Abstract

Aims

Despite the effects of statins in reducing cardiovascular events and slowing progression of coronary atherosclerosis, significant cardiovascular (CV) risk remains. Icosapent ethyl (IPE), a highly purified eicosapentaenoic acid ethyl ester, added to a statin was shown to reduce initial CV events by 25% and total CV events by 32% in the REDUCE-IT trial, with the mechanisms of benefit not yet fully explained. The EVAPORATE trial sought to determine whether IPE 4 g/day, as an adjunct to diet and statin therapy, would result in a greater change from baseline in plaque volume, measured by serial multidetector computed tomography (MDCT), than placebo in statin-treated patients.

Methods and results

A total of 80 patients were enrolled in this randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Patients had to have coronary atherosclerosis as documented by MDCT (one or more angiographic stenoses with ≥20% narrowing), be on statin therapy, and have persistently elevated triglyceride (TG) levels. Patients underwent an interim scan at 9 months and a final scan at 18 months with coronary computed tomographic angiography. The pre-specified primary endpoint was change in low-attenuation plaque (LAP) volume at 18 months between IPE and placebo groups. Baseline demographics, vitals, and laboratory results were not significantly different between the IPE and placebo groups; the median TG level was 259.1 ± 78.1 mg/dL. There was a significant reduction in the primary endpoint as IPE reduced LAP plaque volume by 17%, while in the placebo group LAP plaque volume more than doubled (+109%) (P = 0.0061). There were significant differences in rates of progression between IPE and placebo at study end involving other plaque volumes including fibrous, and fibrofatty (FF) plaque volumes which regressed in the IPE group and progressed in the placebo group (P < 0.01 for all). When further adjusted for age, sex, diabetes status, hypertension, and baseline TG, plaque volume changes between groups remained significantly different, P < 0.01. Only dense calcium did not show a significant difference between groups in multivariable modelling (P = 0.053).

Conclusions

Icosapent ethyl demonstrated significant regression of LAP volume on MDCT compared with placebo over 18 months. EVAPORATE provides important mechanistic data on plaque characteristics that may have relevance to the REDUCE-IT results and clinical use of IPE.

Keywords: Atherosclerosis, Prevention, Coronary artery disease, Cardiac CT, Progression

See page 3933 for the editorial comment on this article (doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa750)

Translational perspectives

Given the robust cardiovascular event reduction seen in clinical trials of icosapent ethyl, this study demonstrates that one potential mechanism of benefit of this therapy is to slow atherosclerosis progression, and indeed, cause plaque regression. This study shows that most coronary plaque types demonstrated slowed rates of progression under the influence of statin plus icosapent ethyl. A translational use of this information would be to potentially use this therapy in addition to statin therapy in cases with presence of significant atherosclerosis.

Introduction

Statins have proven very successful at reducing cardiovascular (CV) risk and slowing progression of atherosclerosis, however, there is persistent CV risk that remains elevated in patients at high risk and those with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD). This persistent risk is especially high in those with elevated triglycerides (TGs), as event rates have been shown to remain elevated despite maximally tolerated statins.1 In the Reduction of Cardiovascular Events with EPA—Intervention Trial (REDUCE-IT), initial ASCVD events were reduced by 25% and total CV events by 32%, however, the true mechanism of benefit is not fully characterized.2–4

Icosapent ethyl (IPE) is an omega-3 poly-unsaturated fatty acid that is thought to exert beneficial effects on the atherosclerotic pathway with multiple mechanisms (improvements in lipid oxidation, inflammation, plaque volume, membrane stabilization, and dyslipidaemia).5 , 6 Icosapent ethyl has been shown to improve TGs and other lipid parameters without increasing low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C).7

We hypothesized that IPE could have anti-atherosclerotic properties.8 The objective of the Effect of Vascepa on Improving Coronary Atherosclerosis in People With High Triglycerides Taking Statin Therapy (EVAPORATE: NCT029226027) study was to evaluate the effects of 4 g of IPE per day as an adjunct to diet and statin therapy, in patients with elevated fasting TG levels on coronary computed tomographic angiography (CCTA) plaque volumes over 18 months of therapy.9

Methods

Study endpoints

The purpose of this study was to investigate whether IPE at 4 g/day, as an adjunct to diet and statin therapy, in patients with hypertriglyceridaemia (fasting TGs of 135–499 mg/dL at randomization) effected coronary plaque progression over 18 months. The primary endpoint was the change in low-attenuation plaque (LAP) volume measured by multidetector computed tomography (MDCT) angiography [then sequentially: total plaque (TP), total non-calcified plaque (TNCP), fibrofatty (FF), fibrous (F), and calcified plaque (C)].

Study population

A total of 80 patients were enrolled in this randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. To be included, patients had to be aged 30–85 years with known coronary atherosclerosis (narrowing of ≥20% in 1 coronary artery by either invasive angiography or CCTA), elevated fasting TG levels (135–499 mg/dL), and low-density lipoprotein levels (LDL‐C) between ≥40 and ≤115 mg/dL. Patients had to be on stable statin therapy, with or without ezetimibe, diet, and exercise for ≥4 weeks prior to study entry. All patients were instructed to maintain a low cholesterol diet and to continue on current statin therapy.

