.2–8.

Conclusion:

This systematic review demonstrates that both subjective and clinical outcomes, including failure rate, Lysholm, IKDC, and Tegner activity scale scores, are good to excellent following meniscal repair in the adolescent population. Further investigations should aim to isolate tear type, location, surgical technique, concomitant procedures, and rehabilitation protocols to overall rate of failure and clinical and functional outcomes.

Keywords: meniscus, repair, pediatric, adolescent, revision, meniscus repair, meniscus tear

Introduction:

Historically, meniscus tears were treated with meniscectomy to improve symptoms associated with meniscus pathology such as locking, catching and pain. Outcomes demonstrating meniscus repair as a protective factor against OA are prevalent in the literature [8, 22, 32, 52]. The abundance of literature demonstrating the association between meniscectomy and osteoarthritis (OA) has resulted in an increased emphasis on meniscal repair, especially in the younger population where meniscal tear incidence is increasing [15, 32, 52].

In the adult population, there is evidence to support the success of meniscus repair at mid and long-term follow-up [8, 22, 32, 40, 52]. A recent systematic review of partial meniscectomy versus meniscal repair demonstrated more re operations for meniscal repairs but better long term outcomes [44]. Outcome data following surgical management of these injuries in an adolescent population on the other hand is relatively sparse. Incidence of these injuries remain lower than the adult population. However, they may be increasing due to more sports participation and sports related knee injuries, physician awareness, advanced imaging, and novel meniscus repair techniques [15, 50]. Therefore, the current environment presents a need for a thorough and updated understanding of published meniscus repair outcomes in these adolescent patients.

The purpose of the study was to determine the outcomes of meniscus repair in the adolescent population, including: 1) failure, as defined by need for revision surgery, and reoperation rates, 2) clinical and functional results, and 3) activity-related outcomes including return to sport. The authors hypothesized that meniscus repair in the adolescent population will yield good survivorship, excellent clinical and functional results while supporting a return to sport in our athletes.

Materials and Methods:

Literature Search

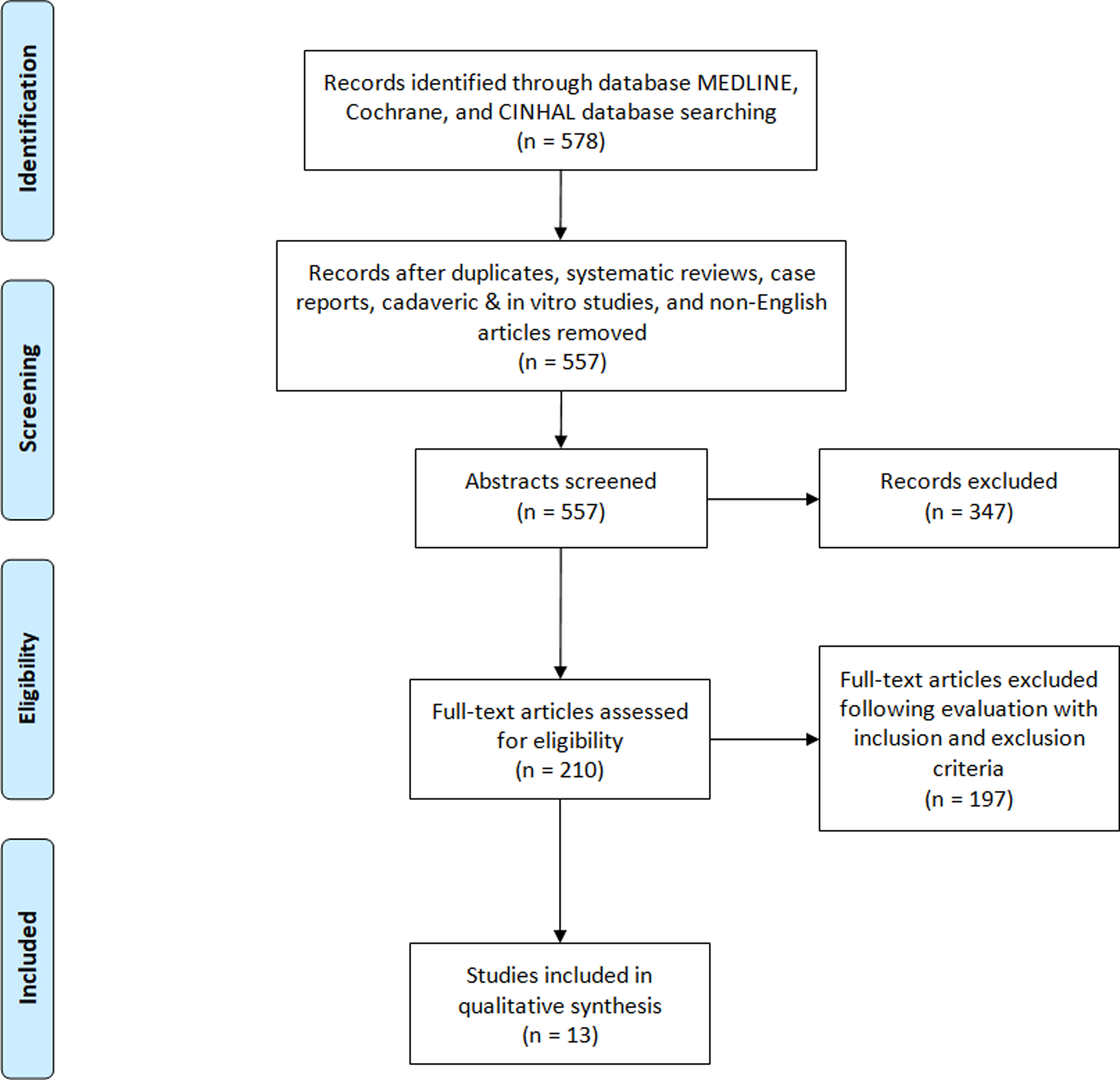

A comprehensive search of the literature following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines was conducted on November 19th, 2019 (Figure 1) [37]. The searched databases included MEDLINE, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials & Cochrane Library, and CINHAL (Cumulative Index for Nursing and Allied Health Literature). No date search period parameters were set and a Boolean algebra search strategy was utilized as follows: (Pediatric OR children OR adolescent OR “skeletally immature”) AND (Meniscus AND Repair). Articles were catalogued using Microsoft Excel (2010; Microsoft Corp, Redmond, WA).. Duplicate articles, systematic reviews, case reports, cadaveric & in vitro studies, and non-English articles were eliminated. Abstracts of these studies were then manually reviewed by two independent authors (AJT & NIK) and only studies eliminated in consensus were removed from the list. Full texts were retrieved and manually reviewed for inclusion. Following the systematic search, reference lists and prior studies were reviewed for missed inclusions.

Figure 1 –

Flow diagram of the literature database search performed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines. Thirteen studies were ultimately included in this qualitative synthesis.

Inclusion Criteria:

Studies investigating patients who underwent meniscus repair aged 19 or younger.

