Abstract

Background.

Few computer-delivered brief intervention (CDBI) studies have evaluated participant satisfaction with individual elements of the intervention, or whether participant satisfaction impacts intervention outcomes.

Purpose.

This factorial trial examined whether subjective reactions to a CDBI for heavy drinking (1) varied depending on the presence versus absence of an animated narrator, a spoken voice, empathic reflections, and motivational interviewing (MI) strategies and (2) were associated with drinking outcomes at 3-month follow-up.

Methods.

Participants were 352 heavy drinking university students. All participants were randomly assigned to one of 16 versions of a CDBI. After finishing the CDBI, participants completed measures of intervention likability and perceived empathy. Alcohol use outcomes were assessed at 3-month follow-up.

Results.

CDBI characteristics had minimal effects on participant ratings of likeability and perceived empathy. However, higher likeability ratings were associated with decreases in alcohol use outcomes over the 3-month assessment period.

Conclusions.

Results indicate that subjective reactions to CDBIs can have important effects on alcohol use outcomes.

Keywords: Alcohol, brief intervention, motivational interviewing, relational factors, participant satisfaction, e-intervention

Many computer-delivered brief intervention (CDBI) studies evaluate participant satisfaction. In general, these studies suggest that CDBIs are perceived as useful, acceptable, respectful, and empathic. For example, Moore et al. (2019) found that a CDBI designed to prevent prescription opioid abuse in youths was rated as easy to use, understandable, and useful. Kiluk et al. (2018) administered a CDBI to individuals with a DSM-IV substance use diagnosis and found that 82% reported feeling ‘very satisfied’ with the intervention. In a recent review of the literature, Shingleton and Palfai (2016) evaluated 41 CDBIs that used motivational interviewing techniques, and found that most interventions were rated as supportive, acceptable, and associated with positive behaviour change. In a separate literature review, Nesvag and McKay (2018) evaluated 43 digital interventions for substance use and found that 70–90% of participants were highly satisfied with their digital intervention, found it easy to use, and were comfortable using it. Notably, recent studies suggest that CDBIs are not only acceptable, but comparable in satisfaction to in-person treatments. For example, Loree et al. (2019) delivered either an electronic or an in-person intervention for hazardous substance use to women attending reproductive healthcare clinics, and found that participant ratings of satisfaction were high, and did not differ based on delivery method (though ratings of alliance were higher for the person-delivered intervention). Similarly, Kiluk et al. (2018) found that participants receiving a cognitive behavioural CDBI for substance use reported greater overall satisfaction with the treatment and rated their experience more highly than those receiving a clinician-delivered intervention, though these differences did not reach significance.

Notably, participant satisfaction with CDBIs is almost always assessed globally, rather than with respect to specific intervention elements. In a rare exception to this, Ondersma et al. (2011) asked participants to rate their subjective reactions to 3 separate intervention components (normed feedback, decisional balance, and goal setting), immediately after completing each one. Results showed that higher self-reported satisfaction following the feedback component was associated with decreased likelihood of future drug use. While rare, these types of studies can provide specific data about how individual intervention components promote (or do not promote) overall intervention optimization.

It should also be noted that very few studies have examined the extent to which participant satisfaction is associated with CDBI outcomes. A large body of literature suggests that client reactions to in-person psychotherapy (e.g. perceived alliance, genuineness, etc.) play a critical role in therapy effectiveness (Norcross & Wampold, 2011; Norcross & Lambert, 2011; Horvath et al., 2011). However, very few studies have examined whether subjective reactions affect the outcomes of brief, computer-delivered interventions, in which clinician/client relationships, if they exist at all, are entirely different. It may be that participant satisfaction is entirely unrelated to CDBI outcomes, a finding which could call into question the substantial resources spent ensuring that CDBIs are likable and user-friendly.

The current study addressed these issues by using a factorial design to examine (1) subjective reactions to individual elements of a CDBI for heavy drinking; and (2) whether these subjective reactions were associated with drinking at 3-month follow-up. Data were drawn from a larger CDBI optimization study which used a factorial design to test the efficacy of 16 combinations of four intervention components (Grekin et al., 2019a).

Intervention Components

The four intervention components manipulated in the current study include: (1) empathic reflections, (2) motivational interviewing strategies, (3) a spoken voice, and (4) an animated narrator.

Motivational Interviewing Strategies and Empathic Reflections.

Many CDBIs are heavily influenced by motivational interviewing (Miller & Rollnick, 2002), in that they present specific motivational strategies (e.g., normed feedback), within a context of empathy, acceptance, and client autonomy (i.e., MI spirit). However, only a few studies have tested MI strategies separately from the empathic context in which they are presented. Specifically, Morgenstern et al. (2012) assigned problem drinkers to one of three conditions; a spirit only MI condition in which therapists elicited change talk and used reflective listening to create an atmosphere of warmth, an MI condition in which therapists used both relational and directive (e.g. personalized feedback, confidence rulers, change plan) elements of MI, and a self-change control condition, in which participants were given personalized feedback and encouraged to change their drinking on their own. Results revealed reductions in drinking over the study period, but no group differences in outcomes. A follow-up study using a larger sample and the same three treatment groups yielded similar findings (Morgenstern et al., 2017). These studies suggest that specific MI strategies may not increase therapeutic effectiveness beyond the interpersonal factors and MI spirit associated with motivational interventions. Notably, however, no studies have examined MI strategies and MI spirit completely independently (e.g., Morgenstern et al. (2012) compared strategies and spirit together vs. spirit alone), and none have compared the effectiveness of these factors within the context of a CDBI. Thus, it is unclear whether specific MI techniques or an overall context of empathy and warmth are driving CDBI effects. The current study addressed this by treating MI strategies and empathic reflections as separate CDBI components and assessing participants’ reactions to each.

Spoken Voice and Animated Narrator.