Study design

The study design and rationale for EVAPORATE have been published previously.9 Briefly, EVAPORATE was a multi-centre, randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial that evaluated the effect of IPE 4 g/day on coronary plaque progression determined by CCTA compared with mineral oil placebo. Consistent with the trial design, 80 patients were enrolled at three different centres (Harbor-UCLA, Lundquist Institute, and Intermountain Health Care). Patients were randomized 1:1 to IPE or placebo to evaluate progression rates of plaque volume on CCTA. Participants underwent an MDCT scan at baseline and then an interim scan at 9 months and the final MDCT scan at 18 months. We present the final results as pre-specified in the design paper and at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT029226027).9 The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at each site and was conducted in accordance with the principles of Good Clinical Practice and the trial conformed to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients provided written informed consent prior to randomization.

Placebo composition and icosapent ethyl

Pharmaceutical grade mineral oil placebo used in EVAPORATE consisted of a purified liquid mixture of straight chain saturated hydrocarbons that meet the compendial requirements of the United States National Formulary for light mineral oil and of the European Pharmacopoeia (Ph. Eur.) for light liquid paraffin oil, chosen for its similar appearance and consistency to IPE. The placebo oil is virtually free of all aromatic hydrocarbons, unsaturated hydrocarbons, and other related impurities. The total daily dose of placebo was four 1 g soft gelatine capsules, with two capsules taken twice daily with meals.

Active treatment consisted of IPE, which is a highly purified, stable, ethyl ester of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA). Icosapent ethyl is ≥96% pure as a result of multiple intermediate process steps, including distillation and chromatography.

Coronary plaque assessment

Quantitative plaque assessment was performed according to a previously defined protocol10 using semi-automated plaque analysis software (QAngioCT Research Edition Version 2.0.5; Medis Medical Imaging Systems). Based on the guidelines of the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, 17-segment coronary artery model vessels were assessed. Only vessels greater than 1.5 mm were evaluated.

Plaque quantification

Plaque volume was assessed per slice in all affected coronary segments measured by semi-automated quantification software (QAngio, Medis, Netherlands). First, an automatic tree extraction algorithm was used to obtain all three-dimensional centrelines of the coronary tree. Based on these centrelines, straightened multiplanar reconstruction (MPR) volumes were created of all vessels. Next, the lumen border contoured and vessel wall borders were assessed using spatial first- and second-derivative gradient filters in longitudinal cross-sections. Thereafter, lumen and vessel contours were detected in the individual transversal cross-sections perpendicular to the centrelines. This method is insensitive to differences in attenuation values between data sets and independent of window and level settings. Once automated software had completed the vessel trace, an expert reader manually corrected areas of misregistration. The volume of each plaque was determined by the programme quantitatively and checked for proper alignment by an expert reader. For each lesion, minimal lumen diameter was summed, and plaque reported as non-calcified, low attenuation, fibrous, fibrofatty, or calcified. The protocol for quantitative plaque assessment has been widely used in numerous previous studies by the principal investigator as well as other groups.11–15 Reproducibility was deemed excellent (R = 0.99) in a similar study design by the CT core lab.16

Plaque composition

Plaque composition was based upon predefined fixed intensity cut-off values of computed tomography (CT) attenuation. These are based upon studies by comparing coronary computed tomographic angiography (CCTA) with virtual histology by IVUS or histological examination in our lab and others. The fixed HU cut-off values that were used for classifying were: −50 to 50 for LAP, 51–130 for fibrofatty, 131–350 for fibrotic, and >350 for dense calcium. These values were initially based on Brodoefel et al. 17 and empirically optimized using three representative training sets. The inter- and intra-observer variability for the lumen and plaque volumes has been previously described.

Power analysis

Assuming an average of 1.7 measurable plaques per patient, with intra-patient plaque correlation of 0.24, 70 patients would provide power of 0.80 and a two-sided type 1 error of 0.048 to detect an 8% difference in plaque volume between the active and placebo groups. The 0.048 is a function of the Lan-DeMets version of the O’Brien-Fleming group sequential boundaries for a two-look sequential design reflecting part of the initial alpha (0.05) spend at the interim analysis conducted at 9 months.9

Statistical analyses

Baseline comparisons, which included demographics, coronary risk factors, laboratory tests, and coronary plaque volume/composition, between the two arms utilized the chi-square statistic and Student’s t-test and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test, as appropriate. The Fisher’s exact test was used when comparing categorical variables with few data points. Results are presented as counts and frequencies (per cent) for discrete variables and mean and standard deviations or median for continuous variables. Per cent change in plaque between baseline and 18 months is presented as change in plaque divided by baseline plaque. Univariable analysis and multiple linear regression were used to examine the change in plaque volumes between the cohorts. Outcome variables of each plaque type were log transformed to satisfy the assumptions of linear regression. Multivariable models were adjusted by age, sex, diabetes status, hypertension, and baseline TG levels.

All statistical analyses report two-sided P-values for the outcomes. A P-value <0.048 was considered significant for the outcomes. All analyses were performed using SAS for Windows, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). All analyses were performed using intention-to-treat, with study subjects analysed by treatment group assigned regardless of study drug adherence.