Studies reporting a form of outcomes measures and a report re-tear or recurrent surgical procedures specifically regarding patients aged 19 or younger.

Exclusion Criteria:

Studies reporting on Discoid Meniscus treatment without an acute tear which was repaired.

Studies reporting on patients who underwent isolated meniscectomy.

Studies which were case reports or reports on less than 10 patients.

Reviews, Meta-Analysis, abstracts, expert opinions, Level V studies, cadaveric (or in vitro) studies, and studies with unavailable full English texts.

Studies reporting on a population mean of less than 22 months of clinical follow-up.

Studies in which all patients were managed before Jan 1, 1995.

Thirteen studies were identified and analyzed after applying these criteria (Table 1). Articles in question were deliberated upon by the senior authors until consensus decision was reached.

Table 1:

Characteristics of Included Studies (n=13)

| Study | Study Design/Level of Evidence | No. of Patients | No. of Total repairs | Mean Follow-up (months) | Year of Publication | MINORS Score, % | Mean Age, range (years) | Patient Reported Outcome Scores |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accadbled et al. (2007) [1] | Case Series/IV | 12 | 12 | 37 | 2007 | 56% | 13 (8–16) | Lysholm, IKDC, Tegner Activity scores |

| Ahn et al. (2008) [3] | Case Series/IV | 23 | 28 | 51 | 2008 | 88% | 9 (4–15) | Lysholm, HSS scores |

| Hagmeijer et al. (2019) [17] | Case Series/IV | 32 | 33 | 211 | 2019 | 81% | 16.1 (9.9–18.7) | IKDC, Tegner Activity scores |

| Kraus et al. (2012) [25] | Case Series/IV | 25 | 29 | 28 | 2012 | 69% | 15 (4–17) | Lysholm, Tegner Activity scores |

| Krych et al. (2008) [26] | Case Series/IV | 44 | 45 | 70 | 2008 | 81% | 15.8 (9.9–18.7) | IKDC, Tegner Activity scores |

| Krych et al. (2010) [27] | Case Series/IV | 99 | 99 | 96 | 2010 | 81% | 16 (13–18) | IKDC, Tegner Activity scores |

| Lucas et al. (2015)[31] | Case Series/IV | 17 | 19 | 22 | 2015 | 81% | 14 (9–18) | Lysholm, Tegner Activity scores |

| Mintzer et al. (1998) [36] | Case Series/IV | 26 | 29 | 60 | 1998 | 88% | 15.3 (11–17) | Lysholm, IKDC, SF-36 scores |

| Noyes et al. (2002) [41] | Prospective Cohort Study/II | 58 | 71 | 51 | 2002 | 88% | 16 (9–19) | Cincinnati Knee score |

| Schmitt et al. (2016) [47] | Retros pective Cohort Study/IV | 19 | 19 | 72 | 2016 | 81% | 14.8 (9.1–16.3) | Lysholm, IKDC, KOOS, Tegner Activity scores |

| Tagliero et al. (2018)[53] | Case Series/IV | 47 | 47 | 199 | 2018 | 75% | 16 | IKDC, Tegner Activity scores |

| Vanderhave et al. (2011)[54] | Retros pective Cohort Study/I II | 45 | 53 | 27 | 2011 | 69% | 13.2 (9–17) | IKDC, Tegner Activity scores |

| Yoo et al. (2015) [57] | Case Series/IV | 19 | 19 | 56 | 2015 | 69% | 10.7 (3.1–17. 5) | Lysholm score |

Risk of Bias Assessment

Each study was evaluated using the Methodological Index for Non-randomized Studies (MINORS) scoring system [51]. MINORS is a validated instrument for assessing the methodological quality of studies and is scored on a scale of 0–16 for non-comparative studies (8 item checklist scored from 0–2) and 0–24 for comparative studies (12 item checklist scored from 0–2) where higher scores represent lower levels of bias. Each study was independently scored by two of the authors and any disagreements were resolved by discussion until consensus was reached. All scores were converted to percentages for normalization purposes and displayed in Table 1. Level of Evidence was determined using The Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine and results are shown in Table 1.

Data Extraction and Statistical Analysis

The data of interest from each article was thoroughly reviewed by the senior authors. Year of Publication, level of evidence, population sizes, patient demographics, IKDC, Lysholm, Tegner, HSS Score, return to sport time, complications, tear sub-types, meniscus tear location (medial vs. Lateral), mean time to failure, and failure rates were recorded. Pooling of results was not conducted in the form of weighted averages for outcomes score due to inadequate numbers of comparative studies and bias heterogeneity, subjective analysis was conducted for these variables instead.

The pre and post-operative IKDC, Lysholm, and Tegner scores were reported when available. The study was excluded from the specific figure if outcome data was not described. Measures of dispersion, including standard deviation and range were included when provided. KOOS, HSS, and Cincinnati Knee values were each reported in one instance, but these singular data points were omitted from the reported range of scores. All data were analyzed using Excel (2010; Microsoft Corp, Redmond, WA) and JMP Pro software (version 14.1.0, SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC). Forest plots were created using JMP Pro and 95% confidence intervals were calculated for rate of failure according to the adjusted Wald method [2]. When not stated explicitly, pre and post means and standard deviations were estimated with given data parameters (confidence intervals, P values) as mentioned in the Cochrane Handbook for heterogeneity calculations [20].

Results:

The initial search yielded 18 articles from the Cochrane Library, 74 articles from CINHAL, and 578 articles from MEDLINE. Duplicate articles, systematic reviews, case reports, cadaveric & in vitro studies, and non-English articles were eliminated resulting 557 remaining titles. Abstracts of these 557 studies were then manually reviewed by two independent authors and only studies eliminated in consensus were removed from the list. As a result, 210 full texts were retrieved and manually reviewed for inclusion. Thirteen studies published between 1998 and 2019 were ultimately included in this review and individual study characteristics are reported in Table 1 [1, 3, 17, 25–27, 31, 36, 41, 47, 53, 54, 57]. The majority were retrospective case series (10), two were retrospective cohort studies, and one was a prospective cohort. There were no Level I studies, one Level II study, one Level III study, and eleven Level IV studies. MINORs scores ranged from 56% to 88% and the majority (11 of 13) were best classified as Level of Evidence IV studies. These 13 studies yielded 503 meniscus repairs in 466 patients age 19 or younger who were defined as adolescent populations by the authors. The overall average age of this cohort is 14.5 nd ranged from 3–19 years of age. This included 200 isolated medial meniscus repairs, 233 isolated lateral meniscus repairs and 49 combined (92) medial and lateral meniscus repairs. Twelve studies had a mean follow-up greater than 24 months and one study had a mean follow up of 22 months. The average postoperative follow-up time ranged from 22–211 months.