Some CDBIs incorporate lifelike features (e.g., a realistic narrator). The potential effectiveness of these features is supported by data which suggest that (1) humans react to computers in social ways and (2) social responses to computers are stronger in the presence of anthropomorphism and increased realism (Lee & Nass, 2002; Gong, 2008). Specifically, individuals apply social rules and expectations to computers, exhibit politeness and reciprocity towards computers (Nass et al., 1999; Moon, 2000), and adapt social behaviors based on the computer’s perceived personality (Nass & Moon, 2000). Moreover, individuals tend to rate computerized narrators/agents more positively when they have more lifelike features. For example, Gong (2008) asked undergraduates to work through a series of social dilemma scenarios with a computerized agent. The agents represented 4 levels of anthropomorphism, ranging from humanoid robot characters to actual human faces. After completing the task, participants rated the agent on competency, trust, and social judgment. Results showed that, as the agent became more anthropomorphic, ratings in all domains became more positive. However, despite these data from the field of human/computer interaction, no studies have directly compared the acceptability and efficacy of CDBIs with and without lifelike features. The current study addressed this issue by comparing CDBI versions that did and did not contain a spoken voice and an animated narrator.

The Current Study

In the current study, we hypothesized that (1) there would be main effects of all four CDBI factors on subjective reactions, such that CDBI versions that included the factor in question would produce higher satisfaction than those that did not, and (2) subjective reactions to the CDBI would predict drinking outcomes above and beyond the effects of CDBI version at 3-month follow-up.

Method

Participants

Participants were 352 students (50.9% male; 50.9% Caucasian) at a large urban university. Participants were recruited through (1) flyers posted in various campus locations and (2) advertisements placed on the university and psychology department’s websites. Flyers and advertisements called for individuals interested in participating in a paid research study on alcohol use among college students. Potential participants were asked to complete a seven-item, online screening questionnaire assessing current alcohol use. To be eligible for the study, participants were required to meet either National Institute of Alcohol and Alcoholism (NIAAA) criteria for risky drinking or Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) criteria for binge drinking. Specifically, participants were considered eligible if they endorsed at least one of the following: (1) ‘sometimes’ or ‘frequently’ consuming at least 3 (women)/4 (men) drinks per day; (2) ‘sometimes’ or ‘frequently’ consuming at least 7 (women)/14 (men) drinks per week; or (3) binge drinking at least once per week over the past 6 months (binge drinking = consuming 5 drinks in a 2-hour period). The only exclusion criterion was not being a college student. Treatment seeking status was not assessed. Participants who met the inclusion criteria were taken to a new website and asked whether they would like to be contacted by a researcher to schedule a baseline session. Identifying information for participants who were ineligible after completing the screening questionnaire was not collected and there was no further communication with these individuals.

Measures

Demographic information.

Participants were asked to report their age, gender, race/ethnicity, and level of education.

Alcohol Timeline Follow-Back Interview- Online Version (TLFB: Sobell & Sobell, 1992).

The Timeline Follow-Back Interview, a structured assessment that uses a calendar and various memory aids (e.g., mobile phone, daily planner, identification of target events), was used to assess the number of drinks per day, each day, for a month. The TLFB has a long history of use in clinical and non-clinical populations and has demonstrated high test-retest reliability (Fals-Stewart et al., 2000; Hoeppner, et al., 2010; Sobell et al., 2001). In the current study, an online version of the TLFB was administered at baseline and 3-month follow-up to obtain daily drinking estimates. We derived four specific alcohol outcomes: drinks per drinking day, total drinks, number of drinking days, and number of binge drinking days.

Subjective Reactions.

The Participant Satisfaction Questionnaire (PSQ), created for the larger optimization study, measured perceived empathy and subjective liking of the CDBI. The PSQ consisted of 15-items and responses were indicated on a 5-point Likert scale that ranged from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much). However, only 11 of these items (i.e., those that were most relevant to domains of interest based on the results of a confirmatory factor analysis.) were analyzed in this study. Four of the items assessed how much participants liked the intervention: “I liked going through the program.”; “It was interesting to use.”; “It was helpful to me.”; “I would be interested in working with the computer again.” Seven items evaluated how empathic participants found the intervention: “I felt respected.”; “ It made me feel better about myself.”; “I felt understood.”; “I felt an effort was made to understand me.”; “It was friendly and warm with me.”; “I felt supported.”; “I felt criticized.” Some items were reversed scored. Internal consistency values for the liking and perceived empathy questions were .82 and .86, respectively.

Procedure

Baseline session.

Participants were met in the laboratory by a research assistant who explained study procedures and obtained written informed consent. Participants then completed the online TLFB, as well as several other questionnaires not analyzed in the current study. After completing the questionnaires, participants were randomly assigned by the software to one of 16 conditions representing all possible combinations of the four dichotomous factors being manipulated (i.e., empathic reflections, motivational strategies, voice, and narrator; See Table 1). Intervention sessions lasted 15 to 20 minutes on average. After finishing the intervention, participants completed the Participant Satisfaction Questionnaire and were compensated with a $20 Amazon gift card. All study procedures were approved by the university’s institutional review board.

Table 1.

Experimental Conditions in a 2×2×2×2 Factorial Design

| Condition | Empathic reflection | Motivational content | Voice | Animated Narrator |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Not present | Not present | Not present | Not present |

| 2 | Not present | Not present | Not present | Present |

| 3 | Not present | Not present | Present | Not present |

| 4 | Not present | Not present | Present | Present |

| 5 | Not present | Present | Not present | Not present |

| 6 | Not present | Present | Not present | Present |

| 7 | Not present | Present | Present | Not present |

| 8 | Not present | Present | Present | Present |

| 9 | Present | Not present | Not present | Not present |

| 10 | Present | Not present | Not present | Present |

| 11 | Present | Not present | Present | Not present |

| 12 | Present | Not present | Present | Present |

| 13 | Present | Present | Not present | Not present |

| 14 | Present | Present | Not present | Present |

| 15 | Present | Present | Present | Not present |

| 16 | Present | Present | Present | Present |

Intervention.

Table 1 provides a brief overview of each of the 16 intervention conditions. In conditions with empathic reflections, participants were exposed to a series of non-judgmental reflections and statements of affirmation that were tailored to their individual responses (e.g., “You’ve felt really stuck,” “It sounds like you feel two ways about this,” “Alcohol really helps you to relax”). In conditions without empathic reflections, these reflections/affirmations were absent, but all other content was identical.