Results

Population characteristics

A total of 80 eligible subjects were enrolled, with 68 completing the 18-month visit and having interpretable CCTA at baseline and the 18-month visit. The mean age of the participants was 57.4 ± 6 years, with 37 being male. Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics, stratified by arm (IPE group, n = 31 and placebo group, n = 37) of the study participants.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the EVAPORATE cohort

| Total | IPE | Placebo | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 68 | 31 | 37 | ||

| Mean or count (SD/%) | Mean or count (SD/%) | Mean or count (SD/%) | P | |

| Age, years | 57.4 (8.7) | 56.5 (8.9) | 58.3 (8.6) | 0.394a |

| Gender, male | 37 (54.4%) | 17 (54.8%) | 20 (54.1%) | 0.948b |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 33.7 (6.7) | 34.1 (6.5) | 33.3 (6.9) | 0.632a |

| Time between Visit 1 and 5 | 17.8 (3.8) | 17.2 (4.0) | 18.2 (3.6) | 0.275a |

| Ethnicity, Hispanic | 37 (54.4%) | 18 (58.1%) | 19 (51.4%) | 0.580b |

| Race, White | 56 (82.4%) | 28 (90.3%) | 28 (75.7%) | 0.565b |

| Aspirin use | 37 (54.4%) | 15 (48.4%) | 22 (59.5%) | 0.361b |

| Diabetes mellitus | 47 (69.1%) | 22 (71.0%) | 25 (67.6%) | 0.763b |

| Family history | 22 (32.4%) | 9 (29.0%) | 13 (35.1%) | 0.592b |

| Statin medication use | 68 (100.0%) | 31 (100.0%) | 37 (100.0%) | – |

| Hypertension | 52 (76.5%) | 24 (77.4%) | 28 (75.7%) | 0.866b |

| Past smoking | 29 (42.6%) | 13 (41.9%) | 16 (43.2%) | 0.986b |

Independent T-test.

Chi-square test.

Baseline demographics and risk factors (including age, BMI, hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidaemia, and smoking prevalence) were not significantly different between the IPE and placebo groups (Table 1). In addition, there were no differences in vital signs or baseline laboratory results (including lipids, glucose, estimated glomerular filtration rate, and inflammatory markers) between groups (data not shown). Mean TG levels at baseline for subjects were 259.1±78.1 mg/dL, with no significant differences between placebo and active treatment groups.

Baseline plaque characteristics

Table 2 demonstrates plaque characteristics and individual plaque volumes (i.e. total plaque volumes) at baseline between the IPE and placebo groups. The most common plaque type (expressed as % of total plaque) was fibrous plaque in both IPE and placebo groups (74.7% vs. 57.9%, respectively). However, LAP, representing the primary endpoint, was the least common plaque type, with only 5.1% and 6.5% of the total plaque at baseline in the IPE and placebo groups, respectively.

Table 2.

Plaque changes by treatment group

| Treatment group | Baseline | Follow-up | Difference | GLM modelling |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plaque type | Mean (SD) a | Mean (SD)a | Mean (SD)a | Unadj. P | Adj. P | %chg | |

| Calcification | IPE | 3.6 (2.0) | 3.6 (1.9) | 0.0 (0.5) | 0.0464 | 0.0531 | −1% |

| Placebo | 2.9 (1.9) | 3.3 (2.1) | 0.4 (1.2) | 15% | |||

| Fibro-fatty | IPE | 2.7 (1.5) | 1.8 (1.7) | −0.9 (1.3) | <0.0001 | 0.0002 | −34% |

| Placebo | 1.5 (1.5) | 2 (1.5) | 0.5 (1.4) | 32% | |||

| Fibrous | IPE | 4.2 (1.6) | 3.3 (1.6) | −0.9 (1.1) | 0.0012 | 0.0028 | −20% |

| Placebo | 3.3 (1.3) | 3.3 (1.5) | 0.0 (1.0) | 1% | |||

| Low-attenuation plaque | IPE | 1.9 (1.8) | 1.6 (1.7) | −0.3 (1.5) | 0.0037 | 0.0061 | −17% |

| Placebo | 0.8 (1.5) | 1.6 (1.8) | 0.9 (1.7) | 109% | |||

| Total non-calcified plaque | IPE | 4.5 (1.7) | 3.9 (1.3) | −0.8 (1.2) | 0.0002 | 0.0005 | −19% |

| Placebo | 3.5 (1.6) | 3.6 (1.5) | 0.3 (1.3) | 9% | |||

| Total plaque | IPE | 5.0 (1.8) | 4.5 (1.8) | −0.5 (0.8) | 0.001 | 0.0019 | −9% |

| Placebo | 4.1 (1.8) | 4.6 (1.4) | 0.4 (1.2) | 11% | |||

Volumes reported are log adjusted mm3, GLM adjusted for age, gender, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, triglyceride level at baseline. GLM, generalized linear model.

Changes with therapy

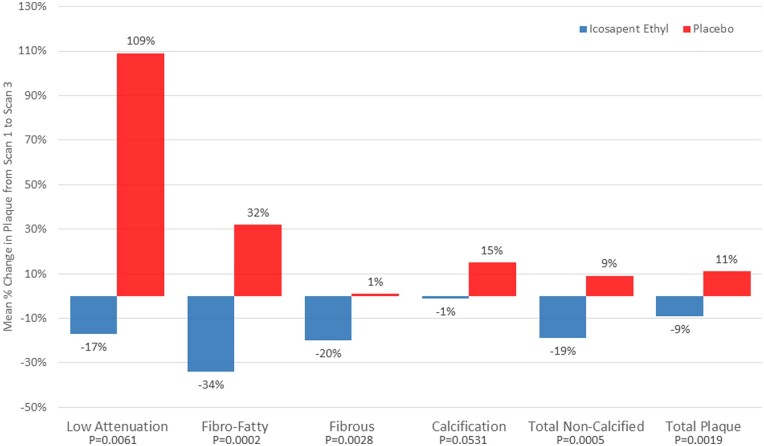

After multivariable adjustment for age, sex, diabetes status, hypertension, and baseline TG, plaque volume changes between groups were significantly different. The primary endpoint of the study, changes in LAP between 18-month scan and baseline scan, was significantly reduced with IPE compared with placebo (−0.3 ± 1.5 vs. 0.9 ± 1.7 mm3, P = 0.006). Other parameters of interest (in order of pre-specified analysis) include: total plaque (−9% with IPE vs. +11% with placebo, P = 0.002), total non-calcified plaque (−19% vs. +9%, P = 0.0005), fibrofatty (−34% vs. +32%, P = 0.0002), fibrous (−20% vs. 1%, P = 0.003), and calcified plaque (−1% vs. +15%, P = 0.053) (Figure 1, Table 2). All reported changes are using intention-to-treat analysis.