Meniscus tears were characterized into simple (longitudinal, radial, or horizontal), bucket handle, or complex (multiplanar) in eight studies (Table 2). This included 212 simple (50%), 118 bucket handle (28%), and 93 complex tears (22%). A subset of patients undergoing meniscus repair also underwent concomitant surgical procedures in 10 studies. Concomitant central meniscectomy for discoid meniscus was performed in two studies [3, 57]. Concomitant ACL Reconstruction was undertaken by all 99 patients in one study [27], and all 47 patients in another study[53]. Seven studies reported some patients with no concomitant procedures (125 patients) and some with concomitant ACL reconstructions (116 patients) [1, 25, 36, 41, 47, 54]. Only three studies reported on patients with an isolated meniscal repair [17, 26, 31].

Table 2:

Characterization of Meniscus Tears and Repairs

| No. of Patients | No. of Total Repairs | No. of Isolated MMR | No. of Isolated LMR | No. of M+L MR | No. of Simple Tears | No. of Bucket Handle Tears | No. of Complex Tears | No. of Patients w/ ACLR | No. of Patients w/ CM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accadbled et al. (2007 | 12 | 12 | 4 | 8 | 0 | 6 | 6 | NR | 3 | 0 |

| Ahn et al. (2008) | 23 | 28 | 0 | 28 | 0 | NR | NR | NR | 0 | 28 |

| Hagmeijer et al. (2019) | 32 | 33 | 16 | 17 | 0 | 11 | 17 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Kraus et al. (2012) | 25 | 29 | 15 | 6 | 4 | 9 | 19 | 1 | 13 | 0 |

| Krych et al. (2008) | 44 | 45 | 25 | 20 | 0 | 15 | 22 | 8 | 0 | 0 |

| Krych et al. (2010) | 99 | 99 | 48 | 26 | 25 | 61 | 17 | 21 | 99 | 0 |

| Lucas et al. (2015) | 17 | 19 | 10 | 9 | 0 | 12 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Mintzer et al. (1998) | 26 | 29 | 9 | 14 | 3 | NR | NR | NR | 15 | 0 |

| Noyes et al. (2002) | 58 | 71 | 30 | 21 | 10 | 44 | NR | 27 | 43 | 0 |

| Schmitt et al. (2016) | 19 | 19 | 5 | 14 | 0 | 10 | 9 | NR | 11 | 0 |

| Tagliero et al. (2018) | 47 | 47 | 30 | 14 | 3 | 28 | 9 | 10 | 47 | 0 |

| Vanderhave et al. (2011) | 45 | 53 | 17 | 28 | 4 | 16 | 15 | 18 | 31 | 0 |

| Yoo et al. (2015) | 19 | 19 | 0 | 19 | 0 | NR | NR | NR | 0 | 19 |

M+L MR: Combined Medial and Lateral Meniscus Repairs; ACLR: Concomitant Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction; CM: Concomitant Central Meniscectomy; LMR: Lateral Meniscus Repairs; MMR: Medial Meniscus Repairs; NR: Not Reported

Reoperations and failures

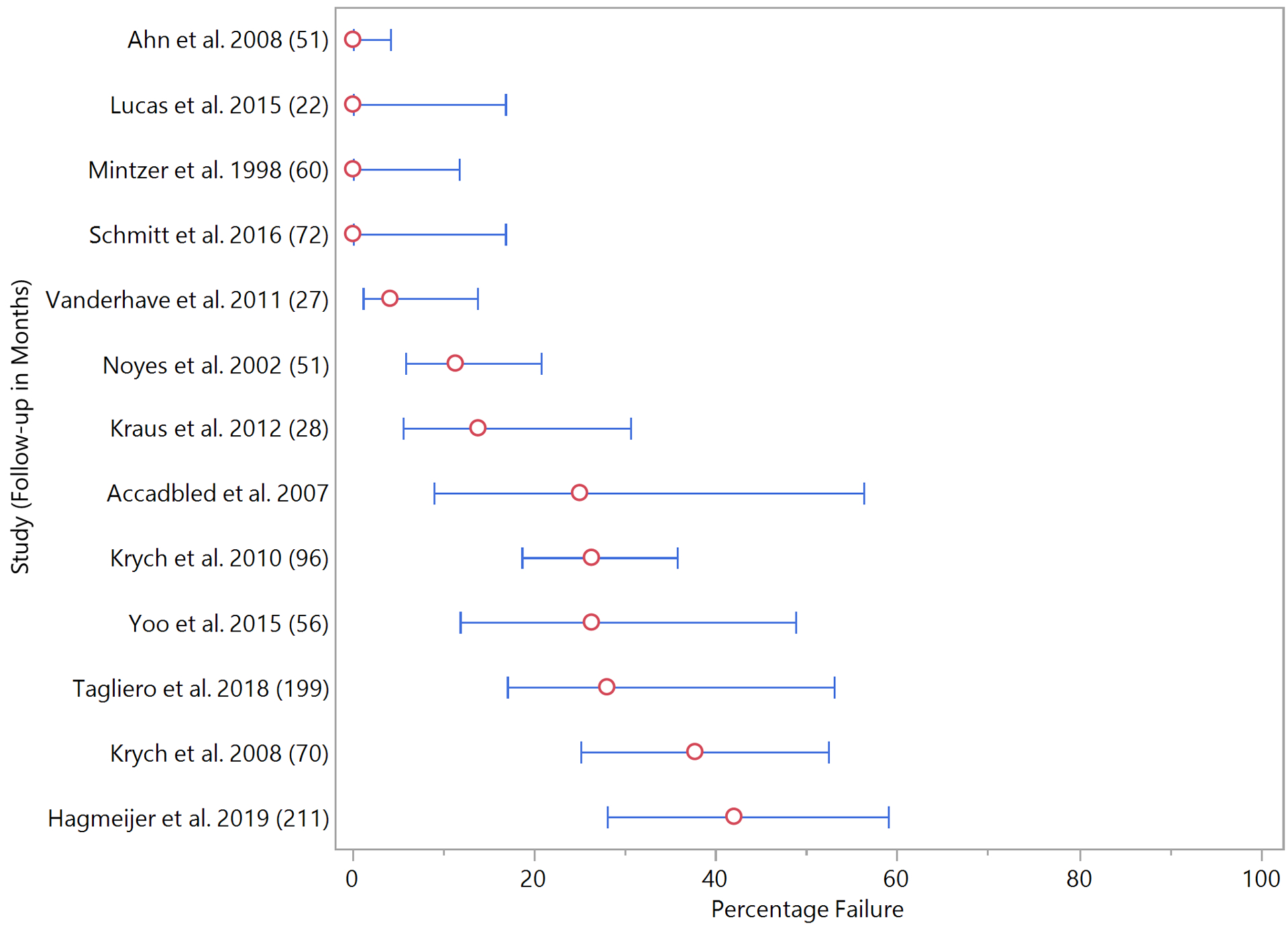

All studies reported on meniscus re-tear as a primary endpoint, with a reported failure rate ranging from 0–42% (Figure 2). Failure in this cohort was defined as the need for re-operation. There were a total of 93 failed repairs. Mean time to failure of primary repair, reported as symptoms requiring repeat surgical intervention with evidence of meniscal injury, was reported in seven studies and ranged from 15–45.6 months (Table 3). Failure was further sub-divided into failures by tear type in six studies. Failure rates ranged from 14–25% in simple meniscal repairs, 11–47% in the studies reporting on bucket handle repairs and 26–88% in the studies reporting on complex tears. Failure was defined in all of these studies as reoperation [25–27], medial meniscal tears were a noted risk factor for failure in only one of the three studies [27], medial meniscal tears were noted to demonstrate a higher but nonsignificant rate of failure in one study [26], and to demonstrate equivalent outcomes in the final study [25].