In motivational strategy conditions, participants were presented with three specific strategies: (1) personalized normed feedback showing how the participant’s drinking compares to that of same-age peers; (2) decisional balance (i.e., weighing the pros and cons of drinking); and (3) an optional goal-setting component in which participants were given the choice to set a drinking reduction goal (see Ondersma et al., 2005 for further description). Non-motivational strategy conditions provided straightforward, non-tailored didactic information about alcohol use (e.g., “The amount of alcohol in different kinds of drinks can vary. The amount of liquid in a person’s glass does not fully tell you how much alcohol is there.” or “Drinking alcohol is not necessarily a problem, but drinking too much can cause problems in relationships, school, and work, and can even negatively impact health.”)

In conditions with a voice, all content was read aloud to participants through headphones; in non-voice conditions, the content was presented exclusively as text on the screen. In conditions with a narrator, participants interacted with an animated, three-dimensional parrot who is capable of multiple specific actions (e.g., pointing, waving, yawning, etc.). The animated parrot was selected for its high likeability ratings in previous research (Ondersma et al., 2005) and its lack of any evident race or ethnicity.

Follow-Up Assessment.

Participants were contacted via email three months after the baseline assessment with a request to complete a 15-minute online follow-up assessment. The follow-up survey contained an online TLFB, as well as several measures not analyzed in the current study. Participants completing the 3-month follow-up were compensated with a $40 Amazon gift card which was sent via email. After completing the 3-month follow-up assessment, participants were e-mailed a debriefing script that explained study goals, hypotheses, and procedures. Participants were also provided with a list of local resources for alcohol use treatment.

Data Analysis

Data were screened for normality and outliers. Appropriate transformations were used where necessary to correct skewness and kurtosis (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007). To test our hypotheses, we conducted two separate 2×2×2×2 ANOVAs examining the main and interactive effects of spoken voice, animated narrator, MI strategies, and empathic reflections on mean ratings of (1) subjective liking of the intervention, and (2) perceived empathy from the intervention. We also conducted a series of hierarchical regression analyses examining relationships between subjective liking/perceived empathy and alcohol use at the 3-month follow-up. Demographics were entered into Step 1 of the model, CDBI version was entered into Step 2, baseline alcohol use was entered in Step 3, and the subjective reaction variable (i.e., liking or perceived empathy) was entered in Step 4.

Results

Data Screening

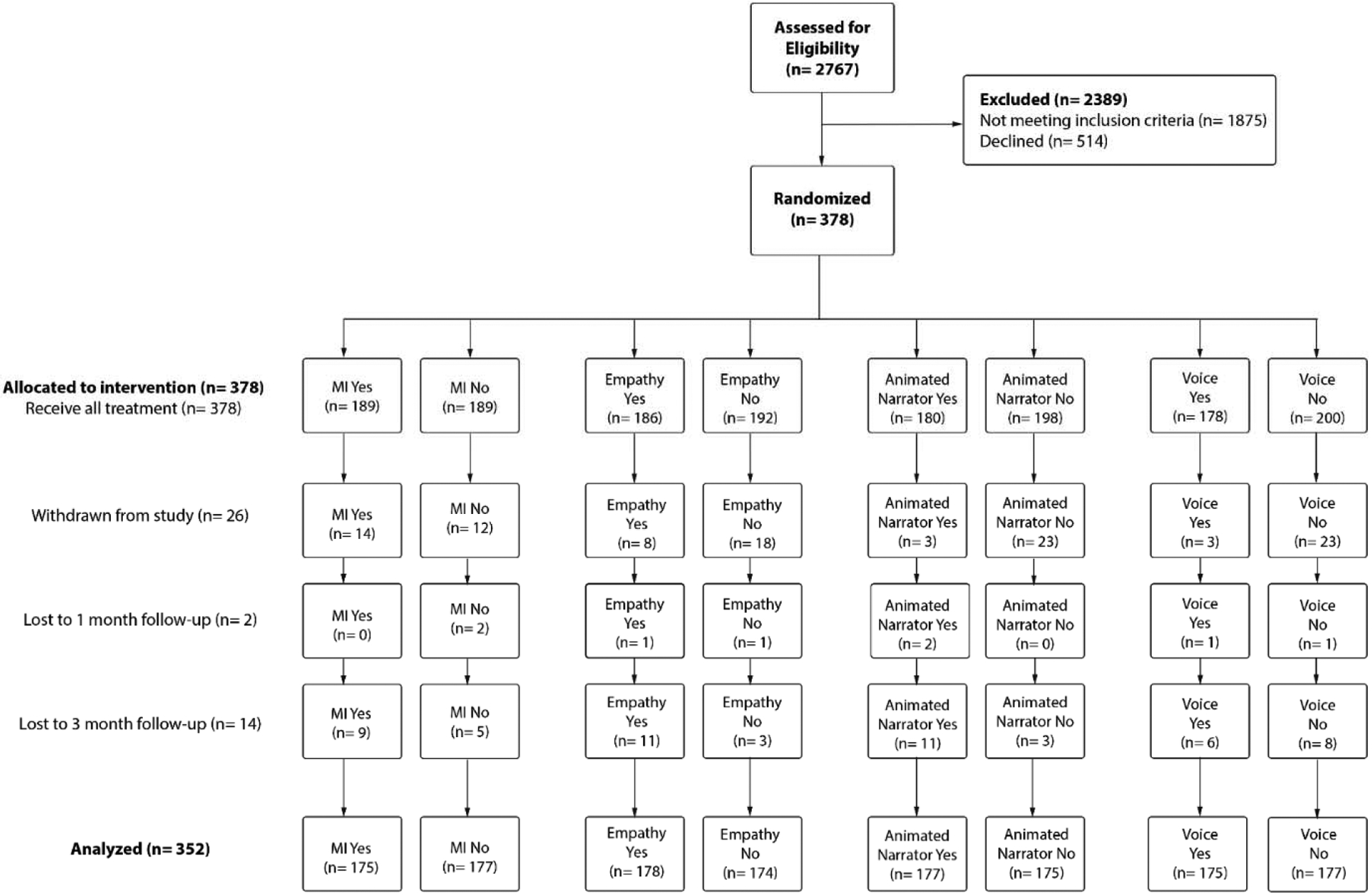

A total of 2,767 students were screened for the study, 2,389 of whom either did not meet eligibility criteria or decided not to participate. The remaining 378 participants were randomized to an intervention. Twenty-four participants were withdrawn from the study after the baseline session due to a software error. An additional two were withdrawn because of previous participation in an earlier pilot version of the study. Data from the remaining 352 participants were analyzed. Attrition was minimal with a total of 16 participants lost to follow-up over the 3-month study period (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Consolidated Standard of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) diagram.

