Abstract

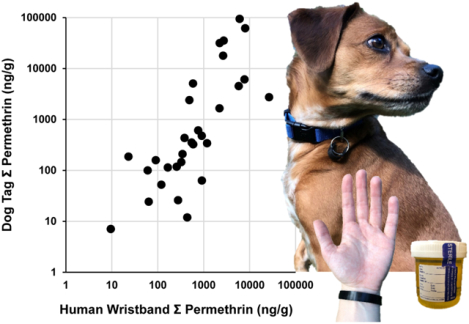

Silicone wristbands are promising passive samplers to support epidemiology studies in characterizing exposure to organic contaminants; however, investigating associated health risks remains challenging due to the latency period for many chronic diseases that take years to manifest. Dogs provide valuable insights as sentinels for exposure-related human disease because they share similar exposures in the home, have shorter lifespans, share many clinical/biological features, and have closely related genomes. Here, we evaluated exposures among pet dogs and their owners using silicone dog tags and wristbands to determine if contaminant levels were correlated with validated exposure biomarkers. Significant correlations between measures on dog tags and wristbands were observed (rs = 0.38–0.90; p <0.05). Correlations with their respective urinary biomarkers were stronger in dog tags compared to human wristbands (rs = 0.50–0.71; p <0.01) for several organophosphate esters. This supports the value of using silicone bands with dogs to investigate health impacts on humans from shared exposures.

Keywords: Exposure assessment, Wristband sampling, Silicone wristbands, Biomonitoring, Passive sampling device, Dog

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Environmental chemical exposures have increased over the past several decades due to changes in building designs, flammability standards and changes in consumer product use, and there is increasing evidence that suggests these chemicals in the natural and built environment may play a role in chronic disease etiology1, 2. It is difficult to dissect the role of exposure in associated health outcomes due to challenges in making accurate exposure measurements, particularly for chemicals that are rapidly metabolized. Semi-volatile organic compounds (SVOCs) are particularly challenging to assess because they are often ubiquitous pollutants with a broad range of chemical properties and structural variations. These include polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), per- and polyfluorinated alkyl substances (PFASs), polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs), polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), organophosphate esters (OPEs), pesticides, and phthalates. Exposure to these chemicals often occurs as mixtures, which makes laboratory animal based exposure studies difficult to recreate in order to mimic environmentally relevant exposures.

Recently, silicone wristbands have been proposed and used as personal passive exposure monitoring devices. The silicone can potentially absorb chemicals similar to the way that uptake occurs in membranes of human cells, and are thought to reflect exposures occurring via inhalation and dermal pathways3, 4. Silicone wristbands capture exposures for a diverse array of chemicals and the levels detected correlate well with serum biomarkers5 and urinary metabolites6, 7, generally outperforming traditional methods such as hand wipes7 and active air monitoring with pumps and air samplers (i.e., polyurethane foam and filter) housed in backpacks6, 8. A recent study reported that passive air sample and wristband measurements of PAHs are significantly correlated and both can be correlated with the proximity to natural gas extraction sites9. Wristband methods offer a unique non-invasive, cost effective opportunity to monitor multi-class exposure on a large scale. However, extrapolations to health outcomes remain a significant challenge due to disease latency, but wristbands may help address this problem. Wristbands have the ability to evaluate exposures over time as they provide average integrated measures of exposure over time (e.g. for several days while wearing the wristbands) and can be more conveniently used in longitudinal studies to measure changes in exposure over months to years instead of trying to collect repeated urine or blood samples over time.

Studies have shown that over 360 diseases diagnosed in the domestic dog, including a wide range of cancers, are analogous to human diseases10. The value of pet dogs as appropriate spontaneous disease models is augmented by our shared genomics and daily environment, which combine to provide a unique opportunity to examine the interactions between genetics and environmental exposures. In terms of cancers, only 5–10 percent of diagnoses are attributable to genetics alone2, 11, and therefore, studies of spontaneous cancers in dogs may provide further insights into the contributions of environmental factors on these disease processes. A variety of environmental risk factors (e.g. diet, environmental chemicals and excessive sunlight exposure) have been documented to be major contributors to cancer etiology12,13. For example, mammary adenocarcinoma is associated with exposure to certain PCBs in both dogs and humans14. Testicular cancer rates in military working dogs and their handlers in Vietnam were higher than their non-veteran counterparts, which is believed to be associated with exposure to pesticides and components of Agent Orange15. Dogs and humans in the same urban area had similarly high incidences of bladder cancer, which correlated with increased industrial activity16. Increased incidence of lymphoma in dogs residing in high risk areas (in close proximity to illegal waste dumping sites) were also seen in humans, but not in cats17. Investigating these links in the domestic dog may provide insight into the etiology, trends and prevention of important cancer outcomes.

In the present study, we assessed parallel exposure levels in paired people and their pet dogs living in the same household, using silicone passive samplers, as well a non-invasive liquid biopsy specimens (free catch urine). The objectives of this study were two-fold, (1) determine if exposures measured via silicone dog tags and their human companion wristbands are similar, and (2) evaluate the extent to which silicone dog tags are indicative of internal dose for dogs, as they are for humans. We established a reliable method to assess cross species exposure levels and a framework to assess multiple classes of compounds. Using this approach we were able to directly compare 51 compounds across human and dog pairs, including nine PBDEs, two novel brominated flame retardants (BFRs), five PCBs, eighteen OPEs, eight pesticides and nine phthalates. These chemicals are ubiquitous contaminants in indoor air and dust. To our knowledge this is the first study to directly measure and compare environmental exposures in dogs and their owners.

2. Methods

2.1. Study population

Study participants (n=30) were recruited through recruitment letters and word of mouth in July through August 2018. Participants were considered eligible for the study if they were at least 18 years old and owner of a dog who would also partake in the study. They also had to be willing to wear a wristband and have their dog wear a silicone tag for five days, to collect three urine samples from both themselves and their dog, and to complete a questionnaire. Owners provided informed consent prior to sample collection. All study protocols and associated materials were approved by the Duke University Institutional Review Board. The study cohort comprised 30 households, 27 around Durham and Wake County, North Carolina, and three in New Jersey.

2.2. Sample collection

Participants were asked to wear a silicone wristband and place a silicone dog tag on their dog’s collar for a full 5-day period (Figure 1). During the study period, participants were asked to collect urine samples from themselves and from their dogs on days 1, 3 and 5 at first morning void in standard polypropylene specimen containers. Clean aluminum foil containers were provided to aid in the urine collection from pet dogs. Urine was stored frozen at their home until transport or shipment to our laboratory, then stored at −20°C until extraction.

Figure 1.

Silicone monitoring devices.

(a) Wristband for human (b) Dog tag affixed to dog collar.

2.3. Urine sample processing

Prior to analysis, equal volumes of the three individual urine samples were combined to form a pooled or average urine sample. This pooled sample was centrifuged for 5 min at 3000 rpm to pellet the cells. Specific gravity of each centrifuged sample was measured using a digital handheld refractometer (Atago UG-α). Each pooled urine samples was analyzed for bis(1-chloro-2-isopropyl) 1-hydroxy-2-isopropyl phosphate (BCIPHIPP), bis(1,3-dichloroisopropyl) phosphate (BDCIPP), diphenyl phosphate (DPHP), isopropylphenyl phenyl phosphate (ip-PPP), and tert-butylphenyl phenyl phosphate (tbutyl-DPP), based on previously published methods7. Briefly, 5 mL aliquots of urine were spiked with d10-BDCIPP (10 ng), d10-DPHP (8.8 ng), and d16-ip-PPP (100 ng). Sodium acetate buffer (1.0 M, pH 5.0) and an enzyme solution (1000 units/mL β-glucoronidase and 33 units/mL sulfatase activity in 0.2 M sodium acetate at pH 5.0) were added to the urine samples and vortexed. The samples were incubated overnight in a water bath at 37°C. Samples were then extracted using mixed-mode anion-exchange solid-phase extraction and analyzed by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (Agilent Technologies Model 6460). The method detection limit (MDL) was calculated using three times the standard deviation of the blanks normalized to the volume of urine extracted. Lab blanks (n=6) and urine standard reference materials (n=6) (SRM 3673; NIST, Gaithersburg, MD) were extracted and analyzed alongside the samples for quality assurance and control.