Figure 1.

Mean plaque progression for each type of plaque composition measured on cardiovascular CT for the icosapent ethyl and placebo groups (icosapent ethyl group, n = 31 and placebo group, n = 37) after multivariable adjustment. Univariable analysis and multiple linear regression were used to examine the change in plaque levels between the cohorts. Multivariable models were adjusted by age, sex, diabetes status, hypertension, and baseline triglyceride levels. All statistical analyses report two-sided P-values for the outcomes. A P-value <0.048 was considered significant for the outcomes.

Only dense calcium did not show a significant difference between groups in multivariable modelling (P = 0.053) but did show a significant difference versus placebo in univariable analysis (P = 0.046).

Laboratory outcomes

There were no significant differences in basic lipid measures of total cholesterol, LDL-C, HDL-C, and TG levels from baseline to follow-up with either therapy. Triglyceride levels did go in the direction hypothesized, with the IPE group showing an average decrease of 89.3 ± 91.1 mg/dL vs. the placebo decrease of 92.1 ± 104.3 mg/dL (P = 0.91). The LDL-C levels did not increase in either group and were not significantly different between groups. In the IPE treatment arm, LDL-C decreased by 2.4 ± 31.8 mg/dL vs. 12.8 ± 37.5 mg/dL in the placebo group (P = 0.23). High-density lipoproteins increased slightly in both groups (IPE 0.7 ± 8.4 mg/dL; placebo 0.7 ± 5.9 mg/dL, P = 0.53).

Discussion

Given the benefits of IPE in the REDUCE-IT trial to reduce CV events, understanding the mechanism of benefit becomes paramount. Plaque volumes by cardiac CT have been validated in multiple clinical trials and used as a measure of atherosclerosis in dozens of studies. Markers of plaque burden have been shown to be powerful predictors of ASCVD events, as greater plaque burdens are associated with worse CV outcomes. Vulnerable plaque has been demonstrated to be a combination of LAP (low-density plaque thought to be primarily necrotic core), along with spotty calcification, a thin fibrous cap, and positive remodelling.18 Evaluating a 5-year prospective outcome study of cardiac CT angiography, LAP burden was the strongest predictor of myocardial infarction, independent of cardiac risk score, coronary artery calcium score, or coronary artery area stenosis severity. Patients with LAP burden >4% were 4.65 times more likely to suffer a myocardial infarction (P < 0.001). A prior study concluded that in symptomatic patients, LAP burden was the strongest predictor of myocardial infarction.19

There have been several studies using CCTA to evaluate plaque burden changes over time utilizing different therapies.11–16 The present study was performed to provide a mechanistic assessment of the benefits of IPE on atherosclerosis. We have previously reported on the interim 9 month CCTA data of the EVAPORATE study, whereby patients treated with IPE 4 g/day plus statin therapy vs. statin therapy alone showed an early, significant slowing of progression in total plaque, non-calcified plaque, fibrous, and calcific plaque volumes.20 Icosapent ethyl was associated with slowing of plaque progression, however, the trial at that interim analysis failed to meet stopping criteria, with no significant difference between IPE and placebo in rates of progression of LAP. The final data at 18 months showed significant improvement in all plaque volumes except calcified plaque utilizing 4 g/day of IPE compared with placebo. Statin therapy despite reducing atherosclerotic plaque increases coronary calcification21; however, in our study, there was no increase in coronary artery calcium volume on IPE therapy, with a trend of decreasing calcification compared with placebo (P = 0.053). Eicosapentaenoic acid has been shown to reduce warfarin-induced arterial calcification in rats22 and prevent arterial calcification in Klotho mutant mice.23 A recent prospective study compared the effects of pitavastatin 2 mg/day, pitavastatin 4 mg/day and pitavastatin 2 mg/day + 1.8 g EPA/day on the progression of coronary artery calcium over 12 months utilizing MDCT. There were no significant differences in the mean Agatston score progression rates between the three groups (respectively, 34%, 42%, and 44%; P = 0.88).24 Thus, further studies are necessary to determine if IPE modifies calcified plaque volume. Icosapent ethyl induced slowing of plaque progression occurred with no significant differences in the change in LDL-C or TGs between groups. The effect of EPA reducing lipid volume on top of statin therapy vs. statin alone without significant between group changes in LDL-C or TGs has also been seen with other imaging modalities such as integrated backscatter intravascular ultrasound (IB-IVUS).25 Icosapent ethyl’s robust reduction in plaque progression without any significant difference in LDL-C or TGs compared with placebo is consistent with pleiotropic, non-lipid effects. Icosapent ethyl has been shown to have anti-thrombotic, anti-platelet, anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidant, anti-arrhythmic, and pro-resolving effects which could have beneficial effects on multiple steps of the atherosclerotic pathway.8 , 26