There were no out of range values for any of the variables and all means and standard deviations were plausible, falling within the possible ranges of scale scores. All primary study variables had less than 5% of scores missing, thus, listwise deletion was used. To assess for normality, the primary study variables were evaluated for skewness and kurtosis using criteria outlined by Rose et al. (2014). Two variables, liking, and perceived empathy fell outside of acceptable ranges and were found to be negatively skewed. Square root transformations and reflections were used to correct the skew of both variables prior to their use in subsequent ANOVAs. All variables were examined for univariate outliers by standardizing primary variables into z-scores. Outliers were defined as any standardized scores falling above an absolute value of 3.29 (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007). Thirteen unique univariate outliers were identified, with subjective liking and baseline drinks per drinking day having one outlier, follow-up drinks per dinking day, follow-up total drinks, and perceived empathy each containing three outliers, and follow-up number of binge drinking days containing five outliers. No multivariate outliers were identified. The remaining outliers were eliminated from analyses, as they did not affect the results.

Descriptives and Bivariate Associations

Descriptive statistics for all primary study variables are shown in Table 2. Bivariate associations for the study variables can be seen in Table 3. All alcohol outcomes, including drinks per drinking day, total drinks, number of drinking days, and number of binge drinking days were significantly positively correlated with one another. Additionally, liking was significantly negatively correlated with three follow-up alcohol outcome variables: drinks per drinking day, number of drinking days, and number of binge drinking days. Perceived empathy was significantly negatively correlated with number of drinking days and number of binge drinking days. Neither liking nor perceived empathy were significantly associated with any baseline measures of alcohol use. Perceived empathy was significantly associated with gender, such that males had higher perceived empathy ratings.

Table 2.

Demographic and Drinking History Characteristics

| Total sample | MI Content | Empathic Reflection | Animated Narrator | Voice | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | ||

| Men (%) | 50.6 | 54.1 | 47.1 | 51.2 | 50.0 | 57.0 | 44.0 | 55.6 | 45.6 |

| White (%) | 55.9 | 61.8 | 50.0 | 54.7 | 57.1 | 50.6 | 61.3 | 56.8 | 55.0 |

| Asian (%) | 30.3 | 27.1 | 33.5 | 31.4 | 29.2 | 36.6 | 23.8 | 31.4 | 29.2 |

| Black or African American (%) | 11.5 | 10.0 | 12.9 | 10.5 | 12.5 | 10.0 | 12.5 | 12.4 | 10.5 |

| Arabic (%) | 8.2 | 1.8 | 5.3 | 4.1 | 3.0 | 2.9 | 4.2 | 3.6 | 3.5 |

| Hispanic or Latino (%) | 4.7 | 3.5 | 5.9 | 5.8 | 3.6 | 2.9 | 6.5 | 3.6 | 5.8 |

| More than one race (%) | 3.5 | 4.1 | 2.9 | 3.5 | 3.6 | 2.9 | 4.2 | 1.8 | 5.3 |

| American Indian or Alaskan Native (%) | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.2 | 2.4 | 1.2 | 2.4 | 1.2 | 2.3 |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander (%) | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 0.6 |

| Age (Mean, SD) | 24.6 (5.6) | 25.2 (6.4) | 24.0 (4.5) | 24.4 (5.3) | 24.8 (5.8) | 24.7 (6.2) | 24.5 (4.9) | 24.5 (5.6) | 24.6 (5.5) |

| Baseline Drinks per Drinking Day (Mean, SD) | 3.5 (1.4) | 3.7 (1.5) | 3.3 (1.3) | 3.6 (1.3) | 3.4 (1.5) | 3.5 (1.4) | 3.5 (1.4) | 3.4 (1.4) | 3.5 (1.4) |

| Baseline Total Drinks (Mean, SD) | 40.5 (25.7) | 43.6 (27.1) | 37.4 (23.8) | 41.5 (25.2) | 39.5 (26.2) | 38.8 (26.9) | 42.1 (24.3) | 39.6 (24.8) | 41.3 (26.6) |

| Baseline Drinking days (Mean, SD) | 11.7 (5.9) | 11.9 (5.5) | 11.4 (6.2) | 11.9 (5.7) | 11.5 (6.0) | 11.3 (6.3) | 12.1 (5.4) | 11.7 (6.2) | 11.6 (5.5) |

| Baseline Binge Drinking Days (Mean, SD) | 3.8 (3.3) | 4.2 (3.5) | 3.4 (3.1) | 4.0 (3.3) | 3.6 (3.4) | 3.5 (3.3) | 4.1 (3.4) | 3.5 (3.0) | 4.1 (3.6) |

| 3-month Follow-up Drinks per Drinking Day (Mean, SD) | 2.1 (1.6) | 3.2 (1.7) | 3.0 (1.5) | 3.1 (1.5) | 3.1 (1.7) | 3.1 (1.5) | 3.1 (1.7) | 3.1 (1.7) | 3.1 (1.5) |

| 3-month Follow-up Total Drinks (Mean, SD) | 29.3 (27.6) | 29.2 (28.3) | 29.5 (27.0) | 38.7 (25.1) | 29.9 (30.1) | 29.0 (28.1) | 29.7 (27.2) | 30.0 (29.6) | 28.6 (25.5) |

| 3-month Follow-up Drinking Days (Mean, SD) | 9.1 (6.6) | 8.6 (6.2) | 9.5 (7.0) | 9.2 (6.3) | 9.0 (7.0) | 8.9 (6.9) | 9.3 (6.3) | 9.3 (7.2) | 8.9 (6.0) |

| 3-month Follow-up Binge Drinking Days (Mean, SD) | 2.7 (3.6) | 2.6 (3.6) | 2.7 (3.5) | 2.6 (3.2) | 2.7 (3.9) | 2.6 (3.5) | 2.8 (3.7) | 2.6 (3.6) | 2.7 (3.5) |

| Subjective Liking | 15.6 (3.1) | 15.8 (3.0) | 15.4 (3.2) | 15.6 (3.2) | 15.7 (3.0) | 15.5 (3.3) | 15.8 (2.9) | 15.4 (3.1) | 15.8 (3.1) |

| Perceived Empathy | 23.1 (4.6) | 22.7 (5.0) | 23.5 (4.3) | 23.4 (4.9) | 22.8 (4.7) | 23.3 (4.7) | 22.8 (4.6) | 22.9 (4.9) | 23.2 (4.4) |

Table 3.