2.4. Wristband sample processing

All wristbands were prepared and processed according to our previously published methods5, 7. Briefly, silicone wristbands (24hourwristbands.com, Houston, TX) were solvent cleaned in three different organic solvents prior to distribution to study participants. Prior to cleaning dog tags were prepared by cutting a wristband to one-fourth the size and affixing them to a metal key ring to allow for easy attachment to a dog collar. At the end of the study period, participants removed their wristband and the collar tag from their dog, placed them in separate clean pieces of aluminum foil. The silicone band and tags were sealed in an air tight bag and stored in a domestic freezer until transport or shipment back to the laboratory. Silicone wrist bands and dog tags used as field blanks were treated the same way except they remained stored in foil at room temperature in the laboratory. All wristbands and tags were stored in −20°C until extraction, which was no longer than 4 months for any sample.

Prior to processing, each dog tag was cut in half and each wristband was cut into similarly sized pieces (ranging from 0.6–0.9g) for extraction. Individual pieces were weighed and then placed in a glass tube, spiked with a suite of isotopically labeled compounds (Table S1.) and extracted in 10 mL of a 50:50 (v:v) mixture of hexane:dichloromethane in a 15 minutes sonication extraction. This step was repeated three times for a total extraction volume of 30 mL. Prior to column chromatography extracts were concentrated to ~1.0 mL with nitrogen gas using a Savant SPD121P SpeedVac™ Concentrator (Thermo Scientific). Extracts were cleaned using 8.0 g deactivated Florasil® (Acros Organics™ Florisil™, 100–200 mesh, FisherScientific). Three fractions were collected, F1, F2, and F3 using elution solvents hexane, ethyl acetate, and methanol, respectively. F1 and F2 were combined and concentrated to 1.0 mL using an automated nitrogen evaporation system (TurboVap II, Zymark Inc.). Samples were concentrated to near dryness and reconstituted in 1.0 mL hexane. A suite of isotopically labelled (Table S2) recovery standards were spiked into each sample prior to mass spectrometry analysis. The average percent recovery across all surrogate standards was 68 ± 22%. The average recovery for each individual labelled compounds can be found in Table S1. Samples were analyzed for a suite of target compounds using a Q Exactive GC hybrid quadrupole-Orbitrap GC-MS/MS system (Thermo Scientific) operated in full scan in full scan Electron Ionization (EI) mode. Samples were analyzed for brominated flame retardants using a single quadrupole GC-MS (Agilent 6890N and 5975, respectively) operated in negative chemical ionization (NCI) mode. Field blanks (n=8, four wristbands and four dog tags) and lab blanks (n=7) were processed and analyzed with each batch of wristbands for quality control and quality assurance. Method detection limits were based on the field blanks if analytes were detected in field blanks, using three times the standard deviation of the field blank responses, or equal to 10 times a signal to noise value if the analyte was not detected in the field blanks.

2.5. Questionnaires

All 30 study participants completed a short questionnaire during the study period (Supplementary Material). The questionnaire was designed to obtain brief demographic data, information regarding lifestyle factors for the human and dog, and information about their shared home. Participants were also asked to record the exact times that wristbands and dog tags were put on and taken off and all urine collection times.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Quality control was performed prior to statistical analysis. Based on thresholds in previous studies, chemicals with detection frequencies < 50% for either the human wristband or dog tags were removed from downstream analysis6, 18. Urine concentrations were normalized to specific gravity to account for differences in urine dilution. For samples that had concentrations that were below the MDL, the values were replaced with one half of the MDL before adjusting for sample specific gravity or wristband mass, in concordance with previously established best practices19. Chemical concentrations were log transformed to better meet normality assumptions for regression analyses.

Simple linear regression was used to identify significantly correlated chemicals within and across species. Specifically, we used simple linear regression models to explore the relationship between human chemicals (independent variables) and dog chemicals (dependent variables) for each chemical group. Hypothesis testing was used to test for the correlation of chemical concentrations between dog wristband and human wristband, between dog urine and human urine, between dog wristband and dog urine (OPEs only), and between human wristband and human urine (OPEs only). The relationships between specific wristband parent compounds and their corresponding urinary metabolites are as follows: TCIPP-BCIPPHIPP; TDCIPP-BDCIPP; TPHP-DPHP.

Multiple testing correction was performed using the Benjamini-Hochberg False Discovery Rate (FDR)20. A FDR of 0.05 was used to ascribe statistical significance. Additionally, sensitivity analyses of urine metabolites were conducted using both uncorrected urine data and specific gravity (SG) corrected data to test if using the raw data vs the specific gravity corrected data change any of the results.

Spearman’s rank-order correlations across and within species were calculated to assess the magnitude of associations between of chemical concentrations between wristbands and dog tags and between the silicone samplers and biomarkers (for OPEs). Moreover, multiple linear regression was performed to test any impact of covariates (from the questionnaire data) on the relationship between dog and human chemical levels, as well as wristband parent compounds and urine metabolites for each species. Questionnaire variables were individually included in the multiple regression models. Hypothesis testing and multiple testing correction (FDR<0.05) were used to ascribe significance for the covariate terms. Tukey’s honestly significant difference test (Tukey’s HSD) was used to assess location covariates for Durham county (n=7) compared to Wake county (n=16) participants.

A sensitivity analysis of urinary metabolites were performed using raw values and specific gravity corrected values. No differences were observed in the final results using either method. Data and analyses presented here represent specific gravity corrected values.

All analyses were performed in the R programming language21.

3. Results

3.1. Study Population

All data presented here are from 30 human-dog pairs and comprised 30 wristbands (human), 30 collar tags (dog), both worn for five consecutive days, 180 urine samples (three urine samples from each human and dog) and a completed study questionnaire. Urine samples were collected as first void on days 1, 3 and 5 and pooled per individual to form a composite sample representing an average over the study period. Participants either lived in North Carolina (n=27) or New Jersey (n=3). At the time of sampling, the average age of the 30 human participants was 37.8 years (range 25–63 years), with 11 males (37%) and 19 females (63%). The average age of the 30 canine participants was 6 years (range 1.5–12.9 years), with 18 males (60%) and 12 females (40%) (Table 1). The majority of dogs (53%) were reported as pure breed dogs and no single breed was represented more than twice. All dogs, except for one male dog, were neutered or spayed.

Table 1.

Questionnaire Data

| Shared | ||

|---|---|---|

| Variables | n (%) | |

| Age of home | ||

| <12 months | 1 (3) | |

| 6–10 years | 5 (17) | |

| 11–20 years | 7 (23) | |

| 21–50 years | 12 (40) | |

| >50 years | 5 (17) | |

| Type of home | ||

| Apartment/Condo | 3 (10) | |

| Townhouse | 2 (7) | |

| Single detached home | 25 (83) | |

| Use of Lawn pesticides/herbicides | ||

| Yes | 14 (47) | |

| No | 10 (33) | |

| Unknown | 4 (13) | |

| Use of In Home pesticides/herbicides | ||

| Yes | 9 (30) | |

| No | 20 (67) | |

| Unknown | 1 (3) | |

| Individual | ||

| Human | Dog | |

| Age | (years) | (years) |

| Average | 38 | 6 |

| Minimum | 25 | 1.5 |

| Maximum | 63 | 13 |

| Weight | (kg) | (kg) |

| Average | NR | 24.5 |

| Minimum | NR | 6.8 |

| Maximum | NR | 52.2 |

| n (%) | n (%) | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 11(37) | 18 (60) |