This study supports earlier work that IPE is associated with improvements in outcomes and intravascular ultrasound serial plaque studies. Two randomized outcome studies have demonstrated benefit with EPA when added to statin therapy. The first, which did not use a placebo, was the JELIS Trial.4 JELIS enrolled >18 000 statin-treated Japanese patients, and EPA at a dose of 1.8 g/day plus low-dose statin therapy resulted in a 19% relative risk reduction of coronary events when compared with statin monotherapy.4 The second, which did use a placebo, was the REDUCE-IT trial,2 which also demonstrated CV benefit with IPE in addition to statin therapy, with a 25% relative risk reduction in atherosclerotic events when 4 g/day of IPE was added to statin therapy. The EVAPORATE trial was designed to be a mechanistic study to parallel REDUCE-IT, using the same mineral oil placebo, and similar inclusion and exclusion criteria were used in both studies. Since the publication of the REDUCE-IT trial, a few opinion pieces suggested that the benefits of IPE were partly due to the harmful effects of the mineral oil placebo. To evaluate this, we looked at the rates of change of our patients in the EVAPORATE study who were subject to mineral oil (the placebo cohort) and compared with a second study that used a cellulose-based placebo.27 The goal was to evaluate if mineral oil resulted in faster plaque progression rates, which may lead to overestimates of the beneficial plaque changes seen with IPE. However, there was absolutely no difference in plaque progression between mineral oil and cellulose-based placebos.21

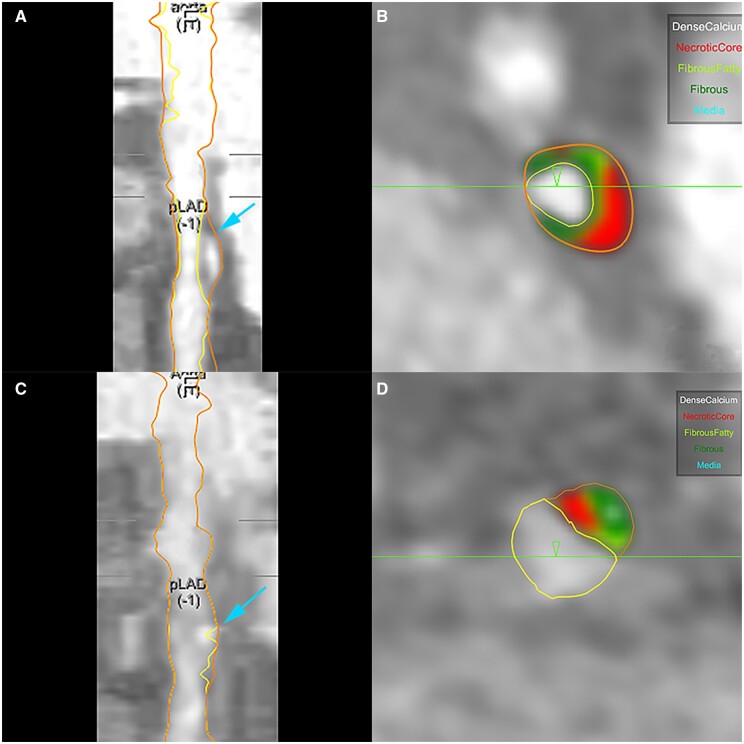

EVAPORATE is the first study to evaluate coronary plaque characteristics using CCTA to assess IPE as an adjunct to statin therapy in a CV population with persistently high TGs. This study demonstrated that IPE + statin were associated with slowed plaque progression, and indeed regression, compared with statin plus placebo (Figure 2). EVAPORATE provides important data to further elucidate the significant REDUCE-IT clinical benefits and utility of IPE.28 Since LAP is associated with vulnerability and future myocardial infarction, reducing this necrotic core with IPE is highly supportive of the clinical findings from JELIS and REDUCE-IT,2 , 4 and consistent with CHERRY25 and similar studies, in which EPA is associated with reduction in plaque progression, with plaque stabilization, and decreased ASCVD events.29

Figure 2.

54 year old male with history of diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidaemia on optimal statin therapy randomized to icosapent ethyl and followed for 18 months. Figures (C and D) demonstrate significant regression of LAP (in red) compared with baseline (A and B). (A, B) Coronary Segmentation model of proximal LAD and quantitative measurement of different plaque types at baseline. (C, D) Coronary Segmentation model of same site in proximal LAD and quantitative measurement of different plaque types at 18-month follow-up. Dense Calcium: white; Necrotic Core or Low-Attenuation Plaque: red; Fibrous Fatty: light green; Fibrous: dark green.

Limitations

The study’s primary limitation is a small sample size, though the trial was adequately powered to detect a significant difference in the primary endpoint. The study duration of EVAPORATE is similar to studies using intravascular ultrasound for serial plaque progression, following patients for 18–24 months. EVAPORATE was not powered for long-term outcomes but designed as an accompaniment trial to the REDUCE-IT randomized outcome trial. Importantly, this is the first pair of studies to associate reductions in CCTA plaque volumes (EVAPORATE) to improvements in outcomes (REDUCE-IT) using similar study designs and interventions. This further supports outcome data convincingly demonstrating benefit of IPE on ASCVD events in patients with hypertriglyceridaemia whose lipid profiles require more than statin monotherapy.30 , 31

Recent guidelines have recommended CT angiography as a method to identify at-risk patients32 , 33 as well as IPE as a treatment to reduce CV risk.34

In conclusion, the ability to retard progression and induce regression of atherosclerosis, as demonstrated by the EVAPORATE results, provides important mechanistic data on the clinical effects of IPE on plaque characteristics and vulnerability.