Figure 2 – Percentage Failure (Re-Tear).

Each study is listed along with the follow-up period (months). Red circles represent the percentage rate of failure (re-tear) for the included studies. The 95% confidence intervals (thin blue line with bars) were calculated utilizing the adjusted Wald method for measure of dispersion.[2]

Table 3:

Outcomes, Failures, and Reoperations

| Study | No. of Total Repairs | Mean Lysholm Scores | Mean IKDC Scores | Mean Tegner Scores | Mean RTS (months) | Failure Rate (Meniscus Reoperation) | Failure Rate (Imaging) | Clinical Failure Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accadbled et al. (2007) | 12 | 65 to 96 (P=.002) | NR | 6.9 to 6.6 (P=0.14) | NR | 25% | 66% | 25% |

| Ahn et al. (2008) | 28 | 79 to 96 (P<.001) | NR | NR | NR | 0% | NR | NR |

| Hagmeijer et al. (2019) | 33 | NR | 65–92 | 8.3 to 6.5 | NR | 42% | NR | 42% |

| Kraus et al. (2012) | 29 | Post-op: 95 | NR | 7.6 to 7.2 (NS) | 6 | 14% | NR | NR |

| Krych et al. (2008) | 45 | NR | 65 to 89 (P<.001) | Post-op: 8 | 5.2 | 38% | NR | 38% |

| Krych et al. (2010) | 99 | NR | 48 to 90 (P<.001) | 1.9 to 6.2 (P<.001) | 6–9 | 26% | NR | 26% |

| Lucas et al. (2015) | 19 | 56 to 85 (P<.001) | NR | 3.9 to 7.1 (P<.001) | NR | 0% | 26% | 11% |

| Mintzer et al. (1998) | 29 | Post-op: 90 | NR | NR | NR | 0% | NR | 0% |

| Noyes et al. (2002) | 71 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 18% | NR | 20% |

| Schmitt et al. (2016) | 19 | Post-op: 96 | Post-op: 91 | 7.6 to 7.3 | NR | 11% | NR | 11% |

| Tagliero et al. (2018) | 47 | NR | 48–88 | 1.9 to 6.3 | NR | 28% | NR | 28% |

| Vanderhave et al. (2011) | 53 | NR | NR | Post-op: 8 – 6.8 w/ACLR - 8 w/o ACLR (P=0.017) | 6.5 – 5.6 w/o ACLR - 8.2 w/ACLR | 4% | NR | 4% |

| Yoo et al. (2015) | 19 | 66 to 91 (P<.001) | NR | NR | NR | 0% | NR | NR |

ACLR: concomitant Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction; N/A: Not Applicable; NR: Not Reported; NS: Not Significant (P ≥ 0.05); RTS: Return to Sport