| Female | 19 (63) | 12 (40) |

| Hours inside home | ||

| < 6 hours | 1 (3) | 0 (0) |

| 7–12 hours | 15 (50) | 1 (3) |

| 13–18 hours | 13 (43) | 7 (23) |

| 19–24 hours | 1 (3) | 22 (73) |

| Years lived in home | ||

| < 6 months | 4 (13) | 5 (17) |

| 6–11 months | 2 (7) | 2 (7) |

| 1–2 years | 7 (23) | NR |

| 1–3 years | NR | 12 (40) |

| 3–4 years | 7 (23) | NR |

| 4–8 years | NR | 9 (30) |

| 5–6 years | 2 (7) | NR |

| 7 or more years | 8 (27) | NR |

| 9 or more years | NR | 2 (7) |

| Amount of exercise | ||

| None or scarce activity (0–1 hour) | NR | 0 (0) |

| Moderate outdoor activity (1–2 hours) | NR | 9 (30) |

| Regular outdoor activity (2–5 hours) | NR | 13 (43) |

| Intensive outdoor activity (>5 hours) | NR | 8 (27) |

| Frequency of Urination (per day) | ||

| 1–3 times | NR | 3 (10) |

| 4–6 times | NR | 20 (67) |

| 7–9 times | NR | 5 (17) |

| 10 or more times | NR | 2 (7) |

| Hours between voiding bladder | ||

| < 1 hour | NR | 2 (7) |

| > 1 hour but < 3 hours | NR | 0 (0) |

| > 3 hours but < 6 hours | NR | 6 (20) |

| > 6 hours | NR | 22 (73) |

Not reported (NR)

3.2. Urine measures

Method detection limits (MDL), detection frequency and geometric means for all OPE metabolites measured in urine are shown in Table 1 (Only OPE metabolites were measured in urine in this study). Detection frequencies were similarly high between species for BCIPHIPP, BDCIPP, DPHP and ip-PPP, and detection frequencies for tbutyl-DPP were 97% and 33% for dogs and humans, respectively. Dogs had higher levels of BCIPHIPP measured in urine and humans had higher levels of ip-PPP measured in urine. Similar levels of DPHP and BDCIPP were detected in both species. There were no significant correlations between dog and human urinary metabolites although, DPHP had a Spearman’s correlation coefficient of 0.34 (p=0.07) and was suggestive of a trend.

3.3. Wristband measures

Of the 68 chemicals measured in extracts of the silicone bands/tags, 66 (97%) were detected in at least one wristband/tag, 51 (75%) were detected in ≥50% for at least one species, and 41 (60%) were detected in ≥50% of both species. PCB183 and tri-n-butyl phosphate (TnBP) were below detectable limits in any wristbands/tags. Method detection limits, detection frequency and geometric means for all compounds measured on the wristbands/dog tags are shown in Table 2. Detection frequencies for TCEP, PCB52, PCB118 and cypermethrin were 87%, 63%, 50% and 77%, respectively, for humans but were below 50% in dogs. Detection frequencies for 2tBPDPP, B24DIPPPP, PCB47 and lindane were 73%, 100%, 60% and 50%, respectively for dogs, but were below 50% in humans.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics for Chemicals Measured In Wristbands and Dog-Tags and Urine.

| Urinary Metabolite (ng/mL) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Humans | Dogs | Spearman correlations | |||||||