Funding

The study was funded by Amarin Pharma, Inc. (Bridgewater NJ, USA). As an investigator-initiated study (M.J.B.), the company had no input in analysis, endpoint adjudication, or study performance or measures.

Conflict of interest: D.L.B. discloses the following relationships—Advisory Board: Cardax, CellProthera, Cereno Scientific, Elsevier Practice Update Cardiology, Level Ex, Medscape Cardiology, PhaseBio, PLx Pharma, Regado Biosciences; Board of Directors: Boston VA Research Institute, Society of Cardiovascular Patient Care, TobeSoft; Chair: American Heart Association Quality Oversight Committee; Data Monitoring Committees: Baim Institute for Clinical Research (formerly Harvard Clinical Research Institute, for the PORTICO trial, funded by St. Jude Medical, now Abbott), Cleveland Clinic (including for the ExCEED trial, funded by Edwards), Contego Medical (Chair, PERFORMANCE 2), Duke Clinical Research Institute, Mayo Clinic, Mount Sinai School of Medicine (for the ENVISAGE trial, funded by Daiichi Sankyo), Population Health Research Institute; Honoraria: American College of Cardiology (Senior Associate Editor, Clinical Trials and News, ACC.org; Vice-Chair, ACC Accreditation Committee), Baim Institute for Clinical Research (formerly Harvard Clinical Research Institute; RE-DUAL PCI clinical trial steering committee funded by Boehringer Ingelheim; AEGIS-II executive committee funded by CSL Behring), Belvoir Publications (Editor in Chief, Harvard Heart Letter), Duke Clinical Research Institute (clinical trial steering committees, including for the PRONOUNCE trial, funded by Ferring Pharmaceuticals), HMP Global (Editor in Chief, Journal of Invasive Cardiology), Journal of the American College of Cardiology (Guest Editor; Associate Editor), K2P (Co-Chair, interdisciplinary curriculum), Level Ex, Medtelligence/ReachMD (CME steering committees), MJH Life Sciences, Population Health Research Institute (for the COMPASS operations committee, publications committee, steering committee, and USA national co-leader, funded by Bayer), Slack Publications (Chief Medical Editor, Cardiology Today’s Intervention), Society of Cardiovascular Patient Care (Secretary/Treasurer), WebMD (CME steering committees); Other: Clinical Cardiology (Deputy Editor), NCDR-ACTION Registry Steering Committee (Chair), VA CART Research and Publications Committee (Chair); Research Funding: Abbott, Afimmune, Amarin, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cardax, Chiesi, CSL Behring, Eisai, Ethicon, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, Forest Laboratories, Fractyl, Idorsia, Ironwood, Ischemix, Lexicon, Lilly, Medtronic, Pfizer, PhaseBio, PLx Pharma, Regeneron, Roche, sanofi-aventis, Synaptic, The Medicines Company; Royalties: Elsevier (Editor, Cardiovascular Intervention: A Companion to Braunwald’s Heart Disease); Site Co-Investigator: Biotronik, Boston Scientific, CSI, St. Jude Medical (now Abbott), Svelte; Trustee: American College of Cardiology; Unfunded Research: FlowCo, Merck, Novo Nordisk, Takeda. Dr Budoff discloses the following: Amarin grant support and speakers bureau, General electric grant support. J.R.N. discloses the following: Amarin, Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Boston Heart Diagnostic speaker bureaus. Consultant and advisor to and stock shareholder of Amarin Pharma and Amgen.

Contributor Information

Matthew J Budoff, Department of Medicine, Lundquist Institute at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, 1124 W Carson Street, Torrance, CA 90502, USA.

Deepak L Bhatt, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital Heart & Vascular Center and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA.

April Kinninger, Department of Medicine, Lundquist Institute at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, 1124 W Carson Street, Torrance, CA 90502, USA.

Suvasini Lakshmanan, Department of Medicine, Lundquist Institute at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, 1124 W Carson Street, Torrance, CA 90502, USA.

Joseph B Muhlestein, Intermountain Heart Institute, Intermountain Medical Center, Salt Lake City, UT, USA.

Viet T Le, Intermountain Heart Institute, Intermountain Medical Center, Salt Lake City, UT, USA; Department of Medicine, Rocky Mountain University of Health Profession, Provo, UT, USA.

Heidi T May, Intermountain Heart Institute, Intermountain Medical Center, Salt Lake City, UT, USA.

Kashif Shaikh, Department of Medicine, Lundquist Institute at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, 1124 W Carson Street, Torrance, CA 90502, USA.

Chandana Shekar, Department of Medicine, Lundquist Institute at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, 1124 W Carson Street, Torrance, CA 90502, USA.

Sion K Roy, Department of Medicine, Lundquist Institute at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, 1124 W Carson Street, Torrance, CA 90502, USA.

John Tayek, Department of Medicine, Lundquist Institute at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, 1124 W Carson Street, Torrance, CA 90502, USA.

John R Nelson, California Cardiovascular Institute, Fresno, CA, USA.