Clinical and functional outcomes

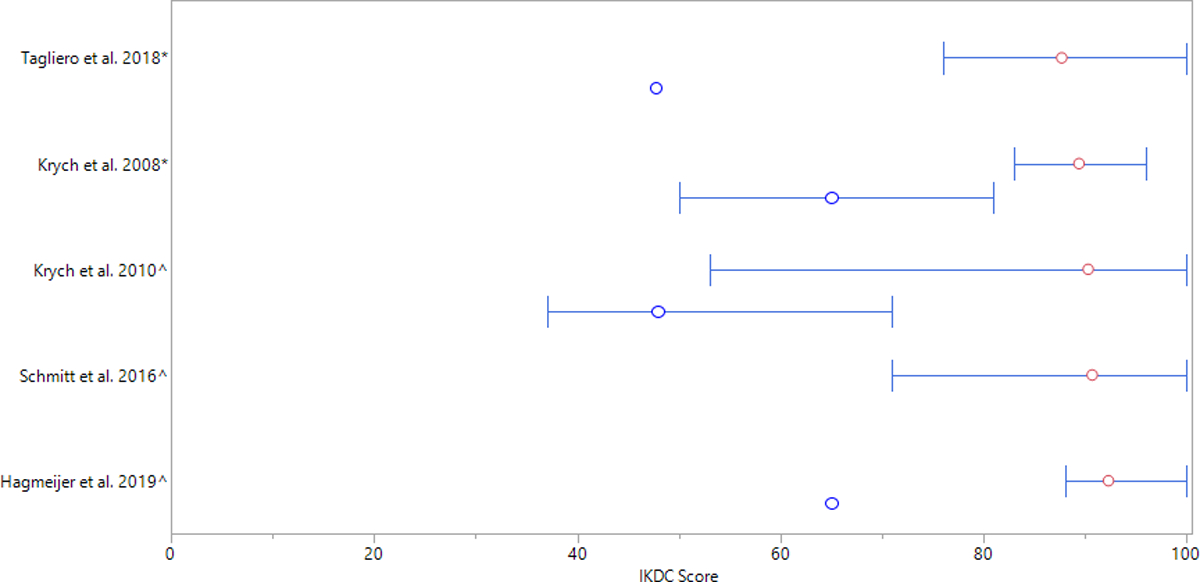

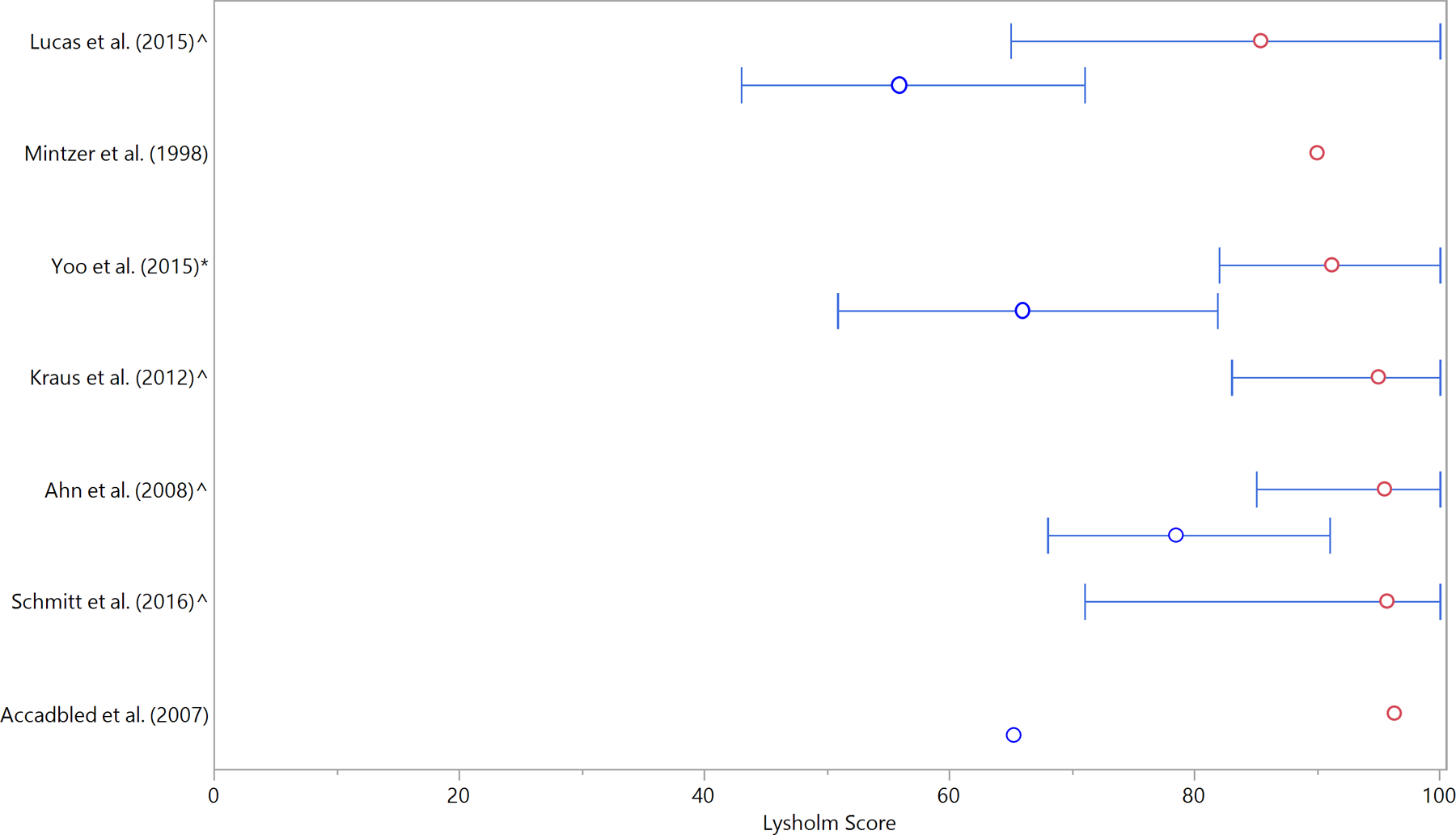

Clinical and functional outcomes were reported heterogeneously across studies, but the most commonly utilized were IKDC and Lysholm scoring systems (Table 3). Mean post-operative IKDC score were available in five studies ranging from 88–92 (Figure 3). Four of those studies, also reported mean pre-operative IKDC scores ranging from 48–65. [17, 26, 27, 53]. The mean improvement ranged from 24–42 and was significant in all four studies. (P<0.001) A mean post-operative Lysholm score was reported in seven studies, ranging from 85–96 (Figure 4). Additionally, four of those studies provided mean pre-operative Lysholm scores, ranging from 56–79. Mean improvement in those four studies ranged from 17–31, which were all statistically significant. Ahn et al. (2008) was the only study that reported HSS scores and noted a significant improvement in scores from 80 (range, 69 to 89) to 96 (range, 90 to 100) at final follow-up (P <0.001) [3].

Figure 3 – Mean Pre- and Post-operative IKDC Scores.

Red circles represent mean post-op IKDC scores whereas blue circles represent mean pre-op IKDC scores. In one case (Schmitt et al. 2016), only post-op IKDC scores were reported.[47] (*Standard deviation was reported in one study and is represented by thin lines with bars. ^Range was reported in two studies and is represented by thin lines with square bullets.)

Figure 4 – Mean Pre- and Post-operative Lysholm Scores.

Red circles represent mean post-op Lysholm scores whereas blue circles represent mean pre-op Lysholm scores. In three cases only post-op IKDC Lysholm scores were reported. (*Standard deviation was reported in one study and is represented by thin lines with bars. ^Range was reported in four studies and is represented by thin lines with square bullets.)