Bivariate Correlations for Subjective Liking, Perceived Empathy, and Alcohol Outcomes (N= 314)

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Liking | — | |||||

| 2. Perceived Empathy | .717*** | — | ||||

| 3. Drinks Per Drinking Day | −.165*** | −.103 | — | |||

| 4. Total Drinks | −.010 | −.037 | .331*** | — | ||

| 5. Days w/Any Drinks | −.189** | −.120* | .226*** | .460*** | — | |

| 6. Days Binge Drinking | −.150** | −.081* | .728*** | .424*** | .477** | — |

Note.

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

CDBI Factors and Subjective Reactions

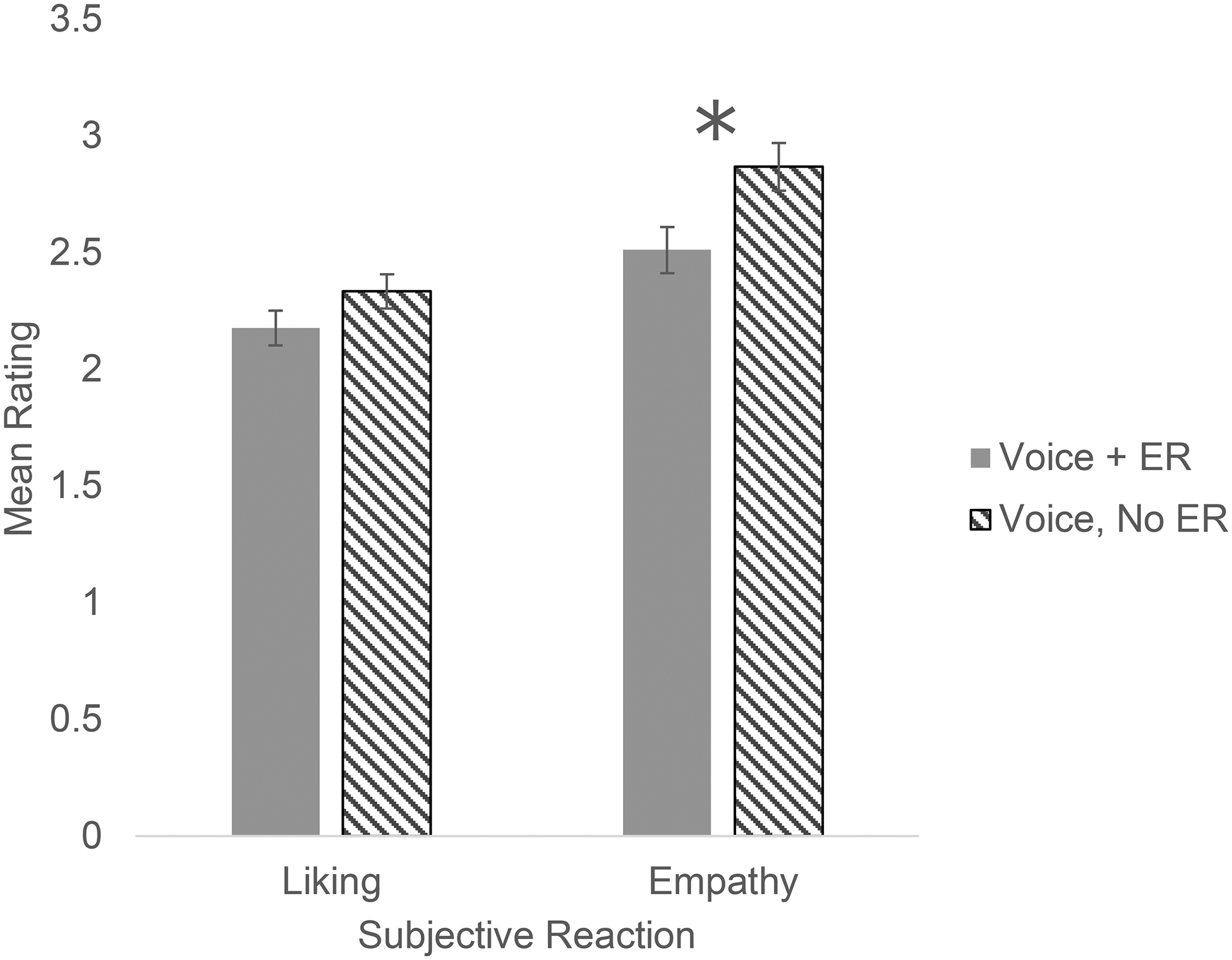

We first conducted a 2×2×2×2 ANOVA to examine the main and interactive effects of spoken voice, animated narrator, MI strategies, and empathic reflections on participants’ mean satisfaction ratings. Three and 4-way interactions were underpowered and not relevant to a priori hypotheses. Therefore, they were not interpreted. Effect coding was used to create the intervention variables, such that −1= absent and 1= present. There were no main effects of any of the CDBI factors. However, one of 10 comparisons was significant: specifically, there was a significant two-way, empathic reflections X spoken voice interaction (F(1, 324) = 5.57, p = .019, ηp2 = .017). An examination of means revealed that a spoken voice had a larger positive effect (i.e., produced greater increases in liking) when empathic reflections were absent versus when they were present (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Significant voice by empathic reflections (ER) computer-delivered brief intervention (CDBI) condition interaction on liking and empathy.

Empathy ratings were significantly higher when voice was present and there were no ER, compared to when both voice and ER were present, t(167)= −2.53, p < .05. There were no significant difference in liking rating between the two conditions, t(167)= −1.50, p > .05. Transformed variables were used in these analyses.

We conducted a second 2×2×2×2 ANOVA to examine the main and interactive effects of spoken voice, animated narrator, MI strategies, and empathic reflections on participant ratings of perceived empathy from the intervention. There were again no main effects of any of the CDBI factors. However, one of 10 comparisons was significant, in that there was a significant two-way, empathic reflections X spoken voice interaction (F(1, 324) = 6.04, p = .015, ηp2 = .018). An examination of means revealed that, when empathic reflections were absent, a spoken voice had a positive effect (i.e., produced increases in perceived empathy). Of note, when empathic reflections were present, a spoken voice had a slightly negative effect (see Figure 2). See Table 4 for a summary of the ANOVA results for all intervention conditions.