References

- 1. Fan W, Philip S, Granowitz C, Toth PP, Wong ND. Hypertriglyceridemia in statin-treated US adults: the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Clin Lipidol 2019;13:100–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bhatt DL, Steg PG, Miller M, Brinton EA, Jacobson TA, Ketchum SB, Doyle RT, Juliano RA, Jiao L, Granowitz C, Tardif J-C, Ballantyne CM; REDUCE-IT Investigators. Cardiovascular risk reduction with icosapent ethyl for hypertriglyceridemia. N Engl J Med 2019;380:11–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bhatt DL, Steg PG, Miller M, Brinton EA, Jacobson TA, Ketchum SB, Doyle RT, Juliano RA, Jiao L, Granowitz C, Tardif J-C, Gregson J, Pocock SJ, Ballantyne CM ; REDUCE-IT Investigators. Effects of icosapent ethyl on total ischemic events: from REDUCE-IT. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;73:2791–2802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yokoyama M, Origasa H, Matsuzaki M, Matsuzawa Y, Saito Y, Ishikawa Y, Oikawa S, Sasaki J, Hishida H, Itakura H, Kita T, Kitabatake A, Nakaya N, Sakata T, Shimada K, Shirato K; Japan EPA lipid intervention study (JELIS) Investigators. Effects of eicosapentaenoic acid on major coronary events in hypercholesterolaemic patients (JELIS): a randomised open-label, blinded endpoint analysis. Lancet (London, England) 2007;369:1090–1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Patel AA, Budoff MJ. Effects of eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid on lipoproteins in hypertriglyceridemia. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes 2016;23:145–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Budoff M. Triglycerides and triglyceride-rich lipoproteins in the causal pathway of cardiovascular disease. Am J Cardiol 2016;118:138–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lakshmanan S, Shekar C, Kinninger A, Dahal S, Onuegbu A, Cai AN, Hamal S, Birudaraju D, Cherukuri L, Flores F, Dailing C, Roy SK, Bhatt DL, Nelson JR, Budoff MJ. Association of high-density lipoprotein levels with baseline coronary plaque volumes by coronary CTA in the EVAPORATE trial. Atherosclerosis 2020;305:34–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Borow KM, Nelson JR, Mason RP. Biologic plausibility, cellular effects, and molecular mechanisms of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) in atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis 2015;242:357–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Budoff M, Muhlestein BJ, Le VT, May HT, Roy S, Nelson JR. Effect of Vascepa (icosapent ethyl) on progression of coronary atherosclerosis in patients with elevated triglycerides (200-499 mg/dL) on statin therapy: rationale and design of the EVAPORATE study. Clin Cardiol 2018;41:13–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Osawa K, Nakanishi R, Win TT, Li D, Rahmani S, Nezarat N, Sheidaee N, Budoff MJ. Rationale and design of a randomized trial of apixaban vs warfarin to evaluate atherosclerotic calcification and vulnerable plaque progression. Clin Cardiol 2017;40:807–813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Matsumoto S, Nakanishi R, Alani A, Rezaeian P, Li D, Fahmy M, Abraham J, Dailing C, Flores F, Hamal S, Broersen A, Kitslaar P, Budoff MJ. The effects of aged garlic extract on the regression of coronary plaque in patients with metabolic syndrome: a prospective randomized double-blind study. J Nutr 2016;146:427–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nakanishi R, Ceponiene I, Osawa K, Luo Y, Kanisawa M, Megowan N, Nezarat N, Rahmani S, Broersen A, Kitslaar PH, Dailing C, Budoff MJ. Plaque progression assessed by a novel semi-automated quantitative plaque software on coronary computed tomography angiography between diabetes and non-diabetes patients: a propensity-score matching study. Atherosclerosis 2016;255:73–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zeb I, Li D, Nasir K, Malpeso J, Batool A, Flores F, Dailing C, Karlsberg RP, Budoff M. Effect of statin treatment on coronary plaque progression—a serial coronary CT angiography study. Atherosclerosis 2013;231:198–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lee J, Nakanishi R, Li D, Shaikh K, Shekar C, Osawa K, Nezarat N, Jayawardena E, Blanco M, Chen M, Sieckert M, Nelson E, Billingsley D, Hamal S, Budoff MJ. Randomized trial of rivaroxaban versus warfarin in the evaluation of progression of coronary atherosclerosis. Am Heart J 2018;206:127–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Win TT, Nakanishi R, Osawa K, Li D, Susaria SS, Jayawardena E, Hamal S, Kim M, Broersen A, Kitslaar PH, Dailing C, Budoff MJ. Apixaban versus warfarin in evaluation of progression of atherosclerotic and calcified plaques (prospective randomized trial). Am Heart J 2019;212:129–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Budoff MJ, Ellenberg SS, Lewis CE, Mohler ER, Wenger NK, Bhasin S, Barrett-Connor E, Swerdloff RS, Stephens-Shields A, Cauley JA, Crandall JP, Cunningham GR, Ensrud KE, Gill TM, Matsumoto AM, Molitch ME, Nakanishi R, Nezarat N, Matsumoto S, Hou X, Basaria S, Diem SJ, Wang C, Cifelli D, Snyder PJ. Testosterone treatment and coronary artery plaque volume in older men with low testosterone. JAMA 2017;317:708–716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Brodoefel H, Reimann A, Heuschmid M, Tsiflikas I, Kopp AF, Schroeder S, Claussen CD, Clouse ME, Burgstahler C. Characterization of coronary atherosclerosis by dual-source computed tomography and HU-based color mapping: a pilot study. Eur Radiol 2008;18:2466–2474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Virmani R, Burke AP, Kolodgie FD, Farb A. Vulnerable plaque: the pathology of unstable coronary lesions. J Interv Cardiol 2002;15:439–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Williams