| DF (%) | MDL | GM | MAX | DF (%) | MDL | GM | MAX | rs | |

| Organophosphate Esters | |||||||||

| BCIPHIPP | 87 | 0.001 | 0.04 | 0.2 | 90 | 0.023 | 0.3 | 13.4 | −0.09 |

| BDCIPP | 100 | 0.001 | 1.5 | 11.7 | 100 | 0.004 | 1.9 | 12.0 | 0.16 |

| DPHP | 100 | 0.075 | 2.2 | 8.8 | 100 | 0.023 | 2.0 | 9.7 | 0.34 |

| ip-PPP | 100 | 0.030 | 1.6 | 5.3 | 100 | 0.004 | 0.2 | 1.4 | −0.01 |

| tbutyl DPP* | 33 | 0.001 | N/A | 1.3 | 96.7 | 0.004 | 0.4 | 3.0 | N/A |

| Wristband and Dog-tag Analyte (ng/g) | |||||||||

| Humans | Dogs | ||||||||

| DF (%) | MDL | GM | MAX | DF (%) | MDL | GM | MAX | rs | |

| Organophosphate Esters | |||||||||

| TCEP* | 87 | 1.376 | 7.6 | 127.5 | 30 | 6.652 | 6.7 | 46.9 | N/A |

| TDCIPP | 100 | 0.399 | 455.7 | 2820.5 | 100 | 4.616 | 75.9 | 1439.0 | 0.09 |

| TCIPP | 100 | 2.167 | 279.7 | 10208.4 | 97 | 6.003 | 155.7 | 7917.6 | 0.48b |

| TBoEP | 100 | 23.902 | 222.6 | 4169.1 | 50 | 88.410 | 85.3 | 2283.4 | 0.45a |

| TPHP | 100 | 4.135 | 280.7 | 3195.7 | 100 | 5.335 | 67.6 | 646.3 | 0.43a |

| EHDPP | 100 | 0.038 | 38.7 | 469.4 | 100 | 0.566 | 9.5 | 262.3 | 0.06 |

| 2IPPDPP | 100 | 3.066 | 153.0 | 2156.1 | 100 | 3.977 | 39.1 | 725.8 | 0.66c |

| 3IPPDPP | 100 | 0.088 | 17.2 | 390.8 | 100 | 0.168 | 4.3 | 79.9 | 0.43a |

| 2tBPDPP* | 47 | 0.005 | 0.02 | 0.7 | 73 | 0.021 | 0.2 | 8.2 | N/A |

| B2IPPPP | 100 | 0.714 | 58.9 | 745.9 | 100 | 0.924 | 22.4 | 167.6 | 0.4a |

| 4IPPDPP | 100 | 0.867 | 60.9 | 994.3 | 100 | 1.187 | 12.3 | 272.7 | 0.71c |

| 24DIPPDPP | 93 | 0.557 | 32.5 | 805.9 | 97 | 1.281 | 14.6 | 240.5 | 0.64c |

| 4tBPDPP | 100 | 0.032 | 48.0 | 353.9 | 100 | 0.473 | 7.9 | 53.8 | 0.61b |

| B3IPPPP | 73 | 0.170 | 1.2 | 60.2 | 100 | 1.048 | 14.2 | 248.2 | 0.60b |

| B4IPPPP | 96.7 | 0.088 | 7.6 | 341.9 | 77 | 0.105 | 1.0 | 45.7 | 0.78c |

| B24DIPPPP* | 0 | 0.352 | N/A | N/A | 100 | 2.491 | 30.6 | 122.4 | N/A |

| B4tBPPP | 100 | 0.004 | 15.4 | 127.2 | 93 | 0.161 | 2.6 | 32.4 | 0.60b |

| T4tBPPP | 97 | 0.008 | 1.1 | 12.5 | 63 | 0.003 | 0.04 | 8.7 | 0.49b |

| Brominated Flame Retardants | |||||||||

| BDE 28,33 | 100 | 0.287 | 1.7 | 23.7 | 77 | 0.287 | 1.1 | 49.2 | 0.78c |

| BDE 47 | 100 | 0.715 | 39.5 | 147.7 | 100 | 0.715 | 17.1 | 3278.4 | 0.64b |

| BDE 100 | 97 | 0.383 | 4.5 | 25.3 | 83 | 0.383 | 2.2 | 919.1 | 0.54a |

| BDE 138 | 100 | 0.100 | 0.9 | 1.6 | 83 | 0.100 | 0.4 | 47.2 | 0.39a |

| BDE 153 | 100 | 0.100 | 2.0 | 7.1 | 73 | 0.100 | 0.7 | 451.9 | 0.71c |

| BDE 154 | 100 | 0.100 | 1.5 | 6.4 | 67 | 0.100 | 0.5 | 389.1 | 0.60b |

| BDE 181 | 93 | 1.327 | 25.2 | 48.3 | 100 | 1.327 | 12.2 | 33.8 | 0.15 |

| BDE 183* | 57 | 0.100 | 1.6 | 13.2 | 10 | 0.100 | N/A | 9.9 | N/A |

| BDE 209* | 77 | 4.393 | 10.6 | 74.5 | 37 | 4.393 | N/A | 20.6 | N/A |

| EH-TBB | 100 | 0.892 | 140.2 | 24792.0 | 100 | 0.892 | 35.9 | 2120.4 | 0.75c |

| BEH-TEBP | 100 | 0.444 | 105.7 | 1209.4 | 100 | 0.444 | 21.4 | 824.8 | 0.37a |

| Polychlorinated Biphenyls | |||||||||

| PCB28 | 87 | 0.009 | 0.2 | 5.8 | 97 | 0.014 | 0.2 | 3.0 | 0.79c |

| PCB47* | 40 | 0.043 | 0.05 | 1.3 | 60 | 0.026 | 0.07 | 48.4 | N/A |

| PCB52* | 63 | 0.030 | 0.1 | 2.3 | 43 | 0.064 | 0.1 | 12.9 | N/A |

| PCB101 | 67 | 0.018 | 0.1 | 11.9 | 50 | 0.022 | 0.09 | 35.5 | 0.67c |

| PCB118* | 50 | 0.021 | 0.06 | 7.3 | 43 | 0.010 | 0.04 | 32.8 | N/A |

| Pesticides | |||||||||

| Lindane* | 27 | 0.007 | 0.01 | 3.1 | 50 | 0.019 | 0.1 | 9.5 | N/A |

| Chlorpyrifos | 83 | 0.052 | 1.0 | 24.9 | 70 | 0.048 | 0.6 | 37.8 | 0.90c |

| Trans-Chlordane | 93 | 0.017 | 4.2 | 154.6 | 97 | 0.037 | 5.8 | 176.5 | 0.83c |

| Cis-Chlordane | 70 | 0.101 | 1.1 | 43.5 | 83 | 0.036 | 1.8 | 80.7 | 0.85c |

| Trans-Permethrin | 100 | 0.194 | 347.0 | 12191.9 | 100 | 1.916 | 334.7 | 42949.9 | 0.83c |

| Cis-Permethrin | 100 | 0.168 | 254.2 | 14156.0 | 100 | 1.408 | 261.1 | 51549.9 | 0.81c |

| Cypermethrin* | 77 | 1.028 | 5.6 | 158.0 | 27 | 0.466 | 1.1 | 64.1 | N/A |

| Azoxystrobin | 70 | 0.211 | 1.3 | 35.7 | 50 | 0.056 | 0.2 | 358.1 | 0.15 |

| Phthalates | |||||||||

| DMP | 57 | 23.593 | 14.7 | 268.4 | 100 | 19.382 | 54.7 | 616.5 | 0.26 |

| DEP | 100 | 18.163 | 509.7 | 3610.4 | 100 | 13.645 | 487.4 | 1152.8 | 0.50b |

| DiBP | 100 | 6.262 | 1393.0 | 3145.7 | 100 | 10.146 | 1247.0 | 12429.4 | 0.58b |

| DBP | 100 | 80.163 | 997.4 | 6231.4 | 100 | 112.103 | 653.5 | 2461.7 | 0.36a |

| BBP | 100 | 19.056 | 691.2 | 5334.2 | 90 | 39.674 | 263.4 | 27597.1 | 0.36 |

| DEHP | 100 | 217.125 | 11093.9 | 36664.5 | 100 | 322.181 | 5431.5 | 72189.2 | 0.16 |

| DEHT | 100 | 41.360 | 16773.3 | 63689.0 | 100 | 182.462 | 9520.1 | 47572.3 | 0.33 |

| DiNP | 100 | 368.99 | 10422.3 | 30591.5 | 100 | 391.533 | 4435.3 | 20233.0 | 0.35 |

| TOTM | 100 | 0.417 | 670.4 | 3617.2 | 100 | 5.076 | 232.0 | 2215.8 | 0.52a |

Detection frequency (DF), method detection limit (MDL), geometric mean (GM), maximum concentration (MAX), spearman’s rho (rs)

indicates chemicals that have a DF ≥ 50% in one species but DF < 50% in the other, N/A not applicable statistics due to DF <50%

n=30 for all

Urinary metabolite concentrations are specific gravity corrected values

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01;

p <0.0001

Spearman correlation coefficients (rs) for levels measured in paired human and dog samples.

The most abundant OPEs were TBoEP and TPHP and the most abundant chlorinated OPEs were TDCIPP and TCIPP. The most abundant PCB was PCB28, detected in 87% and 97% of human wristbands and dog tags, respectively. The most abundant pesticides and phthalates were trans- and cis-permethrin, and DEHT and DEHP, respectively, all of which were detected in 100% of all wristbands/tags. The most abundant BFRs were TBB, TBPH and BDE-47 which were also detected in 100% of the wristbands and dog tags.