Table 4.

Analysis of Variance for Alcohol Outcomes

| Intervention | Liking | Empathy | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Common Factors | Mean diff (p-value) | .027 (.723) | −.111 (.248) |

| eta value | .000 | .004 | |

| N = | 340 | 340 | |

| Voice | Mean diff (p-value) | .093 (.226) | .037 (.697) |

| eta value | .005 | .000 | |

| N = | 340 | 340 | |

| Narrator | Mean diff (p-value) | .035 (.654) | −.12 (.211) |

| eta value | .001 | .005 | |

| N = | 340 | 340 | |

| Content | Mean diff (p-value) | −.087 (.258) | .142 (.140) |

| eta value | .004 | .007 | |

| N = | 340 | 340 | |

| Content * Common Factors | Mean diff (p-value) | −.059 (.938) | .031 (.884) |

| eta value | .000 | ||

| N = | 172 | 172 | |

| Content * Voice | Mean diff (p-value) | .006 (.553) | .179 (.296) |

| eta value | .001 | .000 | |

| N = | 169 | 169 | |

| Content * Narrator | Mean diff (p-value) | −.052 (.702) | .022 (.952) |

| eta value | .000 | .000 | |

| N = | 170 | 170 | |

| Common Factors * Voice | Mean diff (p-value) | .12 (.019) | −.074 (.015) |

| eta value | .017 | .018 | |

| N = | 169 | 169 | |

| Common Factors * Narrator | Mean diff (p-value) | .061 (.598) | −.231 (.161) |

| eta value | .001 | .006 | |

| N = | 174 | 174 | |

| Voice * Narrator | Mean diff (p-value) | .128 (.926) | −.082 (.680) |

| eta value | .000 | .001 | |

| N = | 169 | 169 |

Subjective Reactions and Alcohol Outcomes

We conducted eight separate hierarchical linear regressions to examine associations between participant reports of liking and perceived empathy and alcohol use at the 3-month follow-up (controlling for baseline alcohol use). Assumptions of linearity, normality, homoscedasticity, and multicollinearity were met. For each regression, age and gender were entered in Step 1, each CDBI element was entered in Step 2 (i.e., spoken voice, animated narrator, empathic reflections, and MI strategies), baseline alcohol use was entered in Step 3, and the subjective reaction variable (i.e., liking or perceived empathy) was entered in Step 4.

Subjective Liking, Perceived Empathy, and Alcohol Outcomes

There was a significant main effect of subjective liking on all alcohol outcomes (i.e., drinks per drinking day, total drinks, number of drinking days, and number of binge drinking days), indicating that higher levels of liking were associated with less drinking at 3-month follow-up (see Table 5). These results remained significant after using a Holm-Bonferroni correction to account for family-wise error. The presence of MI strategies was found to decrease number of drinking days. There was also a significant effect of gender on drinks per drinking day, such that male gender was associated with more drinks per drinking day.

Table 5.

Regressions for Subjective Liking, Perceived Empathy, and Alcohol Outcomes

| Variable | β | t | p | ΔR2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subjective Liking | ||||

| Drinks per Drinking Day | −.163 | −3.47 | .001 | .026 |

| Total Drinks | −.146 | −3.19 | .002 | .021 |

| Number of Drinking Days | −.138 | −3.16 | .002 | .019 |

| Number of Binge Drinking Days | −.152 | −3.04 | .003 | .022 |

| Perceived Empathy | ||||

| Drinks per Drinking Day | −.107 | −2.23 | .027 | .011 |

| Total Drinks | −.095 | −2.03 | .043 | .009 |

| Number of Drinking Days | −.079 | −1.75 | .080 | .006 |

| Number of Binge Drinking Days | −.078 | −1.52 | .129 | .006 |

There was a significant main effect of perceived empathy on drinks per drinking day and total drinks, indicating that higher levels of perceived empathy predicted lower levels of these variables (see Table 5). However, after correcting for family-wise error using the Holm-Bonferroni method, these outcomes were no longer significant. Perceived empathy also did not have a significant effect on the number of drinking days or the number of binge drinking days. MI strategies were found to be a significant predictor for number of drinking days and total drinks. Additionally, gender was a significant predictor for drinks per drinking day, such that men reported more drinks per drinking day.

Discussion

While numerous studies have examined the efficacy of brief computerized interventions for alcohol use, fewer have focused on subjective reactions to these interventions, particularly reactions to individual elements of the intervention (Butler & Correia, 2009; Grekin et al., 2019b; Kypri et al., 2004). Thus, it is unclear whether certain CDBI components are more readily accepted or valued by respondents than others. It is also unclear whether subjective reactions to CDBIs are related to behavioral outcomes. The current study addressed these issues by examining subjective reactions to a CDBI for alcohol use and whether those reactions predicted alcohol outcomes at 3-month follow-up.

Contrary to expectation, CDBI components, both individually and in combination, were largely unrelated to subjective liking and perceived empathy. This is in contrast with previous research showing that participants prefer interventions with anthropomorphized, relational agents (Bickmore & Picard, 2005) and feel more supported in CDBIs that incorporate empathic reflections (Ellis et al., 2017). The null results from the present study may be attributable to the method in which the subjective liking and perceived empathy scales were operationalized. However, both empathy and liking scales demonstrated high internal consistency (alphas = .86 and .82) and both were predictive of alcohol outcomes. Another factor that warrants consideration is the fact that participants rated all versions of the CDBI as highly likable and empathic. Specifically, the mean likeability rating was 15.6 out of 20.0, whereas the mean perceived empathy rating was 23.0 out of 35.0. Therefore, it may be difficult to improve participants’ ratings on these scales (i.e., there may be a ceiling effect).