Activity related outcomes and time back to sport

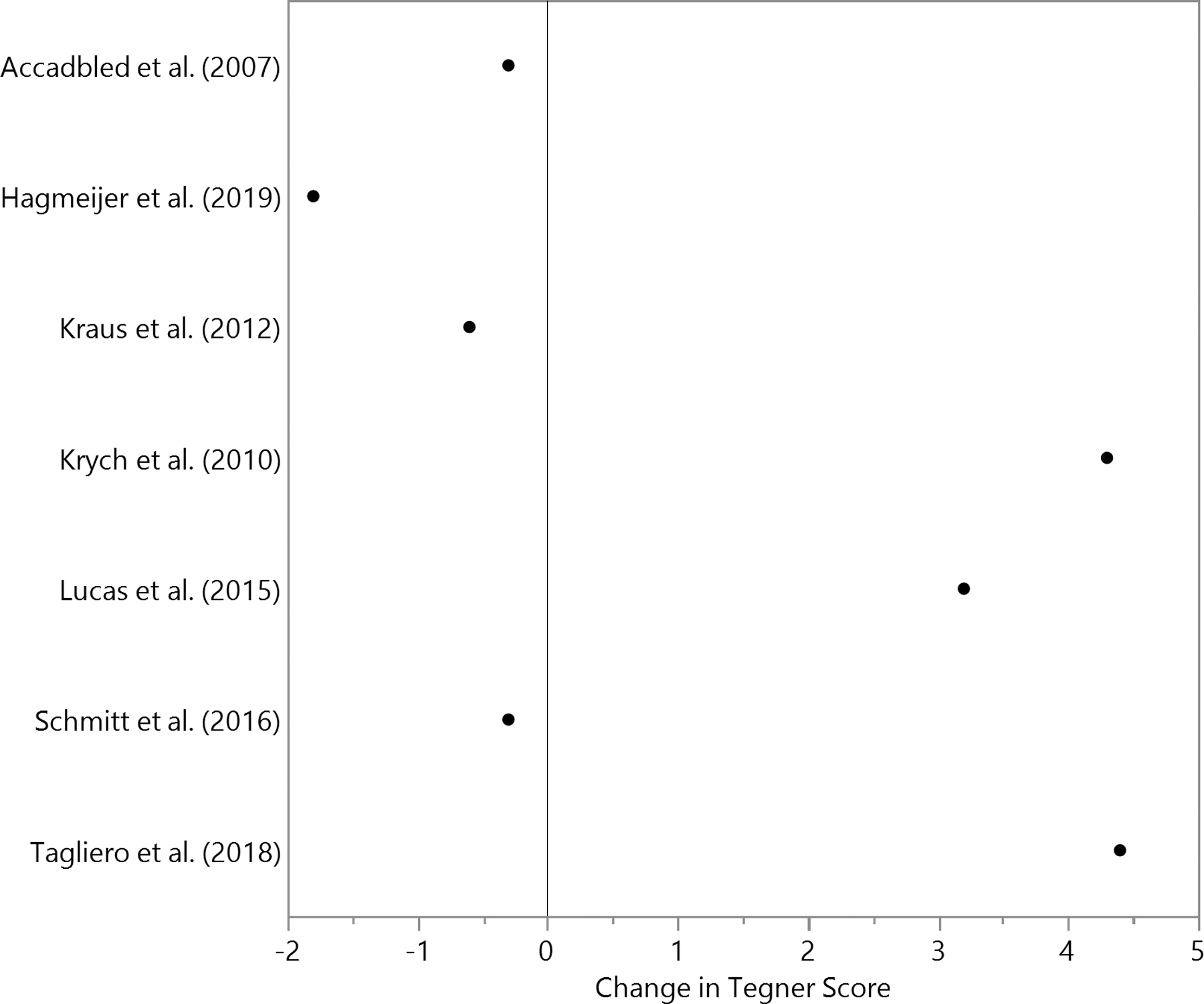

Activity level was reported in nine studies using the Tegner Activity Scale, with mean post-operative scores ranging from 6.2–8 (Table 3). The mean pre-operative Tegner score in five studies ranged from 1.9–8.3. Mean Tegner score improvement in those five studies ranged from −1.8 – 4.4 (Figure 5). Return to sport was reported in four studies, with mean values of 5.2–8.2 months in three studies [25, 26, 54]. Only two studies reported return to sport in the setting of a meniscal repair without concomitant procedure, Krych et al. reported a mean return to sport at 5.2 months and Vanderhave et al. reported a mean return to sport of 5.6 months [26]. Vanderhave et al. separately reported on return to sport after meniscal repair in the setting of concomitant ACL reconstruction at 8.2 months, and Kraus et al. reported on return to sport after meniscal repair in the setting of concomitant ACL reconstruction. The fourth study provided a range of 6–9 months in which patients returned to sport [27].

Figure 5 – Mean change in Tegner Score.

Black dots represent the mean change in Tegner score from pre-op to post-op

Risk factor analysis

Risk factor analysis for failure was reported in two studies. Krych et al. 2008 identified a rim width of ≥ 3mm, complex or a bucket handle tear types as statistically significant risk factors for failure [26]. Similarly, Krych et al. 2010 reported both complex and bucket handle tear types as significant in comparison to simple tear type, but neither was found significant in comparison to one another [27]. Similarly, Hagmeijer et al. reported that meniscal repair of complex tear patterns were significantly more likely to fail than repairs performed on simple tears with an odds ratio of 18.0 (P=0.03) however, there was no statistically significant differences when comparing amongst other tear types. Medial meniscal tears were at higher risk compared to lateral meniscal tears and rim width was not a significant factor.

Discussion:

The most important finding of this review documents meniscus repair success in 58–100% of adolescent patients with a mean follow-up of 22–211 months. This success rate is reported in conjunction with good to excellent clinical outcomes measured most commonly by Lysholm and IKDC scores These findings suggest meniscus repair as a suitable option for meniscus injury in a young population.

Failure rate varied significantly in this review (0–42%) at a mean time to failure ranging from 15–32 months. This time frame for revision is consistent with previously published literature [28, 48]. Also, this reported failure rate was similar to previous failure rates reported by systematic reviews in adult cohorts[4, 14, 46]. Variability in overall failure rates is likely multifactorial, including tear location, type and complexity, presence of concomitant procedures, evaluation methods for failure, surgical expertise, repair technique and rehabilitation protocols. Increasing tear complexity and extension into the avascular zone has previously been demonstrated to lead to poorer outcomes than simple tears [42]. One included study by Tagliero et al. displayed failure rates in a pediatric and adolescent population to be comparable across tear complexity in the long term [53]. Lateral meniscus healing has been shown to be more reliable [10, 11, 18]; but conflicting clinical reports do not support this finding [39, 53]. Paxton et al. conducted a systematic review comparing reoperation rates and clinical outcomes of meniscus repair versus partial meniscectomy. The authors reported meniscus repairs have a higher reoperation rate (20.7%) at long term follow up than partial meniscectomy (3.9%) but are associated with improved long term outcomes as demonstrated by higher Lysholm scores and less radiologic degeneration than partial meniscectomy [44].. It is well established that patients treated with meniscectomy develop osteoarthritis at an accelerated rate, a point of greater concern still with the younger patient population [6, 9, 21, 29, 30, 33, 43, 45]. Most recently the 2019 ESSKA meniscus consensus supports preservation of the meniscus as the first line of treatment because of an inferior clinical and radiological long-term outcome after partial meniscectomy compared to meniscus repair.[24] Vinayaga et al. directly compared failure rates for meniscal repair vs partial meniscectomy, reporting a 20% failure rate of meniscus repair and 48.3% failure of partial meniscectomy as defined by Lysholm Score > 80 with the absence of joint line tenderness or effusion and preserved ROM as compared to the contralateral uninjured knee favoring meniscus repair[55]A recent Meta-Analysis and review reported a 37% re-tear rate reported for patients undergoing meniscus repair, failure after meniscectomy was not directly reported however, results for 141 of 297 (47.5%) patients following meniscectomy were reported as “fair” or “poor” [38]. Further studies are needed to examine the risk factors for failure and characteristics of meniscus repairs in an isolated adolescent population.

In this review, 61% of patients underwent concomitant procedures including ACL reconstruction and central meniscectomy. Historically, the success of meniscus repair with concomitant ACL reconstruction has been more successful than meniscus repair in isolation [27, 34, 48]. The systematic review on meniscal repair in adults, aged 40 and older by Everhart et al. found that repairs with concomitant ACL reconstruction had a five percent overall failure rate versus 15% in ACL intact patients [14]. A recent population based study by Herzog et al. reviewed over 280,000 ACL reconstructions from 2002 to 2014 and showed that “among children and adolescents, rates of both isolated ACL reconstruction and ACL reconstruction with concomitant meniscal surgery increased substantially” [19]. Lateral and medial discoid menisci are present in 1.5–15.5% and 0.1–0.3% respectively. However, many discoid menisci are asymptomatic, so the true prevalence remains unknown [23, 49]. Outcomes of discoid meniscus repair are not well reported. Carter et al. demonstrated no difference in clinical outcomes between patients who underwent discoid meniscus saucerization alone versus those who had concomitant meniscal stabilization at a mean follow up of 15 months [12]. Hagino et al. report on arthroscopic treatment of symptomatic discoid meniscus in children however only 5 knees in their cohort had underwent repair [16]. Shieh et al. identified a 15% failure rate in 46 discoid saucerizations with or without concomitant meniscal repair at a mean follow up for 40 months [48]. Discoid meniscus heterogeneity is unavoidable and likely contributes to variation in the reported failure rates. Thus drawing our attention to the need for further studies to be undertaken examining the failure rates of meniscus repairs with concomitant procedures in an isolated adolescent population.