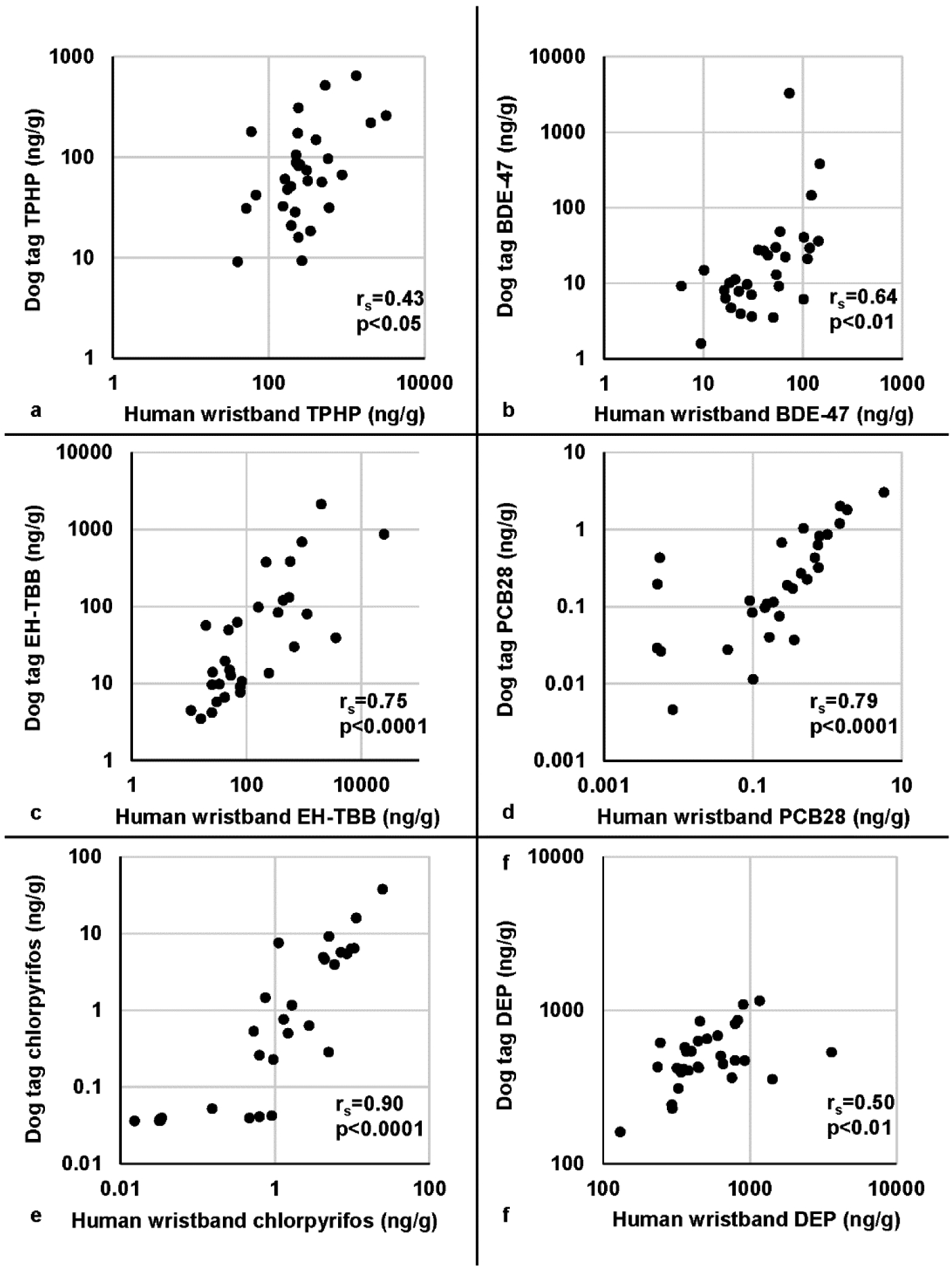

Spearman’s correlations were calculated to estimate the correlation of concentrations measured on wristbands and dog tags (Table 2 and Figure 2). Spearman’s correlation coefficients were calculated for the 41 chemicals that had detection frequencies ≥50% in both species and ranged from 0.06 to 0.9. Of those 41 chemicals, 32 (78%) had significant correlations when tested by linear regression (p<0.05) (Table S3). The relationship of all chemicals is represented as a heatmap of Spearman’s correlation coefficients (Figure S1) to show associations between chemicals within and across species, heatmaps separated by chemical class are shown in Figure S2. There is a strong correlation within and across species between the cis- and trans- isomers of chlordane and permethrin, respectively (Figure S2a.). These heat maps allow us to assess relationships between individual chemicals that often occur as mixtures in consumer products and thus exposure such as several PBDEs and OPEs (Figure S2b.).

Figure 2.

Example scatterplots for each chemical class for paired human wristband and dog tag samples.

Data are log transformed, spearman correlations (rs) and p-values for each association are provided. (a) Triphenyl phosphate (TPHP) (b) Polybrominated diphenyl ether congener 47 (BDE-47) (c) 2-ethylhexyl-2,3,4,5 tetrabromobenzoate (EH-TBB) (d) Polychlorinated biphenyl congener 28 (PCB28) (e) Chlorpyrifos, (f) Diethyl phthalate (DEP).

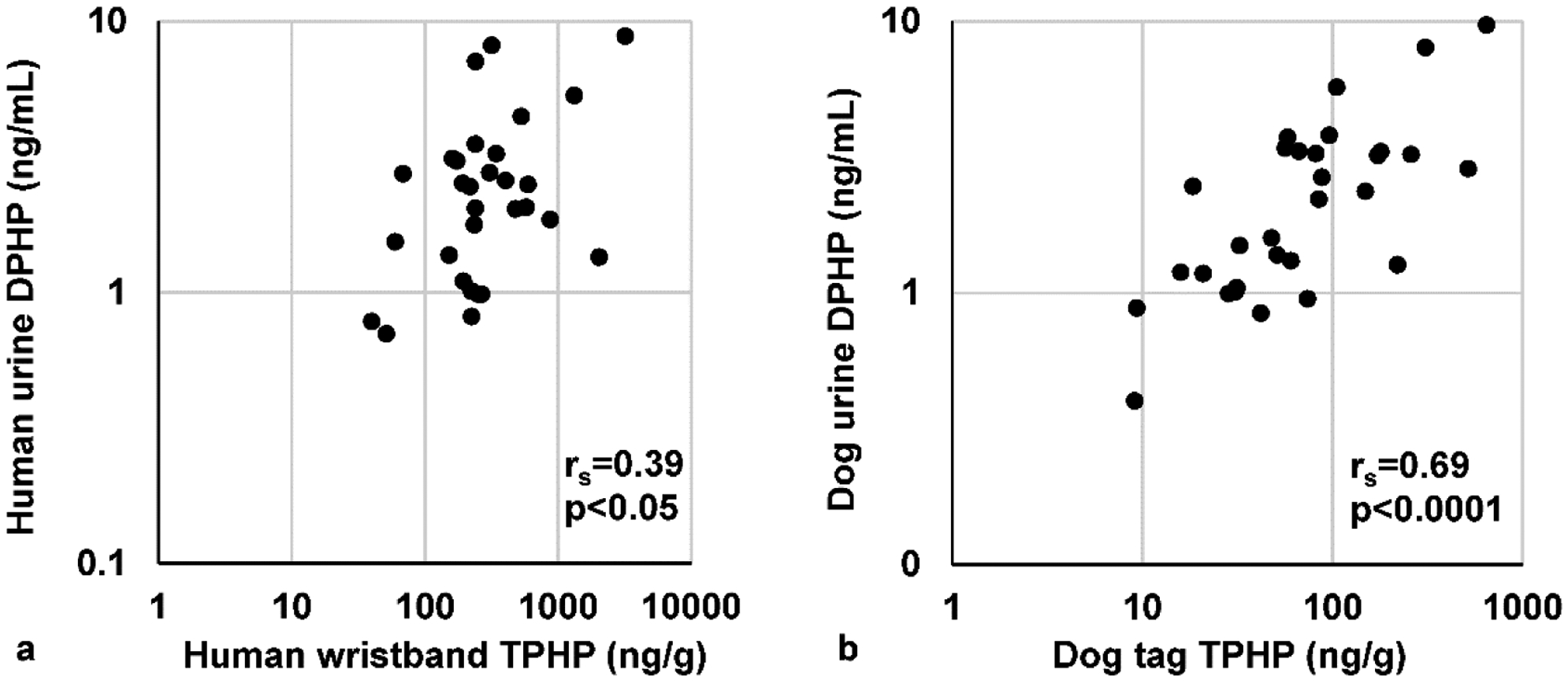

3.4. Comparing Wristband to Urine

Spearman correlations and linear regression analyses were used to determine the relationship between concentrations measured on the wristbands/dog tags and urinary metabolites (Table 3 and Table S4). The levels of TPHP were significantly correlated with its corresponding urinary metabolites for both species (Figure 3). All urinary metabolites measured had greater magnitude of correlation to parent compounds on dog tags compared to human urine and wristbands.

Table 3.

Spearman correlations coefficients for OPE metabolites measured in paired wristband/dog-tag and urine samples.

| Parent Compound | Urinary Metabolite | Humans | Dogs |

|---|---|---|---|

| TCIPP | BCIPHIPP | 0.06 | −0.49b |

| TDCIPP | BDCIPP | 0.24 | 0.71c |

| TPHP | DPHP | 0.39a | 0.69c |

| EHDPP | DPHP | 0.24 | 0.33 |

| B4tBPPP | tbutyl DPP | N/A | 0.50b |

| 2IPPDPP | ip-PPP | −0.12 | 0.76c |

| 3IPPDPP | ip-PPP | −0.10 | 0.59b |

| 2tBPDPP* | ip-PPP | 0.22 | 0.58b |

| B2IPPPP | ip-PPP | −0.03 | 0.63b |

| 4IPPDPP | ip-PPP | −0.08 | 0.71c |

| 24DIPPDPP | ip-PPP | −0.15 | 0.56b |

| 4tBPDPP | ip-PPP | 0.14 | 0.25 |

| B3IPPPP | ip-PPP | 0.05 | 0.72c |

| B4IPPPP | ip-PPP | −0.04 | 0.70c |

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01;

p <0.0001

Figure 3.

Example scatterplots for wristband/dog tag associated with urinary metabolites.

Correlation of triphenyl phosphate (TPHP) measured on the wristbands and dog tags and its urinary metabolite diphenyl phosphate (DPHP) (a) humans (b) dogs. Urinary metabolite concentrations are specific gravity corrected values. Data are log transformed, spearman correlations (rs) and p-values for each association are provided.