MC, Kwiecinski J, Doris M, McElhinney P, D’Souza MS, Cadet S, Adamson PD, Moss AJ, Alam S, Hunter A, Shah ASV, Mills NL, Pawade T, Wang C, Weir McCall J, Bonnici-Mallia M, Murrills C, Roditi G, van Beek EJR, Shaw LJ, Nicol ED, Berman DS, Slomka PJ, Newby DE, Dweck MR, Dey D. Low-attenuation noncalcified plaque on coronary computed tomography angiography predicts myocardial infarction: results from the multicenter SCOT-HEART trial (Scottish Computed Tomography of the HEART). Circulation 2020;141:1452–1462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Budoff MJ, Muhlestein JB, Bhatt DL, Le Pa VT, May HT, Shaikh K, Shekar C, Kinninger A, Lakshmanan S, Roy S, Tayek J, Nelson JR. Effect of icosapent ethyl on progression of coronary atherosclerosis in patients with elevated triglycerides on statin therapy: a prospective, placebo-controlled randomized trial (EVAPORATE): interim results. Cardiovasc Res 2020; 10.1093/cvr/cvaa184. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21. Nasir K, Bittencourt MS, Blaha MJ, Blankstein R, Agatson AS, Rivera JJ, Miedema MD, Sibley CT, Shaw LJ, Blumenthal RS, Budoff MJ, Krumholz HM. Implications of coronary artery calcium testing among statin candidates according to American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Cholesterol Management Guidelines: MESA (Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis). J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;66:1657–1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kanai S, Uto K, Honda K, Hagiwara N, Oda H. Eicosapentaenoic acid reduces warfarin-induced arterial calcification in rats. Atherosclerosis 2011;215:43–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nakamura K, Miura D, Saito Y, Yunoki K, Koyama Y, Satoh M, Kondo M, Osawa K, Hatipoglu OF, Miyoshi T, Yoshida M, Morita H, Ito H. Eicosapentaenoic acid prevents arterial calcification in klotho mutant mice. PLoS One 2017;12:e0181009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Miyoshi T, Kohno K, Asonuma H, Sakuragi S, Nakahama M, Kawai Y, Uesugi T, Oka T, Munemasa M, Takahashi N, Mukohara N, Habara S, Koyama Y, Nakamura K, Ito H, PEACH Investigators. Effect of intensive and standard pitavastatin treatment with or without eicosapentaenoic acid on progression of coronary artery calcification over 12 months—prospective multicenter study. Circ J 2018;82:532–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Watanabe T, Ando K, Daidoji H, Otaki Y, Sugawara S, Matsui M, Ikeno E, Hirono O, Miyawaki H, Yashiro Y, Nishiyama S, Arimoto T, Takahashi H, Shishido T, Miyashita T, Miyamoto T, Kubota I ; CHERRY Study Investigators. A randomized controlled trial of eicosapentaenoic acid in patients with coronary heart disease on statins. J Cardiol 2017;70:537–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nelson JR, True WS, Le V, Mason RP. Can pleiotropic effects of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) impact residual cardiovascular risk? Postgrad Med 2017;129:822–827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lakshmanan S, Shekar C, Kinninger A, Dahal S, Onuegbu A, Cai AN, Hamal S, Birudaraju D, Roy SK, Nelson JR, Budoff MJ, Bhatt DL. Comparison of mineral oil and non-mineral oil placebo on coronary plaque progression by coronary computed tomography angiography. Cardiovasc Res 2020;116:479–482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bhatt DL, Miller M, Brinton EA, Jacobson TA, Steg PG, Ketchum SB, Doyle RT, Juliano RA, Jiao L, Granowitz C, Tardif J-C, Olshansky B, Chung MK, Gibson CM, Giugliano RP, Budoff MJ, Ballantyne CM, On behalf of the REDUCE-IT Investigators. REDUCE-IT USA: results from the 3,146 patients randomized in the United States. Circulation 2020;141:367–375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mason RP, Libby P, Bhatt DL. Emerging mechanisms of cardiovascular protection for the omega-3 fatty acid eicosapentaenoic acid. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2020;40:1135–1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Boden WE, Bhatt DL, Toth PP, Ray KK, Chapman MJ, Lüscher TF. Profound reductions in first and total cardiovascular events with icosapent ethyl in the REDUCE-IT trial: why these results usher in a new era in dyslipidaemia therapeutics. Eur Heart J 2020;41:2304–2312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bhatt DL. REDUCE-IT. Eur Heart J 2019;40:1174–1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Knuuti J, Wijns W, Saraste A, Capodanno D, Barbato E, Funck-Brentano C, Prescott E, Storey RF, Deaton C, Cuisset T, Agewall S, Dickstein K, Edvardsen T, Escaned J, Gersh BJ, Svitil P, Gilard M, Hasdai D, Hatala R, Mahfoud F, Masip J, Muneretto C, Valgimigli M, Achenbach S, Bax JJ, ESC Scientific Document Group. 2019 ESC Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes: the Task Force for diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2020;41:407–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Saraste A, Barbato E, Capodanno D, Edvardsen T, Prescott E, Achenbach S, Bax JJ, Wijns W, Knuuti J. Imaging in ESC clinical guidelines: chronic coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2019;20:1187–1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mach F, Baigent C, Catapano AL, Koskinas KC, Casula M, Badimon L, Chapman MJ, De Backer GG, Delgado V, Ference BA, Graham IA, Halliday A, Landmesser U, Mihaylova B, Pedersen TR, Riccardi G, Richter DJ, Sabatine MS, Taskinen MR, Tokgozoglu L, Wiklund O, ESC Scientific Document Group. 2019 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk: the Task Force for the management of dyslipidaemias of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS). Eur Heart J 2020;41:111–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]