The Lysholm score is a reliable clinical outcome measure for patients with a meniscus injury [7]. Post-operative Lysholm scores range from 85–96, and reported post-operative IKDC scores range from 88–92 after meniscus repair indicating good to excellent outcomes. Historically a poor rate of good to excellent results (42%) have been reported in pediatric patients treated with uncomplicated meniscectomy at 8-year follow-up [35]. Contemporary literature displays disagreement on functional results after partial arthroscopic meniscectomy with authors reporting both poor and favorable functional results at mid-long term follow up [21, 29, 30, 45]. Billieres et al found that partial meniscectomy when used in combination with meniscal repair lead to good subjective and objective outcomes at long term follow-up in a young cohort with complex horizontal cleavage tears[5]. Xu et al. reported statistically significantly improved Lysholm scores, a trend to better IKDC scores, and less loss of activity as measured by the Tegner Activity score with meniscal repair as compared with meniscectomy in a recent meta-analysis [56]. We suggest the literature would benefit from more consistent and uniform reporting of clinical outcome scores to promote generalizability of results.

The Tegner Activity scale was reported in nine studies, ranging from 6.2–8, as a measure of their patients return to desired functional levels. This activity scale demonstrated acceptable performance as an outcome measure for patients with a meniscus injury [7]. A systematic review by Eberbach et al. reported on a heterogeneous population of 664 patents after isolated meniscus repair demonstrating a comparable post-operative mean Tegner score of 6.2 [13]. Carter et al. reported an activity level of 6 (range, 4–7) after saucerization and repair of a discoid meniscus [12]. It is important to note that return to sport in this population is often multifactorial, as our patients’ age they may no longer have the opportunity to return to competitive athletics as a result of remaining eligibility, or graduation, for example. These findings support the potential for return to competitive sport for those patients treated with meniscal repair in the adolescent population.

The present study has several limitations to note. The quality of a systematic review is dictated by the literature from which it is drawn. The literature does not contain high-level studies from which to draw data or conclusions on this topic. The studies included in this review differed widely in their tear characteristics, tear locations, and concomitant procedures with a highly variable amount of detailed information available on subgroup populations. There was an inherent level of heterogeneity in the surgical techniques, and post-operative rehabilitation protocols. Additionally, we do not have long term radiogrpahs or MRI review available, which precludes us from commenting on if these repairs appear to be chondroprotective. However, this systematic review summarized the currently available literature on the failure rates and outcomes of meniscus repair in an adolescent population, and drew attention to the need for further areas of study to address this growing patient population. This review provides the clinician with the highest currently available level of information regarding the failure rates, as well as clinical and functional outcomes of meniscal repair in the adolescent population to inform the discussion regarding surgical intervention.

Conclusion

This systematic review demonstrates that both subjective and clinical outcomes, including failure rate, Lysholm, IKDC, and Tegner activity scale scores, are good to excellent following meniscal repair in the adolescent population. This data can assist with guiding clinical decision making focused on long term knee health in the setting of an increasing incidence of adolescent meniscus tears..

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

Primary Location where this investigation was performed: Mayo, Clinic, Rochester, MN