4. Discussion

With a combination of shared genomics and pathophysiological similarities to humans, pet dogs offer a powerful opportunity to enhance biomedical studies involving research related to our shared environment and health. In particular, the impact of daily chemical exposures on the dog may serve as a surrogate for the effects on human health outcomes. To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate exposures in humans and pet dogs living in the same household.

The data in this study indicate that silicone dog tags are an effective means to measure exposure in pet dogs. In this study, humans generally had similar levels of exposure to most chemicals measured on their wristbands compared to household matched dog tags. In spite of some chemical concentrations being higher on the wristbands compared to the dog tags, our data revealed that the majority of the target compounds had significant correlations between humans and their pet dogs. These data further support the role of the dog as a valuable One Health model for environmental exposure surveillance22.

In this study, we measured organophosphate esters (OPEs) on wristbands and their metabolites in urine. The data had good consistency with previously published data for urinary OPE metabolites7, 18, 23–30 and Spearman correlations between wristband compounds and their corresponding urinary metabolites for the humans in our study were similar, or in one case smaller (TDCIPP/BDCIPP) in magnitude to previously reported studies7, 18. However, the correlations for the silicone and corresponding urinary metabolites were greater in magnitude for the dogs than the humans in our study and in previous reports7, 18. The high correlation between OPEs measured by the dog tags and urinary metabolites suggests that the tags are a valuable tool for assessing animal exposures for chemicals ubiquitous to the indoor environment, and can be used as a surrogate for urine, which can be challenging for owners to obtain. However, further validation of more chemical classes is needed. Avoiding the need for repeat urine samples and even the need for a veterinary office visit offers the potential to increase owner compliance and thus the breadth of such studies. A recent study using silicone tags to measure exposure to flame retardant chemicals in cats demonstrated that elevated TDCIPP exposure is associated with hyperthyroidism in cats compared to non-hyperthyroid controls and higher levels of TDCIPP correlated to higher levels of thyroid hormones in non-hyperthyroid cats31. The utility of silicone tags to investigate relationships between environmental exposure and health outcomes in pets should be expanded to further elucidate how best our household companions can serve as sentinels for human exposure and disease.

Despite phthalates being the most abundant target compounds captured by both wristbands and dog tags, the most dramatic exposure differences between dogs and their owners was in the actual phthalate concentrations, likely highlighting differences in behavior (e.g., time spend in different micro-environments) and proximity to consumer products. Higher levels of di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP) in humans compared to their dogs may represent increased exposure for humans due to the use of plastic food packaging products32 or time spent in an automobile33. All sampling for this study was done during the peak of summer in North Carolina, and the higher temperatures inside personal vehicles has been shown to increase the volatilization of phthalates34, 35. Dimethyl phthalate (DMP) was the only phthalate measured at higher levels for dogs than humans, suggesting an exposure more unique to the dog’s microenvironment. This could be related to the use of flea and tick products on the dog, although since the inactive ingredients are often a proprietary mixture, it would be impossible to evaluate. Pairwise comparisons of chemicals detected across counties revealed a significant difference in the level of DBP (p=0.027) between dogs Durham and Wake counties. No other comparison was significant.

The most abundant PBDE congener measured in all silicone-based exposure assessment studies published to date is BDE-475, 27, 28. Hammel et al. reported significant correlations between wristband measurements of BDE-47 and human serum levels of BDE-47. There are few studies assessing exposure in dogs, but one study in Pakistan reported the most significant BDE measured in dog and human serum was BDE-4736. Although these passive monitoring devices have not been used with dogs before, our dog tag data are consistent with several studies that have measured PBDEs in serum and tissues of dogs in which BDE-47 is one of the most abundant congeners measured37–40. We would therefore hypothesize that serum levels of BDE-47 would be correlated with the dog tags; however, further validation studies are needed to confirm this. BDE-209 levels were similar to those previously reported5,28 for human wristbands, but the detection frequency was less than 50% in our dog-tags. Interestingly BDE-209 has been reported as one of the more abundant congeners in studies measuring levels in dog tissues39–41. Although this a major congener found in house dust42, 43 it is also, reportedly high in dry dog food40,41. It is possible the high levels of BDE-209 previously reported in dog tissues may be due to higher dietary exposure and thus not captured by the silicone dog tags, although it is also possible that exposure may be decreasing for PBDEs since they have now been phased out of production. In contrast, EH-TBB, BEH-TEBP were the most abundant BFRs measured on the wristbands (GM = 140.2 ng/g and 105.7 ng/g, respectively) and dog tags (GM = 35.9 ng/g and 21.4 ng/g, respectively). The geometric mean of EH-TBB and BEH-TEBP measured on the dog tags in our study were similar to previously reported human wristbands (GM = 43.0 ng/g & 32.6 ng/g, respectively) but the human wristbands in our study had much higher levels5. EH-TBB and BEH-TEBP are components of Firemaster 55044, which has increased in use following the phase-out of PBDEs. EH-TBB and BEH-TEBP were significantly correlated in humans and dogs, rs 0.37 p<0.05 and rs=0.86 p<0.0001, respectively.

Permethrin was detected in high abundance in both our human wristbands and dog tags with significant correlations to each other. The two dogs with the highest levels of permethrin in our study were the only two that reported use of a topical flea and tick preventative which lists permethrin as an active ingredient. Interestingly, Harley et al, reported higher levels of total permethrin levels in wristbands worn by participants that reported having a pet in the home, however there was no statistical significance between levels measured on pet owners and non-pet owners45. An interesting next step would be to compare household exposures in humans, dogs and cats living in the same home.

A summary of relevant literature of chemicals measured on wristbands is shown in Table S5. Considering this is the first report of the use of silicone wristbands in pet dogs, we cannot make any direct comparisons with the literature. One study has used silicone passive monitors for pet cats31 had similar detection frequencies for OPEs as our study, but cats had lower detection frequencies for brominated flame retardants. Environmental exposure assessment studies in domestic dogs lack consensus as to whether dogs are a valuable sentinel species for humans. However, even studies that negate the dog as a quality model for dietary exposures acknowledge that they may be good models for inhalation exposures46–48.

It can be difficult to infer specific routes of exposure for the chemicals measured in silicone wristbands because they are multi-media samplers. A study comparing the utility of silicone wristbands with silicone brooches, hand wipes and active air samplers, showed that using wristbands as exposure monitors integrates individualized dermal and inhalation exposure data4. However, the concurrent measurement of household dogs provides us with insight into which chemicals may originate from variable environments or sources, such as workplace exposures or chemicals in personal care products. Furthermore, human biomonitoring studies to investigate health outcomes often require complex procedures to obtain informed consent and challenges with subject privacy and long study periods for chronic exposures. It is much more difficult to demonstrate causality due to long latency periods, chronic low-dose exposures, multiple exposure routes and non-specific health outcomes. Using pets as surrogates for humans can overcome many of these challenges.

For an animal to be considered a sentinel for human health requires equal or more susceptibility, and/or have greater exposure or risk49. Most studies that investigated relationships between environmental exposures and health outcomes in pet dogs have been based on owner survey data50–52. With reference to suggested associations between chemical exposures and cancer, exposure to lawn herbicides has been associated with an increased risk of urothelial carcinoma53 and studies have linked environmental tobacco smoke exposure with increased risk of lymphoma51. Measured levels of dioxin-like PCB congeners detected in adipose tissue are associated with mammary cancer in dogs14. Canine urothelial carcinoma54, 55, lymphoma56–58 and mammary carcinoma59, 60 all share pathophysiological and molecular similarities with the corresponding disease in humans. Dogs are increasingly being recognized as models for understanding the biology and offering potential for identifying therapeutic targets for these diseases across both species. It is likely, therefore, that assessing the relationship between environmental exposures and disease etiology in dogs will lead to identification of at-risk individuals, which will aid in earlier detection and advance our goals to prevent disease.