Although most CDBI components were unrelated to subjective reactions, there was a significant two-way interaction between empathic reflections and voice, such that a spoken voice produced increases in subjective liking and perceived empathy when empathic reflections were absent but resulted in decreases in liking and perceived empathy when empathic reflections were present. Notably, the voice used in the intervention was fairly robotic. Thus, participants may have perceived a disconnect between the verbal expression of empathy (e.g., “It sounds like you’ve really struggled with this”) and a voice that sounded emotionless, potentially leading to dissatisfaction or feelings that the narrator was insincere. Alternatively, participants may have felt that the combination of a spoken voice and the expression of empathic reflections was too realistic. A growing body of literature suggests that when an animated narrator or other humanoid object possesses humanistic characteristics (e.g., a voice, facial expressions, gestures) which cause it to be perceived as overly realistic, reactions to the narrator shift from positive emotional responses to feelings of unease and aversion (i.e., the uncanny valley phenomenon; Mori, 1970; 2012). Thus, the combination of empathic reflections and spoken voice in the present study may have been perceived as overly realistic and unsettling to participants, resulting in lower ratings of subjective liking and perceived empathy. While both of these explanations are plausible, it is important to note that the size of the voice X empathic reflections interaction was quite small (partial eta squared = .017) and that these positive effects may have been the result of chance, given the number of comparisons. Future studies are needed to replicate this finding both with the current intervention and other interventions.

As predicted, study results showed that participants who reported greater liking of the intervention, exhibited less alcohol use across multiple drinking indices over the 3-month study period. Moreover, these results remained significant even after controlling for baseline drinking, CDBI version, and demographics. These results are consistent with previous studies which have found that intervention satisfaction is positively associated with treatment outcomes in both person-delivered (Boden & Moos, 2009; Carlson & Gabriel, 2001; Donovan et al., 2002; Zhang et al., 2008) and computer-delivered (Ondersma et al., 2011) interventions.

Contrary to liking, perceived empathy did not have a significant effect on alcohol outcomes. It is not entirely clear why these two subjective reactions (i.e., liking and empathy) had different effects on alcohol use. It is possible that likeable interventions increase motivation or engagement more than empathic interventions. It is also possible that liking encompasses a broader range of participant reactions than perceived empathy (i.e., participants who say they like the intervention may do so because they find it helpful, engaging, easy to use, friendly, etc.). However, this is the first study to directly examine the effects of both liking and perceived empathy on CDBI alcohol outcomes, and more research is clearly needed to clarify these findings. Additionally, it is important to note that the relationship between liking and alcohol was similar in magnitude (small), and in the same direction as the relationship between perceived empathy and alcohol use. Thus, differences in the effects of these two variables may be due to low power or a statistical artefact, rather than to meaningful differences in relationships.

The results from the present study underscore the importance of examining subjective reactions to CDBIs, in addition to behavioral outcomes. While this type of assessment is common practice in fields such as marketing, it is less common in intervention research. Notably, the current study only assessed two subjective reactions, overall liking, and perceived empathy. Participant ratings of other reactions (e.g., excitement, engagement, dislike) may also be associated with intervention outcomes. Further, it is unclear whether certain participant perceptions are more relevant for certain types of outcomes (e.g., relationship-based perceptions, such as perceived empathy or respect, might be most important for sensitive behaviors or those that are most difficult to change). There also may be any number of interactions between intervention type and participant characteristics in determining participant perceptions of an intervention. Future studies are needed to address these issues.

Implications and Future Directions

The present study is one of the first to examine relationships between CDBI components, immediate subjective reactions to the intervention, and future behavioral outcomes. Moreover, the study was longitudinal, with excellent retention rates and a racially diverse student sample. Overall, these results suggest that although specific CDBI components did not differ in terms of subjective participant ratings, some of those ratings were significantly associated with drinking outcomes. Future research aimed at delineating specific intervention content/features that enhance positive subjective reactions is needed to optimize the efficiency and efficacy of CDBIs. Given the unexpected finding that participants preferred the CDBI voice condition where empathic reflections were absent, future studies using CDBIs that incorporate these components may to wish solicit input from participants concerning their perception of the voice in order to better understand their subjective reactions.

Several limitations should be considered. First, the sample consisted entirely of university students, limiting generalizability. Second, the follow-up period of three months precludes determination of whether effects would persist in a longer-term study. Third, the Participant Satisfaction Questionnaire, which was used to assess liking and perceived empathy, is a new measure which lacks extensive validity data. This measure was developed for the present study due to a dearth of existing, validated measures. Nonetheless, study results should be replicated with other, well-validated participant reaction measures, particularly those with established concurrent and predictive validity. Fourth, participant engagement and social desirability were not assessed, both of which may have affected the findings. Finally, due to the online nature of the follow-up assessment, bioverification of participants’ self-reported alcohol consumption was not possible. In the future, studies examining relationships between subjective liking, perceived empathy, and CDBI outcomes may wish to incorporate a longer follow-up period to better determine whether the CDBI effects persist over time. Additionally, it may be beneficial to examine whether the positive effects of the CDBI on alcohol outcomes also occur in individuals who are heavier drinkers or meet criteria for an alcohol use disorder. Overall, however, the current study adds to the literature and highlights the importance of assessing subjective reactions to brief interventions.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of Alcohol and Alcoholism under Grant #1R21AA023660-01A1 to Emily R. Grekin and by the National Institute of Mental Health Grant K01 MH110600 to Lucy McGoron.

Footnotes

In accordance with Taylor & Francis policy and his ethical obligation as a researcher, Dr. Steven J. Ondersma reports that he has a financial and/or business interests in a company that may be affected by the research reported in the enclosed paper. He has disclosed those interests fully to Taylor & Francis and has in place an approved plan for managing any potential conflicts arising from this involvement.

References

- Bickmore TW, & Picard RW (2005). Establishing and maintaining long-term human-computer relationships. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction, 12(2), 293–327. [Google Scholar]