References

- 1.Accadbled F, Cassard X, Sales de Gauzy J, Cahuzac JP (2007) Meniscal tears in children and adolescents: results of operative treatment. J Pediatr Orthop B 16:56–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agresti A, Coull BA (1998) Approximate is Better than “Exact” for Interval Estimation of Binomial Proportions. Am. Stat 52:119–126 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahn JH, Lee SH, Yoo JC, Lee YS, Ha HC (2008) Arthroscopic partial meniscectomy with repair of the peripheral tear for symptomatic discoid lateral meniscus in children: results of minimum 2 years of follow-up. Arthroscopy 24:888–898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ardizzone CA, Houck DA, McCartney DW, Vidal AF, Frank RM (2020) All-Inside Repair of Bucket-Handle Meniscal Tears: Clinical Outcomes and Prognostic Factors. Am J Sports Med; 10.1177/0363546520906141363546520906141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Billieres J, Pujol N (2019) Meniscal repair associated with a partial meniscectomy for treating complex horizontal cleavage tears in young patients may lead to excellent long-term outcomes. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 27:343–348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bolano LE, Grana WA (1993) Isolated arthroscopic partial meniscectomy: Functional radiographic evaluation at five years. Am J Sports Med 21:432–437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Briggs KK, Kocher MS, Rodkey WG, Steadman JR (2006) Reliability, validity, and responsiveness of the Lysholm knee score and Tegner activity scale for patients with meniscal injury of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am 88:698–705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brucker PU, von Campe A, Meyer DC, Arbab D, Stanek L, Koch PP (2011) Clinical and radiological results 21 years following successful, isolated, open meniscal repair in stable knee joints. Knee 18:396–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burks RT, Metcalf MH, Metcalf RW (1997) Fifteen-year follow-up of arthroscopic partial meniscectomy. Arthroscopy 13:673–679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buseck MS, Noyes FR (1991) Arthroscopic evaluation of meniscal repairs after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction and immediate motion. Am J Sports Med 19:489–494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cannon WD Jr., Vittori JM (1992) The incidence of healing in arthroscopic meniscal repairs in anterior cruciate ligament-reconstructed knees versus stable knees. Am J Sports Med 20:176–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carter CW, Hoellwarth J, Weiss JM (2012) Clinical outcomes as a function of meniscal stability in the discoid meniscus: a preliminary report. J Pediatr Orthop 32:9–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eberbach H, Zwingmann J, Hohloch L, Bode G, Maier D, Niemeyer P, et al. (2018) Sport-specific outcomes after isolated meniscal repair: a systematic review. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 26:762–771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Everhart JS, Higgins JD, Poland SG, Abouljoud MM, Flanigan DC (2018) Meniscal repair in patients age 40years and older: A systematic review of 11 studies and 148 patients. Knee 25:1142–1150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Francavilla ML, Restrepo R, Zamora KW, Sarode V, Swirsky SM, Mintz D (2014) Meniscal pathology in children: differences and similarities with the adult meniscus. Pediatr Radiol 44:910–925; quiz 907–919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hagino T, Ochiai S, Senga S, Yamashita T, Wako M, Ando T, et al. (2017) Arthroscopic treatment of symptomatic discoid meniscus in children. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 137:89–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hagmeijer MH, Kennedy NI, Tagliero AJ, Levy BA, Stuart MJ, Saris DBF, et al. (2019) Long-term Results After Repair of Isolated Meniscal Tears Among Patients Aged 18 Years and Younger: An 18-Year Follow-up Study. Am J Sports Med 47:799–806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Henning CE, Lynch MA, Clark JR (1987) Vascularity for healing of meniscus repairs. Arthroscopy 3:13–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Herzog MM, Marshall SW, Lund JL, Pate V, Mack CD, Spang JT (2018) Trends in Incidence of ACL Reconstruction and Concomitant Procedures Among Commercially Insured Individuals in the United States, 2002–2014. Sports Health 10:523–531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Higgins JPT, Green S. [2008]Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version. Chichester, England: Cochrane Collaboration; 241–284. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Higuchi H, Kimura M, Shirakura K, Terauchi M, Takagishi K (2000) Factors affecting long-term results after arthroscopic partial meniscectomy. Clin Orthop Relat Res 161–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson MJ, Lucas GL, Dusek JK, Henning CE (1999) Isolated arthroscopic meniscal repair: a long-term outcome study (more than 10 years). Am J Sports Med 27:44–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jordan MR (1996) Lateral Meniscal Variants: Evaluation and Treatment. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 4:191–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kopf S, Beaufils P, Hirschmann MT, Rotigliano N, Ollivier M, Pereira H, et al. (2020) Management of traumatic meniscus tears: the 2019 ESSKA meniscus consensus. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 28:1177–1194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kraus T, Heidari N, Svehlik M, Schneider F, Sperl M, Linhart W (2012) Outcome of repaired unstable meniscal tears in children and adolescents. Acta Orthop 83:261–266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krych AJ, McIntosh AL, Voll AE, Stuart MJ, Dahm DL (2008) Arthroscopic repair of isolated meniscal tears in patients 18 years and younger. Am J Sports Med 36:1283–1289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krych AJ, Pitts RT, Dajani KA, Stuart MJ, Levy BA, Dahm DL (2010) Surgical repair of meniscal tears with concomitant anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in patients 18 years and younger. Am J Sports Med 38:976–982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krych AJ, Reardon P, Sousa P, Levy BA, Dahm DL, Stuart MJ (2016) Clinical Outcomes After Revision Meniscus Repair. Arthroscopy 32:1831–1837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee CR, Bin SI, Kim JM, Lee BS, Kim NK (2018) Arthroscopic partial meniscectomy in young patients with symptomatic discoid lateral meniscus: an average 10-year follow-up study. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 138:369–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Longo UG, Ciuffreda M, Candela V, Rizzello G, D′Andrea V, Mannering N, et al. (2019) Knee Osteoarthritis after Arthroscopic Partial Meniscectomy: Prevalence and Progression of Radiographic Changes after 5 to 12 Years Compared with Contralateral Knee. J Knee Surg 32:407–413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lucas G, Accadbled F, Violas P, Sales de Gauzy J, Knorr J (2015) Isolated meniscal injuries in paediatric patients: outcomes after arthroscopic repair. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 101:173–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lutz C, Dalmay F, Ehkirch FP, Cucurulo T, Laporte C, Le Henaff G, et al. (2015) Meniscectomy versus meniscal repair: 10 years radiological and clinical results in vertical lesions in stable knee. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 101:S327–331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Manzione M, Pizzutillo PD, Peoples AB, Schweizer PA (1983) Meniscectomy in children: a long-term follow-up study. Am J Sports Med 11:111–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martin-Fuentes AM, Ojeda-Thies C, Vila-Rico J (2015) Clinical results following meniscal sutures: does concomitant acl repair make a difference? Acta Orthop Belg 81:690–697 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Medlar RC, Mandiberg JJ, Lyne ED (1980) Meniscectomies in children. Report of long-term results (mean, 8.3 years) of 26 children. Am J Sports Med 8:87–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mintzer CM, Richmond JC, Taylor J (1998) Meniscal repair in the young athlete. Am J Sports Med 26:630–633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 6:e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mosich GM, Lieu V, Ebramzadeh E, Beck JJ (2018) Operative Treatment of Isolated Meniscus Injuries in Adolescent Patients: A Meta-Analysis and Review. Sports Health 10:311–316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nakayama H, Kanto R, Kambara S, Kurosaka K, Onishi S, Yoshiya S, et al. (2017) Clinical outcome of meniscus repair for isolated meniscus tear in athletes. Asia Pac J Sports Med Arthrosc Rehabil Technol 10:4–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nepple JJ, Dunn WR, Wright RW (2012) Meniscal repair outcomes at greater than five years: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 94:2222–2227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Noyes FR, Barber-Westin SD (2002) Arthroscopic repair of meniscal tears extending into the avascular zone in patients younger than twenty years of age. Am J Sports Med 30:589–600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Noyes FR, Barber-Westin SD (2012) Management of meniscus tears that extend into the avascular region. Clin Sports Med 31:65–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Paradowski PT, Lohmander LS, Englund M (2016) Osteoarthritis of the knee after meniscal resection: long term radiographic evaluation of disease progression. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 24:794–800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Paxton ES, Stock MV, Brophy RH (2011) Meniscal repair versus partial meniscectomy: a systematic review comparing reoperation rates and clinical outcomes. Arthroscopy 27:1275–1288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Petty CA, Lubowitz JH (2011) Does arthroscopic partial meniscectomy result in knee osteoarthritis? A systematic review with a minimum of 8 years’ follow-up. Arthroscopy 27:419–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sarraj M, Coughlin RP, Solow M, Ekhtiari S, Simunovic N, Krych AJ, et al. (2019) Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with concomitant meniscal surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis of outcomes. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 27:3441–3452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schmitt A, Batisse F, Bonnard C (2016) Results with all-inside meniscal suture in pediatrics. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 102:207–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shieh AK, Edmonds EW, Pennock AT (2016) Revision Meniscal Surgery in Children and Adolescents: Risk Factors and Mechanisms for Failure and Subsequent Management. Am J Sports Med 44:838–843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Silverman JM, Mink JH, Deutsch AL (1989) Discoid menisci of the knee: MR imaging appearance. Radiology 173:351–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Siow HM, Cameron DB, Ganley TJ (2008) Acute knee injuries in skeletally immature athletes. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am 19:319–345, ix [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Slim K, Nini E, Forestier D, Kwiatkowski F, Panis Y, Chipponi J (2003) Methodological index for non-randomized studies (minors): development and validation of a new instrument. ANZ J Surg 73:712–716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stein T, Mehling AP, Welsch F, von Eisenhart-Rothe R, Jager A (2010) Long-term outcome after arthroscopic meniscal repair versus arthroscopic partial meniscectomy for traumatic meniscal tears. Am J Sports Med 38:1542–1548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tagliero AJ, Desai VS, Kennedy NI, Camp CL, Stuart MJ, Levy BA, et al. (2018) Seventeen-Year Follow-up After Meniscal Repair With Concomitant Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction in a Pediatric and Adolescent Population. Am J Sports Med 46:3361–3367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vanderhave KL, Moravek JE, Sekiya JK, Wojtys EM (2011) Meniscus tears in the young athlete: results of arthroscopic repair. J Pediatr Orthop 31:496–500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vinayaga P, Amalourde A, Tay YG, Chan KY (2001) Outcome of meniscus surgery at University Malaya Medical Centre. Med J Malaysia 56 Suppl D:18–23 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Xu C, Zhao J (2015) A meta-analysis comparing meniscal repair with meniscectomy in the treatment of meniscal tears: the more meniscus, the better outcome? Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 23:164–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yoo WJ, Jang WY, Park MS, Chung CY, Cheon JE, Cho TJ, et al. (2015) Arthroscopic Treatment for Symptomatic Discoid Meniscus in Children: Midterm Outcomes and Prognostic Factors. Arthroscopy 31:2327–2334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]