Despite the relatively small sample size of this study, our results show that the domestic dog continues to be a critical model organism for comparative biomedical research. This is the first study to use silicone as a passive monitoring device in dogs to target key chemicals in our everyday environment and to show that silicone dog tags have a strong concordance with urinary OPE metabolites. Furthermore, this study is the first to both objectively and simultaneously measure environmental exposures in dogs and humans living in the same household and demonstrate strong similarities. This highlights the utility of silicone wristbands and dog tags as a noninvasive and inexpensive method to assess chemical exposures and health outcomes. The ability to capture a diverse array of chemical exposure simultaneously in multiple species has the potential to greatly expand exposome and environmental epidemiology studies. However, we acknowledge that the wristbands cannot characterize exposures that occurs via dietary pathways, particularly contaminants that may be present in drinking water, and such studies would require alternative approaches.

The higher correlation in pet dogs between parent compounds and their metabolites, combined with a shorter disease latency, suggests that these household members may be an ideal model system to investigate potential links between environmental exposures and health outcomes. The integration of dog and human tandem exposure data may be able to help with the major challenge of determining the exposure source of a measured metabolite. We recognize this study as the first step towards developing a holistic approach to exposome research which can be incorporated with health outcome data.

In summary, we propose that it is imperative to continue to investigate environmental exposure monitoring in pets as a means to better understand and predict how shared environmental exposures will affect human and animal health. In future studies, dogs can wear silicone dog tags to evaluate cancer bearing dogs with breed, age and sex-matched healthy dogs to assess relationships between exposure and health outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank all the people and their dogs that participated in this study. We would like to thank Sharon Zhang for technical support. This study was supported by the NCSU Cancer Genomics Fund (MB, NCSU), the Wallace Genetic Foundation and National Institutes of Health (R01 ES016099) (HMS, Duke), and intramural funds from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (AMR, NIEHS).

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Study questionnaire, figures and tables as detailed in the text.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Bijlsma N; Cohen MM, Environmental Chemical Assessment in Clinical Practice: Unveiling the Elephant in the Room. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2016, 13, (2), 181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rappaport SM, Implications of the exposome for exposure science. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol 2011, 21, (1), 5–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Connell SG; Kerkvliet NI; Carozza S; Rohlman D; Pennington J; Anderson KA, In vivo contaminant partitioning to silicone implants: Implications for use in biomonitoring and body burden. Environ Int 2015, 85, 182–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang S; Romanak KA; Stubbings WA; Arrandale VH; Hendryx M; Diamond ML; Salamova A; Venier M, Silicone wristbands integrate dermal and inhalation exposures to semi-volatile organic compounds (SVOCs). Environ Int 2019, 132, 105104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hammel SC; Phillips AL; Hoffman K; Stapleton HM, Evaluating the Use of Silicone Wristbands To Measure Personal Exposure to Brominated Flame Retardants. Environ Sci Technol 2018, 52, (20), 11875–11885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dixon HM; Scott RP; Holmes D; Calero L; Kincl LD; Waters KM; Camann DE; Calafat AM; Herbstman JB; Anderson KA, Silicone wristbands compared with traditional polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon exposure assessment methods. Anal Bioanal Chem 2018, 410, (13), 3059–3071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hammel SC; Hoffman K; Webster TF; Anderson KA; Stapleton HM, Measuring Personal Exposure to Organophosphate Flame Retardants Using Silicone Wristbands and Hand Wipes. Environ Sci Technol 2016, 50, (8), 4483–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O’Connell SG; McCartney MA; Paulik LB; Allan SE; Tidwell LG; Wilson G; Anderson KA, Improvements in pollutant monitoring: optimizing silicone for co-deployment with polyethylene passive sampling devices. Environ Pollut 2014, 193, 71–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paulik LB; Hobbie KA; Rohlman D; Smith BW; Scott RP; Kincl L; Haynes EN; Anderson KA, Environmental and individual PAH exposures near rural natural gas extraction. Environ Pollut 2018, 241, 397–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shearin AL; Ostrander EA, Leading the way: canine models of genomics and disease. Dis Model Mech 2010, 3, (1–2), 27–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anand P; Kunnumakkara AB; Sundaram C; Harikumar KB; Tharakan ST; Lai OS; Sung B; Aggarwal BB, Cancer is a preventable disease that requires major lifestyle changes. Pharm Res 2008, 25, (9), 2097–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boffetta P; Nyberg F, Contribution of environmental factors to cancer risk. Br Med Bull 2003, 68, 71–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.NCI/NIEHS Cancer and the Environment. https://www.niehs.nih.gov/health/materials/cancer_and_the_environment_508.pdf (May 16, 2019),

- 14.Severe S; Marchand P; Guiffard I; Morio F; Venisseau A; Veyrand B; Le Bizec B; Antignac JP; Abadie J, Pollutants in pet dogs: a model for environmental links to breast cancer. Springerplus 2015, 4, 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hayes HM; Tarone RE; Casey HW, A cohort study of the effects of Vietnam service on testicular pathology of U.S. military working dogs. Mil Med 1995, 160, (5), 248–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pleil JD, Imputing defensible values for left-censored ‘below level of quantitation’ (LoQ) biomarker measurements. J Breath Res 2016, 10, (4), 045001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marconato L; Leo C; Girelli R; Salvi S; Abramo F; Bettini G; Comazzi S; Nardi P; Albanese F; Zini E, Association between waste management and cancer in companion animals. J Vet Intern Med 2009, 23, (3), 564–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gibson EA; Stapleton HM; Calero L; Holmes D; Burke K; Martinez R; Cortes B; Nematollahi A; Evans D; Anderson KA; Herbstman JB, Differential exposure to organophosphate flame retardants in mother-child pairs. Chemosphere 2019, 219, 567–573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pleil J; Risby T; Herbig J, Breath biomonitoring in national security assessment, forensic THC testing, biomedical technology and quality assurance applications: report from PittCon 2016. J Breath Res 2016, 10, (2), 029001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hochberg Y; Benjamini Y, More powerful procedures for multiple significance testing. Stat Med 1990, 9, (7), 811–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Team, R. C. R Core Team, : Vienna, Austria, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Neo JPS; Tan BH, The use of animals as a surveillance tool for monitoring environmental health hazards, human health hazards and bioterrorism. Vet Microbiol 2017, 203, 40–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Butt CM; Congleton J; Hoffman K; Fang M; Stapleton HM, Metabolites of organophosphate flame retardants and 2-ethylhexyl tetrabromobenzoate in urine from paired mothers and toddlers. Environ Sci Technol 2014, 48, (17), 10432–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Butt CM; Hoffman K; Chen A; Lorenzo A; Congleton J; Stapleton HM, Regional comparison of organophosphate flame retardant (PFR) urinary metabolites and tetrabromobenzoic acid (TBBA) in mother-toddler pairs from California and New Jersey. Environ Int 2016, 94, 627–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.He C; Toms LL; Thai P; Van den Eede N; Wang X; Li Y; Baduel C; Harden FA; Heffernan AL; Hobson P; Covaci A; Mueller JF, Urinary metabolites of organophosphate esters: Concentrations and age trends in Australian children. Environ Int 2018, 111, 124–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoffman K; Garantziotis S; Birnbaum LS; Stapleton HM, Monitoring indoor exposure to organophosphate flame retardants: hand wipes and house dust. Environ Health Perspect 2015, 123, (2), 160–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kile ML; Scott RP; O’Connell SG; Lipscomb S; MacDonald M; McClelland M; Anderson KA, Using silicone wristbands to evaluate preschool children’s exposure to flame retardants. Environ Res 2016, 147, 365–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Romanak KA; Wang S; Stubbings WA; Hendryx M; Venier M; Salamova A, Analysis of brominated and chlorinated flame retardants, organophosphate esters, and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in silicone wristbands used as personal passive samplers. J Chromatogr A 2019, 1588, 41–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van den Eede N; Heffernan AL; Aylward LL; Hobson P; Neels H; Mueller JF; Covaci A, Age as a determinant of phosphate flame retardant exposure of the Australian population and identification of novel urinary PFR metabolites. Environ Int 2015, 74, 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.He C; English K; Baduel C; Thai P; Jagals P; Ware RS; Li Y; Wang X; Sly PD; Mueller JF, Concentrations of organophosphate flame retardants and plasticizers in urine from young children in Queensland, Australia and associations with environmental and behavioural factors. Environ Res 2018, 164, 262–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Poutasse CM; Herbstman JB; Peterson ME; Gordon J; Soboroff PH; Holmes D; Gonzalez D; Tidwell LG; Anderson KA, Silicone Pet Tags Associate Tris(1,3-dichloro-2-isopropyl) Phosphate Exposures with Feline Hyperthyroidism. Environ Sci Technol 2019, 53, (15), 9203–9213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.ATSDR Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry: Toxicological profile for di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate (DEHP). . http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/toxprofiles/tp9.pdf. (Sept. 19), [PubMed]