- Boden MT & Moos R (2009). Dually diagnosed patients’ responses to substance use disorder treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 37, 335–345. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2009.03.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler LH, & Correia CJ (2009). Brief alcohol intervention with college student drinkers: Face-to-face versus computerized feedback. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 23(1), 163–167. doi: 10.1037/a0014892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson MJ, & Gabriel RM (2001). Patient satisfaction, use of services, and one-year outcomes in publicly funded substance abuse treatment. Psychiatric Services, 52(9), 1230–1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis JD, Grekin ER, Beatty JR, McGoron L, LaLiberte BV, Pop DE … Ondersma SJ. (2017). Effects of narrator empathy in a computer delivered brief intervention for alcohol use. Contemporary Clinical Trials, 61, 29–32. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2017.07.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan DM, Kadden RM, DiClemente CC, & Carroll KM (2002). Client satisfaction with three therapies in the treatment of alcohol dependence: Results from Project MATCH. Am J Addict, 11, 291–307. DOI: 10.1080/10550490290088090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fals-Stewart W, O’Farrell TJ, Freitas TT, McFarlin SK, & Rutigliano P (2000). The timeline followback reports of psychoactive substance use by drug-abusing patients: psychometric properties. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68(1), 134. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.68.1.134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grekin ER, Beatty JR, McGoron L, Kugler KC, McClure JB, Pop DE, & Ondersma SJ (2019a). Testing the efficacy of motivational strategies, empathic reflections, and lifelike features in a computerized intervention for alcohol use: A factorial trial. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 1–9. 10.1037/adb0000502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grekin ER, Beatty JR, & Ondersma SJ (2019b). Mobile health interventions: Exploring the use of common relationship factors. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth, 7(4), 1–9. doi: 10.2196/11245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong L (2008). How social is social responses to computers? The function of the degree of anthropomorphism in computer representations. Computers in Human Behavior, 24, 1494–1509. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2007.05.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoeppner BB, Stout RL, Jackson KM, & Barnett NP (2010). How good is fine-grained Timeline Follow-back data? Comparing 30-day TLFB and repeated 7-day TLFB alcohol consumption reports on the person and daily level. Addictive Behaviors, 35(12), 1138–1143. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.08.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath AO, Del Re AC, Flückiger C, & Symonds D (2011). Alliance in individual psychotherapy. Psychotherapy, 48(1), 9–16. 10.1037/a0022186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiluk BD, Nich C, Buck MB, Devore KA, Frakforter TL, LaPlagia DM, Muvvala SB, Carroll KM (2018). Randomized clinical trial of computerized and clinician-delivered CBT in comparison with standard outpatient treatment for substance use disorders: Primary within-treatment and follow-up outcomes. Am J Psychatry, 175(9), 853–863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kypri K, Saunders JB, Williams SM, McGee RO, Langley JD, Cashell-Smith ML, & Gallagher SJ (2004). Web-based screening and brief intervention for hazardous drinking: A double-blind randomized controlled trial. Addiction, 99, 1410–1417. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00847.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee EJ & Nass C (2002). Experimental tests of normative group influence and representation effects in computer-mediated communication: When interacting via computers differs from interacting with computers. Human Communication Research, 28, 349–381. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2958.2002.tb00812.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Loree AM, Yonkers KA, Odersma SJ, Gilstad-Hayden K, & Martino S (2019). Comparing satisfaction, alliance and intervention components in electronically delivered and in-person brief interventions for substance use among childbearing-aged women. J Subst Abuse Treat, 99, 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, & Rollnick S (2002). Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Moon Y (2000). Intimate exchanges: Using computers to elicit self-disclosure from consumers. Journal of Consumer Research, 26(4), 323–339. 10.1086/209566 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moore SK, Grabinski M, Bessen S, Borodovsky JT, & Marsch LA (2019). Web-Based Prescription Opioid Abuse Prevention for Adolescents: Program Development and Formative Evaluation. JMIR formative research, 3(3), e12389 10.2196/12389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgenstern J, Kuerbis A, Amrhein P, Hail L, Lynch K, & McKay JR (2012). Motivational interviewing: A pilot test of active ingredients and mechanisms of change. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 26, 859–869. doi: 10.1037/a0029674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgenstern J, Kuerbis A, Houser J, Levak S, Amrhein P, Shao S, & McKay JR (2017). Dismantling motivational interviewing: Effects on initiation of behavior change among problem drinkers seeking treatment. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 31, 751–762. doi: 10.1037/adb0000317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori M (1970). The uncanny valley. Energy, 7(4), 33–35. [Google Scholar]

- Mori M, MacDorman K, & Kageki N (2012). The Uncanny Valley [From the Field]. IEEE Robotics & Automation Magazine, 19, 98–100. doi: 10.1109/MRA.2012.2192811 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nass C, & Moon Y (2000). Machines and mindlessness: Social responses to computers. Journal of Social Issues, 56(1), 81–103. 10.1111/0022-4537.00153 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nass C, Moon YM, & Carney P (1999). Are people polite to computers? Responses to computer-based interviewing systems. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 29(5), 1093–1110. 10.1111/j.1559-1816.1999.tb00142.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nesvåg S & McKay JR (2018). Feasibility and effects of digital interventions to support people in recovery from substance use disorders: Systematic review. J Med Internet Res, 20(8), doi: 10.2196/jmir.9873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norcross JC & Lambert MJ (2011). Psychotherapy relationships that work II. Psychotherapy, 48(1), 4–8. doi: 10.1037/a0022180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norcross JC & Wampold BE (2011). Evidence-based therapy relationships: Research conclusions and clinical practices. Psychotherapy, 48(1), 98–102. doi: 10.1037/a0022161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ondersma SJ, Chase SK, Svikis DS, & Schuster CR (2005). Computer-based brief motivational intervention for perinatal drug use. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 28(4), 305–312. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2005.02.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ondersma SJ, Grekin ER, & Svikis D (2011). The potential for technology in brief interventions for substance use, and during-session prediction of computer-delivered brief intervention response. Substance Use & Misuse, 46(1), 77–86. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2011.521372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose S, Spinks N, & Canhoto A (2014). Management Research: Applying the Principles. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Shingleton RM& Palfai TP. (2016). Technology-delivered adaptations of motivational interviewing for health-related behaviors: A systematic review of the current research. Patient Educ Couns. 99(1):17–35. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2015.08.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Agrawal S, Annis H, Ayala-Velazquez H, Echeverria L, Leo GI, … Ziolkowski M (2001). Cross-cultural evaluation of two drinking assessment instruments: Alcohol timeline followback and inventory of drinking situations. Substance Use & Misuse, 36(3), 313–331. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, & Sobell MB (1992). Timeline follow-back, in Measuring Alcohol Consumption (Litten RZ, & Allen JP. eds), pp. 41–72. Humsn Press, Totowa, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, & Fidell LS (2007). Experimental designs using ANOVA Thomson/Brooks/Cole. Chicago: Thomson/Brooks/Cole. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Gerstein DR, Friedman PD (2008). Patient satisfaction and sustained outcomes of drug abuse. Journal of Health Psychology, 13(3), 388–400. DOI: 10.1177/1359105307088142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]