- 33.Geiss O; Tirendi S; Barrero-Moreno J; Kotzias D, Investigation of volatile organic compounds and phthalates present in the cabin air of used private cars. Environ Int 2009, 35, (8), 1188–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liang Y; Xu Y, Emission of phthalates and phthalate alternatives from vinyl flooring and crib mattress covers: the influence of temperature. Environ Sci Technol 2014, 48, (24), 14228–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ma J; Chen LL; Guo Y; Wu Q; Yang M; Wu MH; Kannan K, Phthalate diesters in airborne PM(2.5) and PM(10) in a suburban area of Shanghai: seasonal distribution and risk assessment. Sci Total Environ 2014, 497-498, 467–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ali N; Malik RN; Mehdi T; Eqani SA; Javeed A; Neels H; Covaci A, Organohalogenated contaminants (OHCs) in the serum and hair of pet cats and dogs: biosentinels of indoor pollution. Sci Total Environ 2013, 449, 29–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lau G; Walter K; Kass P; Puschner B, Comparison of polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) in the serum of hypothyroxinemic and euthyroid dogs. PeerJ 2017, 5, e3780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lea RG; Byers AS; Sumner RN; Rhind SM; Zhang Z; Freeman SL; Moxon R; Richardson HM; Green M; Craigon J; England GC, Environmental chemicals impact dog semen quality in vitro and may be associated with a temporal decline in sperm motility and increased cryptorchidism. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 31281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nomiyama K; Takaguchi K; Mizukawa H; Nagano Y; Oshihoi T; Nakatsu S; Kunisue T; Tanabe S, Species- and Tissue-Specific Profiles of Polybrominated Diphenyl Ethers and Their Hydroxylated and Methoxylated Derivatives in Cats and Dogs. Environ Sci Technol 2017, 51, (10), 5811–5819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Venier M; Hites RA, Flame retardants in the serum of pet dogs and in their food. Environ Sci Technol 2011, 45, (10), 4602–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mizukawa H; Nomiyama K; Nakatsu S; Yamamoto M; Ishizuka M; Ikenaka Y; Nakayama SMM; Tanabe S, Anthropogenic and Naturally Produced Brominated Phenols in Pet Blood and Pet Food in Japan. Environ Sci Technol 2017, 51, (19), 11354–11362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stapleton HM; Dodder NG; Offenberg JH; Schantz MM; Wise SA, Polybrominated diphenyl ethers in house dust and clothes dryer lint. Environ Sci Technol 2005, 39, (4), 925–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Suzuki G; Kida A; Sakai S; Takigami H, Existence state of bromine as an indicator of the source of brominated flame retardants in indoor dust. Environ Sci Technol 2009, 43, (5), 1437–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stapleton HM; Allen JG; Kelly SM; Konstantinov A; Klosterhaus S; Watkins D; McClean MD; Webster TF, Alternate and new brominated flame retardants detected in U.S. house dust. Environ Sci Technol 2008, 42, (18), 6910–6916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Harley KG; Parra KL; Camacho J; Bradman A; Nolan JES; Lessard C; Anderson KA; Poutasse CM; Scott RP; Lazaro G; Cardoso E; Gallardo D; Gunier RB, Determinants of pesticide concentrations in silicone wristbands worn by Latina adolescent girls in a California farmworker community: The COSECHA youth participatory action study. Sci Total Environ 2019, 652, 1022–1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kunisue T; Nakanishi S; Watanabe M; Abe T; Nakatsu S; Kawauchi S; Sano A; Horii A; Kano Y; Tanabe S, Contamination status and accumulation features of persistent organochlorines in pet dogs and cats from Japan. Environ Pollut 2005, 136, (3), 465–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ruiz-Suarez N; Camacho M; Boada LD; Henriquez-Hernandez LA; Rial C; Valeron PF; Zumbado M; Gonzalez MA; Luzardo OP, The assessment of daily dietary intake reveals the existence of a different pattern of bioaccumulation of chlorinated pollutants between domestic dogs and cats. Sci Total Environ 2015, 530–531, 45–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ruiz-Suárez N; Rial C; Boada LD; Henríquez-Hernández LA; Valeron PF; Camacho M; Zumbado M; Almeida González M; Lara P; Luzardo OP, Are pet dogs good sentinels of human exposure to environmental polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, organochlorine pesticides and polychlorinated biphenyls?. J. Appl. Anim. Res. 44(1), 135–145 (2016) 2016, 44, (1), 135–145. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Animals as Sentinels of Environmental Health Hazards: Committee on Animals as Monitors of Environmental Hazards In National Research Council (U.S.). Committee on Animals as Monitors of Environmental Hazards, National Academy Press: Washington D.C., 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bukowski JA; Wartenberg D; Goldschmidt M, Environmental causes for sinonasal cancers in pet dogs, and their usefulness as sentinels of indoor cancer risk. J Toxicol Environ Health A 1998, 54, (7), 579–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pinello KC; Santos M; Leite-Martins L; Niza-Ribeiro J; de Matos AJ, Immunocytochemical study of canine lymphomas and its correlation with exposure to tobacco smoke. Vet World 2017, 10, (11), 1307–1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Reif JS; Bruns C; Lower KS, Cancer of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses and exposure to environmental tobacco smoke in pet dogs. Am J Epidemiol 1998, 147, (5), 488–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Glickman LT; Raghavan M; Knapp DW; Bonney PL; Dawson MH, Herbicide exposure and the risk of transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder in Scottish Terriers. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2004, 224, (8), 1290–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Knapp DW; Ramos-Vara JA; Moore GE; Dhawan D; Bonney PL; Young KE, Urinary bladder cancer in dogs, a naturally occurring model for cancer biology and drug development. ILAR J 2014, 55, (1), 100–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shapiro SG; Raghunath S; Williams C; Motsinger-Reif AA; Cullen JM; Liu T; Albertson D; Ruvolo M; Bergstrom Lucas A; Jin J; Knapp DW; Schiffman JD; Breen M, Canine urothelial carcinoma: genomically aberrant and comparatively relevant. Chromosome Res 2015, 23, (2), 311–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ito D; Frantz AM; Modiano JF, Canine lymphoma as a comparative model for human non-Hodgkin lymphoma: recent progress and applications. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 2014, 159, (3–4), 192–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Richards KL; Suter SE, Man’s best friend: what can pet dogs teach us about non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma? Immunol Rev 2015, 263, (1), 173–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Marconato L; Gelain ME; Comazzi S, The dog as a possible animal model for human non-Hodgkin lymphoma: a review. Hematol Oncol 2013, 31, (1), 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ettlin J; Clementi E; Amini P; Malbon A; Markkanen E, Analysis of Gene Expression Signatures in Cancer-Associated Stroma from Canine Mammary Tumours Reveals Molecular Homology to Human Breast Carcinomas. Int J Mol Sci 2017, 18, (5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Amini P; Nassiri S; Ettlin J; Malbon A; Markkanen E, Next-generation RNA sequencing of FFPE subsections reveals highly conserved stromal reprogramming between canine and human mammary carcinoma. Dis. Model. Mechan 2019, 12, (8). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.